Abstract

While teen pregnancy rates appear to be declining in the USA overall, the rate of decline among young Latinas has been less than other ethnic groups. Among the myriad factors associated with elevated pregnancy rates, for Latina girls living in the inner city, exposure to gang and community violence may be a critical context for increased pregnancy risk. This study explores the relationship between gang involvement and reproductive health, and the pathways through which childhood, family, and relationship violence exposure may lead to unintended pregnancy. Interviews of 20 young adult Latinas with known gang involvement in Los Angeles County were audiotaped, transcribed, and coded for key themes related to violence exposure and reproductive health. Limited access to reproductive health care compounded by male partner sexual and pregnancy coercion, as well as physical and sexual violence, emerged in the interviews. Exposures to interparental domestic violence, childhood physical and sexual abuse, and gang violence were prominent and closely associated with unhealthy and abusive intimate relationships. Adverse childhood experiences and exposure to partner, family, and community violence impact the reproductive lives and choices of young Latina women in gangs. These findings may guide targeted pregnancy prevention efforts among urban gang-affiliated Latinas as well as encourage the integration of sexual violence prevention and reproductive health promotion within gang violence intervention programs.

Keywords: Unintended pregnancy, Gang violence, Intimate partner violence, Adverse childhood experiences, Family violence, Reproductive health, Latina women’s health

Teen births remain a critical public health challenge and are associated with poor health and social outcomes for young mothers and their children.1–4 Poverty, racism, “pushout” from the educational system, and limited social supports further accentuate these disparities in maternal and child health. While teen pregnancy rates appear to be declining in the USA overall, the rate of decline for young Latina women has been significantly less than other ethnic groups. Over half of Latina teens get pregnant at least once before age 20, twice the national average.5–8 Deeper understanding of the potential etiologies for this disparity is needed. While a number of studies have focused on individual-level acculturation and attitudes toward contraceptive use, few studies have examined the nexus of interpersonal violence and the impact of male partner behaviors on risk for pregnancy among young Latinas.

In urban settings where youth increasingly confront social disadvantage, marginalization, and limited opportunities for employment and education, a growing number of Latino youth, both males and females, are exposed to community violence including gang activity. Regardless of ethnicity, such community violence exposure is associated with childhood adversities including childhood abuse, parental substance abuse, and exposure to interparental violence, as well as experiences of adolescent dating violence.9–13 Both adverse childhood experiences and adolescent relationship violence are associated with increased risk for unintended pregnancy.14–18 In addition, a growing body of literature has documented how community violence exposure, specifically gang involvement, is associated with elevated sexual and pregnancy risk for gang-affiliated females.19–25 Therefore, among the myriad factors associated with elevated pregnancy rates for Latina girls living in the inner city, exposure to gang and community violence may be one critical context for increased pregnancy risk among this highly vulnerable population, which has generally been overlooked in teen pregnancy prevention efforts.

Studies examining the links between community violence exposure and poor reproductive health have tended to focus on individual behaviors that increase risk for unprotected intercourse, including multiple partnering, early-onset sexual activity, and condom nonuse. Only a few studies have examined male partner characteristics (including gang affiliation) which appear to increase women’s risk for sexually transmitted infections as well as pregnancy.19,26

Research on intimate partner violence points to the impact of such violence exposure on risk for unintended pregnancy.27–32 Specifically, male partner reproductive coercion (male partner attempts to impregnate their female partner) and physical and sexual violence in relationships contribute directly to risk for unintended pregnancy through birth control sabotage, condom manipulation or forced condom nonuse, forced sex, and related coercive behaviors.33–38 In one study which documented the association of male partner gang involvement on pregnancy, male partners’ pregnancy intention (as perceived by the female respondent) was strongly associated with elevated risk for pregnancy. However, the proximal mechanisms by which relationships with gang-involved males may contribute to increased pregnancy risk have not been explored.

This exploratory study utilized life history narrative interviews to examine (1) reproductive health histories and gang involvement (including male partner gang involvement) and (2) how women’s exposure to childhood, family, and partner violence in the context of gang involvement may contribute to increased risk for pregnancy. Elucidating the pathways connecting gang involvement and a young woman’s risk for pregnancy may guide the design of targeted and tailored interventions and prevention efforts for this highly vulnerable population.

Methods

Sample

The study employed a purposive sampling strategy, recruiting 20 young adult females with known histories of gang involvement through a large gang intervention program in Los Angeles, CA. All of the participants were receiving at least one type of service from the program (i.e., mental health, domestic violence advocacy, women’s support group, parenting classes). Program staff referred female clients aged 18–35 years with a history of gang involvement who were willing to share their stories about relationships and their health. The sample included both women who had ever been pregnant and those who had not. All of the women had experienced vaginal intercourse. Interviews were conducted over 2 months in 2010.

Procedures

Female research associates trained in interviewing women about intimate partner violence and sexual health conducted the interviews in a private space at a violence advocacy organization located away from the referring agency to afford the participants greater safety and privacy. Interviewers provided assurances of anonymity, answered questions regarding participation, and obtained informed consent immediately prior to each interview. The interviews were conducted in either Spanish or English, depending on the client’s preference. To further protect participants, a Certificate of Confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health was obtained, and the meaning and limitations of this certificate were reviewed with participants as part of the consent process. The study protocol was approved by the Human Subjects Research Committee of the University of California Davis School of Medicine.

An open-ended narrative interview strategy was utilized with a life history timeline to help construct chronologic narratives. The life history approach involves asking the respondent to place key events on a timeline from birth to present (such as birth of a child, completion or pushout from school). As the narrative unfolds during the interview, the interviewer probes for where on the timeline specific events from their story occurred which provide an opportunity to explore how one event led to another. Participants were asked to describe events related to their childhood, dating and sexual relationships, and experiences of violence or sexual assault within such relationships. Interviews included probes regarding peer groups, sexual decision making and negotiation, sexual health and pregnancy histories, attitudes and perceptions of intimate partner violence and sexual assault, family history, substance use, and experiences with the health care system. Interviews ranged from 60 to 90 minutes. After completion of the interview, the interviewers debriefed each participant, ensuring that the participant was intending to continue with using support services through the referring agency and were aware of additional violence and mental health-related resources available to them. Participants received a US $30 gift card as compensation for their time.

Data Analysis

Interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. The Spanish interviews were transcribed and translated into English simultaneously by a bilingual/bicultural member of the research team. Each transcript was coded using Atlas.ti software.39,40 Utilizing a content analysis approach,41 the first three interviews were reviewed by two investigators, and an initial list of codes that focused on key areas of interest (i.e., sexual decision making, violence exposure, contraceptive use, and pregnancy) was generated. All interviews were coded by two investigators, compared for agreement, and finalized. Additions of new codes or changes in code definitions were determined via consensus among the research team. Coding of interviews was ongoing while additional interviews were conducted. No new codes emerged after approximately six interviews were completed, suggesting content saturation was achieved. Final sample size was determined by content saturation as well as achieving a balanced sample of women’s ages and pregnancy histories.

Patterns and concepts were retrieved regarding pregnancy intentions, contraception, and pregnancy experiences within the context of females’ relationships characterized by gang involvement. The current analysis focuses on codes related to male and female pregnancy intentions, pregnancy and other sexual health outcomes, forced sex, sexual decision making, condom nonuse, contraceptive practices, and birth control manipulation.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Characteristics of the interview sample are summarized in Table 1. The women were of ages 18–34 years (mean age, 24 years; SD = 4.7), with most (all but five) 24 years and younger. Over half (55%) were born in the USA, mostly of Mexican origin. Almost all the women had not completed high school.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics (N = 20)

| Mean | Standard deviation | |

| Age, range 18–34 | 24 | 4.7 |

| Grade completed | 10.4 | 1.4 |

| N | Percentage | |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Mexican | 14 | 70 |

| Other Hispanic | 2 | 10 |

| Unknown | 4 | 20 |

| Nativity—born in USA | 11 | 55 |

| Gang involvement | ||

| Family gang member(s) | 10 | 50 |

| Gang member | 11 | 55 |

| Partner gang member | 13 | 65 |

| Exposure to violence | ||

| Interparental violence | 13 | 65 |

| Childhood physical abuse | 11 | 55 |

| Childhood sexual abuse | 12 | 60 |

| Community violence | 16 | 80 |

| Partner physical or sexual violence | 17 | 85 |

| Juvenile justice involvement | 9 | 45 |

| Prison | 4 | 20 |

| Pregnancy | ||

| Ever pregnant | 15 | 75 |

| Two or more pregnancies | 11 | 55 |

| Birth control sabotage | 4 | 20 |

| Pregnancy coercion | 11 | 55 |

Exposure to Violence

Participants reported having family members with gang affiliations, their own gang involvement, being exposed to gangs, and/or male partner gang affiliation. Only two of the participants reported no exposure to any childhood physical or sexual abuse or interparental violence. Most participants described more than one exposure to violence in childhood. In addition, almost all had experienced physical or sexual violence at the hands of at least one sexual partner. In one instance, the relationship violence was from a female partner.

Pregnancy Experiences

Pregnancy was common, with three quarters having ever been pregnant and half reporting two or more pregnancies. Half of the women reported experiencing coercion by their male partners to get pregnant; four reported explicit attempts to sabotage their birth control.

Limited Access to Knowledge About Reproductive Health

Women described contraceptive nonuse, inconsistent use, not thinking that they could get pregnant, or simply that the pregnancy “just happened.” Lack of access to accurate information about one’s reproductive health was noted by several participants. Women’s pregnancy intentions varied, but none reported planning a pregnancy.

I never knew anything about the pill, I didn’t know anything about condoms.…I guess I just let them do whatever they wanted to me. I think because I went through what I went through…I thought it was like…normal. (28 years old with history of childhood sexual abuse, family violence, sexual violence from partners, four children)

Male Partner Pregnancy Intentions and Sexual Coercion

Limited knowledge about pregnancy prevention was compounded by relationships in which the male partner actively desired pregnancy or was making her have sex she did not want to have.

It was never planned. My parents would go to work and I had to take care of my sisters. I was 17, when I met him. He would see the way I would treat my sisters. There’s this one day, he comes. He hugs me and tells me, “You’re going to be a very good mom.” But it never got to my mind that he was going to get me pregnant.…We got to know each other. That’s when we had relationships. We slept together. That’s when he got me pregnant.…It just happened. I got pregnant. (25 years old from Mexico, history of interparental violence, three children by different partners, gang-involved partner physically abusive)

Half of the women reported that their partners were actively trying to get them pregnant. Reasons given for male partner pregnancy intentions included women’s perceptions that male partners wanted to have a nuclear family or that they wanted a way to make the woman stay in the relationship.

He was the one always saying it: “I want to have a baby with you.” I said we need to wait because we’re young, and I didn’t even have a job. The last pregnancy, really, I didn’t want it. When they told me I was pregnant (the second time) I was happy, but at the same time I was like shit, we’re having a lot of problems. (23 years old native of Mexico, interparental violence and physical abuse by father, partner is gang member with pregnancy pressure, sexual violence in relationship)

But I remember one of my boyfriends wanted to get me pregnant. And I was like no, no no no no no. He did it on purpose like he didn’t wear a condom…he did it on purpose and I was just like, “F___.” What did I get myself into?.…To keep me. To make me stay. (22 years old, severe physical violence from mother, interparental violence, becomes gang member selling drugs)

I remember he always used to tell me that he wanted to have…he wanted to have a little kid with me and this and that. And I always used to tell him that I wasn’t prepared. And there were times where he sometimes wanted to go to the doctor with me but I didn’t want to go with him because I knew if he found out he was going to be running his mouth or he was going to try to tell me you better get off of this because you know I don’t like this and that. Like he always kept on telling me often like let’s have a little kid and this and that. (19 years old, history of interparental violence, childhood physical and sexual abuse, experiences of gang rape and abusive partner, hid birth control from this partner)

Male Partner Physical and Sexual Violence

In addition to male partner pregnancy intentions and related pregnancy pressure and birth control sabotage, the increased risk for unintended pregnancy evident among women who have male partners who are gang members may also stem from physical and sexual violence in the relationship, as well as women’s reticence to refuse sex for fear of a negative response. Sexual coercion was also often normalized in these relationships.

I was 16, at the beginning of the relationship. Everything happened right in the beginning but it still hurts me. That, it’s a rape, because if you don’t want to do it, you’re forcing your wife or your girlfriend or whatever she is, you’re forcing that person to do it. I felt like he forced me. After that I felt so useless, I felt so bad.…For me, that was a rape. He didn’t see it like that, he said because I was his wife, I was supposed to please him, what is he supposed to do, go somewhere else and get it? I don’t think that’s the right answer, whatever to tell your partner. (23 years old with two prior pregnancies, physically and sexually abusive relationship)

Like slapped me. But I would always be like oh well he doesn’t cheat on me, he doesn’t hit me all the time, I thought it was normal. (22 years old with history of birth control sabotage, abusive relationship)

I was what, 13 when I first had sex. And I got pregnant when I was 14. And I had my daughter when I was 15.…I didn’t wanna have a baby.…I just had it.…like I didn’t wanna have sex ya know? Ya know after what I went through I didn’t wanna have sex. But I don’t know why I did.…He would hit me if I didn’t have sex. Like at 17, I remember I didn’t want to have sex with him.…And then he forced me to like have sex, he would force me to have oral sex with him and I didn’t want to. And at one point I was going to stab him because I didn’t want to have sex with him…and he would force me.…When I didn’t want to have oral sex with him he’d slap me. (28 years old with history of childhood sexual abuse and drug use, she and her partners were gang-involved, has four children)

Exposure to Interparental Violence and Childhood Abuse

Another critical pathway that may increase the risk of unintended pregnancy among young women who have gang member partners is the proximal effect of being exposed to family violence, including interparental domestic violence and childhood physical and sexual abuse.

My parents fought all the time, yelling, and my dad would hit my mom. They would yell at each other at night, running after each other.…My dad would hit my mom, always when he was drunk. I was ten, and my siblings were 9, 8, and 6 when my mom left my dad. I think domestic violence affects kids a lot, because they grow with the mentality that I have to be just like them. It’s all a circle. It’s all the same. I think what I saw with my parents affecting my relationships a lot.…I know that I’m not ok, but I put up with it because he’s the father of my kids. He’s been abusive with me sometimes, like he knows that if he goes to the street with his friends, I’m not gonna leave. He knows that I’ll be in the home, and he’s abusive in that way. He’s hit me twice, one time he grabbed my hair.…He’s a gang-member. This affects me a lot, because my kids are growing up in it. Although he doesn’t bring anybody home with him, like friends, I know that they’re watching and they’re gonna do the same things. (24 year old with history of interparental violence, physical abuse from both parents, seven pregnancies she describes as unwanted, one abortion, six children)

I remember I was in elementary because I remember that, I think I was in like the fourth or fifth grade. I remember that he used to like put us in the room and then he would like…I don’t ever remember him actually raping me but I know he used to molest me because he used to like let us see him take a shower, he wanted us to be in there when he was taking a shower. He would like throw us in the bed, he would like take all our clothes off, and we would like lay with him in bed…I don’t know for what.…My mom was at work. He would like throw our clothes on top of the closet so we wouldn’t be able to get our clothes. It went on for I don’t really remember how long…cuz after that that’s when I started using drugs. (28 years old, molestation from stepfather, drug use as a child which leads to gang involvement, raped and beaten by subsequent boyfriends and other men on the street, has four children from different relationships)

In an attempt to flee the family violence, some women described running away to their boyfriend’s house or hanging out with gang members in their neighborhood for protection.

When I was 13, I met this guy, he knew what was going on in my house, he knew everything, he used to see it. I was with him because I was protected by him because he was from this other gang. He told me “Come lay with me and you’ll be alright.” But I was only 13 still, “I can’t live with you, are you crazy?” I thought to myself, I’m getting abused here, what’s gonna happen if I go over there? I didn’t go with him, I stayed at my house, but I was with him to feel protected by him.…During the 6 months, he took me to his house, I met his family, he wanted to have sex with me. And I was looking at him like, “You know what I’m going through at the house, and you want me to have sex with you?” He went ballistic, like, “I’m gonna kill you, you’re with me.” I’m like, “I don’t love you, I’m with you because I feel protected.” We’re falling asleep…in my sleep he must have done something to me, I didn’t have no pants on, I didn’t have my underwear on. I was like, “Oh my god, I’m going through the same shit here that I’m going through over there.” I said I’m done. I couldn’t take it, I was just messed up all the way around. Nobody knows it, but even my cousin was molesting me. He used to get me drunk and he was molesting me. The story didn’t end until it got really bad, like where I started saying ‘f-this, if anybody does anything to me, I’m gonna do something to them because I’m tired of this shit.’ I went through this for years. It had no stop to it. (30 years old; stepfather sexually and physically abusive, inter-parental violence; tried to protect her sister from sexual abuse; raped at 13 by boyfriend and cousin; describes getting into gangs for protection)

Gangs and Sexual Violence

Exposure to community violence is closely associated with family and partner violence, and, thus, increased risk for unintended pregnancy. Women described gang rape as an often expected part of gang involvement, reflecting traditional gender norms and the normalizing of sexual violence. Despite the promise of protection, gang involvement comes with constant threats of sexual violence.

Like men in the street…to me physically they tried to rape me.…My homeboys…not my homeboys from my neighborhood but my brother’s homeboys from his neighborhood tried to rape me. (28 years old, molestation from stepfather, drug use as a child, raped/beaten by subsequent boyfriends and other gang members, four children)

Some women reported responding with violence themselves to such threats of sexual violence, while others described trying to leave gangs and finding the supports necessary to heal from these multiple traumas.

Cuz most girls think that if you put yourself available sexually that they’re gonna like you. That’s how I would see it…I became someone like If you fuckin’ come near me or fuckin’ try to touch me. Because I was very defensive with what had happened to me I think. With my mom being very violent plus being molested when I was younger. So it was like that both combined into the, “If you fuckin’ touch me I’ll fuckin’ kick your ass…if you fuckin’ touch me I’ll get you fuckin’ killed.” That violence kicked in. That’s how I’ll protect myself. (22 years old, interparental violence, physical abuse from mother, sexual abuse and sexual assault, two pregnancies)

Discussion

The current study highlights the complex interactions among exposure to partner violence, family violence (childhood abuse as well as inter-parental violence), and community violence and risk for unintended pregnancy among a highly vulnerable population of young gang-affiliated Latinas in an urban setting. The pathways through which male partner gang involvement increases these women’s risk of unprotected intercourse and unintended pregnancy include direct factors such as forced sex and pregnancy coercion by the male partner, as well as fear of the partner and fear of gang member responses were she to resist his wishes, all of which create additional barriers for women seeking to prevent pregnancy. For this specific group of young adult Latinas with gang connections, in addition to the sexual violence associated with gang involvement, exposure to family violence, as well as sexual and physical violence from their partners, was common. Male partner sexual coercion, sexual entitlement, and pregnancy pressure were reported by multiple respondents. Further complicating the stories were young women joining gangs to seek protection from family violence, only to encounter additional sexual violence from gang members, as well as forced sex and pregnancy coercion from their gang-involved male partners. Substance abuse was common, described by respondents as a way to cope with the violence and their associated fear and anger, and this substance abuse subsequently increased vulnerability to sexual assault and exploitation. Women reported multiple ways in which they tried to survive, including attempting to find protection, leaving gangs, or seeking care from gang intervention programs.

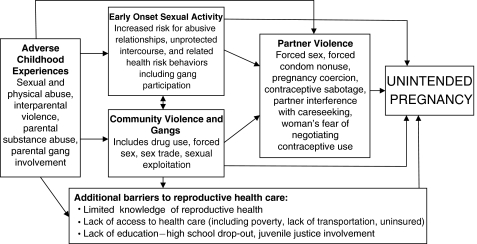

The literature on exposure to community violence has underscored the association with other childhood adversities and risk behaviors including substance abuse, suggesting both common pathways as well as the distinct impact of specific exposures to violence on subsequent poor adolescent outcomes.9,13 Studies have also pointed to the additive effects of adverse childhood experiences, as well as the clustering of such adversities in contributing to poor health in adulthood.42–46 The stories presented provide further evidence of this clustering of violence exposures. A particularly salient, and unexpected, finding emerging from these stories is the extent to which family and community violence are often proximal factors contributing to elevated pregnancy risk among this population of urban gang-affiliated Latina women. This is illustrated in Figure 1. That is, the severity of violence perpetrated by family members created a specific vulnerability of these young women who sought protection outside of their homes, increasing the risk of exposure to gang rape and sexually and physically violent relationships. Forced sex, pregnancy coercion by the partner, and fear of how he would react were the predominant reasons for women’s contraceptive and condom nonuse.

FIGURE 1.

Family, community, and partner violence and pregnancy risk.

These findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations, primarily the small, non-representative sample size. That content saturation was reached quickly in this interview study suggests some homogeneity of experiences among this group of young Latinas living in poor urban neighborhoods. As these were women who were already seeking to leave gang activity and were receiving services, it is possible that they experienced more severe abuse (thus more likely to be identified) or may have had additional factors making them more likely to seek help (e.g., trusting relationship with the community agency, ability to recognize abusive behaviors as wrong, wanting to be helped) as compared with young women in gangs who are still actively engaged in gang activities. In addition to size and sampling limitations, the study relies solely on self-report by young adult women and their perceptions of partners’ behaviors related to pregnancy. Reliance on self-report introduces significant potential for recall biases and respondents’ interpretations of male behaviors. Further study with male gang-involved young adults is needed to complement these findings. Additionally, while adolescent health research in the last decade has focused increasingly on young men’s perceptions of and experiences with pregnancy,47–50 development and evaluation of programs to address male pregnancy intentions and reduce sexual violence and pregnancy coercion are needed. In addition, the model presented in Figure 1 should be tested using larger population-based samples to better elucidate the role of pregnancy coercion, sexual violence, and exposure to family and gang violence in increasing young women’s risk for pregnancy. In particular, research on the impact of the structured urban environment and neighborhood contexts on young women’s sexual and reproductive decision making through influences on their access to care and social networks are needed to guide interventions at the neighborhood level.

These limitations notwithstanding, these stories offer some implications for practice and policy. These findings may guide targeted pregnancy prevention efforts among this highly vulnerable and hard-to-reach population of urban gang-affiliated Latinas as well as encourage the integration of sexual violence prevention and reproductive health promotion within gang violence intervention programs. The clustering of partner, family, and community violence with young women’s risk of pregnancy suggests that programs that explicitly address the connections between violence exposure and pregnancy prevention are needed. Universal pregnancy prevention education is unlikely to address the unique challenges facing youth in urban settings with high rates of gang violence.

Given the extent to which sexual abuse and sexual violence emerge in these women’s stories, any targeted interventions directed toward reducing gang violence should also explicitly integrate sexual violence prevention and intervention. Programs intended to support young women to leave gangs should address histories of sexual trauma and provide opportunities for trauma-informed care and recovery. Similarly, gang intervention policies may benefit from addressing the impact of childhood exposure to violence, including sexual abuse and the ongoing risks of sexual violence to better address the needs of youth being drawn into gang participation.

Acknowledgments

We wish to express our most humble appreciation to the young women who shared their stories with us. In addition, we are deeply indebted to the staff of Homeboy Industries and Peace Over Violence for their support of this project. Heather Anderson, Kiera Coulter, and Rebekah Lucien provided invaluable research assistance. This study was funded with support from The California Endowment via a grant to Futures Without Violence (formerly the Family Violence Prevention Fund).

References

- 1.Demirgoz M, Canbulat N. Adolescent pregnancy: review. Turkiye Klinikleri J Med Sci. 2008;28(6):947–952. [Google Scholar]

- 2.D’Onofrio BM, Goodnight JA, Hulle CA, et al. Maternal age at childbirth and offspring disruptive behaviors: testing the causal hypothesis. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009;50(8):1018–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02068.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lesser J, Escoto-Lloyd S. Health-related problems in a vulnerable population—pregnant teens and adolescent mothers. Nurs Clin North Am. 1999;34(2):289–299. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Padin MDR, Silva RDE, Mitsuhiro SS, Barros MM, Guinsburg R, Laranjeira R. Brief report: a socio-demographic profile of multiparous teenage mothers. J Adolesc. 2009;32(3):715–721. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The National Campaign. Del corazón de los jóvenes: what Latino teens are saying about love and relationships. 2008. http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/resources/pdf/pubs/Del_corazon.pdf. Accessed November 27, 2010.

- 6.The National Campaign. A Look At Latinos. 2005. http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/espanol/PDF/latino_overview.pdf. Accessed November 27, 2010.

- 7.Child Trends. Hispanic teen pregnancy and birth rates: looking behind the numbers. 2005. http://www.childtrends.org/Files/HispanicRB.pdf. Accessed November 27, 2010.

- 8.The National Campaign. Latina Birth Rates By State. 2005. http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/resources/pdf/FastFacts_LatinaBirthRateState_2005.pdf. Accessed November 27, 2010.

- 9.Margolin G, Vickerman KA, Oliver PH, Gordis EB. Violence exposure in multiple interpersonal domains: cumulative and differential effects. J Adolesc Health. 2010;47(2):198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aisenberg E, Herrenkohl T. Community violence in context—risk and resilience in children and families. J Interpers Violence. 2008;23(3):296–315. doi: 10.1177/0886260507312287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duke NN, Pettingell SL, McMorris BJ, Borowsky IW. Adolescent violence perpetration: associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):E778–E786. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fang XM, Corso PS. Child maltreatment, youth violence, and intimate partner violence—developmental relationships. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(4):281–290. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Finkelhor D, Turner H, Ormrod R, Hamby SL. Trends in childhood violence and abuse exposure evidence from 2 national surveys. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2010;164(3):238–242. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Campbell JC. Abuse during pregnancy: a quintessential threat to maternal and child health—so when do we start to act? Can Med Assoc J. 2001;164(11):1578–1579. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coker AL. Does physical intimate partner violence affect sexual health? A systematic review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2007;8(2):149–177. doi: 10.1177/1524838007301162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raj A, Silverman JG, Amaro H. The relationship between sexual abuse and sexual risk among high school students: findings from the 1997 Massachusetts Youth Risk Behavior Survey. Matern Child Health J. 2000;4(2):125–134. doi: 10.1023/A:1009526422148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Silverman JG, Raj A, Clements K. Dating violence and associated sexual risk and pregnancy among adolescent girls in the United States. Pediatrics. 2004;114(2):e220–e225. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.2.e220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hillis SD, Anda RF, Dube SR, Felitti VJ, Marchbanks PA, Marks JS. The association between adverse childhood experiences and adolescent pregnancy, long-term psychosocial consequences, and fetal death. Pediatrics. 2004;113(2):320–327. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.2.320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Auerswald CL, Muth SQ, Brown B, Padian N, Ellen J. Does partner selection contribute to sex differences in sexually transmitted infection rates among African American adolescents in San Francisco? Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33(8):480–484. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000204549.79603.d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harper GW, Robinson WL. Pathways to risk among inner-city African-American adolescent females: the influence of gang membership. Am J Community Psychol. 1999;27(3):383–404. doi: 10.1023/A:1022234027028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ohene SA, Ireland M, Blum RW. The clustering of risk behaviors among Caribbean youth. Matern Child Health J. 2005;9(1):91–100. doi: 10.1007/s10995-005-2452-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palmer CT, Tilley CF. Sexual Access to females as a motivation for joining gangs—an evolutionary approach. J Sex Res. 1995;32(3):213–217. doi: 10.1080/00224499509551792. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Talashek ML, Alba ML, Patel A. Untangling the health disparities of teen pregnancy. J Spec Pediatr Nurs. 2006;11(1):14–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2006.00040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voisin DR, Salazar LF, Crosby R, DiClemente RJ, Yarber WL, Staples-Horne M. The association between gang involvement and sexual behaviours among detained adolescent males. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80(6):440–442. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.010926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ, Crosby R, Harrington K, Davies SL, Hook EW. Gang involvement and the health of African American female adolescents. Pediatrics. 2002;110(5):e57. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.5.e57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minnis AM, Moore JG, Doherty IA, et al. Gang exposure and pregnancy incidence among female adolescents in San Francisco: evidence for the need to integrate reproductive health with violence prevention efforts. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167(9):1102–1109. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cripe SM, Sanchez SE, Perales MT, Lam N, Garcia P, Williams MA. Association of intimate partner physical and sexual violence with unintended pregnancy among pregnant women in Peru. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2008;100:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gao W, Paterson J, Carter S, Iusitini L. Intimate partner violence and unplanned pregnancy in the Pacific Islands Families Study. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2007;100:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller E, Decker MR, McCauley HL, et al. Pregnancy coercion, intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy. Contraception. 2010;81(4):316–322. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pallitto CC, O’Campo P. The relationship between intimate partner violence and unintended pregnancy: analysis of a national sample from Colombia. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2004;30(4):165–173. doi: 10.1363/3016504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Silverman J, Gupta J, Decker M, Kapur N, Raj A. Intimate partner violence and unwanted pregnancy, miscarriage, induced abortion, and stillbirth among a national sample of Bangladeshi women. BJOG. 2007;114(10):1246–1252. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stephenson R, Koenig MA, Acharya R, Roy TK. Domestic violence, contraceptive use, and unwanted pregnancy in rural India. Stud Fam Plann. 2008;39(3):177–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4465.2008.165.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raphael J. Teens having babies: the unexplored role of domestic violence. The Prevention Researcher. 2005;12:15-17. Available at: http://www.tpronline.org/article.cfm/Teens_Having_Babies__The_Unexplored_Role_of_Domestic_Violence. Accessed November 30, 2011.

- 34.Miller E, Decker M, Reed E, Raj A, Hathaway J, Silverman JG. Male pregnancy promoting behaviors and adolescent partner violence: findings from a qualitative study with adolescent females. Ambul Pediatr. 2007;7(5):360–366. doi: 10.1016/j.ambp.2007.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moore AM, Frohwirth L, Miller E. Male reproductive control of women who have experienced intimate partner violence in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2010;70(11):1737–1744. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silverman JG, Decker MR, McCauley HL, et al. Male perpetration of intimate partner violence and involvement in abortions and abortion-related conflict. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(8):1415–1417. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.173393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thiel de Bocanegra H, Rostovtseva DP, Khera S, Godhwani N. Birth control sabotage and forced sex: experiences reported by women in domestic violence shelters. Violence Against Women. 2010;16(5):601–612. doi: 10.1177/1077801210366965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wingood GM, DiClemente R. The effects of an abusive primary partner on the condom use and sexual negotiation practices of African-American women. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(6):1016–1018. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.6.1016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.The Knowledge Workbench. Atlas.ti. WIN 5.0 (Build 066). Berlin, Germany: scientific Software Development; 1997–2001.

- 40.Weitzman EA. Analyzing qualitative data with computer software. Health Serv Res. 1999;34(5):1241–1263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ryan G, Bernard H. Data management and analysis methods. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y, editors. Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2000. pp. 769–802. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dong M, Anda R, Felitti V, et al. The interrelatedness of multiple forms of childhood abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28(7):771–784. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dube S, Anda R, Felitti V, Edwards V, Williamson D. Exposure to abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction among adults who witnessed intimate partner violence as children: implications for health and social services. Violence Vict. 2002;17(1):3–17. doi: 10.1891/vivi.17.1.3.33635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, et al. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults—The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. Am J Prev Med. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Green JG, McLaughlin KA, Berglund PA, et al. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey replication I: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):113–123. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication II: associations with persistence of DSM-IV disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):124–132. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gohel M, Diamond JJ, Chambers CV. Attitudes toward sexual responsibility and parenting: an exploratory study of young urban males. Fam Plann Perspect. 1997;29(6):280–283. doi: 10.2307/2953418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marsiglio W. Adolescent males orientation toward paternity and contraception. Fam Plann Perspect. 1993;25(1):22–31. doi: 10.2307/2135989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosengard C, Phipps MG, Adler NE, Ellen JM. Psychosocial correlates of adolescent males’ pregnancy intention. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):E414–E419. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Marcell AV, Raine T, Eyre SL. Where does reproductive health fit into the lives of adolescent males? Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2003;35(4):180–186. doi: 10.1363/3518003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]