Abstract

Although ozone enhances leukocyte function and recruitment in airways, the direct effect of ozone in modulating structural cell-derived inflammatory mediators remains unknown. Using a coculture model comprised of differentiated human airway epithelial cells (NHBE) and smooth muscle cells (ASM), we postulate that ozone regulates IL-6 secretion in basal and cytokine-primed structural cells. Air-liquid interface (ALI) cultures of NHBE cells underwent differentiation as determined by mucin secretion, transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER), and ultrastructure parameters. Whereas TNF enhanced basal secretion of IL-6 (57 ± 3%), ozone exposure at 0.6 ppm for 6 h augmented IL-6 levels in basal (41 ± 3%) and TNF- (50 ± 5%) primed cocultures compared with that derived from NHBE or ASM monolayers alone. Levels of PGE2, 6-keto-PGF1α, PGF2α, and thromboxane B2 (TxB2) levels in basal and TNF-primed cocultures revealed that ozone selectively enhanced PGE2 production in TNF- (6 ± 3-fold) primed cocultures, with little effect (P > 0.05) on diluent-treated cultures. In accordance with ozone-induced increases in PGE2 levels, cyclooxygenase inhibition with indomethacin partially abolished IL-6 secretion. Surprisingly, indomethacin had little effect on constitutive secretion of IL-6 in cocultures, whereas indomethacin completely restored ozone-mediated TEER reduction in TNF-primed cocultures. Collectively, our data for the first time suggest a dual role of ozone in modulating IL-6 secretion and TEER outcomes in a PGE2-dependent (in presence of TNF stimulus) and -independent manner (in absence of cytokine stimulus).

Keywords: asthma, airway remodeling, inflammation, cytokines, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), airway inflammation modulates IL-6 expression (16, 19). Evidence suggests that ozone enhances IL-6 secretion in a variety of rodent models (55, 61). After ozone exposure, both airway epithelial cells and macrophages secrete IL-6, and IL-6 deficiency reduces ozone-induced airway neutrophilia (7, 18, 31). In murine studies, overexpression of IL-6 ameliorates chronic hyperoxia-induced lung injury (62). Based on reduced acute-phase responses to lung injury in IL-6-deficient mice, others suggest a protective role of IL-6 (38). Together, these studies indicate a role of IL-6 in modulating ozone-induced lung inflammation and injury.

PGs play important roles as mediators and biomarkers of lung inflammation (47). In addition to modulating airway smooth muscle (ASM) cell spasmogenic effects, PGs also stimulate proinflammatory cytokine secretion by lung epithelial and immune cells (32). In human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cells, PGs enhance the expression of IL-8 and GM-CSF, which then induce chemotaxis of macrophages and Th2 cells (12). In bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid of subjects exposed to ozone, elevated levels of eicosanoids are associated with increases in IL-6 levels. In parallel, murine studies have shown that IL-6 secretion in vivo is sensitive to cyclooxygenase (COX) inhibition with indomethacin.

Ozone inhalation enhances immune cell influx and inflammatory mediator secretion into BAL fluid. Although airway structural cells are among the primary cell types exposed to ozone, subsequently trafficking immune cells play an important role in altering ASM shortening and promoting secretion of chemokines and cytokines (53). Evidence suggests that ozone effects on epithelial cell-derived mediator production are dose- and time-dependent (1). Alterations in production of such mediators could thus modulate trafficking and activation of leukocytes (41). In an effort to study the overall effects of ozone in mediating synthetic responses in airway structural cells, we characterized a coculture system comprised of NHBE and ASM cells. As inflammatory cell-derived mediators are an early and integral part of ozone-mediated responses, we studied the differential effects of ozone in modulating structural cell-derived IL-6 secretion in the presence and absence of cytokine stimulus. To determine whether changes in the eicosanoid profile modulate IL-6 secretion, liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS) analysis of different COX products/metabolites [PGE2, PGD2, 6-keto-PGF1α (the hydrolysis product of PGI2), PGF2α, and thromboxane B2 (TxB2)] was performed. We then investigated whether COX inhibition of ozone-mediated PGs modulates IL-6 secretion and epithelial intracellular tight-junction integrity. Collectively, these data elucidate molecular interactions regulating ozone-induced alterations in airway structural cell function and identify novel therapeutic targets to attenuate ozone-induced asthma and COPD exacerbations.

METHODS

Cell Culture

ASM cultures.

Human ASM cells were isolated from lung transplant donors in accordance with the protocols approved by the University of Pennsylvania Committee on Studies Involving Human Beings. Following isolation, ASM cells were cultured in Ham's F-12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/ml penicillin, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin, and 2.5 μg/ml amphotericin B (GIBCO BRL Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and seeded uniformly onto 12-well tissue culture plates.

NHBE cultures.

Frozen NHBE cells were obtained commercially from Lonza (Basel, Switzerland) and cultured in collagen-1-coated T-75 flasks using recommended media and supplements [bronchial epithelial cell growth medium (BEGM)] at 37°C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. At 80–85% confluency, the cells were detached with 0.1% trypsin-EDTA and seeded at densities of 3 × 105 cells/cm2 on collagen-1-coated Transwell inserts. Both apical (0.5 ml) and basolateral sides (1.5 ml) were filled with BEGM:F-12 (50:50) media supplemented with 0.1% BSA, hydrocortisone (0.5 μg/ml), insulin (5 μg/ml), transferrin (10 μg/ml), epinephrine (0.5 μg/ml), triiodothyronine (6.5 μg/ml), gentamicin (50 μg/ml), amphotericin B (50 μg/ml), retinoic acid (0.1 ng/ml), and epidermal growth factor (0.5 ng/ml human recombinant; Lonza). Following the formation of NHBE monolayers, the apical surfaces of the Transwell inserts were exposed to ambient conditions, and the medium on the basolateral side was changed every 24 h throughout the culture period.

NHBE-ASM cocultures.

For experiments using the coculture model, Transwell inserts containing differentiated NHBE monolayers [12–14 days after air-liquid interface (ALI)] were rinsed twice in sterile Dulbecco's PBS (DPBS) and suspended onto 12-well plates containing confluent cultures of ASM cells. In this configuration, the NHBE-ASM cocultures were incubated in 0.1% BSA-F-12 media (devoid of hydrocortisone or dexamethasone) for 24 h. Control experiments consisted of individual NHBE and ASM tissues cultured following the same seeding, culturing, and starvation protocols.

Electron microscopy of NHBE cultures.

NHBE cells on Transwell inserts were fixed in 3% glutaraldehyde overnight at 4°C. Cells were rinsed in cacodylate buffer for 1 h at room temperature and post-fixed in 1.25% osmium tetroxide (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Forth Washington, PA) for an additional hour. After rinsing in 15% ethanol, cells were stained in 4% aqueous uranyl acetate, and preparations were dehydrated through graded ethanols and embedded in Poly/Bed 812 (Electron Microscopy Sciences). Tissues were thin-sectioned, post-stained in uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and viewed on a Zeiss 902 electron microscope.

Assay of mucin secretion.

To ascertain differentiation of NHBE cultures, ALI quantification of mucin secretion was performed at various time points. Serially diluted apical washings from NHBE monolayers were coated onto 96-well plates and dried overnight. Following incubation, the coated plates were blocked in 1.5% BSA and incubated for 2 h with 1:2,000 dilution of 17Q2 mouse monoclonal antibody (Ab) (Covance Biotechnology, Berkeley, CA). After two successive washes in DPBS, the plates were incubated in 1:200 dilution of rat anti-mouse horseradish peroxidase (HRP) secondary Ab for 1 h. The plates were read at 450 nm following incubation with tetramethyl benzidine (TMD) substrate. The absorbance values on day 6 were arbitrarily set at 1, and the results are expressed as fold increase in mucin secretion over time.

Transepithelial electrical resistance measurements.

The confluence of epithelial monolayer and the integrity of intercellular tight junction is measured by transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER). In our studies, TEER values across the NHBE monolayers were measured daily using an EVOM device (WPI, Sarasota, FL) and were adjusted by subtracting the background resistance contributed by the Transwell insert and medium.

Ozone generation and flow rate kinetics.

The ozone exposure incubator for tissue culture was extensively characterized to deliver and maintain ozone concentrations during routine operation. Our optimization protocol consisted of two parts: 1) development of a mathematical mass-balance model to describe steady-state concentrations of ozone, CO2, and humidity and the volumetric flow rates required to maintain these concentrations; and 2) kinetic studies to assess the rate of ozone decay and turnover dynamics. The relevant mathematical models for steady-state operation were addressed by mole-balance equations encompassing CO2, ozone, water vapor, and total flow components through the system.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

Here, F represents the volumetric flows, y the concentrations, r(yO3) the decomposition rate of ozone, and V the volume of the system. Kinetic studies were performed by empirical model identification tests using the dynamic model for ozone concentrations

|

(5) |

where decay of ozone was assumed to follow pseudo first-order kinetics, and k is the rate constant. A fit of empirical ozone concentration vs. time data to the solution to Eq. 5 yielded information about the decay rate (half-life) of ozone in the system.

Assay of cytokine secretion by ELISA.

Confluent cultures of ASM in 12-well plates and NHBE cultures on Transwell inserts were growth-arrested by incubating in F-12 medium with 0.1% BSA for 24 h and stimulated with 10 ng/ml TNF-α for an additional 24 h. For experiments involving NHBE-ASM cocultures, TNF was added at the apical surface, and cytokine secretion was assayed in the basolateral media 24 h post-TNF treatment.

To investigate the effect of ozone on TNF-induced chemokine secretion, all cultures were treated with or without TNF at 10 ng/ml and exposed to 0.6 ppm of ozone for a period of 6 h at 37°C in a 5% CO2-rich incubator. Following ozone exposure, the cultures were reincubated for an additional 18 h in a 5% CO2 incubator. The basolateral media was collected following this period and cytokine assayed by using specific DuoSet Kits (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). For analysis of prostanoids, the supernatants were collected immediately after ozone exposure and frozen at −80°C until LC/MS analysis.

Quantitative estimation of eicosanoids by UHPLC/MS.

Quantitation was performed by ultra high-pressure liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC/MS) using solid-phase extraction (SPE), negative ion electrospray introduction, and selected reaction monitoring techniques (57). Tetradeuterated analogs of PGD2, PGE2, PGF2α, 6-keto-PGF1α, and TxB2 (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI), 5 ng each, were added to 1.0 ml of cell culture medium. The methoxime (MO) derivative was formed by adding 0.5 ml methoxyamine HCl (1 g/ml) in water, and eicosanoids were extracted on StrataX SPE cartridges (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA) and dissolved in 200 μl of 20% acetonitrile. The analysis of eicosanoids was performed on a Quantum Ultra Mass Spectrometer interfaced to an Accela UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Fremont, CA) using 200-mm × 2.1-mm × 1.9-μm Hypersil GOLD columns (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Mobile phases were generated from A) HPLC-grade water, and B) 5% methanol-95% acetonitrile, both containing 0.005% acetic acid adjusted to pH 5.7 with ammonium hydroxide. The flow rates used were 350 μl/min using a segmented linear gradient starting at 20% (t = 0), ramping to 35% B (t = 15 s), to 40% B (t = 16 s), and then to 70% B (t = 23 s). The transitions were monitored at mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) 384 → 272 [Dinoprostone (d4)-PGD2 MO and d4-PGE2 MO], m/z 380 → 268 (PGD2 MO and PGE2 MO), m/z 357 → 197 (d4-PGF2α), m/z 353 → 193 (PGF2α), m/z 402 → 173 (d4-TxB2 MO), m/z 398 → 169 (TxB2 MO), m/z 402 → 372 (d4-6-keto-PGF1α MO), and m/z 398 → 368 (6-keto-PGF1α MO). The collision gas was argon (1.5 mTorr), and collision energy was 18 V for PGD2, PGE2, 6-keto-PGF1α, and TxB2 and 24 V for PGF2α. Source offset was set at 5 V, and quantitation was performed by peak-area ratios.

Statistics

All data are expressed as means ± SE. Ozone-mediated changes in eicosanoids and cytokines were analyzed using a two-way ANOVA. A P value of 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Epithelial Ultrastructure and TEER Measurements

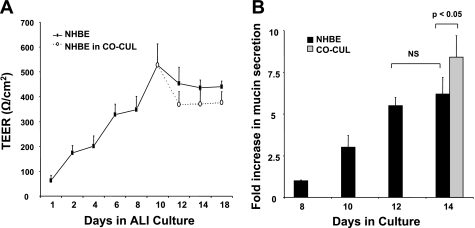

Cultured bronchial epithelial cells differentiate into a physiologically relevant phenotype characterized by the presence of ciliated, basal, and secretory cells (25, 36). Differentiated epithelium is the progressively expressed structural proteins such as occludin, junctional adhesion molecules responsible for formation of intercellular tight junctions (4). NHBE monolayers at ALI for 14 days manifested a heterogeneous population of ciliated and secretory cells. TEER values increased with the growth of epithelial monolayers. Background electrical resistance remained consistently low (25 Ω·cm2). After raising the cultures to ALI, TEER values proportionally increased from 75 ± 15 to 320 ± 40 Ω·cm2 from day 1 to maximal values of 520 ± 90 Ω·cm2 observed on day 10. Between days 12 and 18, TEER values in NHBE cultures remained constant. Superimposing NHBE cells onto ASM cultures after day 10 showed no significant changes in TEER compared with cultured NHBE monolayers.

NHBE Differentiation and Mucin Secretion

Airway mucin secretion was determined in the apical washings of epithelium between 8 and 18 days after exposure to ALI. As shown in Fig. 1, compared with mucin secretion on day 8, mucin secretion steadily increased by 3.1 ± 0.7-fold to 5.5 ± 0.4-fold on days 10 and 12, respectively. Maximal secretion of 6.2 ± 1-fold was detected on day 14. Overlaying the Transwell inserts onto ASM cultures on day 14 showed a marginal increase in mucin secretions. These data further confirm the evolvement of NHBE-ASM cultures to a differentiated and mucus-secreting phenotype between 10 and 14 days post-ALI.

Fig. 1.

Normal human bronchial epithelial (NHBE) cell differentiation parameters in air-liquid interface (ALI) cultures. A: transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) measurements across NHBE monolayers at ALIs for 18 days (n = 6). Solid lines indicate TEER values across NHBE monolayers in singular cultures of NHBE cells alone. Dotted lines indicate TEER values across NHBE monolayers in NHBE-airway smooth muscle (ASM) cell coculture setup (CO-CUL). B: assessment of NHBE monolayer apical mucin secretion by ELISA. Data represent means ± SE from 3 separate experiments done in triplicate. Statistical evaluation was performed by ANOVA. P > 0.05, significant difference. NS, no significant change.

Characterization of Response to Ozone Exposure

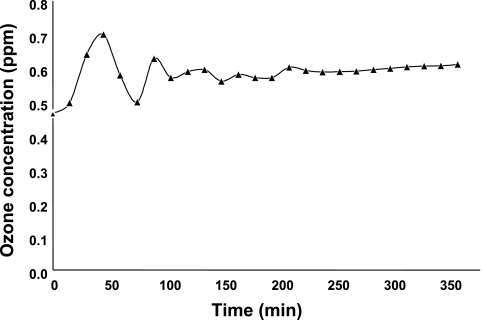

Studies were performed to evaluate the validity and reliability of exposing NHBE-ASM cocultures to ozone. As shown in Fig. 2, the mean and median ozone concentrations throughout the 6-h exposure protocol were ∼0.59 ppm. In addition, kinetic studies revealed an ozone decay half-life, t = 90 ± 15 min at >10% humidity, consistent with available standards for the decay of ozone under ambient atmospheric conditions. We also observed significantly faster ozone decay rates, t = 35 ± 15 min at >75% humidity, that were attributed to -OH free radicals obtained from ozone interaction with water vapor contributing to ozone destruction, such that the decrease in half-life with increasing humidity was expected. Accordingly, the ozone decay rate increased dramatically at >90% humidity, likely due to the persistence of water droplets from the humidifier. During our ozone exposure protocols, humidity levels were meticulously adjusted to attain the desired ozone levels. Collectively, these data suggest that the delivery and maintenance of ozone levels were constant over the time course used in the ozone experiments.

Fig. 2.

Evaluation of ozone concentrations in experiments (parts per million) as a function of time (minutes).

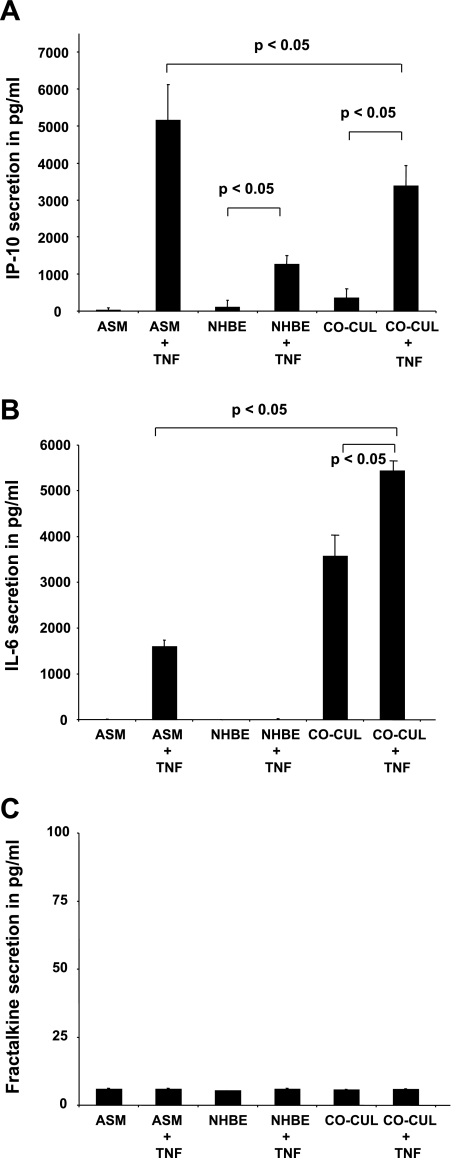

Differential Cytokine Secretion in NHBE-ASM Cocultures

As shown in Fig. 3, A and B, basolateral secretion from NHBE-ASM cocultures synergistically increased basal IL-6 levels over constitutive secretion from ASM (3,370 ± 500 pg/ml) and NHBE (3,400 ± 470 pg/ml) monolayers alone. Similarly, inducible protein 10 (IP-10) secretion in basolateral media from unstimulated cocultures increased over that induced in ASM (260 ± 50 pg/ml) and NHBE (200 ± 15 pg/ml) cultures alone.

Fig. 3.

Synthetic responses in basal and TNF-stimulated NHBE-ASM cocultures and in NHBE and ASM cells cultured alone. ELISAs were performed for inducible protein 10 (IP-10) secretion (A), IL-6 secretion (B), and fractalkine secretion (C) in ASM, NHBE, and NHBE-ASM cocultures from basolateral media following apical instillation of vehicle or TNF (10 ng/ml) for 24 h. Summarization of 3 separate experiments performed in triplicate. Data represent means ± SE from 3 separate experiments done in triplicate. Statistical evaluation was performed by ANOVA. P > 0.05, significant difference.

Treatment of ASM cells alone with TNF increased IL-6 and IP-10 levels to 1,550 ± 200 pg/ml and 5,100 ± 1,000 pg/ml over vehicle-treated monolayers. Stimulation of NHBE monolayers alone also showed an enhanced IP-10 (1,400 ± 200 pg/ml) secretion with no perceivable changes (P > 0.05) in IL-6 levels. In parallel, we next investigated the effects of TNF in modulating cytokine secretion in cocultures. After TNF treatment, both IL-6 (2,000 pg/ml, 50 ± 5%) and IP-10 (3,100 pg/ml, 78 ± 4%) secretion were significantly enhanced over vehicle-treated controls. Comparative evaluation of TNF responses in matched mono- or cocultures revealed that TNF markedly enhanced IL-6 secretion in cocultures over similar increases in TNF-stimulated ASM (4,000 ± 150 pg/ml) or NHBE (5,500 ± 20 pg/ml) cells. Interestingly, TNF-induced IP-10 levels in NHBE-ASM cocultures were lower compared with such responses in matched ASM (−1,600 ± 200 pg/ml) cultures. To demonstrate the specificity of coculture responses to TNF, fractalkine (CX3CL1) levels were measured in NHBE-ASM cocultures as well as in NHBE and ASM cultured alone. Fractalkine is a dual function chemokine serving as a cell adhesion molecule and a chemoattractant for monocytes and T cells in the airways. As shown in Fig. 3C, TNF-induced fractalkine secretion was unaffected by coculturing ASM and NHBE cells. These findings thus suggest a unique cytokine expression profile from cocultures of NHBE-ASM distinct from that observed in NHBE or ASM alone.

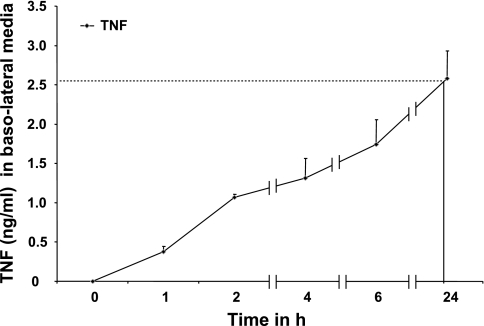

TNF-Induced Permeability in NHBE-ASM Cocultures

Given that TNF treatment in cocultures was performed at the apical surface of NHBE monolayers and given that cytokine secretions were assayed in basolateral fluids, we investigated whether leakage of TNF across the NHBE monolayer modulated ASM cytokine secretions. As demonstrated in Fig. 4, after addition of TNF (10 ng/ml), levels of TNF increased in the basolateral media at 1 h (0.48 ± 0.05 ng/ml). After 24 h of apical addition, 2.5 ± 0.5 ng/ml (25 ± 5% of initial addition) of TNF was detected in the basolateral media. It is noteworthy that, although 10 ng/ml TNF after 24 h enhanced IL-6 secretion in ASM monolayers alone, the effects were more profound (3,800 ± 0.05 pg/ml over ASM + TNF and 5,800 ± 0.05 pg/ml over NHBE + TNF) in NHBE-ASM cocultures where only 2.5 ng/ml TNF was detected by leakage. Although TNF induces leakage of apically administered cytokines to the ASM, the time course and levels of TNF delivered to the ASM cannot explain the IL-6 augmentation seen in the cocultures. These data suggest that the enhanced IL-6 secretion is likely due to autocrine and paracrine secretion of structural cell-derived mediators.

Fig. 4.

Time course of TNF permeability across NHBE monolayers at ALIs. TNF (10 ng/ml) was added at the apical surface of NHBE monolayers, and passage of TNF concentrations was determined in the basolateral media at various time points by ELISA. Data represent means ± SE from 3 separate experiments done in triplicate. Statistical evaluation was performed by ANOVA.

Ozone Enhances TNF-Induced IL-6 Secretion in NHBE-ASM Cocultures

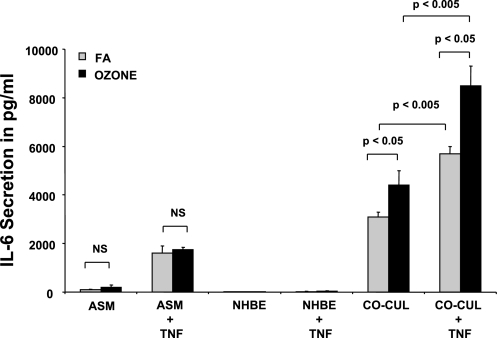

In our studies, ozone alone had little effect on IL-6 secretion in ASM or NHBE cultures. Whereas higher levels of IL-6 persisted in NHBE and ASM cocultures, ozone exposure augmented IL-6 basal secretion by 41 ± 3% (1,300 ± 400 pg/ml). To test the effects of ozone on cytokine-primed IL-6 secretion, ASM, NHBE, and NHBE-ASM cultures were pretreated with TNF or vehicle and subsequently treated with ozone for 6 h. As shown in Fig. 5, ozone exposure increased TNF-induced IL-6 levels by 50 ± 5% (2,800 ± 500 pg/ml) over cultures exposed to forced air (FA).

Fig. 5.

Ozone effects on IL-6 secretion in basal and TNF-stimulated NHBE-ASM cocultures and in NHBE and ASM cells cultured alone. ASM, NHBE, and NHBE-ASM cocultures were treated with TNF (10 ng/ml) or vehicle alone (gray bars) and post-exposed to ozone at 6 ppm (black bars) for 6 h. Cultures were reincubated for an additional 18 h in a 5% CO2-rich incubator and assayed for IL-6 secretion. Data represent means ± SE from 3 separate experiments done in triplicate. Statistical evaluation was performed by ANOVA. P > 0.05, significant difference. FA, forced air.

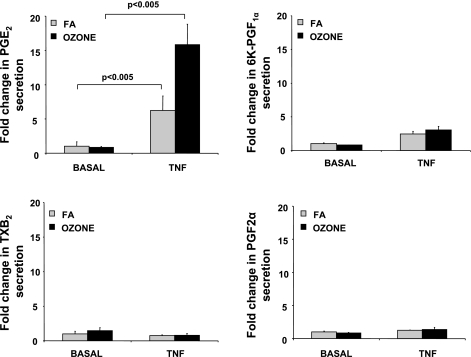

Ozone Markedly Increases PGE2 Levels in TNF-Treated NHBE-ASM Cocultures

Evidence suggests that ozone induces formation of COX metabolites in airways (27, 40). Perhaps because of interspecies differences in epithelial cell composition, analytical approaches, lipid membrane resident arachidonic acid (AA) stores, and COX-1/2 profiles, the effects of ozone in modulating prostanoid secretion remain contradictory (22, 60). We investigated the effects of ozone in modulating prostanoids in basal and TNF-treated cultures. These metabolites play a significant role in allergen-induced airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) and asthma (46). In our studies, constitutive levels of PGE2, PGF2α (1 ± 0.5 ng/ml), and TxB2 (0.02 ± 0.004 ng/ml) were detected in NHBE-ASM cocultures. As shown in Fig. 6, ozone exposure of cocultures showed no significant increases (P > 0.05) in 6-keto-PGF1α, PGF2α, or PGE2 levels in basolateral media, unlike IL-6 secretion shown previously. PGD2 remained undetectable in basal and stimulated conditions.

Fig. 6.

Ozone modulates PGE2 levels in basal and TNF-stimulated NHBE-ASM cultures. NHBE-ASM cultures treated with TNF (10 ng/ml) or vehicle alone were exposed to ozone (black bars) or FA (gray bars) for 6 h. Immediately after this period, basolateral media was assayed by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC/MS) methodology as described in methods. For each prostanoid, data are expressed as fold changes over ozone-unexposed cultures. Data represent means ± SE from 3 separate experiments done in triplicate. Statistical evaluation was performed by ANOVA. P > 0.05, significant difference. 6K-PGF1α, 6-keto-PGF1α; TxB2, thromboxane B2.

After TNF treatment, although PGE2 levels were markedly enhanced (6 ± 3-fold), a modest increase in 6-keto-PGF1α (2.4 ± 0.4-fold) was also observed over vehicle-treated controls. In TNF-treated cocultures, ozone exposure also increased PGE2 levels (8 ± 1.2-fold) over FA-exposed monolayers. PGD2 was again undetectable.

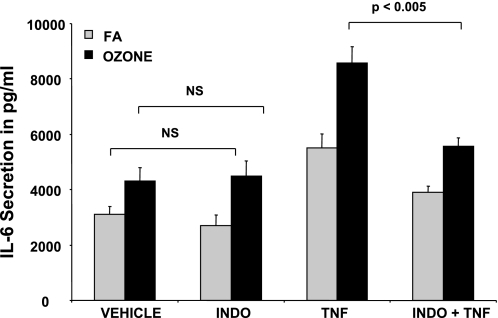

COX Inhibitors Modulate Ozone-Mediated IL-6 Secretion

Since ozone increased PGE2 levels in NHBE-ASM cultures, we postulated that COX inhibition would abrogate IL-6 secretion. In line with previous observations where ozone exposure did not enhance PGE2 in basal conditions, pretreatment with indomethacin elicited little change in constitutive IL-6 secretion (Fig. 7). In contrast, indomethacin completely inhibited ozone augmentation of TNF-mediated IL-6 secretion. These data suggest that ozone induces PGE2 levels that, in turn, augment IL-6 secretion in TNF-treated NHBE-ASM cultures.

Fig. 7.

Indomethacin (INDO) abrogates IL-6 secretion in ozone-exposed cocultures. NHBE-ASM cultures were pretreated with indomethacin (10 μM) or DMSO in the presence or absence of TNF (10 ng/ml) and postexposed to ozone (black bars) or ambient air (gray bars) for 6 h. IL-6 levels were measured by ELISA 18 h post-ozone exposure. Data represent means ± SE from 3 separate experiments performed in triplicate. Statistical evaluation was performed by ANOVA. P > 0.05, significant difference.

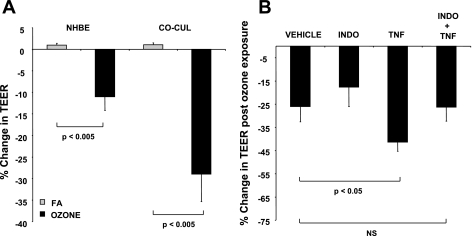

Indomethacin Partially Restores Ozone-Mediated Attenuation of TEER in NHBE-ASM Cultures

As shown in Fig. 8A, ozone exposure significantly decreased epithelial tight-junction integrity, as evidenced by TEER measurements in mono- (11 ± 3%) and cocultures (29 ± 6.2%). However, ozone-mediated epithelial TEER decreases were significantly greater in NHBE-ASM cocultures (18 ± 3%). Given these outcomes, we next studied the effects of ozone in NHBE tight-junction integrity in basal and TNF-treated NHBE-ASM cocultures. Ozone exposure further decreased NHBE tight-junction integrity induced by TNF in NHBE-ASM cocultures by 46 ± 3%. Ozone had little effect on PGE2 levels in basal cocultures, and preincubating monolayers with indomethacin also showed little effect in TEER (P = 0.14). In contrast, pretreatment with indomethacin at 10 μM for 2 h completely restored ozone-mediated TEER reduction in TNF-stimulated cocultures.

Fig. 8.

A: ozone diminishes TEER in NHBE mono- and NHBE-ASM cocultures. TEER values were determined in mono- or cocultures of NHBE cells after exposing them to ozone (0.6 ppm) or FA for 6 h. Data are represented as % changes in TEER. B: indomethacin prevents an ozone-induced decrease in TEER within NHBE monolayers. TEER values were estimated pre- and post-ozone exposure in NHBE-ASM cocultures that were treated with indomethacin (10 μM) or DMSO in the presence or absence of TNF (10 ng/ml). Data show % change in TEER from NHBE monolayers pre-and post-ozone exposure. All data are a summarization of 3 separate experiments performed in triplicate. Statistical evaluation was performed by ANOVA. P > 0.05, significant difference.

DISCUSSION

Since airway epithelial and ASM cells express immunomodulatory molecules and secrete proinflammatory mediators and given their spatial proximity in vivo, the interaction between these cells may play an important role in the pathogenesis of airway diseases (26). Both ASM and NHBE secrete a variety of mediators and cytokines such as IP-10, fractalkine, and IL-6 (8, 11, 28, 42); however, little is known about the cumulative effects of such mediators on airway function. Toward this end, using a coculture model comprising differentiated airway structural cells, we postulate that ozone increases PG levels, which, in turn, modulate NHBE and ASM function. Furthermore, since both NHBE and ASM express TNFR1 and TNFR2 receptors, and TNF promotes AHR after ozone exposure, we postulate that TNF modulates NHBE-ASM function in vitro. Indicative of cross talk among cell types, constitutive IL-6 and IP-10 were substantially altered in NHBE-ASM cocultures compared with that derived from monocultures of NHBE or ASM. Our studies complement those of others who report that higher levels of IP-10 were observed in cocultures of lung epithelial cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells over cultures of either cell type alone (59). TNF significantly enhanced IP-10 secretion in ASM cultures, whereas NHBE-ASM stimulation decreased IP-10 levels. A potential explanation may involve NHBE secretion of GM-CSF that decreased ASM-derived IP-10 secretion as reported by Finbloom et al. (21). Evidence in NHBE cells suggests that TNF stimulates early expression of a variety of mediators such as eotaxin, RANTES, and GM-CSF (43, 58). Such NHBE-derived mediators could synergize or antagonize the effects of TNF in modulating transcription of ASM-derived cytokines such as IL-6 and IP-10.

Ozone at concentrations of 0.1–0.6 ppm is an inhaled toxicant and has been studied as a modulator of airway function and injury (1, 54). As an oxidant, ozone interacts primarily with epithelium inducing transcription of antioxidant response element (ARE)-dependent antioxidant enzymes critical for cell survival (14). Activation of the ARE is dependent on the activation and nuclear translocation of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor (Nrf2) transcription factor. Disruption of Nrf2 signaling in airways can promote inflammation and apoptosis (52). In our coculture model, dose-response studies showed that ozone at doses of 0.6 ppm for 6 h induced optimal Nrf2 translocation with no effects on NHBE or ASM cell survival (data not shown). Previous studies have demonstrated that ozone induces epithelium-derived lipid ozonation products activating PLA2 or PLC and subsequent secretion of proinflammatory cytokines (33). Similarly, Kafoury et al. (33) demonstrated that ozone induces IL-8 secretion by activating transcription factor IL-6 (NF-IL-6) and NF-κB. Although such studies explored ozone effects in inducing cytokines in singular cultures of epithelial cells, a comprehensive examination of NHBE-derived mediators on other airway resident cell types remains unknown. Using an NHBE-ASM coculture model, we investigated whether ozone modulated the secretion of IL-6 from airway structural cells. To our knowledge, this is the first report that defines the bidirectional effects of ozone on human NHBE and ASM cell function. Ozone exposure enhanced IL-6 secretion in cocultures. Besides the direct effect of ozone on epithelium, structural cell responses are also modulated by immune cell-derived mediators. In clinical studies, enhanced alveolar macrophage recruitment occurs after ozone exposure (6). Similarly, ozone exposure augmented TNF secretion from macrophages both in vitro and ex vivo (7, 51). In an effort to test the effects of ozone on structural cell interactions in the presence of immune cell-derived cytokines, we stimulated NHBE-ASM cocultures with TNF in the presence and absence of ozone. Whereas ozone had little effect on IL-6 secretion in TNF-stimulated monocultures, a substantial augmentation in cocultures was noted. In animal models of oxidative injury, a critical role of TNF has been advocated (17, 39). In rodent lungs, the lack of TNF responses provided significant protection from ozone-induced inflammation and airway hyperreactivity; TNFR (−/−) mice have significantly less ozone-mediated inflammation and epithelial damage (15, 56, 64). Others have demonstrated that intraperitoneal administration of neutralizing antibodies against TNF substantially curtails ozone-induced IL-6 levels (10). Together, our conclusions that TNF substantially enhances ozone-mediated increases in cytokine levels in NHBE-ASM cocultures are consistent with the critical role of TNF in inducing ozone-mediated inflammation and injury.

In ASM cells, TNF alone has little effect on contractile responses; however, TNF-primed ASM is more responsive to contractile agonists (2). The mechanism by which this occurs is due, in part, to increased expression of CD38 that generates cADPR, a reputed ligand for the ryanodine receptor (3). TNF also enhances cytoplasmic calcium stores and calcium sensitization pathways in ASM. These changes could, in turn, augment ozone-induced airway responsiveness. Although both mechanisms modulate contractile responses in TNF-primed ASM cells, whether such mechanisms alter gene regulation and cytokine secretion is unknown. Alternatively, TNF could augment ozone-induced eicosanoid levels. TNF binding to distinct receptors (TNFR1p55 and TNFR2p75) induces sequential membrane recruitment of intracellular adaptor proteins TNFR1-associated death domain protein (TRADD) and TNFR-associated factor 2 (TRAF2). Mutual interactions among these proteins induce downstream activation of NF-κB and activator protein (AP)-1, enhancing secretion of cytokines and/or metabolites dependent on COX-1/2 activation (13).

Inducible COX-1 and COX-2 could increases PGE2 during inflammatory responses. Unlike other cell types, TNF alone has little effect on COX-2 activation in ASM or NHBE cells (9, 45). However, in the presence of other cytokines, COX-2 expression is markedly induced (9). Evidence suggests that the COX-2 promoter has two putative NF-κB elements, and COX-2 activation is partially dependent on transcriptional regulation of these sites (5, 30). Although it is unlikely that TNF alone stimulated PGE2 secretion in cocultures, TNF may, in combination with other cytokines, enhance COX-2 activation (49). Post-ozone exposure, LC/MS analysis revealed no changes in most prostanoids, yet IL-6 secretion increased as did PGE2 levels in basal and in TNF-primed cultures. Our data are consistent with studies where ozone was shown to increase PGE2 levels in human epithelial A549 and BEAS-2B cell lines (29, 44). In vivo studies revealed elevated levels of PGE2, PGF2α, TxB2, and neutrophil numbers in human BAL fluid post-ozone exposure (54). Others reported on the association of increased BAL neutrophil numbers with increases in PGE2 and PGF2α (63). Neutrophils are an important source of a wide variety of prostanoids, thromboxanes, leukotrienes, and platelet-activating factor (PAF) in the airways (34). It is important to note that our demonstrations of ozone-mediated effects are confined to early synthetic outcomes in airway structural cells and hence do not account for similar secretions by neutrophils or distal airway structural cells as demonstrated in BAL fluids.

PGE2 levels modulate a variety of airway functions. In epithelial cells, PGE2 enhances ciliary beat frequency and electrolyte transport (1). In ASM cells, PGE2 stimulates bronchoconstriction in some species, whereas in human ASM, PGE2 promotes bronchodilation. Other COX metabolites such as PGF2α, TxA2, and PGD2 are contractile agonists in some but not all species (37). Despite species variations, in some human-derived cell systems, PGE2 acts as an anti-inflammatory molecule and may promote or restrain inflammation via interactions among E1 prostanoid (EP1), EP2, EP3, and EP4 receptor subtypes (50). Enhanced PGE2 levels post-ozone exposure may, in part, serve as a negative feedback mechanism that decreases proinflammatory cytokine secretion. Although controversial, COX-dependent PGE2 secretion could also potentially shunt the released AA from the generation of potent bronchoconstrictors of the lipoxygenase (LO) pathway such as n-HETEs and n-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acids (n-HODEs).

The relevance of COX-2 in mediating airway PGE2 secretion is unclear. As previously reported, ibuprofen decreases exhaled PGE2 concentrations in patients with COPD, whereas rofecoxib (a selective COX-2 inhibitor) had little effect, indicating a potential role for COX-1 activation in COPD (48). In a murine model of allergen-induced lung inflammation, comparable levels of PGE2 in BAL fluid were reported in wild-type and COX-2-deficient mice (24). Given the implications that PGs regulate cytokines in airway diseases, we addressed whether COX inhibition suppresses PGE2 generation and IL-6 secretion. Consistent with ozone effects in modulating PGE2 generation, pretreatment with indomethacin inhibited TNF-induced IL-6 secretion and showed little effect on constitutive IL-6 levels. Thus ozone may mediate TNF-induced IL-6 secretion in both a PGE2-dependent and -independent manner (in the absence of a cytokine stimulus). Whereas our study examined the expression of COX-2-mediated AA metabolites, the role of 15-LO-mediated metabolites remains unknown. Studies have reported that ozone enhances 15-HETE in tracheal epithelial cells (1). Since multiple enzymes such as cytochrome P-450 and 15-LO enzymes metabolize AA to 15-HETE, indomethacin may have little effect in abrogating the synthesis of 15-HETE (23, 65). Plausibly, ozone-mediated augmentation of IL-6 secretion in the absence of PGE2 is, in part, due to LO metabolites.

Based on the reports demonstrating an important role of airway epithelium in mediating ozone-induced AHR and barrier function, we studied the effects of ozone in modulating TEER. In human subjects, ozone exposure enhanced epithelial cell permeability; our studies using TEER measurements revealed a similar effect after ozone exposure (35). Possibly, an ozone-mediated reduction in epithelial tight-junction integrity may augment the permeability of apically added TNF to the basolateral surface. As demonstrated in Fig. 5, however, addition of TNF (10 ng/ml) directly to NHBE or ASM cultures alone did not significantly enhance IL-6 or PGE2 secretion after ozone exposure. Evidence suggests that ozone-mediated BAL fluid protein increases were not significantly different in IL-6+/+ and IL-6−/− mice, implying that a mechanism modulating ozone-mediated airway injury may occur in an IL-6-independent manner (31). Others have shown that ozone-induced AHR and epithelial cell injury in BAL fluid were substantially abrogated by pretreatment with COX inhibitors (20). In a concentration-dependent manner, indomethacin inhibited ozone-induced increases in PGE2 levels and improved epithelial cell integrity as measured by TEER. In the absence of cytokine stimulus, ozone had little effect on PGE2 levels; accordingly, indomethacin also had little effect on TEER. In the presence of TNF, ozone substantially enhanced PGE2 levels. Predictably, indomethacin pretreatment partially restored an ozone-mediated reduction in TEER in TNF-stimulated cocultures.

In summary, using a human NHBE/ASM coculture model, we demonstrated that ozone modulates PGE2 and IL-6 secretion. Although airway structural cells produce a variety of prostanoids, our study is the first to identify the ability of ozone in differentially mediating structural cell-derived prostanoid levels. Although ozone enhanced PGE2 levels and IL-6 secretion in cocultures, such enhancement was further increased with TNF treatment. Ozone-mediated PGE2 appears to play an important role in modulating ozone-induced IL-6 secretion in airway structural cells, and inhibition of COX significantly restores epithelial cell tight-junction integrity while decreasing IL-6 levels. Our study thus identifies human structural cell interactions in modulating ozone-induced PG synthesis that may promote and increase IL-6 secretion in the airways.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant R01-HL-080676, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Grant ES-013508, and National Institute of Allergy, Immunology, and Infectious Diseases Grant R01-AI-055593.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge Mary McNichol for expert assistance in preparation of this manuscript.

The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. The article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alpert SE, Walenga RW. Ozone exposure of human tracheal epithelial cells inactivates cyclooxygenase and increases 15-HETE production. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 269: L734–L743, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amrani Y, Krymskaya V, Maki C, Panettieri RA Jr. Mechanisms underlying TNFα effects on agonist-mediated calcium homeostasis in human airway smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 273: L1020–L1028, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Amrani Y, Tliba O, Deshpande DA, Walseth TF, Kannan MS, Panettieri RA Jr. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness: insights into new signaling molecules. Curr Opin Pharmacol 4: 230–234, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson JM, Van Itallie CM. Tight junctions and the molecular basis for regulation of paracellular permeability. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 269: G467–G475, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Appleby SB, Ristimaki A, Neilson K, Narko K, Hla T. Structure of the human cyclo-oxygenase-2 gene. Biochem J 302: 723–727, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arjomandi M, Witten A, Abbritti E, Reintjes K, Schmidlin I, Zhai W, Solomon C, Balmes J. Repeated exposure to ozone increases alveolar macrophage recruitment into asthmatic airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 172: 427–432, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arsalane K, Gosset P, Vanhee D, Voisin C, Hamid Q, Tonnel AB, Wallaert B. Ozone stimulates synthesis of inflammatory cytokines by alveolar macrophages in vitro. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 13: 60–68, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Banerjee A, Damera G, Bhandare R, Gu S, Lopez-Boado YS, Panettieri RA Jr, Tliba O. Vitamin D and glucocorticoids differentially modulate chemokine expression in human airway smooth muscle cells. Br J Pharmacol 155: 84–92, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belvisi MG, Saunders MA, Haddad el B, Hirst SJ, Yacoub MH, Barnes PJ, Mitchell JA. Induction of cyclo-oxygenase-2 by cytokines in human cultured airway smooth muscle cells: novel inflammatory role of this cell type. Br J Pharmacol 120: 910–916, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhalla DK, Reinhart PG, Bai C, Gupta SK. Amelioration of ozone-induced lung injury by anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha. Toxicol Sci 69: 400–408, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan MC, Cheung CY, Chui WH, Tsao SW, Nicholls JM, Chan YO, Chan RW, Long HT, Poon LL, Guan Y, Peiris JS. Proinflammatory cytokine responses induced by influenza A (H5N1) viruses in primary human alveolar and bronchial epithelial cells. Respir Res 6: 135, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chiba T, Kanda A, Ueki S, Ito W, Kamada Y, Oyamada H, Saito N, Kayaba H, Chihara J. Prostaglandin D2 induces IL-8 and GM-CSF by bronchial epithelial cells in a CRTH2-independent pathway. Int Arch Allergy Immunol 141: 300–307, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho HY, Morgan DL, Bauer AK, Kleeberger SR. Signal transduction pathways of tumor necrosis factor-mediated lung injury induced by ozone in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175: 829–839, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cho HY, Reddy SP, Kleeberger SR. Nrf2 defends the lung from oxidative stress. Antioxid Redox Signal 8: 76–87, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cho HY, Zhang LY, Kleeberger SR. Ozone-induced lung inflammation and hyperreactivity are mediated via tumor necrosis factor-α receptors. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 280: L537–L546, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chung KF Inflammatory mediators in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy 4: 619–625, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Churg A, Dai J, Tai H, Xie C, Wright JL. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha is central to acute cigarette smoke-induced inflammation and connective tissue breakdown. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 166: 849–854, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Devlin RB, McKinnon KP, Noah T, Becker S, Koren HS. Ozone-induced release of cytokines and fibronectin by alveolar macrophages and airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 266: L612–L619, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Doganci A, Sauer K, Karwot R, Finotto S. Pathological role of IL-6 in the experimental allergic bronchial asthma in mice. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol 28: 257–270, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fabbri LM, Aizawa H, O'Byrne PM, Bethel RA, Walters EH, Holtzman MJ, Nadel JA. An anti-inflammatory drug (BW755C) inhibits airway hyperresponsiveness induced by ozone in dogs. J Allergy Clin Immunol 76: 162–166, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Finbloom DS, Larner AC, Nakagawa Y, Hoover DL. Culture of human monocytes with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor results in enhancement of IFN-gamma receptors but suppression of IFN-gamma-induced expression of the gene IP-10. J Immunol 150: 2383–2390, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fouke JM, DeLemos RA, Dunn MJ, McFadden ER Jr. Effects of ozone on cyclooxygenase metabolites in the baboon tracheobronchial tree. J Appl Physiol 69: 245–250, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frohberg P, Drutkowski G, Wobst I. Monitoring eicosanoid biosynthesis via lipoxygenase and cyclooxygenase pathways in human whole blood by single HPLC run. J Pharm Biomed Anal 41: 1317–1324, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gavett SH, Madison SL, Chulada PC, Scarborough PE, Qu W, Boyle JE, Tiano HF, Lee CA, Langenbach R, Roggli VL, Zeldin DC. Allergic lung responses are increased in prostaglandin H synthase-deficient mice. J Clin Invest 104: 721–732, 1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gray TE, Guzman K, Davis CW, Abdullah LH, Nettesheim P. Mucociliary differentiation of serially passaged normal human tracheobronchial epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 14: 104–112, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holgate ST, Davies DE, Lackie PM, Wilson SJ, Puddicombe SM, Lordan JL. Epithelial-mesenchymal interactions in the pathogenesis of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 105: 193–204, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holtzman MJ Arachidonic acid metabolism in airway epithelial cells. Annu Rev Physiol 54: 303–329, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Howarth PH, Knox AJ, Amrani Y, Tliba O, Panettieri RA Jr, Johnson M. Synthetic responses in airway smooth muscle. J Allergy Clin Immunol 114: S32–S50, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jaspers I, Flescher E, Chen LC. Ozone-induced IL-8 expression and transcription factor binding in respiratory epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 272: L504–L511, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jobin C, Morteau O, Han DS, Balfour Sartor R. Specific NF-kappaB blockade selectively inhibits tumour necrosis factor-alpha-induced COX-2 but not constitutive COX-1 gene expression in HT-29 cells. Immunology 95: 537–543, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnston RA, Schwartzman IN, Flynt L, Shore SA. Role of interleukin-6 in murine airway responses to ozone. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 288: L390–L397, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kadowitz PJ, Spannhake EW, Hyman AL. Prostaglandins evoke a whole variety of responses in the lung. Environ Health Perspect 35: 181–190, 1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kafoury RM, Pryor WA, Squadrito GL, Salgo MG, Zou X, Friedman M. Induction of inflammatory mediators in human airway epithelial cells by lipid ozonation products. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 160: 1934–1942, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kay AB, Corrigan CJ. Asthma. Eosinophils and neutrophils. Br Med Bull 48: 51–64, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kehrl HR, Vincent LM, Kowalsky RJ, Horstman DH, O'Neil JJ, McCartney WH, Bromberg PA. Ozone exposure increases respiratory epithelial permeability in humans. Am Rev Respir Dis 135: 1124–1128, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kikuchi T, Shively JD, Foley JS, Drazen JM, Tschumperlin DJ. Differentiation-dependent responsiveness of bronchial epithelial cells to IL-4/13 stimulation. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 287: L119–L126, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Knox AJ, Tattersfield AE. Airway smooth muscle relaxation. Thorax 50: 894–901, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kopf M, Baumann H, Freer G, Freudenberg M, Lamers M, Kishimoto T, Zinkernagel R, Bluethmann H, Kohler G. Impaired immune and acute-phase responses in interleukin-6-deficient mice. Nature 368: 339–342, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kuroki M, Noguchi Y, Shimono M, Tomono K, Tashiro T, Obata Y, Nakayama E, Kohno S. Repression of bleomycin-induced pneumopathy by TNF. J Immunol 170: 567–574, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leikauf GD, Driscoll KE, Wey HE. Ozone-induced augmentation of eicosanoid metabolism in epithelial cells from bovine trachea. Am Rev Respir Dis 137: 435–442, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Leikauf GD, Simpson LG, Santrock J, Zhao Q, Abbinante-Nissen J, Zhou S, Driscoll KE. Airway epithelial cell responses to ozone injury. Environ Health Perspect 103, Suppl 2: 91–95, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matsukura S, Kokubu F, Kurokawa M, Kawaguchi M, Ieki K, Kuga H, Odaka M, Suzuki S, Watanabe S, Takeuchi H, Kasama T, Adachi M. Synthetic double-stranded RNA induces multiple genes related to inflammation through Toll-like receptor 3 depending on NF-kappaB and/or IRF-3 in airway epithelial cells. Clin Exp Allergy 36: 1049–1062, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Matsukura S, Stellato C, Plitt JR, Bickel C, Miura K, Georas SN, Casolaro V, Schleimer RP. Activation of eotaxin gene transcription by NF-kappa B and STAT6 in human airway epithelial cells. J Immunol 163: 6876–6883, 1999. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McKinnon KP, Madden MC, Noah TL, Devlin RB. In vitro ozone exposure increases release of arachidonic acid products from a human bronchial epithelial cell line. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 118: 215–223, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mitchell JA, Belvisi MG, Akarasereenont P, Robbins RA, Kwon OJ, Croxtall J, Barnes PJ, Vane JR. Induction of cyclo-oxygenase-2 by cytokines in human pulmonary epithelial cells: regulation by dexamethasone. Br J Pharmacol 113: 1008–1014, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Montuschi P, Barnes PJ. Exhaled leukotrienes and prostaglandins in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol 109: 615–620, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Montuschi P, Kharitonov SA, Ciabattoni G, Barnes PJ. Exhaled leukotrienes and prostaglandins in COPD. Thorax 58: 585–588, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Montuschi P, Macagno F, Parente P, Valente S, Lauriola L, Ciappi G, Kharitonov SA, Barnes PJ, Ciabattoni G. Effects of cyclo-oxygenase inhibition on exhaled eicosanoids in patients with COPD. Thorax 60: 827–833, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moore PE, Lahiri T, Laporte JD, Church T, Panettieri RA Jr, Shore SA. Selected contribution: synergism between TNF-α and IL-1β in airway smooth muscle cells: implications for β-adrenergic responsiveness. J Appl Physiol 91: 1467–1474, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pavord ID, Tattersfield AE. Bronchoprotective role for endogenous prostaglandin E2. Lancet 345: 436–438, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pendino KJ, Shuler RL, Laskin JD, Laskin DL. Enhanced production of interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and fibronectin by rat lung phagocytes following inhalation of a pulmonary irritant. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 11: 279–286, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rangasamy T, Guo J, Mitzner WA, Roman J, Singh A, Fryer AD, Yamamoto M, Kensler TW, Tuder RM, Georas SN, Biswal S. Disruption of Nrf2 enhances susceptibility to severe airway inflammation and asthma in mice. J Exp Med 202: 47–59, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schelegle ES, Siefkin AD, McDonald RJ. Time course of ozone-induced neutrophilia in normal humans. Am Rev Respir Dis 143: 1353–1358, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Seltzer J, Bigby BG, Stulbarg M, Holtzman MJ, Nadel JA, Ueki IF, Leikauf GD, Goetzl EJ, Boushey HA. O3-induced change in bronchial reactivity to methacholine and airway inflammation in humans. J Appl Physiol 60: 1321–1326, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shore SA, Johnston RA, Schwartzman IN, Chism D, Krishna Murthy GG. Ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness is reduced in immature mice. J Appl Physiol 92: 1019–1028, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shore SA, Schwartzman IN, Le Blanc B, Murthy GG, Doerschuk CM. Tumor necrosis factor receptor 2 contributes to ozone-induced airway hyperresponsiveness in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164: 602–607, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Song WL, Lawson JA, Wang M, Zou H, FitzGerald GA. Noninvasive assessment of the role of cyclooxygenases in cardiovascular health: a detailed HPLC/MS/MS method. Methods Enzymol 433: 51–72, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Stellato C, Beck LA, Gorgone GA, Proud D, Schall TJ, Ono SJ, Lichtenstein LM, Schleimer RP. Expression of the chemokine RANTES by a human bronchial epithelial cell line. Modulation by cytokines and glucocorticoids. J Immunol 155: 410–418, 1995. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Torvinen M, Campwala H, Kilty I. The role of IFN-gamma in regulation of IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10 (IP-10) expression in lung epithelial cell and peripheral blood mononuclear cell co-cultures. Respir Res 8: 80, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Van Hoof HJ, Zijlstra FJ, Voss HP, Garrelds IM, Dormans JA, Van Bree L, Bast A. The effect of ozone exposure on the release of eicosanoids in guinea-pig BAL fluid in relation to cellular damage and inflammation. Mediators Inflamm 6: 355–361, 1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Vincent R, Vu D, Hatch G, Poon R, Dreher K, Guenette J, Bjarnason S, Potvin M, Norwood J, McMullen E. Sensitivity of lungs of aging Fischer 344 rats to ozone: assessment by bronchoalveolar lavage. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 271: L555–L565, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ward NS, Waxman AB, Homer RJ, Mantell LL, Einarsson O, Du Y, Elias JA. Interleukin-6-induced protection in hyperoxic acute lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 22: 535–542, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weinmann GG, Liu MC, Proud D, Weidenbach-Gerbase M, Hubbard W, Frank R. Ozone exposure in humans: inflammatory, small and peripheral airway responses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 152: 1175–1182, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Young C, Bhalla DK. Effects of ozone on the epithelial and inflammatory responses in the airways: role of tumor necrosis factor. J Toxicol Environ Health 46: 329–342, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhu D, Medhora M, Campbell WB, Spitzbarth N, Baker JE, Jacobs ER. Chronic hypoxia activates lung 15-lipoxygenase, which catalyzes production of 15-HETE and enhances constriction in neonatal rabbit pulmonary arteries. Circ Res 92: 992–1000, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]