Abstract

There is a growing acceptance of the utility of mixed methods in health sciences but there is no widely accepted set of ideas in regard to use of a conceptual or theoretical framework to guide inquiry. Few mixed methods health science articles report the use of such a framework. Lack of available conceptual maps provided by theoretical frameworks, necessary intricacy of design, and the qualitative “black box” tradition all contribute to a dearth of methodological guidance in such studies. This article uses a funded National Institutes of Health study as an example to explain the utility of a theoretical framework in conceptualizing a study, making design decisions such as sampling and recruitment, collecting and analyzing data, and data interpretation.

Keywords: Mixed methods, theoretical framework, conceptual framework

A mixed methods way of thinking is an orientation toward social inquiry that actively invites us to participate in dialogue about multiple ways of seeing and hearing, multiple ways of making sense of the social world, and multiple standpoints on what is important and to be valued and cherished (Greene, 2008, p. 20).

Introduction

The term “mixed methods” is a recent one. Definitions, language, nomenclature, and typologies of mixed methods designs remain varied, although it is commonly considered that studies of this type must combine qualitative and quantitative research in viewpoints, data collection and analysis, and inferences (Johnson, Onwuegbuzie & Turner, 2007; Happ, 2009). The evolving of mixed methods could be construed as constituting a “third methodological movement”, following quantitative and qualitative approaches (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2003), that is composed of distinctive mixing of practices from these other methodologies (Greene, 2008).

The purpose of this paper is to explore the worth of a theoretical framework in guiding the design and implementation of mixed methods studies. We will briefly trace the development of mixed methods and situate the method within the philosophical stance of pragmatism; examine the utility of the method in practice disciplines, especially those associated with the health sciences; and present theoretical frameworks as organizing structures in an area where few guidelines are available. We will then explore the use of such frameworks in extant mixed methods research. The context of nursing research will serve as a backdrop as we analyze a study conducted in the discipline of nursing that illustrates the importance of such frameworks in mixed methods studies. Finally, we will consider the question of their utility and necessity.

The Evolution of Mixed Methods and Their Relevance for Practice Disciplines

Although ideological differences between qualitative and quantitative researchers have existed for almost a century, the debate approached ignition point in the 1970s as postmodernism became accepted. Researchers waged “paradigm wars” in which they questioned whether or not qualitative and quantitative data could be combined (e.g., Guba & Lincoln, 1988). While the perceived dichotomies between the inductive-subjective-contextual approach and the deductive-objective-generalizing approach (described in Morgan, 2007) still continue today in some camps, other researchers have chosen to integrate these methodologies. For a more detailed overview of this dispute, see Tashakkori and Teddlie (1998) and Johnson, Onwuegbuzie, and Turner (2007).

This integrative methodology is consonant with the world-view of pragmatism - a leading foundation for mixed method research - where the focus is on the problem in its social and historical context rather than on the method, and multiple relevant forms of data collection are used to answer the research question(s) (Creswell, 2007). Pragmatism also addresses how our values and ethics, our politics and epistemologies, and our world-views as researchers directly influence our actions and our methodologies (Morgan, 2007). It offers a new opportunity to the “third methodological movement” (Teddlie & Tashakkori, 2003), that of a abduction-intersubjectivity-transferability approach (Morgan) in which reasoning moves back and forth between induction/deduction and subjectivity/objectivity, just as practicing researchers actually do. In regard to transferability, we ask how knowledge created through action and reflection can be used in a new setting and examine our evidentiary warrant for doing so. Johnson, Onwuegbuise and Turner (2007) call this a new research paradigm or “culture” comprised of shared ontological, epistemological, axiological, aesthetic and methodological beliefs, values and assumptions.

The concepts of action and reflection inherent in pragmatism foster recognition that professionals from practice disciplines often operate in what Schon (1983; 1987) calls the “low, swampy ground” where messy confusing problems defy rigorous technical problem-solving based on specialized scientific knowledge. Such problems may fall outside the usual bounds of inquiry because they are unstable or unique; set within complex, uncertain, puzzling, and ill-defined contexts; and contain stakeholder conflicts concerning desired solutions. Practitioners must decide whether or not they will take the “high ground” associated with positivistic research-based theory or techniques to solve a narrow set of technical problems, many of which, according to Schon, are of little importance to clients. Or will they take the “low ground” wherein lie the problems of greatest human concern, where methods of inquiry include “experience, trial and error, and intuition” (Schon, 1983, p.43), where research often “is more a craft than a slavish adherence to methodological rules” (Miles & Huberman, 1994, p. 5), and where epistemologies blur and methods must conform to the setting?

It is that conundrum that leads practitioners naturally to mixed methods where complementary approaches can accommodate scientific rigor and theory alongside uncertainty and instability. Knowledge obtained by such practical approaches is not pedestrian but particular (Sandelowski, 1996), and satisfies our disciplinary needs to improve individual clients’ daily lives.

There is a growing acceptance of the utility of mixed methods in addressing complex health problems among health science researchers (Forthofer, 2003) and, beginning with the use of triangulation in the 1980s, mixed methods have slowly gained ground in nursing (Twinn, 2003). Many other practice disciplines, both in and out of health sciences (e.g., architecture, law, engineering, social work, nutrition, medicine, education, business, agronomy, and epidemiology), also are fertile ground for mixed methods research. Mixed methods can nourish research in these disciplines through acknowledgment of the importance of context, recognition of both the particular and the general, identification of recurring patterns, development of insight into variation, seeking of multidimensional results that encompass both magnitude and lived experience, and achievement of neutrality balanced by advocacy (Greene, 2008). However, guidelines for mixed methods practice are needed; there is little conceptual or empirical work on choice of design and no widely accepted set of ideas about how to integrate data analyses or establish validity (Greene, 2008; Johnson & Onwuegbuzie, 2004). Moreover, very little is written about the role of an explicit conceptual or theoretical framework, as understood and utilized in nursing, to organize and guide the phases of inquiry in a mixed methods study.

Theoretical Frameworks as Organizing Structures

Morgan (2007, p. 68) posits, “We need to use our study of methodology to connect issues in epistemology with issues in research design, rather than separating our thoughts about the nature of knowledge from our efforts to produce it”. Therefore, one might argue that we can connect pragmatic research approaches with the need for a theoretical framework to assist in design of mixed methods studies.

Nursing often uses explicit theoretical frameworks from nursing or other disciplines as conceptual and organizational “hooks” upon which to “hang” a project (Sandelowski, 1999). Frameworks may assist in such things as research design, in terms of temporality (addressing past-present-future) or examination of a set of related constructs; in the development of “start codes” and themes; in the statement of propositions for future theory testing; and in utilitarian dissemination of results (Miles & Huberman, 1994). They provide an orderly, efficient scheme for bringing together observations and facts from separate investigations; assist in summarizing and linking findings into an accessible, coherent, useful structure; guide understanding of phenomena – both the what and the why of their occurrence; and provide a basis for prediction (Polit & Beck, 2004). Clearly, such frameworks could assist with navigation in mixed methods studies consisting of concurrent or sequential investigations, facilitate integration of methods in at least one phase of the inquiry, and provide a map for combining the what with the why to gain a multidimensional understanding of causal mechanisms. Utilization of such frameworks could, then, fit snugly into Tashakkori and Creswell’s recent definition of mixed methods: “Research in which the investigator collects and analyses the data, integrates the findings, and draws inferences using both qualitative and quantitative approaches or methods in a single study or program of inquiry” (2007, p. 4).

Use of Theoretical Frameworks in Extant Mixed Methods Studies

Creswell and Tashakkori, in a 2007 editorial, suggest that the aforementioned practice perspective is a pragmatic position from which we can observe how mixed methods research is actually used. If practice is thought to take the lead (Greene, 2008), are health science studies actually using theoretical frameworks to help guide complex mixed methods studies? Moreover, are these studies accessible to other researchers who seek to use them as models for their own work?

Mixed methods studies can be difficult to locate because the methodology is so new that many researchers fail to use consistent terms to describe their research. We found that we could use the search terms recommended by Creswell and Plano Clark (2007), however, to access these projects (“mixed method”, “mixed methods”, “mixed methodology“, “quantitative AND qualitative”, or “multimethod”). We anticipated that examining these resultant studies, drawn from the years 2004–2010 in CINAHL, Medline, PubMed, PsychInfo, and Social Sciences Index, for a priori theoretical frameworks would produce a significant number of articles for comparison. We did not include studies that generated a theory, only those that relied from the beginning on a theory for conceptual guidance. When we combined search terms, using “conceptual framework” or “theory” or “theoretical framework”, we could identify only 28 mixed methods articles that reported the use of an a priori theoretical framework as a conceptual lens to guide their studies. Although sometimes implicit, 21 of the studies used formal theories (those employing a group of tested or testable concepts or propositions), 4 integrated 1formal theory with another or with a concept such as role entrapment, while 3 used well-researched constructs such as loss and grief as a theoretical background. Of these 28, 11 came from the discipline of nursing; 10 of these used theoretical frameworks from other disciplines, pointing up the interdisciplinary nature of mixed methods. In seven studies, the theoretical framework was well-integrated in design, data collection, analysis, and discussion, although the specifics of the qualitative component were unclear in one project. In two other studies where the theoretical framework was partially integrated, qualitative components were omitted from the discussion or the article focused only on the qualitative approach. One study merely mentioned the theoretical framework but did not refer to it or its constructs again; there was virtually no integration of qualitative with quantitative methods. One was merely explication of a protocol that provided no discussion, although it employed a theoretical framework in design, sample, qualitative data collection and analysis. From these 11 studies, it appears that those with an explicit theoretical framework, threaded throughout the study, were more likely to integrate qualitative with quantitative data. If this is characteristic of nursing studies, then use of such a framework might go far to ensure integration, a crucial component of any mixed methods federal grant submission.

If there are a small number of articles available to guide mixed methods studies (found after much winnowing to determine whether or not a priori theoretical frameworks are used), researchers may not have readily accessible templates for conceptualizing their own work in these terms. Combine this potential lack of maps for accomplishing study aims with the necessary intricacy of design in such studies, and Schon’s “low, swampy ground” grows ever muddier. Add the qualitative tradition of a “black box” in regard to methodological detail, making it difficult for other researchers to follow an audit trail or replicate a study, and the task becomes less and less manageable.

The Utility of a Theoretical Framework in Guiding Momento Crucial

Pragmatically, then, how does a theoretical framework provide structure for a complex investigation of health behaviors, social determinants of health, or patient and family-focused health care, and facilitate translation of research findings into practice (Forthofer, 2003)? How might we utilize a framework to navigate the uncertainty in mixed methods and help answer our questions? To answer these questions, we will now present a study conducted in the discipline of nursing, Momento Crucial (“crucial moments in caregiving”) that illustrates the role of such frameworks in mixed methods studies.

Securing the Grant

First of all, establishing significance or impact of a proposed study is one of the most crucial aspects of grantsmanship. In our mixed methods study currently funded through the National Institute of Nursing Research, a theoretical framework was of incalculable worth during the search for funding because it provided a vehicle for discussing significance and innovation in methods, identification of gaps in research, and foreshadowing of project outcomes and future research plans. For example, we were able to say that use of “life course perspective” (our theoretical framework (Elder, 1995; 2003) enabled investigation of a previously untapped area, that is, the innovative, longitudinal, case- and variable-oriented study of Mexican-American caregiving families. Also, although there is very little extant literature in regard to positive outcomes of providing care even in Anglo families, we knew we would be able to explore those issues using the cultural and contextual components of with Mexican-American families. We also knew that our intensive case- and variable-oriented analysis would enable early detection of problematic transitions and turning points where family caregiving is threatened, and lead to future culturally-responsive, patient-centered, customized interventions to keep elders in their homes.

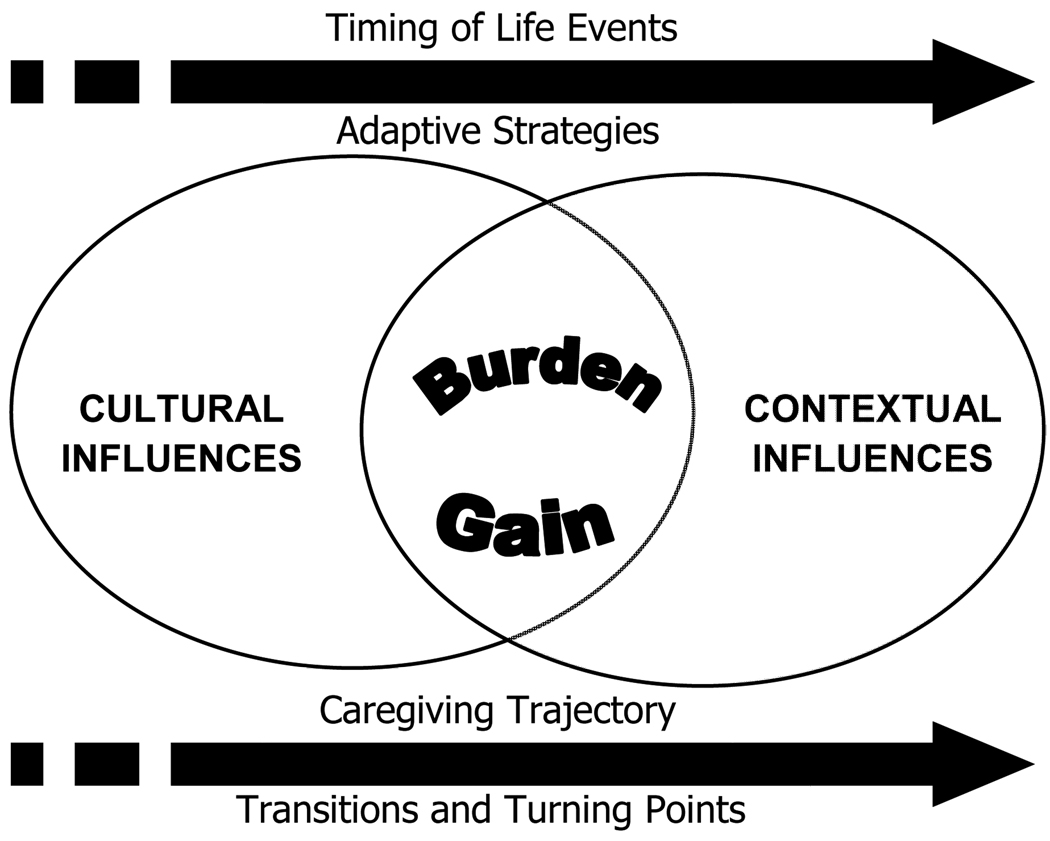

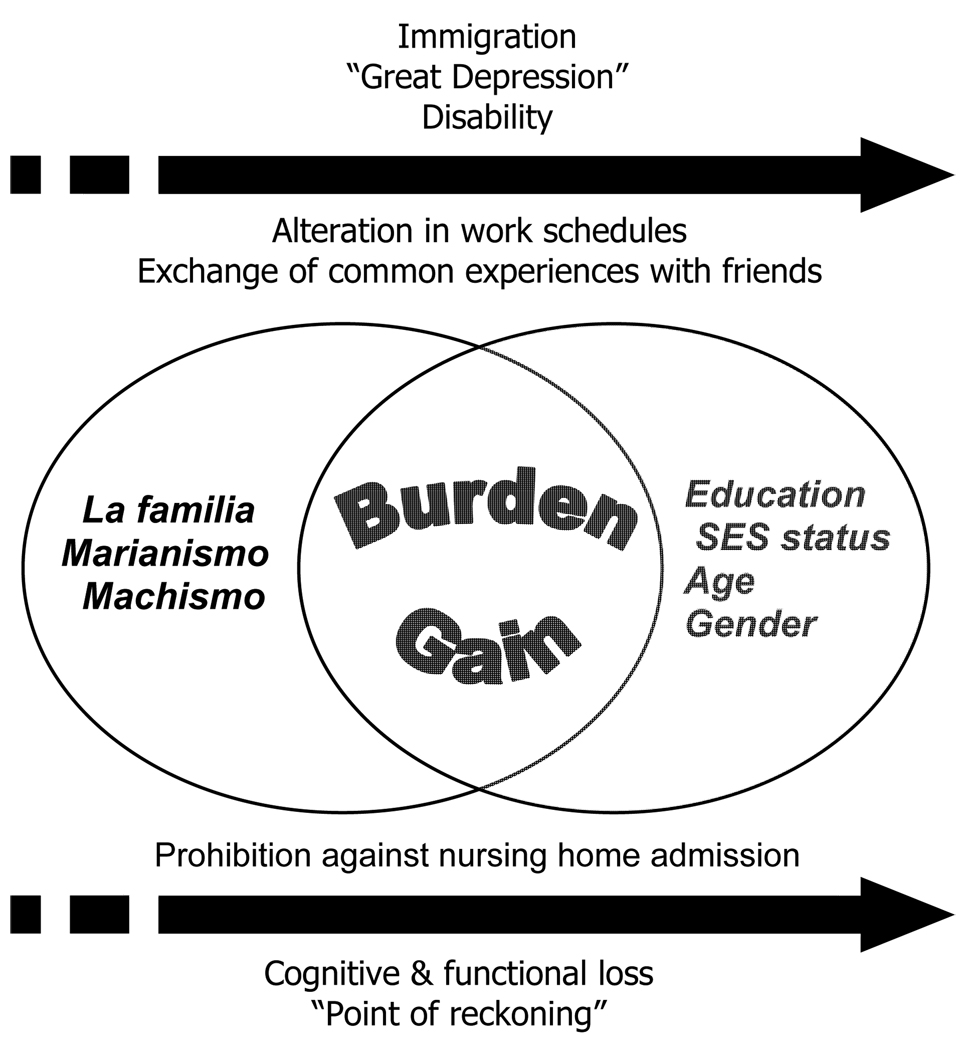

The original constructs of life course perspective from the discipline of sociology (Elder, 1995; 2003; Figure 1) were adapted for our inductively driven, multi-site study (Figure 2; Evans, Crogan, Belyea & Coon, 2009). Major constructs associated with life course perspective include trajectories, transitions, turning points, timing of life events, adaptive strategies, and cultural and contextual differences (Wethington, 2005; Pearce & Davey Smith, 2003; Settersten, 1999; Moen, 2003). In our study, the construct of “trajectory” became “caregiving trajectory” which develops over time in Mexican-American families. The constructs of “transition” and “turning point” became “caregiving transition”, a gradual alteration in social, job or family roles and responsibilities which can be incorporated into family life, and “caregiving turning point” where life is severely disrupted. “Timing of life events” developed into “timing of caregiving”: effects of immigration, economic crisis, or disability; “adaptive strategies” into “caregiving strategies”; and “cultural and contextual influences” such as age, gender, and socioeconomic conditions that shape the caregiving trajectory became “caregiving in la familia”.

Figure 1.

Life Course Perspective: Caregiving Trajectory.

Evans, B.C., Crogan, N.L., Belyea, M.J., Coon, D.W. (2009). The utility of the life course perspective in research with Mexican American caregivers of older adults. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 20(1), 5–14. Reprinted by permission.

Figure 2.

Life Course Perspective: Mexican-American caregiving families.

Evans, B.C., Crogan, N.L., Belyea, M.J., Coon, D.W. (2009). The utility of the life course perspective in research with Mexican American caregivers of older adults. Journal of Transcultural Nursing, 20(1), 5–14. Reprinted by permission.

Life course perspective’s particular strength is a set of powerful, cross-disciplinary organizing concepts that provide guidance for understanding the dynamic process of family caregiving of Mexican-American elders across time. The theory contains the key construct of temporality that permits true longitudinal study of transitions and turning points, in real time, in caregiving of Mexican-American families (Wethington, 2005) and allows integration of disparate explanations for differences in caregiver burden/strain and gain (Pearce & Davey Smith, 2003; George, 2003; Singer & Ryff, 1999). The use of life course perspective is consistent with an inductive approach because it fosters the collection of particular data directly from participants, allowing us to move from specific to abstract in our analytic moves (Sandelowski, 1996). It also promotes abduction because it creates a ready conduit between theory and data, allowing the researcher to move back and forth with ease (Morgan, 2007). Morgan advocates an inductive approach that first compares observation to theory and then evaluates the results of prior inductions through their predictive ability. For example, we observed that one son provided personal care for his mother, a cultural and contextual taboo (a life course perspective construct) for Mexican Americans. He did so using a matter-of-fact approach which we also observed in subsequent cases involving sons/mothers, allowing us to generate a predictive hypothesis for further testing: “MA males providing personal care for their mothers adopt a matter-of-fact approach as they act ‘against taboo’” (Evans, Belyea & Ume, 2011).

Study Aims and Mixed Methods Design

The aims of the study were to describe the level, circumstances, and consequences of caregiver burden/strain in Mexican American caregivers; determine the impact of cultural and contextual variables on caregiving in such families; and determine the events that lead to nursing home admission for older Mexican Americans. The core component of the study is a case-oriented approach which is an intensive, inductively-driven, study of cases with an eye toward configurations of similarities and differences. Using multiple measurements over time, a simultaneous, complementary, deductively-driven, variable-oriented component looks for broad patterns across cases and enable the drawing of inferences based on these broad patterns (Morgan, 1998; Ragin, 2000).

Because our conceptual process in this study is one of discovery, and our aims and research questions are answered predominantly by qualitative, case-oriented data, the theoretical drive is inductive (QUAL + quant; Morse & Niehaus, 2009). Theoretical drive addresses the supremacy of one paradigmatic approach, i.e., qualitative or quantitative, but does not constitute a theoretical framework because it is not a theory that can itself provide a conceptual lens for the study.

Given that this is an exploratory study in an area where little is known, collection of extensive rich qualitative data over time is emphasized, without which, data from standardized instruments would mean little. Consequently, the study uses a mixed methods design where the variable-oriented data occupy a secondary role to the case-oriented methodology (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2007). These two approaches are integrated throughout the analytic and interpretive phases of the study. Because the study is qualitative descriptive, it draws from the general principles of naturalistic inquiry (Sandelowki, 2000a), rather than a specific philosophical orientation, which may further strengthen the need for a guiding conceptual lens at the application level.

Research Questions

We used constructs drawn directly from life course perspective (Figure 2) to focus our inquiry. Examples of research questions include: What levels of burden/strain do family caregivers report over a 15 month period? What cultural and contextual circumstances are associated with caregiver burden/strain? What are the physical and emotional consequences of strain, as measured by caregiver description of transitions and turning points in the caregiving trajectory and the caregiver interview? To what degree are demographic variables such as socioeconomic status, age, and gender related to chronicity of caregiver burden/strain and caregiver gain? What family transitions and turning points in the caregiving trajectory are related to nursing home admission? To what degree are changes in caregivers’ capabilities and care recipients’ cognitive and functional status over time related to nursing home admission? Life course perspective helped us pose and answer our research questions because the theory itself contained the concepts of burden/strain, cultural and contextual variables, caregiving trajectory, and transitions and turning points.

Sampling

The temporal lens of life course perspective allowed us to stratify our cases in a purposeful sampling plan to examine the elapsed time of the intense, continuous, caregiving trajectory for each case (Sandelowski, 1999; 2000b). In order to capture the progression of events across the full trajectory, we enrolled 110 information-rich caregiver-care recipient cases into 1 of 3 groups: 1–12 months of caregiving, 13–24 months, and 25 months or longer. In this way, we are able to gain insight into the beginning of the continuous caregiving trajectory, although our major interest is on the “point of reckoning” when caregiving is recognized and accepted by the caregiver; the well-established caregiving trajectory with transitions and turning points; and the extended trajectory where nursing home admission may be contemplated.

The stratified purposeful sampling plan also was informationally representative (Sandelowski, 2000b), in that it included, and ensured case variation on, pre-specified variables such as the caregiver-care recipient relationship, gender, acculturation, function, and cognitive status. These constructs reflect cultural and contextual influences from our theoretical framework (Figure 2), which are defined as historical or individual events from childhood or young adulthood that shape the caregiving trajectory, and the cumulative advantages or disadvantages of socioeconomic status (years of education, current income and occupation), race, age, and gender (Elder, 1995; Elder, 2003; McDonough & Berglund 2003; Hertzman, 2004).

Recruitment

Even recruitment is tied to life course perspective in our IRB-approved study because we targeted agencies that serve Mexican-American families needing support with transitions and turning points in their caregiving trajectories. We used stories of these trajectories, told in telenovela style, as a culturally-appropriate, powerful recruitment tool in Spanish language media, including print, radio, and television. Additionally, we maintained our sample over the course of 15 months for each case through establishing warm personal relationships (personalismo: a requirement of effective interactions with Mexican American families; Evans, Coon & Crogan, 2007). We also referred families for assistance and made supportive phone calls or sent cards corresponding to identified transitions and turning points in their caregiving trajectories such as birthdays, funerals, and job loss or acquisition.

As recruitment progressed, we encountered a phenomenon not described in literature concerning Mexican American families, that of multiple caregivers and multiple care recipients living in a single household. We were challenged by these “collective caregivers” in terms of data collection and data analysis procedures, particularly for variable-oriented data, and had to decide whether to enroll them as more complex multiples or as cases consisting of only one caregiver and one care recipient. Reflecting back to our inductive theoretical drive, we decided to enroll them because, although they complicated our research protocol, they are an integral part of uncovering the phenomenon of caregiving in Mexican American families. Identification of “collective caregivers” also created an ethical issue in that we needed to seek additional IRB approval to cover the unanticipated increase in enrollment; while the number of cases (110) remained the same, we needed to enroll 20 additional participants, for a total of 240 instead of 220.

Mixed methods research is likely to confront ethical issues such as these due to the uncertainty and unpredictability of emergent designs and the necessity of facing moral challenges in the field (Hesse-Biber, 2010; Mcfarlane, 2010). We had no issues with compromising confidentiality in subsequent phases of the research because we used a concurrent design, or indirectly linking data in the public domain to locate a target sample because we recruited chiefly by word of mouth. We do continue to carefully monitor issues of informed consent in secondary analyses, many of which will spring from our large, complex data set, and consonant with our transformative philosophy, we make a conscious effort to understand and value the stories of our caregiving families.

Data Collection

Demographics

Our theoretical framework led us to look at the context of families’ immigration and educational experiences, along with socioeconomic status, as part of cultural and contextual influences. We used a demographic questionnaire and the General Acculturation Index to collect those data.

Case-oriented data

The concept of time from life course perspective appeared in our study both as “clock time” associated with caregiving events and as “personally, socially and culturally constructed” time, expressed in caregiver narratives (Sandelowski, 1999, p. 81) elicited through interviewing. “One of the most common and most powerful ways to understand our fellow human beings” (Fontana & Frey, 1998, p. 47), interviewing has long been the gold standard for naturalistic data collection and is used widely in the health and social sciences. In keeping with the cross-disciplinary approach of life course perspective, we derived caregiver interview questions from literature in nursing, anthropology, and the socio-behavioral sciences. Open-ended questions such as, “How does being Mexican-American influence your caregiving?” elicited information about components of life course perspective such as immigration and socioeconomic status, and assisted in exploration of the caregiving trajectory.

In order to trace transitions and turning points, caregivers completed a trajectory timeline at each visit. The purpose of the timeline was to visually augment data about the caregiving experience derived from the interview on contiguous series of 8½” × 11” sheets of paper marked with a horizontal life course line, with the left end representing the start of the caregiving trajectory, progressing toward the right end across time. Using questions from a protocol based on life course perspective, we defined terms and asked caregivers to recall transitions, turning points, and adaptive strategies, indicating them on the timeline. Caregivers choose the start date of the trajectory, naming events that later influenced care and their dates, so that researchers could further explore and understand culturally and socially constructed notions about transitions and turning points (Scanlon-Mogel & Roberto, 2004).

Variable-oriented data

To support our case-oriented approach, we collected data on variables from the theoretical framework (Figure 2) such as burden/strain (Zarit Burden Interview, Penn State Worry Questionnaire, General Well-Being; Caregiver Vigilance Scale) and cognitive, mood, and functional status as it affects burden/strain (CLOX, Katz Activities of Daily Living, Lawton Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; Geriatric Depression Scale, Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression). Relying once again on the temporal dimension, we completed equivalent standardized measures with both caregiver and care recipient across the 15 months of their participation in the study, juxtaposing them with concurrent transitions and turning points identified in interviews and trajectory timelines.

Life course perspective also provided an opportunity for us to quantify the breadth and depth of data collection over time for other researchers. We can confirm that we tapped multiple dimensions of the caregiving trajectory as shown in Figure 2, penetrating each case deeply and generating well over 550 hours of data collection based on semi-structured interviewing.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Understanding the caregiving phenomenon in Mexican-American families requires data reduction that does not obscure it with too much detail (Sandelowski, 1993a), despite the use of complex, mixed methods. Life course perspective aids in this endeavor by focusing the researcher on relevant constructs and their interrelationships; we use it as a series of chronological hooks upon which to hang sequential and concurrent events in time (Sandelowski, 1999).

Brief summary of the analytic and interpretive process

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy. A manual of “start codes” derived from life course perspective, enabling initial examination of the data, was revised and tested across 60 cases, and was considered complete when no additional new codes could be identified. Inter-rater agreement was established at the 90% level among the research team (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Data were coded as collected and entered into Atlas.ti. Themes were identified according to exemplars and definitions in the coding manual, frequencies tallied on data displays, and clustered. Themes were also identified in the timeline drawings and tallied.

Demographic and variable-oriented data were collected and entered into SPSS. Statistical operations were used to clarify and support case-oriented data as needed. For example, we used latent class analysis to calculate differences in distress across time in caregiving trajectories and plotted results of standardized instruments over time for comparison with themes identified in interviews and timelines in a comparative case study of two sons providing care for their mothers. We also created a series of matrices reflecting constructs from life course perspective, such as burden/strain, where case- and variable-oriented data could be displayed together to enable such comparisons.

Details of the analytic and interpretive process: Relationship to theoretical framework

Viewing the interviews and trajectories as narratives, we identified relationships among social and cultural phenomena that exert strong influences over caregivers because they are construed in common ways (Patton, 2002). We relied on congruency of our research design with life course perspective as a guiding framework to tackle the maze of mixed methods. Beginning with the coding manual for case-oriented analysis, the constructs of life course perspective formed the basis for “start codes” (Miles & Huberman, 1994): preliminary cultural domains and associated themes, with definitions and exemplars, which were refined as data reduction proceeded and entered into ATLAS.ti.

Our analysis emphasized the descriptive/exploratory phase of inquiry, identifying the full spectrum of transitions, turning points, and adaptive strategies and their influence on caregiver burden/strain and its consequences. We identified and described critical transitions and turning points with accompanying burden/strain associated with each caregiving trajectory such as marriage, birth of children, and children leaving home, along with changes in health, divorce or widowhood.

The case-oriented component, the core of the study (QUAL + quant), robustly adds to the theoretical and pragmatic understanding of Mexican American families. As we coded the 660 interviews using a manual derived from the constructs of life course perspective (described above), new themes emerged that enriched the theoretical framework. Some of these themes validated the sparse caregiver literature, such as the notion of a “reckoning point” (life course perspective: caregiver turning point; Clark & Huttlinger, 1998), the first recognition and acceptance of the role of caregiver, which we heard commonly expressed by Mexican American families. Speaking of her assumption of the caregiving role, one young woman reported,

My brother was watching [my parents] at his house but he started leaving them more and more. I said, “You have to watch them more. They’re getting older and you can’t leave them alone.” So I finally said, “No, just forget it” [and I took them in].

Another caregiver rejoiced in the progress made by his mother since she came to live with him (life course perspective: caregiver gain). He recounted the rewards, or caregiver gain (Giunta, Chow, Scharlach & Dal Santo, 2004) of caring for her: “She washes herself, she combs her hair, things of that nature. Everything has improved, all I see is improvement, improvement, improvement, and that’s all I care about.” Yet another caregiver spoke eloquently about the familial and moral obligation in Mexican American families to unconditionally reciprocate for care from parents or grandparents (Clark & Huttlinger, 1998).

When you were little, your parents changed your diapers so now that they are older, it’s up to you to take care of them. You needed from them when you were growing up and now they need from you – that’s how we honor them.

Other themes recognized in our study were either absent from, or superficially described in, the literature. For example, we found Mexican American sons providing personal care for their mothers, a previously undescribed occurrence (life course perspective: cultural and contextual/caregiving in la familia). A verbatim exemplar from this phenomenon is presented below under “credibility” (Evans, Belyea & Ume, 2011). Also, the phenomenon of “collective caregiving” (life course perspective: cultural and contextual/caregiving in la familia) is a new addition from our study to the literature. Although the Mexican American family as a group providing care for an older relative is not an unknown notion, there is a lack of empirical detail about this adaptive caregiving strategy. In the process of identification and exploration of this poorly-researched phenomenon, we uncovered three components of “collective caregiving” (it should be noted that we define a “primary” caregiver as one who provides help with two or more activities of daily living).

“Communal caregiving”: a single primary caregiver provides care to more than one care recipient. For example, a single primary caregiver of her mother- and father-in-law reports, “Eight years ago, my husband said, ‘My parents are going to come and live with us’, so I had no choice. [I felt] good and then bad because I’ve never lived with my husband and my kids, [alone]”. Sometimes more than one primary caregiver provides care to a single care recipient. For instance, a caregiving daughter and her son both act as primary caregivers for Tata (Grandfather) and her other son comes over to help when he can. “We tag team it between all three of us. Since I can’t lift him off the bed, one of my sons will sit him in the wheelchair to bring him in to eat.”

- “Consecutive caregiving”: a caregiver provides care for one family member after another.[My wife’s mother] just passed away. She had Alzheimer’s…we spent a lot of time with her. [My wife] would go on her lunch hour and stuff like that. It’s my mother [needing care] now and that was a big decision I had to make….my wife fell in right along beside me.

“Chain reaction caregiving”: a primary caregiver becomes temporarily unable to meet the demands of caregiving, and must rely on someone else to provide care for a period of time. After knee surgery, one caregiver was obliged to step down from care, allowing a spouse and son to take over temporarily. The spouse struggled to meet the care recipient’s needs, saying “With her hurting and everything, she’s just like Jell-O. She’s no help at all. If my son weren’t here, I wouldn’t be able to take care of her without getting hurt myself.” In this particular case, a second caregiver was at risk of being overwhelmed with the demands of caregiving and a third was needed.

Taking advantage of the complementary relationship between case- and variable-oriented approaches (Ragin, 2000), we combined interview and trajectory timeline data with scores on standardized measures. We accomplished this by quantizing some of the qualitative data about transitions, turning points, and themes identified in the case oriented analyses reduction (Borkan, 1991; Elliott, 2005; Happ et al., 2006; Miles & Huberman, 1994; Sandelowski, 2000b). Quantitizing, defined as the process of assigning numerical values to non-numerical data, enables the transformation and merging of data sets and therefore, qualifies as mixed methods (Sandelowski, 2000b; Sandelowski, Voils, & Knafl, 2009).

The quantitizing process also was guided by the theoretical framework as we looked across constructs to identify important comparisons. When needed, we converted case-oriented interview data into items, ranks, scales, or concepts that could be represented numerically to facilitate comparison with variable-oriented data. For example, we created dummy codes for categorical variables such as membership or non-membership in a group of caregivers where nursing home admission was triggered by the “turning point” of assaultive behavior (identified in data from interviews and caregiving trajectory drawings). Dummy codes for different types of “turning points” could be subjected to analysis to study their effects on admitting care recipients to nursing homes. Simple frequencies also provided additional insights, such as the number of times caregivers mentioned “burden”, “obligation”, or “duty”, or how many times a particular “turning point” occurred across caregivers. Such numerical information could then be directly compared to data from standardized measures addressing these constructs.

Following procedures as outlined in Happ et al. (2006) for case-oriented analyses, we are now in the preliminary stages of plotting all data collected from each of the 110 cases over time, showing central themes from all interviews and scores from all measures for each of the 6 data points. For example, in Table 1, case-oriented data (Mrs. Macias and her 32 year-old caregiving daughter) will be quantitized by dichotomizing transition categories (caregiver pregnancy: 0 [no] or 1 [yes]; caregiver marriage: 0 [no] or 1 [yes]) and turning points (birth: 0 [no] or 1 [yes]) for comparison with variable-oriented data (Zarit Burden Index, Caregiver Vigilance Scale, CLOX, Activities of Daily Living/Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scales). Table 1 is a simplified example of a matrix that could be used as a basis for such comparisons, where CG stands for “caregiver” and CR stands for “care recipient”.

Table 1.

Quantitized constructs from life course perspective compared to scores on standardized measures.

| Case | Transition | Turning Point |

CG Adaptive Strategy |

CG Zarit |

CG CVS |

CG/ CR CLOX |

CR ADL |

CR IADL |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mrs. Macias, CG is daughter, age 32 |

CG Pregnancy 0 1 CG Marriage 0 1 |

Birth 0 1 |

Sister stayed for 6 wks |

28 | 27h/ week |

5/2 | 4 | 2 |

Matrices such as Table 1 allow us to construct a summary profile of each case and to discern which cases can be clustered together, based on commonalities. Theoretical typologies of cases will then be constructed, in terms of the concepts from life course perspective. Using the results of both the case- and variable-oriented analyses, we will map two typologies: one for caregiver burden/strain and one for caregiver gain or rewards, in relation to trajectory events. It is expected that we will be able to distinguish different social and cultural factors influencing caregiving trajectories and nursing home admission within these typologies, define distinct categories of change in caregiving, and describe patterns for families who continue to provide informal care as compared to those who do not. Such typologies could provide a future basis for rapidly assessing caregiving phases and identifying effective interventions for families undergoing particular caregiving burdens and strains.

Data reduction procedures throughout our study rely on the life course perspective emphasis of temporality. For example, we will compare each case in the early phase of caregiving group with every other case in that group; compare each case in the middle and late phases with every other case in its respective group; and compare all cases in the early phase of caregiving group with all the cases in each of the two other caregiving groups. In another example, we utilize a matrix to enter the sequence of transitions, turning points, and adaptive strategies identified in interview data and trajectory timelines across cases, adding caregivers’ and care recipients’ scores on standardized measures across time points. We then split the matrix into two sections, separating cases according to outcomes of (1) continuing informal community care and (2) nursing home admission so that transitions, turning points, and adaptive strategies can be compared/contrasted within each section and then across sections.

Credibility and Future Research

Using the theoretical framework of life course perspective, we elicit stories from participants and examine them carefully for elements of the caregiving trajectory, staying close to the data and working at lower levels of interpretation, as befits a qualitative descriptive study (Sandelowski, 2000a). And, although life course perspective is central to the way our research is conducted, it is peripheral to our target phenomenon of caregiving in Mexican American families, allowing participants’ voices to reverberate throughout our re-presentation of data, increasing credibility (Sandelowski, 1993b). For example, in our case study of two Mexican American males providing personal care for their aged mothers (Evans, Belyea & Ume, 2011), we reported one man’s approach to cleaning and changing his mother after a bowel movement. “It’s just like cleaning a baby, it’s the same thing”, he said. “You just have to learn to breathe differently.”

There will be some opportunity for statistical generalization of quantitative data results, based on multilevel modeling, during the initial analytic phase before the two data sets are combined. However, the use of the case-oriented approach will, primarily, make possible logical or case generalizations, as opposed to statistical generalization. Returning to the constructs from life course perspective, we use these generalizations to generate working hypotheses for further testing in the next phase of our inquiry. In an effort to increase utilization/application of our findings for other researchers, we attempt to enhance external validity/transferability/fittingness by attending to congruency with life course perspective theory, considering cultural and linguistic accuracy in translation and interpretation, and making the findings intellectually accessible to other researchers by working iteratively between life course perspective and thorough, specific, detailed descriptions of data collection and analytic procedures. Such descriptions will enable confirmability/objectivity of the research by demonstrating neutrality in interpretations. Given these details (carefully traced through audit trails [raw data, analysis notes, reconstruction and synthesis products, process notes, and personal notes] kept during the study and presentation of verbatim data), other researchers can estimate the quality of our data, the suitability of our analytic strategies, and the trustworthiness of our conclusions for themselves.

Conclusions

Given practical examples concerning the use of a theoretical framework in the study described above, can we say that such a framework is a methodological necessity in mixed methods studies across practice disciplines? Are there limits to its utility?

Speaking in favor of theoretical frameworks, one might argue that the need for creative and efficient ways of implementing mixed methods studies will only grow as the utility of the approach becomes increasingly clear. We will need logical guidance for intricate studies that determine not only behavior change from an intervention, but also identify factors that influence such changes and provide rapid, indirect measurements of population-level indicators when interventions must be implemented at the individual level and evaluation of direct, long-term outcomes take time (Forthofer, 2003).

Researchers increasingly confront a multiplicity of ecological factors which can be difficult to operationalize (Forthofer, 2003). For example, direct measurement of macro-level factors is not always feasible, leading to critical decisions about study scope, for example, in terms of neighborhood vs. metropolitan area and which of multiple ecologies to measure, but multilevel mixed methods can be used to sustain those decisions. Such complexities are difficult to put into practice and to manage for even the most seasoned research teams, especially in longitudinal or multi-site studies, if an organizing structure with a good “fit” to the study is not readily apparent.

Theoretical frameworks can provide navigational devices through the “low, swampy ground” of practice disciplines in studies concerning complex human behaviors that invite multiple, relevant, complementary perspectives and methods of investigation that take into account the importance of causal mechanisms. Acting as maps, theoretical frameworks can help researchers return home to aims/research questions after forays into triangulation seeking convergent validity and facilitate identification of the next path to explore. Tightly tying all phases of the research process to a theoretical framework automatically provides a theory-based result, increases credibility, and fosters transferability to practice settings.

All methods and techniques, however, have limitations. Theory “fit” the data when it permits comparisons to its components and offers an organizing framework for re-presentation of data. Without careful consideration, a theoretical framework could be chosen that has a poor “fit” with the study, distorts the data, or fails to describe the reality under study (Sandelowski, 1993b; 2000b). Also, researchers must remember to stay grounded in the data and remain open to the possibility that, ultimately, the data and the framework may be incompatible. In Momento Crucial, extensive preliminary work with Mexican American caregiving families and a theory derivation exercise that adapted life course perspective specifically for working with this population made incompatibility highly unlikely. Rather than limiting the study, the theoretical framework was critical to the design (as a theoretical framework is for all studies, according to Hesse-Biber, 2010) because it provided a guiding structure that kept the study well-bounded but did not preclude discovery.

The call has gone out for practice disciplines to use more fully the full armamentarium of concepts, techniques, and terminology associated with mixed methods in order to manage the increasing complexity of research (Twinn, 2003). Based on our experience with Momento Crucial as described in this paper, this armamentarium can be buttressed by a theoretical framework, whether the theoretical framework constitutes the theory of the problem, as in our current descriptive study, or the theory of the intervention, as in our future study. For example, the next phase of this inquiry will be an intervention to support Mexican-American families in their efforts to care for older family members at home. In that study, evaluation of our intervention effectiveness must take into account the fidelity and integrity of the intervention and reflect complex caregiving situations in order to develop clinically relevant knowledge (Sidani & Braden, 1998). We will need to rely on a theoretical framework to understand its effects because the framework, “specifies the nature of the intervention, the nature of the effects expected, the processes mediating the expected effects, and the conditions under which the mediating processes occur” (p. 12). Without the theoretical framework, set within the context of mixed methods to capture complexity, we would find it difficult to determine causal mechanisms, rely on generalizability to other populations, or establish clinical significance of intervention effects. Our advice is, “Don’t leave home without one!”

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health [grant number 5R01NR010541-02]

Contributor Information

Bronwynne C. Evans, College of Nursing & Health Innovation, Arizona State University, 500 N. Third St., Phoenix, Arizona 85003, Phone: (602) 496-0766, Fax: (602) 496-0886, bronwynne.evans@asu.edu.

David W. Coon, College of Nursing & Health Innovation, Arizona State University.

Ebere Ume, College of Nursing & Health Innovation, Arizona State University.

References

- Borkan J, Quirk M, Sullivan M. Finding meaning after the fall: Injury narratives from elderly hip fracture patients. Social Science & Medicine. 1991;33:947–957. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90265-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark M, Huttlinger K. Elder care among Mexican American families. Clinical Nursing Research. 1998;7(1):64–81. doi: 10.1177/105477389800700106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J. Qualitative inquiry and research design. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J, Plano Clark V. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell J, Tashakkori A. Differing perspectives on mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2007;1(4):303–308. [Google Scholar]

- Elder G. The life course paradigm: Social changes and individual development. In: Moen P, Elder G, Luscher K, editors. Examining lives in context. Washington DC: American Psychological Association; 1995. pp. 101–139. [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH., Jr . The emergence and development of life course theory. In: Mortimer E, Shanahan M, editors. Handbook of the life course. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003. pp. 3–19. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott J. Using narrative in social research: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. London: Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Evans BC, Belyea M, Ume E. Mexican American males providing personal care for their mothers. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2011 doi: 10.1177/0739986311398615. 0739986311398615, first published on March 18, 201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans B, Coon DW, Crogan N. Personalismo and breaking barriers: Accessing Hispanic populations for clinical services and research. Geriatric Nursing. 2007;28(5):289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2007.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans B, Crogan N, Belyea M, Coon DW. Utility of the life course perspective in research with Mexican American caregivers of older adults. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 2009;20(1):5–14. doi: 10.1177/1043659608325847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana A, Frey J. Interviewing: The art of science. In: Denzin N, Lincoln Y, editors. Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. pp. 47–78. [Google Scholar]

- Forthofer M. Status of mixed methods in the health sciences. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, editors. Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. pp. 527–540. [Google Scholar]

- George LK. Life course research: Achievements and potential. In: Mortimer J, Shanahan M, editors. Handbook of the life course. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2003. pp. 671–680. 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Giunta N, Chow J, Scharlach A, Dal Santo T. Racial and ethnic differences in family caregiving in California. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 2004;9(4):85–109. [Google Scholar]

- Greene J. Is mixed methods social inquiry a distinctive methodology? Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2008;2(1):7–22. [Google Scholar]

- Guba E, Lincoln Y. Do inquiry paradigms imply inquiry methodologies? In: Fetterman DM, editor. Qualitative approaches to evaluation in education. 1988. pp. 89–115. [Google Scholar]

- Happ M. Mixed methods in gerontological research: Do the qualitative and the quantitative data “touch”? Research in Gerontological Nursing. 2009;2(2):122–127. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20090401-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happ M, Dabbs A, Tate J, Hricik A, Erlen J. Exemplars of mixed methods data combination and analysis. Nursing Research. 2006;55(2S):S43–S49. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200603001-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzman C. The life-course contribution to ethnic disparities in health. In: Anderson N, Bulatao R, Cohen B, editors. Critical perspectives in racial and ethnic differences in health in late life. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press; 2004. pp. 145–170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse-Biber S. Mixed methods research. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R, Onwuegbuzie A. Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educational Researcher. 2004;33(7):14–26. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson R, Onwuegbuzie A, Turner L. Toward a definition of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2007;1(2):112–133. [Google Scholar]

- Mcfarlane B. Values and virtues in qualitative research. In: Savin-Baden M, Howell Major C, editors. New approaches to qualitative research. New York, NY: Routledge; 2010. pp. 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- McDonough P, Berglund P. Histories of poverty and self-rated health trajectories. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2003;44(2):198–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles M, Huberman A. Qualitative data analysis. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Moen P. It's about time: Couples and careers. ILR Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D. Practical strategies for combining qualitative and quantitative methods: Applications to health research. Qualitative Health Research. 1998;8(3):362–376. doi: 10.1177/104973239800800307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan D. Paradigms lost and pragmatism regained: methodological implications of combining qualitative and quantitative methods. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2007;1(1):48–76. [Google Scholar]

- Morse J, Niehaus L. Mixed method design. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. Qualitative research and evaluation methods. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce N, Davey Smith G. Is social capital the key to inequalities in health? American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(1):122–129. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.1.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polit D, Beck C. Nursing research: Principles and methods. 7th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ragin C. Fuzzy-set social science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Rigor or rigor mortis: the problem of rigor in qualitative research. Advances in Nursing Science. 1993a;16(2):1–8. doi: 10.1097/00012272-199312000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Theory unmasked: The uses and guises of theory in qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health. 1993b;16:213–218. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770160308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. One is the liveliest number: The case orientation of qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health. 1996;19:5235–5529. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199612)19:6<525::AID-NUR8>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Time and qualitative research. Research in Nursing & Health. 1999;22:79–87. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-240x(199902)22:1<79::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health. 2000a;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M. Combining qualitative and quantitative sampling, data collection, and analysis techniques in mixed-methods studies. Research in Nursing & Health. 2000b;23:246–255. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200006)23:3<246::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M, Voils C, Knafl G. On quantitizing. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2009;3(3):208–222. doi: 10.1177/1558689809334210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlon-Mogel JM, Roberto KA. Older adults' beliefs about physical activity and exercise: Life course influences and transitions. Quality in Ageing. 2004;5(3):33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Schon D. The reflective practitioner. New York: Basic Books; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Schon D. Educating the reflective practitioner. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Settersten RA. Lives in time and place: The problems and promises of developmental science. Baywood Pub.; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sidani S, Braden C. Evaluating nursing interventions: A theory- driven approach. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Singer B, Ryff CD. Hierarchies of life histories and associated health risks. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1999;896:96–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb08108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori A, Creswell JW. Exploring the nature of research questions in mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research. 2007;1:207–211. [Google Scholar]

- Tashakkori A, Teddlie C. Mixed methodology: Combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Teddlie C, Tashakkori A. Major issues and controversies in the use of mixed methods in the social and behavioral sciences. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, editors. Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. pp. 3–50. [Google Scholar]

- Twinn S. Status of mixed methods research in nursing. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, editors. Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2003. pp. 541–556. [Google Scholar]

- Wethington E. The life course perspective on health: Implications for health and nutrition. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior. 2005;37:115–120. doi: 10.1016/s1499-4046(06)60265-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]