Abstract

LOV domains are protein photosensors conserved in bacteria, archaea, plants and fungi that detect blue light via a flavin cofactor. In the bacterial kingdom, LOV domains are present in both chemotrophic and phototrophic species, where they are found N-terminally of signaling and regulatory domains such as sensor histidine kinases, diguanylate cyclases/phosphodiesterases, DNA-binding domains, and σ factor regulators. In this review, we describe the current state of knowledge on the function of bacterial LOV proteins, the structural basis of LOV domain-mediated signal transduction, and the use of LOV domains as genetically-encoded photoswitches in synthetic biology.

Bacteria detect specific intra- and extracellular signals through sensory proteins1,2 and RNAs3–5, which then regulate an adaptive response. There is a detailed understanding of the regulatory response to signals such as nutrient status, oxidative state, osmolar state, and pH, in a handful of model systems. However, in typical natural environments there is tremendous species diversity, and a multitude of potential physical and chemical signals to which a bacterium could, in theory, respond. On this broader scale, we know very little of which signals are relevant to which bacterial species. Over the past decade, a surprising regulatory signal has emerged in the study of bacterial physiology: visible light. Although, the role of visible light in the regulation of photosynthesis and pigment production in phototrophic species is well studied and generally understood6,7, there are decades-old reports of blue light-dependent behavioral8,9 and developmental10,11 phenomena in chemotrophic species that have yet to be ascribed a mechanism. With the discovery of several new classes of blue light photoreceptors 12–14, and the realization that these photoreceptors are encoded across a broad phylogenetic cross-section of bacteria 15, there is a growing appreciation that blue light perception (i.e. light in the wavelength range of 440–480 nm) may be a common attribute.

Light is a ubiquitous signal in terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, and can give important information about niche position. It is, therefore, not surprising that sensory systems that detect photons in the visible range are present in bacterial species. There is a long history of the study of light-dependent DNA damage, whereby photons in the near- and far-ultraviolet region of the spectrum alter the chemical structure of the genetic material. Many bacteria encode photoreceptors that regulate the synthesis of protective pigments or that directly repair photodamaged DNA in response to photon absorption 16,17. There are also bacterial signaling proteins, namely the bacteriophytochromes, that detect red and far-red light and regulate varied cellular responses to these lower energy wavelengths 7. This review does not focus on these UV and red-light response systems but rather on recent developments in our understanding of bacterial cell signaling systems that detect blue photons via a class of flavin-binding photosensors known as Light, Oxygen, or Voltage (LOV) domains (Table 1). In particular, we concentrate on the reported functional roles for LOV protein photoreceptors in both Gram-positive and Gram-negative species, on structural mechanisms of light regulation of LOV protein activity, and on developments in the use of LOV domains in the area of protein engineering and synthetic biology.

Table 1.

Selected LOV proteins from plant, fungi, and bacteria

| Protein name | cofactor | Effector domain | organism | Function | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant | Phot1 | FMN | Ser/Thr kinase | Arabidopsis thaliana, Avena sativa | phototropism, chloroplast movement, stomatal opening | 50,126–128 |

|

|

||||||

| Fungi | Vivid | FAD | - | Neurospora crassa | circadian pigment expression | 28,129 |

| WC-1 | FAD | Zinc finger | Neurospora crassa | circadian photoreceptor, transcription factor | 26,27,30,130, | |

| WC-1 homolog | FMN | Zinc finger | Cryptococcus neoformans, Fusarium oxysporum, Histoplasma capsulatum | circadian photoreceptor, virulence regulation | 29,131–133 | |

|

|

||||||

| Bacteria | YtvA | FMN | STAS | Bacillus subtilis | stress response, sporulation (?) | 37,64,66 |

| Lov-HK | FMN | Histidine kinase | Brucella abortus | virulence regulation | 39 | |

| SL2 | FMN | GGDEF-EAL | Synechococcus elongatus | cyclic-di-GMP phosphodiesterase | 70 | |

| LovK | FMN | Histidine kinase | Caulobacter crescentus | cell adhesion | 38 | |

|

|

||||||

The discovery of LOV domains

Early genetic work on non-phototropic hypocotyl (nph) mutants in Arabidopsis thaliana18 suggested that NPH1 was the photoreceptor for phototropism. NPH1 (subsequently named phototropin) was cloned, sequenced18, and demonstrated to be a photoreceptor serine/threonine kinase that binds a flavin-mononucleotide (FMN) cofactor in each of two N-terminal LOV domains12. LOV domains have since been more strictly defined as a subset of the larger Per-ARNT-Sim (PAS) domain superfamily19, which bind a flavin cofactor (either FMN or FAD) and undergo light-dependent cysteinyl-C4(a) adduct formation 20 via a triplet intermediate 21. In the context of phototropins, blue light absorption by LOV domains regulates autophosphorylation activity of the C-terminal serine/threonine kinase domain22. Phototropins have subsequently been shown to regulate various aspects of plant photomorphogenesis including leaf and stomatal opening, and chloroplast relocation 23 (Table 1).

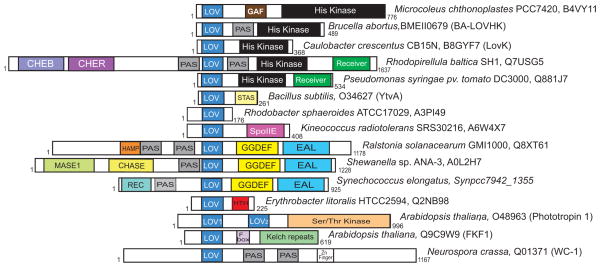

Since the initial discovery 18 and classification 12 of LOV domains in plant phototropins, there has been an explosion in research on molecular and cellular aspects of light-dependent signal transduction mediated by LOV domains. Genes encoding LOV domains coupled to effector domains other than kinases were soon discovered in plants 24,25, fungi 26–30, and stramenopile algae31 and demonstrated to regulate a number of circadian processes and developmental phenomena via the same cysteinyl-C4(a) photochemistry. LOV domains have also been identified in bacterial genomes32,33 where they are coupled to diverse signaling output domains 23,34,35 (Figure 1) and regulate processes including general stress response 36,37, cell envelope physiology 38, and virulence 39(Table 1).

Figure 1.

Domain architecture of select LOV proteins; this cartoon presents just a few examples of hundreds of LOV domain-containing proteins. Accession numbers and formal protein names (if available) are shown. The length of LOV proteins is specified.

LOV domain distribution and evolution

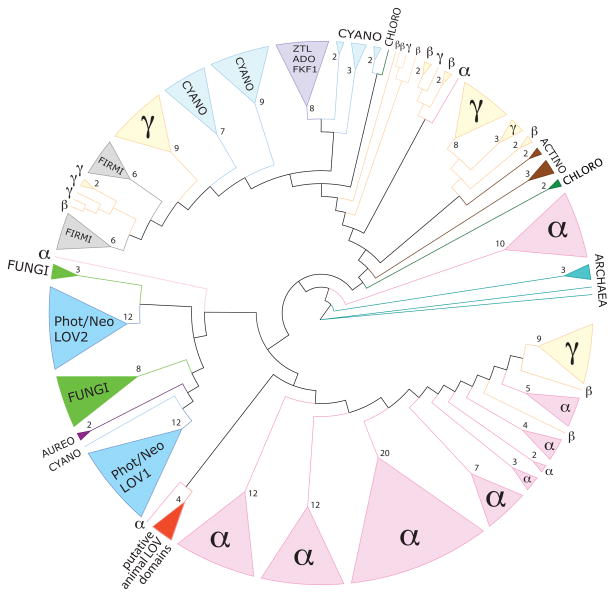

Bioinformatic analyses predict that somewhere between 3.5% 40 to over 10% 15 of sequenced bacterial genomes contain at least one gene encoding a LOV domain. Among the bacteria, the genomes of the alphaproteobacteria and cyanobacteria have the highest number of encoded LOV proteins 40,41. A phylogenetic tree constructed from LOV protein sequences across the three kingdoms of life reveals two distinct subtrees40 (Figure 2). The first sub-tree includes LOV sequences from cyanobacteria, actinobacteria, proteobacteria, firmicutes and chloroflexi. Surprisingly, the sequences of the LOV-domain containing plant circadian regulators, ZTL/ADO/FKF1, are also present in this sub-tree. The second sub-tree consists of eukaryotic sequences from fungi (White Collar-1), plants and algae (phototropin, neochrome and aureochrome) and bacterial sequences predominately from alphaproteobacteria. From this result, it has been suggested that eukaryotic LOV domains present in the circadian plant photoreceptors ZTL/ADO/FKF1 have a cyanobacterial origin whereas the plant phototropin LOV domains, aureochrome LOVs, the fungal White Collar-1-LOVs and the animal LOVs have an alphaproteobacterial origin 40. In accordance with endosymbiotic theory, ancestors of chloroplasts and mitochondria are internalized cyanobacteria and alphaproteobacteria42,43, respectively, that may have transferred their genes to the genomes of a eukaryotic cell post endosymbiosis 44.

Figure 2.

LOV domain sequences are conserved across multiple kingdoms. Tree adapted from Krauss and colleagues 40. LOV sequences of different families are color coded: the archaea in turquoise, alphaproteobacteria (α) in pink, betaproteobacteria (β) and gammaproteobacteria (γ) in yellow, actinobacteria (actino) are in brown, chloroflexi (chloro) in dark green, firmicutes (firmi) in grey, cyanobacteria (cyano) in light blue, fungal sequences from the white-collar 1 (WC-1) protein are in green (fungi), plant phototropin and neochrome (Phot/Neo) LOV domains (LOV1 and LOV2) are in blue, algal aureochrome LOV sequences (aureo) in dark purple, the ZTL/ADO/FKF1-LOV family of plant regulators are in purple, and putative animal LOV domains are in red. Branches have been collapsed; triangle size is proportional to the number of collapsed branches. Numbers of collapsed branches are indicated at the base of each triangle.

Diversity in LOV signaling output

In bacteria, LOV proteins generally follow the domain organization described in other bacterial signalling proteins 45, being arranged with a sensor domain (i.e. LOV) situated N terminally to a linker sequence and an effector/output domain. To date, several different classes of LOV domain and effector domain combinations have been described34,35,46,47 (Table 1 and Figure 1). Among this diverse set, two major groups emerge. The first, LOV-histidine kinases, correspond to approximately 50% of bacterial LOV proteins. The second, LOV-GGDEF/EAL proteins, are predicted to regulate the synthesis and hydrolysis of cyclic-di-GMP and constitute ~20% of bacterial LOV proteins. Other less common LOV signalling proteins include LOV-STAS (Sulfate Transporter Anti-Sigma antagonist) proteins (~10%), LOV Helix-turn-helix (HTH) proteins (~3.5%) and the LOV-SpoIIE (SPOrulation stage II protein E) proteins (~2%). A small number of LOV proteins with a Globin domain, CheB/CheR domains or a Cyclase 4 domain have also been reported47. LOV domains are also found as a single domain or are often associated with additional sensor domains (e.g. other PAS domain, GAF or CHASE domains). Such complex domain arrangements can allow integration of multiple environmental signals and provide mechanisms of light signal amplification or attenuation 48.

LOV domain structure

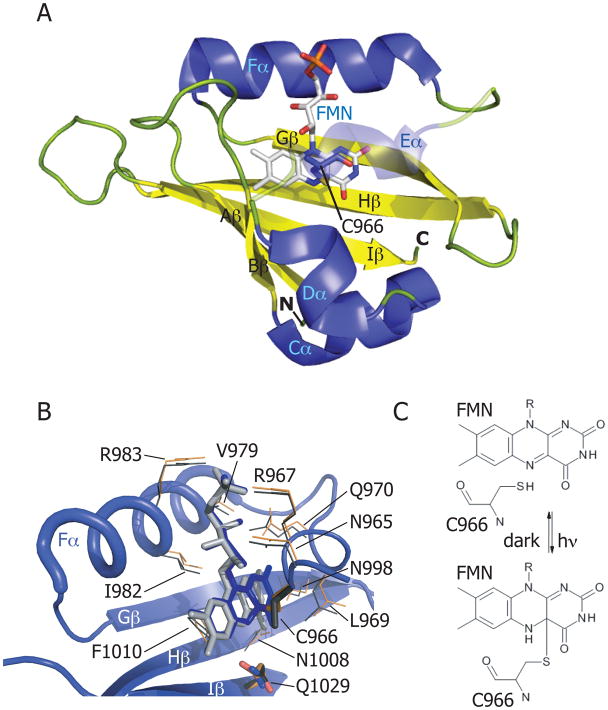

The LOV core domain49 has a classical PAS fold, consisting of a five-stranded antiparallel β sheet (Aβ, Bβ, Gβ, Hβ and Iβ), and helical connector elements (Cα, Dα, Eα and Fα). A flavin chromophore is bound non-covalently in a binding pocket delimited by the core (Figure 3A) 50. As discussed above, an invariant cysteine residue forms a covalent bond with the flavin C(4a) carbon when illuminated with blue light (Figure 3C). This conserved cysteine is located on the Eα helix of the central core in a conserved GXNCRFLQ motif 12 (Figure 3B) and can adopt two distinct conformations in the dark state 51. In most cases, the adduct thermally decays back to the ground state with a half life of minutes to hours, depending on the respective LOV protein 52; in select cases adduct formation is irreversible (or extremely slow) 39,53. Mutational studies have shown that the cysteine is not essential for flavin binding but is essential for the reversible photochemical reaction 20. The dark recovery (i.e. rupture of the cysteinyl-C4a bond) of LOV domains can be modified by pH 21,54,55, salt concentration 54,55, or the presence of low-molecular-weight bases56. These data point toward a mechanism in which structural and solvent effects on the protonation state of flavin N5 control the rate of dark recovery 21,56,57.

Figure 3.

(A) Adiantum capillus-veneris phy3(neochrome)-LOV2 domain in the illuminated state (PDB code: 1JNU). α-helices are colored in blue; β-strands in yellow; loops in green. The FMN cofactor is colored in light gray. Helix Eα is shown as transparent to reveal the cysteinyl-FMN adduct. (B) Flavin-binding pocket of phy3-LOV2 domain. Residues that interact with the FMN cofactor are shown for the illuminated state (PDB code: 1JNU) (in orange), and for the dark state (PDB code: 1G28) (in gray). The glutamine (Q1029) of strand Hβ that rotates 180° on light activation is labeled as is the cysteine that forms the cysteinyl-FMN adduct (C966). (C) Schematic of cysteinyl-C(4a) covalent adduct formation in response to light absorption by the LOV domain.

The function of bacterial LOV proteins

Bacillus YtvA and the general stress response

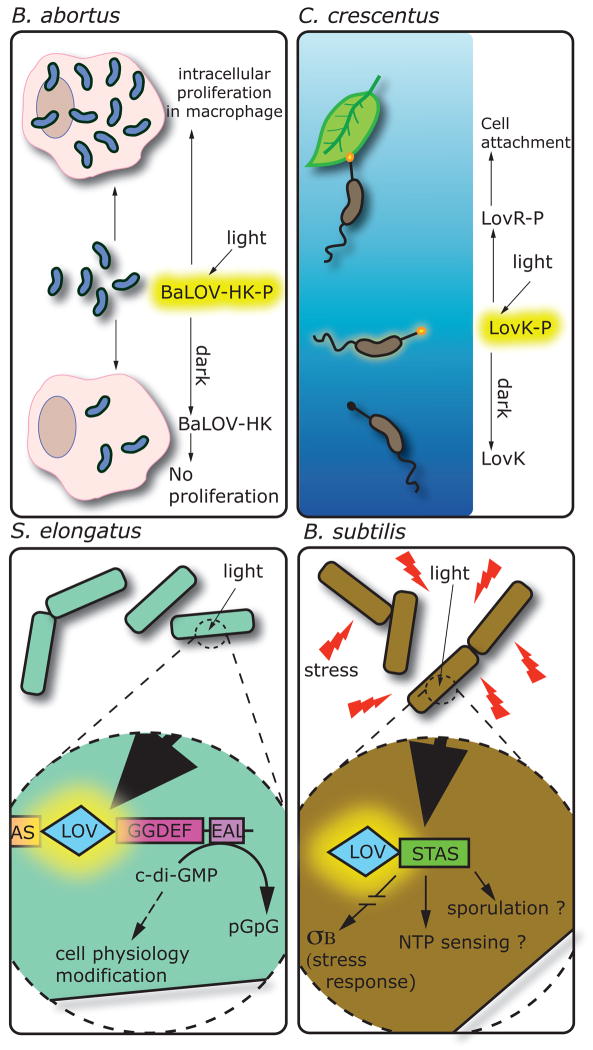

In the Gram-positive soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis, the LOV-STAS protein YtvA (see Table 1 and Figures 1 and 4) binds a flavin cofactor and functions as a photoreceptor in vitro and in vivo. ytvA was initially reported as a positive regulator of the general stress factor σB 36, and later shown to mediate blue light activation of the σB-regulated ctc promoter when overexpressed37. YtvA may be involved in light-dependent control of sporulation as a result of cross regulation between the σB and cell sporulation pathways 37,58. Though light regulation of sporulation has not been demonstrated in B. subtilis, it has been reported that blue light can inhibit sporulation in Bacillus licheniformis 10.

Figure 4.

Biochemical activities and cellular responses affected by LOV photoreceptor proteins in four bacterial species. Brucella abortus: on light activation BaLOV-HK is phosphorylated and positively regulates intracellular proliferation in a macrophage infection model. Caulobacter crescentus: light activation of the LovK protein induces autophophorylation. LovK, together with LovR, regulates cell adhesion through an unknown mechanism. Synechoccocus elongatus: regulation of the phosphodiesterase activity of the EAL domain is controlled by the LOV domain. Thus, light exposure controls the di-c-GMP level of the cell, an important second messenger. Bacillus subtilis: during stress conditions, illumination of the LOV domain of the YtvA protein is an important signal for σB activation and stress response. The associated STAS domain, maybe involved in energy level sensing, could also be regulated by the LOV domain as well as sporulation phenomenon.

YtvA and light regulation of B. subtilis σB occurs through a large protein signalling complex known as the stressosome, which contains several other STAS proteins 59. Although the exact mechanism of this regulation is unknown, our understanding of stressosome signalling has expanded in recent years. Under stress conditions, the B. subtilis STAS domain proteins RsbS and RsbR are phosphorylated by a Serine/Threonine kinase (RsbT) and indirectly regulate σB activity through the stressosome 36,60,61. Phosphorylation of YtvA has not been reported36,62, suggesting that unlike other STAS proteins in the stressosome, YtvA activity is not phosphorylation dependent 36,63. YtvA has been reported to bind GTP in vitro 64–66; mutation of the putative GTP binding site abolishes blue light activation of σB-dependent transcription in vivo 63. Based on these data, it has been proposed that YtvA is a light-dependent NTP recruiter for the RsbT kinase 63. However, the hypothesis that YtvA explicitly requires GTP binding to function merits further investigation 67.

Brucella LOV-HK: light and intracellular proliferation

The Gram-negative intracellular pathogen, Brucella abortus, encodes a LOV histidine kinase (LOV-HK) that exhibits an increase in histidine autophosphorylation on blue light absorption39. Surprisingly, exposure of wild-type B. abortus to visible light results in a 10-fold higher level of cell replication in murine macrophages compared to a dark control39. This light-dependent enhancement of virulence in a macrophage infection model requires LOV-HK and more specifically, the LOV cysteine residue that forms a C4(a) flavin adduct (see Table 1, Figures 1 and 4)39. Once in the adduct state, photoactivated LOV-HK shows negligible decay back to the ground state in vitro, which suggests that once LOV-HK is illuminated in vivo, kinase activity will be similarly long lived39.

Although there is a lack of data on the role of light in the B. abortus life cycle, it is interesting to consider possible links between the light environment and virulence. Light may function as an environmental signal that cues bacteria that have been ejected from a host to upregulate pathways that promote infection of a new host 39,68. We note that alternative B. abortus LOV-HK signalling models, in which environmental cues such as oxidative state or redox potential affect the state of the flavin cofactor and the activity of the histidine kinase have not been explicitly tested. It is certainly possible that LOV-HK may function to integrate multiple environmental signals.

Caulobacter LovK and the regulation of cell adhesion

Phosphorylation of the Caulobacter crescentus LOV histidine kinase, LovK, is regulated by blue light in vitro 38. In vivo, coordinated low-level overexpression of lovK and the adjacent receiver gene, lovR, results in a dramatic increase in cell adhesion that is accentuated by exposing cell cultures to blue light 38 (see Figure 4). Blue-light-dependent enhancement of cell adhesion requires the presence of the conserved cysteine residue in the LOV domain that forms a cysteinyl-flavin adduct. A recent biochemical analysis of C. crescentus LovK has demonstrated that the reduction midpoint of the LovK flavin cofactor is −260 mV, which is poised near the redox potential of the cytosol69. Given that the capacity of LOV domains to function as photosensors requires the flavin cofactor be in the oxidized state, cellular redox state could affect flavin redox state and accordingly influence the LOV photoactivity. Indeed, reduction of the LovK FMN cofactor in vitro ablates light-dependent regulation of kinase activity69.

As with B. abortus, it is not immediately evident why blue light should affect C. crescentus cell physiology. C. crescentus is an oligotrophic bacterium that has evolved in dilute freshwater environments. Blue wavelengths efficiently penetrate the water column; thus light could provide an environmental signal that informs Caulobacter about its niche position. However, the observation that redox state can modulate the function of LovK as a photosensor suggests that signalling through LovK may be more complex than initially believed.

Control of cyclic di-GMP turnover in Synechococcus

A protein from the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus, containing an N-terminal LOV domain and a C-terminal GGDEF-EAL domain (see Table 1, Figures 1 and 4) exhibits blue light-inducible phosphodiesterase activity in vitro70. GGDEF and EAL are conserved domains that typically function as diguanylate cyclases and phosphodiesterases, respectively 71. The molecule synthesized and hydrolysed by these domains, cyclic di-GMP, is a second messenger involved in the regulation of biofilm, motility, and virulence. Blue light may therefore regulate multiple aspects of S. elongatus cell physiology by altering the concentration of cyclic di-GMP in the cell. Certainly, LOV-GGDEF-EAL proteins are among the most common LOV proteins in bacteria suggesting that light-dependent modulation of cytosolic cyclic-di-GMP may be a common phenomenon.

LOV domain signalling mechanisms

Clearly, LOV domains are versatile photoswitches. This raises an interesting mechanistic question: how do LOV domains regulate such a structurally disparate group of proteins? This question has been reviewed more generally for the PAS domain superfamily by Möglich and Moffat 72. Here we synthesize current data on LOV domain molecular structure and signaling mechanism. Biophysical and structural data on LOV domains centre on four very different proteins: plant/algal phototropin, the BacillusσB regulator YtvA, Neurospora crassa VVD, and the light-dependent DNA-binding protein EL222 of Erythrobacter litoralis. We primarily focus on these systems.

Jα helix unfolding in phot-LOV2

Plant and algal phototropins contain two N-terminal LOV domains (LOV1 and LOV2) followed by a serine/threonine kinase (see Figure 1). Phototropin LOV1 and LOV2 have a high degree of sequence conservation but phylogenetically cluster into two distinct clades (Figure 2) and have unique kinetic properties 20. LOV1 forms dimers in solution, suggesting it may have a role in full-length photoreceptor dimerization during light exposure 73,74. There is also evidence that LOV1 modulates kinase photoregulation by LOV2 75. Nevertheless, the functional role of LOV1 in the regulation of phototropin kinase activity is not as well understood as LOV2, which is both necessary and sufficient for kinase activation 76. Differences in lit state structure and dynamics between LOV1 and LOV2 almost certainly reflect the unique regulatory functions of each of these domains.

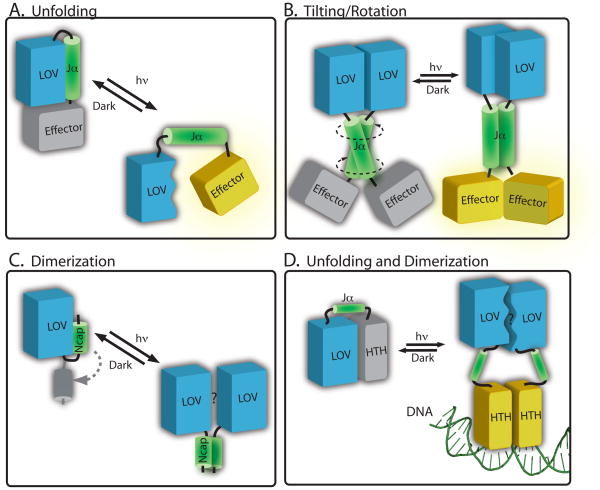

Gardner and colleagues were the first to demonstrate that structural elements outside the LOV domain core can undergo light-induced conformational changes 77. They identified a C-terminal amphipathic helix (Jα) on Avena sativa (i.e. oat) phot1 LOV2, which is conserved in the phototropins and undocks and unfolds on illumination. The solution structure 77 and crystal structure 78 of A. sativa phot1 LOV2 domain show that Jα interacts with the β-sheet, burying hydrophobic surfaces on both (see Figure 5A). On photon absorption and adduct formation, the binding equilibrium between Jα and β-sheet is destabilized by approximately 4 kcal/mol 79. This disruption of the Jα/β-sheet interaction occurs despite the absence of large changes in the overall structure of the LOV core77,80–83. Mutational destabilization of the Jα/β-sheet interaction constitutively-activates the serine/threonine kinase84 (Figure 6A). However, isolated phot1 LOV2 domain without the Jα helix can function as light-dependent inhibitor of the kinase activity in trans 75, suggesting the kinase inhibitory function of phot1 LOV2 is encoded in the ≈100-residue LOV core and does not require Jα. The functional role of the structure N-terminal to the LOV core, which forms a helix-turn-helix motif that also docks against a hydrophobic region of the LOV β-sheet 78, has yet to be determined.

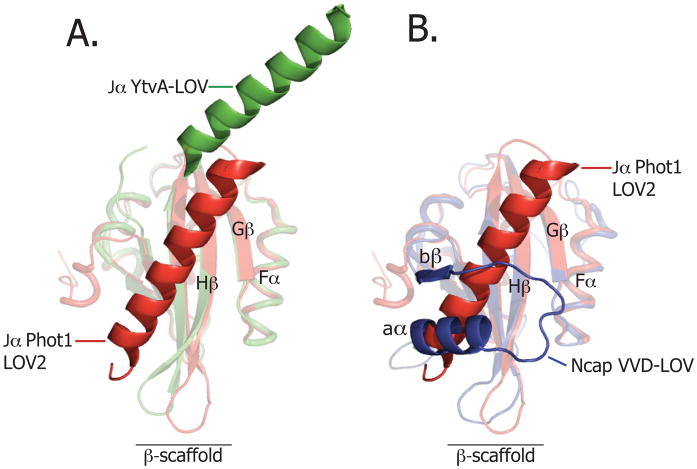

Figure 5.

(A) Structural alignment of the dark-state structure of the YtvA LOV domain of B. subtilis (in green; PDB code: 2PR5) and dark-state phototropin 1 LOV domain of A. sativa (in red; PDB code: 2V0U). (B) Structural alignment of the dark state VVD LOV domain of N. crassa (in blue, PDB code: 2PD7) and the dark Phototropin 1 LOV domain of A. sativa (in red, PDB code: 2V0U).

Figure 6.

Structural models of signalling in LOV proteins (A) In phototropin-type signaling, cysteinyl-flavin adduct formation induces conformational change in the LOV2 domain (blue) that results in disruption of the interaction with the Jα helix (green). This leads to effector domain activation (yellow). Data from YtvA and bacterial LOV histidine kinases evidence models in which illumination of a LOV domain (blue) can induce conformational changes in an extended Jα helix (green), causing (B) tilting or rotational motion to activate the effector (in yellow). (C) In VVD, light activation leads to rearrangement of the N-terminal cap (in green) and a subsequent change in protein dimerization. (D) In the E. litoralis LOV-HTH protein, EL222, it has been proposed that light activation disrupts the interaction surface between the LOV domain and the HTH domain. This light-driven structural change leads to dimerization of the protein on DNA106.

Although data demonstrating light-dependent undocking/unfolding of Jα are clear, the structural mechanism underlying the change in affinity between Jα and the LOV β-sheet is not firmly established. Mutational studies have revealed that residues located in the central β-scaffold are important for signal transduction and phototropin kinase activation 85. In particular, a flavin-interacting glutamine residue of LOV β-strand 5 (Iβ) has been implicated in signal propagation from the β-sheet to Jα 86,87 perhaps driven by glutamine side chain rotation on cysteinyl adduct formation 32,82 (see Figure 3B). From molecular docking studies, it has been proposed that the phot LOV2 domain inhibits kinase activity by binding to the active cleft between the C- and N-terminal lobes of the kinase domain 88. Light-induced unfolding of the Jα helix may result in dissociation of the LOV2 domain from the kinase catalytic region, and opening of the binding cleft to ATP 75,88,89. However, it is unclear how conserved such a mechanism may be given the recent report that light-induced conformational change in the Jα helix varies substantially among phototropins 90.

Another possible mechanism of phototropin kinase regulation by the LOV domain invokes a light-dependent change in the oligomeric state of LOV2. Such a model is supported by data showing an approximate 2-fold transient volume increase of LOV2 during light activation 91, which can be interpreted as a transient dimerization. One can thus envision a mechanism in which the Jα helix prevents dimerization of the LOV2 domains at the β-scaffold interface in the dark. Exposure of the β-scaffold on illumination could drive dimerization of the full-length protein and thus promote kinase activation. Light-dependent oligomerization in LOV domains is discussed further below in the context of the Vivid protein (Figure 5B and 6C).

Tilting and rotation – the YtvA-LOV model

The YtvA regulatory protein is composed of an N-terminal LOV domain linked by Jα to a C-terminal STAS domain 92. The photosensory LOV domain of YtvA was initially identified based on sequence homology to plant phototropins 32,33. However, crystallographic, spectroscopic and biochemical data suggest it is unlike the phototropins in terms of signaling kinetics and light-dependent structural change 66,93–96

The YtvA-LOV domain structure differs from phototropin LOV domains in both quaternary structure and in the orientation of Jα 96, which has been suggested to form a coiled-coil 59,63,97. Indeed, coiled-coil structural motifs are predicted to flank LOV domains in a range of LOV proteins. In both crystal and solution, isolated YtvA-LOV is reported to be dimeric96,98,99 with Jα helices extending from the LOV-core dimer in a quasi-coiled-coil arrangement. As the YtvA Jα helix is connected to the LOV core domain by only a short loop and exhibits a more polar character, it has been proposed that it cannot readily bend and pack against the β-scaffold as described for the phot LOV2 domain. Consequently, the hydrophobic patch on the outer face of the β-scaffold is exposed to solvent and forms a surface for LOV-LOV dimerization96,98.

Structural analyses under light and dark conditions have defined small structural rearrangements in YtvA-LOV on illumination that are dispersed across a large portion of the LOV domain. The Gln residue of β-strand 5 (Iβ) presumably undergoes a reorientation of its side chain 96, consistent with phototropin LOV2 32,82 (Figure 3B). Light-induced structural change is proposed to drive scissor-like rotation of the two monomers by 4–5° relative to each other 96 (Figure 6B). Additional biochemical and structural data are required to resolve how the LOV domain affects the STAS domain conformation and subsequent σB-dependent transcription.

Recent studies of artificial histidine protein kinases composed of the LOV domain of Bacillus YtvA fused to the kinase domain of Bradyrhizobium japonicum FixL provide evidence that histidine kinase activity is regulated by rotational movement in an α-helical coiled-coil (Jα) linking the domains97. Although the extent of quaternary rearrangement in this engineered histidine kinase is not established, spectroscopic analysis of the natural LOV histidine kinase, LovK, of Caulobacter crescentus evidences a model in which small changes in overall tertiary/quaternary structure are sufficient to regulate protein activity100. Additional structural and biochemical studies are necessary to determine the exact structural mechanism (or mechanisms) by which a LOV domain can regulate histidine kinases.

Light-driven dimerization: the VVD Ncap

Our review of the structural basis of signaling in phototropin LOV2 and YtvA-LOV has largely focused on conformational change in the β-scaffold and C-terminal Jα helix. Structural studies on the VIVID (VVD) LOV photosensor of the fungus Neurospora crassa reveal common features with phot-LOV2 and YtvA-LOV, and also provide insight into alternative modes of LOV signaling.

Proper regulation of N. crassa circadian rhythms requires VVD28, which forms a feedback loop with the WC-1 protein to control diurnal gene expression. The VVD protein consists of a single LOV domain flanked by an N-terminal region of structure, termed Ncap (Figure 5B). Ncap is composed of an extended stretch of polypeptide containing an α-helix (aα), a β-strand (bβ) and a short hinge that connects the terminus to the LOV core 101, where it docks at a similar location on the β-scaffold as the C-terminal Jα-helix of phot-LOV2 domain 77,78 (see Figure 5B), the αF helix in the Drosophila Period (Per) protein 102, and the N-terminal cap of photoactive yellow protein (PYP) 103. These regions of structure have all been implicated in conformational switching during signaling 101.

On cysteinyl-flavin adduct formation and reorientation of the Gln residue in β-strand 5 (Iβ), the conformation of the hinge region connecting Ncap to the LOV core is altered 101. Specifically, illumination induces a shift in bβ of ≈2.0Å toward the LOV core, which disrupts packing of Ncap against the β-scaffold 101,104, and results in transition from monomer to a rapidly exchanging VVD dimer 104 (Figure 6C). Although conformational change in the Ncap is important for the function of VVD 101, the exact role of Ncap restructuring and oligomerization as it relates to WC-1 regulation are unknown. WC-1 has a very similar LOV domain to VVD, suggesting homo- and hetero oligomerization of these domains may have an important role in this process 104,105.

Light-dependent DNA binding: Erythrobacter litoralis LOV-HTH

A recent study of the Erythrobacter litoralis LOV-HTH protein EL222 reveals a structural mechanism of regulation with features of both the phototropins and VVD 106. EL222 is a light-regulated DNA-binding protein. In the dark, the protein is monomeric and the HTH domain is docked against the β-scaffold of the LOV domain, with Jα playing the role of a linker between domains (Figure 6D). The authors present evidence that light activation of the EL222 LOV domain disrupts the interface of interaction between LOV and HTH. This structural change ultimately leads to formation of a EL222 dimer on the DNA, the requisite oligomeric state required for HTH-DNA binding. Thus, light activation of a LOV domain is proposed to both promote undocking of HTH from the β-scaffold and to modulate the oligomeric state of EL222 in the presence of DNA.

LOV domains as a tool in synthetic biology

The versatility of LOV domains as a general light-sensing module has been demonstrated by recent successes in the engineering of synthetic LOV protein photosensors. As discussed above, a bacterial LOV domain has been swapped with a related (but non-photoresponsive) PAS domain to create a synthetic light-triggered histidine kinase 97. The FKF1 LOV signaling protein of A. thaliana has been developed as a light-regulated switch that can initiate formation of heteromeric protein complexes in live cells that regulate processes including actin-remodeling and transcription 107. Other groups have taken advantage of the large light-driven conformational change in A. sativa phot1 LOV2 77, and made photoactive fusions with the tryptophan repressor 108, dihyrofolate reductase 109, and the Rac1 GTPase 110 and demonstrated regulation of their activities in vitro or in vivo to varying extents. In these latter cases, there is no evidence that any of these proteins have ever been associated with, or regulated by, a PAS domain over the course of evolutionary history. The success of these engineered systems is even more surprising when one considers the relatively small number of constructs that were tested before the investigators obtained a synthetic light-regulated system. These results in LOV photoprotein engineering suggest there is a low barrier for the natural evolution of new protein function via domain swapping and help explain the great diversity of LOV proteins.

The recent successes of appending LOV domains to a broad range of protein platforms immediately suggest many possible biological and biotechnological applications of this tool 111,112. For example, there are thousands of annotated sensor/effector proteins for which both the signal and physiological output are unknown. In a bacterial context, substitution of the sensor domain of a signaling protein of unknown function with a photo-inducible LOV domain can allow one to probe cellular function. Examples where this approach will be useful include sensor histidine kinases of two-component systems and ligand-binding transcription factors of one-component systems. In this scheme, a LOV domain (and light) could provide a generic signal that could be used to interrogate the physiological response downstream of any signaling protein. For the specific case of a PAS histidine kinase48,97 this proof-of-concept has already been demonstrated. It is conceivable that LOV protein fusions could be engineered in bacteria to perturb dynamical subcellular processes regulated by the cytoskeleton, similar to what has been demonstrated for actin-based motility in mammalian cells using the synthetic LOV-Rac1 system 110.

For those wishing to use LOV domains to toggle the activity of their favorite protein, it may be the case that a LOV domain does not simply work “off the shelf”. In other words, the photochemical, structural or kinetic properties of LOV may need to be engineered to better affect the activity of the protein to which it has been appended. Recent studies have presented both rational design49 and other mutagenesis/screening-based approaches86,113–115 to generate LOV domains with more desirable structural or photochemical properties. Indeed, simple mutation of single residues or short sequences flanking the LOV domain can be sufficient to modulate the signaling lifetime by orders of magnitude 69,111. The exchange of the natural FMN or FAD flavin cofactor for synthetic flavin analogs is an additional approach that may be used to engineer specific photochemical properties into a LOV domain 116.

Conclusions

The LOV domain is an ancient signaling module that has been adapted to serve a range of functional roles in eukaroytes, bacteria and archaea. Genetic and biochemical studies in plant and fungal systems in the mid-1990’s clearly established the role of LOV proteins in the regulation of photomorphogenesis and circadian biology. Since this time, detailed structural and biophysical studies of both isolated LOV domains and, in some cases, full-length LOV proteins have established models for the molecular basis of LOV signal transduction. The discovery of LOV domains in scores of bacterial genomes has motivated new biophysical analyses of LOV proteins and has offered the opportunity to explore novel functional roles for visible light in the bacterial kingdom. Although unexpected regulatory roles for LOV proteins and blue light have been documented in a handful of bacterial species, our understanding of blue light photobiology and LOV protein function in bacteria is in its infancy. Indeed, the sensory role of LOV domains in certain bacteria may be more complex, and integrate information about cellular stress, redox state and light.

Synthetic biology approaches have reinforced the idea that LOV domains provide a genetically-encodable and photoresponsive protein “switch” that can modulate the activity of a structurally-diverse range of signaling proteins and enzymes in both bacterial and eukaryotic systems. In addition, these engineered photosensors should permit investigators to probe nearly any biological or biochemical function with high temporal and spatial resolution. Future work in this exciting area of study promises to yield functional LOV fusions to new classes of proteins, as well as new LOV domains with modified photochemical and kinetic properties.

Text Box. Flavin photochemistry and photobiology: A brief history.

Flavin coenzymes absorb photons in the blue region of the visible spectrum, and can undergo dramatic chemical changes in response to light absorption. Well-known flavin photomodifications, first reported a half century ago, include the photolysis of the ribityl chain of flavin mononucleotide (FMN) to produce the N10 dealkylated species, lumichrome 117,118, or the N10 methylated species lumiflavin 119. In both cases, ribityl photolysis is catalyzed by a highly-oxidizing triplet intermediate on the flavin isoalloxazine moiety formed via intersystem crossing from a singlet excited state. Triplet-dependent degradation of the ribityl chain can be quenched in the presence of alternative electron donors, resulting in simple photoreduction of flavin 119.

Although biological roles for flavin photolysis and photoreduction were not known at the time of these early photochemical studies, it had been postulated since the 1940’s that flavin coenzymes were involved in the regulation of blue light-dependent growth and developmental processes in plants 120,121. It was not until 1993 that the first sequence for a plant blue-light photoreceptor, cryptochrome 1 (CRY1), was reported 122 and later shown to bind a flavin and pterin cofactors 123,124. Although it was initially believed that the cryptochrome family of proteins would control many, if not all, blue light-dependent photoresponses in plants, a cry1 cry2 double mutant in Arabidopsis thaliana was shown to exhibit curvature toward unilateral light 125 indicating another photoreceptor must be responsible for the phototropic response. This other photoreceptor was determined to be the serine/threonine kinase, phototropin 1 (phot 1), which employs LOV domains to sense blue light 18,22.

Summary.

LOV domains are a subset of the PAS domain superfamily that detect blue light through a flavin cofactor. These blue-light photosensory domains are conserved in all kingdoms of life.

In bacteria, LOV domains are naturally found appended to a variety of signal transduction output domains including histidine kinases, diguanylate cyclases/phosphodiesterases, and DNA-binding domains.

Bacterial LOV signaling proteins have been demonstrated to regulate processes including stress response, adhesion, cyclic-di-GMP synthesis, and virulence.

LOV domains regulate the activity of their effector domains through a variety of structural mechanisms including light-dependent unfolding, tilting/rotation, and oligomerization.

Recently, LOV domains have emerged as a powerful tool in protein engineering and synthetic biology. These modular photosensory domains have been used to artificially confer photoactivity on to a range of effector domains including transcription factors, actin remodeling proteins, and protein kinases.

Acknowledgments

We thank John Christie (University of Glasgow), Andreas Möglich (Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin), and Devin Strickland (University of Chicago) for comments on drafts of this manuscript. We also thank the anonymous reviewers of this manuscript for helpful criticism and suggestions. Ulrich Krauss (Forschungszentrum Jülich) generously provided the Newick data file for the LOV domain phylogenetic tree. This work was supported by NIH grant 1R01GM087353-3, and grants from the Mallinckrodt Foundation, and Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation (BYI).

Glossary definitions

- Phototrophic

descriptor of an organism that utilizes solar energy (i.e. photosynthesis) to generate the energy required for cellular metabolism

- Chemotrophic

descriptor of a non-photosynthetic organism that obtains energy for cellular metabolism by oxidizing organic or inorganic electron donors in its environment

- Flavin

a common organic protein cofactor required for many biochemical redox transformations, which also functions as a blue light chromophore in LOV domains

- Phototropism

response in which plants grow toward unidirectional visible light

- Hypocotyl

the stem of a germinating plant seedling

- Adduct formation

In the context of this review, adduct formation is the creation of a covalent bond between the conserved cysteine residue of the LOV domain and the 4a carbon of the flavin cofactor

- Triplet intermediate

an electronic excited state intermediate of the flavin cofactor, through which the cysteinyl-flavin adduct is generated

- Photomorphogenesis

a developmental process regulated by light

- Histidine Kinase

a protein kinase, common in bacteria, which is phosphorylated at a single, conserved histidine residue

- GGDEF/EAL proteins

Enzymes that function to synthesize (GGDEF) or degrade (EAL) the small signaling nucleotide, cyclic-di-GMP

- Chromophore

a small-molecule cofactor or functional group that enables a protein to absorb light

- Redox potential

A measure of the affinity of a particular chemical species for electrons; value is reported as an electrical potential (mV)

- Oligotrophic

descriptor of an organism that lives in an environment that contains very low levels of nutrients

Biographies

Sean Crosson received his B.A. in biology from Earlham College in Richmond, Indiana in 1996. He completed his Ph.D. in biochemistry in the laboratory of Keith Moffat at The University of Chicago in 2002, and was a postdoctoral fellow in the laboratory of Lucy Shapiro at Stanford University School of Medicine from 2003 to 2005. Since 2006, he has been Assistant Professor at The University of Chicago in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and the Committee on Microbiology. His research interests centre on signal transduction and cell regulation in bacteria.

After receiving his undergraduate degree in engineering from Université de Bretagne Occidentale, Julien Herrou began his graduate studies in 2006 in the laboratory of Dr. Camille Locht at Institut Pasteur de Lille, France. During this period, he studied the Bordetella pertussis virulence regulator, BvgAS, under the supervision of Dr. Françoise Jacob-Dubuisson and Dr. Rudy Antoine. Julien obtained his Ph.D. in Biophysics in 2008. Since 2010, he has been a postdoctoral fellow in Sean Crosson’s lab at The University of Chicago, USA where his research has focused on molecular mechanisms of general stress signaling in alphaproteobacteria.

Literature Cited

- 1.Ulrich LE, Koonin EV, Zhulin IB. One-component systems dominate signal transduction in prokaryotes. TRENDS Microbiol. 2005;13:52–56. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wuichet K, Cantwell BJ, Zhulin IB. Evolution and phyletic distribution of two-component signal transduction systems. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2010;13:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Henkin TM. Riboswitch RNAs: using RNA to sense cellular metabolism. Genes Dev. 2008;22:3383–3390. doi: 10.1101/gad.1747308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roth A, Breaker RR. The structural and functional diversity of metabolite-binding riboswitches. Annu Rev Biochem. 2009;78:305–334. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.78.070507.135656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lai EC. RNA sensors and riboswitches: self-regulating messages. Curr Biol. 2003;13:R285–291. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(03)00203-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bailey S, Grossman A. Photoprotection in cyanobacteria: regulation of light harvesting. Photochem Photobiol. 2008;84:1410–1420. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2008.00453.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Purcell EB, Crosson S. Photoregulation in prokaryotes. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11:168–178. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor BL, Koshland DE., Jr Intrinsic and extrinsic light responses of Salmonella typhimurium and Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1975;123:557–569. doi: 10.1128/jb.123.2.557-569.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang H, Inokuchi H, Adler J. Phototaxis away from blue light by an Escherichia coli mutant accumulating protoporphyrin IX. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:7332–7336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Propst-Ricciuti C, Lubin LB. Light-induced inhibition of sporulation in Bacillus licheniformis. J Bacteriol. 1976;128:506–509. doi: 10.1128/jb.128.1.506-509.1976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.White D, Shropshire W, Jr, Stephens K. Photocontrol of development by Stigmatella aurantiaca. J Bacteriol. 1980;142:1023–1024. doi: 10.1128/jb.142.3.1023-1024.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Christie JM, Salomon M, Nozue K, Wada M, Briggs WR. LOV (light, oxygen, or voltage) domains of the blue-light photoreceptor phototropin (nph1): binding sites for the chromophore flavin mononucleotide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:8779–8783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.15.8779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomelsky M, Klug G. BLUF: a novel FAD-binding domain involved in sensory transduction in microorganisms. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:497–500. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02181-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hitomi K, et al. Bacterial cryptochrome and photolyase: characterization of two photolyase-like genes of Synechocystis sp. PCC6803. Nuc Acids Res. 2000;28:2353–2362. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.12.2353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Losi A, Gärtner W. Bacterial bilin- and flavin-binding photoreceptors. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2008;7:1168–1178. doi: 10.1039/b802472c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pattison DI, Davies MJ. Actions of ultraviolet light on cellular structures. EXS. 2006:131–157. doi: 10.1007/3-7643-7378-4_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sancar A. Photolyase and cryptochrome blue-light photoreceptors. Adv Protein Chem. 2004;69:73–100. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3233(04)69003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huala E, et al. Arabidopsis NPH1: a protein kinase with a putative redox-sensing domain. Science. 1997;278:2120–2123. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5346.2120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Taylor BL, Zhulin IB. PAS domains: internal sensors of oxygen, redox potential, and light. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:479–506. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.2.479-506.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salomon M, Christie JM, Knieb E, Lempert U, Briggs WR. Photochemical and mutational analysis of the FMN-binding domains of the plant blue light receptor, Phototropin. Biochemistry. 2000;39:9401–9410. doi: 10.1021/bi000585+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Swartz TE, et al. The photocycle of a flavin-binding domain of the blue light photoreceptor phototropin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36493–36500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M103114200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Christie JM, et al. Arabidopsis NPH1: a flavoprotein with the properties of a photoreceptor for phototropism. Science. 1998;282:1698–1701. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5394.1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Briggs WR. The LOV domain: a chromophore module servicing multiple photoreceptors. J Biomed Sci. 2007;14:499–504. doi: 10.1007/s11373-007-9162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson DC, Lasswell J, Rogg LE, Cohen MA, Bartel B. FKF1, a clock-controlled gene that regulates the transition to flowering in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2000;101:331–340. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80842-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Somers DE, Schultz TF, Milnamow M, Kay SA. ZEITLUPE encodes a novel clock-associated PAS protein from Arabidopsis. Cell. 2000;101:319–329. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80841-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ballario P, Talora C, Galli D, Linden H, Macino G. Roles in dimerization and blue light photoresponse of the PAS and LOV domains of Neurospora crassa white collar proteins. Mol Microbiol. 1998;29:719–729. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Froehlich AC, Liu Y, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC. White Collar-1, a circadian blue light photoreceptor, binding to the frequency promoter. Science. 2002;297:815–819. doi: 10.1126/science.1073681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Heintzen C, Loros JJ, Dunlap JC. The PAS protein VIVID defines a clock-associated feedback loop that represses light input, modulates gating, and regulates clock resetting. Cell. 2001;104:453–464. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00232-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Idnurm A, Heitman J. Light controls growth and development via a conserved pathway in the fungal kingdom. Plos Biology. 2005;3:615–626. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwerdtfeger C, Linden H. Blue light adaptation and desensitization of light signal transduction in Neurospora crassa. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:1080–1087. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takahashi F, et al. AUREOCHROME, a photoreceptor required for photomorphogenesis in stramenopiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:19625–19630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707692104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crosson S, Moffat K. Photoexcited structure of a plant photoreceptor domain reveals a light-driven molecular switch. Plant Cell. 2002;14:1067–1075. doi: 10.1105/tpc.010475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Losi A, Polverini E, Quest B, Gartner W. First evidence for phototropin-related blue-light receptors in prokaryotes. Biophys J. 2002;82:2627–2634. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75604-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crosson S, Rajagopal S, Moffat K. The LOV domain family: Photoresponsive signaling modules coupled to diverse output domains. Biochemistry. 2003;42:2–10. doi: 10.1021/bi026978l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Losi A. The bacterial counterparts of plant phototropins. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2004;3:566–574. doi: 10.1039/b400728j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akbar S, et al. New family of regulators in the environmental signaling pathway which activates the general stress transcription factor σB of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:1329–1338. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.4.1329-1338.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Avila-Pérez M, Hellingwerf KJ, Kort R. Blue light activates the σB-dependent stress response of Bacillus subtilis via YtvA. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:6411–6414. doi: 10.1128/JB.00716-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Purcell EB, Siegal-Gaskins D, Rawling DC, Fiebig A, Crosson S. A photosensory two-component system regulates bacterial cell attachment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:18241–18246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705887104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Swartz TE, et al. Blue-light-activated histidine kinases: two-component sensors in bacteria. Science. 2007;317:1090–1093. doi: 10.1126/science.1144306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Krauss U, et al. Distribution and phylogeny of light-oxygen-voltage blue-light-signaling proteins in the three kingdoms of life. J Bacteriol. 2009;191:7234–7242. doi: 10.1128/JB.00923-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Losi A, Gärtner W. Old chromophores, new photoactivation paradigms, trendy applications: flavins in LOV and BLUF photoreceptors. Photochem Photobiol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2011.00913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McFadden GI. Chloroplast origin and integration. Plant Physiol. 2001;125:50–53. doi: 10.1104/pp.125.1.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Esser C, Martin W, Dagan T. The origin of mitochondria in light of a fluid prokaryotic chromosome model. Biol Lett. 2007;3:180–184. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2006.0582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Timmis JN, Ayliffe MA, Huang CY, Martin W. Endosymbiotic gene transfer: organelle genomes forge eukaryotic chromosomes. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:123–135. doi: 10.1038/nrg1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parkinson JS. Signal transduction schemes of bacteria. Cell. 1993;73:857–871. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90267-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Losi A. In: Flavins - Photochemistry and Photobiology. Silva E, Edwards AM, editors. RCS Publishing; 2006. pp. 217–269. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Losi A. A table of prokaryotic LOV proteins. 2010 < http://www.fis.unipr.it/home/aba.losi/Lov-proteinstable.pdf>.

- 48.Möglich A, Ayers RA, Moffat K. Addition at the Molecular Level: Signal Integration in Designed Per-ARNT-Sim Receptor Proteins. J Mol Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strickland D, et al. Rationally improving LOV domain-based photoswitches. Nat Methods. 2010;7:623–626. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Crosson S, Moffat K. Structure of a flavin-binding plant photoreceptor domain: Insights into light-mediated signal transduction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2995–3000. doi: 10.1073/pnas.051520298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fedorov R, et al. Crystal Structures and Molecular Mechanism of a Light-Induced Signaling Switch: The Phot-LOV1 Domain from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Biophys J. 2003;84:2474–2482. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75052-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Losi A. Flavin-based Blue-light Photosensors: A Photobiophysics Update. Photochem Photobiol. 2007;83:1283–1300. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2007.00196.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Swartz TE, Bogomolni RA. In: Handbook of Photosensory Receptors. Briggs WR, Spudich JL, editors. Wiley-VCH; 2005. pp. 305–323. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guo H, Kottke T, Hegemann P, Dick B. The phot LOV2 domain and its interaction with LOV1. Biophys J. 2005;89:402–412. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.058230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kottke T, Heberle J, Hehn D, Dick B, Hegemann P. Phot-LOV1: photocycle of a blue-light receptor domain from the green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Biophys J. 2003;84:1192–1201. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74933-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Alexandre MTA, Arents JC, van Grondelle R, Hellingwerf KJ, Kennis JTM. A base-catalyzed mechanism for dark state recovery in the Avena sativa phototropin-1 LOV2 domain. Biochemistry. 2007;46:3129–3137. doi: 10.1021/bi062074e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zoltowski BD, Vaccaro B, Crane BR. Mechanism-based tuning of a LOV domain photoreceptor. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:827–834. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Avila-Perez M, van der Steen JB, Kort R, Hellingwerf KJ. Red light activates the sigmaB-mediated general stress response of Bacillus subtilis via the energy branch of the upstream signaling cascade. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:755–762. doi: 10.1128/JB.00826-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marles-Wright J, et al. Molecular architecture of the “stressosome,” a signal integration and transduction hub. Science. 2008;322:92–96. doi: 10.1126/science.1159572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Delumeau O, Chen CC, Murray JW, Yudkin MD, Lewis RJ. High-molecular-weight complexes of RsbR and paralogues in the environmental signaling pathway of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:7885–7892. doi: 10.1128/JB.00892-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kim TJ, Gaidenko TA, Price CW. In vivo phosphorylation of partner switching regulators correlates with stress transmission in the environmental signaling pathway of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:6124–6132. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.18.6124-6132.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gaidenko TA, Kim TJ, Weigel AL, Brody MS, Price CW. The blue-light receptor YtvA acts in the environmental stress signaling pathway of Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:6387–6395. doi: 10.1128/JB.00691-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Avila-Pérez M, et al. In vivo mutational analysis of YtvA from Bacillus subtilis: mechanism of light activation of the general stress response. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:24958–24964. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.033316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Buttani V, Gärtner W, Losi A. NTP-binding properties of the blue-light receptor YtvA and effects of the E105L mutation. Eur Biophys J. 2007;36:831–839. doi: 10.1007/s00249-007-0155-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Buttani V, Losi A, Polverini E, Gartner W. Blue news: NTP binding properties of the blue-light sensitive YtvA protein from Bacillus subtilis. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:3818–3822. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tang Y, et al. Interdomain signalling in the blue-light sensing and GTP-binding protein YtvA: a mutagenesis study uncovering the importance of specific protein sites. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2010;9:47–56. doi: 10.1039/b9pp00075e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nakasone Y, Hellingwerf KJ. On the Binding of BODIPY-GTP by the Photosensory Protein YtvA from the Common Soil Bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Photochem Photobiol. 2011;87:542–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2011.00919.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kennis JT, Crosson S. A bacterial pathogen sees the light. Science. 2007;317:1041–1042. doi: 10.1126/science.1147609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Purcell EB, McDonald CA, Palfey BA, Crosson S. An analysis of the solution structure and signaling mechanism of LovK, a sensor histidine kinase integrating light and redox signals. Biochemistry. 2010;49:6761–6770. doi: 10.1021/bi1006404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Cao Z, Livoti E, Losi A, Gartner W. A blue light-inducible phosphodiesterase activity in the cyanobacterium Synechococcus elongatus. Photochem Photobiol. 2010;86:606–611. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.2010.00724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hengge R. Principles of c-di-GMP signalling in bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:263–273. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Möglich A, Ayers RA, Moffat K. Structure and signaling mechanism of Per-ARNT-Sim domains. Structure. 2009;17:1282–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Liscum E, Stowe-Evans EL. Phototropism: a “simple” physiological response modulated by multiple interacting photosensory-response pathways. Photochem Photobiol. 2000;72:273–282. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2000)072<0273:pasprm>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Salomon M, Lempert U, Rüdiger W. Dimerization of the plant photoreceptor phototropin is probably mediated by the LOV1 domain. FEBS Lett. 2004;572:8–10. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.06.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Matsuoka D, Tokutomi S. Blue light-regulated molecular switch of Ser/Thr kinase in phototropin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13337–13342. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506402102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Christie JM, Swartz TE, Bogomolni RA, Briggs WR. Phototropin LOV domains exhibit distinct roles in regulating photoreceptor function. Plant J. 2002;32:205–219. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2002.01415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Harper SM, Neil LC, Gardner KH. Structural basis of a phototropin light switch. Science. 2003;301:1541–1544. doi: 10.1126/science.1086810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Halavaty AS, Moffat K. N- and C-terminal flanking regions modulate light-induced signal transduction in the LOV2 domain of the blue light sensor phototropin 1 from Avena sativa. Biochemistry. 2007;46:14001–14009. doi: 10.1021/bi701543e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yao X, Rosen MK, Gardner KH. Estimation of the available free energy in a LOV2-J alpha photoswitch. Nat Chem Biol. 2008;4:491–497. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Alexandre MT, van Grondelle R, Hellingwerf KJ, Kennis JT. Conformational heterogeneity and propagation of structural changes in the LOV2/J-alpha domain from Avena sativa phototropin 1 as recorded by temperature-dependent FTIR spectroscopy. Biophys J. 2009;97:238–247. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2009.03.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Iwata T, et al. Light-induced structural changes in the LOV2 domain of Adiantum phytochrome3 studied by low-temperature FTIR and UV-visible spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2003;42:8183–8191. doi: 10.1021/bi0345135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nozaki D, et al. Role of Gln1029 in the photoactivation processes of the LOV2 domain in Adiantum phytochrome3. Biochemistry. 2004;43:8373–8379. doi: 10.1021/bi0494727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yamamoto A, et al. Light signal transduction pathway from flavin chromophore to the J alpha helix of Arabidopsis phototropin1. Biophys J. 2009;96:2771–2778. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2008.12.3924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Harper SM, Neil LC, Day IJ, Hore PJ, Gardner KH. Conformational changes in a photosensory LOV domain monitored by time-resolved NMR spectroscopy. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:3390–3391. doi: 10.1021/ja038224f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Jones MA, Christie JM. Phototropin receptor kinase activation by blue light. Plant Signal Behav. 2008;3:44–46. doi: 10.4161/psb.3.1.4848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jones MA, Feeney KA, Kelly SM, Christie JM. Mutational analysis of phototropin 1 provides insights into the mechanism underlying LOV2 signal transmission. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6405–6414. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605969200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nash AI, Ko WH, Harper SM, Gardner KH. A conserved glutamine plays a central role in LOV domain signal transmission and its duration. Biochemistry. 2008;47:13842–13849. doi: 10.1021/bi801430e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Tokutomi S, Matsuoka D, Zikihara K. Molecular structure and regulation of phototropin kinase by blue light. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1784:133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pfeifer A, Mathes T, Lu Y, Hegemann P, Kottke T. Blue light induces global and localized conformational changes in the kinase domain of full-length phototropin. Biochemistry. 2010;49:1024–1032. doi: 10.1021/bi9016044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Koyama T, et al. Different role of the Jalpha helix in the light-induced activation of the LOV2 domains in various phototropins. Biochemistry. 2009;48:7621–7628. doi: 10.1021/bi9009192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nakasone Y, Eitoku T, Matsuoka D, Tokutomi S, Terazima M. Kinetic measurement of transient dimerization and dissociation reactions of Arabidopsis phototropin 1 LOV2 domain. Biophys J. 2006;91:645–653. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.084772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Aravind L, Koonin EV. The STAS domain - a link between anion transporters and antisigma-factor antagonists. Curr Biol. 2000;10:R53–55. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00335-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bednarz T, Losi A, Gärtner W, Hegemann P, Heberle J. Functional variations among LOV domains as revealed by FT-IR difference spectroscopy. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2004;3:575–579. doi: 10.1039/b400976b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Buttani V, et al. Conformational analysis of the blue-light sensing protein YtvA reveals a competitive interface for LOV-LOV dimerization and interdomain interactions. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2007;6:41–49. doi: 10.1039/b610375h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Losi A, Quest B, Gartner W. Listening to the blue: the time-resolved thermodynamics of the bacterial blue-light photoreceptor YtvA and its isolated LOV domain. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2003;2:759–766. doi: 10.1039/b301782f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Möglich A, Moffat K. Structural basis for light-dependent signaling in the dimeric LOV domain of the photosensor YtvA. J Mol Biol. 2007;373:112–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.07.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Möglich A, Ayers RA, Moffat K. Design and signaling mechanism of light-regulated histidine kinases. J Mol Biol. 2009;385:1433–1444. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Losi A, Ghiraldelli E, Jansen S, Gärtner W. Mutational effects on protein structural changes and interdomain interactions in the blue-light sensing LOV protein YtvA. Photochem Photobiol. 2005;81:1145–1152. doi: 10.1562/2005-05-25-RA-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jurk M, et al. The switch that does not flip: the blue-light receptor YtvA from Bacillus subtilis adopts an elongated dimer conformation independent of the activation state as revealed by a combined AUC and SAXS study. J Mol Biol. 2010;403:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Alexandre MT, et al. Electronic and protein structural dynamics of a photosensory histidine kinase. Biochemistry. 2010;49:4752–4759. doi: 10.1021/bi100527a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Zoltowski BD, et al. Conformational switching in the fungal light sensor Vivid. Science. 2007;316:1054–1057. doi: 10.1126/science.1137128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yildiz O, et al. Crystal structure and interactions of the PAS repeat region of the Drosophila clock protein PERIOD. Mol Cell. 2005;17:69–82. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Borgstahl GE, Williams DR, Getzoff ED. 1.4 Å structure of photoactive yellow protein, a cytosolic photoreceptor: unusual fold, active site, and chromophore. Biochemistry. 1995;34:6278–6287. doi: 10.1021/bi00019a004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Zoltowski BD, Crane BR. Light activation of the LOV protein vivid generates a rapidly exchanging dimer. Biochemistry. 2008;47:7012–7019. doi: 10.1021/bi8007017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Lamb JS, et al. Illuminating solution responses of a LOV domain protein with photocoupled small-angle X-ray scattering. J Mol Biol. 2009;393 doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.08.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Nash AI, et al. Structural basis of photosensitivity in a bacterial light-oxygen-voltage/helix-turn-helix (LOV-HTH) DNA-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:9449–9454. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1100262108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Yazawa M, Sadaghiani AM, Hsueh B, Dolmetsch RE. Induction of protein-protein interactions in live cells using light. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:941–945. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Strickland D, Moffat K, Sosnick TR. Light-activated DNA binding in a designed allosteric protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:10709–10714. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709610105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lee J, et al. Surface sites for engineering allosteric control in proteins. Science. 2008;322:438–442. doi: 10.1126/science.1159052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wu YI, et al. A genetically encoded photoactivatable Rac controls the motility of living cells. Nature. 2009;461:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature08241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zoltowski BD, Gardner KH. Tripping the Light Fantastic: Blue-Light Photoreceptors as Examples of Environmentally Modulated Protein-Protein Interactions. Biochemistry. 2011;50:4–16. doi: 10.1021/bi101665s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Moglich A, Moffat K. Engineered photoreceptors as novel optogenetic tools. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2010;9:1286–1300. doi: 10.1039/c0pp00167h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Christie JM, et al. Steric interactions stabilize the signaling state of the LOV2 domain of phototropin 1. Biochemistry. 2007;46:9310–9319. doi: 10.1021/bi700852w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chapman S, et al. The photoreversible fluorescent protein iLOV outperforms GFP as a reporter of plant virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:20038–20043. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807551105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Raffelberg S, Mansurova M, Gärtner W, Losi A. Modulation of the Photocycle of a LOV Domain Photoreceptor by the Hydrogen-Bonding Network. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:5346–5356. doi: 10.1021/ja1097379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Mansurova M, Scheercousse P, Simon J, Kluth M, Gärtner W. Chromophore Exchange in the Blue Light-Sensitive Photoreceptor YtvA from Bacillus subtilis. Chembiochem. 2011;12:641–646. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Boyer PD, Lardy H, Myrbäck K. The Enzymes. II. Academic Press; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 118.Massey V, Veeger C. Biological oxidations. Annu Rev Biochem. 1963;32:579–638. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.32.070163.003051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Hemmerich P, Veeger C, Wood HCS. Progress in the chemistry and molecular biology of flavins and flavocoenzymes. Angew Chem Internat Edit. 1965;4:671–687. doi: 10.1002/anie.196506711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Galston AW. Riboflavin, light, and the growth of plants. Science. 1950;111:619–624. doi: 10.1126/science.111.2893.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Galston AW, Baker RS. Inactivation of enzymes by visible light in the presence of riboflavin. Science. 1949;109:485–486. doi: 10.1126/science.109.2837.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ahmad M, Cashmore AR. HY4 gene of A. thaliana encodes a protein with characteristics of a blue-light photoreceptor. Nature. 1993;366:162–166. doi: 10.1038/366162a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Lin CT, et al. Association of flavin adenine-dinucleotide with the Arabidopsis blue-light receptor CRY1. Science. 1995;269:968–970. doi: 10.1126/science.7638620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Malhotra K, Kim ST, Batschauer A, Dawut L, Sancar A. Putative blue-light photoreceptors from Arabidopsis thaliana and Sinapis alba with a high degree of sequence homology to DNA photolyase contain the 2 photolyase cofactors but lack DNA-repair activity. Biochemistry. 1995;34:6892–6899. doi: 10.1021/bi00020a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Briggs WR, Huala E. Blue-light photoreceptors in higher plants. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1999;15:33–62. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.15.1.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Christie JM. Phototropin blue-light receptors. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2007;58:21–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.58.032806.103951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Chen M, Chory J, Fankhauser C. Light signal transduction in higher plants. Annu Rev Genet. 2004;38:87–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.092259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Möglich A, Yang X, Ayers RA, Moffat K. Structure and function of plant photoreceptors. Annu Rev Plant Biol. 2010;61:21–47. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-042809-112259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Schwerdtfeger C, Linden H. VIVID is a flavoprotein and serves as a fungal blue light photoreceptor for photoadaptation. EMBO J. 2003;22:4846–4855. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Brunner M, Kaldi K. Interlocked feedback loops of the circadian clock of Neurospora crassa. Mol Microbiol. 2008;68:255–262. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06148.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Ruiz-Roldan MC, Garre V, Guarro J, Marine M, Roncero MIG. Role of the White collar-1 photoreceptor in carotenogenesis, UV resistance, hydrophobicity, and virulence of Fusarium oxysporum. Eukaryot Cell. 2008;7:1227–1230. doi: 10.1128/EC.00072-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Campbell CC, Berliner MD. Virulence Differences in Mice of Type a and B Histoplasma capsulatum Yeasts Grown in Continuous Light and Total Darkness. Infect Immun. 1973;8:677–678. doi: 10.1128/iai.8.4.677-678.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Madhani HD, et al. Systematic genetic analysis of virulence in the human fungal pathogen Cryptococcus neoformans. Cell. 2008;135:174–188. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]