Abstract

Non-technical summary

Retinal ganglion cells represent a population of neurons that relay information from the retina to the brain. During retinal light responses, the spiking activity of retinal ganglion cells is shaped in part by NMDA receptors, which require a coagonist for activation. There is debate over if glycine or d-serine serves as the endogenous coagonist to retinal ganglion cell NMDA receptors. To address this question, we used a mutant mouse lacking functional serine racemase, the d-serine-synthesizing enzyme. In this study we show that d-serine is required to activate retinal ganglion cell NMDA receptors during light stimulation. Mice lacking serine racemase also appeared to have alterations in the relative contribution of NMDA and AMPA receptors to light responses. Interestingly, behavioural tests showed that mice lacking serine racemase had no apparent visual deficits. Collectively, these findings raise interesting questions about the role of d-serine in shaping excitatory synapses and in visual processing.

Abstract

Glycine and/or d-serine are obligatory coagonists of the N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR). Serine racemase, the d-serine-synthesizing enzyme, is expressed by astrocytes and Müller cells of the retina, but little is known about its role in retinal signalling. In this study, we utilize a serine racemase knockout (SRKO) mouse to explore the contribution of d–serine to inner-retinal function. Retinal tissue levels of d-serine in SRKO mice are reduced by 85%. Whole-cell recordings from SRKO retinal ganglion cells showed markedly reduced coagonist occupancy of NMDARs and consequently a dramatic reduction in the NMDAR component of light-evoked responses. NMDAR currents in SRKOs could be rescued by applying exogenous coagonist, but SRKO ganglion cells still displayed lower NMDA/AMPA receptor ratios than wild-type (WT) controls when the coagonist site was saturated. Despite having abnormalities in synaptic glutamatergic transmission, SRKO mice displayed no obvious signs of visual impairment in behavioural testing. These findings raise interesting questions about the role of d-serine in inner-retinal function and development.

Introduction

NMDA receptor activation requires coincident binding of glutamate and a coagonist, either glycine or d-serine (Johnson & Ascher, 1987). It was known for some time that d-serine was capable of exciting neural tissue (Curtis et al. 1961), but given the paucity of d-amino acids in eukaryotes, it was ruled out as an endogenous neurotransmitter. Later, it was discovered that d–serine is present in the brain (Hashimoto et al. 1992), near postsynaptic sites abundant in NMDA receptors (Schell et al. 1995), and that reducing extracellular d-serine by perfusion with exogenously applied d-amino acid oxidase reduced NMDA receptor activity (Panatier et al. 2006).

The discovery of the d-serine-synthesizing enzyme, serine racemase (SR), proved seminal to understanding coagonist regulation in the nervous system (Wolosker et al. 1999b). SR is a vitamin B6-dependent enzyme which catalyses the synthesis of d-serine from l-serine (De Miranda et al. 2002). Cortical regions high in d-serine also show marked SR expression (Wolosker et al. 1999a). Mice lacking functional SR have diminished cortical d-serine, resulting in failed induction of long-term potentiation (Basu et al. 2009). Behaviourally, SR mutants have shown impairments in spatial memory (Basu et al. 2009) and recollection of event order (DeVito et al. 2011).

SR was thought to be predominantly expressed by astrocytes (Wolosker et al. 1999a) possessing high levels of d-serine (Schell et al. 1997). Congruently, inhibiting SR activity in only a few astrocytes locally impairs cortical LTP induction (Henneberger et al. 2010). However, there is evidence that SR is also expressed in neurons (Kartvelishvily et al. 2006). A number of groups have shown that glutamatergic signalling can lead to downstream activation (Kim et al. 2005) or inhibition (Balan et al. 2009) of SR, consequently regulating the levels of extracellular d-serine. These findings gain functional relevance in light of the fact that the NMDAR coagonist site is not saturated at many CNS sites, including the retina (Miller, 2004).

d-serine is present in the inner retina, where it serves as an endogenous coagonist of NMDA receptors (Stevens et al. 2003). Although retinal ganglion cells (RGCs) receive substantial inhibitory input from glycinergic amacrine cells, degradation of d-serine with bath-applied enzyme virtually eliminates retinal ganglion cell NMDAR currents (Gustafson et al. 2007). Also, application of a serine racemase inhibitor has been shown to reduce RGC NMDAR activity in salamander retina (Stevens et al. 2010). SR is predominantly expressed in astrocytes and Müller cells of the adult retina (Stevens et al. 2003) and AMPAR-dependent d-serine release in whole-mount retinas requires glial cell function (Sullivan & Miller, 2010).

Little is known about the involvement of SR in inner retinal function or what consequences diminished d-serine throughout development might have on vision. In the present study, we use a transgenic mouse line with the SR gene deleted (SRKO) (Basu et al. 2009) and show that serine racemase synthesizes most of the retinal d-serine. Whole-cell recordings from SRKO RGCs revealed that NMDARs contribute very little to light-evoked responses, and SRKO RGCs display reduced NMDA/AMPA receptor ratio even after rescuing NMDAR currents with exogenous d-serine. Yet, SRKO mice displayed no apparent signs of visual impairment in behavioural testing.

Methods

Isolation of retinas

Experiments were performed in strict accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Minnesota. Adult C57/BL6 mice were killed by an overdose of Nembutal (0.1 ml of 50 mg ml−1, injected i.p.) followed by pneumo-thorax. Eyes were enucleated and placed in bicarbonate Ringer solution (111 mm NaCl, 3 mm KCl, 2 mm CaCl2, 1 mm MgSO4, 32 mm NaHCO3, 0.5 mm NaH2PO4 and 15 mm dextrose; bubbled with 95% O2, 5% CO2) for the surgical isolation of the retina.

Capillary electrophoresis

We used capillary electrophoresis (CE) to measure d-serine levels in retinal homogenates. Both retinas from an animal were pooled and homogenized in 0.6 m perchloric acid (PCA) using a sonicator probe. KOH (35 μl of 2 m) was added to neutralize the acid. The mixture was spun down in a tabletop centrifuge and the supernatant was removed. The remaining pellet was re-suspended in 2 m NaOH for protein determination using a Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA) bicinchoninic acid assay. Amino acids in the supernatant were fluorescently derivatized at 60°C for 15 min with 0.7 mg ml−1 4-fluro-7-nitrobenz-2oxa-1,3-diazole (NBD-F; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). CE separations were performed at 15 kV (70 μA) on a commercial CE instrument (Beckman-Coulter MDQ, Fullerton, CA) with laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) detection. Separation buffer consisted of 34 mm (2-Hydroxypropyl)-β-cyclodextrin (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) in 165 mm borate pH 10.2. Fluorescent signals were detected by a photomultiplier tube and digitally plotted as fluorescence versus time (electropherogram). Mass of d-serine was determined by comparing samples to known standards. Peak integration was performed using 32 Karat software (Beckman-Coulter).

Whole-cell recordings

Following vitreous removal, isolated retinas were treated with an enzyme solution containing collagenase (120 units ml−1) and hyaluronidase (465 units ml−1). The edges of the retina were maltese-cross cut and flattened over nitrocellulose paper containing a hole in it for imaging. The retina preparation was placed over a glass coverslip of a perfusion chamber and secured using a platinum ring crossed with nylon threading. The chamber was perfused continuously with bicarbonate Ringer solution bubbled with 95% O2, 5% CO2 at a flow rate of ∼2 ml min−1. Patch pipettes (3–8 MΩ) contained (in mm): 128 KCH3SO4, 5 NaCH3SO4, 2 MgCl2, 5 EGTA, 5 Hepes, 1 glutathione, 2 ATP-Mg2+, 0.2 GTP (3Na) and Alexa 594. Ganglion cell bodies were identified using infrared differential interference contrast (IR-DIC) prior to patching and, following recordings, the presence of an axon was confirmed with multi-photon or epifluorescence imaging (800 nm) (Fig. 2A).

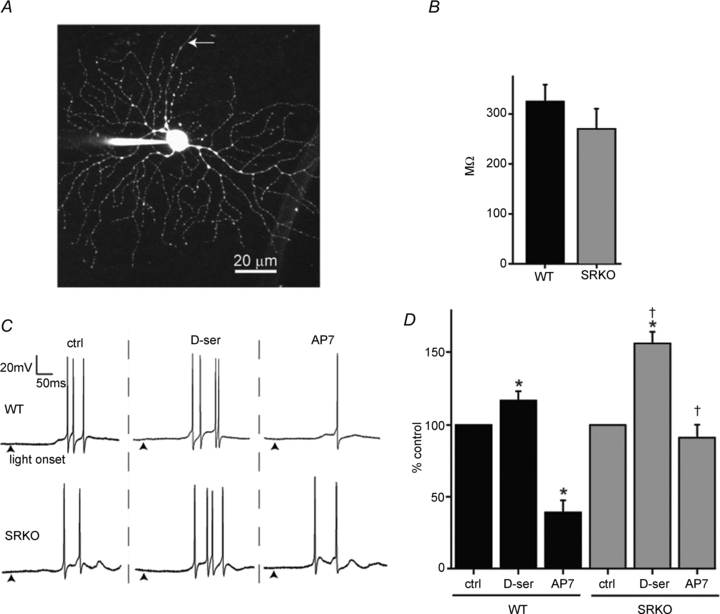

Figure 2. SRKO RGC NMDARs have less coagonist occupancy and contribute less to light-evoked spiking.

A, a flattened multi-photon Z-stack image of a RGC patch-filled with Alexa 594. Following whole-cell recordings, the identity of RGCs was confirmed by the presence of an axon (arrow). B, the input resistance, calculated by a series of hyperpolarizing current injections in the passive range of conductance, was similar between WT (n = 27) and SRKO RGCs (n = 27). C, ON responses, recorded in current clamp (0 pA holding), from WT and SRKO RGCs showing the effects of bath-applied d–ser (100 μm) and AP7 (50 μm) on light-evoked (600 ms, 600 lux) action potentials. Traces shown are from the same cell in each animal. Recordings were made under physiological Mg2+ (1 mm), with TTX and strychnine excluded from the perfusion media. (Arrowheads, light stimulus onset). D, d-serine potentiated ON response spiking in both WT (n = 6) and SRKO (n = 6) RGCs, but this effect was greater in SRKOs. AP7 attenuated RGC spiking in WT but not SRKOs. For a given cell, spikes were averaged over a series of 8 repeated exposures to light. The responses under pharmacological conditions were normalized to those under control conditions (% control). ‘n’ represents the number of cells recorded from. Data were collected from the following number of animals: WT, 5; SRKO, 4. *P < 0.01 compared to control within genotype; †P < 0.01 between genotypes for the same condition.

Current-clamp recordings were made in bicarbonate Ringer solution containing 1 mm Mg2+, while voltage-clamp recordings (−65 mV holding) were made in Mg2+-free Ringer solution which also contained 1 μm TTX and 10 μm strychnine. Data were acquired using an Axoclamp 700A amplifier with a 10 kHz low-pass Bessel filter at a sampling frequency of 10 kHz, digitized with a Digidata 1320, and recorded in pCLAMP 9.0 (all Molecular Devices). All experiments were performed at room temperature.

Voltage-clamp sweeps were averaged (4–8) for a given pharmacological condition and the resulting trace was used to determine peak amplitude and area. NMDA/AMPA ratios were calculated by subtracting the residual current after adding AP7 from the control current (NMDA), divided by the AP7 residual current (AMPA). In current clamp, spike counts were made by averaging the number of spikes generated over eight sweeps for the ON response. These values were normalized to the response evoked in the control condition prior to statistical analysis.

For each sweep retinas were exposed to a single flash of light (∼100 μm diameter spot, 600 lux, 600 ms duration, 10 s inter-stimulus interval) generated using a digital projector controlled by custom software.

Optomotor response

Methods were adopted from Abdeljalil et al. (2005). Briefly, paper drums (30 cm diameter × 40 cm high) were constructed with printed alternating black and white bars. Mice were centred in the drum on a stationary platform while the drum rotated at a constant rate of two rotations per minute. To control for directional bias, the drum was rotated 2 min clockwise, followed by a 30 s period of no rotation, and then 2 min of counter-clockwise rotation. The light intensities were adjusted to the desired intensity using neutral density filters before each experiment. For testing in scotopic conditions, mice were first dark adapted for 10 min and a night vision camera was used. Michelson contrast measurements were made by measuring the luminance (candelas m-2) of the white and black bars with a Minolta CS-100 meter. For all data, two independent observers, blind to the genotype of the mouse, analysed each video by counting the number of head tracks (defined as head motions matching the angular velocity of the drum) over the testing period. The number of tracks counted per trial by each observer was averaged. Each mouse was run twice in each condition, and their average tracking was pooled for statistical analysis. The time spent grooming was subtracted in analysis.

Statistics

All comparisons between groups were made using a Student's one-tailed t test. Z-tests were used when the null hypothesis stated no change from a fixed value. For all whole-cell recording data, statistics were performed with ‘n’ representing the number of cells from which recordings were obtained. All data are expressed as mean ± standard error, and significance defined as P < 0.05.

Results

SRKO retinas have reduced d-serine

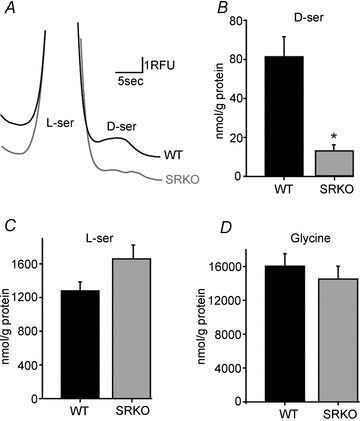

To measure the levels of retinal d-serine, we homogenized isolated retinas and used capillary electrophoresis to quantify the amino acid content, which was then normalized to total retinal protein. SRKO retinas displayed an 85% reduction in d-serine compared to WT (P < 0.01) (Fig. 1B), whereas no difference in l-serine was detected (P = 0.09) (Fig. 1C). The total glycine content of retinas also showed no difference between WT and SRKO mice (P = 0.50) (Fig. 1D).

Figure 1. SRKO mice have reduced retinal d-serine.

Capillary electrophoresis quantification of amino acid content in retinal homogenates normalized to protein content. A, electropherogram showing the separation of l-serine from d-serine in WT and SRKO retinal homogenates. B, total retinal d-serine. SRKOs (n = 5) have significantly less d-serine than WT (n = 5). C, no significant difference in l-serine was detected between WT (n = 5) and SRKO retinas (n = 5). D, retinal glycine levels were similar between WT (n = 5) and SRKOs (n = 5). *P < 0.01.

NMDARs contribute less to light-evoked impulses in SRKO RGCs

To determine the effects of diminished d-serine levels on retinal ganglion cell activity, we measured light-evoked synaptic currents and impulse activity using whole-cell recordings. Patch pipettes were loaded with fluorescent dye (Alexa 594) and RGCs were morphologically identified using fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2A). When injected with a series of hyperpolarizing currents, SRKO RGCs displayed no significant difference in input resistance compared to WT, suggesting there was no difference in the size or passive properties of the RGCs used in studying the genotypes (Fig. 2B). We next tested whether NMDAR contribution to RGC light-evoked action potentials was altered in SRKO retinas. Current-clamp recordings were made in a physiological concentration of Mg2+ (1 mm), without TTX or inhibitory antagonists added, and the number of light-evoked spikes for ON responses was averaged over repeated stimuli. The addition of the NMDAR antagonist AP7 significantly reduced light-evoked spiking in WT (39.1 ± 8.5% of control spiking, P < 0.0001) but not in SRKOs (91.2 ± 9.1% control, P = 0.19), with only 2 out of 6 showing a reduction greater than 5% (Fig. 2C and D). The effects of AP7 were markedly greater in WT than SRKO cells (P < 0.01). Although d-serine increased RGC light-evoked activity significantly in both SRKO and WT (WT = 117.1 ± 6.6%, P < 0.01; SRKO = 156.9 ± 8.0%, P < 0.01; Fig. 2C and D), this effect was greater in SRKOs than in WT RGCs (P < 0.01; Fig. 2D).

SRKO RGCs lack light-evoked NMDAR currents and have lower NMDA/AMPA receptor ratios

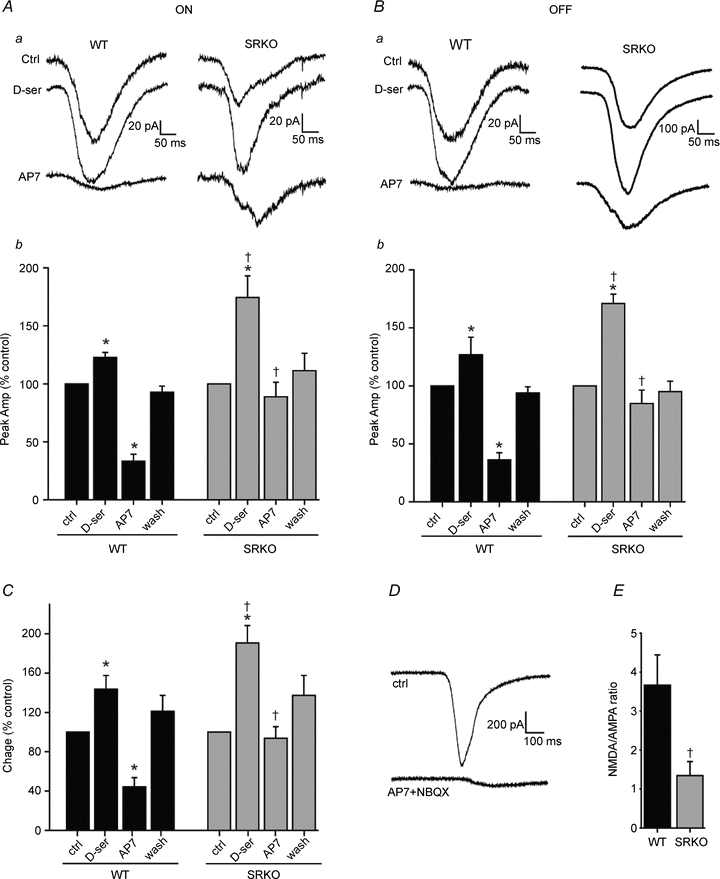

To confirm that NMDAR currents underlie the spiking differences observed in SRKOs, voltage-clamp recordings of RGCs were performed at the calculated chloride reversal potential (−65 mV). No Mg2+ was added to the superfusate to maximize NMDAR current. In addition, TTX was added to prevent cell spiking and strychnine was added to minimize inhibitory currents. Under these conditions, AP7 significantly reduced the peak current amplitude of light-evoked ON responses in WT RGCs (33.3 ± 5.9% control, P < 0.001; Fig. 3A). SRKO ON responses were much less sensitive to NMDAR antagonist (88.8 ± 12.5% control, P = 0.20) compared to WT (P < 0.001). Bath-applied d-serine significantly potentiated ON responses in both WT and SRKOs (WT = 122.6 ± 4.4% control, P < 0.01; SRKO = 174.4 ± 18.6% control, P < 0.01) but to a greater extent in SRKOs (P < 0.01, compared to WT increase; Fig. 3A). A similar result was observed for OFF responses (Fig. 3B), where AP7 attenuated WT but not SRKO inward currents (WT = 36.3 ± 6.1% control, P < 0.001; SRKO = 84.7 ± 11.6% control, P = 0.12; P < 0.01 between genotypes), while the potentiation by d-serine was significantly greater in SRKOs (WT = 126.7 ± 15.2% control, P < 0.05; SRKO = 171.0 ± 8.0% control, P < 0.001; P < 0.05 between genotypes). The pooled ON and OFF light-evoked charge transfer (Fig. 3C) was comparable to the peak amplitude results (d-serine: WT = 143.6 ± 14.0%, P < 0.001; SRKO = 190.6 ± 17.7%, P < 0.001; P < 0.05 between genotypes) (AP7: WT = 44.3 ± 9.4%, P < 0.001; SRKO = 93.7 ± 17.7%, P = 0.3, P < 0.001 between genotypes). Collectively, these findings suggest that SRKOs have less NMDAR activity, at least in part because they are deficient in coagonist.

Figure 3. SRKO RGCs have less light-evoked NMDAR currents and lower NMDA/AMPA receptor ratios.

Whole-cell voltage clamp recordings from retinal ganglion cells held at the chloride reversal potential (−65 mV), in 1 μm TTX, 10 μm strychnine and 0 Mg2+. Aa, light-evoked inward currents from the ON responses of WT and SRKO mice and the effects of bath-applied d–ser and AP7. Ab, the peak inward current (averaged over 8 sweeps) for ON responses in control, d-serine, AP7, and following drug washout. ON response inward currents were increased by d–ser in both WT (n = 9) and SRKO mice (n = 9), but to a significantly greater extent in SRKOs. Blocking NMDARs with AP7 reduced currents more in WT than in SRKO RGCs. Ba, OFF response inward currents compared between WT and SRKOs. Bb, potentiation by d-serine of peak inward currents in OFF responses was significantly greater in SRKOs (n = 6) than in WT (n = 5). AP7 reduced inward currents in WT but not SRKO RGCs. C, the ON and OFF pooled light-evoked charge was similar to peak amplitude. D, raw trace showing that a combination of AMPAR antagonist (10 μm NBQX) and AP7 blocks nearly all light-evoked inward currents. E, the light-evoked NMDA/AMPA current ratio (see Methods) was significantly lower in SRKOs (n = 15) than in WT (n = 14); data from ON and OFF responses pooled. All data are normalized to control responses within a given cell (% control). ‘n’ represents the number of cells recorded from. Data were collected from the following number of animals: WT ON = 5, WT OFF = 4; SRKO ON = 8, SRKO OFF = 5.*P < 0.05 compared to control within genotype; †P < 0.01 between genotypes for the same condition.

Blocking AMPARs and NMDARs with NBQX and AP7, respectively, nearly abolished all inward currents (Fig. 3D). As RGC excitatory inputs are predominantly AMPA and NMDAR mediated, we were able to derive NMDA/AMPA response ratios (see Methods). SRKO retinas had a significantly lower NMDA/AMPA ratio in the presence of saturating coagonist (WT = 3.7 ± 0.8; SRKO = 1.3 ± 0.3; P < 0.05) (Fig. 3E), implying that a reduction in d-serine availability might alter the expression of synaptic glutamate receptors.

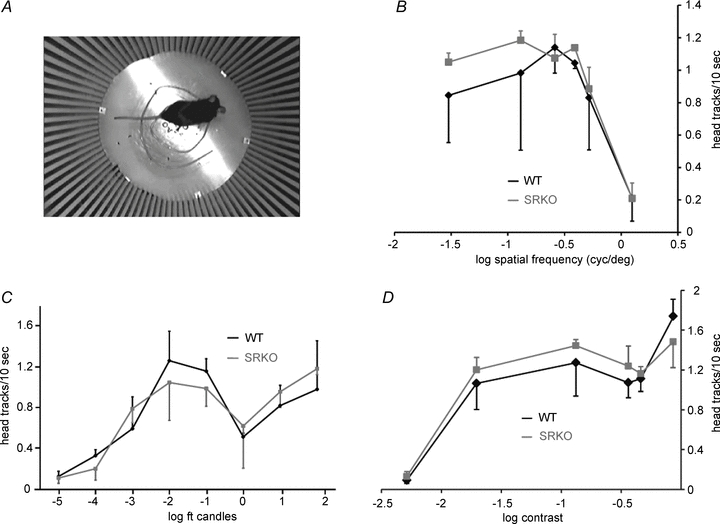

SRKO mice have normal low-level vision

The optokinetic reflex (OKR) stabilizes moving images on the retina by moving the eyes relative to the head or the head relative to the body. The OKR has been used as a reliable behavioural test of low-level visual function (Cahill & Nathans, 2008). We utilized OKR head movements to probe for potential differences in visual function in the SRKO mice. A drum patterned with alternating white and black bars was rotated around a fixed platform where the mouse was stationed. The number of head tracking movements elicited over a given time interval was used to gauge visual function (Fig. 4A). Visual acuity in WT and SRKO mice was compared by varying the spatial frequency of the grating on the rotating drum and measuring the OKR under photopic lighting conditions (40 foot candles). SRKO and WT mice displayed head tracking which began to decrease around 0.39 cycles deg-1. There appeared to be no difference in visual acuity between WT and SRKO mice within the range of stimuli tested (Fig. 4B). Using the optimal spatial grating measured from the visual acuity experiments (0.13 cycles deg-1), we tested to see if there was any difference in visual sensitivity under varying light intensities. SRKO mice appeared to have normal OKRs with brightness values ranging from photopic to scotopic vision (Fig. 4C). Additionally, we tested contrast sensitivity under a fixed photopic lighting condition (40 foot candles), by altering the shading of the white and black bars over a 100-fold range of Michelson contrast values, but no apparent differences were detected between the genotypes. (Fig. 4D).

Figure 4. SRKO mice have normal vision.

A, overhead view of a mouse in the optokinetic reflex (OKR) testing chamber. Mice stood on a stationary elevated platform while a pattern of alternating white and black stripes rotated around them and the OKR was measured as the number of tracking head turns over a given time interval. B, under photopic lighting (40 foot candles), the number of black–white alterations per degree of visual field (cycles deg−1) was altered to measure visual acuity. The OKR elicited was similar between WT and SRKO mice over a wide range of spatial frequencies. C, using a 0.13 cycles deg−1 visual stimulus, varying overhead light intensities (foot candles) produced a similar OKR in WT and SRKOs. D, the OKR in SRKOs was similar to controls when tested over a range of Michelson contrast values for a 0.13 cycles deg−1 pattern with 40 foot candles of overhead light. Each data point represents the average of 5 mice (n = 5).

Discussion

These studies demonstrate that serine racemase is essential for providing d-serine for proper retinal ganglion cell NMDAR activity. SRKO mice displayed a marked reduction in retinal d-serine levels, while no difference in glycine was detected. SRKOs also lacked NMDAR drive in light-evoked currents and impulse activity, indicating that d-serine, not glycine, is the predominant endogenous coagonist of RGC NMDARs. A substantial portion of the NMDA receptor response could be rescued in the SRKO mice by adding exogenous coagonist, but a difference remained in the NMDA/AMPA receptor ratios in the SRKO mice. Surprisingly, SRKO mice had no apparent deficit in basic visual function when tested behaviourally.

SRKO mice displayed an 85% reduction in retinal tissue d-serine compared to WT controls, similar to the 90% reduction in d-serine found in cortex (Basu et al. 2009). However, the total level of d-serine that we measured in the WT retina was substantially lower than that found in the cortex. This, in part, might be a consequence of elevated expression of the d-serine-degrading enzyme d–amino acid oxidase (DAO) in retina compared to cortex. Mutant mice lacking functional DAO have increased retinal d-serine (Sullivan & Miller, 2010), while having an even greater increase of d-serine in cerebellum but very little change in the cortex (Hamase et al. 2005). However, DAO cannot solely account for this difference because d-serine levels in the retinas of DAO mutant mice are still much lower than in cortex. Perhaps serine racemase expression levels are lower in the retina than in cortex but the d-serine it synthesizes is precisely distributed at RGC synapses or less stringently regulated by transporters (O'Brien et al. 2005).

Both ON and OFF light-evoked currents were less sensitive to NMDAR antagonist in SRKO RGCs, suggesting NMDARs contribute less to SRKO RGC currents. This apparent difference could not have been due to a lack of synaptic NMDARs in the SRKOs, because an NMDAR component could be rescued in these animals by adding d-serine. Although WT RGC NMDAR currents were still significantly increased by coagonist, the magnitude of potentiation in SRKOs was greater. A major contributor to the smaller SRKO NMDAR currents must therefore be reduced occupancy of coagonist sites.

Glycine, another NMDAR coagonist, is found in high concentrations in the retina where it serves as an inhibitory neurotransmitter. Measurements of extracellular amino acids in the retina have shown that glycine levels are much higher than those of d-serine (Sullivan & Miller, 2010), yet the findings here demonstrate that d-serine is the major coagonist of synaptic RGC NMDARs. Previously, we demonstrated that mice heterozygous for a null mutation of the glycine transporter GlyT1 have saturated RGC NMDARs (Reed et al. 2009). Thus, GlyT1 appears to be responsible for maintaining low concentrations of glycine in the synaptic cleft in the retina and permitting d-serine to serve as the predominant coagonist.

The light-evoked synaptic responses of SRKO RGCs displayed reduced NMDA/AMPA receptor ratios, raising the possibility that d-serine is involved in determining the balance of ionotropic glutamate receptors at excitatory synapses during development. At the initial phase of synapse formation in hippocampus, neurons only express NMDARs, which must be activated for AMPARs to be delivered to synapses (Durand et al. 1996), and adult SRKO mice have shown elevated expression of NMDAR subunits in the postsynaptic density of hippocampal neurons (Balu & Coyle, 2011). In the retina, d-serine is present in Müller cells prior to the expression of synaptic proteins (Diaz et al. 2007) where it might serve a role in synaptogenesis. If d-serine is important in driving AMPAR insertion in retinal synapses, then one might expect to find an increase in the NMDA/AMPA ratio, the opposite of what we observed. However, the retina differs from cortex in that neurons initially possess AMPARs during early development and expresses NMDARs later on (Somohano et al. 1988). Perhaps d-serine is required to activate newly inserted NMDARs, which in turn regulate the number of AMPARs at retinal synapses.

SRKO mice had a significantly reduced NMDAR component in light-evoked RGC impulse activity, yet behavioural tests of visual function demonstrated that SRKOs had normal photopic visual acuity, scotopic sensitivity and contrast detection. SRKO mice may undergo some form of developmental compensation to adequately relay visual input, such as increased expression of AMPARs, which would also account for the lower NMDA/AMPA ratios observed in these studies. Exactly how AMPARs may compensate for a loss of NMDAR activity is unclear, as these receptors display substantially different single-channel properties. An alternative explanation is that RGC NMDARs and their inter-relation with d-serine might serve a more specialized role in retinal processing, features that were not tested in this study.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Eric Gustafson for discussions and advice.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- AP7

d-2-amino-7-phosphonoheptanoic acid

- OKR

optokinetic response

- RGC

retinal ganglion cell

- SRKO

serine racemase knockout

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

- WT

wild-type

Author contributions

S.J.S. performed all electrophysiology experiments. S.J.S. and G.E.R. performed and analysed CE experiments. S.J.S. and R.J.W. performed behavioural experiments. Experiments designed by S.J.S., R.J.W., M.E., G.E.R. and R.F.M. Manuscript was written by S.J.S. with the assistance of M.E., J.T.C., G.E.R. and R.F.M. Mutant mice provided by J.T.C. All authors approved the final version.

References

- Abdeljalil J, Hamid M, Abdel-Mouttalib O, Stephane R, Raymond R, Johan A, et al. The optomotor response: a robust first-line visual screening method for mice. Vision Res. 2005;45:1439–1446. doi: 10.1016/j.visres.2004.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balan L, Foltyn VN, Zehl M, Dumin E, Dikopoltsev E, Knoh D, et al. Feedback inactivation of D-serine synthesis by NMDA receptor-elicited translocation of serine racemase to the membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7589–7594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809442106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balu DT, Coyle JT. Glutamate receptor composition of the post-synaptic density is altered in genetic mouse models of NMDA receptor hypo- and hyperfunction. Brain Res. 2011;1392:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.03.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basu AC, Tsai GE, Ma CL, Ehmsen JT, Mustafa AK, Han L, et al. Targeted disruption of serine racemase affects glutamatergic neurotransmission and behavior. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:719–727. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cahill H, Nathans J. The optokinetic reflex as a tool for quantitative analyses of nervous system function in mice: application to genetic and drug-induced variation. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2055. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis DR, Phillis JW, Watkins JC. Actions of aminoacids on the isolated hemisected spinal cord of the toad. Br J Pharmacol Chemother. 1961;16:262–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1961.tb01086.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Miranda J, Panizzutti R, Foltyn VN, Wolosker H. Cofactors of serine racemase that physiologically stimulate the synthesis of the N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor coagonist D-serine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:14542–14547. doi: 10.1073/pnas.222421299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeVito LM, Balu DT, Kanter BR, Lykken C, Basu AC, Coyle JT, Eichenbaum H. Serine racemase deletion disrupts memory for order and alters cortical dendritic morphology. Genes Brain Behav. 2011;10:210–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-183X.2010.00656.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz CM, Macnab LT, Williams SM, Sullivan RK, Pow DV. EAAT1 and D-serine expression are early features of human retinal development. Exp Eye Res. 2007;84:876–885. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2007.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand GM, Kovalchuk Y, Konnerth A. Long-term potentiation and functional synapse induction in developing hippocampus. Nature. 1996;381:71–75. doi: 10.1038/381071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson EC, Stevens ER, Wolosker H, Miller RF. Endogenous D-serine contributes to NMDA-receptor-mediated light-evoked responses in the vertebrate retina. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:122–130. doi: 10.1152/jn.00057.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamase K, Konno R, Morikawa A, Zaitsu K. Sensitive determination of D-amino acids in mammals and the effect of D-amino-acid oxidase activity on their amounts. Biol Pharm Bull. 2005;28:1578–1584. doi: 10.1248/bpb.28.1578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto A, Nishikawa T, Hayashi T, Fujii N, Harada K, Oka T, Takahashi K. The presence of free D-serine in rat brain. FEBS Lett. 1992;296:33–36. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(92)80397-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henneberger C, Papouin T, Oliet SH, Rusakov DA. Long-term potentiation depends on release of D-serine from astrocytes. Nature. 2010;463:232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature08673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JW, Ascher P. Glycine potentiates the NMDA response in cultured mouse brain neurons. Nature. 1987;325:529–531. doi: 10.1038/325529a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kartvelishvily E, Shleper M, Balan L, Dumin E, Wolosker H. Neuron-derived D-serine release provides a novel means to activate N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:14151–14162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512927200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim PM, Aizawa H, Kim PS, Huang AS, Wickramasinghe SR, Kashani AH, et al. Serine racemase: activation by glutamate neurotransmission via glutamate receptor interacting protein and mediation of neuronal migration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2105–2110. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409723102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RF. D-Serine as a glial modulator of nerve cells. Glia. 2004;43:275–283. doi: 10.1002/glia.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien KB, Miller RF, Bowser MT. D-Serine uptake by isolated retinas is consistent with ASCT-mediated transport. Neurosci Lett. 2005;385:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panatier A, Theodosis DT, Mothet JP, Touquet B, Pollegioni L, Poulain DA, Oliet SH. Glia-derived D-serine controls NMDA receptor activity and synaptic memory. Cell. 2006;125:775–784. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed BT, Sullivan SJ, Tsai G, Coyle JT, Esguerra M, Miller RF. The glycine transporter GlyT1 controls N-methyl-D-aspartic acid receptor coagonist occupancy in the mouse retina. Eur J Neurosci. 2009;30:2308–2317. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.07020.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell MJ, Brady RO, Jr, Molliver ME, Snyder SH. D-serine as a neuromodulator: regional and developmental localizations in rat brain glia resemble NMDA receptors. J Neurosci. 1997;17:1604–1615. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-05-01604.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schell MJ, Molliver ME, Snyder SH. D-serine, an endogenous synaptic modulator: localization to astrocytes and glutamate-stimulated release. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3948–3952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somohano F, Roberts PJ, Lopez-Colome AM. Maturational changes in retinal excitatory amino acid receptors. Brain Res. 1988;470:59–67. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(88)90201-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens ER, Esguerra M, Kim PM, Newman EA, Snyder SH, Zahs KR, Miller RF. D-serine and serine racemase are present in the vertebrate retina and contribute to the physiological activation of NMDA receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:6789–6794. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1237052100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens ER, Gustafson EC, Sullivan SJ, Esguerra M, Miller RF. Light-evoked NMDA receptor-mediated currents are reduced by blocking D-serine synthesis in the salamander retina. Neuroreport. 2010;21:239–244. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e32833313b7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan SJ, Miller RF. AMPA receptor mediated D-serine release from retinal glial cells. J Neurochem. 2010;115:1681–1689. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.07077.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolosker H, Blackshaw S, Snyder SH. Serine racemase: a glial enzyme synthesizing D-serine to regulate glutamate-N-methyl-D-aspartate neurotransmission. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999a;96:13409–13414. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolosker H, Sheth KN, Takahashi M, Mothet JP, Brady RO, Jr, Ferris CD, Snyder SH. Purification of serine racemase: biosynthesis of the neuromodulator D-serine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999b;96:721–725. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.2.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]