Abstract

The target of rapamycin complex 2 (TORC2) is a key regulator of cell growth. Zinzalla et al. (2011) now provide evidence that TORC2 is activated by direct association with the ribosome, which may ensure that TORC2 activity is calibrated to match the cell’s intrinsic growth capacity.

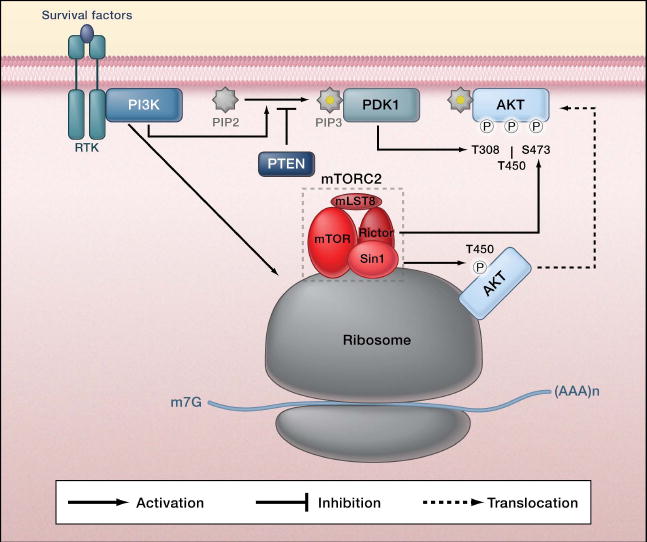

TOR is an atypical serine/threonine protein kinase conserved from yeast to mammals that forms two distinct physical and functional complexes, termed TORC1 and TORC2 (Figure 1) (Wullschleger et al., 2006). TORC1, a rapamycin sensitive complex, regulates translation, autophagy, cell growth, and cell size. In contrast, TORC2 is not directly inhibited by rapamycin and controls cell survival and morphology. The frequent dysregulation of mammalian TOR (mTOR) signaling observed in human cancer is thought to contribute to tumorigenesis (Zoncu et al. 2011). Extensive studies have revealed the molecular mechanisms of mTORC1 regulation in response to signals, such as growth factors, cellular energy status, nutrient availability and stress. Although compelling evidence has placed TORC2 downstream of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and upstream of the serine/threonine kinase AKT it has been unknown how TORC2 is regulated (Wullschleger et al., 2006) . Using a combination of elegant genetic screening and sophisticated biochemical studies, Zinzalla et al. (2011) significantly advance our understanding of TOR biology by identifying the ribosome as a missing link between PI3K and mTORC2 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Regulation of TORC2 by PI3K and ribosome association.

In response to upstream stimulation, increased phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling activates mTORC2 (consisting of mTOR, Rictor, Sin1, and mLST8) by promoting its association with ribosomes. mTORC2 phosphorylates the C-terminal turn motif (T450) and hydrophobic motif (S473) in AKT. AKT activation also requires phosphorylation of the activation loop (T308) by PDK1. Notably, phosphorylation of the turn motif of AKT is constitutive and co-translational, whereas phosphorylation of the hydrophobic motif is highly dependent on PI3K signaling and post-translational. TORC2 similarly phosphorylates the turn motif and hydrophobic motif in SGK and conventional protein kinase C (Garcia-Martinez and Alessi, 2008; Jacinto et al., 2004; Sarbassov et al., 2005).

In yeast, TORC2 phosphorylates and activates YPK2, the ortholog of mammalian kinase SGK1, a known substrate of mammalian TORC2. Loss of TORC2 function is lethal in yeast; however, overexpression of a constitutively active YPK2 suppresses the lethality caused by a loss of function TORC2 mutation (Kamada et al., 2005). Zinzalla et al. designed a clever reverse suppressor screen in search of yeast mutants that require the expression of constitutively active YPK2 for survival. This strategy was aimed at uncovering mutations in TORC2 upstream activators. Perhaps not surprisingly, many mutations isolated were found in genes encoding components of TORC2. Interestingly, the only non-TORC2 component isolated was NIP7, which encodes a protein involved in the maturation of rRNA and ribosome biogenesis. Survival of NIP7 mutant yeast requires overexpression of the constitutively active YPK2. Many scientists would abstain from studying ribosomal proteins because their inactivation may disrupt protein translation and lead to pleiotropic effects. Undeterred, Hall and colleagues investigated further, eventually discovering an exciting biochemical mechanism linking the ribosome to TORC2 activation.

The genetic studies not only confirm a role for NIP7 in TORC2 activation, but also show that ribosomal proteins are important for TORC2 function in yeast. Mutation of NIP7 mimics the TORC2 loss of function phenotypes, indicating a strong functional relationship between these two genes. The authors further extended their study to mammalian cells and show that mammalian NIP7 (mNIP7) and ribosome assembly are important for mTORC2 activation. Knockdown of mNIP7 reduces mTORC2 activity as indicated by a decrease in the phosphorylation of mTORC2 substrates. Moreover, knockdown of either Rpl7 (a subunit of the 60S ribosome) or Rps16 (a subunit of the 40S ribosome) inactivate mTORC2, demonstrating the importance of ribosome in mTORC2 activation. Inhibition of protein translation had no effect on mTORC2 activation, supporting the notion that mTORC2 is activated by the ribosome but not translation. Additionally, extensive biochemical studies demonstrate that mTORC2 can associate with the ribosome, and the ribosomal-associated mTORC2 displays kinase activity towards AKT in vitro. It appears that the mTORC2 components, rictor and/or sin1, which are not found in TORC1, interact with the 60S subunit of ribosome.

Importantly, the authors link this association with known upstream regulators of TORC2, demonstrating that the interaction between ribosome and TORC2 is strongly enhanced by insulin stimulation. Inhibition of PI3K activity blocks the interaction between the ribosome and mTORC2, as well as inhibits mTORC2 activation in response to insulin. Complementary activation of PI3K by knockdown of PTEN— a tumor suppressor lipid phosphatase that counters PI3K signaling— increases the interaction between mTORC2 and ribosome, demonstrating the necessary and sufficient role of PI3K in regulating the mTORC2-ribosomal association and thus mTORC2 activation. The role of PI3K in promoting the interaction of mTORC2 and ribosome was further validated in multiple cancer cell lines with high PI3K signaling. Collectively, the study by Zinzalla et al. has convincingly demonstrated that the PI3K-dependent mTORC2-ribosome interaction plays a major role in TORC2 activation. Interestingly, Oh et al. (2010) have also recently reported the association of mTORC2 with the ribosome and propose that the ribosomal association is important for the co-translational phosphorylation of the AKT turn motif.

The findings of Zinzalla et al. raise many interesting questions. How is the interaction between mTORC2 and the ribosome regulated? There may be intermediate players between PI3K and the TORC2-ribosome interaction. For example, phosphorylation of rictor may play a role (Dibble et al., 2009; Treins et al. 2010). Is the interaction between TORC2 and the ribosome regulated in yeast and if so, by what signals? The TORC2-ribosome interaction is conserved from yeast to mammals; however, there is no evidence that yeast TORC2 is activated in a PI3K-dependent manner as in mammalian cells.

How could mTORC2 be responsible for phosphorylating two different sites on the same protein with drastically different manners of regulation? mTORC2 phosphorylates both the hydrophobic motif and the turn motif of AKT. Notably, phosphorylation of the hydrophobic motif is post-translational and induced in a PI3K-dependent manner, whereas phosphorylation of the turn motif is co-translational and constitutive (Oh et al. 2010). Ribosomal association may explain the constitutive and co-translational phosphorylation of the turn motif in AKT (Figure 1). Membrane association has been suggested to be important for AKT hydrophobic motif phosphorylation. Does this imply there are two different pools of mTORC2?

What is the exact role of the ribosome in mTORC2 activation? Does ribosome binding regulate mTORC2 function by affecting localization, contributing to activation, or maintaining an active mTORC2 kinase?

Lastly, why the ribosome? As pointed out by Zinzalla et al. ribosome content reflects the cell’s potential for growth. Therefore, a mechanism that involves the ribosome may ensure that TORC2 activation is tightly linked with the cell’s ability to respond to growth signals. In addition, given that TORC1 regulates ribosome biogenesis, this study suggests a possible interplay between the two TORC complexes, in which TORC2 modulates TORC1 by activating AKT and TORC1 affects TORC2 by increasing ribosomal biogenesis and S6K-mediated feedback inhibition. Future studies are needed to address these important questions and possible new roles of the ribosome in cellular signaling, especially in the regulation of cell growth.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Dibble CC, Asara JM, Manning BD. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:5657–5670. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00735-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Martinez JM, Alessi DR. Biochem J. 2008;416:375–385. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacinto E, Loewith R, Schmidt A, Lin S, Ruegg MA, Hall A, Hall MN. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1122–1128. doi: 10.1038/ncb1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamada Y, Fujioka Y, Suzuki NN, Inagaki F, Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN, Ohsumi Y. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:7239–7248. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.16.7239-7248.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh WJ, Wu CC, Kim SJ, Facchinetti V, Julien LA, Finlan M, Roux PP, Su B, Jacinto E. EMBO J. 2010;29:3939–3951. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2010.271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarbassov DD, Guertin DA, Ali SM, Sabatini DM. Science. 2005;307:1098–1101. doi: 10.1126/science.1106148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treins C, Warne PH, Magnuson MA, Pende M, Downward J. Oncogene. 2010;29:1003–1016. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wullschleger S, Loewith R, Hall MN. Cell. 2006;124:471–484. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinzalla V, Stracka D, Oppliger W, Hall M. Cell. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.014. this issue. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoncu R, Efeyan A, Sabatini DM. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2011;12:21–35. doi: 10.1038/nrm3025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]