Understanding the assumptions and uncertainties in modeling radiation exposure risk will help clinicians communicate imaging-related risk to patients, understand model outcome projections, and use model results to guide appropriate diagnostic imaging use.

Abstract

Purpose:

To evaluate the effect of incorporating radiation risk into microsimulation (first-order Monte Carlo) models for breast and lung cancer screening to illustrate effects of including radiation risk on patient outcome projections.

Materials and Methods:

All data used in this study were derived from publicly available or deidentified human subject data. Institutional review board approval was not required. The challenges of incorporating radiation risk into simulation models are illustrated with two cancer screening models (Breast Cancer Model and Lung Cancer Policy Model) adapted to include radiation exposure effects from mammography and chest computed tomography (CT), respectively. The primary outcome projected by the breast model was life expectancy (LE) for BRCA1 mutation carriers. Digital mammographic screening beginning at ages 25, 30, 35, and 40 years was evaluated in the context of screenings with false-positive results and radiation exposure effects. The primary outcome of the lung model was lung cancer–specific mortality reduction due to annual screening, comparing two diagnostic CT protocols for lung nodule evaluation. The Metropolis-Hastings algorithm was used to estimate the mean values of the results with 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs).

Results:

Without radiation exposure effects, the breast model indicated that annual digital mammography starting at age 25 years maximized LE (72.03 years; 95% UI: 72.01 years, 72.05 years) and had the highest number of screenings with false-positive results (2.0 per woman). When radiation effects were included, annual digital mammography beginning at age 30 years maximized LE (71.90 years; 95% UI: 71.87 years, 71.94 years) with a lower number of screenings with false-positive results (1.4 per woman). For annual chest CT screening of 50-year-old females with no follow-up for nodules smaller than 4 mm in diameter, the lung model predicted lung cancer–specific mortality reduction of 21.50% (95% UI: 20.90%, 22.10%) without radiation risk and 17.75% (95% UI: 16.97%, 18.41%) with radiation risk.

Conclusion:

Because including radiation exposure risk can influence long-term projections from simulation models, it is important to include these risks when conducting modeling-based assessments of diagnostic imaging.

© RSNA, 2012

Supplemental material: http://radiology.rsna.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1148/radiol.11110352/-/DC1

Introduction

The U.S. National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements reported that radiation exposure from radiologic and nuclear medicine procedures in the general population increased by approximately 600% from 1980 to 2006, predominantly caused by imaging procedures (1,2). Computed tomographic (CT) scans comprised 17% of the total radiologic and nuclear medicine procedures in 2006, yet accounted for 49% of the collective radiation dose (1,3,4). Studies of cohorts exposed to high levels of ionizing radiation suggest that potential long-term effects of diagnostic imaging at lower levels of ionizing radiation may include cancer induction and increased cancer-related mortality (5–7). Thus, estimating the risks and benefits of diagnostic imaging is increasingly important. Simulation models that include radiation risks are one approach to quantifying the long-term benefits and risks associated with medical imaging.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effect of incorporating radiation risk into microsimulation (first-order Monte Carlo) models for breast and lung cancer screening to illustrate the effects of including radiation risk on patient outcome projections.

Materials and Methods

All data used in this study were derived from publicly available or deidentified human subject data. Institutional review board approval was not required. One author (G.S.G.) has served as a consultant for GE Healthcare (Milwaukee, Wis) on topics unrelated to this project. There is no direct conflict with the content of this article.

Estimating Radiation-induced Cancer Risk

As described in the Biologic Effects of Ionizing Radiation (BEIR) VII report (8), the radiation-induced cancer risk in a population exposed to a known radiation dose over a specified anatomic region can be estimated. For each organ exposed, the BEIR VII model partitions radiation risks in terms of excess absolute risk (EAR) and excess relative risk (ERR) functions. The EAR is the age-specific difference difference in cancer incidence rates between a population with radiation exposure and one with exposure only to background radiation. The ERR represents the ratio of the age-specific cancer rate in a population with radiation exposure to that of a population with only background radiation exposure. To calculate the excess risk caused by cumulative exposure (ie, as a result of multiple imaging studies occurring over time), the excess risk from individual exposures are summed.

In the BEIR VII model, EAR and ERR models are defined by a set of specific factors:

|

Three factors must be specified when using these models to estimate radiation-related cancer risks, including (a) absorbed dose, d; (b) the age at initial radiation exposure, e, incorporated within the term exp(γ · e*), where e* = 0 if e is 30 years or younger and e* = (e − 30)/10 if e is older than 30 years; and (c) age, A, which represents the attained age of the individual or population under consideration, incorporated within the term (A/A0)η, where A0 refers to the age at which the EAR and ERR models are standardized, typically 60 years. Three factors (β, γ, and η) are prespecified in the BEIR VII report for each organ exposed; b is the risk per gray (for ERR) or the risk per gray–10000 persons (for EAR) at age at exposure = 30 and attained age = 60; g is equal to the risk decay constant for every decay since radiation exposure; and h is the exponent of the ratio between attained age and the reference age at 60 years. Equation (1) can be reduced to a function of only age at exposure (e) or attained age (A) by setting g or h to zero, respectively. The BEIR VII committee recommends that the radiation-induced cancer risk is the geometric mean of EAR and ERR estimates (Appendix E1 [online]).

Incorporating Radiation Exposure Risk into Medical Simulation Models

An important challenge of incorporating radiation risk models into simulation models is the selection of the proper risk models for the specific risk profiles of the populations being examined. Women with BRCA gene mutations have a significantly increased risk of developing breast cancer (9–12). Because of their increased breast cancer risk, the use of screening mammography prior to age 40 years has been recommended. While the radiation exposure associated with screening mammography, film or digital, is very low, some studies have urged caution when recommending screening mammography in BRCA mutation carriers, particularly at ages younger than 35 years (13,14). In the absence of a definitive randomized controlled trial to establish the effectiveness of multimodality breast cancer screening, the Breast Cancer Model was developed to project long-term health outcomes of breast cancer screening strategies by using mammography (film or digital), alone or in combination with MR imaging, in BRCA1 mutation carriers (15,16).

It is likely that the BEIR VII EAR model for the general female population would underestimate radiation-induced breast cancer incidence in women at increased breast cancer risk, such as BRCA mutation carriers. Therefore, we chose to incorporate the ERR model, where the excess risk of radiation exposure is proportional to the population’s underlying breast cancer risk, into the Breast Cancer Model. Because Preston et al (17), in their analysis of breast cancer incidence, did not identify a single common model that adequately described data from all eight cohorts studied, we chose to include both models for ERR for age at exposure (ERRAE) and ERR for attained age (ERRAA). To calculate the ERR for annual digital mammographic screening, we used Equations (2) and (3) (17), as follows:

and

|

In the scenarios presented, the Breast Cancer Model was used to compare annual digital mammographic screening beginning at age 25, 30, 35, or 40 years with a reference strategy of clinical surveillance without imaging. For digital mammography, the average mean glandular dose to the breast tissue per woman is 4.2 mGy (18). The primary outcome projected by the Breast Cancer Model was life expectancy (LE), both without and with radiation exposure risk. The average number of false-positive screenings per woman was also projected for each screening strategy. Including radiation risk in the model had no effect on the diagnostic accuracy of digital mammography.

For the consideration of lung cancer screening with chest CT, we developed the Lung Cancer Policy Model to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of CT screening for lung cancer (19–21). The Lung Cancer Policy Model simulates individuals with the development and progression of five lung cancer cell types, which vary by prognosis and relationship to smoking. In the Lung Cancer Policy Model, the smoking behaviors of male and female patients were simulated by using U.S. historical data (22). Each individual may develop up to three cancers from any of five lung cancer cell types (adenocarcinoma, large cell, squamous cell, small cell, or other cancers). Natural history parameters related to unobservable events (ie, the initiation of the first cancer cell) were estimated through model calibration by using tumor registry data and data from published cohort studies (23). The model has been validated, and a detailed description is available online (https://cisnet.flexkb.net/mp/pub/cisnet_lung_mghita_profile.pdf).

Lung cancer screening with CT involves serial low-dose scans over time. Because of the high probability of positive examination findings during the initial screening, 23%–51% of screened participants can undergo follow-up diagnostic CT examinations performed at higher radiation doses (24–26). In the Lung Cancer Policy Model, patients with indeterminate pulmonary nodules smaller than 8 mm in diameter are followed up with thin-section CT for up to 2 years; the absence of growth is considered evidence of benign disease. We simulated cohorts of 1 million U.S. white male and female patients born in 1930, 1940, and 1950, who either did or did not undergo annual CT screening, and compared the subsequent lung cancer–specific mortality rates among them. In the no-screening scenario, lung cancers and benign pulmonary nodules could be detected at incidental imaging or following the development of clinical symptoms. In the screening scenario, we simulated annual CT screening for individuals with at least 20 pack-years (packs of cigarettes smoked per day multiplied by the number of years that the smoker has been smoking) of smoking exposure starting in the year 1990 until age 74 years.

By assuming that BEIR VII ERR and EAR are the same for all histologic types, the increase in lung cancer rate is determined with the geometric mean of the equations (1 + ERR) · Iback and Iback + EAR, with weighting factors of 0.3 for ERR and 0.7 for EAR and where Iback is background cancer incidence rate. In lung cancer screening, female participants are also subjected to the radiation risk of breast cancer from CT scans. Because the breast model in the BEIR VII report was based on the study by Preston et al (17), we used the original radiation risk breast model that their study specified to calculate the number of radiation-induced breast cancers attributable to lung cancer screening.

To address the parameter uncertainty related to the radiation risk, the Metropolis-Hastings algorithm (27) was used to estimate 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs) of our results from both breast and lung models (Appendix E1 [online]).

Results

Breast Cancer Screening

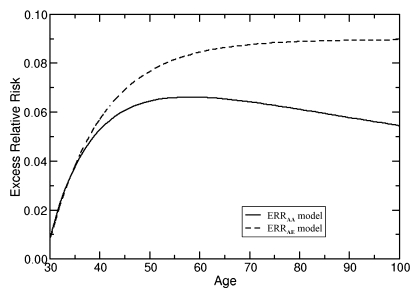

The age-specific ERRs from annual digital mammography, computed by using both ERRAA (Eq [2]) and ERRAE (Eq [3]) models, and assuming on average a 10-year latent period between radiation exposure and clinical detection of cancer, are shown in Figure 1. The cumulative ERR was calculated with each successive exposure. The key difference between the two ERR models is their effects over time. While the ERRAE model shows a plateau in ERR as age increases, the ERRAA model shows an initial increase, reaches a maximum, and then declines.

Figure 1:

ERR of radiation exposures from annual digital mammography. ERR estimates are based on absorbed dose to the breast of 4.15 mGy for annual digital screening mammography starting at age 25 years. The radiation risks at specific ages were calculated by summing the cumulative absorbed doses to the breast from annual screening by using (Equations 2) and (3) for ERRAA and ERRAE, respectively.

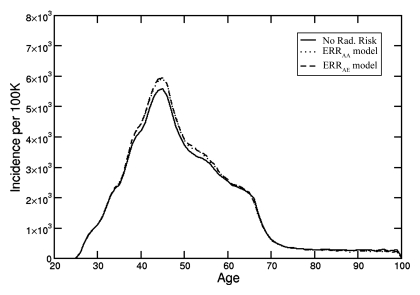

Despite the difference between ERRAE and ERRAA curves (Fig 1), when both ERR models are integrated into the Breast Cancer Model, similar breast cancer incidence curves are produced (Fig 2). The relatively modest increase in age-specific breast cancer incidence described by the Breast Cancer Model can be attributed to the very high baseline breast cancer incidence in women with BRCA1 mutations, as well as to the effects of competing mortality with increasing age, which attenuate the long-term radiation exposure effects of the ERR models. Since both ERRAE and ERRAA models yielded similar results and conclusions, results with the use of only the ERRAE model are presented.

Figure 2:

Age-specific breast cancer incidence from annual digital screening mammography beginning at age 25 years without and with radiation exposure risk. The ERRAA and ERRAE models produced results that were almost indistinguishable.

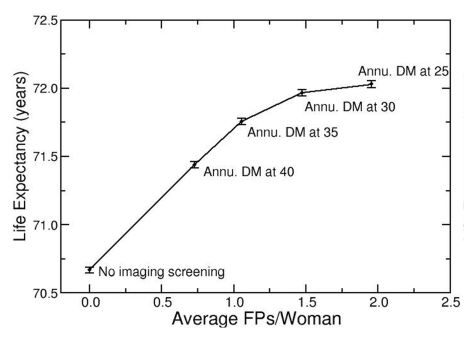

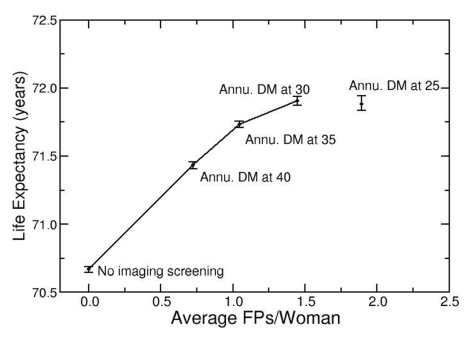

In the analysis, strategies were ranked in order of increasing LE and average number of screenings with false-positive results per woman. For a given number of screenings with false-positive results per woman, the screening strategy with the highest LE was considered the most efficient. Strategies that provided increased additional LE as the number of screenings with false-positive results per woman increased were considered to be “efficient” and connected on an “efficiency frontier.” Strategies with higher false-positive results and lower LE than those on the frontier were considered inefficient (or dominated) and not shown on the “efficiency frontier.”

When LE was projected in the context of false-positive screening results without radiation effects (Fig 3a), annual digital mammographic screening beginning at age 25 years was the strategy on the efficiency frontier with the greatest LE (72.03 years; 95% UI: 72.01 years, 72.05 years) and also the highest false-positive results (2.0 screenings with false-positive results per woman). When radiation exposure effects were added (Fig 3b), the LE benefit from earlier screening was offset by radiation exposure effects. Annual digital mammography beginning at age 25 years had no significant difference in LE (71.88 years; 95% UI: 71.83 years, 71.93 years) and had higher false-positive results (1.9 screenings with false-positive results per woman), compared with annual digital mammography beginning at age 30 years (LE = 71.90 years; 95% UI: 71.87 years, 71.94 years; false-positive results = 1.4 screenings with false-positive results per woman), and was no longer considered an efficient screening strategy.

Figure 3a:

Radiation exposure risk influences optimal age to begin mammographic screening. (a) Efficiency frontier plot shows the benefit of annual screening (Annu.) with digital mammography (DM) starting at different ages in the context of false-positive screening test results (FPs), without added radiation exposure risk. (b) Plot shows comparison of same strategies as in a, with radiation exposure risk included. Screening beginning at age 25 years provides decreased LE and greater false-positive results than does screening beginning at age 30 years and is no longer considered an “efficient” screening strategy.

Figure 3b:

Radiation exposure risk influences optimal age to begin mammographic screening. (a) Efficiency frontier plot shows the benefit of annual screening (Annu.) with digital mammography (DM) starting at different ages in the context of false-positive screening test results (FPs), without added radiation exposure risk. (b) Plot shows comparison of same strategies as in a, with radiation exposure risk included. Screening beginning at age 25 years provides decreased LE and greater false-positive results than does screening beginning at age 30 years and is no longer considered an “efficient” screening strategy.

Lung Cancer Screening

We used parameters from the BEIR VII report for the ERR and EAR models and applied a 10-year latent period between radiation exposure and cancer detection, as previously described by Berrington de González et al (28). To account for the 10-year lag between exposure and lung cancer incidence, we used a 7-year lag in conjunction with the predicted average 3-year sojourn time (ie, duration of preclinical screen-detectable phase at cancer onset) of the Lung Cancer Policy Model.

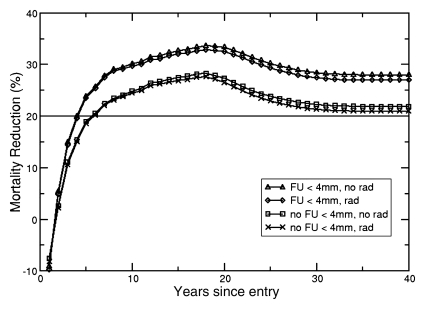

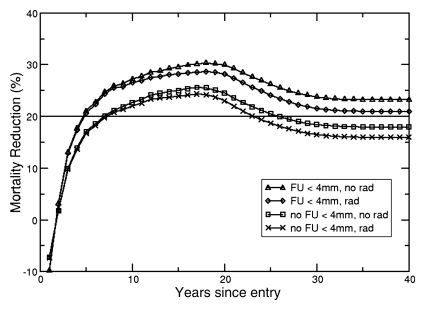

The Lung Cancer Policy Model simulates the effectiveness of screening for lung cancer with helical CT while taking into account radiation exposure effects. The lower two curves in Figure 4 show cumulative mortality reduction in 60-year-old male and female patients as a function of year since entering a screening trial in which follow-up imaging was only recommended for nodules 4 mm or larger. With screening, the predicted lifetime lung cancer–specific mortality reduction was 21.73% (95% UI: 21.17%, 22.29%) for male patients and 17.85% (95% UI: 17.34%, 18.39%) for female patients. When radiation exposure risk was included, the benefit of screening was slightly reduced to 20.72% (95% UI: 20.22%, 21.27%) for male patients and 15.88% (95% UI: 15.33%, 16.39%) for female patients. The two upper curves in Figure 4 demonstrate the effects of using CT to also follow up patients with nodules smaller than 4 mm, a more aggressive management strategy with higher population radiation exposures. The lifetime lung cancer mortality reduction was 26.74% (95% UI: 26.20%, 27.27%) for male patients and 21.26% (95% UI: 20.67%, 21.87%) for female patients with radiation risk, and 27.89% (95% UI: 27.48%, 28.37%) for male patients and 23.51% (95% UI: 23.02%, 24.05%) for female patients without radiation risk. The lung cancer–specific mortality reduction for all six cohorts, summarized in Table 1, is comparable to those reported from the National Lung Screening Trial (30). When screening starts at age 50 years for both sexes, there is a significant difference between lung cancer–specific mortality reduction with and without radiation risk effects. Because of stronger radiosensitivity to radiation exposure among female patients, differences in mortality reduction were observed up to the screening age of 70 years when patients with nodules smaller than 4 mm were followed up. For male patients, this difference was observed only up to a screening age of 60 years.

Figure 4a:

(a, b) Mortality reduction from screening as a function of time since entry into a hypothetical annual screening program (to age 74 years) for cohorts of (a) 60-year-old male patients and (b) 60-year-old female patients. Solid horizontal line = 20% mortality reduction (for reference). The upper two curves represent a screening strategy where follow-up (FU) in patients with suspicious lung nodules less than 4 mm in diameter is performed with CT examinations (FU < 4 mm), with incorporation of radiation risk (rad) and without the incorporation of radiation risk (no rad). The bottom two curves represent the results from a screening strategy with no follow up of lung nodules less than 4 mm in diameter (no FU < 4 mm).

Table 1.

Lung Cancer Mortality Reduction for Six Cohorts Screened Annually with Low-Dose CT until Age 74 Years

Note.—Numbers in parentheses are 95% UIs. The absorbed dose to the lung with low-dose CT is 3.8 mGy for men and 3.9 mGy for women (28). The absorbed dose to the lung with follow-up CT is 15.0 mGy for men and 15.4 mGy for women. The absorbed doses to the breast are 4.0 mGy and 15.7 mGy for screening and follow-up, respectively (28,29). FU = follow-up, FU < 4 mm = FU procedures include nodules less than 4 mm in size, no FU < 4 mm = no FU procedures included nodules less than 4 mm in size.

Scenarios show significant difference between lung cancer–specific mortality with and without accounting for radiation risk.

Figure 4b:

(a, b) Mortality reduction from screening as a function of time since entry into a hypothetical annual screening program (to age 74 years) for cohorts of (a) 60-year-old male patients and (b) 60-year-old female patients. Solid horizontal line = 20% mortality reduction (for reference). The upper two curves represent a screening strategy where follow-up (FU) in patients with suspicious lung nodules less than 4 mm in diameter is performed with CT examinations (FU < 4 mm), with incorporation of radiation risk (rad) and without the incorporation of radiation risk (no rad). The bottom two curves represent the results from a screening strategy with no follow up of lung nodules less than 4 mm in diameter (no FU < 4 mm).

Because CT screening exposes organs other than the lungs (such as the breast) to radiation, women who undergo screening with CT may be at a higher risk for developing breast cancer. We have used the BEIR VII model to calculate the number of radiation-induced breast cancers caused by lung cancer screening. Our results show that the mean numbers of radiation-induced breast cancers range from two to 17 cases per 10 000 women, depending on age at first screening and size threshold level for follow-up imaging (Table 2).

Table 2.

Number of Radiation-induced Breast Cancers per 10 000 Women from Annual Lung Cancer Screening

Note.—Numbers in parentheses are 95% UIs. The radiation exposure includes screening and follow-up chest CTs. The absorbed doses to the breast are 4.0 mGy and 15.8 mGy for screening and follow-up CT scans, respectively (28,29). FU = follow-up, FU < 4 mm = FU procedures included nodules less than 4 mm in size, no FU < 4 mm = no FU procedures included nodules less than 4 mm in size.

Discussion

We analyzed the effect of the use of radiation risk models and their integration in simulation models of breast and lung cancer screening. Underlying assumptions and sources of uncertainty have been presented. More important, when including radiation risk in medical decision models, absorbed dose, not effective dose—which is averaged over both sexes and all ages, should be used in conjunction with the patient’s sex, age at exposure, and attained age. Currently, radiation risk is not routinely considered in many effectiveness and cost-effectiveness analyses of imaging technologies. However, the results of our studies suggest that microsimulation models should incorporate radiation risk, as the analysis is more complete, and the conclusions of the analysis may change when radiation risk is taken into account.

As illustrated by the Breast Cancer Model, the effects of radiation exposure are most pronounced at younger ages. For BRCA1 mutation carriers, the mammographic screening strategy that maximized LE in the context of false-positive results and radiation exposure risk was annual digital mammography beginning at age 30 years rather than at age 25 years. Because including radiation risk can influence long-term outcome projections, it is important to consider these risks when conducting modeling-based assessments of diagnostic imaging.

As individuals age, competing mortality effects will outweigh new radiation exposure effects. For current and former smokers subjected to radiation exposure from CT screening and follow-up procedures, the predicted benefits of screening outweighed the risk of radiation-induced cancer. If lung cancer screening is adopted, overestimation of the radiation risks from CT (if it led to underuse of imaging) could have an adverse effect on patient outcomes. Caution must be exercised when communicating radiation risks to patients, to ensure that both the benefits of imaging procedures and potential harms are discussed.

The results of these and other studies (8,17) indicate that age at exposure is a key parameter in determining the lifetime risk of developing a radiation-induced cancer. Dose reduction is an active research area in diagnostic imaging (31). Given the acute radiosensitivity of developing organs (8), and the fact that infants and children have more time after imaging than adults to develop radiation-induced cancers (32), additional research is needed to optimize imaging protocols and decrease radiation exposures from diagnostic imaging in infants and children (8).

Besides state-transition models, statistical models with differing structures and assumptions can also be used to assess the potential benefits and risks of screening. Berrington de González et al assessed radiation risk from mammographic screening in BRCA mutation carriers (13). Their analysis focused on calculating the cumulative lifetime risk of radiation-induced breast cancer mortality, and they compared that with the cumulative breast cancer mortality risk without screening. The ratio of additional mortality risk with screening to that without screening provided the mortality reduction necessary for the benefit of mammographic screening to outweigh its radiation exposure risks. The excess mortality risk from mammography in this analysis was calculated by using the ERRAA model, multiplied by the age-specific population incidence of breast cancer, and summed from 10 years after the age of first screening to age 84 years. This statistical model did not include more detailed prognostic factors used in the Breast Cancer Model, such as stage distribution of diagnosed cancers, age at diagnosis, receptor status, or treatment effects, nor were LE or false-positive test results among the projected outcomes.

Despite differences between the models, the conclusions were similar. Berrington de González et al (13) reported that, for BRCA mutation carriers, mammographic screening at ages 25–29 years was less beneficial than beginning screening at later ages, a finding consistent with our results. Regarding the optimal age to begin screening, the two models differ slightly. Berrington de González et al concluded that the net benefit of screening would be zero or small at age 30–34 years, but that there should be some net benefit at age 35 years or older. The results with the Breast Cancer Model support mammographic screening beginning at age 30 years, provided the projected number of false-positive test results was acceptable for the women being screened.

Berrington de González et al (28) also examined the trade-off between three annual lung CT screenings before age 55 years and radiation risk. Their results showed that significant mortality reduction is required to offset the radiation risk for screening before age 50. Their estimate of radiation-induced breast cancer from lung screening was in the range of three to six cases per 10 000 women screened, which was similar to our results. However, direct comparison between two studies is not possible, as Berrington de González et al calculated the radiation risk for lung cancer screening with three CT screening examinations, while our study examined annual screening until age 74 years. Their model also did not account for the radiation exposure from follow-up CT scans.

In addition to the BEIR VII lung cancer model, a recent study has applied a pure ERR method to examine the effect of the interaction between smoking and radiation exposure (33). However, this analysis examined the lung cancer incidence among the Japanese atomic bomb survivors. Direct application of the ERR model from this study to the U.S. population may be inappropriate because of the risk factor differences between the two populations.

A potential limitation in our study was that we used subgroups of the general population, white patients for the lung cancer model and BRCA1 mutation carriers for breast cancer. For the lung cancer analysis, we simulated only white patients because of insufficient smoking history data in patients of other races. For the breast cancer analysis, we elected to focus on a high-risk population, for whom more intensive screening is generally recommended, because the potential effects of radiation risk on patient outcome are greater. Caution must be applied when extrapolating our results to the general population.

Estimating the benefits and risks of diagnostic imaging is an increasingly important issue. Simulation models that include radiation risk models are one approach to quantifying both the long-term benefits and risks of diagnostic pathways involving imaging. Understanding the assumptions and uncertainties in modeling radiation exposure risk will help clinicians communicate imaging-related risk to patients, understand model outcome projections of simulation models, and use model results to guide appropriate diagnostic imaging use.

Advance in Knowledge.

We identified clinically plausible scenarios in which accounting for radiation exposure effects can substantially alter the results of a simulation model–based analysis of alternative screening strategies.

Implication for Patient Care.

Patient outcome projections are more complete when radiation exposure risk is explicitly included in imaging-related simulation models.

Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest: C.Y.K. Financial activities related to the present article: institution received a grant from the National Cancer Institute. Financial activities not related to the present article: none to disclose. Other relationships: none to disclose. J.M.L. Financial activities related to the present article: institution received grant K07CA128816 from the National Institutes of Health. Financial activities not related to the present article: none to disclose. Other relationships: none to disclose. P.M.M. Financial activities related to the present article: institution received grant R00 CA 126147, R01 CA 97337 from the National Cancer Institute and grant 2008A060554 from the American Cancer Society. Financial activities not related to the present article: institution received grant U01CA152956 from the National Cancer Institute. Other relationships: none to disclose. K.P.L. No potential conflicts of interest to disclose. Z.B.O. No potential conflicts of interest to disclose. J.D.E. No potential conflicts of interest to disclose. P.V.P. Financial activities related to the present article: institution received Career Development Award NIHK07133097 from the National Institutes of Health. Financial activities not related to the present article: none to disclose. Other relationships: none to disclose. G.S.G. Financial activities related to the present article: none to disclose. Financial activities not related to the present article: is a paid consultant to GE Healthcare. Other relationships: none to disclose.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Tina Motazedi, BA, Institute for Technology Assessment, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Mass, for assistance with preparation of this manuscript and Open Science Grid for providing computational resource. The authors also thank the CISNET Lung investigators for helpful discussions.

Received February 22, 2011; revision requested April 18; final revision received August 29; accepted September 16; final version accepted October 3.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grants K25CA133141, K07CA128816, and R00CA126147).

Abbreviations:

- BEIR

- Biologic Effects of Ionizing Radiation

- EAR

- excess absolute risk

- ERR

- excess relative risk

- ERRAA

- ERR for attained age

- ERRAE

- ERR for age at exposure

- LE

- life expectancy

- UI

- uncertainty interval

References

- 1.Mettler FA, Jr, Bhargavan M, Faulkner K, et al. Radiologic and nuclear medicine studies in the United States and worldwide: frequency, radiation dose, and comparison with other radiation sources—1950-2007. Radiology 2009;253(2):520–531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation Sources and effects of ionizing radiation. Medical radiation exposures, annex A. 2008 Report to the General Assembly with Annexes. New York, NY: United Nations, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements NCRP report no. 160. Bethesda, Md: National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mettler FA, Jr, Huda W, Yoshizumi TT, Mahesh M. Effective doses in radiology and diagnostic nuclear medicine: a catalog. Radiology 2008;248(1):254–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cardis E, Vrijheid M, Blettner M, et al. The 15-Country Collaborative Study of Cancer Risk among Radiation Workers in the Nuclear Industry: estimates of radiation-related cancer risks. Radiat Res 2007;167(4):396–416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brenner DJ, Doll R, Goodhead DT, et al. Cancer risks attributable to low doses of ionizing radiation: assessing what we really know. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2003;100(24):13761–13766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Muirhead CR, O’Hagan JA, Haylock RG, et al. Mortality and cancer incidence following occupational radiation exposure: third analysis of the National Registry for Radiation Workers. Br J Cancer 2009;100(1):206–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Research Council Health risks from exposure to low levels of ionizing radiation. BEIR VII Phase 2. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antoniou A, Pharoah PD, Narod S, et al. Average risks of breast and ovarian cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations detected in case series unselected for family history: a combined analysis of 22 studies. Am J Hum Genet 2003;72(5):1117–1130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Easton DF, Ford D, Bishop DT. Breast and ovarian cancer incidence in BRCA1-mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Am J Hum Genet 1995;56(1):265–271 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ford D, Easton DF, Bishop DT, Narod SA, Goldgar DE. Risks of cancer in BRCA1-mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Lancet 1994;343(8899):692–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ford D, Easton DF, Stratton M, et al. Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer families. The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium. Am J Hum Genet 1998;62(3):676–689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berrington de González A, Berg CD, Visvanathan K, Robson M. Estimated risk of radiation-induced breast cancer from mammographic screening for young BRCA mutation carriers. J Natl Cancer Inst 2009;101(3):205–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Law J, Faulkner K, Young KC. Risk factors for induction of breast cancer by x-rays and their implications for breast screening. Br J Radiol 2007;80(952):261–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee JM, Kopans DB, McMahon PM, et al. Breast cancer screening in BRCA1 mutation carriers: effectiveness of MR imaging—Markov Monte Carlo decision analysis. Radiology 2008;246(3):763–771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee JM, McMahon PM, Kong CY, et al. Cost-effectiveness of breast MR imaging and screen-film mammography for screening BRCA1 gene mutation carriers. Radiology 2010;254(3):793–800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Preston DL, Mattsson A, Holmberg E, Shore R, Hildreth NG, Boice JD., Jr Radiation effects on breast cancer risk: a pooled analysis of eight cohorts. Radiat Res 2002;158(2):220–235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hendrick RE, Pisano ED, Averbukh A, et al. Comparison of acquisition parameters and breast dose in digital mammography and screen-film mammography in the American College of Radiology Imaging Network digital mammographic imaging screening trial. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2010;194(2):362–369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McMahon PM, Kong CY, Weinstein MC, et al. Adopting helical CT screening for lung cancer: potential health consequences during a 15-year period. Cancer 2008;113(12):3440–3449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McMahon PM, Kong CY, Johnson BE, et al. Estimating long-term effectiveness of lung cancer screening in the Mayo CT screening study. Radiology 2008;248(1):278–287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McMahon PM, Kong CY, Bouzan C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of computed tomography screening for lung cancer in the United States. J Thorac Oncol 2011;6(11)1841–1848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McMahon PM. Policy assessment of medical imaging utilization: methods and applications [doctoral thesis]. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University, 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kong CY, McMahon PM, Gazelle GS. Calibration of disease simulation model using an engineering approach. Value Health 2009;12(4):521–529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Henschke CI, McCauley DI, Yankelevitz DF, et al. Early Lung Cancer Action Project: overall design and findings from baseline screening. Lancet 1999;354(9173):99–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Diederich S, Wormanns D, Semik M, et al. Screening for early lung cancer with low-dose spiral CT: prevalence in 817 asymptomatic smokers. Radiology 2002;222(3):773–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swensen SJ, Jett JR, Sloan JA, et al. Screening for lung cancer with low-dose spiral computed tomography. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165(4):508–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Spall JC. Introduction to stochastic search and optimization. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Interscience, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berrington de González A, Kim KP, Berg CD. Low-dose lung computed tomography screening before age 55: estimates of the mortality reduction required to outweigh the radiation-induced cancer risk. J Med Screen 2008;15(3):153–158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fujii K, Aoyama T, Yamauchi-Kawaura C, et al. Radiation dose evaluation in 64-slice CT examinations with adult and paediatric anthropomorphic phantoms. Br J Radiol 2009;82(984):1010–1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team, Aberle DR, Adams AM, et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med 2011;365(5):395–409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hricak H, Brenner DJ, Adelstein SJ, et al. Managing radiation use in medical imaging: a multifaceted challenge. Radiology 2011;258(3):889–905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brenner D, Elliston C, Hall E, Berdon W. Estimated risks of radiation-induced fatal cancer from pediatric CT. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2001;176(2):289–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Furukawa K, Preston DL, Lönn S, et al. Radiation and smoking effects on lung cancer incidence among atomic bomb survivors. Radiat Res 2010;174(1):72–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.