Abstract

The development of gadolinium chelators that can be easily and readily linked to various substrates is of primary importance for the development high relaxation efficiency and/or targeted magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents. Over the last 25 years a large number of bifunctional chelators have been prepared. For the most part, these compounds are based on ligands that are already used in clinically approved contrast agents. More recently, new bifunctional chelators have been reported based on complexes that show a more potent relaxation effect, faster complexation kinetics and in some cases simpler synthetic procedures. This review provides an overview of the synthetic strategies used for the preparation of bifunctional chelators for MRI applications.

Keywords: Bifunctional chelator, Gadolinium, Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Lanthanide, Bioconjugate, Molecular Imaging, DOTA, DTPA

Introduction

Magnetic resonance imaging is a powerful tool in diagnostic medicine and in preclinical research. The strengths of MRI are high spatial (<0.1 mm) and temporal resolution, 3-dimensional anatomical images, lack of ionizing radiation, deep tissue penetration, soft tissue contrast, and multiple contrast mechanisms. MRI is not a very sensitive technique and typically the signal of water protons is detected. Differences in tissue water content, water relaxation times, flow, or diffusion can all be used to generate image contrast. Image contrast can also be achieved by the addition of a paramagnetic compound termed a “contrast agent” or “imaging probe”. These molecules act as catalysts to shorten the relaxation times of the water molecules that they encounter resulting in changes in MR signal. Unlike in nuclear imaging where the probe is directly detected, in MRI the probe is seen indirectly via its effect on water protons. The use of contrast agents has grown considerably over the years in both the clinical and research setting. MR contrast agents have been extensively applied in the clinic for the detection of brain tumors, arterial blockages and aneurysms, and organ perfusion to name a few applications.

MR probes are categorized as T1 or T2 agents. All probes shorten both T1 and T2, but T1 agents alter tissue T1 more than T2 on a percentage basis, while T2 agents have a bigger percent effect on T2. Practically, the presence of a T1 agent results in increased MR signal and positive image contrast. T2 agents destroy signal and result in negative image contrast. We will focus our attention on T1 probes. The vast majority of this class of agents are based on Gd(III) complexes, however other paramagnetic ions like Mn(II) and Fe(III) have also been used [1–5].

A local fluctuating magnetic field is required to induce relaxation of water protons. The Gd(III) ion has 7 unpaired electrons and generates a large local field as it tumbles in solution. However the Gd(III) aqua ion itself cannot be used because it forms insoluble phosphate, carbonate, and/or hydroxide complexes in blood at pH 7.4. Moreover it has been shown that Gd(III) is toxic to human cells in vitro [6–8] and to rats [9] in vivo likely due to the inhibition of transmembrane currents through Ca(II) channels [10–11] or by forming inorganic insoluble salt aggregates with anions such phosphates [12–13].

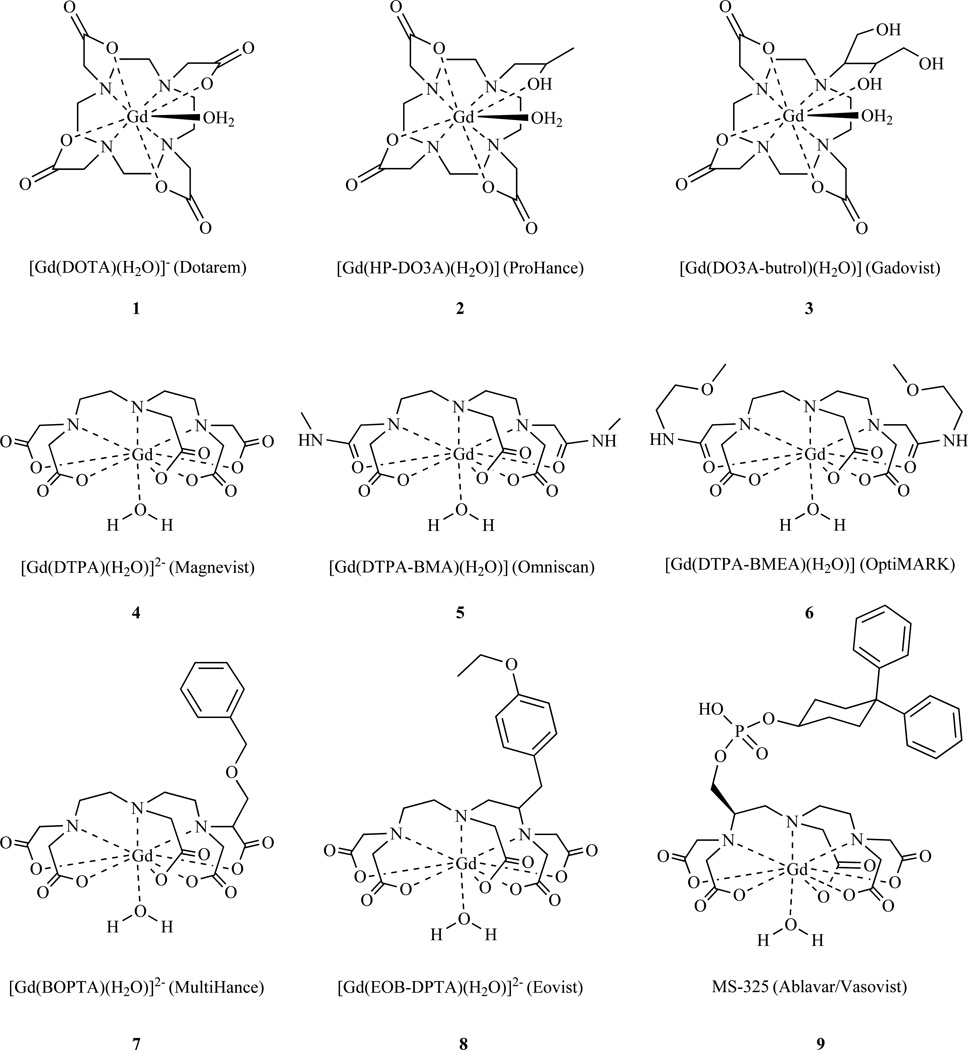

An obvious way to reduce the toxicity of the Gd(III) ion is to administer it in the form of a stable complex by using a multidentate ligand to chelate the Gd(III) ion. The need for high stability is emphasized by the association of some gadolinium based contrast agents with nephrogenic systemic fibrosis (NSF), a very rare but devastating disease found in patients with compromised renal function [14–18]. A vast body of literature exists describing ligands for Gd(III), and the majority are polyamino-polycarboxylate ligands [19–26]. Chart 1 shows the structures of MR contrast agents that are approved for human use in various countries.

Chart 1.

Gadolinium-based contrast agents approved for human use in USA and/or Europe. Note all comprise an octadentate co-ligand and a single coordinated water ligand (q=1)

The design of contrast agents for MRI must balance the need for a high thermodynamic stability and kinetic inertness with respect to Gd(III) release (safety of the agent) with an intense relaxation effect on water protons (efficacy of the agent). Inspection of Chart 1 shows that approved contrast agents all contain an octadentate ligand for safety and a site for water coordination. The coordinated water ligand is relaxed by the Gd(III) and undergoes rapid (>106 s−1) exchange with solvent water. This rapid water exchange results in an overall decrease in the relaxation time of solvent water, and hence signal change in MRI.

The increase in water proton relaxation rate (R1 = 1/T1) is linearly proportional to the concentration of Gd(III), with a proportionality constant termed relaxivity, r1. This is given by equation 1 where R10 is the relaxation rate of the solvent in absence of Gd(III). A larger relaxivity indicates a more potent relaxation agent.

| Equation 1 |

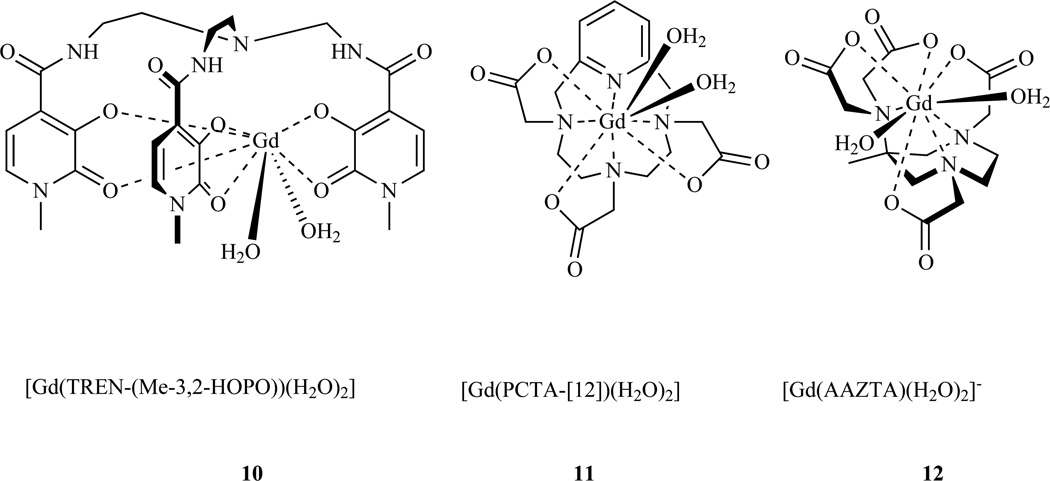

The Gd(III) ion shortens the longitudinal relaxation time of water protons via a dipolar relaxation mechanism that is well described in a number of excellent reviews [25, 27–30]. In short, the fluctuating magnetic field generated by the seven unpaired f-electrons of the Gd(III) ion catalyzes the nuclear relaxation of the water proton. At most common imaging field strengths, the fluctuating magnetic field arises from the tumbling of the Gd(III) complex in solution. The time constant for this fluctuation is termed the rotational correlation time, τR; relaxation will be optimal when this fluctuation matches the nuclear Larmor frequency. In order to transmit the relaxation to bulk solvent, the coordinated water molecule must be in fast exchange with bulk water. The water exchange rate (kex) or its inverse, the water residency time (τm) are used to describe this property. Relaxivity can be increased by increasing the number of water molecules (q) coordinated to the Gd(III) ion. However increasing q tends to reduce the overall stability of the complex and may also result in having the water ligands displaced by coordination of endogenous anions[31]. Optimal relaxivities can be obtained by fine tuning all of these parameters. In designing MR probes one has to reconcile the opposing needs for high thermodynamic stability and water access to the metal ion. The ligands used for probes currently administered in clinical practice are octadentate (Chart 1) leaving one open position for water coordination. There are also examples of heptadentate and hexadentate ligands that generate complexes with two [32–39] or three [40] coordinated water molecules and that retain acceptable stability (Chart 2).

Chart 2.

Stable gadolinium complexes with two inner-sphere water ligands (q=2).

Commercial MR contrast agents are usually administered at doses of about 0.1 mmol/kg and must therefore be highly soluble. All the approved agents are either neutral or negatively charged as positively charged complexes tend to show a higher toxicity. These agents distribute in the vascular and extravascular extracellular space and are not metabolized. The majority of commercial agents are excreted via the kidneys, although Eovist is about 50% cleared via the hepato-biliary route, and as a result is used for liver imaging. All of these agents are usually cleared from the body within hours.

For the most part, clinical contrast agents are not specifically targeted to a protein or receptor (exceptions noted below). Bifunctional chelators (BFC) are required to create either targeted probes and/or multimeric probes. Targeting is done to convey molecular specificity. For MR contrast agents, the detection limit for a single Gd(III) complex is in the low micromolar range [41], and it is often necessary to incorporate multiple complexes to enhance molecular relaxivity. Both non-covalent protein binding and oligomerization often result in increased relaxivity per Gd ion. This is because the larger molecule tumbles at a slower rate that more closely matches the Larmor frequency [42]. Over the last 25 years numerous examples of protein targeted (albumin [43–59], fibrin [60–68], collagen [69–70], carbonic anhydrase [71], folate receptor [72–76]) and multimeric (dendrimer [39, 74, 77–104], polymer [105–117], oligo or polypeptide [118–126], polysaccharide [127–143]) contrast agents have been described. Increasingly, targeted nanoparticles are described where an assembly of Gd(III) complexes (for high sensitivity) is conjugated with one or more targeting vectors (antibody, peptide, etc) [60, 144–166] for specificity. All of these approaches rely on bifunctional gadolinium chelates.

With this review we provide an overview of the most common approaches that have been presented in the scientific literature dealing with the preparation of bifunctional chelators for Gd(III) ions. We restricted our interest to ligands that present a functional group that can be readily conjugated to a targeting moiety or a macromolecular support.

The chemistry involved in the preparation of such ligands largely overlaps with the chemistry involved in the preparation of BFC for radionuclides used in radiopharmaceticals for diagnostic imaging or radiotherapy. There are two main differences in the design requirements for metal containing radiopharmaceuticals with respect to MR agents. First, no water access to the metal center is necessary for radiopharmaceuticals, but a high thermodynamic stability and kinetic inertness remains mandatory. Second, it is important to have fast complexation kinetics due to the short half-life of the radionuclides used for these applications. Perhaps not surprisingly, most BFC are based on the ligand cores shown in Chart 1. The popularity of these reagents means that some are now commercially available.

DTPA derivatives

The first MR agent to be approved for use in clinical diagnosis was the dimeglumine salt of [Gd(DTPA)(H2O)]2− (DTPA = diethylenetriaminepentaacetato) which was marketed as Magnevist in 1988. Currently, [Gd(DTPA)(H2O)]2− remains the most widely used MR probe (note, we will use a shorthand of GdL, where L = ligand, to refer to the metal complexes, i.e. GdDTPA). The octadentate ligand DTPA forms very stable complexes with Gd3+ (equilibrium constant for metal complex formation, Kf = 1022.46 [167]) where the metal ion is coordinated by five carboxylato oxygen atoms and three amino nitrogen atoms. Note from Chart 1 that when DTPA binds Gd(III) it results in the formation of seven 5-membered chelate rings. Gd(III) generally prefers 5-membered chelate rings with oxygen and nitrogen donor atoms. The complexation kinetics are relatively fast compared to macrocyclic ligands and complexation typically occurs within a few minutes [168]. On the other hand, the rate of decomplexation or transmetallation is faster for DTPA derivatives than Gd(III) complexes of DOTA derivatives [169–171]. A comprehensive review of the chemistry involved in the preparation of acyclic ligands for lanthanide ions, including DTPA derivatives, was prepared by Anelli et al. [172].

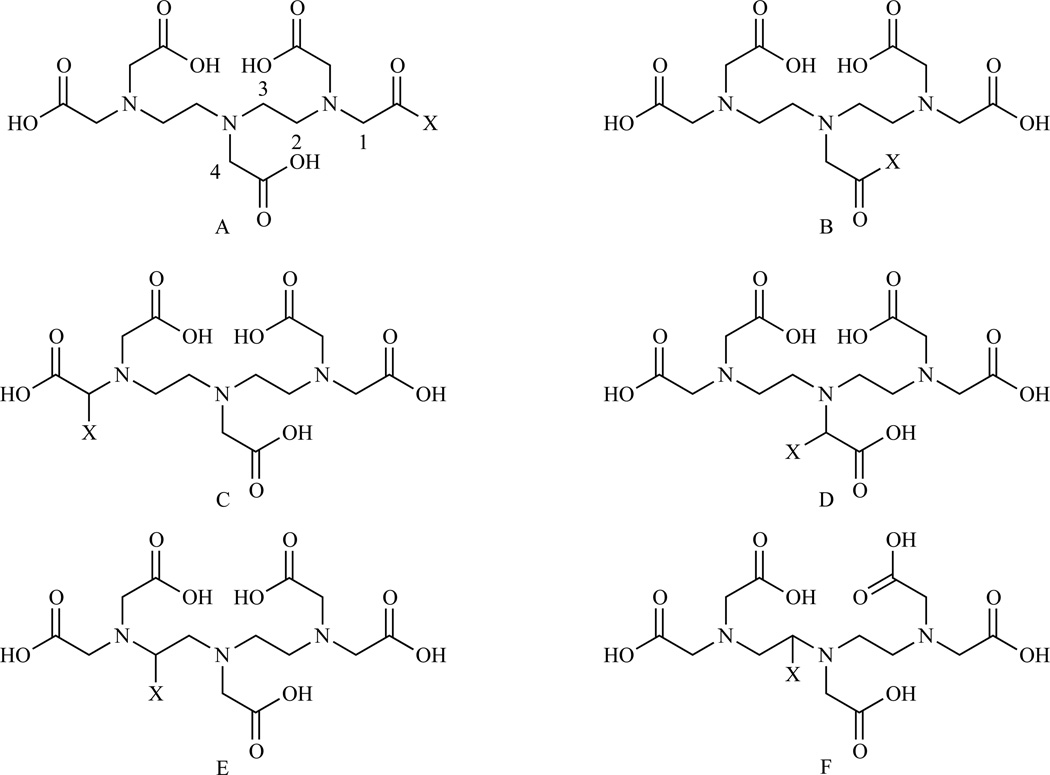

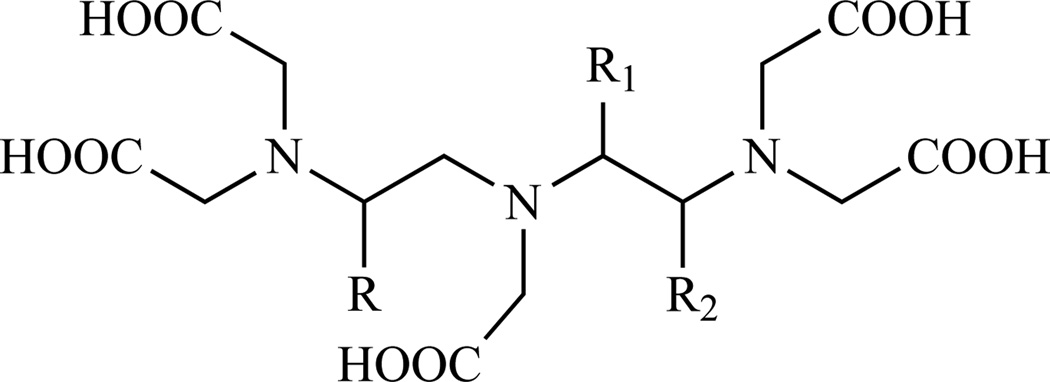

Due to the established safety record of GdDTPA, efforts have been made to prepare bifunctional DTPA for easy derivatization. The different modes in which DTPA can be mono-functionalized are sketched in Chart 3.

Chart 3.

General structures of mono-functionalized DTPAs

DTPA monoamides

Terminal carboxyamido derivatization

Functionalization of one of the carboxylic groups (Chart 3, A and B) is usually accomplished by conversion into amide derivatives. However, replacement of one carboxylate with one carboxyamido group is accompanied by a decrease of the thermodynamic formation constant by about three orders of magnitude [173]. The use of DTPA monoamides is thus not recommended, but nonetheless they are still commonly used due to their fast complexation kinetics and ease of synthesis.

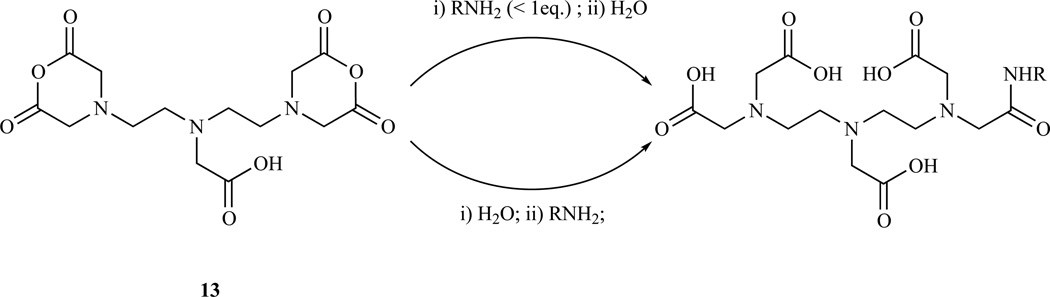

The simplest method to form terminal DTPA mono-amides (Chart 3, A) involves the reaction of an amine with commercially available DTPA bisanhydride either in equimolar ratio or with an excess of anhydride followed by hydrolysis. This strategy leads inevitably to the formation of mixtures containing various amounts of DTPA and DTPA bisamides. Depending on the particular amine used, the separation of these reaction byproducts can turn out to be difficult and time consuming. To reduce the amount of bisamide byproduct, the bisanhydride can be partially hydrolysed before the addition of the amine (Scheme 1) [174]. This approach was used to prepare a variety of MR probes including agents that are responsive to myeloperoxidase [175] or to β-galactosidase [176], an antisense-type agent targeted to a model macromolecular receptor [177], and a probe conjugated with the dye Evans Blue designed to detect endothelial lesions [178].

Scheme 1.

Formation of DTPA monoamides from DTPA dianhydride.

A different approach to the preparation of terminally functionalized DTPA involves the synthesis of intermediates with one orthogonally protected carboxylate, which can be selectively deprotected and coupled to amines. In the following section, a number of strategies used for the preparation of DTPA tetraesters with a free carboxyl group available for conjugation will be described.

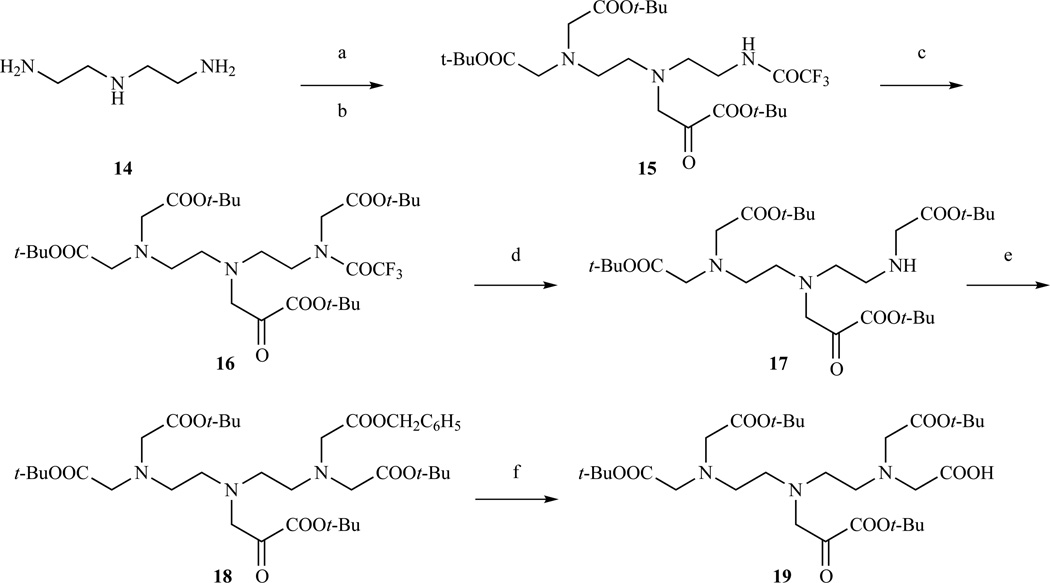

Arano et al. (Scheme 2) prepared a tetra-t-Bu ester of DTPA with one benzyl protected carboxylate [179]. Monoprotection of diethylenetriamine with ethyl trifluoroacetate followed by a two step exhaustive carboxymethylation with t-Bu bromoacetate led to intermediate 16. Hydrazinolysis of the trifluoroacetyl group and carboxymethylation with benzyl bromoacetate led to the orthogonally protected compound 18. Catalytic hydrogenation with Pd/C afforded compound 19 with a carboxylic group available for functionalization.

Scheme 2.

Formation of DTPA tetra-t-Bu ester from orthogonally protected precursor [179]. (a) CF3COOC2H5; (b) BrCH2COOt-Bu, DIPEA, 66% yield over two steps; (c) BrCH2COOt-Bu, NaH, 91% yield; (d) NH2NH2, t-BuOH; (e) BrCH2COOBz, DIPEA, 52% yield over two steps; (f) Pd/C, H2, 98% yield.

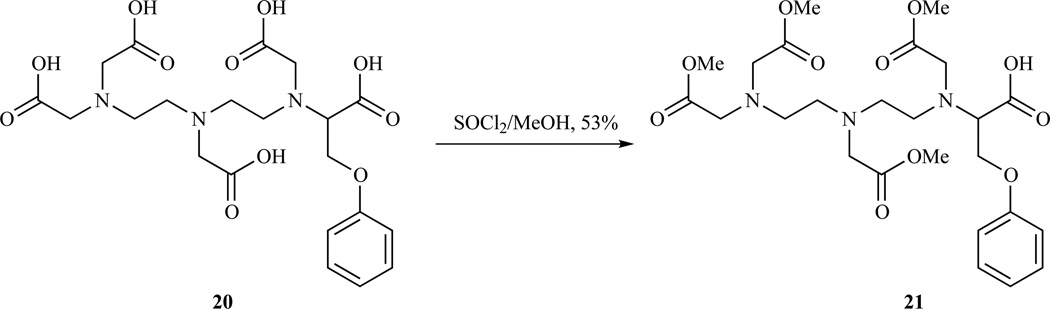

The different esterification rates of acetic and propanoic acids were exploited by Felder et al. to prepare tetramethyl esters of a DTPA analogue (Scheme 3). Reaction of compound 20 with thionyl chloride in methanol gave the tetraester monoacid 21 in 50–60 % yields [180].

Scheme 3.

Formation of a tetramethyl ester DTPA analogue by selective esterification [180].

Attempts to obtain a selective enzymatic [181] or basic mono-hydrolysis in presence of CuCl2 or NiCl2 [182–183] of penta ethyl or t-Bu DTPA esters have yielded only a mixture of terminal and centrally hydrolyzed DTPA which can be difficult to separate.

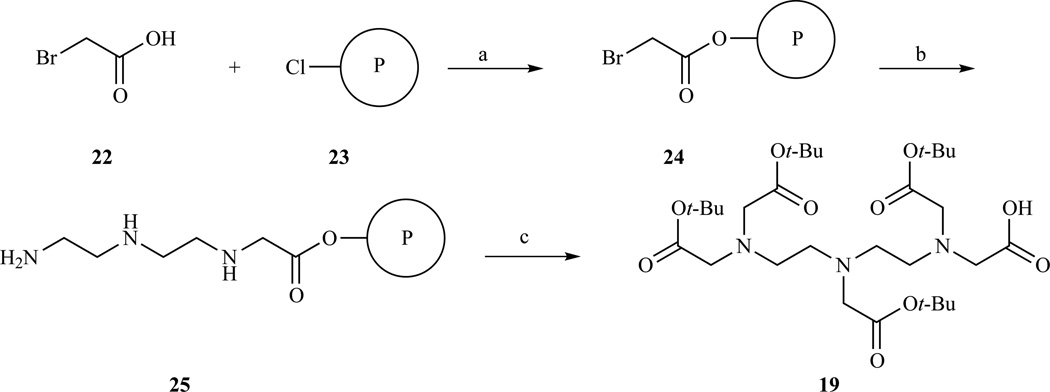

Leclercq et al.[184] used solid phase synthesis (SPS) to prepare the tetra t-Bu ester DTPA monoacid (Scheme 4). Chlorotrityl chloride resin was functionalized with bromoacetic acid and then the solid supported bromide was reacted with excess diethylenetriamine. Alkylation with excess t-Bu bromoacetate was followed by cleavage in mildly acidic conditions with trifluoroethanol to prevent hydrolysis of the t-Bu esters. The cleaved product was obtained in high yield (89%) without the need for a purification step. No evidence of the symmetric DTPA derivative with a free central carboxymethylene was observed. The principal advantage of using SPS lies in the ease of purification while the principal disadvantage is the need to use a large amount of reagents which often do not get recycled. The DTPA monoacid was conjugated with a cationic lipid and used to form lipoplexes with plasmid DNA. The distribution of these lipoplexes, formulated as micelles or liposomes, could be monitored using MRI in vivo in mice up to ten days [184].

Scheme 4.

Solid phase synthesis of DTPA tetra-t-Bu ester. (a) DIPEA, (b) diethylenetriamine, (c) i. BrCH2COOt-Bu, TEA; ii. CF3CH2OH/CH2Cl2, 89% yield over three steps. Ref. [184]

Central carboxyamido derivatization

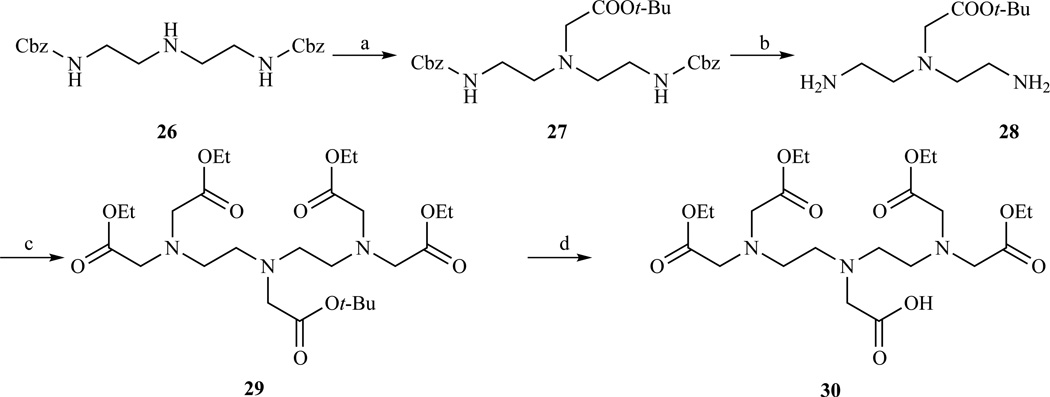

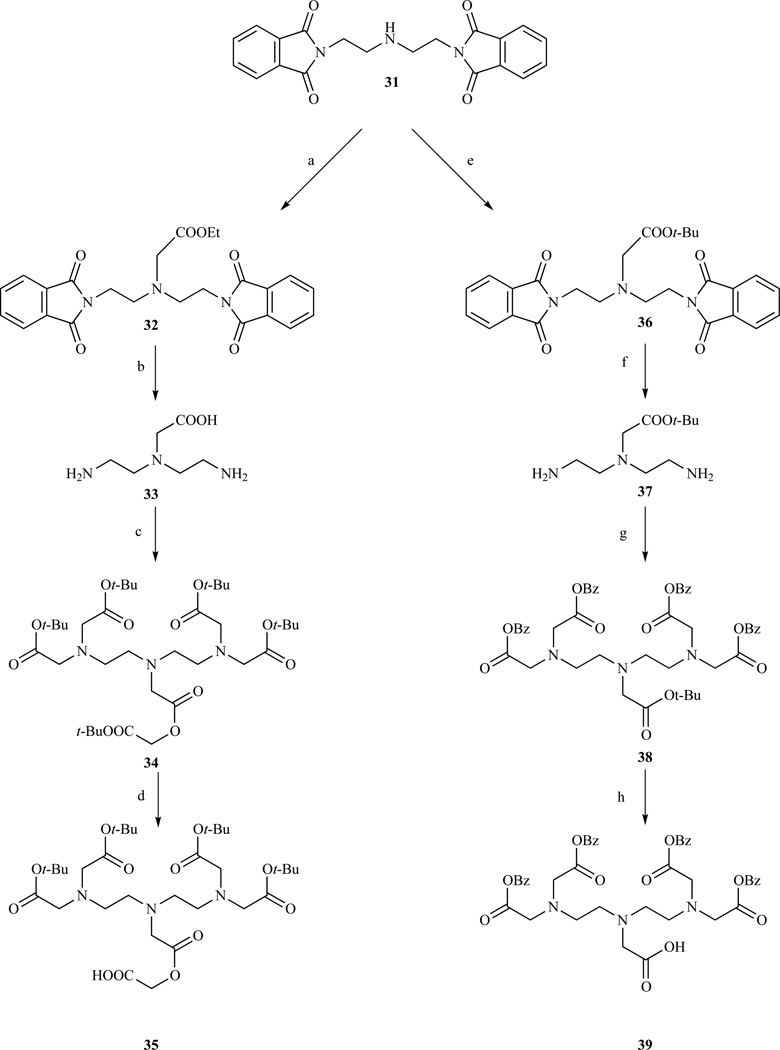

Access to DTPA derivatives functionalized on the central carboxylate (Chart 3, B) has been obtained in a variety of ways. A synthesis starting from diethylenetriamine and involving a series of protection and de-protection steps was used to produce a terminally protected diethylenetriamine with a free secondary amine which can be reacted with a suitable orthogonally protected α-haloacetate ester [185]. This approach was followed by Giordano et al. to prepare a DTPA tetraethyl ester[186] that was used for conjugation with oligodeoxynucleotides (Scheme 5). A similar strategy was followed by Davies et. al. (Scheme 6) [187] and by Achilefu [188–189], by terminally protecting diethylenetriamine with phthaloyl protecting groups followed by carboxymethylation with ethyl or t-Bu bromoacetate of the central nitrogen. Removal of the phthaloyl groups could be accomplished by hydrazinolysis only for the t-Bu analogue. In presence of other ester protections, e.g. ethyl, benzyl or allyl, this would lead to intramolecular cyclization and the formation of a lactam derivative. To avoid this, acid hydrolysis was used in those cases. Alkylation with t-Bu or benzyl bromoacete followed by selective deprotection of the central carboxyl group gave compounds 35 and 39.

Scheme 5.

Synthesis of DTPA tetraethyl ester with the central carboxylate available for conjugation. a) BrCH2COOt-Bu, DIPEA, 96% yield; b) 10% Pd/C, 4% HCO2H/MeOH; c) BrCH2COOEt, DIPEA, 51% yield over two step; d) TFA, 46% yield. Ref.[186]

Scheme 6.

Synthesis of DTPA tetrabenzyl ester with the central carboxylate available for conjugation and synthesis of DTPA functionalized on the central carboxylate. a) BrCH2COOEt, Na2CO3, EtOH, 78% yield; b) 6M HCl, 98%; c) BrCH2COOt-Bu, DIPEA, 61% yield; d) NaSPh, Et3N, MeCN/DMF, 22% yield; e) BrCH2COOt-Bu, DIPEA, 51% yield; f) N2H4, 87% yield; g) BrCH2COOBz, DIPEA, 59% yield; h) TFA, 78% yield. Ref. [187]

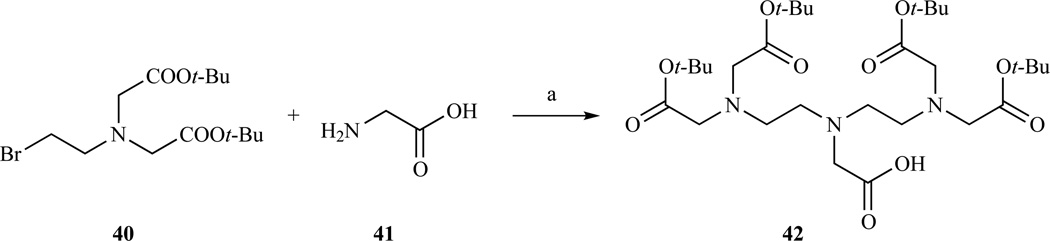

Perhaps the most straightforward method to prepare a DTPA derivative with the central carboxylate available for conjugation was proposed by Anelli et al. [190] who found that dialkylation of glycine benzyl ester, or even simple glycine at pH 10, with compound 40 [191] using a protocol initially proposed by Rapoport, led to the DTPA tetra-t-Bu ester 42 (Scheme 7). In one instance, compound 42 was conjugated to a linear lipophilic amine and evaluated as a probe for magnetic resonance angiography, but showed a rapid blood clearance [192]. Greater compound persistence in the blood stream was observed when derivatives with two liphophilic chains were used.

Scheme 7.

Synthesis of DTPA tetra-t-Bu ester by alkylation of glycine with bromo derivative 40. a) H2O/EtOH, pH=10, 70% yield. Ref. [190]

DTPA with backbone functionalization

Creation of a bifunctional DTPA-based chelator via conversion of one of the acetate groups to a carboxyamide has the drawback of sacrificing an anionic carboxylate donor for a neutral amide oxygen donor resulting in lower stability of the gadolinium complex. Functionalization of the DTPA backbone has the advantage of generating ligands that form complexes with similar or higher thermodynamic stability and that are more kinetically inert than GdDTPA [171, 193]. Compared to the DTPA-monoamides, this results in introduction of a chiral center that may complicate synthesis and characterization. In this review we will specify the stereochemistry if it was defined in the original work. The functionalization can occur on the diethylenetriamine backbone (Chart 3, E–F) or on one acetic arm (Chart 3, C–D).

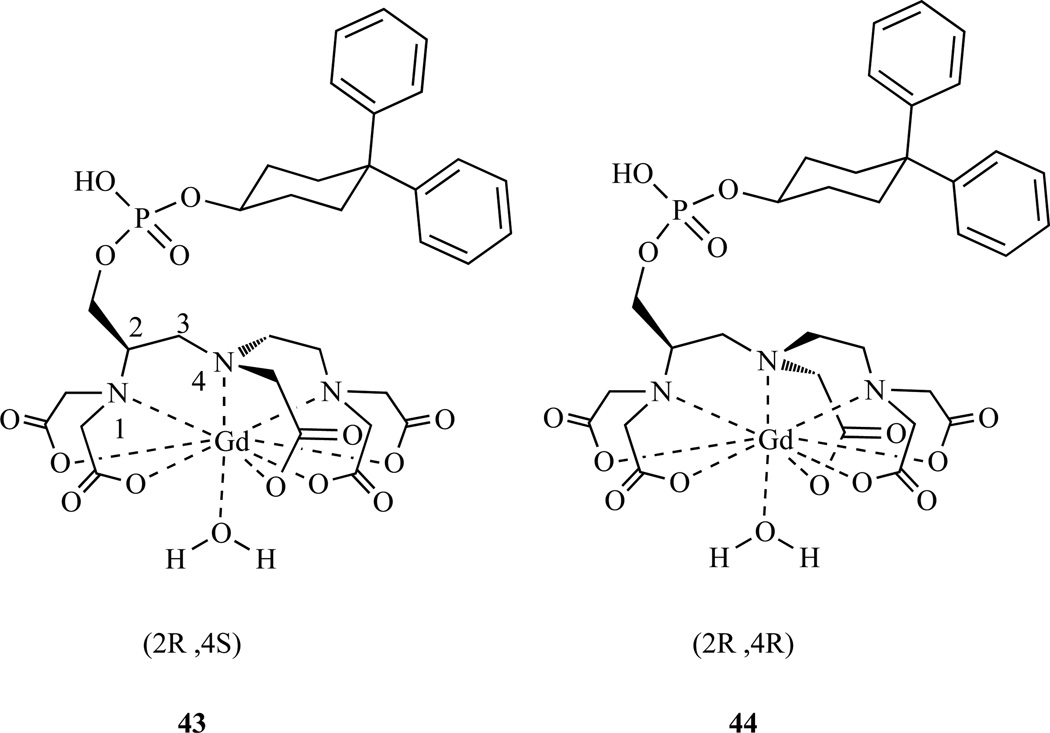

LnDTPA complexes form Δ and Λ wrapping isomers that interconvert in solution. This conformational isomerism was studied for MS-325 (Chart 1), a backbone substituted DTPA as well as for other DTPA derivatives [194–196]. MS-325 is derived from L-serine, resulting in an R configuration at the methine carbon (Chart 4). Complexation makes the central N chiral, and therefore four diastereomers are possible: Δ-R,R, Δ-R,S, Λ-R,R, and Λ-R,S. However only the two Λ diasteromers, Λ-R,R and Λ-R,S, were observed. Both isomers had the same helicity of the wrapping acetate arms, which positions the phosphodiester side chain in a favorable equatorial position; the energetically disfavored wrapping isomers with the phosphodiester group in an axial position were not observed. A 1.8:1 ratio of Λ-R,R/Λ-R,S was observed [197]. The interconversion between these diastereomers is slower than in GdDTPA or in other DTPA derivatives, presumably because of this large substituent. Interconversion is catalyzed by acid, making it possible to isolate pure diastereomers by maintaining pH > 7.

Chart 4.

MS-325 stereoisomers.

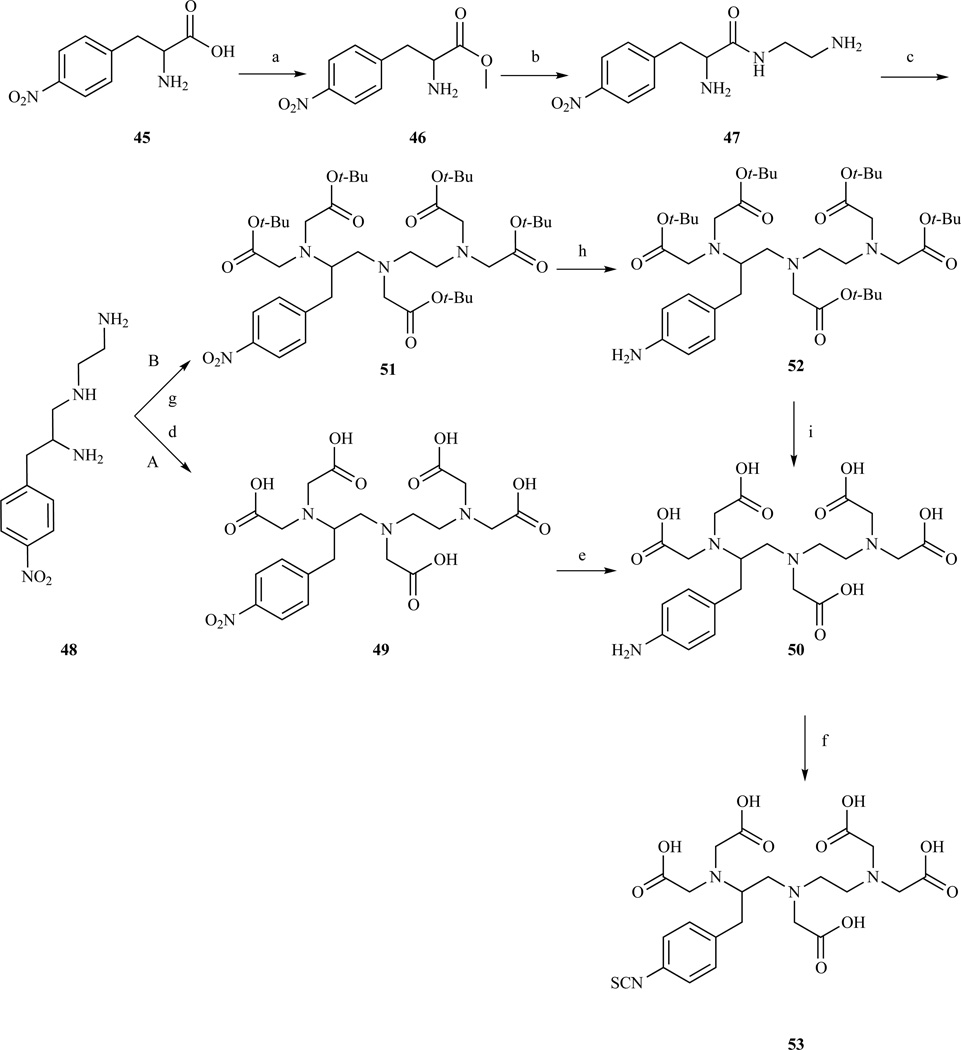

Functionalization at position 2 (Chart 3, E), on the backbone was achieved by Brechbiel et al. who prepared a p-aminobenzyl DTPA derivative in five steps starting from p-nitrophenylalanine (Scheme 8, path A) [198–199]. After methylation, p-nitrophenylalanine is reacted with excess ethylenediamine and then reduced with borane. Alkylation of the amines with excess bromoacetic acid followed by reduction of the nitro group afforded compound 50, which was subsequently converted into the isothiocyanate. The same procedure has been adapted, substituting the appropriate branched 1,2 diamine for ethylenediamine, to produce p-SCN-Bz-DTPA derivatives containing methyl substituents on the backbone in order to investigate more rigid and kinetically inert ligands (Chart 5) [195, 199]. Brechbiel’s procedure was slightly modified by Cummins et al. [195] and later adapted to a multigram scale by Corson and Meares [200] (Scheme 8, path B). The main difference was that the carboxymethylation step was performed with t-Bu bromoacetate to avoid the lengthy purification of the highly polar compound 49.

Scheme 8.

Synthesis of p-SCN-Bz-DTPA. a) HCl, MeOH 88–97% yield; b) ethylenediamine, TEA, 88–95% yield; c) BH3, THF 34–96% yield; d) BrCH2COOH, KOH, 35% yield; e) Pd/C, H2 pH=10, yield not given; f) CSCl2, yield not given; g) BrCH2COOt-Bu, 71–94% yield; h) Pd/C, H2, EtOAc, 90–99% yield, i) HCl(aq) or TFA, 95–100% yield; Refs. [195, 198–200]

Chart 5.

p-SCN-Bz-DTPA derivatives with methyl backbone substituents to improve the stability of the resulting lanthanide complexes. 54 (1B4M-DTPA): R=4-SCN-Bz, R1=H, R2=Me; 55: R=4-SCN-Bz, R1=Me, R2=H; 56: R=Me, R1=4-SCN-Bz, R2=H; 57: R=H, R1=4-SCN-Bz, R2=H; Refs.[195, 199]

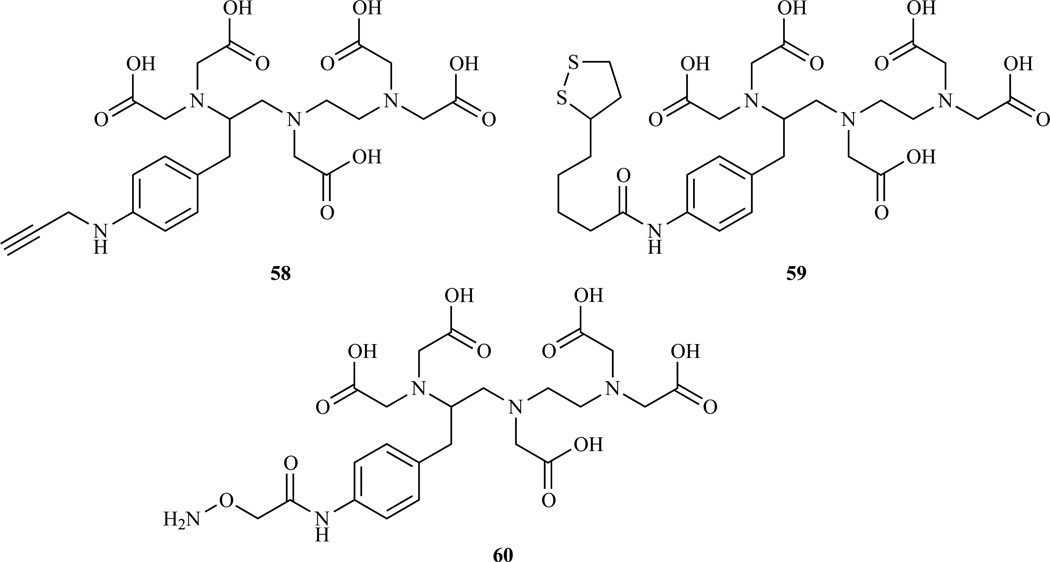

Compounds 50 (p-NH2-Bz-DTPA) and 53 (p-SCN-Bz-DTPA) have found widespread applications in MRI for labeling a variety of substrates and are now commercially available. The principal advantage of the isothiocyanate derivative lies in the fact that labeling procedure can be carried out efficiently in water under mild conditions. The amino group of p-NH2-Bz-DTPA was used to introduce alternative reactive functionalities including alkyne group [201] (58), for conjugation with azido groups through Huisgen 1,3 cycloaddtion (click chemistry), or 1,2 dithiolane moiety [202] (59) for conjugation to gold surfaces, or an aminooxy derivative (60) used for solid phase peptide labeling [203] (Chart 6).

Chart 6.

Bifunctional chelators derived from p-NH2-Bz-DTPA. 58 Ref.[201]; 59 Ref. [202]; 60 Ref.[203]

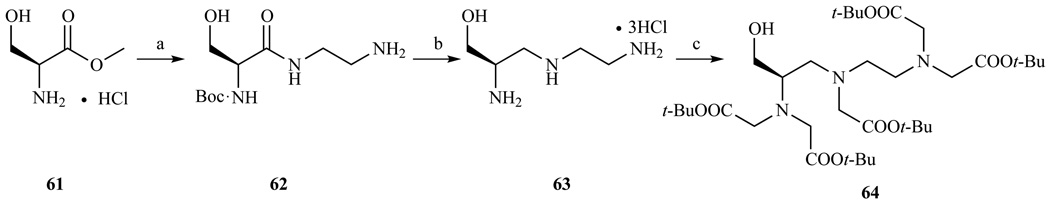

The procedure described above for the preparation of p-NH2-Bz-DTPA was modified and used for the preparation of the FDA-approved contrast agent [Gd(EOB-DTPA)(H2O)]2− (Chart 1). In this case the synthesis started with a protected L-tyrosine [194]. A hydroxymethylated derivative of DTPA was prepared by Sajiki et al. [204] using an analogous approach and adapted to a preparative scale by Amedio et al. [205] (Scheme 9). L-Serine was Boc protected and subsequently reacted with a controlled excess of ethylenediamine. Reduction was performed at room temperature with a limited excess of BH3 to avoid the reduction of the Boc group and the formation of an N-methylated byproduct. The final carboxymethylation was performed with t-Bu bromoacetate. The pendant hydroxyl group was functionalized using phosphoramidite chemistry, to prepare a series of DTPA derivatives linked to albumin binding moieties [206].

Scheme 9.

Syntehsis of 1-(R)-hydroxymethyl-DTPA, an important intermediate in the synthesis of MS-325. a) i) Boc2O, TEA, toluene, ii) ethylenediamine, 75% yield over two steps; b) BH3·THF, 77% yield; c) DIPEA, KI, DMF, BrCH2COOt-Bu, 69% yield. Ref. [205]

Compound 64 is also used for the preparation of MS325, which is commercialized in Europe as Vasovist and in the US as Ablavar. This compound binds to serum albumin in the blood and is used for blood vessel imaging.

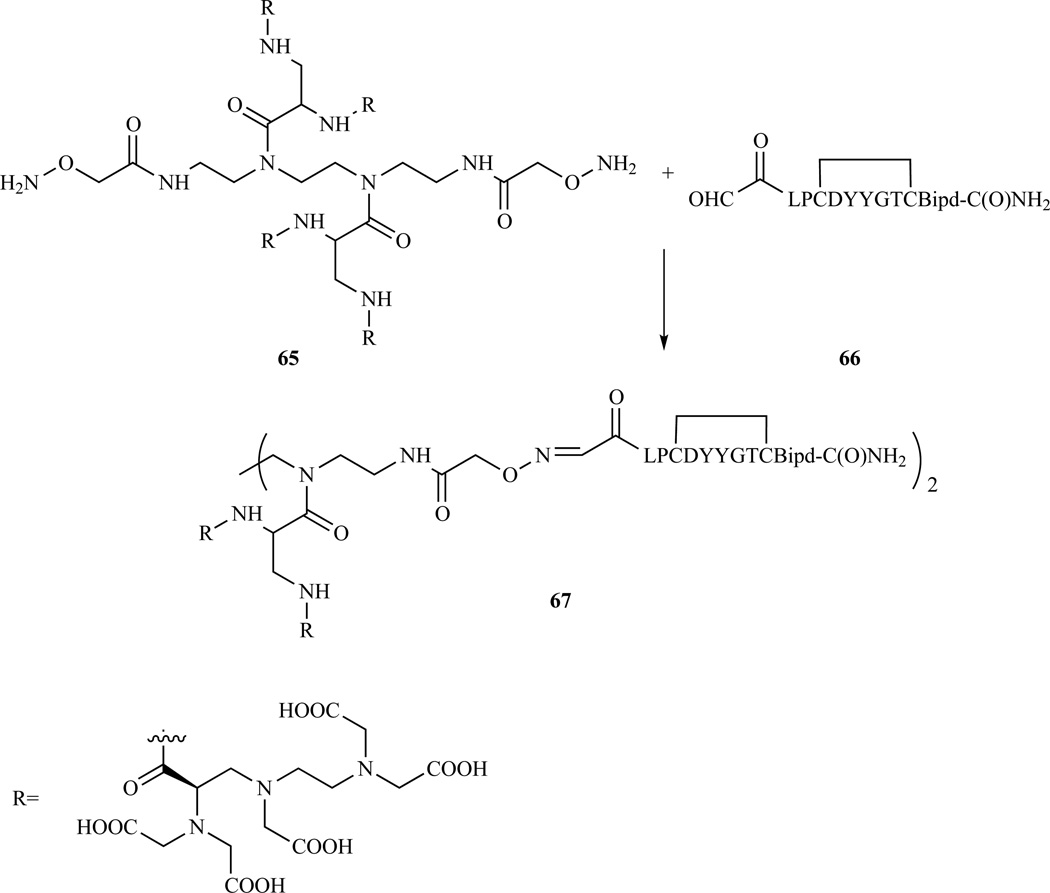

TEMPO oxidation of the hydroxyl group of compound 64 was used to prepare a DTPA derivative with a free carboxylate stemming from the ethylenediamine backbone. The carboxylate was used to link this DTPA derivative to a bifunctional tetrameric scaffold, based on triethylenetetraamine (trien). The resulting tetramer, was modified to introduce two terminal oxime functions, and was conjugated to a fibrin binding peptide (Scheme 10). The fibrin targeted peptide was extended with a serine at the N-terminus. Mild periodate oxidation generates an N-terminal α-keto aldehyde that reacts selectively and efficiently with the oxime-containing DTPA-tetramer in water [62, 96]. The resulting high-relaxivity fibrin specific probe enabled thrombus detection in an in vivo model at doses about 100 times lower than those commonly used for most MR probes.

Scheme 10.

Oxime chemistry was used to link the DTPA containing tetramer to a fibrin binding peptide. Refs. [62, 96]

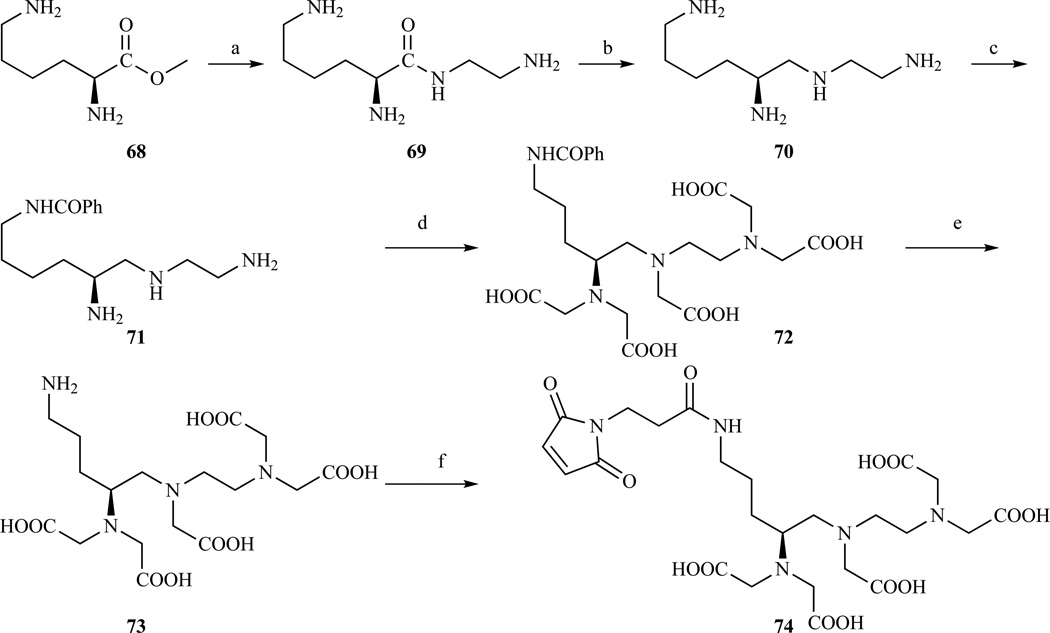

A backbone DTPA derivative bearing an aliphatic amine pendant arm was prepared by Cox et al. starting from (2S)-lysine methyl ester (Scheme 11) [207]. After reaction with a large excess of ethylenediamine, the resulting tetraamine was triprotected by forming a Cu(II) complex and the pendant amino group protected with benzoyl chloride. Cu(II) was removed by treatment with H2S to give the insoluble sulfide, and this was followed by carboxymethylation with bromoacetic acid and acid hydrolysis of the benzoyl protection to give compound 73 which was then further reacted to introduce maleimide as a thiol reactive group.

Scheme 11.

Synthesis of a DTPA derivative carrying a pendant aliphatic amino group or a pendant maleimido moiety. a) ethylenediamine, 93% yield; b) BH3·THF, 98% yield; c) (i) CuCO3(aq), (ii) benzoyl chloride, (iii) H2S, 54% yield; d) BrCH2COOH, KOH, 52% yield; e) HCl(aq); f) 3-maleimidopropionic acid N-hydroxysuccinimide ester, N-methylmorpholine, DMSO, 53% yield over two steps. Ref. [207]

Recently, procedures for the preparation of a series of enantiomerically pure DTPA derivatives starting from pure enantiomers of p-nitrophenylalanine have been reported by Benes et al. [208].

DTPA with acetate arm functionalization

As mentioned above, functionalization on the alpha carbon of one of the acetate arms does not compromise the thermodynamic stability of the complex and it is therefore preferable to the formation of DTPA monoamides.

Functionalization of a terminal acetate

Monoalkylation of diethylenetriamine with a secondary halide was the route followed by Uggeri et al. to prepare [Gd(BOPTA)(H2O)] (Chart 1), a commercial MR contrast agent with a benzyloxymethyl pendant arm emerging from one of the terminal acetate arms [209]. [Gd(BOPTA)(H2O)] has a similar thermodynamic stability as [Gd(DTPA)(H2O)] but two-fold higher relaxivity in blood due to weak protein binding.

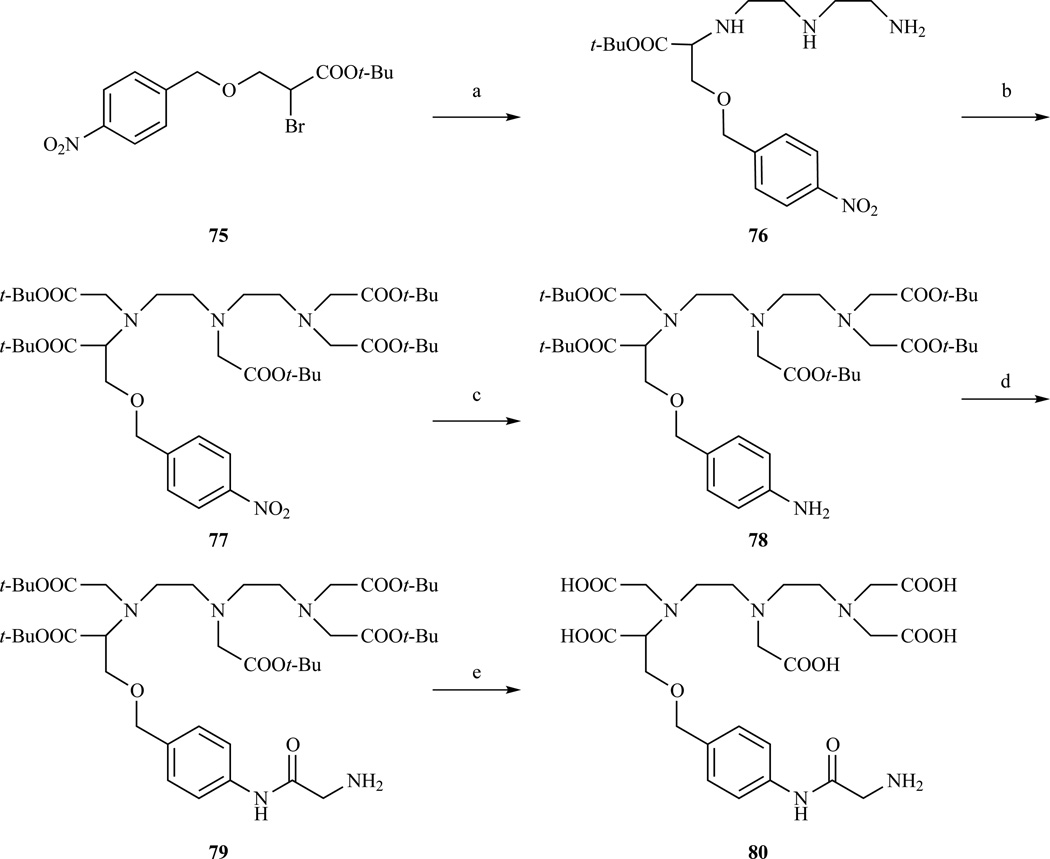

Monoalkylation of diethylenetriamine was later used by Anelli et al. to prepare a DTPA functionalizable on one of the terminal carboxymethyl arms (Scheme 12) [174]. Reaction of secondary bromide 75 with excess diethylenetriamine, afforded the monoalkylated intermediate 76. Standard carboxymethylation with t-Bu bromoacetic acid, followed by catalytic hydrogenation with Pd/C provided compound 78 with a pendant amino group which was further functionalized with glycine and the resulting product linked to a bile acid for hepatocyte targeting.

Scheme 12.

Synthesis of bifunctional DTPA derivatives with either an aromatic or aliphatic amino group for conjugation on one of the terminal acetate arms. (a) diethylenetriamine, MeCN, 81% yield; (b) BrCH2COOt-Bu, ClCH2CH2Cl, DIPEA, 61% yield; (c) H2, Pd/C, EtOH, 81% yield; (d) Boc-Gly, diethyl cyanophosphonate (DEPC), TEA, 51% yield; (e) CF3COOH, PhOMe, CH2Cl2, 99% yield. Ref. [174]

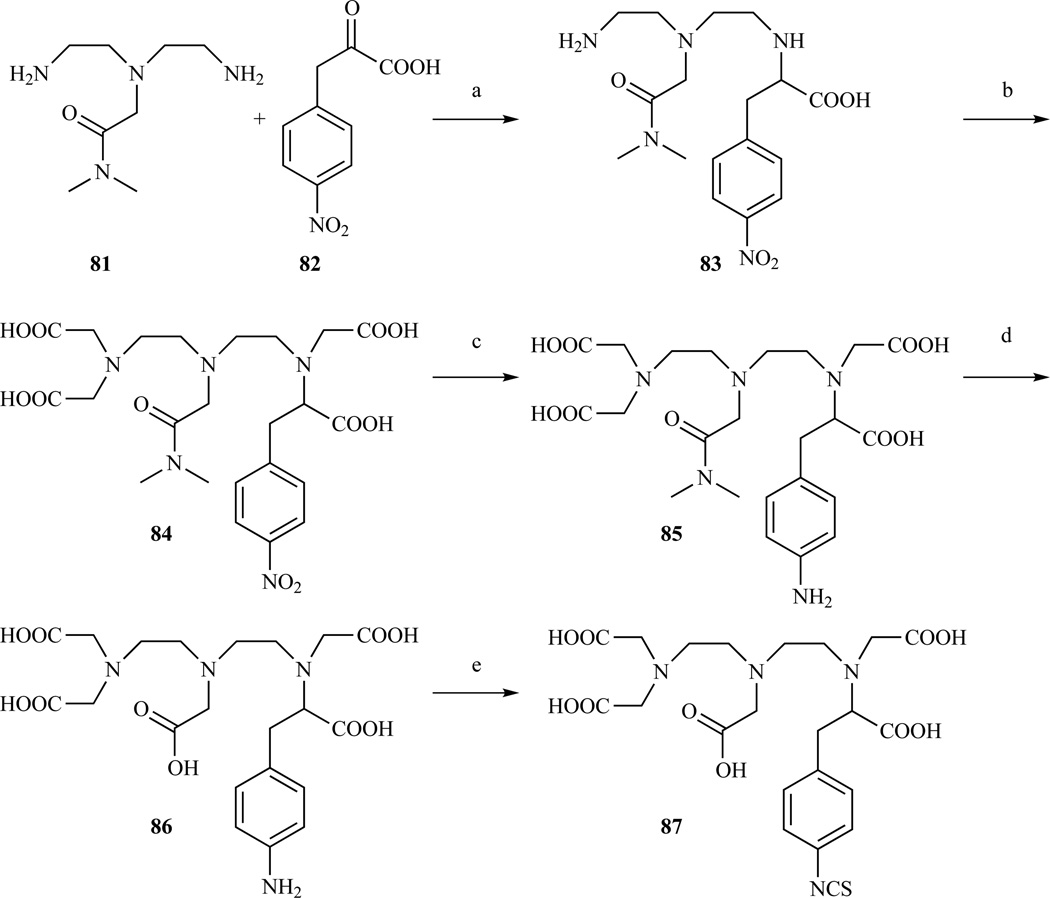

The preparation of a DTPA analog functionalizable on one of the terminal carboxymethyl arms (Chart 3, C) was proposed by Johnson et al. who developed a strategy applicable to a variety of polyaminocarboxylic ligands [210–211]. A DTPA isothiocyanate derivative was prepared in eight steps from diethylenetriamine. The secondary nitrogen was initially protected with a diethylacetamide moiety to prevent the formation of a lactam byproduct during the carboxymethylation step (Scheme 13). Reductive alkylation with p-nitrophenylpyruvic acid, followed by a standard carboxymethylation with bromoacetic acid affords the nitrobenzyl derivative 83 in low yields. Hydrogenation of the nitro group catalyzed by Pd/C followed by basic hydrolysis of the diethylacetamide group and conversion to the isothiocyanate with thiophosgene led to compound 87 in a 7% overall yield.

Scheme 13.

Synthesis of a DTPA derivative with an aromatic amino or an isothiocyanate group on one of the terminal acetate arms. a) NaBH3CN, 22% yield; b) BrCH2COOH, 55% yield; c) H2, Pd/C, H2O, 94% yield; d) NaOH(aq), 82% yield; e) CSCl2, H2O/CCl4, 92% yield. Ref. [211]

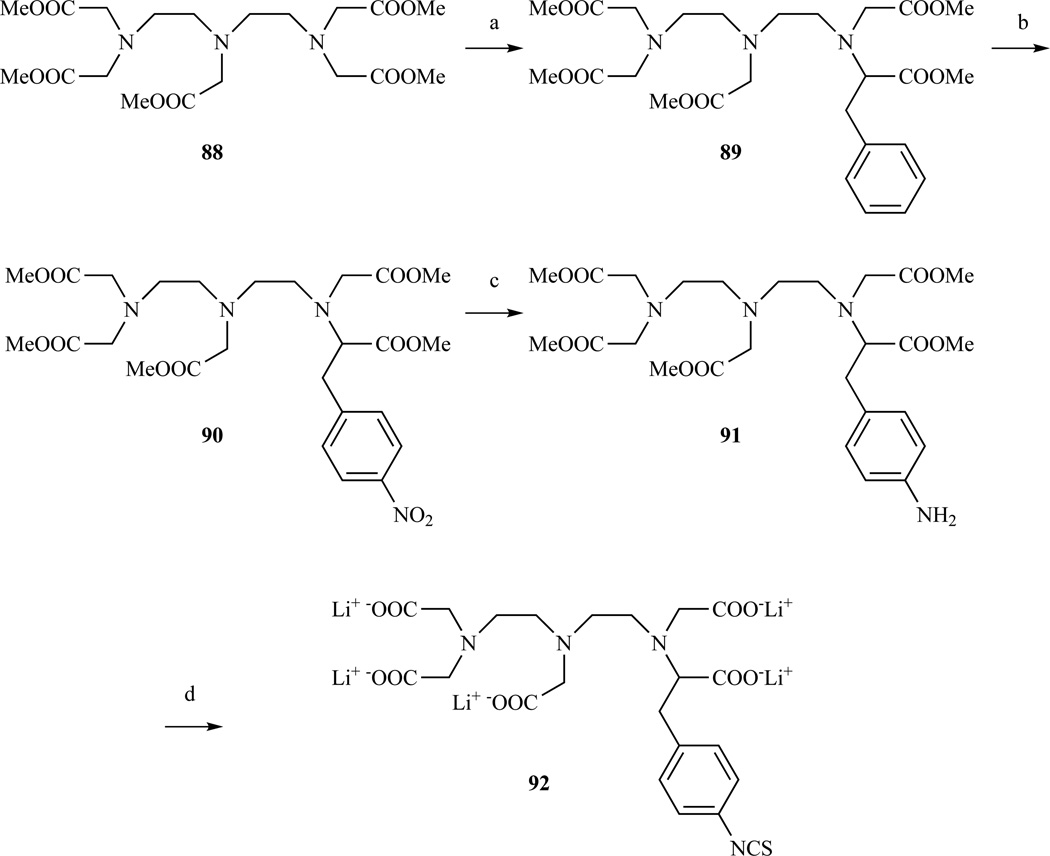

A higher yielding route to compound 87 was proposed by Keana et al. starting from DTPA methyl ester [212]. Benzylation with p-nitrobenzyl bromide of the enolate produced by deprotonation with lithium diisopropylamide (LDA) in presence of hexamethyl phosphoramide (HMPA) was unsuccessful. Mono-benzylation of the enolate was obtained with benzyl bromide and was followed by a nitration step with HNO3/H2SO4. After re-esterification, the nitro group was reduced and the methyl groups removed by saponification with LiOH. Treatment with thiophosgene gave compound 92 in a 24% overall yield (Scheme 14).

Scheme 14.

Synthesis of a DTPA derivative with an aromatic amino or an isothiocyanate group on one of the terminal acetate arms. a) LDA, benzyl bromide/HMPA, 36% yield; b) HNO3/H2SO4, 81% yield; c) H2/Pd, 100% yield; d) (i) LiOH/H2O, 100% yield; (ii) SCCl2/MeOH, 99% yield; Ref. [212]

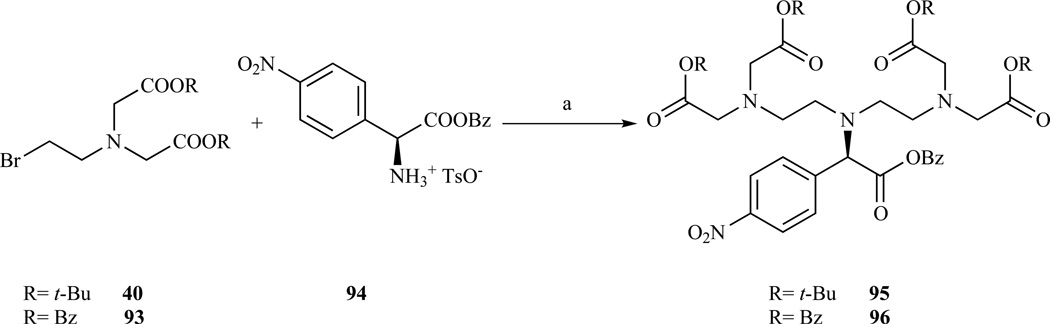

Functionalization of the central acetate

A bifunctional DTPA derivatized on the central carboxymethyl arm (Chart 3, D) was reported by Williams and Rapoport [191]. The proposed modular synthesis involves the dialkylation of 4-nitro-L-phenylalanine benzyl ester (94) with N-(bromoethyl)iminodiacetate (40, 93) in a mixture of pH 8 phosphate buffer and MeCN (Scheme 15). Phosphate buffer was preferred to aqueous bicarbonate to prevent the formation of a carbamate byproduct. 4-nitro-L-phenylalanine benzyl ester 94 was prepared by nitration of L-phenylalanine followed by benzyl protection of the carboxylate. N-(bromoethyl)iminodiacetates 40 and 93 were prepared in two steps from 2-ethanolamine by alkylation with benzyl or t-Bu bromoacetate followed by bromination with NBS/TPP. No evidence of base catalyzed epimerization during the di-alkylation step was found. A small amount of racemization was observed during the nitration of phenylalanine.

Scheme 15.

Synthesis of a DTPA derivative functionalized on the central acetate arm. a) MeCN/phosphate buffer pH 8, 55–59% yield. Compounds 95 and 96 can be reduced with H2, Pd/C in HCl(aq)/MeOH. Ref. [191]

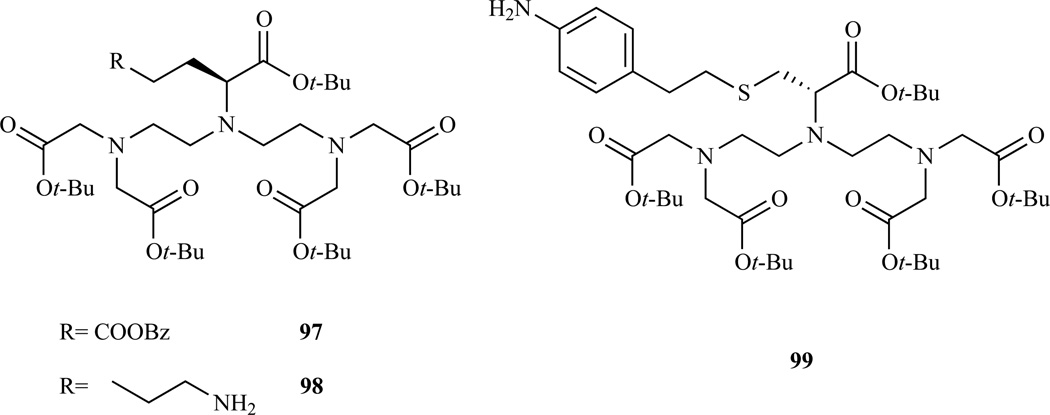

The procedure in Scheme 15 can be adapted to the preparation of a variety of DTPA derivatives using a different α-amino acid ester. In this way, Anelli et al. prepared derivatives 97 and 98 (Chart 7) starting from L-glutamic acid and L-lysine [190]. Similarly, Choi et al. prepared an analogous product starting from cysteine (Chart 7, 99) [213]. Compound 97 was conjugated with different cholic acids and investigated as a potential hepatospecific or intravascular MR probe [174, 214].

Chart 7.

Structures of DTPA analogues derivatized on the central acetic arm, following the procedure developed by Williams and Rapoport. 97 and 98 Ref. [190], 99 Ref. [213]

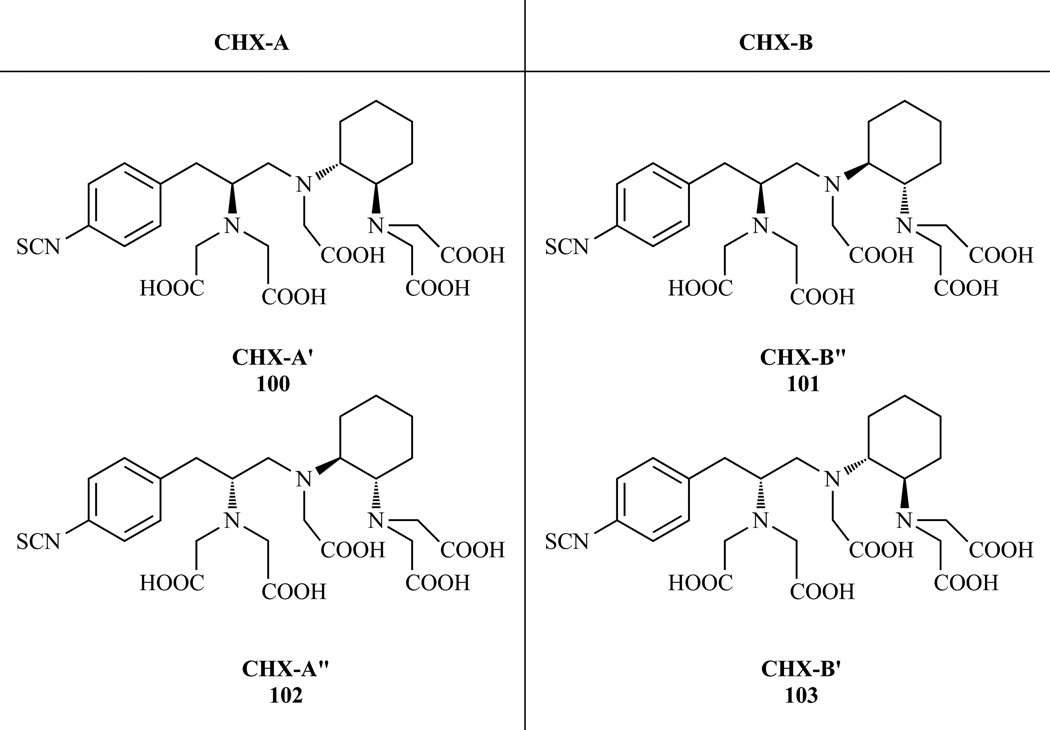

Modified DTPA chelators

A more rigid bifunctional analogue of DTPA containing a fused cyclohexyl ring into the ligand backbone (CHX-DTPA) and a pendant p-isothiocyanatobenzyl moiety was synthesized by Brechbiel et al. [215–216] The initial preparation was carried out with racemic p-nitrophenylalanine and (±)-trans-cyclohexane-1,2-diamine. Two pairs of enantiomers were isolated and termed CHX-A and CHX-B (Chart 8). The cyclohexanediamine serves to pre-organize the ligand to a metal binding conformation. This results in lanthanide complexes that are 100 times more stable than the analogous DTPA complex and about 1000 times more inert to acid assisted metal dissociation [171, 193].

Chart 8.

Structures of the four stereoisomers of p-SCN-Bz-CHX-DTPA obtained from racemic p-nitrophenylalanine and (±)-trans-cyclohexane-1,2-diamine. Ref. [215–216]

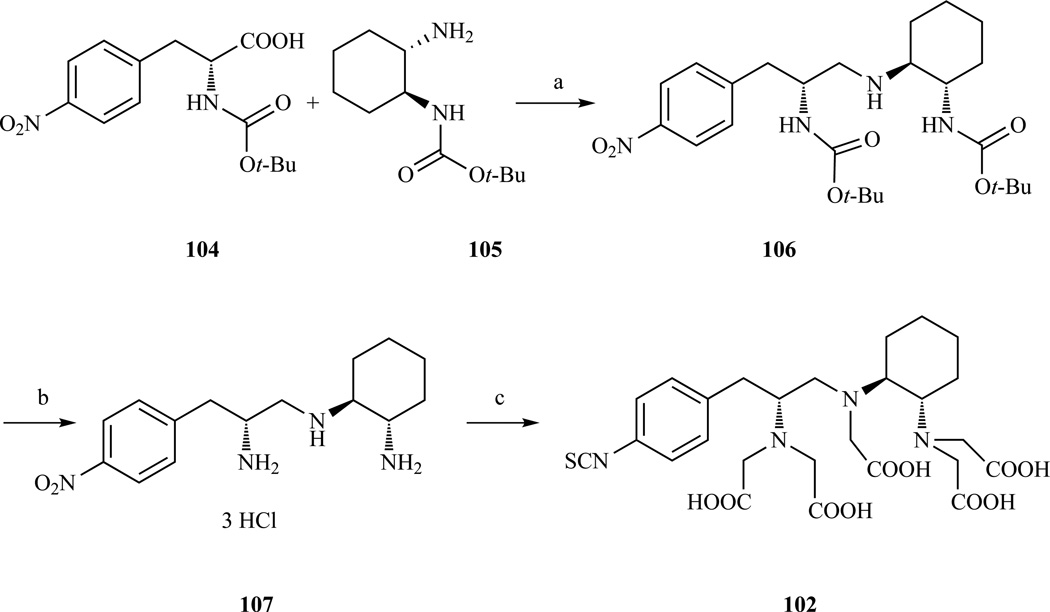

The four stereoisomers of 2-(p-nitrobenzyl)-trans-CHX-DTPA were later prepared individually by using enantiomerically pure starting materials and following the path exemplified for CHX-A” (Scheme 16). The use of Boc cyclohexane-1,2-diamine was preferred to the Cbz protection [217]. Interestingly, it was found that the in vivo kinetic stability of 88Y(III) CHX-B enantiomers was significantly lower than the 88Y(III) CHX-A enantiomers, making them less suited for in-vivo applications [218]. This finding prompted the investigation of the influence of the absolute stereochemical configuration on the in vivo stability. Bone uptake experiments with 88Y(III) complexes confirmed that CHX-A enantiomers are more kinetically inert than CHX-B enantiomers (dissociated Y(III) targets the bone). There was also a small but significant difference between CHX-A’ and CHX-A”, with CHX-A” being slightly more inert than CHX-A’. It is very likely that the Gd(III) analogs display the same trends in terms of stability and inertness to metal substitution.

Scheme 16.

Synthesis of CHX-A’’, among the four stereoisomers of p-SCN-Bz-CHX-DTPA it forms the most stable metal chelates. a) HOBT, EDC, 86% yield; b) (i) HCl/dioxane, (ii) BH3·THF, (iii) HCl/dioxane; c) (i) BrCH2COOt-Bu, Na2CO3, 23% yield over 4 steps (ii) TFA, (iii) H2, Pd/C, (iv) CSCl2, H2O/CHCl3. Ref. [217]

Recently, a thiol reactive maleimido derivative of CHX-A” was prepared by coupling the t-Bu ester protected p-amino functionalized CHX-A” DTPA with N-ε-maleimidocaproic acid. Michael addition between a thiol and the maleimido moiety occurs efficiently and specifically. Since cysteine thiol groups can be genetically engineered into proteins, this BFC offers control over the labeling site compared to labeling more ubiquitous lysine residues [219–220].

DOTA derivatives

In MRI, the macrocyclic agents that are currently used in clinical practice, are derived from cyclen (1,4,7,10 tetraazacyclododecane) by alkylation of the four nitrogens with suitable chelating arms. The first macrocyclic MR contrast agent approved for commercial use (in Europe) was [Gd(DOTA)(H2O)]− (Chart 1). The rigidity and the preorganization provided by the macrocyclic ring, as well as the good correspondence between the macrocyclic cavity and the Gd(III) ionic radius, lead to the formation of a highly stable Gd(III) complex (Kf = 1025.3 [221]). Additionally, the macrocyclic ring in the complex adopts a conformation that hinders the entry of a proton slowing down the dissociative process and making the complex kinetically inert. For this reason, a large number of DOTA derivatives have been prepared to improve its already favorable properties or to render it bifunctional. It should be noted that the excellent stability and kinetic inertness of GdDOTA derivatives is limited to compounds based on the cyclen macrocycle. Increasing the macrocycle ring size by one or two carbons results in Gd(III) complexes that are 5 – 10 orders of magnitude less stable than GdDOTA [222] and 3 – 6 orders of magnitude more labile [223].

The preparation of macrocyclic ligands has been the subject of an excellent review written by Desreux and Jacques and more recently the preparation of N-functionalized cyclen ligands has been comprehensively reviewed by Suchy et al. [224].

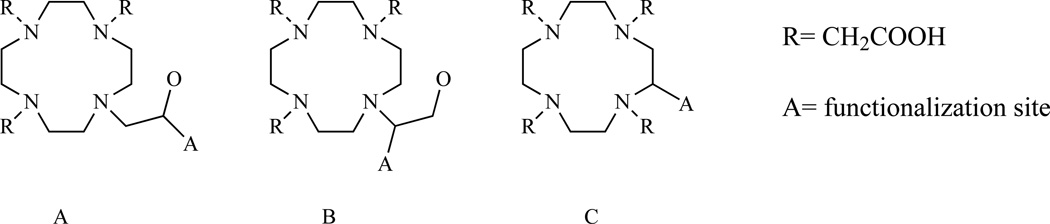

Here our attention is focusing specifically toward the preparation of bifunctional chelators. With this objective in mind, modification of the ligand structure to introduce an easily functionalizable group can occur at one of the carbons of the macrocyclic ring (Chart 9, C) or on one of the chelating arms. (Chart 9, A, B)

Chart 9.

Generic structures of monofunctionalized DOTA analogues

The simplest way to link a DOTA derivative to selected substrates, is by functionalizing the secondary nitrogen of commericially available DO3A esters (DO3A= 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7-tris-acetic acid). However, the removal of one coordinating arm reduces the thermodynamic formation constant by more than four orders of magnitude and renders the GdDO3A complex much more kinetically labile as compared to GdDOTA [221, 225–226]. Furthermore, Gd(III) complexes of DO3A derivatives show a relatively high affinity for endogenous anions, which results in displacement of the coordinated water and consequent quenching of the relaxivity [227].

The largest number of bifunctional derivatives of DOTA has been obtained by derivatizing one of the carboxylic groups into a carboxyamido derivative. The replacement of one carboxylate with one carboxyamido group does not reduce the thermodynamic formation constant [228] as much as in GdDO3A, and the kinetic inertness remains excellent [229]. Conversion of a carboxylato into a carboxyamido group results in a decrease in the overall charge of the complex, and also results in a decrease of the exchange rate of the coordinated water. This is disadvantageous for agents designed for low field applications, but has less impact on the relaxivity at higher fields [230].

DOTA - monoamides

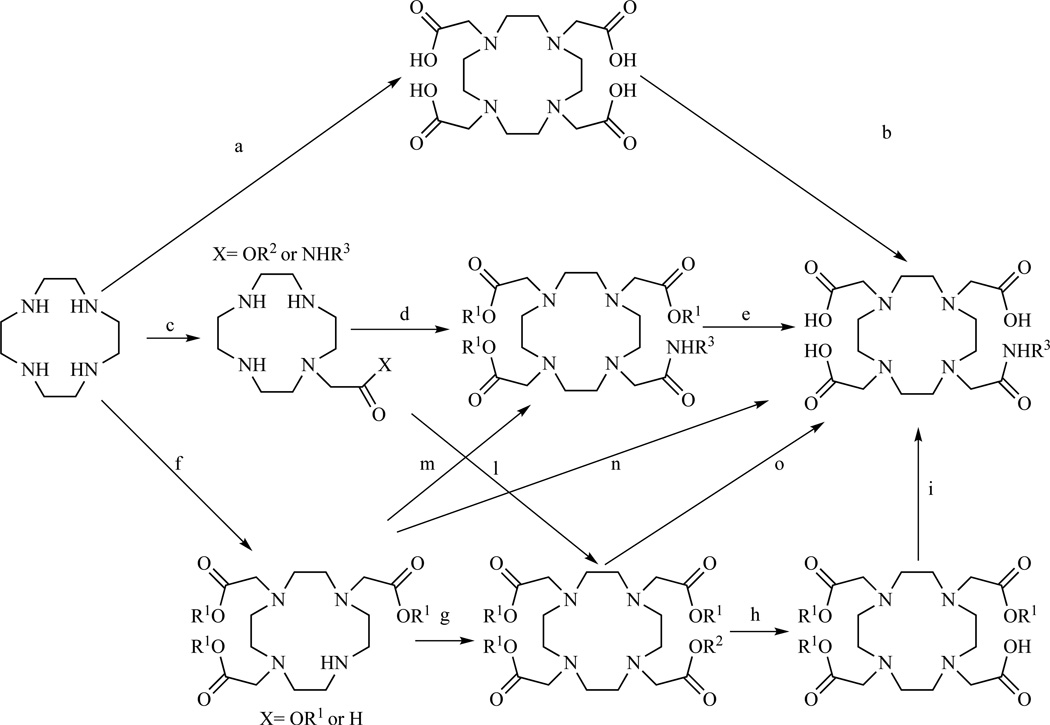

In general, the strategies that have been used for the preparation of DO3A monoamides are summarized in Scheme 17. These approaches differ in number of steps, yields and ease of purification.

Scheme 17.

Schematic representation of the various strategies used to prepare DOTA monoamides.

The preparation of DOTA monoamides by mono-activation of DOTA (Scheme 17, a,b) with isobutyl chloroformate [231–233], with DCC [234] or by preparation of a sulfo-NHS active ester [235–236] followed by reaction with an amine has been proposed. However, the main drawback of this strategy is the formation of statistical mixtures of activated carboxylates.

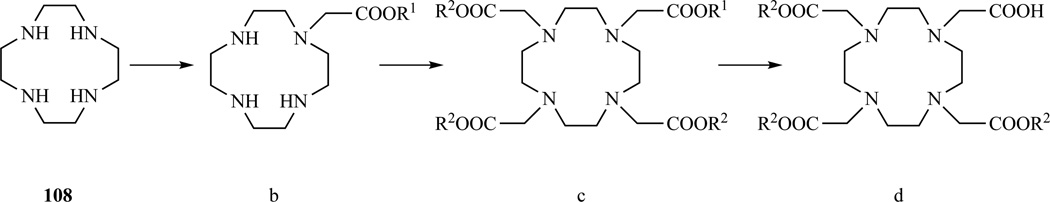

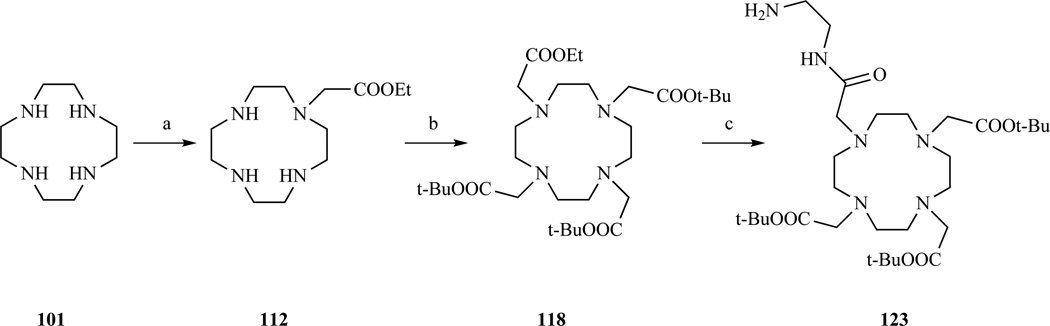

Alternatively, to reduce the formation of byproducts a suitable alkylating agent can be reacted with an excess of cyclen to produce the mono-acetate or the mono-acetamido derivative. This route (Scheme 17, c,h,l,i) has been used by Heppeler et al. who prepared compound 119 (tris-t-Bu DOTA), an extremely useful bifunctional chelator, which has been applied extensively to the preparation of a variety of DOTA monoamides and is now commercially available [237]. Compound 119 was obtained in three steps in a 63% overall yield according to the procedure outlined in Scheme 18 and was subsequently conjugated with a somatostatin analogue.

Scheme 18.

General reaction scheme for the formation of DOTA triesters with a variety of protection schemes. b) 109 R1=Bz[234, 237]; 110 R1=t-Bu [238–239], 111 R1= allyl [234], 112 R1=Et [240]; c) 113 R1=Bz R2=t-Bu [234, 237], 114 R1=t-Bu R2=Bz [238], 115 R1=allyl R2=Bz [234], 116 R1= allyl R2= p-nitrobenzyl [234], 117 R1= t-Bu R2= allyl [239], 118 R1=Et R2=t-Bu [240]; d) 119 R2= t-Bu [234, 237, 240], 120 R2= Bz [238], 121 R2= p-nitrobenzyl [234], 122 R2= allyl [239].

Several other protection schemes (Scheme 18) have been obtained following analogous procedures, including the DOTA tris-(phenylmethyl) ester prepared by Anelli et al. [238] and Wängler [234], the DOTA tris-(4-nitrobenzyl) ester [234] and the DOTA tris-allyl [239] in order to provide a valid alternative in case the final conjugate could not survive the strongly acidic conditions necessary for t-Bu deprotection. The main disadvantages of the monoalkylation route are the need for an excess of cyclen and the possibility of multiple alkylation taking place.

These concerns have been addressed either by protecting the cyclen ring before the alkylation step [240], or by carrying out the synthesis on solid phase [241–243]. Tris-t-Bu DOTA was obtained by Kohl et al. [240] (Scheme 18) by previous protection of three cyclen nitrogen with Mo(CO)6 according to a procedure described by Patinec et al. [244–245] to give the air and moisture sensitive tricarbonylmolibdenum complex. The protected cyclen was then alkylated with ethyl bromoacetate and the cyclen nitrogens deprotected under strongly acidic conditions. From intermediate 112, tris-t-Bu DOTA was prepared in two steps using standard procedures.

A variety of methodologies for the mono, bis and tris-protection of cyclen have been developed over the years. The description of these methodologies is outside the scope of this review, but an excellent overview of the field has been compiled by Jacques and Desreux [246].

Tris-t-Bu DOTA and tris-benzyl DOTA were prepared by Oliver et al. [242] on solid phase, using a bromoacetate 2-chlorotrityl resin. The resin was loaded with cyclen and then the remaining free secondary nitrogens of the resin bound cyclen were alkylated with t-Bu or benzyl bromoacetate. The final products (119, 120) were cleaved under mildly acidic conditions with trifluoroethanol. With this procedure the excess of cyclen can be recovered by a simple filtration and recycled and desired products can be obtained in high purity after filtration and evaporation without the need for further purification. The other advantage of this procedure arises from working under pseudo-high dilution conditions which prevents the formation of multiply alkylated cyclen species.

Monoalkylation of cyclen has also been used to introduce a methylcarboxyamido moiety bearing a secondary reactive functionality. DOTA monoamides with a functionalizable amino group were prepared by André et al. [247] (Scheme 17, c,l,o and Scheme 19) who synthesized a t-Bu/ethyl orthogonally protected DOTA and then reacted it with a large excess of ethylenediamine. A series of thiol reactive DOTA monoamides were prepared by Haussinger et al.[248] and used for protein paramagnetic tagging.

Scheme 19.

Synthesis of a DO3A monoamide carrying a reactive aliphatic amine. a) BrCH2COOEt, CH2Cl2, 79% yield; b) BrCH2COOt-Bu, K2CO3, CH3CN, 84% yield; c) ethylenediamine, 68% yield. Ref. [247]

One example of a bifunctional DOTA monoamide prepared according to path c,d,e in Scheme 17 was shown by Riley and McGhee who monoalkylated cyclen with a bromoacetamide bearing a Boc protected aliphatic amine [249]. Exhaustive cyclen alkylation with benzyl bromoacetate followed by Boc deprotection produced a bifunctional ligand with a pendant amine.

The majority of DOTA monoamides are prepared starting from DO3A t-Bu ester (Scheme 17 f,g,h,i). Following this general route, tris-t-Bu DOTA was prepared by Aarons et al. [250] and Li et al. [251–252] using different protection schemes (Scheme 20).

Scheme 20.

General reaction scheme for the formation of DOTA tris-esters by alkylation of DO3A triesters a) 124 R1= t-Bu; b) 118 R1= t-Bu, R2=Et [251–252]; 113 R1= t-Bu, R2=Bz [250]; c) R1= t-Bu 119.

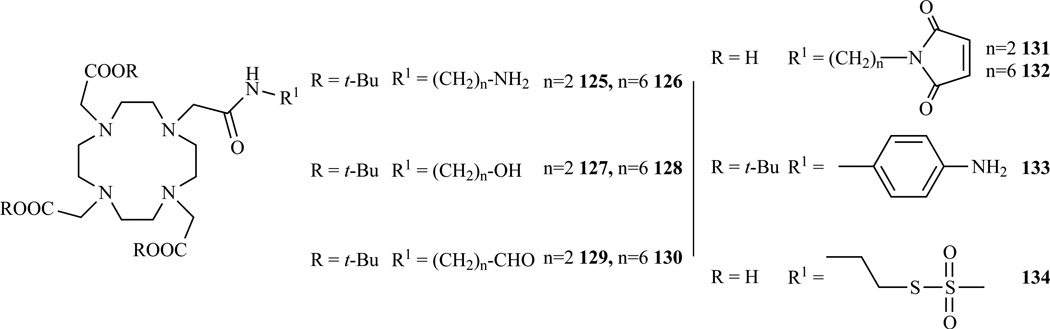

Alkylation of t-Bu DO3A (Scheme 17 f,m,e) was also used by Barge et al. [253] to prepare DO3A monoamides bearing amino, maleimido, hydroxyl and formyl pendant arms with different spacer lengths. The synthesis of all the adducts shares the same basic strategy. t-Bu DO3A was alkylated with a custom prepared bromoacetamide bearing either a protected amine or alcohol. After deprotection of the side arm the amino derivatives (125–126) were converted to the maleimido derivative by reaction with 7-exo-oxohimic anhydride under microwave irradiation (131–132). The alcohol derivatives (127–128) were converted into the corresponding aldehyde by Swern oxidation (129–130). Variants with a free aromatic amine [254] (133) and with a thiol reactive methanethiosulfonate group [255] (134) were prepared by Natrajan et al. and Thonon et al., respectively.

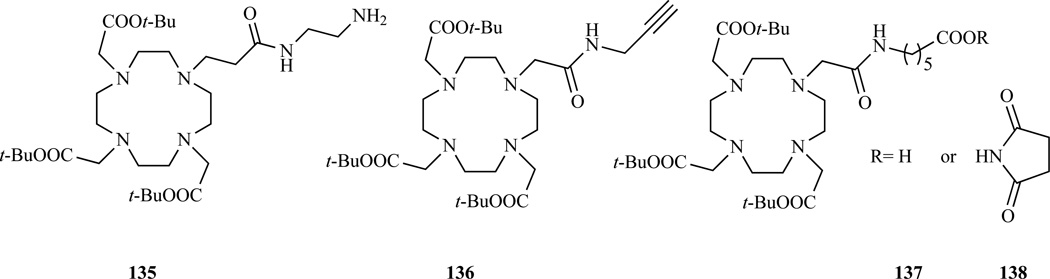

Interestingly, Tei et al. [256] showed that increasing the length of the carboxyamide arm of a GdDOTA monoamide from two to three carbon atoms (Chart 11, 135) results in Gd(III) complexes with a water exchange rate almost two orders of magnitude faster than the parent DOTA monoamide.

Chart 11.

Structure of bifunctional DOTA monoamides. 135 [256]; 136 [256–258]; 137–138 [259].

Direct alkylation of unprotected DO3A (Scheme 17, f,n) was used by the Lu’s group to prepare DOTA monoamides bearing a terminal amino group [102, 124] in one step.

Tris t-Bu DOTA (119) has been widely used to tag peptides, proteins, dendrimers, to form bimodal probes, or as a starting material to prepare bifunctional ligands with a different functionalizable moiety. Coupling of tris-t-Bu DOTA can be accomplished using a variety of amide coupling agents or by using an activated ester. Most commonly, pentafluorophenol (PFP) or N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) esters have been used.

A DOTA monoamide bearing a terminal alkyne functionality, designed for Cu(I)-mediated azide–alkyne cycloaddition has been prepared by Mindt et al. [256] by reaction of the tris-t-Bu DOTA NHS ester with propargylamine. Earlier the same compound was prepared by Viguier et al.[257] and Prashun et al. [258] by alkylating DO3A t-Bu ester with N-(2-propynyl)chloro- or bromo-acetamide (Chart 11, 136).

Functionalization of tris-t-Bu DOTA has been exploited by Aime et al. [259] to introduce a spacer carrying a free terminal carboxyl group which, after transformation into the NHS ester, was coupled to glutamine (Chart 11, 137, 138). The resulting complex was used to study cellular uptake through the amino acid transporting system.

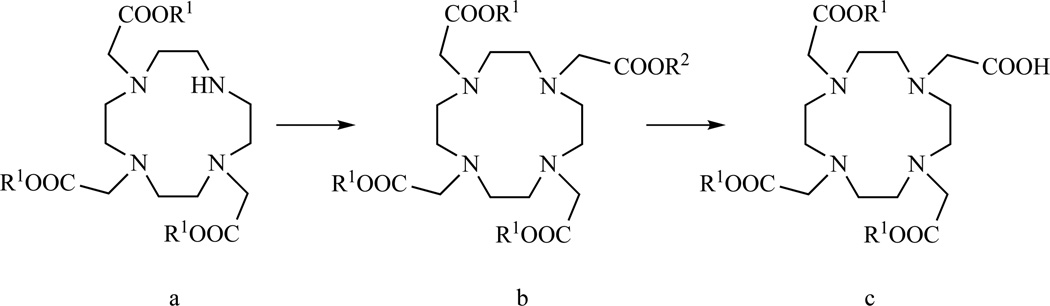

DOTA substituted at the acetate α-carbon or the macrocyclic ring

Like the DTPA bifunctional ligands, the site for conjugation can also be introduced at the acetate α-carbon or the macrocyclic ring backbone. The benefit of this approach is that the stable GdDOTA core is preserved with all four anionic oxygen donors. Furthermore, derivatization on the one acetate α-carbon or on the ring is not accompanied by the lengthening of the mean residence lifetime (τM) of the coordinated water molecule that is observed in the case of DOTA monoamide derivatives.

DOTA and DOTA derivative Gd(III) complexes are present in solution as a mixture of stereoisomers that originate from the helicity of the ring conformation and the orientation of the acetate arms [26]. The coordination geometry of the complex is defined by the torsion angle between the plane formed by the four nitrogens and the plane formed by the four oxygens. GdDOTA exhibits two different coordination geometries, which are defined as square antiprism (SAP, torsion angle between the two planes ca 39°) and twisted square antiprism (TSAP, torsion angle between the two planes ca −25°). In both SAP and TSAP conformations, the arms can assume either a Δ or Λ orientation and the ring can assume a (δδδδ) or a (λλλλ) conformation. Therefore four coordination geometries can exist and are designated as Δ(δδδδ) and Λ(λλλλ) (TSAP) or Δ(λλλλ) and Λ(δδδδ) (SAP). Thus there are four diastereoisomers, two pairs of enantiomers, which can interconvert in solution by either cooperative ring inversion or (λλλλ⇆δδδδ) or concerted arm rotation (Δ⇆Λ).

The introduction of a chiral center on one acetate α-carbon also results in four possible diastereoisomers upon chelation (eight for racemic mixtures). However, it has been shown that the presence of the substituent on the acetate α-carbon slows the acetate arm rotation and results in only two diastereoisomers being observed (four for racemic mixtures) [260–262]. It appears that the configuration at the stereogenic carbon determines the least sterically hindered helical form of the complex. Substitution on the ring has a similar effect, by slowing down the ring inversion. Thus, again, only one half of the expected diastereoisomers are observed [262].

However, while substitution on one acetate α-carbon is accompanied by an increase in the formation constant and by a decrease in the rate of complex dissociation, compared to unsubstituted [Gd(DOTA)(H2O)]−, substitution on the ring results in a slightly more labile complex with slightly lower thermodynamic stability [261–262]. Even so, the stability of this class of complexes is sufficiently high for in vivo applications.

Acetate α–carbon substitution

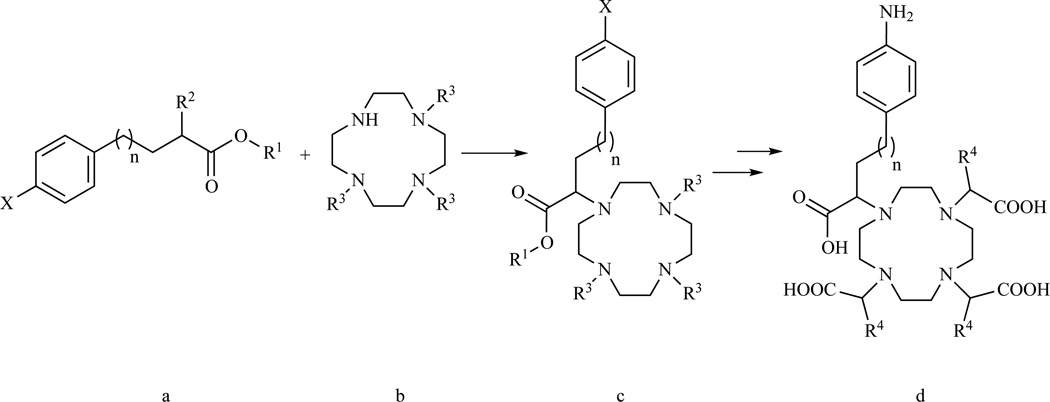

The preparation of DOTA derivatives with one substituted acetate α-carbon can be accomplished by reaction of a suitable secondary halide, triflate, or other leaving group either directly with an excess of cyclen or with t-Bu-DO3A.

Reaction of a secondary bromide [263–265] or triflate [263, 266] bearing a p-nitrobenzyl or a phenyl group with an excess of cyclen [263–264] or a DO3A ester [265–266] have been used to prepare DOTA derivatives bearing a p-nitrobenzyl moiety (Scheme 21). In one instance, Ansari et al. reported that using a p-nitrobenzyl derivative as a starting material resulted in β-elimination during the cyclen alkylation step [266]. For this reason they first introduced the benzyl group and then performed the nitration on the monoalkylated cyclen product. The aromatic amine can be converted to an isothiocyanate group by reaction with thiophosgene.

Scheme 21.

General synthetic path for the synthesis of DOTA derivatives with a pendant aromatic amine for conjugation. a) 139 n=2, R1=Et, R2=SO2CF3, X=H [266]; 140 n=3, R1=Me, R2=Br, X=NO2 [265]; 141 n=2, R1=Me, R2=Br, X=NO2 [263–264]; 142 n=2, R1=iPr, R2=Br, X=NO2 [263]; b) 108 R3=H [263–264]; 143 R3=CH2COOEt [266]; 144 R3=CH2COOMe [265]; c) 145 n=2, R1=Et, R3=CH2COOEt, X=H [266]; 146 n=3, R1=Me, R3=CH2COOMe, X=NO2 [265]; 147 n=2, R1=Me, R3=H, X=NO2 [263–264]; 148 n=2, R1=iPr, R3=H, X=NO2 [263]; d) 149 n=2 R4=H [263–264, 266]; 150 n=3 R4=H [265]; 151 n=3 R4=Me [263].

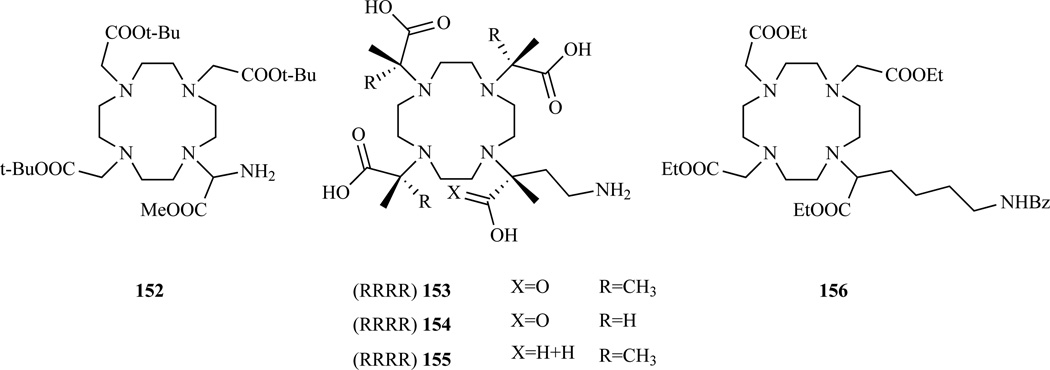

Bifunctional ligands presenting a more reactive aliphatic primary amine were prepared by Cox et al. [207] starting from (±)-6-benzamido-2-bromohexanoate (Chart 12, 156), Yoo et al. [267–268] (Chart 12, 152) starting from α-brominated glycine and Grotjahn et al. [269] (Chart 12, 153–155) starting from S-(4)-amino-hydroxybutyric acid following procedures similar to those outlined above.

Chart 12.

Bifunctional chelators functionalized with a pendant aliphatic amine on the acetate alpha carbon. 152 Ref. [267–268]; 153–155 Ref. [269]; 156 Ref. [207].

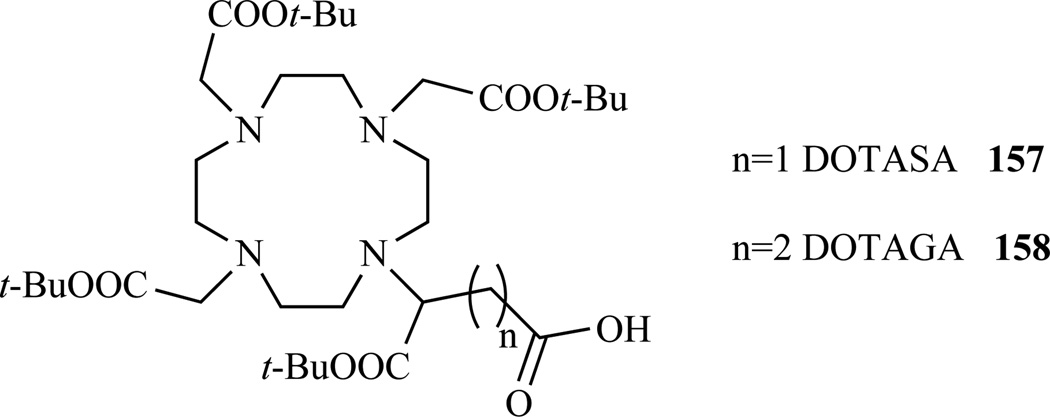

Two useful bifunctional chelators, with a free carboxylate group for functionalization, were prepared by Eisenwiener et al. starting from commercially available L-aspartic or L-glutamic acid [270]. DOTAGA(t-Bu)4 (157) was obtained in a 20% overall yield and DOTASA(t-Bu)4 (158) was obtained in a 2% overall yield over 5 steps (Chart 13).

Chart 13.

Structure of the bifunctional chelators DOTAGA and DOTASA. Ref. [270]

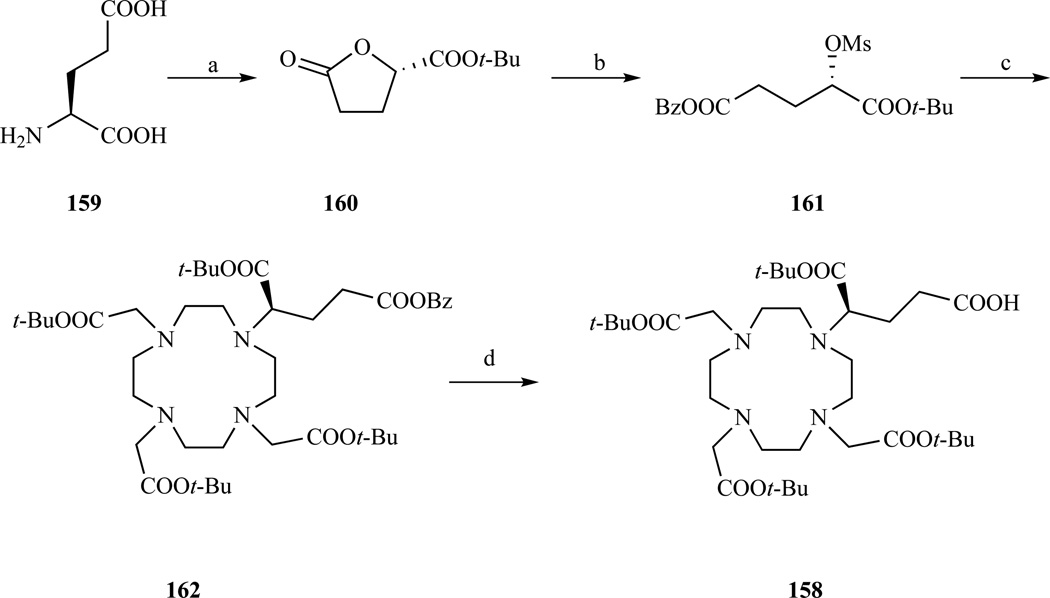

Recently a multigram scale synthesis of DOTAGA(t-Bu) with an improved yield of 30% and high optical purity over 8 steps became available. Levy et al. demonstrated that the DOTAGA(t-Bu) prepared with the procedure developed by Eisenwiener et al. was a 2:1 mixture of enantiomers [271]. It was argued that to avoid racemization an alkylating agent more reactive than a secondary bromide was necessary. This agent was identified as the mesylate 161, which contrary to the triflate analogue, could be isolated and obviated the need to work at very low temperatures. Following the procedure outlined in Scheme 22 DOTAGA(t-Bu) was obtained with an ee=99.0%.

Scheme 22.

Optimized multigram asymmetric synthesis of the bifunctional chelator DOTAGA. a) (i) HCl/NaNO2, (ii) (COCl)2 / cat. DMF, (iii) t-BuOH, 2,6 lutidine, 59% yield over three steps; b) (i) KOH, THF, (ii) BzBr, DMF, (iii) MsCl, TEA; c) (i) cyclen, K2CO3, (ii) BrCH2COOt-Bu, K2CO3, CH3CN, 52% yield over five steps; d) H2, Pd/C, MeOH, 98% yield. Ref. [271]

The DOTAGA BFC was used in the synthesis of EP-2104R, a fibrin targeted contrast agent that was used in clinical trials for thrombus imaging [67][273]. EP-2104R enabled the detection of thrombi that were not visible in precontrast images. Ligand exchange studies [66] revealed that this compound was much more inert to Gd removal than GdHP-DO3A, GdDTPA, or GdDTPA-BMA (Chart 1).

DOTAGA(t-Bu) was also used as starting material for the synthesis of a bifunctional Gd(III) complex which showed a pH modulated relaxivity. The complex features an alkyne moiety for Cu(I)- mediated azide–alkyne cycloaddition and was used for the preparation of a pH responsive MR/PET bimodal agent [272].

Ring substitution

The preparation of bifunctional chelators functionalized on a ring carbon requires the de novo assembly of the macrocyclic ring. Methodologies for the synthesis of macrocyclic polyamines have been throughly reviewed in the past [246]. The most widely used procedure used for the synthesis of macrocyclic polyamines, including cyclen derivatives, is the Richman-Atkins synthesis. This procedure involves the reaction of a terminal bis-tosylamide with alkyl tosylates and results in a high degree of cyclization due to the good nucleofugal nature of the p-toluenesulfonates and to the low reduction in entropy occurring as a result of the macrocyclization process.

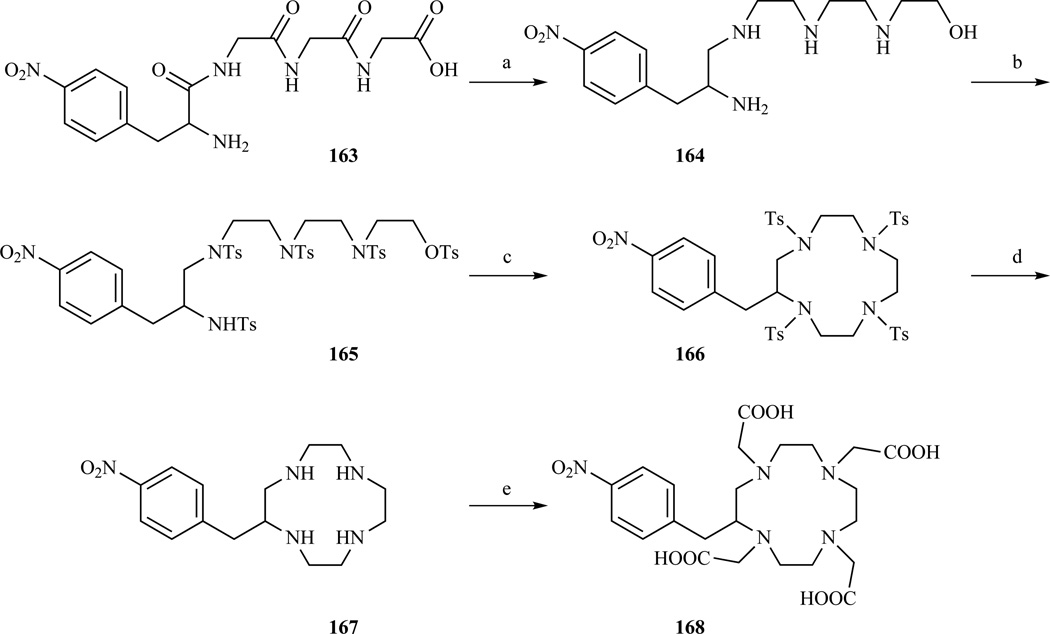

Exploiting an intramolecular version of the Richman-Atkins protocol Moi et al. prepared a p-nitrobenzyl derivative of DOTA (Scheme 23, 168) [273]. Instead of using a bimolecular approach, in this case a linear polyaminoalcohol was prepared from α-amino acids. After amide reduction and exhaustive tosylation, the intramolecular cyclization step between the two termini proceeded with a 79% yield.

Scheme 23.

Synthesis of 2-p-(nitrobenzyl) DOTA using intramolecular Richman-Atkins macrocyclization. a) BH3·THF, 65% yield; b) Toluenesulfonyl chloride, TEA, CH3CN, 49% yield; c) Cs2CO3, DMF, 79% yield; d) H2SO4, C6H5OH 91% yield; e) BrCH2COOH, pH 10, 58% yield. Ref. [273]

Alternative routes for the preparation of the same p-nitro benzyl derivative which was subsequently reduced to the amine, have been proposed by Takenouchi et al. [274] who prepared the macrocycle by bimolecular cyclization between an imino diester and a polyamine without particular protection and by McMurry et al. [275–276] who used the reaction between a di-succinimido ester and a diamine to prepare the same compound and two more rigid derivatives.

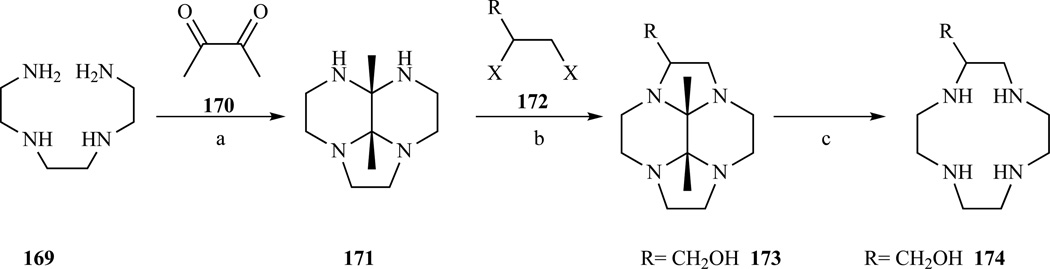

The preparation of carbon functionalized tetraazamacrocycles, including cyclen, were reported by Boschetti et al. using a bisaminal template approach [277–278]. One pot reaction of the tricyclic bisaminal derivative with dihalogenated or ditosylated ethane derivatives bearing a hydroxyl functional group afforded the C-substituted tetraazamacrocycle (Scheme 24).

Scheme 24.

Synthesis of backbone functionalized cyclen via bisaminal chemistry. a) CH3CN; b) X=Br or OTs, CH3CN; c) HCl(aq), 20–52% yield over three steps. Ref. [277–278]

DO3A derivatives with fourth chelating arm other than carboxylate

A few examples of bifunctional chelators, derived from cyclen but with chelating arms other than carboxymethyl, are worth mentioning.

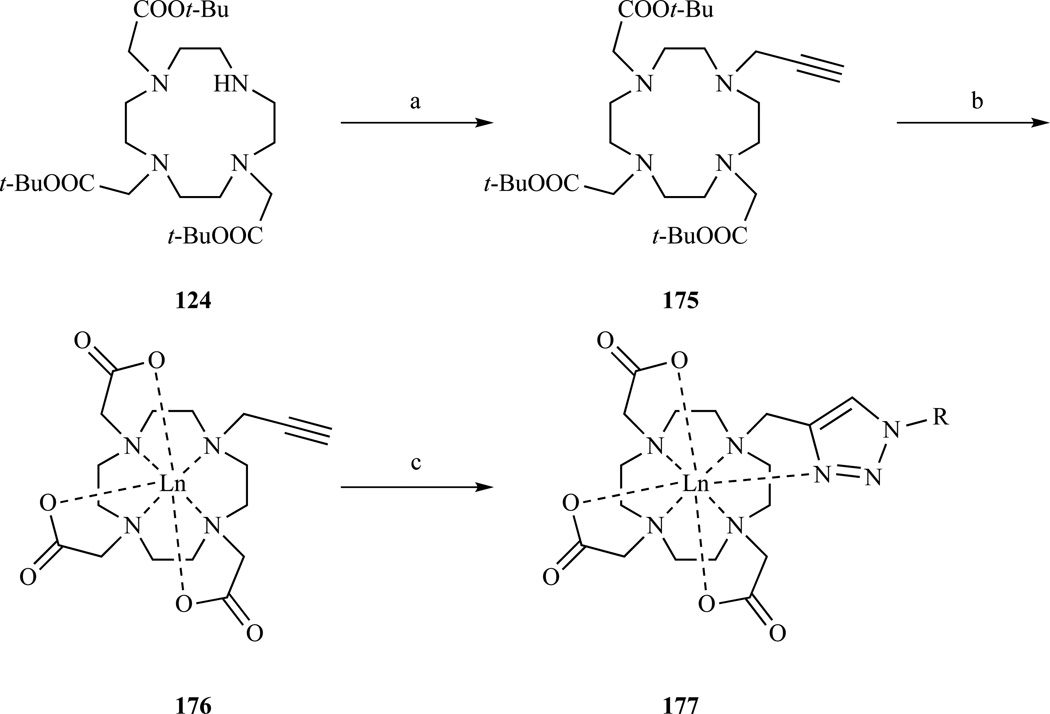

Jauregui et al prepared a heptadentate DO3A derivative 175 (Scheme 25) which was generated by the reaction of the fourth cyclen nitrogen in tris-t-Bu DO3A with propargyl bromide [286]. Copper(I) catalyzed cycloaddition of 176 with azides produced octadentate complex 177 wherein a triazole nitrogen is involved in the coordination to the lanthanide [279].

Scheme 25.

Synthesis of a DO3A derivative where the fourth coordinating arm is a triazole. a) propargyl bromide, CH3CN, 89% yield; b) (i) TFA, DCM, 100% yield, (ii) Ln(OTf)3 (Ln= Eu, 67% yield, Tb, 80% yield); c) Sodium ascorbate, CuSO4, BzN3 (58% yield) or N3CH2(C6H4)CH2N3 (45% yield). Ref. [279]

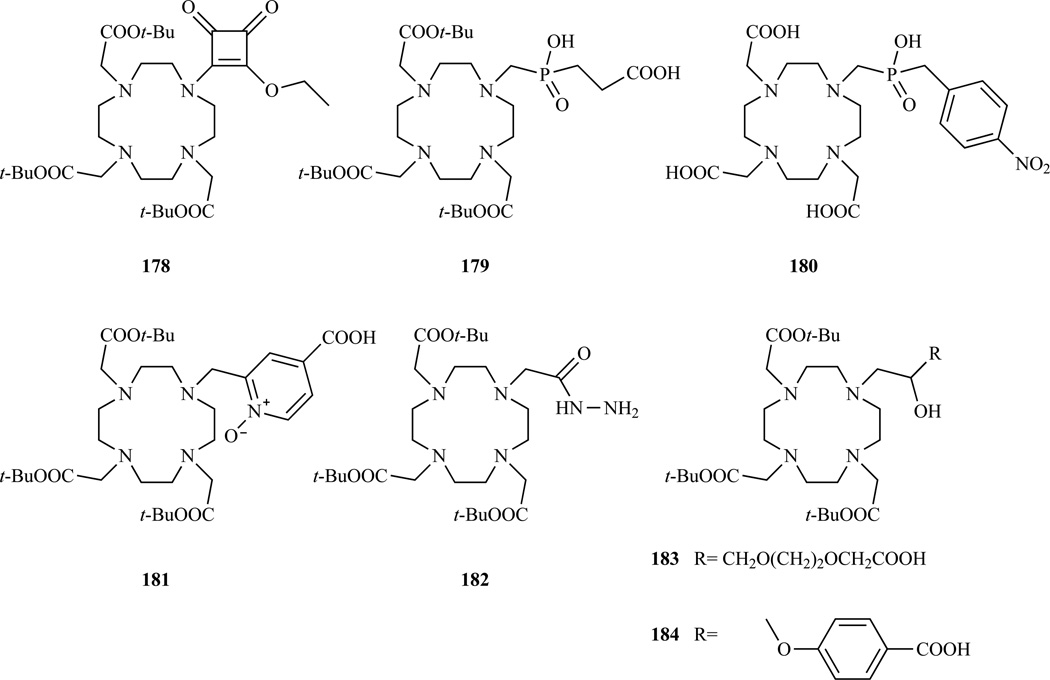

A derivative where one of the DOTA chelating arms was replaced by a squaric acid ester or a squaric acid was prepared by Aime et al. (Chart 14, 178) [119]. The squaric acid ester moiety is reactive towards amines and was used for the multisite labeling of poly-L-lysines and poly-L-ornithines.

Chart 14.

Structures of bifunctional chelators where the fourth coordinating arm is not a carboxylate or a carboxyamide. 178 Ref. [119]; 179 Ref. [282]; 180 Ref. [283]; 181 Ref. [284]; 182 Ref. [286]; 183–184 Ref. [287].

Replacement of one acetic arm with a methylphosphinic acid moiety on the DOTA structure results in Gd(III) complexes that show a fast coordinated water exchange rate, which is close to optimal for low field applications (0.5–1.5 T) [280–281]. The reason for such a fast exchange rate can be found in the steric constraint imposed by the bulky phospinate group on the water coordination site and possibly in the structuring of the second hydration sphere brought about by the phosphinate moiety. To take advantage of this favorable water exchange property, two bifunctional monophosphinate DOTA analogues have been prepared (Chart 14, 179–180) bearing a free carboxyl group [282] or an aromatic amine [283] ready for conjugation.

A different class of ligands, which forms Gd(III) complexes with a remarkably fast water exchange rate, when compared to other monoaquated Gd(III) complexes, is derived from DOTA by substituting one of the acetate arms with a 2-methylpyridine-N-oxide coordinating unit. A derivative with a free carboxyl group available for functionalization (Chart 14, 181) [284] was conjugated to a calix[4]arene. The conjugate exists in solution as a micellar aggregate and displays a high relaxivity [285].

Another example of a bifunctional analogue of DOTA was prepared by substituting an acetate arm with an acylhydrazide moiety which was used to prepare acid labile conjugates with doxorubicin, an anthracycline anticancer drug (Chart 14, 182) [286].

GdHP-DO3A (Chart 1) is a commercially available MR contrast agent, characterized by a high thermodynamic stability and kinetic inertness; however, there is only one report to date that describes bifunctional derivatives of this agent. Barge et al. prepared two bifunctional HP-DO3A derivatives presenting a free carboxyl group for conjugation linked to the coordinating cage through linkers with different hydrophilicity and flexibility (Chart 14, 183–184) [287].

Other bifunctional chelators

A large variety of metal chelators that are not based on DOTA or DTPA have been proposed for applications in MR. For the most part these are not bifunctional, i.e. there is no site for conjugation. Some of these gadolinium complexes possess favorable relaxivity or stability properties comparable or superior to those of GdDTPA or GdDOTA.

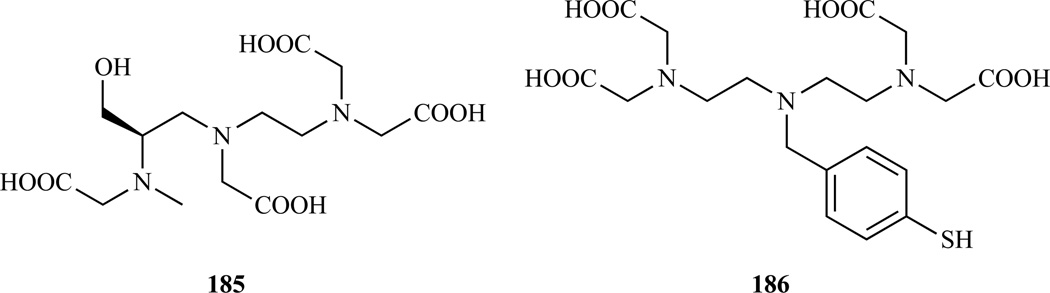

Ligands derived from DTPA, where one of the carboxylates has been replaced by a non-coordinating group (DTTA), have also been studied. The resultant Gd(III) complex has two inner-sphere water molecules usually resulting in higher relaxivity. There is also a drop in complex stability as well but this depends on the DTTA structure. In the synthesis of hydroxymethyl-DTPA (compound 64, Scheme 9) it was noted that over reduction with borane gave an N-methylated side product which could be converted to the N-methylated DTTA derivative shown in Chart 15 (185). This material was converted to a serum albumin-targeted complex by formation of a phosphodiester with 4,4-diphenylcyclohexanol (i.e. the DTTA analog of MS-325). The stability constant with Gd (log Kf = 20.34) was only 1.7 log units lower than that of MS-325. Surprisingly though, the albumin-bound relaxivity of this q=2 complex was only half that of q=1 MS-325. The lower relaxivity was traced to a decrease in the water exchange rate for the q=2 compound [288].

Chart 15.

Structure of two bifunctional DTTA derivatives. 185 Ref. [292]; 186 Ref. [288].

Helm, Toth, and colleagues have prepared DTTA derivatives where the central nitrogen is substituted with a non coordinating group [289–291]. In those Gd(III) complexes, the water exchange rate is about 100 times faster than when the alkyl substituent is on the terminal nitrogen of the triamine backbone and does not limit relaxivity [288–291]. On the other hand, the stability of these complexes is lower (log Kf ranged from 17 – 19). Moriggi et al. recently reported a version of DTTA with a 4-sulfhydrylbenzyl substituent at the central nitrogen (186, Chart 15). This BFC was linked to gold nanoparticles resulting in very high relaxivities in water [292].

One promising class of ligands is based on a pyridine containing macrocycle ring (PCTA, Chart 2) [293]. The Gd(III) complex of PCTA is thermodynamically less stable (log Kf = 20.39 [294]) than GdDOTA (log Kf = 25.3 [221]), and the acid-catalyzed dissociation of LnPCTA complexes is about one order of magnitude faster than for analogous LnDOTA complexes. However, the kinetic inertness of these complexes is still sufficiently high for in vivo applications. GdPCTA has two coordinated water molecules and as a result has a relaxivity that is higher than GdDOTA or GdDTPA.

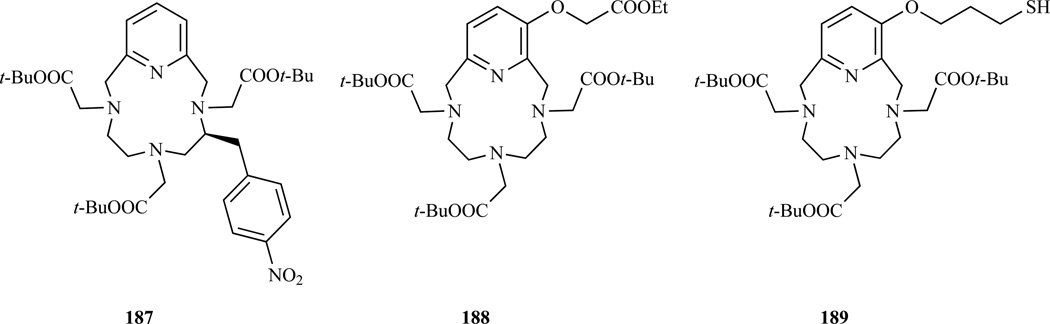

Recently, Kovacs et al. prepared a p-nitrobenzyl derivative of PCTA as a precursor of the amino and isothiocyanate derivatives using a protocol first described by Stetter and Marx, which involves the reaction of a ditosylamide and a dihalide (Chart 16, 187) [295]. Functionalization of PCTA can occur on the pyridine ring starting from 3-hydroxypyridine [32]. Recently, Ferroud et al. prepared a PCTA where the 3-hydroxyl function had been modified to introduce an ethyl carboxyl ester (Chart 16, 188), which was subsequently reacted with dodecylamine to prepare an amphiphilic derivative [296]. The macrocyclization step was carried out between a bis(bromomethyl)pyridine and an already derivatized diethylenetriamine. Lin et al. prepared an analogous derivative carrying a thiol function (Chart 16, 189) [85]. In this case the macrocyclization step was carried out between a bis(hydroxylmethyl)pyridine and a terminally nosylated diethylenetriamine, using a Mitsunobu protocol. A number of bifunctional phosphonic and phosphinic derivatives derivative of PCTA were prepared by Kiefer et al. [297–298].

Chart 16.

Structures of bifunctional chelators derived from PCTA. 187 Ref. [295], 188 Ref. [296], 189 Ref. [85]

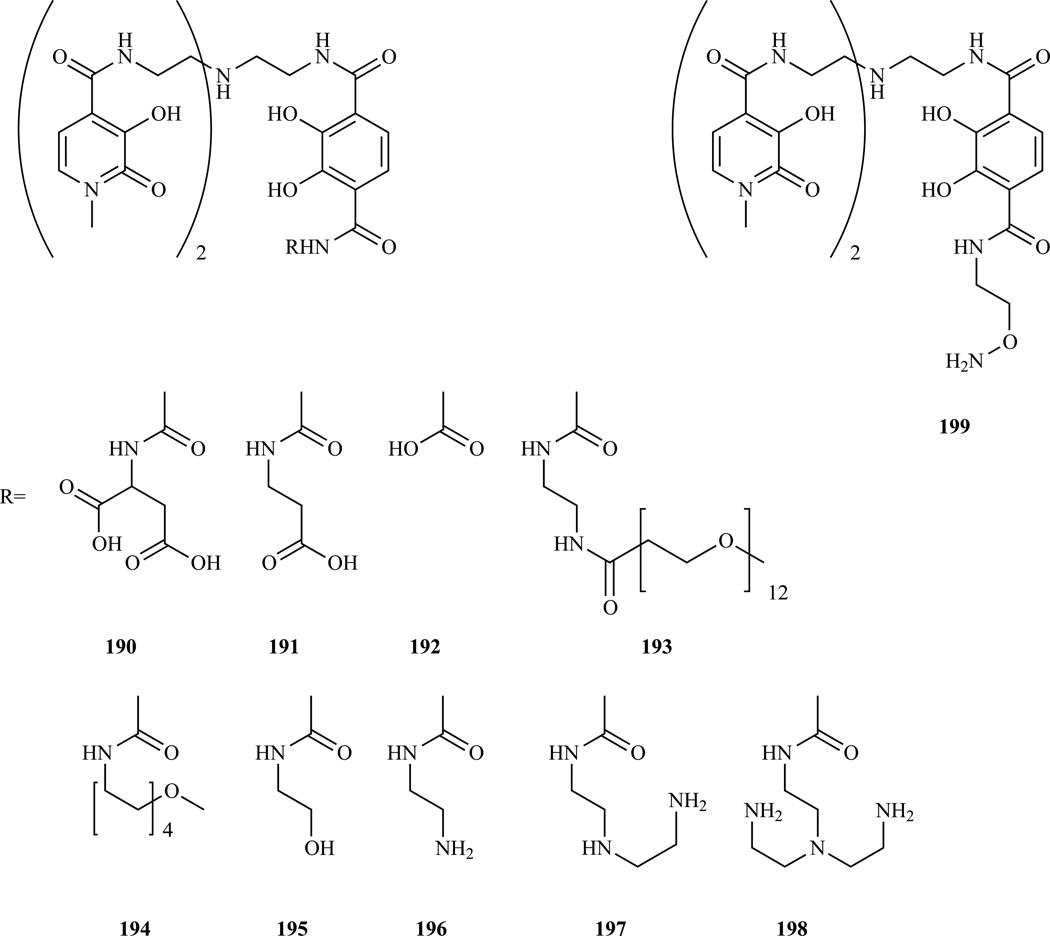

The Raymond group developed a class of hexadentate chelators based on the hydroxypyridonate ligand (Chart 2, 10). This class of agents presents a number of favorable properties including high relaxivity, due to the presence of two coordinated water molecules, but low affinity for endogenous coordinating anions like phosphate or bicarbonate [299]. An early disadvantage was the complex synthetic procedure and the low solubility of early members of the family. In order to improve solubility, a new group of heteropodal ligands which include terephthalamide (TAM) and hydroxypyridinone (HOPO) moieties were prepared [300–301]. The Gd(III) complexes of this class of soluble chelators retain the favorable properties of the tris-HOPO series and the carboxyl group on the terephthalamide offers a site for functionalization. The TAM carboxylate was exploited to bind solubilizing groups (Chart 17) [302] or to introduce a hydroxylamine moiety (Chart 17, 199) [303–304]. The latter was used to anchor the bis(HOPO)-TAM to a viral capsid modified with aldehyde functions, via oxime condensation.

Chart 17.

Structure of bis(HOPO)-TAM functionalized with hydrophilic groups [302] and structure of bis(HOPO)-TAM functionalized with an hydroxyl amino group for conjugation [303–304].

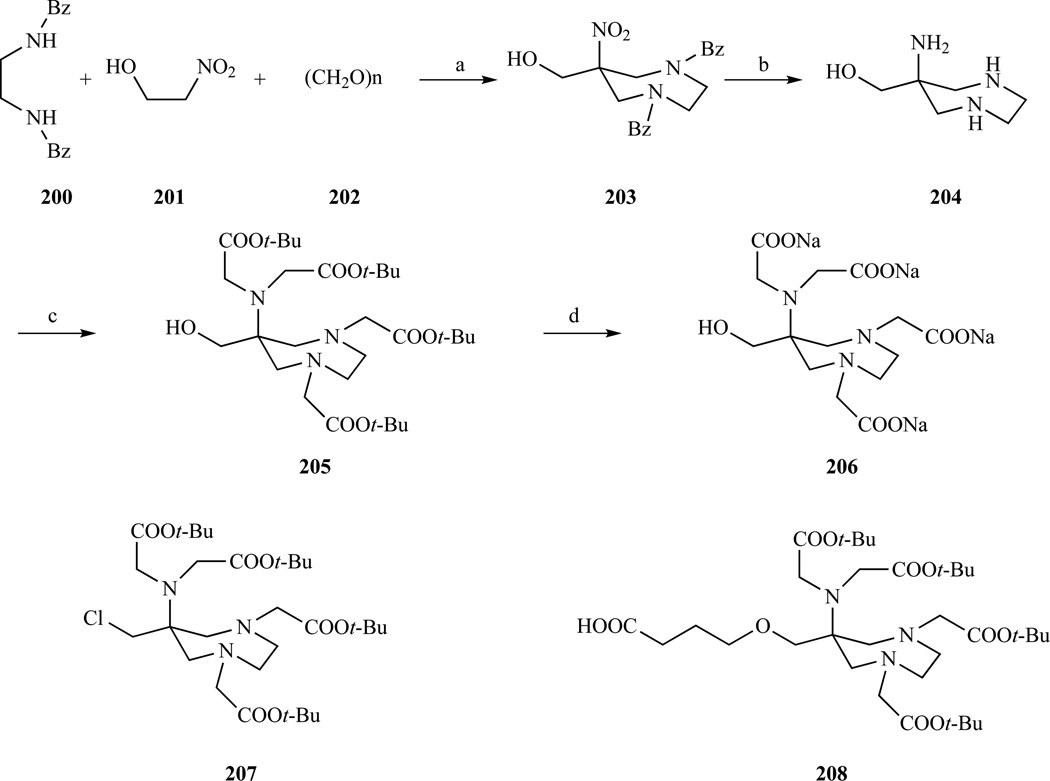

Aime and colleagues recently introduced a new heptadentate chelator [305–306] (AAZTA, Chart 2) that forms Gd(III) complexes characterized by two coordinated water molecules, which results in a higher relaxivity than GdDTPA or GdDOTA (7.1 mM−1s−1 vs 4.3 or 4.2 mM−1s−1 respectively, at 20 MHz, 298 K). The thermodynamic stability of the Gd(III) complex (log Kf = 20.24) is sufficiently high for in vivo applications and its kinetic inertness is superior to GdDTPA [307]. AAZTA is readily prepared in four steps with an overall 50% yield. The easy synthetic access to this ligand, combined with the favorable relaxometric properties prompted the same group to prepare bifunctional versions of AAZTA, with a hydroxyl anchor group (205), by using 2-nitroethanol instead of nitromethane [308]. This compound was later modified to introduce a carboxyl group (208) or to convert the hydroxyl into a chloride (207) in order to obtain different bifunctional chelators.

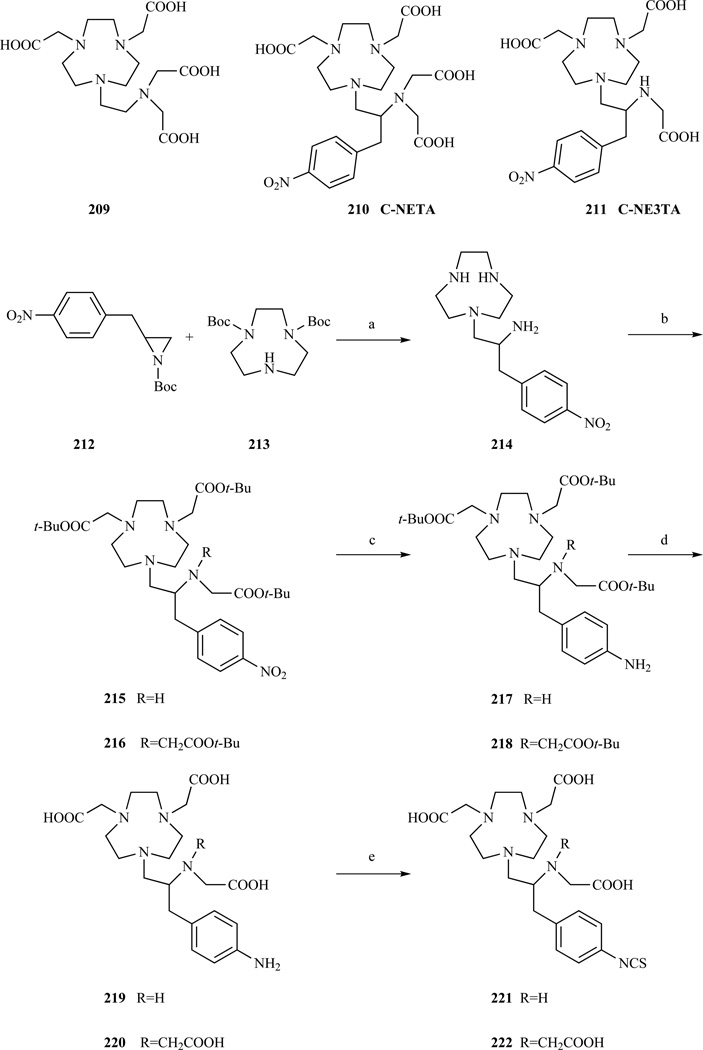

Recently Chong and colleagues introduced a series of new ligands for lanthanides with the goal of fast complexation kinetics combined with acceptable thermodynamic stability [309]. The ligands were designed to integrate the advantages of acyclic ligands such as DTPA, which show fast complexation kinetics, with the advantages of cyclic ligands such as DOTA, which show slow dissociation kinetics.

The octadentate ligand NETA (Scheme 27, 209) combines the macrocycle 1,4,7 triazacyclononane with a flexible acyclic multidentate pendant arm. The relaxivity of GdNETA was higher than that of GdDOTA or GdDTPA (4.83 mM−1s−1, 3.84 mM−1s−1, 4.32 mM−1s−1, respectively, 61 MHz, 37°C). The serum stability of 153GdNETA proved to be extremely good with no measurable transfer of radioactivity from the complex over 14 days [309].

Scheme 27.

Chelator NETA [309] and synthesis of the bifuctional analogues C-NE3TA-NCS (R=H) and C-NETA-NCS (R=CH2COOH). a) DIPEA, CH3CN, 72% yield; b) BrCH2COOt-Bu, KI, DIPEA, DMF, (R=H, T=50 °C, 68% yield, R= CH2COOt-Bu, T= 90 °C, 54% yield); c) H2, Pd/C, EtOH, 92–97% yield; d) HCl, dioxane, 93–97% yield; e) CSCl2, CHCl2/H2O, 85–88% yield [310–311].

A bifunctional version of NETA (Scheme 27, 222), with an isothiocyanate moiety was prepared [310–311]. The introduction of the bifunctional arm was the result of a reaction between the Boc protected aziridine 212 and the bis Boc-protected 1,4,7 triazacyclononane 213. After deprotection, the carboxymethylation with t-Bu bromoacetate was problematic resulting in the formation of 216 in only 54%. Incomplete alkylation of intermediate 214 led to an interesting hexadentate ligand (C-NE3TA, 211). Isothiocyanate derivatives of C-NETA and C-NE3TA were obtained after reduction of 215 or 216 followed by reaction with thiophosgene (221, 222). [Gd(C-NE3TA)] has a higher relaxitvity (5.89 mM−1s−1, 60 MHz, 37°C) than GdNETA as a result of the two coordinated water molecules. This complex also showed excellent serum stability with no loss of radioactivity for [153Gd(C-NE3TA)] over 11 days.

Conclusions

A large number of bifunctional chelators for lanthanide ions have been developed over the last twenty five years. These agents are largely modifications of DOTA and DTPA chelators that are already used in medicine. Such compounds have high formation constants with Gd(III) and a good safety record, and some bifunctional versions are now commercially available. Traditionally, the conjugation chemistry was focused on the formation of amide bonds between activated carboxylic acids and amines or on the formation of thiourea linkages by the reaction of isothiocyanates with amines. More recently, new coupling strategies are being applied such as thioether, oxime formation, or Cu(I) mediated azide-alkyne cycloaddition (click chemistry). Due to their very high kinetic inertness, DOTA analogues are often preferred over linear chelators based on DTPA, especially DTPA-monoamides. However, DTPA derivatives have the benefit of faster metal complexation kinetics, and may be accessed through less complicated synthetic procedures making them useful for proof of concept applications. For clinical development, more inert DOTA-like ligands or improved DTPA derivatives based on cyclohexane diamine may be required. Newer chelators for Gd(III) continue to appear that provide more potent relaxation agents than the DTPA or DOTA derivatives. Ligands with these favorable properties (AAZTA, PCTA, HOPO-TAM, NETA) are often made bifunctional. It is likely that some of these newer chelates will displace the DOTA or DTPA-based BFC from their preferred status.

Scheme 26.

Synthesis of hydroxymethylated AAZTA and structure of two derived bifunctional AAZTA derivatives. a) Toluene/EtOH, 99.5% yield; b) Pd/C, HCOONH4, HCOOH, MeOH, 97.6% yield; c) BrCH2COOt-Bu, K2CO3, CH3CN, 53% yield, d) TFA, DCM; e) NaOH 1M. [308]

Chart 10.

Structure of various bifunctional DOTA monoamides obtained by alkylation of DO3A t-Bu ester. 125–132 Ref. [253], 133 Ref. [254], 134 Ref. [255]

Acknowledgements

PC acknowledges research support from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Biomedical Engineering through grants EB009062-01A1, EB009062-01A1S2 and EB009738-01.

Acronyms used

- DIPEA

N,N-diisopropylethylamine

- DCC

N,N'-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide

- DCM

dichloromethane

- DEPC

diethylcyanophosphonate

- DO3A

1,4,7,10-Tetraaza-cyclododecane-1,4,7-triacetato

- DOTA

1,4,7,10-tetraaza-cyclododecane-1,4,7,10-tetraacetato

- DTPA

diethylenetriamine pentaacetato

- EDC

1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide

- HMPA

hexamethyl phosphoramide

- HOBT

N-Hydroxybenzotriazole

- LDA

lithium diisopropylamide

- TEA

triethylamine

- TFA

trifluoroacetic acid

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

References

- 1.Schwert DD, Davies JA, Richardson N. Non-gadolinium-based MRI contrast agents. Top. Curr. Chem. 2002;221:165–199. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee JH, Koretsky AP. Manganese enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2004;5(6):529–537. doi: 10.2174/1389201043376607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silva AC, Lee JH, Aoki I, Koretsky AP. Manganese-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MEMRI): methodological and practical considerations. NMR Biomed. 2004;17(8):532–543. doi: 10.1002/nbm.945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Meir V, Van der Linden A. Functional cellular imaging with manganese. In: Modo MMJ, Bulte JWM, editors. Molecular and Cellular MR Imaging. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2007. pp. 369–392. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Troughton JS, Greenfield MT, Greenwood JM, Dumas S, Wiethoff AJ, Wang J, Spiller M, McMurry TJ, Caravan P. Synthesis and evaluation of a high relaxivity manganese(II)-based MRI contrast agent. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43(20):6313–6323. doi: 10.1021/ic049559g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behra-Miellet J, Gressier B, Brunet C, Dine T, Luyckx M, Cazin M, Cazin J-C. Free gadolinium and gadodiamide, a gadolinium chelate used in magnetic resonance imaging: evaluation of their in vitro effects on human neutrophil viability. Methods Find. Exp. Clin. Pharmacol. 1996;18(7):437–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Husztik E, Lazar G, Parducz A. Electron microscopic study of Kupffer-cell phagocytosis blockade induced by gadolinium chloride. Br. J. Exp. Pathol. 1980;61(6):624–630. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Itoh N, Kawakita M. Characterization of gadolinium(3+) and terbium(3+) binding sites on calcium-magnesium adenosine triphosphatase of sarcoplasmic reticulum. J. Biochem. 1984;95(3):661–669. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spencer AJ, Wilson SA, Batchelor J, Reid A, Rees J, Harpur E. Gadolinium chloride toxicity in the rat. Toxicol. Pathol. 1997;25(3):245–255. doi: 10.1177/019262339702500301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biagi BA, Enyeart JJ. Gadolinium blocks low- and high-threshold calcium currents in pituitary cells. Am. J. Physiol. 1990;259(3 Pt.1):C515–C520. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.259.3.C515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lansman JB. Blockade of current through single calcium channels by trivalent lanthanide cations. Effect of ionic radius on the rates of ion entry and exit. J. Gen. Physiol. 1990;95(4):679–696. doi: 10.1085/jgp.95.4.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boyd Alan S, Zic John A, Abraham Jerrold L. Gadolinium deposition in nephrogenic fibrosing dermopathy. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2007:27–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.10.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vorobiov M, Basok A, Tovbin D, Shnaider A, Katchko L, Rogachev B. Iron-mobilizing properties of the gadolinium-DTPA complex: clinical and experimental observations. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2003;18(5):884–887. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Agarwal R, Brunelli SM, Williams K, Mitchell MD, Feldman HI, Umscheid CA. Gadolinium-based contrast agents and nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Nephrol. Dial. Transplant. 2009;24(3):856–863. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfn593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Graziani G, Montanelli A, Brambilla S, Balzarini L. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis an unsolved riddle. Journal of nephrology. 2009;22(2):203–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kribben A, Witzke O, Hillen U, Barkhausen J, Daul AE, Erbel R. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009;53(18):1621–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kribben A, Witzke O, Hillen U, Barkhausen J, Daul Anton E, Erbel R. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and therapy. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2009;53(18):1621–1628. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Todd DJ, Kay J. Nephrogenic systemic fibrosis: an epidemic of gadolinium toxicity. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2008;10(3):195–204. doi: 10.1007/s11926-008-0033-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Merbach AE, Toth E, editors. The chemistry of contrast agents in medical magnetic resonance imaging. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 2001. p. 471. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hermann P, Kotek J, Kubicek V, Lukes I. Gadolinium(III) complexes as MRI contrast agents: ligand design and properties of the complexes. Dalton Trans. 2008;(23):3027–3047. doi: 10.1039/b719704g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aime S, Fasano M, Terreno E. Lanthanide(III) chelates for NMR biomedical applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 1998;27(1):19–29. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aime S, Botta M, Fasano M, Geninatti Crich S, Terreno E. 1H and 17O-NMR relaxometric investigations of paramagnetic contrast agents for MRI. Clues for higher relaxivities. Coord. Chem. Rev. 1999;185–186:321–333. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aime S, Botta M, Terreno E. Gd(III)-based contrast agents for MRI. Adv. Inorg. Chem. 2005;57:173–237. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aime S, Crich SG, Gianolio E, Giovenzana GB, Tei L, Terreno E. High sensitivity lanthanide(III) based probes for MR-medical imaging. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2006;250(11+12):1562–1579. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caravan P, Ellison JJ, McMurry TJ, Lauffer RB. Gadolinium(III) chelates as MRI contrast agents: structure, dynamics, and applications. Chem. Rev. 1999;99(9):2293–2352. doi: 10.1021/cr980440x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Frullano L, Rohovec J, Peters JA, Geraldes CFGC. Structures of MRI contrast agents in solution. Top. Curr. Chem. 2002;221:25–60. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lauffer RB. Paramagnetic metal complexes as water proton relaxation agents for NMR imaging: theory and design. Chem. Rev. 1987;87(5):901–927. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bertini I, Luchinat C, Messori L. Nuclear relaxation in NMR of paramagnetic systems. Met. Ions Biol. Syst. 1987;21:47–86. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bertini I, Luchinat C, Parigi G. 1H NMRD profiles of paramagnetic complexes and metalloproteins. Adv. Inorg. Chem. 2005;57:105–172. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peters JA, Huskens J, Raber DJ. Lanthanide induced shifts and relaxation rate enhancements. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 1996;28(3/4):283–350. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Supkowski RM, Horrocks WD., Jr Displacement of inner-sphere water molecules from Eu3+ analogues of Gd3+ MRI contrast agents by carbonate and phosphate anions: dissociation constants from luminescence data in the rapid-exchange limit. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38(24):5616–5619. doi: 10.1021/ic990597n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aime S, Botta M, Frullano L, Crich SG, Giovenzana GB, Pagliarin R, Palmisano G, Sisti M. Contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging: a novel route to enhanced relaxivities based on the interaction of a GdIII chelate with poly-.beta.-cyclodextrins. Chem. Eur. J. 1999;5(4):1253–1260. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Polasek M, Rudovsky J, Hermann P, Lukes I, Vander Elst L, Muller RN. Lanthanide(III) complexes of a pyridine N-oxide analogue of DOTA: exclusive M isomer formation induced by a six-membered chelate ring. Chem. Commun. 2004;(22):2602–2603. doi: 10.1039/b409996f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aime S, Botta M, Crich SG, Giovenzana G, Pagliarin R, Sisti M, Terreno E. NMR relaxometric studies of Gd(III) complexes with heptadentate macrocyclic ligands. Magn. Reson. Chem. 1998;36(Spec. Issue):S200–S208. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aime S, Gianolio E, Corpillo D, Cavallotti C, Palmisano G, Sisti M, Giovenzana GB, Pagliarin R. Designing novel contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. Synthesis and relaxometric characterization of three gadolinium(III) complexes based on functionalized pyridine-containing macrocyclic ligands. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2003;86(3):615–632. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cohen SM, Xu J, Radkov E, Raymond KN, Botta M, Barge A, Aime S. Syntheses and relaxation properties of mixed gadolinium hydroxypyridinonate MRI contrast agents. Inorg. Chem. 2000;39(25):5747–5756. doi: 10.1021/ic000563b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson MK, Botta M, Nicolle G, Helm L, Aime S, Merbach AE, Raymond KN. A highly stable gadolinium complex with a fast, associative mechanism of water exchange. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125(47):14274–14275. doi: 10.1021/ja037441d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hajela S, Botta M, Giraudo S, Xu J, Raymond KN, Aime S. A tris-hydroxymethyl-substituted derivative of Gd-TREN-Me-3,2-HOPO: an MRI relaxation agent with improved efficiency. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122(45):11228–11229. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pierre VC, Botta M, Raymond KN. Dendrimeric gadolinium chelate with fast water exchange and high relaxivity at high magnetic field strength. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127(2):504–505. doi: 10.1021/ja045263y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]