Abstract

The objective of this study was to develop transgenic Yucatan minipigs that overexpress human catalase (hCat) in an endothelial-specific manner. Catalase metabolizes hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), an important regulator of vascular tone that contributes to diseases such as atherosclerosis and preeclampsia. A large animal model to study reduced endothelium-derived H2O2 would therefore generate valuable translational data on vascular regulation in health and disease. Yucatan minipig fetal fibroblasts stably co-transfected with human catalase (Tie2-hCat) and eGFP expression constructs were isolated into single-cell populations. The presence of the Tie2-hCat transgene in individual colonies of fibroblasts was determined by PCR. Transgenic fibroblasts were used for nuclear transfer into enucleated oocytes by electrofusion. A minimum of 140 cloned embryos were transferred per surrogate sow (n = 4). All four surrogates maintained pregnancies and piglets were delivered by cesarean section. Nine male piglets from three of the four litters carried the Tie2-hCat transgene. Expression of human catalase mRNA and overall elevated catalase protein in isolated umbilical endothelial cells from transgenic piglets were verified by RT–PCR and western blot, respectively, and endothelial localization was confirmed by immunohistochemistry. Increased enzymatic activity of catalase in transgenic versus wild-type endothelial cells was inferred based on significantly reduced levels of H2O2 in culture. The similarities in swine and human cardiovascular anatomy and physiology will make this pig model a valuable source of information on the putative role of endothelium-derived H2O2 in vasodilation and in the mechanisms underlying vascular health and disease.

Keywords: Endothelium, Catalase, Hydrogen peroxide, Swine, Somatic cell nuclear transfer, Vascular

Introduction

Endothelial hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) plays key roles in cardiovascular regulation (Drouin and Thorin 2009), maintenance of healthy pregnancy (Aris et al. 2009), and age-accelerated vascular disorders (Collins et al. 2009). Endogenous H2O2, generated by the dismutation of O2–, is involved in endothelial adaptation to exercise training as this appears to be a signal stimulating upregulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS; Lauer et al. 2005; Thengchaisri et al. 2007). Also, H2O2 has been proposed as an endothelium-dependent hyperpolarizing factor (Capettini et al. 2008). Specifically, H2O2 can increase eNOS promoter activity, stabilize eNOS mRNA, and enhance eNOS catalytic activity (Searles 2006; Kumar et al. 2009; Bodiga et al. 2010). Furthermore, vasodilation to exogenous and endogenous H2O2 has been reported in coronary arteries and arterioles (Yada et al. 2007; Mink et al. 2008), skeletal muscle arterioles (Marvar et al. 2007; Samora et al. 2008), and subcutaneous arteries from preeclamptic women (Luksha et al. 2008). Enzymes such as catalase and glutathione peroxidase tightly regulate H2O2 levels in vascular tissue, but because catalase possesses a higher Km (Ardanaz and Pagano 2006), it may play a more important role in the control of H2O2 concentrations in the endothelium.

Rodent model systems have been used to study the regulatory roles of endothelium-derived H2O2. Three weeks of exercise in wild-type mice resulted in a three-fold increase in endothelial expression of eNOS. In the same study, however, transgenic mice that express human catalase in the endothelium had no increase in eNOS expression after the same 3 week exercise period (Lauer et al. 2005). At a physiological level, exogenous catalase in rat arterioles completely abolished or reduced flow-mediated vasodilation in an exercise-dependent manner, and thus it is thought that age related decline in H2O2-mediated signaling is restored by exercise training (Sindler et al. 2009). These important findings are supported by endothelial cell culture data describing H2O2 as a regulator of eNOS (Thomas et al. 2007; Dong et al. 2008; Shimizu et al. 2008). Although highly important, these data may not provide a complete phenotypic description of the effects of H2O2 on human vascular health due to anatomical and physiological differences between rodents and humans. A large transgenic animal model may serve as a more accurate representation of the human system and reveal additional insight into the mechanisms of H2O2 effects in health and disease.

In this paper, we report the production of cloned miniature swine that carry a human catalase transgene (Tie2-hCat; Lauer et al. 2005) whose expression is driven in endothelial cells by a Tie2 transmembrane protein receptor tyrosine kinase (RTK) regulatory sequence. Along with Tie1 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), Tie2 is the only known endothelial cell-specific RTK (Seegar et al. 2010). Pigs and humans have similar metabolic rates, physical size, smooth muscle content, and hemodynamic environment in conduit arteries (Turk and Laughlin 2004; Vodicka et al. 2005). These characteristics make swine an excellent biomedical model for cardiovascular research. The catalase overexpressing pigs described herein provide a novel model system to study the effects of decreased endothelium-derived H2O2 in vascular regulation in health and disease. This large animal model is capable of supplying ample tissue and blood to study and describe the molecular, biochemical and physiological effects of increased catalase in the endothelium.

Methods

Ethical guidelines

All animal procedures were performed with an approved University of Missouri Animal Care and Use (ACUC) protocol. Recombinant DNA technologies were performed with an approved protocol from the Institutional Biosafety Committee.

Tie2-hCat targeting construct

The transgenic construct expressing human catalase was a generous gift from Dr. Georg Kojda (Institut für Pharmakologie und Klinische Pharmakologie, Heinrich-Heine-Universität, Düsseldorf, Germany). The Tie2 regulatory region is expressed predominantly in endothelial cells, providing cell-specific expression of the catalase transgene (Schlaeger et al. 1997). XL1-Blue competent cells (40 μL; Stratagene, CA) were transformed with 5 ng of the Tie2-hCat construct in a pBluescriptII SK(+) vector backbone or with a pUC19 control plasmid to verify electroporation efficiency. Cells were plated on LB agar containing ampicillin and incubated overnight at 37°C. Individual colonies (n = 5) from both the control plate and the Tie2-hCat transformed cells were picked and inoculated in LB Broth containing ampicillin and incubated in a rotating shaker (225 rpm) overnight at 37°C. Tie2-hCat plasmid vectors were isolated from single colonies by using a Qiagen miniprep kit (Qiagen, CA) and linearized by digestion with SalI to excise the pBluescriptII SK(+) backbone. The 15 kb band corresponding to the expected size of the Tie2-hCat fragment was gel purified to obtain 10 μg of linearized transgene insert. An aliquot (1 μg) of the insert was sent to the University of Missouri DNA Core facility for sequencing. The pCAGG-EGFP vector was prepared and linearized with AseI as described previously (Whitworth et al. 2009).

Culture and electroporation of porcine fetal fibroblasts

Frozen aliquots of male NIH Yucatan minipig day-35 fetal fibroblasts were thawed and maintained in culture at 38.5°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 in air. Cell culture medium consisted of Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM, Sigma, MO; D5648), 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Hyclone; Catalog: SH30071.03 Lot: ASM31113), antibiotic (10 μg/mL, gentamicin, Sigma; G3632), and basic fibroblast growth factor (2.5 ng/mL, Sigma; F0291). Culture medium was changed every 2 days and cells were passaged upon confluency no more than two iterations before transfection. Fetal fibroblasts of similar passage number were cultured overnight and grown to 75–85% confluency and medium was changed 4 h before transfection. Fibroblasts were washed with PBS, trypsin-digested, and pelleted at 700 rpm for 10 min. The cells were resuspended in 10 mL Opti-MEM (Invitrogen, CA), and the cell concentration determined by hemocytometer count. Pelleted cells were resuspended in transfection medium (75% cytosalts [120 mM KCl, 0.15 mM CaCl2, 10 mM K2HPO4; pH 7.6, 5 mM MgCl2] and 25% Opti-MEM), and the cell concentration was adjusted to 1 × 106 cells/mL. A recently described optimized electroporation method (Ross et al. 2010) was carried out with a BTX ECM 2001 square-wave pulse instrument using 2 mm gap cuvettes. For selection of cells incorporating the Tie2-hCat transgene, a linearized eGFP reporter gene construct (Whitworth et al. 2009) was co-transfected at a ratio of 10 μg Tie2-hCat to 0.3 μg eGFP per electroporation. Transfected fibroblasts were allowed to recover for 96 h in DMEM culture medium.

Selection of transgenic fetal fibroblasts by fluorescence automated cell sorting (FACS)

Electroporated cells were trypsinized and an aliquot was resuspended in 1 mL of ice cold PBS; the remaining cells were cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen with 10% DMSO in FBS. Cells expressing eGFP were sorted based on fluorescence on a FACSDiva flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, CA) at the University of Missouri Cell and Immunology Core. Cells were gated for viability based on forward and side scatter characteristics. 96-well plates received a single cell in DMEM medium with a total of ten plates sorted. Cells were cultured for 1–2 weeks based on differences in growth rates and then passaged into 24-well plates for expansion. Thirteen confluent colonies were selected for Tie2-hCat genotyping based on growth rate, cell morphology, and healthy appearance. Aliquots of each colony were cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) genotyping

DNA was extracted from the thirteen eGFP-positive clonal populations of Yucatan fetal fibroblasts by using a DNeasy kit (Qiagen). PCR was performed on 100 ng of genomic DNA with a GoTaq green mastermix (Promega, CA) and 400 nM of forward and reverse transgene specific genotyping primers (Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT), Coralville, IA). The forward primer annealed to the 30 region of the Tie-2 promotor (5′-GGGAAGTCGCAAAGTTGTGAGTT-3′) and the reverse primer annealed to the 5′ region of the hCat cDNA (5′-CCGATTCTCCAGCAACAG-3′), yielding a 470 bp product. DNA from cultured wild-type Yucatan cells electroporated with eGFP, but not the Tie2-hCat transgene were used as negative controls. Content and quality of DNA loaded in the PCR reaction was confirmed by amplification of the endogenous swine eNOS gene (243 bp PCR product; forward primer 5′-ACGAGCCTCCAGAACTCTTTGCTT-3′; reverse primer 5′-TTTCCAGCAGCATGTTGGACACTG-3′).

Somatic cell nuclear transfer (SCNT) and piglet delivery

Fibroblast colonies determined to have integration of the Tie2-hCat transgene were used as donor cells for SCNT into enucleated oocytes followed by electrical fusion and activation (described previously by Zhao et al. 2009). Embryo transfer was performed as previously described by our lab (Lai and Prather 2003; Whitworth et al. 2009). Briefly, commercial oocytes (ART Inc., WI) were received by overnight shipment in “maturation medium #1”. These oocytes were then cultured in fresh maturation medium for a total of 40 h. Cumulus cells were removed and oocytes having an extruded first polar body (PB) with uniform cytoplasm were selected for SCNT. Metaphase II (MII) oocytes were enucleated by aspirating the PB and MII chromosomes. Single transgenic donor cells were introduced into the perivitelline space, placed adjacent to the recipient cytoplasm and electrically fused and activated. Four nuclear transfers were performed (n = 126–150 embryos each). Three of the transfers used three different clonal colonies derived from single cells that were genotyped as Tie2-hCat positive. A fourth group of fibroblasts was derived from a heterogeneous mixture of Tie2-hCat transfected cells that were selected by FACS as eGFP positive (1,000 cells originally seeded) to determine the efficiency of the eGFP:Tie2-hCat transgene ratio used during electroporation. Day 1 SCNT embryos were transferred to four surrogate sows on the day of, or 1 day after the onset of estrus and were checked for pregnancy by abdominal ultrasound examination after day 21 and then weekly throughout gestation. Cesarean section was performed to recover the piglets on day 116–118 of gestation. Individual piglets were each handled by separate technicians using dedicated instruments for tissue collection to avoid cross contamination among clones. Tissue was immediately collected from ear and tail and placed on ice for PCR genotyping or in RNA later (Ambion, TX) for RT–PCR analysis of transgene expression. Sections of umbilical cords from each piglet were used for endothelial cell isolation and immunohistochemical analysis (see below). After delivery, the piglets were provided medical care, fed colostrum, and initially raised on a commercial pig milk replacer until mature enough to be placed on standard pig diets. The presence of the Tie2-hCat transgene in piglets born from the four surrogates was determined by PCR in ear snip DNA extracted using the method described for genotyping fetal fibroblasts. Control tissues used for genotyping and subsequent characterization methods were collected from cloned piglets (Landrace) derived for an unrelated study from cells that were not transfected with the Tie2-hCat transgene but that were delivered on the same day. Thus, these clones provided age-matched porcine tissues, albeit from a different strain.

Isolation of porcine umbilical endothelial cells (PUVECs)

Porcine umbilical endothelial cells were collected from Tie2-hCat and control cloned piglets based on the method of Baudin et al. (2007). Briefly, upon surgical removal of the piglet from the uterus, the umbilical cord was tied off and a 10 cm section of the cord was placed in 50 mL 1 × PBS (–CaCl2; –MgCl2; Invitrogen) with 10 μg/mL gentamicin (APP Pharmaceuticals, IL) on ice. Umbilical cords were processed individually, sterilizing the work area with 70% ethanol between samples. Cord ends were trimmed with a clean scalpel blade and a cannula/syringe apparatus was attached to the umbilical vein under a dissection scope, keeping the cord moist with a small amount of 1× PBS/gentamicin. The umbilical vein was flushed with 1× PBS/gentamicin by syringe to remove all erythrocytes. A solution of 0.2% collagenase (Sigma) was injected into the umbilical vein until flow-through was visible and then the ends of the cord were clamped with a sterile hemostat. The clamped cord was transferred to a 14 cm diameter petri dish and placed in a 38.5°C culture incubator. After a 10 min incubation, endothelial cells were washed from the vein with 5 mL of warmed 1× PBS/gentamicin via syringe under a sterile laminar flow hood. The endothelial cells were aliquoted into two tubes and centrifuged at 700 rpm for 5 min. Cells in the first tube were resuspended in 10 mL of warm M199 medium (Invitrogen) containing 20% FBS (Hyclone, MA), 5 ng/mL FGF (Sigma), 10 μg/mL gentamicin, 2 mM l-glutamine (Invitrogen) and 15 mM HEPES (Invitrogen) and cultured at 38.5°C in a 5% CO2 incubator for 6–8 days (or until confluent). The second aliquot of cells was resuspended in a 500 μL of 1X PBS, divided into two 250 μL portions to be stored for mRNA analysis (RNAlater) and protein isolation (Laemmli buffer; 62.5 mM Tris, pH 6.8, 6 M urea, 160 mM dithiothreitol, 2% SDS, and 0.001% bromophenol blue). Cells in culture were divided for use for subsequent H2O2 bioassay and cryopreservation.

Expression of Tie2-hCat transgene mRNA in isolated PUVECs (RT–PCR)

Umbilical endothelial cell RNA from Tie2-hCat and control piglets was extracted using the RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen), DNase-treated (Ambion), and quantified by using a Nanodrop spectrophotometer (Wilmington, DE). First-strand cDNA for each piglet was synthesized from 150 ng RNA by reverse transcription (RT; iScript DNA Synthesis Kit; BioRad, Hercules, CA) with appropriate no-reverse transcriptase controls. Quantitative real-time RT–PCR was performed on the RT product with primers specific to human catalase (Ammerschlaeger et al. 2004) and validated to not amplify swine catalase (forward 5′-AAGAATGCGATTCACACCTTTGT-3′, reverse 5′-TTACACGGATGAACGCTAAGCTT-3′; IDT DNA). Swine GAPDH primers (Zhu et al. 2004) were used to amplify the endogenous control product (forward 5′-GGGCATGAACCATGAGAAGT-3′, reverse 5′-GTCTTCTGGGTGGCAGTGAT-3′; IDT DNA). The reactions were conducted in duplicate with a BioRad iCycler and SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad, Hercules, CA) with equal amounts of endothelial cell cDNA. A dissociation curve analysis was performed after each run to verify the identity of the RT–PCR products. The comparative cycle threshold (2–ΔΔCt) method was utilized to calculate human catalase expression (Schmittgen and Livak 2008). When possible, aortic endothelial scrapes were collected from piglets for mRNA and protein analysis if mortality occurred.

Western blot of expressed human catalase

Catalase protein content in PUVECs was tested using standard western blot techniques as described previously (Laughlin et al. 2001). Briefly, PUVEC flushes suspended in Laemmli buffer were boiled and sonicated to expose the intracellular contents. Total protein in each sample was quantified using the NanoOrange Protein Quantitation Kit (Invitrogen) and 3 μg of protein was loaded onto a polyacrylamide gel and separated by electrophoresis. After protein separation, contents of the gel were transferred to a polyvinylidene diflouride (PVDF) membrane by the application of 34 V for 1 h, and this membrane was subsequently blocked with 5% non-fat milk in TBS-Tween (20 mM Tris–HCl, 137 mM NaCl, and 0.1% Tween 20) at room temperature for 1 h. After 1 h incubation in non-fat milk, the primary antibody (monoclonal anti-catalase 1:2,500, Sigma) was applied overnight. This mouse antibody (IgG1) was produced by immunization with human catalase, but reactivity has been observed with human, bovine, rat, and mouse catalase (Sigma product literature) and this crossreactivity was observed with swine protein our pilot tests. The following morning the secondary antibody (1:2,500; horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse) was applied for 1 h and then catalase content was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham, NJ) and quantified by densitometry through the use of Kodak 4000R Imager and Molecular Imagery Software (Kodak Molecular Imaging Systems, New Haven, CT).

Immunohistochemical localization of human catalase in umbilical vessels

Cross-sections of the umbilical cord were dissected and immersed in neutral-buffered 10% formalin for ≥24 h using standard techniques (Homma et al. 2001; McAllister et al. 2005). The sections were processed to paraffin embedment, and 5 μm sections were cut with an automated microtome (Microm, Thermo Fischer Scientific, PA), floated onto positively charged slides (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Bellefonte, PA), and deparaffinized. Each slide contained both wild-type and Tie2-hCat sections to avoid introduction of slide-to-slide staining variation. Slides were then steamed in citrate buffer at pH 6.0 (Dako target retrieval solution S1699, DAKO, Carpenteria, CA) for 30 min to achieve antigen retrieval and subsequently cooled for 30 min. Slides were stained manually with sequential Tris buffer and water wash steps performed after each protocol step. Sections were incubated with avidin biotin two-step blocking solution (Vector SP-2001, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) to inhibit background staining and in 3% hydrogen peroxide to inhibit endogenous peroxidase. Non-serum protein block (Dako X909, DAKO) was applied to inhibit nonspecific protein binding. Immunostaining was performed using anti-human monoclonal catalase (1:1,600 dilution, Sigma C0979). Sections were examined using an Olympus BX61 photomicroscope (Olympus, Melville, NY) and photographed at 40 × magnification. Catalase staining was quantified by standardizing the thresholded intensity of micrographs with Image J software to determine the percent area stained for each slide (Abramoff et al. 2004).

Fluorometric analysis of H2O2 degradation by Tie2-hCat PUVECs

Metabolism of H2O2 in cultured PUVECs from Tie2-hCat and control endothelial cells was determined fluorometrically with a cell culture assay (Cayman Chemical Company, MI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, five PUVEC colonies (cloned non-Tie2-hCat, n = 1; Tie2-hCat -ve, n = 2; Tie2-hCat +ve, n = 2) were seeded at equal densities in quadruplicate in a 96-well plate and cultured for 24 h in complete M199 medium. Overlying medium (80 μL) was then transferred from the cultured cells to a 96-well black plate and combined with the reaction solution (20 uL) containing ADHP (10-acetyl-3,7-dihydroxyphenoxazine), a colorless, non-fluorescent reagent that reacts with H2O2 to produce the fluorescent product, resorufin. Resorufin fluorescence was read after 15 min (Ex: 530 nm Em: 590 nm) and expressed relative to cell density per well. An H2O2 standard curve was generated to verify the fluorescence detection range and linearity.

Data analysis

Data are presented as means ± SE. Differences between transgenic and control samples were assessed by using ANOVA or Student's t test where appropriate at a P < 0.05 level of significance (InStat, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

Tie2-hCat transgenic porcine fetal fibroblasts and cloned piglets

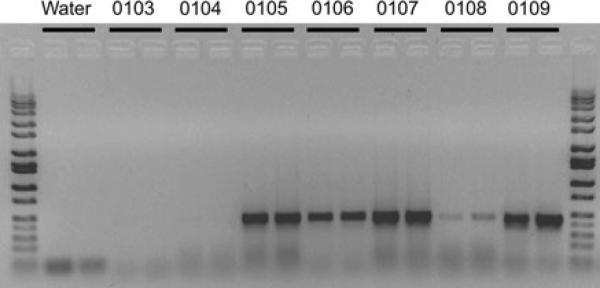

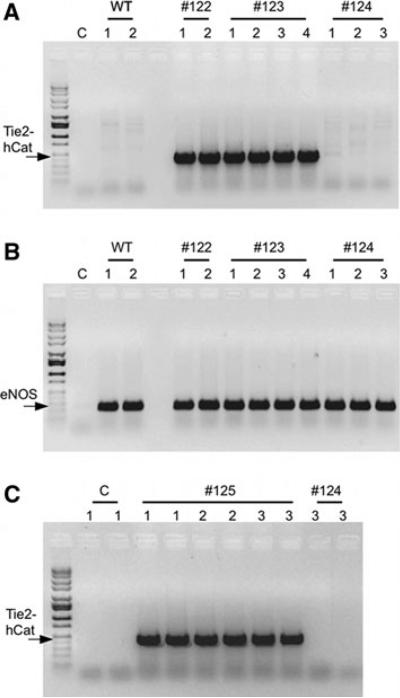

DNA sequencing verified the identity and fidelity of the purified Tie2-hCat construct used to produce transgenic fetal fibroblast colonies. Integration of the Tie2-hCat construct was detected in 10 of the 13 clonal fetal fibroblast populations (77%) as determined by PCR genotyping (Fig. 1). Of the three nuclear transfers conducted using clonal cell populations (Tie2-hCat positive derived from a single cell) and the one nuclear transfer conducted with a non-clonal cell population (mixture of 1,000 cells transfected with Tie2-hCat sorted into a single well based on eGPF fluorescence), all four surrogate sows yielded litters of cloned male Yucatan minipig offspring (Table 1). Genotyping by PCR for the presence of the Tie2-hCat transgene in ear snip genomic DNA revealed that cloned piglets from litter #122, #123 and #125 all had integrated Tie2-hCat DNA for a total of nine transgenic piglets (Fig. 2, panels A, C). The three piglets from litter #124 derived from the mixed (non-clonal) fibroblasts did not harbor the Tie2-hCat transgene based on PCR genotyping. All of the cloned piglets were positive for the eGFP transgene (data not shown). Repeat PCR confirmed the absence of the Tie2-hCat sequence in litter #124, and so these piglets were designated as eGFP positive age-matched controls. Postnatal examination of the cloned piglets revealed contracted tendons in the forelegs of three piglets (#123-3, #123-4 and #124-2), a phenotype observed previously in cloned pigs (Prather et al. 2004). Within 1 week of delivery, these three piglets died, and additional mortality was observed in piglets from all four litters (Table 1). Symptoms prior to death included rapid breathing, foam/mucus with blood around the snout, and clouded eyes in some individuals. These symptoms were observed in clones from all four litters, including the Tie2-hCat-negative litter #124. Total mortality reduced the number of cloned piglets from twelve to five, four of which carry the Tie2-hCat transgene (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

PCR genotyping of genomic DNA for the Tie2-hCat transgene in NIH Yucatan minipig fetal fibroblasts (470 bp PCR product). Selected clonal cell population IDs listed at top of gel over black bars indicate duplicate samples. Numbers 0104–0109 indicate specific clonal fibroblast populations collected by using FACS. Sample 0103: wild type porcine fibroblasts

Table 1.

Nuclear transfer and transgenic data for cloned male Yucatan minipig litters #122 to #125 derived from fetal fibroblasts co- transfected with Tie2-hCat (endothelial human catalase) and eGFP transgenes

| Litter ID #/sow | Transfected cells | Embryos transferred | Date of birth | Transgenic status | Extant piglets/original litter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| #122/O492 | Clonal | 142 | 03/16/09 | +Tie2-hCat (positive) | 1/2 |

| #123/O465 | Clonal | 140 | 03/16/09 | +Tie2-hCat (positive) | 1/4 |

| #124/O441 | Non-clonal | 150 | 03/16/09 | –Tie2-hCat (negative) | 1/3 |

| #125/O478 | Clonal | 126 | 03/30/09 | +Tie2-hCat (positive) | 2/3 |

Transgenic status of “positive” indicates the presence of the Tie2-hCat transgene as determined by PCR genotyping. All cloned piglets were eGFP positive

Fig. 2.

PCR genotyping of genomic DNA from cloned male Yucatan minipigs derived from fetal fibroblasts co-transfected with Tie2-hCat (endothelial human catalase) and eGFP transgenes. A Determination of Tie2-hCat PCR product (470 bp) in genomic DNA from individual control clones (WT; n = 2) and Tie2-hCat transfected clone litter numbers 122 (n = 2), 123 (n = 4) and 124 (n = 3). Lane “C” is the PCR no template control. B Endogenous control gene PCR product (eNOS; 237 bp) in identical genomic DNA samples from the same clones tested in panel A. C Tie2-hCat PCR product detection in duplicate samples from Tie2-hCat transfected clone litter 125 (n = 3) and clone #3 from litter 124 (PCR repeat)

Human catalase mRNA expression in Tie2-hCat PUVECs

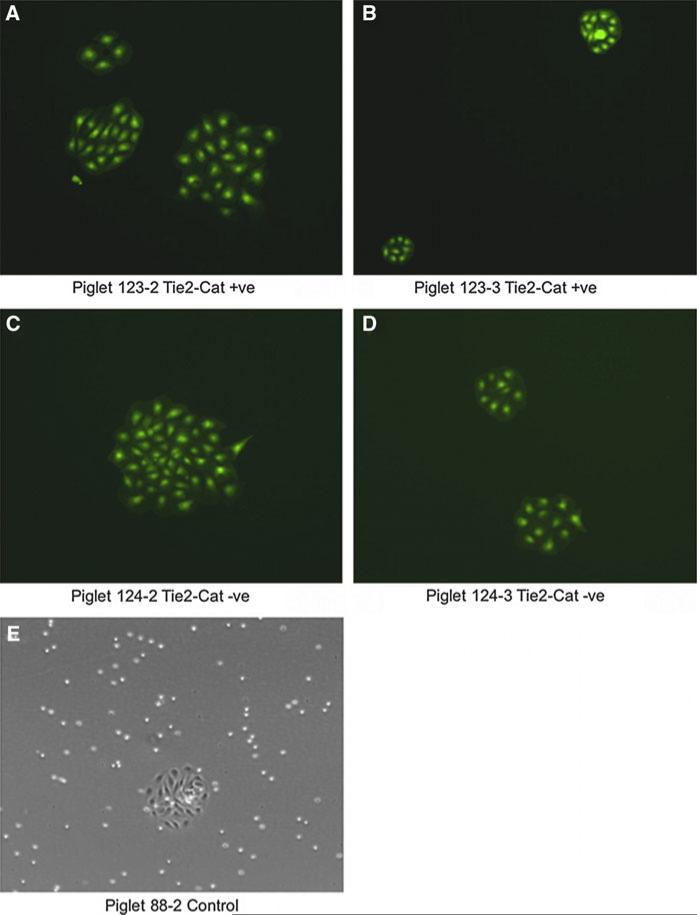

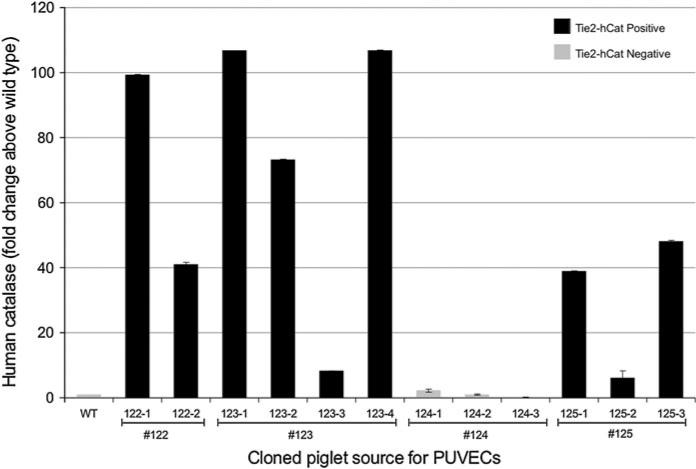

Primary cultures of endothelial cells derived from umbilical flushes of all twelve cloned Yucatan minipigs and two control cloned piglets revealed consistent endothelial morphology and visible eGFP expression in all Yucatan cultures (Fig. 3). Human catalase mRNA expression, as determined by RT–PCR, was evident in PUVECs designated as Tie2-hCat transgenic by PCR genotyping (Fig. 4). Expression of human catalase in endothelial cells among piglets was variable, but mean relative fold-expression (see below) of human catalase in piglets determined to carry the transgene (66.9 ± 10.1; n = 9) was significantly higher than control piglets (1.1 ± 0.1; n = 2) and piglets from litter #124 (1.2 ± 0.48; n = 3; ANOVA; P < 0.05). A “relative fold-expression” of one is defined as the absence of human catalase (2n where n = 0), indicating that there was no expression of the transgene in both control and litter #124 piglets. There was no significant difference in the mean relative fold-expression of human catalase among the three Tie2-hCat transgenic litters (ANOVA; P > 0.05). Aortic scrapes from two piglets that died in the first week, #122-2 (Tie2-hCat positive) and #124-2 (Tie2-hCat negative) had human catalase relative fold-expression levels of 313 ± 0.1 and 2.1 ± 0.25, respectively. Methodological RT–PCR controls (RNA extraction blank, no reverse transcriptase controls, and PCR no template controls) were all negative for the presence of RNA and genomic DNA for both human catalase and swine GAPDH.

Fig. 3.

Porcine umbilical vein endothelial cells (PUVECs) 24 h after isolation from cloned male Yucatan minipigs (panels A–D) and from control cloned piglet (panel E). Micrographs were taken at 10× magnification under UV fluorescence to visualize eGFP in Yucatan PUVECs and brightfield to visualize control clone PUVECs

Fig. 4.

RT–PCR expression analysis of the Tie2-hCat transgene in PUVECs from cloned swine. Primers are specific to human catalase and non-cross reactive with the orthologous porcine gene product. Individual cloned pigs are grouped by litter number (#122–#125) and human catalase mRNA is expressed relative to an age-matched clone not carrying the Tie2-hCat transgene (WT). Piglets from litters #122, #123 and #125 (black bars), but not litter #124 (grey bars), were determined to carry the Tie2-hCat transgene by PCR genotyping. Fold-change above WT was determined by the comparative Ct method (RT–PCR duplicate means ± standard deviation)

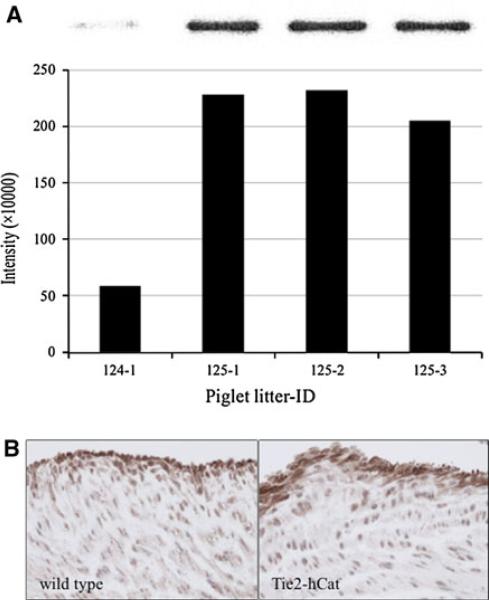

Western blot and immunohistochemical detection of catalase protein in Tie2-hCat piglets

As shown in Fig. 5A, western blot analysis of protein isolated from litter #124 (Tie2-hCat negative) versus litter #125 (Tie2-hCat positive) PUVECs indicated that catalase was present at a higher concentration in endothelial cells of the transgenic cloned piglets. Immunohistochemical analysis of umbilical vein sections from the cloned piglets with the same monoclonal antibody demonstrated increased catalase localized in the endothelial layer (Fig. 5B). In fact, quantification of contrast-enhanced intensity of catalase staining was determined to be greater in umbilical sections from Tie2-hCat transgenic piglets as compared to wild-type and litter #124 piglets.

Fig. 5.

Detection of catalase protein in cloned Yucatan minipigs carrying the Tie2-hCat transgene. A Western blot of protein from isolated PUVECs. Each lane represents protein in cells from individual piglets from litter #124 (non-Tie2-hCat) and litter #125 (Tie2-hCat). Catalase densitometry data are shown below the polyacrylamide gel image for each piglet. B Catalase immunoreactivity demonstrated in umbilical veins wild-type and Tie2-hCat cloned piglets. Data for wild-type pigs are presented on the left and for Tie2-hCat pigs on the right. Catalase immunoreactivity of the endothelial cells of each vein is displayed at 40× magnification. Micrographs are brightfield images of the umbilical vein endothelial layer

Catalytic degradation of hydrogen peroxide by Tie2-hCat PUVECs

The potential for transgenic human catalase to influence H2O2 concentrations in cultured PUVECs was estimated by using a cell-based assay (Table 2). The relative concentration of H2O2 in culture medium was significantly lower in PUVECs isolated from Tie2-hCat transgenic piglets from litters #123 and #125 as compared to PUVECs from piglets not carrying the human catalase transgene (ANOVA; P < 0.05). The concentration of H2O2 was approximately twofold lower in overlying medium from endothelial cells harvested from Tie2-hCat transgenic piglet #123-2 as compared to Tie2-hCat piglet #125-2 (Tukey–Kramer multiple comparisons test; P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Effect of Tie2-hCat transgene on H2O2 concentration in male cloned Yucatan minipig PUVECs

| PUVEC cell source | Transgenic status | Relative H2O2 concentration in culture medium (fluorescence) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Control PUVECsa | –Tie2-hCat (negative) | 637 ± 8 | A |

| Litter #124 (piglet 1) | –Tie2-hCat (negative) | 568 ± 20 | A |

| Litter #124 (piglet 2) | – Tie2-hCat (negative) | 642 ± 37 | A |

| Litter #125 (piglet 2) | +Tie2-hCat (positive) | 416 ± 17 | B |

| Litter #123 (piglet 2) | +Tie2-hCat (positive) | 167 ± 9 | C |

Estimated H2O2 concentration based on fluorescence intensity was measured at excitation and emission wavelengths of 528 and 620 nm, respectively. Data are presented as mean ± SE for cultured cell colonies seeded in quadruplicate wells (n = 4). Significant differences among groups is indicated by capital letters (ANOVA; P < 0.05)

PUVECs isolated from cloned Yucatan minipig not transfected with Tie2-hCat transgene. These cells are derived from a cloned piglet transgenic for eGFP

Discussion

Hydrogen peroxide has long been known as a toxic reactive oxygen species involved in cellular damage and disease (Yeldandi et al. 2000; Kawanishi et al. 2002; Hecquet and Malik 2009). In recent years, however, H2O2 at low endogenous concentrations in the endothelium has been recognized as an important signaling molecule in pathways related to cell survival and cardiovascular health (Veal et al. 2007; Thomas et al. 2008; Groeger et al. 2009). Improved animal models, such as transgenic swine that share close anatomical and physiological similarities to humans, will allow for controlled translational investigations of the vascular effects of H2O2. To this end, we have developed cloned Yucatan minipigs that carry a transgene overexpressing human catalase in the endothelium.

The optimized porcine fibroblast transfection and selection technique (Ross et al. 2010) used to generate these clones resulted in the presence of the Tie2-hCat transgene in greater than 75% of the clonal fibroblast populations genotyped. The efficiency of this screening technique markedly reduced the time in culture for the fibroblasts, a factor known to influence chromosomal condition and the success of SCNT (Mastromonaco et al. 2006). The low passage number for the Tie2-hCat transgenic cells used for SCNT may have contributed to the successful production of viable cloned litters from each of the four sows used in this study. Cloning from fibroblast colonies derived from individual transfected cells sorted by FACS proved important. Cloned piglets derived from multiple cells co-transfected with eGFP and Tie2-hCat and then seeded by FACS into a single well did not yield piglets with the catalase transgene, indicating that a large number of cells that were eGFP positive did not integrate Tie2-hCat. Single cell derived populations required additional time to grow, but once genotyped, provided confirmation of a uniformly transgenic population. A total of twelve cloned piglets from four litters were obtained, nine of which were positive for Tie2-hCat genotype. More than half of the piglets were lost to illness in the first week after birth. The cause of the mortality is undetermined, but did not appear to be related to Tie2-hCat, as two of the cloned piglets affected did not carry the transgene. Abnormalities in cloned offspring, including compromised immune function (Carroll et al. 2005), are not uncommon, and are generally not transmitted to the next generation, likely because the proper DNA methylation pattern of the genome is reestablished during gametogenesis (Prather et al. 2004).

Human catalase mRNA was present in the endothelial cells of the Tie2-hCat transgenic piglets, as was a general increase in catalase protein. Due to cross-reactivity of the human catalase antibody with endogenous swine catalase, the transgenic nature of the increase in catalase protein could not be wholly confirmed. However, the specificity of the RT–PCR for human catalase mRNA suggests that the increase in catalase protein is due to the presence of the human transgenic transcript. A similar increase in non-specific catalase protein was reported in the Tie2-hCat mouse model, where a polyclonal catalase antibody was used for western blot and immunohistochemical analysis (Suvorava et al. 2005). Our immunohistochemical observations in the pig confirm that antibody binding was generally confined to the endothelium. Although the Tie2 regulatory element is also present in hematopoietic tissue (De Palma et al. 2005), non-vascular expression was not present in the Tie2-hCat mouse model based on measurement of equal amounts of catalase protein expression in bone marrow mononuclear cells from wild-type and transgenic mice (Suvorava and Kojda 2009). The metabolic activity of the transgenic human catalase in swine was inferred based on significantly reduced levels of H2O2 in Tie2-hCat PUVECs relative to those not carrying the transgene. Future production of a stable population of Tie2-hCat transgenic swine by selective breeding will enable more detailed study of human catalase expression and activity in isolated pig vessels.

Transgenic swine that overexpress human catalase in the endothelium may provide a significant step forward in our understanding of the role of endothelium-derived H2O2 in vascular regulation, but it is important to note potential limitations of our current animal model. We do not yet know the degree of human catalase expression in the endothelium of intact vessels from living Tie2-hCat swine. It is encouraging that human catalase mRNA and overall elevated catalase protein were evident in excised vessels from transgenic piglets that died during the first week after cesarian section, but it is not known to what degree the physiological stress leading to the death of these piglets, or the underlying cause of this mortality, may have influenced transgene expression. The mouse model of human catalase expression revealed significant inhibition of eNOS upregulation in the aorta and left ventricular arterioles compared to wild-type mice following exercise training. Similar training studies using the pig model presented herein are warranted to definitively elucidate the role of H2O2 in endothelial adaptations to exercise training. It should also be noted that catalase is only one of several enzymes involved in H2O2 regulation. Cells also control H2O2 via myeloperoxidase and 2-Cys peroxiredoxins (Wood et al. 2003; Klebanoff 2005). The downstream effects of overexpression of (human) catalase in swine should be examined in conjunction with other regulation pathways in order to determine the significance of catalase and H2O2 in vascular health. Whole organism studies will permit a more integrated assessment of Tie2-hCat transgene effect. Controlled breeding of Tie2-hCat transgenic pigs to generate a larger study population will enable experiments in anesthetized, instrumented pigs to evaluate the control of coronary blood flow and vascular responses as routinely performed in cardiovascular swine research (Laughlin et al. 2001; Griffin et al. 2001; Bender et al. 2010). Isolated conduit arteries and arterioles from Tie2-hCat pigs can also be examined for alteration in vasomotor control mechanisms attendant to the decrease in endothelium-derived H2O2. Because the Tie2-hCat transgene in these pigs and the mouse (Lauer et al. 2005) are the same, a comparison of these two models could highlight species-specific benefits and differences. These pigs have been deposited into the National Swine Resource and Research Center (NSRRC:0021 Tie2-Catalase; http:\www.nsrrc.missouri.edu) and are available for distribution to interested investigators. In summary, the production of cloned Yucatan minipigs that express human catalase will support efforts to isolate the role of endothelium-derived H2O2 as a vascular signaling molecule by providing a suitable model for translational cardiovascular studies.

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by a grant from the NIH (R24 RR018276-05) to MHL and RSP. The Tie2-hCat plasmid was kindly provided by Dr. George Kojda and Thao-Vi Dao of the Institut für Pharmakologie und Klinische Pharmakologie, Heinrich-Heine-Universität, Düsseldorf, Germany. Members of the R. S. Prather Lab were particularly helpful: Dr. Clay Isom, August Rieke, Dr. Jason Ross, Lee Spate, Dave Wax, and Dr. Jianguo Zhao. We are grateful for the assistance provided by members of the M. H. Laughlin Lab, including Jennifer Casati, David Harah, Dr. Rick McAllister, Ann Melloh, and Pam Thorne. We also thank Joyce Carafa of the MU Immunology and Cytology Core who assisted with FACS.

Contributor Information

J. J. Whyte, Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA

M. Samuel, Division of Animal Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA National Swine Resource and Research Center, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA.

E. Mahan, Division of Animal Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA

J. Padilla, Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA

G. H. Simmons, Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA

A. A. Arce-Esquivel, Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA

S. B. Bender, Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA

K. M. Whitworth, Division of Animal Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA

Y. H. Hao, Division of Animal Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA

C. N. Murphy, Division of Animal Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA

E. M. Walters, Division of Animal Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA National Swine Resource and Research Center, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA.

R. S. Prather, Division of Animal Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA National Swine Resource and Research Center, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA.

M. H. Laughlin, Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA

References

- Abramoff M, Magelhaes P, Ram S. Image processing with Image J. Biophtonics International. 2004;11:36–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ammerschlaeger M, Beigel J, Klein K, Mueller SO. Characterization of the species-specificity of peroxisome proliferators in rat and human hepatocytes. Toxicol Sci. 2004;78:229–240. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfh071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ardanaz N, Pagano PJ. Hydrogen peroxide as a paracrine vascular mediator: regulation and signaling leading to dysfunction. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2006;231:237–251. doi: 10.1177/153537020623100302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aris A, Benali S, Ouellet A, Moutquin JM, Leblanc S. Potential biomarkers of preeclampsia: inverse correlation between hydrogen peroxide and nitric oxide early in maternal circulation and at Term in placenta of women with preeclampsia. Placenta. 2009;30:342–437. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudin B, Bruneel A, Bosselut N, Vaubourdolle M. A protocol for isolation and culture of human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:481–485. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bender SB, Houwelingen MJ van, Merkus D, Duncker DJ, Laughlin MH. Quantitative analysis of exercise-induced enhancement of early- and late-systolic retrograde coronary blood flow. J Appl Physiol (Bethesda, Md.: 1985) 2010;108:507–514. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01096.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodiga S, Gruenloh SK, Gao Y, Manthati VL, Dubasi N, Falck JR, Medhora MM, Jacobs ER. 20-HETE-induced nitric oxide production in pulmonary artery endothelial cells is mediated by NADPH oxidase, H2O2, and PI3-kinase/Akt. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;289:L564–L574. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00298.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capettini LSA, Cortes SF, Gomes MA, Silva GAB, Pesquero JL, Lopes MJ, Teixeira MM, Lemos VS. Neuronal nitric oxide synthase-derived hydrogen peroxide is a major endothelium-dependent relaxing factor. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;295:H2503–H2511. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00731.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll JA, Carter DB, Korte SW, Prather RS. Evaluation of the acute phase response in cloned pigs following a lipopolysaccharide challenge. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2005;29:564–572. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AR, Lyon CJ, Xia X, Liu JZ, Tangirala RK, Yin F, Boyadjian R, Bikineyeva A, Praticò D, Harrison DG, Hsueh WA. Age-accelerated atherosclerosis correlates with failure to upregulate antioxidant genes. Circ Res. 2009;104:e42–e54. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.188771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Palma M, Venneri MA, Galli R, Sergi Sergi L, Politi LS, Sampaolesi M, Naldini L. Tie2 identifies a hematopoietic lineage of proangiogenic monocytes required for tumor vessel formation and a mesenchymal population of pericyte progenitors. Cancer Cell. 2005;8:211–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong D, Yue P, Yang B, Wang W. Hydrogen peroxide stimulates the Ca(2+)-activated big-conductance K channels (BK) through cGMP signaling pathway in cultured human endothelial cells. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2008;22:119–126. doi: 10.1159/000149789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drouin A, Thorin E. Flow-induced dilation is mediated by Akt-dependent activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase-derived hydrogen peroxide in mouse cerebral arteries. Stroke. 2009;40:1827–1833. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.536805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin KL, Woodman CR, Price EM, Laughlin MH, Parker JL. Endothelium-mediated relaxation of porcine collateral-dependent arterioles is improved by exercise training. Circulation. 2001;104:1393–1398. doi: 10.1161/hc3601.094274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groeger G, Quiney C, Cotter TG. Hydrogen peroxide as a cell-survival signaling molecule. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:2655–2671. doi: 10.1089/ars.2009.2728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecquet CM, Malik AB. Role of H(2)O(2)-activated TRPM2 calcium channel in oxidant-induced endothelial injury. Thromb Haemost. 2009;101:619–625. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homma H, Takahashi T, Seki H, Ohtani M, Kondoh T, Fukuda M. Immunohistochemical localization of inducible nitric oxide synthase in synovial tissue of human temporomandibular joints with internal derangement. Arch Oral Biol. 2001;46:93–97. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9969(00)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawanishi S, Hiraku Y, Murata M, Oikawa S. The role of metals in site-specific DNA damage with reference to carcinogenesis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:822–832. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00779-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klebanoff SJ. Myeloperoxidase: friend and foe. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:598–625. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1204697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Sun X, Wiseman DA, Tian J, Umapathy NS, Verin AD, Black SM. Hydrogen peroxide decreases endothelial nitric oxide synthase promoter activity through the inhibition of Sp1 activity. DNA Cell Biol. 2009;28:119–129. doi: 10.1089/dna.2008.0775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai L, Prather RS. Production of cloned pigs by using somatic cells as donors. Cloning Stem Cells. 2003;5:233–241. doi: 10.1089/153623003772032754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauer N, Suvorava T, Ruther U, Jacob R, Meyer W, Harrison DG, Kojda G. Critical involvement of hydrogen peroxide in exercise-induced up-regulation of endothelial NO synthase. Cardiovasc Res. 2005;65:254–262. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2004.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin MH, Pollock JS, Amann JF, Hollis ML, Woodman CR, Price EM. Training induces nonuniform increases in eNOS content along the coronary arterial tree. J Appl Physiol. 2001;90:501–510. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.90.2.501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luksha L, Nisell H, Luksha N, Kublickas M, Hultenby K, Kublickiene K. Endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor in preeclampsia: heterogeneous contribution, mechanisms, and morphological prerequisites. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R510–R519. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00458.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvar PJ, Hammer LW, Boegehold MA. Hydrogen peroxide-dependent arteriolar dilation in contracting muscle of rats fed normal and high salt diets. Microcirculation. 2007;14:779–791. doi: 10.1080/10739680701444057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastromonaco GF, Perrault SD, Betts DH, King WA. Role of chromosome stability and telomere length in the production of viable cell lines for somatic cell nuclear transfer. BMC Dev Biol. 2006;6:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-6-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister RM, Albarracin I, Price EM, Smith TK, Turk JR, Wyatt KD. Thyroid status and nitric oxide in rat arterial vessels. J Endocrinol. 2005;185:111–119. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.06022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mink SN, Kasian K, Santos Martinez LE, Jacobs H, Bose R, Cheng Z, Light RB. Lysozyme, a mediator of sepsis that produces vasodilation by hydrogen peroxide signaling in an arterial preparation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H1724–H1735. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01072.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prather RS, Sutovsky P, Green JA. Nuclear remodeling and reprogramming in transgenic pig production. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2004;229:1120–1126. doi: 10.1177/153537020422901106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross JW, Whyte JJ, Zhao J, Samuel M, Wells KD, Prather RS. Optimization of square-wave electroporation for transfection of porcine fetal fibroblasts. Transgenic Res. 2010;19:611–620. doi: 10.1007/s11248-009-9345-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samora JB, Frisbee JC, Boegehold MA. Hydrogen peroxide emerges as a regulator of tone in skeletal muscle arterioles during juvenile growth. Microcirculation. 2008;15:151–161. doi: 10.1080/10739680701508497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlaeger TM, Bartunkova S, Lawitts JA, Teichmann G, Risau W, Deutsch U, Sato TN. Uniform vascular-endothelial-cell-specific gene expression in both embryonic and adult transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3058–3063. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative CT method. Nat Protocols. 2008;3:1101–1108. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Searles CD. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase expression. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;291:C803–C816. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00457.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seegar TCM, Eller B, Tzvetkova-Robev D, Kolev MV, Henderson SC, Nikolov DB, Barton WA. Tie1-Tie2 interactions mediate functional differences between angiopoietin ligands. Mol Cell. 2010;37:643–655. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu S, Hiroi T, Ishii M, Hagiwara T, Wajima T, Miyazaki A, Kiuchi Y. Hydrogen peroxide stimulates tetrahydrobiopterin synthesis through activation of the Jak2 tyrosine kinase pathway in vascular endothelial cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:755–765. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sindler AL, Delp MD, Reyes R, Wu G, Muller-Delp JM. Effects of ageing and exercise training on eNOS uncoupling in skeletal muscle resistance arterioles. J Physiol (Lond) 2009;587:3885–3897. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.172221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suvorava T, Kojda G. Reactive oxygen species as cardiovascular mediators: lessons from endothelial-specific protein overexpression mouse models. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1787:802–810. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suvorava T, Lauer N, Kumpf S, Jacob R, Meyer W, Kojda G. Endogenous vascular hydrogen peroxide regulates arteriolar tension in vivo. Circulation. 2005;112:2487–2495. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.543157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thengchaisri N, Shipley R, Ren Y, Parker J, Kuo L. Exercise training restores coronary arteriolar dilation to NOS activation distal to coronary artery occlusion: role of hydrogen peroxide. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2007;27:791–798. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000258416.47953.9a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S, Kotamraju S, Zielonka J, Harder DR, Kalyanaraman B. Hydrogen peroxide induces nitric oxide and proteosome activity in endothelial cells: a bell-shaped signaling response. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;42:1049–1061. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SR, Witting PK, Drummond GR. Redox control of endothelial function and dysfunction: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:1713–1765. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turk JR, Laughlin MH. Physical activity and atherosclerosis: which animal model? Can J Appl Physiol. 2004;29:657–683. doi: 10.1139/h04-042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veal EA, Day AM, Morgan BA. Hydrogen peroxide sensing and signaling. Mol Cell. 2007;26:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vodicka P, Smetana K, Dvoránková B, Emerick T, Xu YZ, Ourednik J, Ourednik V, Motlík J. The miniature pig as an animal model in biomedical research. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1049:161–171. doi: 10.1196/annals.1334.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitworth KM, Li R, Spate LD, Wax DM, Rieke A, Whyte JJ, Manandhar G, Sutovsky M, Green JA, Sutovsky P, Prather RS. Method of oocyte activation affects cloning efficiency in pigs. Mol Reprod Dev. 2009;76:490–500. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood ZA, Poole LB, Karplus PA. Peroxiredoxin evolution and the regulation of hydrogen peroxide signaling. Science. 2003;300:650–653. doi: 10.1126/science.1080405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yada T, Shimokawa H, Hiramatsu O, Shinozaki Y, Mori H, Goto M, Ogasawara Y, Kajiya F. Important role of endogenous hydrogen peroxide in pacing-induced metabolic coronary vasodilation in dogs in vivo. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:1272–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeldandi AV, Rao MS, Reddy JK. Hydrogen peroxide generation in peroxisome proliferator-induced oncogenesis. Mutat Res. 2000;448:159–177. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(99)00234-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Ross JW, Hao Y, Spate LD, Walters EM, Samuel MS, Rieke A, Murphy CN, Prather RS. Significant improvement in cloning efficiency of an inbred miniature pig by histone deacetylase inhibitor treatment after somatic cell nuclear transfer. Biol Reprod. 2009;81:525–530. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.077016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Rodriguez-Porcel M, Bentley MD, Chade AR, Sica V, Napoli C, Caplice N, Ritman EL, Lerman A, Lerman LO. Antioxidant intervention attenuates myocardial neovascularization in hypercholesterolemia. Circulation. 2004;109:2109–2115. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000125742.65841.8B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]