Abstract

Cellular senescence is characterized by an irreversible cell cycle arrest that, when bypassed by mutation, contributes to cellular immortalization. Activated oncogenes induce a hyperproliferative response, which might be one of the senescence cues. We have found that expression of such an oncogene, Akt, causes senescence in primary mouse hepatoblasts in vitro. Additionally, AKT-driven tumors undergo senescence in vivo following p53 reactivation and show signs of differentiation. In another in vivo system, i.e., liver fibrosis, hyperproliferative signaling through AKT might be a driving force of the senescence in activated hepatic stellate cells. Senescent cells up-regulate and secrete molecules that, on the one hand, can reinforce the arrest and, on the other hand, can signal to an innate immune system to clear the senescent cells. The mechanisms governing senescence and immortalization are overlapping with those regulating self-renewal and differentiation. These respective control mechanisms, or their disregulation, are involved in multiple pathological conditions including fibrosis, wound healing, and cancer. Understanding extracellular cues that regulate these processes may enable new therapies for these conditions.

Cellular senescence is a stable formof a cell cycle arrest program that limits the proliferative potential of cells and thereby prevents immortalization. Initially defined by the phenotype of human fibroblasts undergoing replicative exhaustion in culture (Hayflick and Moorhead 1961), senescence can be triggered in many cell types in response to diverse forms of cellular damage or stress (Serrano et al. 1997; Campisi and d’Adda di Fagagna 2007). Senescent cells display a large flattened morphology and accumulate a senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity distinguishing them from most quiescent cells (Campisi and d’Adda di Fagagna 2007). An additional feature of senescent cells is an accumulation of the senescence-associated heterochromatin that functions to repress the expression of certain genes responsible for the cell cycle progression (Narita et al. 2003). Consistent with its function in halting cellular proliferation, senescence also has an important role in tumor suppression. In addition, it has been suggested that senescence contributes to stem cell depletion or the decline of tissue regeneration capabilities during aging (Rossi et al. 2008).

One of the most potent triggers of senescence is DNA damage, which is induced by telomere attrition during replicative exhaustion (Vaziri et al. 1997). In the absence of the telomerase enzyme, mutations that overcome senescence allow continued proliferation in the presence of sustained DNA damage, leading to rampant genetic instability and eventually cancer progression. Consistent with the fact that many conventional chemotherapeutic agents can directly or indirectly damage DNA, senescent cells can accumulate in malignant tumors following chemotherapy (Schmitt et al. 2002; te Poele et al. 2002; Roninson 2003). Indeed, in a mouse lymphoma model, an intact senescence machinery contributes to a positive response to chemotherapy in vivo.

Several activated oncogenes can induce senescence, in part, through signals initiated by DNA damage or replicative stress. Although, on the one hand, paradoxically, this phenomenon can be rationalized by suggesting that normal cells possess cellular fail-safe mechanisms that counter the cancer-promoting effects of hyperproliferative mutations (Serrano et al. 1997). During the past several years, this “oncogene-induced senescence” has been established as an important tumor suppressor mechanism that constrains tumorigenesis in multiple forms of cancer in humans and mice. For example, nevi, premalignant lesions of melanoma in the human skin, contain senescent melanocytes bearing mutations in the BRAF gene (Michaloglou et al. 2005). Neurofibromas from NF1 mutant patients contain senescent cells in which a genetic defect in the NF1 gene leads to constitutively high levels of Ras activity (Courtois-Cox et al. 2006). Benign lesions of the prostate in human patients and mice lacking the tumor suppressor PTEN contain senescent cells, and disruption of the senescence program in mice leads to tumor progression (Chen et al. 2005). In mouse models of several cancers including lymphoma (Braig et al. 2005), hyperplasia of the pituitary gland (Lazzerini Denchi et al. 2005), skin carcinoma (Collado et al. 2005), and melanocytic lesions of UV-irradiated hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor (HGF/SF) transgenic mice (Ha et al. 2007), premalignant lesions were shown to be limited by oncogene-induced senescence.

Consistent with the role of cellular senescence as a barrier to malignant transformation, senescent cells activate the p53 and p16/Rb (retinoblastoma) tumor suppressor pathways (Mooi and Peeper 2006; Campisi and d’Adda di Fagagna 2007; Collado et al. 2007). p53 promotes senescence by trans-activating genes that inhibit proliferation, including the p21/Cip1/Waf1 cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor and miR-34 class of microRNAs (He et al. 2007a). In contrast, p16INK4a promotes senescence by inhibiting cyclin-dependent kinases 2 and 4, thereby preventing Rb phosphorylation and allowing Rb to promote a repressive heterochromatin environment (Narita et al. 2003). Both the Rb and p53 tumor suppressor pathways are negatively regulated by Bmi-1, CBX7, and other members of Polycomb repression complexes (Gil et al. 2005); these complexes act at the chromatin level of chromatin to repress the INK4a and ARF genes, both embedded in the same genomic locus on chromosome 9p.

In addition to up-regulation of the p53 and p16/Rb pathways, senescent cells often up-regulate inflammatory cytokines and other molecules known to modulate the microenvironment or immune response (Campisi and d’Adda di Fagagna 2007). Recently, high-throughput genetic approaches have identified several secreted molecules that functionally contribute to senescence (Acosta et al. 2008; Kuilman et al. 2008; Wajapeyee et al. 2008). In these studies, the secreted proteins insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-7 (IGFBP7) and interleukin-6 (IL-6) contribute to senescence induced by a mutant form of BRAF, suggesting that these factors might attenuate tumorigenesis. Another secreted cytokine, IL-8, and its receptor, CXCR2, appear to reinforce both replicative and oncogene-induced senescence (Acosta et al. 2008). The ability of secreted molecules to affect senescence is likely to have both autocrine and paracrine effects. Although the autocrine signaling might enforce senescence, its effect on the microenvironment might be coordinately different and depend on the nature of neighboring cells.

Our laboratory has been interested in the roles and regulation of cellular senescence for more than a decade. We previously established that oncogenes could trigger senescence (Serrano et al. 1997) and demonstrated that cellular senescence can contribute to the outcome of cancer chemotherapy (Schmitt et al. 2002). Later, we studied the molecular mechanisms of senescence and implicated chromatin-modulating factors and the miR-34 family of microRNAs as key regulators of the senescence program (Narita et al. 2003, 2006; He et al. 2007b). More recently, we studied the role of senescence in the biology of liver disease, including liver fibrosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (Xue et al. 2007; Krizhanovsky et al. 2008).

Most commonly, liver disease is caused by hepatitis viruses B and C and chronic alcohol abuse or is associated with obesity leading to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, initially resulting in liver fibrosis (Bataller and Brenner 2005). Eventually, persistent liver damage leads to the development of liver cirrhosis, a major health problem worldwide (Bataller and Brenner 2005) and the 12th most common cause of death in the United States (NCHS 2004). In turn, liver fibrosis and cirrhosis are two of the main risk factors for developing hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Several reports suggest that up to 90% of HCC cases have a natural history of unresolved inflammation and severe fibrosis irrespective of the underlying cause of liver disease (Elsharkawy and Mann 2007). In biopsies, liver fibrosis is characterized by depositions of the extracellular matrix (ECM) known as fibrotic scars, which is deposited by activated hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), the main fibrogenic cell type in the liver. HSCs normally reside in proximity to blood vessels in the liver and are the main site of vitamin A storage in the body (Bataller and Brenner 2005). Upon liver injury, signaling from damaged hepatocytes leads to HSC activation, resulting in intensive proliferation of HSCs, migration from their normal location, ECM deposition, and formation of fibrotic scars. Recently, we demonstrated that senescence functions as both a tumor suppressive mechanism in liver carcinoma and a program that limits liver fibrosis.

SENESCENCE ACCOMPANIES P53 REACTIVATION IN A MOUSE MODEL OF HCC

We previously used a mouse model of liver carcinoma to determine the consequence of reactivating the p53 pathway in liver tumors (Xue et al. 2007). We used RNA interference (RNAi) to conditionally regulate endogenous p53 expression using a p53 miR-30 design short hairpin RNA (shRNA) expressed from a conditional tetracycline-responsive promoter as described previously (Dickins et al. 2005). Embryonic hepatoblasts were transduced with retroviruses that express oncogenic HrasV12, the tetracycline trans-activator protein tTA (“tet-off ”) and the p53 shRNA. In the absence of doxycycline (Dox), p53 shRNA knocked down p53 expression efficiently and led to hepatocarcinoma development when the triple-transduced cells were transplanted into recipient mice (Xue et al. 2007). Addition of Dox and p53 reactivation resulted in tumor regression. Interestingly, we found that p53 reactivation in the tumor cells led to cellular senescence and not apoptosis, which was also associated with markers of cellular differentiation (see Figure S3 in Xue et al. 2007). Senescent cells triggered an immune response in vivo, resulting in infiltration of immune cells into the tumor and clearance of senescent cells. These results suggest that loss of a tumor suppressor may be required for the maintenance of some tumors; moreover, during cellular senescence in this system, cell-autonomous processes and non-cell-autonomous processes cooperate to eliminate the formerly malignant cell.

P53 REACTIVATION LEADS TO SENESCENCE IN CELLS THAT DEREGULATE PI3K SIGNALING

The phosphoinositol-3 kinase (PI3K) signaling pathway is an important component of the intracellular signaling cascade downstream from the Ras family of GTPases, which, when activated, are some of the most potent human oncogenes and triggers of senescence. Moreover, the PI3K pathway is frequently activated by genomic aberrations across many cancer lineages (Brugge et al. 2007). Hyperactivation of this pathway through loss of the PTEN tumor suppressor can promote cell proliferation and survival, but like oncogenic Ras, it can trigger senescence in some cell types (Chen et al. 2005).

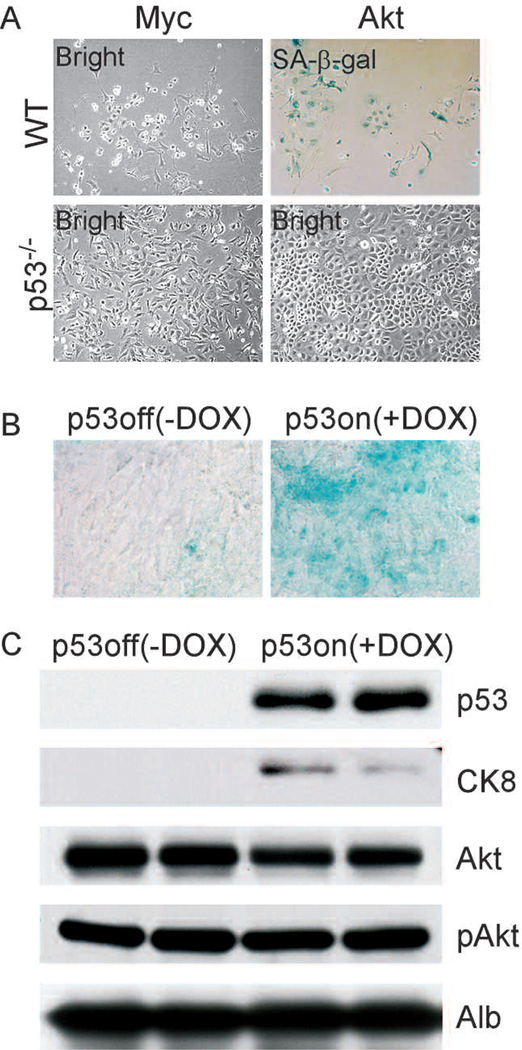

We have previously shown that hyperactivation of the PI3K pathway, for example, by deregulation of Akt, together with p53 loss could promote hepatocellular carcinoma development (Zender et al. 2006). To determine whether tumors driven by deregulation of PI3K signaling respond to p53 reactivation by senescence, we studied the consequence of expression of a key PI3K target, Akt, in embryonic hepatoblasts (embryonic liver progenitor cells). Embryonic hepatoblasts were prepared from wild-type and p53−/− animals and were infected with retroviruses that expressed activated Akt (myr-Akt) (Wendel et al. 2004). Hepatoblasts derived from wild-type embryos infected with Akt exhibit flattened morphology and stain positive for SA-β-gal, whereas p53−/− hepatoblasts continue to proliferate and easily reach confluence when seeded at low density (Fig. 1A). These results suggest that Akt expression induces senescence in a manner that is dependent on p53.

Figure 1.

AKT induces cellular senescence and differentiation in cooperation with p53. (A) Wild-type (WT) but not p53−/− primary hepatoblasts senesce in response to AKT. (B) AKT-driven tumor cells senesce in vivo in response to p53 restoration (+DOX), but not in the absence of p53 (−DOX). (C) Expression of the differentiation marker CK8 was increased in tumors following p53 restoration.

To further understand the cooperation between Akt and p53 in senescence, we conditionally repressed p53 in Akt-transduced hepatoblasts. In addition to Akt, hepatoblasts were transduced with the tetracycline trans-activator protein tTA and a tet-responsive p53 shRNA and seeded subcutaneously into athymic nude mice. In the absence of Dox, expression of p53 was suppressed, leading to the development of aggressive liver carcinomas. Upon tumor formation, mice were left untreated or treated with Dox to suppress the p53 shRNA. Following Dox treatment, p53 was induced, and a substantial percentage of tumor cells became SA-β-gal positive (Fig. 1B); moreover, the tumors shrank and virtually disappeared after 20 days (Xue et al. 2007). In contrast, tumors present in untreated mice remained SA-β-gal negative and continued to grow. Therefore, like tumors expressing oncogenic HrasV12, Akt-transformed hepatoblasts undergo senescence in vivo upon p53 reactivation.

In liver carcinomas expressing oncogenic ras, the onset of cellular senescence correlated with the appearance of differentiation markers (Xue et al. 2007). In these tumors, expression of differentiation markers cytokeratin 7 (CK7) and CK8 was lower in the absence of p53 than in its presence. Conversely, α-fetoprotein (AFP), which is typically expressed in progenitor cells and reduced upon differentiation, was detected in the tumors in the absence of p53 but down-regulated upon p53 reactivation (Xue et al. 2007). Similarly, CK8 was induced following p53 reactivation in tumors expressing activated Akt (Fig. 1B). Therefore, along with induction of senescence, tumors show signs of differentiation following p53 reactivation.

SENESCENCE RESPONSE PROTECTS AGAINST LIVER FIBROSIS

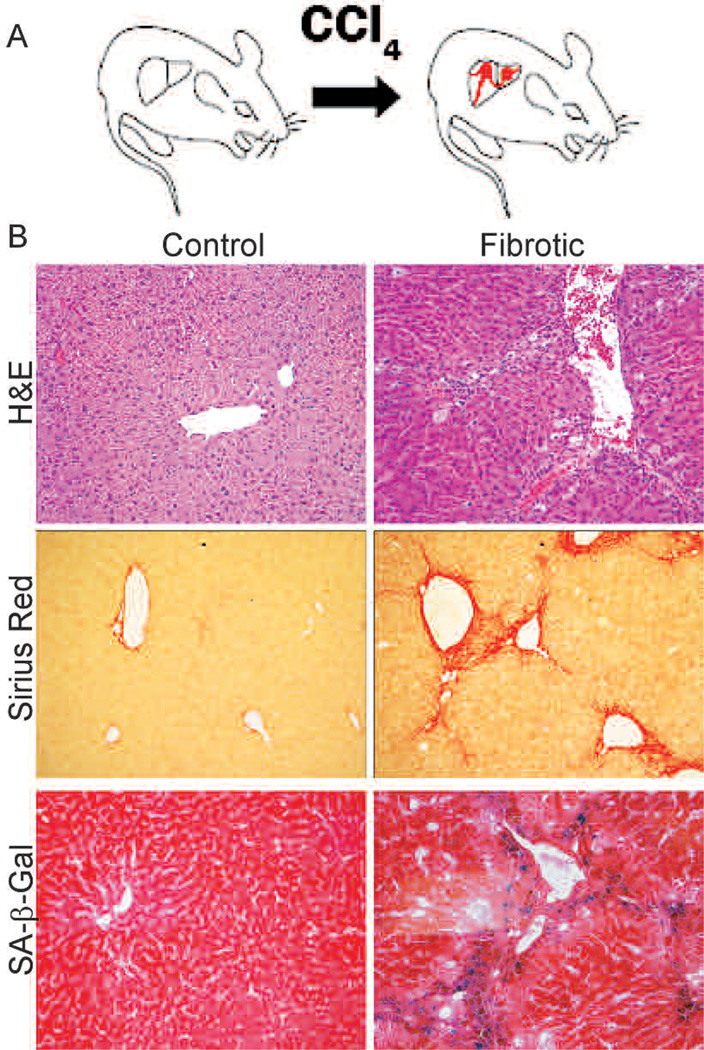

Liver fibrosis caused by various types of liver damage can lead to cirrhosis, liver failure, or the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (Bataller and Brenner 2005). To investigate the role of cellular senescence in fibrosis progression, we induced fibrosis in mice by twice-weekly treatment with 1 ml/kg of CCl4 for 6 weeks (Fig. 2A). This course of treatment is believed to induce mild cirrhosis in mouse liver (Rudolph et al. 2000), and, indeed, CCl4-treated mice often displayed enlarged abdomens (Krizhanovsky et al. 2008), a phenotype that can be attributed to the ascites that often accompanies cirrhosis.

Figure 2.

Senescent cells are present in mouse fibrotic liver. (A) Mice were treated with CCl4 twice weekly for 6 weeks. (B) CCl4-treated livers (fibrotic) but not control livers exhibit fibrotic scars (evaluated by H&E and Sirius Red staining). Multiple cells adjacent to the scar stain positively for the senescence marker SA-β-gal.

Livers from treated and untreated mice were dissected, and general liver architecture was evaluated by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Additionally, the presence of excessive ECM (Sirius Red) and the presence of senescent (SA-β-gal positive) cells were assessed. Livers from mice treated with CCl4, but not vehicle, showed a distinctive fibrotic morphology and accumulated ECMin the fibrotic scars (Fig. 2B). Cells that stained positively for the senescence marker SA-β-gal were predominantly found in the areas adjoining fibrotic scars, the site of HSC proliferation, migration, and fibrotic ECM production (Fig. 2B). We find that cells in this region express senescence markers p16, p53, p21, and Hmga1 (Krizhanovsky et al. 2008).

On the basis of the observations above, we hypothesized that senescent cells might derive from activated stellate cells. Accordingly, the senescence markers p53 and Hmga1 were expressed in cells that were positive for αSMA and Desmin, markers of activated stellate cells (Krizhanovsky et al. 2008). Therefore, senescent activated stellate cells are present in chemically induced fibrotic livers in mice. Similar cells were also observed in livers from human patients with liver fibrosis (Krizhanovsky et al. 2008).

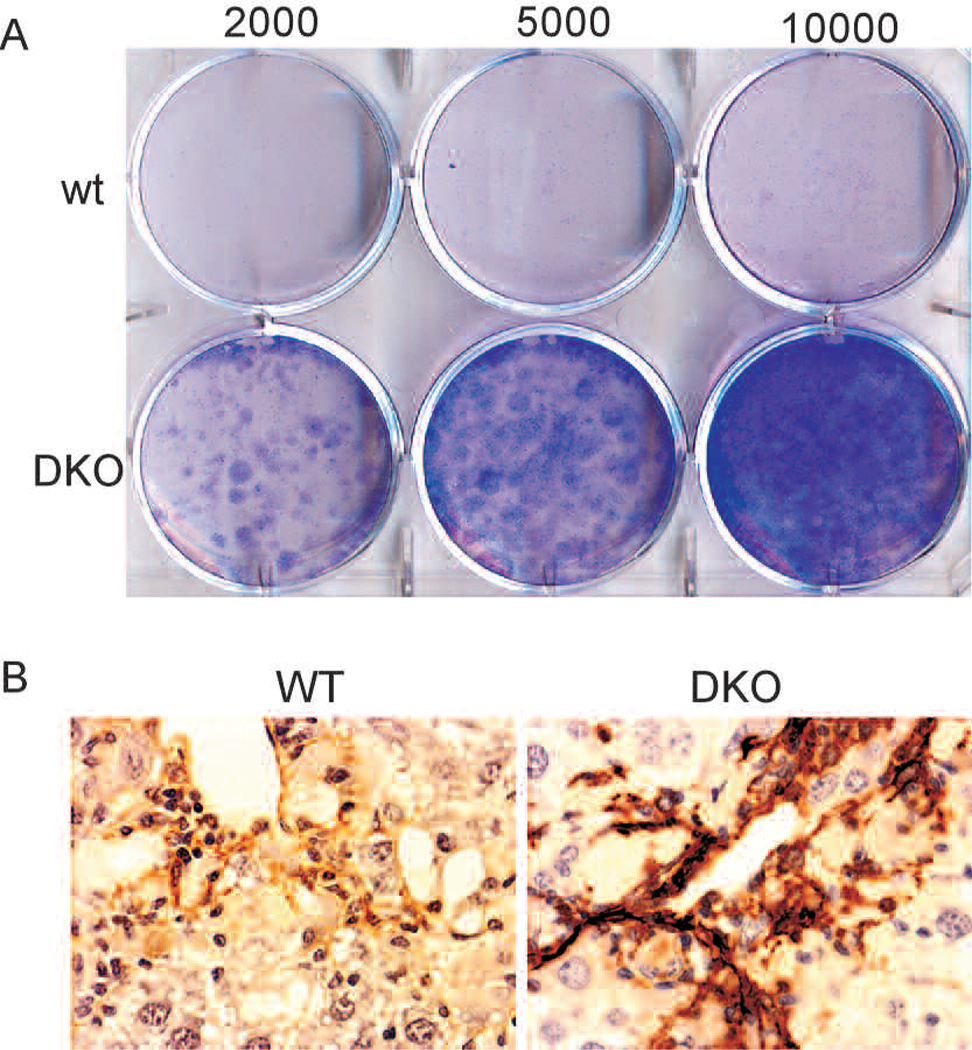

Both the p53 and p16/Rb pathways contribute to senescence in a cell-type-dependent manner, such that cells lacking either pathway alone sometimes retain a residual senescence response (Beausejour et al. 2003; Shay and Roninson 2004). To determine the impact of disrupting both loci on senescence and fibrosis in the liver, we produced p53−/−;INK4a/ARF−/− compound mutant mice. Hepatic stellate cells were then prepared from wild-type and p53−/−;INK4a/ARF−/− animals. When plated at low density in standard media, these cells became activated and expressed αSMA within 2 weeks (Krizhanovsky et al. 2008).

We allowed wild-type and p53−/−;INK4a/ARF−/− stellate cells to become activated in vitro and examined their proliferative capacity 10 days thereafter in colony-formation assays. Whereas wild-type cells eventually undergo senescence in vitro and do not form colonies, p53−/−;INK4a/ARF−/− cells do not undergo senescence and continue to proliferate (Fig. 3A). Moreover, p53−/−;INK4a/ARF−/− cells display increased bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation compared to wild-type cells (Krizhanovsky et al. 2008). These results demonstrate that p53−/−;INK4a/ARF−/−-activated stellate cells are immortalized in vitro.

Figure 3.

p53−/−;Ink4a/ARF−/− activated stellate cells are immortalized and contribute to fibrosis progression. (A) p53−/−;Ink4a/ARF−/− (DKO) but not wild-type-activated stellate cells form colonies following a 10-day colony-formation assay in vitro as evaluated by crystal violet staining. Numbers indicate amount of cells seeded per well. (B) Immunostaining identified higher expression of the activated stellate cell marker αSMA in fibrotic livers from DKO mice compared to wild-type mice.

To identify the consequences of impaired activated stellate cell senescence in vivo, we induced fibrosis in wild-type and p53−/−;INK4a/ARF−/− mice and tested their livers for fibrosis progression and amount of stellate cells. Liver fibrosis was significantly more pronounced in mutant p53−/−;INK4a/ARF−/− mice than in wild-type mice (Krizhanovsky et al. 2008) and was accompanied by a significant increase in the expression of the activated stellate cell marker αSMA (Fig. 3B) (see also Krizhanovsky et al. 2008). Therefore, senescence of activated stellate cells in wild-type mice protects the liver from unlimited expansion of these cells and more severe fibrosis.

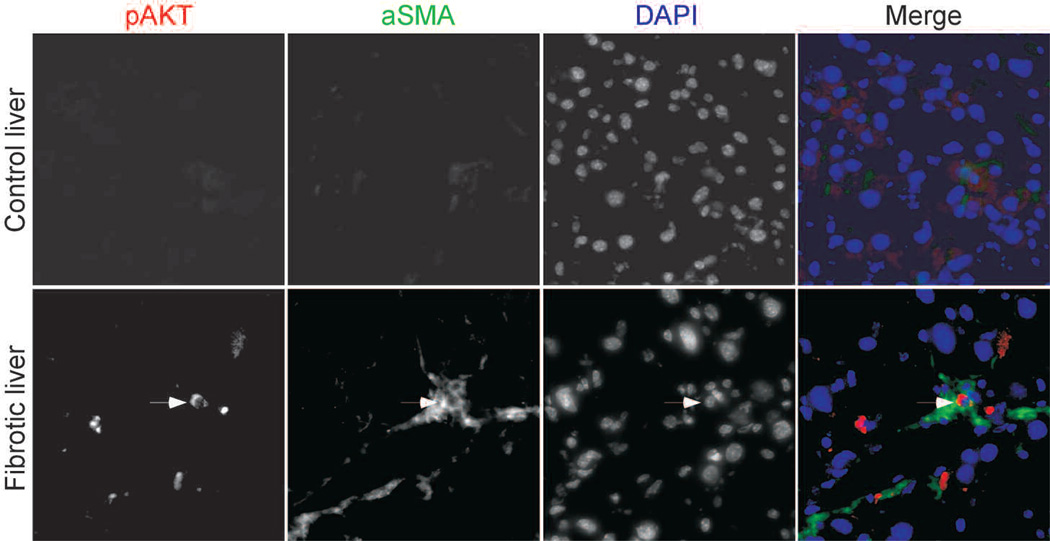

EVIDENCE FOR HYPERPROLIFERATIVE SIGNALS IN ACTIVATED STELLATE CELLS

Several stimuli might be responsible for inducing senescence in activated stellate cells during the course of liver fibrosis. Telomere shortening is the driving force for senescence of normal human cells in culture (Campisi and d’Adda di Fagagna 2007); however, mouse cells have long telomeres, and it is therefore unlikely that in our model, telomeres in activated stellate cells will shorten sufficiently during the treatment period to lead to senescence. A boost in proliferation was observed before senescence in cells that undergo activated oncogene-induced senescence (Lin et al. 1998). We therefore examined fibrotic livers for the presence of activated Akt, which can mediate senescence in liver progenitor cells and other cell types (Chen et al. 2005). Indeed, elevated levels of an active phosphorylated AKT (Ser-473) were detected in cells positive for the stellate cell marker αSMA in fibrotic livers but not control livers (Fig. 4). Moreover, when we propagated human activated stellate cells in culture, phosphorylated AKT was detected in a proportion of late-passage cells (Krizhanovsky et al. 2008). These results are consistent with the possibility that the senescence of activated stellate cells is triggered by a hyperproliferative signal mediated, at least in part, by AKT.

Figure 4.

AKT signaling might contribute to the senescence of activated stellate cells. pAKT was detected in cells expressing the activated stellate cell marker αSMA in mouse fibrotic livers. Nuclei were identified by DAPI.

SENESCENT ACTIVATED STELLATE CELLS ARE TARGETS OF THE IMMUNE SYSTEM IN VIVO

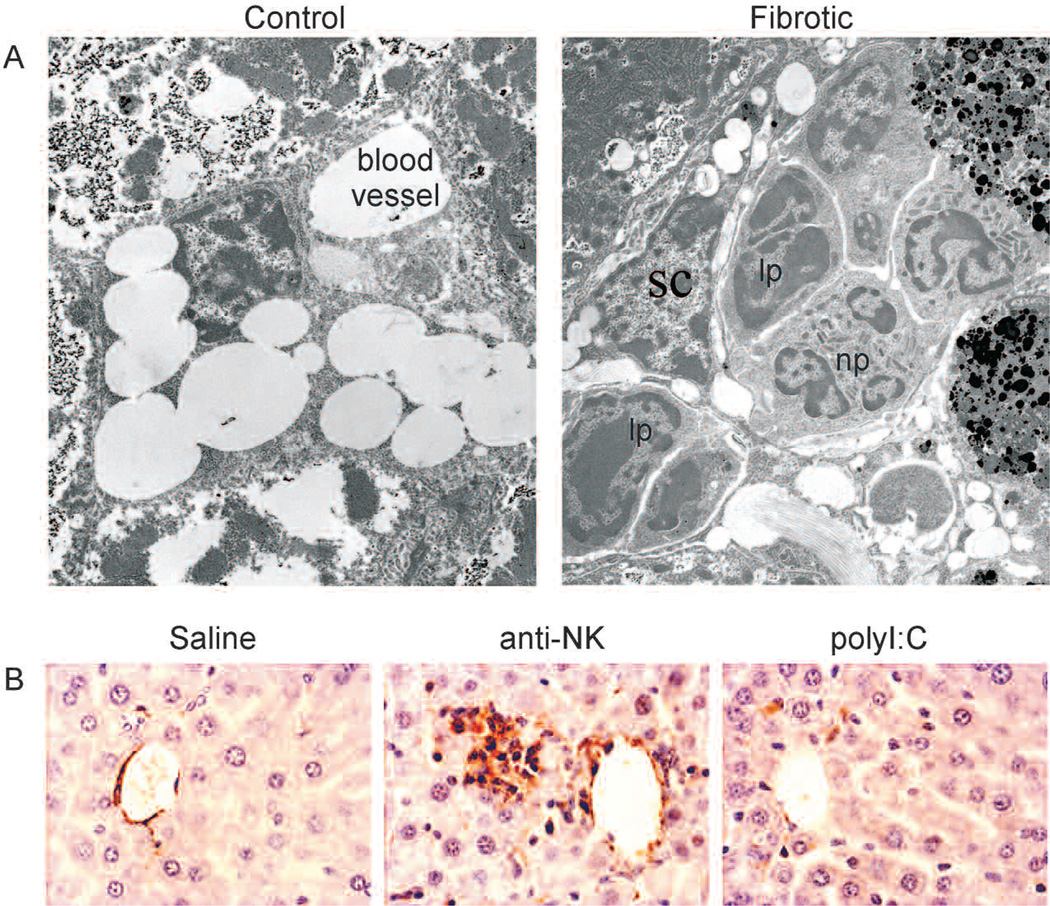

Interestingly, within 20 days of stopping CCl4 treatment, liver fibrosis was almost resolved and senescent cells were not detected. Our previous work indicates that senescent cells can be cleared from tumors by the components of the innate immune system (Xue et al. 2007). Moreover, we have shown that senescent activated stellate cells up-regulate the expression of molecules involved in natural killer (NK) cell recognition and, furthermore, can be preferentially targeted by these cells in vitro (Krizhanovsky et al. 2008). In the fibrotic liver, immune cells (including NK cells) migrate into the fibrotic scar and create an inflammatory environment (Bataller and Brenner 2005;Muhanna et al. 2007). Using a combination of electron microscopy and immunophenotying by immunofluorescence, we noted that lymphocytes (including NK cells), macrophages, and neutrophils were detected adjacent to HSCs in fibrotic livers from CCl4-treated mice (Fig. 5A) (Krizhanovsky et al. 2008). These immune cells were often in close proximity to cells expressing the senescent markers p53, p21, and Hmga1 (Krizhanovsky et al. 2008). Therefore, immune cells are localized adjacent to senescent activated stellate cells in fibrotic liver.

Figure 5.

The immune system facilitates the clearance of senescent activated stellate cells in vivo. (A) Electron microscopy revealed that immune cells ([lp] lymphocytes; [np] neutrophil) are adjacent to activated HSCs in fibrotic mouse livers but not in normal mouse livers. (B) Mice treated with CCl4 were treated with an anti-NK antibody (to deplete NK cells), polyI:C (as an interferon-γ activator), or saline (as a control) for 10 days. More activated stellate cells, identified by αSMA, are retained in mouse livers following depletion of NK cells.

To evaluate an impact of the innate immune response on clearance of the senescent activated stellate cells and fibrosis resolution in vivo, we tested the impact of modulating NK cell activity on these processes in fibrotic livers. Following cessation of the fibrogenic stimulus, mice were treated with anti-NK neutralizing antibody to deplete NK cells or with polyI:C to induce an interferon-γ response and enhance NK cell activity. Livers from mice treated with the anti-NK antibody retained more senescent cells and fibrosis than controls, whereas senescent cells and fibrosis were more rapidly cleared in livers from mice treated with polyI:C (Krizhanovsky et al. 2008). We examined these livers for the presence of activated stellate cells by immunostaining. Numerous activated stellate cells were retained in the livers of anti-NK antibody-treated mice (Fig. 5B). In contrast, activated stellate cells were almost completely eliminated in the livers of polyI:C-treated mice. Therefore, the innate immune system can contribute to the elimination of senescent stellate cells from the fibrotic liver.

CELL-AUTONOMOUS AND NON-CELL-AUTONOMOUS EFFECTS OF SENESCENCE DURING TUMORIGENESIS AND WOUND HEALING

In cancer, senescence can serve as a tumor suppressor mechanism in multiple ways. First, oncogene-induced senescence provides an initial barrier to the development of malignancies in skin, prostate, and hematopoietic and other systems, whereas telomere-based senescence may attenuate tumor progression (Narita and Lowe 2005). Second, upon tumor presentation, senescence can be induced in some tumor cells by chemotherapy agents (Schmitt et al. 2002). We have demonstrated that reactivation of the p53 pathway in tumors leads to activation of the senescence program and tumor clearance by the innate immune system in vivo (Xue et al. 2007). Therefore, the senescence machinery can remain intact in advanced cancers, where it remains capable of halting proliferation of tumor cells or cells carrying a strong oncogenic signal. If these processes occur in premalignant settings, senescence would limit tumorigenesis by preventing proliferation while at the same time exposing the damaged cells to a form of immune surveillance leading to their elimination.

Although the role of senescence in tumor suppression is now functionally established, its contribution to age-related disorders or other human pathologies is based on correlative data. However, our recent results show that senescence can act as a protective mechanism during tissue injury, in particular, by limiting the proliferation of activated stellate cells in response to acute injury and thus the associated fibrosis. Of note, tissue fibrosis contributes to a variety of pathologies beyond the liver, including those in the skin, lung, pancreas, kidney, and prostate. It therefore will be important to examine the role of senescence in other fibrotic conditions and wound-healing responses.

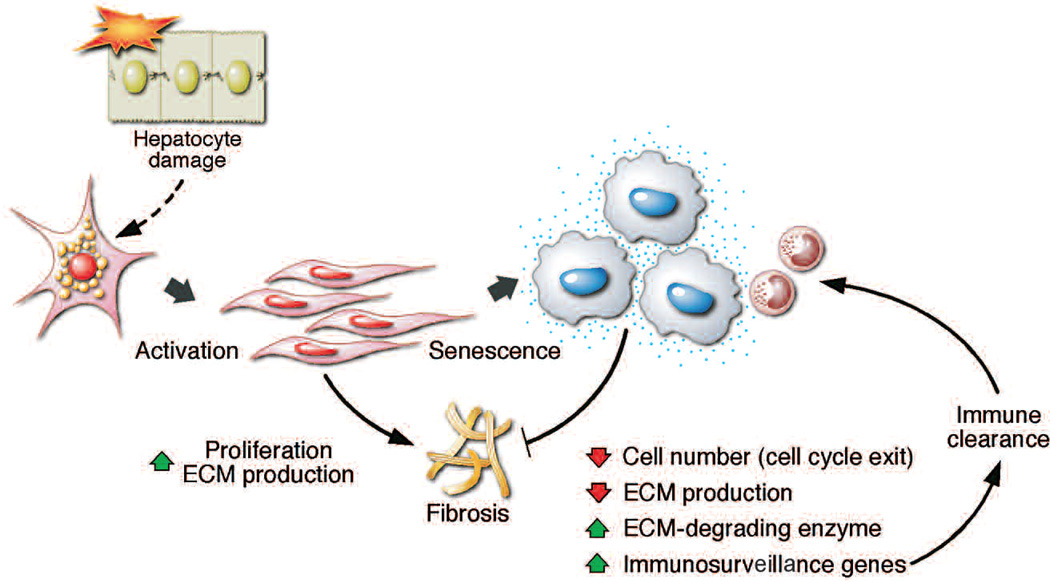

The potent cell cycle arrest that accompanies senescence is not the only mechanism by which the program limits fibrotic disease (Krizhanovsky et al. 2008). In addition, senescent cells decrease production of components of the ECM and up-regulate ECM degrading enzymes, thus decreasing the amount of deposited matrix. Moreover, senescent cells up-regulate a wide array of molecules that mediate interactions with the immune system that, in turn, may signal their subsequent elimination. Therefore, the senescence of activated stellate cells triggers a coordinated program that acts to inhibit the damage response by limiting the number of the cells and ECM production, on the one hand, and promoting tissue repair by signaling the elimination of senescence cells, on the other hand (Fig. 6).

Figure 6.

The eventual senescence of activated stellate cells limits fibrosis through a coordinated program involving cell cycle exit, down-regulation of ECM components, up-regulation of ECM-degrading enzymes, and enhanced immunosurveillance. (Reprinted, with permission, from Krizhanovsky et al. 2008 Supplemental Data [© Elsevier].)

Although our results suggest that senescence protects against liver fibrosis, in part, by stimulating clearance of these cells by the immune systems, it is noteworthy that chronic inflammation produced by viruses, alcohol abuse, or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis is a prerequisite for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in humans. Although the pro-inflammatory signals that accompany liver damage are undoubtedly complex and arise from various sources, the contribution of senescent activated stellate cells in recruiting immune cells, although initially beneficial, may ultimately contribute to chronic inflammation that stimulates the emergence of malignant hepatocytes and cancer progression. In fact, xenotransplant studies mixing normal and senescent cells suggest that senescent cells can stimulate the transformation of premalignant epithelial cells (Krtolica et al. 2001). Perhaps the role of senescence in limiting fibrosis evolved to protect the organism from acute tissue damage, but it can have a negative long-term role if the damage is chronic. It will be interesting to determine precisely how the senescence of mesenchymal cells involved in wound healing and fibrosis ultimately influences the initiation and progression of epithelial cancers.

ENDOGENOUS TRIGGERS OF SENESCENCE

In the context of tumor suppression, one of the key triggers of senescence is oncogene activation or other signals that produce a hyperproliferative response. The nature of this signal is the topic of much debate and likely involves activation of the INK4a/ARF locus as well as a DNA-damage response through signals produced by replication stress (Bartkova et al. 2006; Di Micco et al. 2006). One of the pathways that can lead to unrestricted proliferation and subsequent senescence in precancerous lesions is the PI3K pathway. Indeed, as presented here, hepatoblasts expressing hyperactive Akt—a key mediator of PI3K signaling—are prone to senescence in the presence of p53, and carcinomas induced by Akt and p53 loss undergo senescence when p53 signaling is restored.

In principle, such hyperproliferative signals might drive senescence of activated stellate cells in liver fibrosis. Specifically, it is well established that upon liver injury, damaged hepatocytes send signals that trigger the massive expansion of stellate cells that are normally quiescent in the intact liver (Bataller and Brenner 2005). Although distinct from the situation produced in benign tumors, where hyperproliferative signals are produced by mutation, such strong signaling might lead to replicative stress and ultimately provide a built-in brake in the expansion of these cells. How this activation occurs and whether it is the definite driver of senescence during liver fibrosis remain to be determined. Nevertheless, we see up-regulation of PI3K signaling in senescent stellate cells and have noted DNA-damage foci present in cells adjacent to the fibrotic scar (data not shown). Perhaps such signaling initially evolved to limit cell numbers during wound-healing responses and was co-opted as an anticancer mechanism later on.

EXPLOITING THE SENESCENCE-ASSOCIATED SECRETORY PHENOTYPE FOR SENESCENCE-MODULATING THERAPIES

It is now clear that the way in which senescence suppresses tumorigenesis or limits tissue damage extends beyond a cell-autonomous cell cycle arrest for which the program is best known. Hence, a non-cell-autonomous aspect of the program, the “senescence-associated secretory phenotype,” clearly has an important role in limiting the accumulation of cells in tissues. On the one hand, this program stimulates the immune system to target senescent cells, and our studies show that this targeting has a key role in tumor suppression and tissue fibrosis (Xue et al. 2007; Krizhanovsky et al. 2008). Moreover, to at least some degree, these secreted proteins modulate the cell cycle exit program itself in an autocrine manner (Acosta et al. 2008; Kuilman et al. 2008; Wajapeyee et al. 2008).

The fact that the accumulation of senescent cells in tissues can be modulated externally suggests therapeutic strategies to modulate senescence-associated pathologies. In principle, this could be accomplished by biological therapies that interact with cell surface receptors to activate or inhibit senescence or by a variety of immune modulating drugs. In addition to their obvious anticancer potential, such strategies might be eventually used to induce senescence in fibrogenic cells from one side and enhance clearance of the senescent cells by the immune system from the other side, leading to better treatments for fibrotic conditions and possibly other wound-healing disorders. As examples, systemic delivery of the senescence inducer IGFBP7 can suppress the progression of melanoma xenografts in mice, and administration of polyI:C (which stimulates the immune system) accelerates the resolution of fibrosis (Krizhanovsky et al. 2008; Wajapeyee et al. 2008). Nevertheless, the success of such therapeutic applications will require a deeper understanding of the tissue-specific relationships between senescence and the microenvironment.

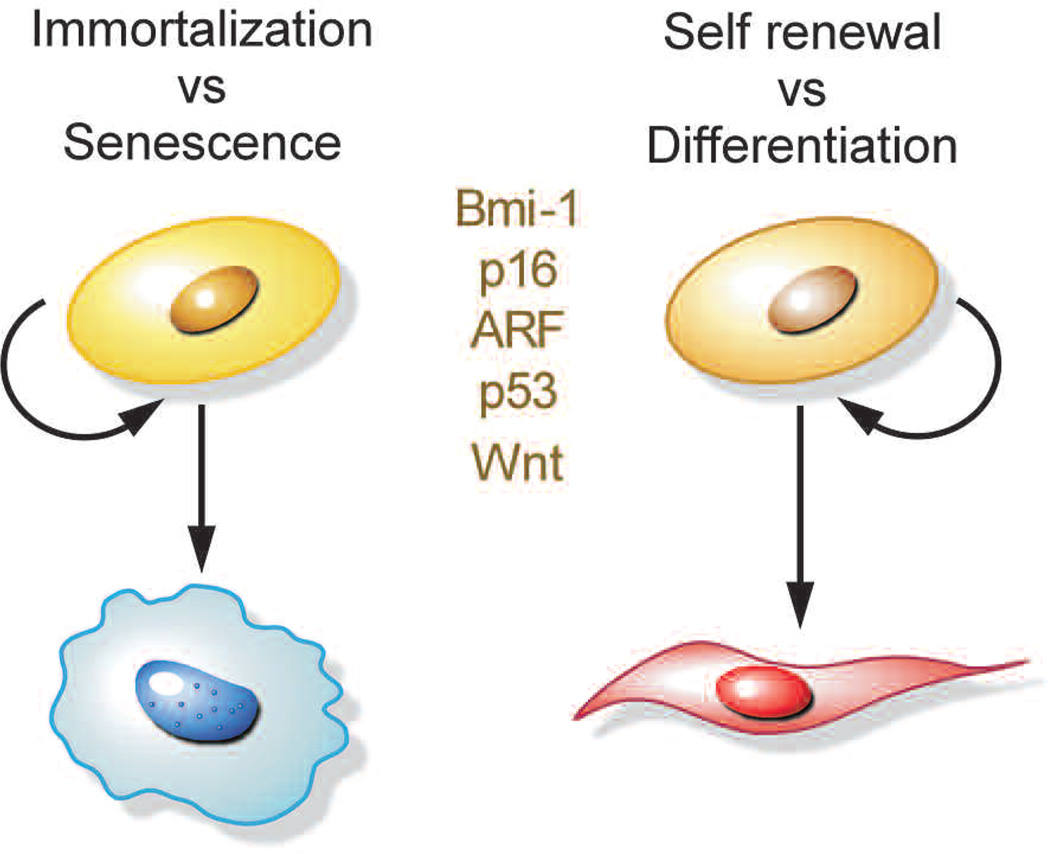

IMMORTALIZATION AND SELF-RENEWAL

Mutations that disable the senescence program—for example, loss of p53, Rb, and IGFBP7 or overexpression of Bmi-1 and CBX7—facilitate cellular immortalization and ultimately cancer development. In many ways, immortalization is similar to the process of cellular self-renewal, or the manner in which stem cells reproduce themselves, which is also a process of sustained cell division. It is striking that the normal process of stem cell self-renewal and the aberrant process of cellular immortalization share molecular pathways that have a central role in their regulation (Fig. 7). As discussed above, gene products of INK4a/ARF locus are established key elements in prevention of cell immortalization. Thus, p16/INK4a inhibits cyclin-dependent kinases 2 and 4, thereby preventing Rb phosphorylation and cell cycle progression. Both processes have been linked to self-renewal of stem cells in the hematopoietic and neuronal systems (Bruggeman et al. 2005; Molofsky et al. 2005), and in fact, p16 accumulates in certain stem cells with age and acts to limit self-renewal (Janzen et al. 2006; Krishnamurthy et al. 2006; Molofsky et al. 2006). Conversely, as discussed above, inactivation of the PTEN tumor suppressor can trigger senescence and limits the self-renewal of hematopoietic stem cells (Yilmaz et al. 2006).

Figure 7.

Molecular pathways driving cell fate decisions. Common regulators are illustrated.

Other convergent players that influence immortalization and self-renewal are the Polycomb proteins. In particular, the Polycomb repressor 2 complex protein Bmi-1 can promote cellular immortalization by suppressing the INK4a/ARF locus and appears to promote stem cell self-renewal in a variety of tissues (Bruggeman et al. 2005; Gil et al. 2005; Molofsky et al. 2005). Less understood are factors involved in Wnt signaling, which controls self-renewal and differentiation of stem cells from multiple origins (Reya and Clevers 2005) and can facilitate immortalization in primary melanocytes (Delmas et al. 2007). Thus, the critical cellular decision to proliferate is regulated by multiple pathways, which can positively affect self-renewal or enable bypass of senescence and facilitate cellular immortalization.

The overlaps between immortalization (or escape from senescence) and self-renewal (or suppression of differentiation) can be extended to the settings of HCC progression and liver fibrosis studied here. For example, although reactivation of p53 in HrasV12 and Akt-expressing tumors drives a cell cycle arrest program with many hallmarks of senescence, this program is accompanied by the appearance of differentiation markers (see Fig. 1) (Xue et al. 2007). Conversely, in liver fibrosis following an initially proliferative burst, activated stellate cells eventually senesce, which might be viewed as a state of terminal differentiation. Interestingly, quiescent HSCs were recently reported to have stem cell properties, sharing the ability to proliferate and differentiate into multiple cell lineages (Yang et al. 2008). These cells might serve as regional multipotent progenitors that are unable to self-renew but are able to differentiate into multiple lineages.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, the processes of senescence and immortalization, and differentiation and self-renewal, share overlapping signaling mechanisms and can be viewed as two sides of the same coin. What these similarities reveal, and the extent to which they apply to different contexts, remains to be determined. On the one hand, many of the processes currently linked to “self-renewal” have long been established to influence immortalization. As one example, there is much debate about the origin of cancer stem cells and how they acquire self-renewal capabilities; however, from the discussion above, it seems likely that in many cases, this reflects the process of immortalization studied for the last 30 years. Indeed, disruption of the ARF locus, well established to facilitate cellular immortalization, is sufficient to confer “cancer stem cell” properties to virtually all lymphoid cells expressing Bcr-Abl (Williams and Sherr 2008). On the other hand, these overlaps might have a deeper meaning, reflecting mechanisms that initially evolved to control cell numbers in normal tissues but were later incorporated into intrinsic tumor suppressive mechanisms to limit uncontrolled cell division. If this proves to be the case, it will be of interest to determine whether the self-renewal of stem cells is also influenced by autocrine and paracrine mechanisms that parallel those that influence differentiation. If so, such knowledge might stimulate the development of biological therapies to influence stem cell self-renewal and tissue regeneration.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank L. Dow and P. Smith for editorial advice, members of the Lowe laboratory for stimulating discussions, S. Hearn for electron microscopy, L. Chiriboga for immunohistochemistry, and J. Simon, K. Diggins-Lehet, L. Bianco, and the CSHL animal facility for help with animals. This work was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (V.K.) and grantAG16379 from the National Institutes of Health (S.W.L.). M.Y. is supported by a doctoral fellowship from the National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq). L.Z. is a Seligson Clinical Fellow. S.W.L. is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator.

REFERENCES

- Acosta JC, O’Loghlen A, Banito A, Guijarro MV, Augert A, Raguz S, Fumagalli M, Da Costa M, Brown C, Popov N, et al. Chemokine signaling via the CXCR2 receptor reinforces senescence. Cell. 2008;133:1006–1018. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartkova J, Rezaei N, Liontos M, Karakaidos P, Kletsas D, Issaeva N, Vassiliou LV, Kolettas E, Niforou K, Zoumpourlis VC, et al. Oncogene-induced senescence is part of the tumorigenesis barrier imposed by DNA damage checkpoints. Nature. 2006;444:633–637. doi: 10.1038/nature05268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bataller R, Brenner DA. Liver fibrosis. J. Clin. Invest. 2005;115:209–218. doi: 10.1172/JCI24282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beausejour CM, Krtolica A, Galimi F, Narita M, Lowe SW, Yaswen P, Campisi J. Reversal of human cellular senescence: Roles of the p53 and p16 pathways. EMBO. J. 2003;22:4212–4222. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braig M, Lee S, Loddenkemper C, Rudolph C, Peters AH, Schlegelberger B, Stein H, Dorken B, Jenuwein T, Schmitt CA. Oncogene-induced senescence as an initial barrier in lymphoma development. Nature. 2005;436:660–665. doi: 10.1038/nature03841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugge J, Hung MC, Mills GB. A new mutational AK Tivation in the PI3K pathway. Cancer Cell. 2007;12:104–107. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruggeman SW, Valk-Lingbeek ME, van der Stoop PP, Jacobs JJ, Kieboom K, Tanger E, Hulsman D, Leung C, Arsenijevic Y, Marino S, van Lohuizen M. Ink4a and Arf differentially affect cell proliferation and neural stem cell self-renewal in Bmi1-deficient mice. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1438–1443. doi: 10.1101/gad.1299305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi J, d’Adda di Fagagna F. Cellular senescence: When bad things happen to good cells. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2007;8:729–740. doi: 10.1038/nrm2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Trotman LC, Shaffer D, Lin HK, Dotan ZA, Niki M, Koutcher JA, Scher HI, Ludwig T, Gerald W, Cordon-Cardo C, Pandolfi PP. Crucial role of p53-dependent cellular senescence in suppression of Pten-deficient tumorigenesis. Nature. 2005;436:725–730. doi: 10.1038/nature03918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado M, Blasco MA, Serrano M. Cellular senescence in cancer and aging. Cell. 2007;130:223–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado M, Gil J, Efeyan A, Guerra C, Schuhmacher AJ, Barradas M, Benguria A, Zaballos A, Flores JM, Barbacid M, Beach D, Serrano M. Tumour biology: Senescence in premalignant tumours. Nature. 2005;436:642. doi: 10.1038/436642a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtois-Cox S, Genther Williams SM, Reczek EE, Johnson BW, McGillicuddy LT, Johannessen CM, Hollstein PE, MacCollin M, Cichowski K. A negative feedback signaling network underlies oncogene-induced senescence. Cancer Cell. 2006;10:459–472. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmas V, Beermann F, Martinozzi S, Carreira S, Ackermann J, Kumasaka M, Denat L, Goodall J, Luciani F, Viros A, et al. β-Catenin induces immortalization of melanocytes by suppressing p16INK4a expression and cooperates with N-Ras in melanoma development. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2923–2935. doi: 10.1101/gad.450107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Micco R, Fumagalli M, Cicalese A, Piccinin S, Gasparini P, Luise C, Schurra C, Garre M, Nuciforo PG, Bensimon A, et al. Oncogene-induced senescence is a DNA damage response triggered by DNA hyper-replication. Nature. 2006;444:638–642. doi: 10.1038/nature05327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickins RA, Hemann MT, Zilfou JT, Simpson DR, Ibarra I, Hannon GJ, Lowe SW. Probing tumor phenotypes using stable and regulated synthetic microRNA precursors. Nat. Genet. 2005;37:1289–1295. doi: 10.1038/ng1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsharkawy AM, Mann DA. Nuclear factor-κB and the hepatic inflammation-fibrosis-cancer axis. Hepatology. 2007;46:590–597. doi: 10.1002/hep.21802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil J, Bernard D, Peters G. Role of polycomb group proteins in stem cell self-renewal and cancer. DNA Cell Biol. 2005;24:117–125. doi: 10.1089/dna.2005.24.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ha L, Ichikawa T, Anver M, Dickins R, Lowe S, Sharpless NE, Krimpenfort P, Depinho RA, Bennett DC, Sviderskaya EV, Merlino G. ARF functions as a melanoma tumor suppressor by inducing p53-independent senescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2007;104:10968–10973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611638104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayflick L, Moorhead PS. The serial cultivation of human diploid cell strains. Exp. Cell Res. 1961;25:585–621. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(61)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, He X, Lowe SW, Hannon GJ. microRNAs join the p53 network—Another piece in the tumour-suppression puzzle. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2007a;7:819–822. doi: 10.1038/nrc2232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, He X, Lim LP, de Stanchina E, Xuan Z, Liang Y, Xue W, Zender L, Magnus J, Ridzon D, et al. A microRNA component of the p53 tumour suppressor network. Nature. 2007b;447:1130–1134. doi: 10.1038/nature05939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janzen V, Forkert R, Fleming HE, Saito Y, Waring MT, Dombkowski DM, Cheng T, DePinho RA, Sharpless NE, Scadden DT. Stem-cell ageing modified by the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p16INK4a. Nature. 2006;443:421–426. doi: 10.1038/nature05159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnamurthy J, Ramsey MR, Ligon KL, Torrice C, Koh A, Bonner-Weir S, Sharpless NE. p16INK4a induces an age-dependent decline in islet regenerative potential. Nature. 2006;443:453–457. doi: 10.1038/nature05092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krizhanovsky V, Yon M, Dickins RA, Hearn S, Simon J, Miething C, Yee H, Zender L, Lowe SW. Senescence of activated stellate cells limits liver fibrosis. Cell. 2008;134:657–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.06.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krtolica A, Parrinello S, Lockett S, Desprez PY, Campisi J. Senescent fibroblasts promote epithelial cell growth and tumorigenesis: A link between cancer and aging. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001;98:12072–12077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211053698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuilman T, Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LC, Douma S, van Doorn R, Desmet CJ, Aarden LA, Mooi WJ, Peeper DS. Oncogene-induced senescence relayed by an interleukin-dependent inflammatory network. Cell. 2008;133:1019–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazzerini Denchi E, Attwooll C, Pasini D, Helin K. Deregulated E2F activity induces hyperplasia and senescence-like features in the mouse pituitary gland. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:2660–2672. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.7.2660-2672.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin AW, Barradas M, Stone JC, Van Aelst L, Serrano M, Lowe SW. Premature senescence involving p53 and p16 is activated in response to constitutive MEK/MAPK mitogenic signaling. Genes Dev. 1998;12:3008–3019. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.19.3008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaloglou C, Vredeveld LC, Soengas MS, Denoyelle C, Kuilman T, van der Horst CM, Majoor DM, Shay JW, Mooi WJ, Peeper DS. BRAFE600-associated senescence-like cell cycle arrest of human naevi. Nature. 2005;436:720–724. doi: 10.1038/nature03890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molofsky AV, He S, Bydon M, Morrison SJ, Pardal R. Bmi-1 promotes neural stem cell self-renewal and neural development but not mouse growth and survival by repressing the p16Ink4a and p19Arf senescence pathways. Genes Dev. 2005;19:1432–1437. doi: 10.1101/gad.1299505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molofsky AV, Slutsky SG, Joseph NM, He S, Pardal R, Krishnamurthy J, Sharpless NE, Morrison SJ. Increasing p16INK4a expression decreases forebrain progenitors and neurogenesis during ageing. Nature. 2006;443:448–452. doi: 10.1038/nature05091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooi WJ, Peeper DS. Oncogene-induced cell senescence: Halting on the road to cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:1037–1046. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra062285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhanna N, Horani A, Doron S, Safadi R. Lymphocyte-hepatic stellate cell proximity suggests a direct interaction. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2007;148:338–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03353.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Lowe SW. Senescence comes of age. Nat. Med. 2005;11:920–922. doi: 10.1038/nm0905-920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Narita M, Krizhanovsky V, Nuñez S, Chicas A, Hearn SA, Myers MP, Lowe SW. A novel role for high-mobility group A proteins in cellular senescence and heterochromatin formation. Cell. 2006;126:503–514. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Nunez S, Heard E, Narita M, Lin AW, Hearn SA, Spector DL, Hannon GJ, Lowe SW. Rb-mediated heterochromatin formation and silencing of E2F target genes during cellular senescence. Cell. 2003;113:703–716. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00401-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NCHS (National Center for Health Statistics) National Vital Statistics Report. Hyattsville, Maryland: National Center for Health Statistics; 2004. Chronic liver disease/cirrhosis. [Google Scholar]

- Reya T, Clevers H. Wnt signalling in stem cells and cancer. Nature. 2005;434:843–850. doi: 10.1038/nature03319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roninson IB. Tumor cell senescence in cancer treatment. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2705–2715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi DJ, Jamieson CH, Weissman IL. Stem cells and the pathways to aging and cancer. Cell. 2008;132:681–696. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph KL, Chang S, Millard M, Schreiber-Agus N, DePinho RA. Inhibition of experimental liver cirrhosis in mice by telomerase gene delivery. Science. 2000;287:1253–1258. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5456.1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt CA, Fridman JS, Yang M, Lee S, Baranov E, Hoffman RM, Lowe SW. A senescence program controlled by p53 and p16INK4a contributes to the outcome of cancer therapy. Cell. 2002;109:335–346. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00734-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano M, Lin AW, McCurrach ME, Beach D, Lowe SW. Oncogenic ras provokes premature cell senescence associated with accumulation of p53 and p16INK4a. Cell. 1997;88:593–602. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81902-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shay JW, Roninson IB. Hallmarks of senescence in carcinogenesis and cancer therapy. Oncogene. 2004;23:2919–2933. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- te Poele RH, Okorokov AL, Jardine L, Cummings J, Joel SP. DNA damage is able to induce senescence in tumor cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1876–1883. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaziri H, West MD, Allsopp RC, Davison TS, Wu YS, Arrowsmith CH, Poirier GG, Benchimol S. ATM-dependent telomere loss in aging human diploid fibroblasts and DNA damage lead to the post-translational activation of p53 protein involving poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase. EMBO. J. 1997;16:6018–6033. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.19.6018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wajapeyee N, Serra RW, Zhu X, Mahalingam M, Green MR. Oncogenic BRAF induces senescence and apoptosis through pathways mediated by the secreted protein IGFBP7. Cell. 2008;132:363–374. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.12.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel HG, De Stanchina E, Fridman JS, Malina A, Ray S, Kogan S, Cordon-Cardo C, Pelletier J, Lowe SW. Survival signalling by Akt and eIF4E in oncogenesis and cancer therapy. Nature. 2004;428:332–337. doi: 10.1038/nature02369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RT, Sherr CJ. BCR-ABL and CDKN2A: A dropped connection. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008;8:563. doi: 10.1038/nrc2368-c1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue W, Zender L, Miething C, Dickins RA, Hernando E, Krizhanovsky V, Cordon-Cardo C, Lowe SW. Senescence and tumour clearance is triggered by p53 restoration in murine liver carcinomas. Nature. 2007;445:656–660. doi: 10.1038/nature05529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Jung Y, Omenetti A, Witek RP, Choi S, Vandongen HM, Huang J, Alpini GD, Diehl AM. Fate-mapping evidence that hepatic stellate cells are epithelial progenitors in adult mouse livers. Stem Cells. 2008;26:2104–2113. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2008-0115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz OH, Valdez R, Theisen BK, Guo W, Ferguson DO, Wu H, Morrison SJ. Pten dependence distinguishes haematopoietic stem cells from leukaemia-initiating cells. Nature. 2006;441:475–482. doi: 10.1038/nature04703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zender L, Spector MS, Xue W, Flemming P, Cordon-Cardo C, Silke J, Fan ST, Luk JM, Wigler M, Hannon GJ, et al. Identification and validation of oncogenes in liver cancer using an integrative oncogenomic approach. Cell. 2006;125:1253–1267. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]