Abstract

The current economic and social context calls for a renewed assessment of the consequences of an early transition to parenthood. In interviews with 55 teenage mothers in Colorado, we find that they are experiencing severe economic and social strains. Financially, although most are receiving substantial help from family members and sometimes their children’s fathers, basic needs often remain unmet. Macroeconomic and family structure trends have resulted in deprived material circumstances, while welfare reform and other changes have reduced the availability of aid. Socially, families’ and communities’ disapproval of early childbearing negatively influences the support young mothers receive, their social interactions, and their experiences with social institutions.

Keywords: Teenage mothers, Qualitative research, Economic hardship, Social norms, Life course

Background

The United States has the highest rates of teen pregnancy and births in the fully industrialized world, with 18% of all teenage girls expected to give birth before age 20 (Perper and Manlove 2009). Teenage parenthood is viewed as an important problem in U.S. society and has been a central policy concern for decades (Furstenberg 2003). Teenage childbearing is much more prevalent in lower socioeconomic status (SES) subpopulations (Holcombe et al. 2009). For example, more than half of a recent nationally representative sample of children who, as infants, lived in poverty or had a mother who had not completed high school were born to women who had become mothers before age 20 (Mollborn and Dennis in press). Teenage mothers also disproportionately identify as African American, Latina, and American Indian as compared to non-Latina White or Asian American (Hamilton et al. 2009). The prevalence of teen parenthood in these socioeconomically and racially marginalized groups has likely contributed to the high level of public concern about teen childbearing (Furstenberg 2003).

A wealth of quantitative research has focused on the consequences of early childbearing for mothers and children, largely relying on data collected in past decades (see Hoffman 1998 for a review). An initial focus on the negative association between being a teenage mother and socioeconomic outcomes has given way to an awareness that much or most of this relationship is explained by the social disadvantage teen mothers experience before they get pregnant, rather than the experience of young motherhood itself. Quantitative research comparing teen mothers to their childless sisters or twins, teens who miscarried, or teens who have a similar propensity of becoming mothers based on their background characteristics generally supports this conclusion (Geronimus and Korenman 1992; Grogger and Bronars 1993; Hotz et al. 2005; Levine and Painter 2003). Today, many scholars would likely agree with Furstenberg’s (2007) recent assessment based on the Baltimore Study of urban African American women who had teenage births in the 1960s: Early childbearing has negative short-term consequences for many girls, but their long-term socioeconomic outcomes improve considerably and do not differ drastically from those of similar peers who delayed childbearing. Examining the long-term effects of early parenthood in a predominantly white, more socioeconomically advantaged sample of 1957 Wisconsin high school graduates, Taylor (2009) found that teenage mothers and fathers lagged behind their peers at midlife in terms of education and occupational status, but their work involvement and income levels were similar. However, the consequences of early childbearing extend beyond the socioeconomic domain. Henretta (2007), examining the later-life health of women born from 1931 to 1941, found that younger age at first birth was associated with higher rates of mortality and morbidity once socioeconomic status was controlled.

There is a rich body of ethnographic literature on teen parenthood as well, often focusing on communities’ reactions to teen childbearing and on young mothers’ lived experiences (e.g., Burton 1990; Edin and Kefalas 2005; Gregson 2009; Jacobs 1994; Kaplan 1997; Ladner and Gourdine 1984). Although researchers studying different communities have reached different conclusions, many have characterized specific communities as encouraging or welcoming teen childbearing. For example, studying a low-income, predominantly African American community, Burton (1990) found that residents welcomed motherhood as a marker that a girl had become an adult, in the absence of other available socioeconomic transitions to adulthood such as attaining an educational degree or starting full-time work. Yet there is debate on this point: In a community with high rates of teen childbearing, Kaplan (1997) found that many adults disapproved strongly of teen motherhood.

A central concern with the existing literature, both quantitative and qualitative, is that it tends to rely on data collected in past decades. Since then, the structural and cultural contexts of teen parenthood have changed, leading us to argue that a renewed assessment of the life situations of teen mothers and their families is needed. In this study, we focus on economic, demographic, and normative changes in the contexts of teen childbearing. Other recent societal trends that are not directly addressed in our data are nonetheless important to note, such as the rise in “abstinence-only” school-based sex education for teens that omits information about contraception (Santelli et al. 2006), the continued lag in American teens’ use of contraception relative to their peers in other developed countries (Darroch et al. 2001), and the lack of availability of many reproductive health services for women in large swaths of the United States (Jones et al. 2008).

Our inductive qualitative study expands on existing research, using newer data and examining a wider variety of processes and consequences for teen mothers and their children than survey research has been able to examine. While the analysis of longitudinal survey data has provided important insights about the consequences of teenage parenthood, the goal of our study is to take a more in-depth look at the quality and experiences of teenage mothers’ lives today. We explore how teenage parenthood influences the lives of young people and their children and work to illuminate a complex interplay of contributing factors that reflect the quality of teen mothers’ lives. We draw on in-depth qualitative interviews conducted with a local sample of 55 current and former teenage mothers to explore the life experiences of young mothers today.

In these interviews, two types of everyday strains regularly faced by teenage mothers emerged as fundamental for understanding their experiences. First, the young mothers we interviewed are facing severe economic strains in their everyday lives. We conclude that a combination of structural forces is placing considerable financial strain on the teenage parents in our sample and on family members who are trying to meet their needs. Second, our participants are enduring social strains related to their violation of social norms against teenage childbearing in their communities and in broader U.S. society. Their families and communities are not inclined to provide unconditional support or grant mothers the social rewards associated with adult status. Important differences in the life experiences of teenage mothers today compared to decades past—in terms of family resources, the availability of female relatives for child care, marital status, and being outside the normative age range for childbearing—have implications for both theory and policy. We outline the theoretical and empirical contributions of our work and suggest that further investigation of the consequences of contemporary teenage childbearing is warranted. Like much of the existing research on teen parenthood, we follow the life course theoretical perspective (Elder and O’Rand 1995), which calls for an integration of structural and cultural factors and historical change when studying teenage childbearing. To that end, we supplement our qualitative data with contextual information documenting economic, demographic, and cultural trends that are shaping the current contexts of teen mothers’ lives. Our discussion of findings begins with three structural trends (the lack of a public “safety net,” the decrease in private resources of low-SES families, and the demographic context of teen births), continues by examining the social strains faced by young women who have violated norms against teen parenthood, and ends with a discussion of the consequences of these economic and social strains for young mothers’ life courses.

The Study

The larger qualitative study from which these findings are drawn consists of in-depth interviews with current and former teenage mothers and fathers, combined with limited participant observation at the two sites—a school and a clinic—where the interviews took place. The interviews were conducted during a four-month period in 2008–2009. To be eligible for the study, participants must have had a child before turning 20. Most participants had babies or toddlers, but a few had older children. This variation in stages of parenting and in participants’ current ages was useful for observing both shorter- and longer-term experiences of teenage childbearing. Most interviews were conducted during the fall of 2008 when the current economic crisis was just beginning. Only the 55 interviews with teenage mothers are included here because the mothers had the primary responsibility for parenting and child care and thus experienced greater consequences of teenage parenting than did young fathers. We also focus primarily on the 52 women who became teen mothers within the past 5 years, to detail the experiences of the most recent cohort of teen mothers.

Our research team recruited participants from two research sites, both in the Denver metropolitan area.1 With teen mothers accounting for 12% of all births, Denver is fairly typical of U.S. cities (Child Trends 2009). When studying a population that is hard to reach, qualitative researchers often use either convenience samples based at sites serving the populations, or snowball samples. We chose the former strategy because it allowed us to interview a wide variety of participants who were not from the same social networks and neighborhoods. The two sites were chosen because each allowed access to a large pool of teenage parents from around the metropolitan area; because the populations they served differed in terms of age, race/ethnicity, geographic location, and educational aspirations; and because the sites differed substantially in the level of resources clients received. Nineteen interviews were conducted at a school for pregnant and parenting teenage girls. The school offers a rich variety of resources to its typically financially needy students, including onsite child care, basic medical and psychological services, career counseling, and a “school store” where students can exchange attendance credits for diapers and other baby items. Another 35 interviews were conducted at a hospital-based public clinic that provides health care to teenage mothers and their children, including privately insured and Medicaid patients.

These sites serve different populations, allowing us to tap into a broader variety of experiences of teen parenthood. Participants from the school were typically younger than 18, and they received child care, bus passes, and other material support from the school. Despite the excellent support provided by the school, many of these young mothers appeared to have fewer personal and family resources than those from the clinic. Participants from the clinic were frequently 18 or 19 years old, more often stayed at home or worked than attended school, and received less support from public services. The clinic participants were demographically more typical teenage parents than the school participants were, and they may have had access to more resources besides what the site could provide. A substantial minority of young mothers from both sites alluded to personal backgrounds of incarceration, substance abuse, victimization, or mental health concerns, and these issues were even more common in their families.

We recruited participants through flyers posted at the sites and given to participants to share with friends (though very few participants were recruited the latter way). School or clinic staff also handed out flyers and described the study to teens they identified as eligible. Nearly all participants were enrolled in the study through the onsite recruitment. Their current ages ranged from 15 to 38, and only 3 mothers (who are not our primary focus here) were older than 22. Our participants had given birth to their first child at age 14 to 19, but the average age at first birth was 17. This is lower than the average age for teen births in the U.S. in 2007 (Child Trends 2009), tapping into a more marginalized population than those aged 18 to 19. The average age of their oldest child was 1 1/2 years (excepting two respondents whose oldest children were fully grown), and 38 mothers had just one child. (For comparison, 76% of teen births in Denver in 2006 were first births [Child Trends 2009].) Most participants had grown up in the Denver area. Seven participants identified as multiracial or multiethnic, while others described themselves using a single racial or ethnic label: 27 self-identified as Latina/Hispanic/Mexican American, 14 as African American/black, 2 as white, and 1 as Native American. Compared to 2006 teen births in Denver (of which 75% were to Hispanic mothers, 12% to white mothers, and 11% to black mothers), our sample over-represents African Americans and underrepresents Latinas and Whites (Child Trends 2009). All of the school site’s 19 participants and 16 of the 35 clinic participants were enrolled in school, and 13 participants were working for pay. Fifteen mothers were married at the time of the interview, which is similar to the 23% of Denver teen mothers who are married at their child’s birth (Child Trends 2009). Nearly all were living with their children, and about half were living with a partner. Most lived in extended households: More than one third were living with at least one parent or parent-in-law, about one third with at least one sibling or sibling-in-law, and about one third with other adults who did not fit in these categories, such as an aunt or stepparent.

Semi-structured interviews about participants’ experiences with teenage parenthood lasted approximately 45 minutes, and participants received a $30 gift card. Many participants were explicit about needing the gift cards to purchase diapers, formula, or food. In a few instances, participants asked to schedule the interview as soon as possible because they were about to run out of money and needed the gift card. This underscores our finding that many participants were having trouble meeting their family’s basic needs. One or two interviewers from our research team (which included two female faculty members, one female and one male graduate student assistant, and one female undergraduate assistant who had been a teenage mother) conducted the interviews, which were digitally recorded and transcribed. In the roughly half of interviews with two interviewers, one person was primarily responsible for the interviewing while the other took notes and occasionally asked follow-up questions.

The research team took an ethnographic approach to the interviews and the sites, observing and writing field notes both about the sites and interactions with the participants. Researchers did not make extra trips for observation, but rather took note of the interactions and dynamics at the sites during their visits to meet with staff, recruit participants, and conduct interviews. For example, field notes documented observations of interactions between participants and their children and partners. Staff members’ comments about the resources available (or not) to young parents and the nature of potential participants’ time spent at the sites (including time constraints teen parents faced, people who often accompanied them, etc.) informed our plans for data collection and some of the interview questions. Topics covered during the interview included young parents’ perceptions of norms about teenage childbearing in their peer groups, families, communities, and society at large; how these norms influenced their fertility choices and behaviors; and what sanctions they faced as violators of these norms. We asked about any sanctions their families imposed on them, particularly focusing on material resources. Participants described the resources available to them, who provided them, and the negotiation processes they went through to put this structure in place. We asked participants how material resources had affected their educational and other life outcomes.

All interviews were transcribed and imported into the NVivo qualitative software package. Transcripts were manually coded using two methods. First, responses were coded according to the question the participant was answering, including simple distinctions between answers (e.g., specific family members’ positive versus negative reactions to the pregnancy). Second, both authors read entire transcripts and identified important themes that emerged from the data. These themes were then identified and coded for other transcripts. Using both of these analytic tools, we brought together our findings on norms, the resources available to teenage mothers, and the consequences of teenage motherhood. Our analysis thus addresses a number of questions about teen mothers’ finances and resources, their experiences of social sanctions, and the potential long-term implications of their situations within a contemporary twenty-first century perspective. Rather than generalizing these findings to a broader population, we attempt to document how economic and social strains translate into lived experiences for teen mothers, and we provide evidence to support our conclusion that nationally representative research should reassess the consequences of teen parenthood in today’s social and economic contexts.

We address each of the two key themes that arose from teenage mothers’ narratives of their everyday experiences: economic strains and social strains. Some questions in the interview guide elicited details of mothers’ everyday lives that addressed these strains: various resources available to the young mothers and the people who provided them, and the reactions of family, friends, and others to their pregnancy and parenthood. When answering these questions, the vast majority of participants gave us details about financial and social strains they were experiencing. We also asked more global questions about resources, such as whether the child’s needs are going unmet or whether there are things the mother wants for her child or herself that she is not able to get. Many young mothers said they had unmet wants or needs. In analyzing the data, it was clear that the participants found it easier to talk about the social strains they were experiencing than the financial pressures of their everyday lives. Nonetheless, when we analyzed the data, their accounts of their resource needs and the financial tensions in their family lives illuminated the extent to which their everyday circumstances were informed by the economic strains of teen parenthood.

Synthesizing Economic and Social Strains

Before we separately discuss the economic and social strains in teenage mothers’ lives, it is important to note that the two are intertwined. For example, societal norms against teenage childbearing may have fueled the rise of some structural barriers to young mothers’ success. In 1996, welfare reform was enacted under considerable public pressure to restrict benefits to young, single mothers. Such policy measures are a type of institutional sanction against women who violate societal norms about teen pregnancy. At the local level, schools may implement institutional sanctions in the form of policies that discourage young mothers’ attendance. For example, in 2008 Denver’s East High School received media attention when it required new mothers to return to school immediately after release from the hospital or accumulate unexcused absences (Meyer 2008). When a four-week maternity leave was proposed, public comments opposed “institutionaliz[ing] approval” of teenage childbearing through a “vacation” for young mothers (Harris 2008).

The experiences of Melissa,2 a Mexican-born mother of two who had her first child at 15, illustrate the interplay among norms against teen pregnancy, school sanctions, and economic strains. Her narrative exemplified other participants’ experiences.

And counselors and stuff started to tell me, “Have you ever thought about going to a different school?” I’m like, “Are you kicking me out?” “No, but you know, there’s this really good school for teen moms, and you’ll probably fit in better.” That was something cruel for me. I was like, oh, my god, if counselors and teachers are telling me this, what am I supposed to expect from random people in the street? … [At my school] there were two girls there that had babies, and they were telling me that they were thinking about coming to [school for pregnant and parenting teens]. So I said, “What’s so special about that school?” And they started telling me, “They have day care, and they help you get—if you need food for your baby, or formula, which is expensive, they can help you, and they have different programs and they have all this support for us.” So at the clinic, my doctor also knew about the school, and she definitely recommended it. So it was like, “I’m gonna call and see what it’s like.” And I came in and took a tour of the place, and I loved it right away.

Melissa’s experiences with school staff were hurtful to her, but ironically their pressure to leave the mainstream school led her to a situation that provided her with more support in the end.

Generally, both participants’ families and U.S. society currently evidence a sense of obligation to support young mothers and their children at least minimally, accompanied by clear disapproval of their life choices. This inherent tension results in contested policy decisions at the macro level and contested family decisions at the micro level concerning how much support young mothers should receive.

Economic Strains

The teenage mothers in our study described experiencing substantial economic strains in their everyday lives. We relate these strains to three structural trends: the lack of a public “safety net,” the decrease in private resources of low-SES families, and the demographic context of teen births. In this and the sections that follow, we first present contextual information documenting societal changes in recent decades, then present interview data analyzing our participants’ experiences today.

The Shrinking Public “Safety Net”

In the 20 years since the second author interviewed teenage mothers at one of the same sites (Jacobs 1994), structural shifts have occurred in the societal supports available to teenage mothers and their children. Perhaps the most significant of these has been the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996, popularly known as “welfare reform.” The act created the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program, the heir to the “welfare” moniker, and implemented a 60-month lifetime benefit cap for adults. Two important new restrictions altered underage mothers’ eligibility: To receive assistance, they are typically required to live with a parent and be enrolled in secondary school until they graduate, although they frequently may not pursue postsecondary education (Moffitt 2003); and legal immigrants must meet stricter eligibility requirements (Schott 2009). The former restriction was important for the teenage mothers in our sample, but not the latter because only two mothers reported being foreign born.

Perhaps not surprisingly given these new restrictions, TANF caseloads have declined substantially since 1996. In the 1980s and early 1990s, 80% of families who were poor enough to qualify for welfare and who met the other eligibility requirements received cash assistance. By 2005, this number had declined to 40 percent, despite the stricter eligibility requirements after 1996 (Sherman 2009). Some states have reported that the rate of decline in receipt of benefits has been even steeper among teenage mothers than among others (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2000). Zaslow et al. (2002) reported that welfare-to-work programs such as TANF do not improve children’s outcomes unless they help families make economic progress. While some families are now better off than when they were on welfare, many are not. In 2005, TANF lifted only 21% of deeply poor children above the threshold of half the federal poverty line, compared to 62% in the mid-1990s (Sherman 2009). With less government support available to teenage mothers and their children, they are likely to rely more on their families.

As our interviews show, the public safety net has been selectively withdrawn for some important programs but not for others. In past decades, teenage mothers’ and their children’s most pressing needs could have been met by social programs providing basic financial support (through TANF, or “welfare”), housing (through the housing choice voucher program known as “section 8” or other housing assistance programs), food (through the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children, or WIC, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or “food stamps”), health insurance (through Medicaid and state programs), and child care. Today, two of these programs, Medicaid and WIC, were serving the vast majority of our participants, providing much-needed health care and certain staple foods. In a typical comment, 16-year-old multiracial mother Destiny said, “Medicaid covers everything. If we go to the emergency room or anything, then it covers it. WIC, it’s [even] easier … because they don’t ask a whole bunch of questions. And when I was pregnant, I had WIC. So it was just an ongoing process.” Almost half of the mothers reported receiving food stamps, which provide more extensive food support than WIC. Very few reported receiving public financial assistance from TANF, housing assistance, or child care assistance. For example, only three told us that they were receiving TANF benefits. In short, mothers reported that while government programs were providing substantial help with medical care and some staple foods, other important needs were rarely being met by public services.

When asked why they did not receive various types of government benefits, many answered that they had not applied because they felt they would not be eligible or that the rules were too strict to make participation feasible. For example, Hailey, a married Hispanic mother of two, highlighted perceived difficulties with obtaining housing support as she told us what programs she thought would help teenage parents and their children:

I would help them by first, a bigger school, bigger day care. And housing. It’s really hard. To get housing, you have to be homeless. It’s like, they want you to live on the street or in your car. If somebody needs help, they need help. So I would find a way to help them. They’re young, they’re teen moms, they already have it hard.

Interviewer: Make that easier to get that help, because they’ve got all this other stuff going on?

Yes. It’s really a hard thing. You see all these moms here. Some live with people that they don’t even want to be with, and they come here and ask them for housing, and they ask, “Are you homeless?” “No, I’m living with these people but I want to get out of there.” “Well, you have to be homeless, or go to a shelter for a month and then we’ll help you.”

Many other participants doubted based on previous experience that some government programs could be much help. Lucy, an 18-year-old multiracial mother, said:

When I had signed up for TANF, I had my own place [with my sister]. … She would always have everybody go over and party and stuff, so I didn’t like that idea, with my daughter being there, so I moved in with my mom and I did the change of address, and that’s when they said that my mom and dad make too much income.

Several participants talked about being denied financial assistance from TANF on the basis of family members’ incomes, even if they did not have access to that money.

Even without having applied for government programs, many young parents gave up because they knew how difficult restrictions often were and how few of their needs the support would meet. Emily’s assessment of a fellow teenage mother’s situation illustrates this dynamic: “I have a friend who’s struggling. She needs money. … She’s trying to go to school, and she could get TANF, which gives you $280 a month. What can you do with $280?” Amanda, an 18-year-old Hispanic mother, did not see government programs, families, or communities as viable sources of support for young mothers. When asked what she would do to help teenage parents and their children if she were in charge, Amanda hesitated and finally said, “We definitely need a miracle.”

Dwindling Resources Available to Low-SES Families

Even though welfare programs have tightened their requirements and pushed millions of families off their rolls, young mothers might be at least as well off as they were 20 years ago if their own or their families’ labor market prospects had improved relative to better-off citizens or relative to their cost of living. Regrettably, this has generally not been the case. Between 1979 and 2005, real after-tax incomes for families in the lowest 20% of the income distribution, from which teenage mothers disproportionately come, grew by just 6%, compared to 80% growth for those in the top 20%of the income distribution (Sherman 2007). Income inequality in the United States in 2007 was at its highest level since the 1920s (Saez 2008). This disparity does not seem to have arisen because low-income workers have opted out of full-time work: Many low-income wage-earners can find only part-time work and would prefer to work more hours (Gerson and Jacobs 2004). Indeed, Americans with the lowest levels of education tend to bear the brunt of high rates of unemployment in economic downturns (Camarota and Jensenius 2009).

These troubling economic trends are exacerbated by increasing levels of household indebtedness and escalating expenses (Dynan and Kohn 2007). For example, rising medical costs have far outpaced increases in income in the past several years (Banthin et al. 2008), and the annual cost of child care in many parts of the country is twice as high as the cost of in-state college tuition (Schulman 2000). Child care expenses are particularly disruptive for poor families’ budgets: On average, poor families who pay for child care spend one-quarter to one-third of their after-tax incomes on child care (U.S. Census Bureau 2005).

At the same time that lower-SES families have lost pace relative to others in terms of income, their supply of “invisible labor” has also diminished. Women’s labor force participation has increased substantially in recent decades (England et al. 2004). With more women working for pay, families’ availability to help with child care and other types of instrumental support has likely decreased, as Brewster and Padavic (2002) have shown among African Americans. Therefore, whether resources are measured as money or time, many low-SES families have fewer than in the past.

Families’ support of teenage mothers and their children in our study typically reflected these limited resources. Although participants’ circumstances varied, nearly all told us that they were receiving at least some support from family members (although friends typically did not have children of their own to care for, they were rarely an important source of support). However, about half said that at least some family members were not helping them as much as the participants had expected. In a fairly typical example, Adriana, a 17-year-old Hispanic mother who was enrolled full time at the school for parenting teenagers, reported that she and her 2 year old daughter lived with “a lot of people”: several siblings and half-siblings, her father and stepmother, and her grandmother. She used to live with her daughter’s father and his mother, but the couple broke up when her daughter was a baby. She said that her father and grandmother provided housing and paid the bills, and her daughter’s father sometimes paid for diapers and clothes. She did laundry for herself and her daughter and helped with housework. Medicaid paid her medical costs, and the WIC program helped her in the past but not now. Like many other mothers, Adriana told us that she often did not have spending money because “as long as I don’t need something really bad, I don’t want to ask for it.” Her daughter’s paternal grandmother helped a lot with child care and was the person who Adriana said helps her the most. Like many of the mothers, Adriana reported receiving a lot of help from various family members but worried about taxing her family’s resources. Referring to her daughter’s laundry, she said, “Her clothes are small. It doesn’t take up that much soap.” Her grandparents did not help her as much as she expected them to; in particular, she thought her relationship with her grandfather had cooled since she got pregnant. As with many of the mothers we interviewed, Adriana reported getting a lot of help from some family members but not others.

In many cases, teenage mothers said that although they were receiving support from family members, the assistance was contingent on family members’ availability and sometimes caused as many problems as it solved. This may arise in part from relatives’ limited resources rather than from a lack of inclination to help. For example, 16-year-old Angela told us that her mother-in-law watched her daughter for free, while at the same time watching a disabled relative and two young children whose parents pay for their care. Angela appreciated the care, but “if she [mother-in-law] gets another [paying] kid, my daughter gets kicked out.” Angela also thought that her daughter did not “get the attention she deserves” and had other concerns about the quality of her mother-in-law’s care:

My husband and my mom, I feel, are kind of affecting her [daughter] in a good way. I’m not so sure about my mother-in-law. I don’t know what to think of it. …I know she gives her bottles all day, and we go out and with our food stamps, we bought her all this food, and they don’t want to feed it to her because it [feeding a child baby food by hand] takes longer than to make lunch for a toddler [feeding by bottle]. …She was sick last week and it was a runny nose and a little bit of cough, nothing where I would take her to the emergency room or anything. And I had a humidifier on her and stuff. And his mom goes in her room, where she was sleeping all day, turned the humidifier off, hid it from us, wouldn’t give her any juice. I’m like, those are the things that are gonna help her. I don’t know if she has reasons for it. I’m not willing to get in an argument with her.

Angela’s situation highlights the power imbalances and lack of attractive alternatives that many teenage mothers reported experiencing when they accepted support from family members. Although at least some family members usually help young mothers, the responsibility for arranging support rests wholly with the mother, and she knows support could be withdrawn at any time. Amanda alludes to this situation when talking about the help she sometimes gets from her mother:

Sometimes [I ask for help] when I need her. I don’t really need her a lot. I’m really independent. I feel kind of that I shouldn’t need her help any more, like it’s my responsibility to get appointments set and it’s my responsibility to fill out paperwork.

In contrast, some participants such as Tiffany, an 18-year-old Mexican American mother, felt that either their child’s father or one of their parents “had to” help them out, implying a sense of more permanent obligation:

Interviewer: Who helps you the most out of everybody? Who’s the biggest help?

My mom, because she usually never says no. She won’t say no. My dad, there’s times where he’s like, “I’m too tired.” Or the baby’s not—I mean, everybody has such a busy schedule, and my mom is more flexible, so I can call her at work if I ever need anything. So usually my mom. And she has all the answers.

Having at least one person who “won’t say no” seems to be key for many mothers’ sense of security in managing their life situations and creating a future for themselves and their children.

The Demographic Context of Teen Births

Beyond changes in resources, broader demographic changes in recent decades have shaped the economic strains facing teenage mothers. Not only do teenage mothers and their families have disproportionately low incomes that are being outpaced by rising costs, but young mothers are now less likely to share these burdens with a spouse. About 43% of teenage births were to married women in 1990 (U.S. Census Bureau 1990); this number fell to just 14% in 2007 (Hamilton et al. 2009). Some of the remaining 86% of mothers were cohabiting, but cohabiting unions are typically more unstable than marital unions (Manning et al. 2004). Regardless of their marital context, younger mothers’ unions are less stable than those of older parents (Manning et al. 2004). Given that working women earn 78 cents on the dollar compared to men and that the wage gap is even greater for single mothers (Arons 2008), income prospects for parenting teenage girls are often severely constrained when they do not have a male partner. In 2008, nearly a third of single-mother households had incomes below the poverty line (U.S. Census Bureau 2009), and in a nationally representative sample from 2001, about half of teenage mothers and their young children were living in poverty (Mollborn and Dennis in press).

In our study, about two thirds of the children’s fathers did not live with the mother and child. Those who did often provided substantial support within traditional gender roles as breadwinners and backup child care providers. Care and support of the child was often considered the mother’s responsibility even if the father “helps,” as Amanda described:

My husband does a lot of help with money. When he does have a job, that’s what he’s doing all the time, working for us. … I don’t really talk to him a lot about the stress, because he may be causing the stress! But I always lean off his shoulder for other problems. We’re like friends, best friends. He can come to me for things. He helps me a lot with the baby, too.

Interestingly, even when the baby’s father lived in the household, many young mothers cited one or both of their parents rather than their partner as the person who helps them most. Bethany, a 19-year-old Hispanic working mother, told us her mother was the person who helped her the most, even though her baby’s father lived with her.

Interviewer: Who do you think isn’t helping you that you thought might have helped you more?

[Baby’s dad’s name], because I felt he needed to be there to hold him when he’s fussy, but he don’t want to hold him when he’s fussy, he only wants to hold him when he’s happy. I just thought he might have been a better dad.

Despite most fathers’ lack of presence in the household, formal child support arrangements were very rare in our sample. Nevertheless, most fathers supported their children financially in informal ways, and in many cases fathers’ families provided additional support. Support often took the form of purchases of goods. As Adriana explained, “My baby’s dad, if she needs diapers, clothes, anything that she needs, I just tell him and he’ll go buy it for her.” Nineteen-year-old Amber emphasized that this kind of informal situation is highly dependent on the father having money to spend: “If he has anything to help with, he will, he’s very good about that. But when he doesn’t, he can’t. There’s nothing he can do.” The informal arrangements reported by our participants usually place the ultimate responsibility for meeting the child’s needs on the mother: She has to “tell him” what to buy, she is at the mercy of his generosity every time she asks, and he has the option of refusing support. Support that might fall through at any time makes it more difficult to plan and achieve long-term educational or career goals.

In some cases, fathers did not provide meaningful support. Amy, a single Hispanic mother who had a child at 16, described a difficult relationship with her baby’s father:

Me and him had a lot of problems, and he’d rather hang out with his friends than actually spend time with me and my daughter and help me out with her sometimes.

She and her baby’s father eventually broke up. Amy discussed the situation now:

He’ll call. Sometimes I think he calls to talk to me because I have to remind him that he has a daughter. He doesn’t want to do anything for her. … When he comes around, he tries to offer some money. The most he’s offered was about $5 to $10. But I really don’t like taking stuff from him, either, because when he does it, he complains about doing it. He doesn’t help out too much.

These quotes show that fathers’ levels of support varied considerably, but in each of the situations the responsibility for caring for and supporting the child rested primarily on the mother.

To summarize the economic strains experienced by the teenage mothers we spoke with, withdrawal of the public “safety net” made our interviewees more reliant on their families, but these families typically had relatively less money, time, and energy to give. In addition, in contrast to decades past, today the vast majority of teenage mothers do not have spouses, who in some cases could be a meaningful source of support. While most fathers provided some level of informal support for the child, it was often sporadic and on the father’s terms. Most did not have formal child support agreements, and some fathers provided no support at all.

Social Strains

The teenage mothers we spoke with were facing a variety of financial and structural strains that may limit their prospects for mobility. In addition, they talked about confronting substantial social strains that shaped their interpersonal interactions, available social support, and mental health. These strains, and contextual information documenting the societal trends shaping them, are described below.

For the past several decades, teenage mothers have lived in a society that has devoted considerable energy to condemning teenage childbearing. The strength of societal norms against teen pregnancy is apparent in polling data from the 1990s. In a 1999 survey, 68% of adults thought that teen pregnancy was “a major problem facing our country” (Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation 1999). In 1995, 74% of respondents said that it is “morally wrong” to “conceive a child out of wedlock if the mother is a teenager and is unable to financially support the baby” (Newsweek and Princeton Survey Research Associates 1995). In a 1996 poll, 49% of respondents thought that the government should not provide welfare payments to single teenage mothers compared to 45% who thought it should, implying that many people support strong sanctions against these mothers (Knight Ridder and Princeton Survey Research Associates 1996).

Ethnographic research from earlier decades found that in African American and Latino communities, many of teenage mothers’ family and community members, while not approving of early childbearing, nonetheless conferred social rewards on young mothers and welcomed the babies into their lives (Burton 1990; Ladner 1995). Parenthood conferred adult status, which bestowed some respect and social benefits in the family or community.3 Interviewing teenage mothers at one of our sites in 1989, Jacobs (1994) found that family members treated some participants with greater respect after becoming mothers. Burton’s ethnographic research from the 1980s suggested that teenage childbearing was “accepted normative life-course strategy” in low-income African American families in response to circumstances in their social environments (1990, 130). In contrast, most of the young mothers in our study seemed to perceive that, on the whole, their families and communities did not socially reward them in any way.

In the earlier studies, ethnographers often found that families’ disapproval of teenage motherhood had a moral basis. According to life course theory, people can violate age norms in two ways: Either their chronological age is outside the normatively accepted range for a given transition, or they are making a transition in the normatively “wrong” order compared to other transitions (Settersten 2004). In interviews at our site in 1989 (Jacobs 1994), many young mothers reported that their families focused their disapprobation on the ordering of transitions: that teens were having sex and becoming parents before marriage. For example, an 18-year-old black participant in [author’s] study said,

I wasn’t using birth control. I was afraid that my parents would find it and I would get in trouble for having sex. They were very strict and never wanted anybody to have sex or go out. My mom was always telling me not to have sex, especially when my sister got pregnant a year before I did. She said, “Don’t have sex because it’s fornication and it’s sin.” She said, “Wait until you get married,” but I was already having sex. She was real ashamed of me when I got pregnant.

In our study, the disapproval of teenage motherhood was at least as strong as in this example, but its basis was practical, focused on the girls being too young to provide for a child and on the ordering of parenthood before finishing school and achieving financial independence. Participants rarely told us that people had a moral objection to premarital sex, as in the example above. This practical disapprobation may have arisen from a well-founded concern that the resource-strapped family would need to provide for the teen and her child. While in some cases the idea of a new baby made family members happy, the idea of a teenage daughter in their family becoming a mother almost always engendered anger and disapproval. Many of the mothers talked about family members reacting with rage and severe disappointment when they first found out about the pregnancy. These reactions, however, frequently shifted to milder disapproval or even tolerance with the birth of the child. Destiny, a 16-year-old multiracial mother, recalled breaking the news of her pregnancy to her parents:

Interviewer: Why were you afraid to tell your mom?

Because they would have beat me. They were mean to me, they were really mean. They would never let me go out and have fun. They wouldn’t let me go to the movies or even leave the block, even leave the front yard. They were so strict. They were just really strict. And I was just really scared to talk to them, even about birth control. When I told my mom I was pregnant, she was like, “Why didn’t you ask me about birth control?” I was like, “Me ask you for birth control? You’re so mean! Why would I ask you about it?” I was just afraid to talk to them. … I was expecting them to be really upset, but they weren’t. They were more disappointed, which is worse. I don’t like my parents to be disappointed.

Interviewer: They were disappointed about you being pregnant? That you had had sex at all?

I think—I don’t know, really. I think that I was pregnant, not so much that I had sex, but that I was pregnant, because they knew—they thought that my life was coming to an end. I told them, “It’s not. I can still go to school. I can still do everything.”

The practical basis for disapproval of teen parenthood is reflected in Destiny’s response. Similarly, Barbara recalled her family’s reaction to the news:

I was staying with my auntie at the time, and I was sick, and she asked if I was pregnant. I said no. She bought me a test, took it home, I was on the phone with my boyfriend. She came down and said, “You’re pregnant,” and I started crying, “Oh, my God.” I didn’t know what to do. But she said, “I’ll help you, but you can’t have that baby here. You have to have your [own] place by the time that baby comes.” Everyone was disappointed because they thought I was about to go to Job Corps, but they were OK.

As in Barbara’s case, many families were disappointed because they expected their teenage children to achieve career success, and parenthood was perceived as disrupting those plans. Barbara’s aunt was not even willing to provide housing for mother or child after the birth, but insisted on Barbara’s financial independence. The norm that teens like Barbara appear to violate discourages burdening one’s family with material demands and a compromised socioeconomic future.

By reducing these demands and staying on track for some degree of socioeconomic success, some young mothers can reduce the negative sanctions they experience from family members. Tiffany is an example of this phenomenon:

At first, when I was pregnant, it was really hard. I was like the broken child in the family, like, I was the one that was just a mistake, like I did everything wrong. But after the baby was born, everybody just saw the baby and had a different view … especially since they see that I do take care of my baby. Because they thought that because I got pregnant that I wasn’t responsible, that I wasn’t gonna take care of the baby, that I wasn’t gonna do anything for him, that I was just gonna be lazy and end up in a mess. But they saw that I go to [name of school] and they’ve seen that I’m working really hard to get all my assignments in. I’ve taken him to all his appointments, all his shots are up to date. So every time he’s sick, I’m the one who takes care of him.

The fact that Tiffany’s family members’ reactions changed when she turned out not to be a huge burden and succeeded in school suggests that practical concerns drove their disapprobation.

How does family members’ disapproval matter for teenage mothers? In respondents’ optional open-ended comments from a national survey of adults, Mollborn (2009) found that a norm prescribing family support of teenagers often encourages family members to provide resources even if they disapprove of their daughter’s situation. Indeed, many family members in our study who reportedly disapproved of the teenage birth still provided some support to the young mother and child. Adriana explains this phenomenon as follows: “It’s like if I was living there and I was just by myself. I’m still under 18, so they still have to support me. [Having her daughter in the house is] just a little extra plus.” Brooke, a 20-year-old white mother of two, told us how negatively her grandfather reacted to her first pregnancy, both because she was young and because her boyfriend came from Mexico. Despite his objections, though, during her baby’s infancy he was the only family member who provided her with free housing and child care.

Though a competing norm of family support counteracted negative social sanctions to some extent, many mothers told us that disapproving family and community members withheld or placed strong conditions on support that they otherwise might have provided more freely. Michelle, who had her daughter at 15, was disappointed with her mother-in-law’s lukewarm involvement with her granddaughter. Michelle is one of many mothers for whom an external issue such as drinking, poor health, or incarceration exacerbated a lower-than-expected level of support:

Interviewer: Who isn’t helping that you thought would be helping?

His mom. And a lot of it with her, her drinking of course, and I know that if she wouldn’t drink as much, that she would help out. She’d say, “Hey, have the kids come over.” She does say that now, but they can only stay there for an hour or two and then she’s like fed up. You can tell. … She never really bought my daughter anything. The most reason that I was so upset with her was because for my daughter’s first Christmas, she did not buy her anything, and she bought her other grandkids stuff. That really upset me. After that, that’s when I moved out. I felt like my daughter was kind of like the—I don’t know, I felt like she—like if maybe me and [the father] had a daughter together and it wasn’t his kid. That’s kind of what I felt like. I’m like, “This is your son’s daughter.” … [I]f we need help, I know that we can’t call her. And I feel like it’s always my family doing that and his sister, and that’s it.

Lack of support from a single family member may not make a great difference in a teenage mother’s life, but when several key people are unhelpful or struggling with problems of their own that make it impossible for them to provide reliable support, she may experience severe lack of resources. The situation of Olivia, a Hispanic 18-year-old mother who attended school full time and also worked for pay, illustrates how competing demands within the family can lead to fewer available resources:

I thought my dad was gonna be more helpful at first, but then I realized, he has another family also, so it might be a little different than I thought. …He has a baby of his own. And then my brother’s baby is not even a month old. … And then three of my other cousins are pregnant.

As these findings show, far from providing social incentives for early fertility, the families’ and communities’ norms against teen childbearing affected teen mothers’ life courses in negative ways.

Whether or not they have been driven by shifts in norms about teen parenthood, demographic changes in the experience of teen childbearing have created social strains for young mothers. Since the mid-1990s, the teenage birth rate has decreased sharply among Latinas, African Americans, and whites alike. This means that motherhood is a less common experience for teenagers now than in the past. The majority of our participants did not talk about teen motherhood as a “normal” experience to have, and many felt socially isolated. In this way, macro-level demographic trends have shaped the everyday experiences of young mothers.

It was rare for our participants to report being friends with other teen mothers, unless they had gotten to know others in their situation because of attending the school for pregnant and parenting teens. Occasionally a participant would identify other young parents in her extended family, like Olivia above, but this was the exception rather than the rule. The experiences of Melissa, whose school experiences were described above, exemplify those of many others in several ways. Like many other participants, Melissa was attending a mainstream public school when she got pregnant:

I was the pregnant freshman girl. So I was always pointed out. … It was negative. Like, I don’t know, people right away started calling me a “ho” [whore], and I knew I wasn’t, because I had lost my virginity to him and stuff, but it was just—I don’t know, people point you out so much, and every time you go down the hallway, they’re like, “Oh, there goes the pregnant girl!” So it was hard. But my friends were really supportive. Like, first period they would always buy a burrito for me so I had breakfast, and they would bring in snacks in between, so that was nice. But other people really got upset, and I don’t even know why. It was none of their business.

Melissa’s account of initially supportive friends and hostile schoolmates was typical of many participants. However, these friends did not provide significant help to her after she had her child. It was very rare for young mothers to cite friends as important sources of support in their lives. Interestingly, though, participants did not include friends when asked who is not helping them as much as they expected, which suggests that they expected their friends to provide little support. This reflects the socially isolated experience of teen motherhood today.

Short-Term and Long-Term Consequences of Teen Motherhood

The teen mothers in our study and their children are facing daunting economic and social strains. Social programs, their families, and their children's fathers typically provide limited and tenuous support at best. At the same time, many of their fellow Americans strongly disapprove of their life situations, resulting in strained social interactions and limited emotional support as well as the potential for increasingly negative sanctions from institutions such as schools. We found that these economic and social strains made young mothers and their children very vulnerable in the short term. Even though most mothers were receiving at least some types of substantial support from partners or family members, some of their basic needs (such as regular and nutritious food, warm clothing, reliable housing, transportation, diapers, or child safety items such as a car seat, crib, or high chair) were going unmet.

Young mothers’ need for clothing for themselves and especially for their growing children was particularly keen. Most of the interviews took place in the fall, and the coming Colorado winter was on several mothers’ minds because they did not have coats for themselves or their children. Indeed, as the weather turned cold we interviewed a number of mothers who arrived in nothing heavier than a sweatshirt. Participants had a clear sense of the competing demands on their budget and the impossibility of meeting each demand. When asked if there were things for her children she would like to do but could not at that time, Cecilia (a 19-year old Hispanic mother of one) said:

Interviewer: Are there things you want to do for your child that you're just not able to do right now?

Buy him shoes. [laughs] It’s kind of hard when we have to pay bills, car insurance and stuff like that.

Lucy, a full-time student, echoed these concerns in her autumn interview:

Clothes is hard. … ‘Cause I did work in December of last year to only February, and she did have clothes for the summer, but now that I’m not working and her dad’s not working or anything, she does need clothes for the [winter], ‘cause all she does is have summer clothes, and that’s all she’s been wearing to school. I tell my mom and dad, but since they’re getting their hours cut, they can’t really helpme out. …[My daughter] did have a jacket, but she grew out of it. And shoes. She was in size 4 for just a year and she grew out of it. … Now she’s in size 5. But she still complains her foot hurts.

Basic transportation was another serious concern for a substantial minority of mothers, who talked about not being able to afford a car, not having money to repair their broken car, or anticipating a coming breakdown they could not afford to fix. Asking for rides from family members and friends caused anxiety for many of these participants. Frances, a Latina participant who became a mother at 17, described her complicated transportation situation.

Interviewer: What about transportation for you and your daughter?

I think that’s been the biggest problem. Oh, yeah, especially because I was so young. I couldn’t even get a driver license, so I couldn’t even drive if I had a car.

Interviewer: What about now?

… A year ago I took out a car, so I had my own car payments and all that stuff, but last month I had a car accident. My car was totaled, so right now I’m driving a rental car that insurance is paying for. … The rental car is only for this week, and then I’m gonna have to figure out how to get to work. I think my husband’s gonna give me a ride, but he’s gonna miss work, because he’s gonna have to be here. We’ll figure a way.

The school that 19 of our 55 participants attended has a “store” where students can use attendance credits to “buy” basic items like diapers and used children’s clothes. Mothers repeatedly brought up their need for diapers and food and the staff’s flexibility in providing for mothers without these key resources. As our study drew to a close and the economic crisis deepened, a school staff member told us that the school had unexpectedly decided to open up a food bank for its students. Because local food banks were running out of supplies, some students had started telling their teachers that they were not eating between one school lunch and the next. Many students’ heavy reliance on the school for diapers and food suggests that these needs might go unmet otherwise. While only some participants addressed this explicitly, it seemed that considerable resource strain was being placed on entire networks of family members who were trying to support the teen and her child. Assuming that most families do not want their teenagers to go without coats or babies to go without diapers, these material deficits suggest that families’ resources, and not just those of the teens, were strained past the breaking point.

We have already seen that norms against teenage childbearing have very real consequences for teenage mothers in terms of negative interpersonal and institutional sanctions. In part because of their disadvantaged backgrounds and in part because of these sanctions, most of the young mothers were struggling to keep their families afloat financially and to continue striving towards their educational and career goals. Our participants’ short-term situations looked bleak. But researchers studying teenage mothers from past generations (e.g., Furstenberg 2007; Taylor 2009) have often found that the long-term consequences of teenage childbearing are less severe than those in the short term. Given their lack of money, child care, housing, and other important resources, will this still hold true for many of the teenage mothers we interviewed?

Our study does not include longitudinal data to assess this issue directly, but information about the participants’ current situations can help us make an informed guess. Nearly all of the young mothers had concrete career plans and a fairly clear, hopeful picture of where they saw themselves a year from the time of interview. Many of the participants were highly invested in their education, often explicitly for the sake of their children. When asked why she wanted to be in school, Cecilia replied, “My son. I want him to have a better future. I want to give him a place to live. I want him to look at me like a role model.” Participants were often aware of what they needed to do in order to implement these concrete career plans. For example, Olivia reported:

I want to be an RN [Registered Nurse], and coming here would help me, because I need to graduate in time to go to school when I need to, and now here, they’re gonna send me to [name of school], go get my CNA [Certified Nursing Assistant] and then I can get my RN quicker, after my CNA, so I don’t have to take as many classes.

Many mothers also knew exactly which practical obstacles lay in the path of their achievement. Money, transportation, and child care were frequently significant barriers. The extraordinary lengths to which many students, such as Adriana, were going in order to continue their schooling underscores the value they placed on education:

I can’t get TANF, I can’t get housing, I can’t get any kind of help because I’m not 18. That’s one of the biggest obstacles ever, ‘cause if I could live closer to the school in some of the housing places, it would be way easier to get to school. If I come to school on the bus, ‘cause I don’t have a car right now, I have to catch four buses to get to school, ‘cause I live in [name of neighborhood].

Interviewer: So you’re on the bus almost two hours?

Yeah. My daughter’s been at her grandma’s house this whole week because I don’t have a car so that I can take her to day care. And her day care is not here, so I have to take her somewhere else and then come here, so I would have to be at the bus stop at, like, 5 in the morning. So she just stayed at her grandma’s this week until I get a vehicle so that I can take her to day care and then come to school. But either way, I know I’m not gonna stop coming to school, even if it means for her to stay away from me for a little while, so that I can finish.

The question is whether this level of sacrifice is sustainable in the long run. Although most mothers did not address this concern explicitly, from their descriptions of their current lives, we concluded that they would be able to meet these goals only if their situations improved considerably and if they experienced no loss of support from the many people who were helping them. While some mothers will likely meet their goals by a combination of good luck and continued hard work, their struggles to succeed will be very challenging.

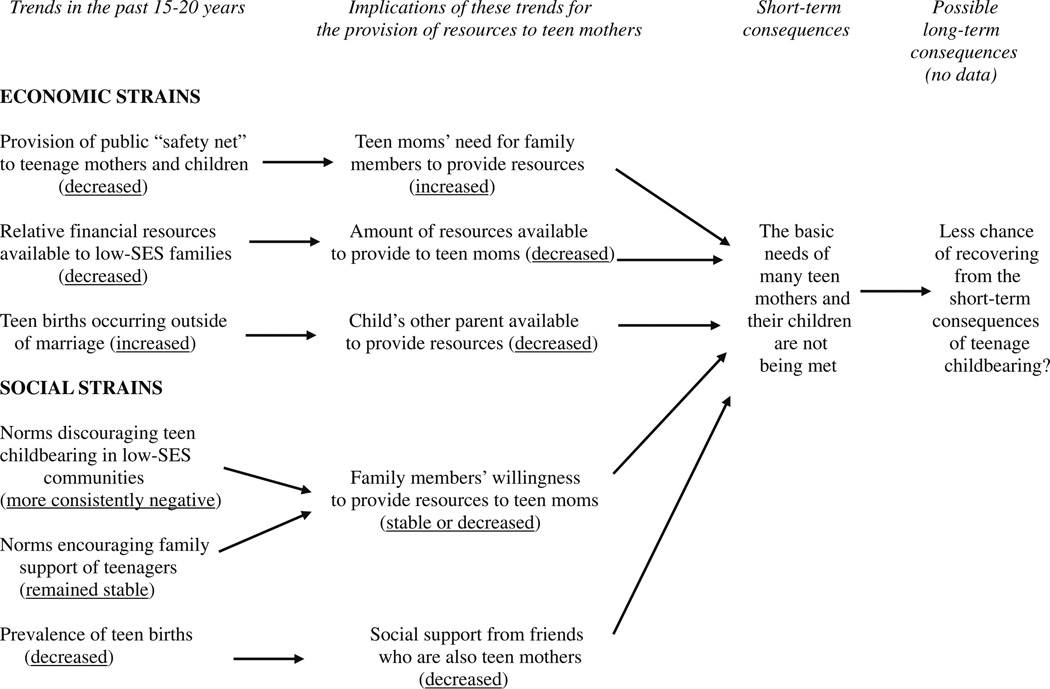

The relationships we identify between economic and social strains, their links to the availability of resources for teenage mothers, and both short-term and potential long-term consequences are illustrated in our conceptual model in Fig. 1. This figure summarizes the findings arising from our study, framing them in the larger structural and cultural trends described above. As the model shows, both economic and social strains lead to mothers ending up with low levels of resources, which create negative short-term consequences for themselves and their children that could lead to long-term problems.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of the everyday experiences of teenage mothers and their consequences

Conclusion

Based on interviews conducted in 2008–2009 with 55 current and former teenage mothers, our findings show that teenage mothers are experiencing two types of severe strain in their everyday lives. Economic strain is exacerbated by the decreased availability and low take-up rates of key social programs such as welfare, a downward creep in relative income and other resources in the lower segments of the socioeconomic spectrum, and very high rates of nonmarital births among young mothers. These structural and demographic forces have left many teenage mothers with fewer public sources of financial support, child care, and housing, making them more economically reliant on their families and communities. At the same time, teenage mothers usually do not have a spouse available to help meet the resource needs created by shrinking government support. Their family members may also have fewer resources available because of relatively poorer economic conditions for low-SES families.

Further, our findings suggest that social strains arising from young mothers’ violation of norms governing the appropriate timing of parenthood are another important factor in their everyday lives. Most of the young mothers in our urban, predominantly Latina and African American sample felt that their families and communities did not socially reward them in any way for having children. People’s reactions largely ranged from tolerating the pregnancy to openly disapproving of it. The basis for the norm was frequently more practical than moral, with disapproval stemming from concerns over economic and social security rather than sexual behaviors. Though a widespread norm that families should support their teenage children counteracted negative social sanctions to some extent, many disapproving family and community members, like broader U.S. society, withheld or placed strong conditions on support that they gave to the teenage mother and her children.

This combination of limited societal support of teenage parents and their children, the nonmarital context of teenage childbearing, an unfavorable labor market with rising child care costs, and social disapproval in our participants’ families and communities is putting many teenage mothers and their children in a very vulnerable position today. Although many participants are trying to improve their socioeconomic situations and their family members are providing support, their own and their children’s basic needs are sometimes going unmet. As a result, many of our participants are finding their ambitious career and educational goals hard to attain.

Our study’s findings speak to several debates and assumptions in the existing literature on teen parenthood. The quantitative literature discussed above has relied on data from past decades to document relatively mild long-term consequences of teenage motherhood. Our findings suggest that two aspects of this conclusion should be investigated when applying it to today’s teenage mothers: the assumption that the context of teen childbearing is similar now compared to in the past, and the assumption that young mothers will be able to improve their long-term socioeconomic prospects. We argue that the severe difficulties many young mothers are facing in today’s social and economic contexts suggest that the long-term socioeconomic improvement experienced by teenage mothers in the past may be more difficult to achieve. Although they are not generalizable, our findings suggest that future research using representative samples should address the issues we have raised with regard to the consequences of teenage motherhood in today’s structural and cultural contexts.

Similarly, the existing qualitative literature is based primarily on older data. Studying teen mothers in past decades, ethnographers disagreed about whether young mothers’ communities encouraged early childbearing. At least for teen mothers from various communities in the Denver area, our study finds no such encouragement today. The norms discouraging teen parenthood described by our participants are focused on practical concerns related to the increased resource needs and decreased socioeconomic prospects that their families think accompany teenage motherhood, rather than moral concerns about sex or pregnancy as in the past. Our findings speak to the need to reconsider the lived experience of teen parenting using newer ethnographic data.

Besides extending ideas about the effects of age norms to include systems of competing norms and documenting consequences of these norms for mothers’ lives, our findings address another key question in the study of teenage parenthood: the debate about the role of young mothers’ social backgrounds, educational experiences, and socioeconomic resources prior to becoming pregnant (selection) versus the experience of early parenthood (causality) in understanding the life outcomes of young parents. Negative sanctions tied to violating age norms could be one way in which teenage parenting has a causal effect. As many quantitative researchers have done, we find evidence that both selection and causality are important for understanding our participants’ life situations. But we go a step farther, finding that the negative consequences of early childbearing are exacerbated by the mothers’ preexisting disadvantages that make them more vulnerable to the effects of social disapproval on the social and material resources that are made available to them.

Our findings also have implications for life course theory (Elder 1994), which is a key theoretical perspective for understanding teen parenthood. According to this perspective, historical changes, structural and cultural contexts, and the linking of individuals’ lives should all be considered when assessing the consequences of a transition to parenthood that prevailing social norms label as “too early.” The importance of the timing of life transitions, which is a core aspect of the life course perspective, is evident in our young mothers’ stories. Beyond the social sanctions they face for violating age norms about the timing of the transition to parenthood, young mothers struggle because they have given birth at a time when they are also striving to make other successful transitions to adulthood such as finishing school, starting a career, moving out of their parents’ home, establishing financial independence, and building long-term intimate relationships. The simultaneity of these tasks makes parenting overwhelming for many of our participants.

Our research demonstrates in multiple ways the importance of another core principle of the life course perspective: “linked lives” (Elder 1994). Not only are the children’s lives inextricably linked to their mothers’, but the young mothers are fundamentally reliant on their families and their children’s fathers for meeting their own and their children’s basic needs. In a time when many governmental programs are withdrawing their support, the links between the lives of young mothers and their families and partners represented by informal “safety nets” are even more critical for their futures. Whereas earlier research found very high levels of extended family involvement in the care and support of young mothers’ children (Burton 1990; Stack 1974), the teenage mothers with whom we spoke most often described situations in which extended family members provided substantial help, but the bulk of the responsibility for their children was placed on the mother. This is a striking difference from, for example, the “grandparental child-rearing system” recounted in Burton’s (1990) ethnographic research with low-income African American families in the 1980s. Brewster and Padavic (2002) found quantitative evidence that black families are often stepping in when support of mothers is most needed, but are providing less child care than they once did. Women’s higher rates of labor force participation may be driving this change. This suggests that at least in some demographic groups and communities, there has been a shift in the social meaning of teenage motherhood, which now entails more of the heavier burdens and responsibilities historically assigned to adult mothers but without the social approval and accumulation of resources that often accompany adult motherhood. The complicated power dynamics that play out within these relationships have very real consequences for teen mothers and their children.

Finally, this study has implications for policy. Our findings show that many teenage mothers and their children urgently need material support, yet social institutions and programs vary widely in their ability to provide it. For example, Medicaid is almost universally utilized among our participants, and they are very positive about its effect on their own and their children’s lives. Yet they often perceive that it is pointless even to apply for other much-needed supports like TANF or housing assistance. Given that most participants had clear career plans and the motivation to carry them out, the payoff from providing needed resources could be great. Knowing more about teenage mothers’ experiences with the educational system, government programs, and other social institutions may help policymakers create more effective programs to meet their needs.

As discussed above, most teen mothers in our study were struggling to make successful simultaneous transitions to parenthood and adulthood in today’s social and economic contexts. If the financial, demographic, and cultural strains identified here continue, the social and economic costs of teen childbearing could be more severe than those detected by less recent research. This has broad implications for policy, given the high prevalence of teen motherhood in the United States today. We found that the strain of supporting a young mother and child was felt by entire networks of family members. The current societal trend of transferring more of the burden of financial support onto families may mean that large swaths of the most disadvantaged groups in our society will be increasingly burdened by these resource strains. The high teen birth rate, in combination with social disapproval of teen parents, could mean a decrease in social cohesion in disadvantaged neighborhoods because of the social exclusion of young parents and their families. While none of these consequences are certain, attention must be paid to these continually shifting social contexts when considering the lives of teen mothers and their families.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted with support from the University of Colorado’s Innovative Grant Program and Undergraduate Research Opportunity Program. We thank Devon Thacker, Leith Lombas, Nicole Moore, Aleeza Zabriskie, and members of the Sociology junior faculty reading group for their assistance, as well as the study’s participants for sharing their time and stories with us.

Biographies

Stefanie Mollborn is an assistant professor in the Department of Sociology and the Institute of Behavioral Science at the University of Colorado Boulder. She conducts multimethod research on teen parenthood, focusing on its consequences for teen mothers and fathers and their young children and on social norms about teen pregnancy and parenting.

Janet Jacobs is Professor of Sociology and Women and Gender Studies at the University of Colorado. Her research focuses on the social psychology of gender, ethnicity and religion, and collective memory. She has authored numerous books, including Divine Disenchantment: Deconverting from New Religious Movements; Victimized Daughters: Incest and the Development of the Female Self; Hidden Heritage: The Legacy of the Crypto-Jews, and Memorializing the Holocaust: Gender, Genocide and Collective Memory. She is currently researching teen pregnancy and adolescent development.

Footnotes

One pilot interview, recruited through a personal contact, was conducted in the first author’s office.

All names have been changed to keep the participants’ identities confidential, and racial/ethnic identifications are based on the participant’s own terminology.

These ideas were not without their detractors; for example, Kaplan (1997) found in her ethnographic research that black grandmothers frequently disapproved of their granddaughters becoming teenage mothers.

References

- Arons Jessica. [Accessed August 17, 2009];Lifetime losses: The career wage gap. 2008 http://www.americanprogressaction.org/issues/2008/pdf/equal_pay.pdf.

- Banthin J, Cunningham P, Bernard D. Financial burden of health care, 2001–2004. Health Affairs. 2008;27(1):188–195. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.1.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewster KarinL, Padavic Irene. No more kin care? Change in black mothers' reliance on relatives for child care, 1977–94. Gender and Society. 2002;16(4):546–563. [Google Scholar]

- Burton LindaM. Teenage childbearing as an alternative life-course strategy in multigeneration black families. Human Nature. 1990;1(2):123–143. doi: 10.1007/BF02692149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]