Abstract

We report the unusual complication of penile ulceration caused by Nicorandil, a nicotinamide ester used in the treatment of symptomatic angina pectoris.

Keywords: Nicorandil, Penile ulceration

INTRODUCTION

Penile ulceration presenting in elderly patients most commonly will have either a neoplastic or infective aetiology. Biopsy is required to exclude a malignancy with subsequent treatment dependent on the histopathological diagnosis.

CASE REPORT

Two patients aged 87 and 80 presented with a 4-6 week history of painful penile ulceration on the dorsum of the penis (Fig 1). There was no associated palpable groin lymphadenopathy in keeping with malignant or infective disease. The patients had been taking nicorandil for 3 and 5 years respectively at a dose between 10-20mg twice a day. hi addition to a history of cardiovascular disease both patients also were non insulin dependent diabetics and were previously smokers.

Fig 1.

Catheterised penis with a well demarcated ulcer with surrounding erythema and oedema resulting in complete erosion through the prepuce exposing the glans beneath.

Biopsy of both lesions demonstrated inflammation with no evidence of malignancy (fig 2). On the advice of the cardiologist the nicorandil was discontinued in both cases and on follow-up six weeks later the pain had subsided but the large ulcer persisted necessitating a circumcision in both cases.

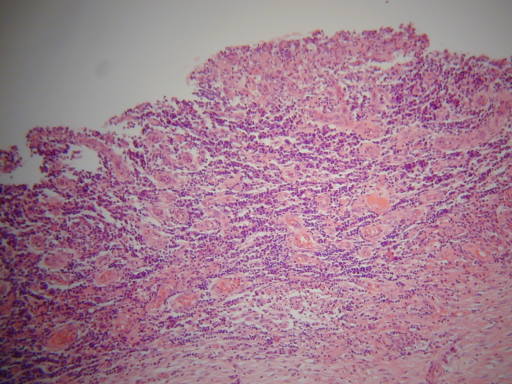

Fig 2.

Photomicrograph of ulcer edge after hemotoxylin-eosin staining demonstrating acute inflammatory cell infiltration.

DISCUSSION

Nicorandil is a nicotinamide ester1 which relaxes vascular smooth muscle of blood vessels. It has a duel mechanism of action, firstly by donation of a nitric oxide to activate guanylate cyclase and secondly through activation of ATP-sensitive potassium channels2. Arterial and venous vasodilation acts to reduce cardiac preload and afterload. It is a novel drug in its class which can be used alone or in combination with other anti-angina treatments3.

In addition to well described side effects such as headache, facial flushing, dizziness and hypotension1 recently cases of skin ulceration have been described. Ulcers of the oral mucosa1, anal4, perianal5, parastomal cutaneous sites6 have all been documented in the literature. Only one case of penile ulceration has been reported to date 7. Classically the ulcers tend to be deep and well demarcated with histology revealing acute inflammation.

A number of theories for the pathogenesis of nicorandil-induced ulceration have been hypothesised including a direct toxic effect of nicorandil or one of its metabolites on the tissues1. A second theory is the “vascular steal hypothesis”7. Nicorandil due to its action on the local circulation causes alterations in arterial and venous flow, and the hypothesis is that this could have a profound effect on end arteries, such as the penis. Other risk factors for vascular disease such as diabetes and smoking as in these two patients could obviously contribute to any ischaemic phenomenon.

The differential diagnosis for patients presenting with penile ulceration should include malignancy, and infections such as syphilis. Serological testing was not performed in this group of two patients, for two reasons. Firstly the clinical risk was determined to be low based on the clinical history, and secondly the lesion we describe was painful in contrast to the painless chancre of primary syphilis. It would be important however in the sexually active population to determine the VDRL (Venereal Disease Research Laboratory) status of patients presenting with similar lesions. Nicorandil which has been introduced into clinical use within the last decade and it should be recognised in the differential diagnosis of these patients particularly in the setting of chronic administration. Many of the effects seem to be reversible on stopping the medication however if the ulcer is particularly large the defect may not heal requiring surgical intervention.

The authors have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Healy CM, Smyth Y, Flint SR. Persistent nicorandil induced oral ulceration. Case Report. Heart. 2004;90(7):e38. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2003.031831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Markham A, Plosker GL, Goa K. Nicorandil. An updated review of its use in ischaemic heart disease with emphasis on its cardioprotective effects. Drugs. 2000;60(4):955–74. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200060040-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.British National Formulary, editor. 56th edition. London: British Medical Association, & The Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Toquero L, Briggs CD, Bassuini MM, Rochester JR. Anal ulceration associated with Nicorandil: case series and review of the literature. Colerectal Dis. 2006;8(8):717–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2006.00972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker RP, Al-Kubati W, Atuf M, Philips RK. Nicorandil-induced severe perianal ulceration. Tech Coloproctol. 2007;11(4):343–45. doi: 10.1007/s10151-007-0378-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams C, Tamuno P, Smith A, Walker S, Lyon C. Perianal ulceration and other cutaneous ulcerations complicating Nicorandil therapy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56(5 Suppl):S116–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Birnie A, Dearing N, Littlewood S, Carlin E. Nicorandil-induced ulceration of the penis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2008;33(2):215–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]