Abstract

Objective

To analyze the association of hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) at gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) diagnosis with postpartum abnormal glucose in a cohort of women with GDM.

Methods

Women with singleton pregnancies managed for GDM at a large diabetes and pregnancy program located in Charlotte, North Carolina who completed a postpartum 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test were eligible for inclusion in this retrospective cohort study. Clinical information, including maternal HbA1c at diagnosis was abstracted from medical records. A parametric survival model was used to assess the association of HbA1c at GDM diagnosis with postpartum maternal abnormal glucose including impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, and any postpartum abnormal glucose.

Results

Of the 277 postpartum women with GDM 75 (32%) had impaired fasting glucose, 61 (28%) had impaired glucose tolerance, and 15 (9%) were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes after delivery. After adjustment for clinic, maternal age, parity, prepregnancy BMI 25 kg/m2 or higher, non-white race or ethnicity, and gestational week at first HbA1c we detected a trend of increased risk for impaired fasting glucose (p=0.01), impaired glucose tolerance (p=0.002), and any glucose abnormality (p <0.001) associated with increased quartile of HbA1c at GDM diagnosis.

Conclusion

HbA1c measured at GDM diagnosis may be a useful tool for identifying GDM patients at highest risk of developing postpartum abnormal glucose.

Introduction

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) occurs in 1–14% of pregnancies in the United States.(1) Up to 60% of women with a history of GDM will develop type 2 diabetes within 5–10 years postpartum.(2) Identifying women, with GDM, at the highest risk of progressing to type 2 diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, or impaired glucose tolerance, and providing them with appropriate tools for healthy lifestyle changes can reduce incidence of type 2 diabetes.(3)

Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), a hemoglobin variant, is an accepted and standardized measure of glycemic control. Compared with plasma glucose, HbA1c has less intra-individual variability,(4) is easily measured with a single blood test, and does not require fasting, consumption of a concentrated glucose beverage, or multiple blood draws. Reasons for reluctance in adopting HbA1c during pregnancy as a measure of maternal glycemic control include the scarcity of published reports that account for the effect of pregnancy-associated metabolic and hematologic changes on the interpretation of HbA1c values in pregnant patients.(5, 6)

Previously, some studies of women with GDM reported that higher HbA1c is associated with postpartum type 2 diabetes, impaired fasting glucose, or impaired glucose tolerance,(7–10) but at least one study did not find such an association.(11) We conducted a retrospective cohort study of GDM patients to determine the extent to which, if at all, higher HbA1c values, determined at the time of GDM diagnosis, are associated with an increased risk of postpartum impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, or any glucose abnormality, including type 2 diabetes.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted in a large diabetes and pregnancy program located in Charlotte, NC, which is a consortium of two clinics. Clinic A, housed within the main medical center, provides comprehensive education and care for women with type 1 diabetes mellitus, type 2 diabetes, and GDM and serves a primarily white, privately insured population. Clinic B provides obstetric care for women with and without diabetes in pregnancy. The majority of patients at Clinic B are racial or ethnic minorities and are enrolled in Medicaid or lack insurance. These two clinics, located within a mile of each other, use a common GDM clinical management protocol developed by the Medical Director, a Board Certified Endocrinologist (E.M.). The program serves all of Mecklenburg County, and the nine surrounding counties.

Typically women are referred to one of the two diabetes and pregnancy program clinics at 24–28 weeks gestation following a positive 50 g oral glucose challenge and a positive 3 hour 100 g oral glucose tolerance test.(12) HbA1c and other laboratory tests are performed at or near the first appointment at clinic A and at or near the time of GDM diagnosis at clinic B. At both clinics women considered at particularly high risk for GDM may be referred earlier in their pregnancy with or without GDM screening. Additionally, women may be diagnosed with GDM and referred to the diabetes and pregnancy program at any point in their pregnancy following an extremely elevated glucose challenge test or random blood glucose. Women are encouraged to undergo a postpartum 2 hour 75 g oral glucose tolerance test approximately six weeks after delivery in keeping with guidelines published by multiple organizations.(1, 13) Orders for the postpartum oral glucose tolerance test are usually written at the patient’s final antepartum visit to the diabetes and pregnancy program or while hospitalized in the immediate postpartum period.

Women managed for GDM who delivered a live singleton infant between November 15, 2000 and April 15, 2010 were eligible for inclusion in the study. Additional inclusion criteria were: diagnosed with GDM at ≥24 weeks gestation by either a 3 hour 100 g oral glucose tolerance test, a glucose challenge test ≥200 mg/dl, or a random blood glucose ≥160 mg/dl; and completion of a postpartum 2 h 75 g oral glucose tolerance test. Study exclusion criteria were: established type 1 or type 2 diabetes; GDM diagnosis at <24 weeks gestation; untreated endocrinopathies (hyperadrenalism, hypoadrenalism, hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, and acromegaly); hemoglobin variants (HbS, HbC, HbF, and HbE) or conditions (uremia, thalassemia) that impair interpretation of HbA1c; first HbA1c measurement >4 weeks after initial visit to the diabetes and pregnancy program; use of medications at time of postpartum oral glucose tolerance test that affect glucose tolerance (metformin, glyburide, steroids, hydrochlorothiazide); and pregnant at time of the postpartum oral glucose tolerance test. The institutional review boards of the University of Washington and Carolinas HealthCare System approved the protocol for this study.

The clinics measured HbA1c and plasma glucose, the laboratory measures for this study using different methods. Using point-of-care instruments, Clinic A measured HbA1c with a DCA 2000, and measured whole blood glucose with a HemoCueB-Glucose Analyzer. All glucose values measured by the HemoCueB-Glucose Analyzer were converted from whole blood to plasma glucose prior to glucose status determination. The HemoCueB-Glucose Analyzer is highly accurate with a Pearson correlation of 0.98 to standard laboratory measures(14) and is considered appropriate for diagnosis of diabetes in epidemiologic studies.(15, 16) Clinic B sends all samples to the main laboratory for analysis; at the main laboratory HbA1c was measured via high-performance liquid chromatography using a Diabetes Complications and Control Trial aligned method (Bio-Rad VARIANT™II TURBO), and plasma glucose was measured via an oxygen rate method using the SYNCHRON® System. The laboratory method and point of care method for HbA1c measurement are highly correlated with a reported Pearson correlation of >0.9 and the DCA 2000 has been certified by the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization program to conform to the results of the Diabetes Complications and Control Trial.(17–20)

The primary exposure was the first HbA1c, measured and recorded at one of the two diabetes and pregnancy program clinics, within four weeks of GDM diagnosis. Key covariates included variables related to maternal demographics; medical and obstetric history; and pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum characteristics. Demographic variables included: clinic (Clinic A, Clinic B), maternal age at GDM diagnosis, parity (parous, nulliparous), insurance (private insurance; self-pay or Medicaid), maternal race/ethnicity (white, non-white race/ethnicity), and pre-pregnancy overweight or obesity based on body mass index (BMI) as calculated from height, measured by clinic staff, and patient reported pre-pregnancy weight (BMI<25 kg/m2, BMI ≥25 kg/m2).(21, 22) Medical and obstetric history variables included: prior history of GDM, prior history of preeclampsia/eclampsia, history of polycystic ovarian syndrome, history of spontaneous abortion, and history of intra-uterine fetal demise. Pregnancy, delivery and postpartum variables included: gestational week at first HbA1c as recorded on the medical chart based either on ultrasound or on last menstrual period, method of GDM diagnosis (oral glucose tolerance test, glucose challenge test ≥ 200 mg/dl or random blood glucose ≥ 160 mg/dl), treatment for management of GDM (diet only; insulin, glyburide, insulin, metformin, or combination), gestational week at delivery (calculated from date of delivery, gestational week at last clinic visit, and date of last clinic visit), preterm delivery (delivery at <37 weeks gestation), and breastfeeding (yes, no).

The primary outcomes were postpartum impaired fasting glucose (with or without impaired glucose tolerance), impaired glucose tolerance (with or without impaired fasting glucose), and any postpartum abnormal glucose, including type 2 diabetes, as diagnosed by a 2 hour 75 g oral glucose tolerance test according to the 1997 ADA criteria.(12) Women were considered to have normal glucose if fasting plasma glucose was <100 mg/dl and two hour plasma glucose was 140 mg/dl. Women with fasting plasma glucose ≥100 mg/dl and <126 mg/dl were categorized as impaired fasting glucose and women with two hour plasma glucose ≥140 mg/dl and <200 mg/dl were categorized as impaired glucose tolerance. Women with fasting plasma glucose ≥126 mg/dl or two hour plasma glucose ≥200 mg/dl were categorized as type 2 diabetes.

A parametric survival-time model(23) with an exponential distribution and robust standard errors was used to analyze the association between increasing HbA1c quartile and risk of postpartum abnormal glucose The exponential distribution assumes a constant hazard over time. All analyses were completed using STATA 9 software,(24) and a user defined module for interval censored data that fits distributions to data by maximum likelihood.(23) The time scale was weeks since delivery. All women had a start time of date of delivery. Women who did not have impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes at time of postpartum testing were censored at the time of their postpartum oral glucose tolerance test. Women with impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, or type 2 diabetes at the time of the postpartum oral glucose tolerance test could have developed abnormal glucose tolerance at any time between delivery and postpartum oral glucose tolerance test and therefore their time to event was left-censored and fell between the date of delivery and postpartum oral glucose tolerance test.

Women were grouped according to HbA1c quartiles based on the distribution of HbA1c among all eligible women regardless of whether or not they completed of a postpartum oral glucose tolerance test. The outcomes of impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, and any postpartum abnormal glucose were examined separately and as a combined outcome of any postpartum abnormal glucose. The primary measure was a test for trend(25) in risk of postpartum abnormal glucose across increasing quartiles of HbA1c, which was conducted by assigning HbA1c quartiles values in ascending order from 1–4 and entering HbA1c quartile into the regression model as a continuous variable.(25, 26) Potential confounders were retained in the final model if their inclusion resulted in a >10% change in estimateor if they were a priori considered important. Adjusted and unadjusted hazard ratios are reported along with their 95% confidence intervals and statistical significance was defined at the two-sided alpha level of 0.05.

To test if the association of HbA1c and postpartum impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, or any abnormal glucose differed by GDM treatment modality, method of GDM diagnosis, or race/ethnicity, interaction terms were introduced between these variables and quartile of HbA1c. The statistical significance of the interaction terms was assessed using the Wald test (z=est/se).(26)

Results

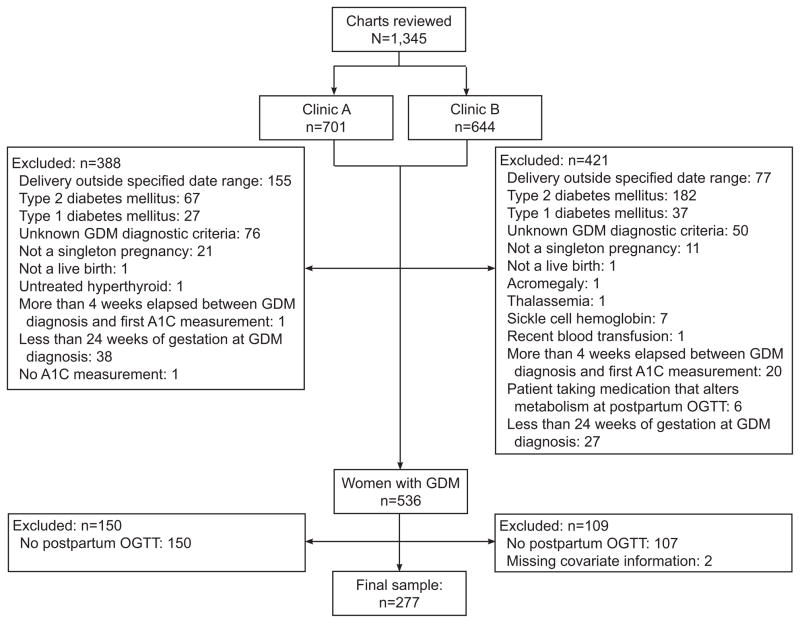

We reviewed 1,345 charts (Clinic A n=701; Clinic B n=644) and 536 (40%) met our eligibility criteria (Figure 1). Among eligible women 277 (Clinic A n=163; Clinic B n=114) completed a postpartum oral glucose tolerance test following delivery (median: 7.9 weeks, IQR: 6.6–9.4, range: 3–111). Compared with women who did not complete a postpartum oral glucose tolerance test, women who completed a postpartum oral glucose tolerance test were more likely to have required insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents, but the two groups did not differ on any other demographic or clinical characteristics. Two women completed a postpartum oral glucose tolerance test, but were missing information on pre-pregnancy BMI and were excluded from the analysis. The overall prevalence of any postpartum glucose abnormality was 42%: 42 (15%) women had isolated impaired fasting glucose, 28 (10%) had isolated impaired glucose tolerance, 33 (12%) had combined impaired fasting glucose/impaired glucose tolerance, and 15 (5%) had type 2 diabetes.

Figure 1.

Exclusions based on maternal and pregnancy characteristics. GDM, gestational diabetes; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

Demographic; medical and obstetric history; and pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum characteristics of the study population are described in Table 1. The majority of study participants were privately insured, of non-white race/ethnicity, and overweight or obese (BMI ≥25 kg/m2). The mean gestational age at first HbA1c was 30 weeks (stdev: 2.4) and 74% were diagnosed by a 3 hour oral glucose tolerance test. Compared with women managed at Clinic A, those managed at Clinic B were less likely to be nulliparous, or have private insurance; but more likely to be of non-white race/ethnicity, to be overweight or obese, to have a prior history of GDM or pre-eclampsia, have higher HbA1c at GDM diagnosis, and to require insulin or oral hypoglycemics. Similarly, compared with women in the first HbA1c quartile those in the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th quartile were less likely to be nulliparous; and more likely to be of non-white race/ethnicity, to be overweight or obese, and to require insulin or oral hypoglycemics.

Table 1.

Demographic, Medical and Obstetric History, and Pregnancy, Delivery, and Postpartum Characteristics of the Study Population by Clinic and by Hemoglobin A1c Quartile at Gestational Diabetes Mellitus Diagnosis

| Total | Clinic

|

HbA1c Quartile at GDM Diagnosis (range)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinic A | Clinic B | 1st (4.1–5.3) | 2nd (5.4–5.6) | 3rd (5.7–6.1) | 4th (6.2–10.9) | ||

| N | 277 | 163 | 114 | 91 | 59 | 71 | 56 |

| Demographic characteristics | |||||||

| Mean maternal age at GDM diagnosis (yrs) (SD) | 31 (5.2) | 32 (4.6) | 30 (5.7) | 31 (4.5) | 32 (5.1) | 32 (5.8) | 30 (5.6) |

| Maternal age at GDM diagnosis (yrs) n (%) | |||||||

| <25 | 28 (10) | 8 (5) | 20 (17) | 6 (7) | 4 (7) | 9 (13) | 9 (16) |

| 25–29.9 | 72 (26) | 45 (28) | 27 (24) | 28 (31) | 16 (27) | 14 (20) | 14 (25) |

| 30–34.9 | 98 (35) | 54 (33) | 44 (39) | 34 (37) | 19 (32) | 27 (38) | 18 (32) |

| >35 | 79 (29) | 56 (34) | 23 (20) | 23 (25) | 20 (34) | 21 (29) | 15 (27) |

| Nulliparous n (%) | 121 (44) | 87 (53) | 34 (30) | 46 (51) | 26 (41) | 27 (38) | 24 (43) |

| Medicaid or uninsured n (%) | 113 (41) | 5 (3) | 108 (95) | 19 (21) | 17 (29) | 40 (56) | 37 (66) |

| Race/ethnicity n (%) | |||||||

| White | 104 (38) | 97 (60) | 7 (6) | 58 (64) | 25 (42) | 12 (17) | 9 (16) |

| African-American | 51 (18) | 29 (18) | 22 (19) | 9 (10) | 6 (10) | 21 (30) | 15 (27) |

| Hispanic | 88 (32) | 7 (4) | 81 (71) | 17 (19) | 16 (27) | 28 (39) | 27 (48) |

| Asian Indian | 27 (10) | 26 (16) | 1 (1) | 4 (4) | 11 (19) | 7 (10) | 5 (9) |

| Other | 7 (2) | 4 (2) | 3 (3) | 3 (3) | 1 (2) | 3 (4) | 0 |

| Prepregnancy BMI n (%) | |||||||

| Less than 25 kg/m2 | 91 (33) | 70 (43) | 21 (18) | 47 (52) | 23 (39) | 14 (20) | 7 (12) |

| 25–29.9 kg/m2 | 84 (30) | 41 (25) | 43 (38) | 23 (25) | 24 (41) | 21 (29) | 16 (29) |

| 30 kg/m2 or higher | 102 (37) | 52 (32) | 50 (44) | 21 (23) | 12 (20) | 36 (51) | 33 (59) |

| Medical and obstetric history | |||||||

| Prior GDM n (%) | 33 (12) | 13 (8) | 20 (18) | 9 (10) | 10 (17) | 3 (4) | 11 (20) |

| Prior preeclampsia or eclampsia n (%) | 17 (6) | 7 (4) | 10 (9) | 5 (6) | 3 (5) | 7 (10) | 2 (4) |

| Polycystic ovarian syndrome n (%) | 8 (3) | 7 (4) | 1 (1) | 4 (4) | 1 (2) | 1 (1) | 2 (4) |

| Spontaneous abortion n (%) | 51 (18) | 29 (18) | 22 (19) | 16 (18) | 14 (24) | 15 (21) | 6 (11) |

| Intrauterine fetal demise n (%) | 6 (2) | 2 (1) | 4 (4) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 3 (4) | 1 (2) |

| Pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum | |||||||

| Mean gestational week at first HbA1c (SD) | 30 (2.4) | 30 (1.7) | 31 (3.0) | 30 (2.1) | 31 (2.4) | 30 (2.0) | 30 (3.1) |

| Method of GDM diagnosis n (%) | |||||||

| 3-hour oral glucose tolerance test | 205 (74) | 129 (79) | 76 (67) | 77 (85) | 50 (85) | 53 (75) | 25 (45) |

| Glucose challenge test | 58 (21) | 31 (19) | 27 (24) | 13 (14) | 7 (12) | 17 (24) | 21 (37) |

| Random blood glucose | 14 (5) | 3 (2) | 11 (9) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 1 (1) | 10 (18) |

| HbA1c quartile at GDM diagnosis n (%) | |||||||

| 1st (4.1–5.3) | 91 (33) | 73 (45) | 18 (15) | 91 (100) | |||

| 2nd (5.4–5.6) | 59 (21) | 40 (24) | 19 (17) | 59 (100) | |||

| 3rd (5.7–6.1) | 71 (26) | 34 (21) | 37 (33) | 71 (100) | |||

| 4th (6.2–10.9) | 56 (20) | 16 (10) | 40 (35) | 56 (100) | |||

| Management of GDM n (%) | |||||||

| Diet only | 56 (20) | 47 (29) | 9 (8) | 36 (40) | 10 (17) | 8 (11) | 2 (4) |

| Glyburide | 46 (17) | 4 (2) | 42 (37) | 10 (11) | 13 (22) | 14 (20) | 9 (16) |

| Insulin | 162 (58) | 11 (68) | 51 (45) | 43 (47) | 34 (58) | 46 (65) | 39 (69) |

| Metformin | 3 (1) | 0 | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 0 | 0 | 2 (4) |

| Other | 10 (4) | 1 (1) | 9 (8) | 1 (1) | 2 (3) | 3 (4) | 4 (7) |

| Median gestational week at delivery (IQR) | 39 (38–40) | 39 (39–40) | 39 (38–39) | 39 (39–40) | 39 (38–40) | 39 (38–39) | 39 (38–39) |

| Preterm delivery (before 37 weeks or gestation) n (%) | 20 (7) | 9 (6) | 11 (10) | 6 (7) | 4 (7) | 8 (11) | 2 (4) |

| Breastfeeding n (%) | 188 (72) | 115 (71) | 73 (74) | 69 (80) | 41 (72) | 47 (71) | 31 (61) |

Hb, hemoglobin; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range.

As indicated in Table 2 the median time from delivery to postpartum oral glucose tolerance test was 7–8 weeks in all HbA1c quartiles. One woman who was included in the primary analysis had a postpartum OGTT 111 weeks after delivery, excluding her in a subsequent sensitivity analysis did not substantially change our results. Mean fasting plasma glucose increased from 93 mg/dl in the 1st HbA1c quartile to 103 mg/dl in the 4th HbA1c quartile. Mean 2 hour plasma glucose increased from 119 mg/dl in the 1st HbA1c quartile to 145 mg/dl in the 4th HbA1c quartile.

Table 2.

Median Time Since Delivery, Mean Postpartum Glucose Values,* and Postpartum Glucose Status by Hemoglobin A1c Quartile at Gestaional Diabetes Mellitus Diagnosis (n=277)

| Total | HbA1c Quartile

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st (4.1–5.3) | 2nd (5.4–5.6) | 3rd (5.7–6.1) | 4th (6.2–10.9) | ||

| N | 277 | 91 | 59 | 71 | 56 |

| Median time since delivery (weeks) (IQR)* | 7.9 (6.6–9.4) | 8.4 (7.1–10.0)* | 7.9 (6.4–10.6) | 7.1 (6.3–8.1) | 7.9 (6.4–9.2) |

| Time since delivery (min-max) | (3–111) | (4–111) | (3–35) | (3–23) | (3–34) |

| Mean 75 g 2-hour oral glucose tolerance test values (mg/dl) (SD) | |||||

| Fasting | 96 (22.1) | 93 (10.0) | 96 (12.1) | 95 (12.7) | 103 (43.6) |

| 2 hour | 129 (40.6) | 119 (28.2) | 128 (39.0) | 130 (32.0) | 145 (60.5) |

| Postpartum glucose status n (%) | |||||

| Impaired fasting glucose (isolated or with impaired glucose tolerance)† | 75 (32) | 20 (24) | 21 (39) | 19 (33) | 15 (37) |

| Impaired glucose tolerance (isolated or with impaired fasting glucose)‡ | 61 (28) | 14 (18) | 13 (28) | 21 (36) | 13 (33) |

| Type 2 diabetes§ | 15 (9) | 1 (2) | 3 (8) | 2 (5) | 9 (26) |

| Impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, or type 2 diabetes | 118 (42) | 29 (32) | 26 (44) | 33 (47) | 30 (54) |

HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c, IQR, interquartile range

One woman completed the postpartum oral glucose tolerance test 111 weeks after delivery, and all other women completed the postpartum oral glucose tolerance test within a year of delivery

Percentages exclude those with isolated impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes (n=43)

Percentage exclude those with isolated impaired fasting glucose or type 2 diabetes (n=57)

Percentages exclude those with impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance (n=103)

After adjustment for clinic, maternal age, parity, pre-pregnancy BMI ≥25 kg/m2, non-white race/ethnicity, and gestational week at first HbA1c higher HbA1c quartile at GDM diagnosis was associated with an increased risk for impaired fasting glucose (p for trend=0.01), impaired glucose tolerance (p for trend 0.002), and any glucose abnormality (impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, or type 2 diabetes) (p for trend <0.001) (Table 3). Compared with women in the 1st HbA1c quartile women in the 2nd quartile had an 1.90 times higher risk for impaired fasting glucose (95% CI 0.99, 3.67), those in the 3rd quartile had a 1.96 times higher risk for impaired fasting glucose (95% CI 0.90, 4.27), and those in the 4th quartile had 2.96 times higher risk for impaired fasting glucose (95% CI 1.35, 6.46). Compared with women in the first HbA1c quartile women in the 2nd quartile had a 1.73 times higher risk for impaired glucose tolerance (95% CI 0.78, 3.85), those in the 3rd quartile had a 2.68 times higher risk of impaired glucose tolerance (95% CI 1.09, 6.60), and those in the 4th quartile 4.05 times higher risk for impaired glucose tolerance (95% CI 1.66, 9.89). Finally, compared with women in the first HbA1c quartile women in the 2nd quartile had a 1.68 times higher risk for any glucose abnormality (95% CI 0.94, 2.98), those in the 3rd quartile had a 2.29 times higher risk for any glucose abnormality (95% CI 1.22, 4.32), and those in the 4th quartile had a 3.75 times higher risk for any glucose abnormality (95% CI 1.99, 7.07). No statistically significant interactions were detected between HbA1c quartile and GDM diagnostic method, treatment modality, or non-white race/ethnicity.

Table 3.

Hazard Ratios for the Association of Hemoglobin A1c at Gestational Diabetes Mellitus (GDM) Diagnosis and Abnormal Postpartum Glucose Among Women With GDM (N=277)

| HbA1c Quartile | n | n (%)* | HRcrude (95% CI) | P† | HRadj‡ (95% CI) | P† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impaired fasting glucose§ | 1st | 82 | 20 (24) | reference | 0.10 | reference | 0.01 |

| 2nd | 54 | 21 (39) | 2.05 (1.11, 3.77) | 1.90 (0.99, 3.67) | |||

| 3rd | 57 | 19 (33) | 1.69 (0.89, 3.22) | 1.96 (0.90, 4.27) | |||

| 4th | 41 | 15 (37) | 1.76 (0.86, 3.59) | 2.96 (1.35, 6.46) | |||

| Impaired glucose tolerance|| | 1st | 76 | 14 (18) | reference | 0.03 | reference | 0.002 |

| 2nd | 46 | 13 (28) | 1.79 (0.85, 3.78) | 1.73 (0.78, 3.85) | |||

| 3rd | 59 | 21 (36) | 2.43 (1.21, 4.89) | 2.68 (1.09, 6.60) | |||

| 4th | 39 | 13 (33) | 1.98 (0.90, 4.33) | 4.05 (1.66, 9.89) | |||

| Impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, type 2 diabetes | 1st | 91 | 29 (32) | reference | 0.01 | reference | <0.001 |

| 2nd | 59 | 26 (44) | 1.70 (1.00, 2.89) | 1.68 (0.94, 2.98) | |||

| 3rd | 71 | 33 (47) | 1.91 (1.13, 3.22) | 2.29 (1.22, 4.32) | |||

| 4th | 56 | 30 (54) | 2.08 (1.20, 3.62) | 3.75 (1.99, 7.07) |

HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HR, hazard ratio;

n (%) percent with outcome

p for trend

Adjusted for: clinic, maternal age at GDM diagnosis (yrs), parity (0, ≥1), non-white race/ethnicity, BMI ≥25 kg/m2, and gestational week at first HbA1c

analysis excluded those with isolated impaired glucose tolerance or type 2 diabetes (n=43)

analysis excluded those with isolated impaired fasting glucose or type 2 diabetes (n=57)

Although, we did not detect a statistically significant interaction between HbA1c ≥5.3% and treatment modality (p=0.35) the estimates began to diverge when stratifying by treatment (insulin or oral hypoglycemics: HR 2.12, 95% CI 1.16, 3.87; diet only: HR 1.08, 95% CI 0.33, 3.54). There was little evidence of heterogeneity of the association of HbA1c and postpartum abnormal glucose when stratifying by clinic and using a continuous measure of HbA1c (Clinic A: HR 1.87, 95% CI 1.11, 3.16; Clinic B: HR 2.67, 95% CI 1.48, 4.82).

Discussion

This study found that higher HbA1c at GDM diagnosis is associated with increased risk of abnormal postpartum glucose. The overall prevalence of abnormal postpartum glucose is 42% in our study population. After adjustment women in the highest HbA1c quartile (>6.1) compared with those in the lowest quartile (<5.3) had a nearly 4-fold higher risk of any postpartum abnormal glucose.

Our findings largely agree with previously published studies of HbA1c measured at GDM diagnosis and postpartum abnormal glucose.(27) Both Oldfield (9) and Ogonowski (10) found that higher HbA1c at GDM diagnosis was associated with increased risk of postpartum abnormal glucose. More recently Ekelund et al (28) found that in a five year follow-up study HbA1c ≥5.7% at GDM diagnosis was associated with a 6-fold increased risk of postpartum diabetes. We also found that when combining women in the highest three HbA1c quartiles, women with HbA1c ≥5.3% had a 2-fold increased risk for any abnormal postpartum glucose compared to women with HbA1c <5.3%. Use of the 5.7% threshold attenuated these findings (data not shown). Unlike Ekelund et al we included impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance and did not look exclusively at type 2 diabetes, and this may explain the slightly lower threshold that we found.

Over 62% of women in this study were of non-white race/ethnicity. Compared with Whites, African Americans and Hispanics have higher average HbA1c.(29) However, we did not detect a difference in the association of HbA1c and postpartum abnormal glucose by race/ethnicity.

While antenatal HbA1c may influence a clinician’s decision regarding initiation of insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents women who require these medications constitute a population with greater underlying disease severity, and the association of HbA1c and postpartum abnormal glucose may differ among those with more severe GDM. Ogonowski et al reported a stronger association of HbA1c and postpartum abnormal glucose among women requiring insulin compared with those who were managed by diet alone.(10) We did not detect a statistically significant interaction between HbA1c ≥5.3% and treatment modality although a the estimates began to diverge when stratifying by treatment..

While impaired fasting glucose is characterized by hepatic insulin resistance and increased endogenous glucose output (30), insulin resistance of muscle tissue and impaired insulin secretion are characteristic of impaired glucose tolerance.(31) Therefore, one might expect the association of HbA1c and abnormal postpartum glucose to differ for impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance depending on the relative contributions of preprandial and postprandial glucose to HbA1c. However, we observed similar trends of increased risk for impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance across quartiles of HbA1c.

Strengths of this study include: size and diversity of the population, detailed information regarding treatment modality, examination of impaired fasting glucose and impaired glucose tolerance as separate outcomes, and statistical analysis that accounted for both left and right censoring. Nevertheless, several limitations should be taken into consideration when interpreting our findings. We were unable to collect detailed information on indicators of socioeconomic status including income and level of education, or health behaviors such as physical activity. However, all final models adjusted for clinic, which was strongly correlated to lack of private insurance and increased probability of obesity, both of which are correlated with lower socioeconomic status and unhealthy lifestyle behaviors.(32)

Adjustment for clinic also accounted for differences in methods used for measurement of both HbA1c and glucose(33, 34). While clinic A relied on capillary glucose, which has lower sensitivity for detecting type 2 diabetes(16) compared with measurements of venous plasma glucose, little to no bias in the hazard ratios would be expected given the high specificity of this method.(35) Finally the generalizability of our findings may have been limited by the failure of women to return for a postpartum oral glucose tolerance test. When we compared the characteristics of women who did and did not complete a postpartum oral glucose tolerance test we found that compared with women who did not complete a postpartum oral glucose tolerance test, women who completed a postpartum oral glucose tolerance test were more likely to have required insulin or oral hypoglycemics, but that the two groups did not differ on any other characteristics.

We found a consistent trend of increased risk of postpartum abnormal glucose across quartiles of HbA1c at GDM diagnosis. Our findings indicate that HbA1c can be a useful and generalizable measure for identifying GDM patients at highest risk of postpartum abnormal glucose.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Misty Morris, RN, for data collection.

Funding: Jodie Katon was supported by grant number T32 HD052462 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), NIH; the Seattle chapter of Achievement Rewards for College Scientists (ARCS); and the Samuel and Althea Stroum Foundation. This study was also funded by a grant from the University of Washington Department of Epidemiology.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

Preliminary results from this study were presented as a poster at the Diabetes and Pregnancy Study Group-West, Denver, CO; May 13-14, 2011 and published in an abstract at the American Diabetes Association, San Diego, CA; June 23–28, 2011.

References

- 1.Gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2004;27 (Suppl 1):S88–90. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2007.s88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim C, Newton KM, Knopp RH. Gestational diabetes and the incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(10):1862–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ratner RE, Christophi CA, Metzger BE, Dabelea D, Bennett PH, Pi-Sunyer X, et al. Prevention of diabetes in women with a history of gestational diabetes: Effects of metformin and lifestyle interventions. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2008:1–16. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Little RR, Rohlfing CL, Tennill AL, Connolly S, Hanson S. Effects of sample storage conditions on glycated hemoglobin measurement: evaluation of five different high performance liquid chromatography methods. Diabetes Technology & Therapeutics. 2007;9(1):36–42. doi: 10.1089/dia.2006.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herranz L, Saez-de-Ibarra L, Grande C, Pallardo F. Non-glycemic-dependent reduction of late pregnancy A1C levels in women with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(6):1579–80. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mosca A, Paleari R, Dalfra MG, Di Cianni G, Cuccuru I, Pellegrini G, et al. Reference intervals for hemoglobin A1c in pregnant women: Data from an Italian multicenter study. Clinical Chemistry. 2006;52(6):1138–43. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.064899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pallardo F, Martin-Vaquero P, Herranz L, Janez M, Garcia-Ingelmo T, Gonzalez A, et al. Early postpartum metabolic assesment in women with prior gestational diabetes. Diabetes Care. 1999;22(7):1053–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.22.7.1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greenberg LR, Moore TR, Murphy H. Gestational diabetes mellitus: antenatal variables as predictors of postpartum glucose intolerance. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1995;86(1):97–101. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(95)00103-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oldfield MD, Donley P, Walwyn L, Scudamore I, Gregory R. Long term prognosis of women with gestational diabetes in a multiethnic population. Postgraduate Medical Journal. 2007;83(980):426–30. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2006.056267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogonowski J, Miazgowski T. The prevalence of 6 weeks postpartum abnormal glucose tolerance in Caucasian women with gestational diabetes. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice. 2009;84(3):239–44. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalfra MG, Lapolla A, Masin M, Giglia G, Dalla Barba B, Toniato R, et al. Antepartum and early postpartum predictors of type 2 diabetes development in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metabolism. 2001;27(6):675–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Report of the Expert Committee on the Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1997;20(7):1183–97. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.7.1183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ACOG Practice Bulletin. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. Number 30, September 2001 (replaces Technical Bulletin Number 200, December 1994). Gestational diabetes. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2001;98(3):525–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stork AD, Kemperman H, Erkelens DW, Veneman TF. Comparison of the accuracy of the HemoCue glucose analyzer with the Yellow Springs Instrument glucose oxidase analyzer, particularly in hypoglycemia. Eur J Endocrinol. 2005;153(2):275–81. doi: 10.1530/eje.1.01952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Orazio P, Burnett RW, Fogh-Andersen N, Jacobs E, Kuwa K, Kulpmann WR, et al. Approved IFCC recommendation on reporting results for blood glucose: International Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine Scientific Division, Working Group on Selective Electrodes and Point-of-Care Testing (IFCC-SD-WG-SEPOCT) Clin Chem Lab Med. 2006;44(12):1486–90. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2006.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kruijshoop M, Feskens EJ, Blaak EE, de Bruin TW. Validation of capillary glucose measurements to detect glucose intolerance or type 2 diabetes mellitus in the general population. Clin Chim Acta. 2004;341(1–2):33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2003.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arsie MP, Marchioro L, Lapolla A, Giacchetto GF, Bordin MR, Rizzotti P, et al. Evaluation of diagnostic reliability of DCA 2000 for rapid and simple monitoring of HbA1c. Acta Diabetol. 2000;37(1):1–7. doi: 10.1007/s005920070028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.John WG, Edwards R, Price CP. Laboratory evaluation of the DCA 2000 clinic HbA1c immunoassay analyser. Ann Clin Biochem. 1994;31 (Pt 4):367–70. doi: 10.1177/000456329403100411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guerci B, Durain D, Leblanc H, Rouland JC, Passa P, Godeau T, et al. Multicentre evaluation of the DCA 2000 system for measuring glycated haemoglobin. DCA 2000 Study Group. Diabetes Metab. 1997;23(3):195–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bode BW, Irvin BR, Pierce JA, Allen M, Clark AL. Advances in hemoglobin A1c point of care technology. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2007;1(3):405–11. doi: 10.1177/193229680700100314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tomeo CA, Rich-Edwards JW, Michels KB, Berkey CS, Hunter DJ, Frazier AL, et al. Reproducibility and validity of maternal recall of pregnancy-related events. Epidemiology. 1999;10(6):774–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brunner Huber LR. Validity of self-reported height and weight in women of reproductive age. Matern Child Health J. 2007;11(2):137–44. doi: 10.1007/s10995-006-0157-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffin J. INTCENS: Stata module to perform interval-censored survival analysis. Boston College Department of Economics; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 24.StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 9. College Station, TX: Statacorp LP; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rothman KJ, Greenland S. Modern Epidemiology. 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S, May S. Applied Survival Analysis. 2. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Katon J, Williams MA, Reiber G, Miller E. Antepartum A1C, maternal diabetes outcomes, and selected offspring outcomes: an epidemiological review. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2011;25(3):265–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2011.01195.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ekelund M, Shaat N, Almgren P, Groop L, Berntorp K. Prediction of postpartum diabetes in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2010;53(3):452–7. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1621-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herman WH, Ma Y, Uwaifo G, Haffner S, Kahn SE, Horton ES, et al. Differences in A1C by race and ethnicity among patients with impaired glucose tolerance in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Care. 2007;30(10):2453–7. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weyer C, Bogardus C, Pratley RE. Metabolic characteristics of individuals with impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes. 1999;48(11):2197–203. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.11.2197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tripathy D, Carlsson M, Almgren P, Isomaa B, Taskinen MR, Tuomi T, et al. Insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity in relation to glucose tolerance: lessons from the Botnia Study. Diabetes. 2000;49(6):975–80. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.6.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Braveman PA, Cubbin C, Egerter S, Williams DR, Pamuk E. Socioeconomic disparities in health in the United States: what the patterns tell us. Am J Public Health. 2010;100 (Suppl 1):S186–96. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.166082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fleiss JL. The Design and Analysis of Clinical Experiments. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 34.White E, Armstrong BK, Saracci R. Principles of Exposure Measurement in Epidemiology. 2. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koepsell TD, Weiss NS. Epidemiologic Methods: Studying the Occurence of Illness. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]