Abstract

Nasopharyngeal colonization provides bacteria with a place of residence, a platform for person-to-person transmission and for many opportunistic pathogens it is a prerequisite event towards the development of invasive disease. Therefore, how host factors within the nasopharynx contribute to, inhibit or otherwise shape biofilm formation, the primary mode of existence for colonizing bacteria, and how biofilm bacteria subvert the acute inflammatory response that facilitates clearance, are important topics for future microbiological research. This review proposes the examination of host components as bridging molecules for bacterial interactions during biofilm formation, altered virulence determinant production and cell wall modification as a mechanism for immunoquiescence, and the role of host factors as signals and co-opted mechanisms for bacterial dissemination, together providing an opportunity for disease.

Keywords: asymptomatic carriage, bacteria, biofilm, colonization, nasopharynx, persistence

Asymptomatic colonization of the nasopharynx is the primary goal for most of the commensal bacteria that opportunistically cause community-acquired pneumonia, as well as for Staphylococcus aureus, which can cause a diverse set of maladies including pneumonia and skin infections. Although the incidence of disease following colonization is generally very low, so many individuals are colonized that the overall morbidity and mortality caused by opportunistic respiratory tract infections is tremendous. Indeed, respiratory tract infections are the third leading cause of death worldwide [1]. Species- and strain-specific colonization trends are highly variable and dependent on age, season, socioeconomic and immunization status, geography and the presence of other commensal colonizers. For example, Streptococcus pneumoniae colonization is seen most often in children who attend daycare, with peak carriage rates of approximately 50% occurring at 2–3 years of age. Rates decline thereafter, reaching approximately 10% in adults [2,3]. By contrast, Neisseria meningitidis colonization increases after birth and peaks during adolescence, with average colonization rates near 10% [4]. S. pneumoniae and S. aureus have an inhibitory relationship, yet S. pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae have a synergistic relationship [5,6]. These complex interactions are not yet fully understood and are most likely simultaneously mediated by a variety of factors including those derived from the host [7,8].

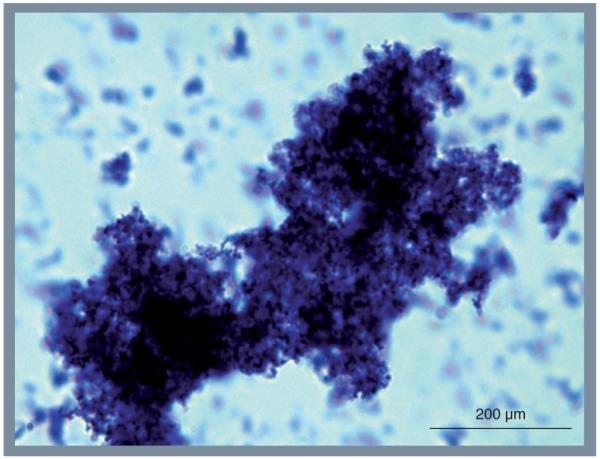

During the past 25 years it has become increasingly evident that the majority (>65%) of persistent bacterial infections, including asymptomatic nasopharyngeal colonization, are mediated by biofilms [9]. These structures are defined as surface attached microbial communities encased within an extracellular polymeric matrix (EPM) composed of proteins, polysaccharides and DNA. Biofilm bacteria exhibit increased resistance to ultraviolet radiation, desiccation and antimicrobials [10-12]. The EPM also confers protection against defensins, antibody-mediated killing and phagocytosis [13-16]. Pertinent to this review, clinical investigations have detected in vivo bacterial biofilms on biopsied mucosal epithelial cells from the nasopharynx of humans, and biofilm formation can be observed in experimentally infected animals [17-22]. Figure 1 is a representative image of the S. pneumoniae biofilm-like aggregates observed in nasal lavage samples collected from colonized mice after 2 weeks. Notably, these aggregates are often composed of >1000 individual pneumococci.

Figure 1. Pneumococcal aggregate/biofilm in the nasopharynx of a colonized mouse.

One of the Streptococcus pneumoniae biofilm aggregates present within nasal lavage fluid collected from experimentally infected mice. The sample used for imaging was collected 2 weeks after intranasal inoculation. Note that individual diplococci are 1–2 μM in length.

Considerable experimental evidence now indicates that biofilm formation is linked to successful colonization. Using transposon mutagenesis, Munoz-Elias et al. identified numerous bacterial genes necessary for robust S. pneumoniae biofilm formation in vitro, and showed that mutants for these genes were impaired for nasopharyngeal colonization of mice [23]. Jurcisek et al. have shown that type IV pilus-deficient mutants of H. influenzae were less efficient in forming cellular aggregates in liquid culture, microcolonies on epithelial cells in vitro, and were attenuated for colonization of the chinchilla nasopharynx [24]. Trappetti et al. have shown that the EPM itself has adhesive properties and facilitates the attachment of entrapped pneumococci to mucosal epithelial cells [25]. Thus, the formation of biofilms presumably facilitates bacterial persistence within the nasopharynx. Of note, not all experimental evidence supports a role for biofilm formation in the nares for S. aureus, with a recent review highlighting available evidence both for and against [26].

Importantly, the molecular interplay between host and biofilm bacteria during nasopharyngeal colonization remains unexplored. Gaining an understanding of how host factors within the nasopharynx contribute to, inhibit or otherwise shape biofilm formation, and in turn, how biofilm bacteria alter the host environment and modulate the host immune response during colonization, is therefore necessary to obtain a thorough understanding of the biology and pathogenesis of clinically important bacteria that occupy the nasopharynx. It is these studies that are the focus of this review.

Dual roles for adhesins & host bridging factors

To form a biofilm, bacteria must attach to a surface and each other. In vivo bacterial adhesion to eukaryotic cells or host extracellular matrix is initially mediated by loose interactions with glycoconjugates such as sialic acid and/or bacterial surface-exposed structures such as pili or fimbriae [27]. This is followed by more robust and intimate interactions through bacterial cell wall components such as phosphorylcholine and surface-exposed proteins that function as adhesins [27,28]. While considerable effort has gone towards identifying the bacterial components important for attachment to airway epithelial cells, much less is known in regard to the molecular mechanisms that mediate bacteria–bacteria interactions crucial for microcolony and subsequent biofilm formation in vivo and which host factors might be involved.

Protein-mediated intrabacterial interactions during microcolony formation most likely occur through two distinct and nonexclusive mechanisms: first, through direct interactions between bacterial components on separate bacteria, and second, through attachment to bridging molecules, which may be derived from the host. Given that many bacterial adhesins have been found to possess secondary and even tertiary roles, it would seem reasonable that surface-exposed host cell adhesins might double as inter- or intra-bacterial adhesins, and/or mediate interactions with host proteins that can be used as a scaffold, such as mucin or fibronectin. One such example is pneumococcal serine-rich repeat protein (PsrP) of S. pneumoniae, which binds to surface-exposed keratin 10 on lung cells through amino acids 273–341 of its basic region domain and binds to PsrP on other pneumococci through amino acids 122–166 [21,29]. Likewise, clumping factor B of S. aureus binds to fibrinogen and keratin 10 and mediates bacterial aggregation and attachment to the nares, respectively [30,31]. Other multifunctional adhesins are the type IV pili of H. influenzae and Moraxella catarhallis, which have been shown to be important in both attachment to epithelial cells and biofilm formation [24,32,33]. Determining whether established bacterial epithelial cell adhesins are expressed during biofilm formation in vivo, and if they are able to recognize other bacterial components as secondary ligands, is therefore an important line of future experimentation.

Notably, homologues of PsrP on other Grampositive bacteria, such as SraP of S. aureus and GspB of Streptococcus gordonii, facilitate bacterial aggregation but also function as lectins and bind to host proteins bearing sialic acid in either α(2–3) or α(2–6) linkages [21,34]. In vivo, this has been shown to contribute towards the formation of endocarditic lesions on heart valves [35], and attachment to the dental surface through interactions with sialylated proteins such as salivary mucin and agglutinin, respectively [36]. In the nasopharynx, SraP or other staphylococcal proteins might facilitate biofilm formation by mediating attachment to the repeated oligosaccharide moieties known to be present on host cells and mucins [37]. As mucins have a natural ability to aggregate bacteria, this phenomenon is reciprocated and likely facilitates the formation of mono- or multi-species aggregates, if not biofilms. It is of interest to note that, while bacterial aggregation on mucin may facilitate clearance, the same aggregates may also serve as infectious, desiccation-resistant particles, able to be spread through secretions. For example, in a daycare setting one could envision the transmission of bacteria through desiccant-resistant mucosal secretions that are present on fomites (e.g., shared toys).

As indicated, highly sialylated mucins are capable of binding to bacteria and contribute to their clearance through expectorations [37-41]. Concomitantly, the majority of respiratory tract pathogens produce sialidases, which are thought to help free entrapped bacteria, expose cryptic ligands covered by cell surface-associated sialic acid and degrade sialic acid such that it can be used as a carbon source [42]. Of note, sialic acid has been found to be within the EPM of even in vitro biofilms and sialidases are required for robust in vitro biofilm formation [43-45]. Moreover, in the case of the pneumococcus, sialic acid has been shown to serve as a signal that promotes biofilm formation [46]. Thus, future studies of biofilm bacteria for other species should include examination of mucins as an environmental signal for biofilm formation in vivo and as a structural component that possibly contributes to successful transmission. Likewise, future studies should examine sialidases as factors that cleave bacteria free from the biofilm and may limit biofilm aggregate size.

Most commensal bacteria also carry microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules (MSCRAMMS) that bind fibronectin, laminin and vitronectin [47,48]. For S. aureus and S. pneumoniae, assorted MSCRAMMS have been shown to be required for successful nasopharyngeal colonization and virulence in human and animal experimental models, respectively [49,50]. In addition, the UspA1 protein of M. catarrhalis, an adhesin known to bind fibronectin and the C3- and C4b-binding proteins, was shown to be an important factor in biofilm formation [51]. The Hap adhesin of H. influenzae has also been shown to posses dual functions, binding to laminin, collagen IV and fibronectin, as well as promoting bacterial aggregation in vitro [52]. Thus, a model can be proposed in which fibronectin or a similar extracellular matrix component forms a molecular bridge between MSCRAMMs on the bacterial surface and surface integrins of another bacterium or host cell, thereby resulting in a microcolony. Other host proteins that might play a role as intra- or inter-species bridges in the nasopharynx are unknown and should be a focus of future research.

Antibodies are most likely to also play a role in the formation of in vivo aggregates. Specific antibodies have long been known to aggregate bacteria via an F(ab’)2 binding of multiple target cells. For S. pneumoniae, this results in a phenomenon known as ‘threading’ and produces large clusters of agglutinated, or chained, bacteria in vitro [53]. As the EPM of mature biofilms is resistant to antibody penetration, it may be of interest to determine if antibodies play a role in biofilm formation by looking for their presence within established matrix material. Intriguingly, Dalia and Weiser recently showed that large bacterial aggregates are more likely to be targeted by the complement system and, as such, are more susceptible to complement-mediated opsonophagocytosis [54]. Their studies showed that reduced community size confers a competitive advantage during invasive disease. Biofilms, by definition, are larger communities and would therefore also be susceptible to such targeted complement deposition, yet they are known to be resistant to phagocytosis owing to their size and the presence of EPM. How biofilm bacteria evade, inhibit or counteract the effects of complement is not known. This will be an interesting area of future research.

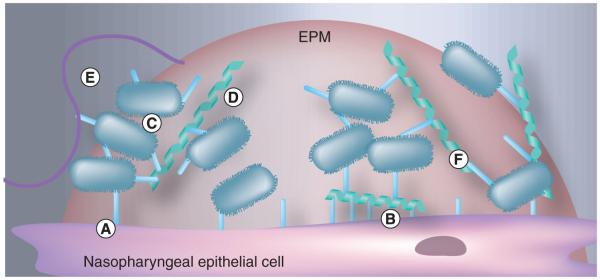

Finally, Trapetti et al. have shown that the EPM, which in vivo is composed of both host and bacterial products, itself functions as an adhesin for entrapped S. pneumoniae [25]. For H. influenzae, intrabacterial adhesion is also at least partially mediated by the EPM and involves both protein adhesins and interactions with extracellular DNA (eDNA) (discussed below) [55]. Other proteins that may play a role in adhesion are enzymes that are normally thought to be intracellular. For example, enolase and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase of S. pneumoniae have been shown to bind plasminogen [56,57]. These would be released during cell death and incorporated into the EPM as the biofilm matures [58]. Thus, better characterization of the components within the EPM and their role in host cell and intrabacterial attachment is needed. Figure 2 is an illustration of the possible mechanisms in play during bacterial biofilm formation in vivo. It is noteworthy to mention that antibodies against dual function adhesins might neutralize both bacterial adhesion to host cells and inhibit biofilm formation, thereby protecting the host at multiple levels and serving as potential protective vaccine antigens. This has already been shown for PsrP [21,59]. For this reason, future studies on intrabacterial adhesins are warranted.

Figure 2. Host–pathogen interactions mediating bacterial attachment.

Individual bacteria can attach to host cells (A) directly via bacterial adhesins or (B) indirectly through host proteins, such as fibronectin, that also bind eukaryotic cells. Bacteria may also attach to each other (C) directly, (D) through bridging molecules and (E) via host factors that function to aggregate the bacteria for clearance (e.g., mucin). As the bacteria transition from a microcolony to a mature biofilm, (F) the extrapolymeric matrix itself entraps bacteria and facilitates its adhesion.

EPM: Extracellular polymeric matrix.

Impact of the host environment on biofilm size, structure & distribution

In vitro, biofilm formation is influenced by environmental factors including nutrient availability, shear forces, and temperature [60-62]. For example, Moscoso et al. showed that attachment and microcolony formation were enhanced when cultures were grown in chemically defined or semi-synthetic media compared with rich media, that the addition of glucose and casamino acids was detrimental to attachment, and that differences in abiotic surface adherence and biofilm formation were seen under varying pH conditions and osmolality [63]. Mechanical forces, a specifically important factor within the nasopharynx, may also impose a limit on overall biofilm size, as regular air flow, movement of mucus and sneezing may result in a continual regulation of the biofilm structure.

During biofilm development, bacterial expression patterns have been shown to shift according to the developmental stage of the community [62,64]. Some of these changes are most likely influenced by interbacterial communication and interactions, such as the LuxRS system, which has been shown to be responsible for initiating the formation of the EPM by S. pneumoniae and to contribute to biofilm formation and persistence by H. influenzae [65,66]. However, nutrient availability and host factors would likely also be important signals that affect biofilm organization, heterogeneity and dispersal. Possible host signals that have not been tested in vitro and are not present at other anatomical sites include ambient oxygen tension, desiccation, shear forces, mucin as a carbon source and lower temperatures [60-62]. Importantly, the strength of these signals on individual bacteria within a biofilm may change as the mature biofilm is formed, thus the impact of any one signal on bacterial behavior may be temporal or stronger in certain parts of the biofilm.

In the case of nasopharyngeal biofilms, dispersal may mark the beginning of a transition from a commensal to pathogen. Release of planktonic bacteria or smaller aggregates creates an opportunity for spread, not only to a naive host, but also to sterile sites possibly leading to disease. In addition to established biofilm dispersal signals, such as d-amino acid production in B. subtilis and auto-inducing peptide of the agr quorum-sensing system in S. aureus [67,68], host and environmental factors most likely play a role. As indicated, these potentially include shear forces, desiccation, limitations in nutrient availability and sialidases. Two others are proteases and DNases (discussed below), both of which target matrix stability and can result in active breakdown of biofilm s tructures and bacterial release [62,69-71].

In regard to proteases, mutants of S. pyogenes that overproduce the cysteine protease SpeB fail to form biofilms in vitro and in vivo, presumably through disruption of the matrix components [72]. Notably, nasal colonization and biofilm formation of S. aureus is inhibited by S. epidermidis, via a novel interaction involving the production of a serine protease [73]. During acute inflammation, host-derived matrix-metalloproteases are upregulated and, therefore, may also act on the biofilm structure. Thus, bacterial and hostproteases may promote the breakup of biofilms for dissemination and clearance, respectively, and serve to inhibit novel biofilm formation by incoming bacteria.

Possible role for extracellular DNA from phage-induced lysis & host cells

In vitro, eDNA, is a major component of biofilms [63,74]. Hall-Stoodley et al. showed that treatment of in vitro biofilms with recombinant human DNase I resulted in significant reductions in biofilm thickness and biomass [74]. In the majority of strains they tested, treatment resulted in over a 90% reduction in average thickness. One interesting consideration is that, in vivo, lysogenic prophage induction of DNA release into pneumococcal communities may have a positive effect on biofilm formation and promote bacterial persistence. Results from recent studies indicate that low-level phage induced lysis promotes biofilm formation in vitro through the release of eDNA [75]. As past studies suggest that during in vivo growth bacteria are under considerable physiological stress [76], increased prophage lytic activity as a result of this sensed stress might promote biofilm formation and thereby enhance the persistence of other neighboring bacteria. Prophage induced lysis may also be partly responsible for some of the complex interspecies interactions seen within the nasopharynx, as Selva et al. showed that the H2O2 production by the pneumococcus may trigger activation of prophages and subsequent lysis of S. aureus [7]. An assessment of differential prophage activity in vivo versus in vitro and its possible contribution as a mechanism for robust biofilm formation and altruistic persistence of lysogenized bacteria, should therefore be examined.

Bacterial DNA found within the EPM may also be a result of bacterial lysis mediated by activation of autolysins, a class of murein hydrolases produced by a number of species that are important for efficient daughter cell separation. In S. pneumoniae, the major autolysin LytA has also been implicated in fratricide, a behavior where competent bacteria are able to lyse noncompetent pneumococci within the same culture, resulting in the release of their DNA [77]. S. pneumoniae mutants lacking the autolysins LytA, LytB and LytC [63], and S. aureus lacking the autolysin AtlA are severely attenuated for biofilm formation [78], presumably owing to the absence of eDNA. Interestingly, for S. aureus, the presence of the autolysin is required for a particular biofilm phenotype that involves binding to fibronectin. By contrast, S. aureus biofilms mediated by polysaccharide intracellular adhesin are less effected by the absence of autolysin [78].

In vivo, neutrophils or macrophages that encounter bacteria release their DNA in an effort to form antimicrobial extracellular traps [79]. Notably, S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae are resistant to killing by extracellular traps. For S. pneumoniae, this has been shown to be due to the presence of capsule and modification of lipotechoic acids and escape from these traps is mediated by bacterial endonuclease activity [80,81]. In addition to resistance to killing by extracellular eukaryotic DNA, H. influenzae is able to incorporate the released DNA and associated proteins into its biofilm structure [82]. Evidence also supports this for P. aeruginosa [83]. Importantly, the overall contribution of host DNA in biofilms during commensal colonization is unclear, as colonization is asymptomatic and the recruitment of neutrophils and macrophages to the nasopharynx during asymptomatic colonization is limited. This may be one way nasopharyngeal biofilms are different from those formed at other anatomical sites. Notably, whether inclusion of host DNA is a mechanism for in vivo biofilm formation by S. aureus, which has been shown to be sensitive to killing by extracellular traps [84], is unknown.

Notably, while most in vitro biofilms studied are composed of millions or even billions of bacteria and are attached to a polystyrene surface or are grown within a glass chamber [64,85,86], those isolated from the nasopharynx of experimentally infected animals and observed on mucosal epithelial cell biopsies are considerably smaller, frequently no more than a few thousand bacteria [17,21,44,87,88]. Thus, the requirement for water channels and towers, as seen in vitro, for distribution of nutrients and the physiology of in vivo biofilm aggregates within the nasopharynx are likely considerably different. The impact of growth within these small biofilms or aggregates on gene expression and virulence is also unknown. Such work has been initiated by investigators such as Whiteley et al., who are creating and beginning to study bacterial biofilms of much smaller sizes within physically confined spaces [89]. Most likely, new technologies that reduce sample size requirements, such as deep sequencing, will play an important role in elucidating how these smaller biofilms in vivo are different than the large and arbitrarily created in vitro biofilms that are studied today.

Immune quiescence through altered virulence determinant production

Whereas pneumonia and systemic infections caused by these aforementioned pathogens are characterized by intense inflammatory responses at the affected sites [28], nasopharyngeal colonization is almost always asymptomatic [90]. Nonetheless, during colonization, a localized mucosal and systemic immune response does occur that includes an early Type I interferon response, remodeling of the basement membrane, T-cell proliferation, development of an antigen-specific CD4+ T-cell response that includes regulatory T cells (Tregs) and the development of opsonizing antibodies against bacterial proteins and capsular polysaccharide [91-96]. The eventual clearance of the colonizing bacteria is due to a combination of these immune events. Importantly, the dramatic difference between the inflammatory response during colonization and an acute infection, strongly suggests that bacteria modify their interactions with the host such that it facilitates long-term quiescent occupation. How this occurs is unknown.

One obvious mechanism for this may be the altered metabolic and synthetic profile of biofilm bacteria versus their planktonic counterparts. Numerous in vitro studies examining gene expression and protein production have shown that biofilm bacteria lower their synthetic capacity and modulate the production of virulence determinants [97,98]. For example, S. aureus displays decreased toxin production, as well as decreased expression of virulence regulatory genes agr and sae, during persistent colonization of the nares [99,100]. Burian et al. also observed an increase in expression of immunomodulatory factors during colonization, including protein A and a number of prophage-encoded immune evasion factors, further implicating a role for immunoquiescence in the establishment of persistent colonization [100]. It is noteworthy to mention that human convalescent sera from individuals recovered from invasive pneumococcal disease preferentially recognized bacterial proteins derived from planktonic cultures and not biofilm cultures, confirming that biofilm bacteria present an altered antigen profile in vivo [101].

For S. pneumoniae, a reduction in the production of the toxin pneumolysin during in vitro biofilm formation occurs [58]. Briefly, pneumolysin is a cholesterol-dependent pore-forming toxin that, in addition to binding to TLR4 and activating the NLRP-3 inflammasome, is able to activate the classical complement cascade through direct binding of the Fc portion of IgG [102,103]. During colonization, pneumolysin has been shown to enhance the acute inflammatory response and induce a localized immune response resulting in increased bacterial clearance 3-8 weeks postinoculation [95]. Thus, its reduced production during biofilm formation is most likely a mechanism to reduce immune detection and facilitate colonization. Stationary phase cultures of S. aureus have been shown to alter their susceptibility to lysozyme through the production of peptidoglycan O-acetylatransferase A [104]. This has recently been shown by Shimada et al. to strongly suppress activation of the NLRP-3 inflammasome by peptidoglycan and thereby prevent inflammation in vitro and in vivo [105]. During colonization of the nares, such a mechanism would likewise facilitate the persistence of colonizing bacteria by both conferring protection against lysozyme in mucosal secretions, and dampening the inflammatory response against biofilm bacteria. Whether other bacteria alter their cell wall structure during biofilm formation would thereby be a very important topic of future research.

Paradoxically, attachment of many respiratory tract pathogens to epithelial cells is facilitated by the induction of a proinflammatory response, which causes the upregulation of surface proteins the bacteria co-opts for adhesion [106,107]. This is one reason elderly humans, who exhibit chronic low-grade inflammation, are at risk for more severe pneumonia caused by these commensal bacteria [108]. Along this line, Ogunniyi et al. have shown that, following intranasal challenge, a pneumolysin-deficient mutant of S. pneumoniae had reduced colony counts in the nasopharynx at days 1 and 2, but not on days 4 or 7, versus the wild-type control [109]. Thus, the requirement for pneumolysin (i.e., inflammation) or other proinflammatory bacterial components might be temporal, initially required for the attachment of planktonic bacteria to host cells, and then turned off during subsequent biofilm formation in order to support long-term quiescent occupation. Such complex interactions can only be studied in vivo.

For S. pneumoniae, in vitro biofilm production has also been associated with reduced capsular polysaccharide production, which would increase its susceptibility to phagocytosis, and increased expression of PsrP and choline-binding protein A [58]. Choline-binding protein A binds to laminin receptor and the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor on epithelial cells, both of which are upregulated during inflammation, and to serum Factor H, thereby promoting the degradation of deposited C3b through serum Factor I [27,110,111]. Obtaining an understanding the temporal changes in protein expression incurred during transition from planktonic to biofilm and how this modulates the proinflammatory immune response within the nasopharynx is fundamental to a thorough understanding of the different commensal bacteria and their pathogenesis.

Immune quiescence through the EPM

Many of the survival strategies attributed to biofilm bacteria arise from the presence of the extracellular matrix and the structure of the biofilm itself. Encasement of bacteria within the EPM allows commensals to avoid a variety of host immune effectors of both the innate and adaptive branches of the immune response. For example, phagocytosis is inhibited when organisms are growing within a biofilm [15,16]. Additionally, multiple species have increased resistance to defensins, host-derived antimicrobial peptides, when grown in a biofilm [13]. This would most likely result in reduced release of proinflammatory lipopolysaccharide from Gram-negative bacteria and lipoteichoic cell wall components for Gram-positive bacteria. The EPM would also limit the release of bacterial components following normal bacterial death. Notably, comparisons between a biofilm-deficient mutant and a wild-type control in regards to the innate immune response during colonization have not been performed. For the above reasons, one could speculate that the inhibition or disruption of biofilms would be proinflammatory and result in more rapid clearance of the bacteria.

Clearance by adaptive immune responses may also be inhibited owing to failure of species-specific antibodies to penetrate the EPM and trigger complement activation [14,16]. The failure of antibodies to penetrate the matrix, or alternatively an altered antigen profile, could explain studies of nasopharyngeal clearance of S. pneumoniae, which suggest humoral responses play a limited role [95,112]. Two characteristics of the EPM might also contribute to this potential evasion mechanism. First, the complexity and structure of the matrix may mask highly immunogenic bacterial proteins important in adaptive immune responses. Secondly, inclusion of host molecules into the matrix may allow bacterial communities to masquerade as ‘self’ structures. For instance, incorporation of Factor H and I may counter the complement activating activity of antibody or other complement-activating factors such as C-reactive protein. As indicated, bacterial aggregate size in both S. pneumoniae and H. influenzae has been correlated with increased complement deposition [54]. Whether this also occurs on established biofilms in vivo, or how the bacteria within the biofilm are able to evade such an attack and remain immune quiescent, is currently unknown. The formation of biofilm structures within the nasopharynx must, therefore, allow for bacterial adhesion, while inhibiting immune recognition and penetration of immune effectors and molecules.

Opposing host factors limit biofilm expansion

Although biofilms function as a mechanism of immune evasion, they are not completely invisible to host defenses. Despite an inability of antibodies to penetrate the matrix, antigen-specific responses are generated against colonizing bacteria and there is some evidence that humoral immunity can protect against biofilm formation, albeit predominantly at early stages. Specific antibody from a previous infection or carriage has been shown to protect against initial attachment and early-stage biofilm formation, but play a limited role in clearance of established colonizers [112,113]. During colonization with S. pneumoniae, CD4+ T cells mediate protection and clearance in an antibody-independent manner [96,112]. Mild inflammatory responses have also been observed during nasopharyngeal carriage with S. pneumoniae, and eventual clearance does occur [114]. Immunization against NTHi can protect against carriage, but the method of immunization is crucial. Mice receiving oral, intraperitoneal or intratracheal immunizations exhibited high systemic immunity, whereas intranasal immunization resulted in mucosal immunity and increased clearance of NHTi from the nasopharynx [115].

For S. pneumoniae, rates of carriage and clearance differ with age and maturity of the immune response, and colonization with a single strain does not protect against all strains [112]. Thus, the immune response to nasopharyngeal colonizers is likely a complicated one. It is, however, present and therefore imposes a limitation on the duration and size of communities persisting within the site. How this may be mediated is not known, but recognition by some immune effectors likely plays a role in the duration of colonization and ability of strains to form aggregates within the nasopharynx. While biofilm-mediated immune evasion may be sufficient to prevent an intense and focused immune response, some immune effectors seem to be able to recognize colonizers and keep them in a relative balance.

Along this line of thought, one must take into consideration the role of the mucosal associated lymphoid tissue in maintaining control of the colonized state and in preventing dysregulated inflammation. In regard to the latter, colonization is now known to initiate expansion of Tregs that suppress the immune response in the nasopharynx during S. pneumoniae colonization [116]. One interesting and potentially important topic of future research would be to determine if Tregs preferentially recognize biofilm-expressed proteins versus planktonic bacterial antigens. Thus, inflammation during colonization would be suppressed, but during invasive disease, a robust immune response would not be inhibited. Importantly, like the GI tract, mucosal epithelial cells and the mucosal-associated lymphoid tissues within the nasopharynx have co-evolved with many of these bacteria and are tolerant of their presence. One would expect that bacteria in biofilms are not passive in this role and are also actively suppressing their immune detection in vivo through the secretion or presentation of immunomodulating factors. One such example might be glycoconjugates on the bacterial surface that interact with Siglec-5 on host cells, which is known to suppress NF-κB activation [117]. An active role for biofilms in modulating the innate immune response is thereby likely to be a major area of research focus in the future.

Conclusion

The interaction between bacteria and the host during biofilm-mediated colonization is an important and unexplored area. Although extensive work has now been carried out on biofilms in vitro, these models represent a simplified view of these structures and do not take into account the events that occur in vivo and the necessary balance between host and colonizer. Notably, commensal colonization is asymptomatic, indicating that the bacteria and host have struck an equitable balance.

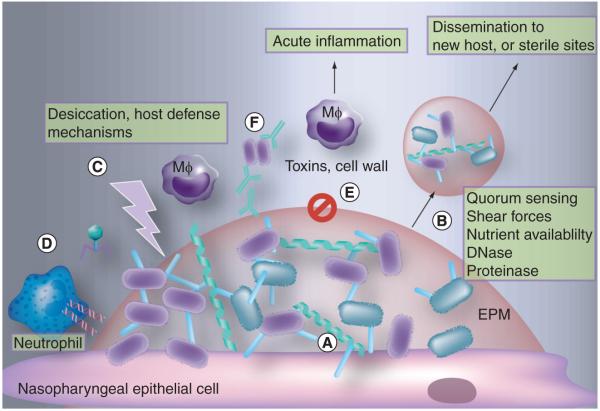

Bacteria most likely utilize host factors during their attachment and incorporate these factors into their EPM. The integration of, and interaction with, host factors most likely facilitates the ability of the bacteria to prevent a robust immune response. Conversely, some immune effectors must function to limit the extent of biofilm formation, resulting in sustained colonization without disease-causing bacterial spread. Additionally, physical and chemical components of the host site being colonized likely affect the overall morphology of the structure and, subsequently, bacterial ability to colonize effectively. Figure 3 highlights how these complex interaction may function simultaneously. Thus, the true scope of the role of biofilms in colonization and disease involves a multitude of factors and research must focus on the balance between them.

Figure 3. Interactions between bacterial factors and host factors shape biofilm development and the immune response within the nasopharynx.

Biofilm formation within the nasopharynx would impact: (A) attachment and adhesion. This includes initial attachment to host cells through extracellular matrix components and biofilm-expressed adhesins, interbacterial interactions and interactions occurring through bridging molecules, such as mucin and fibronectin. (B) Dispersal and release of infectious aggregates. Factors that might affect dispersal include quorum sensing, host shear forces (e.g., sneezing), nutrient availability, host and bacterial DNases, proteinases and sialidases. (C) Of note, biofilm aggregates, both released and those remaining within the host, are resistant to host and environmental factors and suited for transmission through a hostile environment. (D) Release and incorporation of DNA into the extrapolymeric matrix (EPM) in vivo may occur owing to phage-induced lysis, NET formation by macrophages and neutrophils, and bacterial autolysis due to quorum sensing. (E) The altered metabolic profile of biofilm bacteria may include decreased expression of cytotoxic and proinflammatory toxins and cell wall components, including pneumolysin of S. pneumoniae, flagella of multiple other species and lysozyme-susceptible cell wall. (F) Finally, EPM mediated resistance to immune factors is likely to occur through inability of antimicrobial peptides and antibodies to penetrate EPM, a reduction in phagocytosis, masking of immunogenic bacterial components, and inclusion of host molecules that allow biofilm to appear as a ‘self’ structure.

EPM: Extracellular polymeric matrix; Mφ: Macrophage.

Future perspective

If biofilms are a mechanism of persistence, it stands to reason that their formation will be based largely on the opposing forces that they are enduring. While current studies have provided a glimpse at the importance of biofilms in infectious disease, the general biofilm structure and composition, and the role of bacterial proteins, some inconsistencies exist between investigators and models. A probable explanation for these differences is the heavy influence of arbitrary outside factors in biofilm development. Future research will need to take steps to more accurately recapitulate in vivo biofilm phenotypes. While in vivo work will be difficult, and is not always possible, current data provides a good starting point for moving forward. It is reasonable to expect that within 5–10 years information on bacterial biofilm gene expression in vivo will become available.

In vitro studies may be sufficient for elucidating unrestricted biofilm development, but these systems lack an important component: the pressure placed on persisters by the host immune system. Notably, it is not understood why bacteria in the nasopharynx are immune quiescent whereas those found at other sites are not. This topic is beginning to be explored and it is likely that a much more comprehensive understanding of bacterial interactions within the nasopharynx will develop in time.

In summary, it is evident from the current body of knowledge regarding biofilms that these structures are not all identical, and the complexity of their formation involves the host. The key to breaking down these intricate communities may be to change our view on them; instead of regarding them simply as a bacterial process, we need to view them as a product of the interaction between bacteria and host.

Executive summary.

Background

-

■

Nasopharyngeal colonization is a prerequisite for opportunistic respiratory disease.

-

■

Biofilm formation occurs in the nasopharynx and is important for persistence.

-

■

Bacteria within biofilms have increased protection against host immune factors and environmental factors.

-

■

Learning about the interactions between host and bacterial biofilms is critical for an understanding of these commensal bacteria.

Dual roles for adhesins & host bridging factors

-

■

Biofilm bacteria attach to host surfaces, each other and host derived molecules.

-

■

Interbacterial interactions may be bolstered by host components including adhesive matrix molecules and mucin.

-

■

Host components are incorporated into the extracellular polymeric matrix (EPM) and may add structural support or aid in immune evasion.

-

■

Targeting of proteins that interact with host factors with antibody may confer protection against colonization and disease.

Impact of the host environment on biofilm size, structure & distribution

-

■

Host factors most likely act as environmental signals to biofilm bacteria and influence attachment, growth, maturation and dispersal.

-

■

Current in vitro models do not account for in vivo environmental signals.

-

■

In vitro biofilm morphology and size is likely different from in vivo morphology owing to changes in expression patterns and outside mechanical forces. This may impact bacterial physiology.

-

■

It is important to begin to explore how the host environment alters biofilm structure and dispersal.

Possible role for extracellular DNA from phage-induced lysis & host cells

-

■

Extracellular DNA is present in the EPM of many biofilms and aids in structure and/or signaling.

-

■

Prophage-mediated DNA release contributes to biofilm architecture. In vivo stress may be a signal for prophage-mediated cell lysis that facilitates biofilm formation in an altruistic manner.

Altered virulence determinant production as a mechanism for immune quiescence

-

■

The inflammatory response elicited by biofilm colonizers differs from that elicited during acute infections.

-

■

Biofilm bacteria display altered synthetic profiles and decreased expression of immunogenic virulence determinants.

Immune quiescence through the extracellular matrix

-

■

The EPM confers resistance against antimicrobial peptides, antibodies and phagocytosis.

-

■

The complex EPM may mask immunogenic bacterial factors.

-

■

Incorporation of host factors may allow biofilms to appear as ‘self’ structures.

Opposing host factors limit biofilm expansion

-

■

Prior exposure or immunization may prevent initial attachment/early biofilm formation in the nasopharynx.

-

■

Mild immune responses keep colonizers in balance and aid in eventual clearance.

Conclusion

-

■

Biofilm-mediated colonization, particularly within the nasopharynx, is a relatively unexplored area.

-

■

Persistent biofilms are a result of both bacterial and host factors and represent a balance between the two.

Acknowledgments

Financial & competing interests disclosure

Dr Orihuela is sponsored by NIH grant AI078972 to investigate PsrP mediated adhesion for Streptococcus pneumoniae. He is also inventor on a patent pending on PsrP as a vaccine candidate. The authors have no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed.

No writing assistance was utilized in the production of this manuscript.

References

Papers of special note have been highlighted as:

■ of interest

■■ of considerable interest

- 1.WHO The top 10 causes of death. 2011 www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/index.htm.

- 2.Weiser JN. The pneumococcus: why a commensal misbehaves. J. Mol. Med. 2010;88:97–102. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0557-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bogaert D, Degroot R, Hermans PWM. Streptococcus pneumoniae colonisation: the key to pneumococcal disease. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2004;4:144–154. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)00938-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Virji M. Pathogenic neisseriae: surface modulation, pathogenesis and infection control. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009;7:274–286. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bogaert D, Belkum AV, Sluijter M, et al. Colonisation by Streptococcus pneumoniae and Staphylococcus aureus in healthy children. Lancet. 2004;363(9424):1871–1872. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weimer KE, Armbruster CE, Juneau RA, Hong W, Pang B, Swords WE. Coinfection with Haemophilus influenzae promotes pneumococcal biofilm formation during experimental otitis media and impedes the progression of pneumococcal disease. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;202(7):1068–1075. doi: 10.1086/656046. ■ Highlights the complex interactions between two colonizers of the nasopharynx using a biofilm and otitis media model.

- 7.Selva L, Vianaa D, Regev-Yochayb G, et al. Killing niche competitors by remote-control bacteriophage induction. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106(4):1234–1238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809600106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Regev-Yochay G, Lipsitch M, Basset A, et al. The pneumococcal pilus predicts the absence of Staphylococcus aureus co-colonization in pneumococcal carriers. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009;48(6):760–763. doi: 10.1086/597040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Potera C. Forging a link between biofilms and disease. Science. 1999;283:1837–1839. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5409.1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris DP. Bacterial biofilm in upper respiratory tract infections. Curr. Infect. Dis. Rep. 2007;9:186–192. doi: 10.1007/s11908-007-0030-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costerton J, Stewart P, Greenberg E. Bacterial biofilms: a common cause of persistent infections. Science. 1999;284:1318–1322. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5418.1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hall-Stoodley L, Stoodley P. Evolving concepts in biofilm infections. Mol. Cell Biol. 2009;11(7):1034–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Otto M. Bacterial evasion of antimicrobial peptides by biofilm formation. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2006;306:251–258. doi: 10.1007/3-540-29916-5_10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Debeer D, Stoodley P, Lewandowski Z. Measurement of local diffusion coefficients in biofilms by microinjection and confocal microscopy. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 1997;53(2):151–158. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19970120)53:2<151::AID-BIT4>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thurlow L, Hanke M, Fritz T, et al. Staphylococcus aureus biofilms prevent macrophage phagocytosis and attenuate inflammation in vivo. J. Immunol. 2011;186(11):6585–6596. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002794. ■ Discusses the ability of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms to evade the host immune response by inhibiting inflammation and phagocytosis by macrophages.

- 16.Fux CA, Costerton JW, Stewart PS, Stoodley P. Survival strategies of infectious biofilms. Trends Microbiol. 2005;13(1):34–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Galli J, Ardito F, Imperiali M, Bassotti E, Fadda G, Pallidetti G. Biofilm formation by Haemophilus influenzae isolated from adeno-tonsil tissue samples, and its role in recurrent adenotonsilitis. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2007;27:134–138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoa M, Tomovic S, Nistico L, et al. Identification of adenoid biofilms with middle ear pathogens in otitis-prone children utilizing SEM and FISH. Int. J. Pediatr. Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:1242–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kania RE, Lamers GEM, Vonk MJ, et al. Characterization of mucosal biofilms on human adenoid tissues. Laryngoscope. 2008;118(1):128–134. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e318155a464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Psaltis AJ, Ha KR, Beule AG, Tan LW, Wormald P-J. Confocal scanning laser microscopy evidence of biofilms in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2007;177(7):1302–1306. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31806009b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanchez CJ, Shivshankar P, Stol K, et al. The pneumococcal serine-rich repeat protein is an intra-species bacterial adhesin that promotes bacterial aggregation in vivo and in biofilms. PLoS Pathog. 6(8):e1001044–2010. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001044. ■ Identifies a Streptococcus pneumoniae adhesin involved in bacterial aggregation and attachment to host cells.

- 22.Sanclement JA, Webster P, Thomas J, Ramadan HH. Bacterial biofilms in surgical specimens of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2005;115:578–582. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000161346.30752.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Munoz-Elias EJ, Marcano J, Camilli A. Isolation of Streptococcus pneumoniae biofilm mutants and their characterization during nasopharyngeal colonization. Infect. Immun. 2008;76(11):5049–5061. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00425-08. ■■ One of the few papers that has attempted to link biofilm formation with nasopharyngeal colonization; this paper shows that mutants attenuated for biofilm formation are also impaired in their ability to colonize.

- 24.Jurcisek JA, Bookwalter JE, Baker BD, et al. The PilA protein of non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae plays a role in biofilm formation, adherence to epithelial cells and colonization of the mammalian upper respiratory tract. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;65(6):1288–1299. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05864.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Trappetti C, Ogunniyi AD, Oggioni MR, Paton JC. Extracellular matrix formation enhances the ability of Streptococcus pneumoniae to cause invasive disease. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(5):e19844. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krismer B, Peschel A. Does Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization involve biofilm formation? Future Microbiol. 2011;6(5):489–493. doi: 10.2217/fmb.11.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kadioglu A, Weiser JN, Patton JC, Andrew PW. The role of Streptococcus pneumoniae virulence factors in host respiratory colonization and disease. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2008;6:288–301. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gillespie SH, Balakrishnan I. Pathogenesis of pneumococcal infection. J. Med. Microbiol. 2000;49:1057–1067. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-49-12-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shivshankar P, Sanchez C, Rose LF, Orihuela CJ. The Streptococcus pneumoniae adhesin PsrP binds to keratin 10 on lung cells. Mol. Microbiol. 2009;73(4):663–679. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.06796.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O’Brien LM, Walsh EJ, Massey RC, Peacock SJ, Foster TJ. Staphylococcus aureus clumping factor B (ClfB) promotes adherence to human type I cytokeratin 10: implications for nasal colonization. Cell Microbiol. 2002;4(11):759–770. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2002.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walsh EJ, O’Brien LM, Liang X, Hook M, Foster TJ. Clumping factor B, a fibrinogen-binding MSCRAMM (microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules) adhesin of Staphylococcus aureus, also binds to the tail region of type I cytokeratin 10. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279(49):50691–50699. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408713200. ■ Highlights the ability of a bacterial MSCRAMM to bind both host matrix molecules and host cell receptors

- 32.Jurcisek JA, Bakaletz LO. Biofilms formed by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in vivo contain both double-stranded DNA and type IV pilin protein. J. Bacteriol. 2007;189(10):3868–3875. doi: 10.1128/JB.01935-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Luke NR, Jurcisek JA, Bakaletz LO, Campagnari AA. Contribution of Moraxella catarrhalis type IV pili to nasopharyngeal colonization and biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 2007;75(12):5559–5564. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00946-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pyburn TM, Bensing BA, Xiong YQ, et al. A structural model for binding of the serine-rich repeat adhesin GspB to host carbohydrate receptors. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(7):e1002112. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siboo IR, Chambers HF, Sullam PM. Role of SraP, a serine-rich surface protein of Staphylococcus aureus, in binding to human platelets. Infect. Immun. 2005;73(4):2273–2280. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.4.2273-2280.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Takamatsu D, Bensing BA, Prakobphol A, Fisher SJ, Sullam PM. Binding of the streptococcal surface glycoproteins GspB and Hsa to human salivary proteins. Infect. Immun. 2006;74(3):1933–1940. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.3.1933-1940.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Shuter J, Hatcher VB, Lowy FD. Staphylococcus aureus binding to human nasal mucin. Infect. Immun. 1996;64(1):310–318. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.310-318.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bernstein JM, Reddy M. Bacteria-mucin interaction in the upper aerodigestive tract shows striking heterogeneity: implications in otitis media, rhinosinusitis, and pneumonia. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2000;122(4):514–520. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.102402. ■■ Discusses the ability of bacteria to bind mucin, a potentially important host factor in facilitating the formation of aggregates.

- 39.Reddy MS, Bernstein JM, Murphy TF, Faden HS. Binding between outer membrane proteins of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae and human nasopharyngeal mucin. Infect. Immun. 1996;64(4):1477–1479. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1477-1479.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rubin BK. Physiology of airway mucus clearance. Respir. Care. 2002;47(7):761–768. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Landry RM, An D, Hupp JT, Singh PK, Parsek MR. Mucin-Pseudomonas aeruginosa interactions promote biofilm formation and antibiotic resistance. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;59(1):142–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yesilkaya H, Manco S, Kadioglu A, Terra VS, Wandrew P. The ability to utilize mucin affects the regulation of virulence gene expression in Streptococcus pneumoniae. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2008;278(2):231–235. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Parker D, Soong G, Planet P, Brower J, Ratner AJ, Prince A. The NanA neuraminidase of Streptococcus pneumoniae is involved in biofilm formation. Infect. Immun. 2009;77(9):3722–3730. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00228-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jurcisek J, Greiner L, Wantanabe H, Zaleski A, Apicella MA, Bakaletz LO. Role of sialic acid and complex carbohydrate biosynthesis in biofilm formation by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in the chinchilla middle ear. Infect. Immun. 2005;73(6):3210–3218. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3210-3218.2005. ■ Uses an otitis media model to demonstrate the importance of sialic acid in biofilm formation.

- 45.Soong G, Muir A, Gomez MI, et al. Bacterial neuraminidase facilitates mucosal infection by participating in biofilm production. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116(8):2297–2305. doi: 10.1172/JCI27920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trappetti C, Kadioglu A, Carter M, et al. Sialic acid: a preventable signal for pneumococcal biofilm formation, colonization, and invasion of the host. J. Infect. Dis. 2009;199:1497–1505. doi: 10.1086/598483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paterson GK, Orihuela CJ. Pneumococcal MSCRAMM targeting of the extracellular matrix. Mol. Microbiol. 2010;77(1):1–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Speziale P, Pietrocola G, Rindi S, et al. Structural and functional role of Staphylococcus aureus surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules of the host. Future Microbiol. 2009;4(10):1337–1352. doi: 10.2217/fmb.09.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wertheim HFL, Walsh E, Choudhurry R, et al. Key role for clumping factor B in Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization of humans. PLoS Med. 2008;5(1):e17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Holmes AR, McNab R, Millsap KW, et al. The pavA gene of Streptococcus pneumoniae encodes a fibronectin-binding protein that is essential for virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 2001;41(6):1395–1408. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02610.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pearson MM, Hansen EJ. Identification of gene products involved in biofilm production by Moraxella catarrhalis ETSU-9 in vitro. Infect. Immun. 2007;75(9):4316–4325. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01347-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fink DL, Buscher AZ, Green B, Fernsten P, Stgeme JW. The Haemophilus influenzae Hap autotransporter mediates microcolony formation and adherence to epithelial cells and extracellular matrix via binding regions in the C-terminal end of the passenger domain. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5(3):175–186. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00266.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stryker LM. Variations in the pneumococcus induced by growth in immune serum. J. Exp. Med. 1916;24(1):49–68. doi: 10.1084/jem.24.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dalia AB, Weiser JN. Minimization of bacterial size allows for complement evasion and is overcome by the agglutinating effect of antibody. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:486–496. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.09.009. ■■ Presents evidence that bacterial agglutination and aggregate formation is detrimental to survival due to an increase in complement deposition; this is in contrast to the reported ability of biofilms to resist complement-mediated phagocytosis.

- 55.Izano EA, Shah SM, Kaplan JB. Intercellular adhesion and biocide resistance in nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae biofilms. Microb. Pathog. 2009;46:207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kolberg J, Aase A, Bergmann S, et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae enolase is important for plasminogen binding despite low abundance of enolase protein on the bacterial cell surface. Microbiology. 2006;152(Pt 5):1307–1317. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28747-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bergmann S, Rohde M, Hammerschmidt S. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase of Streptococcus pneumoniae is a surface-displayed plasminogen-binding protein. Infect. Immun. 2004;72(4):2416–2419. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.4.2416-2419.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sanchez CJ, Kumar N, Lizcano A, et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae in bioiflms are unable to cause invasive disease due to altered virulence determinant production. PLoS ONE. 2010;6(12):e28738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0028738. ■■ Characterizes altered S. pneumoniae gene expression within a biofilm including that of virulence determinants. Shows that in vitro grown biofilms are attenuated for virulence.

- 59.Rose L, Shivshankar P, Hinojosa E, Rodriguez A, Sanchez CJ, Orihuela CJ. Antibodies against PsrP, a novel Streptococcus pneumoniae adhesin, block adhesion and protect mice against pneumococcal challenge. J. Infect. Dis. 2008;198(3):375–383. doi: 10.1086/589775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nobbs AH, Lamont RJ, Jenkinson HF. Streptococcus adherence and colonization. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2009;73(3):407–450. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00014-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dunne WM. Bacterial adhesion: seen any good biofilms lately? Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2002;15:155–166. doi: 10.1128/CMR.15.2.155-166.2002. ■ Useful review on biofilm attachment, formation and general structure.

- 62.Karatan E, Watnick P. Signals, regulatory networks, and materials that build and break bacterial biofilms. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2009;73(2):310–347. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00041-08. ■ Useful review on the effects of endogenous and exogenous signals on various stages of bacterial sessile life.

- 63.Moscoso M, Garcia E, Lopez R. Biofilm formation by Streptococcus pneumoniae: role of choline, extracellular DNA, and capsular polysaccharide in microbial accretion. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188(22):7785–7795. doi: 10.1128/JB.00673-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Allegrucci M, Hu F, Shen K, et al. Phenotypic characterization of Streptococcus pneumoniae biofilm development. J. Bacteriol. 2006;188(7):2325–2335. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.7.2325-2335.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vidal JE, Ludewick HP, Kunkel RM, Za Hner D, Klugman KP. The LuxS-dependent quorum-sensing system regulates early biofilm formation by Streptococcus pneumoniae strain D39. Infect. Immun. 2011;79(10):4050–4060. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05186-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Armbruster CE, Hong W, Pang B, et al. LuxS promotes biofilm maturation and persistence of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in vivo via modulation of lipooligosaccharides on the bacterial surface. Infect. Immun. 2009;77(9):4081–4091. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00320-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boles BR, Horswill AR. Agr-mediated dispersal of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(4):e1000052. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kolodkin-Gal I, Romero D, Cao S, Clardy J, Kolter R, Losick R. d-amino acids trigger biofilm disassembly. Science. 2010;328(5978):627–629. doi: 10.1126/science.1188628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Picioreanu C, Vanloosdrecht MCM, Heijnen JJ. Two-dimensional model of biofilm detachment caused by internal stress from liquid flow. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2001;72(2):205–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sauer K, Cullen MC, Rickard AH, Zeef LaH, Davies DG, Gilbert P. Characterization of nutrient-induced dispersion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 biofilm. J. Bacteriol. 2004;186(21):7312–7326. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.21.7312-7326.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hunt SM, Werner EM, Huang B, Hamilton MA, Stewart PS. Hypothesis for the role of nutrient starvation in biofilm detachment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004;70(12):7418–7425. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.12.7418-7425.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Roberts AL, Connolly KL, Doern CD, Holder RC, Reid SD. Loss of the group A streptococcus regulator Srv decreases biofilm formation in vivo in an otitis media model of infection. Infect. Immun. 2010;78(11):4800–4808. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00255-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Iwase T, Uehara Y, Shinji H, et al. Staphylococcus epidermidis Esp inhibits Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation and nasal colonization. Nature. 2010;465:346–351. doi: 10.1038/nature09074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hall-Stoodley L, Nistico L, Sambanthamoorthy K, et al. Characterization of biofilm matrix, degradation by DNase treatment and evidence of capsule downregulation in Streptococcus pneumoniae clinical isolates. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:173. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-173. ■■ Demonstrates a general composition of S. pneumoniae biofilm EPM and highlights the importance of DNA within the structure to biofilm stability.

- 75.Carrolo M, Frias MJ, Pinto FR, Melo-Cristino J, Ramirez M. Prophage spontaneous activation promotes DNA release enhancing biofilm formation in Streptococcus pneumoniae. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(12):e15678. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Orihuela CJ, Radin JN, Sublett JE, Gao G, Kaushal D, Tuomanen EI. Microarray ana lysis of pneumococcal gene expression during invasive disease. Infect Immun. 2004;72(10):5582–5596. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.5582-5596.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Claverys JP, Martin B, Havarstein LS. Competence-induced fratricide in streptococci. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;64(6):1423–1433. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05757.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Houston P, Rowe SE, Pozzi C, Waters EM, O’Gara JP. Essential role for the major autolysin in the fibronectin-binding protein-mediated Staphylococcus aureus biofilm phenotype. Infect. Immun. 2011;79(3):1153–1165. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00364-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Brinkmann V, Reichard U, Goosmann C, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps kill bacteria. Science. 2004;303(5663):1532–1535. doi: 10.1126/science.1092385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wartha F, Beiter K, Albiger B, et al. Capsule and d-alanylated lipoteichoic acids protect Streptococcus pneumoniae against neutrophil extracellular traps. Cell Microbiol. 2007;9(5):1162–1171. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Beiter K, Wartha F, Albiger B, Normark S, Zychlinsky A, Henriques-Normark B. An endonuclease allows Streptococcus pneumoniae to escape from neutrophil extracellular traps. Curr. Biol. 2006;16(4):401–407. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Juneau RA, Pang B, Weimer KED, Armbruster CE, Swords WE. Nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae initiates formation of neutrophil extracellular traps. Infect. Immun. 2011;79(1):431–438. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00660-10. ■ Interesting report of Haemophilus influenzae hijacking of host cells and active incorporation of host DNA into the biofilm matrix.

- 83.Walker TS, Tomlin KL, Worthen GS, et al. Enhanced Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development mediated by human neutrophils Infect. Immun. 2005;73(6):3693–3701. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3693-3701.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Pilsczek FH, Salina D, Poon KK, et al. mechanism of rapid nuclear neutrophil extracellular trap formation in response to Staphylococcus aureus. J. Immunol. 2010;85(12):7413–7425. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Lizcano A, Chin T, Sauer K, Tuomanen EI, Orihuela CJ. Early biofilm formation on microtiter plates is not correlated with the invasive disease potential of Streptococcus pneumoniae. Microb. Pathog. 2010;48(3-4):124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gallaher TK, Wu S, Webster P, Aguilera R. Identification of biofilm proteins in non-typeable Haemophilus Influenzae. BMC Microbiol. 2006;6:65. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-6-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hall-Stoodley L, Hu FZ, Gieseke A, et al. Direct detection of bacterial biofilms on the middle-ear mucosa of children with chronic otitis media. JAMA. 2006;296(2):202–211. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.2.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Reid SD, Hong W, Dew KE, et al. Streptococcus pneumoniae forms surface-attached communities in the middle ear of experimentally infected chinchillas. J. Infect. Dis. 2009;199:786–794. doi: 10.1086/597042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Connell JL, Wessel AK, Parsek MR, Ellington AD, Whiteley M, Shearad JB. Probing prokaryotic social behaviors with bacterial ‘lobster traps’. MBio. 2010;1(4):e00202–e00210. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00202-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Crook DW, Brueggemann AB, Sleeman KL, Peto TEA. Pneumococcal carriage. In: Tuomanen EI, Mitchell TJ, Morrison DA, Spratt BG, editors. The Pneumococcus. ASM Press; Washington, DC, USA: 2004. pp. 136–147. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Joyce EA, Popper SJ, Falkow S. Streptococcus pneumoniae nasopharyngeal colonization induces type I interferons and interferon-induced gene expression. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:404. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.McCool TL, Cate TR, Moy G, Weiser JN. The immune response to pneumococcal proteins during experimental human carriage. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195(3):359–365. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang Q, Bernatoniene J, Bagrade L, et al. Serum and mucosal antibody responses to pneumococcal protein antigens in children: relationships with carriage status. Eur. J. Immunol. 2006;36(1):46–57. doi: 10.1002/eji.200535101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Malley R, Trzcinski K, Srivastava A, Thompson CM, Anderson PW, Lipsitch M. CD4+ T cells mediate antibody-independent acquired immunity to pneumococcal colonization. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102(13):4848–4853. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501254102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Van Rossum AM, Lysenko ES, Weiser JN. Host and bacterial factors contributing to the clearance of colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae in a murine model. Infect. Immun. 2005;73(11):7718–7726. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.11.7718-7726.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Trzcinsk K, Thompson CM, Srivastava A, Basset A, Malley R, Lipsitch M. Protection against nasopharyngeal colonization by Streptococcus pneumoniae is mediated by antigen-specific CD4+ T cells. Infect. Immun. 2008;76(6):2678–2684. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00141-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sauer K, Camper AK. Characterization of phenotypic changes in Pseudomonas putida in response to surface-associated growth. J. Bacteriol. 2001;183(22):6579–6589. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.22.6579-6589.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Whiteley M, Bangera MG, Bumgarner RE, et al. Gene expression in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Nature. 2001;413:860–864. doi: 10.1038/35101627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Burian M, Rautenberg M, Kohler T, et al. Temporal expression of adhesion factors and activity of global regulators during establishment of Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization. J. Infect. Dis. 2010;201(9):1414–1421. doi: 10.1086/651619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Burian M, Wolz C, Goerke C. Regulatory adaptation of Staphylococcus aureus during nasal colonization of humans. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(4):e10040. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010040. ■■ Describes a change in overall gene expression during prolonged nasopharyngeal colonization by S. aureus, including decreases in production of virulence determinants and increases in production of immunomodulatory factors.

- 101.Sanchez CJ, Hurtgen BJ, Lizcano A, Shivshankar P, Cole GT, Orihuela CJ. Biofilm and planktonic pneumococci demonstrate disparate immunoreactivity to human convalescent sera. BMC Microbiol. 2011;11:245. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-11-245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Oggioni MR, Trappetti C, Kadioglu A, et al. Switch from planktonic to sessile life: a major event in pneumococcal pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;61(5):1196–1210. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Malley R, Henneke P, Morse SC, et al. Recognition of pneumolysin by Toll-like receptor 4 confers resistance to pneumococcal infection. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100(4):1966–1971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0435928100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Bera A, Herbert S, Jakob A, Vollmer W, Gotz F. Why are pathogenic staphylococci so lysozyme resistant? The peptidoglycan O-acetyltransferase OatA is the major determinant for lysozyme resistance of Staphylococcus aureus. Mol. Microbiol. 2005;55(3):778–787. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Shimada T, Park BG, Wolf AJ, et al. Staphylococcus aureus evades lysozyme-based peptidoglycan digestion that links phagocytosis, inflammasome activation, and IL-1beta secretion. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;7(1):38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Orihuela CJ, Fogg G, Dirita VJ, Tuomanen EI. Bacterial interactions with mucosal epithelial cells. In: Mestecky J, Lamm ME, Strober W, Bienenstock J, Mcghee JR, Mayer L, editors. Mucosal Immunology. Elsevier Academic Press; Burlington, MA, USA: 2005. pp. 753–767. [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hinojosa E, Boyd AR, Orihuela CJ. Age-associated inflammation and Toll-like receptor dysfunction prime the lungs for pneumococcal pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 2009;200(4):546–554. doi: 10.1086/600870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Shivshankar P, Boyd AR, Le Saux CJ, Yeh IT, Orihuela CJ. Cellular senescence increases expression of bacterial ligands in the lungs and is positively correlated with increased susceptibility to pneumococcal pneumonia. Aging Cell. 2011;10(5):798–806. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2011.00720.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ogunniyi AD, Lemessurier KS, Graham RMA, et al. Contributions of pneumolysin, pneumococcal surface protein A (PspA), and PspC to pathogenicity of Streptococcus pneumoniae D39 in a mouse model. Infect. Immun. 2007;75(4):1843–1851. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01384-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Orihuela CJ, Mahdavi J, Thornton J, et al. Laminin receptor initiates bacterial contact with the blood brain barrier in experimental meningitis models. J. Clin. Invest. 2009;119(6):1638–1646. doi: 10.1172/JCI36759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhang JR, Mostov KE, Lamm ME, et al. The polymeric immunoglobulin receptor translocates pneumococci across human nasopharyngeal epithelial cells. Cell. 2000;102(6):827–837. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00071-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.McCool TL, Weiser JN. Limited role of antibody in clearance of Streptococcus pneumoniae in a murine model of colonization. Infect. Immun. 2004;72(10):5807–5813. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.10.5807-5813.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Tashiro Y, Nomura N, Nakao R, et al. Opr86 is essential for viability and is a potential candidate for a protective antigen against biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol. 2008;190(11):3969–3978. doi: 10.1128/JB.02004-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Joyce EA, Popper SJ, Falkow S. Streptococcus pneumoniae nasopharyngeal colonization induces type I interferons and interferon-induced gene expression. BMC Genomics. 2009;10:404. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Kurono Y, Yamamoto M, Fujihashi K, et al. Nasal immunization induces Haemophilus influenzae-specific Th1 and Th2 responses with mucosal IgA and systemic IgG antibodies for protective immunity. J. Infect. Dis. 1999;180(1):122–132. doi: 10.1086/314827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Zhang Q, Leong SC, McNamara PS, Mubarak A, Malley R, Finn A. Associated lymphoid tissue in children: relationships with pneumococcal colonization. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7(8):e1002175. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Carlin AF, Chang YC, Areschoug T, et al. Group B streptococcus suppression of phagocyte functions by protein-mediated engagement of human Siglec-5. J. Exp. Med. 2009;206(8):1691–1699. doi: 10.1084/jem.20090691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]