Abstract

Background

With the advent and widespread use of highly active antiretroviral therapy for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), persons living with HIV/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) are living good quality, longer, and healthier lives. Many couples affected by HIV, both serodiscordant and seroconcordant, are beginning to consider options for safer reproduction. The aim of this study was to assess the reproductive health concerns among persons living with HIV/AIDS in the Niger Delta of Nigeria.

Methods and results

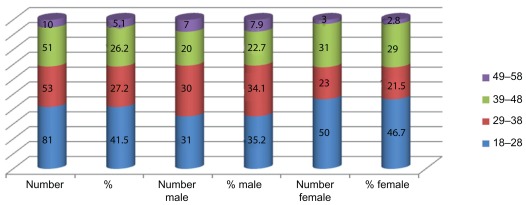

The subjects were aged 18–58 (mean 41.25 ± 11.50) years, with 88 males (45.1%) and 107 females (54.9). Of the 195 subjects studied, 111 (56.9%) indicated a desire to have children. The main reasons for wanting to procreate included ensuring lineage continuity and posterity (52.3%), securing relationships (27.0%), and pressure from relatives to reproduce (20.7%). Single subjects were more inclined to have children (76.3%) compared with married (51.5%), widowed (18.2%), and separated/divorced subjects (11.1%, P = 0.03). Of the 111 subjects who indicated their desire to have children, women were more inclined to have children (64.5%) than men (47.7%). The major concern among the 84 (43.1%) subjects not desiring more children were the fear of infecting a serodiscordant partner and baby (57.1%), fear of dying and leaving behind orphans (28.6%), and fear that they may become too ill and unable to support the child financially (14.3%). Persons with no formal education were more likely to have children irrespective of their positive HIV status (66.7%) than persons educated to tertiary education level (37.0%, P = 0.01). Of 111 subjects who desired to have children, only 58% had attended reproductive health counseling with HIV counselors. Reasons for not seeking advice were anticipated negative reactions and discrimination from counselors. A significant number of subjects were only aware of some of the reproductive health options available to reduce the risk of infecting their partners and/or baby, such as artificial vaginal insemination, intrauterine insemination, cesarean section, avoidance of breast feeding, and offering prenatal pre-exposure prophylaxis to the fetus. They were unaware of other options, such as sperm washing, in vitro fertilization, and intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Of the 43.1% not anticipating more children, 36.9% were anticipating adoption.

Conclusion

Our study has shown that a significant number of HIV-infected persons in the Niger Delta of Nigeria desire to have children irrespective of their positive serostatus. There is the need to support the sexual and reproductive rights of HIV-infected individuals. Additional training needs to be offered to HIV counselors on evidence-based best and affordable practices regarding reproductive health issues among persons living with HIV. Policies that support availability and accessibility to relevant reproductive and sexual health services, including contraception and procreation, need to be developed. Public enlightenment programs on HIV are needed to reduce the stigmatization that HIV-infected persons face from family members and their communities.

Keywords: reproductive health, human immunodeficiency virus, low income, Niger Delta, Nigeria

Introduction

Availability and use of antiretroviral drugs has changed the landscape of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), bringing about a change in the perception of HIV from an incurable deadly disease to a chronic manageable illness. As effective HIV treatments become more widespread, HIV-infected individuals are living longer and healthier lives. Many couples affected by HIV, both serodiscordant and seroconcordant, are considering options for safer reproduction. A large body of evidence suggests that reproductive technologies can help HIV-affected couples to conceive safely with minimal risk of HIV transmission to their partner and baby. However, for most couples, particularly those living in low-income countries of sub-Saharan Africa, such technologies are neither geographically nor economically accessible.1–5 With HIV now considered to be a chronic manageable disease, attention is shifting to offering and improving quality of life, particularly by provision of reproductive health options/care to men and women living with HIV-1. Many HIV-infected men and women are now expressing their desire to become parents. Assisted reproductive technologies, including intrauterine insemination, in vitro fertilization, and intracytoplasmic sperm injection in combination with semen washing, have been used to decrease the risk of HIV-1 transmission in HIV- 1-infected discordant couples involving an HIV-1-infected man.6 Previous reports indicate that in HIV-positive men taking highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), the seminal viral load is decreased but not eliminated, and fertilization should be achieved through sperm washing to offer maximum protection for the uninfected female. Pregnant HIV-positive women on antiretroviral medication have a reduced risk of transmitting the virus, but should still be advised about the possibility to limit further the chances of infecting their infant through elective cesarean section.7–10 HIV serodiscordant couples with a strong desire for child-bearing have a dilemma of risking HIV infection or infecting their spouse. Some risk transmission of HIV infection to reproduce.11 Over two-thirds of 104 surveyed couples wanting to procreate reported having unprotected sex with their partner in the past 6 months. Most respondents, regardless of serostatus, said that viral load testing and awareness of post-exposure prevention had no effect on their condom use.12

A paucity of interventions targeting serodiscordant couples on contraceptive choices is at odds with a strong cultural importance in Africa attached to having children. HIV discordance in Nigeria creates a serious dilemma in decision-making by couples about fertility. Stigma, discrimination, and nondisclosure fuel HIV transmission between partners. The aim of this study was to assess the reproductive health concerns of persons living with HIV/AIDS in the Port Harcourt area of the Niger Delta of Nigeria.

Port Harcourt, capital of the Rivers state in southern Nigeria, is cosmopolitan, oil-rich, and has people from all parts of the country. The population of Port Harcourt was estimated at 1,620,214 in 2007. The Niger Delta of Nigeria was selected for this study for several reasons. Firstly, the area is a cosmopolitan area with people from all parts of Nigeria. Secondly, the seroprevalence rate in this area is similar to that of the Nigeria national overall average prevalence of 4.6% reported for antenatal women in 2008.13 Thirdly, a study to investigate the prevalence of HIV among antenatal women in the area between 2005–2007 has indicated a rising prevalence of the disease.14 Pregnant women are considered a sentinel population because they are a relatively unselected group for whom prevalence data may be extended to the general sexually active heterosexual population.15

Materials and methods

Study population

From January 2007 to August 2007, we consecutively recruited and obtained informed consent from 195 persons living with HIV and enrolled into the adult and Prevention of Mother To Child Transmission of HIV program (PMTCT) at the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital. The hospital is a 500-bed tertiary health facility providing specialist HIV care and support to persons living with HIV/AIDS in the Niger Delta of Nigeria. The hospital is a center for adult antiretroviral therapy and PMTCT programs assisted by the Federal Government of Nigeria. HIV-infected persons are offered regular counseling on healthy living, reproductive health options, treatment adherence, and serodiscordance at both centers. We used a prevalidated,16 structured interviewer- administered anonymous questionnaire with both open-ended and close-ended questions to collect quantitative data on baseline characteristics and reproductive health concerns, ie, age, gender, level of educational attainment, sexual and contraceptive behavior, role of stigma (family, friends, and health care workers) on fertility decisions, whether they have had discussions with health workers about pregnancy and contraception, their desire to have children, and how their knowledge about mode of transmission of HIV has influenced their fertility decisions, from 195 consecutively recruited persons living with HIV/AIDS. Inclusion criteria included age 18–58 years (all subjects were ≤58 years), confirmed HIV-positive serostatus for more than 6 months, and willingness to give informed consent to partake in the study. We limited the study to people of reproductive age. Fertility behavior in Nigeria is conditioned by both biological and social factors. And as in other traditional African societies, several factors have contributed to sustain relatively high levels of fertility in Nigeria. These factors include a high level of infant and child mortality, child-bearing within much of the reproductive life span, low use of contraception, and the high social value placed on child-bearing. In the face of a perceived high infant and child mortality, fear of extinction encourages high rates of procreation in the hope that some of the births will survive to carry on the lineage. Use of modern contraception is traditionally considered unacceptable because it violates the natural process of procreation. The available evidence suggests that there have been changes in these sociocultural factors over time. Age at marriage appears to have increased when viewed at the national level. Use of modern contraception has also increased, and improved education (especially of women) appears to have gradually eroded some of the traditional value placed on child-bearing. The study participants comprised 88 males (45.1%) and 107 females (54.9). The questionnaire was administered by trained HIV counselors. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Ethical approval was obtained from the PMTCT and adult treatment programs at the University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Nigeria.

Statistical analysis

Data were entered and analyzed using statistical package SPSS version 9 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). Statistical analysis included descriptive analysis of the mean and standard deviation. Chi-square analysis was used to determine factors associated with the desire to have children. The main predictors of the desire to have children were adjusted for age, marital status, level of educational attainment, and discussion with health care workers about contraception. A P value of ≤0.05 was considered to be significant in all statistical analyses.

Results

The reproductive health concerns of 195 persons living with HIV/AIDS in the Niger Delta of Nigeria were studied. The age and gender distribution of the subjects is shown in Table 1. Of the subjects studied, 111 (56.9%) indicated their desire to have children. Single subjects were more inclined to have children (76.3%) than married (51.5%), widowed (18.2%), and separated/divorced subjects (11.1%), (P = 0.03). Of the 111 subjects who indicated their desire to have children, women were more inclined to have children (64.5%) than men (47.7%). Persons with no formal education were more likely to have children irrespective of their positive HIV status (66.7%) than persons educated to tertiary education level (37.0%), as can be seen in Table 1 (P = 0.01). Table 1 shows data on the desire of subjects to have children based on marital status, gender, and level of educational attainment.

Table 1.

Desire to have children based on marital status, gender, and level of educational attainment

| Characteristics | Subjects (n) | Number wanting children | % wanting children | χ2 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 72 | 55 | 76.3 | 45.1 | 0.03 |

| Married | 103 | 53 | 51.5 | ||

| Widowed | 11 | 2 | 18.2 | ||

| Separated | 9 | 1 | 11.1 | ||

| Gender | |||||

| Men | 88 | 42 | 47.7 | 36.3 | 0.05 |

| Women | 107 | 69 | 64.5 | ||

| Educational status | |||||

| Nonformal | 66 | 44 | 66.7 | 66.5 | 0.01 |

| Primary | 59 | 31 | 52.5 | ||

| Secondary | 43 | 26 | 60.5 | ||

| Tertiary | 27 | 10 | 37.0 | ||

| |||||

The main reasons for wanting to procreate included ensuring lineage continuity and posterity (52.3%), securing relationships (27.0%), and pressure from relatives to reproduce (20.7%), as shown in Table 2. Of the 111 subjects who desired to have children, only 58% had received reproductive health counseling from HIV counselors. Reasons for not seeking advice were anticipated negative reactions and discrimination from the counselors. The majority of subjects were only aware of some reproductive health options available to reduce the risk of infecting their partners and/or baby, such as artificial vaginal insemination, intrauterine insemination, cesarean section, avoidance of breast feeding, and prenatal pre-exposure prophylaxis for the fetus. They were unaware of other options, such as sperm washing, in vitro fertilization, and intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Of the 43.1% not anticipating more children, 36.9% were anticipating adoption. The major concerns among the 84 (43.1%) subjects not desiring to have more children were fear of infecting a serodiscordant partner and baby (57.1%), fear of dying and leaving behind orphans (28.6%), and fear that they may become too ill and unable to support the child financially (14.3%). Reproductive health concerns among subjects not desiring children is shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Reasons why subjects living with human immunodeficiency virus want to have children

| Reasons for wanting children | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Ensuring lineage continuity and posterity | 58 (52.3) |

| Securing relationships | 30 (27.0) |

| Pressure from relatives to reproduce | 23 (20.7) |

Table 3.

Reproductive health concerns among subjects not desiring to have more children

| Reproductive health concerns | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Fear of infecting partner and or baby | 48 (57.1) |

| Fear of dying and leaving behind orphans | 24 (28.6) |

| Fear of becoming too ill and unable to support child financially | 12 (14.3) |

Discussion

Our study indicated that over half of HIV-infected subjects desire to have children irrespective of their HIV status. Women were more inclined to have children than men. Persons with no formal education were more inclined to have children irrespective of their positive HIV status than persons educated to tertiary education level. The main reasons for wanting a child included ensuring lineage continuity and posterity, securing relationships, and pressure from relatives to reproduce. There may be several reasons for this association, including better educated people generally having greater access to information, particularly the mode of transmission of HIV, than those who have less formal education, and are more likely to make informed decisions and act on information given. In addition, better educated people generally have better jobs and greater access to money and other resources which can help them lead healthier lives. Also, single persons living with HIV were more likely to want to have children than married, separated, and widowed subjects. Regardless of interpersonal and public health concerns, studies in both resource-rich and resource-limited settings suggest that HIV-infected men and women desire children.17–19 In addition, in resource-limited settings, couples often desire larger families. The reasons for this are debated, but likely include, among others, the strong cultural attachment to having children, stigmatization associated with childlessness, role of children in inheritance, importance of children in agricultural economies, importance of childbearing on the status of women, the role of children as caretakers of the elderly, and high rates of infant mortality.20 A previous report indicates that 40% of HIV-infected women desire more children, and women with fewer children were more likely to become pregnant.21 There are several reasons why persons living with HIV/AIDS, particularly in low-income countries in Africa, want to procreate.

The major concern among the 84 (43.1%) not wanting to procreate was the fear of infecting a serodiscordant partner and baby, fear of dying and living behind orphans, and fear that they may become too ill to support the child financially. A previous report indicates that the major challenges faced by HIV-infected subjects not desiring to procreate included the risk of HIV transmission to partner and child and the failure of health systems to offer safe methods of reproduction. 22 Identifying the determinants of the decision to have children among serodiscordant couples will help in setting reproductive intervention priorities in resource-poor countries. The gender of the HIV-positive partner affects the factors associated with a desire for children. Interventions targeting serodiscordant couples should explore contraceptive choices, the cultural importance of children, and partner communication.23

Given the importance of procreation in African settings and the lack of assisted reproduction services, HIV-infected couples are faced with a serious dilemma about making an informed decision to procreate. We observed that, of the 111 subjects who desired children, only about half of them had sought reproductive health counseling from HIV counselors. Reasons for not seeking counseling were anticipated negative reactions and stigmatization from the counselors resulting from their negative attitude towards unprotected sexual activity and child-bearing by HIV-infected couples. HIV-infected individuals and their partners require education and counseling regarding HIV disease and reproduction, and HIV counselors do not have access to evidence-based information that the HIV-infected population desperately need to enable them to make informed reproductive health decisions. A previous report suggests that there is a need to draw up a protocol for reproductive counseling of HIV-infected people wanting to have babies.24 HIV counselors should realize that simply encouraging HIV-infected couples to abstain from procreation may no longer be a realistic strategy, particularly in the Niger Delta of Nigeria where there is a strong cultural attachment to having children. In the absence of counseling that recognizes the desire and importance of having children, couples may knowingly take on the risks of transmission in order to have children. Sharing our evidenced-based best practices about HIV transmission and reproductive health options while recognizing patient goals may help couples minimize the risk and reduce the harm of unprotected sex. However, the great risks taken by HIV-infected persons desiring to procreate could be minimized through counseling and close monitoring by reproductive health care providers. HIV-related stigma and discrimination poses an enormous barrier to the fight against AIDS. Fear of discrimination often prevents people from getting tested, seeking treatment, and admitting their HIV status publicly. Given that laws and policies alone cannot reverse the stigma that surrounds HIV infection, AIDS education in the Niger Delta of Nigeria needs to be scaled up to combat the ignorance that causes people to discriminate. The fear and prejudice that lies at the core of HIV and AIDS discrimination needs to be tackled at both community and national levels. There is a strong ethical imperative to support the sexual and reproductive health needs of HIV-infected individuals, allowing them to make informed decisions about their reproductive health. Increasingly, fertility clinics in developed countries are offering their services to HIV-serodiscordant couples where the woman is seropositive and in HIV-seroconcordant relationships. Reproductive health care workers in the Niger Delta can learn from evidence-based best practices in the developed world to ensure that their counterparts in more developed countries, particularly HIV-infected persons in the Niger Delta of Nigeria, can access the best quality reproductive and sexual health service. Recent advances in HIV clinical care and assisted reproduction technique procedures directed at reducing the risk of viral transmission during gamete transfer, particularly where good health care is available, have significantly reduced the risk of transmission of HIV among discordant couples to 1%–2%.25 Promotion of risk reduction counseling, screening for sexually transmitted diseases and lower genital tract disease, assessment of options for birth control, and preconception counseling should be integral components of gynecologic health care for HIV-infected women.26 Sperm washing and insemination lower the transmission risk for HIV-negative women who want to have children with HIV-positive men. Data from the European experience which included 14 years of follow-up for 1036 serodiscordant couples with an HIV-positive male resulted in 580 pregnancies and no HIV seroconversions.27

Our study indicated that reproductive health knowledge among HIV-infected subjects desiring to procreate was limited. Subjects were unaware of the reproductive options, such as sperm washing, in vitro fertilization, and intracytoplasmic sperm injection, available to reduce the risk of infecting their partners and/or baby. A significant number of men taking HAART have a lower seminal concentration of HIV, and sexual transmission may be reduced. However, a certain percentage of aviremic men retain viral presence in semen, and unprotected intercourse to achieve fertilization must be discouraged because it carries the risk of sexual transmission of the virus. HIV-discordant couples should be informed that sperm washing can remove HIV from semen, allowing conception without the risk of infection for the seronegative female and eventually the child. In HIV-positive women, perinatal transmission of HIV can be curtailed to less than 2% by using HAART to decrease maternal viral load and offering prenatal pre-exposure prophylaxis of the fetus, and elective cesarean section. Each intervention carries specific risks and benefits. The contribution of each preventive arm in achieving fetal protection can only be crudely measured and optimal obstetric management must involve discussion with the pregnant woman of the pros and cons of each strategy.

HIV-affected couples who want to have children present at least three distinct and daunting clinical challenges. The first is dealing with the stigma arising from the negative attitudes of many health care providers towards sexual activity and child-bearing by HIV-infected couples28–30 and stigmatization from immediate family members and society. 31 The second is maintaining the mother’s health before, during, and after pregnancy. The third is preventing vertical transmission from mother to child as well as preventing HIV transmission to the partner in a serodiscordant relationship. Several approaches have been suggested to reduce the risk of horizontal transmission for HIV-affected couples who want to conceive children. These approaches includes the use of male sperm washing, intrauterine insemination, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, screening, and pretreatment for sexually transmitted infections, delay in procreation until viral load is controlled, limited, timed unprotected sexual encounters, female artificial insemination, self-insemination, and circumcision. Experience among couples in whom the male was HIV-seropositive who underwent assisted reproductive technology in order to attain family goals while minimizing the risk of HIV transmission indicated that all female recipients tested seronegative for HIV at 3 and 6 months post-embryo transfer. All eight babies delivered tested seronegative for HIV at birth and 3 months postpartum and that reproductive technology should be considered for HIV serodiscordant couples who desire to have children in order to minimize the risk of viral infection.32

The findings of our study show that many people play a role in the reproductive decision-making of persons living with HIV/AIDS, ie, relatives who use traditional norms to encourage procreation; health workers who violate the autonomy and human rights of HIV-infected persons by using their medical knowledge to discourage clients from child-bearing by preaching mandatory contraception,33 and a health care system that does not recognize or meet the sexual and reproductive needs of its clients.34 Health care providers in Africa must realize that it is their responsibility to offer information to enable HIV-infected persons to arrive at their own informed decisions on their reproductive and sexual health needs, regardless of the opinion of the health professional. Similarly, there may be a need to offer additional training to enable counselors to offer evidence-based sexual and reproductive health information to their clients. Reproductive health policies in the HIV/AIDS era are lacking in most African settings. It is recommended that serodiscordant couples who desire to have children should undergo assisted fertility treatment, such as sperm washing, intrauterine insemination, and in vitro fertilization, to avoid HIV transmission to their partners.35,36 However, cost implications represent a major issue affecting the feasibility of offering assisted fertility treatment, particularly among people of low socioeconomic status. There is a major challenge with the development of evidenced-based, cost-effective, and best practice guidelines, both locally and nationally, to optimize the sexual and reproductive health service provided for persons living with HIV/AIDS, particularly in the Niger Delta of Nigeria. In resource-limited settings, couples should be counseled on ovulation cycles and may engage in timed unprotected sex only during the fertile period of the woman’s monthly cycle to facilitate conception while reducing the number of exposures. If the man is HIV-negative with a positive partner, partners can be taught artificial insemination, timed to the woman’s fertile period. For couples in which both partners are positive, there may be need for careful and informed natural conception when their viral loads have fallen to below the level of detection.

Conclusion

Our study has shown that a significant number of HIV-infected persons in the Niger Delta of Nigeria desire to have children irrespective of their positive serostatus. There is the need to support the sexual and reproductive rights of HIV-infected individuals. Additional training needs to be offered to HIV counselors on evidence-based best and affordable practices regarding reproductive issues among persons living with HIV. There is an urgent need to develop policies that support availability and accessibility to relevant reproductive and sexual health services, including contraception and procreation, coupled with the need for a public enlightenment program on HIV to reduce the stigmatization that HIV-infected persons in the Niger Delta face from family members and their communities.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Matthews LT, Mukherjee JS. Strategies for harm reduction among HIV-affected couples who want to conceive. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(1):5–11. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9551-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohl J, Partisani M, Wittemer C, Lang JM, Viville S, Favre R. Encouraging results despite complexity of multidisciplinary care of HIV-infected women using assisted reproduction techniques. Hum Reprod. 2005;20(11):3136–3140. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dei185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen VM, Wilson RD, Cheung A Genetics Committee of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC); Reproductive Endocrinology Infertility Committee of the Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada (SOGC) Pregnancy outcomes after assisted reproductive technology. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2006;28(3):220–250. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(16)32112-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sauer MV, Wang JG, Douglas NC, et al. Providing fertility care to men seropositive for human immunodeficiency virus: reviewing 10 years of experience and 420 consecutive cycles of in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection. Fertil Steril. 2009;91(6):2455–2460. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andersen AN, Gianaroli L, Felberbaum R, de Mouzon J, Nygren KG. Assisted reproductive technology in Europe, 2002. Results generated from European registers by ESHRE. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(7):1680–1697. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Leeuwen E, Repping S, Prins JM, Reiss P, van der Veen F. Assisted reproductive technologies to establish pregnancies in couples with an HIV-1-infected man. Neth J Med. 2009;67(8):322–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Semprini AE, Vucetich A, Hollander L. Sperm washing, use of HAART and role of elective Caesarean section. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2004;16(6):465–470. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200412000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Semprini AE, Fiore S. HIV and reproduction. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2004;16(3):257–262. doi: 10.1097/00001703-200406000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barreiro P, Castilla JA, Labarga P, Soriano V. Is natural conception a valid option for HIV-serodiscordant couples? Hum Reprod. 2007;22(9):2353–2358. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matthews LT, Baeten JM, Celum C, Bangsberg DR. Periconception pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV transmission: benefits, risks, and challenges to implementation. AIDS. 2010;24(13):1975–1982. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833bedeb. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beyeza-Kashesya J, Kaharuza F, Mirembe F, Neema S, Ekstrom AM, Kulane A. The dilemma of safe sex and having children: challenges facing HIV sero-discordant couples in Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2009;9(1):2–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.van der Straten A, Gómez CA, Saul J, Quan J, Padian N. Sexual risk behaviours among heterosexual HIV serodiscordant couples in the era of post-exposure prevention and viral suppressive therapy. AIDS. 2000;14(4):F47–F54. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200003100-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Federal Ministry of Health, Nigeria. Report on the 2008 National HIV seroprevalence sentinel survey among pregnant women attending antenatal clinics in Nigeria. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tobin-West CI, Okoh DA. A three-year review of the pattern of HIV infection among pregnant women attending Braithwaite Memorial Specialist Hospital, Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Port Harcourt Medical Journal. 2009;4(1):2. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saphonn V, Hor LB, Ly SP, Chhuon S, Saidel T, Detels R. How well do antenatal clinic (ANC) attendees represent the general population? A comparison of HIV prevalence from ANC sentinel surveillance sites with a population-based survey of women aged 15–49 in Cambodia. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(2):449–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akani CI, Erhabor O. Rate, pattern and barriers of HIV sero-status disclosure in a resource limited setting in the Niger Delta of Nigeria. Trop Doct. 2006;36(2):87–89. doi: 10.1258/004947506776593378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matthews LT, Mukherjee JS. Strategies for harm reduction among HIV-affected couples who want to conceive. AIDS Behav. 2009;13( Suppl 1):5–11. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9551-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frodsham LC, Boag F, Barton S, Gilling-Smith C. Human immunodeficiency virus infection and fertility care in the United Kingdom: Demand and supply. Fertil Steril. 2006;85(2):285–289. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.07.1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Myer L, Morroni C, Rebe K. Prevalence and determinants of fertility intentions of HIV-infected women and men receiving antiretroviral therapy in South Africa. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2007;21(4):278–285. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sonko S1. Fertility and culture in Sub-Saharan Africa: A review. Int Soc Sci J. 1994;46(3):397–411. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen S, Meinzen-Derr J, Kautzman M, et al. Sexual behavior of HIV discordant couples after HIV counselling and testing. AIDS. 2003;17(5):733–740. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200303280-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beyeza-Kashesya J, Kaharuza F, Mirembe F, Neema S, Ekstrom AM, Kulane A. The dilemma of safe sex and having children: challenges facing HIV serodiscordant couples in Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2009;9(1):2–12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Beyeza-Kashesya J, Ekstrom AM, Kaharuza F, Mirembe F, Neema S, Kulane A. My partner wants a child: a cross-sectional study of the determinants of the desire for children among mutually disclosed sero-discordant couples receiving care in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:247. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Barreiro P, Duerr A, Beckerman K, Soriano V. Reproductive options for HIV-serodiscordant couples. AIDS Rev. 2006;8(3):158–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zutlevics T. Should ART be offered to HIV-serodiscordant and HIV-seroconcordant couples: an ethical discussion? Hum Reprod. 2006;21(8):1956–1960. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aaron E, Levine AB. Gynecologic care and family planning for HIV- infected women. AIDS Read. 2005;15(8):426–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bujan L, Hollander L, Coudert M, et al. CREAThE network. Safety and efficacy of sperm washing in HIV-1-serodiscordant couples where the male is infected: results from the European CREAThE network. AIDS. 2007;21(14):1909–1914. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282703879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shelton JD, Peterson EA. The imperative for family planning in ART therapy in Africa. Lancet. 2004;364(9449):1916–1918. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17489-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Bruyn M. Living with HIV: Challenges in reproductive health care in South Africa. Afr J Reprod Health. 2004;8(1):92–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paiva V, Filipe EV, Santos N, Lima TN, Segurado A. The right to love: The desire for parenthood among men living with HIV. Reprod Health Matters. 2003;11(22):91–100. doi: 10.1016/s0968-8080(03)02293-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC. HIV testing attitudes, AIDS stigma and voluntary HIV counselling and testing in a black township in Cape Town, South Africa. Sex Transm Infect. 2003;79(6):442–447. doi: 10.1136/sti.79.6.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peña JE, Klein J, Thornton MH, 2nd, Sauer MV. Providing assisted reproductive care to male haemophiliacs infected with human immunodeficiency virus: preliminary experience. Haemophilia. 2003;9(3):309–316. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2516.2003.00748.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stern AM. Sterilized in the name of public health: race, immigration and reproductive control in modern California. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(97):1128–1138. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.041608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sauer MV. Providing fertility care to those with HIV: time to re-examine healthcare policy. Am J Bioeth. 2003;3(1):33–40. doi: 10.1162/152651603321611944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Semprini AE, Levi-Setti P, Bozzo M, et al. Insemination of HIV-negative women with processed semen of HIV-positive partners. Lancet. 1992;340(8831):1317–1319. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92495-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohl J, Partisani M, Wittemer C, et al. Assisted reproduction techniques for HIV serodiscordant couples: 18 months of experience. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(6):1244–1249. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]