Abstract

The carcinogenic liver fluke, Opisthorchis viverrini, requires Bithynia snail intermediate hosts in its life cycle. However, the prevalence of O. viverrini in snail intermediate hosts is typically low (< 1%). Here, we examined B. siamensis goniomphalos from 48 localities in Thailand and The Lao People?s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR) and reported high-prevalence levels of O. viverrini. The highest-prevalence levels per locality were 6.93% (mean = 3.04%) in Thailand and 8.37% (mean = 2.01%) in Lao PDR; 4 of 13 localities examined showed prevalence higher than any prevalence previously recorded. The number of cercariae infecting snails and their prevalence were positively correlated with the size of the snails. High prevalence occurred in the Songkram River wetland (Thailand) and the Nam Ngum River wetland (Lao PDR). Our results show that transmission of O. viverrini from humans as well as animal reservoir hosts to snail intermediate hosts is ongoing and potentially increasing in endemic areas across Thailand and Lao PDR.

Introduction

The liver fluke Opisthorchis viverrini is a food-borne trematode pathogen in the Mekong Region in Southeast Asia, where it infects at least 9 million individuals. 1 Not only is O. viverrini itself pathogenic, it is classified as a type one carcinogen and is the major causative agent for cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) in the area. 2 In northeast Thailand and The Lao People?s Democratic Republic (Lao PDR), O. viverrini is a major medical problem, with prevalence rates commonly reaching 30% or more in rural populations in Thailand and over 80% in Lao PDR. 3,4

The life cycle of O. viverrini includes the freshwater snails Bithynia funiculata, B. siamensis siamensis, and B. s. goniomphalos as first intermediate hosts, with the latter occurring in northeast Thailand and Lao PDR. A wide variety of freshwater cyprinid fishes act as second intermediate hosts. Humans are the most important final hosts, although cats and dogs can harbor adult worms. 1

The prevalence of O. viverrini cercariae in Bithynia snail hosts is reportedly very low, ranging from 0.03% to 2.47%. 5–11 To date, the prevalence of O. viverrini infection in B. s. goniomphalos has been found to range between 0.03% and 1.3% in Thailand 6–9 and 0.5% and 2.47% in Lao PDR. 11–13 This finding is in contrast to the very high prevalence in cyprinid fish (90–95%) and humans. 14–17

The three Bithynia taxa, which are sexually reproducing, are the critical amplifying components in the transmission of O. viverrini, and they are a controlling factor for the potential spread of opisthorchiasis and CCA. Here, we examine the prevalence and cercarial shedding of O. viverrini in B. s. goniomphalos in Thailand and Lao PDR and determine their association with snail size.

Materials and Methods

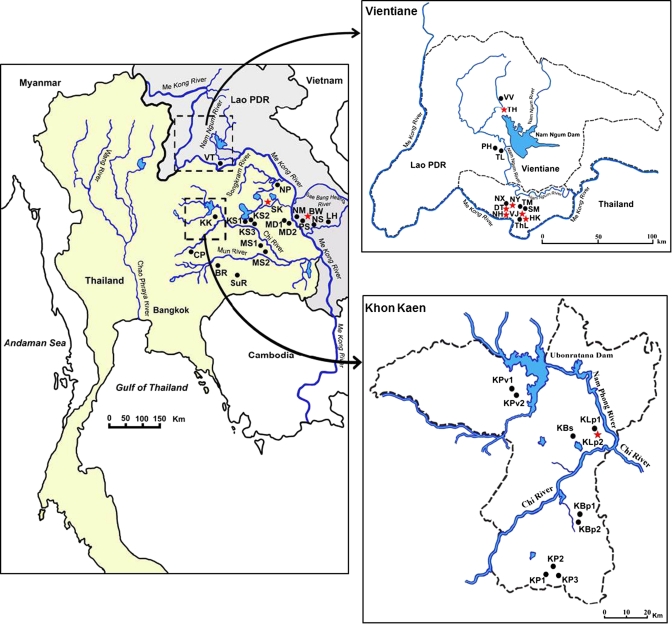

Samples of B. s. goniomphalos were collected from five major wetlands: the Mun, Chi, and Songkram Rivers basins in Thailand and the Nam Ngum and Sae Bang Heang Rivers basins in Lao PDR. A total of 5,790 snails from 25 localities were collected in Thailand from nine northeastern provinces (Figure 1). In Lao PDR, a total of 5,848 snails from 23 localities were collected in Vientiane and Savannakhet provinces. The snails were collected by handpicking and scooping, and they were identified morphologically according to the works by Brandt, 18 Upatham and others, 19 and Chitramvong. 20 The shell size of each snail was measured under a dissecting microscope. Snail samples were placed individually into plastic containers for cercarial shedding. To estimate the number of cercariae released per day, O. viverrini-positive snails were kept in the dark for 12 hours and then exposed to light for 12 hours. Cercariae released from each snail during both the dark and light phases were counted under a dissecting microscope to calculate the number of cercariae per snail per day. The cercariae from infected snails were identified by light microscopy and confirmed by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). 21 A random sample of cercariae from snails collected from Thailand and Lao PDR were passed to fish (silver barb; Barbonymus gonionotus) to obtain O. viverrini metacercariae, which were fed to hamsters to produce adult worms for definitive identification.

Figure 1.

The study area showing sampling localities for B. s. goniomphalos in different wetlands in Thailand and Lao PDR. Codes for sampling localities are as follows: Khon Kaen (KK), Buri Ram (BR), Surin (SuR), Chaiyaphum (CP), Mahasarakham (MS1 and MS2), Kalasin (KS1, KS2, and KS3), Mukdaharn (MD1 and MD2), Sakon Nakhon (SK), Nakho Phanom (NP), La Ha Nam (LH), Na Seng (NS), Pon Sa-ard (PS), Hau Maung Neang (HM), Bueng Wa (BW), and Vientiane (VT). Expanded map of Vientiane (VT): Veiang Jarean (VJ), That Luang (ThL), Na Hae (NH), Dongnatong (DT), Sa Pang Muek (SM), Tanmi Xai (TM), Nong Pra Ya (NY), Naxaithong (NX), Thalad (TL), Phonhong (PH), Tha Heur (TH), and Vang Vieng (VV). Expanded map of Khon Kaen (KK): Ban Phai (KBp1 and KBp2), Phon (KP1, KP2, and KP3), Sa-ard (KBs), Lerngpleuy (KLp1 and KLp2), and Phu Wiang (KPv1 and KPv2). ⋆ = Sites positive for O. viverrini; • = sites negative for O. viverrini.

Results

Snail samples were collected between 2008 and 2011 when snails were available, especially during winter months (November to January). Four of five wetlands contained B. s. goniomphalos infected with O. viverrini cercariae (Figure 1). In Thailand, infected snails were found at four (16%) localities, with an average of 3.04%; in Lao PDR, infected snails were found at nine (39.13%) localities, with an average of 2.01%. In the Nam Ngum wetland, B. s. goniomphalos was found to be infected at eight localities: one locality in the Sae Bang Heang wetland in Lao PDR and three localities in the Songkram wetland: one locality in the Chi wetland in Thailand.

The difference in the proportion of infected sites between Thailand and Lao PDR approached significance (Fisher's exact test, one-tailed P = 0.069). Of the total number of 48 localities examined, 13 contained snails infected with O. viverrini. For infected snails, prevalence in Lao PDR ranged from 0.37% to 8.37% (Table 1). Of the nine localities with snails positive for O. viverrini, two localities from the Nam Ngum wetland showed higher prevalence than any previously recorded. In Thailand, prevalence ranged from 0.22% to 6.93%, and of the four positive localities, two localities from the Songkram wetland showed higher prevalence than any previously recorded. All localities with exceptionally high prevalence were rice fields with very shallow water.

Table 1.

Collection localities, number of B. s. goniomphalos snails examined, and number and percent of snails infected with O. viverrini cercariae

| Wetland | Province | Habitat | Locality | Total snails | No. positive (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thailand | |||||

| Mun (MR) | Buri Ram (BR) | Reservoir | Mueang district (BR) | 380 | 0 (0.00) |

| Mun (MR) | Surin (SuR) | Fish pond | Nadee subdistrict, Mueang district (SuR) | 110 | 0 (0.00) |

| Chi (CR) | Chaiyaphum (CP) | Rice field | Chatturat District (CP) | 82 | 0 (0.00) |

| Chi (CR) | Mahasarakham (MS) | Rice field | Mahasarakham University (MS1) | 19 | 0 (0.00) |

| Chi (CR) | Mahasarakham (MS) | Pond | Kosum Phisai district (MS2) | 280 | 0 (0.00) |

| Chi (CR) | Khon Kaen (KK) | Rice field | Nong Chot, Phon district 1 (KP1) | 137 | 0 (0.00) |

| Chi (CR) | Khon Kaen (KK) | Pond | Nong Chot, Phon district 2 (KP2) | 257 | 0 (0.00) |

| Chi (CR) | Khon Kaen (KK) | Rice field | Nong Chot, Phon district 3 (KP3) | 252 | 0 (0.00) |

| Chi (CR) | Khon Kaen (KK) | Ban Phai district 1 (KBp1) | 213 | 0 (0.00) | |

| Chi (CR) | Khon Kaen (KK) | Ban Phai district 2 (KBp2) | 311 | 0 (0.00) | |

| Chi (CR) | Khon Kaen (KK) | Fish pond | Sa-ard, Mueang district (KBs) | 335 | 0 (0.00) |

| Chi (CR) | Khon Kaen (KK) | Rice field | Lerngpleuy, Mueang district 1 (KLp1) | 164 | 0 (0.00) |

| Chi (CR) | Khon Kaen (KK) | Lerngpleuy, Mueang district 2 (KLp2) | 83 | 1 (1.20) | |

| Chi (CR) | Khon Kaen (KK) | Phu Wiang district 1 (KPv1) | 150 | 0 (0.00) | |

| Chi (CR) | Khon Kaen (KK) | Phu Wiang district 2 (KPv2) | 361 | 0 (0.00) | |

| Chi (CR) | Kalasin (KS) | Rice field | Lam Pao Dam, Mueang district 1 (KS1) | 87 | 0 (0.00) |

| Chi (CR) | Kalasin (KS) | Lam Pao Dam, Mueang district 2 (KS2) | 74 | 0 (0.00) | |

| Chi (CR) | Kalasin (KS) | Pond | Suan Sa-on, Lam Pao Dam, Mueang district (KS3) | 85 | 0 (0.00) |

| Songkram (SR) | Mukdahan (MD) | Rice field | Mueang district (MD1) | 300 | 0 (0.00) |

| Songkram (SR) | Mukdahan (MD) | Steam | Dong Luang district (MD2) | 239 | 0 (0.00) |

| Songkram (SR) | Sakon Nakhon (SK) | Rice field | Nam Un Dam, Phang Khon district (SK) | 445 | 1 (0.22) |

| Songkram (SR) | Sakon Nakhon (SK) | 303 | 21 (6.93) | ||

| Songkram (SR) | Sakon Nakhon (SK) | 104 | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Songkram (SR) | Sakon Nakhon (SK) | 551 | 19 (3.45) | ||

| Songkram (SR) | Nakhon Phanom (NP) | Fish pond | Nonchan, Renu Nakhon district (NP) | 468 | 0 (0.00) |

| Total | 5,790 | 42 (0.73) | |||

| Lao PDR | |||||

| Sae Bang Heang (SbR) | Savannakhet (SV) | Rice field | La Ha Nam, Songkhone district (LH) | 37 | 0 (0.00) |

| Sae Bang Heang (SbR) | Savannakhet (SV) | Na Seng, Khanthabouly district (NS) | 172 | 0 (0.00) | |

| Sae Bang Heang (SbR) | Savannakhet (SV) | Pond | Pon Sa-ard, Khanthabouly district (PS) | 384 | 0 (0.00) |

| Sae Bang Heang (SbR) | Savannakhet (SV) | Hau Maung Neang, Khanthabouly district (HM) | 27 | 0 (0.00) | |

| Sae Bang Heang (SbR) | Savannakhet (SV) | Rice field | Bueng Wa, Khanthabouly district (BW) | 186 | 0 (0.00) |

| Sae Bang Heang (SbR) | Savannakhet (SV) | 404 | 9 (2.23) | ||

| Num Ngum (NR) | Vientiane (VT) | Rice field | Xaythany district (HK) | 180 | 8 (4.44) |

| Num Ngum (NR) | Vientiane (VT) | 203 | 17 (8.37) | ||

| Num Ngum (NR) | Vientiane (VT) | 1,031 | 17 (1.65) | ||

| Num Ngum (NR) | Vientiane (VT) | Veiang Jarean, Xaysettha district (VJ) | 485 | 5 (1.03) | |

| Num Ngum (NR) | Vientiane (VT) | Shallow lake | That Luang (ThL) | 172 | 0 (0.00) |

| Num Ngum (NR) | Vientiane (VT) | Fish pond | Ban Na Hae, Si Khot district (NH) | 261 | 3 (1.15) |

| Num Ngum (NR) | Vientiane (VT) | 302 | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Num Ngum (NR) | Vientiane (VT) | Rice field | Dongnatong, Sikhottabong district (DT) | 219 | 1 (0.46) |

| Num Ngum (NR) | Vientiane (VT) | Fish pond | Ban Sa Pang Muek, Xaythany district (SM) | 289 | 0 (0.00) |

| Num Ngum (NR) | Vientiane (VT) | Rice field | Ban Tanmi Xai, Chanthabuly district (TM) | 68 | 0 (0.00) |

| Num Ngum (NR) | Vientiane (VT) | Nong Pra Ya, Xaythany district (NY) | 271 | 1 (0.37) | |

| Num Ngum (NR) | Vientiane (VT) | Si Keut, Naxaithong district (NX) | 344 | 0 (0.00) | |

| Num Ngum (NR) | Vientiane (VT) | Ban Thalad, Keo Oudom district (TL) | 262 | 0 (0.00) | |

| Num Ngum (NR) | Vientiane (VT) | Na Gum, Phonhong district (PH) | 148 | 0 (0.00) | |

| Num Ngum (NR) | Vientiane (VT) | Dam | Tha Heur (TH) | 88 | 2 (2.27) |

| Num Ngum (NR) | Vientiane (VT) | 29 | 0 (0.00) | ||

| Num Ngum (NR) | Vientiane (VT) | Vang Vieng (VV) | 286 | 0 (0.00) | |

| Total | 5,848 | 63 (1.08) |

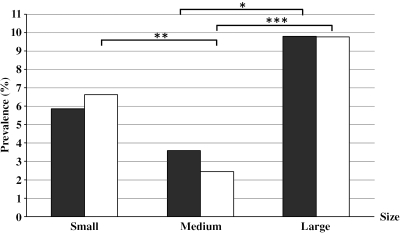

As shown in Figure 2 , large B. s. goniomphalos had a prevalence of 9.80% and 9.77% for length (> 10.0 mm) versus width (> 6.0 mm), respectively. Medium-sized snails (length = 8.1–10.0 mm, width = 5.1–6.0 mm) had prevalence of 3.59% and 2.45%, respectively, whereas small snails (length ≤ 8.0 mm, width ≤ 5.0 mm) had prevalence of 5.86% and 6.63%, respectively. There were significant positive trends that prevalence of O. viverrini correlated with the size of snails (χ22 = 6.4, P < 0.05 for length; χ22 = 24.9, P < 0.001 for width). Based on the width of the shell, large-sized B. s. goniomphalos have a significantly higher-prevalence level of O. viverrini than medium-sized individuals (χ22 = 24.4, P < 0.001) but small-sized snails also have a significantly higher prevalence than the medium-sized snails (χ22 = 8.7, P < 0.05). For length, large snails have significantly higher prevalence than medium-sized snails (χ22 = 4.9, P < 0.05), but there is no significant difference between small- and medium-sized snails (P > 0.05). Within a total of 55 infected snails, 22 were males (40%), and 33 were females (60%).

Figure 2.

Relationship between the prevalence of O. viverrini cercariae and shell size of B. s. goniomphalos. Black bars represent size class based on shell length (small ≤ 8.0 mm, medium = 8.1–10.0 mm, large ≥ 10.0 mm); white bars represent size class based on shell width (small ≤ 5.0 mm, medium = 5.1–6.0 mm, large ≥ 6.0). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

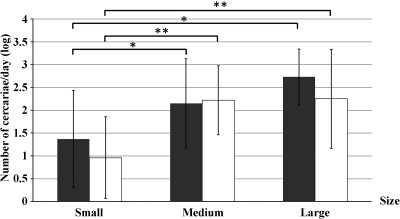

There were significant positive correlations between the number of cercariae shed per day and the shell size of B. s. goniomphalos (Kendall's τ_b = 0.399, P < 0.001 for length; τ_b = 0.309, P < 0.05 for width). The relationships between the number of cercariae shed per day and size classes for all positive snails from each wetland are shown in Figure 3. Smaller snails release significantly less cercariae per day than either medium or large snails (Fisher's Least Significant Difference [LSD] test, P < 0.05). No significant difference in the number of cercariae per day between snails (male and female) was observed (Mann–Whitney U test, P > 0.05)

Figure 3.

Number of O. viverrini cercariae produced per day in different size classes of B. s. goniomphalos. Black bars represent size class based on shell length (small ≤ 8.0 mm, medium = 8.1–10.0 mm, large ≥ 10.0 mm); white bars represent size class based on width of shell (small ≤ 5.0 mm, medium = 5.1–6.0 mm, large ≥ 6.0). Data shown are mean ± SD calculated from cercaria-positive snails (two-sample LSD test; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01).

Discussion

O. viverrini infection and its associated CCA represent one of the most important medical problems in the Mekong Region of Southeast Asia. 22,23 Current information on age-dependent infection indicates that many young adults are likely to develop CCA, continuing its personal and economic consequences well into the future. 1 Chemotherapy by using praziquantel is the usual means for large-scale parasite control as well as individual treatment. The efficacy of praziquantel is relatively high (90–95%), but reduced cure rates have been reported. 24 Reinfections, however, are a common phenomenon in many endemic areas. 25,26

An integrated prevention and control program based on health education plus sanitary improvement has been recommended in the past, 3 and more recently, it was recommended in the work by Sithithaworn and others 27,28 that targeted school children. One means for potentially reducing infection rates is control of the intermediate hosts. The wide variety of fish species susceptible to infection and their importance as a food source in the area make control at this level unlikely; however, only a single Bithynia species or subspecies acts as the first intermediate host in the infected areas, 29 making control at this level much more likely. To asses control potential, it is necessary to understand the dynamics of snail infection.

Contrary to information from cercarial shedding experiments to date that the prevalence of O. viverrini in B. s. goniomphalos is low (0.03–2.47%), 5–11 we found surprisingly high prevalence in different wetlands in Thailand and Lao PDR. These were up to three- to fourfold higher, with values of 6.93% in the Songkram wetland, Thailand, and 8.37% in the Nam Ngum wetland, Lao PDR, but not in the other wetlands examined.

High prevalence of O. viverrini has also been reported recently using PCR analyses, and prevalence was found to increase from 2.47% (determined by cercarial shedding) to 8.52% (determined by PCR) in B. s. goniomphalos in Lao PDR. 11 These results indicate that not all infected snails start shedding under laboratory conditions. This finding suggests that the high-prevalence levels that we detected by cercarial shedding may also underestimate the actual infection rate in snails, providing more evidence that prevalence of O. viverrini in B. s. goniomphalos is significantly higher than previously thought.

High prevalence in certain wetlands may relate to high transmission rates. Biological differences (for example, in fecundity) have previously been reported for O. viverrini from the Songkram wetland versus O. viverrini from the Nam Ngum wetland. 30 Whether high prevalence in these two wetlands correlate with high incidences of CCA is not known, but it has been recently reported that CCA incidence is the third highest in the Songkram wetland (Nakhon Phanom Province) after the Chi wetland. 31 O. viverrini prevalence is also reported to be high in the Songkram wetland. 15 No data for CCA incidence is available from the Lao PDR.

We report for the first time that the number of cercariae released is positively associated with B. s. goniomphalos size. Wider and smaller size class snails yielded higher-prevalence levels than middle-width snails. This finding, in part, supports a previous study by Upathum and Sukhapanth 5 on B. s. siamensis that found that the largest snails were the most heavily infected, although in this study, the smallest individuals were least heavily infested. Ngern-klun and others 10 found that higher-prevalence levels were observed in B. funiculata of length > 7 mm than ≤ 7 mm. However, a study by Chanawong and Waikagul 32 found that immature laboratory-bred Bithynia of the three taxa (2–4 mm long) were more susceptible to O. viverrini infection than field-collected snails (6–10 mm long). This finding would correspond with our data and imply that infection may increase mortality for small individuals, reducing infection rates in hosts of medium size.

Currently, it is believed that three species of Bithynia snails are distributed throughout Thailand and Lao PDR. 13,18,20 Different species seem to occupy different geographical areas (for example, B. funiculata is found in the north and B. s. goniomphalos is found in the northeast, whereas B. s. siamensis is distributed in the central region of the country). 18,20

The observed variation in prevalence of O. viverrini may also reflect the presence of sympatric species of snails. For instance, evidence from laboratory-bred snails and field-collected snails suggests that B. funiculata and B. s. siamensis are more susceptible to O. viverrini infection than B. s. goniomphalos. 32 The predominantly low-prevalence levels in some wetlands versus high-prevalence levels in others could be because of varying degrees of resistance and hence, potentially, the presence of different snail genetic groups/species. It is interesting to view this finding in terms of the hypothesized coevolution between snails and O. viverrini by Saijuntha and others. 33 The distributional range of Bithynia taxa as well as possible coevolution with O. viverrini requires additional investigations.

Previous investigations consistently showed lower infection prevalence in snails than the prevalence reported for four of the infected sites studied here. Of 13 infected localities, 11 localities were from rice fields, and the other 2 localities were a dam and a fish pond. Interestingly, among the six highest-prevalence localities, five localities came from snail samples from rice fields. Rice field aquaculture is becoming an increasingly important source of fish (including cyprinid) protein for the local populations in Southeast Asia generally. 34,35 Although our data do not provide direct evidence for why such high-prevalence levels are found in this habitat, a number of hypotheses can be presented. (1) It is possible that fish used to stock the rice fields are infected in the source nurseries, leading to high prevalence in humans and thus, snails. Evidence from Vietnam indicates that nursery stock was frequently infected with fish-borne zoonotic trematodes. 36 Our own preliminary data suggest that both hatchery and nursery stock in Lao PDR can be infected with O. viverrini, depending on the fish species (Sithithaworn P and others, unpublished data). (2) Snails with high prevalence were collected throughout the year, suggesting that climate is not a key factor. However, snails from the rainy season during the months of June to September are underrepresented. (3) Although human fecal material is not deliberately used for fertilizing rice fields, the drainage system present in rural villages leads directly to the contamination of fields with human and animal feces. 16,37

The surprisingly high prevalence that we detected has important implications for the transmission potential of O. viverrini and therefore, the possible increases in opisthorchiasis and CCA in the lower Mekong Region. Our results showing that there is a higher ratio of infected snails in Lao PDR compared with Thailand fit the epidemiological findings that humans in the Nam Ngum wetland have very high prevalence of O. viverrini, whereas control efforts have been underway in Thailand for several decades, possibly reducing the contamination of the environment with infected feces. 38 Recent records of high prevalence of O. viverrini in cats and dogs suggest the potential role of these animals in transmission in specific localities. 39,40 The high prevalence that we detected in B. s. goniomphalos indicates active transmission of the liver fluke in northeast Thailand and Lao PDR. The higher prevalence in some localities relative to previous records suggests a complex and unexplored relationship between humans as well as animal reservoir hosts and snail infection.

Whether the observed high geographic variability in prevalence is associated with specific genetic groups/species of Bithynia snails and/or O. viverrini parasites or other ecological factors needs additional study. Additionally, our results highlight the urgent need to continue to develop appropriate and practical methods of parasite control to reduce opisthorchiasis and CCA incidence.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the support of the Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Visiting International Professor Program.

Footnotes

Financial support: This work was supported by the Higher Education Research Promotion and National Research University Project of Thailand, Office of the Higher Education Commission. This research was also supported by the Thailand Research Fund through the Basic Research Grant and Royal Golden Jubilee PhD Program Grant PHD/0187/2548 (to N.K.) and German Federal Research Foundation Grant PE1611/3-1.

Authors’ addresses: Nadda Kiatsopit, Paiboon Sithithaworn, Thidarut Boonmars, Smarn Tesana, and Ross H. Andrews, Department of Parasitology, Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand and Liver Fluke and Cholangiocarcinoma Research Center (LFCRC), Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand, E-mails: nd_tg_na@yahoo.com, paib_sit@hotmail.com, boonmars@yahoo.com, smarn_te@kku.ac.th, and rhandrews@gmail.com. Weerachai Saijuntha, Walai Rukhavej Botanical Research Institute, Mahasarakham University, Mahasarakham, Thailand, E-mail: weerachai.s@msu.ac.th. Jiraporn Sithithaworn, Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Khon Kaen University, Khon Kaen, Thailand, E-mail: jirapo_n@gmail.com. Trevor N. Petney, Department of Ecology and Parasitology, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Karlsruhe, Germany, E-mail: petney@kit.edu.

References

- 1.Andrews RH, Sithithaworn P, Petney TN. Opisthorchis viverrini: an underestimated parasite in world health. Trends Parasitol. 2008;24:497–501. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2008.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.IARC Schistosomes, liver flukes and Helicobacter pylori. IARC. Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 1994;61:1–241. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saowakontha S, Pipitgool V, Pariyanonda S, Tesana S, Rojsathaporn K, Intarakhao C. Field trials in the control of Opisthorchis viverrini with an integrated programme in endemic areas of northeast Thailand. Parasitology. 1993;106:283–288. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000075107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sithithaworn P, Sukavat K, Vannachone B, Sophonphong K, Ben-Embarek P, Petney T, Andrews R. Epidemiology of food-borne trematodes and other parasite infections in a fishing community on the Nam Ngum reservoir, Lao PDR. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2006;37:1083–1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Upatham ES, Sukhapanth N. Field studies on the bionomics of Bithynia siamensis siamensis and the transmission of Opisthorchis viverrini in Bangna, Bangkok, Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1980;11:355–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brockelman WY, Upatham ES, Viyanant V, Ardsungnoen S, Chantanawat R. Field studies on the transmission of the human liver fluke, Opisthorchis viverrini, in northeast Thailand: population changes of the snail intermediate host. Int J Parasitol. 1986;16:545–552. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(86)90091-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adam R, Arnold H, Pipitgool V, Sithithaworn P, Hinz E, Storch V. Studies on lophocercous cercariae from Bithynia siamensis goniomphalos (Prosobranchia: Bithyniidae) Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1993;24:697–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lohachit C . Ecological studies of Bithynia siamensis goniomphalos a snail intermediate host of Opisthorchis viverrini in Khon Kaen Province, Northeast Thailand. Bangkok: Thailand: PhD thesis Mahidol University; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sri-Aroon P, Butraporn P, Limsomboon J, Kerdpuech Y, Kaewpoolsri M, Kiatsiri S. Freshwater mollusks of medical importance in Kalasin Province, northeast Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2005;36:653–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ngern-klun R, Sukontason KL, Tesana S, Sripakdee D, Irvine KN, Sukontason K. Field investigation of Bithynia funiculata, intermediate host of Opisthorchis viverrini in northern Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2006;37:662–672. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sri-Aroon P, Intapan PM, Lohachit C, Phongsasakulchoti P, Thanchomnang T, Lulitanond V, Hiscox A, Phompida S, Sananikhom P, Maleewong W, Brey PT. Molecular evidence of Opisthorchis viverrini in infected bithyniid snails in the Lao People's Democratic Republic by specific hybridization probe-based real-time fluorescence resonance energy transfer PCR method. Parasitol Res. 2010;108:973–978. doi: 10.1007/s00436-010-2140-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ditrich O, Scholz T, Giboda M. Occurrence of some medically important flukes (Trematoda: Opisthorchiidae and Heterophyidae) in Nam Ngum water reservoir, Laos. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1990;21:482–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giboda M, Ditrich O, Scholz T, Viengsay T, Bouaphanh S. Human Opisthorchis and Haplorchis infections in Laos. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1991;85:538–540. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(91)90248-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sithithaworn P, Haswell-Elkins M. Epidemiology of Opisthorchis viverrini. Acta Trop. 2003;88:187–194. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2003.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jongsuksuntigul P. In: Seminar in Parasitic Diseases in Northeast Thailand. Sithithaworn P, Srisawangwong T, Pipitgool V, Maleewong P, Kaewkes S, Tesana S, editors. Khon Kaen, Thailand: 2002. (Parasitic diseases in northeast Thailand.). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sayasone S, Odermatt P, Phoumindr N, Vongsaravane X, Sensombath V, Phetsouvanh R, Choulamany X, Strobel M. Epidemiology of Opisthorchis viverrini in a rural district of southern Lao PDR. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sayasone S, Vonghajack Y, Vanmany M, Rasphone O, Tesana S, Utzinger J, Akkhavong K, Odermatt P. Diversity of human intestinal helminthiasis in Lao PDR. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009;103:247–254. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brandt RAM. The non-marine aquatic Mollusca of Thailand. Arch Molluskenkunde. 1974;105:1–423. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Upatham ES, Sornmani S, Kitikoon V, Lohachit C, Bruch JB. Identification key for fresh-brackish water snails of Thailand. Malacol Rev. 1983;16:107–132. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chitramvong YP. The Bithyniidae (Gastropoda: Prosobranchia) of Thailand:comparative external morphology. Malacol Rev. 1992;25:21–38. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wongratanacheewin S, Pumidonming W, Sermswan RW, Maleewong W. Development of a PCR-based method for the detection of Opisthorchis viverrini in experimentally infected hamsters. Parasitology. 2001;122:175–180. doi: 10.1017/s0031182001007235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sripa B, Bethony JM, Sithithaworn P, Kaewkes S, Mairiang E, Loukas A, Mulvenna J, Laha T, Hotez PJ, Brindley PJ. Opisthorchiasis and Opisthorchis-associated cholangiocarcinoma in Thailand and Laos. Acta Trop. 2011;120((Suppl 1)):158–168. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shin HR, Oh JK, Masuyer E, Curado MP, Bouvard V, Fang YY, Wiangnon S, Sripa B, Hong ST. Epidemiology of cholangiocarcinoma: an update focusing on risk factors. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:579–585. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01458.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Soukhathammavong P, Odermatt P, Sayasone S, Vonghachack Y, Vounatsou P, Hatz C, Akkhavong K, Keiser J. Effecacy and safety of mefloquine, artesunate, mefloquine-artesunate, tribendimidine, and praziquantel in patients with Opisthorchis viverrini: a randomised, exploratory, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11:110–118. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70250-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Upatham ES, Viyanant V, Brockelman WY, Kurathong S, Lee P, Kraengraeng R. Rate of re-infection by Opisthorchis viverrini in an endemic northeast Thai community after chemotherapy. Int J Parasitol. 1988;18:643–649. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(88)90099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sornmani S, Schelp FP, Vivatanasesth P, Patihatakorn W, Impand P, Sitabutra P, Worasan P, Preuksaraj S. A pilot project for controlling O. viverrini infection in Nong Wai, Northeast Thailand, by applying praziquantel and other measures. Arzneimittelforschung. 1984;34:1231–1234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sithithaworn P, Andrews RH, Van De N, Wongsaroj T, Sinuon M, Odermatt P, Nawa Y, Liang S, Brindley PJ, Sripa B. The current status of opisthorchiasis and clonorchiasis in the Mekong Basin. Parasitol Int. 2012;61:10–16. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2011.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murrell KD, Fried B. Liver flukes. In: Sithithaworn P, Yongvanit P, Tesana S, Pairojkul C, editors; Food Borne Parasitic Zoonoses: Fish and Plant-Borne Parasites. New York: Springer: 2008. pp. 3–52. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petney T, Sithithaworn P, Andrews R, Kiatsopit N, Tesana S, Grundy-Warr C, Ziegler A. The ecology of the Bithynia first intermediate hosts of Opisthorchis viverrini. Parasitol Int. 2012;61:38–45. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laoprom N, Saijuntha W, Sithithaworn P, Wongkham S, Laha T, Ando K, Andrews RH, Petney TN. Biological variation within Opisthorchis viverrini sensu lato in Thailand and Lao PDR. J Parasitol. 2009;95:1307–1313. doi: 10.1645/GE-2116.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sripa B, Pairojkul C. Cholangiocarcinoma: lessons from Thailand. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2008;24:349–356. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3282fbf9b3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chanawong A, Waikagul J. Laboratory studies on host-parasite relationship of Bithynia snails and the liver fluke, Opisthorchis viverrini. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1991;22:235–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saijuntha W, Sithithaworn P, Wongkham S, Laha T, Pipitgool V, Tesana S, Chilton NB, Petney TN, Andrews RH. Evidence of a species complex within the food-borne trematode Opisthorchis viverrini and possible co-evolution with their first intermediate hosts. Int J Parasitol. 2007;37:695–703. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gregory R, Guttman H. In: Rural Aquaculture. Edwards P, Little DC, Demaine H, editors. Wallingford, United Kingdom: CAB International; 2002. pp. 1–13. (The rice field catch and rural food security). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Little DC, Surintaraseree P, Innes-Taylor N. Fish culture in rainfed rice fields of northeast Thailand. Aquaculture. 1996;140:295–321. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thien CP, Dalsgaard A, Nhan NT, Olsen A, Murrell KD. Prevalence of zoonotic trematode parasites in fish fry and juveniles in fish farms of the Mekong Delta, Vietnam. Aquaculture. 2009;295:1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Phan VT, Ersboll AK, Nguyen KV, Madsen H, Dalsgaard A. Farm-level risk factors for fish-borne zoonotic trematode infection in integrated small-scale fish farms in northern Vietnam. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e742. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jongsuksuntigul P, Imsomboon T. Opisthorchiasis control in Thailand. Acta Trop. 2003;88:229–232. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2003.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aunpromma S, Tangkawattana P, Papirom P, Kanjampa P, Tesana S, Sripa B, Tangkawattana S. High prevalence of Opisthorchis viverrini infection in reservoir hosts in four districts of Khon Kaen Province, an opisthorchiasis endemic area of Thailand. Parasitol Int. 2012;61:60–64. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Enes JE, Wages AJ, Malone JB, Tesana S. Prevalence of Opisthorchis viverrini infection in the canine and feline hosts in three villages, Khon Kaen Province, northeastern Thailand. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2010;41:36–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]