Abstract

There are more than 1.15 million cases of breast cancer diagnosed worldwide annually. At present, only small numbers of accurate prognostic and predictive factors are used clinically for managing the patients with breast cancer. DNA microarrays have the potential to assess the expression of thousands of genes simultaneously. Recent preliminary researches indicate that gene expression profiling based on DNA microarray can offer potential and independent prognostic information in patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer. In this paper, an overview upon the applications of microarray techniques in breast cancer is presented.

KEY WORDS: Breast cancer, DNA, genome, microarray

Breast cancer in women represents a significant health problem. Thirty percent of all cancers in women occur in breast thereby making it the most common form of cancer.[1] In majority of the cases, i.e., about 90% breast cancer is always due to genetic abnormalities such as variations in high-penetrance genes such as BRCA1, BRCA2, p53, PTEN, ATM, NBS1, LKB1, etc.[2] In addition, the AR, ATM, BARD1, BRIP1, CHEK2, DIRAS3, ERBB2, NBN, PALB2, RAD50, and RAD51 genes are associated with breast cancer.[3] Only 5%-10% of cancers is due to an abnormalities inherited from parents, either of them. Breast cancer starting in tissues may be invasive or non-invasive. Invasive are the ones which spread from milk duct or lobules to other tissues in the breast while noninvasive means it has not invaded other breast tissues. Noninvasive breast cancer is called “in situ”. Therefore, two main types of cancer are; ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or intraductal carcinoma and lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS). Many breast cancers are also sensitive to hormone estrogen.

Cancer cells exhibit a common phenotype of uncontrolled cell growth, but this phenotype may arise from many different combinations of mutations. By inferring how cells evolve in individual tumors, a process called cancer progression; we may be able to identify important mutational events for different tumor types, potentially leading to new therapeutics and diagnostics. Work of Park et al.[1] has shown that it is possible to infer frequent progression pathways by using gene expression profiles to estimate “distances” between tumors. Human breast, tumors are diverse in their natural history, is a heterogeneous disease that comes in several clinical and histological forms. The mechanism(s) accounting for breast cancer heterogeneity remains elusive. Breast cancer can be grouped into major subtypes by both histopathological features (e.g., histological type, grade, estrogen receptor, progesterone, HER2 status) used in diagnostic as well as newer microarray based molecular profiling.[4,5]

A study of sporadic breast tumors samples by Perou et al.[5] was the first to show that breast tumors could be classified into subtypes distinguished by differences in their expression profiles. Using 40 breast tumors and 20 matched pairs of samples before and after doxorubicin treatment, an “intrinsic gene set” of 476 genes were selected that were more variably expressed between 40 tumors than between the paired samples. In an interesting analysis, Chang et al.[6] demonstrated clustering and segregation study using 78 tumors and 70 prognostic genes. On the basis of expression levels, four major subgroups: a “luminal cell-like” group expressing the estrogen receptor (ER); a “basal-like” group expressing keratins 5 and 17, integrin β4, and laminin, but lacking ER expression; an “Erb-B2-positive” group and a “normal” epithelial group were identified. In another study, Gruvberger et al.,[7] profiled 58 grossly dissected primary invasive breast tumors and used artificial neural network (ANN) analysis to predict the ER status of tumors on the basis of their gene expression patterns.

Microarray Technology

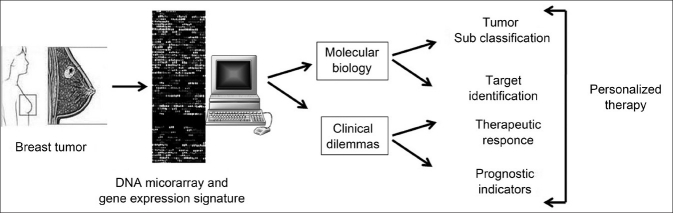

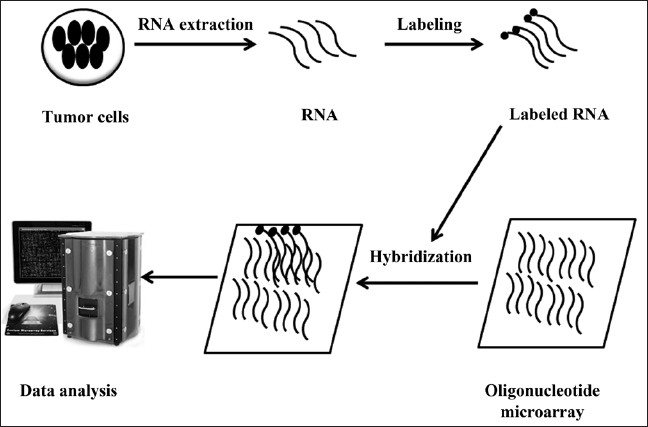

Basic principle of microarray is base-pairing and hybridization [Figure 1]. DNA microarray platforms for gene expression profiling were invented relatively recently, and breast cancer has been among the earliest and most intensely studied disease using this technology. The new molecular profiling has enriched our understanding of breast cancer heterogeneity and yielded new prognostic and predictive information.

Figure 1.

An outline of microarray methodology

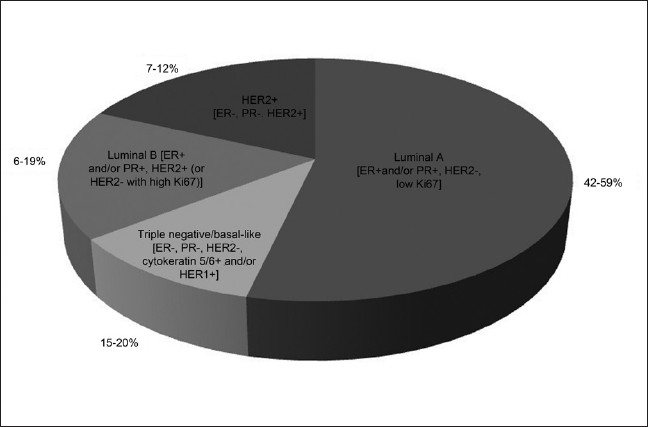

Four different gene lists composed of varying number of genes have been used for molecular subtype identification and classification of breast cancer.[8] The newer molecular taxonomy has highlighted the existence of four major subtypes (Luminal-A, Luminal-B, Basal-like, HER2) that overlap with different clinical and pathological classification systems [Figure 2].[9,10] Expression profiling class discovery studies have led to a working model for breast cancer molecular taxonomy, which has become widely used and recently adopted for the design of clinical trials. The molecular signatures so identified help not only in revealing the biological spectrum of breast cancers, but simultaneously also provide diagnostic as well as prognostic and predictive gene signatures, and may identify new therapeutic targets.[11] Moreover, creation of tissue microarray (TMA) allows for the rapid immune-histochemical analysis of thousands of tissue samples in a parallel fashion.[12] Although optimizing treatment through microarray-based molecular subtyping is a promising method, current application is restricted to the prediction of distant recurrence risk.[13]

Figure 2.

Molecular subtypes of breast cancer and their distribution

Recent Developments in Application of Microarray in Breast Cancer

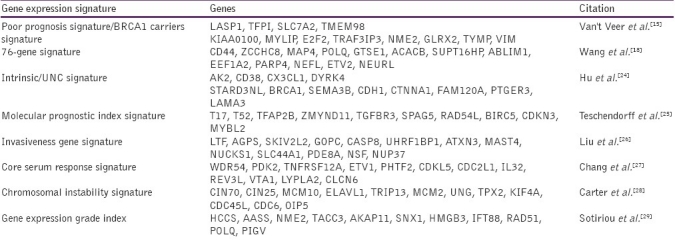

A numerous whole-genome approaches have been carried out to identify the molecular profiles that reflect breast cancer progression. The scope of prevalent whole genome profiling efforts has encompassed on classical karyotypic analyses that identify chromosomal rearrangements,[14] as well as gene expression profile[15] and epigenetic studies[16,17] that provide snap-shot signatures of gene expression and chromatin modification patterns, respectively. In the context of breast cancer, whole genome approaches have identified prognostic gene sets that predict a short interval to distant metastases (i.e., a poor prognosis signature;[18–20] and described gene profiles that mediate metastasis to a secondary site).[21–23] However, few reports have identified epigenetic signatures of breast cancer, particularly in the context of epigenetic mechanisms of tumorigenesis that could be applied in cancer management [Table 1]. Such applications could provide diagnostic tests, prognostic factors and predictors of treatment response that would complement standard gene-expression based assays.[30] Furthermore, the integration of datasets from multiple whole genome platforms is complicated by the interrelated nature of the genetic and epigenetic signatures that characterize individual cells in both their normal or tumorigenic states.[31]

Table 1.

Some of gene expression signatures available for clinical use

Rodenhiser et al.[17] identified genome-wide DNA methylation changes in a cell-line model of breast cancer metastasis. They studied complex epigenetic changes, along with concurrent karyotype analyses thereby leading to the hypothesis that complex genomic alterations in cancer cells (deletions, translocations, and ploidy) are superimposed over promoter-specific methylation events that are responsible for gene-specific expression changes observed in breast cancer metastasis. In a recent study, Rodenhiser et al.[32] carried out simultaneous high resolution, whole-genome analyses of MDA-MB-468GFP and MDA-MB-468GFP-LN human breast cancer cell lines (an isogenic, paired lymphatic metastasis cell-line model) using Affymetrix gene expression (U133), promoter (1.0R), and SNP/CNV (SNP 6.0) microarray platforms to correlate data from gene expression, epigenetic (DNA methylation), and combination copy number variant/single nucleotide polymorphism microarrays. Many of these epigenetic alterations correlated with gene expression changes. This approach allows more precise profiling of functionally relevant epigenetic signatures that are associated with cancer progression and metastasis.

A two-color microarray-based profiling platform was optimized by Marton et al.[33] using a set of 50 fresh frozen (FF) breast cancer samples. Veer et al.[15] assigned class labels according to the signature and method. They proved that profiling platform is able to accurately sort formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissues (FFPET) samples into class labels derived from FF classifiers. Furthermore, using this platform, a classifier derived from FFPET samples can reliably provide the same sorting power as a classifier derived from matched FF samples. Lih et al.[34] study paves the way to identify novel molecular biomarkers for disease stratification and therapy response from archival FFPET samples, leading to the goals of personalized medicine [Figure 3]. Fixed in formalin and embedded in paraffin (FFPE), tissues are the most commonly available clinical samples with documented clinical information for retrospective clinical analysis. However, till date there has been limited application of microarray- based gene expression analysis to FFPET.

Figure 3.

DNA microarrays offer the capability to develop personalized therapeutic treatments by supporting clinical decision making, as well as improving our understanding of the molecular basis of breast cancer

Tissue samples collected during surgery as well as biopsies are often FFPE. Molecular genomics assays on archived FFPE blocks, together with clinicopathological information, can provide critical insights into a heterogeneous disease such as breast cancer. Gene expression profiling of FFPE samples represents great potential for translational cancer research.[35,36] Formalin preserves tissue and cellular structure by cross-linking proteins and macromolecules.[37] Unfortunately, this type of analysis has proven to be problematic because of the poor quality of RNA extracted from FFPE. Microarray expression analysis using FFPE tissues has been problematic as the retrieval of RNA from FFPE material is challenging.[38] FFPE archival methods lead to chemical modifications (methylene dimerization ormonomethylolation) and the partial degradation of the RNA (up to 50% of the RNA may not contain an intact poly-A tail),[38,39] making RNA extraction, reverse transcription and quantitation a difficult process. Formalin-fixed (FF) tissues have been shown to yield compromised RNA compared with that obtained from frozen tissue. Currently, several prognostic microarray gene expression signatures for breast cancer have been generated using fresh frozen material.[40]

Lih et al.,[34] used a novel RNA amplification method, Single primer isothermal amplification (SPIA) to amplify FFPET RNA, which was hybridized amplified, and labeled cDNA onto Affymetrix HG U133plus2 GeneChips. It was observed that SPIA amplification successfully overcomes the problems of poor quality of FFPET RNA, and produced informative biological data. Comparison of gene expression data from five different types of FFPET archival cancer samples (breast, lung, ovarian, colon, and melanoma), demonstrated that gene expression signatures clearly distinguish the tissue of origin. Further, from an analysis of 91 FFPET samples comprised of ER+, HER2+, triple negative breast cancer patients, and normal breast tissue, they identified a 103 gene signature that distinguishes the intrinsic subtypes of breast cancer. The accuracy of gene expression measured by microarray was verified by real time PCR quantization of the ERBB2 gene, resulting in a significant correlation (R = 0.88).

Zhou et al.[41] developed dissociable antibody microarray (DAMA) staining technology that combines protein microarrays with traditional immune-staining techniques and demonstrated its application in identifying potential biomarkers for breast cancer. DAMA can simultaneously determine the expression and subcellular location of hundreds of proteins in cultured cells and tissue samples. They compared the expression profiles of 312 proteins among three normal breast cell lines and seven breast cancer cell lines and identified 10 differentially expressed proteins by the data analysis program DAMAPEP (DAMA protein expression profiling). Among the investigated proteins, RAIDD, Rb p107, Rb p130, SRF, and Tyk2 were confirmed by Western blot and statistical analysis to have higher expression levels in breast cancer cells than in normal breast cells and therefore concluded that these proteins could be potential biomarkers for the diagnosis of breast cancer.

Glass et al.[42] demonstrated for the first time that microarray technology can be used as a reliable diagnostic tool. They established 70-gene tumor expression profile, on microarrays containing 25,000 60-mer oligonucleotides, as a powerful predictor of disease outcome in young breast cancer patients. Bose et al.[43] studied the status of Akt pathway in human breast cancers and relationship with different component proteins. Expression levels of phosphorylated form of constituent proteins and cyclin D1 were evaluated by immunohistochemistry, on consecutive sections from a tissue microarray containing 145 invasive breast cancers and 140 pure ductal carcinomas in situ.

Various groups have explored the power of expression profiling using cDNA or DNA microarrays for distinguishing subgroups of breast cancers.[44–46] Meta-analysis of independent microarray datasets generated with the common objective of identifying differentially expressed genes in a certain type of cancer has also been performed for breast cancer. In a very recent meta-analysis study, Smith et al.[47] identified differentially expressed genes between ER+ and ER-- breast tumors by gathering nine independent breast cancer microarray studies. Another study used the power of meta-analysis to find out the relation of expression patterns of gene and chromosomal positions. More than 1200 breast tumors were collected from eight independent breast studies and candidate metastasis suppressor and promoting genes were found from a given set of chromosomal regions.[48] Similarly, Hu et al.[24] were able to identify a new intrinsic gene-set for breast cancer subtype prediction by combining multiple microarray datasets to assess prognosis.

Several different meta-analysis approaches exist in the literature. In some, each individual study contributes rather independently to the meta-analysis[49–51] whereas in others the values are treated as members of a single study thus requiring a generalized normalization step.[52] In a recent study Dedeoglu et al.[53] developed resampling-based meta-analysis strategy, which involves the use of resampling and application of distribution statistics in combination to assess the degree of significance in differential expression between sample classes. They used two independent microarray datasets that contain normal breast, invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), and invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) samples for study. Expression of the genes, selected from the gene list for classification of normal breast samples and breast tumors encompassing both the ILC and IDC subtypes were tested on 10 independent primary IDC samples and matched nontumor controls by real-time qRT-PCR. Direct comparison of gene expression values from multiple studies may be relatively more problematic than comparing the effect size obtained from individual studies. Yet, the analysis of combined raw data is beneficial when sample sizes of individual studies are small.

Microarray-based Online Platforms for Breast Cancer

Recently, various microarray-based online tools have been developed with promises of assistance to the treatment decisions for breast cancer patients. Gene expression-based Outcome for Breast cancer Online (GOBO) is one of newly developed online tool.[54] GOBO has three main applications: Gene Set Analysis (GSA), Coexpressed Genes (CG), and Sample Prediction (SP).

Recurrence online is another online tool for microarray-based breast cancer diagnosis. It is an online analysis tool to determine breast cancer recurrence and hormone receptor status using microarray data. It also has three major applications: prediction of response to hormonal treatment (ER status), prediction of response to targeted therapy 9HER2 status) and estimation of survival (recurrence score) for breast cancer patients.[55] Kaplan--Meier Plotter (KM Plotter) is online tool for the preliminary biomarker assessment. It has two applications: KM plotter for breast cancer and KM plotter for ovarian cancer. Prognostic value of a particular gene can be analyzed by splitting the patient sample into two groups according to various quantile expressions of the proposed biomarker. Comparison can be made between the two patient cohorts in terms of relapse free survival or overall survival. KM plotter displays survival curve, the hazard ratio with 95% confidence intervals and log-rank P value as output.[56]

Conclusion

The molecular basis of breast cancer has been redefined over the past decade. Paving the way in this respect has been the advent of DNA microarray technology, which has provided a massive source of data on gene expression alterations in human breast tumors. Microarray profiling has, unquestionably, been established as a powerful tool in unraveling mechanistic insights into tumor biology. The initial studies have been promising enough to provide a novel, personalized dimension to the treatment and care of breast cancer patients; however, development of predictive signatures within the dimension of molecular subtypes is an area requiring further investigation. To conclude, researchers need to employ an array of different technologies and utilize the whole spectrum of biological and clinical data available in order to elucidate and clarify the multifaceted complexity of breast cancer.

Acknowledgment

We are deeply grateful to Mr. Aseem Chauhan, chairman of Amity University Uttar Pradesh- Lucknow Campus for providing us necessary facilities and support. We would also like to extend our gratitude to Maj. Gen. K.K Ohri, AVSM (Retd.), Director General of Amity University, Uttar Pradesh- Lucknow Campus for providing us valuable guidance and encouragement throughout the work.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Park Y, Shackney S, Schwartz R. Network-based inference of cancer progression from microarray data. IEEE/ACM Trans Comput Biol Bioinform. 2009;6:200–12. doi: 10.1109/TCBB.2008.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dumitrescu RG, Cotarla I. Understanding breast cancer risk--where do we stand in 2005? J Cell Mol Med. 2005;9:208–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2005.tb00350.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Honrado E, Osorio A, Palacios J, Benitez J. Pathology and gene expression of hereditary breast tumors associated with BRCA1, BRCA2 and CHEK2 gene mutations. Oncogene. 2006;25:5837–45. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorliiea T, Peroua CM, Tibshiranie R, Aasf T, Geislerg S, Johnsenb H, et al. Gene experimentation pattern of breast carcinomas distinguish tumor subclasses with clinical implications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10869–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191367098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perou CM, Sorlie T, Eisen MB, van de Rijn M, Jeffrey S, Rees CA, et al. Molecular portraits of human breast tumours. Nature. 2000;406:747–52. doi: 10.1038/35021093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang J, Hilsenbeck S, Fuqua S. The promise of microarrays in the management and treatment of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7:100–4. doi: 10.1186/bcr1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gruvberger S, Ringner M, Chen Y, Panavally S, Saal LH, Borg A, et al. Estrogen receptor status in breast cancer is associated with remarbly distinct gene expression patterns. Cancer Res. 2001;61:5979–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mackay A, Weigett B, Grigoriadis A, Kreike B, Natrajan R, A’Hern R, et al. Microarray based class discovery for molecular classification of breast cancer: Analysis of interobserver agreement. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103:662–73. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su Y, Zheng Y, Zheng W, Gu K, Chen Z, Li G, et al. Distinct distribution and prognostic significance of molecular subtypes of breast cancer in Chinese women: A population-based cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:292. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Ejeh F, Smart CE, Morriosn BJ, Chenevix-Trench G, Lopez JA, Lakhani SR, et al. Breast cancer stem cells: Treatment resistance and therapeutic opportunities. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32:650–8. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheang MC, van de Rijn M, Nielsen TO. Gene expression profiling of breast cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2008;3:67–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathmechdis.3.121806.151505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheen-Chen SM, Zhang H, Huang CC, Tang RP. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-3 in breast cancer: Analysis with tissue microarray. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:1131–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kao KJ, Chang KM, Hsu HC, Huang AT. Correlation of microarray-based breast cancer molecular subtypes and clinical outcomes: Implications for treatment optimization. BMC Cancer. 2011;18:143. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu J, Chambers AF, Tuck AB, Rodenhiser DI. Molecular cytogenetic characterization of human breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-468 and its variant 468LN, which displays aggressive lymphatic metastasis. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2008;181:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2007.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van’t Veer LJ, Dai H, van de Vijver MJ, He YD, Hart AA, Mao M, et al. Gene expression profiling predicts clinical outcome of breast cancer. Nature. 2002;415:530–6. doi: 10.1038/415530a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sadikovic B, Andrews J, Carter D, Robinson J, Rodenhiser DI. Genome wide H3K9 histone acetylation profiles are altered in benzopyrene treated MCF7 breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:4051–60. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707506200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodenhiser DI, Andrews J, Kennette W, Sadikovic B, Mendlowitz A, Tuck AB, et al. Epigenetic mapping and functional analysis in a breast cancer metastasis model using whole-genome promoter tiling microarrays. Breast Cancer Res. 2008;10:R62. doi: 10.1186/bcr2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Y, Klijn JG, Zhang Y, Sieuwerts AM, Look MP, Yang F, et al. Gene expression profiles to predict distant metastasis of lymph-node-negative primary breast cancer. Lancet. 2005;365:671–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)17947-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weigelt B, Hu Z, He X, Livasy C, Carey LA, Evend MG, et al. Molecular portraits and 70-gene prognosis signature are preserved throughout the metastatic process of breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2005;65:9155–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buyse M, Loi S, van’t Veer L, Viale G, Delorenzi M, Glas AM, et al. Validation and clinical utility of a 70-gene prognostic signature for women with node-negative breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1183–92. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Welch DR. Microarrays bring new insights into understanding of breast cancer metastasis to bone. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:61–4. doi: 10.1186/bcr736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minn AJ, Gupta GP, Siegel PM, Bos PD, Shu W, Giri DD, et al. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to lung. Nature. 2005;436:518–24. doi: 10.1038/nature03799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang Y, Siegel PM, Shu W, Drobnjak M, Kakonen SM, Cordón-Cardo C, et al. A multigenic program mediating breast cancer metastasis to bone. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:537–49. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu Z, Fan C, Oh DS, Marron JS, He X, Qaqish BF, et al. The molecular portraits of breast tumors are conserved across microarray platforms. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:96. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Teschendorff AE, Naderi A, Barbosa-Morais NL, Pinder SE, Ellis IO, Aparicio S, et al. A consensus prognostic gene expression classifier for ER positive breast cancer. Genome Biol. 2006;7:R101. doi: 10.1186/gb-2006-7-10-r101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu R, Wang X, Grace YC, Dalerba P, Gurney A, Hoey T, et al. The prognostic role of a gene signature from tumorigenic breast-cancer cells. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:217–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chang HY, Nuyten DS, Sneddon JB, Hastie T, Tibshirani R, Sorlie T, et al. Robustness, scalability, and integration of a wound-response gene expression signature in predicting breast cancer survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:3738–43. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409462102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carter SL, Eklund AC, Kohane IS, Harris LN, Szallasi Z. A signature of chromosomal instability inferred from gene expression profiles predicts clinical outcome in multiple human cancers. Nat Genet. 2006;38:1043–8. doi: 10.1038/ng1861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sotiriou C, Wirapati P, Loi S, Harris A, Fox S, Smeds J, et al. Gene expression profiling in breast cancer: Understanding the molecular basis of histologic grade to improve prognosis. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:262–72. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esteller M. Epigenetics in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:1148–59. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Esteller M. Cancer epigenomics: DNA methylomes and histone modification maps. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:286–98. doi: 10.1038/nrg2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodenhiser DI, Andrews J, Kennette W, Pilon J, Hodgson A, Tuck AB, et al. Mutli-platform whole-genome microarray analyses refine the epigenetic signature of breast cancer metastasis with gene expression and copy number. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e8665. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duenwald S, Zhou M, Wang Y, Lejnines S, Kulkarin A, Graves J, et al. Development of a microarray platrform for FFPET profiling: Application to the classification of human tumors. J Transl Med. 2009;7:65. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lih C, Li Y, Trinh L, Chien S, Wu X, Liu W, et al. Breast cancer patients stratification by microarray-based gene expression profiling from FFPET samples. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:e22041. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramaswamy S. Translating cancer genomics into clinical oncology. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1814–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp048059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.April C, Klotzle B, Royce T, Wickham-Garcia E, Boyaniwsky T, Izzo J, et al. Whole-genome gene expression profiling of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue samples. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8162. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Werner M, Chott A, Fabiano A, Battifora H. Effect of formalin tissue fixation and processing on immunohistochemistry. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24:1016–9. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200007000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Farragher SM, Tanney A, Kennedy RD, Paul Harkin D. RNA expression analysis from formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissues. Histochem Cell Biol. 2008;130:435–45. doi: 10.1007/s00418-008-0479-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Masuda N, Ohnishi T, Kawamoto S, Monden M, Okubo K. Analysis of chemical modification of RNA from formalin-fixed samples and optimization of molecular biology applications for such samples. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:4436–43. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.22.4436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scicchitano MS, Dalmas DA, Bertiaux MA, Anderson SM, Turner LR, Thomas RA, et al. Preliminary comparison of quantity, quality, and microarray performance of RNA extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded, and unfixed frozen tissue samples. J Histochem Cytochem. 2006;54:1229–37. doi: 10.1369/jhc.6A6999.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song XC, Fu G, Yang X, Jiang Z, Wang Y, Zhou WG. Protein expression profiling of breast cancer cells by dissociable antibody microarray (DAMA) staining. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:163–9. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700115-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glass AM, Floore A, Delahaye LJ, Witteveen AT, Pover RC, Bakx N, et al. Converting a breast cancer microarray signature into a high-throughput diagnostic test. BMC Genomics. 2006;7:278. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-7-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bose S, Chandran S, Mirocha JM, Bose N. The Akt pathway in human breast cancer: A tissue-array-based analysis. Mod Pathol. 2006;19:238–45. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.3800525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sorlie T, Tibshirani R, Parker J, Hastie T, Marron JS, Nobel A, et al. Repeated observation of breast tumor subtypes in independent gene expression data sets. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:8418–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932692100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhao H, Langerod A, Ji Y, Nowels KW, Nesland JM, Tibshirani R, et al. Different gene expression patterns in invasive lobular and ductal carcinomas of the breast. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:2523–36. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-11-0786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Farmer P, Bonnefoi H, Becette V, Tubiana-Hulin M, Fumoleau P, Larsimont D, et al. Identification of molecular apocrine breast tumours by microarray analysis. Oncogene. 2005;24:4660–71. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Smith DD, Saetrom P, Snove O, Jr, Lundberg C, Rivas GE, Glackin C, et al. Meta-analysis of breast cancer microarray studies in conjunction with conserved cis-elements suggest patterns for coordinate regulation. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008;9:63. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-9-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomassen M, Tan Q, Kruse TA. Gene expression meta-analysis identifies chromosomal regions and candidate genes involved in breast cancer metastasis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;113:239–49. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9927-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moreau Y, Aerts S, De Moor B, De Strooper B, Dabrowski M. Comparison and meta-analysis of microarray data: From the bench to the computer desk. Trends Genet. 2003;19:570–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2003.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rhodes DR, Barrette TR, Rubin MA, Ghosh D, Chinnaiyan AM. Meta-analysis of microarrays: Interstudy validation of gene expression profiles reveals pathway dysregulation in prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:4427–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Choi JK, Yu U, Kim S, Yoo OJ. Combining multiple microarray studies and modeling interstudy variation. Bioinformatics. 2003;19(Suppl 1):i84–90. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg1010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Warnat P, Eils R, Brors B. Cross-platform analysis of cancer microarray data improves gene expression based classification of phenotypes. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:265. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gur-Dedeoglu B, Konu O, Kir S, Ozturk AR, Bozkurt B, Ergul G, et al. Resampling-based meta-analysis for detection of differential gene expression in breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:396. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ringner M, Fredlund E, Hakkinen J, Borg A, Staaf J. GOBO: Gene expression-based Outcome for Breast cancer Online. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gyorffy B, Benke Z, Lanczky A, Balazs B, Szallasi Z, Timar J, et al. Recurrence online: An online analysis tool to determine breast cancer recurrence and hormone receptor status using microarray data. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1676-y. [In press] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gyorffy B, Lanczky A, Eklund AC, Denkert C, Budczies J, Li Q, et al. An online survival analysis tool to rapidly assess the effect of 22,277 genes on breast cancer prognosis using microarray data of 1,809 patients. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:725–31. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0674-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]