Abstract

Prostatitis is a prevalent condition that encompasses a large array of clinical symptoms with significant impacts on men's life. The diagnosis and treatment of this disorder presents numerous challenges for urologists, most notably, a lack of specific and effective diagnostic methods. Chronic bacterial prostatitis is successfully treated with appropriate antibiotics that penetrate the prostate and kill the causative organisms. Prostatitis category III (chronic pelvic pain syndrome) is common, very bothersome, and enigmatic. Symptoms are usually prolonged and, generally speaking, treatment results are unsatisfactory. During the last decade, research has focused on the distress caused by the condition, but although our knowledge has certainly increased, there have been no real breakthroughs; controversies and many unanswered questions remain. Furthermore, the optimal management of category III prostatitis is not known. Conventional prolonged courses of antibiotic therapy have not proven to be efficacious. Novel therapies providing some evidence for efficacy include alpha-blocker, anti-inflammatory phytotherapy, physiotherapy, neuroleptics, and others, each offering therapeutic mechanisms. A stepwise approach involving multimodal therapy is often successful for treating patients. The UPOINT technique has been used to clinically phenotype these patients and drive the appropriate selection of multimodal therapy.

Keywords: Chronic pelvic pain syndrome, Chronic prostatitis, Prostate

INTRODUCTION

Chronic prostatitis (CP) is one of the most prevalent conditions in urology and represents an important international health problem [1]. The prevalence of prostatitis is approximately 5 to 9% in the general male population. Prostatitis accounts for 25% of all visits to urologists, and up to 15 to 25% of visits to urology clinics in Korea [2]. Men diagnosed with CP experience impairment in both mental and physical domains of health-related quality of life as measured through validated questionnaires [3]. The wide scope of recommended treatments for CP indicates both the general uncertainty surrounding the root causes of the condition and how to appropriately diagnose and treat it. Unlike benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) and prostate cancer, which are predominantly diseases of older men, prostatitis affects men of all ages, especially the middle age group. Although category I prostatitis (acute bacterial prostatitis) is relatively straightforward to diagnose by observing a tender prostate on rectal examination with systemic illness (fevers, chills, dysuria) and cytokine release syndrome, it accounts for only approximately 5% of patients with prostatitis (National Institutes of Health [NIH] classification). CP is much more common and more difficult to diagnose and treat. Of the types of CP, chronic bacterial prostatitis (CBP) is rare, accounting for only 5% of such patients [4]. More than 90% of cases of CP are not associated with a significant bacteriuria, a condition referred to as chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS). Cases of CPPS are further subdivided by the presence of inflammation in the extraprostatic secretions or semen (category IIIa) or the absence of it (category IIIb). Many hypotheses have been suggested for the etiology of CPPS, including infection, inflammation, uric acid level, autoimmunity, and neuromuscular spasm. Therapies aimed at these specific etiologies have met with varied success, a result that may reflect the multifactorial nature of the syndrome. This review provides an overview of the current appropriate practice for treating men diagnosed with CP.

DEGREE OF CONFUSION AND FRUSTRATION FOR CP/CPPS

CP is a condition generally acknowledged to be associated with great confusion and frustration for patients and treating physicians alike. In Canada, physicians reported experiencing significantly more frustration in treating prostatitis than they did in treating patients with BPH and prostate cancer and they perceived that prostatitis affected patients' quality of life more significantly than did BPH and almost as significantly as prostate cancer [5]. The degree of frustration for physicians in dealing with prostatitis has been driven primarily by a lack of confidence and comfort in their ability to accurately diagnose and subsequently rationalize treatment. In Japan, more than half of urologists (52.2%; 384/735) felt pessimistic about treating patients with CP/CPPS [6]. The reasons for this included inconsistent reporting of symptoms by patients (78.1%; 300/384), lack of confidence in the treatment (60.4%; 232/384), and lack of confidence in their diagnosis (32%; 123/384). These studies support the common frustration experienced by physicians in diagnosing and treating this disease. The prime causes of the difficulty may be the poorly characterized etiology of CP, the absence of definitive diagnostic tests, and the absence of effective therapies, the sum of which result in physicians feeling pessimistic and lacking confidence in their diagnosis and treatment strategy [7].

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

1. Chronic bacterial prostatitis

Of patients diagnosed with prostatitis syndrome, 5 to 10% are suffering from chronic bacterial prostatitis CBP [4]. This condition is often triggered by an infection of the urinary tract. The pathogen spectrum includes that of complex urinary tract infections, with gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria, although the latter often occur only transiently. Animal experiments have shown that chronic infection leads to the formation of a biofilm in the prostatic acini, leading to pathogens forming colonies with enhanced growth conditions [8].

2. CP and CPPS

Uncertainty exists in the etiology of the majority of CP cases and the etiology of CP syndromes is controversial, particularly when positive cultures for established uropathogens are lacking. It is evident from a previous study that infectious causes are detected in only 8% of patients; the majority of cases appear to suffer from either nonbacterial prostatitis or prostatodynia (NIH category III: CP/CPPS) [9]. This is likely a reason that urologists in the Netherlands (40%), Wisconsin (59%), and China (64.6%) consider nonbacterial factors to be most important in the etiology of the syndrome [10-12]. However, Dutch general practitioners (63%) and primary care physicians (78%) in Wisconsin tended to implicate bacterial infection as the most important cause [10,11]. Recently, molecular biological research has created exciting new possibilities for discovering the root causes of this enigmatic disease. Some evidence suggests that hidden bacterial infection of the prostate is a possible etiology [13]. In Korea, about half (52%) of participating urologists pointed to hidden bacterial infection as the etiology of chronic abacterial prostatitis [14]. This result demonstrates that Korean urologists regard bacterial infection as an important cause of CP. Psychological factors may also be important in the etiology of CP, and patients may benefit from psychotherapy and behavioral support [15]. In the Netherlands, about 40% of general practitioners and 65% of urologists envisaged a psychosomatic component to this syndrome [10]. Similarly, 40.8% of Chinese urologists considered psychosomatic factors as a cause of CP [12]. Established diagnostic tests for patients diagnosed with CP are typically unrewarding and successful therapeutic treatment is difficult [10]. This situation may lead to the belief of physicians that a psychosomatic component exists in many patients.

There is evidence to suggest that CP/CPPS is initiated by inflammation provoked by an initiator stimulus within the prostate gland, which in susceptible individuals results in peripheral nervous system sensitization in the prostate and surrounding areas [16]. This condition may result in neuropathic pain with allodynia and hyperalgesia and may explain the adequacy of treatments directed at prostatic inflammation in men with long-standing symptoms [17]. However, the initiator stimuli have not yet been precisely defined, and it is likely that more than one factor triggers CP/CPPS [16].

It has been proposed that intraprostatic reflux of urine (especially urate) results in chemical injury to the epithelium that initiates an immunologic reaction, a possible starting point for chronic inflammation [18,19]. Nevertheless, this hypothesis has not been followed up with conclusive studies and therapeutic achievements. In chronic fibromyalgia, extensive recent researches has provided evidence of a lowered pain threshold determined by the individua's genetic characteristics [20,21]. Those predisposed patients may have the condition 'triggered' by 'stressors' such as infection, physical trauma, or severe psychological trauma [21]. These abnormalities may be present at several levels of pain: processing systems as well as psychological pathways, both domains being influenced by specific genetic variants [22]. The possibility of impairment of anti-nociceptive pathways due to deficiencies in the serotonergic/noradrenergic pathways, such as those present in chronic fibromyalgia, is a consideration that warrants exploration, as it would have immediate therapeutic implications for successfully treating CP/CPPS [21]. The existence of an altered autonomic nervous system response in men with CP/CPPS has also recently been reported [23].

DIAGNOSIS

There is no gold standard for diagnostic testing for CP/CPPS [24]. A history of chronic pelvic pain in a man without documented infections supports the diagnosis of CP/CPPS. A history of recurrent or a recent urinary tract infection should raise suspicion for the existence of CBP. The evaluation of a patient presenting with symptoms of prostatitis must begin with a thorough medical history and physical examination. A complete inventory of other medical problems should be obtained to include any neurologic disorders.

1. Recommended evaluation

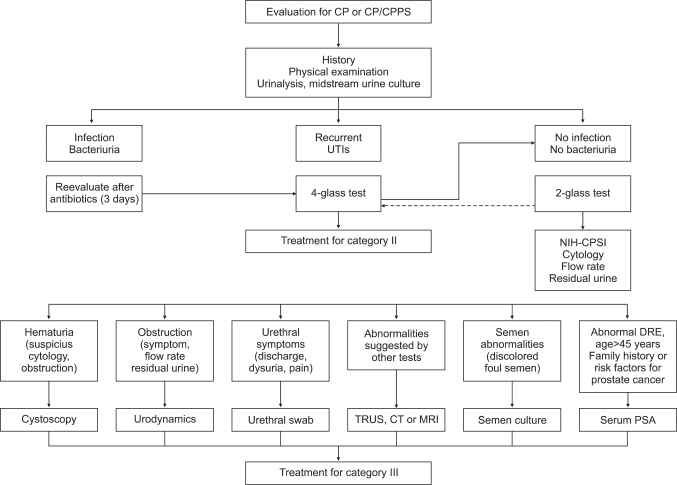

Standardized questionnaires may be useful in the evaluation of prostatitis and have been classified as recommended diagnostic tools. Many patients present a constellation of symptoms that may be difficult to assess objectively. Therefore, through literature review, peer groups, expert opinions, and patient testing, a symptom assessment questionnaire was developed by the NIH [25]. The NIH chronic prostatitis symptom index (NIH-CPSI) consists of nine parts that outline three major areas of prostatitis: pain, urinary symptoms, and quality of life [26]. Scores can be calculated on a summative scale or can be used independently to individually evaluate the three target areas. The symptom index is useful to longitudinally follow the patient in order to monitor changes in a standardized fashion [25]. However, this index has limitations in use as the sole diagnostic tool. Recent data have indicated that the NIH-CPSI is more useful in evaluating the severity of a patient's current symptoms after a diagnosis has been established than in assessing the presence or absence of prostatitis [27]. Nonetheless, the NIH-CPSI remains an important tool for clinicians and researchers. Depression and psychosocial symptoms are concentrated in patients with CP/CPPS and must be addressed in tandem with physical symptoms [28]. Thus, cooperation with a psychologist or a physician trained in psychosomatic medicine is helpful. Laboratory and simple office tests can provide useful information when evaluating the patient with symptoms of prostatitis. Several additional tests are recommended by the NIH consensus panel in the evaluation. A postvoid residual urine measurement provides useful information to determine whether a patient has incomplete bladder emptying. Urinary retention can be a causative factor in recurrent urinary tract infections and storage symptoms. Urine flow rates provide insight into a patient's overall voiding status. Low maximum flow rates suggest bladder outlet obstruction or decreased detrusor contractility. Urine cytology is a simple test that can provide insight into possible urothelial malignancy, which can cause irritative or obstructive voiding symptoms. Textbooks advise the use of the Meares-Stamey four-glass test, also known as a quantitative prostatic localization study. Because of the time-consuming technique of the four-glass test and the impossibility of establishing this technique in many andrology laboratories, Nickel et al. [29] conducted a study to evaluate a simpler screening test, the two-glass test. They compared it with the four-glass test for the initial evaluation of men with a clinical diagnosis of CP/CPPS. The two-glass test showed strong concordance with the four-glass test and is suggested to be a reasonable alternative when extraprostatic secretions are not obtained. The four-glass or two-glass test and the ejaculate test can be used to distinguish between inflammatory and noninflammatory forms of the condition [30]. Unfortunately, the results of the two- or four-glass tests are often neither diagnostic for prostatitis nor useful in directing treatments. Recent reports suggest that there may be little correlation between pyuria and symptom manifestations [31]. A diagnostic algorithm that provides a practical approach to the workup of the majority of men presenting with CP/CPPS is shown in Fig. 1.

FIG. 1.

A suggested diagnostic algorithm for the evaluation of patients presenting with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS). UTIs, urinary tract infections; TRUS, transrectal ultrasonography; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; DRE, digital rectal examination; PSA, prostate-specific antigen.

2. Optional evaluation

The complex conditions surrounding CP/CPPS often require multiple diagnostic studies to guide practitioners toward therapeutic options. A urethral swab can be performed for patients presenting with dysuria or localized pain to the urethra or penis or patients with a history of sexually transmitted diseases or unprotected intercourse [25]. Urodynamics offers valuable information on patients with predominantly voiding symptoms. It can be used to supplement the office evaluations of uroflow and postvoid residual urine. Urodynamics or videourodynamics help to detect any prostatic obstruction, primary bladder neck obstruction, and detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia. These conditions, which are accompanied by numerous effective treatment options as compared with prostatitis, may contribute to or cause the pelvic pain and lower urinary tract symptoms experienced by the patient [25]. In 1994, Kaplan et al. [32] reported a series of 34 patients with refractory CP who underwent urodynamic evaluation. Evidence of bladder outlet obstruction at the vesical neck was observed in 31 of the 34 patients, and all but one of these patients showed significant improvement of symptoms after transurethral incision of the bladder neck. Furthermore, in a second series, patients diagnosed with CP were found to have detrusor-sphincter dyssynergia [33]. Cystoscopy is also being used as an additional method of evaluation of CP/CPPS patients or as an adjunct to urodynamics. Cystoscopy should be performed in any patient with a history of hematuria or abnormal cytology. Patients with irritative or obstructive symptoms may warrant cystoscopy, because malignancy can act as a causative agent for that symptomatology [25].

3. Semen culture

The efficacy of semen culture in the diagnosis and evaluation of CBP remains unclear. A comprehensive survey described the study results of 40 men with CBP (NIH category II) due to Escherichia coli infection and their subsequent treatment by fluoroquinolone therapy [34]. In these patients, semen cultures demonstrated significant bacteriospermia (>103 ml-1) in 21 of 40 men before treatment. On the basis of this limited evidence, semen cultures were shown to identify significant bacteriospermia in only about 50% of semen specimens from men with CBP; therefore, ejaculate culture is not recommended as a first line of diagnostic evaluation in men with suspected CBP [35]. Further comparative investigations will be necessary to determine whether ejaculate analysis may provide useful diagnostic information for the diagnosis of CBP.

4. Transrectal ultrasound in CP/CPPS

Imaging studies using Doppler ultrasonography have shown CP/CPPS to be associated with significantly increased prostatic blood flow [36]. Transrectal ultrasound (TRUS) can also identify seminal vesicle or ejaculatory duct abnormalities. This imaging technique may be useful in evaluating patients with ejaculatory pain or hematospermia [27]. However, the clinical significance of this finding must be further evaluated before this method can be used as a diagnostic tool.

5. Serum prostate-specific antigen and CP/CPPS

In one study addressing this issue, a statistically significant elevation of serum prostate-specific antigen (s-PSA) was registered [37]. However, the increase was minute and s-PSA should not be interpreted to be a useful adjunct for diagnosis of CP/CPPS [38]. The flip side of this coin is that, if s-PSA is elevated in a man with CP/CPPS symptoms, the patient should be evaluated for prostate cancer and CBP [37].

6. Hypothetical heterogeneous clinical phenotypes in chronic prostatitis syndromes

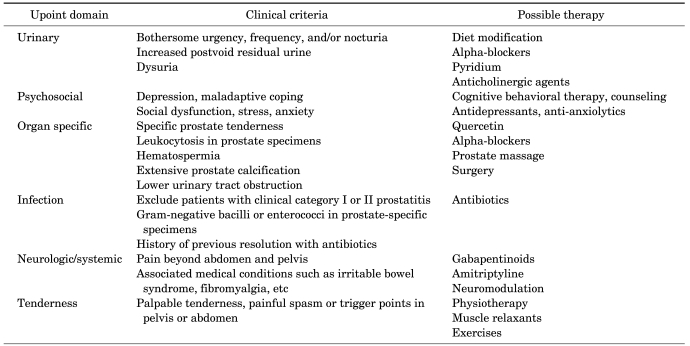

Patients with acute bacterial prostatitis are similar in both presentation of symptoms and response to therapy. In contrast, a single treatment fitting all patients diagnosed with CP does not succeed in clinical practice. It has become increasingly clear that patients with CBP and CPPS are not a homogeneous group with identical etiologic mechanisms, but rather are a heterogeneous group of individual patients with widely differing clinical symptoms including genitourinary pain, voiding symptoms, or psychosexual problems. Therefore, a single panacea to this challenging clinical entity will likely not be found soon. Rather, the challenge is to identify which subgroup of patients will respond best to a particular therapy. A clinically practical phenotyping classification system for patients diagnosed with urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes (UCPPS) has recently been proposed [39]. UPOINT is a six-point clinical classification system that categorizes the phenotype of patients with UCPPS (which includes the CPSs) into one or more of six clinically identifiable domains as follows: urinary, psychosocial, organ-specific, infection, neurologic/systemic, and tenderness (muscle). A physician can easily and quickly categorize patients into one or more UPOINT domains and propose an individually designed therapeutic plan that specifically addresses the clinical phenotypes identified. Most patients will be categorized with more than one UPOINT domain and will require multimodal therapy. This concept is outlined in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Upoint clinical phenotyping strategy for patients presenting with urologic chronic pelvic pain syndrome

TREATMENT

1. CBP

Fluoroquinolones penetrate relatively well into the prostate and are therefore the therapy of choice for CBP with a typical administration duration of 4 weeks. If the pathogen is resistant to fluoroquinolones, therapy with cotrimoxazole for 3 months is recommended [35]. For recurrent CBP, each episode can either be treated with antibiotics or long-term antibiotic prophylaxis can be administrated for a duration of at least 6 months. Surgical procedures such as transurethral resection of the prostate and radical prostatectomy are regarded as therapies of last resort or as therapies for concomitant obstruction [35,40].

2. Chronic pelvic pain syndrome

Because functional obstruction may cause CPPS, therapy using alpha-receptor blockers may be of significant benefit. The combination of an alpha-adrenergic blocker and antibiotic therapy was shown to be more efficacious than antibiotics alone [41]. Positive results from RCTs of alpha-blockers, e.g., terazosin [42], alfuzosin [43], doxazosin [44], and tamsulosin [45], have led to a widespread use of alpha-blocker in the treatment of CPPS over the past years. The effects of alpha-blocker may include improved outflow performance by blocking the alpha-receptors of the bladder neck and prostate and by direct action on alpha-1A/D-receptors in the CNS [36]. In contrast, a meta-analysis of nine trials (n=734) could not show beneficial effect on pain [46]. Moreover, a more recent adequately powered, large, placebo-controlled randomized trial of 12-week treatment with alfuzosin failed to show any significant difference in the outcome measures with the exception of the Male Sexual Health Questionnaire score [47]. Overall, the use of alpha-blockers for the treatment of CPPS can no more be recommended and should probably be restricted to patients with proven bladder outlet obstruction. Therefore, it is reasonable to use alpha-blockers for men with lower urinary tract symptoms as the predominant symptom complaint, especially in combination with antimicrobials. Muscle relaxants may be used if there is evidence of functional abnormalities in the pelvic floor muscle. Intraprostatic injection of botulinum toxin A is currently being investigated in these patients [48] and may offer a future therapeutic approach. Another pathogenetic hypothesis is that chronic bacterial infection is difficult to detect and cannot be cultured. For this reason, it is justifiable to treat CP/CPPS IIIa patients with fluoroquinolones if they have not been previously exposed to antibiotics, just as with CBP patients [35]. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) reduce prostaglandin synthesis by inhibiting the enzyme cyclooxygenase, leading to a favorable effect on prostatic inflammation [49]. For this reason, patients with dominantly pain-related symptoms may be given NSAIDs. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of pentosan polysulfate (Elmiron, Alza Pharmaceuticals, Mountain View, CA, USA) in the treatment of CPPS demonstrated a slightly greater improvement in symptoms over placebo after 16 weeks, but the difference was not statistically significant [50]. Some herbal medicines act in a similar manner and could possibly be used, although they have not yet been subjected to adequate clinical studies [35]. Analgesics with other modes of action (e.g., CNS) are indicated for intense pain. Anticholinergic drugs may be used for symptomatic treatment of patients with dominant micturition problems, including urinary urgency linked to irritable bladder. If a patient exhibits the symptoms of CP/CPPS, but without bacterial or inflammatory findings, the clinical picture is often classified as psychosomatic. The diagnosis of a somatoform disorder must be carefully considered in the context of other possible diagnoses and in close cooperation with a urologist. In such cases, it is particularly important to define accompanying depressive symptoms, and these must be diagnosed and treated separately from the actual prostatitis symptoms. Sexual dysfunction problems with a partner are frequently accompanied by significant consequences to the relationship [51]. Physical options include repetitive prostate massage or methods to apply energy to the prostate. There is inadequate evidence supporting the efficacy of these approaches and they remain controversial. If anatomical manifestations such as cysts in the prostate are observed, and these cause infravesical obstruction, surgical procedures should be performed to remove the obstruction.

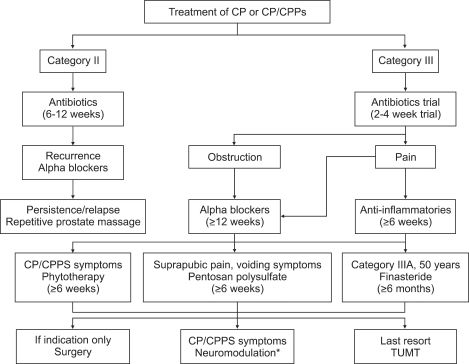

Neuromuscular and neuroleptic treatments have been observed to beneficially alter nervous system conditions found in chronic pain syndrome. Therefore, therapies designed to improve relaxation and encourage proper use of the pelvic floor muscle are expected to provide symptomatic improvement. Although no large, published clinical trials exist, preliminary evidence suggests potential efficacy in the use of biofeedback and bladder retraining in alleviating symptoms [52]. When trigger-point massage was combined with relaxation therapy in an uncontrolled study, 72% of patients reported improvement [53]. Amitriptyline can be effective for the treatment of pain from chronic muscle spasm and it has been found to be helpful in the management of CPPS [54]. A suggested treatment algorithm based on these assessments is presented in Fig. 2.

FIG. 2.

A suggested therapeutic algorithm for the treatment of patients presenting with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS). TUMT, transurethral microwave thermotherapy. *Amitriptyline, gabapentin, biofeedback, massage therapy, acupuncture, neurostimulation.

3. Discussion of novel treatment in category III prostatitis

Combination therapy has been suggested as a method to utilize synergism between classes of drugs and appears to be superior to monotherapy in the treatment of CP/CPPS [55,56]. A rational framework is required to guide this therapy. UPOINT can be used to classify patients with urologic chronic pelvic pain and subsequently direct appropriate therapy [57]. A recently completed, prospective study of 100 CP/CPPS patients treated with multimodal therapy offered specific therapies associated with each positive UPOINT domain (e.g., urinary, alpha-blocker or antimuscarinic; psychosocial, stress reduction/psychological support; organ-specific, quercetin; infection, antibiotic; neurologic/systemic, amitriptyline or pregabalin; tenderness, pelvic floor physical therapy) [58]. With a minimum follow-up duration of 6 months and an average follow-up of 50 weeks, 84 patients reached the primary endpoint of a six-point or greater improvement in total CPSI. Fifty-one patients had a 50% or greater improvement in total CPSI, whereas 84 patients demonstrated 25% or more improvement. All patients' CPSI subscores significantly improved from baseline. The improvement seen in all groups was not due to regression to the mean for the more symptomatic patients, because the number of UPOINT domains did not correlate with the drop in CPSI (Spearman r=0.034; p=0.74). There was no correlation between the drop in CPSI and the difference between the number of UPOINT domains and the number of therapies (p=0.63). Although this was not a placebo-controlled study, the incidence and magnitude of improvement was significantly higher than reported in prior large or multicenter studies of comparable duration.

CONCLUSIONS

CP remains a controversial condition with little agreement regarding the best treatment option. No formal evaluation standard exists, and clinicians should tailor diagnostic studies to a patient's specific symptoms and complaints while maintaining awareness that CP/CPPS remains a diagnosis of exclusion. The difficulty in finding efficacious treatment for any given patient likely lies in the heterogeneous nature of both the manifestation of causative conditions and the patient responses. The UPOINT system has attempted to help to define the different symptomatic domains in this difficult-to-treat condition, allowing physicians to target appropriate therapies and allowing researchers to narrow study populations in an attempt to discover a worthwhile treatment. It is important for the patient that he be informed as soon as possible about his condition, including the necessary diagnostic steps and possible therapies, and that a specific plan for his diagnosis and treatment be established. This is the best way to develop trust between doctor and patient. This trust is critically important because, for any given patient, it often happens that several unsuccessful attempts are made at treatment before an acceptable result is reached.

Footnotes

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Krieger JN, Riley DE, Cheah PY, Liong ML, Yuen KH. Epidemiology of prostatitis: new evidence for a world-wide problem. World J Urol. 2003;21:70–74. doi: 10.1007/s00345-003-0329-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoo YN. Prostatitis. Korean J Urol. 1994;35:575–585. [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNaughton Collins M, Pontari MA, O'Leary MP, Calhoun EA, Santanna J, Landis JR, et al. Quality of life is impaired in men with chronic prostatitis: the Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:656–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.01223.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nickel JC, Downey J, Hunter D, Clark J. Prevalence of prostatitis-like symptoms in a population based study using the National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index. J Urol. 2001;165:842–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nickel JC, Nigro M, Valiquette L, Anderson P, Patrick A, Mahoney J, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of prostatitis in Canada. Urology. 1998;52:797–802. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(98)00297-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kiyota H, Onodera S, Ohishi Y, Tsukamoto T, Matsumoto T. Questionnaire survey of Japanese urologists concerning the diagnosis and treatment of chronic prostatitis and chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Int J Urol. 2003;10:636–642. doi: 10.1046/j.1442-2042.2003.00720.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pontari MA, Joyce GF, Wise M, McNaughton-Collins M. Prostatitis. J Urol. 2007;177:2050–2057. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nickel JC, Olson ME, Costerton JW. Rat model of experimental bacterial prostatitis. Infection. 1991;19(Suppl 3):S126–S130. doi: 10.1007/BF01643681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schaeffer AJ, Landis JR, Knauss JS, Propert KJ, Alexander RB, Litwin MS, et al. Demographic and clinical characteristics of men with chronic prostatitis: the national institutes of health chronic prostatitis cohort study. J Urol. 2002;168:593–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de la Rosette JJ, Hubregtse MR, Karthaus HF, Debruyne FM. Results of a questionnaire among Dutch urologists and general practitioners concerning diagnostics and treatment of patients with prostatitis syndromes. Eur Urol. 1992;22:14–19. doi: 10.1159/000474715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moon TD. Questionnaire survey of urologists and primary care physicians' diagnostic and treatment practices for prostatitis. Urology. 1997;50:543–547. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00308-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang J, Liu L, Xie HW, Ginsberg DA. Chinese urologists' practice patterns of diagnosing and treating chronic prostatitis: a questionnaire survey. Urology. 2008;72:548–551. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krieger JN, Riley DE. Chronic prostatitis: Charlottesville to Seattle. J Urol. 2004;172:2557–2560. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000144291.05839.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ku JH, Paick JS, Kim SW. Chronic prostatitis in Korea: a nationwide postal survey of practicing urologists in 2004. Asian J Androl. 2005;7:427–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7262.2005.00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mehik A, Hellstrom P, Sarpola A, Lukkarinen O, Jarvelin MR. Fears, sexual disturbances and personality features in men with prostatitis: a population-based cross-sectional study in Finland. BJU Int. 2001;88:35–38. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2001.02259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nickel JC. The biomedical model has failed! So what is next. Contemp Urol. 2006;1:31–39. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang CC, Lee JC, Kromm BG, Ciol MA, Berger RE. Pain sensitization in male chronic pelvic pain syndrome: why are symptoms so difficult to treat? J Urol. 2003;170:823–826. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000082710.47402.03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kirby RS, Lowe D, Bultitude MI, Shuttleworth KE. Intra-prostatic urinary reflux: an aetiological factor in abacterial prostatitis. Br J Urol. 1982;54:729–731. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1982.tb13635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Persson BE, Ronquist G. Evidence for a mechanistic association between nonbacterial prostatitis and levels of urate and creatinine in expressed prostatic secretion. J Urol. 1996;155:958–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Staud R. Fibromyalgia pain: do we know the source? Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2004;16:157–163. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200403000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dadabhoy D, Clauw DJ. Fibromyalgia: progress in diagnosis and treatment. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2005;9:399–404. doi: 10.1007/s11916-005-0019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diatchenko L, Nackley AG, Slade GD, Fillingim RB, Maixner W. Idiopathic pain disorders--pathways of vulnerability. Pain. 2006;123:226–230. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yilmaz U, Liu YW, Berger RE, Yang CC. Autonomic nervous system changes in men with chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2007;177:2170–2174. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2007.01.144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McNaughton Collins M, MacDonald R, Wilt TJ. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic abacterial prostatitis: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:367–381. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-5-200009050-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nickel JC. Classification and diagnosis of prostatitis: a gold standard? Andrologia. 2003;35:160–167. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0272.2003.00557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Litwin MS, McNaughton-Collins M, Fowler FJ, Jr, Nickel JC, Calhoun EA, Pontari MA, et al. The National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index: development and validation of a new outcome measure. Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. J Urol. 1999;162:369–375. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(05)68562-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roberts RO, Jacobson DJ, Girman CJ, Rhodes T, Lieber MM, Jacobsen SJ. Low agreement between previous physician diagnosed prostatitis and national institutes of health chronic prostatitis symptom index pain measures. J Urol. 2004;171:279–283. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000100088.70887.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneider H, Wilbrandt K, Ludwig M, Beutel M, Weidner W. Prostate-related pain in patients with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. BJU Int. 2005;95:238–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nickel JC, Shoskes D, Wang Y, Alexander RB, Fowler JE, Jr, Zeitlin S, et al. How does the pre-massage and post-massage 2-glass test compare to the Meares-Stamey 4-glass test in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome? J Urol. 2006;176:119–124. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(06)00498-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weidner W, Anderson RU. Evaluation of acute and chronic bacterial prostatitis and diagnostic management of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome with special reference to infection/inflammation. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31(Suppl 1):S91–S95. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2007.07.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schaeffer AJ, Knauss JS, Landis JR, Propert KJ, Alexander RB, Litwin MS, et al. Leukocyte and bacterial counts do not correlate with severity of symptoms in men with chronic prostatitis: the National Institutes of Health Chronic Prostatitis Cohort Study. J Urol. 2002;168:1048–1053. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)64572-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaplan SA, Te AE, Jacobs BZ. Urodynamic evidence of vesical neck obstruction in men with misdiagnosed chronic nonbacterial prostatitis and the therapeutic role of endoscopic incision of the bladder neck. J Urol. 1994;152:2063–2065. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)32309-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaplan SA, Santarosa RP, D'Alisera PM, Fay BJ, Ikeguchi EF, Hendricks J, et al. Pseudodyssynergia (contraction of the external sphincter during voiding) misdiagnosed as chronic nonbacterial prostatitis and the role of biofeedback as a therapeutic option. J Urol. 1997;157:2234–2237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weidner W, Ludwig M, Brahler E, Schiefer HG. Outcome of antibiotic therapy with ciprofloxacin in chronic bacterial prostatitis. Drugs. 1999;58(Suppl 2):103–106. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199958002-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schaeffer AJ, Anderson RU, Krieger JN, Lobel B, Naber K, Nakagawa M. The assessment and management of male pelvic pain syndrome including prostatitis. In: McConnel J, Abrams P, Denis L, editors. Male lower urinary tract dysfunction evaluation and management; 6th International Consultation on New Developments in Prostate Cancer and Prostate Diseases. Paris: Health Publications; 2006. pp. 341–385. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cho IR, Keener TS, Nghiem HV, Winter T, Krieger JN. Prostate blood flow characteristics in the chronic prostatitis/pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2000;163:1130–1133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nadler RB, Collins MM, Propert KJ, Mikolajczyk SD, Knauss JS, Landis JR, et al. Prostate-specific antigen test in diagnostic evaluation of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology. 2006;67:337–342. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pavone-Macaluso M. Chronic prostatitis syndrome: a common, but poorly understood condition. Part I. EAU-EBU Update Series. 2007;5:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shoskes DA, Nickel JC, Dolinga R, Prots D. Clinical phenotyping of patients with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and correlation with symptom severity. Urology. 2009;73:538–542. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.09.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Frazier HA, Spalding TH, Paulson DF. Total prostatoseminal vesiculectomy in the treatment of debilitating perineal pain. J Urol. 1992;148:409–411. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)36615-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mo KI, Lee KS, Kim DG. Efficacy of combination therapy for patients with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a prospective study. Korean J Urol. 2006;47:536–540. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheah PY, Liong ML, Yuen KH, Teh CL, Khor T, Yang JR, et al. Terazosin therapy for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a randomized, placebo controlled trial. J Urol. 2003;169:592–596. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000042927.45683.6c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mehik A, Alas P, Nickel JC, Sarpola A, Helstrom PJ. Alfuzosin treatment for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot study. Urology. 2003;62:425–429. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(03)00466-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Evliyaoglu Y, Burgut R. Lower urinary tract symptoms, pain and quality of life assessment in chronic non-bacterial prostatitis patients treated with alpha-blocking agent doxazosin; versus placebo. Int Urol Nephrol. 2002;34:351–356. doi: 10.1023/a:1024487604631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nickel JC, Narayan P, McKay J, Doyle C. Treatment of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome with tamsulosin: a randomized double blind trial. J Urol. 2004;171:1594–1597. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000117811.40279.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang G, Wei Q, Li H, Yang Y, Zhang S, Dong Q. The effect of alpha-adrenergic antagonists in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Androl. 2006;27:847–852. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.106.000661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nickel JC, Krieger JN, McNaughton-Collins M, Anderson RU, Pontari M, Shoskes DA, et al. Alfuzosin and symptoms of chronic prostatitis-chronic pelvic pain syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2663–2673. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0803240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chuang YC, Yoshimura N, Wu M, Huang CC, Chiang PH, Tyagi P, et al. Intraprostatic capsaicin injection as a novel model for nonbacterial prostatitis and effects of botulinum toxin A. Eur Urol. 2007;51:1119–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.11.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bach D, Walker H. How important are prostaglandins in the urology of man? Urol Int. 1982;37:160–171. doi: 10.1159/000280813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nickel JC, Forrest JB, Tomera K, Hernandez-Graulau J, Moon TD, Schaeffer AJ, et al. Pentosan polysulfate sodium therapy for men with chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a multicenter, randomized, placebo controlled study. J Urol. 2005;173:1252–1255. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000159198.83103.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith KB, Tripp D, Pukall C, Nickel JC. Predictors of sexual and relationship functioning in couples with Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Sex Med. 2007;4:734–744. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cornel EB, van Haarst EP, Schaarsberg RW, Geels J. The effect of biofeedback physical therapy in men with chronic pelvic pain syndrome type III. Eur Urol. 2005;47:607–611. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2004.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anderson RU, Wise D, Sawyer T, Chan C. Integration of myofascial trigger point release and paradoxical relaxation training treatment of chronic pelvic pain in men. J Urol. 2005;174:155–160. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000161609.31185.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Holroyd KA, O'Donnell FJ, Stensland M, Lipchik GL, Cordingley GE, Carlson BW. Management of chronic tension-type headache with tricyclic antidepressant medication, stress management therapy, and their combination: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;285:2208–2215. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.17.2208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shoskes DA, Hakim L, Ghoniem G, Jackson CL. Long-term results of multimodal therapy for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2003;169:1406–1410. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000055549.95490.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tugcu V, Tasci AI, Fazlioglu A, Gurbuz G, Ozbek E, Sahin S, et al. A placebo-controlled comparison of the efficiency of triple- and monotherapy in category III B chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS) Eur Urol. 2007;51:1113–1117. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2006.09.036. discussion 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shoskes DA, Nickel JC, Rackley RR, Pontari MA. Clinical phenotyping in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and interstitial cystitis: a management strategy for urologic chronic pelvic pain syndromes. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2009;12:177–183. doi: 10.1038/pcan.2008.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shoskes DA, Nickel JC, Kattan MW. Phenotypically directed multimodal therapy for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a prospective study using UPOINT. Urology. 2010;75:1249–1253. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2010.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]