Abstract

Infection with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) that causes acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is still rising globally. In order to develop effective HIV/AIDS risky behavior reduction intervention strategies and to further decrease the spread of HIV/AIDS, it is important to assess the prevalence of psychosocial problems and HIV/AIDS risky behaviors in people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). The objective of this study is to assess the relationship between psychosocial variables and HIV/AIDS risky behaviors among PLWHA. A total of 341 questionnaires were distributed and 326 were fully completed and returned, 96% response rate. The relationships between the identified psychosocial and HIV/AIDS risky behaviors among PLWHA were analyzed using The Moment Structures software version 17.0 (SPSS Inc.) The results indicate that psychosocial health problems were significant predictors of HIV/AIDS risky behaviors in PLWA. Further cross-disciplinary research that addresses the manner in which psychosocial problems and HIV/AIDS risky behaviors interact with each other among PLWHA is needed.

Keywords: Relationships, psychosocial factors, HIV/AIDS, risky behaviors, people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA)

INTRODUCTION

People living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) are known to have great emotional needs and require enormous support for coming to terms with dire affliction status. Some of the feelings that PLWHA experience include, shock or anger at being positively diagnosed with HIV, fear over how the disease will progress, fear of isolation by family and friends, and worries about infecting others. By bearing such a heavy emotional burden it is not surprising that depression is twice as common in PLWHA compared to the general population (American Psychiatric Association, 2008). In addition to being a disease that is associated with a number of physical malfunctions and progressive discomforts like pain, shortness of breath, altered sexual functioning and disfigurement, HIV/AIDS is also still a highly stigmatized disease. This stigmatization can lead to a progression of other grievous psychosocial stressors including unemployment, homelessness, financial doldrums and the breakup of relationships. These, in turn, can cause further depression along with a number of other psychosocial problems (Desquilbet et al., 2002).

Psychosocial problems have also been associated with HIV/AIDS-risky behaviors, non-adherence to HIV/AIDS related medications, and shortened survival rates (Farinpour et al., 2003; Cook et al., 2004). Despite the prevalence of psychosocial distress experienced by PLWHA, the available body of evidence indicates that depression is frequently under diagnosed and goes untreated on a large scale. For example, in the USA, a large cohort study of patients undergoing care for HIV/AIDS found out that nearly half of those who met the criteria for major depression had no mention of such a diagnosis in their medical records (Asch et al., 2003); and one-third of the PLWHA who needed psychosocial health information services were not receiving them (Taylor et al., 2004).

A number of studies of patients who seek HIV/AIDS treatment or preventive health services have indicated that there is fairly high prevalence of psychosocial problems including depression, anxiety, and hostility (Kalichman, 2000; Cohen et al., 2002). Other research shows that psychosocial variables, such as depression and other mental health problems, drug or alcohol addictions, or any combination of these are most commonly prevalent among PLWHA (Moore et al., 2008; Wyatt et al., 2002; Whetten et al., 2006). It is estimated that up to 50% of PLWHA suffer from a mental illness, such as depression, and 13% have both mental illness and substance abuse issues (Bing et al., 2001). In the same by Bing and colleague also indicated that one-half of adults of PLWHA had symptoms of a psychiatric disorder; 19% had signs of substance abuse; 13% had co-occurring substance abuse and mental illness (Bing et al., 2001); and one-half of PLWHA had depression (Lesser, 2008).

The question of exactly how HIV/AIDS causes depression has sparked off a lot of controversies. Some of these support the “pre-infection psychopathology” argument, and feel that HIV/AIDS merely acts as a trigger and that only people with a vulnerability to depression before contracting HIV/AIDS become depressed. Others believe in the ability of the HIV/AIDS to create depressive syndromes (Desquilbet et al., 2002). The argument that HIV/AIDS creates depression in people who formerly had no history of the illness, seems more feasible. This can occur in a number of different ways, the first being the argument of social stress. The stigmatization, alienation and breakdown of social support systems contribute greatly to the feelings of helplessness experienced by people affected with HIV/AIDS. After the knowledge of their HIV positive status, many overreact and think that this is it; they are going to die very soon. It is mainly for this reason that many people may develop depression and lose interest in aspects of life that used to be important to them before knowledge of their HIV positive status.

In a study by Komiti and colleagues (2005) it has been indicated that psychosocial problems were among the most commonly observed health problems among PLWHA, affecting up to 20% of them and that the prevalence may have been even greater among substance users. Psychosocial problems have also been associated with HIV/AIDS risky behaviors, non-adherence to medications, and shortened survival rates (Farinpour et al., 2003; Cook et al., 2004). In addition, at times, depression is noted to be often linked with major causes of HIV transmission. These include alcohol consumption before sex, unprotected sexual contact, intravenous drug use, the sharing of HIV contaminated syringes and needles, and (Saylors and Daliparthy, 2005; Luber, 2002). In a national probability sample of nearly 3,000 PLWHA assessed by Bing and colleagues (2001), they found out that that more than one-third of them screened positive for clinical depression and half of them reported use of illicit drugs. In another screening study carried out by Pence and colleagues (2007), they found relatively similar levels of depression of 35% in PLWHA that had screened positive. Additionally, studies have indicated higher rates of depression symptoms, ranging between 26 and 49%, in HIV-positive people compared with HIV-negative control groups (Boarts et al., 2006; Spiegel et al., 2003; Pence et al., 2006).

Factors such as alcohol consumption before sex, unprotected sexual contact, intravenous drug use, and sharing HIV contaminated syringes needles are the major causes for HIV transmission (American Psychiatric Association, 2008). A lot of information about HIV/AIDS prevention efforts and awareness campaigns against the spread of HIV infection is already abundantly available for PLWHA and for the general public. Despite the vast knowledge of how HIV is transmitted, many PLWHA still continue to engage in HIV/AIDS risky behaviors that also further places them to risks contracting secondary infections (e.g., syphilis, gonorrhea, herpesvirus-6) that may accelerate HIV/AIDS (Angelino, 2002).

However, study findings have been inconsistent about the relationship existing between psychosocial problems and high HIV/AIDS risky behaviors. Some studies have failed to find any such relationship (Kalichman, 1999) while others have demonstrated a negative relationship that exists between psychosocial problems and high HIV/AIDS risky behaviors (Robins et al., 1994).

The inconsistency in these research findings may be related to the fact that the specific link between HIV/AIDS and psychosocial problems is still not clearly distinct.

A clear understanding of how psychosocial problems are likely to operate in HIV-infected individuals and impact their ability to consistently act rationally is very useful for a full understanding of high-risk sexual behaviors among PLWHA. Two psychosocial problems believed to be clearly associated with HIV/AIDS risky behaviors were identified. These were depression and the loss of interest in aspects of life that used to be important before PLWHA knew of HIV positive status. These two identified major psychosocial problems which are prevalent among PLWHA (Cohen et al., 2002) have been shown to influence sexual-risk taking and HIV transmission (UNAIDS, 2007). Failure to recognize the prevalence of psychosocial problems and associated HIV/AIDS risky behaviors among PLWHA may therefore endanger both the afflicted people with HIV/AIDS and others un-afflicted members in the community. The objective of this study is to determine if significant correlations exist between psychosocial problems and HIV/AIDS risky behaviors among PLWHA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design

The data was collected by a survey questionnaire instrument of HIV positive clients of a community based HIV/AIDS outreach facility (CBHAOF) located in Montgomery, Alabama. The CBHAOF provides community based HIV/AIDS treatment and prevention services through education, quality services and compassionate care to HIV/AIDS afflicted clients and their families in 27 counties in Alabama. The CBHAOF has also a medical component or clinic which provides complete primary health care that includes physician visits, and laboratory tests for diagnosing HIV infection. The questionnaire was designed to collect data on behaviors that could be associated with HIV transmissions in the Black Belt Counties (BBC) of Alabama. The BBC of Alabama are the counties which stretch centrally from west to southeast Alabama. The BBC are counties which have a higher percentage (more than 50%) of African American residents compared to Whites. The questionnaire was pretested in collaboration with CBHAOF to assess whether the materials were understandable to the target respondents and could easily be answered by them. Tuskegee University’s Institutional Review Board approved the final questionnaire, informed consent forms and study protocol. The major modules of the questionnaire included: socioeconomic and demographic information; knowledge about HIV/AIDS, HIV testing, substance use, and HIV/AIDS risky behaviors of PLWHA before and after the knowledge of their HIV positive status. Participants filled out a questionnaire anonymously without any individual identifying information.

Data collection procedures

The data was collected in collaboration with CBHAOF. The questionnaires and the informed consent forms were given to the facility staff for administration and retrieval. The defined criteria to enroll participants in the study included: age equal to or greater than 18 years, and having been diagnosed as being HIV positive. A convenience sampling method was used to select the study sample. Eligible participants were informed about the study by the facility’s staff during their regular medical visits. Each participant was actively approached at the end of his/her visit by the trained interviewers to explain the goals of the study and request his/her consent to participate in it. Although a convenience sampling method was used, almost all the clients who were approached were eligible and agreed voluntarily to participate. Participants agreed to participate in the survey in two ways. These were by either signing and returning the consent form before filling the questionnaire or by directly filling the questionnaire. Participant’s names were not included in the questionnaire, thus maintaining their confidentiality and privacy.

The participants completed the questionnaire during their clinical visits to the clinic at their own convenience and that of the facility’s staff. The facility staff administered and retrieved the questionnaires at its clinical sites. A total of 341 questionnaires were distributed and 326 questionnaires were fully completed and returned (a response rate of 96%). The other 15 questionnaires (a refusal or dropout rate of 4%) were also returned but were not fully completed and as a consequence they were destroyed and were not used in the analysis. Each completed questionnaire was retrieved in a sealed envelope to the CBHAOF staff. Upon receiving the completed questionnaire from the participant, the CBHAOF staff gave each participant a Wal-Mart coupon worth $15.00, which was provided by the Tuskegee University as an incentive token and compliment for filling out the questionnaire voluntarily. Researchers at the Center for Computational Epidemiology, Bioinformatics and Risk Analysis (CCEBRA), a research team of Biomedical Information Management Systems in the College of Veterinary Medicine, Nursing and Allied Health of Tuskegee University, collected the completed questionnaires from the CBHAOF staff. All completed questionnaires were kept in a secured and locked location. Data were entered into FileMaker Pro 6.0v4 by qualified personnel of CCEBRA.

Measures

Dependent measures (variables)

The two dependent variables selected for use in this study were psychosocial health factors and HIV/AIDS risky behaviors. The two indicators of poor psychosocial health factors were lost interest in aspects of life that used to be important, and depression. Lost interest in aspects of life was measured by asking participants the question “Do you lose interest in aspects of life that used to be important to you?” The responses categories were “yes” or “no” as the answers. Depression was measured by asking participants the question “Do you feel depressed, worried, or tired? The responses categories were “yes”, “no” and “don’t know” as the answers. Participants with poor psychosocial health were defined as participants who answered “yes” to the two referred questions.

The four measures of HIV/AIDS risky behaviors considered for PLWHA were: number of sexual partners (within one year, one month and one week); and their condom use. Number of sexual partners within one year, one month and one week was measured by asking participants the question: “How many people have you had sexual intercourse within one year?” “How many people have you had sexual intercourse within one month?” and “How many people have you had sexual intercourse within one week?” respectively. The response categories included “one person” “two people” “three people” “four people” “five people” six people” and “none” as the answers. Those having more than one sexual partner were considered to be at a higher risk. Condom use was measured by asking participants the question: “Did you use a latex condom the last time you had sexual intercourse?” The response categories included: “yes” or “no” as the answers. Participants with high HIV/AIDS risky behaviors were defined as those participants who answered “no” to the question.

Independent measures (variables)

The independent measure was knowledge of HIV/AIDS positive status by the PLWHA.

Main outcome measures

The outcome measures included the prevalence of poor psychological health (lost interest in aspects of life that used to be important and depression) and the prevalence of HIV/AIDS risky behaviors (multiple sexual partners and inconsistent use of condoms during sexual intercourse encounters).

Statistical analyses

A path analysis model was used to examine the relationships between all the variables of the hypothesized model using AMOS software (Analysis of Moment Structures) version 17.0 (Arbuckle et al., 1999). A structural equation modeling techniques (Mueller, 1996) was used to examine the interrelationships among HIV/AIDs risky behavior variables. Structural equation modeling is able to capture complex relationships among multiple variables by assessing the strength of these relationships with respect to selected dependent variables. AMOS is designed for structural equation modeling and path analysis, as well as to perform linear regression analysis and Analysis of Variance (ANOVA). AMOS has been used by Rho (2005) and Arbuckle (1999) for statistical analysis in other surveys. AMOS accepts a path diagram as a model specification and displays parameter estimates graphically on a path diagram. It features an intuitive graphical interface that allows the analyst to specify models by drawing them. AMOS also has a built-in bootstrapping routine and superior handling of missing data. It reads data from a number of databases, including MS Excel spreadsheets and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) databases.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows a summary of the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of the participants by number and percentages in relation to their sex, race, age group, marital status, level of education and level of income.

Table 1.

Number and percentage of respondents by sex, race, age group, marital status, employment status, level of education and level of income.

| Demographic and social economic characteristics | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Female | 136 | 42 |

| Male | 181 | 56 | |

| Transgender | 4 | 1 | |

| Transsexual | 5 | 2 | |

| Race | African American | 208 | 64 |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 94 | 29 | |

| Hispanic | 10 | 3 | |

| Other races | 14 | 4 | |

| Age group | 18–29 | 53 | 19 |

| 30–39 | 86 | 30 | |

| 40–49 | 104 | 37 | |

| 50–59 | 34 | 12 | |

| 60 and above | 6 | 2 | |

| Marital Status | Single | 183 | 56 |

| Married | 47 | 15 | |

| Divorced | 47 | 15 | |

| Separated | 31 | 10 | |

| Widow(er) | 3 | 1 | |

| Other | 13 | 4 | |

| Employment Status | Employed for wages | 122 | 39 |

| Unable to work | 59 | 19 | |

| Unemployed | 50 | 16 | |

| Student | 25 | 8 | |

| Homemaker | 25 | 8 | |

| Self-employed | 18 | 6 | |

| Retired | 12 | 4 | |

| Level of education | Graduate school | 11 | 3 |

| College 4 years or more | 50 | 15 | |

| College 1 year to 3 years | 85 | 26 | |

| Level of income | $9,999 or under | 97 | 31 |

| $10,000 to $14,999 | 45 | 14 | |

| $15,000 to $19,999 | 38 | 12 | |

| $20,000 to $24,999 | 36 | 11 | |

| $25,000 to $29,999 | 23 | 7 | |

| $30,000 to $49,999 | 20 | 6 | |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 13 | 4 | |

| Don’t know | 46 | 14 | |

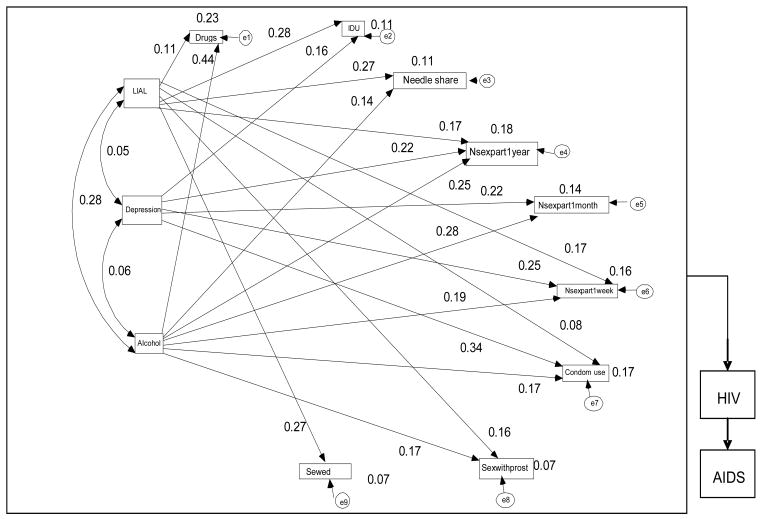

Table 2 and Figure 1 indicate standardized regression weights for selected psychosocial factors regarding HIV/AIDS-risky behaviors among PLWHA. The participants who indicated that they had lost interest in aspects of life that were important before knowing that they were HIV positive status is significantly related to the use of drugs before sex. Table 2 shows the details of the total effects’ standardized regression coefficients and their corresponding p values.

Table 2.

The relationships between selected psychosocial variables and HIV/AIDS risky behaviors among people living with HIV/AIDS.

| Variable | Total effects | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| The relationship between lost interests in aspects of life that were important before knowledge of being HIV positive and | ||

|

| ||

| Using drugs before sex | 0.11 | 0.02 |

| Injecting drugs use (IDU) | 0.28 | <0.001 |

| Needle sharing (Needleshare) | 0.27 | <0.001 |

| Number of sexual partners within 1 year (Nsexpart 1 year) | 0.17 | 0.001 |

| Number of sexual partners within 1 week (Nsexpart 1 week) | 0.17 | 0.002 |

| Sex with prostitute (s) (Sexwithprost) | 0.16 | 0.004 |

| Sex with injection drug users (SexwIDU) | 0.27 | <0.001 |

| The relationship between depression and | ||

| Injection drug users | 0.16 | 0.002 |

| Number of sexual partners within 1 year | 0.22 | <0.001 |

| Number of sexual partners within 1 month | 0.22 | <0.001 |

| Number of sexual partners within 1 week | 0.25 | <0.001 |

| Condom use | 0.34 | <0.001 |

| The relationship between drinking alcohol before sex and | ||

| Using drugs before sex | 0.44 | <0.001 |

| Needle sharing | 0.14 | 0.01 |

| Number of sexual partners within 1 year | 0.25 | <0.001 |

| Number of sexual partners within 1 month | 0.28 | <0.001 |

| Number of sexual partners within 1 week | 0.19 | <0.001 |

| Condom use | 0.17 | 0.001 |

| Sex with prostitutes | 0.17 | 0.003 |

Figure 1.

The path model indicating the direction of all relationships between selected psychosocial factors on HIV/AIDS risky behaviors among people living with HIV/AIDS (Double headed arrows represent correlations and single headed arrows represent standardized regression paths)

Figure 1 indicates path model results, using AMOS, for standardized regression weights between selected psychosocial variables and HIV/AIDS risky behaviors for significant paths (p < 0.05). Lost interest in aspects of life that used to be important before the participants knew of their HIV positive status and drinking alcohol before sex were positively related to using drugs before sex.

These predictors accounted for 23% (R2 = 0.23) of the variance in using drugs before sex. The results shown in Figure 1 indicate that the participants who lost their interest in aspects of life that used to be important to them before knowing that they were HIV positive and depression were positively related to using drugs intravenously. These predictors accounted for 11% (R2 = 0.11) of the variance in using drugs intravenously (Figure 1). Regression coefficients shown in Figure 1 show that lost interest in aspects of life that used to be important before establishing HIV infection status and drinking alcohol before sex were also positively correlated with sharing the same syringe/needle with other person to inject himself or herself. These predictors accounted for 11% (R2 = 0.11) of the variance in sharing the same syringe/needle with another person or other people to inject oneself (Figure 1). Further, three psychosocial variables including lost interest in aspects of life that used to be important to them before knowing that they were HIV positive, depression and drinking alcohol before sex appeared as the strong predictors with positive effects on the number of sexual partners within one year. These predictors accounted for 18% (R2 = 0.18) of the variance in the number of sexual partners within one year. In Figure 1 two direct paths of psychosocial factors (that is, depression and drinking alcohol before sex) displayed positive effect on the number of sexual partners within one month. These predictors accounted for 14% (R2 = 0.14) of the variance in the number of sexual partners within one month. The results illustrate that two HIV/AIDS risky behaviors (number of sexual partners within one week and condom use) were predicted by three psychosocial variables (lost interest in aspects of life that used to be important before knowing that they were HIV positive, depression and drinking alcohol before sex). These three psychosocial variables accounted for 16% (R2 = 0.16) and 17% (R2 = 0.17) of the variance in the number of sexual partners within one week and condom use respectively (Figure 1).

As indicated in Figure 1, the individual coefficients for the paths from two measures of psychosocial factors (lost interest in aspects of life that used to be important before knowing that they were HIV positive and drinking alcohol before sex) to sex with prostitute(s) are significant but the proportion of variance in the dependent variable (sex with prostitute) which can be predicted from the independent variables (lost interest in aspects of life that used to be important knowing that they were HIV positive and drinking alcohol before sex) is very small (R2 = 0.07). This value indicates that 7% of the variance in sex with prostitutes can be predicted from the variables lost interest in aspects of life that used to be important before knowing that they were HIV positive and drinking alcohol before sex. Lost interest in aspects of life that used to be important before knowing that they were HIV positive is also only 7% (R2 = 0.07) of the variance in sex with prostitute(s).

DISCUSSION

Even though HIV/AIDS related health outcomes have improved with the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy especially Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy (HAART), findings from this study confirmed the prevalence and the relationship between selected psychosocial and HIV/AIDS risky behavior variables. Specifically, three measures of psychosocial problems (lost interest in aspects of life, depression, and drinking alcohol) found in PLWHA were significantly related with certain HIV/AIDS risk behaviors. These include using drugs before sex, IDU, needle sharing, multiple sexual partners, sex with prostitutes, and sex with IDU. Consistent with these findings, many studies that have reported the prevalence of psychosocial problems not only to be common in PLWHA but related to high HIV/AIDS risky behaviors (Farinpour et al., 2003; Cook et al., 2004; Moore et al., 2008; Wyatt et al., 2002; Whetten et al., 2006).

The relationships between psychosocial variables and HIV/AIDS risky behaviors have been examined in other studies as well. For example, studies found that depressive symptoms led PLWHA to engage in high HIV/AIDS risky behaviors such as injection drug use and greater use of substances (Angelino 2002; National Institute of Drug Abuse, 2006). Many studies also noted that that psychosocial factors are prevalent in PLWHA and these factors influence HIV/AIDS risky behaviors that may contribute to the high probability of transmission and spread of HIV within high-risk populations (Schiltz and Sandfort, 2000; van der Straten et al., 2000; Wilson and Minkoff, 2001; Ostrow et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2002; Kalichman et al., 2002; Paterson et al., 2000; Semple et al., 2003).

The most plausible explanation for this finding is that psychosocial problems, such as depression, impair both physical and cognitive functioning and can interfere with the decision to practice safe sexual behaviors. Moreover, depression is a barrier to behavior change, which is currently the most successful strategy to effectively reduce the risk of acquiring and spreading HIV/AIDS (Paterson et al., 2000). Reasons underlying the correlation between alcohol use and high-risk sexual behaviors among PLWHA have been described and include decreased inhibitions and risk perception, belief that alcohol enhances sexual arousal, deliberate use of alcohol as an excuse of high-risk behavior (Galvan et al., 2002) and the indirect association that bars are common places to meet potential sexual partners (Amin et al., 1998). The most possible explanation for the significant difference observed between genders with respect to drinking alcohol is that women may be more protected against drinking alcohol than are men because of social factors associated with the female gender’s role and particular personality characteristics.

The findings of gender differences in alcohol use before sex, strongly suggest that biological and psychosocial factors that may play a role in the gender differences in alcohol use are yet to be explored. In the long run, identifying and understanding such differences could improve our understanding of the nature and cause of alcohol use before sex. This could have implications for tailoring HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment intervention strategies to maximize positive outcomes for both males and females.

The finding of this study clearly demonstrates that specific psychosocial problems and HIV/AIDS related risky behaviors are more likely to occur simultaneously in this study population. Thus, when looking at different aspects of HIV/AIDS risky behaviors, it is imperative to realize the impact of psychosocial factors on decision-making. Since any one behavior is part of an interwoven and connected pattern of complex behaviors performed by the individual, future studies are needed to better understand how the multiple measures of psychosocial factors relate to HIV/AIDS risk-taking behaviors. It would also be relevant to examine the role of immunological status (CD4 cell counts) and personality as moderating variables. As stated above, substance use especially alcohol use before sex, is linked to the tendency to have multiple partners and sexual intercourse without condoms. Since alcohol affects judgment and lowers inhibitions, people sometimes do things that they would not normally have done when they use drugs and drink alcohol. These can include having multiple sexual partners, sex with prostitutes and injecting drug use when they would not normally practice these risky behaviors. Further research is also needed to gain a clear understanding of how psychosocial problems are likely to influence substance use behavior and other high HIV/AIDS risky behaviors among PLWHA.

Conclusion

In spite of the vast knowledge about how HIV/AIDS is transmitted, many PLWHA still continue to engage in HIV/AIDS risky behaviors that place others at risk of infection and further place themselves at risk of contracting secondary infections (e.g., syphilis and gonorrhea) that may hasten HIV/AIDS progression. Recognizing that the impact of HIV/AIDS is not only biological but psychosocial in nature, intervention programs, including education and counseling, must be designed holistically to address the complex challenges faced by PLWHA. This sub population should be offered or provided a comprehensive set of psychosocial interventions at all levels of the health system. In particular, depression-related issues of PLWHA should be addressed. Specific psychosocial and psychotherapeutic interventions should be provided to more effectively address associated alcohol and other substance abuse problems. Cross-disciplinary researches that include basic and advanced knowledge of psychosocial problems and HIV/AIDS risky behaviors and the manners in which they interact is needed. Such knowledge is critical for developing interventions to reduce the prevalence of psychosocial problems and as well as other already existing co-occurring HIV/AIDS risky behaviors in PLWHA.

LIMITATIONS

Limitations include the use of a clinic-based convenience sample study of 326 PLWHA in Alabama, USA, which means that the findings presented here may not be generalizable to the broader population of PLWHA. Secondly, the study relied on self-report measures of sensitive issues like number of sexual partners and drug use before sex. Thus, it is likely that high-risky behaviors leading to HIV infection are underreported in the data we used.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by NCMHD SC21MD000102 and NCIR RCMI 5 G12RR03059, National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Abbreviations

- LIAL

Limited interest in aspects of life that used to be important before infected with HIV

- IDU

injecting drug use

- Needleshare

needle sharing

- Nsexpart1year

number of sexual partners in one year

- Nsexpart1month

number of sexual partners in one month

- Nsexpart1week

number of sexual partners in one week

- Sexwithpros

sex with prostitutes

- SexwIDU

sex with injecting drug users

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Coping with AIDS and HIV. 2008. Dec 17th, [Google Scholar]

- Amin G, Shah S, Vankar GK. The prevalence and recognition of depression in primary care. Indian J Psychiatry. 1998;40:364–369. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angelino AF. Depression and adjustment disorder in patients with HIV disease. Top HIV Med. 2002;10(5):31–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arbuckle JL, Werner W. AMOS user’s guide. Chicago, IL: Smallwaters Corporation; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Asch M, Kilbourne M, Gifford L. Under diagnosis of depression in HIV: who are we missing? J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:450–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20938.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bing G, Burnam A, Longshore D. Psychiatric disorders and drug use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected adults in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:721–8. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.8.721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boarts M, Sledjeski M, Bogart L, Delahanty D. The differential impact of PTSD and depression on HIV disease markers and adherence to HAART among people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2006;10:253–261. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen M, Hoffman RG, Cromwell C, Schmeidler JF, Ebrahim G, Carrera, Endorf F. The prevalence of distress in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(1):10–15. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.43.1.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook A, Grey D, Burke J. Depressive symptoms and AIDS-related among a multisite cohort of HIV-positive women. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:133–1140. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.7.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desquilbet L, Deveau C, Goujard C, Hubert JB, Derouineau J, Meyer L. Increase in at-risk sexual behaviour among HIV-1- infected patients followed in the French PRIMO cohort. AIDS. 2002;16(17):2329–2333. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200211220-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farinpour R, Miller N, Satz P. Psychosocial risk factors of HIV morbidity and mortality: Findings from the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2003;25:654–670. doi: 10.1076/jcen.25.5.654.14577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan F, Bing H, Fleishman G, London A, Caetano S, Burnam R, Longshore A, Morton D, Orlando C, Shapiro M. The prevalence of alcohol consumption and heavy drinking among people with HIV in the United States: Results from the HIV Cost and Services Utilization Study. J Stud Alcohol. 2002;63:179–186. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Weinhardt LS, DiFonzo K, Austin J, Luke W. Sensation seeking and alcohol use as markers of sexual transmission risk behavior in HIV-positive men. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24(3):229–235. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2403_08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman C. HIV transmission risk behaviors of men and women living with HIVAIDS: prevalence, predictors, and emerging clinical interventions. Clinical Psychology: Sci Practice. 2000:32–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC. Psychological and social correlates among men and women living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 1999;11(4):415–428. doi: 10.1080/09540129947794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly JA, St Lawrence JS, Stevenson LY, Hauth AC, Kalichman SC, Diaz YE, Brasfield TL, Koob JJ, Morgan MG. Community AIDS/HIV risk reduction: The effects of endorsements by popular people in three cities. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(11):1483–1489. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.11.1483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Komiti A, Judd F, Grech P. Depression in people living with HIV/AIDS attending primary care and outpatient clinics. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2003;37:70–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2003.01118.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesser J. Role of depression, stress, and trauma in HIV disease progression. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:539–545. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181777a5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luber D. Pharmacotherapy of HIV infection. In: Kodakimble MA, Young LL, Kradjan WA, Guglielmo J, editors. Applied Therapeutics. Vol. 69. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott William & Wilkins; 2002. pp. 1–37. [Google Scholar]

- Moore RM, Gebo KA, Lucas GM, Keruly JC. Rate of Co-morbidities Not Related to HIV infection or AIDS among HIV-Infected Patients, by CD4 Count and HAART Use Status. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(8):1102–1104. doi: 10.1086/592115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller RO. Basic Principles of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Springer Verlag; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute of Drug Abuse. Methamphetamine abuse and addiction. 2006 03.23.11, Available from www.nida.nih.gov/PDF/RRMetham.pdf.

- Ostrow DE, Fox KJ, Chmiel JS, Silvestre A, Visscher BR. Attitudes towards highly active antiretroviral therapy are associated with sexual risk taking among HIV-infected and uninfected homosexual men. AIDS. 2002;16(5):775–780. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200203290-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson L, Swindells S, Mohr J, Brester M, Vergis N, Squier C, Wagener M, Singh N. Adherence to protease inhibitor therapy and outcomes in patients with HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:21–30. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-133-1-200007040-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence BW, Miller WC, Gaynes BN, Eron JJ. Psychiatric illness and virologic response in patients initiatiing high active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquire Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:159–66. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802c2f51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pence BW, Miller W, Whetten K, Eron JJ, Gaynes B. N. Prevalence of DSMIV-defined mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders in an HIV clinic in the Southeastern United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2006;42:298–306. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000219773.82055.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robins AG, Dew MA, Davidson S, Penkower L, Becker JT, Kingsley L. Psychosocial factors associated with risky sexual behavior among HIV-seropositive gay men. AIDS Educ Prev. 1994;6(6):483–492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saylors K, Daliparthy N. Native Women, Violence, Substance Abuse and HIV Risk. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2005;37(3):273–281. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2005.10400520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiltz A, Sandfort M. HIV-positive people, risk and sexual behaviour. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50:1571–1588. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00466-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semple SJ, Patterson TL, Grant I. HIV-positive gay and bisexualmen: predictors of unsafe sex. AIDS Care. 2003;15(1):3–15. doi: 10.1080/713990434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel D, Israelski DM, Power R, Prentiss DE, Balmas G, Muhammad M, Garcia P, Koopman C. Acute stress disorder, PTSD, and depression in a clinicbased sample of patients with HIV/AIDS. J Psychosom Res. 2003;55:128. [Google Scholar]

- Heongjin Rho. The Social-survey Analysis Data (Categorical Data) Analysis and Covariance Structure Analysis. SPSS/AMOS-, Heongseol Press; Seoul: 2005. [Accessed February 27, 2009]. Available at: http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m0OGT/is_2_7/ai. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor L, Burnam A, Sherbourne C. The relationship between type of mental health provider and met and unmet mental health needs in a nationally representative sample of HIV-positive patients. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2004;31:149–163. doi: 10.1007/BF02287378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS . [Access date January 10, 2012];AIDS epidemic update. 2007 Available at http://data.unaids.org/pub/epislides/2007/2007_epiupdate_en.pdf.

- van der Straten A, Gomez CA, Saul J, Quan J, Padian N. Sexual risk behaviors among heterosexual HIV serodiscordant couples in the era of post-exposure prevention and viral suppressive therapy. AIDS. 2000;14:F47–F54. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200003100-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whetten K, Leserman J, Lowe K, Stangl D, Thielman N, Swartz M, Hanisch L, Van Scoyoc L. Prevalence of childhood sexual abuse and physical trauma in a southern HIV positive sample from the Deep South. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:970–973. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.063263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TE, Minkoff H. Condom use consistency associated with beliefs regarding HIV disease transmission among women receiving HIV antiretroviral therapy. J Acquire Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;27(3):289–291. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200107010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt E, Myers F, Williams K, Kitchen R, Loeb T, Carmona J, Wyatt E, Chin D, Presley N. Does a history of trauma contribute to HIV risk for women of color? Implications for prevention and policy. Am J Public Health. 2002;92:660–665. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]