Abstract

The non-virulent Wolbachia strain wMel and the life-shortening strain wMelPop-CLA, both originally from Drosophila melanogaster, have been stably introduced into the mosquito vector of dengue fever, Aedes aegypti. Each of these Wolbachia strains interferes with viral pathogenicity and/or dissemination in both their natural Drosophila host and in their new mosquito host, and it has been suggested that this virus interference may be due to host immune priming by Wolbachia. In order to identify aspects of the mosquito immune response that might underpin virus interference, we used whole-genome microarrays to analyse the transcriptional response of A. aegypti to the wMel and wMelPop-CLA Wolbachia strains. While wMel affected the transcription of far fewer host genes than wMelPop-CLA, both strains activated the expression of some immune genes including anti-microbial peptides, Toll pathway genes and genes involved in melanization. Because the induction of these immune genes might be associated with the very recent introduction of Wolbachia into the mosquito, we also examined the same Wolbachia strains in their original host D. melanogaster. First we demonstrated that when dengue viruses were injected into D. melanogaster, virus accumulation was significantly reduced in the presence of Wolbachia, just as in A. aegypti. Second, when we carried out transcriptional analyses of the same immune genes up-regulated in the new heterologous mosquito host in response to Wolbachia we found no over-expression of these genes in D. melanogaster, infected with either wMel or wMelPop. These results reinforce the idea that the fundamental mechanism involved in viral interference in Drosophila and Aedes is not dependent on the up-regulation of the immune effectors examined, although it cannot be excluded that immune priming in the heterologous mosquito host might enhance the virus interference trait.

Author Summary

Wolbachia pipientis is an inherited intracellular bacterium that is widespread in insects. Because of its ability to interfere with various pathogens such as dengue viruses, nematodes and Plasmodium in insects, it has been proposed as a possible tool to control insect-transmitted disease. Recently, two strains of Wolbachia that interfere with RNA viruses in their natural host, Drosophila melanogaster, were introduced into the naturally uninfected mosquito vector of dengue fever, Aedes aegypti. As in their natural host, those two strains block the replication and the dissemination of viruses in the mosquito. Some studies suggest that pathogen blocking is due to Wolbachia priming the insect innate immune system. Here, we show that Wolbachia induces transcription of some immunity related genes only in its new host A. aegypti, and not in its natural host D. melanogaster, while Wolbachia reduces dengue replication in both hosts. These results suggest that immune priming by Wolbachia might not be the only mechanism responsible for viral interference.

Introduction

Wolbachia is a vertically transmitted endosymbiont that infects up to 70% of all insect species. The association is usually not obligatory for the insect and many Wolbachia strains assure their maintenance in populations by manipulating the reproduction of their host [1]. Interestingly, some strains interfere only weakly with host reproduction but still spread and are maintained in insect populations [2]. Their success may be explained by an additional positive selective advantage associated with Wolbachia infection. One possible advantage is the recently described pathogen blocking that the bacterium confers upon its host. This phenotype was first demonstrated in Drosophila, where Wolbachia induces resistance to different types of RNA viruses by reducing viral titer and/or making the host resistant to virus pathogenicity [3]–[5]. The extent and nature of blocking vary according to the virus and the Wolbachia strains tested. For example, Wolbachia reduces the titer of the closely related DCV and Nora viruses in Drosophila melanogaster and D. simulans [4], [5] and as a consequence, the pathology associated with those two viruses is less intense in Wolbachia-infected flies [3]–[5]. In contrast, the bacterium does not affect FHV titer in Drosophila but still reduces the pathogenicity of the virus [3]–[5]. In D. simulans, the wAu Wolbachia strain has a strong effect against DCV pathogenicity, whereas the strains wHa and wNo do not [5]. This observation is thought to be related to the low infection density of wHa and wNo in Drosophila compared to that of the wAu strain [5].

Wolbachia does not naturally infect the main mosquito vector of dengue viruses, Aedes aegypti. However, two Wolbachia strains originally isolated from D. melanogaster (wMelPop-CLA and wMel) and one strain originally from A. albopictus (wAlbB) have been successfully trans-infected into A. aegypti and subsequently stably maintained [6]–[8]. All of these strains express cytoplasmic incompatibility in A. aegypti as they do in their original hosts, D. melanogaster and A. albopictus [6]–[8]. In addition, the virulent wMelPop-CLA strain that lacks normal replication control and reduces lifespan in D. melanogaster also does so in A. aegypti [7]. As observed in Drosophila, Wolbachia-infected A. aegypti are more resistant to RNA virus infection, including dengue and chikungunya [8], [9], as well as bacteria, nematodes and Plasmodium [9], [10]. Transient somatic infection of the main African vector of human malaria, Anopheles gambiae, by wMelPop also significantly decreased Plasmodium infection intensity [11].

The molecular mechanisms involved in Wolbachia-mediated pathogen protection are still not clear. One plausible hypothesis is that Wolbachia interferes with pathogens by pre-activating the immune response of its host. The virulent strain wMelPop-CLA activates a wide range of immune processes in A. aegypti, including the Toll and Imd signaling pathways, anti-microbial peptide synthesis, melanization, RNA interference and opsonisation [9], [10] and the somatic infection of An. gambiae by wMelPop caused an increase in expression of opsonisation genes [11]. Evidence for the role of opsonisation in protection against Plasmodium in this host was demonstrated by knocking down expression of the TEP1 gene [11]. Transcriptional analyses of A. aegypti immunity genes showed that wAlbB increases expression of genes in the Toll pathway and in particular the anti-microbial peptide gene, defensin [12]. Activation of the Toll pathway has been shown previously to suppress dengue infection in mosquitoes [13]. Each of these previous studies was limited in that they examined Wolbachia strains that were either virulent and/or recently introduced into naturally uninfected host species. To our knowledge, only two previous studies have examined expression of innate immune genes in insect species naturally infected by Wolbachia, including D. simulans, D. melanogaster and A. albopictus. In these cases no differences in gene regulation were observed between Wolbachia-infected insects and their uninfected counterparts [14], [15].

Since all previous studies that have shown evidence of immune activation have been based on recently established heterologous infections, it is unclear how generalizable the Wolbachia activation of the mosquito immune system is for all insects. To determine whether immune up-regulation by the bacterium is a general mechanism underlying Wolbachia-induced dengue interference, we performed transcriptional analyses on the two heterologous associations, wMel and wMelPop-CLA infected A. aegypti, and the two native associations, wMel and wMelPop infected D. melanogaster. We also tested if the non-virulent strain wMel blocks dengue replication in Drosophila as it does in mosquitoes. If the same strain of Wolbachia blocks the replication of the same virus in different hosts, we can make the parsimonious assumption that virus interference is likely to have a common mechanistic basis across different hosts. This cross-comparison with the two Wolbachia strains and dengue virus in both native and heterologous hosts allows us to remove extraneous effects, such as recent transfer to a heterologous host or virulence associated with the wMelPop infection, that might confound an understanding of the underlying mechanistic basis of Wolbachia-induced viral interference.

This study also contributes to our understanding of the physiological impact of wMel infection on A. aegypti. This is of particular relevance because wMel-infected A. aegypti have been released in north Queensland, Australia, in a field trial using Wolbachia as a biocontrol mechanism for dengue [16]. In the near future, this biological tool is also likely to be applied in dengue-endemic areas of Vietnam and Indonesia [17].

Results

Transcriptional response of Aedes aegypti to Wolbachia infection

We examined the global transcriptional response of mosquitoes to Wolbachia infection using microarrays. We compared the responses of 8 day old, non blood-fed A. aegypti females stably transinfected with wMelPop-CLA (line PGYP1) or wMel (line MGYP2) to those of the corresponding tetracycline-cured lines PGYP1.tet and MGYP2.tet. The design of the microarray included 12,336 transcripts, which represented 12,270 of the 15,988 genes present in the A. aegypti genome. We considered a gene to be up- or down-regulated by wMelPop-CLA or wMel infection if the fold change in transcription relative to non-infected mosquitoes was significantly different from 1.0 and greater than 1.5. Because the Drosophila genome is better characterized, we identified Drosophila orthologs of each A. aegypti gene where possible to obtain additional functional annotations.

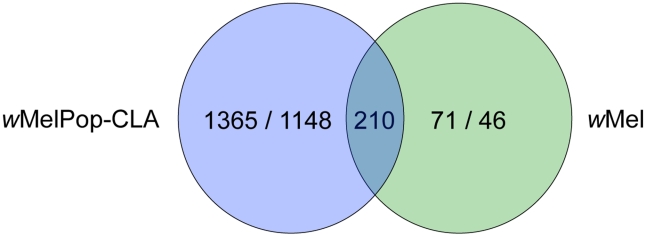

The wMelPop-CLA infection affected the transcription of far more genes (2723) than the wMel infection (327) (Figure 1). This is likely related to wMelPop-CLA's higher density in its host, broader cellular tropism and pathogenicity [8], [9], [18]. Based on Gene Ontology (GO) annotations, wMelPop-CLA has an impact on a broader range of A. aegypti biological and molecular functions than wMel (Table 1, 2).

Figure 1. Venn diagram showing significant expression change in response to infection in A. aegypti infected with wMelPop-CLA or wMel.

The overlap region corresponds to A. aegypti gene transcripts significantly up- and down-regulated in response to both strains. Numbers indicate gene transcripts up-regulated/gene transcripts down-regulated.

Table 1. Gene Ontology (GO) terms over-represented among gene transcripts significantly up-regulated in wMel-infected A. aegypti.

| GO ID | Term description | Adjusted P-values |

| Biological process | ||

| GO:0009607 | Response to biotic stimulus | 2.16E-05 |

| GO:0006508 | Proteolysis | 1.05E-04 |

| GO:0051704 | Multi-organism process | 2.33E-04 |

| GO:0019538 | Protein metabolic process | 1.09E-02 |

| GO:0006952 | Defense response | 1.27E-02 |

| Molecular function | ||

| GO:0017171 | Serine hydrolase activity | 2.16E-05 |

| GO:0008233 | Peptidase activity | 2.81E-03 |

| GO:0004175 | Endopeptidase activity | 6.40E-03 |

| GO:0003824 | Catalytic activity | 6.89E-03 |

| GO:0005529 | Iron ion binding | 2.53E-02 |

| GO:0016787 | Hydrolase activity | 3.65E-02 |

| Cellular component | ||

| GO:0005576 | Extracellular region | 4.85E-04 |

Adjusted P-values are the P-values generated by the Ontologizer program [38], using the Benjamini-Hochberg method.

Table 2. Gene Ontology (GO) terms over-represented among gene transcripts significantly up-regulated in wMelPop-CLA-infected A. aegypti.

| GO ID | Term description | Adjusted P-values |

| Biological process | ||

| GO:0006508 | Proteolysis | 5.87E-15 |

| GO:0009308 | Amine metabolic process | 9.22E-08 |

| GO:005114 | Oxidation reduction | 4.97E-07 |

| GO:0005975 | Carbohydrate metabolic process | 7.41E-05 |

| GO:0009607 | Response to biotic stimulus | 2.16E-04 |

| GO:0055085 | Transmembrane transport | 8.08E-04 |

| GO:0044271 | Cellular nitrogen compound biosynthetic process | 2.72E-03 |

| GO:0006952 | Defense response | 3.19E-03 |

| GO:0022610 | Biological adhesion | 3.82E-03 |

| GO:0051704 | Multi-organism process | 7.77E-03 |

| GO:0051604 | Protein maturation | 9.19E-03 |

| GO:0019538 | Protein metabolic process | 1.18E-02 |

| GO:0002376 | Immune system process | 1.87E-02 |

| GO:0043565 | Chemical homeostasis | 2.27E-02 |

| GO:0051179 | Localization | 3.08E-02 |

| GO:0071554 | Cell wall organization or biogenesis | 3.50E-02 |

| GO:0044283 | Small molecule biosynthetic process | 4.96E-02 |

| GO:0010876 | Lipid localization | 5.00E-02 |

| Molecular function | ||

| GO:0005506 | Iron ion binding | 3.98E-16 |

| GO:0003824 | Catalytic activity | 6.62E-10 |

| GO:0046906 | Tetrapyrrole binding | 1.31E-09 |

| GO:0005215 | Transporter activity | 1.27E-06 |

| GO:0030246 | Carbohydrate binding | 4.29E-06 |

| GO:0009055 | Electron carrier activity | 6.98E-06 |

| GO:0004857 | Enzyme inhibitor activity | 3.31E-05 |

| GO:00164901 | Oxidoreductase activity | 4.12E-05 |

| GO:0008233 | Peptidase activity | 7.56E-05 |

| GO:0017171 | Serine hydrolase activity | 1.08E-04 |

| GO:0061134 | Peptidase regulator activity | 2.23E-04 |

| GO:0005509 | Calcium ion binding | 3.99E-04 |

| GO:0005102 | Receptor binding | 3.82E-03 |

| GO:0005044 | Scavenger receptor activity | 4.70E-03 |

| GO:0005515 | Protein binding | 5.05E-03 |

| GO:0004047 | Aminomethyltransferase activity | 1.08E-02 |

| GO:0043565 | Sequence-specific DNA binding | 1.64E-02 |

| Cellular component | ||

| GO:0016020 | Membrane | 5.79E-16 |

| GO:0005576 | Extracellular region | 4.32E-09 |

| GO:0043234 | Protein complex | 4.62E-03 |

| GO:0005856 | Cytoskeleton | 7.77E-03 |

Adjusted P-values are the P-values generated by the Ontologizer program [38], using the Benjamini-Hochberg method.

Many of the changes in gene regulation observed in mosquitoes infected with the virulent strain wMelPop-CLA are likely to be responses to the high physiological cost imposed by that strain. To identify mechanisms more likely to be involved in pathogen interference, we decided to focus on the 210 gene transcripts that showed significant changes in expression in both PGYP1 and MGYP2 compared to uninfected mosquitoes (Figure 1). Among those genes, 138 gene transcripts had functional annotations (Table S1).

Most of the 210 transcripts were either up-regulated in both PGYP1 and MGYP2 or down-regulated in both lines (Table S1). However, the magnitude of response was typically greater to wMelPop-CLA infection (Table S1). One of the few genes differentially expressed between PGYP1 and MGYP2 is AAEL002487, which is up-regulated in MGYP2 and down-regulated in PGYP1. This gene encodes the protein P53 regulated pa26 nuclear protein sestrin (dSesn in Drosophila) (Table S1). This protein is involved in the regulation of the target of rapamycin (TOR), a key protein in age-related pathologies like life-shortening or muscle degeneration [19], two phenotypes exclusively associated with wMelPop-CLA pathogenicity in A. aegypti [7], [20]. Among the 210 genes, most of the genes showing the greatest up-regulation are immune genes (Table S1). Gene Ontology (GO) annotations also revealed enrichment in genes related to immunity and proteolysis for MGYP2 and PGYP1 (Table 1, 2). The results obtained for PGYP1 are in accordance with a previous study of A. aegypti infected by wMelPop-CLA [10].

Common immune pathways activated by wMelPop-CLA and wMel in A. aegypti

The virulent strain wMelPop-CLA significantly affected regulation of many characterized immune genes in the mosquito (Table S2, [10]). By comparison, many fewer of these genes were activated by wMel (Table 3, S1, S3). Those included genes encoding anti-microbial peptides, four cecropins (CECE, CECF, CECN, CECD), one defensin (DEFC) and one diptericin (DPT1). The magnitude of change in expression was substantial for some of these genes. The activation of these peptides is regulated by both Toll and Imd pathways, but we found up-regulation only of some Toll pathway genes, including the peptidoglycan recognition protein PGRP-SA and the Gram-negative binding proteins GNBPB4 and GNBPA1 (GNBP1 Drosophila homologs, Table 3). The Toll pathway effector defensin was the most highly up-regulated immune gene in A. aegypti infected by wMel (Table 3). This is consistent with the results of Bian et al [12], who examined immune gene expression in heterologous wAlbB infection in A. aegypti and found that among the immune genes tested defensin was also the most up-regulated.

Table 3. A. aegypti putative immune transcripts significantly up-regulated in response to both wMelPop-CLA and wMel infections.

| wMelPop-CLA | wMel | ||||||

| Transcripts ID | AFC | q-value | AFC | q-value | Description | Dm Gene ID H | Dm Symbol |

| Anti-microbial peptides | |||||||

| AAEL000598-RA | 10.44 | 1.83E-04 | 2.93 | 4.00E-03 | cecropin (CECD) | no homolog | |

| AAEL000611-RA | 125.52 | 9.63E-06 | 12.62 | 6.41E-03 | cecropin (CECE) | no homolog | |

| AAEL000625-RA | 53.83 | 3.65E-05 | 6.07 | 9.84E-03 | cecropin (CECF) | no homolog | |

| AAEL000621-RA | 47.31 | 1.14E-05 | 10.11 | 4.10E-03 | cecropin (CECN) | no homolog | |

| AAEL003832-RA | 70.76 | 7.09E-06 | 22.99 | 2.89E-03 | defensin-C (DEFC) | FBgn0010385 | Def |

| AAEL004833-RA | 2.72 | 6.72E-05 | 1.53 | 5.46E-03 | diptericin 1 (DPT1) | no homolog | |

| Toll pathway | |||||||

| AAEL007993-RA | 9.33 | 7.09E-06 | 1.90 | 4.81E-03 | clip-domain serine protease (CLIPB27) | FBgn0039494 | grass |

| AAEL007626-RA | 3.04 | 2.68E-05 | 1.67 | 9.05E-03 | gram-negative binding protein (GNBPA1) | FBgn0040323 | GNBP1 |

| AAEL009178-RA | 3.72 | 8.98E-04 | 7.50 | 6.19E-03 | gram-negative binding protein (GNBPB4) | FBgn0040323 | GNBP1 |

| AAEL011624-RA | 2.55 | 4.84E-04 | 2.00 | 7.53E-03 | granzyme A precursor | FBgn0003450 | snk |

| AAEL009474-RA | 6.76 | 5.10E-05 | 2.96 | 5.69E-03 | peptidoglycan recognition protein (PGRPS1) | FBgn0030310 | PGRP-SA |

| AAEL010867-RA | 4.27 | 1.15E-04 | 1.76 | 4.59E-03 | serine protease | FBgn0003450 | snk |

| Melanization | |||||||

| AAEL000024-RA | 2.18 | 1.72E-04 | 1.54 | 9.33E-03 | dopachrome-conversion enzyme (DCE) | FBgn0041710 | yellow-f |

| AAEL013501-RA | 32.84 | 2.53E-05 | 2.71 | 4.81E-03 | pro-phenoloxidase (PPO4) | FBgn0000165 | |

| AAEL003642-RA | 8.29 | 7.09E-06 | 3.46 | 1.91E-03 | serine protease | FBgn0037515 | Sp7 |

| AAEL013936-RA | 1.65 | 6.22E-04 | 1.56 | 3.52E-03 | serine protease inhibitor (SRPN4) | FBgn0031973 | Spn28D |

| Other putative immune related genes | |||||||

| AAEL005641-RA | 31.47 | 3.97E-05 | 5.27 | 2.68E-03 | C-type lectin - galactose binding (CTLGA5) | no homolog | |

| AAEL011621-RA | 5.84 | 2.50E-04 | 2.35 | 2.89E-03 | C-type lectin - mannose binding (CTLMA13) | no homolog | |

| AAEL011453-RA | 4.15 | 3.79E-05 | 1.89 | 8.54E-03 | C-type lectin (CTL14) | FBgn0053533 | lectin-37Db |

| AAEL011408-RA | 3.06 | 2.16E-05 | 1.99 | 5.26E-04 | C-type lectin (CTL21) | no homolog | |

| AAEL002524-RA | 7.38 | 1.20E-04 | 4.10 | 9.78E-03 | C-type lectin (CTL24) | no homolog | |

| AAEL002601-RA | 7.31 | 6.12E-05 | 2.31 | 2.33E-03 | clip-domain serine protease (CLIPA1) | FBgn0033321 | CG8738 |

| AAEL014349-RA | 6.74 | 7.09E-06 | 2.04 | 3.49E-03 | clip-domain serine protease (CLIPB15) | no homolog | |

| AAEL000059-RA | 2.10 | 4.14E-04 | 1.68 | 8.98E-03 | clip-domain serine protease (CLIPB19) | no homolog | |

| AAEL001084-RA | 16.39 | 7.09E-06 | 4.25 | 3.80E-03 | clip-domain serine protease (CLIPB21) | no homolog | |

| AAEL008668-RA | 4.53 | 6.51E-05 | 2.00 | 7.73E-03 | clip-domain serine protease (CLIPB22) | no homolog | |

| AAEL006674-RA | 1.85 | 2.22E-04 | 1.53 | 4.82E-03 | clip-domain serine protease (CLIPB29) | no homolog | |

| AAEL000099-RA | 4.26 | 2.27E-05 | 2.11 | 2.83E-03 | clip-domain serine protease (CLIPB33) | no homolog | |

| AAEL005431-RA | 22.66 | 1.85E-05 | 3.95 | 2.76E-03 | clip-domain serine protease (CLIPB37) | no homolog | |

| AAEL005093-RA | 11.58 | 3.13E-05 | 3.05 | 5.87E-03 | clip-domain serine protease (CLIPB46) | no homolog | |

| AAEL010773-RA | 3.64 | 4.41E-05 | 2.45 | 1.50E-03 | clip-domain serine protease (CLIPE10) | no homolog | |

| AAEL001098-RA | 5.01 | 6.49E-05 | 2.00 | 7.95E-03 | clip-domain serine protease, putative | no homolog | |

| AAEL009861-RB | 2.20 | 1.37E-04 | 2.06 | 8.98E-03 | conserved hypothetical protein | FBgn0034638 | CG10433 |

| AAEL009861-RD | 2.20 | 6.66E-05 | 2.08 | 7.11E-03 | conserved hypothetical protein | FBgn0034638 | CG10433 |

| AAEL009861-RC | 2.02 | 2.50E-04 | 1.66 | 7.11E-03 | conserved hypothetical protein | FBgn0034638 | CG10433 |

| AAEL008473-RA | 10.52 | 6.16E-03 | 1.91 | 3.35E-05 | cysteine-rich venom protein, putative | FBgn0031412 | CG16995 |

| AAEL000374-RA | 15.30 | 8.75E-03 | 2.15 | 3.10E-05 | cysteine-rich venom protein, putative | no homolog | |

| AAEL012956-RA | 3.81 | 1.11E-04 | 2.39 | 4.68E-03 | elastase, putative | no homolog | |

| AAEL002022-RA | 5.15 | 3.40E-04 | 2.65 | 3.20E-03 | protein serine/threonine kinase, putative | FBgn0011695 | PebIII/phk2 |

| AAEL001964-RA | 4.45 | 6.57E-05 | 1.90 | 4.74E-03 | protein serine/threonine kinase, putative | FBgn0011695 | PebIII/phk2 |

| AAEL002585-RA | 8.05 | 2.19E-05 | 1.66 | 7.61E-03 | serine protease | FBgn0028864 | CG18477 |

| AAEL002624-RA | 6.65 | 3.16E-05 | 1.89 | 2.74E-03 | serine protease | FBgn0028514 | CG4793 |

| AAEL002610-RA | 6.93 | 1.14E-05 | 2.10 | 8.54E-03 | serine protease | FBgn0032638 | CG6639 |

| AAEL002301-RA | 3.85 | 2.75E-05 | 2.18 | 7.63E-03 | serine protease | no homolog | |

| AAEL003697-RA | 3.11 | 3.05E-05 | 1.77 | 6.42E-03 | serine protease inhibitor (SRPN17) | no homolog | |

| AAEL006136-RA | 4.83 | 3.30E-05 | 2.17 | 3.66E-03 | serine protease, putative | FBgn0038211 | CG9649 |

| AAEL006434-RA | 3.53 | 4.42E-05 | 1.80 | 8.62E-03 | serine protease, putative | no homolog | |

| AAEL013033-RA | 3.18 | 1.52E-05 | 2.32 | 5.22E-03 | serine protease, putative | no homolog | |

| AAEL013432-RA | 2.56 | 6.78E-05 | 3.84 | 3.31E-03 | serine protease, putative | no homolog | |

| AAEL004761-RA | 1.89 | 3.12E-04 | 1.67 | 3.93E-03 | serine/threonine-protein kinase MAK | FBgn0051711 | |

| AAEL015458-RA | 55.38 | 7.09E-06 | 12.23 | 1.88E-05 | transferrin | FBgn0022355 | Tsf1 |

Transcripts are ranked by biological process and/or molecular function. Transcript identifiers (Transcript ID) and Description were compiled from Vectorbase. D. melanogaster Gene Identifier Homolog (Dm Gene ID H) and Dm Symbol were compiled from Flybase. AFC, Absolute Fold Change.

Excluding anti-microbial peptides and the Toll pathway, the only other immune response activated by both wMel and wMelPop-CLA in A. aegypti was melanization. Four genes in this pathway were up-regulated: one pro-phenoloxidase (PPO4), one dopachrome-conversion enzyme (DCE) that converts dopachrome into 5,6-dihydroxyindole just before melanin production by phenoloxidase [21], one putative protease inducer sp7 and one protease inhibitor Srpn4 (Table 3). The activation of these genes suggests that production of melanin is induced in Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes.

Effect of Wolbachia on dengue virus in Drosophila

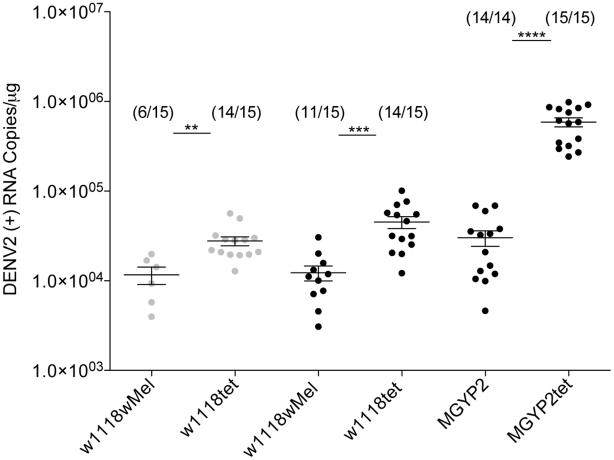

Since a comparative approach between Drosophila and Aedes to examine the effect of immune activation on virus interference is predicated on an assumption that dengue virus interference also occurs in Wolbachia-infected Drosophila, we tested the ability of dengue virus serotype 2 (DENV-2) to grow in Drosophila carrying the wMel Wolbachia strain.

For both dengue virus strains, 92T and ET300, the total number of flies infected by dengue was lower in the presence of wMel, with only 40% of flies detected positive for the 92T strain compared with 93% for the Wolbachia-uninfected control. Similarly for the ET300 strain, 73% of Wolbachia-infected flies were positive for dengue compared to 93% for the Wolbachia-uninfected control (Figure 2). In addition, for the flies that did become infected with dengue the amount of DENV-2 RNA present was significantly reduced in the presence of wMel (Figure 2). It was unsurprising to note that dengue grew to higher levels when injected into its natural mosquito host compared to Drosophila but regardless of absolute virus levels significant Wolbachia interference effects were detected in both insect species. Dengue injection in flies did not have an effect on insect life span nor increased mortality compared to controls (data not shown).

Figure 2. Dengue blocking in D. melanogaster and A. aegypti infected by Wolbachia strain wMel.

69 µl of 107 pfu/ml of DENV2 strain 92T (grey circles) and DENV2 strain ET300 (black circles) were injected into flies (w1118wMel) and mosquitoes (MGYP2) infected by wMel and their tetracycline-treated uninfected counterparts (w1118tet and MGYP2tet). Dengue levels in individual insects were determined 8 days post-infection by RT-PCR using a TaqMan assay specific to dengue in 1 µg of total RNA. The fraction of flies that had detectable dengue infections is shown above each set of data points. (n = 15, Mann-Whitney U test, **: p<0.01, ***:p<0.001, ****:p<0.0001).

Effect of wMelPop and wMel on the Drosophila melanogaster immune system

Considering that the Wolbachia strains wMelPop [22] and wMel in their original host interfere with natural Drosophila RNA viruses and also with dengue virus replication, we then investigated the possibility that both Wolbachia strains boost Drosophila immunity as seen in the heterologous mosquito host. We examined by quantitative real time PCR the expression of the Drosophila homologs of the mosquito immune genes identified through microarray analysis to be up-regulated in the presence of Wolbachia.

There have been multiple gene losses and gene duplications in immune gene families in both flies and mosquitoes [23], and we were therefore unable to reliably identify all orthologs for our anti-microbial peptide genes and pro-phenoloxidase genes of interest. Thus, we targeted all the cecropin, diptericin and pro-phenoloxidase genes present in the genome of D. melanogaster. In total 13 immune genes were analyzed: seven anti-microbial peptide genes, two Toll pathway genes and four melanization genes (Table 4).

Table 4. Immune transcript analyses in D. melanogaster infected with wMelPop and wMel.

| wMelPop | wMel | |||||||

| Gene ID | AFC | q-value | AFC | q-value | Description | Symbol | ||

| Anti-microbial peptides | ||||||||

| FBgn0000276 | 2.24 | 0.030 | * | −1.59 | 0.324 | cecropin A1 | CecA1 | |

| FBgn0000277 | 1.63 | 0.109 | 1.58 | 0.597 | cecropin A2 | CecA2 | ||

| FBgn0000278 | ND | ND | cecropin B | CecB | ||||

| FBgn0000279 | ND | ND | cecropin C | CecC | ||||

| FBgn0004240 | 1.25 | 0.661 | −1.16 | 0.743 | diptericin | Dpt | ||

| FBgn0034407 | 1.37 | 0.661 | −1.13 | 0.743 | diptericin B | DptB | ||

| FBgn0010385 | 1.27 | 0.398 | 1.24 | 0.591 | defensin | Def | ||

| Toll pathway | ||||||||

| FBgn0030310 | −1.49 | 0.030 | * | 1.11 | 0.168 | peptidoglycan recognition protein SA | PGRP-SA | |

| FBgn0040323 | 1.05 | 0.631 | 1.29 | 0.002 | ** | gram-negative binding protein 1 | GNBP1 | |

| Melanization | ||||||||

| FBgn0261363 | −2.6 | 0.008 | ** | −1.69 | 0.142 | CG42640 | ||

| FBgn0261362 | 1.67 | 0.011 | * | −1.47 | 0.030 | * | pro-phenoloxidase A1 | proPO-A1 |

| FBgn0033367 | 1.04 | 0.743 | −1.39 | 0.154 | CG8193 | |||

| FBgn0041710 | 1.08 | 0.631 | −1.01 | 0.661 | yellow-f | yellow-f | ||

| Other | ||||||||

| FBgn0022355 | −2.25 | 0.008 | ** | −1.15 | 0.324 | transferrin 1 | Tsf1 | |

| FBgn0015221 | −1.99 | 0.109 | −1.22 | 0.661 | ferritin 2 light chain homologue | Fer2lch | ||

Transcripts are ranked by biological process and/or molecular function. Gene identifiers (Gene ID), Description and Symbol were compiled from Flybase. AFC, Absolute Fold Change, ND, No Detection. Asterisks indicate a statistically significant difference (n = 10, Mann-Whitney U test with q-value adjustment, *: q<0.05, **: q<0.01).

No significant changes in the expression of anti-microbial peptide genes were observed for w 1118 wMelPop or w 1118 wMel, except for cecropin A1 (Table 4). The expression of cecropin A1 was two-fold higher in the presence of wMelPop, whereas no change was observed in the presence of wMel (Table 4). No gene expression was detected for the cecropins B and C for either of the Drosophila lines tested. No significant changes in diptericin transcription were observed in Wolbachia-infected flies, which suggests that the Imd signaling pathway is not stimulated by Wolbachia in Drosophila. The expression patterns of two major genes in the Toll pathway, PGRP-SA and GNBP1, differed between flies infected by wMel and wMelPop. A slight inhibition of PGRP-SA was observed in flies infected by wMelPop, while in wMel-infected flies there was no effect. For GNBP1, a minor but significant difference, 1.29-fold change, was observed for w1118wMel but not for w1118wMelPop (Table 4). The expression of only a single melanization gene was affected by wMel infection: proPO-A1 was down-regulated. In contrast, in flies infected with wMelPop, proPO-A1 was significantly up-regulated and another melanization gene, CG42640, was down-regulated (Table 4).

An enrichment of gene transcripts encoding the iron binding proteins transferrin and ferritin was detected in the data obtained from the A. aegypti transcriptome analysis in response to wMel and wMelPop-CLA infections (Table 1, 2, S1). These proteins have multiple functions in insects, including iron homeostasis and immunity [24], two potential mechanisms that could be involved in Wolbachia-mediated pathogen protection. The expression of the genes encoding transferrin 1 (Tsf1) and the light chain of ferritin (Fer2lch) was evaluated in w1118wMel and w1118wMelPop compared to w1118tet. However, no induction was found in Wolbachia-infected flies (Table 4) and wMelPop infection even significantly reduced the expression of transferrin.

The expression of immune genes was also tested in the same fly lines (w1118wMel and w1118tet) infected with DENV-2, strain 92T. Even in the presence of dengue, wMel infection did not increase the expression of anti-microbial peptides and pro-phenoloxidases (Figure S1). No correlation was found between the amount of dengue detected and the level of expression for each of the anti-microbial peptide and pro-phenoloxidases genes tested in each fly line (Figure S2).

Discussion

Host immune priming by Wolbachia offers an appealing mechanistic explanation for pathogen blocking as it is conceivable that this single effect could lead to protection against a diversity of pathogens. The objective of this study was to compare the effect of two closely-related strains of Wolbachia on the immune system of hosts where the age of the Wolbachia association differs. By comparing wMelPop-CLA and wMel we could exclude any potential immune activation that may simply be due to the virulence of the wMelPop-CLA infection. By examining both D. melanogaster and A. aegypti, we were able to dissect aspects of the immune response that may be attributed solely to a host's response to a recently acquired Wolbachia infection. This analysis depends on an assumption that the mechanism of virus interference is similar in the two insect hosts. Considering that Wolbachia infection in Drosophila interferes with dengue replication, as it does in A. aegypti, the assumption of a similar mechanism seems parsimonious. Moreover the success of maintaining dengue in Drosophila, even if viral replication is not as strong as in A. aegypti, provides a tractable genetic model for future studies into the mechanistic basis of Wolbachia-mediated dengue interference.

A previous analysis of A. aegypti whole genome transcription in response to wMelPop-CLA revealed strong immune induction by the bacterium [10]. In this present study, a similar approach was taken to analyze the impact of the non-virulent wMel strain on the immune system of A. aegypti, in comparison with the wMelPop-CLA strain. The results obtained revealed that wMel induces the activation of far fewer immunity genes in the mosquito. The comparative analysis between the different lines identified common responses only for genes encoding anti-microbial peptides, the Toll pathway and melanization-associated proteins. Recent studies have provided important insights into A. aegypti immune response to dengue virus, showing that the Toll pathway and anti-microbial peptides are important for the mosquito's defense against dengue infection [13], [25]. Melanization is also a prominent immune response in insects against parasites like malaria and nematodes [26] but as far as we know it has never been demonstrated for dengue.

The main anti-viral pathway, RNA interference [27], seems to be activated exclusively by wMelPop-CLA. Several pieces of evidence also indicate that RNAi cannot explain virus blocking. First, Glaser et al [28] showed that even in Ago2 (a key gene in the RNAi pathway) mutant flies, Wolbachia infection increases resistance to viruses. Second, Frentiu et al [29] demonstrated that wMelPop-CLA induces complete inhibition of dengue virus replication in the C6/36 cell line that has been shown to be defective in the RNAi pathway [30].

This comparative analysis between wMel and wMelPop-CLA infection within A. aegypti supports the potential implication of anti-microbial peptides and Toll pathway activation in dengue virus interference by the bacterium. If we assume that the fundamental mechanism involved in Wolbachia-mediated dengue interference is the same in mosquitoes and flies, and this mechanism is immune-based, then the same constitutive immune induction should also be observed in D. melanogaster infected by wMel or wMelPop. We tested for transcriptional changes of the same immune genes identified through microarray analysis in D. melanogaster in response to Wolbachia infection, and identified a number of statistically significant changes. However, in no case were these changes consistent between wMel and wMelPop infection. Furthermore, if we employed the same threshold for biological significance we used for our microarray data, that a gene is significantly up-regulated by Wolbachia infection only when its level is changed at least 1.5-fold compared with non-infected flies, we would conclude that wMel did not constitutively prime any of the different immune genes tested in its natural host D. melanogaster. Those results are in accordance with previous data showing no pre-activation of different immune genes in D. melanogaster, D. simulans and A. albopictus by Wolbachia [14], [15].

In summary, the only immune genes up-regulated by wMelPop-CLA and wMel in A. aegypti are anti-microbial peptides, Toll pathway and melanization genes. However, the same Wolbachia strains did not up-regulate these genes in Drosophila, and yet dengue interference occurs in this host. This indicates that the up-regulation of these immune effector genes is not required to interfere with dengue virus replication, although it is likely that the immune up-regulation that occurs in mosquitoes, presumably due to the recent association with Wolbachia, might enhance this effect.

Materials and Methods

Insect rearing

All the mosquito strains used in this study were laboratory lines of A. aegypti infected with wMel (MGYP2) or wMelPop-CLA (PGYP1), and their tetracycline-treated uninfected counterparts, MGYP2.tet and PGYP1.tet [7], [8]. Adult mosquitoes were kept on 10% sucrose solution at 25°C and 60% humidity with a 12-h light/dark cycle. Larvae were maintained with fish food pellets (Tetramin, Tetra).

The fly experiments were performed with w1118 fly lines stably infected with wMel (w1118wMel) [31] and wMelPop (w1118wMelPop) [18] compared to the tetracycline-cured lines derived by the addition of tetracycline (0.3 mg/ml) to the adult diet for two generations. Those lines were confirmed to be free of Wolbachia by PCR, using primers specific for the wMel and wMelPop IS5 repeat [22]. Females were kept under controlled conditions, low-density (30 females per vial), at 25°C with 60% relative humidity and a 12-h light/dark cycle.

Sample collection and hybridization

Three replicate pools of 20 female mosquitoes, 8 days post-eclosion were collected from each of the four lines (PGYP1, MGYP2, PGYP1.tet and MGYP2.tet), snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and extracted for total RNA using Trizol (Invitrogen). RNA was then purified using RNeasy kits (Qiagen) according to manufacturer's instructions. Whole-genome microarrays were then used to compare gene expression in the Wolbachia-infected lines relative to uninfected controls, using a dual-color reference design. All sample preparations and hybridizations were then carried out by the IMB Microarray Facility at the University of Queensland. Briefly, sample quality was examined using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies) and fluorescent cDNA was synthesized using Agilent Low RNA Input Linear Amplification Kit with Cy3 or Cy5. Each infected line and respective paired tetracycline-treated line was represented by 3 biological replicates (3 pools above). A total of 6 hybridizations were then carried out for each biological replicate, 3 labeled with cy3 and three with cy5 (dye swaps).

Microarray design

Microarrays were of the 4×44 K format (Agilent) each containing standard control features and 3 technical replicates of each 60 mer feature randomly distributed across the layout. The A. aegypti genomic sequence (Vectorbase genome build 1.1) was used for construction of oligonucleotide microarrays using eArray Version 5.0 (Agilent Technologies). After removing probes that cross hybridized, a total of 12,336 transcripts that represented 12,270 genes were spotted onto each microarray [32].

Microarray data analyses

For each transcript, raw data was extracted and analyzed using Genespring v.9.0 (Agilent Technologies). An intensity dependent (Lowess) normalization (Per Spot and Per Chip) was used to correct for non-linear rates of dye incorporation as well as irregularities in the relative fluorescence intensity between the dyes. Hybridizations from each mosquito line were used as replicate data to test for significance of expression changes using the cross-gene error model. The occurrence of false positives was corrected using the q-value [33], [34]. All array data have been deposited in ArrayExpress (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/microarray-as/ae/) under the accession number E-MEXP-2931.

Functional annotations of A. aegypti genes were retrieved from Biomart [35] in Vectorbase [36] and analyzed using the Ontologizer software with the parent child intersection method [37], [38]. The over-expression of particular GO categories in the microarray data set was tested against the distribution of GO categories for the A. aegypti genome.

Virus injection

Dengue virus serotype 2 (DENV-2), strains 92T [9] and ET300 were isolated from human serum collected from patients from Townsville, Australia, in 1992 and East Timor in 2000, respectively. DENV-2 (strains 92T and ET300) was propagated and quantified as described by Frentiu et al [29]. For virus injection, 8 day old D. melanogaster females (w1118wMel and w1118tet) and A. aegypti females (MGYP2 and MGYP2tet) were briefly anesthetized with CO2 and injected under a dissecting scope into their thorax with a pulled glass capillary and a handheld microinjector (Nanoject II, Drummond Sci.). 69 µl of virus stock (107 pfu/ml) or sterile PBS 1X were injected. After injection flies and mosquitoes were maintained under identical controlled conditions, low-density (10 females per vial or cup), at 25°C with 60% relative humidity and 12-h light/dark cycle. Insects were collected 8 days post-injection and kept at −80°C for RNA extraction.

Quantitative DENV-2 PCR analysis

RNA extraction was done on 15 individual 16 day old females per condition using Trizol (Invitrogen). 1 µg of total RNA was kept to quantify DENV-2 while the rest was used for immune gene expression analysis as described below.

Accumulation of genomic (+RNA) RNA strands was assessed by quantitative real time PCR using hydrolysis probes specific to the 3′ UTR region of the four dengue serotypes [39] with modifications (A.T. Pyke, unpublished data). The sequences of the primers were FWD: 5′-AAGGACTAGAGGTTAGAGGAGACCC-3′ and RWD: 5′-CGTTCTGTGCCTGGAATGATG-3′ and the sequence of the probe was 5′- AACAGCATATTGACGCTGGGAGAGACCAGA-3′. 1 µg of total RNA for each sample was mixed with 0.625 µM of the reverse primer plus 0.2 mM dNTPs. Samples were incubated at 86°C for 15 minutes and 5 minutes on ice, then 5X first strand buffer and 100 U of Superscript III (Invitrogen) was added to a total volume of 20 µl. Samples were incubated at 25°C for 10 minutes, followed by 42°C for 50 minutes and 10 minutes at 95°C to inactivate the transcriptase.

The qPCR reaction consisted of 2 µl of the synthesized cDNAs, 5 µl of 2X LightCycler 480 Probes Master (Roche), 0.5 µM of each primer (see above) and 0.5 µM of the probe (see above) in 10 µl total volume. Reactions were performed in duplicate in a LightCycler 480 Instrument (Roche) with the following conditions: 95°C for 5 minutes, and 45 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 60°C for 15 s, 72°C for 1 s. A standard curve was created by cloning the DENV-2 3′UTR region fragment into pGEM® T-Easy (Promega). After linearization with Pst I the plasmid was serially diluted into known concentrations and run in parallel, in order to determine the absolute number of DENV-2 copies in each 1 µg of total RNA. First, percentages of individuals infected with dengue were calculated for each treatment. Then only individuals with dengue infection (non zero quantification) were used to examine the effect of wMel on dengue titer using Mann-Whitney U tests (Graph Pad Prism 5).

Quantitative PCR analysis of immune genes

RNA extraction from flies was done using between 10 to 15 individual 8 day old females per condition using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen). To eliminate any contamination by DNA, samples were treated with DNase I recombinant (Roche), in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. cDNAs were synthesized from 1 µg of total RNA, using oligodT primers and the SuperScript III enzyme (Invitrogen), in accordance with manufacturer's instructions. For each sample qRT-PCR was performed in triplicate on a 10 times dilution of the cDNAs using Platinum SYBR Green (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Primers are listed in Table S4. The temperature profile of the qPCR was 50°C for 2 minutes (UDG incubation), 95°C for 2 minutes, 45 cycles of 95°C for 5 s, 60°C for 5 s, 72°C for 10 s with fluorescence acquisition of 78°C at the end of each cycle, then a melting curve analysis after the final cycle. The housekeeping gene rpS17 was used to normalize expression. Target gene to housekeeping gene ratios were obtained for each biological replicate using Q-Gene software [40]. Raw data were graphed as median ± interquartile range (IQR) and outliers beyond 1.5 IQR excluded. Treatment effects on expression ratios were then examined using the Mann-Whitney U tests (Graph Pad Prism 5). The occurrence of false positives was corrected using the q-value [33], [34].

Supporting Information

Immune gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster in response to wMel and DENV-2. The expression of immune genes was analyzed by qRT-PCR on individual females injected either with DENV-2 strain 92T (w1118wMel D+, w1118tet D+) or PBS (w1118wMel PBS, w1118tet PBS) in presence/absence of Wolbachia strain wMel. Flies were collected 8 days post-injection. Graphs show the target gene to house-keeping gene expression ratio (n = 15, Mann-Whitney U test with q-value adjustment, *: q<0.05, **: q<0.01, ***<0.001).

(TIF)

Correlation analysis between dengue titer and immune gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster in presence/absence of Wolbachia strain wMel (w1118wMel, w1118tet). The values were compared using Spearman correlation coefficients.

(TIF)

Aedes aegypti transcriptional responses common to wMel and wMelPop-CLA infections. Transcripts are ranked by the magnitude of Absolute Fold Change (AFC). Transcript identifiers (Transcript ID) and Description were compiled from Vectorbase. Drosophila melanogaster Gene Identifier (Dm Gene ID) and Symbol were compiled from Flybase.

(XLS)

Aedes aegypti transcriptional responses to wMelPop-CLA infection. Transcripts are ranked by the magnitude of Absolute Fold Change (AFC). Transcript identifiers (Transcript ID) and Description were compiled from Vectorbase. Drosophila melanogaster Gene Identifier (Dm Gene ID) and Symbol were compiled from Flybase.

(XLS)

Aedes aegypti transcriptional responses to wMel infection. Transcripts are ranked by the magnitude of Absolute Fold Change (AFC). Transcript identifiers (Transcript ID) and Description were compiled from Vectorbase. Drosophila melanogaster Gene Identifier (Dm Gene ID) and Symbol were compiled from Flybase.

(XLS)

Oligonucleotide primers used in Real-time qPCR experiments.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the O'Neill and McGraw labs for helpful discussion, B. Wee for his help with the Gene Ontology program, J. Popovici for his help with the TaqMan assay, F. Frentiu for virus stock maintenance and virus injection advice, E. Caragata and T. Walker for their help with virus injection. We also thank the Queensland Institute of Medical Research and Queensland Health Forensic and Scientific Services for supplying viruses.

Footnotes

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

The work was funded by a grant from the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health through the Grant Challenges in Global Health Initiative of the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Werren JH, Baldo L, Clark ME. Wolbachia: master manipulators of invertebrate biology. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:741–751. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hoffmann AA, Hercus M, Dagher H. Population dynamics of the Wolbachia infection causing cytoplasmic incompatibility in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1998;148:221–231. doi: 10.1093/genetics/148.1.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hedges LM, Brownlie JC, O'Neill SL, Johnson KN. Wolbachia and Virus Protection in Insects. Science. 2008;322:702–702. doi: 10.1126/science.1162418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Teixeira L, Ferreira A, Ashburner M. The bacterial symbiont Wolbachia induces resistance to RNA viral infections in Drosophila melanogaster. PloS Biol. 2008;6:2753–2763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Osborne SE, Leong YS, O'Neill SL, Johnson KN. Variation in antiviral protection mediated by different Wolbachia strains in Drosophila simulans. PloS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000656. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xi ZY, Khoo CCH, Dobson SL. Wolbachia establishment and invasion in an Aedes aegypti laboratory population. Science. 2005;310:326–328. doi: 10.1126/science.1117607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McMeniman CJ, Lane RV, Cass BN, Fong AW, Sidhu M, et al. Stable introduction of a life-shortening Wolbachia infection into the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Science. 2009;323:141–144. doi: 10.1126/science.1165326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walker T, Johnson PH, Moreira LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Frentiu FD, et al. A non-virulent Wolbachia infection blocks dengue transmission and rapidly invades Aedes aegypti populations. Nature. 2011;476:450–453. doi: 10.1038/nature10355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moreira LA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Jeffery JA, Lu G, Pyke AT, et al. A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell. 2009;139:1268–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kambris Z, Cook PE, Phuc HK, Sinkins SP. Immune activation by life-shortening Wolbachia and reduced filarial competence in mosquitoes. Science. 2009;326:134–136. doi: 10.1126/science.1177531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kambris Z, Blagborough AM, Pinto SB, Blagrove MSC, Godfray HCJ, et al. Wolbachia stimulates immune gene expression and inhibits Plasmodium development in Anopheles gambiae. PloS Pathog. 2010;6:e1001143. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bian G, Xu Y, Lu P, Xie Y, Xi Z. The endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia induces resistance to dengue virus in Aedes aegypti. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000833. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xi Z, Ramirez JL, Dimopoulos G. The Aedes aegypti toll pathway controls dengue virus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000098. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bourtzis K, Pettigrew MM, O'Neill SL. Wolbachia neither induces nor suppresses transcripts encoding antimicrobial peptides. Insect Mol Biol. 2000;9:635–639. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2583.2000.00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wong ZS, Hedges LM, Brownlie JC, Johnson KN. Wolbachia-mediated antibacterial protection and immune gene regulation in Drosophila. PloS One. 2011;6:e25430. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffmann AA, Montgomery BL, Popovici J, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Johnson PH, et al. Successful establishment of Wolbachia in Aedes populations to suppress dengue transmission. Nature. 2011;476:454–U107. doi: 10.1038/nature10356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Walker T, O'Neill SL. Wolbachia and the biological control of mosquito-borne disease. Embo R. 2011;12:508–518. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Min KT, Benzer S. Wolbachia, normally a symbiont of Drosophila, can be virulent, causing degeneration and early death. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:10792–10796. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.20.10792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JH, Budanov AV, Park EJ, Birse R, Kim TE, et al. Sestrin as a feedback inhibitor of TOR that prevents age-related pathologies. Science. 2010;327:1223. doi: 10.1126/science.1182228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Turley AP, Moreira LA, O'Neill SL, McGraw EA. Wolbachia infection reduces blood-feeding success in the dengue fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti. PloS Negl Trop Dis. 2009;3:e516. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tang H. Regulation and function of the melanization reaction in Drosophila. Fly. 2009;3:105. doi: 10.4161/fly.3.1.7747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McMeniman CJ, Lane AM, Fong AWC, Voronin DA, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, et al. Host adaptation of a Wolbachia strain after long-term serial passage in mosquito cell lines. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:6963–6969. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01038-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Waterhouse RM, Kriventseva EV, Meister S, Xi Z, Alvarez KS, et al. Evolutionary dynamics of immune-related genes and pathways in disease-vector mosquitoes. Science. 2007;316:1738. doi: 10.1126/science.1139862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunkov B, Georgieva T. Insect iron binding proteins: insights from the genomes. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;36:300–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ibmb.2006.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luplertlop N, Surasombatpattana P, Patramool S, Dumas E, Wasinpiyamongkol L, et al. Induction of a peptide with activity against a broad spectrum of pathogens in the Aedes aegypti salivary gland, following infection with dengue virus. PloS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001252. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Christensen BM, Li J, Chen CC, Nappi AJ. Melanization immune responses in mosquito vectors. Trends Parasitol. 2005;21:192–199. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2005.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ding SW. RNA-based antiviral immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010;10:632–644. doi: 10.1038/nri2824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glaser RL, Meola MA. The native Wolbachia endosymbionts of Drosophila melanogaster and Culex quinquefasciatus increase host resistance to West Nile virus infection. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11977. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Frentiu FD, Robinson J, Young PR, McGraw EA, O'Neill SL. Wolbachia-mediated resistance to dengue virus infection and death at the cellular Level. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13398. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brackney DE, Scott JC, Sagawa F, Woodward JE, Miller NA, et al. C6/36 Aedes albopictus cells have a dysfunctional antiviral RNA interference response. PloS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e856. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yamada R, Iturbe-Ormaetxe I, Brownlie JC, O'Neill SL. Functional test of the influence of Wolbachia genes on cytoplasmic incompatibility expression in Drosophila melanogaster. Insect Mol Biol. 2011;20:75–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2010.01042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caragata E, Poinsignon A, Moreira L, Johnson P, Leong Y, et al. Improved accuracy of the transcriptional profiling method of age grading in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes under laboratory and semi field cage conditions and in the presence of Wolbachia infection. Insect Mol Biol. 2011;20:215–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2010.01059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Storey JD, Dai JY, Leek JT. The optimal discovery procedure for large-scale significance testing, with applications to comparative microarray experiments. Biostatistics. 2007;8:414–432. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxl019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Storey JD, Tibshirani R. Statistical significance for genomewide studies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:9440. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1530509100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Durinck S, Moreau Y, Kasprzyk A, Davis S, De Moor B, et al. BioMart and Bioconductor: a powerful link between biological databases and microarray data analysis. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:3439. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawson D, Arensburger P, Atkinson P, Besansky NJ, Bruggner RV, et al. VectorBase: a data resource for invertebrate vector genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D583. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grossmann S, Bauer S, Robinson P, Vingron M. An improved statistic for detecting over-represented gene ontology annotations in gene sets. In: Apostolico A, Guerra C, Istrail S, Pevzner PA, Waterman M, editors. Research in Computational Molecular Biology. Berlin: Springer; 2006. pp. 85–98. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grossmann S, Bauer S, Robinson PN, Vingron M. Improved detection of overrepresentation of Gene-Ontology annotations with parent child analysis. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:3024. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warrilow D, Northill JA, Pyke A, Smith GA. Single rapid TaqMan fluorogenic probe based PCR assay that detects all four dengue serotypes. J Med Virol. 2002;66:524–528. doi: 10.1002/jmv.2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Simon P. Q-Gene: processing quantitative real-time RT-PCR data. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1439. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Immune gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster in response to wMel and DENV-2. The expression of immune genes was analyzed by qRT-PCR on individual females injected either with DENV-2 strain 92T (w1118wMel D+, w1118tet D+) or PBS (w1118wMel PBS, w1118tet PBS) in presence/absence of Wolbachia strain wMel. Flies were collected 8 days post-injection. Graphs show the target gene to house-keeping gene expression ratio (n = 15, Mann-Whitney U test with q-value adjustment, *: q<0.05, **: q<0.01, ***<0.001).

(TIF)

Correlation analysis between dengue titer and immune gene expression in Drosophila melanogaster in presence/absence of Wolbachia strain wMel (w1118wMel, w1118tet). The values were compared using Spearman correlation coefficients.

(TIF)

Aedes aegypti transcriptional responses common to wMel and wMelPop-CLA infections. Transcripts are ranked by the magnitude of Absolute Fold Change (AFC). Transcript identifiers (Transcript ID) and Description were compiled from Vectorbase. Drosophila melanogaster Gene Identifier (Dm Gene ID) and Symbol were compiled from Flybase.

(XLS)

Aedes aegypti transcriptional responses to wMelPop-CLA infection. Transcripts are ranked by the magnitude of Absolute Fold Change (AFC). Transcript identifiers (Transcript ID) and Description were compiled from Vectorbase. Drosophila melanogaster Gene Identifier (Dm Gene ID) and Symbol were compiled from Flybase.

(XLS)

Aedes aegypti transcriptional responses to wMel infection. Transcripts are ranked by the magnitude of Absolute Fold Change (AFC). Transcript identifiers (Transcript ID) and Description were compiled from Vectorbase. Drosophila melanogaster Gene Identifier (Dm Gene ID) and Symbol were compiled from Flybase.

(XLS)

Oligonucleotide primers used in Real-time qPCR experiments.

(DOC)