Abstract

The need for scientific evidence should be the basis of clinical practice. The field of restorative dentistry and endodontics is evolving at a rapid pace, with the introduction of several materials, instruments, and equipments. However, there is minimal information of their relevance in clinical practice. On the one hand, material and laboratory research is critical, however; its translation into clinical practice is not being substantiated enough with clinical research. This four part review series focuses on methods to improve evidence-based practice, by improving methods to integrate laboratory and clinical research.

Keywords: Clinical research; evidence-based dentistry; measurement iterative loop; Patient/Population/Problem, intervention, comparison, and outcome format; research methodology

INTRODUCTION

The field of dental research in India has witnessed exponential growth in the last five years.[1] However, scientific publications in international peer-reviewed journals have been few.[2] The lacuna of Indian contribution to international scientific literature is probably a skewed understanding of research and its contribution in effecting improved patient care. The primary purpose of research is to produce new knowledge or find new ways of making the existing knowledge available to those who need it. Research is not a separate speciality which is practiced by a few but it is a systematic approach of reasoning, documenting, analysing and reporting unusual clinical observations that we come across in everyday clinical practice. Whether one is a “doer” or a “user” of research, a thorough understanding of the methodology is essential. In addition to individual practitioners, the “users” of research includes 1) professional organizations that set “practice guidelines”;2) policy makers (sometimes called as “decision makers”) and 3) program managers (for example, state or national government managers of dental health programs). While the academicians and research scholars (teaching institutions) have a unique position to be “Doers” of research. The value for research for its own sake is limited, and therefore understanding the essential concepts in Research Methodology is vital in producing dependable knowledge.

The purpose of this review series is to help the reader to organize the thought process when considering research needs and methods. It also aims to sensitize the mind to research avenues that would be beneficial to material and clinical research in particular and improving the quality of clinical care in general. This four-part review series encompasses topics on essentials of research, fundamentals in biostatistics, observational studies, and experimental studies in each part.

Conduct of research: The head start

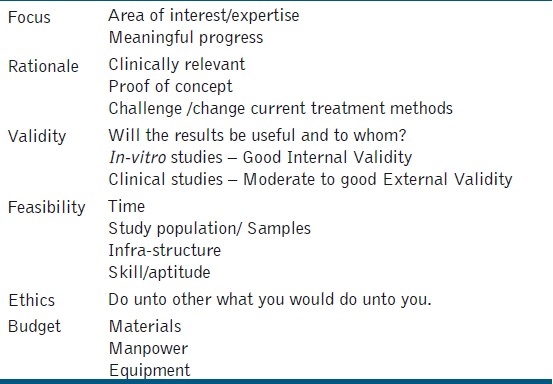

Every action is first conceived in the mind and later executed. Planning a good research project forms the primary basis of meaningful publication. Certain fundamental requisites are listed in Table 1. Focus in a particular area of interest is essential to build up a strong forte in academic excellence. Random choice of research projects dilutes the resource contribution in random directions and results in lack of identity of the person or faculty. Generating research hypothesis must aim at answering clinically relevant questions. The rationale for the choice of a particular stream could also result in a new concept of thinking or change the methods of treatment protocols.

Table 1.

Requisites of good research

It is prudent to decide apriori as to whom the results of a particular research question would be useful and will the results be applicable to patients in dental practices in the real world. Conventionally, in-vitro or laboratory research studies have good internal validity but poor external validity which means that the results obtained are only applicable to similar samples of the study. In other words, the results may not transfer to the clinical behaviour of the material. On the other hand, clinical studies have good external validity because they are tested on samples/ subjects that are closely related to the clinical condition and most often representative of all individuals with the condition; however they are more complex since so many other factors may influence the outcome of interest.

To understand validity, let us consider the research question on dentin bonding agents (DBA). In-vitro assessment of dentin bonding agents is usually measured in terms of bond strength and microleakage. In this scenario, all the samples and procedures are standardized to a specific methodology, that is, dentin cylinders 5 mm in height, with 4 mm of composite material, × N force at 0.5 cross-head speed, and so on. The bond strength values obtained can be best extrapolated to a similar set of conditions in the laboratory and may not deliver the same performance clinically to patients. On the contrary, if we conduct a clinical study to evaluate the performance of dentin bonding agents, the methodology would include a randomized controlled trial involving the restoration of non-carious cervical lesions ((NCCL), considered the ideal for bonding agent testing), the clinical evaluation criteria recommended by the United States Public Health System (USPHS), and followed over a period of time. The results of the study can be extrapolated to all similar patients requiring restoration of NCCLs. Hence, the valid method of testing the ultimate performance of DBA is by a clinical trial and not just bond strength testing. However, in-vitro studies provide an insight into which DBA is the best among the available, to be tested clinically. In-vitro studies provide internal validity, that is, they tell us if a particular drug or procedure works, but external validity questions if it is of use to the patient population at large, which can only be determined by clinical trials on patients.

Feasibility in terms of time, cost, samples, and infrastructure are vital to set a logistic time frame for the functioning and completion of the study. Finally, a study that does not adhere to ethical principles both for in-vitro and clinical designs, fails to answer clinically relevant questions. The principles of ethics are not restricted only to the handling of human participants, but also encompass the ethics followed in the methodology and reporting of results. The Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) has comprehensive guidelines for conducting experimental studies in India.[3]

Clinical epidemiology

The term Epidemiology refers to the study of the distribution and determinants of health-related states or events (including disease), and the application of these methods to the control of diseases and other health problems.[4] Erroneously in India, this science is often dissociated from dental clinical research and is regarded to be a practice under community dentistry. Hence research methods described under epidemiology have also not been used in answering many of our clinical research questions. David Sackett, in 1969, coined the term clinical epidemiology, which is the, “application, by a physician who provides direct patient care, of epidemiological and biometric methods, to the study of diagnostic and therapeutic processes, in order to effect an improvement in health.”[5] This concept identifies the clinician as the epidemiologist, which chiefly includes practitioners (general/specialist), students, and academicians, who are constantly involved in patient care. Almost four decades since this concept was introduced, our fraternity is waking up to this approach. It is important to note that knowledge of the disease process and treatment protocols constitute clinical knowledge. This forms only one essential part of clinical epidemiology. In order to understand the involvement of clinicians in clinical research, we need to be aware of certain disease manifestations in the community, with regard to the magnitude of the problem and measures to deliver dentalcare.

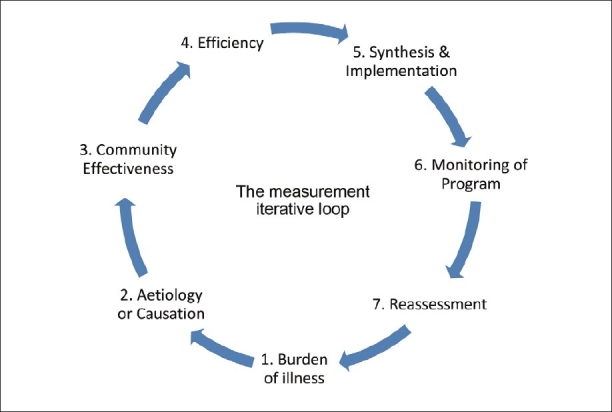

Consider this question being asked by the Head of Department of an institution, “What is the best endodontic regime for patients being treated in my department?” Traditionally, this question would be answered by schools of thought, textbook evidence, and findings reported in peer-reviewed literature. In reality, this simple question has the ability to raise meaningful research questions if we could apply this to the measurement iterative loop proposed by Tugwell et al.[6] [Figure 1]. The measurement iterative loop breaks up the disease cycle into distinct component steps. It is iterative because, each step logically leads to the next, and thus comes back to the first step thus ‘closing’ the loop. Each step in the loop has the capacity to generate several research questions.

Figure 1.

The measurement iterative loop

In this loop, the first step is to ascertain the burden of illness. The burden of illness (e.g., patients requiring root canal treatment) could be measured among the patients seeking dental care in the hospital or in a defined population. The former will provide an answer to the rate of occurrence of endodontic disease and the latter addresses the prevalence of endodontic disease, both of which would vary with place and time. The burden of illness could be subdivided into: (a) Unavoidable and (b) avoidable. Avoidable burden of illness comprises of disability, symptoms, and morbidity, for which efficacious caries preventive and intervention methods are present. The unavoidable burden of illness of disability comprises of symptoms and morbidity for which no efficacious prevention or cure exists. Eg if the tooth has been lost then root canal treatment is not possible.The focus on research in this area should be an effort to transfer the burden from unavoidable to avoidable.

Second is to identify and assess the possible cause of the burden of disease. The etiology and risk-factor assessment of a multifactorial disease like pulpal and periapical pathology in itself generates a lot of research avenues. This step also makes use of several traditional study designs to derive clinically significant conclusions. This step identifies the factors against which an intervention can reduce the burden of illness, for example, failure of primary endodontic treatment. To name a few obvious causes, inadequate cleaning and shaping, missed canals, and incomplete obturation. The risk factors in association to this failure could be: Vitality status of the pulp during initial endodontic treatment, amount of remaining tooth structure, and type of tooth.

Defining factors for causation also requires that there should be well-defined, specific, and reproducible definitions for both the disease state and the risk factors. Developing such criteria for defining disease and causative or risk factors contribute to increased diagnostic accuracy.

The third step of the loop is the most significant. Having identified the ‘intervenable’ factors, it is important to study if interventions against them will work. After identifying interventions, in vitro studies are carried out when necessary, and then the successful interventions are tried on humans. The initial trials should be to determine Efficacy. This means that it should be determined whether the intervention works if given in the right dose using the right methods, for the right duration, that is, Can it work in ideal circumstances?

Once this is achieved, the intervention (preventive and restorative) methods are applied to the community, that is, patients seeking treatment for failed endodontic treatment or among the general population at a risk of developing failure of primary endodontic treatment. This step is Community effectiveness, which measures how well an intervention can work in real life. It assesses the benefit/harm ratio of potentially feasible interventions and estimates the reduction of burden of illness, if the program is successful. Community effectiveness is determined by five factors: (a) Efficacy, (b) Screening and diagnostic accuracy, (c) Evaluation of health care provider compliance, (d) Evaluation of patient compliance, and (e) Evaluation of coverage. To understand this better let us consider the question of treating symptomatic irreversible pulpitis with Mineral trioxide aggregate (MTA) pulpotomy in Department of Endodontics at a dental college and give hypothetical percentages of success for each factor and compute the community effectiveness.

Efficacy: Will the current treatment do more good than harm in treating patients who are diagnosed correctly and fully comply with recommendations for treatment?(100%)

Screening and diagnostic accuracy: Does the department have adequate diagnostic methods to identify patients with irreversible pulpitis and ensure methods to follow-up the disease/recovery status? (90%)

Evaluation of health provider compliance: Is a postgraduate student competent enough to perform MTA pulpotomy? (80%)

Evaluation of patient compliance: Will the patient comply with the treatment and follow-up for MTA pulpotomy compared to conventional endodontic treatment? As there are chances that postoperative pain with MTA pulpotomy could be a possibility, the patient suffering from this complication can resort to another dentist for relief. (80%)

Evaluation of coverage: Is the treatment available to all potential patients who could benefit from the new method? Is there access to a dental college or knowledge of the treatment? (90%)

Now community effectiveness can be computed using the Multiplicative law of combining probabilities (P),[7] considering the probability of each of these factors

Community Effectiveness = P (Efficacy 100% × diagnostic accuracy 90% × health provider compliance 80% × patient compliance 80% × coverage 90%) = 52%

After determining an effective treatment plan for the community/patients, the efficiency of the same needs to be evaluated. This step determines the relationships between costs and effects of options within and across the program. Cost could be a major deterrent in MTA pulpotomy. This could propel ingenious preparations to match commercially available MTA, or allocate funds to deliver this treatment to indicated patients. This is followed by the synthesis and implementation of MTA pulpotomy as a standard of care for indicated patients with irreversible pulpitis. This is done after integration of the feasibility of community effectiveness and efficiency. Any program implemented needs to be followed up with systematic documentation and monitoring. It should include markers for success and failure on the basis short-term, intermediate, and long-term treatment outcomes.

With success data in hand, the burden of illness should again be re-assessed, to ascertain any modifications required within the existing program.

Era of evidence-based dentistry

Evidence-based practice is defined as, “the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients. The practice of evidence-based medicine means integrating individual clinical expertise with the best available external clinical evidence from systematic research.”[8] Individual clinical expertise is the proficiency and clinical judgment that is often a summation of clinical experience and clinical practice. This systematic clinical research in our field includes both in-vitro and clinical research, with equal importance. The sensible transition to clinical research by making use of the conclusions of in-vitro research will contribute evidence to various steps of the measurement iterative loop. It is often observed that the thrust for clinical research is feeble and as a result there is insufficient evidence from laboratory research translating to clinical practice. The ideal place to enable contribution to the best clinical evidence would undoubtedly be the institutional organization, which has the balance between clinical expertise from the teachers end and the requirement for research projects from the students’ end. The only missing link is a properly planned research, which can be fullfilled by employing the measurement iterativeloop.

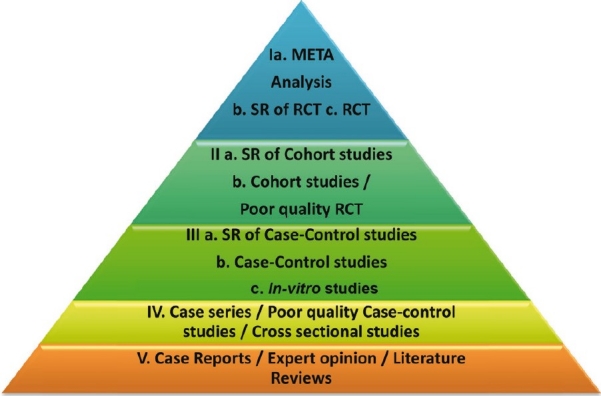

The awareness of evidence-based dentistry is growing not only on the research/clinical front, but also from patients seeking quality dental care. Hence, the possibility of a research study being acknowledged in scientific literature is often driven by the relevance of evidence that a particular research study can deliver. There is a certain hierarchy termed as ‘Levels of Evidence,’ purely based on the reliability of information or from evidence derived from a scientific study,.[9]

There are five levels, and each level has sub-ranks as shown in Figure 2.[7]

Figure 2.

Levels of evidence

Level I

Meta-Analysis

Systematic review (SR) of Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT)

Randomized Controlled Trials

Level II

Systematic review of Cohort Studies

Cohort Studies/Poor quality RCT

Level III

Systematic review of Case-Control Studies

Case-Control Studies

In-vitro Studies

Level IV

Case Series/Cross-sectional studies/Poor quality case control studies

Level V

Case Reports/Expert opinion/Literature review.

It must be noted, with caution, that the level of evidence is only a stratification based on the information that is obtained from each method, with minimal bias, and these levels in no way rank the study design. It is logical to perceive that study designs are chosen based on research questions. For example, even though Randomized Clinical Trials provide the best evidence, this study design is not meant to identify risk factors for occurrence of disease (determined by case-control study) or disease occurrence/prognosis (determined by Cohort study). Hence, levels of evidence are a logical ranking for evidence rather than a ranking for study designs.

What is your research question?

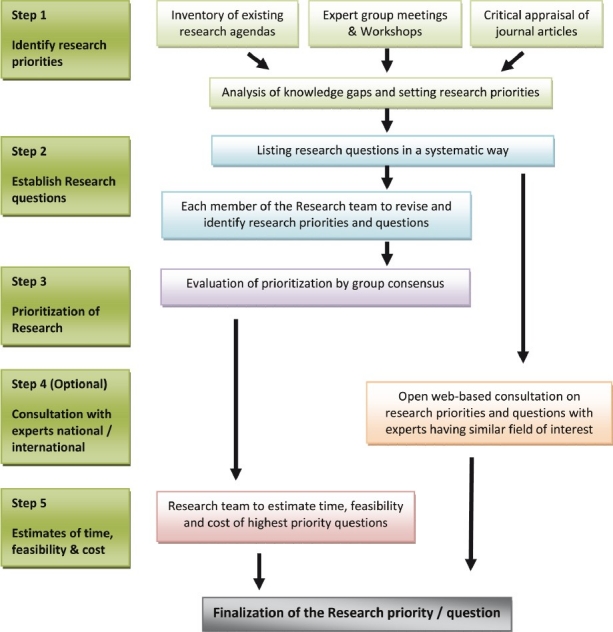

With the understanding of the measurement iterative loop and the significance to generate relevant evidence for clinical practice, the research question should aim at focusing on one primary issue at a time. The method to identify and prioritize research questions is given in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Method used to identify and prioritize research questions

A well-built research question should include four parts, referred to as the PICO format, which includes Patient/Population/Problem, Intervention, Comparison, and Outcome (PICO).[10]

Patient/population/problem — Defines the condition of interest. This is usually derived from the patients’ chief complaint in a clinical situation (in particular or on a larger population) or is derived from the problem faced in a particular material research.

Intervention [or ‘exposure’-making it PECO for causation questions]— It is important to identify what has been planned for the patient or the problem. Depending on the problem, this may include the use of a specific diagnostic test, treatment, medication or the recommendation to the patient, to use a product or procedure. If the problem measures the causation of a particular disease, then the etiological agent is assumed as the intervention.

Comparison — It is an alternative to the intervention under study.

Outcome(s) — This pertains to the result of the study preferably outcomes that can be measured accurately that are important to the patient.

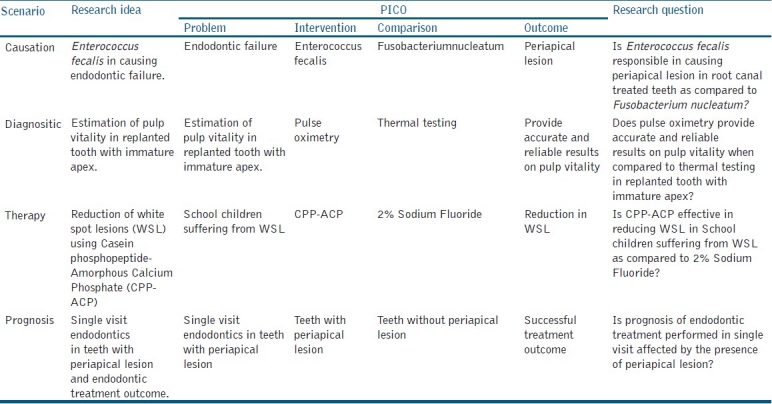

The PICO format can be used to generate a research question for determining the causation of disease, diagnosis of a disease or therapy and prognosis of particular condition/disease. Examples for each are given in Table 2.

Table 2.

Use of PICO format to generate research questions

Although the PICO format is best applied to intervention studies and experimental designs, research questions for all other study designs can also be formulated using this approach.

Role of study designs

Both in-vitro and clinical study designs for various questions arising from clinical practice or knowledge can be determined by applying various sections of the iterative loop. Depending on the research question, the structure of each study design facilitates the derivation of appropriate answers. Prior to choosing the study design, there has to be a valid research question. The genesis of a research question should primarily focus on answering several aspects of a broader research interest. For example, if the research interest lies in stem cell research, then the best source of stem cells, ideal growth environment for stem cells, potential differentiation of stem cells into tissues, confluence of growth obtained by different processing methods, clinical application of laboratory-derived stem cells, storage of stem cells, potential for malignant transformation of stem cells, and so on, form the several aspects or avenues to generate research questions. The primary effort in research is not to focus on the research question, but to focus on your research interest. on study designs and its relevance in answering specific research question will be dealt with in detail in the subsequent articles of this review series on research methodology.

Role of biostatistics

The Role of Biostatistics is often overlooked and ignored in the current research work in our speciality. Biological systems form a dynamic continuum and variation between the units forming the biological systems (people, teeth, bacteria, etc.) is the norm. On account of this variability within the systems, it is often difficult to differentiate between groups within the system. The science of biostatistics helps us to quantify and evaluate its variability within and between groups that make up the biological systems. Statistics is not absolute; it is a measure of the probabilities of occurrence of an event.

Biostatistics is less mathematics and more a method of determining the relevance of the research findings by application of statistical methods. This retains equal importance in both in-vitro as well as clinical research, because this statistical inference lays a foundation for the evidence deduced from any study. Hence the role of the statistician and the clinical researcher are equivalent in finding answers to any research question. The next part on research methodology focuses on understanding biostatics for dental research.

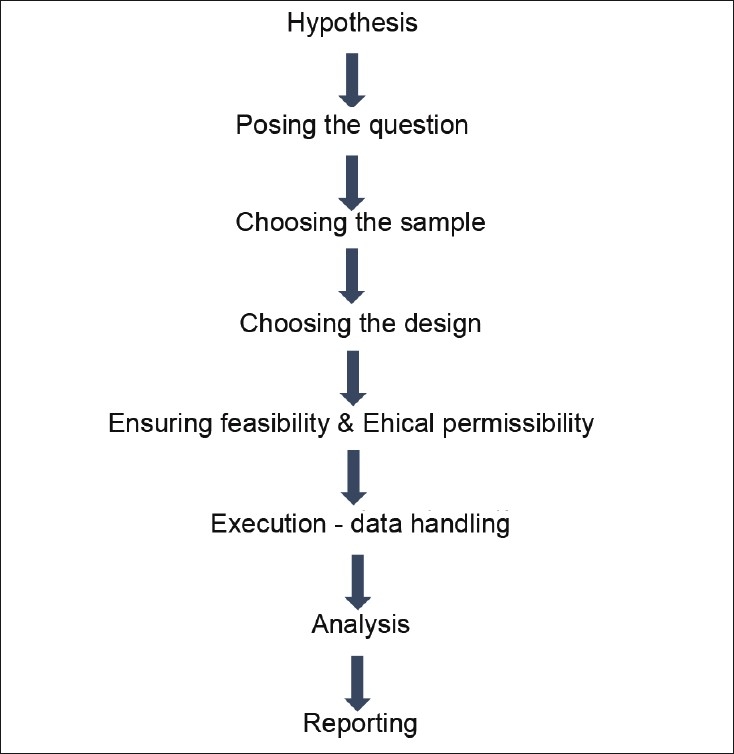

The research processes both in-vitro and clinical studies can be best summarized by the flow chart in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Anatomy of a research study

CONCLUSION

The need for good research is to find the best evidence for clinical practice, for specific problems, and to address methods in reducing the burden of illness on a larger scale. Research studies in Endodontic and Restorative dentistry are two dimensional. The first dimension is the laboratory research, which provides the best evidence on material science and the second dimension is clinical research, which provides the best evidence in dealing with the burden of illness, with efficient clinical practice. This increases the avenues for research studies in several directions. With an increasing requirement to publish, articles with good clinical evidence stand a definite chance to find their place in scientific literature.[11]

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author would like to thank Prof. Peter Tugwell, Professor of Medicine University of Ottawa, Canada, Prof. Emeritus. Vic Neufeld, Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster University, Canada and Prof. Manjula Datta, Retd Prof & Head of Epidemiology, The Tamilnadu MGR Medical university for having accepted to review the manuscript and for their valuable inputs in the preparation of the same and Chennai Dental Research Foundation, Chennai for their support.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gopikrishna V. The journey so far…. J Conserv Dent. 2010;13:167–8. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.73373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poorni S, Ramachandran S, Rooban T, Kumar PM. Contributions of Indianconservative dentists and endodontists to the Medline database during 1996-2009: A bibliometric analysis. J Conserv Dent. 2010;13:169–72. doi: 10.4103/0972-0707.73374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. [Last accessed on 2011 Dec 23]. Available from: http://icmr.nic.in/ethical_guidelines.pdf .

- 4. [Last accessed on 2011 Dec 23]. Available from: http://www.who.int/topics/epidemiology/en/

- 5.Sackett DL. Clinical epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 1969;89:125–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tugwell P, Bennett KJ, Sackett DL, Haynes RB. The measurement iterative loop: A framework for the critical appraisal of need, benefits and costs of health interventions. J Chronic Dis. 1985;38:339–51. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(85)90080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Colton T. Statistics in Medicine. Boston: Little, Brown and Co; 1974. pp. 66–73. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: What it is and what itisn’t. Br Med J. 1996;312:71–2. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sackett D, Straus S, Richardson W. Evidence-Based Medicine: How to Practice and Teach EBM. 2nd ed. London, England: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faggion CM, Jr, Tu YK. Evidence-based dentistry: A model for clinical practice. J Dent Educ. 2007;71:825–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rudan I, El Arifeen S, Black RE, Campbell H. Childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea: Setting our priorities right. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:56–61. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70687-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]