Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this review is to describe the empirical literature on the health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in Latina breast cancer survivors by exploring the social determinants of health. In framing the key domains of survivors’ quality of life within a ecological-contextual model that evaluates individual and societal contributions to health outcomes, we provide a comprehensive landscape of the diverse factors constituting Latina survivors’ lived experiences and their resultant quality of life outcomes.

Methods

We retrieved 244 studies via search engines and reference lists, of which 37 studies met the inclusion criteria.

Results

Findings document the importance of the social determinants of HRQOL, with studies documenting ecological and contextual factors accounting for significant variance in HRQOL outcomes. Our review identifies a dearth of research examining community-, institutional-, and policy-level factors, such as health care access, legal and immigration factors, physical and built environments, and health care affordability and policies affecting Latina breast cancer survivors’ HRQOL.

Conclusions

Overall research on Latina breast cancer survivorship is sparse, with even greater underrepresentation within longitudinal and intervention studies. Results highlight a need for clear documentation of the comprehensive care needs of underserved cancer survivors and interventions considering integrated systems of care to address the medical and ecological factors known to impact the HRQOL of breast cancer survivors.

Keywords: Quality of life, Latinas, Contextual-ecological perspective, Breast cancer survivors

Introduction

Breast cancer accounts for 28% of all cancer diagnoses and is the leading cause of cancer-related death among Latinas in the United States [1]. Breast cancer demands significant mental and physical adjustment, consequently affecting health related quality of life (HRQOL). HRQOL is defined as one’s subjective sense of well-being in response to a major illness [2,3]. HRQOL is a multifarious construct encompassing spiritual, functional, cognitive, emotional/psychological, physical, and social well-being [2,4], and provides significant prognostic data for cancer-related outcomes [5].

Although early research on quality of life in breast cancer survivors primarily focused on predominantly Caucasian non-Hispanic survivors [6], Latinos constitute the largest and the fastest-growing ethnic minority group [7], so understanding cancer outcomes among the increasing number of Latino cancer survivors is important. Given the diversity of the Latino population in terms of country of origin and acculturation status [8], Latinos face unique challenges when entering a new society based not only on language, but also on other contextual factors, including loss of social capital, economic difficulties or living in ethnic enclaves with inadequate resources [8]. Therefore, a multi-level model that considers contextual factors can more fully explain health outcomes. To more comprehensively evaluate HRQOL in Latina-American Breast Cancer Survivors (LABCS), an approach incorporating individual patient domains to larger social contexts is required [9].

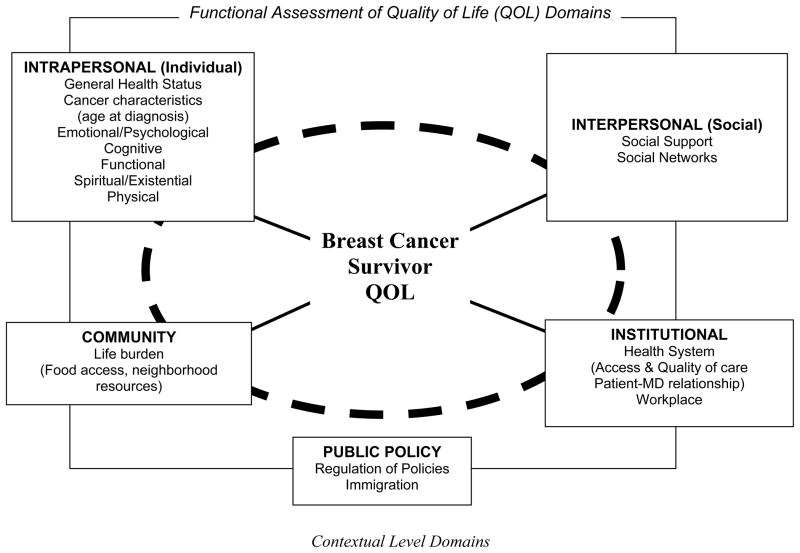

Ecological approaches investigate individuals, their environments, and the interactions between them. The Contextual Model of HRQOL includes multiple dimensions: socio-ecological, cultural, demographic, health-care system, cancer-related medical factors, general health and co-morbidity, health care practices, and psychological [9]. While Ashing-Giwa’s Contextual Model incorporates both individual (micro) and systemic (macro) levels [9,10], McLeroy et al.’s (1988) Ecological Model enhances specificity by delineating levels of influences (e.g., community, institutional). The Ecological Model [11] is an approach that outlines how multiple levels of influence interact to determine health [12]. The multiple levels include intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, community, and policy [11]. The policy level is of critical importance, dictating the status of women and other disenfranchised groups. Therefore, we expanded the Contextual Model with the Ecological Model to better understand specific gaps in the existing research and identify key intervention targets for LABCS.

The Contextual Model and the Ecological Model share commonalities, such as categorizing the primary domains of HRQOL (physical, functional, emotional, spiritual, and social well-being), within the intrapersonal level domain. While both models offer contextual-based dimensions, a synthesized model provides a roadmap for informing intervention planning at different levels of influence [11], and considers context-specific cancer domains for assessing survivors’ at risk for poor HRQOL and relevant HRQOL disparities [10]. Therefore, we used this enhanced Contextual-Ecological Model to examine the HRQOL literature on LABCS (Figure 1). We folded the demographic, worldview and spirituality components of the Contextual Model into the intrapersonal level of our new synthesized model to provide a better assessment of individual characteristics.

Figure 1.

Contextual and Ecological HRQOL Model

The purpose of this article is to review the literature on LABCS, exploring all levels of the Contextual and Ecological HRQOL Model from the intrapersonal to public policy level. We used our synthesized model to explore key HRQOL domains (Figure 1) within the research conducted to date and to identify knowledge gaps regarding multilevel influences on Latina-Americans.

Methods

Study Selection and Review Criteria

For this review we selected four search engines, which based on past research were expected to provide the most comprehensive list of results. We used Pubmed, Google Scholar, PsychInfo, and Web of Science and review of citation lists to identify literature published between January 2000 and March 2010. We searched on the terms quality of life, QOL, breast cancer, Latina or Hispanic, and cancer survivor as single-word items and in combination. We selected broad keywords such as quality of life, rather than specific domains (e.g., psychological) because we were interested in finding how broader cancer survivorship factors fit into the new contextual-ecological model. The most widely accepted definition of cancer survivorship marks the onset at the day of diagnosis [13,14] with long-term survivorship defined as 5+ years post diagnosis [15].

Articles included in this review met the following inclusion criteria: (1) qualitative or quantitative research study that addressed either single or multiple HRQOL-related factors; (2) focused on Latina/Hispanic BCS or provide Latina-Hispanic-specific results; (3) published in a peer-reviewed journal between January 2000–March 2010; and (4) research conducted in the United States. The initial search identified 244 studies, of which 26 met the inclusion criteria. We then reviewed the reference lists from these articles for additional publications, obtaining an additional 11 studies. The final sample included 37 studies.

Analysis and Interpretation

A trained research assistant (JGD) and the first author (MCL) evaluated each article to assess: (1) study purpose, (2) research design, (3) measure of HRQOL, (4) participant demographics, and (5) results. Because HRQOL is multifaceted and includes domains related to psychological/emotional, cognitive, functional, spirituality, and physical functioning [4,16], we chose these domains as the starting point of our analysis. Review of the articles led to identification of additional HRQOL domains, including health system factors and the workplace; these domains were then placed within the levels of the Contextual and Ecological Model: intrapersonal, interpersonal, institutional, community, and public policy influences. This classification system allowed us to identify conceptual gaps in the breast cancer survivorship research literature for Latinas (see Table).

Table 1.

A Review of Studies on Latina Breast Cancer Survivors

| INTRAPERSONAL FACTORS | INTERPERSONAL FACTOR | COMMUNITY FACTORS | INSTITUTIONAL FACTORS | PUBLIC POLICY | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUTHOR | Emo./Psych. | Cog. | Fx | Sp./Ex. | Phys. | Soc. Supp. | Sex./Mar. Issues | Healthcare Sys. | Workplace | ||

| Alferi et al. (2001)[17] Longitudinal Latinas (n= 51) |

✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Ashing-Giwa et al. (2006)[18] Qualitative Latinas (n=26) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Ashing-Giwa et al. (2007)[33] Cross-Sectional Multi-Ethnic Sample (Latinas n=183) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Ashing-Giwa & Lim(2009)[42] Cross-Sectional Multi-Ethnic Sample (Latinas n=183) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Ashing-Giwa, Lim, Gonzalez (2010)[44] Cross-Sectional Multi-Ethnic Sample (Latinas n=183) |

✓ | ||||||||||

| Ashing-Giwa & Lim (2010a)[16] Cross-Sectional Multi-Ethnic Sample (Latinas n=166) |

✓ | ||||||||||

| Ashing-Giwa & Lim (2010b)[43] Cross-Sectional Multi-Ethnic Sample (Latinas n=183) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Bowen et al. (2007)[13] Longitudinal Multi-Ethnic Sample (Latinas n=143) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Buki et al. (2008)[14] Qualitative Latinas (n=18) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Campesino et al. (2009)[19] Qualitative Latinas (n=10) |

✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Carver et al. (2006)[34] Longitudinal Multi-Ethnic Sample Latinas (n=32) |

✓ | ||||||||||

| Culver et al. (2002)[35] Longitudinal Multi-Ethnic Sample (Latinas n=53) |

✓ | ||||||||||

| Culver et al. (2004)[40] Cross-Sectional Multi-Ethnic Sample (Latinas n=59) |

✓ | ||||||||||

| Dirksen & Erickson (2002)[29] Cross-Sectional Multi-Ethnic Sample (Latinas n=50) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Dwight-Johnson et al. (2005)[20] Intervention Latinas (n=55) |

✓ | ||||||||||

| Ell, Xie, et al. (2008)[76] Mixed Methods Multi-Ethnic Sample (Latinas n=370) |

✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Eversley et al. (2005)[36] Cross-Sectional Multi-Ethnic Sample (Latinas n=29) |

✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Fatone et al. (2007)[30] Qualitative Multi-Ethnic Sample (Latinas n=12) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||

| Galvan et al. (2009)[21] Qualitative Latinas (n=22) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Giedzinska et al. (2004)[37] Cross-Sectional Multi-Ethnic Sample (Latinas n=78) |

✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Hawley et al. (2008)[45]Cross-Sectional Multi-Ethnic Sample (Latinas n=196) |

✓ | ||||||||||

| Hughes et al. (2008)[22]Intervention Latinas (n=25) |

✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Janz et al. (2008)[46] Cross-Sectional Multi-Ethnic Sample (Latinas n =484) |

✓ | ||||||||||

| Janz et al. (2009)[38] Cross-Sectional Multi-Ethnic Sample (Latinas n=484) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Kreling et al. (2006)[60] Qualitative Multi-Ethnic Sample (Latinas n=6) |

✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Lim et al. (2009)[31] Cross-Sectional Multi-Ethnic Sample (Latinas n=183) |

✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Maly et al. (2006)[47] Cross-Sectional Multi-Ethnic Sample (n=99) |

✓ | ||||||||||

| Moadel, Morgan & Dutcher, (2007)[49] Cross-Sectional Multi-Ethnic Sample (Latinas n=48) |

✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Napoles-Springer, Livaudais, et al. (2007)[24] Cross-sectional Latinas (n=117) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Napoles-Springer, Ortiz, et al. (2007)[23] Cross-Sectional Latinas (n=330) |

✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Napoles-Springer et al. (2009)[25] Mixed Methods Spanish-speaking Latinos (n=89), Latina breast cancer survivors (n=29) and community advocates (n=17) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Sammarco & Konecny (2008)[26] Cross-Sectional Latinas (n=89) |

✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Sammarco & Konecny (2010)[56] Cross-Sectional Multi-Ethnic Sample (Latinas n=98) |

✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Smith et al. (2009)[56] Longitudinal Latinas (n= 51) |

✓ | ||||||||||

| Stephens et al. (2010)[27]Cross-Sectional Latinas (n= 259) |

✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Wildes et al. (2009)[28] Cross-Sectional Latinas(n=117) |

✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Yoo et al. (2009)[32] Qualitative Multi-Ethnic Sample (Latinas n=7) |

✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

Multi-ethnic sample includes research with Latina, White, Asians and/or Blacks.

Results

The 37 identified studies included research that used a variety of research designs (cross-sectional, longitudinal, and qualitative) and target populations (multiethnic samples vs. Latinas, only). Twenty-five studies included multiethnic samples that explored differences among Latina, White, Black, and Asian survivors; however, only Latina-specific results are discussed in this study, with 12 studies focused exclusively on Latinas [14,17–28]. Within the Latina-specific studies (n=12), nine provided regional or national origin/descent of the participants. Three studies had all-immigrant samples and one study identified the percentage of foreign-born participants. In some studies, the terms “origin” or “Puerto-Rican ethnicity” failed to identify whether participants were born abroad or second or third generation US Latinas.

A number of studies described emotional/physiological well-being among Latinas (n=25), social support or marital issues (n=19), physical domains (n=14), functional (n=9), and spirituality (n=10; see Table). Only two studies discussed cognitive well-being among Latinas [29,30]. While most studies were conducted in California (n=17), some were conducted in the Northeast (4), Southeast (3), Southwest (6) and in multiple states across the US (4). One study did not provide geographic information.

Intrapersonal Factors

Intrapersonal factors included health status (e.g., co-morbidities), age at diagnosis, psychological/emotional well-being, cognitive well-being, functional well-being, spirituality, and physical functioning. Most research within the intrapersonal category were quantitative (n=29). Regarding health status, only one study assessed co-morbidities wherein Latinas reported a greater number of co-morbidities (i.e., high blood pressure, diabetes) compared to Asians [31]. Age at diagnosis was an influential factor for women’s well-being in one study [32] with women 70 and older reporting that cancer was just one added health condition to manage [32]. Older women (> 70 years) particularly struggle to maintain an appearance of self-sufficiency, afraid to be dependent or cause worry in their children [32].

In multiethnic samples, Latinas reported poorer psychological and emotional well-being than other ethnic groups [13,23,24,33–38] with all but two studies controlling for stage of disease. In one study with a multiethnic sample that measured cognitive well-being, 75% of all participants, including Latinas, noted forgetfulness as a side effect of treatment [30]. Researchers largely assessed functional well-being among Latinas in terms of work capability; with several studies citing financial distress for survivors who had to maintain employment due to cancer or its treatment [16,18,21,30,39]. In studies exploring the association of religiosity/spirituality on HRQOL among LABCS, high levels of religiosity/spirituality corresponded to higher levels of functional well-being [28], coping [18,28,30,40], and feeling closer to God [13,14]. While fatalistic views have been linked to religiosity (i.e., seeing cancer as God’s decision) [25], prior research into interventions to reduce cancer fatalism appears promising [41] since survivors appeared to be less fatalistic over [14,31], and may be useful to help newly diagnosed Latina women cope with anxiety about their illness.

In the physical domain, Latinos reported arm and breast pain, fatigue, hair loss, nausea [30], weight gain from treatment [33], and postoperative pain [14] with poorer physical functioning reported more among low-acculturated Latinos [31,38] than other groups [31,33,36]. Higher income was related to better physical HRQOL [42] and being diagnosed at an earlier stage [43]. Although some studies included younger samples of (mean age ≤ 49 years), no key findings emerged related to age and physical functioning [19,20,36,44].

Although acculturation spans across all levels (intrapersonal, interpersonal), given the potential influence of acculturation on physical and emotional health, this concept is well positioned under the intrapersonal level. Six studies considered acculturation variables, focusing on various HRQOL domains including intrapersonal (e.g., emotional well-being) and interpersonal factors (e.g., the role of family in decision-making process) [27,38,45–47]. Acculturation, including English language proficiency, may serve as a proxy for recency of immigration, lower educational attainment and job status; these are shown to be correlates of poorer health outcomes.

Interpersonal Factors

Social networks and social support were important interpersonal level influences among Latinas. Across both quantitative and qualitative studies involving social support, researchers addressed certain sources (family, friends) and types of support (informational, instrumental). The quantitative literature focused more on evaluation of degree of social support rather than social networks per se [14,17,21,25–27,29,32,46,48–50]. One study noted how social influences went beyond supportive roles, 49% of the less acculturated older Latinas and 18% of the more acculturated older Latinas indicated that their families determined their final treatment decision [47]. The central role of family for survivors can provide a sense of support but also added concerns for women who do not want to cause any hardships on their families [25]. Although studies point to the importance of social support and social networks in Latinas’ breast cancer experience, Latina immigrant breast cancer survivors have reported a significant lack of social support [26,33,50].

Community, Institutional, and Public Policy Factors

Two formative studies mentioned the importance of community-level influences for improved survivorship care [21,25]. Community-level factors, such as supermarket location and availability of healthy foods, are associated with general dietary patterns and an overall healthy diet [51,52]. Communities characterized by social deprivation and unemployment have reduced access to major supermarkets [53], exercise facilities or sidewalks [54], thus hindering the ability of individuals in these communities to effectively adhere to physical activity regimens. Increased physical activity among non-LABCS may be associated with improved daily functioning and overall HRQOL [55–57]. Furthermore, communities with no easy access to clinics that provide consultation on healthy lifestyle practices face both institutional and community-level barriers. Lack of access to preventive care is more common among impoverished communities [58] and may potentially hinder proper survivorship care.

The reports describing community-level factors on LABCS’s HQOL discussed how knowledge of and access to community resources (such as financial assistance, housing, mental health services, meals, transportation, child care, and community-based organizations) are valuable community-level variables influencing the cancer experience [21,25]. Future empirical work is needed to explore community-level factors and their associations with increased levels of physical activity and HRQOL in Latinas with breast cancer.

At the institutional level, continuity of care improves patient outcomes, especially among those with chronic conditions [59]. About one-third of studies with LABCS addressed institutional factors, including insurance costs, language barriers, and legal status or workplace support, impact of receiving proper care, or and access/adherence to health services [14,18,19,21,23,24,28,29,31,38,44,60]. For instance, lack of continuity of care, especially among those who are treated by several different doctors at the same facility, renders patients unable to create relationships conducive to successful cancer management [18]. Although no systematic research has yet to be conducted related to the impact of institutional factors on LABCS’s HQOL, a plausible hypothesis for the poor health outcomes evident among LABCS [44] (e.g., low levels of overall physical energy and well-being and greater reported pain) could be related to institutional factors such as the inability to access quality health care or challenges in communication with doctors regarding their health care needs [18]. Furthermore, minority patients reported greater difficulty getting appointments and longer wait times compared to non-minority patients, even when they had insurance [61]. Other institutional factors, such as proximity of the hospital in relation to a breast cancer survivors’ residence, may possibly influence delays in treatment [44], and hinder optimal survivorship care. These types of institutional-level barriers highlight the need for socio-cultural and patient-centered services in a medical setting to improve survivorship care among Latinas. We identified an institutional level intervention targeting LABCS which evaluated the effects of a collaborative care program on HRQOL. While this intervention highlighted institutional factors (clinical case-management, timely patient and provider reminders), community (neighborhood cancer resources) intrapersonal factors (health literacy) were also considered and in concert were found to improve emotional well-being among low-income Latinas [20].

Public Policy Level Factors

Public policy within health care involves the regulation of funding from the local to the national level [11]. Two qualitative studies focused on immigration policy, discussing the effects of unauthorized legal status on HRQOL [18,19] and others have stressed the importance of policies that target screening, education, and treatment to prevent cancer disparities in breast cancer mortality [62]. Because health care services are purchased by a combination of government and private insurers, many, especially immigrant survivors, who have limited English language skills or are unfamiliar with the health care polices will experience difficulty navigating the health care system [63]. For all cancer survivors, follow-up care is often fragmented with no single physician serving as the coordinator of care following the completion of treatment [64]. For LABCS who exhibited poor English fluency effective communication with the doctor is compromised [14,31,36]. Future work should further explore health care decision-making in the context of immigration and policy and across all economic strata for LABCS.

Individual and Contextual-Level Correlates of HRQOL Outcomes

As presented in this review, individual-level variables such as time since diagnosis or psychological well-being may contribute to HRQOL outcomes; however, within underserved survivor groups such as Latinas, consideration of systematic contextual level characteristics at the community, institutional and/or policy may further explain HRQOL. Several barriers exist for LABCS that are not evident for white, high-income groups or non-immigrant groups, including lack of transportation, financial and insurance barriers, lack of childcare or language translation, low health literacy, or low literacy, lack of psychosocial or emotional support, and social isolation. Hence, research on contextual level factors will also bridge a gap in the current cancer survivorship literature.

Attention to underlying fundamental characteristics (social status, race, segregation) which often is associated with the availability of community and institution-based resources [65] need to be considered to reduce the disparities that exist among Latina cancer survivors. Similarly, interventions aimed at influencing macro-level variables may depend on large-scale system changes (e.g., establishing more community services accessible to Latina survivors or providing interpreter services to bridge language barriers in clinics). The single intervention study we identified that addresses micro and macro levels of influence demonstrates positive changes in HRQOL life for breast cancer survivors [20]. Research addressing multiple influences on health outcomes is possible and future work should consider inclusion of domains beyond the emotional and physical to target other contextual-level (access to health care resources) variables impacting health.

Discussion and Conclusions

The present review is among the first to summarize the literature on Latina breast cancer survivors’ HRQOL survivorship applying a contextually based social-ecological model (Table) across multiple levels (e.g., intrapersonal, community, institutional). We noted significant gaps in existing work: (1) the small number of studies that included adequate Latina samples, (2) lack of prospective studies, (3) dearth of interventional research, (4) few studies considering community-level factors and (5) inadequate focus on institutional level influences on cancer survivorship and quality of life.

Our results, together with previous findings, suggest a potential compounding effect of systemic contexts on critical HRQOL outcomes. For example, outside of the cancer literature, research demonstrates self-management practices (e.g., testing glucose levels in people with diabetes) are significantly hindered if patients reside in low-resourced neighborhoods or have inadequate health care plans [66,67]. Many LABCS live in neighborhoods with limited resources; our findings suggest self care practices may be compromised in these environments, exacerbating existing disparities in a population already challenged by poorer HRQOL outcomes.

Of the numerous studies that investigated one or more HRQOL domains, the majority had multi-ethnic samples. Fewer studies focused exclusively on LABCS and were mostly conducted in California. The diversity and the 46.7 million Latinos in the US [68] underscores the importance of addressing the lack of research that investigates HRQOL and cancer survivorship studies across regions of the US beyond California.

Our review suggests evidence from cross-sectional studies focused on specific domains of the HRQOL model and provides a strong foundation to begin translating existing data into intervention development and testing. Importantly, future interventions focused on improving cancer survivorship outcomes must tackle community-level and institutional influences on HRQOL. These investigations can benefit from the substantial body of work conducted in nonclinical and community settings with Latinos and other racial and ethnic minorities who have chronic health conditions[69–71]. For example, community-based studies implementing physical activity interventions demonstrate improved physical fitness [72]. As many survivors report weight gain after diagnosis [73], efforts are needed to improve community resources (food products, access to exercise facilities) so HRQOL is not compromised. Furthermore, among Latinas, we do not yet have enough information of how dietary change (e.g., increased intake of fruit and vegetables) or increased level of physical fitness impact survivorship experiences or the care these survivors receive following the completion of adjuvant therapy. Although we have a growing body of literature on nutrition and exercise with primarily European American survivor populations [74,75], studies are needed to address this paucity of nutrition and exercise intervention research with Latina survivors.

Studies discussing institutional influences addressed the importance of having a positive doctor–patient relationship for improved HRQOL outcomes [31,48]. Although the factors we identified as fitting into the community level of influence overlap with the social support domain -- touching on issues of informational (information on treatment options) and instrumental support (e.g., transportation services, child care) [21,25] --there was a noticeable gap in addressing community-level factors beyond social support networks (e.g., church group and families), such as neighborhood characteristics and available organizations(e.g., psychosocial services in clinic or hospital-based settings). Our findings should be interpreted in the context of the limitations of this review. First, although we searched for studies related to Latina breast cancer survivors’ HRQOL in four major databases, it is possible we missed some studies. An additional limitation was the heterogeneity of the populations included in the reviewed work. Given the often small number of Latinas in research conducted with multiethnic samples, isolation of results specific to Latinos was a challenge. Finally, given the dearth of HRQOL studies focus on community-level influences, we were limited by studies that consider this domain within other levels of influence (i.e., interpersonal level influences). The institutional and community levels of our Contextual and Ecological HRQOL Model are key aspects that need to be considered in survivorship research and interventions promoting survivorship care among Latinas. Although promising work is beginning to emerge, the current paucity of literature investigating institutional and community influences on HRQOL, as well as the lack of intervention research with Latina survivors, suggests research efforts in these areas deserve increased attention. We urge researchers to build on the existing literature to develop and evaluate interventions using multi-level systematic approaches to improve health outcomes and shrink disparities in Latina survivors’ HRQOL.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by NCI Grant # 5U01CA114593-03 (the Latin American Cancer Coalition) and Susan G. Komen for the Cure Grant# POP0601292 and The Department of Defense Award # W81XWH-04-1-0548. We would like to thank Ms. Susan Marx and Yasmin Salehizadeh for their assistance with manuscript preparation.

References

- 1.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for Hispanics/Latinos 2009–2011. American Cancer Society; Atlanta, GA: 2009. (Available from http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@nho/documents/document/ffhispanicslatinos20092011.pdf, retrieved August 2, 2010) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donovan K, Sanson-Fisher RW, Redman S. Measuring quality of life in cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:959–968. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.7.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Campbell A, Converse PE, Rodgers WL. The Quality of American Life: Perceptions, Evaluations, and Satisfactions. Russell Sage Foundation; New York: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brady MJ, Cella DF, Mo F, et al. Reliability and validity of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast quality-of-life instrument. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:974–986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gotay CC, Kawamoto CT, Bottomley A, Efficace F. The prognostic significance of patient-reported outcomes in cancer clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:1355–1363. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.3439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paskett ED, Alfano CM, Davidson MA, et al. Breast cancer survivors’ health-related quality of life: racial differences and comparisons with noncancer controls. Cancer. 2008;113:3222–3230. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pew Hispanic Center. Statistical Portrait of Hispanics in the United States. 2008 [factsheet]. (Available from http://pewhispanic.org/factsheets/factsheet.php?FactsheetID=58, retrieved August 2, 2010)

- 8.Dubowitz T, Bates LM, Acevedo-Garcia D. The Latino health paradox: looking at the intersection of sociology and health. In: Bird CE, Conrad P, Fremont AM, Timmermans S, editors. Handbook of Medical Sociology. Vanderbilt University Press; Nashville, TN: 2010. pp. 106–123. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashing-Giwa KT. The contextual model of HRQoL: a paradigm for expanding the HRQoL framework. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:297–307. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-0729-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pedro LW. Theory derivation: adaptation of a contextual model of health related quality of life for rural cancer survivors. Online J Rural Nurs Health Care. 2010;10:80–95. [Google Scholar]

- 11.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, Glanz K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q. 1988;15:351–377. doi: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stokols D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. Am J Health Promot. 1996;10:282–298. doi: 10.4278/0890-1171-10.4.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bowen DJ, Alfano CM, McGregor BA, et al. Possible socioeconomic and ethnic disparities in quality of life in a cohort of breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;106:85–95. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9479-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Buki LP, Garces DM, Hinestrosa MC, Kogan L, Carrillo IY, French B. Latina breast cancer survivors’ lived experiences: diagnosis, treatment, and beyond. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2008;14:163–167. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bloom JR, Stewart SL, D’Onofrio CN, Luce J, Banks PJ. Addressing the needs of young breast cancer survivors at the 5 year milestone: can a short-term, low intensity intervention produce change? J Cancer Surviv. 2008;2:190–204. doi: 10.1007/s11764-008-0058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ashing-Giwa KT, Lim JW. Exploring the association between functional strain and emotional well-being among a population-based sample of breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2010;19:150–159. doi: 10.1002/pon.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alferi SM, Carver CS, Antoni MH, Weiss S, Duran RE. An exploratory study of social support, distress, and life disruption among low-income Hispanic women under treatment for early stage breast cancer. Health Psychol. 2001;20:41–46. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.20.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ashing-Giwa KT, Padilla GV, Bohorquez DE, Tejero JS, Garcia M. Understanding the breast cancer experience of Latina women. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2006;24:19–52. doi: 10.1300/J077v24n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Campesino M, Ruiz E, Glover JU, Koithan M. Counternarratives of Mexican-origin women with breast cancer. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2009;32:E57–E67. doi: 10.1097/ANS.0b013e3181a3b47c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dwight-Johnson M, Ell K, Lee PJ. Can collaborative care address the needs of low-income Latinas with comorbid depression and cancer? Results from a randomized pilot study. Psychosomatics. 2005;46:224–232. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.46.3.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galvan N, Buki LP, Garces DM. Suddenly, a carriage appears: social support needs of Latina breast cancer survivors. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2009;27:361–382. doi: 10.1080/07347330902979283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hughes DC, Leung P, Naus MJ. Using single-system analyses to assess the effectiveness of an exercise intervention on quality of life for Hispanic breast cancer survivors: a pilot study. Soc Work Health Care. 2008;47:73–91. doi: 10.1080/00981380801970871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Napoles-Springer AM, Ortiz C, O’Brien H, Diaz-Mendez M, Perez-Stable EJ. Use of cancer support groups among Latina breast cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2007;1:193–204. doi: 10.1007/s11764-007-0029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Napoles-Springer AM, Livaudais JC, Bloom J, Hwang S, Kaplan CP. Information exchange and decision making in the treatment of Latina and white women with ductal carcinoma in situ. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2007;25:19–36. doi: 10.1300/J077v25n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Napoles-Springer AM, Ortiz C, O’Brien H, Diaz-Mendez M. Developing a culturally competent peer support intervention for Spanish-speaking Latinas with breast cancer. J Immigr Minor Health. 2009;11:268–280. doi: 10.1007/s10903-008-9128-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sammarco A, Konecny LM. Quality of life, social support, and uncertainty among Latina breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2008;35:844–849. doi: 10.1188/08.ONF.844-849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stephens C, Stein K, Landrine H. The role of acculturation in life satisfaction among Hispanic cancer survivors: results of the American Cancer Society’s study of cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2010;19:376–383. doi: 10.1002/pon.1566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wildes KA, Miller AR, de Majors SS, Ramirez AG. The religiosity/spirituality of Latina breast cancer survivors and influence on health-related quality of life. Psychooncology. 2009;18:831–840. doi: 10.1002/pon.1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dirksen SR, Erickson JR. Well-being in Hispanic and non-Hispanic white survivors of breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29:820–826. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.820-826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fatone AM, Moadel AB, Foley FW, Fleming M, Jandorf L. Urban voices: the quality-of-life experience among women of color with breast cancer. Palliat Support Care. 2007;5:115–125. doi: 10.1017/s1478951507070186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim JW, Gonzalez P, Wang-Letzkus MF, Ashing-Giwa KT. Understanding the cultural health belief model influencing health behaviors and health-related quality of life between Latina and Asian-American breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer. 2009;17:1137–1147. doi: 10.1007/s00520-008-0547-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoo GJ, Levine EG, Aviv C, Ewing C, Au A. Older women, breast cancer, and social support. Support Care Cancer. 2010;18:1521–1530. doi: 10.1007/s00520-009-0774-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ashing-Giwa KT, Tejero JS, Kim J, Padilla GV, Hellemann G. Examining predictive models of HRQOL in a population-based, multiethnic sample of women with breast carcinoma. Qual Life Res. 2007;16:413–428. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-9138-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carver CS, Smith RG, Petronis VM, Antoni MH. Quality of life among long-term survivors of breast cancer: Different types of antecedents predict different classes of outcomes. Psychooncology. 2006;15:749–758. doi: 10.1002/pon.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Culver JL, Arena PL, Antoni MH, Carver CS. Coping and distress among women under treatment for early stage breast cancer: comparing African Americans, Hispanics and non-Hispanic Whites. Psychooncology. 2002;11:495–504. doi: 10.1002/pon.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eversley R, Estrin D, Dibble S, Wardlaw L, Pedrosa M, Favila-Penney W. Post-treatment symptoms among ethnic minority breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2005;32:250–256. doi: 10.1188/05.ONF.250-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Giedzinska AS, Meyerowitz BE, Ganz PA, Rowland JH. Health-related quality of life in a multiethnic sample of breast cancer survivors. Ann Behav Med. 2004;28:39–51. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2801_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Janz NK, Mujahid MS, Hawley ST, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in quality of life after diagnosis of breast cancer. J Cancer Surviv. 2009;3:212–222. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0097-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ell K, Vourlekis B, Lee PJ, Xie B. Patient navigation and case management following an abnormal mammogram: a randomized clinical trial. Prev Med. 2007;44:26–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Culver JL, Arena PL, Wimberly SR, Antoni MH, Carver CS. Coping among African-American, Hispanic, and non-Hispanic white women recently treated for early stage breast cancer. Psychol Health. 2004;19:157–166. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Powe BD, Weinrich S. An intervention to decrease cancer fatalism among rural elders. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1999;26:583–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ashing-Giwa KT, Lim JW. Examining the impact of socioeconomic status and socioecologic stress on physical and mental health quality of life among breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2009;36:79–88. doi: 10.1188/09.ONF.79-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ashing-Giwa KT, Lim JW. Predicting physical quality of life among a multiethnic sample of breast cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:789–802. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9642-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ashing-Giwa KT, Lim JW, Gonzalez P. Exploring the relationship between physical well-being and healthy lifestyle changes among European- and Latina-American breast and cervical cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2010;19:1161–1170. doi: 10.1002/pon.1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hawley ST, Janz NK, Hamilton A, et al. Latina patient perspectives about informed treatment decision making for breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:363–370. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Janz NK, Mujahid MS, Hawley ST, Griggs JJ, Hamilton AS, Katz SJ. Racial/ethnic differences in adequacy of information and support for women with breast cancer. Cancer. 2008;113:1058–1067. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maly RC, Umezawa Y, Ratliff CT, Leake B. Racial/ethnic group differences in treatment decision-making and treatment received among older breast carcinoma patients. Cancer. 2006;106:957–965. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ashing-Giwa K, Kagawa-Singer M. Infusing culture into oncology research on quality of life. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2006;33:31–36. doi: 10.1188/06.ONF.S1.31-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Moadel AB, Morgan C, Dutcher J. Psychosocial needs assessment among an underserved, ethnically diverse cancer patient population. Cancer. 2007;109:446–454. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sammarco A, Konecny LM. Quality of life, social support, and uncertainty among Latina and Caucasian breast cancer survivors: a comparative study. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2010;37:93–99. doi: 10.1188/10.ONF.93-99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Diez-Roux AV, Nieto FJ, Caulfield L, Tyroler HA, Watson RL, Szklo M. Neighbourhood differences in diet: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:55–63. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.1.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moore LV, Diez Roux AV, Nettleton JA, Jacobs DR., Jr Associations of the local food environment with diet quality--a comparison of assessments based on surveys and geographic information systems: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:917–924. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fellowes M. From Poverty, Opportunity: Putting the Market to Work for Lower Income Families. Brookings Institution; Washington, DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Deshpande AD, Baker EA, Lovegreen SL, Brownson RC. Environmental correlates of physical activity among individuals with diabetes in the rural midwest. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:1012–1018. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.5.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pinto BM, Maruyama NC. Exercise in the rehabilitation of breast cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 1999;8:191–206. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1611(199905/06)8:3<191::AID-PON355>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Smith AW, Alfano CM, Reeve BB, et al. Race/ethnicity, physical activity, and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:656–663. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Turner J, Hayes S, Reul-Hirche H. Improving the physical status and quality of life of women treated for breast cancer: a pilot study of a structured exercise intervention. J Surg Oncol. 2004;86:141–146. doi: 10.1002/jso.20065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Vachon GC, Ezike N, Brown-Walker M, Chhay V, Pikelny I, Pendergraft TB. Improving access to diabetes care in an inner-city, community-based outpatient health center with a monthly open-access, multistation group visit program. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:1327–1336. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cabana MD, Jee SH. Does continuity of care improve patient outcomes? J Fam Pract. 2004;53:974–980. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kreling B, Figueiredo MI, Sheppard VL, Mandelblatt JS. A qualitative study of factors affecting chemotherapy use in older women with breast cancer: barriers, promoters, and implications for intervention. Psychooncology. 2006;15:1065–1076. doi: 10.1002/pon.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shi L. Experience of primary care by racial and ethnic groups in the United States. Med Care. 1999;37:1068–1077. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199910000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miranda PY, Wilkinson AV, Etzel CJ, et al. Policy implications of early onset breast cancer among Mexican-origin women. Cancer. 2011;117:390–397. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schyve PM. Language differences as a barrier to quality and safety in health care: the Joint Commission perspective. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22 (Suppl 2):360–361. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0365-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Institute of Medicine, National Research Council of The National Academies. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lopez-Class M, Jurkowski J. The limits of self-management: community and health care system barriers among Latinos with diabetes. J Hum Behav Soc Environ. 2010;20:808–826. doi: 10.1080/10911351003765967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Horowitz CR, Colson KA, Hebert PL, Lancaster K. Barriers to buying healthy foods for people with diabetes: evidence of environmental disparities. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1549–1554. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.9.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Piette JD, Wagner TH, Potter MB, Schillinger D. Health insurance status, cost-related medication underuse, and outcomes among diabetes patients in three systems of care. Med Care. 2004;42:102–109. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000108742.26446.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Borrell LN. Racial identity among Hispanics: implications for health and well-being. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:379–381. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.058172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lorig KR, Ritter PL, Gonzalez VM. Hispanic chronic disease self-management: a randomized community-based outcome trial. Nurs Res. 2003;52:361–369. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200311000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Two Feathers J, Kieffer EC, Palmisano G, et al. Racial and Ethnic Approaches to Community Health (REACH) Detroit partnership: improving diabetes-related outcomes among African American and Latino adults. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1552–1560. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yancey AK, Kumanyika SK, Ponce NA, et al. Population-based interventions engaging communities of color in healthy eating and active living: a review. Prev Chronic Dis. 2004;1:A09. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wilcox S, Dowda M, Griffin SF, et al. Results of the first year of active for life: translation of 2 evidence-based physical activity programs for older adults into community settings. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:1201–1209. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.074690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Demark-Wahnefried W, Peterson BL, Winer EP, et al. Changes in weight, body composition, and factors influencing energy balance among premenopausal breast cancer patients receiving adjuvant chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19:2381–2389. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.9.2381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bernstein A, Nelson ME, Tucker KL, et al. A home-based nutrition intervention to increase consumption of fruits, vegetables, and calcium-rich foods in community dwelling elders. J Am Diet Assoc. 2002;102:1421–1427. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8223(02)90315-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nelson ME, Layne JE, Bernstein MJ, et al. The effects of multidimensional home-based exercise on functional performance in elderly people. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2004;59:154–160. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.2.m154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ell K, Xie B, Wells A, Nedjat-Haiem F, Lee PJ, Vourlekis B. Economic stress among low-income women with cancer: effects on quality of life. Cancer. 2008;112:616–625. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]