Abstract

Purpose

Infections after pediatric cardiac surgery are a common complication, occurring in up to 30% of cases. The purpose of this study was to develop a bedside prediction rule to estimate the risk of a postoperative infection.

Methods

All consecutive pediatric cardiac surgery procedures between April 2006 and May 2009 were retrospectively analyzed. The primary outcome variable was any postoperative infection, as defined by the Center of Disease Control (2008). All variables known to the clinician at the bedside at 48 h post cardiac surgery were included in the primary analysis, and multivariable logistic regression was used to construct a prediction rule.

Results

A total of 412 procedures were included, of which 102 (25%) were followed by an infection. Most infections were surgical site infections (26% of all infections) and bloodstream infections (25%). Three variables proved to be most predictive of an infection: age less than 6 months, postoperative pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) stay longer than 48 h, and open sternum for longer than 48 h. Translation into prediction rule points yielded 1, 4, and 1 point for each variable, respectively. Patients with a score of 0 had 6.6% risk of an infection, whereas those with a maximal score of 6 had a risk of 57%. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.78 (95% confidence interval 0.72–0.83).

Conclusions

A simple bedside prediction rule designed for use at 48 h post cardiac surgery can discriminate between children at high and low risk for a subsequent infection.

Keywords: Pediatric intensive care unit, Infections, Cardiopulmonary bypass, Prediction rule

Introduction

Infections occurring after pediatric cardiac surgery are a frequent complication, with the reported incidence varying widely from 16 to 31% [1–4]. These infections are an important burden in the recovery after surgery, as they cause significant morbidity and lengthen pediatric intensive care unit (PICU) and total hospital stays [5].

The incidence of postoperative infections in children after cardiac surgery is higher than may be expected in the general PICU population (6–15%) [5–7]. This is presumed to be due to the hypoinflammatory phase of the systemic inflammatory response to cardiac surgery [8]. The most common types of infections are those occurring at the surgical site and bloodstream infections [1–4]. Perioperative risk factors have been identified previously, yielding younger age at surgery, higher surgical complexity, longer surgical and cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) duration, a longer PICU stay, and delayed sternal closure as important risk factors [1–4, 9–15]. Although these factors have helped to unravel the etiology of the infections, they do not necessarily reliably determine those patients which are most at risk. This creates the need for a prediction model, which aims to assist the clinician in the decision-making process. In the case of postoperative infections, the question is which preventive measures need to be taken, and in which patients?

In this study we used retrospective data from a recent pediatric cardiac surgery cohort from our center in order to identify which variables are predictive of postoperative infections. The aim was to develop a prediction rule to estimate the risk of an infection during hospital stay. The rule was designed for use at 48 h postoperatively, as the current protocol at our center is to stop prophylactic antibiotics at this time.

Methods

Patient population

In this retrospective study we included all consecutive cardiac surgery procedures performed with CPB in patients under the age of 18 years, between April 2006 and May 2009 at the Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital, University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands. The Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital is a university teaching hospital with a level III PICU, and is one of the four pediatric heart centers in the Netherlands. Patients were excluded if they died during or within 48 h after surgery, if charts were incomplete, or if long-term broad-spectrum antibiotics were already started preoperatively because of bloodstream infections. All data were collected by retrospective chart review using standardized case report forms. The local institutional medical ethics committee approved the study and waived the need for consent.

All patients received perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis, consisting of cefazolin 100 mg/kg a day, starting at the induction of anesthesia and continued until 48 h postoperatively or until sternal closure. A single dose of dexamethasone (1 mg/kg) was administered to all patients at the induction of anesthesia. Preoperative disinfection of the skin of the thorax was performed with chlorhexidine solution 0.5% in 70% alcohol. After correction of the heart defect and directly before skin closure, disinfection of the skin and wound margins was repeated with chlorhexidine solution 0.5% in 70% alcohol. During the study period no specific Staphylococcus aureus eradication protocols were performed. All procedures were performed by the same surgical and anesthesiology team, the latter being responsible for care in the operating room as well as at the PICU.

Clinical variables

All known risk factors for postoperative infection from the literature were considered for use in the prediction model. However, only those readily available at the bedside were included in the analyses, and these were subsequently dichotomized (into a yes/no variable) using accepted thresholds from the literature. The eligible variables were age less than 6 months [2, 4, 9–11, 13, 14, 16]; preoperative admission at the PICU [3, 4, 9, 10, 13, 16]; surgical complexity [2–4, 10, 15]; previous cardiac surgery with the use of CPB [3, 4, 10, 14]; duration of surgery (timed from first incision until closure) greater than 3 h [9, 14]; CPB duration greater than 2 h [2, 3, 9, 14, 17, 18]; lowest nasopharyngeal temperature less than 25°C [16, 19, 20]; use of inotropes [2, 11, 13], endotracheal tube [5, 11, 13, 14], open sternum, and rethoracotomy [2, 3, 5, 12, 14, 16]; PICU stay longer than 48 h postoperatively [2, 3, 5, 6, 11, 13]; red blood cell transfusion (total of intra- and postoperative transfusion) greater than 50 mL/kg [3, 11, 14, 16, 17]; and peak glucose greater than 10 mmol/L in the first 24 h postoperatively [21, 22]. Surgical complexity was the only variable to be categorized into three groups, which was a simplified version of the RACHS-1 and Aristotle score [23, 24]. The ‘low complexity’ group (reference group) consisted of atrial and/or ventricular septal defect closures with or without ductus arteriosus ligation; the ‘high complexity’ group comprised all neonatal procedures resulting in a functionally univentricular heart. All other procedures were classified as ‘medium complexity’.

Outcome definition

The primary outcome of this study consisted of all infections presenting between 48 h after surgery until discharge from hospital. The occurrence of a postoperative infection was defined by the criteria of the Centre of Disease Control (CDC), revised by Horan et al. in 2008 [25]. If the origin or presence of an infection was not clear during chart review, the case was presented to an expert panel of two pediatric intensivists (NJGJ and AJvV) blinded to patient name and potentially predictive variables. When pneumonia was considered, chest X-rays were assessed by a pediatric radiologist (MG), similarly blinded. If there was consensus that a patient had an apparent infection, but insufficient data were available to classify the infection according to CDC criteria, it was classified as ‘infection not otherwise specified’. Bloodstream infections include both confirmed cases (‘laboratory confirmed’), and unconfirmed cases, where clinical symptoms suffice (‘clinical sepsis’), in accordance with the CDC criteria. Also, bloodstream infections were only classified as such when they were not related to an infection at another site. Surgical site infections (SSI) were categorized into incisional SSI or organ/space SSI. Incisional SSI consist of superficial and deep incisional SSI, where the superficial incisional SSI involve only skin and subcutaneous tissue, and the deep incisional SSI involve deep soft tissues (i.e., fascial and muscle layers). Because of the difficulty of retrospective assignment of tissue layers, these were combined into one category (incisional SSI). Organ/space SSI are defined as infections occurring in organs or spaces which are opened during the procedure, excluding skin, fascia, and muscle (e.g., mediastinitis, pleuritis). Microbiologic and virology data were collected from charts and the hospital database. Proven infections were defined as infections confirmed either by culture or polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and these infections were used as secondary outcome.

Statistical analysis

All variables were assessed for their association with infections using two-sided Pearson chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. For missing data, imputation techniques were used as complete case analysis would probably introduce bias [26]. A p value less than 0.15 in the univariable analysis allowed the variable to be used in the multivariable logistic regression model, providing it was not colinear with other variables (Pearson correlation greater than 0.7). Manual stepwise backward logistic regression was then performed. The choice for the final model was based on a balance between a high area under the curve (AUC) and the clinical utility. The discriminative potential of the final model was assessed using the AUC of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. A useless predictive model has an ROC-AUC of 0.5 and a perfectly predictive model results in an ROC-AUC of 1.0. The calibrative potential was assessed using the Hosmer–Lemeshow test. The final model was internally validated using bootstrap techniques, which provide a ‘shrinkage factor’ for the variable estimates. Alternative models that included more variables were compared with the final, fully reduced model. Furthermore, the robustness of the model was tested by using the secondary outcome (proven infections) and by repeating the analysis for complete cases only.

The final model was translated into a prediction rule, yielding ‘rule points’ for each variable. Rule points were calculated by dividing the multivariable regression coefficient by the lowest coefficient and rounding to the nearest integer. All patients were categorized according to their scores and the corresponding positive and negative predictive values were calculated. The calibration of the model was assessed by calculating the predicted risks of all cases belonging to one risk group.

Bootstrap techniques were performed with R for Windows version 2.10.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). SPSS version 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) was used for all other statistical analyses.

Results

A total of 426 procedures were performed in the inclusion period, of which 412 procedures performed in 364 patients remained for analysis (with incomplete files in three procedures, four patients who already had long-term antibiotics started preoperatively, and seven patients who died within 48 h postoperatively). Patient characteristics are outlined in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| All procedures (n = 412) | Procedures without infection (n = 310) | Procedures with infection (n = 102) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 226 (55) | 167 (54) | 59 (58) |

| Age (months) | 6.8 (1.7–44) | 11.3 (3.0–68) | 3.2 (0.5–9.2) |

| Weight (kg) | 6.7 (4.1–15) | 8.5 (4.6–17.6) | 4.6 (3.5–7.1) |

| Postoperative PICU stay (days) | 2 (1–6) | 2 (1–4) | 7 (3–14) |

| Postoperative hospital stay (days) | 7 (5–14) | 6 (5–9) | 20 (13–30) |

| Surgical complexitya | 8.0 (6.5–10.0) | 8.0 (6.0–9.0) | 9.0 (7.0–11.5) |

Values stated as n (% of [infection] group) or median (interquartile range)

aSurgical complexity was calculated using the Aristotle score [24]

Postoperative infections occurred after 102 procedures, yielding an incidence of 25% (95% confidence interval [CI] 21–29). The total number of infections was 127, with 81 procedures being followed by a single infection, 17 procedures by two, and four procedures by three infections. The median start of infection was 7 days after surgery (interquartile range [IQR] 4–12).

Of all infections, 72 (57%) were proven by culture or PCR, with seven cases yielding two different microorganisms (Table 2). The two most common types of infection were SSI, responsible for 33 (26%) of all infections, and bloodstream infections, responsible for 32 (25%) of all infections. SSI were mostly incisional SSI (n = 24, consisting of both superficial and deep incisional SSI), and nine organ/space SSI (mediastinitis in five cases, and pleuritis in four cases) (Table 2). Most SSI were caused by S. aureus (71% of all proven infections), whereas in bloodstream infections, coagulase-negative Staphylococcus was most abundant (44%). In urinary tract infections, Escherichia coli was isolated most often (33%).

Table 2.

Infection types and isolated microorganisms

| Infection type (CDC criteria) | n (% of all infections) | Gram-positive bacteria | Gram-negative bacteria | Viruses | Fungi/yeasts | Microorganism unknown |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical site infection | 33 (25.9) | |||||

| Incisional | 24 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 19 |

| Organ/spacea | 9 | 6 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bloodstream infection | 32 (25.1) | |||||

| Laboratory confirmed | 16 | 12 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Clinical sepsis | 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 16 |

| Urinary tract infection | 15 (11.8) | |||||

| Symptomatic | 12 | 0 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Asymptomatic | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gastroenteritis | 18 (14.2) | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 8 |

| Skin infection | 6 (4.7) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Pneumoniab | 3 (2.4) | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Respiratory tract infection | 9 (7.1) | |||||

| Upper | 7 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| Lower | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Other infectionsc | 11 (8.7) | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| Total (% of all infections) | 127 | 26 (20.5) | 29 (22.8) | 15 (11.8) | 3 (2.4) | 55 (43.3) |

aMediastinitis (n = 5) and pleuritis (n = 4)

bIn one pneumonia case, both Moraxella catarrhalis and Rhinovirus were isolated

cOther infections: conjunctivitis (n = 3), oral cavity infection (n = 3), decubitus (n = 1), endocarditis (n = 1), epididymitis (n = 1), infection not otherwise specified (n = 2)

Differences between the group with versus without infections regarding various perioperative risk factors for infections are shown in Table 3. After screening for colinearity, where surgery and CPB duration were colinear, as well as inotrope and endotracheal tube duration and PICU stay, nine variables were finally included in the multivariable analysis. Following backward logistic regression, three variables remained in the final prediction model, which were age less than 6 months, PICU stay longer than 48 h, and open sternum for longer than 48 h. This model had an AUC-ROC of 0.78 (95% CI 0.73–0.83) with an acceptable Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness of fit of p = 0.60.

Table 3.

Univariable analysis of procedures without and with postoperative infection

| Procedures without infection (n = 310) | Procedures with infection (n = 102) | OR (95% CI) | p c | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preoperative | ||||

| Age <6 monthsa | 123 (40) | 73 (72) | 3.83 (2.35–6.23) | <0.001 |

| Preoperative admission PICUa | 49 (16) | 44 (43) | 4.04 (2.46–6.64) | <0.001 |

| Low complexitya | 68 (22) | 10 (9.8) | 1.0 | <0.001 |

| Medium complexitya | 228 (74) | 74 (73) | 2.21 (1.08–4.51) | |

| High complexitya | 14 (4.5) | 18 (18) | 8.74 (3.34–23) | |

| Previous cardiac surgery | 115 (37) | 21 (20) | 0.74 (0.46–1.20) | 0.24 |

| Intraoperative | ||||

| Surgery duration >3 h | 147 (47) | 67 (66) | 2.12 (1.33–3.38) | 0.001 |

| CPB duration >2 ha | 114 (37) | 58 (57) | 2.27 (1.44–3.57) | <0.001 |

| Lowest nasal temp <25°Ca | 80 (26) | 49 (48) | 2.66 (1.67–4.23) | <0.001 |

| Postoperative | ||||

| Inotropes >48 h | 83 (27) | 69 (68) | 5.72 (3.52–9.29) | <0.001 |

| Endotracheal tube >48 h | 66 (21) | 61 (60) | 5.50 (3.40–8.89) | <0.001 |

| PICU stay >48 ha | 105 (34) | 84 (82) | 9.11 (5.20–16) | <0.001 |

| Open sternum at 48 ha | 23 (7.4) | 30 (29) | 5.20 (2.85–9.49) | <0.001 |

| Rethoracotomy | 9 (2.9) | 3 (2.9) | 1.01 (0.27–3.82) | >0.999 |

| RBC transfusion >50 mL/kga,b | 142 (46) | 83 (81) | 5.17 (2.99–8.92) | <0.001 |

| Peak glucose >10 mmol/L in first 24 ha | 151 (49) | 65 (64) | 1.85 (1.17–2.93) | 0.009 |

Variables stated as n (% of infection group)

RBC red blood cell

aThese variables were used in multivariable analysis

bSeven patients had missing data for RBC transfusion and were imputed resulting in the above values

c p values were calculated using Pearson chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate

Bootstrapping resulted in a shrinkage factor of 88%, suggesting some overfitting of the model. Addition of other clinical variables, yielded similar ROC-AUCs (e.g., with addition of surgical complexity, the ROC-AUC remained identical). A complete cases analysis also resulted in the same predictive variables and ROC-AUC. Finally, when proven infections only were used, the final model was similar but with a somewhat reduced ROC-AUC of 0.72 (95% CI 0.65–0.79).

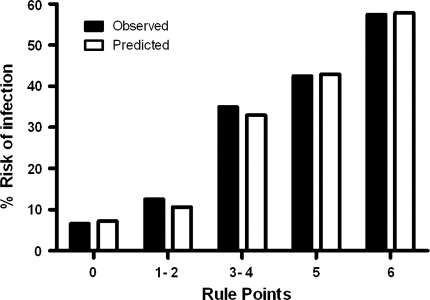

To develop the prediction rule, rule points were derived from the regression coefficients of the three final variables as shown in Table 4. One point was counted if the child was less than 6 months of age at surgery, 4 points if the child had a PICU stay longer than 48 h, and 1 point if the sternum was open for longer than 48 h. For example, a child aged 6 years, already discharged from the PICU, and with a closed sternum will have score of 0, and thus an infection risk of 6.6%. In contrast, a neonate, still at the PICU at 48 h and with an open sternum at that time (maximal score of 6) will have a risk of 57%. Negative and positive predictive values for different cutoff values are shown in Table 5. This shows that when a maximum number of rule points (6) is reached, the positive predictive value is 57.4%; hence, 57% of children with score 6 will likely encounter an infection, whereas 80% of all other children (score 5 or lower) will not become infected. In contrast, out of all children with a score of 1 or higher, 37% will encounter an infection, whereas 93% of all children not belonging to this category (so with a score of 0) will not become infected. Observed and predicted infection rates for all categories are depicted in Fig. 1, where predicted infection risks are calculated for each category using the prediction rule.

Table 4.

Multivariable analysis and derivation of prediction rule points

| Univariable OR (95% CI) | Multivariable OR (95% CI) | p | Multivariable B | Points for rule | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age <6 months | 3.83 (2.35–6.23) | 1.53 (0.86–2.72) | 0.15 | 0.44 | 1 |

| PICU stay >48 h | 9.11 (5.20–16) | 6.30 (3.35–12) | <0.001 | 1.84 | 4 |

| Open sternum >48 h | 5.20 (2.85–9.49) | 1.83 (0.95–3.51) | 0.07 | 0.60 | 1 |

| Total | 6 |

OR odds ratio, B regression coefficient

Table 5.

Performance of various cutoffs for rule points

| Number of rule points | n | True positive (n = 102) | Positive predictive value (%) | n (not in rule points) | True negative (n = 310) | Negative predictive value (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ≥1 | 245 | 91 | 37.1 | 167 | 156 | 93.4 |

| ≥4 | 189 | 84 | 44.4 | 223 | 205 | 91.9 |

| ≥5 | 146 | 69 | 47.3 | 266 | 233 | 87.6 |

| 6 | 47 | 27 | 57.4 | 365 | 290 | 79.5 |

Fig. 1.

Calibration of the prediction rule, with observed and predicted infection risks. Score of 0 points, n = 167; score of 1 or 2 points (pooled), n = 56; score of 3 or 4 points (pooled), n = 43; score of 5 points, n = 99 and score of 6 points, n = 47

Discussion

This study confirms that infections remain a common complication in children recovering from cardiac surgery. We propose a novel bedside scoring system to assess the risk of a postoperative infection in children following cardiac surgery. Using three variables, namely age less than 6 months, postoperative PICU stay longer than 48 h, and open sternum for longer than 48 h, patients at high risk of developing an infection can be distinguished from those at low risk.

Recently, Barker and colleagues [10] similarly developed a prediction rule, designed for clinical use. The model included the variables age, complexity, genetic abnormality, previous cardiac surgery, preoperative length of stay, and preoperative ventilator support. Although their model predicted as well as our study (ROC-AUC of 0.78), variables such as genetic abnormality and surgical complexity are not ideal in a bedside prediction rule, as the former has often not yet been confirmed preoperatively, and the latter demands a search through the extensive lists of Aristotle and RACHS-1 complexity scores. In addition, as the authors point out, many of the infection cases were diagnosed without the use of predefined specific criteria.

The current prediction rule is based on three simple variables: the age of the patient, PICU stay longer than 48 h, and an open sternum for longer than 48 h. Other studies have also shown that these are important risk factors for postoperative infections. Neonates and young infants are known to have an immature immune system lacking a proper innate immune response, likely responsible for the higher rate of infections in this group [2–4, 9, 11, 27]. Prolonged admittance (more than 48 h) at the PICU is commonly associated with longer duration of mechanical ventilation and increased use of intravascular catheters [3, 5, 9, 11]. Furthermore, delayed sternal closure has not only been associated with a higher risk of SSI, but also with an increased occurrence of bloodstream infections [12]. As these two infection types make up the majority of the infections found in this study, this emphasizes the importance of the open sternum as a risk factor.

As our results show, the incidence of postoperative infections remains high. This may be due to the inclusion of all infections, as defined by the CDC criteria (revised in 2008), where not all infections require a positive culture or PCR [15]. Comparing the specific infection incidences to those in the literature, SSI occurred after 6.4% of all procedures in this study, whereas this varies 0.0–9.9% in recent reports [1–4, 9, 13, 27]. Regarding bloodstream infections, these also occurred after 6.4% of all procedures in our study, of which half were proven by cultures and the other half defined as ‘clinical sepsis’. Recent reported incidences vary from 2.6 to 15%, where comparison of incidences is again difficult due to different criteria [1–4, 10]. The isolated pathogens in SSI are in accordance with the reports in the literature, as S. aureus was the most commonly found pathogen in our study [13, 14]. Similarly, bloodstream infections are most often caused by gram-positive species, which our study confirms [28].

Regarding the clinical application of our prediction rule, various options may be possible. Firstly, the rule may be used to determine those patients that are at the highest risk of an infection, i.e., for use in a clinical trial assessing the effectiveness of antimicrobial interventions. Secondly, clinicians may wish to use the model to decide on the routine antibiotic prophylaxis. As the most prevalent infections in our cohort were SSI and bloodstream infections, mostly caused by gram-positive bacteria, and with a median start of 1 week after surgery, a possibility may be to prolong the cefazolin treatment in high-risk groups. This may be prolonged for a set number of days, or for example until drains and/or central lines have been removed, as suggested in a recent study [29]. Overall, improving compliance of personnel to hygiene measures is likely one of the most important issues in infection prevention.

However, a preventive strategy specifically directed at one type of infection may be more effective. It was recently shown in adults that preoperative screening and eradication of S. aureus was an effective preventive measure [30]. Since the end of our study, this has become common practice in our hospital, the results of which have to be evaluated in future. Another preventive strategy against SSI is the continuation of prophylactic antibiotics for 2–3 days after delayed sternal closure, with or without routine culturing of the sternum, which may or may not induce antimicrobial resistance [29, 31, 32]. Regarding bloodstream infections, the use of lines coated with antibiotics, chlorhexidine wound dressings, routine culturing of incision sites, or the continuation of antibiotics are all possible measures to consider [33, 34].

Limitations of this study mainly apply to issues of heterogeneity in the infection cases. As we assessed all types of postoperative infections, we cannot define which risk factors specifically predict a surgical site infection, a bloodstream infection, or an airway infection. This is due to the size of our cohort, which restricts multivariable analyses per subgroup. However, a (smaller) single-center study usually does result in a more homogeneous group as far as perioperative strategies are concerned. Also, all data can be verified, which is crucial to the validity, especially in a study focussed on infections. Another limitation is that the prediction model has not been externally validated. The specific perioperative management at our hospital may differ from others, although our infection cases are very similar to those in the literature. Important characteristics of our perioperative management are the choice of cefazolin as perioperative prophylaxis and the use of dexamethasone during the induction of anesthesia (which may or may not influence susceptibility to infections [35, 36]). Finally, it is important to note that the prediction rule proposed in this study is based on categories of patients. Hence, the individual patient, who may already clinically show signs of a local infection, will likely have higher odds of infection than the predicted ‘baseline’ risk stated in this paper. However, aspecific clinical symptoms such as fever or a high C-reactive protein level after cardiac surgery fail to predict occurrence of an infection, which underlines the need for a reliable prediction rule [37].

In conclusion, postoperative infections remain common in this recent cohort of children undergoing cardiac surgery. Using important risk factors, we have developed a bedside prediction rule which estimates the risk of a subsequent infection during hospital stay. This tool may prove useful for directing preventive measures to those patients at the highest risk.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Prof. A.J. van Vught (Pediatric Intensive Care, University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands) for taking part in our infection expert panel, Dr. M. de Groot (Radiology, University Medical Center Utrecht, the Netherlands) for giving her expert opinion on the chest X-rays, and Dr. R.H.H. Groenwold for assistance with bootstrapping techniques. Project support was entirely from institutional departmental funds.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Footnotes

S. O. Algra and M. M. P. Driessen contributed equally to this article.

References

- 1.Grisaru-Soen G, Paret G, Yahav D, Boyko V, Lerner-Geva L. Nosocomial infections in pediatric cardiovascular surgery patients: a 4-year survey. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2009;10:202–206. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31819a37c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levy I, Ovadia B, Erez E, Rinat S, Ashkenazi S, Birk E, Konisberger H, Vidne B, Dagan O. Nosocomial infections after cardiac surgery in infants and children: incidence and risk factors. J Hosp Infect. 2003;53:111–116. doi: 10.1053/jhin.2002.1359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Valera M, Scolfaro C, Cappello N, Gramaglia E, Grassitelli S, Abbate MT, Rizzo A, Abbruzzese P, Valori A, Longo S, Tovo PA. Nosocomial infections in pediatric cardiac surgery, Italy. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2001;22:771–775. doi: 10.1086/501861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sarvikivi E, Lyytikainen O, Nieminen H, Sairanen H, Saxen H. Nosocomial infections after pediatric cardiac surgery. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:564–569. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urrea M, Pons M, Serra M, Latorre C, Palomeque A. Prospective incidence study of nosocomial infections in a pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2003;22:490–494. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000069758.00079.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Singh-Naz N, Sprague BM, Patel KM, Pollack MM. Risk factors for nosocomial infection in critically ill children: a prospective cohort study. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:875–878. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199605000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richards MJ, Edwards JR, Culver DH, Gaynes RP. Nosocomial infections in pediatric intensive care units in the United States. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. Pediatrics. 1999;103:e39. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.4.e39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Allen ML, Hoschtitzky JA, Peters MJ, Elliott M, Goldman A, James I, Klein NJ. Interleukin-10 and its role in clinical immunoparalysis following pediatric cardiac surgery. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2658–2665. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000240243.28129.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allpress AL, Rosenthal GL, Goodrich KM, Lupinetti FM, Zerr DM. Risk factors for surgical site infections after pediatric cardiovascular surgery. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2004;23:231–234. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000114904.21616.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barker GM, O’Brien SM, Welke KF, Jacobs ML, Jacobs JP, Benjamin DK, Jr, Peterson ED, Jaggers J, Li JS. Major infection after pediatric cardiac surgery: a risk estimation model. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:843–850. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.11.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Costello JM, Graham DA, Morrow DF, Potter-Bynoe G, Sandora TJ, Laussen PC. Risk factors for central line-associated bloodstream infection in a pediatric cardiac intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2009;10:453–459. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e318198b19a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Das S, Rubio A, Simsic JM, Kirshbom PM, Kogon B, Kanter KR, Maher K. Bloodstream infections increased after delayed sternal closure: cause or coincidence. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:793–797. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehta PA, Cunningham CK, Colella CB, Alferis G, Weiner LB. Risk factors for sternal wound and other infections in pediatric cardiac surgery patients. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2000;19:1000–1004. doi: 10.1097/00006454-200010000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nateghian A, Taylor G, Robinson JL. Risk factors for surgical site infections following open-heart surgery in a Canadian pediatric population. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32:397–401. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2004.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan L, Sun X, Zhu X, Zhang Z, Li J, Shu Q. Epidemiology of nosocomial pneumonia in infants after cardiac surgery. Chest. 2004;125:410–417. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.2.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holzmann-Pazgal G, Hopkins-Broyles D, Recktenwald A, Hohrein M, Kieffer P, Huddleston C, Anshuman S, Fraser V. Case-control study of pediatric cardiothoracic surgical site infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29:76–79. doi: 10.1086/524323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michalopoulos A, Geroulanos S, Rosmarakis ES, Falagas ME. Frequency, characteristics, and predictors of microbiologically documented nosocomial infections after cardiac surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;29:456–460. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2005.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tsai CS, Tsai YT, Lin CY, Lin TC, Huang GS, Hong GJ, Lin FY. Expression of thrombomodulin on monocytes is associated with early outcomes in patients with coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Shock. 2010;34:31–39. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0b013e3181d494c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eggum R, Ueland T, Mollnes TE, Videm V, Aukrust P, Fiane AE, Lindberg HL. Effect of perfusion temperature on the inflammatory response during pediatric cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2008;85:611–617. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Qadan M, Gardner SA, Vitale DS, Lominadze D, Joshua IG, Polk HC., Jr Hypothermia and surgery: immunologic mechanisms for current practice. Ann Surg. 2009;250:134–140. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181ad85f7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Brien JE, Jr, Marshall JA, Tarrants ML, Stroup RE, Lofland GK. Intraoperative hyperglycemia and postoperative bacteremia in the pediatric cardiac surgery patient. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;89:578–583. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghafoori AF, Twite MD, Friesen RH. Postoperative hyperglycemia is associated with mediastinitis following pediatric cardiac surgery. Paediatr Anaesth. 2008;18:1202–1207. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9592.2008.02808.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jenkins KJ, Gauvreau K, Newburger JW, Spray TL, Moller JH, Iezzoni LI. Consensus-based method for risk adjustment for surgery for congenital heart disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2002;123:110–118. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2002.119064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lacour-Gayet F, Clarke D, Jacobs J, Comas J, Daebritz S, Daenen W, Gaynor W, Hamilton L, Jacobs M, Maruszsewski B, Pozzi M, Spray T, Stellin G, Tchervenkov C, Mavroudis C, The Aristotle Committee (2004) The Aristotle score: a complexity-adjusted method to evaluate surgical results. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 25:911–924 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Horan TC, Andrus M, Dudeck MA. CDC/NHSN surveillance definition of health care-associated infection and criteria for specific types of infections in the acute care setting. Am J Infect Control. 2008;36:309–332. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Royston P, Moons KG, Altman DG, Vergouwe Y. Prognosis and prognostic research: developing a prognostic model. BMJ. 2009;338:b604. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Belderbos M, Levy O, Bont L. Neonatal innate immunity in allergy development. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2009;21:762–769. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283325e3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prasad PA, Dominguez TE, Zaoutis TE, Shah SS, Teszner E, Gaynor JW, Tabbutt S, Coffin SE. Risk factors for catheter-associated bloodstream infections in a Pediatric Cardiac Intensive Care Unit. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2010;29:812–815. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e3181df6c54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maher KO, VanDerElzen K, Bove EL, Mosca RS, Chenoweth CE, Kulik TJ. A retrospective review of three antibiotic prophylaxis regimens for pediatric cardiac surgical patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:1195–1200. doi: 10.1016/S0003-4975(02)03893-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bode LG, Kluytmans JA, Wertheim HF, Bogaers D, Vandenbroucke-Grauls CM, Roosendaal R, et al. Preventing surgical-site infections in nasal carriers of Staphylococcus aureus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:9–17. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0808939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harbarth S, Samore MH, Lichtenberg D, Carmeli Y. Prolonged antibiotic prophylaxis after cardiovascular surgery and its effect on surgical site infections and antimicrobial resistance. Circulation. 2000;101:2916–2921. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.25.2916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kato Y, Shime N, Hashimoto S, Nomura M, Okayama Y, Yamagishi M, Fujita N. Effects of controlled perioperative antimicrobial prophylaxis on infectious outcomes in pediatric cardiac surgery. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1763–1768. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000269027.50834.FE. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Darouiche RO, Raad II, Heard SO, Thornby JI, Wenker OC, Gabrielli A, Berg J, Khardori N, Hanna H, Hachem R, Harris RL, Mayhall G. A comparison of two antimicrobial-impregnated central venous catheters. Catheter Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901073400101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levy I, Katz J, Solter E, Samra Z, Vidne B, Birk E, Ashkenazi S, Dagan O. Chlorhexidine-impregnated dressing for prevention of colonization of central venous catheters in infants and children: a randomized controlled study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2005;24:676–679. doi: 10.1097/01.inf.0000172934.98865.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clarizia NA, Manlhiot C, Schwartz SM, Sivarajan VB, Maratta R, Holtby HM, Gruenwald CE, Caldarone CA, Van Arsdell GS, McCrindle BW. Improved outcomes associated with intraoperative steroid use in high-risk pediatric cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91:1222–1227. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pasquali SK, Hall M, Li JS, Peterson ED, Jaggers J, Lodge AJ, Marino BS, Goodman DM, Shah SS. Corticosteroids and outcome in children undergoing congenital heart surgery: analysis of the pediatric health information systems database. Circulation. 2010;122:2123–2130. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.948737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McMaster P, Park DY, Shann F, Cochrane A, Morris K, Gray J, Cottrell S, Belcher J. Procalcitonin versus C-reactive protein and immature-to-total neutrophil ratio as markers of infection after cardiopulmonary bypass in children. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2009;10:217–221. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0b013e31819369f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]