Abstract

Background

Many patients who should be treated for depression are missed without effective routine screening in primary care (PC) settings. Yearly depression screening by PC staff is mandated in the VA, yet little is known about the expected yield from such screening when administered on a practice-wide basis.

Objective

We characterized the yield of practice-based screening in diverse PC settings, as well as the care needs of those assessed as having depression.

Design

Baseline enrollees in a group randomized trial of implementation of collaborative care for depression.

Participants

Randomly sampled patients with a scheduled PC appointment in ten VA primary care clinics spanning five states.

Measurements

PHQ-2 screening followed by the full PHQ-9 for screen positives, with standardized sociodemographic and health status questions.

Results

Practice-based screening of 10,929 patients yielded 20.1% positive screens, 60% of whom were assessed as having probable major depression based on the PHQ-9 (11.8% of all screens) (n = 1,313). In total, 761 patients with probable major depression completed the baseline assessment. Comorbid mental illnesses (e.g., anxiety, PTSD) were highly prevalent. Medical comorbidities were substantial, including chronic lung disease, pneumonia, diabetes, heart attack, heart failure, cancer and stroke. Nearly one-third of the depressed PC patients reported recent suicidal ideation (based on the PHQ-9). Sexual dysfunction was also common (73.3%), being both longstanding (95.1% with onset >6 months) and frequently undiscussed and untreated (46.7% discussed with any health care provider in past 6 months).

Conclusions

Practice-wide survey-based depression screening yielded more than twice the positive-screen rate demonstrated through chart-based VA performance measures. The substantial level of comorbid physical and mental illness among PC patients precludes solo management by either PC or mental health (MH) specialists. PC practice- and provider-level guideline adherence is problematic without systems-level solutions supporting adequate MH assessment, PC treatment and, when needed, appropriate MH referral.

Keywords: depression, screening, primary care, health care delivery, veterans

INTRODUCTION

Nationally, depression affects between 16–20 million Americans and remains a major public health problem.1 Despite its prevalence, depression often remains undetected, under-diagnosed and under-treated.2–4 Many depressed patients only contact the healthcare system through primary care (PC).4 Fortunately, more efficient procedures for screening for and diagnosing depression and the advent of better-tolerated antidepressants that are safer and easier to prescribe (i.e., less complex dosing regimens) have increased PC providers’ ability to manage mild to moderate depression.5 Nonetheless, PC-based detection and treatment remain low.6 Despite US Preventive Task Force recommendations for practice-based screening of all PC patients, just 21% report actually being screened.7,8 Thus, many patients who should be in treatment are missed without effective routine screening, while screening also reveals that many patients who are in treatment are still symptomatic.8

Despite treatment advances and widespread acknowledgment of the value of PC-based management of depression, little is known about the potential yield of depression screening guidelines in routine practice settings. What proportion of PC patients actually screen positive and are assessed as having depression? What are depressed PC patients’ physical and mental health care needs? What are the implications of these rates and health care needs for practicing PC providers?

Using practice-wide, population-based screening and assessment, we randomly sampled PC patients from ten diverse primary care settings from a large multisite randomized trial to discern answers to these questions.

METHODS

Setting

We engaged ten PC clinics in three VA regional networks across five states (Florida, Ohio, South Dakota, Texas, Wisconsin). Participating clinics spanned rural and metropolitan areas, hospital- and community-based outpatient clinics, and teaching and non-teaching programs. Practices ranged in size from 4–13 PC providers and in annual workloads from 3,900-13,000 patients.9 Institutional Review Boards at participating VA facilities approved the study.

Study Design and Sample

To characterize the yield of depression screening in routine practice, we used the baseline cohort of patients enrolled in a group randomized controlled trial evaluating practice-level impacts of implementation of collaborative care for depression from 2002–2004.10,11 All PC patients who attended a study clinic in the previous 12 months and who had an upcoming appointment were eligible for inclusion regardless of age, gender, race-ethnicity or health status, as depression screening guidelines make no demographic or comorbidity distinctions. We excluded patients whose visits were scheduled for compensation-and-pension exams (i.e., eligibility determination) or for visits without seeing the PC provider (e.g., laboratory tests).

Data Collection and Patient Survey Measures

Participating sites provided contact information for random samples of eligible PC patients to an independent survey research firm (California Survey Research Services, Inc., Van Nuys, CA). Patients were notified of the study by mail 10 days prior to telephone contact using letters from their respective Primary Care Directors or Chiefs of Staff. We included preaddressed refusal postcards and a toll-free number for patients to call for refusal. After 10 days, trained interviewers contacted patients via computer-assisted telephone interviewing (CATI).

We screened patients for depression using the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2), a two-item depression screener with high sensitivity and specificity for major depressive disorder (MDD).12–16 Major depressive disorder (MDD) is characterized by a “combination of symptoms that interfere with a person’s ability to work, sleep, study, eat, and enjoy once-pleasurable activities.”17 We administered the remaining seven items of the PHQ-9, which cover additional DSM-IV criteria for a major depressive episode, to patients with affirmative responses to one or both PHQ-2 items. The PHQ-9 has high specificity and positive predictive value for MDD, and has been validated for telephone administration.18,19 Individuals with aggregated PHQ-9 scores ≥10 were considered to have probable major depression, and were then consented, enrolled and interviewed. All measures are based on patient self-report.

We asked about patients’ demographics (age, gender, race, ethnicity, relationship status), socioeconomic status (employment, education, insurance), general health, functional limitations20,21 and medical comorbidity.22 We assessed mental health (MH) comorbidities, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), bipolar disorder, anxiety/panic and alcohol abuse,23–26 and depression modifiers (e.g., dysthymia). Tables 1 and 2 provide measurement definitions and details.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Depressed Primary Care Patients with Probable Major Depression (PHQ-9 ≥10) Identified through VA Primary Care Practice-Based Screening

| Characteristics | Depressed primary care patients (n = 761) |

|---|---|

| Gender (% male) | 94.0% |

| Age (mean ± SD) (years) | 60.4 ± 11.9 years |

| Race (% white) | 85.0% |

| Marital status | |

| Married or living as married | 60.1% |

| Divorced or separated | 26.1% |

| Widowed | 7.5% |

| Never married | 6.3% |

| Work Situation | |

| Working full/part time for pay | 17.0% |

| Unemployed | 9.3% |

| On disability | 41.2% |

| Semi-retired | 4.7% |

| Permanently retired | 25.0% |

| Homemaker/student/volunteer | 1.5% |

| Other | 1.3% |

| Highest level of schooling | |

| Elementary or junior high school | 10.2% |

| High school (or GED) | 39.2% |

| Associate or vocational school | 12.5% |

| Some college | 25.9% |

| College degree | 5.7% |

| Some postgraduate work or degree | 6.5% |

| Insurance status and reliance on VA | |

| Have any insurance to cover costs of medical care | 63.5% |

| Health care utilization | |

| Received care at VA for physical or emotional problems in past 6 months | 90.4% |

| General health status | |

| Excellent | 1.4% |

| Very good | 3.3% |

| Good | 14.9% |

| Fair | 35.7% |

| Poor | 44.7% |

| Depression symptomatology* (% several days, more than half the days or nearly everday in the past 2 weeks) (first two items, PHQ-2; full item set, PHQ-9) | |

| Over the last 2 weeks, how often have you been bothered by: | |

| Feeling little interest or pleasure in doing things | 95.3% |

| Feeling down, depressed or hopeless | 97.3% |

| Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much | 87.8% |

| Feeling tired or having little energy | 98.6% |

| Poor appetite or overeating | 78.5% |

| Feeling bad about yourself, or feeling that you are a failure or have let yourself or your family down | 77.2% |

| Trouble concentrating on things, such as reading the newspaper or watching television | 78.0% |

| Moving or speaking so slowly that other people could have noticed. Or the opposite—being so fidgety or restless that you have been moving around a lot more than usual | 66.5% |

| Thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way | 32.4% |

| Suicidality protocol completed† | 31.0% |

*Depression symptomatology was measured using the PHQ-9.18 The PHQ-2 (two-item screener) asks about frequency of anhedonia (i.e., feeling little interest…) and depressed mood (i.e., feeling down, depressed, hopeless). The remaining seven items comprise the rest of the PHQ-9, which uses the same 4-point scale (not at all, several days, more than half the days, nearly everyday) regarding the past 2 weeks. Higher scores reflect worse symptomatology. PHQ-9 aggregated scores ≥10 reflect probable major depression. Major depressive disorder (MDD) is characterized by a “combination of symptoms that interfere with a person’s ability to work, sleep, study, eat, and enjoy once-pleasurable activities”

†We developed a suicidality protocol, which was triggered among patients who responded to the ninth item of the PHQ-9 on suicidal ideation: “How often have you been bothered by thoughts that you would be better off dead or of hurting yourself in some way?” with answers of “several days,” “more than half the days” or “nearly every day,” and/or divulged thoughts of suicide, self-harm, persistent thoughts of death or harm to others during the course of the interview. Details of the suicide protocol are available elsewhere.12(Note: Thirty patients were identified as acutely suicidal during the baseline interview, were connected with mental health services and excluded from the study)10

Table 2.

Physical and Mental Health Comorbidities among Patients with Probable Major Depression (PHQ-9 ≥10) Identified Through VA Primary Care Practice-Based Screening

| Characteristics | Depressed primary care patients (n = 761) |

|---|---|

| Medical comorbidity* | |

| Has a doctor or nurse ever told you that you had any of the following health problems? | |

| Cancer | 17.7% |

| Pneumonia | 36.3% |

| Heart attack | 28.2% |

| Chronic lung disease, emphysema, asthma or bronchitis | 36.9% |

| Diabetes | 34.7% |

| Stroke | 15.3% |

| Congestive heart failure | 18.1% |

| Current smoker | 48.9% |

| Seattle Index of Comorbidity (SIC)* | 7.06 ± 3.32 |

| Mental health comorbidity | |

| Possible dysthymia and chronic major depression† | |

| Have you ever had a period of 2 years or more in your life when you felt depressed or sad most days, even if you felt OK sometimes? | 72.8% |

| Of those who said yes, Did any period like that ever last 2 years without an interruption of 2 full months when you felt OK? | 50.4% |

| In the past 12 months, have you had 2 weeks or longer when: | |

| Nearly every day you felt sad, empty or depressed for most of the day | 69.5% |

| You lost interest in most things like work, hobbies and other things you usually enjoyed | 77.7% |

| Your emotional state seriously interfered with your ability to do your job, take care of your house or family, or take care of yourself | 56.5% |

| Alcohol consumption‡ | |

| Last time drank alcohol: | |

| Past 2 weeks | 29.2% |

| Between 2 weeks and 1 year ago | 17.2% |

| 1 or more years ago | 49.0% |

| Never drank | 4.9% |

| Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) score25,26 (mean ± SD) | 2.0 ± 3.1 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)§ | |

| Reexperiencing: Ever had any experience in your life that was so frightening, horrible or upsetting that you had recurring nightmares about it or continually thought about it when you did not want to | 69.4% |

| Of those who said yes, proportion that had had these thoughts or nightmares in the past month | 64.8% |

| Avoidance: Had any experiences that were so frightening, horrible or upsetting that you repeatedly tried hard not to think about it or repeatedly went out of your way to avoid situations that reminded you of it | 65.3% |

| Of those who said yes, proportion that tried to avoid these situations in the past month | 74.1% |

| Hypervigilance: Ever had a period where you felt constantly on guard, watchful or easily startled because of a frightening, horrible or upsetting experience | 57.1% |

| Of those who said yes, proportion that had this feeling of watchfulness in the past month | 75.3% |

| Emotional numbing: Ever had a period where you felt numb or detached from other people, activities or from your surroundings because of a frightening, horrible or upsetting experience | 53.0% |

| Of those who said yes, proportion with feeling of detachment in past month | 77.1% |

| Bipolar disorder║ | |

| Doctor told you had a manic-depressive or bipolar illness | 20.6% |

| Ever taken medications lithium, Depakote, or Tegretol for a depressive illness | 17.6% |

| Anxiety | |

| Felt anxious much of the time (past 6 months) | 63.9% |

| Had panic attack when suddenly felt intense fear and discomfort (past 6 months) | 42.6% |

| Of those who said yes, had a month or more when they changed everyday activities because of fear of having another panic attack | 52.8% |

| Panic attack within the past month | 60.9% |

| Physical and mental function¶ | |

| In past 4 weeks, all or most of the time: | |

| Accomplished less than you would have liked because of physical health | 63.6% |

| Limited in kinds of work or other activities that you were able to do because of physical health | 62.5% |

| Cut down the amount of time you spent on work or other activities because of emotional problems | 43.4% |

| Accomplished less than you would have liked because of emotional problems | 55.6% |

| Did work or other activities less carefully than usual because of emotional problems | 30.6% |

| Physical or emotional problems interfered with your social activities (like visiting friends, relatives, etc.) | 52.9% |

| Pain interfered with normal work (including both work outside the home and housework) quite a bit-to-extremely | 54.2% |

| Frequency of feeling (all-to-most of the time): | 36.8% |

| Very nervous | 31.9% |

| Felt so down in the dumps that nothing could cheer you up | 12.7% |

| Felt calm and peaceful | 45.0% |

| Felt downhearted and depressed | 14.6% |

| Been happy | 3.8% |

| Had a lot of energy | |

| Satisfaction with level of daily activity (dissatisfied-to- very dissatisfied) | 69.2% |

| Sexual function | |

| Current difficulty with how you function sexually or with your sexual activity | 73.3% |

| Among those with difficulty, difficulty first started more than 6 months ago | 95.1% |

| Among those with difficulty, difficulty bothers you moderately to very much | 81.4% |

| Among those with difficulty, ever discussed difficulty with any health care provider within past 6 months in person or by phone | 46.7% |

*We measured medical comorbidities using the Seattle Index of Comorbidity (SIC), which combines the presence or absence of seven chronic illnesses (listed above), cigarette smoking status and participant age into an aggregated index. The SIC has been shown to predict hospitalization and mortality21

†Dysthymia is characterized by long-term depressive symptoms (2+ years) that is typically less severe than major depressive disorder (MDD) but may still prevent aspects of normal function or well-being; dysthymics may also have 1+ episodes of major depression over their lifetimes17

‡We used the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test consumption items (AUDIT-C) to evaluate alcohol consumption. Summed scores result in an index where higher scores reflect higher consumption, which predicts poor alcohol-related outcomes, while scores greater than 8 are associated with mortality among male veteran VA outpatients65

§We used the Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD) to detect probable PTSD in primary care. The PC-PTSD may be used to generate a summary score (0 to 4) for the presence of each of four PTSD symptoms (reexperiencing, avoidance, hypervigilance and emotional numbing related to past trauma), where scores of 3 and 4 represent positive PTSD screens23

║We used positive responses to two questions (noted above) to identify probable bipolar disorder.24 The medications mentioned (e.g., lithium) may be used as mood stabilizers for bipolar disorder

¶We drew items from the Short-Form 12 Survey (SF-12) of the Medical Outcomes Study’s Short Form 36-item survey to assess functional limitations related to physical and emotional health concerns, including pain20,21

Statistical Analysis

We used univariate analyses to describe the yield of depression screening and assessment and the self-reported health status, medical and MH comorbidities and function of PC patients with probable major depression (PHQ-9 ≥10). CATI methods resulted in little missing data, precluding the need for data imputation methods (i.e., the majority of variables had 99% valid data, with the exception of sexual dysfunction with 11% missing). We report unadjusted frequencies; use of enrollment weights (by age, sex, race-ethnicity) did not influence study results.

RESULTS

Practice-Based Sample Characteristics and Response Rates

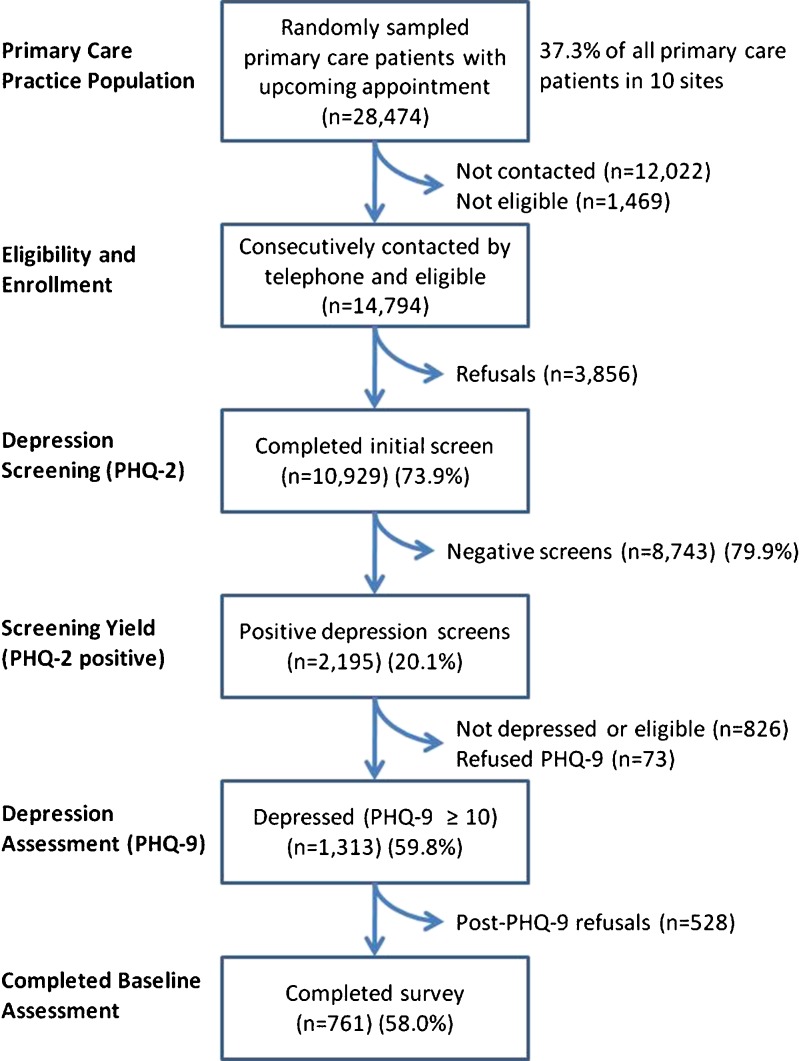

Overall, we received contact information on 28,474 randomly sampled patients with upcoming PC appointments who had had at least one visit in the previous 12 months (Fig. 1). These individuals were predominantly male (95.1%) with a mean age of 66.6 years (±12.4, range 21–105). Of those contacted, 10,929 completed the initial screen (73.9%). Of those assessed (PHQ-9 ≥ 10), 761 (58.0%) enrolled and completed the baseline survey.

Figure 1.

Yield of depression screening in practice-based random sample of primary care clinic visitors

Prevalence of Depression and Patient Characteristics

Practice-based screening of 10,929 PC patients yielded 20.1% positive PHQ-2 depression screens (n = 2,195, including positive screens among 73 refusals post-consent-and-screen) across the ten participating PC clinics (Fig. 1). Among PHQ-2 positive screens, 59.8% (n = 1,313) scored 10 or higher on the PHQ-9 (11.8% of all screens) and were deemed to have probable major depression.27 Of these patients, 761 (58.0%) enrolled in the study, completed the baseline assessment and are the focus of these results. These depressed PC patients (PHQ-9 ≥10) were, on average, 60 years old, male, predominantly white and married, with a high school or college education (Table 1). Two-thirds were either disabled or permanently retired. Few lived alone.

We found substantial evidence of dysthymia and chronic major depression (Table 2). For example, 72.8% of depressed veterans in PC reported experiencing at least one period of 2+ years when they felt depressed or sad most days. Over two-thirds reported a period of 2+ weeks of feeling sad, empty or depressed most of the day nearly every day in the past 12 months. About three-quarters of the patients reported experiencing a similar amount of time suffering anhedonia (i.e., lost interest in work, hobbies and other previously enjoyed activities). Over half reported that their emotional state conferred serious functional impairment in their ability to work and/or take care of themselves or their families for 2+ weeks in the past 12 months. Nearly one-third reported experiencing thoughts of suicide several days out of the previous 2 weeks.

Medical and Mental Health Comorbidities among Depressed Primary Care Patients

Medical and MH comorbidities were substantial (Table 2).

Medical comorbidities

Over one-third of depressed PC patients reported histories of chronic lung disease, pneumonia and diabetes, and about one-quarter reported a history of heart attack. Roughly one in six reported congestive heart failure or a history of cancer or stroke. Eighty percent of patients described their general health as fair or poor. Their prior month’s medication volume (6.9 ± 5.5) corroborated their self-reported physical health.

PTSD

Over two-thirds of the sample reported lifetime posttraumatic reexperiencing phenomena (i.e., recurrent nightmares/intrusive thoughts) related to a past traumatic event, with two-thirds of those reporting these experiences in the past month. Similarly, about two-thirds reported posttraumatic avoidance of thoughts or cues related to past traumatic events; about half of these patients reported avoidance behavior in the past month. Nearly 60% reported a period of hypervigilance, with over 40% reporting these experiences in the past month. Slightly over half experienced emotional numbing or a sense of detachment from other people, activities or surroundings, many of whom reported that this symptom had occurred in the past month.

Bipolar disorder

About one in five of the depressed patients in VA PC clinics reported being told they had bipolar disorder by a doctor, with a roughly equivalent and overlapping percentage reporting having taken medications suggestive of bipolar disorder (e.g., lithium).

Anxiety

Nearly two-thirds reported feelings of persistent anxiety in the previous 6 months. Just over 40% reported having experienced a panic attack with sudden intense fear and discomfort, over half of whom reported a month or more during which anticipation of possible future panic attacks changed their daily activities. One quarter of participants reported one or more panic attacks in the past month.

Alcohol consumption

Nearly half of these depressed patients reported drinking in the past year, with one in five reporting drinking approximately 1–2 drinks daily. Almost half of those who reported using alcohol reported occasional-to-daily levels of toxic drinking (i.e., 6+ drinks on one occasion for men, 4+ for women).

MH-related medication use

Over half (55.1%) had been prescribed 1+ medications specifically for their mental or emotional problems. Over a third of patients said their depression medications, specifically, were “a little” to “not at all helpful.”

Physical and Mental Health Function among Depressed Primary Care Patients

Physical and MH functional limitations were common (Table 2). For example, nearly two-thirds of depressed PC patients reported accomplishing less than desired in the past 4 weeks, and limitations in the kinds of work or other activities they were able to do. When asked about limitations related to emotional problems (i.e., feeling depressed or anxious), over half reported accomplishing less than desired, and over 40% reported reduced time spent on work or other activities as a result of emotional problems. Similarly, over half reported that their physical or emotional problems interfered with their social activities (e.g., visiting friends). Pain was also reportedly responsible for significant interference with work (in and outside the home). Sexual dysfunction was common and longstanding, with nearly half of patients with sexual dysfunction reporting that it was neither discussed with medical providers nor treated.

DISCUSSION

We found that practice-wide depression screening yielded about 20% positive PHQ-2 screens among veterans seen in primary care (PC) and 12% probable major depression (or nearly 60% of positive PHQ-2 screens). Among depressed patients in VA PC settings, we noted highly prevalent comorbid mental illness (e.g., anxiety, PTSD) and substantial chronic disease burden.

Overall, veteran PC patients’ rates of depression are higher than those of their civilian counterparts. Nationally, about 6.6% of Americans are depressed in any given year (with a lifetime prevalence of 16.2%).28 These differences may reflect veterans’ service-connected disabilities that ensure their entrée to VA health care and may place them at higher risk of depressive symptoms. VA users also have 1–2 more chronic diseases than same-age, same-gender, same race-ethnicity civilians, and chronic disease burden has been linked to greater depression symptomatology.29,30 Rates of depression screening and diagnosis in the VA have also continued to increase since the VA mandated annual depression screening in 1998.31

The 20% positive-screen rate from practice-based screening is substantially higher than most previously reported VA rates. For example, VA performance measures, which rely on chart reviews of random samples of clinic visitors to determine annual screening yields, reflected 8.8% positive screens in the same year our cohort enrollment began,32 while chart reviews of consecutive PC patients at a single VA yielded 7%.33 Chart-based assessment of the yield of depression screening among four other VA clinics also demonstrated a 7% positive-screen rate, even when veterans already in mental health or substance abuse treatment were excluded.34 Our use of patient self-report is likely the key distinction, as our positive-screen rate is consistent with another survey-based assessment of VA screening yield (also 20%) in a single site.16 Our findings point to the importance of systematic, practice-based screening—as recommended by the VA/DoD clinical practice guidelines for depression—to not only identify new cases but to identify patients for whom treatment has been ineffective, who are no longer engaged in treatment or who have relapsed, regardless of whether they have been previously identified.35

The severity of these veterans’ depression was substantial. We found evidence of significant chronicity and personal and occupational impairment. Further, while suicide and suicidal ideation are common symptoms of depression, and mood disorders confer increased risk of suicide,36,37 we did not anticipate the level of suicidal ideation (over 30%) among routine PC clinic visitors even in the VA. However, other studies have noted comparable levels in non-VA settings (using the PHQ-9).38,39 In recognition of higher rates of suicidality among veterans in general, the VA has made suicide prevention a top priority, instituting a national crisis hotline, confidential online chats, outreach and local suicide prevention coordinators. The crisis line has answered more than 400,000 calls and made more than 14,000 lifesaving rescues.40 Ensuring that PC providers have the training and organizational support they need to address the severity of their patients’ depression is essential, while our results have important implications for PC practices outside the VA system.41

We also found considerable medical and mental health comorbidities among depressed patients in VA PC settings, rendering most guideline adherence strategies relatively moot in the face of these patients’ complex needs. Two-thirds reported comorbid PTSD or symptoms of generalized anxiety or panic disorders, while a significant proportion reported dangerous levels of alcohol consumption. Current guidelines do not address how PC providers ought to assess tradeoffs in how they manage, medicate and/or refer their patients with competing chronic illnesses, both physical and mental health-related.42 Given the mental health comorbidities common to PC patients with depression, solo management by PC providers is unlikely to be effective without organizational or system supports that foster integrating mental health specialty input in some efficient way. Even in settings where mental health capacity is reasonably high, patient preferences (including concerns about stigma) and barriers to effective handoffs preclude a mental health-only solution.43 Instead, collaborative care models have demonstrated the value of shared care, where PC providers are supported in the mental health care of their patients through depression care managers who are supervised by mental health providers.44,45 In the absence of such care models, evidence suggests that depression remains persistent.46

Over one third of the patients who reported being prescribed one or more mental health-related medications reported they were of limited to no benefit. In the absence of improved medication management, most patients commonly undergo only a single trial of antidepressants, resulting in insurers and health care systems bearing the substantial costs of initiating inadequate depression treatment.47 Systems cost-effectiveness also demonstrates the value of the acute phase of depression treatment.48 As health plans, health care systems, clinics and providers increasingly adopt depression screening guidelines, it will be essential that systems are simultaneously put into place to ensure adequate monitoring of symptoms between and during visits, to support effective medication management and improved outcomes for depression patients in PC settings.49

Although the design of this study does not permit definitive differential psychiatric diagnoses, the potential comorbid mental health conditions are likely to increase the difficulty of treating depression to remission.50,51 The prevalence of comorbid PTSD and anxiety, on top of one-third having substantial medical comorbidities such as diabetes, likely obviates the value and effectiveness of a traditional 15–20-min medical appointment. This level of comorbidity is not unique to the VA. Most lifetime (72.1%) and 12-month (78.5%) cases of depression have at least one comorbid CIDI/DSM-IV disorder, with major depressive disorder (MDD) only rarely being primary.52 Interestingly, there is little empirical evidence that these types of complexities reduce the propensity of PC physicians to diagnose mental health problems, though depressed patients with comorbid anxiety have longer visit durations, greater depression severity and are more likely to be diagnosed.53–55

What is also clear from this work is that PTSD is virtually a hidden diagnosis in primary care. Previous studies have not usually reported PTSD prevalence among depressed PC patients. Primary care is operating as the “de facto mental health care system…”56 It is essential that PC providers be trained to screen their patients for PTSD symptoms, as these patients tend to present with somatic complaints or depression alone, and may avoid discussion of their traumatic experiences.57

This study is not without limitations. Our data represent the population of clinic users with probable major depression within the VA. Its generalizability to the general population may therefore be limited, although rates of depression among Americans may be an underestimate due in part to the relative lack of access to mental health care outside the VA. Most comparative literature also derives from chart reviews rather than telephone-based patient self-report, which is itself not a common clinical practice and could affect responses. While trained interviewers were used, they may elicit different responses compared to clinic staff. We also do not have comparison data for veterans with negative screens, though another study reported such comparisons, and found no sociodemographic or comorbidity differences.32 We also did not exclude those already in treatment, which increased our detection rate as both undiagnosed and diagnosed cases were included. However, unless treatment initiation was very recent, we would have expected to see more veterans scoring below the depression threshold score. Our data are also from 2002–2004. Depression care within the VA has evolved significantly in subsequent years, in part as a result of the main trial’s findings.11

Given the prevalence of mental health disorders among veterans using the VA health care system, the VA is an exceptional laboratory for implementing and evaluating integrated primary care-mental health care delivery models.58 Not surprisingly, the VA is currently engaged in just such a national effort, chiefly through a mix of strategies of co-located mental health care, depression collaborative care arrangements, and/or referral to a behavioral health laboratory.34,59–61 Disease management programs that incorporate models like these, which include evidence-based guidelines, patient/provider education, collaborative care, reminder systems, and monitoring, have been shown to have significant effects on depression severity across multiple randomized trials.62 Our findings point to the importance of accelerating the implementation and spread of such models to address the substantial needs of depressed veterans in VA primary care settings, while also highlighting the importance of continual practice-based screening and surveillance. Further, since depression has historically been detected in only about 50% of cases, relying on clinician-documented major depression using chart review is likely to continue to underestimate the needs of depressed patients within or outside the VA.63,64 Practice-based screening using patient surveys is an important adjunct to effective case finding, monitoring and quality improvement programs in primary care.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded by the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Health Services Research and Development (HSR&D) Service and the Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) (Project #MHI 99–375 and MNT 01–027). The manuscript reflects baseline data from a group randomized trial (Trial Registration No. NCT00105820). Dr. Yano is funded under a VA HSR&D Research Career Scientist award (Project #05–195). Dr. Campbell was funded by a VA Office of Academic Affiliations (OAA) Associated Health Postdoctoral Fellowship Program at the Northwest Center for Outcomes Research at the time the study was conducted; he is now Assistant Professor at the University of Montana.

We would like to acknowledge key intervention team members, including Susan Vivell, PhD, MBA, and Brad Felker, MD, as well as project support staff, Carol Simons, Laura Rabuck, MPA, and Debbie Mittman, MPA. Special recognition goes to the frontline efforts of the original network-level depression care managers, including Karen Vollen, RN, Barbara Revay, RN, and Bill Raney, as well as the site principal investigators at participating facilities.

An earlier version of this work was presented as a poster at the national meeting of the Society for General Internal Medicine (SGIM), New Orleans, LA, May 13, 2005.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

References

- 1.Lowe B, Unutzer J, Callahan CM, Perkins AJ, Kroenke K. Monitoring depression treatment outcomes with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Med Care. 2004;42:1194–1201. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katon WJ, Unutzer J, Simon G. Treatment of depression in primary care: Where we are, where we can go. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1153–1157. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perez-Stable E, Mirana J, Munoz RF, Ying Y-W. Depression in medical outpatients: Under-recognition and misdiagnosis. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150:1083–1088. doi: 10.1001/archinte.1990.00390170113024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58(1):55–61. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olfson M, Marcus SC, Druss B, Elinson L, Tanielian T, Pincus HA. National trends in the outpatient treatment of depression. JAMA. 2002;287(2):203–209. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Egede LE. Failure to recognize depression in primary care: Issues and challenges. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:701–703. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0170-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edlund MJ, Unutzer J, Wells KB. Clinician screening and treatment of alcohol, drug and mental problems in primary care. Med Care. 2004;42(12):1158–1166. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pignone MP, Gaynes BN, Rushton JL, et al. Screening for depression in adults: A summary of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136:765–776. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-136-10-200205210-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fickel JJ, Yano EM, Parker LE, Rubenstein LV. Clinic-level process of care for depression in primary care settings. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2009;36:144–158. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0207-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell DG, Felker BL, Liu C-F, et al. Prevalence of depression-PTSD co-morbidity: Implications for clinical practice guidelines and primary care-based interventions. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(6):711–718. doi: 10.1007/s11606-006-0101-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chaney EF, Rubenstein LV, Liu C-F, Yano EM, Bolkan C, Lee ML, Simon BF, Lanto AB, Felker B, Uman J. Implementing collaborative care for depression treatment in primary care: A cluster randomized evaluation of a quality improvement practice redesign. Implement Sci. 2011:[in press]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Bonner L, Felker B, Chaney E, et al. Suicide risk response: Enhancing patient safety through development of effective institutional policies. In K Henriksen, JB Battles, E Marks & DI Lewin (Eds), Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation. Vol. 3, 507–519, 2005. [PubMed]

- 13.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB. Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. Primary care evaluation of mental disorders. Patient health questionnaire. JAMA. 1999;282:1737–1744. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.18.1737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: Validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284–1292. doi: 10.1097/01.MLR.0000093487.78664.3C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li C, Friedman B, Conwell Y, Fiscella K. Validity of the Patient Health Questionnaire 2 (PHQ-2) in identifying major depression in older people. J Am Geriatrics Soc. 2007;55(4):596–602. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Corson K, Gerrity MS, Dobscha SK. Screening for depression and suicidality in a VA primary care setting: 2 items are better than 1 item. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(11 Pt 2):839–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Institute of Mental Health. Depression. Available at http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/depression/complete-index.shtml. Accessed June 20, 2011.

- 18.Henkel V, Mergl R, Kohnen R, Maier W, Moller H-J, Hegerl U. Identifying depression in primary care: A comparison of different methods in a prospective cohort study. BMJ. 2003;326:200–201. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7382.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pinto-Meza A, Serrano-Blanco A, Penarrubia MT, Blanco E, Haro JM. Assessing depression in primary care with the PHQ-9: Can it be carried out over the telephone? J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:738–742. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0144.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Bayliss MS, McHorney CA, Rogers WH, Raczek A. Comparison of methods for scoring and statistical analysis of SF-36 health profile and summary measures: Summary of results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Med Care. 1995;33:264–279. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199501001-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-item short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fan VS, Au D, Heagerty P, Deyo RA, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. Validation of case-mix measures derived from self-reports of diagnosis and health. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(4):371–380. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00493-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, et al. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): Development and operating characteristics. Prim Care Psychiatry. 2003;9:9–14. doi: 10.1185/135525703125002360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Das AK, Olfson M, Gameroff MJ, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder in a primary care practice. JAMA. 2005;293:956–963. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.8.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Zhou Y. Effectiveness of the derived Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT-C) in screening for alcohol use disorders and risk drinking in the US general population. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(5):844–54. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000164374.32229.A2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradley KA, Bush KR, Epler AJ, et al. Two brief alcohol-screening tests from the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), validation in a female Veterans Affairs patient population. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(7):821–29. doi: 10.1001/archinte.163.7.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) JAMA. 2003;289(23):3095–3105. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rogers WH, Kazis LE, Miller DR, et al. Comparing the health status of VA and non-VA ambulatory patients: the veterans’ health and medical outcomes studies. J Ambul Care Manage. 2004;27(3):249–62. doi: 10.1097/00004479-200407000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katon W. Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Bio Psychiatry. 2003;54:216–226. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(03)00273-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kirchner JE, Curran GM, Aikens J. Detecting depression in VA primary care clinics. Psych Services. 2004;55(4):350. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.4.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Craig TJ. Case-finding for depression among medical outpatients in the Veterans Health Administration. Med Care. 2006;44(2):175–181. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000196962.97345.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kirkcaldy RD, Tynes LL. Depression screening in a VA primary care clinic. Psych Services. 2006;57(12):1694–1696. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.57.12.1694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oslin DW, Ross J, Sayers S, Murphy J, Kane V, Katz IR. Screening, assessment and management of depression in VA primary care clinics: The Behavioral Health Laboratory. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(1):46–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0267.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The Management of Major Depressive Disorder Working Group. Veterans Health Administration/Department of Defense clinical practice guidelines for the management of major depressive disorder in adults. Version 2.0, February 2000, Washington DC.

- 36.Angst J, Angst F, Stassen HH. Suicide risk in patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psych. 1999;60(Suppl 2):57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Foster T, Gillespie K, McClelland R, Patterson C. Risk factors for suicide independent of DSM-III-R Axis I disorder. Brit J Psychiatry. 1999;175:175–179. doi: 10.1192/bjp.175.2.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Uebelacker LA, German NM, Gaudiano BA, Miller IW. Patient health questionnaire depression scale as a suicide screening instrument in depression primary care patients: A cross-sectional study. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011;13(1). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.Schulberg HC, Lee PW, Bruce ML, et al. Suicidal ideation and risk levels among primary care patients with uncomplicated depression. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(6):523–528. doi: 10.1370/afm.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Veterans Health Administration. Suicide prevention. Available at www.mentalhealth.va.gov/suicide_prevention/index.asp, accessed June 22, 2011.

- 41.Nutting PA, Dickinson LM, Rubenstein LV, Keeley RD, Smith JL, Elliott CE. Improving detection of suicidal ideation among depressed patients in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(6):529–536. doi: 10.1370/afm.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Trude S, Stoddard JJ. Referral gridlock: Primary care physicians and mental health services. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:442–449. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.30216.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rubenstein LV, Parker LE, Meredith LS, et al. Understanding team-based quality improvement for depression in primary care. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(4):1009–1029. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0560.2002.63.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gilbody S, Whitty P, Grimshaw J, Thomas R. Educational and organizational interventions to improve the management of depression in primary care: A systematic review. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3145–51. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.23.3145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Katon W, Schulberg H. Epidemiology of depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1992;14:237–247. doi: 10.1016/0163-8343(92)90094-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Felker BL, Hedrick SC, Chaney EF, et al. Identifying depressed patients with a high risk of comorbid anxiety in primary care. Primary Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;5:104–110. doi: 10.4088/PCC.v05n0301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weilburg JB, Stafford RS, O’Leary KM, Meigs JB, Finkelstein SN. Costs of antidepressant medications associated with inadequate treatment. Am J Manag Care. 2004;10(6):357–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Frank RG, McGuire TG, Normand ST, Goldman HH. The value of mental health care at the system level: The case of treating depression. Health Affairs. 1999;18(5):71–88. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.18.5.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rost K, Pyne JM, Dickinson LM, LoSasso AT. Cost-effectiveness of enhancing primary care depression management on an ongoing basis. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(1):7–14. doi: 10.1370/afm.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Klinkman MS. The role of algorithms in the detection and treatment of depression in primary care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(Suppl 2):19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zlotnick C, Rodriquez BF, Wiesberg RB, et al. Chronicity in posttraumatic stress disorder and predictors of the course of posttraumatic stress disorder among primary care patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192:153–159. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000110287.16635.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glied S. Too little time? The recognition and treatment of mental health problems in primary care. Health Serv Res. 1998;33(4):891–910. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robbins JM, Kirmayer LJ, Cathebras P, Yaffe MJ, Dworkind M. Physician characteristics and the recognition of depression and anxiety in primary care. Med Care. 1994;32(8):795–812. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199408000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wittchen HU, Kessler RC, Beesdo K, Krause P, Hofler M, Hoyer J. Generalized anxiety and depression in primary care: Prevalence, recognition and management. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:24–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lecrubier Y. Posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care: A hidden diagnosis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(suppl 1):49–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ramaswamy S, Madaan V, Qadri F, et al. A primary care perspective on posttraumatic stress disorder for the Department of Veterans Affairs. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7(4):180–187. doi: 10.4088/PCC.v07n0407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zeiss AM, Karlin BE. Integrating mental health and primary care services in the Department of Veterans Affairs health care system. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2008;15:73–78. doi: 10.1007/s10880-008-9100-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Katon WJ, Korff M, Lin E, et al. Collaborative management to achieve treatment guidelines: Impact on depression in primary care. JAMA. 1995;273(13):1026–1031. doi: 10.1001/jama.1995.03520370068039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Korff M, Gruman J, Schaefer J, Curry SJ, Wagner EH. Collaborative management of chronic illness. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127(12):1097–1102. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-12-199712150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Post EP, Stone WW. The Veterans Health Administration’s primary care-mental health integration initiative. N C Med J. 2008;69(1):49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Neumeyer-Gromen A, Lampert T, Soz D, Stark K, Kallischnigg G, Math D. Disease management programs for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Med Care. 2004;42:1211–1221. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200412000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rost K, Zhang M, Fortney J, Smith J, Coyne J, Smith GR. Persistently poor outcomes of undetected major depression in primary care. Gen Hosp Psych. 1998;20:12–20. doi: 10.1016/S0163-8343(97)00095-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wells KB, Hayes RD, Burnam A, et al. Detection of depressive disorder for patients receiving prepaid or fee-for-service care: Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989;262:3298–3303. doi: 10.1001/jama.1989.03430230083030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bradley KA, Maynard C, Kivlahan DR, et al. The relationship between alcohol screening questionnaires and mortality among male VA outpatients. J Stud Alcohol. 2001;62:826–833. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]