Abstract

TNF-family molecules induce the expression Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) in endothelial cells (EC) and elicit signaling responses that result in angiogenesis. However, the role of TNF-receptor associated factors (TRAFs) as upstream regulators of VEGF expression or as mediators of angiogenesis is not known. In this study, HUVEC were cotransfected with a full-length VEGF promoter-luciferase construct and siRNAs to either TRAF 1–6, and promoter activity was measured. Paradoxically, rather than inhibiting VEGF expression, we found that knockdown of TRAF6 resulted in a 4–6 fold increase in basal VEGF promoter activity compared to control siRNA-transfected EC (P<0.0001). In addition, knockdown of TRAF 1, -2, -3 or -5 resulted in a slight increase or no change in VEGF promoter activation. Using [3H]thymidine incorporation assays as well as the in vitro wound healing assay, we also found that basal rates of EC proliferation and migration were increased following TRAF6 knockdown; and this response was inhibited by the addition of a blocking anti-VEGF antibody into cell cultures. Using a limited protein array to gain insight into TRAF6-dependent intermediary signaling responses, we observed that TRAF6 knockdown resulted in an increase in the activity of Src family kinases. In addition, we found that treatment with AZD-0530, a pharmacological Src inhibitor, reduced the regulatory effect of TRAF6 knockdown on VEGF promoter activity. Collectively, these findings define a novel pro-angiogenic signaling response in EC that is regulated by TRAF6.

Keywords: Endothelial Cell, VEGF, Angiogenesis, Inflammation, Signal Transduction

INTRODUCTION

Angiogenesis, the generation of new blood vessels from pre-existing ones, is characteristically associated with cell-mediated immune responses and is a well-established pathological component of many chronic inflammatory diseases [1]. However, surprisingly little is known about mechanism(s) whereby the immune response results in the induced expression of angiogenesis factors and/or endothelial cell (EC) proliferation and migration. Previous studies, including ours, have shown that proinflammatory stimuli such as TNFα and CD40-induced signaling mediate the expression of the potent angiogenesis factor Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) in EC and other cell types [2,3,4,5,6,7]. In addition, CD40-induced pro-angiogenic responses in EC function in cell-mediated immunity [2,8] and are critical for EC proliferation in association with tumor angiogenesis in vivo [4,5].

TNF family receptors recruit members of the TNF-receptor associated factor (TRAF) family in order to elicit signaling events [9,10,11,12,13]. The six TRAF family members (called TRAF1 through -6), are characterized by a conserved C-terminal domain that mediates association with the TNF receptor family [14,15], and all TRAFs, except TRAF1, contain Ring finger and Zinc finger domains that function to elicit downstream signaling events. The cytoplasmic domain of CD40 contains a proximal TRAF6-binding domain and a distal TRAF2/3/5-binding domain [9]. The TNFα receptor TNFR1 binds TRAF2 indirectly, through the recruitment of TNFR1-associated death domain protein (TRADD) [16], while TNFR2 binds TRAF2 directly [17]; it is suggested that TRAF5 can substitute for TRAF2 in TNFα-induced signals [18]. TRAF1 has been shown to bind the same sites than TRAF2 on TNFR1, TNFR2 and CD40, and is thought to act as a regulator of TNFα and CD40-induced signals [13,19]. TRAF4, while structurally related to the other TRAFs, localizes to the cell nucleus and is unable to bind to the TNFα receptors and CD40 [20]. Therefore, CD40- and TNFα-induced responses are likely associated either with a TRAF2/5 and/or a TRAF6-mediated signaling response. However, no study to date has identified roles or functions for TRAFs in VEGF expression or in the angiogenesis response.

In these studies, we have used a knockdown approach to identify whether TRAF-mediated signals in EC function for VEGF expression and/or EC migration and proliferation. While we find some redundancy in TRAF1-, 2-, 3- and 5- dependent signaling responses, paradoxically, we observe that TRAF6 is a potent regulator of basal as well as the inducible expression of VEGF in EC. In addition, we find that TRAF6 serves as an endogenous inhibitor of EC proliferation and EC migration, and its ability to regulate angiogenesis is in part associated with interaction(s) with Src family kinases. Collectively, these studies identity TRAF6 as a critical factor in the regulation of pro-angiogenesis signaling in EC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Antibodies and Reagents

For Western blotting, anti–phospho-Akt (Ser473) and anti-phospho-Src (Tyr416) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA), and anti-TRAF1, -TRAF2, -TRAF3, -TRAF5, -TRAF6 and anti-VEGF were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). β-actin and GAPDH antibodies were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Soluble CD40L was purchased from Ancell (Bayport, MN) and AZD-0530 was purchased from LC Laboratories (Woburn, MA). Neutralizing anti-human VEGF antibody used in cell culture was gifted by Genentech (South San Francisco, CA).

Cell culture

Single donor human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVEC) purchased from Clonetics (Walkersville, MD) were cultured in complete endothelial growth medium (EGM-2 BulletKit; Clonetics), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

siRNA Knockdown

Validated small interfering RNAs (siRNA) for TRAF1, TRAF2, TRAF3, TRAF5, TRAF6 and control siRNA were purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). Transfection of HUVEC with each siRNA (50nM) was performed using RNAimax lipofectamine (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Knockdown efficiency was tested by Western Blot analysis for each experiment.

Promoter-Reporter assay

A VEGF promoter-luciferase construct containing the 2.6 kb full-length VEGF promoter (gifted by Debabrata Mukhopadhyay, Mayo Clinic, Minneapolis, MN) was used as described [8,21].

Real-time PCR

Total mRNA was isolated from HUVEC using the RNeasy isolation kit (Qiagen) and used as a template to generate cDNA using random primers (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR analysis of human VEGFA and GAPDH was performed using the 7300 real-time PCR system and specific TaqMan® Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Relative expression was calculated according to the 2−ΔΔCt method, as described [22].

Western blot analysis

HUVEC were lysed with ice-cold RIPA buffer (Boston Bioproducts), run on SDS–polyacrylamide gels, and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA). Membranes were blocked with 5% BSA for 1 hour and incubated overnight with primary antibody. After three washes, membranes were incubated with a species-specific secondary peroxidase-conjugated antibody for 1 hour, and reactive bands were developed by chemiluminescence (Thermo Fisher Scientific-Pierce, Rockford, IL).

Cell proliferation assay

HUVEC were seeded onto 96-well cell culture plates (5000 cells per well), transfected with siRNAs, and cultured for 72 hours. Proliferation was assessed by [3H] thymidine incorporation (0.5 μCi/well) in the final 16 hours of cell culture, using a Tomtec automated cell harvester (Hamden, CT).

In vitro migration

Migration of EC was evaluated using the in vitro wound-healing assay. Briefly, HUVEC were transfected either with control or TRAF6 siRNA, and cultured for 48 hours. At this time, a linear wound was created in the cell monolayer using a pipette tip. Groups of cells (in triplicate) were cultured for an additional 18 hrs in the absence or presence of a neutralizing anti-VEGF antibody (10μg/ml), and migration of cells into the wound was monitored by microscopy.

Phospho-kinase array

Phospho-kinase arrays were performed using the Human Phospho-Kinase Array Kit (Proteome Profiler™ Array) from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analysis was performed using the student t test for two groups of data or by one-way ANOVA for three or more groups. P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The TRAF family of adaptor proteins regulate the endogenous expression of VEGF

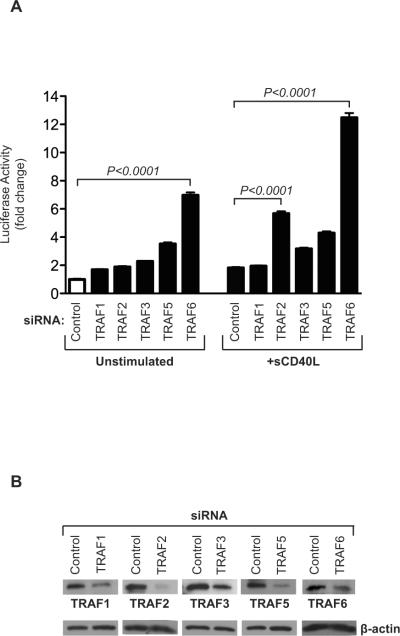

It is well established that most cell types, including EC [23] express TRAF family molecules. Furthermore, the expression of individual TRAFs, notably TRAF1 in EC can be regulated by different cytokines, especially following ligation of CD40 by sCD40L [23]. This observation indicates that individual TRAFs have potential to function as adaptors to initiate signals that result in EC proliferation. We initially wished to determine the function of individual TRAF adaptor molecules in the expression of VEGF. EC were transfected either with siRNAs to TRAF1, -2, -3, -5 or -6 or with a control siRNA, and were co-transfected with a full-length VEGF promoter-luciferase reporter construct. Following co-transfection, EC were cultured for 48hrs in the absence or presence of sCD40L. Paradoxically, rather than inhibiting VEGF expression, we found a generalized increase in VEGF transcriptional activation following transfection of EC with each TRAF siRNA as compared to control (Figure 1A). Moreover, while the effect of TRAF1, -2, -3 and -5 was modest, TRAF6 knockdown resulted in a marked induction of basal levels of VEGF expression (P<0.0001). Also, and consistent with our previously published studies [2,8,21,24], we found that the treatment of EC with sCD40L resulted in a 2-3-fold increase in VEGF transactivation. However, following activation, there was a greater increase in VEGF promoter activity in EC transfected with siRNAs to TRAF2 (approx. 6 fold induction, P<0.0001) and TRAF6 (approx.12 fold induction, P<0.0001) compared to control siRNA-transfected EC. Following activation, VEGF promoter activity was also increased in cells transfected with siRNAs to TRAF3 and TRAF5, but levels of expression were more modest. Thus, TRAF6 is a negative regulator of both endogenous as well as inducible expression of VEGF in EC, while other TRAFs, notably TRAF2, function more selectively as regulators following activation.

Figure 1. Effect of TRAF knockdown on basal and CD40-inducible expression of VEGF.

A), HUVEC were transfected with a control siRNA or with siRNAs to TRAF 1/2/3/5/6 as illustrated. After 24 hrs, the cells were co-transfected with a full-length 2.6-kb VEGF promoter-luciferase construct and were cultured in the absence or presence of sCD40L (3 μg/ml) for an additional 24 hrs. The cells were lysed and promoter luciferase activity was evaluated. Induced promoter activity was calculated as the fold change in luciferase counts from each group of cells, compared to control siRNA-transfected cells. Illustrated are the mean results from four independent experiments (± 1SEM). B), For each experiment, knockdown efficiency was evaluated 48hrs after siRNA transfection by Western blot analysis. A representative blot is illustrated.

Role for TRAF6 in the regulation of EC proliferation and migration

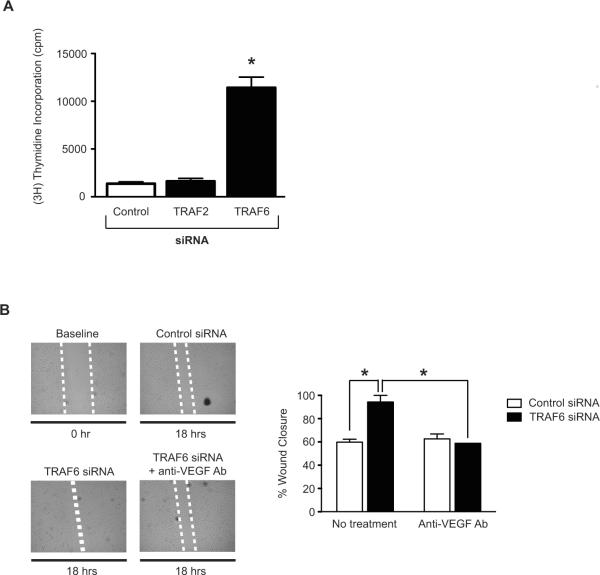

To evaluate the physiological relevance of these observations we also analyzed the function of TRAF2 and TRAF6 in EC proliferative responses. As above, EC were transfected either with siRNAs to TRAF2 or TRAF6 and after 72hrs, EC proliferation was assessed by [3H] Thymidine incorporation. As illustrated in Figure 2A, we found a greater than five fold increase in basal rates of EC proliferation following knockdown of TRAF6 as compared to control siRNA-transfected cells (P<0.0005). However, TRAF2 knockdown did not increase EC proliferation.

Figure 2. Effect of TRAF6 knockdown on EC proliferation and migration in vitro.

A) HUVEC were transfected either with a control siRNA, or with siRNAs to TRAF2 or TRAF6. After 72 hrs, proliferation was evaluated using the [3H] thymidine incorporation assay (1mCi/well). The mean proliferative responses (± 1SEM) of three independent experiments are shown. *P<0.0005 vs. control siRNA. B) HUVEC were transfected with a control siRNA or with the TRAF6 siRNA. After 48 hrs, a linear wound was created in confluent cell culture monolayers using a pipet tip. The cells were subsequently cultured in the absence or presence of a neutralizing anti-VEGF antibody (10 μg/ml), and the migration of cells into the wound was monitored by microscopy every 6 hrs for up to 24 hrs. Representative photomicrographs of wound closure in each group of cells are shown. The dotted white line highlights the wound (representative of n=3). The bar graph illustrates the mean percentage wound closure (± 1SEM) in three experiments. *P<0.05. As illustrated, wound closure occurred after ~18hrs in the TRAF6 siRNA transfected cells, earlier than control siRNA-transfected cells and untransfected cells.

To further evaluate the role of TRAF6 as an endogenous regulator of angiogenesis, we transfected EC with control siRNA or TRAF6 siRNA, and we examined EC migration using the well-established wound-healing assay [25]. After 18hrs, we found that wound healing/EC migration was significantly increased in EC transfected with TRAF6 siRNA as compared to control siRNA-transfected EC (P<0.05, Figure 2B). To test if TRAF6 mediates this effect via the regulation of VEGF expression, we performed the identical assay using EC cultured in the presence of a neutralizing anti-VEGF antibody. Illustrated in Figure 2B, we found that anti-VEGF completely blocked the TRAF6-induced migratory response to baseline, indicating that TRAF6 regulates basal migratory responses via augmentation of VEGF production.

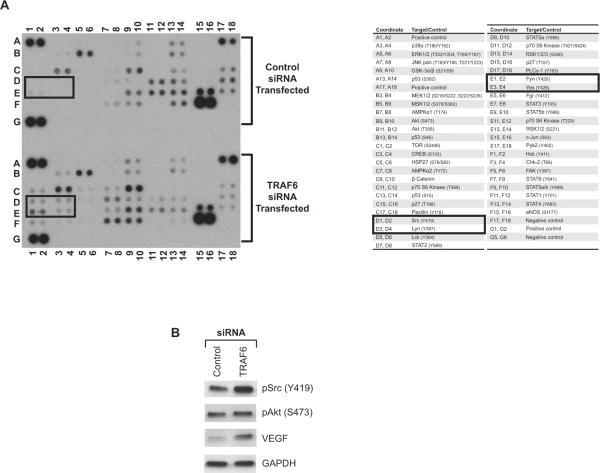

TRAF6 regulates pro-angiogenic signaling pathways in EC

To gain insight into intermediary signaling pathways regulated by TRAF6, we compared the activity of 46 kinases and transactivators in control siRNA- and TRAF6 siRNA-transfected EC using a commercially available phosphokinase array. As illustrated in Figure 3A and as anticipated [8], we found differences in the expression of kinases associated with the Akt/mTOR signaling pathway in TRAF6 siRNA-transfected cells vs. controls (Figure 3A, lanes D and E 11–12). In addition, we found marked differences in the phosphorylation/ activation of Src family kinases (including Lyn, Fyn, and Yes) (Figure 3A, lanes D and E 1–4) following TRAF6 knockdown, and there were notable effects of TRAF6 on the activity of the STAT family of transcription factors (Figure 3A, lanes F7–10).

Figure 3. Effect of TRAF6 on pro-angiogenic signaling pathways in EC.

HUVEC were transfected with control siRNA or with TRAF6 siRNA, and after 48 hrs, a phosphokinase protein array was performed on cell lysates (in duplicate). A), Illustrated is a representative blot showing the relative expression of individual phosphokinases in control and in TRAF6 siRNA transfected EC. The table on the right of the blot indicates the location of proteins tested in this array. B), Lysates from 48 hrs siRNA-transfected EC were subjected to Western blot analysis using anti-phospho-Src (Tyr419), anti-phospho-Akt (Ser473) and anti-VEGF antibodies. The expression of GAPDH served as an internal control. The illustrated blot is representative of three with similar results.

We confirmed the effect of TRAF6 on PI-3K/Akt and Src activation by Western blot analysis (Figure 3B). Although we had anticipated that TRAFs knockdown would result in an inhibition of Akt activity [8], we found minimal effects of either TRAF1, -2, -3 and -5 and -6 knockdown on the expression of phospho-Akt as compared to control siRNA-transfected EC (Figure 3B and data not shown). We interpret these findings to suggest redundancy in the function of individual TRAFs for activation of PI-3K/Akt signaling. Nevertheless, and consistent with the array data, by Western blot analysis, we found a modest increase in phospho-Src expression in TRAF6 siRNA-transfected EC vs. controls (Figure 3B). In addition, and consistent with our findings illustrated in Figure 1, we also observed that knockdown of TRAF6 resulted in a marked induction in VEGF protein expression (Figure 3B). Collectively these observations indicate that TRAF6-mediated regulation of Src may in part account for its effect on the regulation of endogenous VEGF expression in EC.

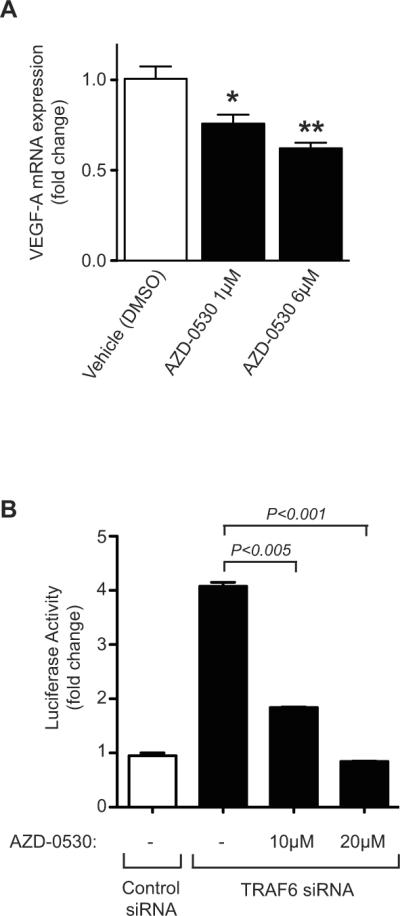

Src activation mediates the expression of VEGF in EC

To evaluate the effect of Src on VEGF overexpression, we next treated EC with the pharmacological Src kinase inhibitor AZD-0530 (1μM or 6μM) and we determined its effect on VEGF at the mRNA level. As illustrated in Figure 4A, we found that pharmacological inhibition of Src resulted in a significant reduction in VEGF mRNA expression as compared to cells treated with vehicle alone. Since TRAF6 knockdown increases Src activity as well as VEGF expression, we co-transfected EC with our VEGF promoter luciferase construct and TRAF6 siRNA, and we evaluated transactivation in the absence or presence of AZD-0530. As illustrated in Figure 4B, we found that TRAF6 knockdown again resulted in an increase in VEGF promoter activity. Moreover, we found an inhibitory effect of AZD-0530 on VEGF promoter activation; inhibition was variable at low concentrations while higher concentrations (>10mM) had a notable effect (Figure 4B). In some experiments using the highest concentrations of AZD-0530, there were toxic effects on siRNA and promoter co-transfected EC (data not shown). This finding is most suggestive that TRAF6 inhibits basal VEGF expression in part via its ability to regulate Src activity in EC.

Figure 4. Effect of TRAF6-Src crosstalk for VEGF expression in EC.

A), Confluent monolayers of HUVEC were cultured in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of the Src kinase inhibitor AZD-0530. The cells were harvested as a time course from 18–36 hrs and VEGF mRNA expression was evaluated by real-time qPCR. Illustrated are the mean results of four experiments performed after 18hrs of treatment. The data is expressed as mean fold change in expression over baseline (± 1SEM). B), HUVEC were transfected with a control siRNA or with TRAF6 siRNA and, after 24 hrs, were co-transfected with a full-length 2.6-kb VEGF promoter-luciferase construct and were cultured in the absence or presence of increasing concentrations of AZD-0530 for an additional 24 hrs. The cells were lysed and promoter luciferase activity was calculated as the fold change in luciferase counts from each group of cells, compared to control siRNA-transfected cells. *P<0.05, **P<0.005.

DISCUSSION

In these studies, we establish a new function for the TRAF family of adaptor molecules in the maintenance of both basal as well as inducible expression of VEGF by EC. While we find some redundancy in the function of TRAF2, TRAF3 and TRAF5, our studies indicate that TRAF6 is a potent endogenous regulator of angiogenesis in part via its ability to inhibit Src family kinase activity. Collectively, these observations define a model whereby TRAF6 serves as a cell-intrinsic regulator of the angiogenesis response.

TRAF adaptor molecules are well established to function in TNF family signaling cascades [15,26,27,28,29]. However, only a few studies have evaluated their expression and function in EC [23,30,31,32], and their role in angiogenesis has not been previously explored. CD40-induced responses in EC are potent to induce VEGF expression, VEGF-dependent EC proliferation in vitro and angiogenesis in vivo [2,3,8,21,24]. Furthermore, CD40-induced angiogenesis is associated with breast cancer growth and progression [4,5]. TNFα also induces VEGF expression in different cell types including EC [6,7] and has been shown to induce angiogenesis in vivo at low concentrations [33,34,35]. Thus, it seems likely that TRAFs, especially TRAF2, TRAF5 and TRAF6, will serve to augment endogenous VEGF expression in EC and the angiogenesis response. However, we paradoxically found that all TRAFs, and notably TRAF6, serve to regulate basal as well as inducible levels of VEGF expression as well as EC proliferation and migration. Perhaps therefore, the relative activation of TRAF6 within EC will be a determinant of VEGF-dependent EC proliferation and angiogenesis. Indeed, consistent with this possibility, we find that induced EC proliferation and migration following knockdown of TRAF6 is inhibited by a blocking anti-VEGF antibody.

Using a phosphokinase array and Western blot analysis, we also found that the potent effect of TRAF6 on VEGF overexpression was associated with its ability to regulate the Src family kinases, JNK family kinases, and the activation of the STAT family of transcription factors. All of these kinases and transcription factors have been found to be important in EC survival, proliferation as well as in VEGF expression [36,37,38]. Thus, the relative activation of different members of the TRAF family in EC may suppress cell intrinsic signaling responses associated with the initiation, amplification as well as the suppression of angiogenesis.

Although not the subject of this study, the observed regulatory effect of TRAF6 on Src kinase activation and its ability to mediate crosstalk with other signaling pathways might also have important implications for proinflammation. Indeed, and consistent with this possibility we find that TRAF6 regulates families of STATs, which are well established to function in cytokine and chemokine-dependent responses. Also consistent with this possibility, a previous study demonstrated that TRAFs may function in EC to regulate chemokine expression [23]. TRAF6 was found to suppress MCP-1 expression in EC following CD40-dependent activation, and TRAF6 knockout mice were more prone to the development of atherosclerosis [23,32], which is an angiogenesis dependent process [1,39,40]. In addition, and consistent with our findings in this report, it was also observed that the function of TRAF2, TRAF3 and TRAF5 were different than those of TRAF6 on the regulation of chemokine/inflammatory responses [23]. Collectively, all these data indicate that TRAF6 has intrinsic regulatory functions in EC, and our observations in this report have broad implications for its role in angiogenesis-dependent diseases.

HIGHLIGHTS

TNF-receptor associated factors (TRAFs) function in the angiogenesis response.

TRAF6 regulates basal and inducible expression of VEGF in endothelial cells (EC).

TRAF6 is an endogenous inhibitor of EC proliferation and migration in EC.

TRAF6 inhibits VEGF expression in part via its ability to regulate Src signaling.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We wish to thank Drs. Raif Geha and Debabrata Mukhopadyay for helpful discussions about this work.

These studies were supported by National Institutes of Health Grant AI046756 (to DMB), and SB was supported by Fellowship grants from the Bettencourt-Schueller Foundation and the American Society of Transplantation.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

FOOTNOTES SB and DD contributed equally to this work.

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest related to this work.

REFERENCES

- [1].Cotran R. Inflammation and repair. In: Cotran JRS, Kumar V Jr, Robbins SL Jr, editors. Pathologic Basis of Disease. W. B. Saunders; Philadelphia: 1994. pp. 51–92. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Melter M, Reinders ME, Sho M, et al. Ligation of CD40 induces the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor by endothelial cells and monocytes and promotes angiogenesis in vivo. Blood. 2000;96:3801–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Reinders ME, Sho M, Robertson SW, et al. Proangiogenic function of CD40 ligand-CD40 interactions. J Immunol. 2003;171:1534–41. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.3.1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chiodoni C, Iezzi M, Guiducci C, et al. Triggering CD40 on endothelial cells contributes to tumor growth. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2441–50. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Bergmann S, Pandolfi PP. Giving blood: a new role for CD40 in tumorigenesis. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2409–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Yoshida S, Ono M, Shono T, et al. Involvement of interleukin-8, vascular endothelial growth factor, and basic fibroblast growth factor in tumor necrosis factor alpha-dependent angiogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:4015–23. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.7.4015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Bottomley MJ, Webb NJ, Watson CJ, et al. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from patients with rheumatoid arthritis spontaneously secrete vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF): specific up-regulation by tumour necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha) in synovial fluid. Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;117:171–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.00949.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Dormond O, Contreras AG, Meijer E, et al. CD40-induced signaling in human endothelial cells results in mTORC2- and Akt-dependent expression of vascular endothelial growth factor in vitro and in vivo. J Immunol. 2008;181:8088–95. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.8088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Pullen SS, Miller HG, Everdeen DS, et al. CD40-tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF) interactions: regulation of CD40 signaling through multiple TRAF binding sites and TRAF hetero-oligomerization. Biochemistry. 1998;37:11836–45. doi: 10.1021/bi981067q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Hu HM, O'Rourke K, Boguski MS, et al. A novel RING finger protein interacts with the cytoplasmic domain of CD40. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:30069–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Ishida T, Mizushima S, Azuma S, et al. Identification of TRAF6, a novel tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor protein that mediates signaling from an amino-terminal domain of the CD40 cytoplasmic region. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:28745–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.46.28745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ishida TK, Tojo T, Aoki T, et al. TRAF5, a novel tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor family protein, mediates CD40 signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:9437–42. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Tsitsikov EN, Laouini D, Dunn IF, et al. TRAF1 is a negative regulator of TNF signaling. enhanced TNF signaling in TRAF1-deficient mice. Immunity. 2001;15:647–57. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00207-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Arch RH, Gedrich RW, Thompson CB. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors (TRAFs)--a family of adapter proteins that regulates life and death. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2821–30. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bradley JR, Pober JS. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factors (TRAFs) Oncogene. 2001;20:6482–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hsu H, Shu HB, Pan MG, et al. TRADD-TRAF2 and TRADD-FADD interactions define two distinct TNF receptor 1 signal transduction pathways. Cell. 1996;84:299–308. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80984-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Rothe M, Wong SC, Henzel WJ, et al. A novel family of putative signal transducers associated with the cytoplasmic domain of the 75 kDa tumor necrosis factor receptor. Cell. 1994;78:681–92. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90532-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Baud V, Karin M. Signal transduction by tumor necrosis factor and its relatives. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:372–7. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02064-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Arron JR, Pewzner-Jung Y, Walsh MC, et al. Regulation of the subcellular localization of tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor (TRAF)2 by TRAF1 reveals mechanisms of TRAF2 signaling. J Exp Med. 2002;196:923–34. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Krajewska M, Krajewski S, Zapata JM, et al. TRAF-4 expression in epithelial progenitor cells. Analysis in normal adult, fetal, and tumor tissues. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1549–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Flaxenburg JA, Melter M, Lapchak PH, et al. The CD40-induced signaling pathway in endothelial cells resulting in the overexpression of vascular endothelial growth factor involves Ras and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. J Immunol. 2004;172:7503–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Zirlik A, Bavendiek U, Libby P, et al. TRAF-1, -2, -3, -5, and -6 are induced in atherosclerotic plaques and differentially mediate proinflammatory functions of CD40L in endothelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:1101–7. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.140566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lapchak PH, Melter M, Pal S, et al. CD40-induced transcriptional activation of vascular endothelial growth factor involves a 68-bp region of the promoter containing a CpG island. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;287:F512–20. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00070.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Zhang X, Rozengurt E, Reed EF. HLA class I molecules partner with integrin beta4 to stimulate endothelial cell proliferation and migration. Sci Signal. 3:ra85. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2001158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Schonbeck U, Libby P. The CD40/CD154 receptor/ligand dyad. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2001;58:4–43. doi: 10.1007/PL00000776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Bishop GA, Hostager BS. The CD40–CD154 interaction in B cell-T cell liaisons. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2003;14:297–309. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(03)00024-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Harnett MM. CD40: a growing cytoplasmic tale. Sci STKE. 2004;2004:pe25. doi: 10.1126/stke.2372004pe25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Kehry MR. CD40-mediated signaling in B cells. Balancing cell survival, growth, and death. J Immunol. 1996;156:2345–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Min W, Pober JS. TNF initiates E-selectin transcription in human endothelial cells through parallel TRAF-NF-kappa B and TRAF-RAC/CDC42-JNK-c-Jun/ATF2 pathways. J Immunol. 1997;159:3508–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Feng X, Gaeta ML, Madge LA, et al. Caveolin-1 associates with TRAF2 to form a complex that is recruited to tumor necrosis factor receptors. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:8341–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007116200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Urbich C, Mallat Z, Tedgui A, et al. Upregulation of TRAF-3 by shear stress blocks CD40-mediated endothelial activation. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1451–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI13620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Frater-Schroder M, Risau W, Hallmann R, et al. Tumor necrosis factor type alpha, a potent inhibitor of endothelial cell growth in vitro, is angiogenic in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:5277–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.15.5277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Leibovich SJ, Polverini PJ, Shepard HM, et al. Macrophage-induced angiogenesis is mediated by tumour necrosis factor-alpha. Nature. 1987;329:630–2. doi: 10.1038/329630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Fajardo LF, Kwan HH, Kowalski J, et al. Dual role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1992;140:539–44. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Park SI, Shah AN, Zhang J, et al. Regulation of angiogenesis and vascular permeability by Src family kinases: opportunities for therapeutic treatment of solid tumors. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2007;11:1207–17. doi: 10.1517/14728222.11.9.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hoefen RJ, Berk BC. The role of MAP kinases in endothelial activation. Vascul Pharmacol. 2002;38:271–3. doi: 10.1016/s1537-1891(02)00251-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Brown LF, Detmar M, Claffey K, et al. Vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor: a multifunctional angiogenic cytokine. EXS. 1997;79:233–69. doi: 10.1007/978-3-0348-9006-9_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Moulton KS, Heller E, Konerding MA, et al. Angiogenesis inhibitors endostatin or TNP-470 reduce intimal neovascularization and plaque growth in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice. Circulation. 1999;99:1726–32. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.13.1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Moulton KS, Vakili K, Zurakowski D, et al. Inhibition of plaque neovascularization reduces macrophage accumulation and progression of advanced atherosclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4736–41. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0730843100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]