Abstract

After assessing cell viability (CV), tissue-engineered constructs are often discarded, as current CV assays commonly require specific (fluorescent) dyes to stain cells and may need scaffold/tissue digestion before quantifying the live and dead cells. Here, we demonstrate and evaluate how cellular auto-fluorescence can be exploited to facilitate a noninvasive CV estimation in three-dimensional scaffolds using two advanced microscopy methods. Mixtures of live and dead C2C12 myoblasts (0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% live cells) were prepared, and CV was determined before seeding cells into collagen carriers using the trypan blue (TB) assay. Cell-seeded collagen gels ([CSCGs], n=5/cell mixture) were produced by mixing collagen solution with the live/dead cell mixtures (7×106 cells/mL). After polymerization, two-photon microscopy (TPM) and confocal microscopy images of the CSCG were acquired (n=30 images/CSCG). It was found that live and dead cells systematically emit auto-fluorescent light with different spectral characteristics. Viable cells showed predominantly blue fluorescence with a peak emission around 470 nm, whereas dead cells appeared to mainly emit green fluorescent light with a peak intensity around 560 nm. For TPM, live and dead cells were distinguished spectrally. For confocal images, the intensity ratio of images taken with band-pass filters was used to distinguish live from dead cells. CV values obtained with both TPM and confocal imaging did not significantly differ from those acquired with the established TB method. In comparison to TPM, confocal microscopy was found to be less accurate in assessing the exact CV in constructs containing mostly live or dead cells. In summary, monitoring cellular auto-fluorescence using advanced microscopy techniques allows CV assessment requiring no additional dyes and/or scaffold digestion and, thus, may be especially suitable for tissue-engineering studies where CV is measured at multiple time points.

Introduction

Cell viability (CV) is an important parameter in tissue engineering and culture studies to evaluate the effect of environmental conditions on cell behavior. Currently, several methods to determine CV in three-dimensional (3D) scaffolds exist.1,2 Common to all CV assays is their rather invasive nature, for example, by requiring specific dyes to specifically stain live and dead cells. Some assays may even need the scaffold/tissue to be digested before staining and quantifying the live and dead cells. For instance, the most accurate CV estimation technique for 3D scaffolds,1 the trypan blue (TB) method, can only be utilized after scaffold degradation. The TB dye is mixed with the cell solution and selectively enters dead cells allowing the quantification of live (uncolored) and dead (colored) cells. Due to the required staining and/or scaffold digestion, tissue-engineered constructs are often discarded after CV evaluation, as the utilized dyes may influence cellular activity, for example, gene expression patterns.

One potential method that promises to overcome these limitations is the monitoring of cell auto-fluorescence using advanced fluorescence microscopy techniques such as two-photon microscopy (TPM) and confocal microscopy. Auto-fluorescence is a known cellular property. Cells possess a number of endogenous fluorophores that in summation provide sufficient signals for obtaining fluorescence microscopy images.3–6 The most important endogenous fluorophore is nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH). Among other functions, NADH plays an important role in the energy metabolism of cells, that is, in the production of adenosine triphosphate (ATP).4,7,8 NADH has its peak fluorescence emission at 470 nm, while its oxidized form, NAD+, is nonfluorescent.4,7,9 The intracellular levels of NADH and NAD+ are, thus, direct markers of the cell reduction-oxidation state. Consequently, changes in cellular fluorescence are observable when cells increase or decrease their ATP production or when cells are subjected to perturbations in their metabolic pathways.

Both (confocal) fluorescence microscopy and TPM have been successfully applied to assess the metabolic state of cells by measuring differences in auto-fluorescence resulting from changes in cellular metabolic activity, that is, different levels of NADH.3,6,10–14 Most studies, however, utilized this method to visualize and/or determine different metabolic states of living cells, for example, by determining different cellular reduction-oxidation (redox) states.14,15,16–19 Some studies described auto-fluorescence and redox changes of apoptotic and necrotic cells.10,13,20,21 While these reports indicate the potential of using differences in cellular auto-fluorescence to distinguish live from dead cells, according to our knowledge, only Hennings et al.12 applied it to differentiate viable from necrotic (thermally induced) cells. In their report, fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue sections were visualized using a fluorescence microscope. Aside from not being applicable to monitor CV in living 3D constructs or tissues, their results are limited by utilizing formaldehyde to fix tissue sections, which may influence cellular auto-fluorescence.22 In addition, to our knowledge, no systematic investigation exists that addresses the usage of auto-fluorescence to assess CV in 3D constructs.

Using cell populations of known percent viability seeded into collagen gels, we first evaluated the feasibility of using TPM and confocal microscopy to distinguish live from dead cells based on differences in auto-fluorescence. Second, we compared two microscopy methods for quantitative determination of CV with the established TB viability assay.

Materials and Methods

Cell source and expansion

C2C12 murine myoblasts (ECACC) were cultured at 37°C, 5% CO2, and at full humidity in growth medium containing 85% high-glucose Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (Invitrogen), 15% fetal bovine serum (Lonza), 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Lonza), and 1% nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen). Every 2–3 days, the cells were passaged.

Preparation of CV mixtures

Cells were detached using 1% trypsin, centrifuged (250 g, 5 min), and re-suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). To prepare dead cells, 1 mL of 1 N HCl was added to 9 mL of cell suspension (10 min incubation at room temperature).1 Afterwards, the dead cells were washed twice with 10 mL PBS. Subsequently, the concentration of the live and dead cell solutions was determined using the TB assay in standard fashion. Briefly, the TB dye selectively enters dead cells, coloring them dark blue, and, subsequently, live and dead cells were hand-counted using a Neubauer improved hemocytometer. The two solutions were then mixed at 0/100%, 25/75%, 50/50%, 75/25%, and 100/0% live/dead ratios. After mixing, the actual produced live/dead ratio (MIX) was measured in triplicate (TB assay).

Preparation of cell-seeded collagen gels

Cell-seeded collagen gels (CSCGs) were produced by mixing 255 μL of acid-solubilized rat-tail tendon collagen type I solution (2 mg/mL final collagen concentration; BD Biosciences), 245 μL growth medium, and 6 μL of 1 N NAOH and the prepared cell solutions of known live/dead ratio at 7×106 cells/mL (n=5/MIX). Subsequently, the collagen-cell mixtures were cast into the wells (∼18 mm diameter) of a 24-well plate (500 μL collagen-cell mix/well). Gels were allowed to polymerize for 30 min at 37°C before 2 mL of growth medium was added. The construct was put back into the incubator and left to continue polymerization for 2 h before imaging. Two separate sets of cell mixtures were produced to make two separate set of gels, one for TPM and the other for confocal microscopy.

Two-photon and confocal microscopy

Two photon images of the CSCGs were acquired on a Zeiss LSM 510 META NLO lazer scanning microscope, and confocal images were obtained on a Zeiss LSM 510 laser scanning microscope with a 62×, 1.2 numerical aperture (NA) water immersion objective (Carl Zeiss GmbH). Images were taken approximately 20–40 μm deep into the CSCG. For TPM, the excitation light source was a mode-locked Ti:Sapphire Chameleon laser (Coherent Inc.) tuned to an excitation wavelength of 730 nm. The laser output was set to 5%. Fluorescence emission was discriminated with a 650 nm short-pass dichroic mirror and transmitted to the appropriate detector unit. Confocal imaging utilized 458 nm excitation with the laser output set to 100%. The emitted fluorescent light was discriminated with a 458 nm main dichroic mirror and transmitted to the appropriate detector unit.

Two photon spectral images were measured by diverting the emitted auto-fluorescence to a diffraction grating and detecting 19 wavelength bands centered from 405 to 608 nm (in steps of approx. 10.7 nm) using the META detector of the microscope. The spectrally separated light is transmitted to 19 photo-multiplier tubes (PMTs) of the META detector, and the number of photons per spectral band is counted. Subsequently, the microscope's internal software generates a spectral image by analyzing the frequency of photons detected in each individual PMT. Per pixel, the tube detecting the majority of photons is determined and a color, that is, pixel value, is assigned, representative of the spectral band the PMT is detecting. For instance, if the majority of photons are measured in the PMT covering 549–560 nm, the pixel is colored in green, as this spectral band is within the green visible spectrum. Emission spectra were obtained by manually outlining regions-of-interest (ROI) on the spectral images using the ROI selection tool of the microscope image-analysis software (Zeiss LSM Image Browser). The emission spectra were extracted from the ROIs presumed to represent the cell cytoplasm and mitochondria. Postprocessing of the spectra data included averaging and calculation of standard deviations using the MATLAB software environment (The Mathworks).

Confocal image pairs were acquired by consecutively imaging CSCGs through a 475–525 nm band-pass filter (image 1) and a 560–615 nm band-pass filter (image 2), respectively. A custom-written MATLAB script was used to identically outline the same cells visualized on image 1 and 2, and their corresponding intensities (pixel values) were obtained and averaged. An intensity ratio per imaged cell was determined by dividing the cell's averaged intensity from image 1 by the averaged intensity from image 2.

Threshold determination for confocal microscopy images

Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analysis12 was performed to identify a threshold ratio to distinguish live from dead cells on confocal images. Intensity ratios of cells in the CSCGs with 0% and 100% CV were obtained, and a ROC curve was calculated (PASW Statistics Release 18.0.0, SPSS, Inc., www.spss.com). The intensity ratio corresponding to the maximum sum of sensitivity and specificity on the calculated ROC curve was identified as the threshold ratio.

CV assessment

The number of live and dead cells per two-photon spectral image (n=20 images/CSCG with at least 100 cells imaged) of each gel (n=5/MIX) was counted. Likewise, the number of live and dead cells per confocal intensity image pair (n=30 image pairs/gel with at least 150 cells imaged) of each gel (n=5/MIX) was determined. Subsequently, all living and dead cells were summarized, and CV per imaged gel was defined as

|

where l and d are the total number of visualized living and dead cells per carrier, respectively.

Statistical analysis

The measured CV values obtained with the two different CV assessment methods were examined for significant differences compared with their corresponding TB assays using two separate two-way analysis of variance tests. The dependent variable was defined as the measured CV values. The two factors were defined as the method to assess CV (microscopic and TB) and the targeted CV sub-groups (0%, 25%, 50%, 75% and 100%). If no significant interaction effect was found, a one-way analysis-of-variance test with Tukey-HSD post-hoc testing was employed to search for significant differences in either targeted CV or CV assessment method within the other factor level. Otherwise, an independent t-test with Bonferroni correction for number of applied comparisons (k=5) was used to test for significant differences between each specific CV assessment method and targeted CV sub-group. Statistical significance was assumed for p<0.05. All statistical tests were performed using PASW Statistics Release 18.0.0 (SPSS, Inc., www.spss.com).

Results

Cell classification using auto-fluorescence

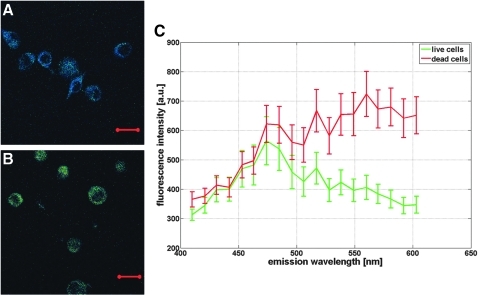

Two-photon excitation resulted in live and dead cells systematically emitting fluorescent light with different spectral characteristics. Viable cells showed predominantly blue fluorescence with a peak emission around 470 nm, the typical emission wavelength of NADH (Fig. 1A, C). In contrast, dead cells appeared to mainly emit green fluorescent light with a peak intensity around 560 nm (Fig. 1B, C). Emission spectra of live and dead cells largely overlapped for emission wavelengths between 400 and 500 nm. In the spectral range above 500 nm, the spectra showed an opposite behavior. While the averaged fluorescent intensity of live cells rapidly decreased with increasing wavelength, the dead cells' fluorescence intensity increased and remained elevated. These spectral differences resulted in live cells appearing blue and dead cells appearing green on the color-coded two-photon images, allowing an easy and direct cell classification (Fig. 1A, B). In a few exceptions, the color coding was ambiguous, and the emission spectra of the cells in question were examined. For classification, the spectra were normalized to their intensity at 470 nm. Cells with a peak intensity at 470 nm were categorized as living, and cells with a peak intensity at 560 nm were categorized as dead, respectively. In all observed cases, this extra check successfully categorized cells as either live or dead.

FIG. 1.

Characteristic two-photon spectral images of cell-seeded collagen gels (CSCGs) with (A) 100% cell viability (CV) and (B) 0% CV. Bar is 20 μm, Magnification 630×. (C) Respective emission spectra of 50 live (green) and 50 dead (red) cells illustrating distinct spectral differences between live and dead cells. Values are mean +/− standard deviations.

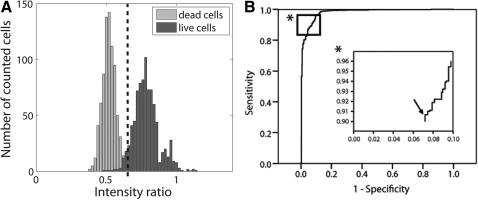

The observed spectral differences in the emitted fluorescent light of live and dead cells were also reflected in the intensity ratios obtained from the confocal image pairs. On average, live cells had larger intensity ratios than dead cells due to their decreased fluorescence emission above 500 nm (Fig. 2A). The small overlap in the distribution of intensity ratios of live and dead cells indicated a good potential to classify them using a threshold intensity ratio. The ROC curve shows how the sensitivity and specificity of such a classification rule changes with different settings of a threshold ratio (Fig. 2B). The best combination of sensitivity and specificity was attained for a threshold ratio of 0.68, corresponding to 91% sensitivity and 93% specificity. In other words, 771 of the 847 live cells imaged in the CSCGs with 100% CV had their intensity ratio above the threshold ratio (91% sensitivity), while 813 of the 847 dead cells visualized in the CSCG with 0% CV had their ratio below the threshold (93% specificity). Consequently, when assessing viability using confocal ratio imaging, cells with intensity ratio above the threshold value were classified as viable, whereas cells with a lower intensity ratio were classified as dead.

FIG. 2.

(A) Histogram of intensity ratios of the CSCGs with 0% and 100% CV. Dashed line represents the threshold ratio of 0.68 as calculated by Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) analysis. (B) Corresponding ROC curve for classifying intensity ratios via a ratio threshold. (*) Detail of the ROC curve; arrow in the insert denotes where the sum of sensitivity (number of correctly identified live cells/total number of live cells) and specificity (number of correctly identified dead cells/total number of dead cells) is maximized (91% and 93%, respectively), which corresponds to a threshold of 0.68.

Viability assessment

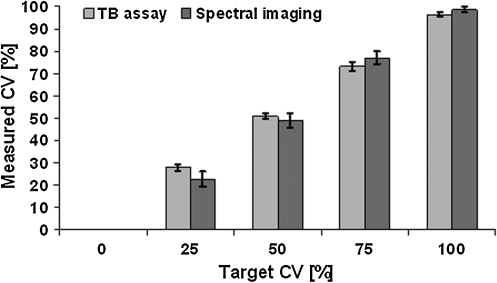

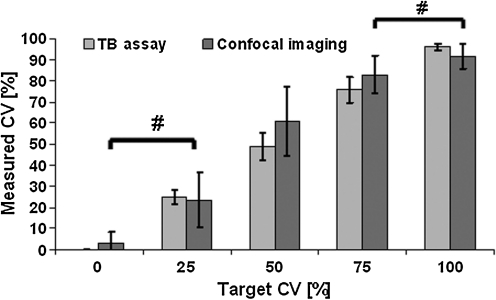

The CV values determined using the TB assay and the measured CV using two-photon spectral imaging and confocal ratio imaging all matched well the targeted CV (Figs. 3 and 4). The obtained values of all three methods showed a clear gradient from 0% to 100% CV with a significant effect of the CV mixture. More importantly, both microscopy techniques showed similar accuracy in determining CV as the TB method. In the case of TB assay versus two-photon spectral imaging, no significant differences in assessing CV were found between the two methods. There was, however, a significant interaction effect, which was attributed to significantly different CV values (p<0.01) for CSCGs containing 100% live cells (Fig. 3). However, this is an artifact, of less than 100% CV as measured by TB and very low within group variance, as the methods themselves did not have a significant effect. In the second case, confocal microscopy versus TB assay, also no significant differences in measuring CV was found between the two techniques. Furthermore, no significant interaction between the two CV assessment methods was determined. However, the individual set of CV values obtained with confocal microscopy did not show significant differences between the 0% versus 25%, and 75% versus 100% targeted CV sub-groups. In other words, confocal microscopy failed to distinguish between CSCGs containing 0% versus 25%, and 75% versus 100% targeted CVs. In contrast, all TB viability groups were significantly different from each other (Fig. 4).

FIG. 3.

Measured cell viabilities as evaluated using two methods, Trypan blue (TB) assay and two-photon spectral imaging, for five different targeted cell mixtures (0%, 25%, 50%, 75%, and 100% living cells). Values are means +/− standard deviations, n=5.

FIG. 4.

Measured cell viabilities as evaluated using two methods, TB assay and confocal ratio imaging, for five different targeted cell mixtures. Values are means +/− standard deviations, n=5. # denotes p>0.05 between target CV categories within the confocal CV assessment method.

Discussion

Rather than showing only differences in intensity, the auto-fluorescence emission of live and dead cells was found to be characterized by distinct spectral differences. Analysis of two-photon fluorescence emission spectra showed that live cells emit predominantly blue fluorescent light with a peak intensity around 470 nm, the typical emission wavelength of NADH (Fig. 1). In contrast, dead cells emit mainly green fluorescent light with a peak intensity at 560 nm (Fig. 1). Using advanced microscopy methods, these spectral differences could be exploited to accurately differentiate viable from dead cells and to assess the CV of cell-seeded 3D constructs. In fact, CV values obtained with either two-photon spectral imaging or confocal ratio imaging were not significantly different from those acquired with the established TB viability assay. In comparison to TPM, confocal microscopy was found to be less accurate in measuring CV of CSCGs containing mostly live or dead cells. This illustrates the dependency of confocal ratio imaging on defining a good intensity ratio threshold to categorize cells.

The exact underlying mechanism that causes the measured differences in auto-fluorescence emission remains to be investigated. Initially, we hypothesized that dead cells emit fluorescent light with stronger intensity. The increase was attributed to larger intracellular NADH levels presumably resulting from the absence of oxidative phosphorylation in non-viable cells. Indeed, examination of the measured emission spectra of dead cells shows that the fluorescence intensity is elevated compared to viable cells, as the area under the spectrum represents the measured (averaged) total fluorescence intensity (Fig. 1C). However, the determined increase cannot be solely attributed to larger NADH levels, as the major differences were observed for emission wavelengths greater than 500 nm. For this spectral region, NADH emits negligible amounts of fluorescent light.3,4,8,9,10,14 One possible explanation for the observed differences in emission spectra is the presence of flavoproteins (FP). Similar to NADH, this class of proteins exists in any cell type, and FPs are known to play crucial roles in cellular energy metabolism.3,4,8,10,14 However, FPs are characterized by emitting predominantly green fluorescent light with peak intensities typically around 530 nm.8,10,14 In viable cells, both signals, that is, fluorescence from NADH and FP, contribute to the cellular auto-fluorescence. Since the concentration of NADH is typically much larger than that of FP, the fluorescence emission of live cells is characterized by a dominant NADH signal.4,8 Dead cells appear to be subjected to a much larger FP contribution to the measured fluorescence emission. Our results indicated that the measured fluorescence intensity per wavelength continuously increases, peaking at 560 nm, which is well within the characteristic spectral range of FPs. Apparently, cell death causes changes in the relative concentrations of NADH and FP. As cells become necrotic, they lose the integrity of their mitochondrial membranes leaving proteins or compounds unprotected to oxidation.13 Unlike NADH, FPs are fluorescent in their oxidized form and do not fluoresce in their reduced state.8,10 Thus, the enhanced FP contribution to the total fluorescence signal of dead cells may be explained by increased levels of oxidized FP present in nonviable cells.

Supporting our findings are the results of Hennings et al.,12 who distinguished live from heat-fixed (necrotic) cells based on differences in fluorescence intensity. In their study, dead cells exhibited increased fluorescence intensity as compared with viable cells. However, they did not determine the spectral characteristics of the emitted fluorescent light and hence, it remains unclear whether the observed differences were caused by changes in NADH and/or FP levels. In contrast, Pogue et al.13 and Eng et al.10 found that the fluorescence emission of dead cells decreased relative to living cells. One explanation for this discrepancy may be an oscillation in the emitted fluorescent light during cell apoptosis or necrosis, as shown by Ghukasyan et al.11 Initially, the cellular fluorescence emission increased; however, within several hours after cell death, it decreased below its initial value and remained low. These results, however, are contradicted by Georgakoudi et al.,23 who reported an increased fluorescence intensity of apoptotic cells within the same time range. Taken together, these findings illustrate the ongoing uncertainness about the proper interpretation of auto-fluorescence variations found in live and dead cells.8 However, regardless of an actual increase or decrease in fluorescence intensity, all studies reported significant variations in the auto-fluorescence emission of live and dead cells. Hence, these differences can be employed to distinguish cells as in the present study while recognizing the need to clarify the underlying processes.

In a previous study, the TB staining method was found to be the most accurate in assessing CV in 3D scaffolds.1 However, it can only be used with scaffolds/tissue that can be digested without killing any cells. Our results indicate that both TPM and confocal microscopy can be employed to determine CV with similar accuracy and without disintegrating the constructs. Since no dyes with unknown effects on cellular processes, for example, gene expression, are required, CV can be measured longitudinally over time, and constructs can be utilized for other analyses without discarding them after assessment. The TB method is advantageous to the two other methods in terms of simplicity, needed infrastructure, and required lab time and will, therefore, most likely remain the gold standard for assessing CV in vitro. However, both microscopy techniques are, in principle, applicable for determining CV in situ in scaffolds/tissue and possibly in vivo. In addition to noninvasively measuring CV, information on cell distribution and morphology is also provided. Choosing the appropriate microscopy method for one's experiment depends among others on the availability of the microscopy equipment. Two-photon spectral imaging requires specialized equipment, for example, a detector unit capable of extracting spectral information of the emitted fluorescent light. Thus, although less accurate than TPM in determining CV, confocal microscopy represents a valid alternative technique using more generally available equipment.

The current study relies heavily on the accuracy of the CV estimated using the TB assay. This could be considered a potential bias. However, this source of error should be minimal, as the viability was determined before seeding the cells, and the TB method is considered an accurate CV estimation technique. Here, measuring (differences in) auto-fluorescence using advanced microscopy methods was found to accurately assess CV in 3D scaffolds. A few factors may have influenced the good accuracy of two-photon spectral imaging and confocal ratio imaging that could be considered bias. First of all, only a reasonable number of gels (n=5 for each live/dead cell mixture) were imaged. Visualization of more gels with subsequent CV assessment could potentially show that the microscopy techniques and the TB assay do not express the same accuracy, because the power of the statistical analysis would increase. However, such small differences requiring such large sample sizes are often not actually meaningful differences in CV. Estimating the viability exploiting cellular auto-fluorescence depends heavily on visualizing representative numbers of live and dead cells. However, cells from a limited number of regions within the CSCG were visualized possibly overlooking zones of accumulated live or dead cells. Here, all visualized gels were characterized by a relatively even live/dead cell distribution and before imaging the CSCGs, a trial study was performed to estimate how many cells were needed to be visualized in order to obtain a representative CV measurement.

Measuring CV using TPM and confocal microscopy also depends heavily on cells being clearly classifiable as either live or dead. Here, only a few cells could not be directly categorized on the spectral two-photon images, that is, they did not distinctively appear blue (live) or green (dead). Still, classification was achieved by examining the peak intensities in their normalized emission spectra. Confocal microscopy in conjunction with calculating intensity ratios allowed distinguishing live from dead cells; however, some cells were falsely categorized. To facilitate a more accurate CV estimation, different band-pass filters could be chosen. Here, we were limited by our confocal microscopy set-up to utilize a 475–525 nm band pass filter and a 560–615 nm band pass filter, respectively. Apparently, for some cells, the auto-fluorescence emission in these spectral bands partially matches and hence, some calculated intensity ratios led to live cells being identified as dead and vice versa. The observed spectral differences could be better taken advantage of by obtaining confocal image pairs through more narrow band-pass filters, for example, through 460–500 nm and 560–600 nm band pass filters. A different set of filters would possibly result in more distinct intensity ratio distributions of live and dead cells and consequently allow a more accurate cell classification.

In this study, a high NA objective was required to capture the weak auto-fluorescence emission, but its depth penetration is limited to 280 μm. Future in situ or in vivo applications using auto-fluorescence to assess CV will want to consider employing objectives with high enough NA and large enough working distances to image a representative cell population within the tissue/construct. On inverted microscopes, smaller magnifying objectives with high NA could be utilized as they are characterized by larger working distances. Alternatively, for upright confocal or TPM set-ups, water-dipping lenses with high NA could be used due to their even larger working distances (typically above 2 mm). However, even the most advanced TPM set-ups do not penetrate even low light-scattering tissues deeper than 1 mm.24 Therefore, any clinical application of TPM or confocal microscopy to estimate CV requiring deeper tissue penetration will likely rely on the development of endoscopic probes.25 Finally, another issue that might complicate the potential usage of both microscopy techniques is the presence of various cell types in tissues. Intracellular contents of endogenous fluorophores may vary between cell types and species. However, numerous studies on measuring cell metabolism/activity using auto-fluorescence of various cell types from different species have been published; examples include cancer cells,15,26–29 liver cells,30 cornea cells,18,31 skin cells,32–35 stem cells,36 brain cells,37,38 and heart cells.3,10 In these studies, relatively small differences in cellular auto-fluorescence were successfully utilized to determine various metabolic states of live cells. Since differences in auto-fluorescence between live and dead cells are likely larger than between metabolically active and inactive cells, we believe that it is possible to assess the viability of constructs seeded with other cell types than the one in our study. Since each cell population is likely characterized by their individual auto-fluorescence emission, reference spectra and typical intensity ratio threshold values should be obtained for the different cell types.

Conclusion

The results indicate the potential of using differences in auto-fluorescence to distinguish live from dead cells and accurately assess CV in 3D scaffolds. Utilizing advanced microscopy techniques, no dyes were required to stain live and dead cells, and CV could be determined without disintegrating the cell-seeded constructs. In terms of accuracy, both two-photon spectral and confocal ratio imaging perform well as compared with the established TB viability assay, with confocal microscopy being slightly less accurate. Therefore, both microscopy techniques show good potential to be used in (tissue engineering) studies where CV is measured at multiple time points.

Acknowledgments

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Community's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7, 2007–2013) under grant agreement no. HEALTH-F2-2008-201626.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Gantenbein-Ritter B. Potier E. Zeiter S. van der W.M. Sprecher C.M. Ito K. Accuracy of three techniques to determine cell viability in 3D tissues or scaffolds. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2008;14:353. doi: 10.1089/ten.tec.2008.0313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rauch B. Edwards R.B. Lu Y. Hao Z. Muir P. Markel M.D. Comparison of techniques for determination of chondrocyte viability after thermal injury. Am J Vet Res. 2006;67:1280. doi: 10.2460/ajvr.67.8.1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang S. Heikal A.A. Webb W.W. Two-photon fluorescence spectroscopy and microscopy of NAD(P)H and flavoprotein. Biophys J. 2002;82:2811. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75621-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heikal A.A. Intracellular coenzymes as natural biomarkers for metabolic activities and mitochondrial anomalies. Biomark Med. 2010;4:241. doi: 10.2217/bmm.10.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li Q. Seeger S. Autofluorescence detection in analytical chemistry and biochemistry. Appl Spectrosc Rev. 2010;45:12. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rocheleau J.V. Head W.S. Piston D.W. Quantitative NAD(P)H/flavoprotein autofluorescence imaging reveals metabolic mechanisms of pancreatic islet pyruvate response. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:31780. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M314005200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ying W. NAD+/NADH and NADP+/NADPH in cellular functions and cell death: regulation and biological consequences. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:179. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang H.W. Wei Y.H. Guo H.W. Reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) fluorescence for the detection of cell death. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2009;9:1012. doi: 10.2174/187152009789377718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kierdaszuk B. Malak H. Gryczynski I. Callis P. Lakowicz J.R. Fluorescence of reduced nicotinamides using one- and two-photon excitation. Biophys Chem. 1996;62:1. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(96)02182-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eng J. Lynch R.M. Balaban R.S. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide fluorescence spectroscopy and imaging of isolated cardiac myocytes. Biophys J. 1989;55:621. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(89)82859-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghukasyan V.V. Kao F.J. Monitoring cellular metabolism with fluorescence lifetime of reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide. J Phys Chem C. 2009;113:11532. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hennings L. Kaufmann Y. Griffin R. Siegel E. Novak P. Corry P. Moros E.G. Shafirstein G. Dead or alive? Autofluorescence distinguishes heat-fixed from viable cells. Int J Hyperthermia. 2009;25:355. doi: 10.1080/02656730902964357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pogue B.W. Pitts J.D. Mycek M.A. Sloboda R.D. Wilmot C.M. Brandsema J.F. O'Hara J.A. In vivo NADH fluorescence monitoring as an assay for cellular damage in photodynamic therapy. Photochem Photobiol. 2001;74:817. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2001)074<0817:ivnfma>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tiede L.M. Rocha-Sanchez S.M. Hallworth R. Nichols M.G. Beisel K. Determination of hair cell metabolic state in isolated cochlear preparations by two-photon microscopy. J Biomed Opt. 2007;12:021004. doi: 10.1117/1.2714777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Skala M.C. Riching K.M. Gendron-Fitzpatrick A. Eickhoff J. Eliceiri K.W. White J.G. Ramanujam N. In vivo multiphoton microscopy of NADH and FAD redox states, fluorescence lifetimes, and cellular morphology in precancerous epithelia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708425104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirkpatrick N.D. Zou C. Brewer M.A. Brands W.R. Drezek R.A. Utzinger U. Endogenous fluorescence spectroscopy of cell suspensions for chemopreventive drug monitoring. Photochem Photobiol. 2005;81:125. doi: 10.1562/2004-08-09-RA-267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mujat C. Greiner C. Baldwin A. Levitt J.M. Tian F. Stucenski L.A. Hunter M. Kim Y.L. Backman V. Feld M. Munger K. Georgakoudi I. Endogenous optical biomarkers of normal and human papillomavirus immortalized epithelial cells. Int J Cancer. 2008;122:363. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park C.Y. Zhu Z. Zhang C. Moon C.S. Chuck R.S. Cellular redox state predicts in vitro corneal endothelial cell proliferation capacity. Exp Eye Res. 2006;83:903. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Quesada I. Todorova M.G. Soria B. Different metabolic responses in alpha-, beta-, and delta-cells of the islet of Langerhans monitored by redox confocal microscopy. Biophys J. 2006;90:2641. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.069906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levitt J.M. Baldwin A. Papadakis A. Puri S. Xylas J. Munger K. Georgakoudi I. Intrinsic fluorescence and redox changes associated with apoptosis of primary human epithelial cells. J Biomed Opt. 2006;11:064012. doi: 10.1117/1.2401149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brewer M. Utzinger U. Li Y. Atkinson E.N. Satterfield W. Auersperg N. Richards-Kortum R. Follen M. Bast R. Fluorescence spectroscopy as a biomarker in a cell culture and in a nonhuman primate model for ovarian cancer chemopreventive agents. J Biomed Opt. 2002;7:20. doi: 10.1117/1.1427672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.König K. Schneckenburger H. Laser-induced autofluorescence for medical diagnosis. J Fluoresc. 1994;4:17. doi: 10.1007/BF01876650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Georgakoudi I. Levitt J. Baldwin A. Papadakis A. Munger K. Intrinsic fluorescence changes associated with apoptosis of human epithelial keratinocytes. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99:S54. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Theer P. Hasan M.T. Denk W. Two-photon imaging to a depth of 1000 microm in living brains by use of a Ti:Al2O3 regenerative amplifier. Opt Lett. 2003;28:1022. doi: 10.1364/ol.28.001022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu Y. Leng Y. Xi J. Li X. Scanning all-fiber-optic endomicroscopy system for 3D nonlinear optical imaging of biological tissues. Opt Express. 2009;17:7907. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.007907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Georgakoudi I. Jacobson B.C. Muller M.G. Sheets E.E. Badizadegan K. Carr-Locke D.L. Crum C.P. Boone C.W. Dasari R.R. Van D.J. Feld M.S. NAD(P)H and collagen as in vivo quantitative fluorescent biomarkers of epithelial precancerous changes. Cancer Res. 2002;62:682. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chernyavskiy O. Vannucci L. Bianchini P. Difato F. Saieh M. Kubinova L. Imaging of mouse experimental melanoma in vivo and ex vivo by combination of confocal and nonlinear microscopy. Microsc Res Tech. 2009;72:411. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen R. Chen J.Y. Zhou L.W. Metabolic patterns (NAD(P)H) in rat basophilic leukemia (RBL-2H3) cells and human hepatocellular carcinoma (Hep G2) cells with autofluorescence imaging. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2008;32:193. doi: 10.1080/01913120802397752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu Q. Heikal A.A. Two-photon autofluorescence dynamics imaging reveals sensitivity of intracellular NADH concentration and conformation to cell physiology at the single-cell level. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2009;95:46. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rajwa B. Bernas T. Acker H. Dobrucki J. Robinson J.P. Single- and two-photon spectral imaging of intrinsic fluorescence of transformed human hepatocytes. Microsc Res Tech. 2007;70:869. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masters B.R. Correlation of histology and linear and nonlinear microscopy of the living human cornea. J Biophotonics. 2009;2:127. doi: 10.1002/jbio.200810039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bader A.N. Pena A.M. Johan van Voskuilen C. Palero J.A. Leroy F. Colonna A. Gerritsen H.C. Fast nonlinear spectral microscopy of in vivo human skin. Biomed Opt Express. 2011;2:365. doi: 10.1364/BOE.2.000365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Palero J.A. de Bruijn H.S. van der Ploeg van den Heuvel A. Sterenborg H.J. Gerritsen H.C. Spectrally resolved multiphoton imaging of in vivo and excised mouse skin tissues. Biophys J. 2007;93:992. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.099457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Masters B.R. So P.T. Gratton E. Multiphoton excitation fluorescence microscopy and spectroscopy of in vivo human skin. Biophys J. 1997;72:2405. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78886-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen J. Zhuo S. Luo T. Jiang X. Zhao J. Spectral characteristics of autofluorescence and second harmonic generation from ex vivo human skin induced by femtosecond laser and visible lasers. Scanning. 2006;28:319. doi: 10.1002/sca.4950280604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen W.L. Huang C.H. Chiou L.L. Chen T.H. Huang Y.Y. Jiang C.C. Lee H.S. Dong C.Y. Multiphoton imaging and quantitative analysis of collagen production by chondrogenic human mesenchymal stem cells cultured in chitosan scaffold. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2010;16:913. doi: 10.1089/ten.TEC.2009.0596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drezek R. Sokolov K. Utzinger U. Boiko I. Malpica A. Follen M. Richards-Kortum R. Understanding the contributions of NADH and collagen to cervical tissue fluorescence spectra: modeling, measurements, and implications. J Biomed Opt. 2001;6:385. doi: 10.1117/1.1413209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kwan A.C. Duff K. Gouras G.K. Webb W.W. Optical visualization of Alzheimer's pathology via multiphoton-excited intrinsic fluorescence and second harmonic generation. Opt Express. 2009;17:3679. doi: 10.1364/oe.17.003679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]