Abstract

PKCδ is essential for apoptosis, but regulation of the proapoptotic function of this ubiquitous kinase is not well understood. Nuclear translocation of PKCδ is necessary and sufficient to induce apoptosis and is mediated via a C-terminal bipartite nuclear localization sequence. However, PKCδ is found predominantly in the cytoplasm of non-apoptotic cells, and the apoptotic signal that activates its nuclear translocation is not known. We show that in salivary epithelial cells, phosphorylation at specific tyrosine residues in the N-terminal regulatory domain directs PKCδ to the nucleus where it induces apoptosis. Analysis of each tyrosine residue in PKCδ by site-directed mutagenesis identified two residues, Y64 and Y155, as essential for nuclear translocation. Suppression of apoptosis correlated with suppressed nuclear localization of the Y->F mutant proteins. Moreover, a phosphomimetic PKCδ Y64D/Y155D mutant accumulated in the nucleus in the absence of an apoptotic signal. Forced nuclear accumulation of PKCδ-Y64F and Y155F mutant proteins, by attachment of an SV40 nuclear localization sequence, fully reconstituted their ability to induce apoptosis, indicating that tyrosine phosphorylation per se is not required for apoptosis, but for targeting PKCδ to the nucleus. We propose that phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of PKCδ in the regulatory domain functions as a switch to promote cell survival or cell death.

Keywords: Protein kinase C, tyrosine phosphorylation, apoptosis, nuclear localization, salivary gland

INTRODUCTION

The link between subcellular localization and coordinate activation of specific signaling pathways is an emerging theme in signal transduction. It is clear that the spatial organization of PKCδ within a cell is dependent upon both the cell type and the stimulus type (Collazos, Diouf et al. 2006). Previous work from our laboratory and others has defined PKCδ as a critical regulator of the mitochondrial-dependent apoptotic pathway in vitro and in vivo (Majumder, Pandey et al. 2000; Humphries, Limesand et al. 2006). We have shown that PKCδ transiently accumulates in the nucleus in response to etoposide, and that translocation of PKCδ to the nucleus is required for caspase cleavage and generation of the pro-apoptotic PKCδ catalytic fragment (δCF) (DeVries-Seimon, Ohm et al. 2007). Etoposide induced nuclear translocation of PKCδ requires a C-terminal, Nuclear Localization Sequence (NLS), and mutation of this sequence suppresses nuclear accumulation of PKCδ as well as apoptosis (DeVries, Neville et al. 2002).

While the structural features required for nuclear import of PKCδ have been defined, it remains unclear what triggers nuclear import of PKCδ in the apical stages of apoptosis. Phosphorylation on tyrosine residues is an established mechanism that regulates enzyme activation, assembly of protein complexes, and protein-protein interactions in cells. PKCδ is rapidly phosphorylated on tyrosine residues in response to a wide range of stimuli including agents that induce apoptosis (Steinberg 2004). In some cases, specific tyrosine residues in PKCδ that are important for apoptosis have been identified by mutagenesis (Konishi, Yamauchi et al. 2001; Blass, Kronfeld et al. 2002); however, the mechanism(s) by which phosphorylation of these tyrosines regulates apoptosis has not been identified. In the current studies we show that etoposide induces rapid tyrosine phosphorylation in the regulatory domain of PKCδ, and that phosphorylation at PKCδ residues Y64 and Y155 is necessary for the subsequent nuclear accumulation of PKCδ. As nuclear accumulation of PKCδ is both necessary and sufficient to induce apoptosis (DeVries, Neville et al. 2002), phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of PKCδ on specific tyrosine residues functions as a regulatory switch to promote cell survival or cell death.

RESULTS

PKCδ tyrosine phosphorylation

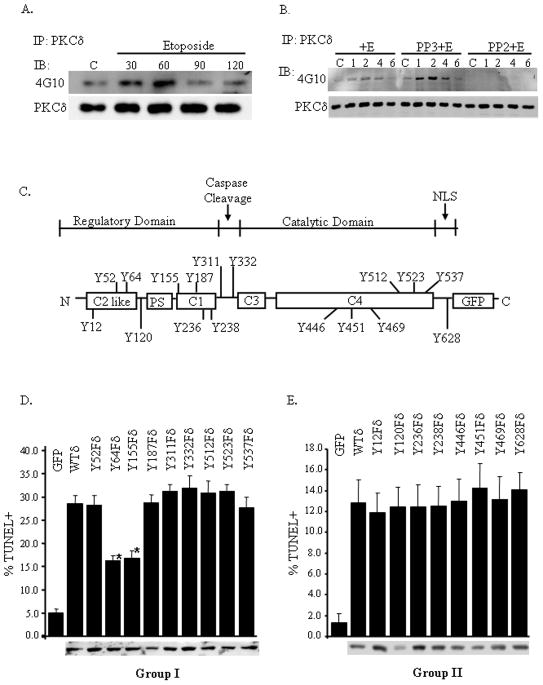

To determine if PKCδ is tyrosine phosphorylated in apoptotic cells, endogenous PKCδ was immunoprecipitated from etoposide treated parC5 cells and then subjected to immunoblotting with a pan phospho-tyrosine antibody (4G10). As shown in Figure 1A, etoposide induced an increase in tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ above that seen in untreated parC5 cells. In the experiment shown here, tyrosine phosphorylation increased within 30 minutes, was maximal at 60 minutes, and declined to the level seen in untreated cells after 90 minutes. However in some experiments tyrosine phosphorylation appeared to be slightly more prolonged (see Figure 1B). Src-like tyrosine kinase family members, as well as the DNA damage responsive tyrosine kinase c-Abl, phosphorylate PKCδ in response to apoptotic agents (Yuan, Utsugisawa et al. 1998; Yoshida, Miki et al. 2002). In Figure 1B we show that pretreatment with PP2, a dual-specific src-like kinase and c-Abl inhibitor, results in a complete block of both basal and etoposide induced PKCδ tyrosine phosphorylation in etoposide treated parC5 cells, while PP3, the inactive form of PP2, has no effect (Tatton, Morley et al. 2003). These results indicate that an etoposide activated tyrosine kinase(s) mediates rapid but transient tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ. The kinetics of tyrosine phosphorylation seems to follow the kinetics previously described for nuclear accumulation of PKCδ in etoposide treated cells, suggesting that tyrosine phosphorylation may be the apical event that commits PKCδ to the apoptotic pathway (DeVries-Seimon, Ohm et al. 2007).

Figure 1. Etoposide induces tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ.

Panel A: ParC5 cells were left untreated (control, C) or treated with 100μM etoposide for the indicated number of minutes. Endogenous PKCδ was immunoprecipitated with an antibody that recognizes an epitope in the N-terminus of PKCδ, and immunoblots were probed with the anti-pan phosphotyrosine antibody, 4G10. Immunoblots were stripped and reprobed with a PKCδ antibody as indicated. Panel B: As in panel A, except that parC5 cells were left untreated (C) or pretreated with either PP2 or PP3 and then challenged with 100μM etoposide for the indicated number of hours. Panel C: Schematic of the approximate position of the Group I (depicted above) and Group II (depicted below) tyrosine residues within PKCδ that were mutated to phenylalanine; the position of the caspase cleavage site and the nuclear localization sequence (NLS) are also depicted. Panels D and E: ParC5 cells were transfected with pGFP, pWTδ, Group I pY→Fδ mutants (panel D) or Group II pY→Fδ mutants (panel E) for 48 hours. Cells were then fixed, and apoptosis was assayed by TUNEL. Shown below is an immunoblot of transfected cell lysates probed with a GFP antibody to determine relative expression of the GFP-PKCδ proteins. In both panels, apoptosis was determined as the percentage of GFP positive cells that were also TUNEL positive. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference (Students T-test; p<0.05) from WTδ. Each experiment was repeated 3 or more times; a representative experiment is shown.

Identification of PKCδ tyrosine residues required for apoptosis

To understand the functional implications of PKCδ tyrosine phosphorylation to apoptosis, we analyzed a panel of GFP-PKCδ proteins each of which contained a point mutation in one of the 19 tyrosine residues present in the murine PKCδ sequence (Fig. 1C). Tyrosine residues 52, 64, 155, 187, 311, 332, 512, 523, and 537 were selected based on evidence from the literature that phosphorylation at these sites is important for specific functions of PKCδ; for the sake of our studies these are classified as Group I; the remaining tyrosine residues are classified as Group II residues (tyrosines 12, 120, 236, 238, 446, 451, 469, and 628). We were able to analyze 17 of the 19 tyrosine residues present in the murine protein by this approach; mutation of the remaining two tyrosines (Y372 and Y565) resulted in generation of unstable proteins. The Y→Fδ mutants exhibited in vitro kinase activity similar to the wild type enzyme, with the exception of Y523Fδ, which had no kinase activity, and Y64Fδ which had slightly reduced kinase activity. Analysis of phosphorylation on PKCδ priming sites, threonine 505 and serine 643, revealed that both sites were similarly phosphorylated in WTδ and all of the Y→Fδ mutants analyzed (data not shown).

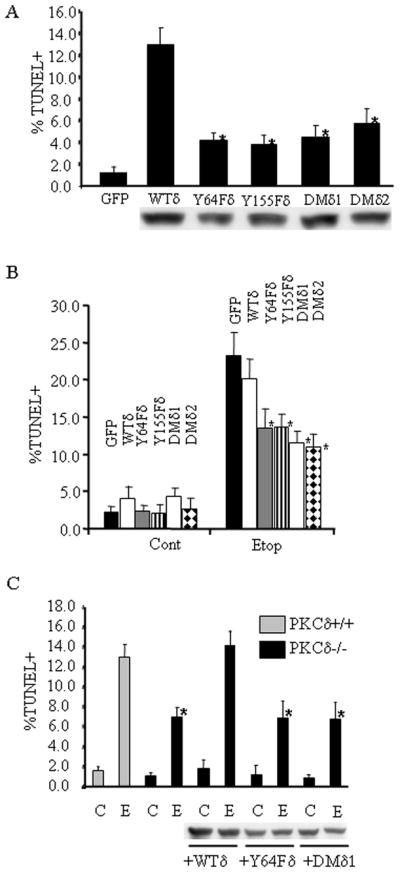

Previous work in our laboratory has shown that overexpression of PKCδ in parC5 cells is sufficient to induce apoptosis, thus we utilized this assay to screen for Y→Fδ mutant proteins that have an enhanced or abrogated ability to induce apoptosis compared to wild type PKCδ (WTδ) (Matassa, Carpenter et al. 2001). WTδ and Y→Fδ mutant proteins were expressed in parC5 cells for 48 hours, and apoptosis was analyzed by TdT (terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase) mediated dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) (Figs. 1D and 1E). The majority of Y→Fδ mutant proteins induced apoptosis to a similar extent as that seen in cells expressing WTδ (Fig. 1D and 1E). However, PKCδ-Y64F (Y64Fδ) and PKCδ-Y155F (Y155Fδ) were significantly attenuated in their ability to induce apoptosis. We next generated a double mutant in which PKCδ was mutated to phenylalanine at both Y64 and Y155 (DMδ). Two independent clones of this mutant (DMδ1 and DMδ2) were used for the following studies. As seen in Figure 2A, expression of either DMδ suppressed apoptosis similar to the Y64Fδ and Y155Fδ single mutants, suggesting that there are no additive or synergistic affect on apoptosis when PKCδ is mutated at both residues.

Figure 2. Tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ at Y64 and Y155 is required for apoptosis.

Panel A: ParC5 cells were transfected with pGFP, pWTδ, pY64Fδ, pY155Fδ, pDMδ1 or pDMδ2 apoptosis was assayed by TUNEL 48 hours following transfection. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference from WTδ (Students T-test; p<0.05). Shown below is an immunoblot of transfected cell lysates probed with a GFP antibody to determine relative expression of the GFP-PKCδ proteins. Panel B: ParC5 cells were transfected as in panel A for18 hours and then treated with 50μM etoposide for an additional 8 hours. TUNEL was assayed as previously described. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference from etoposide treated WTδ (Students T-test; p<0.05). Panel C: Primary parotid salivary cells were isolated from PKCδ+/+ and PKCδ−/− mice and cultured as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were left untransduced or transduced with Ad-WTδ, Ad-Y64Fδ, or Ad-DMδ as indicated. Cells were then challenged with or without 200μM etoposide for an additional 20 hours, and TUNEL assay was conducted. Expression of the GFP-PKCδ proteins was assayed by immunoblot using a GFP antibody. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference (Students T-test; p<0.05) from etoposide treated PKCδ+/+ cells. For all panels, apoptosis is expressed as the percentage of GFP positive (panels A, B, and C) or only DAPI stained (first four bars of panel C) cells that were also TUNEL positive. Each experiment was repeated 3 or more times; a representative experiment is shown.

To determine if Y64Fδ or Y155Fδ can function as dominant negative proteins to suppress etoposide-induced apoptosis, we transfected parC5 cells with pGFP, pWTδ, pY64Fδ, pY155Fδ or pDMδ and challenged these cells with etoposide (Fig. 2B). Expression of Y64Fδ or Y155Fδ suppressed apoptosis compared to cells expressing GFP or WTδ, suggesting that Y64Fδ and Y155Fδ can suppress the pro-apoptotic function of endogenous PKCδ in parC5 cells. However, suppression of apoptosis under these conditions is only partial, perhaps due to the fact that the PKCδ tyrosine mutants must compete with endogenous PKCδ. To address this, we utilized primary cultures of parotid salivary cells derived from PKCδ−/− mice. Primary parotid cells were isolated from PKCδ+/+ or PKCδ−/− mice and transduced with AdGFP-PKCδ (Ad-WTδ), AdGFP-PKCδ-Y64F (Ad-Y64Fδ), or AdGFP-PKCδ-DM (Ad-DMδ), treated with etoposide, and apoptosis was assayed by TUNEL. As we have previously shown, and as seen here in Fig. 2C, PKCδ−/− cells are defective in apoptosis induced by etoposide. However expression of PKCδ can fully reconstitute the apoptotic response, while expression of Ad-Y64Fδ or Ad-DMδ does not result in an increase in apoptosis over that observed in PKCδ−/− cells (Humphries, Limesand et al. 2006). These data demonstrate that tyrosine residues at positions Y64 and Y155 are critical for PKCδ induced apoptosis, and suggest that phosphorylation at these residues specifies a pro-apoptotic function for PKCδ. However the fact that apoptosis is only partially suppressed even the absence of endogenous PKCδ, indicate the presence of parallel pathways(s) that also participate in apoptotic signaling.

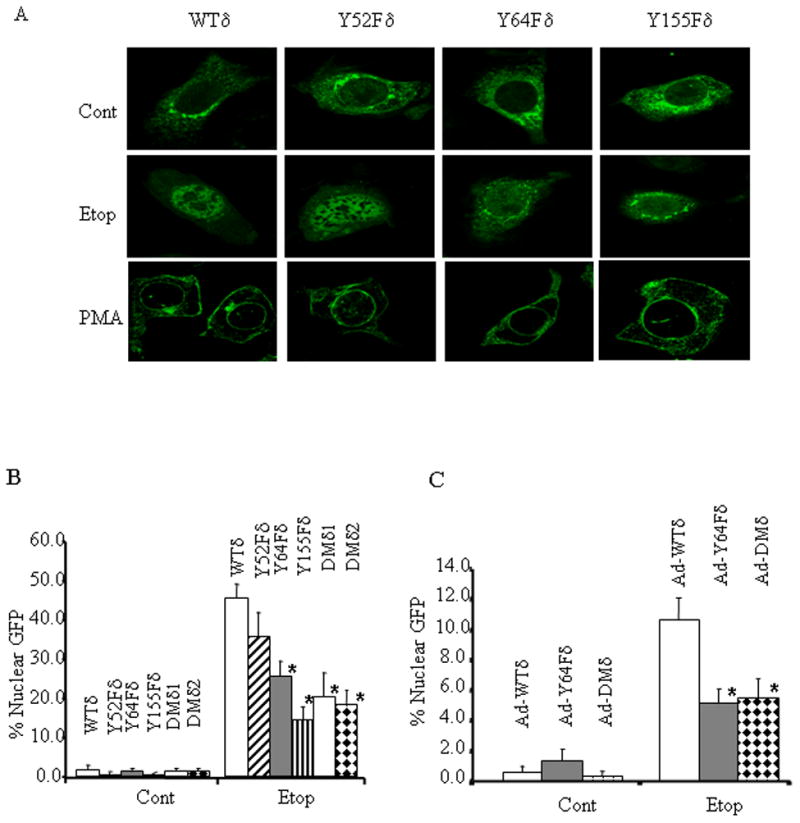

Phosphorylation at Y64 and Y155 regulates nuclear localization of PKCδ

Since nuclear accumulation of PKCδ is required for apoptosis; we asked whether tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ is necessary for nuclear localization of PKCδ. ParC5 cells were transfected with pWTδ, pY52Fδ, pY64Fδ, or pY155Fδ, challenged with etoposide, and analyzed for nuclear localization of the GFP tagged proteins. Fluorescent microscopy to detect the GFP tag showed perinuclear and cytoplasmic localization for WTδ and Y52Fδ, Y64Fδ and Y155Fδ mutants in resting cells (Fig. 3A, top panel). Upon treatment with etoposide, WTδ and Y52Fδ translocated to the nucleus, while Y64Fδ and Y155Fδ remained predominantly perinuclear and cytoplasmic (Fig. 3A, middle panel). As shown in Fig. 3B, treatment with etoposide induced translocation of WTδ and the Y52δ mutant in 46% and 36% of cells respectively, while nuclear localization of Y64Fδ and Y155Fδ was observed in 25% and 14% of cells respectively. Similar suppression of nuclear localization was observed in cells which transfected with two independent clones of pDMδ (Fig. 3B). Etoposide-induced nuclear localization of the Y64Fδ or DMδ proteins was also suppressed in PKCδ−/− cells (Fig. 3C). In contrast, treatment with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) induced translocation of WTδ, Y52Fδ, Y64Fδ and Y155Fδ to the nuclear envelope and the plasma membrane, indicating that tyrosine phosphorylation at these residues is not required for the association of PKCδ with cellular membranes (Fig. 3A, lower panel). In fact, all 17/19 tyrosine mutants screened showed normal plasma membrane association in response to PMA (data not shown). These results suggest that tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ controls nuclear localization through a mechanism distinct from those known to be involved in plasma membrane association.

Figure 3. Tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ at Y64 and Y155 regulates nuclear translocation.

Panel A: ParC5 cells were transfected with pWTδ, pY52Fδ, pY64Fδ or pY155Fδ as described in Materials and Methods. Eighteen hours after transfection cells were treated left untreated, treated with 50μM etoposide for 8 hours, or treated with 500nM PMA for 10 minutes. Cells were then fixed and GFP fluorescence was analyzed with confocal microscopy. Each experiment was repeated 3 or more times; a representative experiment is shown. Panel B: ParC5 cells were transfected with pWTδ, pY52Fδ, pY64Fδ, pY155Fδ, pDMδ1, or pDMδ2 for 18 hours and then left untreated or treated with 50μM etoposide for an additional 8 hours. Cells were fixed and nuclear localization of GFP-PKCδ proteins was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Panel C: Primary parotid cells were isolated from PKCδ−/− mice and cultured as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were transduced with Ad-WTδ, Ad-Y64Fδ, or Ad-DMδ as indicated. Cells were then left untreated or treated with 200μM etoposide for an additional 20 hours and nuclear localization of GFP-PKCδ proteins was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. For Panels B and C, asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference (Students T-test; p<0.05) from cells transfected with pWTδ (Panel B) or transduced (Panel C) with Ad-WTδ.

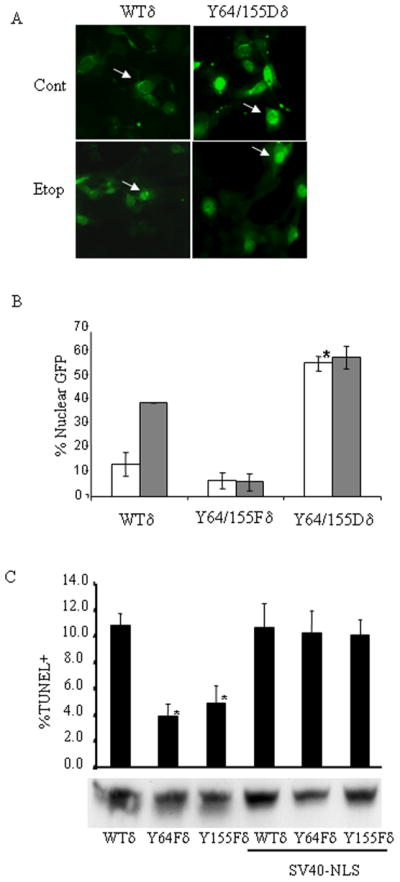

To determine if tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ is sufficient to target PKCδ to the nucleus we mutated Y64 and Y155 to aspartic acid which mimics the negative charge imparted by phosphorylation. ParC5 cells were transfected with pWTδ, pY64F/Y155Fδ (DMδ1) or pY64D/Y155Dδ and analyzed for nuclear localization of the GFP tagged proteins by fluorescent microscopy. As shown in Figure 4A and 4B, expression of the Y64D/Y155Dδ mutant results in nuclear targeting of the GFP tagged protein in >50% of transfected cells in the absence of apoptotic stimuli; no further increase in nuclear targeting was observed with the addition of etoposide. This suggests that addition of a negative charge alone at these sites is sufficient to allow nuclear accumulation of PKCδ, and that phosphorylation of PKCδ at Y64 and Y155 regulates apoptosis by controlling nuclear translocation of PKCδ.

Figure 4. A Y->D phosphomimetic of PKCδ at Y64/Y155 localizes to the nucleus.

Panels A and B: ParC5 cells were transfected with pWTδ, pDMδ1 (Y64F/Y155Fδ) or pY64D/Y155Dδ for 18 hours and then left untreated (white bars) or treated with 50μM etoposide (gray bars) for an additional 6 hours. Cells were fixed and nuclear localization of GFP-PKCδ proteins was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy (Panel A). The results are quantified in panel B; asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference between untreated cells expressing WTδ and Y64D/Y155Dδ (Students T-test; p<0.05). Each experiment was repeated 3 or more times; a representative experiment is shown. Panel C: ParC5 cells were transfected with pWTδ, pY64Fδ, pY155Fδ, pWTδ-SV40, pY64Fδ-SV40, or pY155Fδ-SV40 vectors for 48 hours and apoptosis was assayed by TUNEL. Expression of the GFP-PKCδ proteins was assayed by immunoblot using an anti-GFP antibody. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference from WTδ (Students T-test; p<0.05). Each experiment was repeated 3 or more times; a representative experiment is shown.

Targeting Y64Fδ and Y155Fδ mutants to the nucleus is sufficient to induce apoptosis

If tyrosine phosphorylation at Y64 and Y155 function only to localize PKCδ to the nucleus, we reasoned that nuclear targeting of these mutant proteins by fusion of an SV40 nuclear localization sequence (SV40-NLS) to the N-terminus may now allow them to induce apoptosis. These constructs were made in the context of a caspase cleavage mutation (CM) since caspase cleavage of these proteins would result in loss of the SV40-NLS. ParC5 cells transfected with pPKCδCM-SV40 (WTδ-SV40), pPKCδCM-Y64F-SV40 (Y64Fδ-SV40) or pPKCδCM-Y155F-SV40 (Y155Fδ-SV40) exhibited exclusive nuclear localization (data not shown). As previously observed, apoptosis was suppressed in cells expressing the Y64Fδ and Y155Fδ mutants compared to WTδ (Fig. 4C). However, targeting Y64Fδ-SV40 and Y155Fδ-SV40 to the nucleus caused induction of apoptosis similar to their control counterpart, WTδ-SV40, and also similar to WTδ (Figure 4C). These results show that forcing Y64Fδ and Y155Fδ into the nucleus restores these mutants’ ability to induce apoptosis and confirms that suppression of nuclear localization accounts for the inability of these mutants to induce apoptosis.

DISCUSSION

PKCδ is a key intermediate in the transduction of diverse apoptotic signals; however, the molecular signals that activate the pro-apoptotic role of this multi-functional kinase are not well understood. Our laboratory and others have shown that nuclear accumulation of PKCδ is both necessary and sufficient for apoptosis in response to genotoxins, suggesting that subcellular localization is important for specifying differential functions of this kinase (DeVries, Neville et al. 2002). In previous studies we have shown that PKCδ accumulates rapidly, but transiently, in the nucleus in response to etoposide (DeVries-Seimon, Ohm et al. 2007). Here we show that tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ occurs with similar kinetics and is the signal that activates pro-apoptotic signaling of PKCδ by inducing nuclear translocation. Our studies define Y64 and Y155 as critical residues for pro-apoptotic signaling by PKCδ and suggest that phosphorylation of PKCδ at these residues regulates nuclear translocation and hence cell survival.

We analyzed of 17 of the 19 tyrosine residues in the murine PKCδ protein and identify Y64 and Y155 as critical to the pro-apoptotic function of PKCδ. Interestingly, none of the Y->F tyrosine mutants analyzed increased apoptosis in our PKCδ overexpression assay, suggesting that tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ does not suppress the pro-apoptotic function of PKCδ in parC5 cells. This is in line with other studies in which activation of tyrosine kinases and tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ has generally been associated with the promotion of apoptosis (Kajimoto, Ohmori et al. 2001; Konishi, Yamauchi et al. 2001; Blass, Kronfeld et al. 2002). A notable exception is Glioma cells in which Brodie and colleagues have shown that tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ can either suppress or promote apoptosis in a stimulus specific manner. Our findings parallel those of Blass et al who show that mutation of PKCδ Y64 inhibits etoposide induced apoptosis in glioma cells, however these studies also identified Y187 as critical for the apoptotic response to etoposide, while mutation of Y187 to phenylalanine had no affect on apoptosis either in our overexpression system or in etoposide treated parC5 cells (data not shown) (Blass, Kronfeld et al. 2002). Our studies also indicate a role for Y155 in nuclear translocation and apoptosis, while, mutation of PKCδ Y155 enhanced Sindbis virus (Zrachia, Dobroslav et al. 2002) and TRAIL (Okhrimenko, Lu et al. 2005) induced apoptosis in glioma cells, suggesting a protective role for this residue. Differences between the Blass et al report and our current data regarding the role of specific tyrosine residues in PKCδ may reflect cell specific pathways in glioma versus salivary epithelial cells. In this regard, expression of a PKCδ Y155 mutant in NIH-3T3 cells induced a higher growth rate and neoplastic characteristics, consistent with the loss of a tumor suppressing, proapoptotic function (Acs, Beheshti et al. 2000).

Expression of PKCδ mutated at both Y64 and Y155 does not result in additive or synergistic apoptotic defects beyond those seen with the single mutations, suggesting that phosphorylation at these two sites act in concert to regulate apoptosis. One possibility is that once tyrosine phosphorylated, PKCδ binds with low affinity to a protein containing dual SH2 domains, and that phosphorylation at both Y64 and Y155 is required for this interaction. Alternatively, phosphorylation of PKCδ at one of these sites may be required for binding and activation of the tyrosine kinase responsible for phosphorylation of PKCδ at the second site. The latter scenario may explain the observation that in addition to the ability of tyrosine kinases to bind to and activate PKCδ, under some circumstances these kinases may be activated by PKCδ as well (Song, Swann et al. 1998; Sun, Wu et al. 2000).

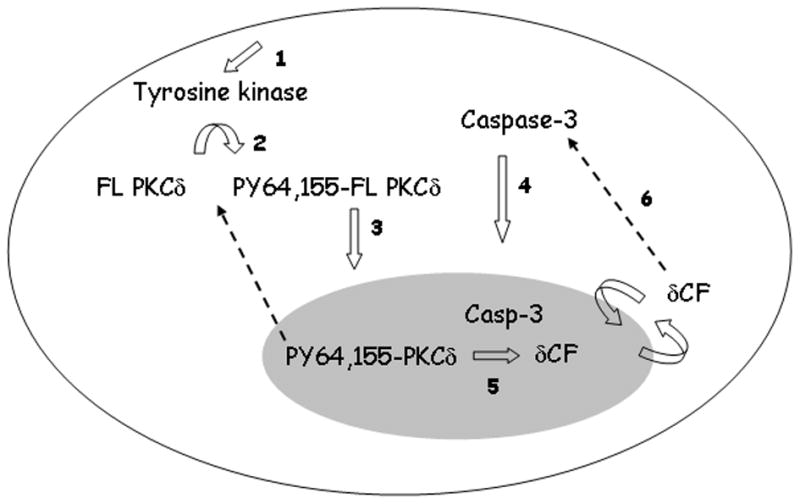

Our findings suggest that the N-terminal regulatory domain of PKCδ constrains NLS dependent import of PKCδ into the nucleus in the absence of an apoptotic signal. Phosphorylation of PKCδ at Y64 and Y155 in this domain, or removal of the regulatory domain by caspase cleavage, are necessary to enable nuclear accumulation of PKCδ. These findings have important implications for our understanding of how the pro-apoptotic function of PKCδ is regulated. As depicted in Figure 5, we predict that activation of a tyrosine kinase(s) downstream of genotoxic damage (step 1) results in phosphorylation of PKCδ on tyrosine (step 2), allowing its nuclear import (step 3). Nuclear localization of endogenous PKCδ is transient, possibly due to dephosphorylation of the critical tyrosine sites (DeVries-Seimon, Ohm et al. 2007). The fact that the PKCδ catalytic fragment lacks the regulatory domain may explain why the catalytic fragment localizes to, and is retained in, the nucleus independent of an apoptotic stimulus (DeVries, Neville et al. 2002). Our results suggest that prior to tyrosine phosphorylation at Y64 and Y155, PKCδ may be held in a conformation in which the NLS is shielded and unable to interact with molecules required for PKCδ nuclear import. As we have previously shown, once in the nucleus PKCδ is cleaved by nuclear capsase-3 to generate the pro-apoptotic δCF (steps 4 and 5) (DeVries-Seimon, Ohm et al. 2007). Since δCF is sufficient to activate caspase-3, its presence in the cytoplasm of apoptotic cells may result in amplification of the apoptotic pathway (step 6) (DeVries, Neville et al. 2002). Taken together, our studies suggest the tyrosine phosphorylation of PKCδ may integrate diverse cell damage signals prior to caspase activation, and thus serve as a switch between cell survival and cell death.

Figure 5. Activation of the pro-apoptotic function of PKCδ in response to genotoxic damage.

(1) Genotoxins such as etoposide activate tyrosine kinase(s) resulting in phosphorylation of PKCδ at Y64 and Y155 (2). (3) PKCδ phosphorylated in the regulatory domain accumulates transiently in the nucleus of apoptotic cells, followed by the nuclear translocation of activated caspase -3 (4). (5) Caspase cleavage of PKCδ occurs in the nucleus generating the constitutively active, proapoptotic, δCF. A predicted amplification loop whereby δCF results in activation of caspase-3 in the cytoplasm is shown in (6). See text for details.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, preparation of primary salivary cells, and reagents

The parC5 cell line was cultured as previously described (Anderson, Reyland et al. 1999). ParC5 cells were transfected using Fugene 6 Transfection Reagent (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, IN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Primary mouse parotid cells were prepared from 5–7 week old PKCδ−/− mice and PKCδ+/+ littermates as previously described (Limesand, Barzen et al. 2003; Humphries, Limesand et al. 2006). Cells grew to approximately 80% confluency in 5 days and were used at that time for experiments without further passage. PKCδ−/− mice were a generous gift of Dr. Keiichi Nakayama (Kyushu University, Fukuoka, Japan) and maintained in accordance with University of Colorado Denver at Health Sciences Center Laboratory Animal Care guidelines and protocols (Miyamoto, Nakayama et al. 2002). Etoposide and PMA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). The src-like kinase inhibitor PP2, and the inactive control, PP3, were purchased from Calbiochem and dissolved in DMSO. All tissue culture reagents were purchased from Biosource (Rockville, MD, USA) and Mediatech Incorporated Cellgro (Herndon, VA, USA).

Plasmids and construction of GFP-PKCδ mutants

Unless stated otherwise, all PKCδ constructs were constructed in pEGFP-N1 and encode fusion proteins with GFP attached to the C-terminus of PKCδ (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA, USA). Generation of the constructs pPKCδWT and pPKCδCM has been previously described (DeVries, Neville et al. 2002). To make the Y->Fδ and Y->Dδ mutants, tyrosine residues were converted to phenylalanine or aspartic acid in the context of the wild type PKCδ fusion protein GFP-PKCδ (WTδ) using the mouse PKCδ cDNA and the Quick Change Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA, USA) per the manufacturer’s instructions. The primers used for Y->F site directed mutagenesis are provided in Tables 1 and 2 (Supplementary data). pPKCδ-Y64F/Y155F (DMδ) was generated using pPKCδ-Y64F as a template and the primers described in Table 1 for pPKCδ-Y155F. The pPKCδ-Y64D/Y155Dδ phosphomimetic was generated in two steps. First, pY64Dδ was generated from WTδ using the primers : 5′-CAACGTTCGACGCCCACATCGATGAAGGCCGTGTTAT-3′ and 5′-ATAACACGGCCTTCATCGATGTGGGCGTCGAACGTTG-3′. Second, pY64/Y155Dδ was generated using Y64Dδ as a template and the primers : 5′-CAGGCCAAGATCCACGACATCAAGAACCACGAGTTTATCGCC-3′ and 5′-GGCGATAAACTCGTGGTTCTTGATGTCGTGGATCTTGGCCTG-3′.

An SV40-NLS (amino acid sequence TPPKKKRKVEDPE) was fused to the N-terminus of various GFP-PKCδ fusion proteins to target these proteins to the nucleus (Tolcher, Reyno et al. 2002). The pPKCδCM construct, which contains a mutated caspase cleavage site, was used as a template for site-directed mutagenesis at residues Y64 and Y155 to create pPKCδCM-Y64F and pPKCδCM-Y155F. This was done to ensure that activated caspases could not cleave these constructs, thus removing the N-terminal SV40-NLS. The SV40-NLS was fused to the N-terminus of these constructs by PCR using the primers: 5′-GCCTCGAGATGACACCCCCCAAGAAGA AGCGAAAGGTAGAAGATCCCGAAGCACCCTTCCTTCGC-3′ containing an Xho1 site and 5′-GCTCTAGAGTCGCGGCCG CTTTACTTGT-3′ containing an Xba1 site. Xho1 and Xba1 double restriction digests were inserted into the pEGFP-N1 vector creating the products pPKCδCM-SV40, pPKCδCM-Y64F-SV40, and pPKCδCM-Y155F-SV40. All mutations were confirmed by DNA sequence analysis.

Adenovirus construction and expression in primary salivary cells

The GFP adenovirus has been previously described (Schaack, Allen et al. 2001). Xho1 and Xba1 double restriction digestion fragments of pPKCδWT, pPKCδ-Y64F, and pPKCδDM were subcloned into the adenoviral shuttle vector, pXCMV, and recombinant adenoviruses were prepared as described (Graham and Prevec 1995). Adenoviruses were titered in HEK293 cells based on GFP expression. Primary parotid cells were transduced with the indicated viruses at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) (focus forming units/cell) of 500 in serum-free Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) for one hour with occasional shaking. After one hour of transduction, the medium was aspirated and replaced with normal medium.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblot analysis

Cells were harvested and immunoblots were performed as previously described (Anderson, Reyland et al. 1999). For immunoprecipitation assays, 500μg of whole cell lysate protein was incubated overnight at 4°C with either a monoclonal PKCδ antibody (610398, Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) or polyclonal GFP antiserum (ab290, Abcam, Cambridge, UK). The rabbit polyclonal antibody PKCδ (sc-213) was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Mouse monoclonal antibodies that recognize pan-phosphotyrosine (4G10 (05-321, 1:750 dilution)) or GFP (33-2600, 1:500 dilution), were purchased from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY, USA) and Zymed (San Fransisco, CA, USA), respectively. Super Signal West Pico Luminol/Enhancer Solution (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) was used for detection of the proteins.

TUNEL analysis and cell counts

TUNEL was performed using In Situ Cell Death Detection TMR Red (Roche Molecular Biochemicals) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For some experiments, cells were transfected or virally transduced with the indicated pPKCδ plasmid or adenovirus and stained with 5μg/ml 4′,6-Diamidino-2-Phenylindole Dihydrochloride Hydrate (DAPI) (Sigma-Aldrich) to visualize the nucleus. Transfected and transduced cells expressing the GFP fusion proteins were visualized with immunofluorescent microscopy and counted using a 40X objective. For cells not expressing GFP-PKCδ proteins, TUNEL positive (TMR Red fluor) cells exhibiting chromatin condensation were scored as apoptotic. For cells expressing GFP-PKCδ proteins; GFP positive, TUNEL positive (TMR Red fluor) cells exhibiting chromatin condensation were scored as apoptotic. Greater than 400 cells were counted for each variable per experiment.

Fluorescent microscopy

Cells on coverslips were transfected or transduced with pPKCδ plasmids or adenoviruses followed by fixation in 2% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes. Cells were rinsed with PBS once and stained with 5μg/ml DAPI for an additional 30 minutes, followed by three 15 minute washes in PBS. Cells were analyzed for the subcellular localization of GFP-PKCδ proteins by fluorescent microscopy. For assessment of nuclear localization, cells were quantified as the total number of GFP expressing cells per field that had predominantly nuclear localized GFP. Greater than 300 cells were counted for each variable per experiment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The technical assistance of Melissa Miller and Jonathon Schneider is gratefully acknowledged. We thank Drs. Steve Anderson and Peter Parker for helpful discussions over the course of this work. These studies were supported by Grant# R01 DE015648-01 (MER) and POI HD038129 (MER and JS).

References

- Acs P, Beheshti M, Szallasi Z, Li L, Yuspa SH, Blumberg PM. Effect of a tyrosine 155 to phenylalanine mutation of protein kinase Cdelta on the proliferative and tumorigenic properties of NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:887–891. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.5.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson S, Reyland M, Hunter S, Deisher L, Barzen K, Quissell D. Etoposide-induced activation of c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) correlates with drug-induced apoptosis in salivary gland acinar cells. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:454–462. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blass M, Kronfeld I, Kazimirsky G, Blumberg P, Brodie C. Tyrosine phosphorylation of protein kinase C delta is essential for its apoptotic effect in response to etoposide. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:182–195. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.1.182-195.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collazos A, Diouf B, Guerineau NC, Quittau-Prevostel C, Peter M, Coudane F, et al. A spatiotemporally coordinated cascade of protein kinase C activation controls isoform-Selective Translocation. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2247–2261. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2247-2261.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries TA, Neville MC, Reyland ME. Nuclear import of PKC delta is required for apoptosis: identification of a novel nuclear import sequence. EMBO J. 2002;21:6050–6060. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVries-Seimon TA, Ohm AM, Humphries MJ, Reyland ME. Induction of apoptosis is driven by nuclear retention of PKCdelta. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22307–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703661200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham FL, Prevec L. Methods for construction of adenovirus vectors. Mol Biotech. 1995;3:207–220. doi: 10.1007/BF02789331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humphries MJ, Limesand KH, Schneider JC, Nakayama KI, Anderson SM, Reyland ME. Suppression of apoptosis in the protein kinase Cdelta null mouse in Vivo. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:9728–9737. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507851200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kajimoto T, Ohmori S, Shirai Y, Sakai N, Saito N. Subtype-specific translocation of the delta subtype of protein kinase C and its activation by tyrosine phosphorylation induced by ceramide in HeLa cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1769–1783. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.5.1769-1783.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi H, Yamauchi E, Taniguchi H, Yamamoto T, Matsuzaki H, Takemura Y, et al. Phosphorylation sites of protein kinase C delta in H2O2 treated cells and its activation by tyrosine kinase in vitro. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:6587–6592. doi: 10.1073/pnas.111158798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limesand KH, Barzen KA, Quissell DO, Anderson SM. Synergistic suppression of apoptosis in salivary acinar cells by IGF1 and EGF. Cell Death Differ. 2003;10:345–355. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majumder PK, Pandey P, Sun X, Cheng K, Datta R, Saxena S, et al. Mitochondrial translocation of protein kinase C delta in phorbol ester-induced cytochrome c release and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21793–21796. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000048200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matassa A, Carpenter L, Biden T, Humphries M, Reyland M. PKC delta is required for mitochondrial dependent apoptosis in salivary epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29719–29728. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100273200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto A, Nakayama K, Imaki H, Hirose S, Jiang Y, Abe M, et al. Increased proliferation of B cells and auto-immunity in mice lacking protein kinase C delta. Nature. 2002;416:865–869. doi: 10.1038/416865a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okhrimenko H, Lu W, Xiang C, Ju D, Blumberg PM, Gomel R, et al. Roles of tyrosine phosphorylation and cleavage of protein kinase Cdelta in its protective effect against tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis inducing ligand-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23643–23652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501374200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaack J, Allen B, Orlicky DJ, Bennett ML, Maxwell IH, Smith RL. Promoter strength in adenovirus transducing vectors: down-regulation of the adenovirus E1A promoter in 293 cells facilitates vector construction. Virology. 2001;291:101–109. doi: 10.1006/viro.2001.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JS, Swann PG, Szallasi Z, Blank U, Blumberg PM, Rivera J. Tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent and -independent associations of protein kinase C delta with src family kinases in the RBL-2H3 mast cell line: regulation of src family kinase activity by protein kinase C. Oncogene. 1998;16:3357–3368. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg S. Distinctive activation mechanisms and functions for protein kinase C delta. Biochem J. 2004;384:449–459. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X, Wu F, Datta R, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. Interaction between Protein Kinase C delta and the c-Abl Tyrosine Kinase in the Cellular Response to Oxidative Stress. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7470–7473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatton L, Morley G, Chopra R, Khwaja A. The src-selective kinase inhibitor PP1 Also inhibits Kit and Bcr-Abl tyrosine kinases. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:4847–4853. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209321200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolcher AW, Reyno L, Venner PM, Ernst SD, Moore M, Geary RS, et al. A randomized phase II and pharmacokinetic study of the antisense oligonucleotides ISIS 3521 and ISIS 5132 in patients with pormone-refractory prostate pancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2530–2535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida K, Miki Y, Kufe D. Activation of SAPK/JNK signaling by Protein Kinase C delta in response to DNA damage. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48372–48378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205485200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Z-M, Utsugisawa T, Ishiko T, Nakada S, Huang Y, Kharbanda S, et al. Activation of protein kinase C delta by the c-Abl tyrosine kinase in response to ionizing radiation. Oncogene. 1998;16:1643–1648. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1201698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zrachia A, Dobroslav M, Blass M, Kazimirsky G, Kronfeld I, Blumberg P, et al. Infection of glioma cells with Sindbis virus induces selective activation and tyrosine phosphorylation of protein kinase C delta. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:23693–23701. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111658200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.