Abstract

Background and Aims

The potential for gene exchange between species with different ploidy levels has long been recognized, but only a few studies have tested this hypothesis in situ and most of them focused on not more than two co-occurring species. In this study, we examined hybridization patterns in two sites containing three species of the genus Dactylorhiza (diploid D. incarnata and D. fuchsii and their allotetraploid derivative D. praetermissa).

Methods

To compare the strength of reproductive barriers between diploid species, and between diploid and tetraploid species, crossing experiments were combined with morphometric and molecular analyses using amplified fragment length polymorphism markers, whereas flow cytometric analyses were used to verify the hybrid origin of putative hybrids.

Key Results

In both sites, extensive hybridization was observed, indicating that gene flow between species is possible within the investigated populations. Bayesian assignment analyses indicated that the majority of hybrids were F1 hybrids, but in some cases triple hybrids (hybrids with three species as parents) were observed, suggesting secondary gene flow. Crossing experiments showed that only crosses between pure species yielded a high percentage of viable seeds. When hybrids were involved as either pollen-receptor or pollen-donor, almost no viable seeds were formed, indicating strong post-zygotic reproductive isolation and high sterility.

Conclusions

Strong post-mating reproductive barriers prevent local breakdown of species boundaries in Dactylorhiza despite frequent hybridization between parental species. However, the presence of triple hybrids indicates that in some cases hybridization may extend the F1 generation.

Keywords: AFLP, Dactylorhiza incarnata, Dactylorhiza praetermissa, genetic analysis, hybridization, morphology, polyploidy, reproductive isolation, triple hybrid

INTRODUCTION

Hybridization and introgression may increase genetic diversity within species, transfer genetic adaptations between species, break down or reinforce reproductive barriers between closely related groups, and lead to the emergence of new ecotypes or species (Barton and Hewitt, 1989; Abbott, 1992; Rieseberg, 1997). Hybridization occurs either with or without genome doubling. Hybridization with genome doubling (i.e. allopolyploidization) is one of the most common mechanisms of sympatric speciation (Arnold, 1997; Otto and Whitton, 2000; Coyne and Orr, 2004; Rieseberg and Willis, 2007). There is also strong empirical evidence that hybridization can give rise to new species without a change in ploidy level (‘homoploid hybrid speciation’) (Arnold, 1997; Rieseberg, 1997; Rieseberg and Willis, 2007).

Hybrid zones between cytotypes with different ploidy levels are particularly interesting, as they allow us to study the mechanisms involved in the early stages of polyploid speciation and how reproductive isolation mechanisms may affect the establishment of polyploids in diploid populations (Thompson and Lumaret, 1992; Petit et al., 1999; Coyne and Orr, 2004). Although the potential for gene exchange between taxa with different ploidy levels has long been recognized (Stebbins, 1971), relatively few studies have tested its frequency in the wild (Petit et al., 1999; Chapman and Abbott, 2010; De hert et al., 2011). The reason for this is that gene flow between species with different ploidy levels is thought to be unlikely, as such species are assumed to be reproductively isolated from each other due to strong post-zygotic barriers (Coyne and Orr, 2004). However, recent studies have suggested the evolution of reproductive barriers in contact zones of diploid–polyploid species, including the possibility of introgression across species boundaries (Aagaard et al., 2005; Shipunov et al., 2005; Pillon et al., 2007; Ståhlberg and Hedrén, 2009; Pinheiro et al., 2010).

The food-deceptive orchid genus Dactylorhiza is an excellent study group to test the extent of gene flow between species of different ploidy levels. Polyploidization within Dactylorhiza has been relatively well documented (Hedrén, 1996a; Hedrén et al., 2001; Devos et al., 2006; Pillon et al., 2007) and allotetraploids have evolved on several occasions due to repeated hybridization (Hedrén, 1996a, 2003) between two main groups of parental taxa. These parental lineages include the diploid marsh orchids, D. incarnata sensu lato, and the spotted orchids, the diploid D. fuchsii and more rarely also the autotetraploid D. maculata (Heslop-Harrison, 1953, 1956; Hedrén, 1996a; Hedrén et al., 2001; Devos et al., 2006; Pillon et al., 2007). Hedrén et al. (2001) suggested that allotetraploidization dominates over introgression as speciation mechanism in this genus. Hybridization between species with different ploidy levels has been frequently reported in the genus Dactylorhiza (Heslop-Harrison, 1953, 1957; Lord and Richards, 1977; Aagaard et al., 2005; Shipunov et al., 2005; Pillon et al., 2007; Ståhlberg and Hedrén, 2009). Hybridization and introgression between diploids and allotetraploids, and between different independently derived allotetraploids may further have contributed to genetic diversity at the tetraploid level (Hedrén, 2003). It is even possible that some allotetraploid species have multiple origins (Hedrén, 1996a).

Greater insight into the different pathways of the speciation processes in Dactylorhiza requires studying in situ hybridization in natural hybrid zones and assessing the strength of reproductive barriers. Pre-mating barriers are generally very weak in the genus (Aagaard et al., 2005; Ståhlberg and Hedrén, 2009), as Dactylorhiza species are food-deceptive and depend on naïve pollinators (Mattila and Kuitunen, 2000; Ferdy et al., 2001; Lammi et al., 2003; Vallius et al., 2004, 2007). Post-zygotic barriers, on the other hand, are expected to be more important (Scopece et al., 2007, 2008), particularly in species with differing ploidy levels. In this case, hybrid inviability and sterility are not uncommon and may result from chromosomal rearrangements and/or genic incompatibilities (Rieseberg and Carney, 1998). However, relatively few studies have examined in situ hybridization in Dactylorhiza and all of them focused on not more than two co-occurring species. Some studies found indications of backcrossing (Aagaard et al., 2005), whereas others found evidence for introgressive gene flow between ploidy levels (Nordström and Hedrén, 2008; Ståhlberg and Hedrén, 2009), suggesting the occurrence of introgression, and hence of some hybrid fertility. In hybrid zones containing more than two species, patterns of hybridization may become more complex.

In this study, we examined hybridization patterns at two different sites containing two diploid species (D. incarnata and D. fuchsii) and one allotetraploid species (D. praetermissa). To assess the strength of reproductive barriers acting between the investigated species, molecular markers, flow cytometry and morphological analyses were used. In addition, the genome compatibility of parental species and the fertility of putative hybrids were assessed by manual crossing experiments. More specifically, we addressed the following questions. (1) Do D. incarnata, D. fuchsii and D. praetermissa hybridize with each other in natural sympatric populations? (2) If hybridization occurs, is there a difference in frequency of hybridization between different parental species? (3) How strong are post-mating barriers between these taxa?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study species

Dactylorhiza incarnata (L.) Soó, D. fuchsii (Druce) Soó and D. praetermissa (Druce) Soó are herbaceous, perennial, food-deceptive orchid species. D. praetermissa is an allotetraploid (2n = 4x = 80), whereas D. incarnata and D. fuchsii are diploids (2n = 2x = 40) and are probably the present-day representatives of the progenitor lineages of D. praetermissa (Hedrén, 1996a, b). However, some authors (Devos et al., 2006; Pillon et al. 2007) have suggested that the maternal parent of D. praetermissa may have been related to the southern D. saccifera rather than D. fuchsii (or at least partly), as it contains some internal transcribed spacer variants typical of D. saccifera. The descriptions of morphology and ecology of our study species are based on their occurrence in Belgium. D. incarnata is predominantly found in wet meadows, dune slacks, fens and marshes, where it often occurs in somewhat calcareous, nutrient-poor, humid soils. D. praetermissa prefers calcareous soils, and sites with some disturbance. It occurs in periodically flooded dune slacks, roadsides, canal verges, raised terrains, and grazed or mown fens. D. fuchsii occurs in humid forests, mesophilic grasslands and wet meadows, on nutrient-rich, mostly neutral or alkaline substrate.

All three species are mainly pollinated by bumble-bees [occasionally also by other relatively large insects (Hymenoptera, Coleoptera)] (Lammi and Kuitunen, 1995; Ferdy et al., 2001; Lammi et al., 2003; Vallius et al., 2004). D. incarnata has a dense inflorescence with pink-purplish, purplish or occasionally almost white flowers. The flowers are relatively small and the labellum has reflexed lateral lobes. The labellum markings consist of loops which are somewhat lung-shaped. Leaves of D. incarnata are lanceolate, and usually have a hooded leaf tip. Some subspecies of D. incarnata can have yellow flowers (ssp. ochroleuca) or spots on both sides of the leaves (ssp. cruenta) (Bateman and Denholm, 1985), but these subspecies – some authors (e.g. Bournérias and Prat, 2005) treat them as distinct species – do not occur in Belgium. Inflorescences of D. praetermissa are dense and comprise bright pink to purplish flowers (Lambinon et al., 1998; Bournérias and Prat, 2005). The labellum is often rather flat and bears many small spots, which may be accompanied by short lines or even loops. The lanceolate leaves of D. praetermissa can be spotted, but if so only on the upper surface. Both D. incarnata and D. praetermissa have a hollow stem, in contrast to D. fuchsii which has a solid stem. Inflorescences of D. fuchsii are dense and comprise small flowers which are white or pink to pale purplish. The labellum of the flowers is very clearly trilobed; the middle lobe is nearly as long as the lateral lobes. The labellum markings consist mainly of loops which are somewhat ‘w’-shaped. The lanceolate leaves of D. fuchsii are nearly always spotted on the upper surface of the leaf.

Study sites and data collection

The study was conducted in two dune slacks, one at a site named Ter Yde (Oostduinkerke, Belgium, 51°08′03″N, 2°41′16″E) and one at a site named Paelsteenpanne (Bredene, Belgium, 51°15′31″N, 2°59′04″E). The climate at both sites is maritime temperate. Typical co-occurring species were Salix repens, Centaurium littorale, Carex trinervis and Epipactis palustris. Management of both areas consists of mowing after the growing season. Both sites previously contained all three species and putative hybrids, but at Ter Yde pure D. praetermissa individuals are no longer present (W. Van den Bussche, National Botanic Garden of Belgium, pers. comm.). Within each site, we first selected at random a set of apparently pure individuals, i.e. individuals that clearly belonged to one of the three species based on the morphological characteristics described above. Next, we selected a large set of putative hybrids throughout the site. Putative hybrid individuals were selected to represent all morphological variation present. At the same time, leaf samples were collected for DNA analysis. Leaf material was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80 °C before freeze drying for 48 h. The dried material was vacuum packed and stored at room temperature until DNA extraction. A total of 295 (91 D. incarnata, 46 D. fuchsii and 158 putative hybrids) and 163 (44 D. incarnata, 13 D. fuchsii, 52 D. praetermissa and 54 putative hybrids) flowering individuals were mapped and sampled in Ter Yde (June 2008) and in Paelsteenpanne (June 2009), respectively. The estimated number of flowering individuals was 9000 in Ter Yde (4000 D. incarnata, 1300 D. fuchsii and 3700 putative hybrids) and 2470 in Paelsteenpanne (1500 D. incarnata, 20 D. fuchsii, 400 D. praetermissa and 550 putative hybrids).

After fruit maturation, fruiting success was determined for each sampled plant as the ratio of the number of fruits to the number of flowers. Fruits were harvested and brought to the laboratory for further inspection. The proportion of viable seeds was determined for five plants from each category (five fruits per plant) using the tetrazolium method, according to the protocol of Van Waes and Debergh (1986); only viable embryos are stained red after the treatment. Because the tetrazolium method can overestimate the real germination rate, the seed viability percentages should be treated with caution. However, for comparative purposes this method is sufficient to investigate differences among pure species and hybrids and among pollination treatments. We counted a subsample of 200–300 seeds from each capsule. We calculated the percentage of viable seeds as the ratio of the number of coloured seeds to the total number of seeds.

DNA extraction and AFLP analysis

Forty milligrams of the dried material was ground using a Retsch mill and DNA isolation was carried out according to the CTAB-extraction procedure of Lefort and Douglas (1999). DNA concentrations were estimated using a NanoDrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA). Amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers (Vos et al., 1995) were used to screen the genetic diversity of our samples. AFLP analysis was carried out according to the protocol described in Vandepitte et al. (2009). Four primer combinations were used: EcoRI-AGG/MseI-CTAG, EcoRI-AGG/MseI-CTGG, EcoRI-ACAG/MseI-CTA and EcoRI-ACAG/MseI-GGT (MWG biotech, Ebersberg, Germany). AFLP fragments were separated on an ABI3130xl sequencer on 50-cm capillaries using the polymer Pop7 (Applied Biosystems). A GeneScan 500 Rox-labelled size standard (Applied Biosystems) was injected with each AFLP sample to allow sizing of the DNA fragments. The fluorescent AFLP patterns were scored using GeneMapper 3·7 (Applied Biosystems). Each marker was coded as 1 or 0 for presence or absence in an individual, forming a binary data matrix. Each sample was thus represented by a vector of ones and zeros. To assess the reproducibility of the protocol, two independent DNA extractions were carried out for nine samples. The overall error rate, i.e. the percentage of differently scored loci between repeated samples, was low (3·4 %).

AFLP data were subjected to Bayesian analyses using methods implemented in the program Structure version 2·2 (Pritchard et al., 2000). Structure uses a model-based clustering method to assign individuals to groups in which deviations from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium and linkage equilibrium are minimized. Individuals assigned to two sources with non-trivial probabilities are potential hybrids. In the Structure model, the posterior probability (q) describes the proportion of an individual genotype originating from each of K categories. In the present case, setting K = 3 corresponds to the assumption of three species contributing to the gene pool of the sample. Preliminary assignment analysis based on the criteria of Evanno et al. (2005) confirmed this assumption. When we ran Structure on a dataset of only pure individuals, the lnP(D) values increased until K = 3 and then evened out. For K = 3 all pure individuals were unambiguously assigned to their assumed species. Because we could not find clearly pure D. praetermissa individuals in Ter Yde, we used pure D. praetermissa individuals from the nature reserve Vaarttaluds (De hert et al., 2011), which were genotyped in the same month as the samples from Ter Yde, as reference in the Structure analysis of this site.

AFLP data were entered as Ploidy = 2 for all individuals, with the second line as missing data. Calculations followed the admixture model of ancestry, assuming correlated allele frequencies. We used prior population information: individuals of known pure origin (Popflag = 1) were used as learning samples to classify individuals of unknown origin. We used a burn-in of 500 000 steps, followed by 1 000 000 iterations, after verifying that the results did not vary significantly across multiple runs. We also tested whether the results changed as we entered the data as only a single line for each individual (Ploidy = 1) under the ‘no admixture’ model, but the results were the same. To determine in which class an individual falls, we used as thresholds Tq = 0·80. We used this less strict threshold in stead of the more commonly used Tq = 0·90 (Burgarella et al., 2009), because the assumption of Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium is probably violated due to the different ploidy levels of the parental species and because D. praetermissa originated from the two other species. Individuals with q ≥ Tq are assigned to the pure-bred category and individuals with q < Tq are assigned to the hybrid category. We also performed a principal co-ordinates analysis (PCO), based on Jaccard distances (with squared lambda as vector scaling), using NTSYSpc2·1 (Rohlf, 2000), to visualize the genetic distances between the parental species and the putative hybrids.

Morphological data

For each plant sampled for DNA analysis, morphological characters from both vegetative and floral parts of the plant were measured. The following vegetative characters were recorded in the field: length and width of the three largest leaves, plant height, stem diameter, inflorescence length, number of flowers, number of leaves, presence of spots on the leaves and presence of a solid or hollow stem. In addition, a large number of flower characters were recorded. For each plant, two to three young flowers were sampled, stored in a denatured ethanol solution and transported to the laboratory. Each flower was dissected and a digital image was taken. The following flower characters were measured using the image analysis software IMAGEJ 1·41 (Rasband, 2011): spur length and width, labellum length and width, length and width of the three lobes of the labellum, length and width of the three sepals, and length and width of the two lateral petals. The following labellum characters were determined based on digital images taken in the field: ground colour on a scale 0–3 (0 = white, 1 = pale pink, 2 = deep pink, 3 = purple), type of markings on a scale 0–5 (0 = no markings, 1 = spots, 2 = spots and dashes, 3 = dashes and loops, 4 = ‘lung’-shaped loops, 5 = ‘w’-shaped loops).

Morphological data were analysed using a principal components analysis (PCA) with Varimax rotation in SPSS 16·0 for Windows (SPSS Inc., 2007). We used the scores obtained for each individual on the first two PCA axes to interpret the main patterns of morphological variation in the data set. The characters used in the analysis are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of morphological characters

| Vegetative characters | |

| 1 | Leaf length, average of the length of the three largest leaves (cm) |

| 2 | Leaf width, average of the width of the three largest leaves (cm) |

| 3 | Number of leaves |

| 4 | Plant height, measured from ground level to apex of inflorescence (cm) |

| 5 | Inflorescence length, measured from lowermost flower to apex of inflorescence (cm) |

| 6 | Stem diameter, measured below inflorescence (mm) |

| 7 | Number of flowers |

| 8 | Stem solid (1)/hollow (0) |

| 9 | Spots on leaves (1/0) |

| Floral characters | |

| 10 | Spur length (mm)/spur width (mm) |

| 11 | Lateral sepal length (mm) |

| 12 | Lateral sepal width (mm) |

| 13 | Middle sepal length (mm) |

| 14 | Middle sepal width (mm) |

| 15 | Lateral petal length (mm) |

| 16 | Lateral petal width (mm) |

| 17 | Labellum length (mm)/labellum width (mm) |

| 18 | Labellum shape index (modified after Pedersen, 2006) |

| 19 | Middle lobe of labellum length (mm) |

| 20 | Middle lobe of labellum width (mm) |

| 21 | Lateral lobe of labellum length (mm) |

| 22 | Lateral lobe of labellum width (mm) |

| 23 | Labellum ground colour, on a scale 0–3 (0 = white, 1 = pale pink, 2 = deep pink, 3 = purple) |

| 24 | Labellum markings, type of markings on a scale 0–5 (0 = no markings, 1 = spots, 2 = spots and dashes, 3 = dashes and loops, 4 = ‘lung’-shaped loops, 5 = ‘w’-shaped-loops) |

Flow cytometric analysis

We used flow cytometry (FCM) to determine the ploidy of pure species and of putative hybrid groups (based on Structure results). At each site, we analysed ten individuals of each pure species and of the different putative hybrid group, unless fewer than ten individuals per group were present. Ten randomly chosen samples were analysed twice to verify the reproducibility of the FCM protocol. High-throughput ploidy analysis was performed on a CyFlow Space (Partec, Münster, Germany) flow cytometer equipped with a light-emitting diode (365 nm), using the protocol described by De Schepper et al. (2001) with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining. Young leaf material (0·5 cm2) was co-chopped with leaf material of diploid Lolium perenne, which was used as internal standard. Analyses were performed using Flomax software (Partec). Ploidy levels were inferred from the peak position ratios on the histograms. At least 2500 nuclei per sample were analysed. Samples resulting in a coefficient of variation higher than 4 % were reanalysed.

Experimental crosses

Experimental crosses were conducted to assess the strength of post-zygotic mating barriers. The following treatments were applied: (1) intraspecific cross-pollination control, (2) interspecific cross-pollination, (3) between hybrids (based on Structure results) and (4) between pure species and hybrids. All crosses were conducted in both directions. For treatments (1) and (2), ten flowers from ten plants were pollinated for each cross. For treatments (3) and (4) five plants (ten flowers per plant) were pollinated for each cross (or less when not enough plants or flowers were available). Prior to pollination, pollinia of the pollinated flowers were removed to prevent self-pollination. After fruit maturation, fruit-set and seed viability were determined for all pollinated plants using methods outlined above.

For each different pollen recipient category, the difference in fruiting success between pure species pollen donors and hybrid pollen donors was tested with a Mann–Whitney U-test (the difference between all the separate pollen donor categories could not be tested as for some crosses data from only one or two plants were available). Also, the difference in seed viability between pure species pollen donors and hybrid pollen donors was tested with a Mann–Whitney U-test for each pollen recipient category. An ANOVA (+ post-hoc Tukey test) and a Kruskal–Wallis test (+ non-parametric multiple comparisons test) were used to statistically compare fruiting success between pure species and hybrids in the field, for Paelsteenpanne and Ter Yde, respectively. To statistically compare seed viability between pure species and hybrids in the field, an ANOVA (+ post-hoc Tukey test) was used.

RESULTS

Molecular analyses

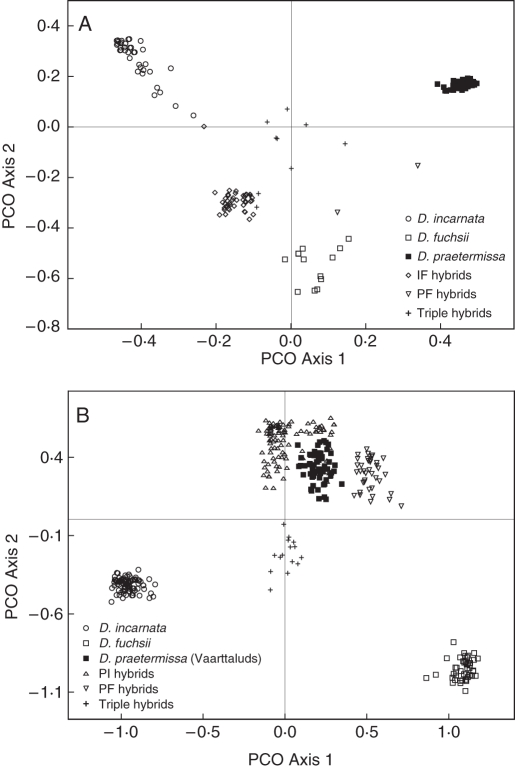

The four AFLP primer combinations generated 195 polymorphic markers for the individuals sampled in Ter Yde, and 190 polymorphic markers for the individuals sampled in Paelsteenpanne. Using Structure, different hybrid groups were detected with a threshold (Tq) of 0·80 (Figs 1 and 2). Figure 3 shows the PCO plots of the parental species and these hybrid groups based on individual genetic distances. The first two PCO axes described 27·84 and 18·52 % of the variation in the case of Paelsteenpanne, and 28·51 and 16·44 % in the case of Ter Yde (Fig. 3). Parental species were clearly separated on the PCO plots. Individuals classified as hybrids according to Structure had intermediate positions between their parental species in the PCO plots. The mean species vs. standard sample ratio of the flow cytometric analysis (FCM ratio) (s.d. among repeats = 0·047; s.d. among samples = 0·081) per Structure group is given in Table 2. Specific and shared bands for the different groups are given in Table 3 and the percentage of polymorphic loci is shown in Table 2.

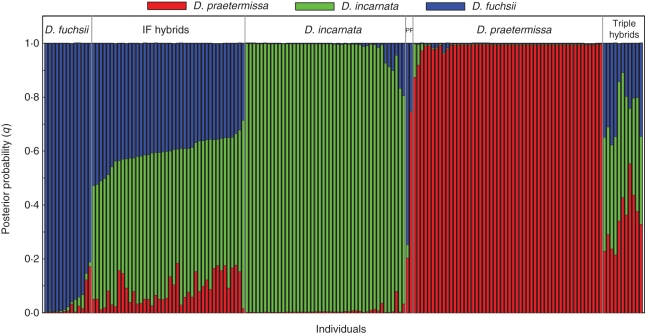

Fig. 1.

Structure clustering results for all individuals obtained for K = 3 in Paelsteenpanne. Each individual is represented by a vertical bar partitioned into K coloured segments, which correspond to the estimated membership proportions for each parental species (D. incarnata, D. fuchsii and D. praetermissa). Posterior probabilities (q) are given on the y-axis. Individuals were assigned to hybrid groups using q = 0·20 as a threshold (see text for details).

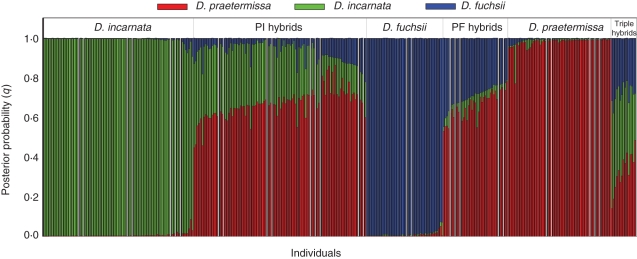

Fig. 2.

Structure clustering results for all individuals obtained for K = 3 in Ter Yde. Each individual is represented by a vertical bar partitioned into K coloured segments, which correspond to the estimated membership proportions for each parental species (D. incarnata, D. fuchsii and D. praetermissa). Posterior probabilities (q) are given on the y-axis. Individuals were assigned to hybrid groups using q = 0·20 as a threshold (see text for details).

Fig. 3.

Principal co-ordinates analysis (PCO) of parental species and putative hybrids based on individual genetic distances determined from 190 polymorphic AFLP markers in Paelsteenpanne (A) and 195 polymorphic AFLP markers in Ter Yde (B). The first two axes described 27·84 and 18·52 % of the variation in (A) and 28·51 and 16·44 % of the variation in (B).

Table 2.

Results of flow cytometric analysis and percentage of polymorphic loci (PLP) for the populations Ter Yde and Paelsteenpanne

| Ter Yde |

Paelsteenpanne |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category | FCM ratio | PLP (%) | FCM ratio | PLP (%) |

| D. incarnata (2n = 40) | 3·14 (0·06) | 54·36 | 3·05 (0·05) | 45·26 |

| D. fuchsii (2n = 40) | 2·41 (0·03) | 53·33 | 2·49 (0·06) | 46·84 |

| IF hybrids | / | / | 2·77 (0·06) | 54·74 |

| D. praetermissa (2n = 80) | / | (62·05)* | 5·48 (0·10) | 13·68 |

| PI hybrids | 4·30 (0·05) | 66·15 | / | / |

| PF hybrids | 3·94 (0·07) | 67·18 | 4·12 | (32·11)† |

| Triple hybrids | 2·74 (0·05) | 62·56 | 4·39 (0·08) | 42·63 |

The mean (± s.d.) FCM ratio of Dactylorhiza vs. Lolium of ten individuals per group (or less when fewer than ten individuals were available) is given. Individuals were assigned to hybrid groups based on the Structure results. / = category not present.

* Value of D. praetermissa individuals in Vaarttaluds.

† Based on the only two individuals.

Table 3.

Number of specific AFLP bands for each species and number of shared bands between all different groups for each site

| D. incarnata | D. fuchsii | D. praetermissa | IF hybrids | PF hybrids | Triple hybrids | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (a) Paelsteenpanne (total number of bands = 190) | ||||||

| D. incarnata | 40 | |||||

| D. fuchsii | 44 | 32 | ||||

| D. praetermissa | 56 | 56 | 8 | |||

| IF hybrids | 81 | 80 | 72 | |||

| PF hybrids | 55 | 75 | 76 | 81 | ||

| Triple hybrids | 66 | 77 | 77 | 93 | 90 | |

| (b) Ter Yde (total numer of bands = 195) | ||||||

| D. incarnata | 14 | |||||

| D. fuchsii | 73 | 9 | ||||

| (D. praetermissa) | 117 | 104 | 9 | |||

| PI hybrids | 126 | 106 | 153 | |||

| PF hybrids | 124 | 115 | 156 | 158 | ||

| Triple hybrids | 124 | 109 | 147 | 148 | 158 | |

In Paelsteenpanne, by far the largest group of hybrids is that between the diploids D. incarnata and D. fuchsii (Fig. 1). These IF hybrids have an intermediate position between D. incarnata and D. fuchsii in the PCO plot (Fig. 3A) and their FCM ratio (2·77) is between that of D. incarnata (3·05) and D. fuchsii (2·49) (Table 2). Two hybrids between D. fuchsii and D. praetermissa were detected by Structure. The FCM ratio of these PF individuals (4·12) was between those of D. praetermissa (5·48) and D. fuchsii (2·49). According to Structure, a third group of hybrids had a part of all three species in their genome (q > 0·2) (Fig. 1). On the PCO these individuals lie in a central position, among all three pure species (Fig. 3A). Their FCM ratio was 4·39.

In Ter Yde, different hybrid groups were detected with Structure (Fig. 2), which were also visible in the PCO plot (Fig. 3B). Hybrid individuals between D. incarnata and D. praetermissa were abundant (Fig. 2). These PI hybrids had a ploidy level ratio (4·30) that was between that of D. incarnata (3·14) and D. praetermissa (5·48; value of Paelsteenpanne). Hybrids between D. fuchsii and D. praetermissa were also detected by Structure (Fig. 2). The ploidy level ratio of these PF hybrids (3·94) was intermediate between their parental species (D. praetermissa, 5·48; D. fuchsii, 2·41), in accordance with the Structure results. Both PI and PF hybrids have a larger proportion in their genome originating from D. praetermissa than from the other parental species (Fig. 2) and lie closer to D. praetermissa on the PCO. A third group of hybrids had contributions of all three species to their genome (q > 0·2), according to Structure (Fig. 2), and had a more or less central position on the PCO (Fig. 3B). The FCM ratio of these individuals was 2·74.

Morphological analyses

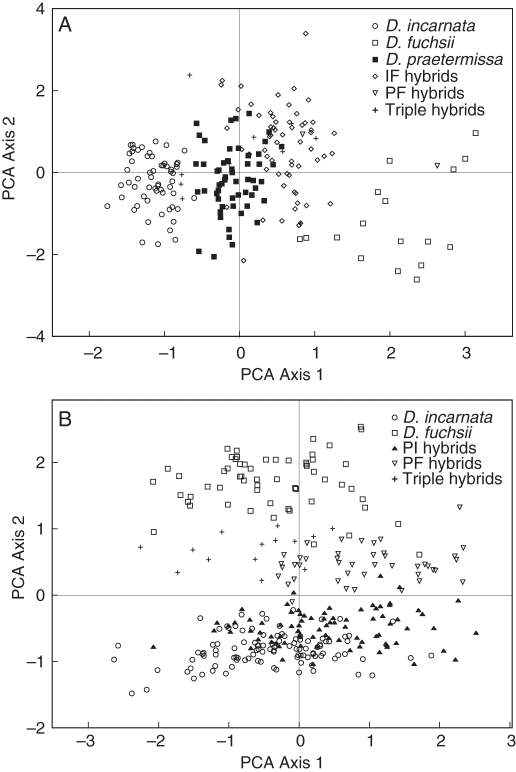

Results of the molecular analyses were largely confirmed by the morphological analyses. The first two axes of the PCA on morphological data for Paelsteenpanne described 30·62 and 22·51 % of the variation, respectively (Fig. 4A). A complete list of the vector loadings of all the different characters for both sites is given in the Appendix. The main characters are also indicated. The three parental species are clearly separated on the PCA. D. praetermissa is intermediate between D. incarnata and D. fuchsii, although its position is closer to D. incarnata. The largest group of hybrids, the IF hybrids, is intermediate between its parental species D. incarnata and D. fuchsii, but closer to D. fuchsii. The putative triple hybrids have no distinct position, but are mainly situated near the central part of the plot.

Fig. 4.

Principal component analysis (PCA) of parental species and putative hybrids based on morphological characters. (A) Individuals sampled in Paelsteenpanne. The first two axes described 30·62 and 22·51 % of the variation. (B) Individuals sampled in the Ter Yde. The first two axes described 27·10 and 20·45 % of the variation.

For Ter Yde, the first two axes of the PCA described 27·10 and 20·45 % of the variation, respectively (Fig. 4B). The two pure species D. incarnata and D. fuchsii are clearly separated on the PCA. The three different hybrid groups tended to cluster separately. The putative triple hybrids lie between D. incarnata and D. fuchsii, mainly near the centre of the PCA.

Fitness of natural hybrids and artificial crosses

In naturally pollinated plants, there was no clear difference in fruiting success between parental species and hybrid groups at the two sites (Table 4). Seed viability, on the other hand, showed very clear differences. In Ter Yde, seed viability of both pure species (D. incarnata, 68·87 %; D. fuchsii, 49·80 %) was significantly higher than that of the three hybrid groups [ranging from 0·07 to 14·23 %, Table 4; post-hoc Tukey, P < 0·001 (for D. fuchsii – PF: P = 0·008)]. In Paelsteenpanne, seed viability of both pure species (D. incarnata, 57·16 %; D. praetermissa, 67·46 %; D. fuchsii produced no fruits in the year of collection) was significantly higher than that of all the hybrid classes (ranging from 0·11 to 0·69 %, Table 4; post-hoc Tukey, P < 0·001). Only one hybrid class, the PF hybrids in Ter Yde, had a relatively high percentage of viable seeds (14·23 %), compared with the other hybrid classes.

Table 4.

Fruit-set and seed viability in natural populations

| Fruit-set (%) |

Seed viability (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ter Yde | Paelsteenpanne | Ter Yde | Paelsteenpanne | |

| D. incarnata | 50·27a (91) | 53·92ac (44) | 68·87a | 57·16a |

| D. fuchsii | 14·17b (46) | 24·05b (11) | 49·80a | – |

| D. praetermissa | / | 63·06c (52) | / | 67·46a |

| PI hybrids | 30·40c (104) | / | 4·67b | / |

| PF hybrids | 20·62b (39) | 61·10 (2) | 14·23b | 0·48 |

| IF hybrids | / | 48·54a (45) | / | 0·11b |

| Putative triple hybrids | 26·90bc (15) | 41·66ab (7) | 0·07b | 0·69b |

Values with different superscripts indicate that they are significantly different at the α = 0·05 level (fruit-set; Ter Yde: non-parametric multiple comparisons, Paelsteenpanne: post-hoc Tukey) or α = 0·01 level (seed viability; post-hoc Tukey). The number of sampled individuals in each group is given in parentheses.

Notes: / = category not present; – = fruits not present for this category.

The results of the experimental crosses confirm pollination in natural conditions (Table 5). When pure species were used as pollen donor, fruit-set was high (mean 89·85 %), but when hybrids served as pollen donor, fruit-set was very low (mean 3·13 %; Table 5A). This difference was significant for all six pollen recipient categories (Mann–Whitney U, P < 0·01; P < 0·05 for PI hybrids). When pure species were pollinated with pure species pollen, a high percentage of viable seeds was formed, but when hybrid pollen were used almost no viable seeds were formed. This difference was significant for all three pure species (Mann–Whitney U, P < 0·01). When hybrids were pollinated with pure species pollen or hybrid pollen, seed viability was very low in both cases. No significant differences were observed for all three hybrid classes.

Table 5.

(A) Fruit-set (%) and (B) seed viability (%) produced from experimental crosses

| Pollen donor |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pollen recipient | D. fuchsii | D. incarnata | D. praetermissa | IF hybrids | PF hybrids | PI hybrids |

| (A) Fruit-set | ||||||

| D. fuchsii | 99 (0·82) | 96·7 (7·07) | 96 (6·2) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| D. incarnata | 95 (5·27) | 100 (0) | 98 (6·32) | 0 (0) | 5·56 (9·82) | – |

| D. praetermissa | 99 (3·16) | 96 (5·16) | 100 (0) | – | – | – |

| IF hybrids | 80 (28·28) | 50·9 (33·36) | – | 0 (0) | 0 | 5·56 (9·82) |

| PF hybrids | 78·06 (10·6) | 77·78 (38·68) | – | 0 | 0 (0) | 12·5 (15) |

| PI hybrids | 100 (0) | – | – | 0 (0) | 20 (28·28) | – |

| (B) Seed viability | ||||||

| D. fuchsii | 58·31 (15·45) | 43·44 (24·39) | 74·05 (10·1) | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| D. incarnata | 35·23 (23·94) | 49·42 (15·29) | 51·08 (25·84) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | – |

| D. praetermissa | 86·19 (5·77) | 77·85 (7·02) | 85·18 (3·77) | – | – | – |

| IF hybrids | 0 (0) | 0·23 (0·29) | – | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 (0) |

| PF hybrids | 1·95 (0·57) | 0·43 (0·75) | – | 0 | 0 (0) | 0·55 (1·09) |

| PI hybrids | 0·7 (0·53) | – | – | 0 (0) | 0·06 (0·09) | – |

– = no data available because of drought or herbivore damage. Standard deviations are given in parentheses.

Only when intra- and interspecific crosses between pure species were conducted was there a high percentage of viable seeds (mean 62·31 %) (Table 5B). When hybrids were involved as either pollen-receptor or pollen-donor, almost no viable seeds were formed (mean 0·26 %). For some crosses there are little or no data of fruit/seed-set because of herbivore damage or because some plants suffered from drought.

DISCUSSION

Hybridization

The three studied Dactylorhiza species are often found growing together in dune habitats, which may provide ideal conditions for hybridization. In this study, we characterized the genetic structure of two natural hybrid zones, where the three species co-occurred. Both Structure and PCO results provided evidence for frequent hybridization between Dactylorhiza species at both study sites, although the extent of hybridization between species varied substantially between the two sites. These results confirm earlier findings that the genetic structure of hybrid zones can differ (Burke and Arnold, 2001).

The AFLP markers combined with detailed cytometric analyses enabled us to assign individuals to specific hybrid classes. In Paelsteenpanne, by far the largest group of hybrids was between the diploids D. incarnata and D. fuchsii. Triploid hybrids between D. incarnata and D. praetermissa, and between D. fuchsii and D. praetermissa were abundant in Ter Yde, whereas these hybrids were rather rare or even absent in Paelsteenpanne. This is remarkable, as no pure D. praetermissa individuals were present at Ter Yde. Perhaps the triploid hybrids were better adapted to (changing) dune slack conditions than D. praetermissa and have outcompeted their tetraploid parent.

Despite the marked differences between sites, our results provide clear evidence that hybridization between all species pairs is possible. This is in accordance with previous work on Dactylorhiza species. Triploid hybrids between D. fuchsii and D. praetermissa were revealed through chromosome counts in a study of Heslop-Harrison (1953). Shaw (1998) detected hybrids between D. incarnata and D. praetermissa, and between D. fuchsii and D. praetermissa, based on morphology. Shipunov et al. (2005) argued that some D. baltica individuals were possibly primary, diploid hybrids between D. incarnata and D. fuchsii. Hedrén (1996a) found a few putative hybrids between D. incarnata and D. fuchsii in some sympatric populations.

Several scenarios could be responsible for the difference in frequency of the hybrid groups at the two sites. Different colonization histories or differences in phenology between the sites may have caused the observed difference in hybridization frequency. In Paelsteenpanne, D. praetermissa individuals lie mainly in one corner of the dune slack. This somewhat isolated position could explain the very few hybrids with D. praetermissa as a parent. The order of the flowering peaks of the three species is D. incarnata, D. praetermissa and D. fuchsii. The absence of IF hybrids in Ter Yde may therefore result from the small overlap in flowering curves between D. incarnata and D. fuchsii (results not shown). The high abundance of PI and PF hybrids in Ter Yde is probably the result of the intermediate flowering time of D. praetermissa. Another explanation for the absence of certain hybrid groups could be that hybrids may disappear after a number of years as they produce almost no viable seeds.

Hybrid origin

Most hybrids in our two study areas are probably F1 hybrids, according to the Structure (Figs 1 and 2) and flow cytometric results (Table 2). The FCM ratio of the IF hybrids (2·77) is between that of D. incarnata (3·05) and D. fuchsii (2·49) (Table 2), and these hybrids also have an intermediate position between these two species (Fig. 3A). The PI hybrids had an FCM ratio (4·30) that was between that of D. incarnata (3·14) and D. praetermissa (5·48; value of Paelsteenpanne). The FCM ratio of the PF hybrids (3·94) was intermediate between its parental species (D. praetermissa, 5·48; D. fuchsii, 2·41). Moreover, most hybrid groups showed more or less intermediate morphological positions between their parental species, indicating that most hybrids combine characters of both parents. This is in agreement with several other studies that have reported orchid hybrids that were morphologically intermediate between their parental species (e.g. Caputo et al., 1997; Nielsen, 2000; Cozzolino et al., 2006; Moccia et al., 2007). However, in the case of hybridization involving D. praetermissa, it was shown that both the PI and the PF hybrid groups in Ter Yde had a larger proportion coming from D. praetermissa than from the other parental species (Fig. 2), and were skewed towards D. praetermissa on the PCO. In this case, higher similarity towards the allotetraploid D. praetermissa was expected a priori, as this species has the largest genome of the three pure species considered here and hence contributes two-thirds of its genome to the triploid hybrids. The fact that most sampled hybrids were probably F1 hybrids is in accordance with data from many other Dactylorhiza studies (e.g. Heslop-Harrison, 1953; Rossi et al., 1995; Hedrén et al., 2001; Aagaard et al., 2005).

Triple hybrids

At both sites a central group of hybrids with a part of all three species in their genome (q > 0·2) was present, suggesting the presence of triple hybrids and thus providing evidence that hybrids between two species can cross with a third species. The occurrence of natural triple hybrids in the field has rarely been reported (Kaplan and Fehrer, 2007) and to our knowledge this is the first time that putative triple hybrids are reported in Dactylorhiza species. In particular, molecular evidence for three different species contributing to natural hybrid individuals is scarce, although some exceptions can be found, including Aesculus (dePamphilis and Wyatt, 1990), Iris (Arnold, 1993), Quercus (Dodd and Afzal-Rafii, 2004) and Potamogeton (Kaplan and Fehrer, 2007).

According to their FCM ratio (4·39), the individuals in Paelsteenpanne could be back-crosses of IF hybrids (2·77) with D. praetermissa (5·48). The triple hybrids in Ter Yde could be back-crosses of PI hybrids with D. fuchsii or back-crosses of PF hybrids with D. incarnata. The expected FCM ratio of these individuals should be around 3·5, which is higher than the actual value (2·74). However, it is possible that hybrids have a lower genome size than expected because of chromosome rearrangements in the genome of the hybrids (Van Laere et al., 2009). Nonetheless, clearly different genome sizes between the triple hybrid groups can suggest a different hybridization history. Given that D. praetermissa has not been detected in the current survey, another possibility would be that the triple hybrids from Ter Yde are in fact hybrids between D. incarnata and D. fuchsii, which could explain their low FCM ratio. However, this is not in accordance with the Structure results, which clearly show an influence of D. praetermissa in these hybrids.

Hybridization across different ploidy levels

Hybridization was observed both between species with the same and with different ploidy levels. The occurrence of putative triple hybrids suggests the possibility of back-crossing. Our crossing experiment, which showed some hybrid fertility, also suggests the possibility of gene flow between different ploidy levels. These results confirm previous studies that have reported hybridization between polyploid derivatives and their diploid progenitors (Aagaard et al., 2005; Ståhlberg and Hedrén, 2009; Pinheiro et al., 2010). Ståhlberg and Hedrén (2009) found relatively few triploid hybrids in a hybrid zone of the diploid D. fuchsii and the autotetraploid D. maculata. Their data also gave indications that some gene flow between ploidy levels is occurring. In his study on morphological intermediates between D. fuchsii and the tetraploids D. purpurella and D. praetermissa, Heslop-Harrison (1953) concluded that most hybrids were eutriploids and showed a high level of seed-sterility. Similarly, Lord and Richards (1977) found both eutriploid hybrids and aneuploid individuals in a hybrid swarm of the diploid D. fuchsii and tetraploid D. purpurella. The appearance of aneuploids was consistent with F2 and back-crossed individuals, which suggests that the triploids were by no means totally sterile. Significant numbers of triploid hybrids were also found by Aagaard et al. (2005), who examined a hybrid zone between diploid D. incarnata ssp. cruenta and its putative allotetraploid derivative D. lapponica. The results of their study suggested back-crossing between the triploid hybrids and D. lapponica, and hence some hybrid fertility. Several studies found indications of introgression between Dactylorhiza species (Hedrén, 2003; Shipunov et al., 2004, 2005; Devos et al., 2005; Pillon et al., 2007; Pedersen, 2006).

Post-mating isolation

As both intra- and interspecific crosses yielded a high fruit-set, no post-mating pre-zygotic isolation was present. Viable seeds were obtained in both directions for all interspecific crosses, indicating that early post-mating post-zygotic barriers were weak. This is in agreement with Ståhlberg and Hedren (2009) who found that both diploids and tetraploids may act as the maternal parent. Experimental crosses performed by Pinheiro et al. (2010) revealed that hybridization occurred in both directions in Epidendrum fulgens and E. puniceoluteum. The results of the genetic analyses and flow cytometry clearly show the presence of F1 hybrids between all species pairs, indicating that hybrid inviability is not a reproductive barrier either.

The experimental crosses further showed that only when the pollen donor is a pure species is fruit-set high (Table 4A) and that only crosses between pure species yielded a high percentage of viable seeds (Table 4B). When hybrids were involved as either pollen-receptor or pollen-donor, almost no viable seeds were formed. These results thus suggest that hybrid sterility is the major cause hampering hybridization to extend beyond the F1 generation, and confirm previous studies in Dactylorhiza. For example, Heslop-Harrison (1953) found highly sterile triploid hybrids between D. fuchsii and D. praetermissa. Rossi et al. (1995) suggested hybrid sterility as the cause of the lack of recombinant hybrid classes between D. romana and D. saccifera.

However, some authors found viable seeds of certain hybrid classes when they performed experimental crosses between Dactylorhiza species (Malmgren, 1992; Bateman and Haggar, in press). We found also some viable seeds in our experimental crosses. Moreover, in some naturally pollinated groups, also relatively high seed viability percentages were observed. The PI hybrids and, in particular, the PF hybrids of Ter Yde showed a remarkably higher seed viability than the IF hybrids of Paelsteenpanne. This could indicate that triploid hybrids between one of the diploid species and the tetraploid species have a higher fertility than hybrids between the two diploid species, which could suggest a stronger reproductive isolation between the two diploid species than between a diploid and the tetraploid species. Some hybrid viability can be expected as triploids are known to produce fertile hyperdiploid (2x + 1) and hypotetraploid (4x – 1) offspring occasionally (Ramsey and Schemske, 1998).

Allopolyploid formation

Allotetraploid members of Dactylorhiza have evolved on multiple occasions (Hedrén, 1996a, 2003). However, little is known about how new polyploids arise. One possible genetic pathway is that fertile triploid hybrids act as a bridge in the formation of new polyploid species (Ramsey and Schemske, 1998; Coyne and Orr, 2004). Our findings lend some support to this hypothesis. As some seed viability was found in our hybrids and also hybrids with three different parents were found, there is strong evidence for the presence of secondary gene flow. Through this secondary gene flow the present diploid or triploid hybrids can further lead to the formation of new allopolyploids.

Conclusions

Frequent hybridization was observed at both study sites and hybridization was possible between all species pairs. Our molecular and flow cytometric data suggest that most hybrids are F1 hybrids. However, the presence of putative triple hybrids indicates that hybrids between two species can cross with a third species, which suggests secondary gene flow and the possibility of back-crossing. Crossing experiments and data from the field revealed low seed viability percentages of most hybrids, which indicates strong post-zygotic barriers. These reproductive barriers probably prevent the local breakdown of species boundaries in Dactylorhiza despite frequent hybridization between parental species.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank K. Libaut, S. Provoost and P. De Raeymaecker for assistance, M. Leten for useful information, and ANB and Natuurpunt for permission to conduct our research in the Ter Yde and Paelsteenpanne nature reserves. A grant from the Flemish fund for scientific research (FWO) [G.0592·08] is gratefully acknowledged. H.J. holds a postdoc fellowship from ERC [ERC starting grant 260601 – MYCASOR] and K.V. holds a postdoc fellowship from FWO.

APPENDIX

Contributions of morphological characters to the first two multivariate axes of the PCA, which described 30·62 and 22·51 % of the variation, respectively, for Paelsteenpanne and 27·10 and 20·45 % of the variation, respectively, for Ter Yde. The most important characters are in bold type.

| Paelsteenpanne |

Ter Yde |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Component 1 | Component 2 | Component 1 | Component 2 | ||

| 1 | Leaf length | –0·360 | 0·180 | 0·158 | 0·072 |

| 2 | Leaf width | –0·031 | 0·137 | 0·086 | –0·087 |

| 3 | Number of leaves | 0·716 | 0·215 | 0·012 | 0·607 |

| 4 | Plant height | 0·117 | 0·139 | 0·247 | 0·423 |

| 5 | Inflorescence length | –0·079 | 0·180 | 0·097 | 0·037 |

| 6 | Stem diameter | –0·343 | 0·212 | 0·003 | –0·435 |

| 7 | Number of flowers | 0·159 | 0·231 | 0·064 | 0·290 |

| 8 | Stem solid/hollow | 0·555 | –0·039 | –0·188 | 0·805 |

| 9 | Leafspots | 0·722 | 0·219 | 0·055 | 0·876 |

| 10 | Spur length/width | 0·599 | –0·148 | –0·073 | 0·461 |

| 11 | Lateral sepal length | –0·279 | 0·313 | 0·867 | –0·007 |

| 12 | Lateral sepal width | 0·163 | 0·694 | 0·736 | –0·197 |

| 13 | Middle sepal length | –0·346 | 0·344 | 0·822 | 0·103 |

| 14 | Middle sepal width | 0·116 | 0·651 | 0·759 | –0·043 |

| 15 | Lateral petal length | –0·492 | 0·533 | 0·869 | –0·037 |

| 16 | Lateral petal width | 0·199 | 0·761 | 0·751 | –0·046 |

| 17 | Labellum length/width | –0·565 | –0·304 | –0·315 | –0·584 |

| 18 | Labellum shape index | –0·934 | 0·050 | –0·043 | –0·911 |

| 19 | Middle lobe of labellum length | 0·848 | 0·040 | 0·202 | 0·869 |

| 20 | Middle lobe of labellum width | 0·587 | 0·288 | 0·535 | 0·271 |

| 21 | Lateral lobe of labellum length | 0·486 | 0·712 | 0·806 | 0·141 |

| 22 | Lateral lobe of labellum width | –0·363 | 0·815 | 0·762 | –0·121 |

| 23 | Labellum ground colour | –0·360 | 0·103 | 0·242 | 0·845 |

| 24 | Labellum type of markings | 0·128 | –0·097 | 0·255 | 0·131 |

LITERATURE CITED

- Aagaard SMD, Såstad SM, Greilhuber J, Moen A. A secondary hybrid zone between diploid Dactylorhiza incarnata ssp. cruenta and allotetraploid D. lapponica (Orchidaceae) Heredity. 2005;94:488–496. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abbott RJ. Plant invasions, interspecific hybridization and the evolution of new plant taxa. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 1992;7:401–405. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(92)90020-C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold ML. Iris nelsonii (Iridaceae): origin and genetic composition of a homoploid hybrid species. American Journal of Botany. 1993;80:577–583. doi: 10.1002/j.1537-2197.1993.tb13843.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold ML. Natural hybridization and evolution. New York: Oxford University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman RM, Denholm I. A reappraisal of the British and Irish dactylorchids, 2. The diploid marsh-orchids. Watsonia. 1985;15:321–355. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman RM, Haggar J. Dactylorhiza Necker ex Nevski. In: Stace CA, editor. Hybridization and the Flora of the British Isles. London: Botanical Society of the British Isles; In press. [Google Scholar]

- Barton NH, Hewitt GM. Adaptation, speciation and hybrid zones. Nature. 1989;341:497–503. doi: 10.1038/341497a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bournérias M, Prat D. Les Orchidées de France, Belgique et Luxembourg. 2nd edn. Mèze: Biotope; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Burgarella C, Lorenzo Z, Jabbour-Zahab R, et al. Detection of hybrids in nature: application to oaks (Quercus suber and Q. ilex) Heredity. 2009;102:442–452. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2009.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JM, Arnold ML. Genetics and the fitness of hybrids. Annual Review of Genetics. 2001;35:31–52. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.35.102401.085719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caputo P, Aceto S, Cozzolino S, Nazzaro R. Morphological and molecular characterization of a natural hybrid between Orchis laxiflora and O. morio (Orchidaceae) Plant Systematics and Evolution. 1997;205:147–155. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman MA, Abbott RJ. Introgression of fitness genes across a ploidy barrier. New Phytologist. 2010;186:63–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.03091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne JA, Orr HA. Speciation. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Cozzolino S, Nardella AM, Impagliazzo S, Widmer A, Lexer C. Hybridization and conservation of Mediterranean orchids: should we protect the orchid hybrids or the orchid hybrid zones? Biological Conservation. 2006;129:14–23. [Google Scholar]

- De hert K, Jacquemyn H, Van Glabeke S, et al. Patterns of hybridization between diploid and derived allotetraploid species of Dactylorhiza (orchidaceae) co-occurring in Belgium. American Journal of Botany. 2011;98:946–955. doi: 10.3732/ajb.1000367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Schepper S, Leus L, Mertens M, et al. Flow cytometric analysis of ploidy in Rhododenron (subgenus Tsutsusi) Hortscience. 2001;36:125–127. [Google Scholar]

- Devos N, Oh S-H, Raspé O, Jacquemart A-L, Manos PS. Nuclear ribosomal DNA sequence variation and evolution of spotted marsh-orchids (Dactylorhiza maculata group) Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2005;36:568–580. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos N, Raspé O, Oh S-H, Tyteca D, Jacquemart A-L. The evolution of Dactylorhiza (Orchidaceae) allotetraploid complex: insights from nrDNA sequences and cpDNA PCR-RFLP data. Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2006;38:767–778. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd RS, Afzal-Rafii Z. Selection and dispersal in a multispecies oak hybrid zone. Evolution. 2004;58:261–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software Structure: a simulation study. Molecular Ecology. 2005;14:2611–2620. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferdy J-B, Loriot S, Sandmeier M, Lefranc M, Raquin C. Inbreeding depression in a rare deceptive orchid. Canadian Journal of Botany. 2001;79:1181–1188. [Google Scholar]

- Hedrén M. Genetic differentiation, polyploidization and hybridization in northern European Dactylorhiza (Orchidaceae): evidence from allozyme markers. Plant Systematics and Evolution. 1996a;201:31–55. [Google Scholar]

- Hedrén M. The allotetraploid nature of Dactylorhiza praetermissa (Druce) Soó (Orchidaceae) confirmed. Watsonia. 1996b;21:113–118. [Google Scholar]

- Hedrén M. Plastid DNA variation in the Dactylorhiza incarnata/maculata polyploid complex and the origin of allotetraploid D. sphagnicola (Orchidaceae) Molecular Ecology. 2003;12:2669–2680. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2003.01930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedrén M, Fay MF, Chase MW. Amplified fragment length polymorphisms (AFLP) reveal details of polyploid evolution in Dactylorhiza (Orchidaceae) American Journal of Botany. 2001;88:1868–1880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heslop-Harrison J. Microsporogenesis in some triploid Dactylorchid hybrids. Annals of Botany. 1953;17:539–549. [Google Scholar]

- Heslop-Harrison J. Some observations on Dactylorchis incarnata (L.) Vermln. in the British Isles. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London. 1956;166:51–82. [Google Scholar]

- Heslop-Harrison J. On the hybridization of the common spotted orchid, Dactylorchis fuchsii (Druce) Vermln., with the marsh orchids D. praetermissa (Druce) Vermln., and D. purpurella (T & TA Steph) Vermln. Proceedings of the Linnean Society of London. 1957;167:176–185. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan Z, Fehrer J. Molecular evidence for a natural primary triple hybrid in plants revealed from direct sequencing. Annals of Botany. 2007;99:1213–1222. doi: 10.1093/aob/mcm072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambinon J, De Langhe J-E, Delvosalle L, Duvigneaud J. Flora van België, het Groothertogdom Luxemburg, Noord-Frankrijk en de aangrenzende gebieden. Meise: Nationale Plantentuin van België; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lammi A, Kuitunen M. Deceptive pollination of Dactylorhiza incarnata: an experimental test of the magnet species hypothesis. Oecologia. 1995;101:500–503. doi: 10.1007/BF00329430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammi A, Vallius E, Vauhkonen T, Kuitunen M. Outcrossing, hybridization, pollen quantity, and the evolution of deceptive pollination in Dactylorhiza incarnata. Annales Botanici Fennici. 2003;40:331–338. [Google Scholar]

- Lefort F, Douglas GC. An efficient micro-method of DNA isolation from mature leaves of four hardwood tree species Acer, Fraxinus, Prunus and Quercus. Annals of Forest Science. 1999;56:259–263. [Google Scholar]

- Lord RM, Richards AJ. A hybrid swarm between the diploid Dactyloriza fuchsii (Druce) Soó and the tetraploid D. purpurella (T. & T. A. Steph.) Soó in Durham. Watsonia. 1977;11:205–210. [Google Scholar]

- Malmgren S. Crossing and cultivation experiments with Swedish orchids. Svensk Botanisk Tidskrift. 1992;86:337–346. [Google Scholar]

- Mattila E, Kuitunen M. Nutrient versus pollination limitation in Platanthera bifolia and Dactyloriza incarnata (Orchidaceae) Oikos. 2000;89:360–366. [Google Scholar]

- Moccia MD, Widmer A, Cozzolino S. The strength of reproductive isolation in two hybridizing food-deceptive orchid species. Molecular Ecology. 2007;16:2824–2837. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03240.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen LR. Natural hybridization between Vanilla claviculata (W.Wright) Sw. and V. barbellata Rchb.f. (Orchidaceae): genetic, morphological, and pollination experimental data. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 2000;133:285–302. [Google Scholar]

- Nordström S, Hedrén M. Genetic differentiation and postglacial migration of the Dactylorhiza majalis ssp. traunsteineri/lapponica complex into Fennoscandia. Plant Systematics and Evolution. 2008;276:73–87. [Google Scholar]

- Otto SP, Whitton J. Polyploid incidence and evolution. Annual Review of Genetics. 2000;34:401–437. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen HÆ. Systematics and evolution of the Dactylorhiza romana/sambucina polyploid complex (Orchidaceae) Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 2006;152:405–434. [Google Scholar]

- Petit C, Bretagnolle F, Felber F. Evolutionary consequences of diploid–polyploid hybrid zones in wild species. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 1999;14:306–311. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(99)01608-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- dePamphilis CW, Wyatt R. Electroforetic confirmation of interspecific hybridization in Aesculus (Hippocastaneaceae) and the genetic structure of a broad hybrid zone. Evolution. 1990;44:1295–1317. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1990.tb05233.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pillon Y, Fay MF, Hedrén M, et al. Evolution and temporal diversification of western European polyploid species complexes in Dactylorhiza (Orchidaceae) Taxon. 2007;56:1185–1208. [Google Scholar]

- Pinheiro F, De Barros F, Palma-Silva C, et al. Hybridization and introgression across different ploidy levels in the Neotropical orchids Epidendrum fulgens and E. puniceoluteun (Orchidaceae) Molecular Ecology. 2010;19:3981–3994. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04780.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics. 2000;155:945–959. doi: 10.1093/genetics/155.2.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey J, Schemske DW. Pathways, mechanisms, and rates of polyploid formation in flowering plants. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1998;29:467–501. [Google Scholar]

- Rasband WS. ImageJ. 2011 Bethesda, MD: US National Institutes of Health, http://imagej.nih.gov/ij/ [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg LH. Hybrid origins of plant species. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 1997;28:359–389. [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg LH, Carney SE. Tansley Review No. 102. Plant hybridization. New Phytologist. 1998;140:599–624. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.1998.00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg LH, Willis JH. Plant speciation. Science. 2007;317:910–914. doi: 10.1126/science.1137729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlf FJ. NTSYS, Numerical taxonomy and multivariate analysis system (2·1) New York: Applied Biostatistics Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi W, Arduino P, Cianchi R, Piemontese N, Bullini L. Genetic divergence between Dactylorhiza romana and D. saccifera (Orchidaceae), with description of their natural hybrid. Webbia. 1995;50:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Scopece G, Musacchio A, Widmer A, Cozzolino S. Patterns of reproductive isolation in Mediterranean deceptive orchids. Evolution. 2007;61:2623–2642. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scopece G, Widmer A, Cozzolino S. Evolution of postzygotic reproductive isolation in a guild of deceptive orchids. The American Naturalist. 2008;171:315–326. doi: 10.1086/527501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw PJA. Morphometric analyses of mixed Dactylorhiza colonies (Orchidaceae) on industrial waste sites in England. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 1998;128:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Shipunov AB, Fay MF, Pillon Y, Bateman RM, Chase MW. Dactylorhiza (Orchidaceae) in European Russia: combined molecular and morphological analysis. American Journal of Botany. 2004;91:1419–1426. doi: 10.3732/ajb.91.9.1419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipunov AB, Fay MF, Chase MW. Evolution of Dactylorhiza baltica (Orchidaceae) in European Russia: evidence from molecular markers and morphology. Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 2005;147:257–274. [Google Scholar]

- Ståhlberg D, Hedrén M. Habitat differentiation, hybridization and gene flow patterns in mixed populations of diploid and autotetraploid Dactylorhiza maculata s.l. (Orchidaceae) Evolutionary Ecology. 2009;23:295–328. [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins GL. Chromosomal evolution in higher plants. London: Edward Arnold; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson JD, Lumaret R. The evolutionary dynamics of polyploid plants: origins, establishment and persistence. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 1992;7:302–307. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(92)90228-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallius E, Salonen V, Kull T. Factors of divergence in co-occurring varieties of Dactylorhiza incarnata (Orchidaceae) Plant Systematics and Evolution. 2004;248:177–189. [Google Scholar]

- Vallius E, Lammi A, Kuitunen M. Reproductive success of Dactylorhiza incarnata ssp incarnata (Orchidaceae): the effects of population size and plant visibility. Nordic Journal of Botany. 2007;25:183–189. [Google Scholar]

- Van Laere K, Leus L, Van Huylebroeck J, Van Bockstaele E. Interspecific hybridization and genome size analysis in Buddleja. Euphytica. 2009;166:445–456. [Google Scholar]

- Van Waes JM, Debergh PC. Adaptation of the tetrazolium method for testing the seed viability, and scanning electron microscopy study of some Western European orchids. Physiologia Plantarum. 1986;66:435–442. [Google Scholar]

- Vandepitte K, Roldan-Ruiz I, Leus L, Jacquemyn H, Honnay O. Canopy closure shapes clonal diversity and fine-scale genetic structure in the dioecious understorey perennial Mercurialis perennis. Journal of Ecology. 2009;97:404–414. [Google Scholar]

- Vos P, Hogers R, Bleeker M, et al. AFLP: a new technique for DNA-fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Research. 1995;23:4407–4414. doi: 10.1093/nar/23.21.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]