ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Sleep disturbance is a significant problem for adults presenting to primary care. Though it is recommended that primary care providers screen for sleep problems, a brief, effective screening tool is not available.

OBJECTIVE

The aim of this preliminary study was to test the utility of item three of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9-item (PHQ-9) as a self-report screening test for sleep disturbance in primary care.

DESIGN

This was a cross-sectional survey of male VA primary care patients in Syracuse and Rochester, NY. Sensitivity and specificity statistics were calculated as well as positive and negative predictive value to determine both whether the PHQ-9 item-3 can be used as an effective sleep screen in primary care and at what PHQ item-3 cut score patients should be further assessed for sleep disturbance.

PARTICIPANTS

One hundred and eleven male, VA primary care patients over the age of 18 and without gross neurological impairment participated in this one-session, in-person study.

MEASURES

During the research session, patients completed several questionnaires, including a basic demographic questionnaire, the PHQ-9, and the Insomnia Severity Index (ISI).

KEY RESULTS

PHQ-9 item 3 significantly correlated with the total score on the ISI (r = 0.75, p < 0.0001). A cut score of 1 on the PHQ-9 item 3, indicating sleep disturbance at least several days in the last two weeks, showed the best balance of sensitivity (82.5%) and specificity (84.5%) as well as positive (78.4%) and negative (91%) predictive value.

CONCLUSIONS

Item 3 of the PHQ-9 shows promise as a screener for sleep problems in primary care. Using this one-item of a popular screening measure for depression in primary care allows providers to easily screen for two important issues without unnecessarily adding significant burden.

KEY WORDS: sleep disorders, screening, primary care

Sleep disturbances, like insomnia and excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), are highly prevalent in primary care.1,2 Insomnia is common among the general population, with numerous population-based studies reporting prevalence rates of approximately 30% for insomnia complaint and 10% for chronic insomnia,3 with rates in primary care even higher.1,4–6 Prevalence rates for EDS vary even more widely (from 1% to 30%) based on the operationalization of the term.7

The presence of insomnia, hypersomnia or EDS may constitute a symptom of a sleep disorder, a side effect of a medication, or a symptom of depression.7 Nonetheless, together and separately, these sleep disturbances are associated with their own significant morbidity and societal costs and often contribute to distress in patients. Experiencing sleep disturbances increases the likelihood of medical and psychiatric morbidity, contributes to greater healthcare utilization and accidents, and is associated with poor occupational performance and decreased quality of life.8–14 The economic impact of both insomnia and EDS is substantial, costing approximately $100 billion a year in the U.S..14–17

Although there is little research examining hypersomnia within primary care, insomnia and EDS are common complaints yet rarely mentioned during office visits18,19 or as the reason for making an appointment.20 Therefore, it has been suggested that screening for insomnia during routine primary care visits might be an effective secondary prevention effort,19,20 especially because there are several efficacious pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatments.3,21 Similarly, sleep disturbances related to EDS and/or hypersomnia continue to be under-diagnosed22 and, likely under-treated, despite the existence of effective treatments.23

The implementation of interventions requires primary care providers (PCPs) to have an efficient and effective way of identifying sleep disturbance in their patients.20 PCPs cannot be expected to implement the increasing number of recommended screenings each year unless efforts are made to ease this burden. Because it is currently recommended that PCPs routinely screen for depression in adults,24 and the Personal Health Questionnaire-925 (PHQ-9) is recommended as an effective screening measure for depression,26 it would simplify the process for providers if the PHQ-9 could also be used to screen for sleep disturbance. One item on the PHQ-9 assesses sleep; it asks individuals to indicate how often in the past two weeks they have had difficulty falling or staying asleep (i.e., an insomnia screening question) or sleeping too much (i.e., a hypersomnia screening question). The insomnia portion of this question has been used in several epidemiologic studies to identify insomnia7 and similar items exist on validated insomnia instruments.27 The hypersomnia portion of the PHQ-9 sleep item is not as well represented in epidemiologic studies.7

Therefore, the purpose of this preliminary study was to examine whether the sleep item on the PHQ-9 could be used as an adequate screener for sleep disturbance in a Veteran’s Affairs (VA) primary care setting with a focus on insomnia in particular. The VA is an ideal setting to examine this question because it requires annually screening patients for depression using the PHQ-2 and can follow-up any positive screen with a PHQ-9 questionnaire.28

METHODS

Sample

Participants were recruited between February 2009 and May 2010 as part of a larger, cross-sectional, descriptive study investigating the prevalence of and relationship between physical and mental health risk factors (e.g. depression, smoking) in patients attending VA primary care clinics. Three recruitment methods were used: direct PCP referral, primary care waiting room referral, or through the Behavioral Health Assessment Center (BHAC). BHAC is an extension of the Syracuse and Rochester VA primary care clinics and employs health technicians who complete a comprehensive clinical assessment of patients’ mental health symptomatology over the telephone.29 Veterans are called for this assessment either because of a direct referral from their PCP or because they scored positive on an annual primary care screen for hazardous alcohol use (scores of 4 and above for men and 3 or above for women on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test—Consumption (AUDIT-C)30). At the end of the phone call, the patient is asked if he/she is willing to be contacted regarding research participation. Patients expressing interest in research were then contacted via telephone and recruited for the study. As such, most of the patients in this sample were regular drinkers, although level of alcohol consumption was not an inclusion criterion for this study. Patients were eligible to participate if they were 18 years of age or older, did not exhibit gross neurological impairment, and attended a primary care clinic at the Syracuse VA Medical Center or the Rochester Outpatient Clinic.

A total of 575 patients were eligible to participate and were contacted regarding research participation in this or other studies being conducted contemporaneously. Of these, 220 participants declined research participation and 242 participated in other studies. Thus, the initial sample for this study consisted of 113 participants.

Procedures

Participants completed a variety of questionnaires assessing demographic information and health behaviors during one, in-person research session. The session was conducted within either the Syracuse VA Medical Center or Rochester VA Outpatient primary care clinics and lasted approximately one hour. Participants were compensated 15 US-dollars for their time. Funding for this study was provided by the Center for Integrated Healthcare at the Syracuse VA Medical Center. All procedures were approved by the Syracuse VA Medical Center Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent prior to participation.

Measures

Demographic Questionnaire

Participants answered questions regarding their demographic information (e.g. age, race, marital status, education level, and annual household income).

Patient Health Questionnaire—9 26 (PHQ-9)

This is a 9-item, self-report measure assessing the frequency of symptoms of depressed mood over the past 2 weeks (ranging from 0, or not at all, to 3, or nearly every day). Item #3 of this measure (PHQ item-3) asks the patient to rate how often he/she has had, “Trouble falling or staying asleep, or sleeping too much,” assessing the frequency of both insomnia and hypersomnia, which are symptoms of depression.27

Insomnia Severity Index 27 (ISI)

This is a 7-item, self-report measure assessing the presence and severity of insomnia symptoms, as well as the effect of sleep disturbance on daily functioning. The ISI has been validated in adults31 and found to adequately assess the diagnostic criteria for insomnia.32 Items are rated on a Likert-type scale ranging from 0 to 4, with higher scores reflecting more sleep disturbance. Scores on this measure are summed and may be categorized into 4 levels of insomnia severity: 0–7 indicates no clinically significant insomnia, 8–14 indicates the presence of subthreshold insomnia symptoms, 15–21 indicates the presence of moderate insomnia symptoms, and 22–28 indicates severe insomnia symptoms.27,33 Thus, participants with a score of 8 or higher on this measure were classified as scoring positive for insomnia symptoms. We chose a cutoff of 8 to capture people with subthreshold symptoms because screening measures are useful not only to identify patients who already have a diagnosis, but those who have subthreshold symptoms, and who could still benefit from an intervention to prevent the full development of the disorder.

Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test—Consumption30 (AUDIT-C)

The AUDIT-C is a summed score of the first three items of the AUDIT34 a 10-item questionnaire used to assess symptoms of alcohol use disorders. Items are scored on a 0–4 point scale, with higher scores indicative of a greater likelihood of an alcohol use disorder. The AUDIT-C30 is the summed score of the consumption questions of the AUDIT, which assess quantity and frequency of drinking and binge episodes (6 or more drinks on one occasion).

Primary Care—Post Traumatic Stress Disorder35 (PC-PTSD)

The PC-PTSD is a 4-item questionnaire assessing the presence of the following post-traumatic symptoms in the past month: re-experiencing, avoidance, hypervigilance, and emotional numbing related to past trauma. This measure has demonstrated strong diagnostic efficiency35,36.

Statistical Analyses

After confirming normality in variable distribution, Pearson correlations were computed across all variables pertinent to the analyses (e.g., PHQ-item 3, ISI total score, AUDIT-C, PTSD scores) and demographic variables (e.g., age, marital status, education, and income), which have been found to be associated with insomnia symptoms.3,37,38 (Categorical variables were dummy coded). Next, false negative (i.e., number of people who endorsed no sleep problems on the PHQ item-3 but who scored positive for insomnia symptoms on the ISI) and false positive (i.e., the number of people who endorsed sleeping problems on the PHQ item-3 but who did not screen positive for insomnia on the ISI) rates were calculated. Positive predictive values (i.e., dividing true positives (those scoring an 8 or higher on the ISI) by the sum of true and false positives multiplied by 100) and negative predictive values (dividing true negatives (those scoring a 7 or below on the ISI) by the sum of true and false negatives) were then calculated. Specificity was calculated as the number of participants who were correctly identified as having no sleep problems on the PHQ item-3 divided by the total number of participants without insomnia as indicated by a score less than 8 on the ISI, multiplied by 100. Thus, this statistic yields a percentage of people correctly identified by the PHQ item-3 as not having insomnia, or the PHQ item-3’s ability to identify true negatives. Sensitivity was calculated as the number of participants correctly identified as having insomnia by way of the PHQ item-3 divided by the total number of participants with insomnia as measured by the ISI multiplied by 100. Thus, this statistic yields a percentage of people correctly identified by the PHQ item-3 as having insomnia, or its ability to identify true positives. Lastly receiver operating curve (ROC) analysis was used to compare the PHQ item-3 with the presence or absence of sleep disturbance as assessed by the ISI.

RESULTS

Participants in this study had a mean age of 60.62 (SD = 17.04), and the large majority of patients were male (98.2%, n = 111). Due to the low number of females and the known association between gender and insomnia symptoms,39,40 the two females were excluded from the analyses. Thus, the final sample consisted of 111 males with a mean age of 60.80 years (SD = 17.13), and was predominantly Caucasian (89.2%; n = 99). All variables were normally distributed, and sample characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Characteristic | Mean (SD) or %(n); N = 111 |

|---|---|

| Age | 60.80 (17.13) |

| Race | |

| White | 89.19 (99) |

| Black | 8.11 (9) |

| Other | 2.70 (3) |

| Marital Status | |

| Single, never married | 18.92 (21) |

| Married | 53.15 (59) |

| Separated/Divorced | 22.52 (25) |

| Widowed | 5.41 (6) |

| Education | |

| High school or below | 31.53 (35) |

| Some College/College Degree | 54.95 (61) |

| Advanced Degree | 13.51 (15) |

| Annual Income | |

| < $20,000 | 19.82 (22) |

| $20,000 - $39,999 | 31.53 (35) |

| $40,000 - $59,999 | 26.13 (29) |

| > $60,000 | 22.53 (25) |

| AUDIT-C positive (≥4) | 89.18 (99) |

| PHQ-9 item 3 | 0.59 (0.86) |

| Insomnia Score (ISI total) | 5.77 (6.13) |

| ISI positive (≥8) | 36 (40) |

| Depression Score (PHQ-9 total) | 2.90 (4.02) |

| PTSD Score | 0.77 (1.30) |

Pearson correlation analyses revealed a strong,41 significant, positive correlation between the PHQ item-3 and ISI total score (r = 0.75, p < 0.0001). Age significantly correlated with both the PHQ item-3 (r = −0.28, p < 0.01) and the ISI (r = −0.35, p < 0.001) such that younger individuals had more sleeping difficulties than older individuals. Correlations are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Correlation Matrix of All Variables

| Variable (p-value) | ISI Total Score | PHQ item-3 | AUDIT-C Score | PC-PTSD Score | Age | Race | Marital Status | Education Level | Annual Income |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ISI Total Score | 1.00 | 0.75 (<0.0001) | 0.12 (0.19) | 0.46 (<0.0001) | −0.35 (<0.0001) | −0.25 (0.007) | −0.41 (<0.0001) | −0.02 ( 0.86) | −0.02 (0.84) |

| PHQ item-3 | – | 1.00 | 0.10 (0.28) | 0.42 (<0.0001) | −0.28 (0.003) | −0.13 (0.17) | −0.32 (0.0006) | 0.09 (0.32) | −0.002 (0.98) |

| AUDIT-C Score | – | – | 1.00 | 0.18 (0.05) | −0.47 (<0.0001) | −0.10 (0.29) | −0.09 (0.33) | −0.05 (0.57) | −0.05 (0.62) |

| PC-PTSD Score | – | – | – | 1.00 | −0.36 (<0.0001) | −0.04 (0.67) | −0.11 (0.23) | 0.08 (0.40) | 0.05 (0.60) |

| Age | – | – | – | – | 1.00 | 0.15 (0.12) | 0.36 (<0.0001) | −0.05 (0.58) | 0.11 (0.27) |

| Race | – | – | – | – | – | 1.00 | 0.19 (0.04) | 0.17 (0.07) | 0.11 (0.27) |

| Marital Status | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.00 | 0.14 (0.13) | 0.34 (0.0003) |

| Education Level | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.00 | 0.13 (0.17) |

| Annual Income | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.00 |

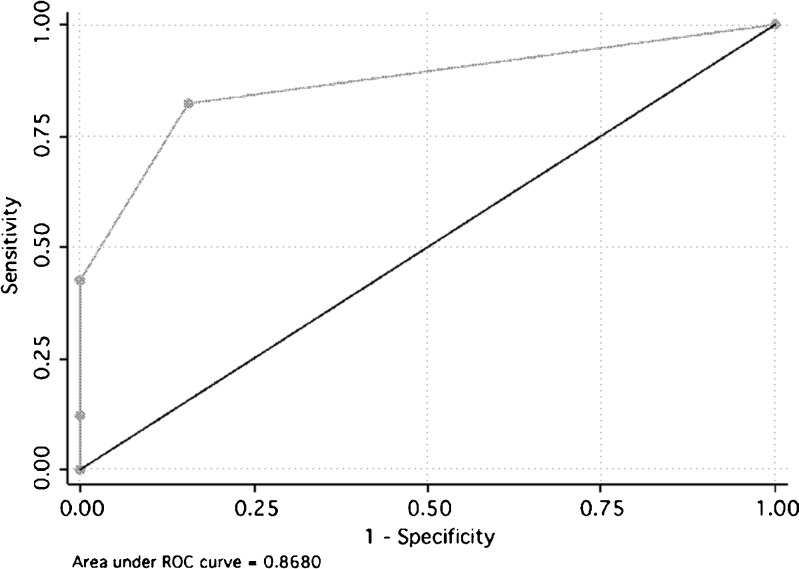

Summary statistics for positive and negative predictive value, sensitivity, and specificity are presented in Table 3. Of note, a cut score of 1, indicating sleep difficulty on several days or more in the last two weeks on the PHQ item-3 demonstrated the best balance of false negative and false positive rates with 7 and 11, respectively, as well as the best sensitivity (82.5%) and specificity (84.5%) rates. It also demonstrated the best balance of positive and negative predictive values at 78.4% and 91% respectively. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) for the PHQ item-3 plotted against an ISI positive score was 0.87 (95% CI = 0.80 to 0.94) (see Fig. 1).

Table 3.

Specificity and Sensitivity Statistics at Each PHQ-3 Cutoff Score

| ISI Score | PHQ-item #3 cutoff | Positive Predictive Value | Negative Predictive Value | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8 or above | 1 or above (several days or more) | 78.4% | 91% | 82.5% | 84.5% |

| 8 or above | 2 or above (more than half the days) | 100% | 75.5% | 42.5% | 100% |

| 8 or above | Score of 3 (nearly every day) | 100% | 70% | 12.5% | 100% |

Figure 1.

Area under the receiver operating curve.

Post Hoc Analyses

Correlation analyses revealed a negative relationship between age and sleep difficulties on both sleep indices, which is contrary to the literature stating older individuals tend to have more sleep difficulties.42,43 As such, we conducted a post hoc linear regression analysis to determine whether the fact that most participants in this sample were regular drinkers could account for the negative relationship between sleep difficulties and age. In this analysis, ISI total score served as the dependent variable with the PHQ item-3 serving as the independent variable. Age, AUDIT-C score, and the demographic variables served as covariates. Results revealed that the PHQ item-3 significantly predicted ISI total score (β = 5.08, p < 0.0001). After covarying for alcohol use, age was still a significant negative predictor of sleep problems (β = −0.06, p < 0.05). Neither alcohol use nor demographic variables significantly predicted sleep difficulty.

We also examined whether PTSD symptoms could explain the negative relationship between age and sleep difficulty because PTSD symptoms have a known association with sleep difficulty44 and were significantly correlated with both sleep indices and age in our sample (see Table 2). Thus, we conducted an additional linear regression analysis using ISI total score as the dependent variable, PHQ item-3 as the independent variable, and age, AUDIT-C score, PC-PTSD score, and the demographic variables as covariates. After adding PTSD symptoms to the model, age no longer significantly predicted sleep difficulties (β = −0.03, p = 0.34).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that item 3 of the PHQ-9 is a potentially effective screener to identify sleep disturbance in VA primary care settings. Specifically, our results show that a cut score of 1 on the PHQ item-3 (indicating sleep problems several days in the last 2 weeks) provides the best balance of sensitivity and specificity, such that 82.5% of patients with sleep disturbance were correctly identified while 84.5% of patients without sleep difficulty were correctly ruled out using the PHQ item-3.

These results are particularly promising given the current recommended use of the PHQ-9 in primary care settings.26 The implication of these results is that PCPs may screen for sleep disturbances without implementing a separate, sleep-specific measure. Instead, should a patient endorse a 1 or higher on item 3 on the PHQ-9, it could signal to the provider to further assess the patient’s sleep and intervene if necessary. Sleep interventions are effective in both improving sleep in primary insomnia patients,3,13,45 as well as in patients who are experiencing insomnia and other sleep disturbances comorbid with other disorders.46–50 Furthermore, preliminary studies suggest that improving sleep quality may also improve symptoms of other physical and mental health disorders associated with insomnia,51–53 further emphasizing the importance of identifying and treating this, and potentially other common sleep disturbances.

It is of note that while the ISI has been found to adequately assess the diagnostic criteria for insomnia,27 it does not provide a valid diagnosis for insomnia or any other sleep problem. Additionally, the established ISI cutoff score of 8 includes insomnia symptoms that may be considered ‘mild’ or subthreshold.27 However, it was important to capture those patients with mild/subthreshold sleep problems with the ISI to test the PHQ item-3’s efficacy at identifying patients with subthreshold symptoms as well as a potential sleep disorder. The PHQ item-3 performed well in this capacity, as evidenced by its high level of sensitivity (82.5%), which is particularly important in a screening measure.54

Although this study is an important first step in the validation of the PHQ item-3 as an effective screening tool in primary care, our results should be interpreted in the context of some important limitations. Our sample consisted of male veterans from two Upstate New York VA clinics, where the majority of the sample was between 44 and 78 years of age, and drank regularly, which could reduce the generalizability of our findings. Future work in this area should include studies conducted in non-VA primary care clinics, in samples diverse enough to address generalizability across gender, age, race, and health care settings. Future studies should also include both drinkers and non-drinkers given the known relationship between alcohol and sleep.55

An additional important limitation is that PHQ item-3 assesses both insomnia and hypersomnia and we only validated it against an insomnia instrument. It remains to be seen to what extent false positives are related to endorsing the PHQ sleep item due to hypersomnia and whether these may represent true cases of hypersomnia requiring treatment. The latter is particularly important given that the most common sleep disorder with hypersomnia as a feature, sleep apnea, is a significant concern in primary care and associated with multiple health risks.56–58 If the PHQ item performs reasonably well in detecting cases of sleep apnea, it could prove to be a very efficient tool for identifying the two most common forms of sleep disorders (insomnia and sleep apnea).

Though not the focus of the paper, the significant negative relationship between age and sleep in this sample warrants further discussion. This finding is in contrast with a wealth of literature stating that, as people age, their sleep worsens.42,43 Alcohol intake did not account for this relationship in this sample, which is unexpected, given the close relationship between alcohol and sleep,55 and the fact that most people in our sample were regular drinkers. Rather, our post hoc analyses revealed that, once PTSD symptoms were added to the regression model, the significant relationship between age and sleep went away. This finding is not surprising given the significant correlation between PTSD symptoms and age in our sample and the literature demonstrating that PTSD symptoms disrupt normal sleep 44

Overall, this study is an important first step in the validation of the PHQ item-3 as an effective sleep screen for primary care. The PHQ item-3 is brief, and does not require an additional screen to primary care providers, who are already burdened with many annual screens. Particularly in settings already using the PHQ-9, this can be an incredibly efficient use of resources. Pulling out and focusing on the PHQ item-3 could help providers to more readily identify insomnia and potentially other sleep disturbances in their patients. Ultimately, identifying sleep disturbance is the gateway to interventions with demonstrated efficacy and to the common goal of improving their overall health and quality of life.

Acknowledgments

Contributors

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not reflect the official policy of the Veteran’s Affair’s department or other departments of the U.S. government. We acknowledge the Center for Integrated Healthcare, Syracuse VA Medical Center (VAMC) who contributed support to this research study.

Funders

This material is based upon work supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, and the Center for Integrated Healthcare.

Prior Presentations

The material discussed in this paper has not been a part of any prior presentations.

Conflict of Interest

None disclosed.

References

- 1.Alattar M, Harrington JJ, Mitchell CM, Sloane P. Sleep problems in primary care: a North Carolina Family Practice Research Network (NC-FB-RN) study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;20:365–74. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2007.04.060153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Karachaliou F, Kostikas K, Pastaka C, Bagiatis V, Gourgoulianis KI. Prevalence of sleep-related symptoms in a primary care population—their relation to asthma and COPD. Prim Care Respir J. 2007;16:222–8. doi: 10.3132/pcrj.2007.00045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leshner A, Baghdoyan H, Bennett S, et al. Final statement from the NIH “State-of-the-Science Conference” on manifestations and management of chronic insomnia in adults Sleep 2005281049–1057.16268373 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simon GE, VonKorff M. Prevalence, burden and treatment of insomnia in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1417–1423. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.10.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pigeon WR, Heffner K, Duberstein P, et al. Elevated sleep disturbance among blacks in an urban family medicine practice. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24:161–8. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.02.100028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shochat T, Umphress J, Israel AG, Acoli-Israel S. Insomnia in primary care patients. Sleep. 1999;22(Suppl 2):S359–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Partinen M, Hublin C. Epidemiology of sleep disorders. In: Kryger M, Roth T, Dement W, editors. Principles 7 practice of Sleep medicine 5th Edition. St. Louis: Elsevier; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasler G, Buysse DJ, Gamma A, et al. Excessive daytime sleepiness in young adults: a 20-year prospective community study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:521–9. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v66n0416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Katz DA, McHorney CA. The relationship between insomnia and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic illness. J Fam Pract. 2002;51:229–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Léger D, Guilleminault C, Bader G, Lévy E, Paillard M. Medical and socio-professional impact of insomnia. Sleep. 2002;15:625–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pigeon WR. Insomnia as a risk factor for disease. In: Sateia MJ, Buysse D, editors. Insomnia: diagnosis and treatment. New York: Informa Healthcare; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rakel RE. Clinical and societal consequences of obstructive sleep apnea and excessive daytime sleepiness. Postgrad Med. 2009;121:86–95. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2009.01.1957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roth T, Franklin M, Bramley TJ. The state of insomnia and emerging trends. Am J Manag Care. 2007;13:S117–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skaer TL, Sclar DA. Economic implications of sleep disorders. Pharmacoeconomics. 2010;28:1015–23. doi: 10.2165/11537390-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fullerton DS. The economic impact of insomnia in managed care: a clearer picture emerges. Am J Manag Care. 2006;12(8 Suppl):S246–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hillman DR, Murphy AS, Pezzullo L. The economic cost of sleep disorders. Sleep. 2006;29:299–305. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ozminkowski RJ, Wang S, Walsh JK. The direct and indirect costs of untreated insomnia in adults in the United States. Sleep. 2007;30:263–73. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.3.263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tubtimtes S, Sukying C, Prueksaritanond S. Sleep problems in out-patient of primary care unit. J Med Assoc Thai. 2009;92:273–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsh JK, Benca RM, Bonnet M, et al. Insomnia: assessment and management in primary care. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute working group on insomnia. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:3029–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doghramji PP. Detection of insomnia in primary care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(Suppl 10):S18–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morin CM, Hauri PJ, Espie CA, Spielman AJ, Buysse DJ, Bootzin RR. Nonpharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia. Sleep. 1999;22:1134–56. doi: 10.1093/sleep/22.8.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mitty E, Flores S. Sleepiness or excessive daytime somnolence. Geriatr Nurs. 2009;30:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boulos MI, Murray BJ. Current evaluation and management of excessive daytime sleepiness. Can J Neurol Sci. 2010;37:167–176. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100009896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Preventive Services US. Task Force. Screening for depression in adults: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:784–792. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-11-200912010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nease DE, Jr, Malouin JM. Depression screening: a practical strategy. J Fam Practice. 2003;52:118–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morin CM. Insomnia: psychological assessment and management. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Veteran’s Health Administration, Available at http://vaww4.va.gov/vhaopp/VHA_OP_Plan/2011_13/Improve_Veterans_mental_health.pdf. Accessed on December 16, 2010

- 29.Tew J, Klaus J, Oslin DW. The behavioral health laboratory: building a stronger foundation for the patient-centered medical home. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28:130–45. doi: 10.1037/a0020249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bush KR, Kivlahan DR, McDonnell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking: Ambulatory Care Quality Improvement Project (ACQUIP): alcohol use disorders identification test. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:1789–95. doi: 10.1001/archinte.158.16.1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM. Validation of the ISI as an outcome measure for insomnia severity. Sleep Med. 2001;2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9457(00)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.WHO. International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Health Related Problems, ICD-10. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000.

- 33.Morin CM, Belleville G, Belanger L, Ivers H. The insomnia severity index: psychometric indicators to detect insomnia cases and evaluate treatment response. Sleep. 2011;34:601–8. doi: 10.1093/sleep/34.5.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption-II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prins A, Ouimette P, Kimerling R, et al. The primary care PTSD screen (PC-PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Primary Care Psychia. 2003;9:9–14. doi: 10.1185/135525703125002360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bliese PD, Wright KM, Adler AB, et al. Validating the Primary Care Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Screen and the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist with soldiers returning from combat. J Consult Clin Psych. 2008;76:272–81. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fetveit A. Late-life insomnia: a review. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2009;9:220–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0594.2009.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neikrug AB, Ancoli-Israel S. Sleep disorders in the older adult—a mini review. Gerontology. 2010;56:181–9. doi: 10.1159/000236900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Krishnan V, Collop NA. Gender differences in sleep disorders. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12:383–9. doi: 10.1097/01.mcp.0000245705.69440.6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Peretti-Watel P, Legley S, Baumann M, et al. Fatigue, insomnia, and nervousness: gender disparities and roles of individual characteristics and lifestyle factors among economically active people. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2009;44:703–9. doi: 10.1007/s00127-008-0487-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cohen, J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1988.

- 42.Bliwise DL, King AC, Harris RB, Haskell WL. Prevalence of self-reported poor sleep in a healthy population aged 50–65. Soc Sci Med. 1992;34:49–55. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(92)90066-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohayon MM, Carskadon MA, Guilleminault C, Vitiello MV. Meta-analysis of quantitative sleep parameters from childhood to old age in healthy individuals: developing normative sleep values across the human lifespan. Sleep. 2004;27:1255–73. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.7.1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mellman TA. Sleep and posttraumatic stress disorder: a road map for clinicians and researchers. Sleep Med Rev. 2008;12:165–7. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2008.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morin CM, Culbert JP, Schwartz SM. Nonpharmacological interventions for insomnia: a meta-analysis of treatment efficacy. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151:1172–80. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.8.1172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Berger AM, Kuhn BR, Farr LA, et al. One-year outcomes of a behavioral therapy intervention trial on sleep quality and cancer-related fatigue. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:6033–40. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.8306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Currie SR, Wilson KG, Pontefract AJ, Laplante L. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of insomnia secondary to chronic pain. J Consult Clin Psych. 2000;68:407–16. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.3.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Edigner JD, Wohlgenuth WK, Krystal AD, Rice JR. Behavioral insomnia therapy for fibromyalgia patients. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2527–35. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.21.2527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edinger JD, Olsen MK, Stechuchak KM, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for patients with primary insomnia or insomnia associated predominately with mixed psychiatric disorders: a randomized clinical trial. Sleep. 2009;32:499–510. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.4.499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ulmer CS, Edinger JD, Calhoun PS. A multi-component cognitive-behavioral intervention for sleep disturbance in veterans with PTSD: a pilot study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7:57–68. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fava M, McCall WV, Krystal A, et al. Eszopiclone co-administered with fluoxetine in patients with insomnia coexisting with major depressive disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;59:1052–60. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Junquist CR, O’Brien C, Matteson-Rusby S, et al. The efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia in patients with chronic pain. Sleep Med. 2010;11:302–9. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.05.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Manber R, Edinger JD, Gress JL, et al. Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia enhances depression outcome in patients with comorbid major depressive disorder. Sleep. 2008;31:489–495. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.4.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bewick V, Cheeck L, Ball J. Statistics review 13: receiver operating characteristic curves. Crit Care. 2004;8:508–512. doi: 10.1186/cc3000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stein MD, Friedmann PD. Disturbed sleep and its relationship to alcohol use. Subst Abus. 2005;26:1–13. doi: 10.1300/J465v26n01_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bliwise DL. Sleep apnea, APOE4 and Alzheimer’s disease 20 years and counting? J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:539–46. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3999(02)00436-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pamidi S, Aronsohn RS, Tasali E. Obstructive sleep apnea: role in the risk and severity of diabetes. Best Pract Res Cl. 2010;24:703–15. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2010.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Reishtein JL. Obstructive sleep apnea: a risk factor for cardiovascular disease. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2011;26:106–16. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181e3d724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]