Abstract

Background and aims

Cross-sectional studies suggest that Obstructive Lung Disease (OLD) and smoking affect lean mass and mobility. We aimed to investigate whether OLD and smoking accelerate aging-related decline in lean mass and physical functioning.

Methods

260 persons with OLD (FEV1 63±18 %predicted), 157 smoking controls (FEV1 95±16 %predicted), 866 formerly smoking controls (FEV1 100±16 %predicted) and 891 never-smoking controls (FEV1 104±17 %predicted) participating in the Health, Aging and Body Composition (ABC) Study were studied. At baseline, the mean age was 74±3 y and participants reported no functional limitations. Baseline and seven-year longitudinal data were investigated of body composition (by Dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry), muscle strength (by hand and leg dynamometry) and Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB).

Results

Compared to never-smoking controls, OLD persons and smoking controls had a significantly lower weight, fat mass, lean mass and bone mineral content (BMC) at baseline (p<0.05). While the loss of weight, fat mass, lean mass and strength was comparable between OLD persons and never-smoking controls, the SPPB declined 0.12 points/yr faster in OLD men (p=0.01) and BMC 4 g/yr faster in OLD women (p=0.02). In smoking controls, only lean mass declined 0.1 kg/yr faster in women (p=0.03) and BMC 8 g/yr faster in men (p=0.02) compared to never-smoking controls.

Conclusions

Initially well-functioning older adults with mild-to-moderate OLD and smokers without OLD have a comparable compromised baseline profile of body composition and physical functioning, while seven-year longitudinal trajectories are to a large extent comparable to those observed in never-smokers without OLD. This suggests a common insult earlier in life related to smoking. 3

Keywords: Obstructive Lung Disease, Body Composition, Aging

INTRODUCTION

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) affects approximately 14% of older adults and is related to increased immobility, hospitalizations and resulting health care costs [1]. COPD is characterized by irreversible airflow limitation and is associated with an abnormal inflammatory response of the lungs mainly to cigarette smoke [2]. It has been increasingly recognized as a disease with marked extrapulmonary manifestations such as muscle wasting and weakness, osteoporosis and cardiovascular disease [3], in which systemic inflammation is thought to play an important role [4, 5]. It remains unclear, however, if these systemic manifestations are co-morbid conditions related to a common noxious exposure or if these are systemic consequences of the disease itself.

So far skeletal muscle weakness and wasting are the most studied and established extra pulmonary determinants of impaired mobility and increased mortality in COPD [6]. Putative pathophysiological mechanisms of altered body composition and physical functioning in COPD have originated from cross-sectional studies [7–10] and from longitudinal case studies without appropriate control groups [11–14]. However, since body composition changes and dysregulation of inflammation are also common with aging [15, 16] and since studied COPD populations often consist of older adults (60+), inclusion of matched non-COPD control groups is crucial to unravel the effect of airflow obstruction on the pattern and progression of changes in body composition and physical function, as well as the potential modulating role of systemic inflammatory markers. To our best knowledge, such studies are currently lacking. Cross-sectional studies in healthy smokers have suggested detrimental effects of smoking on skeletal muscle function [17, 18]. Increased systemic levels of pro-inflammatory markers were observed in healthy smokers [19], but also in former smokers [20]. Collectively, these data suggest that also in the absence of chronic airflow limitation, smoking may enhance skeletal muscle wasting and accelerate the decline in physical functioning, and that systemic inflammation could be a modulator.

We hypothesized that older adults with obstructive lung disease (OLD) and smokers with normal lung function have accelerated loss of lean mass and physical functioning compared to a never-smoking population. Systemic inflammatory markers could contribute to the association with body composition and physical functioning. We therefore examined seven-year longitudinal changes in body composition and physical functioning in older persons with OLD and in a non-OLD population stratified by smoking status.

METHODS

Study population

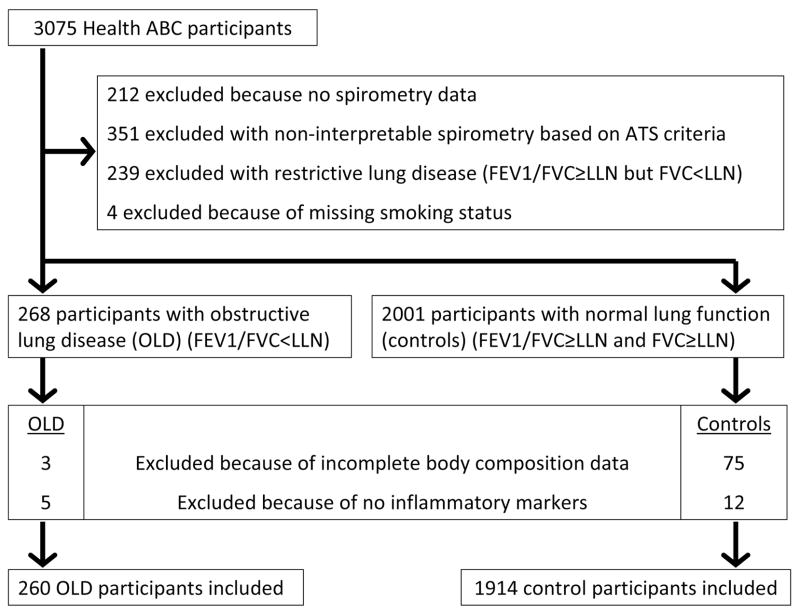

This study was performed in persons participating in the Health, Aging and Body Composition (Health ABC) study. This is a longitudinal study of 3,075 well-functioning black and white men and women between the ages of 70–79 years residing in and near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and Memphis, Tennessee. Baseline data was obtained in 1997/1998 through in-person interview and clinic based examination. Inclusion criteria were no reported difficulty walking a quarter mile, climbing 10 steps without resting, or performing mobility-related activities of daily living. Exclusion criteria were any life-threatening condition, participation in any research study involving medications or modification of eating or exercise habits, plans to move from the geographic area within 3 years, and difficulty in communicating with the study personnel or cognitive impairment. The Health ABC study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the clinical sites. Written informed consent was obtained for all participants. The current study presents an analysis of the Health ABC dataset using 7-year follow-up data from participants who met the criteria for Obstructive Lung Disease (OLD) (n=260) and control participants with normal lung function (n=1914). Participants with missing body composition measures at baseline and those with no measures of systemic inflammatory markers were excluded (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Flow chart of participant selection at baseline.

ATS, American Thoracic Society; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; LLN, lower limit of normal; OLD, obstructive lung disease.

Measures

Lung function, smoking status and smoking history

Lung function was assessed according to international standards as previously reported [10]. OLD was defined at baseline as reduced (i.e. < lower limit of normal, LLN) Forced Expiratory Volume in 1 s (FEV1)/Forced Vital Capacity (FVC) as determined by age, sex, and race-normalized values [10, 21, 22]. Cigarette smoking status (smoker, former smoker, never-smoker) was recorded based on self-report. At baseline, smokers, former smokers and never-smokers without OLD (i.e. FEV1/FVC≥LLN) were designated as the smoking controls, formerly smoking controls and never-smoking controls, respectively. Participants with restrictive lung disease (FEV1/FVC≥LLN but FVC<LLN) were excluded. At baseline, the number of pack years smoked (1 pack year = 20 cigarettes/day for 1 year) was obtained based on self-report.

Lung function was repeated in Years 5 and 8. Participants with valid lung function measures both at baseline and in Year 5 and/or 8 were included in the analysis of lung function decline. Consequently, lung function decline could be analyzed in n=1658 participants over a mean (SD) period of 6.2 (1.3) years including 2.6 (0.5) valid measurements per participant.

Body composition

Height was measured using a wall mounted stadiometer. Body weight was assessed to the nearest 0.1 kg using a standard balance beam scale and body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight / height2 (kg/m2). Weight was measured in Years 1 to 6 and 8. Whole body dual energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA, Hologic 4500A software version 8.21, Waltham, MA) was applied to retrieve whole body fat mass, lean mass, leg lean mass (left and right leg were summed) and bone mineral content (BMC). DXA measurements were performed in Years 1 to 6 and 8.

Muscle function and mobility

In Years 1, 2, 4, 6 and 8, maximal isokinetic strength of the quadriceps muscle was assessed by a Kin-Com 125 AP Dynamometer (Chattanooga, TN, USA) at 60°/s. The right leg was tested unless there was a contraindication. The maximum torque was taken from three reproducible and acceptable trials. Participants with a systolic blood pressure ≥200 mmHg or a diastolic blood pressure ≥110 mmHg or who reported a history of cerebral aneurysm, cerebral bleeding, bilateral total knee replacement, or severe bilateral knee pain were excluded from testing (12.7% of original cohort) [15]. As a consequence, baseline measures for quadriceps strength were available for n=228 OLD participants and n=1730 controls. Hand grip strength was measured using a Jamar Hydraulic Hand Dynamometer at baseline and in Years 2, 4, 6 and 8. The maximum values of the right and the left hand were summed from two trials. In Years 1, 4 and 6, lower extremity function was assessed using the SPPB (Short Physical Performance Battery) [23, 24]. The battery consists of a test of gait speed, standing balance, and time to rise from a chair five times. Each item was scored using a five-point scale (0 = inability to complete test, 4 = highest level of performance) leading to a combined 0–12-point summary scale.

Inflammatory markers

At baseline, measures of the cytokines interleukin-6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were obtained from frozen stored plasma or serum (see for further details [25]).

Covariates

At baseline, clinic site, age, race (black/white), oral steroid use, calcium suppletion and Vitamin D suppletion were based on self-report. Prevalent health conditions (diabetes, cardiovascular disease and depression) were assessed based on self-report and medication inventory. Physical activity in the preceding seven days was assessed at baseline by questionnaire [26, 27].

Statistical analyses

Differences in descriptive characteristics at baseline between OLD persons, smoking controls, formerly smoking controls and never-smoking controls were tested using ANOVA for continuous variables, χ2 for categorical variables and Kruskal-Wallis test for continuous variables with skewed distributions. Post-hoc comparisons were performed applying Bonferroni correction for multiple testing. Change in lung function could be calculated from a maximum of three time points only, hence per participant simple linear regression was applied to examine the yearly change (slope) in lung function. Subsequently, the mean slopes were tested between the study groups using ANOVA. The longitudinal data on body composition and physical functioning were analyzed using multilevel regression models, allowing for the intercepts and slopes to vary between the four groups. This type of analysis takes into account the intraindividual correlation between repeated measurements and allows the inclusion of participants with incomplete data at follow-up. Therefore, no imputation of missing data was applied. The primary model included group (OLD, smoking controls, formerly smoking controls, never-smoking controls), age, race, clinic site, examination year (time), oral steroid use (yes/no), calcium suppletion (yes/no), vitamin D suppletion (yes/no), cardiovascular disease (yes/no), diabetes (yes/no), depression (yes/no), physical activity, and an interaction term with time for all of these variables. The reported slopes are the coefficients of the interaction term group*time in which the never-smoking controls served as the reference group. In the second model further adjustment was made for IL-6, TNF-α and CRP and their interactions with time. There were no significant interaction effects between race and clinic site with the group variable on changes in body composition or physical functioning (p>0.05). Sample size considerations precluded examination of the effect of smoking status within the OLD group. The current analyses were performed for men and women separately because the gender distribution across the study groups was significantly different (p<0.001), which was most pronounced in the formerly smoking controls and never-smoking controls.

A small proportion of participants did not have measurements of body composition and physical functioning due to missing clinic visits while being alive. To examine the sensitivity of the results from the multilevel regression analyses to these missing observations, we used a joint model for the primary outcomes and missing probabilities [28]. Statistical analyses were performed using PASW Statistics 17.0 (SPSS inc. Chicago, IL). A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Baseline characteristics are presented in Tables 1 (men) and 2 (women). The degree of airflow limitation in OLD persons was mild (FEV1>70% predicted), moderate (FEV1 50–70% predicted) and severe (FEV1<50% predicted) in 32%, 38% and 30% of cases in men and in 36%, 41% and 23% of cases in women, respectively. The proportion of smokers, former smokers and never-smokers in the OLD persons was 63%, 28% and 9% in men and 46%, 27% and 27% in women, respectively. Compared to never-smoking controls, the decline in FEV1 was lower in OLD men (−38±6 vs. −57±3 mL/yr, p=0.038) but not in OLD women (−33±5 vs. −40±2 mL/yr, p=0.446) (Supplemental Table 1). The formerly smoking controls had abstained from smoking for 25 (14) years. The prevalence of co-morbid conditions was not different across the groups (p>0.05). Persons with OLD and smoking controls had comparable levels of physical activity as the never-smoking controls (p>0.05). In men, OLD persons had increased CRP and IL-6, and smoking controls had increased IL-6 compared with never-smoking controls (p<0.05). In women, smoking controls had increased IL-6 compared to never-smoking controls (p<0.05).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of menin the Health ABC Study according to Obstructive Lung Disease (OLD) status and smoking status.

| OLD (n=150) | Smoking controls (n=74) | Formerly smoking controls (n=534) | Never-smoking controls (n=301) | Overall p-value | Significant post-hoc comparisons† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | |||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, y | 73.4 (2.9) | 73.0 (2.5) | 73.7 (2.9) | 74.0 (2.8) | 0.06 | - |

| Race, % white | 52 | 35 | 70 | 65 | <0.001 | AC, BC, BD |

| Site, % Memphis | 60 | 50 | 47 | 51 | 0.013 | AC, AD |

| Physical activity, kcal/kg/wk* | 68 (37–105) | 59 (35–125) | 67 (40–114) | 72 (39–114) | 0.68 | - |

| Co-morbidity, steroid use, calcium and vitamin D suppletion | ||||||

| Depression, % | 7 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 0.22 | - |

| Cardiovascular disease, % | 25 | 24 | 30 | 23 | 0.10 | - |

| Diabetes, % | 13 | 15 | 16 | 15 | 0.91 | - |

| Oral steroid use, % | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0.49 | - |

| Calcium suppletion, % | 5 | 7 | 7 | 9 | 0.35 | - |

| Vitamin D suppletion, % | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 0.63 | - |

| Lung function and smoking | ||||||

| FEV1, %predicted¶ | 61 (17) | 93 (12) | 100 (14) | 102 (15) | <0.001 | AB, AC, AD, BC, BD, CD |

| FEV1, L | 1.68 (0.50) | 2.47 (0.41) | 2.77 (0.50) | 2.78 (0.49) | <0.001 | AB, AC, AD, BC, BD |

| FEV1/FVC, ratio | 56 (7) | 73 (5) | 75 (5) | 77 (5) | <0.001 | AB, AC, AD, BC, BD, CD |

| Pack years, no* | 48 (26–64) | 48 (27–60) | 25 (10–41) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | AC, AD, BC, BD, CD |

| Systemic inflammatory markers | ||||||

| Interleukin 6, pg/ml* | 2.23 (1.59–3.58) | 2.46 (1.62–3.91) | 1.74 (1.18–2.70) | 1.68 (1.18–2.32) | <0.001 | AC, AD, BD |

| C-reactive protein, μg/ml* | 2.00 (1.21–3.51) | 1.54 (0.92–3.30) | 1.34 (0.88–2.39) | 1.30 (0.89–2.22) | <0.001 | AC, AD |

| TNF-α, pg/ml* | 3.13 (2.41–4.32) | 3.18 (2.34–4.37) | 3.34 (2.59–4.26) | 3.05 (2.43–4.00) | 0.23 | - |

Data are mean (SD) unless specified otherwise, significant p-values are boldface.

Median (IQR),

Corrected for multiple testing,

From reference equations [21]. FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

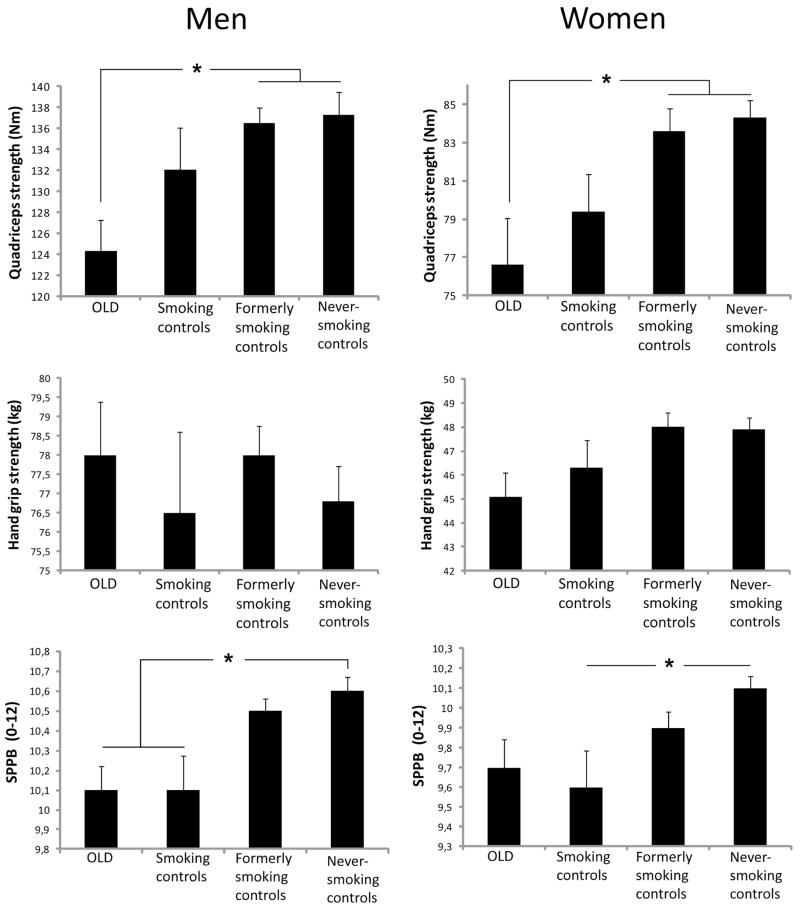

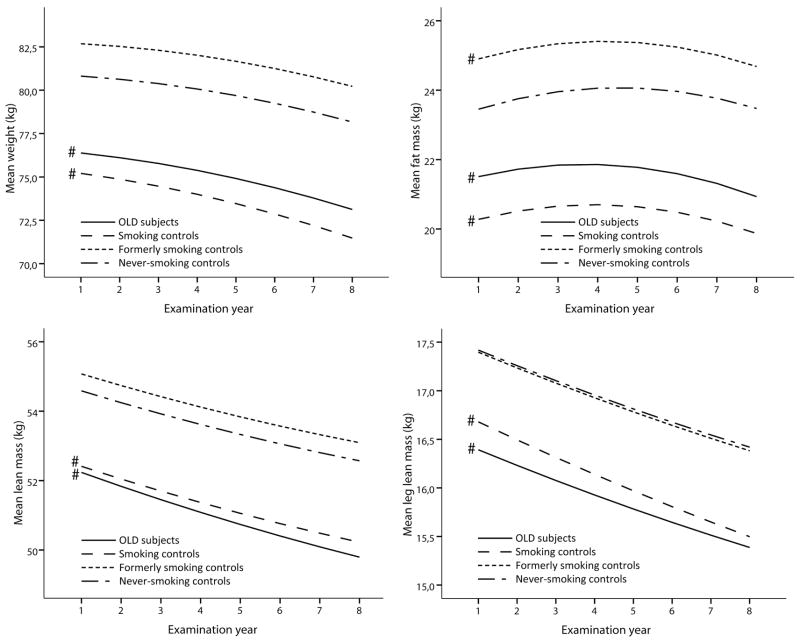

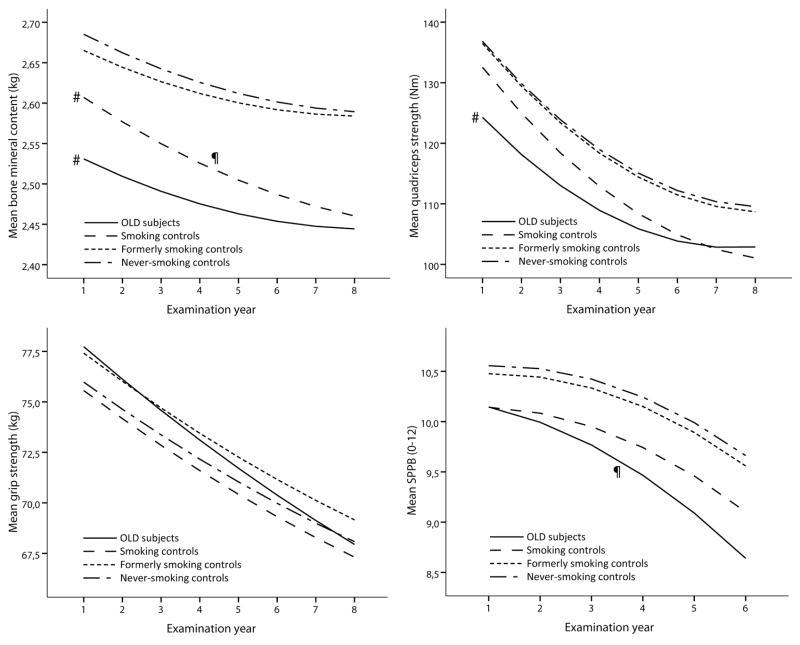

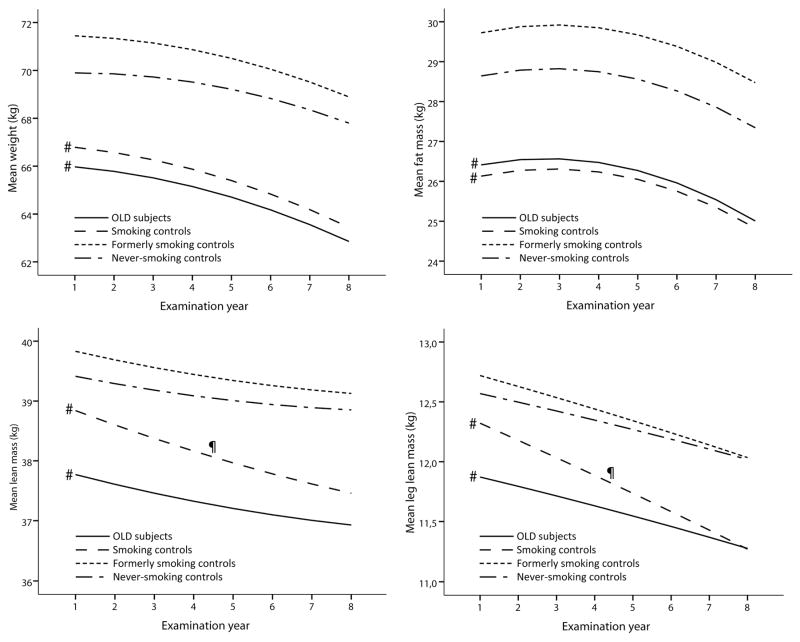

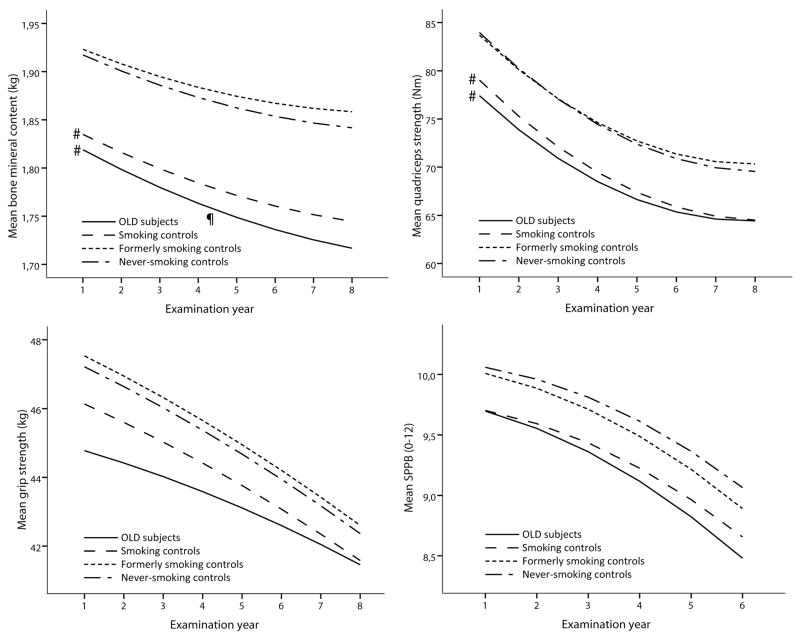

In both sexes, persons with OLD and smoking controls showed striking similarities regarding lower measures of body composition and physical functioning as compared to the never-smoking controls (Figure 2). In general, the adjusted intercepts from the multilevel models (Figures 3 and 4 and the corresponding Supplemental Tables 2 and 3) showed similar findings to the baseline comparisons in Figure 2. While at baseline large differences were observed in body composition and physical functioning, the rates of longitudinal change of weight, fat mass, lean mass and strength were comparable between OLD persons and never-smoking controls (all p>0.05), except for the change in SPPB in OLD men (p=0.01) and BMC in OLD women (p=0.02). In smoking controls, only lean mass declined faster in women (p=0.03) and BMC faster in men (p=0.02) compared to never-smoking controls, while the declines in weight and fat mass were comparable (p>0.05).

Figure 2. Baseline characteristics of body composition and physical functioning in men and women.

Data are mean ± SE. * p < 0.05.

OLD, Obstructive Lung Disease; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

Figure 3. Longitudinal course of body composition and physical functioning according to obstructive lung disease and smoking status in men*.

* Lines represent the mean predicted values adjusted for time, age, site, race, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, depression, physical activity, oral steroid use, calcium suppletion, vitamin D suppletion, time2, age x time, race x time, site x time, diabetes x time, cardiovascular disease x time, depression x time and physical activity x time, oral steroid use x time, calcium suppletion x time and vitamin D suppletion x time.

# Intercept significantly different from never-smoking controls, p<0.05.

¶ Slope significantly different from never-smoking controls, p<0.05.

OLD, Obstructive Lung Disease; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

Figure 4. Longitudinal course of body composition and physical functioning according to obstructive lung disease and smoking status in women*.

* Lines represent the mean predicted values adjusted for time, age, site, race, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, depression, physical activity, oral steroid use, calcium suppletion, vitamin D suppletion, time2, age x time, race x time, site x time, diabetes x time, cardiovascular disease x time, depression x time and physical activity x time, oral steroid use x time, calcium suppletion x time and vitamin D suppletion x time.

# Intercept significantly different from never-smoking controls, p<0.05.

¶ Slope significantly different from never-smoking controls, p<0.05.

OLD, Obstructive Lung Disease; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

Further adjustment for baseline systemic cytokines resulted in a modest attenuation of several outcome measures (Supplemental Tables 2 and 3). In particular, the lower baseline and faster decline of BMC in smoking control men (and to a lesser extent in women) was explained by the cytokines for 26% and 25%, respectively. The lower quadriceps strength in men and women with OLD was explained for 12% and 18% by the cytokines, respectively.

In additional analyses, pack years were added to model 1, which did not result in any major differences. Compared to the never-smoking controls, the formerly-smoking controls, smoking controls, and OLD persons had slightly higher probabilities of being missing along the seven years of follow-up. However, the trajectories of the outcomes essentially remained the same when we adjusted for missingness (not tabulated). The percentages of participants being alive at the year-8 visit were 62%, 66%, 77% and 85% for the OLD persons, smoking controls, formerly smoking controls and never-smoking controls, respectively.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we have shown striking similarities in body composition and physical functioning between older adult men and women with mild-to-moderate OLD and smokers with normal lung function. These were characterized by a markedly lower body weight, lean mass, fat mass, BMC and quadriceps strength compared to never-smoking controls. Interestingly, because longitudinal trajectories in the 8th decade of life were to a large extent comparable to those of their never-smoking controls, the large baseline differences persisted over a period of 7 years follow up. This suggests that a common insult related to smoking induced a divergent pattern earlier in life, which may not uniformly persist into old-age.

The unique design of the Health ABC Study enabled us to investigate for the first time the longitudinal pattern and progression of body composition changes and the decline in physical functioning simultaneously in persons with OLD and smokers without OLD in comparison to aging effects in a never-smoking control group without OLD. Furthermore, by design of the Health ABC Study, none of the participants had functional limitations at baseline, and likely as a result of this selection, physical activity and prevalence of comorbidity were comparable between the study groups. The Health ABC Study was therefore particularly of interest to examine the effects of smoking and OLD on body composition and physical functioning with aging. Our results may, however, not be generalized to all older adults nor to clinical COPD patients since study participants were 70–79 years old and well-functioning at baseline, and the OLD group was defined by lung function rather than a clinical COPD diagnosis. Therefore, it can not be ruled out that our data might underestimate “real” changes. Another strength of our study is that we carried out a sensitivity analysis to estimate the potential effect of missing observations on the observed trajectories. This effect was estimated to be small which, however, does not rule out that survival bias may have obscured our results. While we were unable to examine the effect of smoking status with the OLD persons due to sample size considerations, results between groups remained similar after further adjustment for pack years, suggesting that the observed differences are independent of the quantity of smoking.

We found that the decline in FEV1 was lower in OLD men compared to their never-smoking controls. Because this data was generated from a relatively low number of follow-up lung function measures we are careful in its interpretation, but it does suggest that longitudinal body composition and physical functioning trajectories in OLD persons in our study are not related to a faster decline in FEV1.

In OLD men, but not in OLD women, we found an accelerated decline in SPPB. This gender difference may be explained by a greater relative difference in leg lean mass and quadriceps strength between OLD persons and never-smoking controls in men than in women. This is in line with a previous report showing that the relation between a lower fat-free mass and physical disability was more pronounced in men with COPD [29]. A lower SPPB has been strongly related to subsequent disability and mortality [24, 30], and may thus be of clinical importance in particularly in men with OLD. Notably, despite a similar pattern of daily physical activity, quadriceps strength was much better able to discriminate between OLD persons, smoking controls and never-smoking controls than hand grip strength. Smoking control women had an accelerated decline in lean mass compared to never-smoking controls, which confirms previous cross-sectional data of a sarcopenic phenotype in older smoking women [31].

Systemic inflammation has been considered a key player in the extrapulmonary manifestations of COPD [5], and has been linked to muscle atrophy [32] and bone demineralization [33]. In the present study we indeed confirmed the presence of mildly elevated circulating cytokines in particularly OLD men but also in smoking controls. After further adjustment for systemic inflammatory markers we found little attenuation for the majority of outcome measures, but systemic inflammatory markers did explain 11–26% of the observed baseline differences in BMC, and explained 25% of the accelerated decline in smoking control men.

The observation that smoking cessation is associated with weight gain is well-known [34]. While this effect is mainly considered a relatively short-term effect (months) [35], former smokers in our study –who abstained from smoking for ~25 years– still showed a trend towards higher baseline weight, which was mainly due to higher fat mass. Apart from fat mass, body composition and physical functioning in former smokers were comparable to that of never-smokers, suggesting a high recovery potential from smoking-induced losses. As higher body weight and lean mass have been associated with better survival in COPD [36], it needs to be determined whether this recovery potential is as functional in the state of COPD. We found higher CRP in formerly smoking women, and borderline significantly higher TNF-α in formerly smoking men, which may be related to metabolic effects associated with fat abundance or altered fat distribution in obesity.

Although it was not part of our analyses, our data raise the possibility that low body and muscle mass may increase the risk of COPD development. In support of this, recent data from a large group of never-smokers from the Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease Study showed that the risk of COPD was significantly increased in those with a BMI<20 kg/m2, especially in women [37]. In the case of smoking-induced COPD, however, it remains to be investigated whether a compromised body composition related to smoking contributes to the risk of COPD development. Our observation that while our smoking controls had comparable pack years smoked as OLD persons and had a similarly compromised body composition but no airflow obstruction, indicates that it is not solely low body weight that would increases the risk of COPD development, but suggests that other factors such as genetic susceptibility to for example emphysema and associated wasting are important.

In conclusion, our study shows that smoking is not only an important risk factor in OLD etiology, but also adversely affects body composition and physical functioning. The individual contributions of impaired weight gain and accelerated weight loss and a potential role for cytokinaemic stress associated with smoking remain to be studied in comparable future longitudinal studies in middle-aged persons.

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of women in the Health ABC Study according to Obstructive Lung Disease (OLD) status and smoking status.

| OLD (n=110) | Smoking controls (n=83) | Formerly smoking controls (n=332) | Never smoking controls (n=590) | Overall p-value | Significant post-hoc comparisons† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C | D | |||

| Demographics | ||||||

| Age, y | 72.8 (2.8) | 73.7 (3.0) | 73.3 (2.8) | 73.5 (2.9) | 0.06 | - |

| Race, % white | 62 | 37 | 56 | 59 | 0.001 | AB, BC, BD |

| Site, % Memphis | 42 | 43 | 46 | 51 | 0.11 | - |

| Physical activity, kcal/kg/wk* | 67 (36–91) | 66 (36–107) | 65 (40–97) | 74 (45–113) | 0.006 | CD |

| Co-morbidity, steroid use, calcium and vitamin D suppletion | ||||||

| Depression, % | 12 | 16 | 11 | 11 | 0.70 | - |

| Cardiovascular disease, % | 18 | 27 | 22 | 17 | 0.42 | - |

| Diabetes, % | 10 | 15 | 11 | 13 | 0.63 | - |

| Oral steroid use, % | 9 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 0.001 | AD |

| Calcium suppletion, % | 27 | 24 | 29 | 32 | 0.35 | - |

| Vitamin D suppletion, % | 9 | 7 | 13 | 15 | 0.10 | - |

| Lung function and smoking | ||||||

| FEV1, %predicted¶ | 65 (19) | 97 (19) | 101 (18) | 104 (18) | <0.001 | AB, AC, AD, BD, CD |

| FEV1, L | 1.24 (0.38) | 1.66 (0.33) | 1.87 (0.38) | 1.95 (0.36) | <0.001 | AB, AC, AD, BC, BD, CD |

| FEV1/FVC, ratio | 58 (7) | 75 (6) | 76 (5) | 77 (5) | <0.001 | AB, AC, AD, BD, CD |

| Pack years, no* | 20 (0–51) | 29 (19–50) | 15 (5–38) | 0 (0) | <0.001 | AB, AD, BC, BD, CD |

| Systemic inflammatory markers | ||||||

| Interleukin 6, pg/ml* | 1.90 (1.31–2.86) | 1.92 (1.33–2.83) | 1.71 (1.17–2.53) | 1.63 (1.12–2.46) | 0.021 | BC |

| C-reactive protein, μg/ml* | 2.09 (1.07–3.72) | 2.00 (1.17–3.95) | 2.18 (1.27–3.83) | 1.63 (0.95–3.07) | <0.001 | CD |

| TNF-α, pg/ml* | 2.92 (2.17–3.75) | 3.06 (2.19–3.95) | 3.02 (2.37–3.86) | 3.10 (2.30–3.97) | 0.63 | - |

Data are mean (SD) unless specified otherwise, significant p-values are boldface.

Median (IQR),

Corrected for multiple testing,

From reference equations [21].

FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; SPPB, Short Physical Performance Battery.

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

This study was supported by National Institute on Aging contracts N01-AG-6-2101, N01-AG-6-2103, and N01-AG-6-2106, and National Heart Lung and Blood Institute grant R01-HL-74104. This research was supported (in part) by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Institute on Aging. This study was performed within the framework of the Dutch Top Institute Pharma project T1-201, The Netherlands.

References

- 1.Gooneratne NS, Patel NP, Corcoran A. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease diagnosis and management in older adults. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010;58:1153–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Celli BR, MacNee W. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004 Jun;23(6):932–46. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00014304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chatila WM, Thomashow BM, Minai OA, Criner GJ, Make BJ. Comorbidities in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2008 May 1;5(4):549–55. doi: 10.1513/pats.200709-148ET. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gan WQ, Man SF, Senthilselvan A, Sin DD. Association between chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and systemic inflammation: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Thorax. 2004 Jul;59(7):574–80. doi: 10.1136/thx.2003.019588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wouters EF, Reynaert NL, Dentener MA, Vernooy JH. Systemic and local inflammation in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: is there a connection? Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society. 2009 Dec;6(8):638–47. doi: 10.1513/pats.200907-073DP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vestbo J, Prescott E, Almdal T, Dahl M, Nordestgaard BG, Andersen T, Sorensen TI, Lange P. Body mass, fat-free body mass, and prognosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease from a random population sample: findings from the Copenhagen City Heart Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006 Jan 1;173(1):79–83. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200506-969OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eisner MD, Iribarren C, Yelin EH, Sidney S, Katz PP, Ackerson L, Lathon P, Tolstykh I, Omachi T, Byl N, Blanc PD. Pulmonary function and the risk of functional limitation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. American journal of epidemiology. 2008 May 1;167(9):1090–101. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gosker HR, Zeegers MP, Wouters EF, Schols AM. Muscle fibre type shifting in the vastus lateralis of patients with COPD is associated with disease severity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2007 Nov;62(11):944–9. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.078980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Graat-Verboom L, Wouters EF, Smeenk FW, van den Borne BE, Lunde R, Spruit MA. Current status of research on osteoporosis in COPD: a systematic review. Eur Respir J. 2009 Jul;34(1):209–18. doi: 10.1183/09031936.50130408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yende S, Waterer GW, Tolley EA, Newman AB, Bauer DC, Taaffe DR, Jensen R, Crapo R, Rubin S, Nevitt M, Simonsick EM, Satterfield S, Harris T, Kritchevsky SB. Inflammatory markers are associated with ventilatory limitation and muscle dysfunction in obstructive lung disease in well functioning elderly subjects. Thorax. 2006 Jan;61(1):10–6. doi: 10.1136/thx.2004.034181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scanlon PD, Connett JE, Wise RA, Tashkin DP, Madhok T, Skeans M, Carpenter PC, Bailey WC, Buist AS, Eichenhorn M, Kanner RE, Weinmann G. Loss of bone density with inhaled triamcinolone in Lung Health Study II. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 2004 Dec 15;170(12):1302–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200310-1349OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oga T, Nishimura K, Tsukino M, Sato S, Hajiro T, Mishima M. Exercise capacity deterioration in patients with COPD: longitudinal evaluation over 5 years. Chest. 2005 Jul;128(1):62–9. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oga T, Nishimura K, Tsukino M, Sato S, Hajiro T, Mishima M. Longitudinal deteriorations in patient reported outcomes in patients with COPD. Respiratory medicine. 2007 Jan;101(1):146–53. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Habraken JM, van der Wal WM, Ter Riet G, Weersink EJ, Toben F, Bindels PJ. Health-related quality of life and functional status in end-stage COPD: longitudinal study. Eur Respir J. 2010 Jun 7; doi: 10.1183/09031936.00149309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Koster A, Visser M, Simonsick EM, Yu B, Allison DB, Newman AB, van Eijk JT, Schwartz AV, Satterfield S, Harris TB. Association between fitness and changes in body composition and muscle strength. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010 Feb;58(2):219–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02681.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fulop T, Larbi A, Witkowski JM, McElhaney J, Loeb M, Mitnitski A, Pawelec G. Aging, frailty and age-related diseases. Biogerontology. 2010 Jun 18; doi: 10.1007/s10522-010-9287-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Montes de Oca M, Loeb E, Torres SH, De Sanctis J, Hernandez N, Talamo C. Peripheral muscle alterations in non-COPD smokers. Chest. 2008 Jan;133(1):13–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wust RC, Morse CI, de Haan A, Rittweger J, Jones DA, Degens H. Skeletal muscle properties and fatigue resistance in relation to smoking history. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2008 Sep;104(1):103–10. doi: 10.1007/s00421-008-0792-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tanni SE, Pelegrino NR, Angeleli AY, Correa C, Godoy I. Smoking status and tumor necrosis factor-alpha mediated systemic inflammation in COPD patients. Journal of inflammation (London, England) 2010;7:29. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-7-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levitzky YS, Guo CY, Rong J, Larson MG, Walter RE, Keaney JF, Jr, Sutherland PA, Vasan A, Lipinska I, Evans JC, Benjamin EJ. Relation of smoking status to a panel of inflammatory markers: the framingham offspring. Atherosclerosis. 2008 Nov;201(1):217–24. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.12.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hankinson JL, Odencrantz JR, Fedan KB. Spirometric reference values from a sample of the general U.S. population. American journal of respiratory and critical care medicine. 1999 Jan;159(1):179–87. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.159.1.9712108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehrotra N, Freire AX, Bauer DC, Harris TB, Newman AB, Kritchevsky SB, Meibohm B. Predictors of mortality in elderly subjects with obstructive airway disease: the PILE score. Annals of epidemiology. 2010 Mar;20(3):223–32. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guralnik JM, Simonsick EM, Ferrucci L, Glynn RJ, Berkman LF, Blazer DG, Scher PA, Wallace RB. A short physical performance battery assessing lower extremity function: association with self-reported disability and prediction of mortality and nursing home admission. J Gerontol. 1994;49(2):M85–94. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.2.m85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guralnik JM, Ferrucci L, Simonsick EM, Salive ME, Wallace RB. Lower-extremity function in persons over the age of 70 years as a predictor of subsequent disability. The New England journal of medicine. 1995 Mar 2;332(9):556–61. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503023320902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Koster A, Stenholm S, Alley DE, Kim LJ, Simonsick EM, Kanaya AM, Visser M, Houston DK, Nicklas BJ, Tylavsky FA, Satterfield S, Goodpaster BH, Ferrucci L, Harris TB. Body Fat Distribution and Inflammation Among Obese Older Adults With and Without Metabolic Syndrome. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md. 2010 Apr 15; doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koster A, Patel KV, Visser M, van Eijk JT, Kanaya AM, de Rekeneire N, Newman AB, Tylavsky FA, Kritchevsky SB, Harris TB. Joint effects of adiposity and physical activity on incident mobility limitation in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008 Apr;56(4):636–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, O’Brien WL, Bassett DR, Jr, Schmitz KH, Emplaincourt PO, Jacobs DR, Jr, Leon AS. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2000 Sep;32(9 Suppl):S498–504. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghosh P, Tu W. Assessing Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors of Young Women: A Joint Model with Nonlinear Time Effects, Time Varying Covariates, and Dropouts. Journal of the American Statistical Association. 2008 Dec 1;103(484):1496–507. doi: 10.1198/016214508000000850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schols AM, Broekhuizen R, Weling-Scheepers CA, Wouters EF. Body composition and mortality in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005 Jul;82(1):53–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Melzer D, Lan TY, Guralnik JM. The predictive validity for mortality of the index of mobility-related limitation--results from the EPESE study. Age and ageing. 2003 Nov;32(6):619–25. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afg107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Castillo EM, Goodman-Gruen D, Kritz-Silverstein D, Morton DJ, Wingard DL, Barrett-Connor E. Sarcopenia in elderly men and women: the Rancho Bernardo study. American journal of preventive medicine. 2003 Oct;25(3):226–31. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(03)00197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Langen RC, Schols AM, Kelders MC, van der Velden JL, Wouters EF, Janssen-Heininger YM. Muscle wasting and impaired muscle regeneration in a murine model of chronic pulmonary inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2006 Dec;35(6):689–96. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0103OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLean RR. Proinflammatory cytokines and osteoporosis. Current osteoporosis reports. 2009 Dec;7(4):134–9. doi: 10.1007/s11914-009-0023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Filozof C, Fernandez Pinilla MC, Fernandez-Cruz A. Smoking cessation and weight gain. Obes Rev. 2004 May;5(2):95–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2004.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cropsey KL, McClure LA, Jackson DO, Villalobos GC, Weaver MF, Stitzer ML. The Impact of Quitting Smoking on Weight Among Women Prisoners Participating in a Smoking Cessation Intervention. American journal of public health. 2010 Jun 17; doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.172783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schols AM, Slangen J, Volovics L, Wouters EF. Weight loss is a reversible factor in the prognosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998 Jun;157(6 Pt 1):1791–7. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.6.9705017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lamprecht B, McBurnie MA, Vollmer WM, Gudmundsson G, Welte T, Nizankowska-Mogilnicka E, Studnicka M, Bateman E, Anto JM, Burney P, Mannino DM, Buist SA. COPD in Never Smokers: Results From the Population-Based Burden of Obstructive Lung Disease Study. Chest. 2011 Apr;139(4):752–63. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-1253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.