Abstract

Background

There are limited data regarding contemporary models of care delivery for patients undergoing congenital heart surgery. The purpose of this survey was to evaluate current US practice patterns in this patient population.

Methods

Cross-sectional evaluation of US centers caring for patients undergoing congenital heart surgery was performed using an internet-based survey. Data regarding post-operative care were collected and described overall, and compared in centers with a pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) vs. dedicated pediatric cardiac intensive care unit (CICU).

Results

A total of 94 (77%) of the estimated 122 US centers performing congenital heart surgery participated in the survey. The majority (79%) of centers were affiliated with a university. Approximately half were located in a free standing children’s hospital, and half in a children’s hospital in a hospital. Fifty-five percent provided care in a PICU vs. a CICU. A combination of cardiologists and/or critical care physicians made up the largest proportion of physicians primarily responsible for post-operative care. Trainee involvement most often included critical care fellows (53%), pediatric residents (53%), and cardiology fellows (47%). Many centers (76%) also utilized physician extenders. In centers with a CICU, there was greater involvement of cardiologists and physicians with dual training (cardiology and critical care), fellows vs. residents, and physician extenders.

Conclusion

Results of this survey demonstrate variation in current models of care delivery utilized in patients undergoing congenital heart surgery in the US. Further study is necessary to evaluate the implications of this variability on quality of care and patient outcomes.

Keywords: intensive care, congenital heart surgery, health policy

Introduction

Outcomes for infants and children undergoing congenital heart surgery have improved dramatically over the past three decades due to advances in the fields of pediatric cardiology and cardiac surgery, so that the majority of patients now survive into adulthood (1). However, evidence to guide optimal care in this patient population is still evolving, and few best practice guidelines exist. Recent studies have suggested significant variation from center to center in care for patients undergoing congenital heart surgery (2-6).

Wernovsky et al. described variation in the management of patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome undergoing stage 1 palliation, including wide variation between centers in location of care, operative and perfusion techniques, medications utilized, feeding regimens, and type of intra-operative and post-operative monitoring (7). This study focused on a single patient population and included international centers as well as US centers performing congenital heart surgery. Data regarding variation in models of care delivery for the overall cohort of patients undergoing congenital heart surgery at the estimated 122 centers in the US are limited (8). For example, in recent years there has been a shift toward care of post-operative patients in dedicated pediatric cardiac intensive care units (CICU) vs. general pediatric intensive care units (PICU) (9,10). However, data concerning the current distribution of post-operative care received in the CICU vs. PICU, and potential impact of this shift in care delivery on patient outcomes and trainee education are limited. The definition of current practice patterns is a necessary first step in evaluating outcomes associated with different models of care delivery, and in the development of subsequent education and quality improvement initiatives.

The purpose of this survey was to evaluate contemporary models of care delivery utilized by US centers for patients undergoing congenital heart surgery. In addition, we also compared characteristics of centers that provide post-operative care in a CICU vs. PICU.

Methods

Study Design

This cross-sectional evaluation utilized an internet-based survey constructed with commercially available software (www.surveymonkey.com). The survey was distributed in March 2009 to members of the following groups and listserves: Pediheart (pediheart.org), PICUList (pedsccm.org/Piculist.php), Pediatric Cardiac Intensive Care Society (pcics.org), and Pediatric Cardiac Intensive Care Unit Practitioners Group on Facebook (www.facebook.com) in an attempt to capture data from all US centers involved in the care of patients undergoing congenital heart surgery.

Data Collection

The distributed survey is displayed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Questionnaire

|

Analysis

Summary statistics were calculated and presented graphically. In cases where multiple responses from a center were received, there were cases where the answers to survey questions #2 and #3 were variable, therefore responses were combined for analysis. In addition, the response to survey question # 6 also varied from respondents from the same institution regarding “university hospital vs. “university affiliate”. Therefore these two categories were combined for analysis. Formal statistical comparisons were not made given the descriptive nature of the study. Results are presented for the overall cohort, and in the subgroup of centers with a PICU vs. CICU.

Results

Responses were received from 299 practitioners representing 94 US centers caring for patients undergoing congenital heart surgery.

Center characteristics

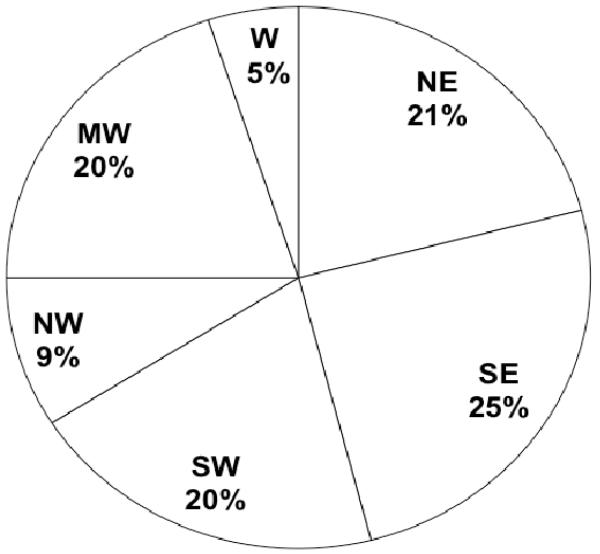

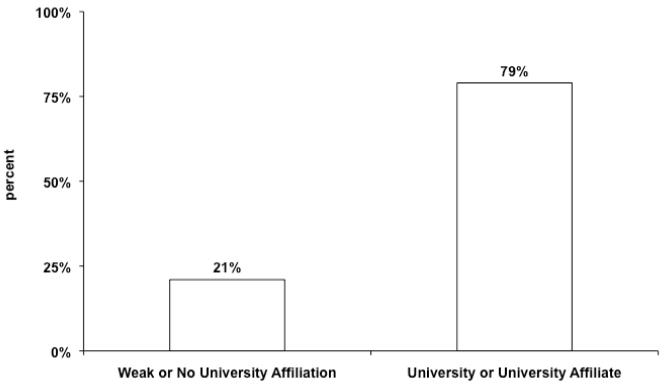

Figure 1 shows the geographical distribution of centers providing care to patients undergoing congenital heart surgery in the US. Fewer centers are located in the Northwest and West in comparison to other regions. Data regarding university affiliation are shown in Figure 2. The majority of centers identified themselves as a university hospital or university-affiliate. Figure 3 displays the distribution of type of children’s hospital. The proportion of centers who characterized themselves as a free standing children’s hospital or a children’s hospital in a hospital was similar.

Figure 1.

Center Region. NE = Northeast, SE = Southeast, SW = Southwest, NW = Northwest, MW = Midwest, and W = West

Figure 2.

Center Affiliation.

Figure 3.

Center Type.

Post-operative Care

The distribution of type of intensive care unit utilized for patients recovering from congenital heart surgery is shown in Figure 4. The proportion of centers who reported providing post-operative care in a PICU was slightly greater compared with those who utilize a CICU.

Figure 4.

Type of Intensive Care Unit. PICU = pediatric intensive care unit, CICU = pediatric cardiac intensive care unit

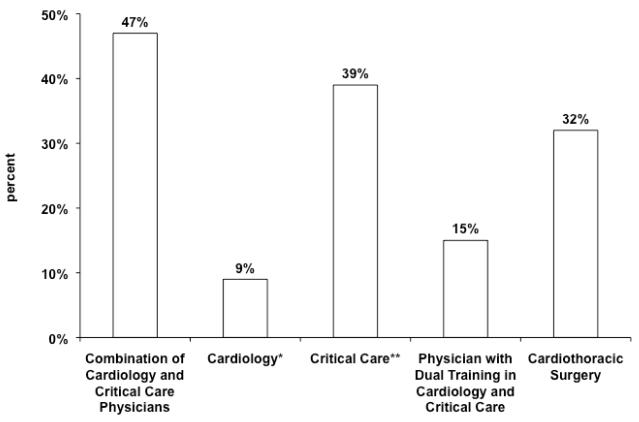

Figure 5 displays the distribution of attending physicians primarily responsible for post-operative care. A combination of cardiologists and/or critical care physicians made up the largest proportion of physicians primarily responsible for post-operative care. Approximately one third reported pediatric cardiothoracic surgeons were primarily responsible for post-operative care, and 15% reported this responsibility belonged to those with dual training in cardiology and critical care. There was often more than one group of physicians identified as being responsible for post-operative care; the most common composition of the team included: critical care only (26%), combination of cardiology and critical care (23%), critical care and cardiothoracic surgery (13%), and combination of cardiology, critical care, and cardiothoracic surgery (11%).

Figure 5.

Primary Responsibility for Post-operative Care. *without critical care involvement, **without cardiology involvement

In regard to surgeon practice, the majority of centers (72%) reported that their pediatric cardiovascular surgeons also operate on adults with congenital heart disease in addition to children. Thirteen percent reported their surgeon also operates on adults with acquired heart disease, and the remaining 15% reported that their surgeon operates solely on children with congenital heart disease.

Figure 6 shows the trainees and physician extenders involved in post-operative care. A similar proportion of centers reported involvement of critical care fellows, cardiology fellows, and pediatric residents in post-operative care. The majority of centers (76%) utilize physician extenders (either nurse practitioners or physician assistants). More than one group of trainees or physician extenders was involved in the majority of cases; the most common composition of the team included: both pediatric residents and nurse practitioners (12%), critical care and cardiology fellows with pediatric residents and nurse practitioners (10%), critical care and cardiology fellows with nurse practitioners (7%), and pediatric residents alone (7%). Of note, although most centers (60%) reported that fellows are involved in post-operative care, 23% of centers utilize pediatric residents without any fellows. Eleven percent reported only physician extenders provided post-operative care with no involvement of fellows or residents.

Figure 6.

Trainees and Physician Extenders involved in Post-operative Care. CICU = cardiac intensive care unit, NP = nurse practitioner, PA = physician assistant

CICU vs. PICU

Table 2 compares center characteristics and post-operative care in centers with a CICU vs. PICU. Centers with a CICU were more often affiliated with a university, and located in a free standing children’s hospital. There was greater involvement of cardiologists and physicians with dual training in both cardiology and critical care in post-operative care in centers with a CICU. In addition, more care was provided by fellows vs. residents and there was greater involvement of physician extenders in centers with a CICU.

Table 2.

Comparison of PICU and CICU Structure and Personnel

| PICU n = 52 |

CICU n=42 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | n | (%) | |

|

|

||||

| Center Region | ||||

| Northeast | 11 | (21%) | 9 | (21%) |

| Southeast | 9 | (17%) | 14 | (33%) |

| Southwest | 13 | (25%) | 6 | (14%) |

| Northwest | 6 | (12%) | 2 | (5%) |

| Midwest | 12 | (23%) | 7 | (17%) |

| West | 1 | (2%) | 4 | (10%) |

| University affiliation | ||||

| Yes | 36 | (69%) | 38 | (90%) |

| Type of Children’s Hospital | ||||

| Free standing children’s hospital | 16 | (31%) | 27 | (64%) |

| Children’s hospital in a hospital | 33 | (63%) | 12 | (29%) |

| Pediatric service in a hospital | 3 | (6%) | 3 | (7%) |

| Physicians Responsible for Post-op Care | ||||

| Combination of Cardiology and Critical Care Physicians |

18 | (35%) | 26 | (62%) |

| Cardiology only | 3 | (6%) | 5 | (12%) |

| Critical Care only | 28 | (54%) | 9 | (21%) |

| Dual Training in Cardiology and Critical Care |

2 | (4%) | 12 | (29%) |

| Cardiothoracic Surgery | 18 | (35%) | 12 | (29%) |

| Trainees and Physician Extenders Involved in Post-op Care |

||||

| Critical Care fellow | 21 | (40%) | 29 | (69%) |

| Cardiology fellow | 15 | (29%) | 29 | (69%) |

| CICU fellow | 1 | (2%) | 18 | (43%) |

| Pediatric Resident | 37 | (71%) | 13 | (31%) |

| Nurse Practitioner | 31 | (60%) | 31 | (74%) |

| Physician Assistant | 10 | (19%) | 13 | (31%) |

| Pediatric Cardiac Surgeon Practice | ||||

| Operates on children with CHD only | 12 | (23%) | 7 | (17%) |

| Operates on adults with CHD | 35 | (67%) | 33 | (79%) |

| Operates on adults with acquired HD | 9 | (17%) | 3 | (7%) |

PICU = pediatric intensive care unit, CICU = cardiac intensive care unit, CHD = congenital heart disease, HD = heart disease

Discussion

This contemporary evaluation of models of care utilized by US centers for patients undergoing congenital heart surgery demonstrates variation in center characteristics, and location and personnel involved in providing post-operative care to this population. Our survey captured over three quarters of the 122 US congenital heart surgery programs previously identified by the 2005 Society of Thoracic Surgeons Congenital Heart Surgery Manpower Survey as performing congenital heart surgery in the US (8). When comparing the results of this previous survey to the present analysis, the geographical distribution of centers performing congenital heart surgery was similar. Regarding surgeon practice, a similar proportion of congenital heart surgeons in the Manpower Survey reported that they operated on adults with congenital heart disease and adults with acquired heart disease when compared to our survey. This consistency between survey results supports the generalizability of our data to the overall population of programs performing congenital heart surgery.

The variation we identified regarding models of care delivery mirrors variation in other areas in the fields of pediatric cardiology and congenital heart surgery. Wernovsky et al. described center variation in the management of patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome, including virtually all aspects of peri-operative care for patients undergoing stage 1 palliation (7). Variation in the type of medications utilized in patients undergoing congenital heart surgery has also been reported. Checchia and colleagues performed a survey regarding center variation in use of corticosteroids in patients undergoing congenital heart surgery associated with cardiopulmonary bypass, and reported wide variation in corticosteroid type, dose, route, and timing of administration (2). In addition, variation in surgical management has also been reported including variation in timing of cavopulmonary anastomosis in patients with single ventricle defects, variation in utilization of delayed sternal closure in patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome, and variation in the management of patients with an anomalous aortic origin of a coronary artery (3-6).

Variability in practice can allow for treatment plans individualized to the patient and foster clinical innovation. However, a recent Institute of Medicine report recently concluded that variation in care was “illogical” and should be avoided (11). Significant variation in practice may highlight the lack of evidence in many cases to support best practices, and/or the resistance of some centers to change practice despite evidence-based guidelines. In either case, it has been shown that practice variation may account for a significant proportion of health care expenditures, which is of particular importance in this era of rising health care costs (12).

Few studies to date have evaluated the impact of variation in models of care delivery in this population on patient outcomes such as morbidity, mortality, and cost. In their study describing variation in use of delayed sternal closure, Johnson et al. reported that more frequent use was associated with prolonged length of stay and higher post-operative infection rates in patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome undergoing stage 1 palliation, adjusting for several other patient and center factors (3). Several studies have evaluated variation in center factors such as surgical volume and hospital teaching status and impact on outcome (13-20). Particularly for children undergoing high-risk procedures, lower surgical case volume has been shown to be associated with increased mortality (13-16). Undergoing surgery at a non-teaching hospital has also been associated with higher mortality for patients with hypoplastic left heart syndrome undergoing stage 1 palliation (19). It is unclear whether these factors are surrogate markers for other structural or process measures more directly impacting patient outcomes. In our analysis, we found significant variation among centers in many of these measures including the setting and location of post-operative care and personnel involved. Further study is needed to evaluate whether this variation is associated with any difference in quality of care or patient outcome.

Regarding the recent trend toward delivery of post-operative care in a dedicated CICU, we found that 45% of centers currently provide post-operative care in a CICU vs. general PICU. Interestingly, we found greater involvement of cardiologists and physicians trained in both cardiology and critical care in post-operative care in centers with a CICU. In addition, more care was provided by fellows vs. residents and there was greater involvement of physician extenders in centers with a CICU. The impact of these trends on patient outcomes, and on graduate medical education, has not been evaluated to date. Studies in other fields have suggested that increased involvement of physician extenders in patient care is associated with improved outcomes. For example, patients with minor injuries seen by nurse practitioners vs. pediatric residents in the emergency room had similar clinical outcomes, fewer unplanned follow-up visits, and greater patient satisfaction (21, 22). Christmas and colleagues also showed that incorporation of nurse practitioners into the surgical trauma service at a teaching hospital was associated with significant reductions in ICU and total hospital length of stay (23). In addition, it has also been suggested that the involvement of fellows in patient care is associated with improved outcomes. Arbabi et al. showed that centers with a critical care or trauma fellowship program had significantly decreased length of stay and mortality for trauma patients hospitalized with critical injuries (24). Further investigation is needed to evaluate whether variation in the setting or personnel involved in post-operative care impacts outcomes of patients undergoing congenital heart surgery.

Limitations

The limitations of this study are related to the voluntary nature of the survey and data validation. While the survey successfully obtained responses from over three quarters of centers caring for patients undergoing congenital heart surgery in the US, it is possible that selection bias may exist. However, given that the geographic distribution of centers and data on surgeon practice were similar between our study and a previous survey of the overall cohort of centers performing congenital heart surgery, significant selection bias is less likely. In addition, data in this study represent the perception of survey respondents from each institution. Responses were not independently validated. This may impact data concerning personnel involved in post-operative care where a team approach is most often utilized, and responses were not always concordant between multiple respondents from the same institution. For this reason, we combined responses to this question in order to describe all personnel thought to play a role. Finally, there is likely variation in many other aspects of post-operative care not assessed by this survey. While our goal with this initial survey was to describe general institutional practices regarding the care of patients undergoing congenital heart surgery, there are likely several other important factors involved, and further evaluation focused in greater detail on the make-up of the care team, location of care, and processes involved will be necessary.

Conclusions

This study describes significant variation in current models of care delivery for patients undergoing congenital heart surgery in the US, both in regard to center characteristics and the setting and personnel involved in post-operative care. While characterization of current practice patterns is an important first step, further more detailed evaluation of variation in structural and process measures utilized by different centers and evaluation of quality of care and outcomes associated with this variation is necessary in order to define best practices and improve quality of care in this population.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Pasquali receives grant support (KL2 RR024127-02) from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, and from the American Heart Association (AHA) Mid-Atlantic Affiliate Clinical Research Program. The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR, NIH, or AHA.

Footnotes

Disclosures None

References

- 1.Boneva RS, Botto LD, Moore CA, Yang Q, Correa A, Erickson JD. Mortality associated with congenital heart defects in the United States: trends and racial disparities, 1979-1997. Circulation. 2001;103:2376–81. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.19.2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Checchia PA, Bronicki RA, Costello JM, Nelson DP. Steroid use before pediatric cardiac operations using cardiopulmonary bypass: An international survey of 36 centers. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2005;6:441–4. doi: 10.1097/01.PCC.0000163678.20704.C5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson JN, Jaggers J, Li JS, et al. Center variation and outcomes associated with delayed sternal closure following stage 1 palliation for hypoplastic left heart syndrome. Congenit Heart Dis. 2009;4:401. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.11.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaquiss RD, Ghanayem NS, Hoffman GM, et al. Early cavopulmonary anastomosis in very young infants after the Norwood procedure: impact on oxygenation, resource utilization, and mortality. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;127:982–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2003.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kogon BE, Plattner C, Leong T, Simsic J, Kirshbom PM, Kanter KR. The bidirectional Glenn operation: a risk factor analysis for morbidity and mortality. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;136:1237–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brothers J, Gaynor JW, Paridon S, Lorber R, Jacobs M. Anomalous Aortic Origin of a Coronary Artery with an Interarterial Course: Understanding Current Management Strategies in Children and Young Adults. Pediatr Cardiol. 2009;30:911–21. doi: 10.1007/s00246-009-9461-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wernovsky G, Ghanayem N, Ohye RG, et al. Hypoplastic left heart syndrome: consensus and controversies in 2007. Cardiol Young. 2007;17:S75–86. doi: 10.1017/S1047951107001187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacobs ML, Mavroudis C, Jacobs JP, Tchervenkov CI, Pelletier GJ. Report of the 2005 STS Congenital Heart Surgery Practice and Manpower Survey. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:1152–8. 1159e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.04.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chang AC. Pediatric cardiac intensive care: current state of the art and beyond the millennium. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2000;12:238–46. doi: 10.1097/00008480-200006000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang AC. How to start and sustain a successful pediatric cardiac intensive care program: A combined clinical and administrative strategy. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2002;3:107–11. doi: 10.1097/00130478-200204000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Committee on Quality of Health Care in America Institute of Medicine Crossing the Quality Chasm: A new Health System for the 21st Century. Recommendation. 2001;4.5:8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fisher ES, Bynum JP, Skinner JS. Slowing the growth of health care costs--lessons from regional variation. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:849–52. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0809794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Welke KF, O’Brien SM, Peterson ED, Ungerleider RM, Jacobs ML, Jacobs JP. The complex relationship between pediatric cardiac surgical case volumes and mortality rates in a national clinical database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:1133–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirsch JC, Gurney JG, Donohue JE, Gebremariam A, Bove EL, Ohye RG. Hospital mortality for Norwood and Arterial Switch Operations as a function of institution volume. Pediatr Cardiol. 2008;29:713–17. doi: 10.1007/s00246-007-9171-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Checchia PA, McCollegan M, Daher N, Kolovos N, Levy F, Markovitz B. The effect of surgical case volume on outcome after the Norwood procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2005;129:754–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Welke KF, Diggs BS, Karamlou T, Ungerleider RM. The relationship between hospital surgical case volumes and mortality rates in pediatric cardiac surgery: a national sample, 1988-2005. Ann Thorac Surgery. 2008;89:889–96. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.04.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hannan EL, Racz M, Kavey R, Quaegebeur JM, Williams R. Pediatric Cardiac Surgery: The effect of hospital and surgeon volume on in-hospital mortality. Pediatrics. 1998;101:963–69. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.6.963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bazzani LG, Marcin JP. Case Volume and Mortality in Pediatric Cardiac Surgery Patients in California, 1998-2003. Circulation. 2007;115:2652–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.678904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Berry JG, Cowley CG, Hoff CJ, Srivastava R. In-hospital mortality for children with hypoplastic left heart syndrome after stage I surgical palliation: teaching versus nonteaching hospitals. Pediatrics. 2006;117:1307–13. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chang RR, Klitzner TS. Can regionalization decrease the number of deaths for children who undergo cardiac surgery? A theoretical analysis. Pediatrics. 2002;109:173–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.2.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sakr M, Angus J, Perrin J, Nixon C, Nicholl J, Wardrope J. Care of minor injuries by emergency nurse practitioners or junior doctors: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 1999;354:1321–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)02447-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cooper MA, Lindsay GM, Kinn S, Swann IJ. Evaluating emergency nurse practitioner services: a randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs. 2002;40:721–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02431.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Christmas AB, Reynolds J, Hodges S, et al. Physician extenders impact trauma systems. J Trauma. 2005;58:917–20. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000162736.06947.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arbabi S, Jurkovich GJ, Rivara FP, et al. Patient outcomes in academic medical centers: influence of fellowship programs and in-house on-call attending surgeon. Arch Surg. 2003;138:47–51. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]