Background: Hippo plays critical roles in organ size control, and the regulation of its activity remains poorly characterized.

Results: N-terminal dimerization of Hpo is critical for Hippo kinase activity. The Hippo C-terminal half promotes cytoplasmic localization and activity of Hippo.

Conclusion: Dimerization and nucleocytoplasmic translocation of Hippo are crucial for its biological function.

Significance: Dimerization and cytoplasmic localization regulate Hippo activity.

Keywords: Development, Drosophila, phosphorylation, Signaling, Tumor suppressor gene, Dimerization, Hippo, Kinase, nucleocytoplasmic translocation

Abstract

The Hippo (Hpo) signaling pathway controls organ size by regulating the balance between cell proliferation and apoptosis. Although the Hpo function is conserved, little is known about the mechanism of how its kinase activity is regulated. Based on structural information, we performed mutation-function analysis and provided in vitro and in vivo evidence that Hpo activation requires proper dimerization of its N-terminal kinase domain as well as the C-terminal SARAH domain. Hpo carrying point mutation M242E can still dimerize, yet the dimers formed between intermolecular kinase domains were altered in conformation. As a result, autophosphorylation of Hpo at Thr-195 was blocked, and its kinase activity was abolished. In contrast, Hpo carrying I634D, a single mutation introduced in the Hpo C-terminal SARAH domain, disrupted the dimerization of the SARAH domain, leading to reduced Hippo activity. We also find that the Hpo C-terminal half contains two nuclear export signals that promote cytoplasmic localization and activity of Hpo. Taken together, our results suggest that dimerization and nucleocytoplasmic translocation of Hpo are crucial for its biological function and indicate that a proper dimer conformation of the kinase domain is essential for Hpo autophosphorylation and kinase activity.

Introduction

Restriction of tissue growth is an important means by which the developmental program generates an organism of a defined size and form (1). Studies in the last decade have unveiled a critical role for the evolutionarily conserved Hpo signaling pathway in restricting tissue growth by controlling cell proliferation and death (2–5). Recent studies in Drosophila and mammals have demonstrated links between the Hpo signaling network and other established signaling cascades, such as Wnt/wingless, Hedgehog, BMP/dpp, and Jun kinase (6–10), suggesting that the Hpo pathway acts via cell-autonomous or non-cell-autonomous mechanisms in various physiological contexts during animal development (11–13). Furthermore, aberrant signaling of the Hpo pathway is also linked to a range of diseases, most notably cancer (14).

Initially discovered by genetic screens in Drosophila for tumor suppressor genes, the core Hpo pathway comprises a kinase cascade: the serine/threonine Ste20-like kinase Hpo, the nuclear Dbf2-related (NDR) family protein kinase Warts (Wts), the WW domain scaffolding protein Salvador (Sav), and Mob-as-tumor-suppressor (Mats). Together with Sav, activated Hpo phosphorylates the Wts-Mats kinase complex (15–20), which triggers the kinase phosphorylation cascade and inhibits the transcriptional activity of the downstream transcription complex: scalloped (Sd), a TEAD/TEF family of transcription factors, and the coactivator Yorkie (Yki) (21–24). The Yki-Sd transcription complex regulates the expression of a group of genes that participate in cell proliferation, survival, cell-cell interaction, and also maintain the steady-state of cell signaling strength (14). The Hpo pathway coordinates cell proliferation and death by controlling the transcription of key regulatory molecules in cell cycle control and apoptosis, such as diap1 and dmyc, respectively (23–25).

The Hpo pathway is evolutionarily conserved, although this pathway is more complex in mammals (2, 14, 26). Mammalian Mst1 and Mst2, which belong to the germinal center kinase subfamily (GCKII), are closely related to Drosophila Hpo, sharing 76% sequence identity (27). Both kinases have an N-terminal catalytic domain and a C-terminal coiled coil interaction motif called the SARAH (for Sav/Rassf/Hpo) domain that mediates self-association as well as association with other SARAH domain-containing proteins (28, 29). Recent studies have demonstrated that Mst1/2 play critical roles in organ size control and cancer formation (30–32) and induce apoptosis after stimulation of cell death (33). Although Mst1/2 have been shown to play vital roles, their activation, which includes caspase-dependent cleavage, binding, and autophosphorylation, is poorly understood (34–37). Recent studies have shown that the pleckstrin homology domain leucine-rich repeat protein phosphatases bind Mst1 and activate Mst1 kinase activity (38).

A number of molecules have been identified to act upstream of Hpo, including the atypical cadherin Fat (Ft) (39–43), the FERM proteins Expanded (Ex), Merlin (Mer) and the newly found Kibra (41, 44–50). How these molecules regulate Hpo activity remains unknown. Nonetheless, negative regulation of Hpo activity has been shown recently. For example, the Drosophila RASSF ortholog (dRASSF)3 blocks Hpo kinase activity by competing with Sav for binding (51). Moreover, protein phosphatase 2 complex, identified as a negative regulator of Hpo signaling complex, is recruited to dRASSF and thus prevents Hpo activation during development (52).

Based on three-dimensional structural analysis, human Mst1 was shown to homodimerize through the C-terminal SARAH domain (28), via an antiparallel conformation (53). These findings suggest that the Mst1 kinase activity may be regulated by homodimerization as well as heterodimerization with members of the RASSF tumor suppressor family.

In this study, we demonstrate that both the N-terminal kinase domain and the C-terminal SARAH domain of Drosophila Hpo dimerize. Importantly, we showed that the N-terminal dimerization is critical for the intermolecular autophosphorylation of Hpo and its kinase activity, whereas disruption of the dimerization via the SARAH domain has no significant impact on kinase activity. We also identified a novel dimeric interface that is essential for the kinase activity by maintaining the proper homodimerization between kinase domains. Furthermore, we showed that the Hpo activity is regulated by its nucleocytoplasmic translocation.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mutants, Transgenes, and Drosophila Genetics

Hpo point mutations were generated by PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis and verified by DNA sequencing, and all of these cDNA fragments were cloned into the pUAST vector. To construct attB-UAS-FLAG-Hpo wild type and mutant forms, a pUAST vector with attB sequence inserted upstream of the UAS-binding sites was used. The vas-phi-Zh2A-VK5 (75B1) flies were used to generate Hpo transformants inserted at the 75B1 attP locus (54). Animals were cultured at 25 °C for adult analysis. hpoBF33 is a null allele (16). Other transgenes and alleles were driven using GMR-Gal4 and MS1096-Gal4. The mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM) analysis was done as described by Lee and Luo (55). The genotypes for generating hpo clones expressing Hpo variants were ey-FLP/+, FRT42D hpoBF33/FRT42D tub-Gal80, and UAS-FLAG-Hpo-variants/tub-Gal4 UAS-GFP.

Cell Culture, Transfection, Immunoprecipitation, and Western Blot Analysis

S2 cells were cultured in Drosophila Schneider's medium (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 mg/ml streptomycin. Plasmid transfection was carried out using Lipofectamine according to the manufacturer's instructions. A ubiquitin-Gal4 construct was co-transfected with the pUAST expression vector for all of the transfection experiments. Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analyses were performed according to standard protocols as described previously (24). To detect phosphorylated Hpo mutants in SDS-PAGE, Phos-Tag AAL-107 (FMS Laboratory) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. The Phos-Tag is a phosphate binding compound that, when incorporated into polyacrylamide gels, can result in an exaggerated mobility shift for phosphorylated proteins, dependent upon the degree of phosphorylation (56). S2 cells were treated with leptomycin B (LMB; Calbiochem) at 10 ng/ml for 2 h. Antibodies used in this study were as follows: rabbit anti-phospho-Mst1/Mst2/Hpo (Thr-183 of Mst1, Thr-180 of Mst2, Thr-195 of Hpo) antibody (Cell Signaling Technology), mouse anti-FLAG (Sigma), and mouse anti-Myc (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, CA).

Cell Fractionation

S2 cells were washed three times with chilled phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and resuspended in 5 volumes of fresh ice-cold hypotonic cell lysis buffer (10 mm Hepes (pH 7.90), 1.5 mm MgCl2, 10 mm KCl) supplemented just before use with 0.5 mm DTT and mixture (Sigma). After incubation on ice for 10 min, the swollen cells were Dounce homogenized until all cells were visibly lysed. The resulting lysate was centrifuged at 4 °C for 7 min at 1,000 × g. The supernatant (combined cytoplasmic and membrane fractions) was removed. The pelleted nuclei were recentrifuged at 4 °C at 20,000 × g for 20 min to further remove contaminating cytoplasmic and membrane proteins.

Luciferase Assay

Cells were cultured in 24-well plates and co-transfected with 15 ng of the copia-Renilla luciferase reporter as a normalization control and 300 ng of 3×Sd2-Luc firefly luciferase reporter (24) using Lipofectamine. Cells were incubated for 48 h after transfection, and then the Dual-Luciferase measurements were performed in triplicate using the Dual-GloTM luciferase assay system (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. To induce Hpo dimerization in the S2 cell, the ARGENTTM regulated homodimerization kit was used.

Immunostaining

Immunostaining of imaginal discs and S2 cells was carried out as described (24). Primary antibodies used in this work include mouse anti-FLAG (Sigma), mouse anti-Myc (Sigma), mouse anti-HA (Sigma), rabbit anti-Hpo (produced by immunizing rabbits with the peptide of Hpo amino acids 352–670), and mouse anti-GFP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc.).

Glutathione S-Transferase (GST) Fusion Protein Pull-down Assay

GST fusion proteins were produced in Escherichia coli and purified with glutathione-agarose beads. GST fusion protein-loaded beads were incubated with recombinant kinases or cell lysates derived from S2 cells expressing individual kinases at 4 °C for 1.5 h. After the beads were washed three times with lysis buffer, Western blot analysis was performed with antibodies against tags.

In Vitro Kinase Assay

Cell extracts were prepared from S2 cells and immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody (Sigma) to obtain FLAG-Hpo mutants. The kinase (Hpo mutants) and substrates (GST-Mats) were incubated in kinase assay buffer (50 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 60 mm potassium acetate, 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT, 10 μm ATP along with 10 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP) for 30 min at 30 °C. Reactions were stopped by the addition of SDS sample buffer. Then samples were boiled for 5 min at 100 °C followed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography.

Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET) Analysis

For FRET analysis, cyan fluorescent protein (CFP)- and yellow fluorescent protein (YFP)-tagged constructs were transfected into S2 cells together with an ubi-Gal4 expression vector. Cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 20 min, and mounted on slides in 80% glycerol. Fluorescence signals were acquired with the ×63 objective of a Leica LAS SP5 confocal microscope. Each data set was based on 10–15 individual cells. In each cell, three to four regions of interest in photobleached area were selected for analysis. The intensity change of CFP was analyzed using the Leica software. The efficiency of FRET was calculated using the formula, FRET% = ((CFPAP − CFPBP)/CFPAP) × 100.

RESULTS

C Terminus of Hpo Forms Homodimers through Antiparallel Dimerization

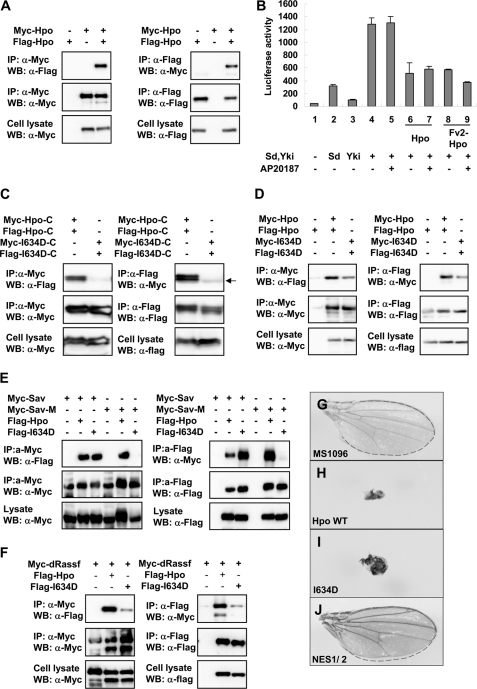

To identify new Hpo partners, we carried out a yeast two-hybrid screen for Hpo-binding proteins using the noncatalytic C terminus of Hpo (residues 605–669). Interestingly, one clone isolated from the screen contained the same Hpo C-terminal region (residues 579–669). Based on this result and the evidence that the last 60 amino acids of C-terminal SARAH domain are well conserved between Drosophila Hpo and Mst1/2 (20), we hypothesized that Hpo forms dimers through its putative C-terminal SARAH domain like Mst1/2 (53). To test this, we transfected S2 cells with FLAG- and Myc-tagged full-length Hpo. It has been found that differently tagged full-length Hpo co-immunoprecipitated with each other (Fig. 1A). We then tested whether this self-interaction affects Hpo activity via induction of homodimerization of full-length Hpo (Hpofl) using the ARGENTTM regulated homodimerization kit (57, 58). We generated Hpofl with two FKBP (Fv2) domains, which are used to induce formation of homodimer or multimer when small FKBP ligands AP20187 are present. In S2 cells, co-expression of Yki and Sd synergistically activates the luciferase (Luc) reporter gene (3×Sd2-Luc) (24), which is significantly suppressed by the co-expression of wild type Hpo or Fv2-Hpo (Fig. 1B, lanes 6 and 8). Inhibition by Fv2-Hpo but not by the wild type Hpo was enhanced by the addition of the ligand AP20187 (Fig. 1B, compare lanes 8 and 9 with lanes 6 and 7). This piece of evidence indicates that the induction of Hpo homodimer promotes its pathway activity.

FIGURE 1.

Homo- and heterotypic interactions of the Hpo SARAH domain. A, FLAG-Hpo and Myc-Hpo coimmunoprecipitated with each other. The indicated constructs were transfected into S2 cells. FLAG- or Myc-Hpo was immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG or anti-Myc antibody. Western blots (WB) were done to detect specific proteins as indicated to the left of each panel. B, S2 cells were transfected with the indicated Hpo or Fv2-Hpo constructs together with Sd, Yki, and the 3×Sd2-Luc reporter gene, and the cell lysates were subjected to a Dual-Luciferase assay. Error bars, S.D. (triplicate wells). C, differently tagged Hpo-I634D-C (amino acids 343–670) cannot interact with each other because I634D has broken the C-terminal SARAH dimeric domain. The arrow indicates IgG bands. D, differently tagged full-length HpoI634D had weak binding. E, Myc-tagged Sav or Sav-M was co-expressed with FLAG-tagged Hpo or HpoI634D in S2 cells. Sav-M, SavL563P mutant. Both wild type and HpoI634D bind with Myc-Sav, but Sav-M failed to interact with HpoI634D. F, Myc-tagged dRASSF was co-expressed with FLAG-tagged Hpo or HpoI634D in S2 cells. G–J, wild type female wings (G) or female wings expressing wild type Hpo (H), Hpo mutant I634D (I), or mutant NES1/2 (J) with MS1096.

To investigate whether Hpo activity is regulated by the homodimerization through its C-terminal SARAH domain, we generated point mutations to specifically disrupt dimerization mediated by the SARAH domain. Based on the solution structure of human Mst1 C terminus (Protein Data Bank entry 2JO8) (53), we modeled the structure of the Hpo C-terminal SARAH domain (supplemental Fig. S1A). In agreement with the structure information, we found a critical isoleucine (Ile-634) residue that is essential for Hpo homodimerization. Mutation of this residue to an aspartic acid, I634D, is predicted to disrupt the coiled coil-mediated dimerization. As shown in the co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments, similar to full-length Hpo, the C-terminal Hpo containing the SARAH domain (amino acids 343–670) forms homodimers, whereas the same region of Hpo carrying the I634D mutation, Hpo-CI634D, completely failed to do so (Fig. 1C). However, full-length Hpo with the I634D mutation, HpoI634D, retains a weak but significant homodimerization capability (Fig. 1D), suggesting that regions other than the SARAH domain also contribute to the homodimerization of Hpo.

The I634D mutation is located within the Sav-binding region of Hpo (amino acids 602–669) (18). Thus, we tested the interaction between HpoI634D and Sav. Co-IP results showed that HpoI634D binds wild type Sav (Fig. 1E). However, when the Sav SARAH domain mutant SavL563P (Sav-M), in which the critical leucine residue was mutated to a proline based on modeled structure of SARAH domain, was used in the co-IP experiment, an interaction between Sav-M and HpoI634D was not detected (Fig. 1E). It is known that dRASSF restricts Hpo activity by competing with Sav for binding to Hpo (51). We tested whether the I634D mutation affects the binding between dRASSF and Hpo. As shown in Fig. 1F, the I634D mutation reduced the interaction between Hpo and dRASSF.

To directly compare the activity of HpoI634D with wild type Hpo, we generated transformants using the phiC31 integration system to ensure that all of the transgenes were expressed from the same chromosomal location (attp at 75B1) so that position effects on gene expression were eliminated (54). When the transformants were expressed by the wing-specific Gal4 driver MS1096, a similar, albeit weaker, Hpo activity was detected in HpoI634D transgenic flies compared with the Hpo wild type flies in the context of the reduction in wing size (Fig. 1, G–I). Taken together, these results indicate that the dimerization of Hpo mediated by the C-terminal SARAH domain modulates its activity, and disruption of SARAH-mediated dimerization compromises interactions with Sav and dRASSF but does not abolish the activity of Hpo.

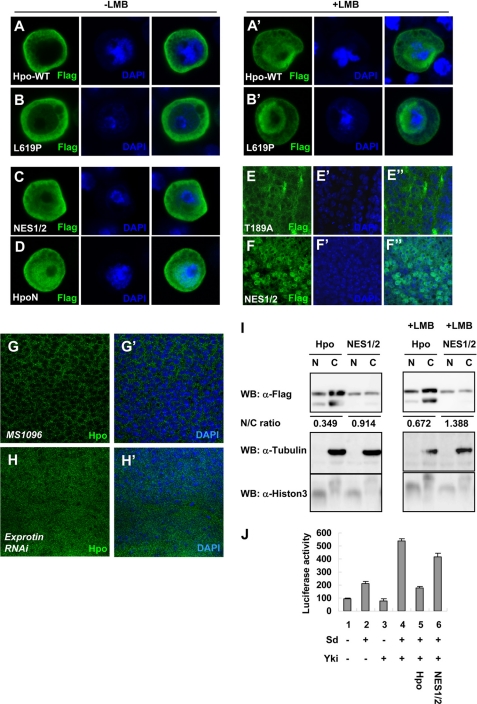

Two Nuclear Export Signals (NESs) within Hpo C Terminus Are Important for Biological Function of Hpo

The Hpo kinase cascade promotes Yki cytoplasmic accumulation during growth regulation, and the overexpressed Hpo was detected mainly in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2A). In S2 cells, transfection of HpoL619P, a mutant incapable of forming a SARAH domain dimer based on our prediction from the modeled structure (supplemental Fig. S1A), resulted in the increased nuclear localization of HpoL619P compared with the wild type Hpo (Fig. 2, compare B with A). No evidence of Hpo nuclear-cytoplasmic translocation has been shown before; thus, we treated the cells with LMB, a specific inhibitor of nuclear export mediated by leucine-rich NES (59), to examine whether the nucleus-cytoplasm shuttling of Hpo is regulated by the nuclear export pathway. The leucine-rich NES is a highly conserved sequence used by a variety of proteins to facilitate their export from the nucleus to the cytoplasm, and is important in regulating protein function by affecting proteins' subcellular localization (60). After 2 h of LMB treatment, as shown in Fig. 2, A′ and B′, the wild type Hpo accumulated in the nucleus, whereas the nuclear accumulation of HpoL619P was more predominant. These results indicate that a functional NES(s) exists within the Hpo C-terminal SARAH domain. Sequence analysis of Hpo reveals that Hpo contains two potential leucine-rich NES-like sequences (NES1, amino acids 425–434; NES2, amino acids 610–619), and the L619P mutation lies within the NES2 region (Fig. 3C). We mutated the hydrophobic residues to an alanine or a proline (L429A, I434A, and L619P) in both NES1/NES2 regions and investigated the subcellular localization of the mutant forms. HpoNES1/2 was distributed throughout the cytoplasm and nucleus (Fig. 2C). To confirm the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of Hpo, S2 cells were transfected with the wild type Hpo or HpoNES1/2. Cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions from the cell extracts were collected. Western analysis revealed that the wild type Hpo was found primarily in the cytoplasmic fraction, and the HpoNES1/2 was equally distributed in both fractions (Fig. 2I). Treatment with LMB promotes the accumulation of the wild type Hpo in the nucleus (Fig. 2I). These results suggest that both NES sequences are functional.

FIGURE 2.

Hpo C terminus contains two functional NESs. A–B′, S2 cells were transfected with the wild type Hpo or HpoL619P mutant and stained with anti-FLAG antibody. For LMB treatment of S2 cells, LMB was added at a concentration of 10 ng/ml for 2 h before harvest. Nuclei are labeled by DAPI (blue). C and D, the HpoNES1/2 mutant or Hpo-N was expressed in S2 cells without LMB treatment. E and F, high magnification view of wing discs expressing FLAG-tagged Hpo-T189A or NES1/2 using MS1096, which were immunostained with an anti-FLAG (green) antibody. G–H′, high magnification view of wild type wing discs (G and G′) or wing discs expressing UAS-exportin RNAi (H and H′) using MS1096, which were immunostained with anti-Hpo antibody to show the endogenous Hpo protein (green) and DAPI (blue) to label the nuclei. I, nuclear (N) and cytoplasmic (C) fractions of S2 cells expression Hpo or HpoNES1/2 in the absence or presence of LMB (10 ng/ml, 2 h) were analyzed by Western blot (WB) using FLAG antibody. The integrated optical density ratios of Hpo protein level in nucleus and cytosol (N/C) are shown below each blot. J, 3×Sd2-Luc reporter assay was performed by expressing wild type Hpo or HpoNES1/2 in S2 cells.

FIGURE 3.

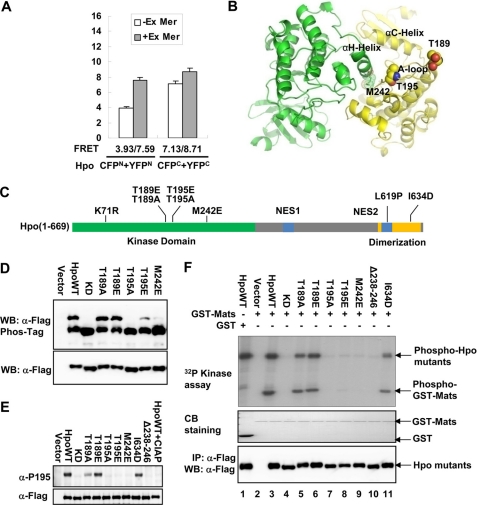

Homodimerization of Hpo kinase domain is critical for its autophosphorylation and kinase activity. A, S2 cells were cotransfected with indicated N-terminal or C-terminal CFP/YFP-tagged Hpo constructs, treated with or without upstream components Ex and Mer. N-terminal of Hpo tagged with CFP and YFP showed higher FRET changes than C-terminal tagged ones. B, modeled structure of Drosophila Hpo kinase domain. The crystal structure of the Mst1 kinase domain (Protein Data Bank entry 3CM) was used as a template during comparative modeling in the program Modeler. The Hpo kinase domain forms a homodimer through hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions. Residues of particular interest have been labeled and highlighted, respectively, in dotted models for hydrophobic core packing on the dimeric interface and in sphere models for phosphorylation sites. C, schematic representation of Hpo kinase. The K71R mutation that is used to generate kinase-dead Hpo is marked. The N-terminal kinase domain and the C-terminal dimerization domain of Hpo are colored green and orange, respectively. The phosphorylation sites (Thr-195; T195) and the Hpo N- and C-terminal critical dimerization sites (Met-242 (M242) and I634D) investigated in this study are marked. The NES regions are colored blue. D, Western blots (anti-FLAG) of IP samples or lysates transfected to express FLAG-Hpo mutants in S2 cells. The upper panel shows Phos-Tag gel (50 μm Phos-Tag); the lower panel shows 8% SDS gel. Phosphorylation results in mobility shifts proportional to the extent of phosphorylation. Note that Thr-195 is the important autophosphorylation site of Hpo. E, Western blots (anti-phospho-Mst1-Thr-183) of IP samples to detect the phosphorylation level of the Hpo Thr-195 site. The lower panel shows IP sample loading control. F, Hpo variants phosphorylate Mats in vitro. FLAG-tagged Hpo variants were immunoprecipitated from S2 cells and tested for kinase activity against GST-Mats (63). Hpo autophosphorylation and Mats phosphorylation by Hpo or Hpo variants are shown in the top panel. The substrate and input kinase are also shown by Coomassie Blue staining (CB) and Western blot (WB) (bottom two panels).

In Drosophila, HpoNES1/2 overexpressed by MS1096-Gal4 in wing discs exhibited enhanced nuclear accumulation when compared with the overexpressed HpoT189A mutant (described below), which showed a staining pattern similar to that of the wild type Hpo (Fig. 2, E and F). We further checked the localization of endogenous Hpo when the RNAi transgene for exportin (dCRM1) was overexpressed. Exportin knockdown by RNAi resulted in nuclear accumulation of endogenous Hpo (Fig. 2, compare H with G).

Next, we examined the functional activity of HpoNES1/2 by luciferase assay using S2 cells. Coexpression of HpoNES1/2 together with Sd and Yki caused a slight decrease in luciferase reporter activity in contrast to the dramatic response elicited by the wild type Hpo (Fig. 2J). Expression of HpoNES1/2 in Drosophila wing discs resulted in a similar phenotype to the MS1096 control (Fig. 1J′ and supplemental Fig. S1B), which suggested that Hpo in the nucleus lost most of its signaling activity, and the regulation of Hpo localization is important for its biological function. Taken together, the C-terminal SARAH domain regulates the Hpo activity via its dimerization and modulation on Hpo nucleocytoplasmic translocation.

N-terminal Homodimerization of Hpo Is Critical for Its Kinase Activity and Biological Function

Because full-length HpoI634D still dimerizes to a certain degree, we speculated that the N-terminal kinase domain also contributes to the homodimerization of Hpo. To further investigate this, we employed the FRET assay, which measures the transfer of energy between YFP and CFP to detect protein-protein interaction (61). Two pairs of fusion proteins with CFP/YFP either fused to the N terminus (CFPN-Hpo/YFPN-Hpo) or to the C terminus (Hpo-CFPC/Hpo-YFPC) of the wild type Hpo were generated to examine the interactions of the N or the C terminus by performing FRET analysis in S2 cells. We observed significant FRET between CFPN-Hpo and YFPN-Hpo (∼3.93%), which was further increased (∼7.59%) when upstream regulators of Hpo, Ex and Mer, were coexpressed (Fig. 3A and supplemental Fig. S2). We also observed high FRET between Hpo-CFPC and Hpo-YFPC, and the change in FRET signals of the Hpo C terminus was not as dramatic as that of the Hpo N terminus with co-expression of Ex and Mer (Fig. 3A and supplemental Fig. S2). GST pull-down and immunoprecipitation experiments confirmed that the Hpo N-terminal kinase domain (amino acids 1–342) interacts with itself or endogenous Hpo (supplemental Fig. S3, A and B), a result in agreement with the recent crystallographic studies of Mst1, Mst3, and Mst4 kinase domains (27). These observations suggested that Drosophila Hpo N-terminal kinase domains indeed form homodimers facilitated by the upstream regulators. On the other hand, homodimers formed by the Hpo C-terminal SARAH domains showed only subtle conformational change upon activation.

Because Hpo and Mst1 share over 70% sequence identity in their N-terminal region, we modeled a three-dimensional structure of the Hpo kinase domain (amino acids 1–278) based on the crystal structure of the Mst1 kinase domain (Protein Data Bank entry 3CM). In the modeled dimer of Hpo kinase domains, the αH helix and part of the preceding loop of one molecule dock into the active cleft of the other, forming mainly hydrophobic intermolecular contacts with its αC helix, activation loop, and αH helix (Fig. 3B). The homodimeric interface may help maintain an active conformation for full activation of Hpo kinase. Conformational perturbation introduced by point mutation or deletion within this region is expected to affect Hpo kinase activity.

Based on the structural analysis, we first made a deletion form of the Hpo kinase domain (Hpo-NΔ238–246), in which amino acids 238–246 (corresponding to the αH helix and part of the preceding loop) in the Hpo kinase domain (Hpo-N, amino acids 1–342) were removed. Results from the in vitro pull-down assay showed that Hpo-NΔ238–246 could still form homodimers as the wild type Hpo kinase domain did (supplemental Fig. S3A). It is possible that additional residues other than amino acids 238–246 mediate homodimeric association after conformational rearrangement. We also reasoned that the dimeric interactions mediating Hippo kinase domain homoassociation are mainly hydrophobic in nature. Thus, either mutation or deletion of amino acids 238–246 disturbs the proper conformation of the activation loop and the αC helix rather than the complete dimerization process. To address whether Hpo autophosphorylation and activation require the proper conformation of this dimeric interface, we further generated series of point mutations that were predicted to disturb the conformation of its activation loop: M242E, M242P, R243P, R243A, and I245P. As a control, we also generated H240A mutant, which does not disturb the conformation of its activation loop base on our prediction. To test whether the Hpo C-terminal dimerization plays a role, we also generated the same mutations in the context of Hpo-N (kinase domain only): M242E-N, M242P-N, R243P-N, R243A-N, I245P-N, and H240A-N. We then performed a primary screen for the functional activity of these mutations by an S2 cell luciferase assay. As shown in supplemental Fig. S4, consistent with our prediction, all of the mutants exhibited a decrease in Hpo activity except for H240A. Furthermore, our results showed that Hpo C-terminal dimerization did not interfere with the function of these mutants (supplemental Fig. S4). Finally, we selected the M242E mutation for our following investigation.

We also generated other Hpo protein variants for further functional studies (Fig. 3C). Because phosphorylation of Hpo at Thr-195 has been implicated in the regulation of Hpo kinase activity (62), and the corresponding residue in Mst1, Thr-183, has been identified to be the autophosphorylation site (36), Thr-195 may be the autophosphorylation site of Drosophila Hpo. In addition, the reported Mst1 structure presumably possesses an active conformation, in which Thr-177 and Thr-183 are kept in phosphorylated status (27). To prevent phosphorylation, we then mutated their corresponding sites in Hpo (Thr-189 and Thr-195) to Ala (referred to as T189A and T195A). Conversely, the two mutations T189E and T195E were introduced to mimic the phosphorylation state of Hpo. A K71R mutant (Hpo KD), representing the inactive form of Hpo, was also generated (20).

We first measured the phosphorylation level of these Hpo mutants in cultured Drosophila S2 cells, and the mobility was detected using a Phos-Tag gel shift assay. Clearly, on the Phos-Tag gel, only one obvious shift band corresponding to the Hpo autophosphorylation was detected (Fig. 3D). This shift band disappeared in KD and T195A and was almost undetectable in M242E mutants, suggesting that Thr-195 is the primary autophosphorylation site in Hpo, and the conformational perturbation introduced by M242E mutation readily diminished the kinase activity. Of note, the phosphorylated shift forms of T189A and T189E could still be detected, indicating that Thr-189 is not the critical autophosphorylation site or at least is not essential for the autophosphorylation of the residue Thr-195. We then further confirmed this result using the phospho-specific antibody that recognizes the Mst1/2 phosphorylation on Thr-183 as well as the equivalent residue Thr-195 of Hpo (Fig. 3E). Consistent with the Phos-Tag gel shift assay (Fig. 3D), the corresponding phosphorylation bands were only shown in the samples of Hpo WT and T189A/E. The I634D also showed an equivalent phosphorylation band similar to Hpo WT. Thus, Hpo Thr-195 is the critical site for Hpo autophosphorylation. The conformational perturbation of the dimeric interface consisting of Hpo kinase domains interferes with its autophosphorylation, whereas loss of the C-terminal Hpo dimers does not affect the Hpo autophosphorylation.

To further investigate the link among Hpo kinase activity, autophosphorylation, and homodimerization, we tested whether these Hpo variants still retain their kinase activities by in vitro kinase assay. We used immunoprecipitated FLAG-tagged Hpo proteins from S2 cells and the purified GST-Mats protein as a substrate (63). Results showed that wild type Hpo undergoes autophosphorylation and phosphorylates the substrate GST-Mats, whereas the kinase-dead mutation of Hpo, K71R, completely abolished its catalytic activity (Fig. 3F). Both HpoT189A and HpoT189E mutants remained as active as the wild type Hpo (Fig. 3F, lanes 5 and 6). The HpoT195A mutant totally lost its kinase activity, but the HpoT195E mutant retained catalytic activity, albeit less potent than the wild type Hpo. The HpoM242E and HpoΔ238–246 mutants were completely inactive. On the other hand, the HpoI634D mutant showed slightly reduced kinase activity when compared with the wild type Hpo (Fig. 3F, compare lanes 11 and 3). Collectively, these results suggested that the Hpo catalytic activity depends on its Thr-195 autophosphorylation, and the N-terminal dimeric conformation is crucial for its kinase activity. The Hpo C-terminal dimerization alters its catalytic activity, possibly in a manner of inducing the N-terminal dimeric conformation or changing the substrate specificity. Of note, the HpoT195E mutant showed less activity in vitro, most likely due to the fact that the mutation does not fully mimic the Thr-195 phosphorylation and therefore is not optimal for full activation.

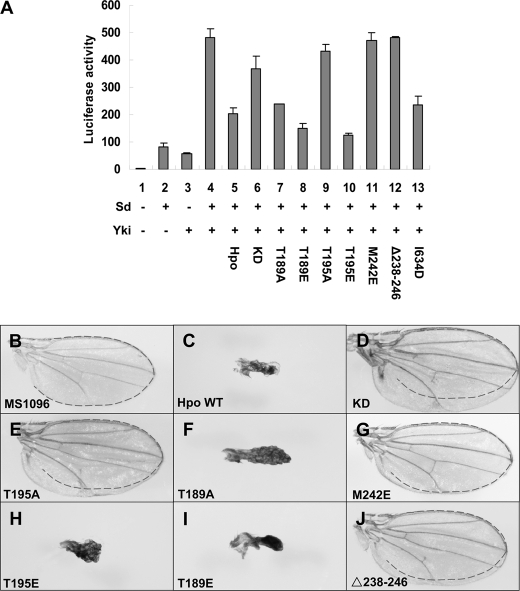

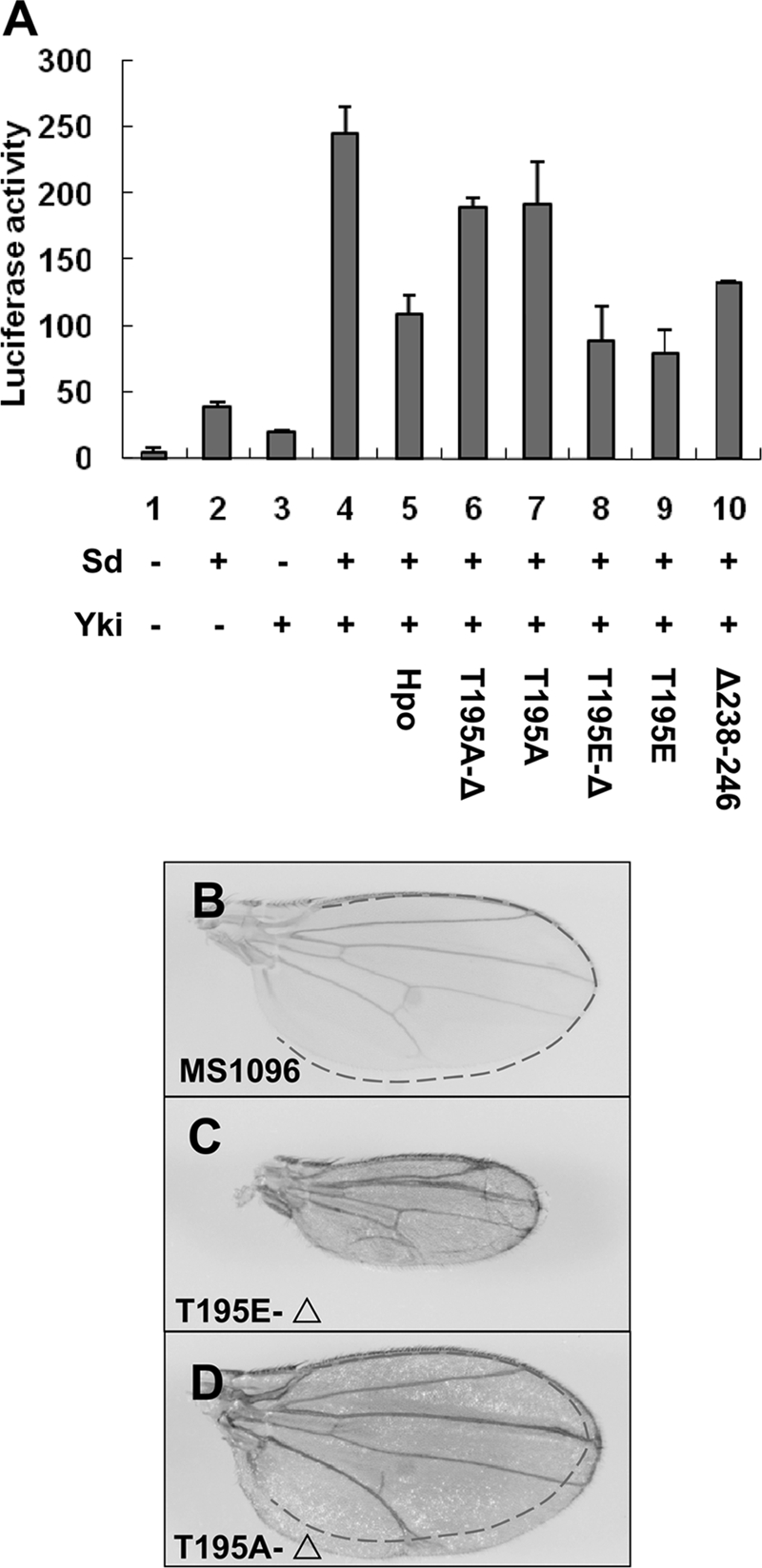

In Vivo Activities of Hpo Variants and Dosage-dependent Genetic Interactions between Hpo Variants and Yki

We then investigated whether these Hpo variants have similar functional defects in vivo. Co-transfection of T195A, Δ238–246, M242E, or the Hpo KD together with Sd and Yki failed to suppress the luciferase activity induced by Yki-Sd (Fig. 4A). Conversely, the HpoT189A, HpoT189E, and HpoT195E mutants all showed strong Hpo activity (Fig. 4A, lanes 7, 8, and 10). On the other hand, HpoI634D mutant was not as effective as the wild type Hpo to suppress Yki-Sd (Fig. 4A, lane 13). Thus, consistent with earlier in vitro kinase assays, Hpo activity is dependent on autophosphorylation at Thr-195 and dimerization. The N-terminal dimerization appears to be more critical than the C-terminal dimerization because disruption of the C-terminal coiled coil-mediated dimerization only partially affects the Hippo activity.

FIGURE 4.

Homodimerization of Hpo kinase domain is critical for its function in growth control. A, S2 cells were transfected with the indicated Hpo or Hpo variants together with Sd, Yki, and the 3×Sd2-Luc reporter gene, and the cell lysates were subjected to a Dual-Luciferase assay. Error bars, S.D. B–J, wild type female wings (B) or female wings expressing wild type Hpo (C) or Hpo variants (D–J) with MS1096. The dotted lines display the wing size of MS1096 control.

To further confirm whether the N-terminal dimerization is important for Hpo activation, we engineered hybrid proteins by fusing Hpo N-terminal variants with Fv2 protein to test whether induced N-terminal dimerization increases pathway activity in the absence of Hpo C terminus using luciferase assays. As shown in supplemental Fig. S5 (lanes 4–9), the enhanced dimerization induces higher activity mediated by the Hpo kinase domain with Fv2 after treatment with AP20187. Among the other hybrid variants, only the Hpo variant N-T195E-Fv2 showed inducible activity, but not the ones carrying M242E or T195A mutations (supplemental Fig. S5). These results suggested that the induced dimer enhances the Hpo kinase activity.

Next, we compared the activity of these Hpo variants in Drosophila by overexpression using transgenic flies. To ensure that the transgenes were expressed at the same expression level, all of the transformants were generated by using the phiC31 integration system (54). Driven by wing-specific Gal4 driver MS1096, Hpo variants carrying T189A, T189E, or T195E mutations caused small and shrunken wings similarly as the wild type Hpo (Fig. 4, C, F, H, and I, and supplemental Fig. S6J), suggesting that they possess similar activity as the wild type. In contrast, we found that overexpression of Hpo variants carrying M242E or Δ238–246 resulted in a slight increase in wing size, similar to the observations in animals overexpressing HpoT195A (Fig. 4, E, G, and J, and supplemental Fig. S6J). Last but not least, only the KD form resulted in significant enlargement of the wings compared with the MS1096 control (Fig. 4, B and D, and supplemental Fig. S6J).

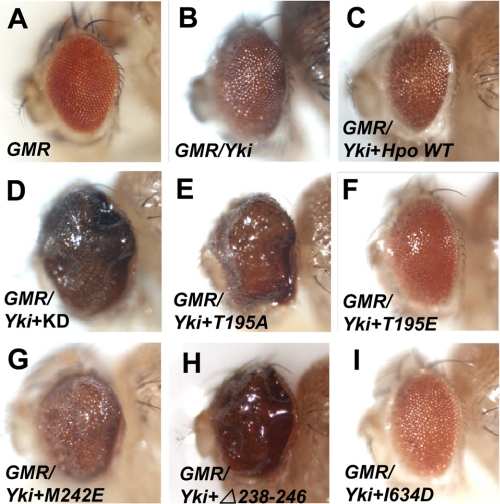

We further investigated Hpo activities using a genetic interaction assay with Yki in Drosophila eyes. Overexpression of UAS-Yki posterior to the morphogenetic furrow using the GMR-Gal4 driver (hereafter referred as GMR-Yki) resulted in enlarged eyes (Fig. 5 and supplemental Fig. S6; compare Fig. 5B and supplemental Fig. S6B with Fig. 5A and supplemental Fig. S6A). Expression of UAS-hpo using GMR-Gal4 resulted in 100% lethality at early pupal stage, whereas co-expression of the wild type Hpo and Yki led to small rough eyes (Fig. 5C and supplemental Fig. S6C). Like the wild type, the HpoT195E overexpression also induces small rough eyes in the GMR-yki background; however, the HpoI634D overexpression suppressed the GMR-Yki overgrowth phenotype, leading to rough eyes (Fig. 5, F and I, and supplemental Fig. S6, F and I). On the other hand, co-expression of Hpo KD resulted in a dramatic increase in eye size (Fig. 5D and supplemental Fig. S6D). Similar but weaker phenotypic enhancement was obtained in flies overexpressing HpoT195A, HpoM242E, or Δ238–246 together with Yki by GMR-Gal4 (Fig. 5, E, G, and H and supplemental Fig. S6, E, G, and H). These results convincingly showed that Thr-195 is critical for Hpo kinase activity, and the N-terminal dimerization is essential for the Hpo activity. Consistent with the in vitro data, our in vivo studies confirmed that residues around Met-242 within the region of the Hpo homodimeric interface play an important role in maintaining the active conformation of Hpo kinase because mutations in this region abolish the kinase activity.

FIGURE 5.

Hpo variants genetically interact with Yki. A–I, adult eyes of GMR (A), GMR-Gal4 UAS-Yki (B), GMR-Gal4 UAS-Yki plus Hpo wild type (C), GMR-Gal4 UAS-Yki plus Hpo KD (D), and GMR-Gal4 UAS-Yki plus Hpo variants (E–I).

Hpo Dimerization Is the Prerequisite for Its Autophosphorylation and Activity

To investigate whether the homodimerization of Hpo is also critical for its function after autophosphorylation, we made mutant proteins by combining the Δ238–246 deletion with the mutation T195A or T195E (referred to as T195A-Δ or T195E-Δ, respectively). The T195E-Δ mutant proteins are predicted to be incapable of forming native homodimeric association via the kinase domain, but they contain the mimic autophosphorylation site Thr-195. In luciferase assays, we found that T195E-Δ activity was recovered when compared with the HpoΔ238–246 mutant (Fig. 6A, compare lane 8 with lane 10), and this activity is similar to, albeit less potent than, the T195E mutant (Fig. 6A, compare lane 8 with lane 9). Consistently, driven by wing-specific Gal4 driver MS1096, T195E-Δ showed stronger pathway activity compared with Δ238–246 (compare Fig. 6C with Fig. 4J) but much weaker than that of T195E, which dramatically reduced the wing size (compare Fig. 6C with Fig. 4H). In contrast, the T195A-Δ and T195A mutants did not show substantially different activities either by luciferase assay or in vivo analysis (Fig. 6A, compare lane 6 with lane 7; compare Fig. 6D with Fig. 4E). These results suggested that, although the dimeric interface of the N-terminal kinase domain was deformed by Δ238–246, the HpoT195E-Δ, but not T195A-Δ, was still functional and capable of triggering Hpo signaling. Taking this result together with the results of previous kinase assays, we concluded that the dimerization is the prerequisite of Hpo autophosphorylation at Thr-195 and leads to Hpo activation.

FIGURE 6.

Hpo dimerization is the prerequisite of autophosphorylation and activity. A, S2 cells were transfected with the indicated Hpo or Hpo variants together with Sd, Yki, and the 3×Sd2-Luc reporter gene, and the cell lysates were subjected to a Dual-Luciferase assay. Error bars, S.D. B–D, wild type wings (B) or wings expressing UAS-Hpo-T195E-Δ (C) or UAS-Hpo-T195A-Δ (D) with MS1096 to show the wing size change of these mutants.

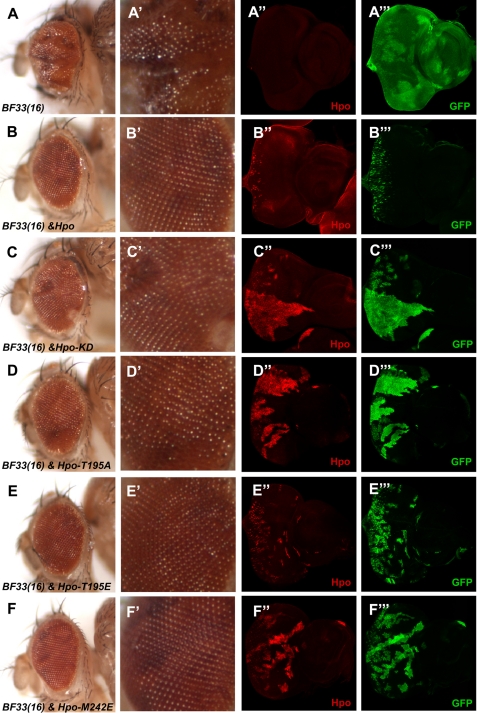

Abilities of Hpo Variants to Rescue Overgrowth Phenotype of Hpo Mutants

To investigate whether these Hpo variants still possess Hpo activity independent of endogenous Hpo in vivo, we further tested their ability to rescue the hpoBF33 null allele in Drosophila using the MARCM technique to express these variants in clones mutant for hpoBF33(16,55). As shown in Fig. 7, adult eyes carrying hpoBF33 mutant clones were overgrown, showing enlarged and folded eyes (Fig. 7A). In contrast, wild type Hpo expression in hpoBF33 mutant clones was sufficient to inhibit the overgrowth and rescued the adult phenotype, resulting in nearly normal eye size (Fig. 7B). Expression of Hpo KD in the hpoBF33 clones still caused eyes that were rough and overgrown but somehow less folded compared with the eyes of hpoBF33 mosaic flies (Fig. 7C). The eyes of the hpoBF33 mosaic flies containing Hpo-T195A are even less folded than the eyes of those containing Hpo KD (Fig. 7D). Moreover, only rough and slightly bigger eyes are shown in the hpoBF33 mosaic flies that express Hpo-M242E (Fig. 7F). Similar to overexpression of the wild-type Hpo in hpoBF33 mosaic flies, overexpression of the HpoT195E completely rescued the eye overgrowth in hpoBF33 mosaic flies (Fig. 7E). We further compared the size of MARCM clones in the eye imaginal discs. The mosaic clones of hpoBF33 were large because of the competitive properties; however, when the wild type Hpo was overexpressed, clones were very small (Fig. 7, compare B‴ with A‴). The Hpo KD and T195A clones were notably larger than the T195E and M242E clones (Fig. 7, compare C‴ and D‴ with E‴ and F‴). Furthermore, the T195E clones were apparently larger than the wild type Hpo clones (Fig. 7, compare E‴ with B‴), although they showed a similar adult phenotype, and the M242E clones were smaller than the ones of Hpo KD and T195A (Fig. 7, compare F‴ with C‴ and D‴). These sensitive genetic rescue results reveal that the M242E has less reduced activity compared with Hpo KD and T195A mutants.

FIGURE 7.

Hpo variants with kinase activity rescue the overgrowth phenotype of hpo mutants. A–A‴, adult eyes or eye discs containing hpoBF33 mosaic clones. hpoBF33 is a truncating null allele. B–F‴, adult eyes or eye discs with hpoBF33 clones expressing wild type Hpo or the indicated Hpo variants. hpoBF33 mutant cells expressing Hpo wild type and variants were labeled by both FLAG and GFP expression. A′–F′, magnified images of the eye surface morphology.

DISCUSSION

Previous studies have revealed that Hpo signaling is essential for tissue growth and organ size control in both Drosophila and vertebrates (14). However, despite the emerging significance of this signaling transduction pathway, the mechanism by which the Hpo kinase is regulated is poorly understood. Based on a combination of structural and functional analyses, our results demonstrate that the autophosphorylation and kinase activation of Hpo depends on its homodimerization, which is mediated by two distinct functional domains. We show that dimerization of the N-terminal kinase domain, which is mediated predominantly by hydrophobic interactions, is essential for Hpo autophosphorylation and its kinase activation, whereas the coiled coil-mediated dimerization of the C-terminal SARAH domain is probably necessary to modulate Hpo function.

Consistent with previous studies of Mst1/2 (28), we found that the dimerization of the Hpo SARAH domain is not essential for its kinase activity. Disruption of the dimerization mediated by the SARAH domain only led to a partial decrease for its autophosphorylation and kinase activity (Fig. 3E). It is important to emphasize that although the Hpo SARAH domain seems to be non-essential for autophosphorylation, it may be crucial for regulatory functions based on existing studies of Sav and RASSF in both Drosophila and mammalian cells (51, 64, 65). Indeed, wild type Hpo always shows higher activity than just the kinase domain in vivo because GMR-Hpo results in 100% lethality at the early pupal stage, but expressing the GMR-Hpo-kinase domain alone results in a weaker phenotype. Misexpressed HpoI634D in Drosophila wing results in a discernible change compared with the wild type Hpo (Fig. 1, compare I with H). It is likely that the strong kinase activity caused by overexpression may conceal the regulatory function of the SARAH domain. Our FRET analysis showed that a higher basal level of interaction between Hpo C termini is detected, compared with that between the Hpo N termini. However, when activated by the upstream signaling, the FRET change between C termini is not as dramatic as that observed for that between the N termini (Fig. 3A), suggesting that the SARAH domain may constitutively form dimers, whereas the conformation of the N-terminal dimer is inducible. At this point, we speculate that one possible role of the Hpo C-terminal dimerization is to function as a platform to facilitate the intermolecular association between the N-terminal kinase domains. In addition, it seems that the dimerization of SARAH domain may help to stabilize Hpo because we repeatedly detected that the I634D is less stable than the wild type Hpo when expressed in S2 cells.4 Our immunoprecipitation data support this point by showing that the FLAG-Hpo-C-I634D barely pulled down the endogenous Hpo (supplemental Fig. S3B). Furthermore, the activity of Hpo could be regulated by the dimerization partners, which are recognized by the SARAH domain in the upstream or downstream branches of the Hpo signaling pathway, such as dRASSF and Sav (51). Consistent with this finding, we showed that Hpo and Sav/dRASSF heterodimerize via the conserved C-terminal SARAH domains of both proteins (Fig. 1, E and F).

Hpo SARAH domain plays a dual role in regulating Hpo activity. Besides the functional regulation of Hpo through homodimerization as well as through heterodimerization with other SARAH-containing partners, the SARAH domain of Hpo participates in the regulation of nucleocytoplasmic distribution of Hpo via a CRM1-dependent nuclear export mechanism. We identified two functional NESs that are both located in the Hpo C-terminal region, including the one located in the SARAH domain (Fig. 3C). We showed that the nucleus-cytoplasm shuttling of Hpo is regulated by the nuclear export pathway, and the translocation of Hpo is critical for its functional regulation because the HpoNES1/2 lost most of its signaling activity in vitro and in vivo (Figs. 1J and 2). These findings will bring novel insights to our present functional studies and help to answer questions regarding the importance in regulating nuclear-cytoplasmic translocation of Hpo and the function of Hpo in the nucleus.

The Hpo kinase domain (Hpo-N) shows a diffused localization (Fig. 2D) when the Hpo C-terminal part is deleted, and its pathway activity is much lower than the activity of wild type Hpo, which localizes mainly in the cytoplasm (Fig. 2A). However, mammalian Mst1 is activated by autophosphorylation and the caspase-dependent cleavage, which releases the active 36-kDa N-terminal kinase domain (34, 36, 66). The active truncated kinase translocates into the nucleus and promotes apoptosis by phosphorylating nuclear substrates (67). Because Hpo does not have the conserved caspase cleavage site, our observation suggested that Hpo may exhibit the growth-suppressive activity mainly in the cytoplasm; therefore, a different mechanism from the mammalian MST needs to be determined. Mammalian Mst1/2 protein was localized predominantly or entirely in the cytoplasm in an LMB-dependent manner (37), and the function of nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of MST1/2 needs to be further studied.

Although considerable progress has been made in investigating the mechanisms of regulation and function of the SARAH domain in the Hpo signaling pathway, much less is known about the activating mechanisms of the N-terminal kinase domain, especially in vivo. We performed a structure-function analysis of Drosophila Hpo based on the modeled three-dimensional structure of Hpo kinase domain. As a result, we identified that Thr-195 is the autophosphorylation site and critical for Hpo kinase activity. More importantly, we demonstrated that the N-terminal kinase domain of Hpo mediates homodimerization independently of the C-terminal SARAH domain and that the dimeric conformation of the kinase domain is essential for intermolecular autophosphorylation. As shown in Fig. 3, D–F, and supplemental Fig. S3A, a point mutation, M242E, which is predicted to interfere with the N-terminal dimeric conformation, resulted in the loss of autophosphorylation and kinase activity but not self-interaction. All of our genetic analyses and genetic interaction data in Drosophila were consistent with the biochemistry results and supported our findings (Figs. 4 and 5). Moreover, overexpression of the deletion form Δ238–246 induces bigger organ size using different drivers in Drosophila (Figs. 4J and 5H) compared with M242E (Figs. 4G and 5G). This is consistent with our prediction that Δ238–246 interferes with the dimeric conformation to an even larger extent and therefore functionally imposes a stronger dominant-negative effect compared with the point mutation M242E. Hpo KD and T195A behaved in a dominant-negative manner because they may nonproductively associate with endogenous Hpo or Sav and block signal activation, whereas overexpressed M242E and Δ238–246 may interfere with endogenous Hpo homodimer, as shown (supplemental Fig. S3B), and exhibited similar dominant effects. In addition, we provided evidence that the intermolecular autophosphorylation of Thr-195 is only achieved when its kinase domains are properly dimerized. We propose that the kinase activity of Hpo depends on Thr-195 phosphorylation, whereas proper dimerization of the kinase domain is the prerequisite of its phosphorylation. Thus, once the autophosphorylation happens, the dimerization may not be that critical anymore. As we show in Fig. 6, A and C, the hybrid form T195E-Δ still possesses pathway activity.

In summary, our biochemical and genetic results demonstrate, for the first time, that homodimerization and nucleocytoplasmic shuttling regulate the biological function of Hpo. The N-terminal dimeric conformation of Hpo is essential for its intermolecular autophosphorylation and kinase activation and organ size control.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yingzi Yang, Dr. Chi-chung Hui, Dr. Margaret Ho, and Dr. Hongbin Ji for critical comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Basic Research Program of China 973 Program Grants 2010CB912101, 2012CB945001, and 2011CB943902; National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 30971646, 30971647, 31171394, and 31171414; Shanghai Pujiang Program Grant 09PJ1410900; National Key Basic Research and Development Program of China Grant 2011CB915502; and “Strategic Priority Research Program” of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Grants XDA01010405 and XDA01010406.

This article contains supplemental Figs. S1–S6.

Y. Jin, L. Dong, Y. Lu, W. Wu, Q. Hao, Z. Zhou, J. Jiang, Y. Zhao, and L. Zhang, unpublished observation.

- dRASSF

- Drosophila RASSF

- MARCM

- mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker

- LMB

- leptomycin B

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- NES

- nuclear export signal

- KD

- kinase-dead

- CFP

- cyan fluorescent protein

- CFPAP

- CFP signal obtained after photobleaching YFP

- CFPBP

- CFP signal obtained before photobleaching YFP.

REFERENCES

- 1. Conlon I., Raff M. (1999) Size control in animal development. Cell 96, 235–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Halder G., Johnson R. L. (2011) Hippo signaling. Growth control and beyond. Development 138, 9–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhao B., Li L., Lei Q., Guan K. L. (2010) The Hippo-YAP pathway in organ size control and tumorigenesis. An updated version. Genes Dev. 24, 862–874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pan D. (2007) Hippo signaling in organ size control. Genes Dev. 21, 886–897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang L., Yue T., Jiang J. (2009) Hippo signaling pathway and organ size control. Fly 3, 68–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Yin M., Zhang L. (2011) Hippo signaling. A hub of growth control, tumor suppression, and pluripotency maintenance. J. Genet. Genomics 38, 471–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Varelas X., Miller B. W., Sopko R., Song S., Gregorieff A., Fellouse F. A., Sakuma R., Pawson T., Hunziker W., McNeill H., Wrana J. L., Attisano L. (2010) The Hippo pathway regulates Wnt/β-Catenin signaling. Dev. Cell 18, 579–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fernandez-L A., Northcott P. A., Dalton J., Fraga C., Ellison D., Angers S., Taylor M. D., Kenney A. M. (2009) YAP1 is amplified and up-regulated in hedgehog-associated medulloblastomas and mediates Sonic hedgehog-driven neural precursor proliferation. Genes Dev. 23, 2729–2741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Alarcón C., Zaromytidou A. I., Xi Q., Gao S., Yu J., Fujisawa S., Barlas A., Miller A. N., Manova-Todorova K., Macias M. J., Sapkota G., Pan D., Massagué J. (2009) Nuclear CDKs drive Smad transcriptional activation and turnover in BMP and TGF-β pathways. Cell 139, 757–769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sun G., Irvine K. D. (2011) Regulation of Hippo signaling by Jun kinase signaling during compensatory cell proliferation and regeneration, and in neoplastic tumors. Dev. Biol. 350, 139–151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang J., Ji J. Y., Yu M., Overholtzer M., Smolen G. A., Wang R., Brugge J. S., Dyson N. J., Haber D. A. (2009) YAP-dependent induction of amphiregulin identifies a non-cell-autonomous component of the Hippo pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 1444–1450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ren F., Wang B., Yue T., Yun E. Y., Ip Y. T., Jiang J. (2010) Hippo signaling regulates Drosophila intestine stem cell proliferation through multiple pathways. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 21064–21069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McNeill H., Woodgett J. R. (2010) When pathways collide. Collaboration and connivance among signaling proteins in development. Nat. Rev. 11, 404–413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pan D. (2010) The Hippo signaling pathway in development and cancer. Dev. Cell 19, 491–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Harvey K. F., Pfleger C. M., Hariharan I. K. (2003) The Drosophila Mst ortholog, Hippo, restricts growth and cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis. Cell 114, 457–467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Jia J., Zhang W., Wang B., Trinko R., Jiang J. (2003) The Drosophila Ste20 family kinase dMST functions as a tumor suppressor by restricting cell proliferation and promoting apoptosis. Genes Dev. 17, 2514–2519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lai Z. C., Wei X., Shimizu T., Ramos E., Rohrbaugh M., Nikolaidis N., Ho L. L., Li Y. (2005) Control of cell proliferation and apoptosis by mob as tumor suppressor, mats. Cell 120, 675–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pantalacci S., Tapon N., Léopold P. (2003) The Salvador partner Hippo promotes apoptosis and cell cycle exit in Drosophila. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 921–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Udan R. S., Kango-Singh M., Nolo R., Tao C., Halder G. (2003) Hippo promotes proliferation arrest and apoptosis in the Salvador/Warts pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 914–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wu S., Huang J., Dong J., Pan D. (2003) Hippo encodes a Ste-20 family protein kinase that restricts cell proliferation and promotes apoptosis in conjunction with Salvador and Warts. Cell 114, 445–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Goulev Y., Fauny J. D., Gonzalez-Marti B., Flagiello D., Silber J., Zider A. (2008) SCALLOPED interacts with YORKIE, the nuclear effector of the Hippo tumor suppressor pathway in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 18, 435–441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Huang J., Wu S., Barrera J., Matthews K., Pan D. (2005) The Hippo signaling pathway coordinately regulates cell proliferation and apoptosis by inactivating Yorkie, the Drosophila homolog of YAP. Cell 122, 421–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wu S., Liu Y., Zheng Y., Dong J., Pan D. (2008) The TEAD/TEF family protein Scalloped mediates transcriptional output of the Hippo growth-regulatory pathway. Dev. Cell 14, 388–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zhang L., Ren F., Zhang Q., Chen Y., Wang B., Jiang J. (2008) The TEAD/TEF family of transcription factor Scalloped mediates Hippo signaling in organ size control. Dev. Cell 14, 377–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Neto-Silva R. M., de Beco S., Johnston L. A. (2010) Evidence for a growth-stabilizing regulatory feedback mechanism between Myc and Yorkie, the Drosophila homolog of Yap. Dev. Cell 19, 507–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhao B., Li L., Guan K. L. (2010) Hippo signaling at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 123, 4001–4006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Record C. J., Chaikuad A., Rellos P., Das S., Pike A. C., Fedorov O., Marsden B. D., Knapp S., Lee W. H. (2010) Structural comparison of human mammalian ste20-like kinases. PLoS ONE 5, e11905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Creasy C. L., Ambrose D. M., Chernoff J. (1996) The Ste20-like protein kinase, Mst1, dimerizes and contains an inhibitory domain. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 21049–21053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Scheel H., Hofmann K. (2003) A novel interaction motif, SARAH, connects three classes of tumor suppressor. Curr. Biol. 13, R899–R900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Zhou D., Conrad C., Xia F., Park J. S., Payer B., Yin Y., Lauwers G. Y., Thasler W., Lee J. T., Avruch J., Bardeesy N. (2009) Mst1 and Mst2 maintain hepatocyte quiescence and suppress hepatocellular carcinoma development through inactivation of the Yap1 oncogene. Cancer Cell 16, 425–438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Song H., Mak K. K., Topol L., Yun K., Hu J., Garrett L., Chen Y., Park O., Chang J., Simpson R. M., Wang C. Y., Gao B., Jiang J., Yang Y. (2010) Mammalian Mst1 and Mst2 kinases play essential roles in organ size control and tumor suppression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 1431–1436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Lu L., Li Y., Kim S. M., Bossuyt W., Liu P., Qiu Q., Wang Y., Halder G., Finegold M. J., Lee J. S., Johnson R. L. (2010) Hippo signaling is a potent in vivo growth and tumor suppressor pathway in the mammalian liver. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 1437–1442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Radu M., Chernoff J. (2009) The DeMSTification of mammalian Ste20 kinases. Curr. Biol. 19, R421–R425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Graves J. D., Gotoh Y., Draves K. E., Ambrose D., Han D. K., Wright M., Chernoff J., Clark E. A., Krebs E. G. (1998) Caspase-mediated activation and induction of apoptosis by the mammalian Ste20-like kinase Mst1. EMBO J. 17, 2224–2234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Avruch J., Xavier R., Bardeesy N., Zhang X. F., Praskova M., Zhou D., Xia F. (2009) Rassf family of tumor suppressor polypeptides. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 11001–11005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Glantschnig H., Rodan G. A., Reszka A. A. (2002) Mapping of MST1 kinase sites of phosphorylation. Activation and autophosphorylation. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 42987–42996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lee K. K., Yonehara S. (2002) Phosphorylation and dimerization regulate nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of mammalian STE20-like kinase (MST). J. Biol. Chem. 277, 12351–12358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Qiao M., Wang Y., Xu X., Lu J., Dong Y., Tao W., Stein J., Stein G. S., Iglehart J. D., Shi Q., Pardee A. B. (2010) Mst1 is an interacting protein that mediates PHLPPs' induced apoptosis. Mol. Cell 38, 512–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Silva E., Tsatskis Y., Gardano L., Tapon N., McNeill H. (2006) The tumor suppressor gene fat controls tissue growth upstream of Expanded in the Hippo signaling pathway. Curr. Biol. 16, 2081–2089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Baena-Lopez L. A., Rodríguez I., Baonza A. (2008) The tumor suppressor genes dachsous and fat modulate different signaling pathways by regulating dally and dally-like. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 9645–9650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cho E., Feng Y., Rauskolb C., Maitra S., Fehon R., Irvine K. D. (2006) Delineation of a Fat tumor suppressor pathway. Nat. Genet. 38, 1142–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tyler D. M., Li W., Zhuo N., Pellock B., Baker N. E. (2007) Genes affecting cell competition in Drosophila. Genetics 175, 643–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Willecke M., Hamaratoglu F., Kango-Singh M., Udan R., Chen C. L., Tao C., Zhang X., Halder G. (2006) The fat cadherin acts through the hippo tumor suppressor pathway to regulate tissue size. Curr. Biol. 16, 2090–2100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Yu J., Zheng Y., Dong J., Klusza S., Deng W. M., Pan D. (2010) Kibra functions as a tumor suppressor protein that regulates Hippo signaling in conjunction with Merlin and Expanded. Dev. Cell 18, 288–299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bennett F. C., Harvey K. F. (2006) Fat cadherin modulates organ size in Drosophila via the Salvador/Warts/Hippo signaling pathway. Curr. Biol. 16, 2101–2110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hamaratoglu F., Willecke M., Kango-Singh M., Nolo R., Hyun E., Tao C., Jafar-Nejad H., Halder G. (2006) The tumor suppressor genes NF2/Merlin and Expanded act through Hippo signaling to regulate cell proliferation and apoptosis. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 27–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Maitra S., Kulikauskas R. M., Gavilan H., Fehon R. G. (2006) The tumor suppressors Merlin and Expanded function cooperatively to modulate receptor endocytosis and signaling. Curr. Biol. 16, 702–709 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pellock B. J., Buff E., White K., Hariharan I. K. (2007) The Drosophila tumor suppressors Expanded and Merlin differentially regulate cell cycle exit, apoptosis, and Wingless signaling. Dev. Biol. 304, 102–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Baumgartner R., Poernbacher I., Buser N., Hafen E., Stocker H. (2010) The WW domain protein Kibra acts upstream of Hippo in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 18, 309–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Genevet A., Wehr M. C., Brain R., Thompson B. J., Tapon N. (2010) Kibra is a regulator of the Salvador/Warts/Hippo signaling network. Dev. Cell 18, 300–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Polesello C., Huelsmann S., Brown N. H., Tapon N. (2006) The Drosophila RASSF homolog antagonizes the hippo pathway. Curr. Biol. 16, 2459–2465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Ribeiro P. S., Josué F., Wepf A., Wehr M. C., Rinner O., Kelly G., Tapon N., Gstaiger M. (2010) Combined functional genomic and proteomic approaches identify a PP2A complex as a negative regulator of Hippo signaling. Mol. Cell 39, 521–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Hwang E., Ryu K. S., Pääkkönen K., Güntert P., Cheong H. K., Lim D. S., Lee J. O., Jeon Y. H., Cheong C. (2007) Structural insight into dimeric interaction of the SARAH domains from Mst1 and RASSF family proteins in the apoptosis pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 9236–9241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bischof J., Maeda R. K., Hediger M., Karch F., Basler K. (2007) An optimized transgenesis system for Drosophila using germ line-specific phiC31 integrases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 3312–3317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lee T., Luo L. (2001) Mosaic analysis with a repressible cell marker (MARCM) for Drosophila neural development. Trends Neurosci. 24, 251–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kinoshita E., Kinoshita-Kikuta E., Takiyama K., Koike T. (2006) Phosphate-binding tag, a new tool to visualize phosphorylated proteins. Mol. Cell Proteomics 5, 749–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Clackson T., Yang W., Rozamus L. W., Hatada M., Amara J. F., Rollins C. T., Stevenson L. F., Magari S. R., Wood S. A., Courage N. L., Lu X., Cerasoli F., Jr., Gilman M., Holt D. A. (1998) Redesigning an FKBP-ligand interface to generate chemical dimerizers with novel specificity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 10437–10442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Gazdoiu S., Yamoah K., Wu K., Escalante C. R., Tappin I., Bermudez V., Aggarwal A. K., Hurwitz J., Pan Z. Q. (2005) Proximity-induced activation of human Cdc34 through heterologous dimerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 15053–15058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kudo N., Matsumori N., Taoka H., Fujiwara D., Schreiner E. P., Wolff B., Yoshida M., Horinouchi S. (1999) Leptomycin B inactivates CRM1/exportin 1 by covalent modification at a cysteine residue in the central conserved region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 9112–9117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Mattaj I. W., Englmeier L. (1998) Nucleocytoplasmic transport. The soluble phase. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 265–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Centonze V. E., Firulli B. A., Firulli A. B. (2004) Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) as a method to calculate the dimerization strength of basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) proteins. Biol. Proced. Online 6, 78–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Colombani J., Polesello C., Josué F., Tapon N. (2006) Dmp53 activates the Hippo pathway to promote cell death in response to DNA damage. Curr. Biol. 16, 1453–1458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Wei X., Shimizu T., Lai Z. C. (2007) Mob as tumor suppressor is activated by Hippo kinase for growth inhibition in Drosophila. EMBO J. 26, 1772–1781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Praskova M., Khoklatchev A., Ortiz-Vega S., Avruch J. (2004) Regulation of the MST1 kinase by autophosphorylation, by the growth inhibitory proteins, RASSF1 and NORE1, and by Ras. Biochem. J. 381, 453–462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Callus B. A., Verhagen A. M., Vaux D. L. (2006) Association of mammalian sterile twenty kinases, Mst1 and Mst2, with hSalvador via C-terminal coiled coil domains, leads to its stabilization and phosphorylation. FEBS J. 273, 4264–4276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lee K. K., Ohyama T., Yajima N., Tsubuki S., Yonehara S. (2001) MST, a physiological caspase substrate, highly sensitizes apoptosis both upstream and downstream of caspase activation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 19276–19285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Cheung W. L., Ajiro K., Samejima K., Kloc M., Cheung P., Mizzen C. A., Beeser A., Etkin L. D., Chernoff J., Earnshaw W. C., Allis C. D. (2003) Apoptotic phosphorylation of histone H2B is mediated by mammalian sterile twenty kinase. Cell 113, 507–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.