Abstract

Indolequinones (IQs) were developed as potential antitumor agents against human pancreatic cancer. IQs exhibited potent antitumor activity against the human pancreatic cancer cell line MIA PaCa-2 with growth inhibitory IC50 values in the low nanomolar range. IQs were found to induce time- and concentration-dependent apoptosis and to be potent inhibitors of thioredoxin reductase 1 (TR1) in MIA PaCa-2 cells at concentrations equivalent to those inducing growth-inhibitory effects. The mechanism of inhibition of TR1 by the IQs was studied in detail in cell-free systems using purified enzyme. The C-terminal selenocysteine of TR1 was characterized as the primary adduction site of the IQ-derived reactive iminium using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry analysis. Inhibition of TR1 by IQs in MIA PaCa-2 cells resulted in a shift of thioredoxin-1 redox state to the oxidized form and activation of the p38/c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (JNK) mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway. Oxidized thioredoxin is known to activate apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1, an upstream activator of p38/JNK in the MAPK signaling cascade and this was confirmed in our study providing a potential mechanism for IQ-induced apoptosis. These data describe the redox and signaling events involved in the mechanism of growth inhibition induced by novel inhibitors of TR1 in human pancreatic cancer cells.

Introduction

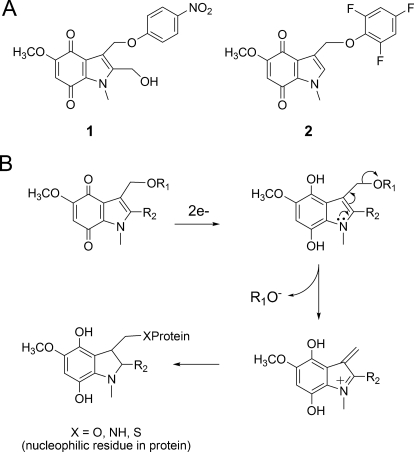

We have previously reported the development of a series of novel indolequinones (IQs) that exhibited marked growth inhibitory effects against human pancreatic cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo (Yan et al., 2009). These compounds share an indolequinone backbone but vary in the substitution pattern on both the quinone ring and the indole ring. Two classes of IQs, namely the 2-hydroxymethyl class [e.g., 2-hydroxymethyl-5-methoxy-1-methyl-3-[(4-nitrophenoxy)methyl]indole-4,7-dione (1); Fig. 1] and the 2-unsubstituted class [e.g., 5-methoxy-1-methyl-3-[(2,4,6-trifluorophenoxy)methyl]indole-4,7-dione (2); Fig. 1], were found to be extremely potent agents against various human pancreatic cancer cell lines with growth inhibitory IC50 values in the low nanomolar range (Yan et al., 2009). Molecules in both classes exhibited a unique pattern of cytotoxicity in the NCI-60 tumor cell line panel showing preferable toxicity against colon, renal, and melanoma cell lines (Yan et al., 2009). The similarity between the NCI-60 activity pattern of the IQs and the previously reported thioredoxin reductase inhibitor 4-(benzothiazol-2-yl)-4-hydroxy-2,5-cyclohexadien-1-one (AW464) (Chew et al., 2008) led to the hypothesis that the human thioredoxin system might be a molecular target of the IQs.

Fig. 1.

Structure of IQs and proposed mechanism of action. A, chemical structure of IQs 1 and 2. B, IQs via reduction and rearrangement can generate a reactive iminium electrophile, which has the potential to alkylate cellular nucleophiles.

The cytosolic thioredoxin system, consisting of thioredoxin-1, thioredoxin reductase 1 (TR1), and NADPH, plays an essential role in maintaining the redox homeostasis of thiols in cellular proteins (Arnér and Holmgren, 2006). The thioredoxin system has many biological activities essential for cell function. First, thioredoxin is involved in antioxidant defense primarily by serving as an electron donor for thioredoxin peroxidases, which uses thiol groups to scavenge oxidants (Berggren et al., 2001). Second, reduced thioredoxin provides reducing equivalents to ribonucleotide reductase, which catalyzes the conversion of ribonucleotides to deoxyribonucleotides (Laurent et al., 1964), one of the key steps in DNA synthesis and cell proliferation. Third, thioredoxin regulates the DNA-binding ability of transcriptional factors such as the glucocorticoid receptor, transcription factor IIIC, nuclear factor-κB, p53, and activator protein-1 (Fos/Jun) by redox control of the cysteine residues in their DNA-binding domain (Cromlish and Roeder 1989; Grippo et al., 1983; Abate et al., 1990; Matthews et al., 1992; Ueno et al., 1999). Finally, and potentially most importantly for the apoptotic effects of the IQs, reduced thioredoxin functions as an inhibitor of apoptosis through binding to apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1 (ASK1) and inhibiting its kinase activity. Oxidized thioredoxin dissociates from ASK1 resulting in ASK1 activation and downstream apoptosis (Ichijo et al., 1997; Saitoh et al., 1998).

Our previous work suggested that targeting human TR1 might be a potential mechanism underlying IQ toxicity (Yan et al., 2009). In this study, we demonstrate that human TR1 is a target of the IQs in human pancreatic cancer cells. The inhibition of TR1 by these IQs was characterized in both cell-free and cellular systems and resulted in activation of a signaling cascade involving ASK1 and p38/JNK MAPKs. These results describe both the redox and signaling events associated with the mechanism of toxicity of IQs in human pancreatic cancer cells.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

The IQs 2-hydroxymethyl-5-methoxy-1-methyl-3-[(4-nitrophenoxy)methyl]indole-4,7-dione (1) and 5-methoxy-1-methyl-3-[(2,4,6-trifluorophenoxy)methyl]indole-4,7-dione (2) were synthesized according to methods previously developed (Colucci et al., 2007). Recombinant human NRH:quinone oxidoreductase 2 (NQO2) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Dihydronicotinamide riboside (NRH) was synthesized in our lab using published procedures (Friedlos et al., 1992; Yan et al., 2008). Recombinant rat TR1 was purchased from IMCO Corporation Ltd. AB (Stockholm, Sweden). Antibodies against TR1, phospho-ASK1 (Ser83), and total ASK1 were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Antibodies against thioredoxin-1, phospho-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182), and phospho-JNK (Thr183/Try185) were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Antibody against cytochrome c was from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). The p38 inhibitor 4-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(4-methylsulfinylphenyl)-5-(4-pyridyl)1H-imidazole (SB203580) and JNK inhibitory peptide l-JNKi were purchased from Enzo Life Sciences, Inc. (Plymouth Meeting, PA). The transfection plasmid pCMV-SPORT6-ASK1 was purchased from Open Biosystems (Huntsville, AL). Annexin-V staining kit and EnzChek fluorescence caspase-3 activity kit were obtained from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). Unless indicated, all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Cell Line and Transfection.

MIA PaCa-2 human pancreatic carcinoma cells were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium adjusted to contain 4 mM l-glutamine, 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum, 2.5% (v/v) horse serum, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin. Cells were maintained in a humidified incubator containing 5% carbon dioxide at 37°C. For transient transfection studies, MIA PaCa-2 cells were transfected by electroporation with the CMV-driven vector pCMV-SPORT6 containing human ASK1 cDNA (Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL) or the vector alone. Cells were then incubated in complete growth medium for 16 h before treatment with IQs.

Growth Inhibition Assay.

Growth inhibition was measured using the MTT colorimetric assay (Mosmann, 1983). In these studies, cells in exponential growth phase were seeded at 2 × 103 cells per well in 96-well plates in triplicate plates and allowed to attach for 16 h. Cells were then treated with IQs in complete medium (200 μl/well) for 72 h or for 4 h followed by incubation in drug-free medium (200 μl/well) for additional 72 h at 37°C. The medium was removed by aspiration, and MTT (50 μg) in complete medium (50 μl) was added to each well and incubated for a further 4 h. Cell viability was determined by measuring the cellular reduction of MTT to the crystalline formazan product, which was dissolved by the addition of 100 μl of DMSO. Optical density was determined at 550 nm using a Thermomax microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). The IC50 values were defined as the concentration of IQ that resulted in 50% reduction in cell number compared with DMSO-treated controls.

Flow Cytometry Analysis of Apoptosis.

Cells (4 × 105) were seeded into a 60-mm Petri dish. After drug treatment, cells were collected, washed with PBS, resuspended in annexin binding buffer, and stained with Annexin-V-fluorescein isothiocyanate and propidium iodide (PI) according to manufacturer's instructions (Biosource Annexin V detection kit; Invitrogen). Annexin-V and PI staining were analyzed using a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Cells with positive annexin-V staining were counted as apoptotic cells.

Caspase-3 Activity Assay.

Caspase-3 activity was determined using the EnzChek caspase-3 assay kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, cells were collected into lysis buffer and sonicated, and caspase-3 activity in the cell lysate was measured fluorometrically by following the cleavage of the substrate N-benzyloxycarbonyl-DEVD-amino-4-methylcoumarin.

Mitochondria Cytochrome c Release.

Cells were harvested and resuspended in permeabilization buffer (200 μg/ml digitonin and 80 mM KCl in PBS). After 5 min incubation on ice, samples were centrifuged at 1000g for 5 min. The supernatant (cytosolic fraction) was transferred to a new tube immediately and the pellet (mitochondria) was resuspended in RIPA buffer. Both fractions were then subjected to immunoblot analysis of cytochrome c. Protein content was determined using the method of Lowry et al. (1951).

Inhibition of TR1 in Cell-Free Systems.

Inhibition reaction was carried out in 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 2 mM EDTA and 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin. A mixture of 0.5 μM recombinant rat TR1, 250 μM NADPH, 2 μM NQO2, and 200 μM NRH were incubated in the above buffer at room temperature for 5 min. Then various concentrations of IQ were added (the final volume of the mixture was 150 μl), and a 20-μl sample was removed every 5 min during a 30-min period and measured for TR1 activity using the 5,5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoid acid) (DTNB) reduction assay, as described previously (Fang et al., 2005). The activity assay mixture contained 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mg/ml bovine serum albumin, 250 μM NADPH, and 2.5 mM DTNB. The release of TNB from DTNB was monitored at 412 nm for 1 min after sample addition and the rate calculated. A blank reading without samples was subtracted from every sample. Results were expressed as percentage of control (20-μl sample removed before addition of IQs) and were representative of three separate experiments.

Detection of IQ-Modified Residues in TR1 Using Mass Spectrometry.

LC-MS/MS experiments were performed using published methods (Cassidy et al., 2006) with slight modifications. A 40-μl solution containing 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.4, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 μg of NQO2, 200 μM NRH, 9 μg of TR1, and 250 μM NADPH, were incubated at room temperature for 15 min. Then 1 μl of 4 mM IQ 1 in DMSO was added, and the mixture was incubated for another 30 min. Proteins in the reaction system were then denatured in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride at 70°C for 30 min. The cysteine residues in the denatured proteins were then modified by dithiothreitol reduction followed by iodoacetamide alkylation. Samples were diluted 10-fold with 50 mM NH4HCO3 and cleaved at a trypsin/protein ratio of 1:50 at 37°C overnight. The digestion product was dried using a SpeedVac (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and reconstituted in 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid. Approximately 10 pmol of the TR1 digests was then purified using a ZipTip C18 device and eluted into 10 μl of 50% acetonitrile and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid in pure water. The purified tryptic digests were analyzed using positive-ion electrospray ionization liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) using an Agilent 1100 capillary high-performance liquid chromatography system interfaced to a quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer (Waters, Milford, MA) equipped with a PicoView Nanospray source (New Objective, Inc., Woburn, MA). Samples were manually injected using a nano injector (Valco Instrument Co, Houston, TX) onto a 1.0 × 150 mm C18 MS column (Grace Vydac, Hesperia, CA). A 16-min gradient of 3 to 80% solvent B (A, 0.1% formic acid; B, 90% acetonitrile/0.1% formic acid) was used at 350 nl/min, at 3% B for the first min, followed by a linear increase to 40% B in 9 min, and finally maintained at 80% B for 3 min. Spectra were recorded on a Waters quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer in positive mode. The scan range for full-scan spectra was set at m/z 400 to 2000. Automated analysis of peptide fragmentation spectra (MS/MS) was performed with the MASCOT (Matrix Science, London, UK) computer algorithm for protein database searching and protein identification. The theoretical isotope distribution of the C-terminal peptide was calculated using the ProteinProspector program (http://prospector.ucsf.edu).

TR1 Activity in Cells.

Cells were collected into RIPA buffer, sonicated, and centrifuged (13,000 rpm × 15 min), and protein concentration in supernatant was determined using the method of Lowry. TR1 activity assay was then performed in a 96-well plate format using an endpoint insulin reduction assay as described previously (Fang et al., 2005). In brief, reactions (50 μl) contained 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 2 mM EDTA, 200 μM NADPH, 1.5 mg/ml insulin, 20 μM Escherichia coli thioredoxin (Sigma), and 40 μg of protein from each cell extract. After incubation for 20 min at 37°C, the reaction was terminated by adding 200 μl of 1 mM DTNB in 6 M guanidine hydrochloride (dissolved in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0). The free thiols in the reduced insulin were determined by DTNB reduction, measured by the absorbance at 412 nm, where 1 mol of disulfide gives rise to 2 mol of free TNB with the extinction coefficient 13.6 mM−1 · cm−1. A blank measurement for each sample, containing everything except thioredoxin, was treated in the same manner, and the blank value was subtracted from the corresponding absorbance value of the sample. The activity of TR1 was expressed as the percentage of DMSO-treated control.

Glutathione Reductase and Glutathione Peroxidase Activity Assays.

Glutathione reductase (GR) activity in cells was measured using methods described previously (Gromer et al., 1998). The assay mixture (1 ml) consisted of 100 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, 2 mm EDTA, and 100 μM NADPH. The consumption of NADPH after addition of the cell sonicates was monitored as the decrease in absorbance at 340 nm in the presence or absence of 1 mM GSSG. GR activity was calculated from the difference in rate of decrease in OD340 between the minus and plus GSSG measurements. Glutathione peroxidase (GPx) activity in cells was determined in a GR-coupled assay described previously (Gromer et al., 1998). The assay mixture (1 ml) containing 50 mm potassium phosphate, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA, 1 units/ml GR, 1 mM GSH, and 200 μM NADPH was equilibrated for 5 min; cell sonicates were added and incubated for 1 min. Then, the substrate t-butylhydroperoxide (final concentration, 1 mM) was added, and the consumption of NADPH was monitored at 340 nm.

GSH/GSSG Ratio Determination.

Frozen cell pellets (2 × 106) were sonicated in 150 μl of ice-cold 0.1 N perchloric acid before thawing to prevent artificial formation of thiol disulfide during preparation. Homogenates were centrifuged at 14,000g for 15 min at 4°C. Levels of both GSH and GSSG in the supernatant were determined using high-performance liquid chromatography methods as reported previously (Liang and Patel 2006) and were normalized to the protein concentrations determined by the method of Lowry et al. (1951).

Total Cellular Nonprotein Thiols.

Total acid-soluble thiols in cells were determined according to published methods (Sedlak and Lindsay 1968). Cells (2 × 106) were collected into ice-cold PBS and divided into two tubes. Cells were then pelleted by centrifugation at 1000g for 5 min. The cell pellet in one tube was resuspended in RIPA buffer for determination of protein concentration using the method of Lowry et al. (1951). The cell pellet in another tube was lysed in 120 μl of 5% trichloroacetic acid, vortexed immediately for 10 s, and then centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min to pellet cellular protein. The supernatant was removed to a glass tube containing 2 ml of 0.4 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.9, and DTNB was added to a final concentration of 100 μM. Samples were vortexed and incubated for 5 min at room temperature, and the absorbance at 412 nm was determined. Results were expressed as micromolar acid-soluble thiols per milligram of protein calculated from a reduced glutathione calibration curve.

Determination of Thioredoxin Redox State in Cells.

Thioredoxin redox state in cells was determined as described previously (Sun and Rigas 2008). In brief, cells were collected into freshly made lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.3, 2 mM EDTA, 6 M guanidine hydrochloride, 0.5% Triton X-100, and 50 mM iodoacetic acid) and incubated at 37°C in dark for 30 min. Cell lysates were then spun through a desalting column (Micro Bio-Spin; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA), and protein concentration was determined using the method of Lowry et al. (1951). The desalted proteins (50 μg) were then separated by 15% native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. Reduced and oxidized thioredoxin-1 was probed with rabbit anti-human thioredoxin-1 antibody and detected using enhanced chemiluminescence.

Immunoblot Analysis.

Cells were seeded in 100-mm culture plates at 106 cells per plate and treated with various concentrations of IQs for the times indicated in the figures and figure legends. Cells were collected into RIPA buffer supplemented with protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (G-Biosciences, St. Louis, MO). Cells were then sonicated and centrifuged (13,000 rpm × 15 min), and the protein concentration of the supernatant was determined using the method of Lowry. Cellular proteins (50 μg) were then separated by 12% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride membrane. The membrane was then probed with primary antibodies against phospho-p38 (Thr180/Tyr182), phospho-JNK (Thr183/Try185), phospho-ASK1 (Ser83), and β-actin followed by horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse/rabbit immunoglobulin G secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Western blotting signals were detected with enhanced chemiluminescence Western blotting detection reagents (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire, UK). All Western blots shown are representative of three independent experiments.

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical analysis was performed using one-way analysis of variance followed by appropriate post hoc tests: Dunnett test for comparison of multiple observations to a single control; Student's t test for pairwise comparisons. Data are represented as mean ± S.D. of at least three replicate experiments.

Results

IQs Used in This Study.

A series of IQs was screened in our previous study as potential antitumor agents against human pancreatic cancer (Yan et al., 2009). In the current study, two lead compounds (Fig. 1A), IQ compounds 1 and 2, were selected for mechanistic studies of the IQs in human pancreatic cancer cells. A proposed mechanism of action of the IQs was shown in Fig. 1B, including IQ reduction, ejection of the leaving group, and the generation of an electrophilic alkylating species (Fig. 1B). Human TR1, which has a C-terminal active-site selenocysteine residue, was considered to be a potential target of the IQs.

Growth Inhibitory Activity of the IQs in Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells.

The effect of IQs 1 and 2 on the growth of human pancreatic cancer cells was assessed using the MTT assay in the MIA PaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cell line. Both IQs exhibited marked growth inhibitory activity with IC50 values in the low nanomolar range. The IC50 values of IQ 1 in MIA PaCa-2 cells were 96 and 74 nM after 4- and 72-h treatment, respectively; the IC50 values of IQ 2 were 35 and 18 nM after 4- and 72-h treatment, respectively. The growth-inhibitory activity of both IQs was also confirmed in two other human pancreatic cancer cell lines PANC-1 and BxPC-3 (data not shown).

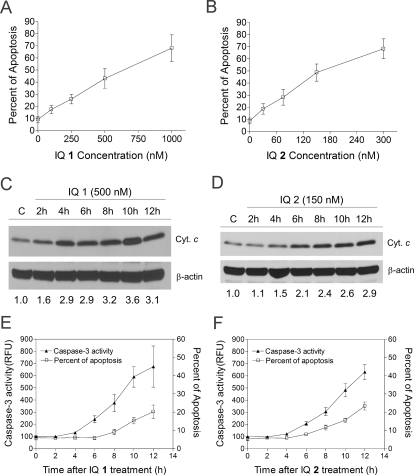

Induction of Apoptosis by the IQs in Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells.

We have previously reported the induction of caspase-dependent apoptosis by IQ 1 in MIA PaCa-2 cells. In the current study, we confirmed that a dose-dependent increase in apoptosis was observed in MIA PaCa-2 cells after treatment with either IQ 1 or IQ 2 (18 h), at concentration ranges approximately equivalent to the MTT IC50 values (Fig. 2, A and B). A detailed time course of apoptotic events was also examined in IQ-treated MIA PaCa-2 cells; mitochondrial cytochrome c release into cytosol was detectable 2 to 4 h after drug treatment (Fig. 2, C and D), followed by caspase-3 activation at 4 to 6 h (Fig. 2, E and F), and apoptosis as demonstrated by Annexin-V staining 8 h after treatment (Fig. 2, E and F). Taken together, these data demonstrated that the IQs induced cytotoxicity through caspase activation and apoptosis induction. These data also suggested that activation of the mitochondrial pathway was a key event involved in apoptotic signaling.

Fig. 2.

Induction of apoptosis by IQs in MIA PaCa-2 human pancreatic cancer cells. A and B, IQ treatment induced dose-dependent apoptosis in MIA PaCa-2 cells. Cells were treated with IQ 1 (A) or 2 (B) at various concentrations. Apoptosis was measured 18 h after drug treatment using Annexin-PI staining in combination with flow cytometry. C and D, time course of mitochondrial cytochrome c release induced by IQ treatment in MIA PaCa-2 cells. Cells were treated with 500 nM IQ 1 (C) or 150 nM IQ 2 (D) and collected at indicated time points, and cytochrome c (Cyt. c) levels in the cytosolic fraction were analyzed using immunoblotting analysis. Cytochrome c band intensity was also quantified relative to β-actin and indicated as fold of control underneath the immunoblot (C and D). Immunoblot shown was representative of three independent experiments. E and F, time course of caspase-3 activation and apoptosis induction by IQ treatment in MIA PaCa-2 cells. Cells were treated with 500 nM IQ 1 (E) or 150 nM IQ 2 (F), and at indicated time points, cells were collected; caspase-3 activity (▴) was determined using fluorescent substrates, and apoptosis (□) was measured using annexin-PI staining and flow cytometry. Data represent mean ± S.D. of three independent determinations.

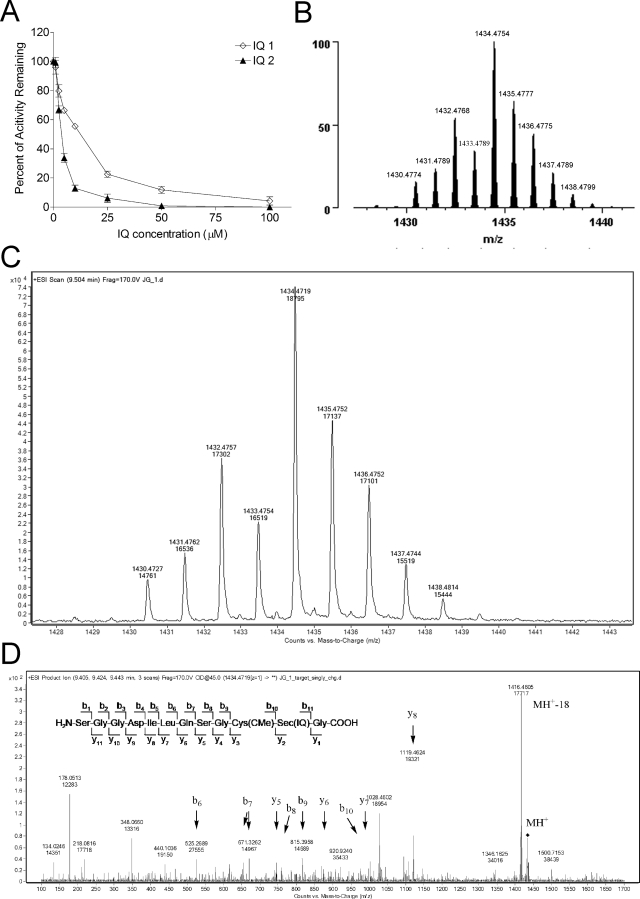

Inhibition of TR1 by IQs in Cell-Free Systems.

Because IQs require reduction to be activated, the ability of IQs to inhibit recombinant rat TR1 was tested in cell-free systems using NQO2 as the reductive activation step (IQs tested did not affect NQO2 activity under these conditions; NQO2/NRH alone did not affect TR1 activity under these conditions). When NADPH-reduced TR1 was incubated with NQO2/NRH-reduced IQ 1 or 2, a dose-dependent inhibition of TR1 activity was observed (Fig. 3A). Inhibition was NADPH-dependent (data not shown), suggesting that the selenocysteine active site of the enzyme was involved in the inhibition by IQs; inhibition was also NQO2/NRH-dependent (data not shown), indicating that the toxic species responsible for TR1 inhibition was generated after reduction and ejection of the leaving group. The inhibition of TR1 appeared to be irreversible, because desalting of the inhibited TR1 enzyme using Millipore Molecular Cutoff devices did not result in recovery of enzyme activity (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

Characterization of TR1 inhibition by IQs in cell-free systems. A, dose-dependent inhibition of TR1 activity in cell-free system by IQs. Recombinant rat TR1 (0.5 μM) was preincubated for 5 min with 250 μM NADPH in the presence of NQO2/NRH, then IQ 1 or 2 was added and incubated for 5 min (maximum inhibition was achieved at 5 min). An aliquot of 20 μl sample (from 150 μl total reaction) was taken out for measurement of TR1 activity using DTNB as substrate. B and D, mass spectrometric analysis of TR1-IQ 1 adducts. Theoretical (B) and experimentally determined (C) spectra from LC/MS analysis of TR1 C-terminal tryptic peptide containing one IQ 1-derived iminium and one carbamidomethyl adduct. TR1 was first reduced with NADPH and then treated with IQ 1 in the presence of NQO2/NRH. The proteins were denatured, and unreacted thiols and selenols were derivatized with iodoacetamide. Then, they were digested with trypsin and subjected to LC-MS/MS analysis. Note the distinctive isotope pattern characteristic of selenium-containing ions. D, MS/MS analysis of the C-terminal tryptic fragment of IQ 1-modified TR1. The sequence of the C-terminal peptide is shown (inset) along with b- and y-series ions (arrows). The IQ adduction was determined to be on the Sec residue (IQ), whereas the Cys residue was found to bear a carbamidomethyl modification.

Identification of the TR1 C-terminal Selenocysteine Active Site as the Target for IQ Modification.

LC-MS/MS methods were used to identify the site of modification by the IQs. Purified TR1 was incubated with IQ 1, digested, and subjected to MS/MS analysis. As shown in Fig. 3C, a peptide signal exhibiting an isotope distribution pattern characteristic of selenium was detected with a molecular mass of 1434.47 Da, which corresponded to the molecular mass of the C-terminal tryptic fragment of TR1 plus one IQ 1-derived iminium intermediate and one iodoacetamide modification. The isotope distribution observed was also in agreement with the theoretical distribution pattern generated using the ProteinProspector program (Fig. 3B). To identify the exact site of adduction by the IQ, this peptide was subject to MS/MS fragmentation, which generated a spectrum (Fig. 3D) demonstrating that the adduction site was the selenocysteine but not the cysteine residue. These results confirmed that TR1 was alkylated by an IQ-derived iminium species leading to inhibition of the enzyme.

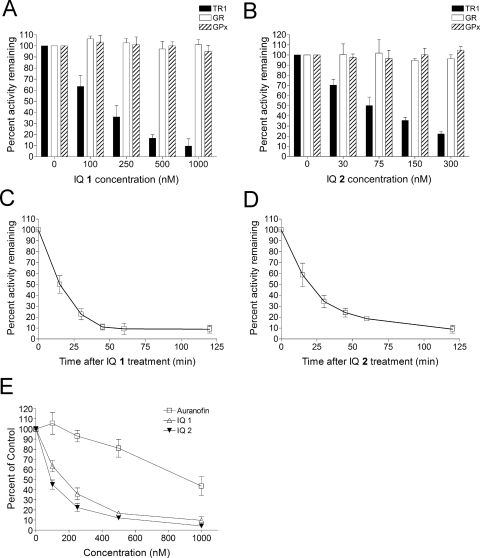

Selective Inhibition of TR1 by IQs in Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells.

The ability of IQs 1 and 2 to inhibit cellular TR1 activity was tested in MIA PaCa-2 cells. TR1 activity was measured using the endpoint insulin reduction assay as described under Materials and Methods. A dose-dependent inhibition of TR1 activity in MIA PaCa-2 cells was observed for both compounds after 1-h treatment (Fig. 4, A and B). The IC50 value for TR1 inhibition was 146 nM for IQ 1 and 82 nM for IQ 2, respectively. TR1 inhibition was also time-dependent, and maximum inhibition was observed as early as 1 h after treatment (Fig. 4, C and D). The most active inhibitor of TR1 characterized to date is auranofin (Urig and Becker 2006), and Fig. 4E demonstrated that the IQs are markedly more potent than auranofin as inhibitors of TR1 in cells (up to 11-fold greater potency).

Fig. 4.

Inhibition of TR1 activity by IQs in MIA PaCa-2 cells. A and B, effect of IQ treatment on the activity of TR1, GR, and Gpx in MIA PaCa-2 cells. Cells were treated with IQ 1 (A) or 2 (B) for 1 h. TR1 activity in cells was then measured using the endpoint insulin reduction assay and expressed as a percentage of DMSO-treated control. GR and Gpx activity in cells were also measured and expressed as percentage of DMSO-treated control. C and D, time-dependent inhibition of TR1 by IQs in MIA PaCa-2 cells. Cells were treated with IQ 1 (1000 nM) or IQ 2 (D; 300 nM) for indicated times. TR1 activity in cells was then measured using the endpoint insulin reduction assay. E, a comparison of TR1 inhibitory ability in MIA PaCa-2 cells between IQs and auranofin. Data represent mean ± S.D. of three independent determinations.

To test the selectivity of TR1 inhibition by the IQs in cells, the activity of two closely related enzymes, GR and GPx, were also measured in IQ-treated Mia PaCa-2 cells. GR has a protein structure similar to that of TR1 but lacks the C-terminal selenocysteine residue (Sandalova et al., 2001). GPx is another selenium-containing protein, but the selenocysteine residue is not as exposed as that in TR1 (Ren et al., 1997). The activity of neither enzyme was affected by IQ treatment at concentrations that resulted in potent inhibition of TR1 (Fig. 4, A and B). The inability of the IQs to inhibit GR or GPx activity in cells suggested that the C-terminal selenocysteine of TR1, which is the penultimate amino acid in a 10-residue exposed chain (Cheng et al., 2009), was the target of the IQs. These data also demonstrated that the IQ compounds are relatively specific inhibitors of TR1 in human pancreatic cells.

Effect of IQ Treatment on Radical-Mediated Oxidative Stress, GSH/GSSG Ratio, and Nonprotein Thiols in Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells.

To test whether IQ treatment resulted in any general oxidative stress in cells, we measured the cellular levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) as indicated by use of the fluorescent probes dihydroethidium and 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein-diacetate, and no increase in fluorescence could be detected (data not shown). As an indirect indication of oxidative stress, total cellular nonprotein thiol levels and GSH/GSSG ratio (Supplemental Fig. 1) were also determined, and no change in either index was observed after drug treatment. Furthermore, the ability of the IQs to induce redox cycling in cells was assessed by measuring oxygen uptake (Clark electrode). IQ treatment induced no increase in the rate of oxygen uptake in cells (data not shown). These data suggested that the IQs did not induce significant redox cycling and oxidative stress in human pancreatic cancer cells.

Effect of IQ Treatment on the Redox State of Thioredoxin-1 in Human Pancreatic Cancer Cells.

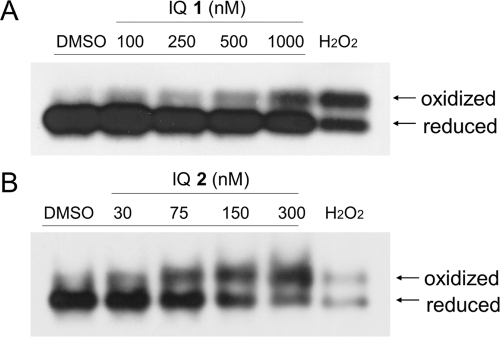

The thioredoxin-1 redox state in MIA PaCa-2 cells was assessed after 1-h IQ treatment. As described under Materials and Methods, reduced and oxidized forms of thioredoxin-1 were separated by native protein gel electrophoresis after iodoacetic acid treatment of the cellular protein. As shown in Fig. 5, treatment with either IQ 1 or IQ 2 induced a dose-dependent increase in oxidized thioredoxin-1 accompanied by a decrease in the reduced form at concentrations as low as 100 nM (1) and 75 nM (2).

Fig. 5.

Effect of IQ treatment on thioredoxin redox state in pancreatic cancer cells. Thioredoxin redox state was determined in MIA PaCa-2 cells 1 h after IQ 1 (A) or 2 (B) treatment as described under Materials and Methods. H2O2 treatment (1 mM for 10 min) was included as a positive control. Immunoblot shown represents three independent experiments.

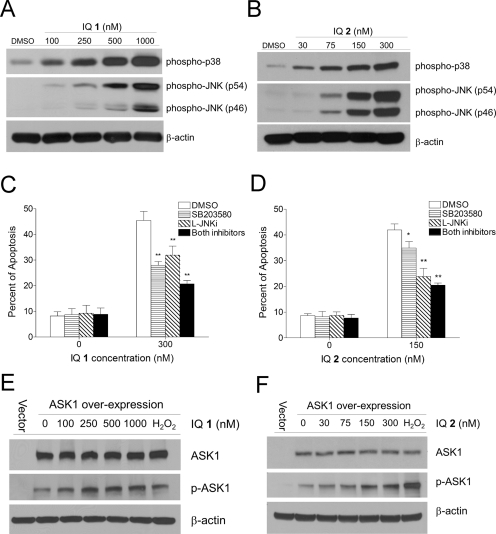

Effect of IQ Treatment on the MAPK Signaling Pathway in Pancreatic Cancer Cells.

IQ-induced apoptotic signaling was examined in MIA PaCa-2 cells after 1-h drug treatment. Treatment with IQ 1 or 2 resulted in the activation of both p38 and JNK MAPKs as indicated by increased phosphorylation of p38 and JNK in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 6, A and B). Pretreatment with the p38 inhibitor SB230580 (5 μM) or the JNK inhibitory peptide l-JNKi (5 μM) significantly decreased IQ-induced apoptosis in MIA PaCa-2 cells (Fig. 6, C and D). This suggested that the IQs induced apoptosis in pancreatic cancer cells via mechanisms involving activation of both p38 and JNK.

Fig. 6.

Effects of IQ treatment on the activation of the MAPK apoptotic signaling pathway. A and B, IQ treatment induced dose-dependent activation of p38 and JNK MAPKs in MIA PaCa-2 cells. Cells were treated with various concentrations of IQ 1 (A) or 2 (B) for 1 h; p38 and JNK phosphorylation were then detected using immunoblot analysis. C and D, IQ-induced apoptosis was inhibited by pretreatment with p38 and JNK inhibitors. MIA PaCa-2 cells were pretreated with the p38 inhibitor SB203580 (5 μM), the JNK inhibitory peptide l-JNKi (5 μM), or both for 1 h before treatment with IQ 1 (C) or 2 (D) for 18 h. Apoptosis was measured using Annexin-PI staining and flow cytometry. E and F, IQ treatment induced ASK1 activation in MIA PaCa-2 cells. Cells were transiently transfected with the plasmid pCMV-SPORT6-ASK1 or the vector control by electroporation and incubated in complete medium for 16 h. Cells were then treated with IQ 1 (E) or 2 (F) for 30 min. Levels of total ASK1 (top) and phosphorylated ASK1 (bottom) were analyzed using immunoblotting. H2O2 treatment (1 mM for 10 min) was included as a positive control. Immunoblots shown represent three independent experiments.

ASK1 represents a possible link between upstream TR1 inhibition/oxidized thioredoxin production and downstream p38/JNK activation. We therefore tested whether ASK1 was involved in IQ-induced apoptotic signaling. Because the endogenous levels of ASK1 in MIA PaCa-2 cells were difficult to detect using commercially available antibodies, we transiently overexpressed ASK1 and measured its phosphorylation after IQ treatment. As shown in Fig. 6, E and F, ASK1 expression was detectable 16 h after transfection, at which time point transfected cells were treated with IQs for 1 h. A dose-dependent activation of ASK1, as indicated by the increase in phosphorylation at residue Ser83, was observed after treatment with IQ 1 or 2. H2O2 treatment (1 mM for 10 min) was included as a positive control.

Discussion

TR1 and thioredoxin-1 have both emerged as important targets in cancer chemotherapy, because both proteins have been shown to be overexpressed in a variety of human cancer types and associated with increased tumor growth, drug resistance, and poor patient prognosis (Urig and Becker 2006). Several antitumor agents have been shown to be inhibitors of the thioredoxin system, including 1,3-bis-(2-chloro-ethyl)-1-nitrosourea, 1-chloro-2,4-dinitrobenzene, cisplatin and analogs, curcumin, cyclophosphamide, and arsenic trioxide (Gromer et al., 1997; Nordberg et al., 1998; Fang et al., 2005; Witte et al., 2005; Lu et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2007). Specific inhibitors of the thioredoxin system have also been developed, including the thioredoxin-1 inhibitors 2-[(1-methylpropyl)dithio]-1H-imidazole (PX-12) and 2,5-bis[(dimethylamino)methyl]cyclopentanone (NSC131233; Wipf et al., 2004) and the TR1 inhibitors 2-(5-hydroxy-4-oxo-4H-spiro[naphthalene-1,2′-naphtho[1,8-de][1,3]dioxine]-6′-yloxy)-2-oxoethanminium trifluoroacetate (PX916) (Powis et al., 2006) and AW464 (Chew et al., 2008).

IQs represent a novel class of small-molecule chemotherapeutic agents that have been shown to exhibit potent antitumor activity against several types of human cancer (Yan et al., 2009). The growth inhibitory and cytotoxic effects of the IQs against human pancreatic cancer cell lines both in vitro and in vivo have been examined in detail in our previous study (Yan et al., 2009). A potential mechanism of action of the IQs in human pancreatic cancer cells was also proposed, involving reduction of the IQ, loss of a leaving group RO−, and generation of an electrophilic alkylating species (Fig. 1) that is attacked by a nucleophilic residue in the protein. TR1 represents a potential target of quinone electrophiles because it contains a C-terminal active site selenocysteine (Sec) residue that, because of its low pKa, is very susceptible to electrophilic attack (Powis et al., 2006; Chew et al., 2008). This penultimate C-terminal Sec residue has been shown to be essential for the catalytic activity of TR1 (Cheng et al., 2009). Previous studies in our lab suggested that TR1 might be a molecular target of the IQs. In this study, we confirmed this hypothesis by characterizing TR1 inhibition by the IQs in both cell-free and cellular systems. The fact that TR1 inhibition by the IQs was NADPH-dependent and irreversible suggests covalent modification of the active site of the enzyme. LC-MS/MS methods were employed to identify the exact site of TR1 adduction by the IQs, and the results provided unequivocal evidence that the C-terminal selenocysteine was the primary site of alkylation by the reactive IQ-derived iminium electrophile.

TR1 inhibition by IQs seemed to be relatively specific. The structurally similar protein glutathione reductase and the related selenoprotein glutathione peroxidase were not inhibited by the IQs in cells, suggesting that the IQ-derived reactive species were selectively active toward the exposed C-terminal selenocysteine of TR1. Moreover, in LC-MS/MS experiments, IQ adduction could be detected only on the selenocysteine residue, not on the neighboring cysteine residue, further confirming the selective reactivity of the IQ-derived electrophile toward the low-pKa selenocysteine residue. In fact, the reactivity of the selenocysteine to electrophiles relative to cysteine has been estimated to be approximately 1000 times greater (Arnér and Holmgren, 2006). These data demonstrated the IQs' selectivity for selenocysteine adduction and TR1 inhibition in human pancreatic cancer cells.

Quinone compounds are well known for their ability to induce redox cycling and oxidative stress, which contributes to the antitumor activity and toxicity of many quinone-based chemotherapeutic agents (Powis, 1987). We therefore examined whether this also contributed to the cytotoxicity of the IQs. However, we could detect no ROS production using two different fluorescent probes in pancreatic cancer cells treated with IQs at doses that induced growth-inhibitory effects, suggesting that the IQs did not induce ROS-mediated oxidative stress. This was confirmed by three independent criteria. First, IQ treatment induced no change in total nonprotein thiols or GSH/GSSG ratio in drug-treated cells. Second, our previous work demonstrated that IQs did not induce detectable DNA single-strand breaks relative to known redox cycling quinones such as β-lapachone and streptonigrin. Finally, increased oxygen uptake measured polarographically could not be detected after addition of IQs to pancreatic cancer cells. These data demonstrated that the IQs did not induce generalized oxidative stress in cells; however, inhibition of TR1 could result in a shift in the oxidative balance of reduced/oxidized thioredoxin-1 and induction of radical-free oxidative stress (Jones 2008).

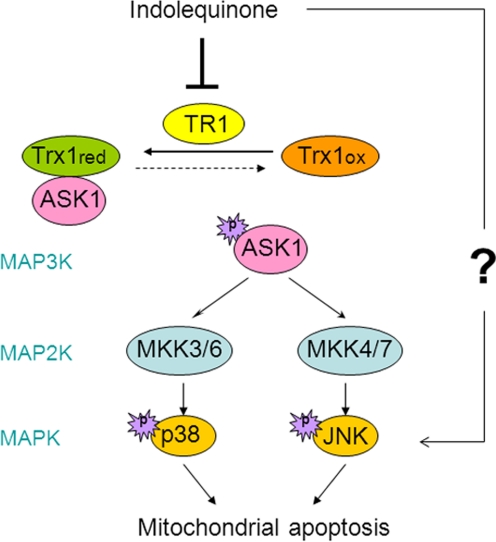

To test this hypothesis, we first examined the effects of TR1 inhibition on the redox state of thioredoxin-1. A shift in thioredoxin-1 redox state from reduced form to the oxidized form was clearly evident after treatment with the IQs (Fig. 5). An important signaling molecule regulated by thioredoxin-1 is ASK1, a member of the mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase family and an upstream activator in the MAPK signaling pathway. Under normal conditions, ASK1 is bound to and inhibited by reduced thioredoxin; upon thioredoxin oxidation, ASK1 can be activated and initiate apoptosis signaling through the p38/JNK MAPKs (Ichijo et al., 1997; Saitoh et al., 1998). Our results (Fig. 6) showed that both p38 and JNK were activated after IQ treatment. Indeed, IQ-induced apoptosis was significantly reduced by the use of p38 and JNK inhibitors, suggesting that IQ-induced apoptosis was dependent on the MAPK pathway. Because endogenous levels of ASK1 in Mia PaCa-2 pancreatic cancer cells were difficult to detect using commercially available antibodies, we transiently overexpressed ASK1, and addition of IQs resulted in activation of ASK1 as indicated by phosphorylation at Ser83 (Fig. 6). Phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of Ser83 have both been correlated with ASK1 activation (Kim et al., 2001; Gu et al., 2009; Fortin et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2010). However, recent work have emphasized the role of Ser83 phosphorylation of ASK1 in induction of apoptosis (Fortin et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2010), and this is in agreement with our observations of IQ-induced ASK1 phosphorylation at Ser83 and subsequent apoptosis. Because p38/JNK could also be activated by other upstream kinases in addition to ASK1, further experiments are needed to determine whether ASK1 plays a critical role in apoptotic signaling. However, based on the documented role of thioredoxin in the regulation of apoptosis signaling (Ichijo et al., 1997; Saitoh et al., 1998), it is likely that ASK1 is the mechanistic link between the oxidation of thioredoxin and the activation of p38 and JNK. Activated p38 and JNK has been shown to signal to mitochondria and induce apoptosis through the intrinsic pathway (Zhuang et al., 2000; Deng et al., 2001; Ortiz et al., 2001). To characterize the cell death program, we have examined some characteristic events of apoptosis, including cytochrome c release, caspase-3 activation, and phosphoserine externalization. Our results (Fig. 2) suggest that IQ treatment induced cell death via a mitochondria-mediated apoptotic death pathway. The proposed IQ-induced apoptotic signaling cascade is shown in Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

A proposed apoptotic signaling cascade induced by IQ treatment in human pancreatic cancer cells. TR1 inhibition by the IQs results in a shift of thioredoxin redox state from the reduced (Trx1red) to the oxidized (Trx1ox) form. Oxidized thioredoxin dissociates with ASK1 and results in its activation via phosphorylation. Activated ASK1 as an mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinase (MAP3K) would activate mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases (MAP2Ks), including MKK3/6 and MKK4/7, which will in turn activate p38 and JNK MAPKs and induce downstream mitochondrial apoptosis.

Our findings, together with other reports of TR1 inhibitors inducing apoptosis signaling and cell death, corroborate a mechanism of growth inhibition involving radical-free oxidative stress (Jones 2008). The mechanism of action of many anticancer drugs involves free radical-mediated oxidative stress and macromolecular damage. However, as exemplified by the thioredoxin system, drug-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis signaling could also occur via the disruption of thiol redox circuits in proteins. The redox homeostasis of the protein thiol systems is controlled by thioredoxins, peroxiredoxins, and glutathione (Biswas et al., 2006). Because tumor cells usually rely more heavily on these systems to sustain growth and reduce oxidative stress, anticancer agents specifically targeting these molecules represent a promising approach to inhibit cancer cell growth and induce apoptotic cell death.

In conclusion, we have examined the mechanism of action of novel antitumor IQs in human pancreatic cancer cells. We have demonstrated that IQs were potent and selective inhibitors of TR1 and identified the C-terminal selenocysteine of TR1 as the target of alkylation by the IQs. Inhibition of TR1 in human pancreatic cancer cells resulted in a shift in thioredoxin redox state, activation of ASK1, p38, and JNK, and downstream induction of apoptosis. These studies represent the first comprehensive analysis of redox and signaling events responsible for the mechanism of action of TR1 inhibitors in human pancreatic cancer cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Joe Gomez from the University of Colorado School of Pharmacy Mass Spectrometry Core Facility and Dr. Rick Reisdorph from the National Jewish Health Mass Spectrometry Core Facility for help with the LC-MS/MS experiments.

The online version of this article (available at http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org) contains supplemental material.

The online version of this article (available at http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org) contains supplemental material.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute [Grant R01-CA114441].

D.S., C.J.M., and D.R. are scientific cofounders and stockholders in QGenta Inc., which holds an option to license molecules described in this article.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

- IQ

- indolequinone

- 1

- 2-hydroxymethyl-5-methoxy-1-methyl-3-[(4-nitrophenoxy)methyl]indole-4,7-dione

- 2

- 5-methoxy-1-methyl-3-[(2,4,6-trifluorophenoxy)methyl]indole-4,7-dione

- TR1

- thioredoxin reductase 1

- ASK1

- apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1

- JNK

- c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase

- MAPK

- mitogen-activated protein kinase

- NQO2

- NRH:quinone oxidoreductase 2

- NRH

- dihydronicotinamide riboside

- SB203580

- 4-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(4-methylsulfinylphenyl)-5-(4-pyridyl)1H-imidazole

- l-JNKi

- l-form of the JNK-inhibitory peptide

- CMV

- cytomegalovirus

- MTT

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- PI

- propidium iodide

- RIPA

- radioimmunoprecipitation assay

- DTNB

- 5,5′-dithio-bis(2-nitrobenzoid acid

- LC-MS/MS

- liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

- GR

- glutathione reductase

- GPx

- glutathione peroxidase

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- PX-12

- 2-[(1-methylpropyl)dithio]-1H-imidazole

- NSC131233

- 2,5-bis[(dimethylamino)methyl]cyclopentanone

- AW464

- 4-(benzothiazol-2-yl)-4-hydroxy-2,5-cyclohexadien-1-one

- PX916

- 2-(5-hydroxy-4-oxo-4H-spiro[naphthalene-1,2′-naphtho[1,8-de][1,3]dioxine]-6′-yloxy)-2-oxoethanminium trifluoroacetate

- Sec

- selenocysteine.

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Yan, Siegel, Moody, and Ross.

Conducted experiments: Yan and Siegel.

Contributed new reagents or analytic tools: Newsome and Chilloux.

Performed data analysis: Yan and Siegel.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Yan, Siegel, Moody, and Ross.

References

- Abate C, Patel L, Rauscher FJ, 3rd, Curran T. (1990) Redox regulation of fos and jun DNA-binding activity in vitro. Science 249:1157–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnér ES, Holmgren A. (2006) The thioredoxin system in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol 16:420–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berggren MI, Husbeck B, Samulitis B, Baker AF, Gallegos A, Powis G. (2001) Thioredoxin peroxidase-1 (peroxiredoxin-1) is increased in thioredoxin-1 transfected cells and results in enhanced protection against apoptosis caused by hydrogen peroxide but not by other agents including dexamethasone, etoposide, and doxorubicin. Arch Biochem Biophys 392:103–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswas S, Chida AS, Rahman I. (2006) Redox modifications of protein-thiols: emerging roles in cell signaling. Biochem Pharmacol 71:551–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy PB, Edes K, Nelson CC, Parsawar K, Fitzpatrick FA, Moos PJ. (2006) Thioredoxin reductase is required for the inactivation of tumor suppressor p53 and for apoptosis induced by endogenous electrophiles. Carcinogenesis 27:2538–2549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Q, Sandalova T, Lindqvist Y, Arnér ES. (2009) Crystal structure and catalysis of the selenoprotein thioredoxin reductase 1. J Biol Chem 284:3998–4008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chew EH, Lu J, Bradshaw TD, Holmgren A. (2008) Thioredoxin reductase inhibition by antitumor quinols: a quinol pharmacophore effect correlating to antiproliferative activity. FASEB J 22:2072–2083 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colucci MA, Reigan P, Siegel D, Chilloux A, Ross D, Moody CJ. (2007) Synthesis and evaluation of 3-aryloxymethyl-1,2-dimethylindole-4,7-diones as mechanism-based inhibitors of NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1) activity. J Med Chem 50:5780–5789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cromlish JA, Roeder RG. (1989) Human transcription factor IIIC (TFIIIC). Purification, polypeptide structure, and the involvement of thiol groups in specific DNA binding. J Biol Chem 264:18100–18109 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng X, Xiao L, Lang W, Gao F, Ruvolo P, May WS., Jr (2001) Novel role for JNK as a stress-activated Bcl2 kinase. J Biol Chem 276:23681–23688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang J, Lu J, Holmgren A. (2005) Thioredoxin reductase is irreversibly modified by curcumin: a novel molecular mechanism for its anticancer activity. J Biol Chem 280:25284–25290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortin J, Patenaude A, Deschesnes RG, Côté MF, Petitclerc E, C-Gaudreault R. (2010) ASK1–P38 pathway is important for anoikis induced by microtubule-targeting aryl chloroethylureas. J Pharm Pharm Sci 13:175–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlos F, Jarman M, Davies LC, Boland MP, Knox RJ. (1992) Identification of novel reduced pyridinium derivatives as synthetic co-factors for the enzyme DT diaphorase (NAD(P)H dehydrogenase (quinone), EC 1.6.99.2). Biochem Pharmacol 44:25–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grippo JF, Tienrungroj W, Dahmer MK, Housley PR, Pratt WB. (1983) Evidence that the endogenous heat-stable glucocorticoid receptor-activating factor is thioredoxin. J Biol Chem 258:13658–13664 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gromer S, Arscott LD, Williams CH, Jr, Schirmer RH, Becker K. (1998) Human placenta thioredoxin reductase. Isolation of the selenoenzyme, steady state kinetics, and inhibition by therapeutic gold compounds. J Biol Chem 273:20096–20101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gromer S, Schirmer RH, Becker K. (1997) The 58 kDa mouse selenoprotein is a BCNU-sensitive thioredoxin reductase. FEBS Lett 412:318–320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu JJ, Wang Z, Reeves R, Magnuson NS. (2009) PIM1 phosphorylates and negatively regulates ASK1-mediated apoptosis. Oncogene 28:4261–4271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichijo H, Nishida E, Irie K, ten Dijke P, Saitoh M, Moriguchi T, Takagi M, Matsumoto K, Miyazono K, Gotoh Y. (1997) Induction of apoptosis by ASK1, a mammalian MAPKKK that activates SAPK/JNK and p38 signaling pathways. Science 275:90–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DP. (2008) Radical-free biology of oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 295:C849–C868 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim AH, Khursigara G, Sun X, Franke TF, Chao MV. (2001) Akt phosphorylates and negatively regulates apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1. Mol Cell Biol 21:893–901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurent TC, Moore EC, Reichard P. (1964) Enzymatic synthesis of deoxyribonucleotides. IV. Isolation and characterization of thioredoxin, the hydrogen donor from Escherichia coli b. J Biol Chem 239:3436–3444 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang LP, Patel M. (2006) Seizure-induced changes in mitochondrial redox status. Free Radic Biol Med 40:316–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. (1951) Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193:265–275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J, Chew EH, Holmgren A. (2007) Targeting thioredoxin reductase is a basis for cancer therapy by arsenic trioxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:12288–12293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews JR, Wakasugi N, Virelizier JL, Yodoi J, Hay RT. (1992) Thioredoxin regulates the DNA binding activity of NF-kappa B by reduction of a disulphide bond involving cysteine 62. Nucleic Acids Res 20:3821–3830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. (1983) Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods 65:55–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordberg J, Zhong L, Holmgren A, Arnér ES. (1998) Mammalian thioredoxin reductase is irreversibly inhibited by dinitrohalobenzenes by alkylation of both the redox active selenocysteine and its neighboring cysteine residue. J Biol Chem 273:10835–10842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz MA, Lopez-Hernandez FJ, Bayon Y, Pfahl M, Piedrafita FJ. (2001) Retinoid-related molecules induce cytochrome c release and apoptosis through activation of c-Jun NH(2)-terminal kinase/p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases. Cancer Res 61:8504–8512 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powis G. (1987) Metabolism and reactions of quinoid anticancer agents. Pharmacol Ther 35:57–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powis G, Wipf P, Lynch SM, Birmingham A, Kirkpatrick DL. (2006) Molecular pharmacology and antitumor activity of palmarumycin-based inhibitors of thioredoxin reductase. Mol Cancer Ther 5:630–636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren B, Huang W, Akesson B, Ladenstein R. (1997) The crystal structure of seleno-glutathione peroxidase from human plasma at 2.9 A resolution. J Mol Biol 268:869–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitoh M, Nishitoh H, Fujii M, Takeda K, Tobiume K, Sawada Y, Kawabata M, Miyazono K, Ichijo H. (1998) Mammalian thioredoxin is a direct inhibitor of apoptosis signal-regulating kinase (ASK) 1. EMBO J 17:2596–2606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandalova T, Zhong L, Lindqvist Y, Holmgren A, Schneider G. (2001) Three-dimensional structure of a mammalian thioredoxin reductase: implications for mechanism and evolution of a selenocysteine-dependent enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98:9533–9538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sedlak J, Lindsay RH. (1968) Estimation of total, protein-bound, and nonprotein sulfhydryl groups in tissue with Ellman's reagent. Anal Biochem 25:192–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Y, Rigas B. (2008) The thioredoxin system mediates redox-induced cell death in human colon cancer cells: implications for the mechanism of action of anticancer agents. Cancer Res 68:8269–8277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno M, Masutani H, Arai RJ, Yamauchi A, Hirota K, Sakai T, Inamoto T, Yamaoka Y, Yodoi J, Nikaido T. (1999) Thioredoxin-dependent redox regulation of p53-mediated p21 activation. J Biol Chem 274:35809–35815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urig S, Becker K. (2006) On the potential of thioredoxin reductase inhibitors for cancer therapy. Semin Cancer Biol 16:452–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhang J, Xu T. (2007) Cyclophosphamide as a potent inhibitor of tumor thioredoxin reductase in vivo. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 218:88–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wipf P, Lynch SM, Birmingham A, Tamayo G, Jiménez A, Campos N, Powis G. (2004) Natural product based inhibitors of the thioredoxin-thioredoxin reductase system. Org Biomol Chem 2:1651–1658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte AB, Anestål K, Jerremalm E, Ehrsson H, Arnér ES. (2005) Inhibition of thioredoxin reductase but not of glutathione reductase by the major classes of alkylating and platinum-containing anticancer compounds. Free Radic Biol Med 39:696–703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan C, Kepa JK, Siegel D, Stratford IJ, Ross D. (2008) Dissecting the role of multiple reductases in bioactivation and cytotoxicity of the antitumor agent 2,5-diaziridinyl-3-(hydroxymethyl)-6-methyl-1,4-benzoquinone (RH1). Mol Pharmacol 74:1657–1665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan C, Shieh B, Reigan P, Zhang Z, Colucci MA, Chilloux A, Newsome JJ, Siegel D, Chan D, Moody CJ, et al. (2009) Potent activity of indolequinones against human pancreatic cancer: identification of thioredoxin reductase as a potential target. Mol Pharmacol 76:163–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang M, Yu M, Guan D, Gu J, Cao X, Wang W, Zheng S, Xu Y, Shen Z, Liu X. (2010) ASK1-JNK signaling cascade mediates Ad-ST13-induced apoptosis in colorectal HCT116 cells. J Cell Biochem 110:581–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuang S, Demirs JT, Kochevar IE. (2000) p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase mediates bid cleavage, mitochondrial dysfunction, and caspase-3 activation during apoptosis induced by singlet oxygen but not by hydrogen peroxide. J Biol Chem 275:25939–25948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.