Abstract

BACKGROUND

Hospital boards of directors can play a pivotal role in improving care, yet we know little about how the boards of hospitals that disproportionately serve minority patients engage in this issue.

OBJECTIVES

To examine how boards of directors at black-serving hospitals are engaged in quality of care issues and compare priorities and practices of black-serving and non-black-serving hospital boards.

DESIGN

We identified all nonprofit U.S. hospitals in the top decile of proportion of elderly black patients (“black-serving”) and surveyed their board chairpersons and a national sample of chairpersons from other nonprofit U.S. hospitals (“non-black-serving”).

PARTICIPANTS

Board chairpersons of black-serving and non-black-serving U.S. hospitals.

MAIN MEASURES

Board chairpersons’ familiarity and expertise with quality of care issues, level of engagement with quality management, prioritization of quality issues, and efforts to improve quality or to reduce racial disparities in the quality of care.

KEY RESULTS

We received responses from 79% of black-serving hospitals and 78% of non-black-serving hospitals. We found that board chairpersons from black-serving hospitals less often reported having at least moderate expertise in quality of care (68% versus 79%, P = 0.04) or rating it as one of the top two priorities for board oversight (48% versus 57%, P = 0.09) or for CEO performance evaluation (40% versus 50%, P = 0.05). Only 14.2% of board chairpersons from black-serving hospitals (and 7.7% of non-black-serving hospitals) agreed with the statement that disparities exist among my hospital patients, although less than 10% of all board chairpersons reported examining quality or patient satisfaction data stratified by race.

CONCLUSIONS

Board chairpersons of black-serving hospitals report less expertise with quality of care issues and are less likely to give high priority to these issues than board chairpersons of non-black-serving hospitals. Interventions to engage and educate board members in issues of quality and racial disparities may be needed to improve quality and reduce disparities in care.

KEY WORDS: quality of care, disparities, quality improvement

INTRODUCTION

Racial and ethnic disparities in quality of care and health outcomes are well known and persistent,1 yet their underlying causes are still not well understood.1,2 growing evidence that Blacks and Hispanics often receive care in hospitals with fewer clinical resources and lower quality of care,3,4 suggesting that the site of care likely plays an important role in disparities. A recent analysis also found that some of the disparities seen nationally can be explained by the fact that minorities, including African Americans and Hispanics, more frequently receive care in low-performing hospitals.5

Policymakers seeking to improve the quality of care or reduce disparities have increasingly focused on the role of hospital boards in addressing these issues. The National Quality Forum, the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI), and others have underscored the importance of governance in such efforts6,7 Our work and those of others suggest that boards can play a critical role in ensuring a high level of performance.8–12 In contrast, little is known about the boards of hospitals that disproportionately serve minority patients with regard to their engagement with quality of care issues, their perceptions about the importance of healthcare disparities, or the actions they have taken to address issues of both quality and disparities that exist within their institutions. Because elderly black patients often receive care at low-performing hospitals, the level of engagement on issues of hospital quality and racial disparities in that care exhibited by boards by at hospitals that serve them may be especially important.

In this study, we examined survey data from a national sample of hospital board chairpersons to determine how boards of nonprofit black-serving hospitals judge their own expertise and familiarity with the quality of care delivered; how they prioritize the oversight of quality of care issues; how they engage in efforts to measure and ensure quality; and how they perceive disparities in care and take action to address them. For each of these dimensions, we used a national sample of non-black-serving hospitals as a control group to determine whether there are differences in boards’ practices between black-serving and non-black serving hospitals.

METHODS

Overview of Hospital Governance

Generally, one board of directors or board of trustees, led by a chairperson, oversees each nonprofit hospital in the United States. However, the number of hospitals a board might oversee varies widely since hospitals belonging to a large healthcare system are frequently overseen by one board. For-profit hospitals, however, often have multiple boards, making it difficult to attribute the oversight of quality issues to any single board. Therefore, we focused our survey on the 85% of U.S. hospitals that are nonprofit (public or private).

Data and Sampling

We identified 3,410 nonprofit acute-care hospitals that reported quality data to the Hospital Quality Alliance (HQA). We obtained their characteristics from the American Hospital Association (AHA) annual survey, including profit status. To categorize hospitals as black-serving, we used previous methodology by Jha et al. that identified black-serving and Hispanic-serving providers and detailed their characteristics and performance.3,4 First, we used the Medicare Provider Analysis and Review (MedPAR) 100% file to identify the race and ethnicity of discharged elderly Medicare beneficiaries age 65 and older for each hospital. We calculated and ranked each hospital into deciles based on their proportion of discharged elderly black patients. To examine quality performance, we used the Hospital Quality Alliance data and calculated an overall performance score for each hospital (see Technical Appendix, available online, for details of the methods and measures).13–15 We were unable to calculate summary scores for 119 hospitals (because they had inadequate sample sizes to calculate stable scores), which left 3,291 institutions in our sample.

We first chose a census of all 329 hospitals that were in the top decile in the proportion of elderly black patients seen (“black-serving hospitals”). As a control, we randomly selected another 671 of the remaining 2,962 institutions (“non-black-serving hospitals”). In this sample of non-black-serving hospitals, we over-sampled those in the top and bottom decile of HQA performance (for a separate analysis).9 However, in order to ensure that these 671 hospitals were nationally representative of all non-black-serving hospitals, we used appropriate weighting. Therefore, we were left with two groups of hospitals for our analysis: a census of all black-serving hospitals and a representative sample of all non-black-serving hospitals.

Survey Development

We developed a 44-item survey based on a review of the literature and interviews with 15 governance experts and board members (please refer to Technical Appendix, available online). We identified six pertinent item domains: (1) board training and expertise in the quality of care; (2) quality as a priority for board oversight and evaluation of the performance of the chief executive officer (CEO); (3) the board as an influential entity in the quality of care delivered; (4) awareness of current quality performance; (5) specific board functions, such as setting priorities and examining dashboard data on quality of care; and (6) perceptions, knowledge, and practices concerning disparities in care. We then modified the survey content accordingly after feedback formal cognitive testing (with six respondents) and after six additional interviews. Each of the questions used in this analysis and their response categories are available online in the Technical Appendix. The questions covered a broad range of themes in each of the six domains identified above and had between two to five response categories. There were two main types of questions: those that asked about the respondent’s assessment of the hospital or the Board (i.e. “How would you rate the board’s expertise on issues of quality and safety of care?”), often with four response categories (i.e. no expertise, minimal expertise, moderate expertise, or very substantial expertise), or those that asked about specific activities (i.e. how often is quality performance on the agenda?), often with five response categories (i.e. every meeting, most meetings, some meetings, few/rare meetings, or never on the agenda at board meetings).

Survey Administration

The survey research firm Westat, Inc., fielded our survey in 2008 to the 922 board chairpersons whose boards governed the 1,000 hospitals in our sample. These individuals were initially contacted by letter and asked to participate in a national survey of hospital board chairpersons that examined governance practices related to quality management. Board chairpersons were asked to serve as a reporter for the full board. For initial non-respondents, we conducted two additional mailings and telephone follow-up.

Analysis

Our analytic approach aimed to paint a national portrait of black-serving hospitals and compare them to a nationally-representative sample of non-black-serving hospitals. Therefore, all responses received from the non-black sample were weighted (with those hospitals that were oversampled being under-weighted) to create national estimates of non-black-serving hospitals. For questions with four response categories, we divided the responses into two categories by combining the first two and last two responses (for the above example, if the question asked about the level of expertise, we combined “no expertise” and “minimal expertise” into a single category and “moderate” and “very substantial” expertise into a second group). In questions with five response categories, we again grouped the first two (i.e. quality on the agenda at every or most meetings) or occasionally used, when available, natural cut-points (e.g. IHI suggests that quality should be on the agenda at every meeting and therefore. Therefore, we grouped responses into hospitals that have quality on the agenda at every meeting versus those that do not). In all instances, we ran sensitivity analyses to ensure that our findings did not change qualitatively based on the groupings we used.

We first examined the characteristics of respondents and non-respondents of both black-serving and non-black-serving hospitals. Although only small, inconsistent differences were found, we adjusted our analyses for potential non-response bias (using the inverse of the likelihood of response as a weight). We employed bivariate techniques to examine differences in the characteristics of black-serving and non-black-serving hospitals. After identifying substantive differences, we employed bivariate and multivariate modeling techniques for subsequent analyses.

Using t-tests, analyses of variance, and chi-squared tests, as appropriate, we compared the responses of black-serving and non-black-serving hospitals to individual questions. We then built multivariate logistic regression models to adjust for baseline differences in hospital characteristics (e.g. size, region, location, ownership, and teaching status). In prior work, we found that using alternative approaches to minimizing confounding, such as stratified or restricted analyses, led to results very similar to those of the multivariate models.9 We examined responses both at the chairperson level and at the hospital level. Given that most chairpersons in our sample responded for a single hospital, the results were nearly identical and are only presented at the hospital level.

RESULTS

Of the 922 chairpersons in our overall sample, we received responses from 722, a rate of 78.3%. These 722 individuals oversaw 767 hospitals. Response rates were above 75% for both black-serving and non-black-serving hospitals. No statistically significant differences were found between respondents and non-respondents, and the hospital characteristics of the respondents were similar to those of the entire sample. Among respondents, black-serving hospitals—more often than non-black-serving hospitals—were large, urban-based, in the South, publicly owned, and major teaching hospitals (urban location, P = 0.09, all others P < 0.0001, Table 1). The proportion of black patients seen by black-serving hospitals was significantly higher than among non-black-serving hospitals (45.0% versus 4.7%, P < 0.0001), and black-serving hospitals had marginally lower performance on HQA process metrics than non-black-serving hospitals (82.0% versus 84.4%, P = 0.003).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Responding Black-Serving and Non-Black-Serving Hospitals

| Black-serving hospitals | Non-black-serving hospitals | P-value* | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 235 | N = 532 | |||

| Variable | % | % | ||

| Size | Small (<100 beds) | 26.0 | 45.1 | P < 0.0001 |

| Medium (100–399 beds) | 51.5 | 45.8 | ||

| Large (≥ 400 beds) | 22.6 | 9.0 | ||

| Region | Northeast | 16.6 | 19.9 | P < 0.0001 |

| Midwest | 15.3 | 35.9 | ||

| South | 63.4 | 28.1 | ||

| West | 4.7 | 16.0 | ||

| Ownership | Private | 62.1 | 78.2 | P < 0.001 |

| Public | 37.9 | 21.8 | ||

| Major teaching hospital | 21.3 | 6.0 | P < 0.0001 | |

| Urban location | 80.9 | 74.6 | P = 0.09 | |

| Proportion of patients who are black | 45.0 | 4.7 | P < 0.0001 | |

| Proportion of patients who are hispanic | 2.2 | 1.3 | P < 0.0001 | |

| Proportion of patients who are on Medicaid | 24.3 | 15.8 | P < 0.0001 | |

| HQA Quality Summary Score | 82.0 | 84.4 | P = 0.003 | |

Respondents from black-serving hospitals had served on their hospital boards for an average of 12.4 years (Standard Deviation [SD] = 6.5 years) and were chairpersons for an average of 5.7 years. Respondents from non-black-serving hospitals had served an average of 11.3 years on their boards (p-values for comparison between black-serving and non-blacking-serving hospital = 0.21), with an average of 4.6 years as chairpersons (p = 0.02). Chairpersons from black-serving hospitals were significantly more likely to be physicians compared to chairpersons from non-black-serving hospitals (15.0% versus 5.0%, P < 0.001).

Board Training and Expertise in Quality of Care

We found that chairpersons of black-serving hospitals were less likely to report that the board had moderate or very substantial expertise in issues regarding quality and safety of care compared to chairpersons of non-black-serving hospitals (68.5% versus 78.5%, P = 0.04, Table 2). Similarly, respondents from black-serving hospitals were less likely to report being at least somewhat familiar with the HQA program than were board chairpersons of non-black-serving hospitals (58.4% versus 72.0%, P = 0.01). Hospital boards at black-serving hospitals were also less likely to report having formal training in clinical quality management, although this difference did not reach statistical significance (26.3% versus 35.5%, P = 0.07). Among hospitals whose board members were trained in issues of clinical quality, black-serving hospital board members spent a median of 4.2 total hours on quality issues, while board members of non-black-serving hospitals spent 5.5 total hours (P = 0.17).

Table 2.

Board Chairperson’s Perspective on Board Expertise and Training among Black-serving and Non-Black-serving Hospitals

| Black-serving Hospitals N = 235 | Non-black-Serving Hospitals N = 532 | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The board chairperson reports that the board: | |||

| % | % | ||

| Has at least moderate expertise in quality of care | 68.5 | 78.5 | P = 0.04 |

| Is familiar with the Hospital Quality Alliance program | 58.4 | 72.0 | P = 0.01 |

| Has its own formal training program that covers clinical quality | 26.3 | 35.5 | P = 0.07 |

| Considers expertise in clinical quality to be at least moderately important in selecting new members | 43.3 | 43.6 | P = 0.95 |

*Adjusted for hospital size using number of beds, hospital region, location (urban versus rural), teaching status, and ownership

Quality of Care as a Priority for Board Oversight and CEO Performance Evaluation

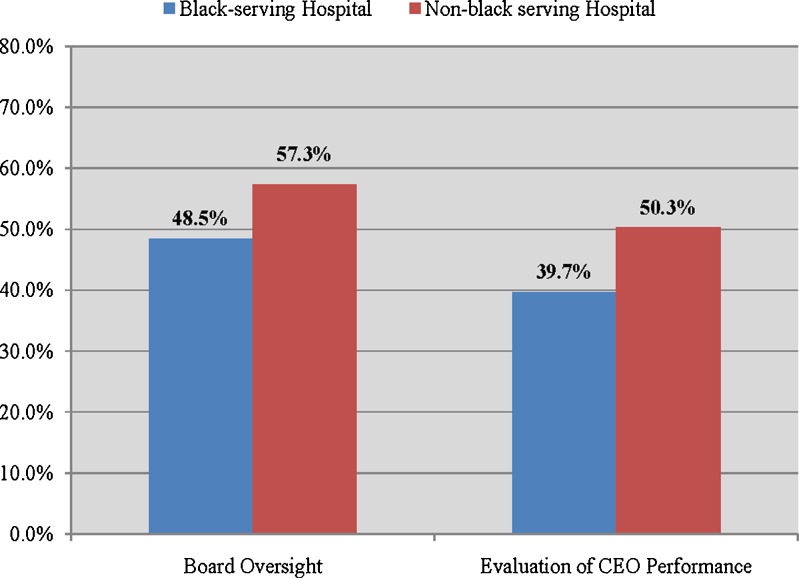

Board chairpersons of black-serving hospitals were less likely than respondents from non-black-serving hospitals to identify clinical quality as one of the top two priorities for board oversight (48.5% versus 57.3%, P = 0.09, Figure 1) or evaluating CEO performance (40.0% versus 50.3%, P = 0.05) when asked to select from a list of six areas. Other choices of top two priorities for board oversight were: financial performance (74.4% black-serving hospitals versus 60.7% non-black-serving hospitals, P = 0.009), operations (9.8% versus 10.4%, P = 0.87), business strategy (25.9% versus 26.8%, P = 0.85), patient satisfaction (24.7% versus 24.0%, P = 0.88), and community benefit (11.1% versus 19.8%, P = 0.03).

Figure 1.

Percentage of board chairpersons whoidentify quality of care as one of the top two priorities for board oversight or CEO performance evaluation. These results are adjusted for number of beds, hospital region, location (urban versus rural), teaching status, and ownership. P-value for the difference between top- and bottom-performing hospitals: P = 0.09 for comparison of board oversight; P = 0.05 for comparison of evaluation of CEO performance.

Perceived Influences on the Quality of Care

When respondents were asked to rate the top two influences on the quality of care delivered at their respective institutions, over 65% of all respondents believed that the CEO was highly influential whereas only a small proportion of all respondents identified the board as having an important role. Black-serving hospitals were less likely to identify the board as one of the top two influences on quality of care compared to non-black-serving hospitals (12% versus 21%, P = 0.02); however, there was no statistically significant difference in the frequency with which the CEO was identified as being the primary driver of quality (65% versus 69%, P = 0.45).

Performance-Reporting, Agenda-Setting, and Board Functions

When examining the functions of hospital boards, boards of black-serving hospitals were somewhat less likely than non-black-serving hospitals to report the inclusion of quality performance as a topic on every board meeting agenda (60.2% versus 67.7%, P = 0.13, Table 3) or having a subcommittee on quality (57.1% versus 65.7%, P = 0.09). Both hospital groups were equally likely to report spending at least 20% of meeting time on quality of care issues. Boards of black-serving hospitals were also less likely to regularly review their institution’s quality dashboard than were boards of non-black-serving hospitals (65.8% versus 80.9%, P = 0.001). Similarly, quality data were less likely to be reviewed by black-serving hospitals than by non-black-serving hospital boards in three of the four areas measured: hospital-acquired infections (63.1% versus 70.7%, P = 0.15), medication errors (60.8% versus 72.4%, P = 0.03), and patient satisfaction (67.8% versus 77.5%, P = 0.04).

Table 3.

The Function of Boards Between Black-Serving and Non-Black-Serving Hospitals

| Black-serving hospitals | Non-black-serving hospitals | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 235 | N = 532 | ||

| % | % | ||

| Quality performance is on the agenda at every board meeting | 60.2 | 67.7 | P = 0.13 |

| Board has a subcommittee on quality | 57.1 | 65.7 | P = 0.10 |

| Board spends ≥ 20% of its time on quality-of-care issues | 42.5 | 41.9 | P = 0.92 |

| Board regularly reviews quality dashboard | 65.8 | 80.9 | P = 0.001 |

| Board reviews the following data on at least a quarterly basis: | |||

| Hospital-acquired infections | 63.1 | 70.7 | P = 0.15 |

| Medication errors | 60.8 | 72.4 | P = 0.03 |

| The Joint Commission’s core measures | 59.2 | 57.5 | P = 0.75 |

| Patient satisfaction | 67.8 | 77.5 | P = 0.04 |

*Adjusted for hospital size using number of beds, hospital region, location (urban versus rural), teaching status, and ownership

Perceptions and Activities Concerning Disparities in Care

We asked respondents about their perceptions of disparities in care in society at large and at their own institutions, as well as about their own activities regarding disparities. The majority of board chairpersons agreed that disparities in the quality of care provided to patients exist broadly in society (66.7% versus 50.0% among board chairpersons of black-serving hospitals and non-black-serving hospitals, respectively; P = 0.002, Table 4) and that disparities vary substantially among U.S. hospitals (59.0% versus 51.4%, P = 0.16). Only a small proportion of respondents believed there were disparities in the quality of care provided to patients within their own hospitals (14.2% black-serving hospitals versus 7.7% non-black-serving hospitals; P = 0.05).

Table 4.

Board Chairpersons’ Perceptions Regarding Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Care

| Black-serving hospitals | Non-black-serving hospitals | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 235 | N = 532 | ||

| Proportion stating that they agree “a lot” or “a moderate amount” | % | % | |

| Views regarding disparities in care: | |||

| Disparities in the quality of care exist in society-at-large | 66.7 | 50.0 | P = 0.002 |

| Disparities in the quality of care vary substantially among U.S. hospitals | 59.0 | 51.4 | P = 0.16 |

| Disparities in the quality of care exist among my hospitals’ patients | 14.2 | 7.7 | P = 0.05 |

| Activities addressing healthcare disparities include: | |||

| Analyses of quality data by race and ethnicity | 11.0 | 9.2 | P = 0.58 |

| Analyses HCAHPS† survey data by race and ethnicity | 9.4 | 5.8 | P = 0.22 |

| Provides cultural competency training | 46.8 | 34.2 | P = 0.02 |

*Adjusted for hospital size using number of beds, hospital region, location (urban versus rural), teaching status, and ownership

†HCAHPS is the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems survey, which reports patients’ perspectives on hospital

When asked if they examined their own quality of care data stratified by race or ethnicity, only about one in ten chairpersons reported doing so (11.0% black-serving hospitals versus 9.2% non-black-serving hospitals; P = 0.58, Table 4). Fewer chairpersons reported that they examined patient satisfaction data stratified by race or ethnicity. Respondents from black-serving institutions were more likely than other respondents to report having cultural competency training for their providers (46.8% versus 34.2%, P = 0.02).

DISCUSSION

We found substantial differences between the boards of black-serving hospitals and non-black-serving hospitals in their engagement with quality of care issues. Boards of black-serving hospitals are less likely to report having expertise with quality of care issues, being knowledgeable about specific quality programs, and identifying quality as a top priority for board oversight or the evaluation of CEO performance. Black-serving hospital boards were less likely than non-black-serving hospital boards to report having a subcommittee on quality or examining quality dashboards regularly. These findings were evident despite the fact that black-serving hospitals were more likely to be major teaching hospitals and have a physician as the board chairperson; factors of which one might associate with higher quality. In previous work that examined the same questions and issues between high-performing and low-performing institutions, the responses to these questions correlated closely with better performance.9

We also found substantial differences between black- and non-black-serving hospitals regarding issues of disparities in care. We were surprised, for example, to find that despite substantial evidence documenting the pervasiveness and persistence of racial and ethnic disparities in the quality of care, many hospital chairpersons do not recognize their prevalence.16 Only 14% of black-serving hospitals and 8% of non-black-serving hospitals reported that disparities in care existed at their own institutions. However, nearly 90% of respondents do not examine quality of care data stratified by race and ethnicity, suggesting that many board chairpersons may be unaware of disparities that exist within their institutions.

This study suggests one potential new avenue for reducing disparities and improving quality: education targeted at boards of hospitals. Our findings suggest that most boards would benefit from such an intervention. Further, given that hospital chairpersons of black-serving hospitals have even low levels of knowledge and expertise regarding quality of care, efforts that are targeted and tailored towards these institutions may be particularly helpful in improving quality and potentially reducing disparities in care. Our prior findings further suggest that boards of high-performing hospitals are more likely to not only prioritize quality, but to also have subcommittees on quality, to regularly examine quality dashboards with trends and benchmarks, and to routinely review key data on quality.9 Thus, it is possible that targeting the engagement of black-serving boards in these activities may help their hospitals provide more effective and higher quality care.

Although other studies have examined differences in governance structure in relation to quality of care among hospitals, this study provides the first national comparison of board chairpersons at black-serving and non-black-serving hospitals. Joshi and colleagues found a modest relationship between board knowledge of quality issues and the clinical quality practices at their institutions.8 Weiner and Shortell found that quality-improvement programs were more likely to be present at hospitals with boards engaged in quality of care issues.10

Our study has limitations. First, despite a high response rate (78.3%), there may be concerns about potential bias due to differences between respondents and non-respondents. Although we attempted to correct for non-response bias using statistical approaches, current techniques are imperfect. Second, we categorized black-serving hospitals based on the proportion of discharged elderly black patients. Although black patients represent a large and important minority group, we could not examine care at hospitals with large proportions of other minority groups such as Hispanics. Black-servings hospitals were more likely to be large and located in the South and, while we employed various analytic techniques (including multivariate and stratified analyses) to address potential confounding by these and other factors, we cannot rule out other residual confounding. Third, we did not directly determine the impact of differences in the governance of quality performance, although our previous study did show that leadership engaged in issues of quality was highly associated with better hospital performance.9 Fourth, the subjective nature of survey questions may have lead participants to over or under report their responses to individual questions.

Additionally, we did not have data on the demographic characteristics of respondents, such as race and ethnicity, and thus were unable to directly examine whether specific characteristics of board chairpersons had an impact on board engagement in quality of care and efforts to reduce disparities. We did not have data on the financial health of the institutions and it is possible that black-serving hospitals are more financially stressed than other hospitals. In that case, it may be appropriate for boards to spend a greater amount of their time on financial issues than might be required otherwise. However, boards should still be able ensure that the quality of care is adequate. Finally, we only surveyed nonprofit hospitals and were thus unable to examine the 15% of all U.S. hospitals that are for-profit institutions and although we undertook numerous activities to verify that the chairperson completed our survey (please see Technical Appendix), it is possible that a few surveys were completed by other board members.

In conclusion, we examined the knowledge, priorities, and practices among the boards of directors of black-serving hospitals in the United States and found that they were less likely to be knowledgeable about quality-of-care issues, to prioritize quality, or to engage in specific quality practices that have been shown to correlate with better hospital performance on HQA measures. Moreover, a majority of board chairpersons at black-serving hospitals did not believe that disparities were a problem within their own hospitals and their boards were not substantially engaged in activities to eliminate disparities. For clinicians and clinical leaders, these findings suggest that targeted interventions designed to help these hospital boards prioritize issues of quality and disparities in care may substantially improve care for all patients, as well as have a disproportionately beneficial impact on the care provided to minority patients.

Acknowledgments

Contributors

N/A

Funders

The project was funded by the Hauser Center for Nonprofit Organizations at Harvard University and the Rx Foundation, Cambridge, MA.

Prior Presentations

N/A

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jha AK, Fisher ES, Li Z, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Racial trends in the use of major procedures among the elderly. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(7):683–691. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa050672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Medicine Io. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Li Z, Epstein AM. Concentration and quality of hospitals that care for elderly black patients. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(11):1177–1182. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.11.1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. The characteristics and performance of hospitals that care for elderly Hispanic Americans. Health Aff (Proj Hope) 2008;27(2):528–537. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.2.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hasnain-Wynia R, Baker DW, Nerenz D, et al. Disparities in health care are driven by where minority patients seek care: examination of the hospital quality alliance measures. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(12):1233–1239. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.12.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Forum NQ. Hospital Governing Boards and Quality of Care: A Call to Responsibility. Washington, D.C: National Quality Forum; 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Getting Boards on Board. http://www.ihi.org/IHI/Programs/Campaign/BoardsonBoard.htm. Accessed August 22, 2011.

- 8.Joshi MS, Hines SC. Getting the board on board: engaging hospital boards in quality and patient safety. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32(4):179–187. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(06)32023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jha AK, Epstein AM. Hospital Governance And The Quality Of Care. Health affairs (Project Hope). Nov 6 2009. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Weiner BJ, Shortell SM, Alexander J. Promoting clinical involvement in hospital quality improvement efforts: the effects of top management, board, and physician leadership. Heal Serv Res. 1997;32(4):491–510. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sehgal AR. Impact of quality improvement efforts on race and sex disparities in hemodialysis. Jama. 2003;289(8):996–1000. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.8.996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trivedi AN, Zaslavsky AM, Schneider EC, Ayanian JZ. Trends in the quality of care and racial disparities in Medicare managed care. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(7):692–700. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa051207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kahn CN, 3rd, Ault T, Isenstein H, Potetz L, Gelder S. Snapshot of hospital quality reporting and pay-for-performance under Medicare. Health Aff (Proj Hope) 2006;25(1):148–162. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.1.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jha AK, Li Z, Orav EJ, Epstein AM. Care in U.S. hospitals–the Hospital Quality Alliance program. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(3):265–274. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa051249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Werner RM, Bradlow ET. Relationship between Medicare's hospital compare performance measures and mortality rates. Jama. 2006;296(22):2694–2702. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.22.2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press;2002. [PMC free article] [PubMed]