Abstract

Background

Asymptomatic severe mitral valve (MV) regurgitation with preserved left ventricular function is a challenging clinical entity as data on the recommended treatment strategy for these patients are scarce and conflicting. For asymptomatic patients, no randomised trial has been performed for objectivising the best treatment strategy.

Methods

The Dutch AMR (Asymptomatic Mitral Regurgitation) trial is a multicenter, prospective, randomised trial comparing early MV repair versus watchful waiting in asymptomatic patients with severe organic MV regurgitation. A total of 250 asymptomatic patients (18–70 years) with preserved left ventricular function will be included. Intervention will be either watchful waiting or MV surgery. Follow-up will be 5 years. Primary outcome measures are all-cause mortality and a composite endpoint of cardiovascular mortality, congestive heart failure, and hospitalisation for non-fatal cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events. Secondary outcome measures are total costs, cost-effectiveness, quality of life, echocardiographic and cardiac magnetic resonance parameters, exercise tests, asymptomatic atrial fibrillation and brain natriuretic peptide levels. Additionally, the complication rate in the surgery group and rate of surgery in the watchful waiting group will be determined.

Implications

The Dutch AMR trial will be the first multicenter randomised trial on this topic. We anticipate that the results of this study are highly needed to elucidate the best treatment strategy and that this may prove to be an international landmark study.

Keywords: Asymptomatic mitral regurgitation, Early surgery, Watchful waiting, Dutch AMR

Introduction

Mitral valve (MV) regurgitation is the second most frequent valvular disease after aortic valve stenosis. It is divided into organic, ischaemic and functional disease [1]. Ischaemic and functional MV regurgitation are due to left ventricular dysfunction. In the present trial we focus on organic MV regurgitation which is caused by leaflet abnormalities.

MV surgery has changed significantly over the last years. If patients undergo MV replacement their life expectancy is lower than that of the normal population [2]. Fortunately, MV repair provides patients with a similar prognosis to their overall expected prognosis [3]. Asymptomatic severe MV regurgitation with preserved left ventricular function is a challenging clinical entity as data on the recommended treatment strategy for these patients are scarce and conflicting [4, 5]. Early surgical intervention could circumvent future left ventricular dysfunction. On the other hand, a conservative strategy (watchful waiting) is based on close monitoring of the patient for clear signs of deterioration, which triggers facilitated surgery before left ventricular dysfunction develops. More than 50% of the patients in a study performed by Rosenhek et al. [6] were free of triggers for surgery after 8 years, in contrast to Enriquez-Sarano et al. [7] where >90% of patients needed surgery within 10 years. At present, no randomised clinical trials have been performed. This is reflected in current clinical guidelines: significant differences exist between European and American guidelines. According to the American (ACC/AHA) guidelines the weight of evidence is in favour of surgery in asymptomatic patients with preserved ejection fraction without atrial fibrillation or pulmonary hypertension. However, based on the same evidence, the European (ESC) guidelines are in favour of a conservative approach. The Dutch AMR trial will be the first multicenter randomised trial on this topic worldwide. Two treatment strategies are compared: early surgery versus watchful waiting. In general, randomised trials on valve surgery are relatively scarce but have had a major impact on practice and guidelines. We anticipate that the results of this study are highly needed to elucidate the best strategy and that this trial may serve as an international landmark study, thereby underpinning new recommendations for clinical guidelines. In addition to identification of the best treatment, it is of utmost importance to have knowledge on the cost-effectiveness of treatment. Obviously, surgery requires a once-only high use of health care resources. On the other hand, a lifelong intensive strategy of watchful waiting is associated with lifetime recurrent use of health care, including expensive diagnostics. If MV regurgitation is repaired successfully, patients will be followed up with low intensity and low health care costs (unless a cardiovascular event occurs). Both the reassurance of successful repair of the MV and decreased incidence of cardiovascular events after surgery contribute to the expectation that quality of life and patient outcomes are improved after surgery. We therefore expect the surgical strategy to be cost-effective in comparison with the strategy of watchful waiting.

Asymptomatic severe mitral regurgitation, current status

A computerised literature search was done in PubMed, the Cochrane library and Clinical trials.gov for “mitral valve regurgitation”. Studies were included that met the following criteria: randomised or non-randomised trials comparing different outcomes in asymptomatic with severe MV regurgitation. A total number of 529 entries were screened of which 522 could be excluded because they were case reports, not trials, reviews, or off-topic. In 7 trials the effect of surgery versus staying conservative was monitored (Table 1) [6–12]. In one of the trials there was no control group mentioned for survival [10]. The studies have different endpoints such as survival, cardiovascular survival, event-free survival and congestive heart failure, which hampers adequate comparison. Survival ranges from 50 ± 7% at 8.5 years to 91 ± 3% at 8 years, for which there are various reasons. An important limitation of all these trials is, however, that they are not randomised.

Table 1.

Overview of trials monitoring the effect of early surgery in severe MR

| Study | Study type | Centre | Analysis | N | Age | Outcomes | Outcomes with surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ling 1997 [2] | Retrospective Flail leaflets | Single | Direct comparison | 221 | 65 | Survival/CHF | 79 vs. 65% at 10 y, RR = 0.31/27 vs. 59% at 10 y, RR = 0.38 |

| Rosenhek 2006 [6] | Prospective Flail leaflet or prolapse | Single | Time dependent | 132 | 55 | Survival/Free of surgery | 91 ± 3% ns vs. expected/55 ± 6% at 8 y |

| Enriquez-Sarano 2005 [7] | Prospective Quantified MR | Single | Time dependent | 456 | 63 | Survival/CHF | RR = 0.28 (0.14–0.55)/RR = 0.37 (0.17–0.79) at 5 y |

| Kang 2009 [8] | Prospective Quantified MR | Single | Direct comparison | 447 | 50 | Event-free survival | 99 vs. 85% at 7 y |

| Grigioni 2008 [9] | Retrospective Flail leaflets | Multi-centre | Time dependent | 394 | 64 | Survival CVD/CHF | RR = 0.42 (0.21–0.84)/RR = 0.26 (0.08–0.89) at 8 y |

| Chenot 2008 [10] | Prospective Severe degenerative MR | Single | Time dependent | 143 | 63 | Overall/Cardiovascular survival | 82 ± 4%/90 ± 3% at 10 y |

| Montant 2009 [12] | Prospective Severe degenerative MR | Single | Direct comparison | 192 | 64 ± 15 conservative | Survival | 50 ± 7% vs. 86 ± 4%, at 8.5 y |

| 62 ± 12 early surgery |

Adapted from: Enriquez-Sarrano et al. Circulation 2010 [15]

Methods

We propose a pragmatic multicenter randomised trial in 250 adult asymptomatic patients with severe organic MV regurgitation and preserved left ventricular function. Patients who provide informed consent will be randomly assigned to either 1) watchful waiting; or 2) early MV repair. The follow-up will be 5 years. All procedures and definitions are in line with the current European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Guidelines.[4]

All asymptomatic patients (18–70 years) with severe organic MV regurgitation and preserved left ventricular function are eligible for the trial (Table 2.)

Table 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

| Inclusion criteria |

| Age 18–70 years |

| Severe organic mitral regurgitation |

| Absence of symptoms defined as absence of subjective limitations of exercise capacity or complaints expressed by the patient and confirmed by the cardiologist |

| Likelihood of mitral valve repair (in contrast to replacement) should be >90% |

| Patients should be fit for surgery |

| Ejection fraction >60% and left ventricular end-systolic dimension <45 mm |

| Exclusion criteria |

| Class I or IIa indication for surgery (including atrial fibrillation and pulmonary hypertension) according to the ESC guidelines [4] |

| Symptoms |

| Ejection fraction <60% and left ventricular end-systolic dimension >45 mm |

| Atrial fibrillation, either on 12-lead ECG or 48-h ECG monitoring |

| Pulmonary hypertension (RVSP >50 mmHg on echocardiography) |

| Likelihood of repair <90% |

| Physical inability to undergo surgery |

| Signs of heart failure |

| Other life-threatening morbidity |

RVSP right ventricular systolic pressure

The exclusion criteria are: class I or IIa indications for surgery (including atrial fibrillation and pulmonary hypertension) according to the ESC guidelines. Patients should be fit to undergo surgery and the likelihood of MV repair (in contrast to replacement) should be >90%.

‘Asymptomatic’ is defined as absence of subjective limitations of exercise capacity or complaints expressed by the patient and confirmed by the cardiologist.

‘Severe organic MV regurgitation’ is defined as non-ischaemic MV regurgitation with an organic cause (intrinsic valve lesion) as determined by consensus in reading echocardiography based on the criteria for definition of severe MR as issued by the ESC guidelines [4]. In practice, at least 2 of the following items should be present on echocardiography: 1) jet characteristics (>40% of left atrial surface and/or reaching pulmonary veins); 2) vena contracta width ≥0.7 cm; 3) systolic reversal of the regurgitation jet in the pulmonary veins; 4) regurgitant volume ≥60 ml/beat; 5) effective regurgitant orifice area ≥0.40 cm2; 6) E-wave dominant mitral inflow (E >1.2 m/s) in the absence of MV stenosis or other causes of an elevated left atrial pressure. We recently conducted a retrospective study in the UMC Utrecht, and found that in 138 patients with moderate or severe MV regurgitation this simple index is useful with clinically acceptable positive and negative predictive values [16].

‘Preserved left ventricular function’ is defined as left ventricular ejection fraction >60% and left ventricular end-systolic dimension <45 mm.

Patient selection

All cardiologists in the Netherlands will be asked to recruit patients for the trial (via www.dutchamr.nl and the Netherlands Society of Cardiology). They will provide written information about the trial to potential participants. They will ask patients whether they are interested in participation, and if so the referring cardiologist can contact the study centre or send the patient for a trial visit to the study centre (UMC Utrecht) to evaluate inclusion and exclusion criteria. Before inclusion, the echocardiography needs to be evaluated by the core lab and the dedicated heart team (composed of dedicated cardiologists and cardiothoracic surgeons) verifying the severity of the MV regurgitation, preserved left ventricular function, the likelihood of repair and patient operability. Furthermore, 48-h ECG monitoring must be performed and exclude paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. If no consent is given, patients will be asked if their data can be collected in a registry. At inclusion baseline measurements will be performed: health-related quality of life questionnaires, blood sampling (brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), renal function etc.), cardiopulmonary exercise testing (including peak VO2 consumption), cardiac MR (delayed enhancement, regurgitation quantification, function and dimensions). All measurements can be performed in the referring centre or in one of the study centres (on a one-stop base).

Randomisation

After both the patient and the physician have signed for informed consent, patients will be randomised stratified per hospital in a 1:1 ratio to 1) watchful waiting or 2) early MV repair surgery using a web-based computerised approach.

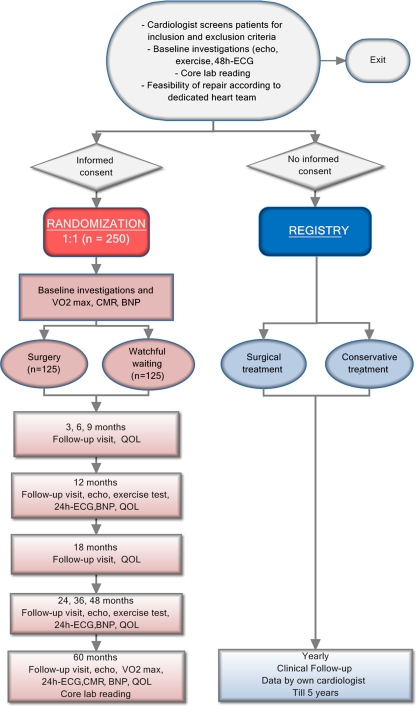

Intervention (Fig. 1, flowchart)

Fig. 1.

Study design

Watchful waiting Patients will be seen by their own cardiologist in the outpatient clinic every 6 months in concordance with the ESC guidelines. Patients who reach a class I indication for surgery according to the current ESC guidelines will be referred for surgery. For patients who reach a IIa indication for surgery it is at the treating clinicians’ discretion to refer the patient for surgery.

Surgery MV repair will be performed in centres meeting the standards for best practice regarding MV surgery: low perioperative mortality (<1%), repair rate of >95% in these patients, low reoperation rate after 5 years (<5%), >25 MV repair procedures/year/surgeon and >50/centre [13]. In principle, common daily practice and referring patterns can be followed, if they meet the aforementioned criteria and pending METC approval. Although new techniques such as the Mitraclip are very interesting, they will not be performed in this study since these techniques do not have an indication in asymptomatic patients. [14]

Follow-up by the referring cardiologist

Follow-up protocol Follow-up visits are preferred at 3, 6, 9, 12, 18, 24, 36, 48 and 60 months. Typically, the duration of follow-up in the non-randomised trials performed so far (Table 1) is 5–10 years. Therefore, we have chosen a follow-up duration of 5 years, and sample size calculation was determined accordingly. At study entry and at the follow-up visits health-related quality of life questionnaires are completed. Hospitalisations and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events are documented. Yearly standardised transthoracic echocardiography, exercise testing, 24-h ECG monitoring, and blood samples will be assessed. After 5 years cardiac MR and peak VO2 consumption are repeated.

Outcome measures The primary outcome measures all-cause mortality and a composite endpoint of cardiovascular mortality, congestive heart failure, and hospitalisation for nonfatal cardiovascular (acute coronary syndrome, atrial fibrillation) and cerebrovascular events (CVA/TIA) at 5-year follow-up. Secondary outcome measures are total direct and indirect costs, cost-effectiveness, health-related quality of life, echocardiographic and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) parameters (left ventricular function, left atrial dimensions, pulmonary hypertension), exercise test, asymptomatic atrial fibrillation, and BNP levels. Additionally, the complication rate in the surgery group (e.g. reoperation for bleeding, pneumonia, residual or recurrent mitral valve regurgitation) and rate of surgery in the watchful waiting group will be determined.

Sample size calculation The expected 5-year event rate is 38%, which is the median of the published literature, and involves the composite of cardiac death, heart failure and hospitalisation for atrial fibrillation [7–9]. From results of non-randomised studies, we make a conservative estimate for the relative reduction in risk due to surgical repair as being 45%, thus reducing the absolute risk of events down to 21%. With a two-sided alpha, and 80% power, we need to randomise 123 patients in each treatment arm. Given the uncertainty around the reported event rates in the literature, the sample size assumptions will be monitored by the Data Safety and Monitoring Board at regular intervals. The sample size may be adjusted when deemed appropriate.

Feasibility of recruitment Based on the UMC Utrecht and Leiden UMC surgical database, we think that 15–20 patients per year will meet the inclusion criteria per surgical centre (of which there are 16 in the Netherlands). Participation of the Interuniversity Cardiology Institute of the Netherlands (ICIN) will hopefully ensure participation of the majority of academic cardiologists. Furthermore, we performed a survey among cardiologists at non-academic centres, showing that every single cardiologist has at least a few patients in their practice who will meet the Dutch AMR trial inclusion criteria but who have not yet been referred to a surgical centre. Participation of the WCN (Dutch Network for Cardiovascular Research) and its extensive network of non-academic cardiology centres ensures the mobilisation of suitable candidate patients. Therefore, we anticipate that at least 200 patients per year can be screened for inclusion. If 50% enter the study, we will need 2–3 years to include patients in the Dutch AMR trial. It is important to reach all cardiologists in the Netherlands via the Dutch AMR website and the Netherlands Society of Cardiology. To ensure participation the referring cardiologist can choose to refer the patient to the cardiologist at the research centre or to just get assistance by telephone or email contact.

Data analysis The effects of watchful waiting and early MV (repair) surgery will be calculated as risk differences and rate ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Kaplan-Meier curves for survival, congestive heart failure and hospitalisation for non-fatal cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events in both groups will be plotted, and differences tested with a log-rank test. The EuroQol-5D and ShortForm-36 will be used to assess quality of life. All patients will be asked to fill out these questionnaires, at baseline and during all scheduled follow-up moments, to assess possible differences in quality of life and quality adjusted life year (QALYs) between groups. Health-related quality of life instrument scores will be transformed linearly onto scales of 0 to 100, and analysed with analysis of the variance (ANOVA). Percentage differences with 95% confidence intervals will be calculated for echocardiographic and CMR parameters, blood sampling findings and exercise testing data. The complication rate in the surgery group and rate of surgery in the watchful waiting group will be determined. All analyses will be performed on an intention-to-treat basis. As a result of the randomisation procedure no baseline differences between the two groups are expected.

Economic evaluation As this is the first clinical trial to study outcomes of surgery versus watchful waiting for asymptomatic patients with MV regurgitation, there will be an emphasis on economic aspects. The clinical study focuses on the effectiveness of the intervention on primary outcome measures (cardiovascular mortality, congestive heart failure, non-fatal cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events). Also the associated impact in terms of costs and quality of life will be estimated. The balance between costs and effects of the surgical approach will be compared with that of the conventional care approach. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio will be calculated in terms of costs per event avoided, costs per life year gained and costs per QALY gained. The cost-effectiveness and cost-utility analysis will be based on data collected alongside the clinical trial. Economic evaluation will be performed from a societal perspective including total direct health care costs and indirect non-health care costs (productivity losses). Overall costs will be compared across the randomisation groups, and where relevant, differences will be calculated, inclusive of 95% confidence intervals.

Time schedule: April 2012–April 2020

Study organisation The ICIN will take care of all financial and logistic manners. The practical and scientific execution of the study is under the responsibility of the coordinating centre (UMC Utrecht) and the steering committee. A Data Safety and Monitoring Board (DSMB) (four members, including a statistician) will be installed to evaluate the safety of the interventions. The precise stopping rules (early efficacy and harm) will be developed by the DSMB. A DSMB charter is currently being prepared by Prof. Dr. J.G.P. Tijssen.

Event committee Follow-up of patients will be up to 5 years after randomisation. During trial visits, the research nurse/investigator evaluates drug use, quality of life, cardiovascular and other serious adverse events. The serious adverse events, cardiovascular events and mortality will be evaluated in detail (clinical documentation) by the Event Adjudication Committee. As monitoring of the data is mandatory by Dutch law in a trial like this, an established independent Clinical Research Office (CRO) will be responsible for that aspect. The level of monitoring will be established by the investigators in collaboration with the Ethics Review Committee.

Steering committee Dr. J. Kluin (principle investigator, cardiothoracic surgeon), Dr. S.A.J. Chamuleau (principle investigator, cardiologist), Prof. Dr. R.J.M. Klautz (cardiothoracic surgeon), Dr. R.B.A. van den Brink (cardiologist), Prof. Dr. L.A. van Herwerden (cardiothoracic surgeon), Prof. Dr. W. van Gilst (cardiologist), Prof. Dr. P.D. Doevendans (cardiologist), Prof. Dr. M.J. Schalij (cardiologist), Prof. Dr. M.L. Bots (epidemiologist), Dr. M.J.W. van Hessen (cardiologist). Data Safety and Monitoring Board: Prof. Dr. J.G.P. Tijssen (statistician), Dr. A.P. Kappetein (cardiothoracic surgeon), Prof. Dr. E.E. van der Wall (cardiologist, director ICIN), and Dr. A.M.W. Alings (cardiologist) (Table 3). A Clinicaltrials.gov identifier will be applied for.

Table 3.

Study organisation

| ICIN (Interuniversity Cardiology Institute of the Netherlands) | Logistic and financial manners |

|---|---|

| DSMB (Data Safety and Monitoring Board) | Prof. Dr. J.G.P. Tijssen (statistician), Dr. A.P. Kappetein (cardiothoracic surgeon), Prof. Dr. E.E. van der Wall (cardiologist), Dr. A.M.W. Alings, (cardiologist) |

| Steering committee | Dr. J. Kluin, (principle investigator, cardiothoracic surgeon) |

| Dr. S.A.J. Chamuleau (principle investigator, cardiologist) | |

| Prof. Dr. R.J.M. Klautz (cardiothoracic surgeon) | |

| Dr. R.B.A. van den Brink (cardiologist) | |

| Prof. Dr. L.A. van Herwerden (cardiothoracic surgeon) | |

| Prof. W. van Gilst (cardiologist) | |

| Prof. Dr. P.A. Doevendans (cardiologist) | |

| Prof. Dr. M. Schalij (cardiologist) | |

| Prof. Dr. M.L. Bots (epidemiologist) | |

| Dr. M.J.W. van Hessen (cardiologist) |

Discussion

The current study design was drafted to investigate the best treatment option for asymptomatic patients with severe MV regurgitation. Although at present the general consensus is increasingly favouring early MV repair, selection bias is a big problematic confounder in the non-randomised trials that have been performed. MV repair has proven to have excellent results. There is, however, a large debate about success rate. It is not clear if every thoracic surgery department can prove that they meet the standard for MV repair. [13]. If an MV repair fails, and a MV prosthesis is implanted, the overall outcome of this patient group has proven to be associated with worse outcome [2]. It will be very interesting to carefully examine the new percutaneous treatment options for MV regurgitation. However, at present there is no indication for percutaneous repair in asymptomatic patients [14]. We anticipate that the various medical ethics committees will not allow the off-label use of percutaneous repair. Maybe in the near-future this treatment option could also be examined. Our proposed trial has been designed to incorporate best common practice as is standard in most parts of the Netherlands. This will ensure the enrolment of a relatively high number of patients. An important ‘side effect’ of this Dutch AMR trial is the close collaboration of the Dutch network of cardiologists and cardiothoracic surgeons, which will facilitate the conduct of nationwide intervention studies into area of clinical practice where unknowns in terms of efficacy, side effects, and the balance between costs and effects can be evaluated in the future.

Implications

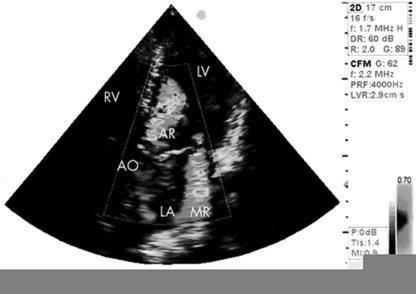

The Dutch AMR trial will be the first multicenter randomised trial on this topic. Two treatment strategies are to be compared: early surgery versus watchful waiting. In general, randomised trials of valve surgery are relatively scarce but have had a major impact on practice and guidelines. We anticipate that the results of this study are highly needed to elucidate the best strategy and that this trial will serve as an international landmark study, thereby underpinning new recommendations for clinical guidelines at Level B evidence. We encourage cardiologists in the Netherlands to include patients with asymptomatic severe mitral regurgitation (Fig. 2) in this study. On a website we will provide extra information and backgrounds.

Fig. 2.

Echocardiography of severe organic mitral regurgitation. AO = aorta, AR = aortic regurgitation, LA = left atrium, LV = left ventricle, MR = mitral regurgitation, RV = right ventricle

Footnotes

W. J. Tietge and L. M. de Heer contributed equally to this manuscript.

References

- 1.Lung B, Baron G, Butchart EG. A prospective survey of patients with valvular heart disease in Europe: the Euro heart survey on valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:1231–1243. doi: 10.1016/S0195-668X(03)96147-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ling LH, Enriquez-Sarano M, Seward JB, et al. Clinical outcome of mitral regurgitation due to flail leaflet. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1417–1423. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199611073351902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suri RM, Schaff HV, Dearani JA, et al. Recurrent mitral regurgitation after repair: should the mitral valve be re-repaired? J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;132:1390–1397. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vahanian A, Baumgartner H, Bax J, et al. Guidelines on the management of valvular heart disease: the Task Force on the Management of Valvular Heart Disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(2):230–268. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Kanu C, et al. ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease) Circulation. 2006;114:e84–e231. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.176857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenhek R, Rader F, Klaar U, et al. Outcome of watchful waiting in asymptomatic severe mitral regurgitation. Circulation. 2006;113(18):2238–2244. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.599175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enriquez-Sarano M, Avierinos JF, Messika-Zeitoun D, et al. Quantitative determinants of the outcome of asymptomatic mitral regurgitation. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:875–883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang DH, Kim JH, Rim JH, et al. Comparison of early surgery versus conventional treatment in asymptomatic severe mitral regurgitation. Circulation. 2009;119(6):797–804. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.802314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grigioni F, Tribouilloy C, Avierinos JF, et al. Outcomes in mitral regurgitation due to flail leaflets a multicenter European study. JACC Cardiovasc Imag. 2008;1(2):133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chenot F, Montant P, Vancraeynest D, et al. Long-term clinical outcome of mitral valve repair in asymptomatic severe mitral regurgitation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2009;36(3):539–545. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2009.02.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ling LH, Enriquez-Sarano M, Seward JB, et al. Early surgery in patients with mitral regurgitation due to flail leaflets a long-term outcome study. Circulation. 1997;96(6):1819–1825. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.96.6.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montant P, Chenot F, Robert A, et al. Long-term survival in asymptomatic patients with severe degenerative mitral regurgitation: a propensity score-based comparison between an early surgical strategy and a conservative treatment approach. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;138(6):1339–1348. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2009.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bridgewater B, Hooper T, Munsch C, et al. Mitral repair best practice: proposed standards. Heart. 2006;92(7):939–944. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2005.076109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feldman T, Kar S, Rinaldi M, et al. Percutaneous mitral valve repair with the MitraClip system. JACC. 2009;54:686–692. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.03.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Enriquez-Sarano M, Sundt T. Early surgery is recommended for mitral regurgitation. Circulation. 2010;121:804–812. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.868083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jansen R, Tietge W, Sijbrandij K, et al. Practical echocardiographic semi-quantitative scoring system to determine severity of mitral regurgitation. Poster Presentation Euroecho. 2011.