Abstract

Non-technical summary

Muscle function depends on tightly regulated Ca2+ movement between the intracellular sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ store and cytoplasm in muscle cells. Disturbances in these processes have been linked to impaired muscle function and muscle disease. We disrupted the gene for the SERCA2 SR Ca2+ pump in mouse skeletal muscle to study how decreased transport of Ca2+ into the SR would affect soleus muscle function. We found that the SERCA2 content was strongly reduced in the 40% fraction of soleus muscle fibres normally expressing SERCA2. Muscle relaxation was slowed, supporting the hypothesis that reduced SERCA2 would reduce Ca2+ transport into the SR and prolong muscle relaxation time. Surprisingly, the muscles maintained maximal force, despite the fact that less SERCA2 in these fibres would be expected to lower the amount of Ca2+ released during contraction, and thereby lower the maximal force. Our findings raise important questions regarding the roles of SERCA2 and SR in muscle function.

Abstract

Sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPases (SERCAs) play a major role in muscle contractility by pumping Ca2+ from the cytosol into the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ store, allowing muscle relaxation and refilling of the SR with releasable Ca2+. Decreased SERCA function has been shown to result in impaired muscle function and disease in human and animal models. In this study, we present a new mouse model with targeted disruption of the Serca2 gene in skeletal muscle (skKO) to investigate the functional consequences of reduced SERCA2 expression in skeletal muscle. SkKO mice were viable and basic muscle structure was intact. SERCA2 abundance was reduced in multiple muscles, and by as much as 95% in soleus muscle, having the highest content of slow-twitch fibres (40%). The Ca2+ uptake rate was significantly reduced in SR vesicles in total homogenates. We did not find any compensatory increase in SERCA1 or SERCA3 abundance, or altered expression of several other Ca2+-handling proteins. Ultrastructural analysis revealed generally well-preserved muscle morphology, but a reduced volume of the longitudinal SR. In contracting soleus muscle in vitro preparations, skKO muscles were able to fully relax, but with a significantly slowed relaxation time compared to controls. Surprisingly, the maximal force and contraction rate were preserved, suggesting that skKO slow-twitch fibres may be able to contribute to the total muscle force despite loss of SERCA2 protein. Thus it is possible that SERCA-independent mechanisms can contribute to muscle contractile function.

Introduction

Sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ ATPases (SERCAs) are calcium pumps that play a major role in muscle contractility (Stephenson et al. 1998). SERCA ATPases sequester free Ca2+ from the cytosol back into the SR store, thus reducing the cytosolic free Ca2+ sufficiently to allow muscle relaxation and at the same time refilling the SR Ca2+ store. The SERCA gene family codes for three proteins, of which SERCA1 and SERCA2 are the major isoforms in skeletal muscle. SERCA1 is expressed in fast-twitch fibres, and SERCA2 is expressed in slow-twitch fibres (Wuytack et al. 1992, 1995; East, 2000). Both isoforms have similar transport capacities and binding affinities for calcium and ATP (Lytton et al. 1992). Nonetheless, Ca2+ ATPase activity is sixfold higher in rat fast-twitch than in slow-twitch muscles (Everts et al. 1989). This may be attributed to the 2- to 5-fold higher SERCA1 protein and mRNA abundance in fast-twitch muscle relative to the SERCA2 abundance in slow-twitch muscles (Wu & Lytton, 1993).

In humans, decreased SERCA function may result in impaired muscle function or disease. Mutations in the Serca1 gene result in exercise-induced muscle stiffness, pain and reduced relaxation (Brody's disease) (Brody, 1969; Karpati et al. 1986; Benders et al. 1994). Despite the loss of SERCA1 activity in these patients, skeletal muscles are able to relax, albeit at a reduced rate (Odermatt et al. 1996), and the cytosolic Ca2+ content is close to normal levels (Karpati et al. 1986). Mutations in the Serca2 gene lead to Darier's disease, a disorder characterized by a loss of adhesion between epidermal cells and abnormal keratinization (Sakuntabhai et al. 1999). Reduced SERCA2 expression and/or function have been found in some types of human heart failure as well as in experimental animal heart failure models. The reduced SERCA2 expression or function in heart failure has been suggested to underlie the impaired contractile function in cardiomyocytes (Arai et al. 1994).

Altered SERCA activity has been linked to skeletal muscle fatigue. Depressed SERCA activity was found after exercise to exhaustion by treadmill running and in muscle fatigue induced by electrical stimulation (Byrd et al. 1989; Ward et al. 1998; Yasuda et al. 1999; Inashima et al. 2003). In mouse single fibres, the SERCA pump rate and the Ca2+ removal rate from the cytosol were both reduced during fatigue (Westerblad & Allen, 1993, 1994a). Pharmacological inhibition of SERCA function with TBQ (2,5-di(tert-butyl)-1,4-benzohydroquinone) in single mouse fibres increased the cytosolic [Ca2+] and slowed muscle relaxation (Westerblad & Allen, 1994b). Altered SERCA activity has been found in skeletal muscles in animal models with heart failure (Peters et al. 1997; Simonini et al. 1999; Lunde et al. 2006), suggesting that there might be a relationship between SERCA function and the skeletal muscle fatigue and muscle weakness experienced by heart failure patients.

Several gene-targeted mouse models have been developed to study the physiological consequences of loss of SERCA function in vivo. Homozygous Serca1−/− mice showed slow limb movements, and contracture similar to the symptoms observed in Brody patients. However, Serca1−/− mice die shortly after birth from respiratory failure due to contractile dysfunction in the diaphragm where SERCA1 is dominantly expressed (Pan et al. 2003). Homozygous Serca2−/− mice die during early embryonic development, whereas cardiac function was only moderately reduced in heterozygous Serca2+/− mice (Periasamy et al. 1999). Using a new cardiac-specific inducible SERCA2KO mouse, we have recently shown that cardiac function in adult mice was only moderately impaired 4 weeks after Serca2 gene disruption, despite a dramatic decrease in SERCA2 protein in the myocardium (Andersson et al. 2009a). From week 4 to week 7 the mice progressively develop impaired myocardial systolic and diastolic dysfunction (Andersson et al. 2009a; Louch et al. 2010).

In this study, we aimed to investigate the role of specific SERCA ATPases in skeletal muscle function. We hypothesized that disruption of Serca2 in slow-twitch skeletal muscle would cause impaired muscle contraction and slowed relaxation, similar to the phenotype of the Serca1−/− mouse in fast-twitch muscle. To this end, we have made a new mouse model in which the Serca2 gene is disrupted in skeletal muscles under the control of the Mlc1-f gene promoter (Bothe et al. 2000; Andersson et al. 2009b). This model gives us the first opportunity to study the consequence of strongly reduced SERCA2 abundance in adult mice in vivo using whole skeletal muscle preparations. We show that the Serca2 gene is disrupted specifically in skeletal muscles, and that only slow-twitch fibres are affected. Our results suggest that reduced SERCA function per se contributes to slowed relaxation, but not to reduction in maximal force in skeletal muscle.

Methods

Animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Norwegian National Committee for Animal Welfare Act, which closely conforms to NIH guidelines, and were approved by the Norwegian Animal Research Authority. Mice were housed in M2 or M3 cages with Bee Kay bedding (Scanbur BK, Nittedal, Norway) in 55% humidity at 22°C on a 12 h light/dark cycle. Food pellets (RM1, 801151, Scanbur BK) and water were freely available. All experiments were performed on adult 3- to 4-month-old mice. Tissue for biochemical and molecular analysis were harvested from animals killed by cervical dislocation after they were first deeply sedated by administering isoflurane (Forene, Abbott, Solna, Sweden) in ambient air in a small container.

Generation of the skeletal muscle-specific Serca2 knockout mice

Mice carrying loxP sites in the Serca2 gene locus, Serca2flox (Andersson et al. 2009b) (MGI ID 4414896), were mated with mice that express Cre recombinase in the myosin light chain 1-fast (Mlc-1f) gene locus (Bothe et al. 2000) (kindly provided by Steven J. Burden, Langone Medical Centre, New York University, USA) to generate Serca2flox/floxMlc-1fwt/cre (skKO) mice. Serca2flox/flox (FF) mice were used as controls. All mice were on the B6/J background. The presence or absence of the Cre transgene and the excised Serca2 allele (Serca2Δ) were detected by PCR analysis as described previously (Andersson et al. 2009b).

Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Total RNA was isolated from the soleus, extensor digitorum longus (EDL), gastrocnemius, diaphragm, pectoralis, cardiac left ventricle and spleen of skKO mice and control FF mice (RNeasy Fibrous Tissue kit, Quiagen). RNA samples were subjected to quality control as described (Andersson et al. 2009a). RT-qPCR reactions were run with an equivalent of 1.25 μl transcribed RNA in a final volume of 25 μl. Taqman gene expression assays (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) for Serca2 (Atp2a2, Mm01201431_m1), Serca1 (Atp2a1, Mm00476050_m1), Serca3 (Atp2a3, Mm00443897_m1), Ryr1 (Ryr1, Mm01175195_m1), Dhpr (Cacna1s, Mm00489257_m1), Pmca1 (Atp2b1, Mm01245805_m1), Pmca4 (Atp2b4, Mm01285597_m1), Ncx1 (Slc8a1, Mm0441524_m1), Ncx2 (Slc8a2, Mm00455836_m1) Ncx3 (Slc8a3, Mm00475515_m1), Sarcalumenin (Srl, Mm00614763_m1), Parvalbumin (Pvalb, Mm00443100_m1) and Gapdh (Gapdh, Mm99999915_g1), were used. Transcript abundance was calculated using relative standard curves and PCR efficiency corrections for each gene assay, and was normalized to Gapdh.

Immunoblotting

Total protein was isolated from the soleus, EDL, gastrocnemius, diaphragm, pectoralis, cardiac left ventricle and spleen. The total SR Ca2+ ATPase content in the soleus muscle was estimated by comparing Western blot band intensities of soleus total homogenates with total homogenates of heart and EDL as 100% standards for SERCA2 and SERCA1, as described for rat (Wu & Lytton, 1993). Primary antibodies for protein detection were as follows: anti-SERCA2a (ab2861, Abcam, Cambridge, UK), anti-SERCA1 (MA3-912, Affinity BioReagents, Golden, CO, USA), anti-SERCA3 (PA1-910A, Affinity BioReagents, anti-total phospholamban (MA3-922, Affinity BioReagents), anti-phospho threonine 17 phospholamban (A010-13) and anti-phospho serine 16 phospholamban (A010-12, Badrilla, Leeds, West Yorkshire, UK). Blots were incubated with HRP-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG or donkey anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibodies (GE Healthcare Biosciences) and detected in a LAS-4000 CCD detection system (Fuji Photo Film Europe GmbH, Düsseldorf, Germany). After immunoblotting, membranes were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R250 (Sigma Aldrich Co., St Louis, MO, USA) and scanned for verification of equal protein loading and sample transfer.

Immunohistochemistry

Soleus muscles were surgically removed and lightly stretched between two pins in a silicon mould filled with O.C.T. compound (Tissue Tech). Muscles were frozen in pre-cooled isopentane in liquid nitrogen. Serial sections (10 μm) were prepared using a cryostat microtome (Cryo-Star HM 560 MV, Microm International). Overall morphology was assessed by staining with eosin–haematoxylin staining (Sigma Aldrich). Myosin heavy chain I (MHCI), myosin heavy chain II (MHCII), SERCA1 and SERCA2 distribution were analysed by staining with anti-MHCI, anti-MHCII (Vector Laboratories), anti-SERCA1(MA3-912, Affinity BioReagents) and anti-SERCA2a (ab2861, Abcam). All sections were double stained with anti-dystrophin (PA1-21011, Affinity BioReagents) for visualization of the fibre membrane in order to distinguish neighbouring fibres. Alexa 488 (Invitrogen, Eugene, OR, USA) was applied for visualization. When assessing the distribution of SERCA and MHC, a random area was selected. The same area was analysed in all serial sections. Positively stained fibres were counted and were calculated as the percentage of total fibres in the area.

Electron microscopy (EM)

Soleus muscles were dissected from skKO and FF mice and lightly stretched between two pins in a silicon mould filled with 3.5% glutaraldehyde in 0.1 m sodium cacodylate buffer for 2 h. At the end of the 2 h fixation period, the muscle was split and cut into small pieces. The fixed muscles were rinsed in buffer, postfixed in 1% OsO4 in the same buffer for 45 min at 4°C, stained en bloc with 0.5% uranyl acetate in H2O for 45 min at 4°C, dehydrated and embedded in Epon. Ultrathin sections were examined in a Tecnai G2 Spirit electron microscope and images were sampled at a magnification of 11,000 times using an Eagle 4k CCD camera (FEI, The Netherlands). The relative SR volume was estimated in the A-band, where longitudinal SR is located, using the well-established stereology point-counting technique (Mobley & Eisenberg, 1975). Briefly, two images of each fibre covering a large volume of fibre cross-sections were covered with an orthogonal array of dots at a spacing of 200 nm. The ratio of the number of dots falling over the SR to the total number of dots covering the A-band gave the SR volume as percentage of total A-band volume.

SR Ca2+ uptake rates

Ca2+ uptake rates in SR vesicles from whole muscle homogenates were measured based on methods described previously (O'Brien, 1990; Simonides & van Hardeveld, 1990; Ruell et al. 1995). Soleus muscles from skKO and FF animals were quickly excised and six muscles from three animals were pooled together before homogenization in ice-cold homogenization buffer containing 300 mm sucrose, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm NaN3, 40 mm Tris HCl, 40 mm l-histidine, pH 7.9. Homogenates were frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C.

The rate of Ca2+ uptake was obtained by measuring the fluorescence signal of the Ca2+-binding dye fura-2 (pentapotassium salt) in a LS50B spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer Ltd, Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, UK). The ratio of fluorescence intensities of fura-2 was measured at excitation wavelengths 340 nm and 380 nm. Emission wavelength was at 510 nm. Fura-2 (2 μl of 1 mm, final 0.86 μm) was added to the assay buffer (165 mm KCl, 22 mm Hepes, 7.5 mm oxalate, 11 mm NaN3, 5.5 μm TPEN, 4.5 mm MgCl2, 100 mm Tris HCl) containing 100 μl of protein homogenate in a plastic cuvette with a constant temperature of 37°C and continuous magnetic stirring. Ca2+ uptake was initiated by adding MgATP (final 1.1 mm). The uptake ratio was measured in duplicates. To estimate whether non-SERCA Ca2+ ATPases contributed to the Ca2+ uptake, the SERCA pump blocker thapsigargin was added prior to the MgATP in control experiments.

Each Ca2+ fluorescence curve was smoothed using the Savitzky–Golay algorithm (TableCurve 2D v5.0, Systat Software, Chicago, IL, USA), and converted to free [Ca2+] according to the equation: [Ca2+] = Kd ((R–Rmin)/(Rmax–R))(Sf2/Sb2) where Kd = 224 nm is the dissociation constant of fura-2 and Sf2/Sb2 is the ratio measured fluorescence intensity at 380 nm when fura-2 is Ca2+ free or saturated respectively. R is the fluorescence ratio, Rmin is the ratio at very low [Ca2+]i and Rmax is the ratio at saturating [Ca2+]i (Grynkiewicz et al. 1985). The Rmin, Rmax and Sf2/Sb2 were determined in each run. The average values were 0.91, 10.55 and 5.7, respectively. The Ca2+ uptake rate was obtained as the first derivative curve of the smoothed [Ca2+]free versus time graph. The rates were normalized to total muscle protein (μmol s−1 (mg protein)−1). The Ca2+ uptake curves were fitted to a Hill equation (SigmaPlot 11.0, Systat Software) to obtain values for the maximal Ca2+ uptake rates, Vmax, and pCa50, the [Ca2+] at 50% of Vmax.

Intact whole soleus muscle contractility

Animals were sedated by 5% isoflurane in ambient air. During deep sedation a tracheal tube was quickly inserted through a small incision and connected to a rodent ventilator. The animals were kept under anaesthesia by ventilating the lungs with 2% isoflurane in ambient air. After checking for absence of the limb withdrawal reflex, soleus muscles were isolated and removed from the limb and the animals were killed by cervical dislocation. Soleus muscles were mounted horizontally in a tissue bath (In vitro Test System, Aurora Scientific Inc., Ontario, Canada) containing oxygen-perfused Ringer solution (122 mm NaCl, 2.8 mm KCl, 1.2 mm MgSO4, 1.2 mm KH2PO4, 25 mm NaHCO3, 5 mm glucose, 1.3 mm CaCl2) at a constant temperature of 30°C. Muscle fibre length and stimulation voltage were adjusted to maximal twitch force.

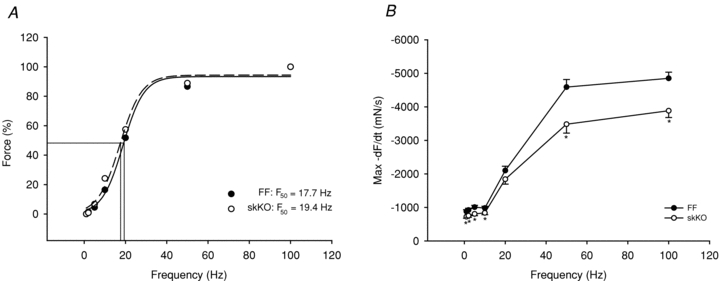

Frequency stimulation

Each muscle preparation was field stimulated at 7 different frequencies between 1 and 100 Hz at 1 min intervals. The muscle was stimulated for 2 s and a plateau was reached at each frequency. Maximal force, maximal contraction rates and maximal relaxation rates were calculated for each frequency. Force was normalized to maximal force in order to calculate F50 (the frequency at 50% of maximal force) using the Hill equation.

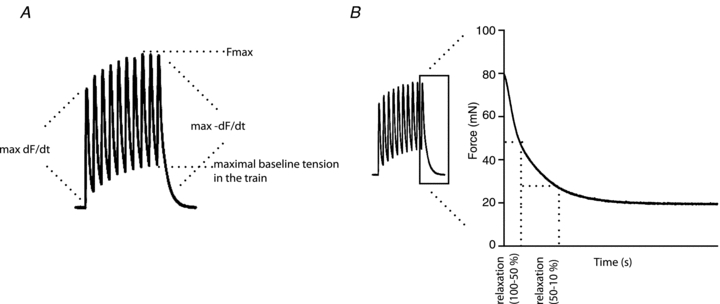

Fatigue protocol

Muscles were stimulated to fatigue either at 5 Hz for 2 s with 3 s intervals for 5 min or at 50 Hz for 750 ms with 2 s intervals for 3.5 min. Recovery was estimated with 5 Hz stimulations after 1, 5, 10, 15, 20 and 30 min after ending the 5 Hz fatigue protocol. Contractile properties at 5 Hz stimulation were analysed by measuring the maximal force during the stimulation train, the maximal baseline tension (the highest baseline tension during the train), the maximal contraction rate (the maximal derivative of the first contraction in the train) and the maximal relaxation rate (the maximal negative derivative of the last contraction in the train, Fig. 1A), at selected time points (0, 10, 20, 30, 60, 120, 180, 240 and 300 s). Relaxation time was measured during the initial phase of decline as time for the force to decline to 50% of maximal force, and during the late phase, as the time for the force to decline from 50 to 10% of maximal force (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1.

A, schematic presentation of contractile measurements. Fmax is the maximal force during the 5 Hz train, the maximal baseline force is the highest baseline force during the train, max dF/dt is the maximum 1st derivative of the force curve of the first contraction in the train, max –dF/dt is the 1st derivative of the relaxation curve from the last contraction in the train. B, schematic presentation of relaxation time measurements. Relaxation time (100–50%) is the time for the force to decline from maximal to 50% of the maximal force, representing the initial relaxation phase. Relaxation time (50–10%) is the time for the force to decline from 50% to 10% of maximal force, representing the late relaxation phase.

For analysis of contractile properties at 50 Hz stimulation, we measured maximal force, maximal contraction rate and maximal relaxation rate at the following time points: 2, 8, 20, 30, 60, 120, 180 and 200 s. Overall differences between skKO and FF throughout the fatigue protocol were compared using area under the curve analysis.

Maximal running capacity

Oxygen uptake, respiratory exchange rate and maximal running speed were tested as previously described (Kemi et al. 2002). In short, skKO and FF mice were placed on a treadmill in a metabolic chamber with ambient air lead through the chamber at a rate of 0.5 l min−1. A 10 min warm-up period was conducted at a treadmill velocity of 0.08 m s−1 at 25% inclination. Treadmill velocity was then increased by 0.03 m s−1 every second minute until the maximal running speed was reached. Maximal running speed was defined as the speed when the mice were not able to run the upper third of the treadmill. Samples of gas flowing at 200 ml min−1 were extracted for measurements of O2 and CO2 levels (Servomex Pm 1155, Servomex Ltd, UK and LAIR 12, M&C Instruments, The Netherlands) at each running velocity.

Statistics

All data are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical comparisons were done by unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test. The level of significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Generation of skeletal muscle-specific Serca2 knockout mice

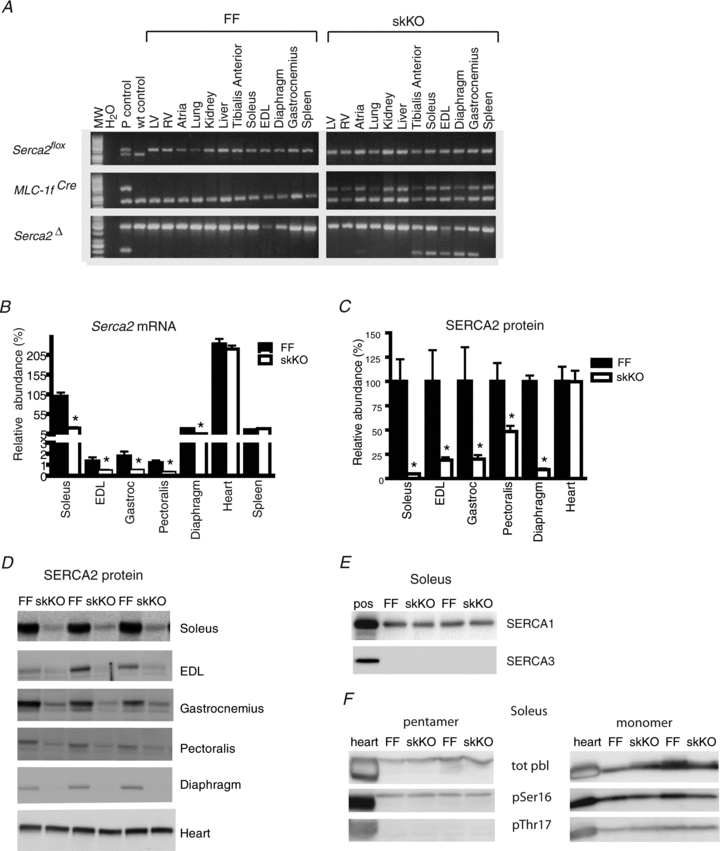

In order to investigate whether reduced activity of the SR Ca2+ ATPase (SERCA2) would lead to impaired muscle function, we generated mice with disruption of the Serca2 gene in skeletal muscles by crossing homozygous Serca2flox/flox mice (Andersson et al. 2009b) with transgenic mice expressing the Cre recombinase within the skeletal muscle-specific Mlc-1f gene locus (Bothe et al. 2000). The resulting Serca2flox/floxMlc-1fwt/cre (skKO) mice were born with the expected Mendelian ratio (data not shown) suggesting that the disruption of Serca2 in skeletal muscles was not lethal in utero. The skKO mice were overall similar to the Serca2flox/flox (FF) control mice with respect to body weight, life span and behaviour under standard housing conditions. PCR analysis confirmed that the Serca2 gene was disrupted in skeletal muscles but not in the heart or in the non-muscle tissues in skKO mice (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2. Disruption of Serca2 in skeletal muscle, Serca2 mRNA and SERCA2 protein abundance in skKO and FF control mice.

A, specificity of Serca2 gene disruption in skKO (Serca2flox/floxMlc-1fwt/cre) mice and control FF (Serca2flox/flox) mice. The presence of various gene alleles was analysed by PCR. Upper panel: loxP2, presence of the homozygous Serca2flox allele in all mice; wt, wt control PCR reaction. Middle panel: Cre, presence of Cre recombinase in the Mlc-1f gene locus; Fabpi 200 bp, autosomal gene internal PCR control. Lower panel: loxP1/P2, presence of the recombined and disrupted Serca2flox allele between loxP sites 1 and 2; Fabpi 500 bp, autosomal gene internal PCR control. The disrupted Serca2flox allele is present only in skKO skeletal muscle tissues (lower right). Tissues: LV, heart left ventricle; RV, heart right ventricle; atria, lung, kidney, liver, tibialis anterior, soleus, EDL, diaphragm, gastrocnemius and spleen. B, Serca2 mRNA quantification by RT-qPCR in skeletal muscle and other tissues as indicated from skKO and FF mice. Values are relative to abundance in FF soleus. C, summary quantification of relative SERCA2 protein abundance in selected tissues from skKO and FF mice. Values are normalized to FF. D, immuno-blots of SERCA2 protein in selected tissues from skKO and FF mice. E, immuno-blots of SERCA1 and SERCA3 protein in soleus muscle of skKO and FF mice. F, immuno-blots of total and phosphorylated phospholamban protein in soleus muscle of skKO and FF mice.

SERCA2 expression and muscle morphology in skKO mice

As a result of Serca2 gene disruption in skKO mice, we found that Serca2 mRNA abundance was reduced to 20%, 35%, 28%, 26% and 27% of FF control values in soleus, EDL, gastrocnemius, pectoralis and diaphragm muscles, respectively (Fig. 2B). Serca2 mRNA abundance was unaltered in the heart and spleen.

In accordance with the reduction in Serca2 mRNA, SERCA2 protein abundance was also reduced in soleus, EDL, gastrocnemius, pectoralis and diaphragm muscles to 5%, 19%, 20%, 48% and 9% of FF controls (Fig. 2C and D). We found no alteration in SERCA2 protein abundance in the heart or spleen. We did not observe any compensatory upregulation of Serca1 and Serca3 mRNA abundance or in SERCA1 and SERCA3 protein abundance in soleus in response to the Serca2 gene disruption (Fig. 2E). Phospholamban is an important regulator of SERCA2 activity. No difference was detected in total phospholamban protein or in phospholamban phosphorylation state (Fig. 2F). Serca2 mRNA abundance was highest in the soleus muscle compared to other skeletal muscles (Fig. 2B). Soleus muscles were therefore chosen for a more detailed investigation.

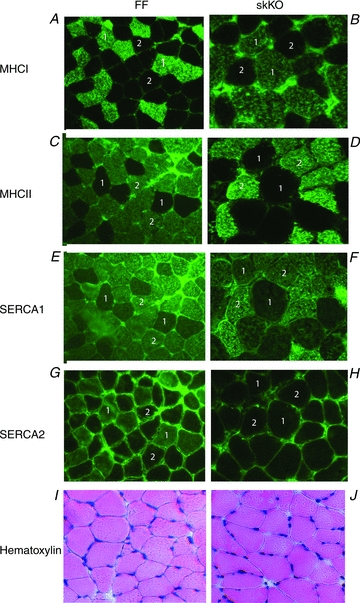

Immunohistochemical analysis of soleus muscle sections showed that the distribution of MHCI and MHCII in the FF was 37.5% and 63.3% (Table 1). The slow and fast-twitch fibre distribution was unchanged in skKO compared to FF; however, there was a tendency towards more fibres expressing MHCI in skKO (P = 0.08). In the FF controls, SERCA2 protein expression was localized to slow-twitch fibres (Fig. 3A and G) and SERCA1 expression was correlated to fast-twitch fibres (Fig. 3C and E). In contrast, SERCA2 expression was not detectable in the skKO soleus slow-twitch fibres (Fig. 3B and H). Interestingly, we found that SERCA1 was expressed in some skKO slow-twitch fibres, increasing the distribution of SERCA1 in the skKO from 62.5% to 69.7% (P = 0.0008, Table 1, Fig. 3F) compared to FF. It might be that some fast-twitch fibres expressing SERCA1 now also express slow-twitch MHCI.

Table 1.

Muscle characteristics of skKO and FF soleus muscle

| FF | skKO | |

|---|---|---|

| Muscle weight (mg) | n = 8 | n = 6 |

| Wet weight | 9.15 ± 0.4 | 9.02 ± 0.2 |

| Dry weight | 1.66 ± 0.3 | 1.62 ± 0.2 |

| Fibre type distribution (% of total fibres) | n = 10 | n = 9 |

| MHCI isoform | 37.5 ± 1.6 | 42.8 ± 2.5 |

| MHCII isoforms | 63.3 ± 1.3 | 58.0 ± 2.3 |

| SERCA isoform fibre distribution (% of total fibres) | n = 10 | n = 9 |

| SERCA1 | 62.5 ± 1.1 | 69.7 ± 1.4* |

| SERCA2 | 40.6 ± 1.7 | No staining |

P = 0.0008.

Figure 3. Fibre types and SERCA staining in skKO and FF soleus muscle.

Staining of fixed cross-sections from skKO and FF soleus muscles as indicated. A–H, myosin heavy chain isoforms (MHCI, MHCII) and SERCA staining show that SERCA1 expression is restricted to fast-twitch fibres whereas SERCA2 expression is restricted to slow-twitch fibres. SERCA2 expression is completely absent in skKO slow-twitch fibres. 1 slow-twitch fibres positive for MHCI (A and B), negative for MHCII (E and F), negative for SERCA1 (G and H) and positive for SERCA2 (G), except for skKO muscle where SERCA2 is negative (H). 2 fast-twitch fibres negative for MHCI (A and B), positive for MHCII (C and D), positive for SERCA1 (E and F) and negative for SERCA2 (G and H). I and J, haematoxylin–eosin staining indicates similar basic structure and no sign of atrophy or degeneration of the skKO muscle fibres.

We determined the abundance of SERCA1 and SERCA2 in soleus muscles of FF mice by comparing Western blot band intensities using EDL and heart homogenates as standard curves. We found a 4-fold higher protein abundance of SERCA1 in EDL than in soleus, and a 17-fold higher protein abundance of SERCA2 in the heart than in soleus (data not shown).

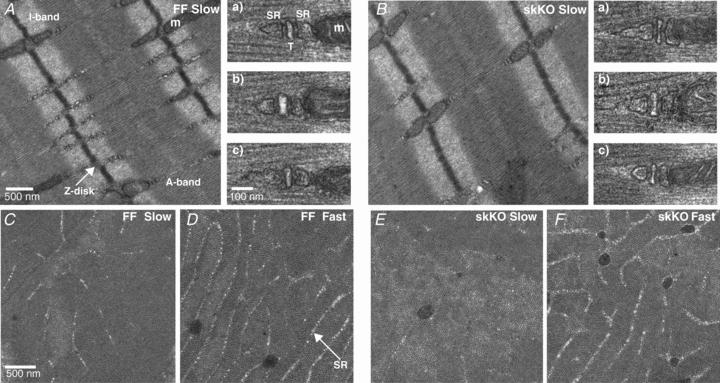

We did not find any difference in the wet/dry weight ratio (Table 1), or in the overall morphology examined by haematoxylin–eosin staining (Fig. 3I and J) between the soleus muscles from skKO and FF control mice, suggesting that Serca2 gene disruption did not result in muscle atrophy or degeneration. Ultrastructural analysis of the skKO soleus muscle showed an overall normal architecture of the muscle fibres, similar structure of the triads and similar cisternal SR volumes (Fig. 4A, Aa–c, and B, Ba–c). Interestingly, we found an overall 26% reduction in the relative longitudinal SR volume in the A-band of skKO (P = 0.058, Table 2). In agreement with previous studies (Luff & Atwood, 1971; Van Winkle & Schwartz, 1978), we found that the SR volume is lower in slow-twitch fibres than in fast-twitch fibres (Fig. 4C–F). Since only slow-twitch fibres are affected by the Serca2 gene disruption, we conducted a crude fibre typing based on observations of SR volume. The fraction of slow-twitch fibres (40–50%) was consistent with the MHCI staining distribution. In the slow-twitch fibres, the SR volume was decreased by 69% in skKO compared to FF (P = 0.004, Table 2). In contrast, the SR volume in the fast-twitch fibres was not different in both skKO and FF controls.

Figure 4. Muscle structure in skKO and FF soleus muscle.

A and B, electron micrographs of slow-twitch fibres from ultrathin longitudinal skKO and FF muscle sections. The images show the overall architecture of the muscle fibres with evenly distributed Ca2+ release units, consisting of triads of two cisternal SR and one t-tubule (T) (a, b, c). m is mitochondria. C–F, SR abundance in the A-band of cross-sectional FF and skKO slow and fast fibres.

Table 2.

Total SR volume in skKO and FF soleus muscle

| Total SR volume (% of total volume) All fibres | Total SR volume (% of total volume) Type I fibres | Total SR volume (% of fibre volume) Type II fibres | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FF | 2.17 ± 0.21 (n = 39) | 1.17 ± 0.16 (n = 16) | 2.86 ± 0.26 (n = 23) |

| skKO | 1.60 ± 0.20* (n = 43) | 0.58 ± 0.12** (n = 23) | 2.78 ± 0.20 (n = 20) |

P = 0.058

P = 0.004.

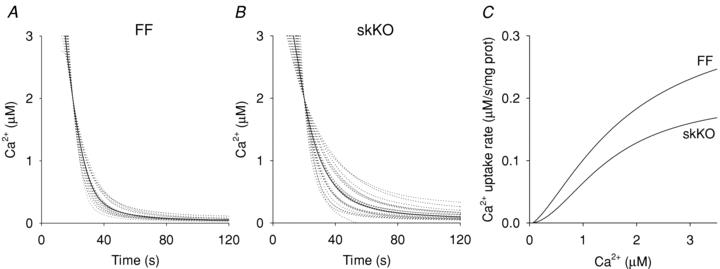

Ca2+ uptake rates in the soleus muscle

To determine whether the strongly reduced SERCA2 protein abundance in soleus affected the uptake of Ca2+ into the SR, we measured Ca2+ uptake rates in SR vesicles from skKO and FF muscle homogenates. Figure 5A and B shows the individual uptake curves (dotted lines) and the medians of the individual uptake rates (continuous lines) made to intersect at 2 μm Ca2+. The median Ca2+ uptake rate at 2 μm Ca2+ was reduced by 28% in skKO (0.14 ± 0.01 μm s−1 (mg protein)−1) compared to FF controls (0.20 ± 0.01 μm s−1 (mg protein)−1, P < 0.004). Maximal Ca2+ uptake rates, Ca2+ sensitivity (K0.5) and pump cooperativity were obtained from Hill curves fitted to the median Ca2+ uptake curves (Fig. 5C). The maximal Ca2+ uptake rate (Vmax) was 0.34 μm s−1 (mg protein)−1 in the FF and 0.20 μm s−1 (mg protein)−1 in the skKO. The K0.5 was 1.78 μm in the FF and 1.49 μm in the skKO. The Hill coefficient was 1.45 in the skKO and 1.89 in the FF. With a fixed Hill coefficient of 1.9 (FF genotype), Vmax was reduced by 22% in skKO (FF: 0.26, skKO: 0.20 μm s−1 (mg protein)−1). Ca2+ uptake was completely blocked in the presence of the SERCA inhibitor thapsigargin, excluding the possibility that non-SERCA Ca2+ ATPases were contributing to the Ca2+ uptake measurements (data not shown).

Figure 5. Ca2+ ATPase activity in skKO and FF soleus muscle.

A and B, Ca2+ uptake curves for FF (n = 9) and skKO (n = 10) soleus muscle homogenates. Dotted lines are individual uptake curves (each sample was run in duplicates) moved to intersect at 2 μm Ca2+. Continuous lines are median curves. C shows calculated Hill curves from the median data in A and B.

Contractile function in skKO soleus muscle

Since both SERCA2 protein abundance and Ca2+ ATPase transport was reduced in skKO soleus muscle, we examined the contractile function in skKO and FF whole muscle preparations. In skKO, we found that the maximal relaxation rate was significantly reduced at all examined frequencies (range 15–28%) compared to FF control values, except at 20 Hz (12%) (Fig. 6B). This resulted in a slight leftward shift in the force–frequency relationship (Fig. 6A). Fifty percent of maximal force was obtained at 17.7 Hz in skKO compared to 19.4 Hz in FF (P < 0.05). The maximal contraction rates were similar in both genotypes at all frequencies tested (data not shown).

Figure 6. Contractile properties in skKO and FF soleus muscle.

A, force–frequency relationship. F50 in skKO = 17.7 Hz and F50 in FF = 19.4 Hz (P < 0.05). B, relaxation rate vs. frequency. Muscles were stimulated at 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50 and 100 Hz. skKO (open circles, n = 10) and FF (filled circles, n = 11). *P < 0.05.

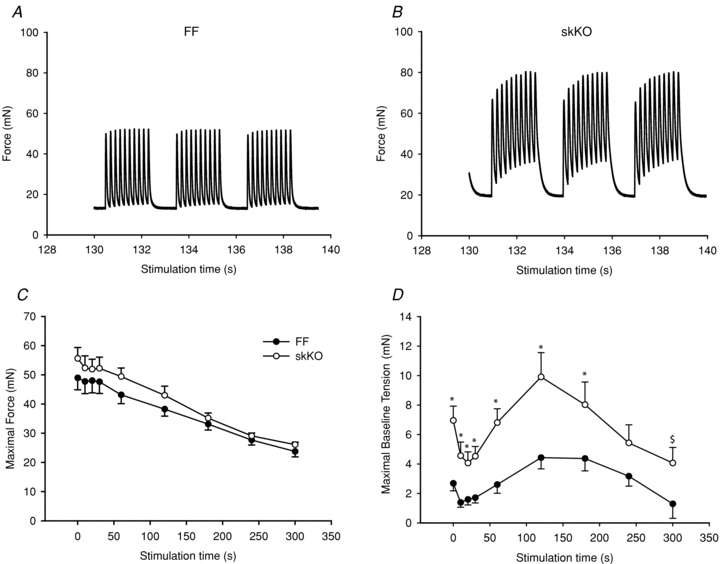

Contractile function in fatiguing skKO soleus muscle

We next investigated whether the slowed relaxation in skKO soleus muscle would become more pronounced during repetitive contractions. During a 5 min in vitro 5 Hz fatigue protocol, both skKO and FF control muscles fatigued to a similar degree with 40–50% reduction in maximal force, maximal contraction rates and maximal relaxation rates (Figs 7A, and 8A and B).

Figure 7. Maximal peak force and maximal baseline tension during 5 Hz fatigue development.

A and B, example of stimulation trains (5 Hz) from FF controls and skKO at the 130–140 s time point in the stimulation protocol. C, the maximal developed force was similar but slightly higher in skKO compared to the FF. D, the maximal baseline tension was increased overall in skKO compared to FF controls: skKO (open circles, n = 10) and FF (filled circles, n = 11). *P < 0.05; $, area under the curve, P < 0.01.

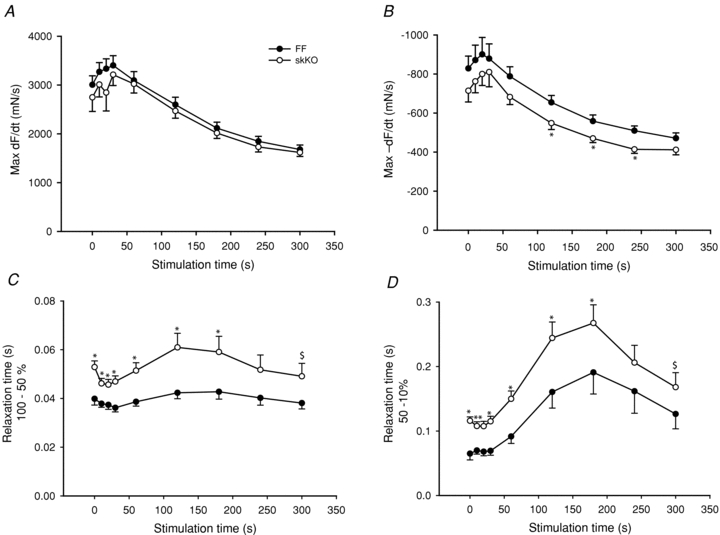

Figure 8. Relaxation rates and times during 5 Hz fatigue development in skKO and FF soleus muscle.

A, maximal contraction rate (maximum dF/dt of first contraction in stimulation train). B, maximal relaxation rate (maximum –dF/dt of last contraction in stimulation train). C, relaxation time from maximal to 50% of maximal force. D, relaxation time in the interval from 50 to 10% of maximal force. skKO (open circles, n = 10) and FF (filled circles, n = 11). *P < 0.05; $, area under the curve, P < 0.01.

The maximal force was slightly increased in the skKO throughout the protocol duration, but area under the curve analysis did not reveal significant differences between skKO and FF (Fig. 7C). However, the maximal baseline tension was overall significantly higher in the skKO compared to the FF (Fig. 7D). The increase was most prominent in the middle section of the protocol with a 2.2-fold increase at the 120 s time point (P = 0.005, Fig. 7A, B and D). Maximal contraction rates were similar in skKO and FF controls throughout the fatigue protocol (Fig. 8A). In skKO, the maximal relaxation rate was reduced throughout the 300 s fatigue protocol and significantly reduced in the middle of the protocol in the skKO (to 84% of FF control at the 120 s time point, P < 0.05, Fig. 8B). Overall, the relaxation time (100–10% force decline) was significantly prolonged by 30% (P = 0.01) in skKO compared to FF controls (data not shown). To distinguish between the early faster phase and the late slower phase of muscle relaxation, we analysed the relaxation properties separately for the early relaxation phase (100–50% force decline) and the late relaxation phase (50–10% force decline). The relaxation time was slower in the skKO in both relaxation phases at all time points measured during the fatigue stimulation protocol, but was not significantly altered at the end of the protocol (Fig. 8C and D). Overall, the relaxation time was slowed in the skKO by 24.7% (P = 0.007) in the early phase and by 32.2% (P = 0.015) in the late phase. The recovery rates for skKO and FF soleus were similar and nearly complete 30 min after completion of the fatigue protocol (data not shown).

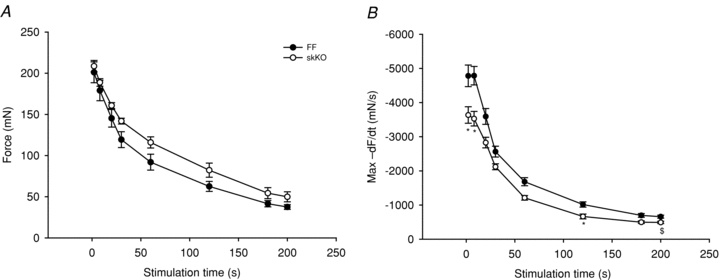

We also examined contractile function during a 50 Hz stimulation protocol during which the SR Ca2+ release would be higher than in the 5 Hz stimulation protocol. Again, skKO and FF control muscles fatigued to a similar degree. Further, maximal force was slightly increased in the skKO throughout the protocol duration, but area under the curve analysis did not reveal significant differences between skKO and FF (Fig. 9A). Maximal contraction rate was not different between skKO and FF (not shown). However, the relaxation was slowed in skKO compared to FF, notably overall significantly slowed during the 50 Hz compared to the 5 Hz stimulation protocol.

Figure 9. Maximal peak force and relaxation rates during 50 Hz fatigue development in skKO and FF soleus muscle.

Similar to the 5 Hz data, maximal developed force (A) was similar but slightly higher in skKO compared to FF, and the relaxation rate was slowed in skKO compared to FF (B). skKO (open circles, n = 5) and FF (filled circles, n = 7). *P < 0.05; $, area under the curve, P < 0.05.

In vivo dynamic exercise in skKO mice

Given the large reduction in SERCA2 protein abundance in all skeletal muscles containing slow-twitch fibres, and the slowed relaxation observed in soleus whole muscles, we tested the performance of skKO mice during treadmill running. In skKO mice, the running speed was slightly reduced compared to FF controls (P = 0.055) (Table 3). There were no differences in the oxygen uptake between the genotypes, confirming that the heart was not affected by Serca2 disruption (Table 3). The respiratory exchange rate (RER) was used as an indirect criterion for reaching  . A RER above 1 suggests that

. A RER above 1 suggests that  is obtained (Kemi et al. 2002). The RER values were in the range of 0.93 and 0.99, indicating that the mice did not reach

is obtained (Kemi et al. 2002). The RER values were in the range of 0.93 and 0.99, indicating that the mice did not reach  , and the oxygen uptake is therefore reported as

, and the oxygen uptake is therefore reported as  (Table 3). The reduced maximal running speed suggests that the slowed relaxation could have an impact on whole body movement in slowing the frequency with which alternate movements can be performed (Allen et al. 1995).

(Table 3). The reduced maximal running speed suggests that the slowed relaxation could have an impact on whole body movement in slowing the frequency with which alternate movements can be performed (Allen et al. 1995).

Table 3.

Running capacity in skKO and FF mice

(ml·kg−1·min−1) (ml·kg−1·min−1) |

RER ( / / ) ) |

Maximal running speed (m s−1) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FF (n = 8) | 127 ± 1.78 | 0.95 ± 0.01 | 0.43 ± 0.01 |

| skKO (n = 6) | 126 ± 1.21 | 0.94 ± 0.02 | 0.38 ± 0.02* |

RER, respiratory exchange rate.

P = 0.055.

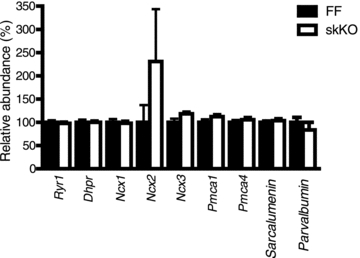

mRNA expression of other Ca2+-handling proteins

We next examined whether the abundance of other Ca2+-handling or regulatory proteins were altered in response to disruption of Serca2. The abundance of Ryr1, Dhpr, Ncx1, Ncx2, Ncx3, Pmca1, Pmca 4, Sarcalumenin and Parvalbumin mRNA were quantified by qRT-PCR in FF and skKO soleus muscles. We did not find any significant change in abundance of these transcripts in skKO compared to FF controls (Fig. 10).

Figure 10. mRNA expression of Ca2+-handling proteins in skKO and FF soleus muscle.

mRNA quantification of several Ca2+-handling proteins by RT-qPCR in soleus muscle from KO and FF mice. Values are normalized to FF controls.

Discussion

Ca2+ ATPases play a major role in muscle function and reduced SERCA activity has been observed in skeletal muscle disease as well as in skeletal muscle fatigue. In this study, we show for the first time that targeted disruption of Serca2 in skeletal muscles (skKO) resulted in viable mice with a reduction in SERCA2 protein in several muscles with slow-twitch fibres. SERCA2 was most markedly reduced in soleus muscle, by 95%. Muscle structure was preserved, albeit with reduced longitudinal SR volume. Relaxation was prolonged; however, the maximal force was maintained in contracting soleus muscles.

Disruption of the Serca2 gene was targeted specifically to skeletal muscle by using the Cre-lox strategy where the expression of Cre recombinase was controlled by the skeletal muscle-specific Mlc-1f (myosin light chain-1 fast) gene promoter (Bothe et al. 2000). We show here that it is possible to achieve disruption of a gene with expression restricted to slow-twitch fibres, even though the Mlc-1f gene is expressed in fast-twitch muscle fibres in adult mice. This strategy succeeded because the Mlc-1f gene is uniformly expressed in embryonic skeletal muscle as early as 9.5 days post coitum (d.p.c.), before embryonic muscle differentiates into fast- and slow-twitch fibres after 15.5 d.p.c (Lyons et al. 1990). We show that the Serca2 gene was disrupted in multiple skeletal muscles in adult mice. Most skeletal muscles in B6/J mice are mixed muscles, consisting of both fast and slow-twitch fibres. The soleus muscle, which has the highest distribution of slow-twitch fibres (40%), was the most affected by Serca2 disruption and was therefore chosen for further physiological experiments.

The Ca2+ uptake rate of vesicles in the tissue homogenate is shown to reflect the amount of Ca2+ ATPase in the preparation (Lytton et al. 1992; Wu & Lytton, 1993). The estimate of Vmax was dependent on whether the Hill coefficient was allowed to vary freely or not during the fitting of the curve to the data. The Hill coefficient has not been reported to be different between SERCA1 and SERCA2 (Lytton et al. 1992) and hence removing SERCA2 would not be expected to have any effect on the coefficient. Also fitting is more robust with fewer free variables. Hence, the best estimate of the reduction in Vmax, due to the absence of SERCA2 from the soleus, is probably closer to 20% than to 40% which fits with the 28% reduction directly observed at the Ca2+ concentration of 2 μm. Assuming that the Ca2+ uptake rate reflects Ca2+ ATPase abundance, the Ca2+ uptake data suggest that SERCA2 accounts for 20–40% of total Ca2+ ATPase in soleus, in keeping with the results in rat where SERCA2 protein accounted for 45% of total Ca2+ ATPase in rat soleus, which contain 80% of slow-twitch fibres (Wu & Lytton, 1993). We estimated the contribution of SERCA2 to the total Ca2+ ATPase in soleus by relating SERCA1 and SERCA2 abundance in soleus to EDL (100% SERCA1 abundance) and heart (100% SERCA2 abundance) maximal Ca2+ uptake rates. In the soleus, SERCA1 abundance was 25% of EDL, and SERCA2 abundance was 5.8% of heart. In our lab, the maximal Ca2+ uptake rates in EDL and heart tissue homogenates with similar total protein contents to those in our soleus homogenates, were approximately 1.7 μm s−1 mg−1 (EDL, data not shown) and 2 μm s−1 mg−1 (heart, K. Hougen, personal communication). Correcting for SERCA1 and SERCA2 abundance in soleus, the estimated contributions of SERCA1 and SERCA2 to the maximal Ca2+ uptake rates were approximately 0.43 and 0.12 μm s−1 mg−1 for SERCA1 and SERCA2, respectively. These data suggest that SERCA2 accounts for approximately 22% of total SR Ca2+ uptake and total Ca2+ ATPase in soleus assuming Ca2+ uptake rate reflects the amount of Ca2+ ATPase. In contrast, Norris and co-workers found that SERCA2 protein accounted for only 7% of the total Ca2+ ATPase in mouse soleus (Norris et al. 2010).

The main location of SERCAs in muscle is in the longitudinal SR, with very few molecules in the junctional SR cisternae (Costello et al. 1986; Franzini-Armstrong et al. 1987). Longitudinal SR was present at the A-band of slow-twitch fibres from the skKO muscles, but the volume was reduced by 26% on average for all fibres analysed. However, fibre typing is difficult in EM cross-sections, and since SR volume is lower in slow-twitch fibres than in fast-twitch fibres (Luff & Atwood, 1971; Van Winkle & Schwartz, 1978), the reduction in SR volume could be a mere consequence of more slow-twitch than fast-twitch fibres being analysed in the skKO than in FF fibres. Although somewhat biased, the fibres were grouped into slow- and fast-twitch fibres based on observations of SR content in the A-band. By this grouping, the fraction of slow-twitch fibres (40–50%) was consistent with the MHCI staining distribution, and when only considering what we observed to be slow-twitch fibres, SR volume was decreased by 69% in skKO. This suggests that SR volume is strongly reduced in skKO fibres.

In contrast, the structure of the triads and of the SR cisternal volume was similar in both genotypes. Accordingly, there was no difference between skKO and FF in the abundance of calsequestrin protein (data not shown) which is a marker of the SR cisternal volume (Franzini-Armstrong et al. 1987). Also, there are few SERCA molecules in this SR region. Others have observed proliferation of junctional SR vesicles, or alterations in the volume of the terminal SR cisternae in response to alterations in SR Ca2+-handling proteins (Knollmann et al. 2006; Paolini et al. 2007). Thus, it seems that loss of SERCA2 did not affect formation of the SR, but since SERCA2 is abundant and widely distributed in longitudinal SR, loss of SERCA2 seems to affect mainly the longitudinal SR volume and structure. Alternatively, the reduction in longitudinal SR volume may be a compensatory mechanism to concentrate a smaller amount of Ca2+ near the Ca2+ release sites in the cisternal SR due to a lower SR Ca2+ content.

As expected, reduced SERCA2 abundance and Ca2+ uptake rates resulted in slowed relaxation in skKO soleus muscles compared to FF controls. The muscles were, however, able to fully relax, suggesting functional slow-twitch fibres in which Ca2+ is removed from the cytosol despite the absence of SERCA2, albeit at a reduced rate. Surprisingly, the maximal contractile force and contraction rates were not reduced during single contractions, or during repetitive contractions tested at both low and high frequencies in skKO soleus compared to FF controls. We expected that reduced SERCA2 abundance in slow-twitch fibres would give reduced SR Ca2+ content and therefore less Ca2+ available for contraction, resulting in reduced force. In cardiac-specific SERCA2KO mice the SR Ca2+ content in the cardiomyocytes was reduced by 60–70% (Andersson et al. 2009a) and a correlation between Ca2+ release and Ca2+ content has been shown previously (Shannon et al. 2000; Trafford et al. 2001). The maximal force was actually slightly higher in the skKO throughout the fatigue protocols with both 5 and 50 Hz contractions, and careful analysis revealed a minor leftward shift in the force–frequency relationship. Assuming that slow-twitch and fast-twitch fibres generate similar maximal forces, we expected up to 40% reduction in the maximal force since slow-twitch fibres in the skKO soleus constitute 40% of the total fibres. These findings suggest that slow-twitch fibres in skKO are able to contribute to the total force production in whole soleus muscle despite the loss of SERCA2.

We did not find any upregulated expression of either SERCA1 or SERCA3 mRNA or protein, similar to previous findings in a cardiac-specific SERCA2KO (Andersson et al. 2009a) and in the SERCA1-deficient mice (Pan et al. 2003). In skKO soleus, the remaining pool of SERCA2 protein was estimated to be 5% and we found that some slow-twitch fibres expressed SERCA1. There was no difference between skKO and FF in the abundance or the phosphorylation status of the regulatory protein phospholamban. Although the total phospholamban/SERCA2 ratio was increased due to the reduction in SERCA2, we did not determine whether this had an effect on ATPase activity of the remaining 5% SERCA2 protein.

Since Serca2 gene disruption took place in early development one can imagine that Ca2+ has never been taken up into the SR. We have not measured SR load and we cannot exclude the possibility that an unknown mechanism has developed that participates in Ca2+ loading of the SR. Another possibility could be that the 5% remaining SERCA2 is able to refill the SR with a small amount of Ca2+. If so, a small release of Ca2+ in the skKO fibres may produce a Ca2+ transient of sufficient magnitude to saturate the Ca2+ binding sites on troponin C, or together with reduced removal of cytosolic Ca2+, contribute to the accumulation of [Ca2+]i in the cytosol that could result in increased tension (Westerblad & Allen, 1994b). However, we find it unlikely that such a small pool of SERCA2 is capable of cycling sufficient Ca2+ to maintain muscle force. In cardiac SERCA2KO myocytes, the small amount of SERCA2 in the SR contributed very little to the Ca2+ transients (Andersson et al. 2009a). Also, during repetitive stimulations at high frequencies, a very small amount of SERCA would most likely not refill the SR fast enough and the SR should eventually be depleted of Ca2+ whereas accumulation of Ca2+i in the cytosol should result in fibre contracture. In skinned fast-twitch single fibres with SR loaded with endogenous Ca2+ levels and blocked Ca2+ reuptake, the SR was fully depleted after eight consecutive action potentials (Posterino & Lamb, 2003).

Interestingly, slow-twitch fibre size was similar to FF controls. Muscle fibres without contractile activity would be expected to become atrophic (Thomason & Booth, 1990). The maintained fibre size is additional evidence that there might be contractile activity in the skKO fibres. Several studies argue that passive stretch might be sufficient to inhibit atrophy and maintain the integrity of the sarcomeres (Williams, 1990; Baewer et al. 2004; Coutinho et al. 2004). We can therefore not rule out the possibility that the surrounding contracting fast-twitch fibres induce sufficient passive stretch in the skKO fibres to inhibit atrophy.

Our findings suggest that mechanisms other than SR Ca2+ cycling might be important for maintaining function in skKO fibres. The cytosolic Ca2+ buffer, parvalbumin is expressed in fast-twitch fibres to facilitate a faster relaxation. Slow-twitch fibres have low or no expression of known cytosolic Ca2+ buffers (Reggiani & te Kronnie, 2006). We did not find any increase in parvalbumin expression in skKO soleus muscle in response to the loss of SERCA2.

In the cardiac-specific SERCA2 KO model, where the Serca2 gene is disrupted by tamoxifen-inducible cardiac Cre activity in adult animals, only moderate cardiac dysfunction was observed 4 weeks after tamoxifen administration, despite a 95% reduction in SERCA2 protein (Andersson et al. 2009a). Cardiac function was largely maintained in those animals by enhanced Ca2+ cycling across the sarcolemma through the L-type Ca2+ channel and the sodium calcium exchanger (NCX) 1. However, we found no difference between skKO and FF soleus in the mRNA levels of several of the Ca2+-handling proteins in the excitation–contraction cycle. There was a tendency towards upregulation of the NCX2; however, the NCX2 levels were very low in the skeletal muscle and the variation in the data was high. The low expression levels of NCX isoforms and plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase (PMCA) in skeletal muscle suggests a very small contribution of these channels to excitation–contraction coupling. However, we have not measured sarcolemmal Ca2+ currents, thus increased sarcolemmal Ca2+ transport in skKO cannot be excluded.

We have shown that SERCA2 protein in gene-targeted mice (skKO) was reduced to 5% of control values in soleus muscle, and the relative volume of longitudinal free SR, in which SERCA protein resides, was reduced. Muscle relaxation was slowed in the contracting soleus muscle of skKO mice. Strikingly, the contractile force was maintained despite the 40% fraction of slow-twitch fibres. Our findings suggest that skKO slow-twitch skeletal muscle fibres may continue to contribute to the total muscle force despite loss of SERCA2 protein. Detailed studies in single fibres, including recordings of Ca2+ transients, Ca2+ uptake and release mechanisms and SR load, are needed to further elucidate contractile function in muscles lacking SERCA2 protein.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Annlaug Ødegaard for technical assistance with mRNA preparation, Sverre Henning Brorson for assisting with the sample preparations for the EM analysis, Per Andreas Norseng for technical assistance with in vitro muscle measurements, and the Section for Comparative Medicine for excellent animal husbandry and breeding. We also gratefully acknowledge Steven J. Burden (NYU, USA) for the transgenic Mlc-1f Cre mice. This work has been funded by The Norwegian Council for Cardiovascular Diseases, Anders Jahre's Fund for the Promotion of Science, the Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority and the University of Oslo.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- EDL

extensor digitorum longus

- EM

electron microscopy

- MHCI

myosin heavy chain I

- MHCII

myosin heavy chain II

- RER

respiratory exchange rate

- SERCA

sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase

- SR

sarcoplasmic reticulum

- NCX

sodium calcium exchanger

- PMCA

plasma membrane calcium pump

Author contributions

C.S., O.M.S., P.K.L. and K.B.A. conceived and designed the experiments. C.S., F.S., M.M., M.E., M.L., P.K.L., S.B. and K.B.A. collected, analysed and interpreted the data. C.S., G.C., Ø.E., O.M.S., P.K.L. and K.B.A. drafted the article or revised it critically for important intellectual content. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. The experiments were performed in the laboratories of the Institute of Experimental Medical Research and the Department of Circulation and Medical Imaging.

References

- Allen DG, Lannergren J, Westerblad H. Muscle cell function during prolonged activity: cellular mechanisms of fatigue. Exp Physiol. 1995;80:497–527. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.1995.sp003864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson KB, Birkeland JA, Finsen AV, Louch WE, Sjaastad I, Wang Y, Chen J, Molkentin JD, Chien KR, Sejersted OM, Christensen G. Moderate heart dysfunction in mice with inducible cardiomyocyte-specific excision of the Serca2 gene. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009a;47:180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson KB, Finsen AV, Sjaland C, Winer LH, Sjaastad I, Odegaard A, Louch WE, Wang Y, Chen J, Chien KR, Sejersted OM, Christensen G. Mice carrying a conditional Serca2flox allele for the generation of Ca2+ handling-deficient mouse models. Cell Calcium. 2009b;46:219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai M, Matsui H, Periasamy M. Sarcoplasmic reticulum gene expression in cardiac hypertrophy and heart failure. Circ Res. 1994;74:555–564. doi: 10.1161/01.res.74.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baewer DV, Hoffman M, Romatowski JG, Bain JL, Fitts RH, Riley DA. Passive stretch inhibits central corelike lesion formation in the soleus muscles of hindlimb-suspended unloaded rats. J Appl Physiol. 2004;97:930–934. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00103.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benders AA, Veerkamp JH, Oosterhof A, Jongen PJ, Bindels RJ, Smit LM, Busch HF, Wevers RA. Ca2+ homeostasis in Brody's disease. A study in skeletal muscle and cultured muscle cells and the effects of dantrolene an verapamil. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:741–748. doi: 10.1172/JCI117393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bothe GW, Haspel JA, Smith CL, Wiener HH, Burden SJ. Selective expression of Cre recombinase in skeletal muscle fibers. Genesis. 2000;26:165–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody IA. Muscle contracture induced by exercise. A syndrome attributable to decreased relaxing factor. N Engl J Med. 1969;281:187–192. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196907242810403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrd SK, Bode AK, Klug GA. Effects of exercise of varying duration on sarcoplasmic reticulum function. J Appl Physiol. 1989;66:1383–1389. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1989.66.3.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello B, Chadwick C, Saito A, Chu A, Maurer A, Fleischer S. Characterization of the junctional face membrane from terminal cisternae of sarcoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol. 1986;103:741–753. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.3.741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coutinho EL, Gomes AR, Franca CN, Oishi J, Salvini TF. Effect of passive stretching on the immobilized soleus muscle fiber morphology. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2004;37:1853–1861. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2004001200011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East JM. Sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum calcium pumps: recent advances in our understanding of structure/function and biology (review) Mol Membr Biol. 2000;17:189–200. doi: 10.1080/09687680010009646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everts ME, Andersen JP, Clausen T, Hansen O. Quantitative determination of Ca2+-dependent Mg2+-ATPase from sarcoplasmic reticulum in muscle biopsies. Biochem J. 1989;260:443–448. doi: 10.1042/bj2600443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franzini-Armstrong C, Kenney LJ, Varriano-Marston E. The structure of calsequestrin in triads of vertebrate skeletal muscle: a deep-etch study. J Cell Biol. 1987;105:49–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inashima S, Matsunaga S, Yasuda T, Wada M. Effect of endurance training and acute exercise on sarcoplasmic reticulum function in rat fast- and slow-twitch skeletal muscles. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2003;89:142–149. doi: 10.1007/s00421-002-0763-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpati G, Charuk J, Carpenter S, Jablecki C, Holland P. Myopathy caused by a deficiency of Ca2+-adenosine triphosphatase in sarcoplasmic reticulum (Brody's disease) Ann Neurol. 1986;20:38–49. doi: 10.1002/ana.410200108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemi OJ, Loennechen JP, Wisloff U, Ellingsen O. Intensity-controlled treadmill running in mice: cardiac and skeletal muscle hypertrophy. J Appl Physiol. 2002;93:1301–1309. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00231.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knollmann BC, Chopra N, Hlaing T, Akin B, Yang T, Ettensohn K, Knollmann BE, Horton KD, Weissman NJ, Holinstat I, Zhang W, Roden DM, Jones LR, Franzini-Armstrong C, Pfeifer K. Casq2 deletion causes sarcoplasmic reticulum volume increase, premature Ca2+ release, and catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2510–2520. doi: 10.1172/JCI29128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louch WE, Hougen K, Mork HK, Swift F, Aronsen JM, Sjaastad I, Reims HM, Roald B, Andersson KB, Christensen G, Sejersted OM. Sodium accumulation promotes diastolic dysfunction in end-stage heart failure following Serca2 knockout. J Physiol. 2010;588:465–478. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.183517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luff AR, Atwood HL. Changes in the sarcoplasmic reticulum and transverse tubular system of fast and slow skeletal muscles of the mouse during postnatal development. J Cell Biol. 1971;51:369–383. doi: 10.1083/jcb.51.2.369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lunde PK, Sejersted OM, Thorud HM, Tonnessen T, Henriksen UL, Christensen G, Westerblad H, Bruton J. Effects of congestive heart failure on Ca2+ handling in skeletal muscle during fatigue. Circ Res. 2006;98:1514–1519. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000226529.66545.e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons GE, Ontell M, Cox R, Sassoon D, Buckingham M. The expression of myosin genes in developing skeletal muscle in the mouse embryo. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:1465–1476. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.4.1465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lytton J, Westlin M, Burk SE, Shull GE, MacLennan DH. Functional comparisons between isoforms of the sarcoplasmic or endoplasmic reticulum family of calcium pumps. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:14483–14489. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mobley BA, Eisenberg BR. Sizes of components in frog skeletal muscle measured by methods of stereology. J Gen Physiol. 1975;66:31–45. doi: 10.1085/jgp.66.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris SM, Bombardier E, Smith IC, Vigna C, Tupling AR. ATP consumption by sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ pumps accounts for 50% of resting metabolic rate in mouse fast and slow twitch skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;298:C521–C529. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00479.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien PJ. Calcium sequestration by isolated sarcoplasmic reticulum: real-time monitoring using ratiometric dual-emission spectrofluorometry and the fluorescent calcium-binding dye indo-1. Mol Cell Biochem. 1990;94:113–119. doi: 10.1007/BF00214118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odermatt A, Taschner PE, Khanna VK, Busch HF, Karpati G, Jablecki CK, Breuning MH, MacLennan DH. Mutations in the gene-encoding SERCA1, the fast-twitch skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase, are associated with Brody disease. Nat Genet. 1996;14:191–194. doi: 10.1038/ng1096-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y, Zvaritch E, Tupling AR, Rice WJ, de Leon S, Rudnicki M, McKerlie C, Banwell BL, MacLennan DH. Targeted disruption of the ATP2A1 gene encoding the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+ ATPase isoform 1 (SERCA1) impairs diaphragm function and is lethal in neonatal mice. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13367–13375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M213228200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolini C, Quarta M, Nori A, Boncompagni S, Canato M, Volpe P, Allen PD, Reggiani C, Protasi F. Reorganized stores and impaired calcium handling in skeletal muscle of mice lacking calsequestrin-1. J Physiol. 2007;583:767–784. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.138024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Periasamy M, Reed TD, Liu LH, Ji Y, Loukianov E, Paul RJ, Nieman ML, Riddle T, Duffy JJ, Doetschman T, Lorenz JN, Shull GE. Impaired cardiac performance in heterozygous mice with a null mutation in the sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase isoform 2 (SERCA2) gene. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:2556–2562. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.4.2556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters DG, Mitchell HL, McCune SA, Park S, Williams JH, Kandarian SC. Skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase gene expression in congestive heart failure. Circ Res. 1997;81:703–710. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.5.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posterino GS, Lamb GD. Effect of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ content on action potential-induced Ca2+ release in rat skeletal muscle fibres. J Physiol. 2003;551:219–237. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.040022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reggiani C, te Kronnie T. RyR isoforms and fibre type-specific expression of proteins controlling intracellular calcium concentration in skeletal muscles. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 2006;27:327–335. doi: 10.1007/s10974-006-9076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruell PA, Booth J, McKenna MJ, Sutton JR. Measurement of sarcoplasmic reticulum function in mammalian skeletal muscle: technical aspects. Anal Biochem. 1995;228:194–201. doi: 10.1006/abio.1995.1339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakuntabhai A, Ruiz-Perez V, Carter S, Jacobsen N, Burge S, Monk S, Smith M, Munro CS, O'Donovan M, Craddock N, Kucherlapati R, Rees JL, Owen M, Lathrop GM, Monaco AP, Strachan T, Hovnanian A. Mutations in ATP2A2, encoding a Ca2+ pump, cause Darier disease. Nat Genet. 1999;21:271–277. doi: 10.1038/6784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon TR, Ginsburg KS, Bers DM. Potentiation of fractional sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium release by total and free intra-sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium concentration. Biophys J. 2000;78:334–343. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76596-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonides WS, van Hardeveld C. An assay for sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase activity in muscle homogenates. Anal Biochem. 1990;191:321–331. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(90)90226-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonini A, Chang K, Yue P, Long CS, Massie BM. Expression of skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium-ATPase is reduced in rats with postinfarction heart failure. Heart. 1999;81:303–307. doi: 10.1136/hrt.81.3.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson DG, Lamb GD, Stephenson GM. Events of the excitation–contraction–relaxation (E–C–R) cycle in fast- and slow-twitch mammalian muscle fibres relevant to muscle fatigue. Acta Physiol Scand. 1998;162:229–245. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201X.1998.0304f.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomason DB, Booth FW. Atrophy of the soleus muscle by hindlimb unweighting. J Appl Physiol. 1990;68:1–12. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1990.68.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trafford AW, Diaz ME, Eisner DA. Coordinated control of cell Ca2+ loading and triggered release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum underlies the rapid inotropic response to increased L-type Ca2+ current. Circ Res. 2001;88:195–201. doi: 10.1161/01.res.88.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Winkle WB, Schwartz A. Morphological and biochemical correlates of skeletal muscle contractility in the cat. I. Histochemical and electron microscopic studies. J Cell Physiol. 1978;97:99–119. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1040970110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward CW, Spangenburg EE, Diss LM, Williams JH. Effects of varied fatigue protocols on sarcoplasmic reticulum calcium uptake and release rates. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 1998;275:R99–R104. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.1998.275.1.R99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerblad H, Allen DG. The contribution of [Ca2+]i to the slowing of relaxation in fatigued single fibres from mouse skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 1993;468:729–740. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerblad H, Allen DG. Relaxation, [Ca2+]i and [Mg2+]i during prolonged tetanic stimulation of intact, single fibres from mouse skeletal muscle. J Physiol. 1994a;480:31–43. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerblad H, Allen DG. The role of sarcoplasmic reticulum in relaxation of mouse muscle; effects of 2,5-di(tert-butyl)-1,4-benzohydroquinone. J Physiol. 1994b;474:291–301. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1994.sp020022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams PE. Use of intermittent stretch in the prevention of serial sarcomere loss in immobilised muscle. Ann Rheum Dis. 1990;49:316–317. doi: 10.1136/ard.49.5.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu KD, Lytton J. Molecular cloning and quantification of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase isoforms in rat muscles. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 1993;264:C333–C341. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1993.264.2.C333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuytack F, Dode L, Baba-Aissa F, Raeymaekers L. The SERCA3-type of organellar Ca2+ pumps. Biosci Rep. 1995;15:299–306. doi: 10.1007/BF01788362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wuytack F, Raeymaekers L, De Smedt H, Eggermont JA, Missiaen L, Van Den Bosch L, De Jaegere S, Verboomen H, Plessers L, Casteels R. Ca2+-transport ATPases and their regulation in muscle and brain. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1992;671:82–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1992.tb43786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda T, Inashima S, Sasaki S, Kikuchi K, Niihata S, Wada M, Katsuta S. Effects of exhaustive exercise on biochemical characteristics of sarcoplasmic reticulum from rat soleus muscle. Acta Physiol Scand. 1999;165:45–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-201x.1999.00470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]