Abstract

eEF2K [eEF2 (eukaryotic elongation factor 2) kinase] phosphorylates and inactivates the translation elongation factor eEF2. eEF2K is not a member of the main eukaryotic protein kinase superfamily, but instead belongs to a small group of so-called α-kinases. The activity of eEF2K is normally dependent upon Ca2+ and calmodulin. eEF2K has previously been shown to undergo autophosphorylation, the stoichiometry of which suggested the existence of multiple sites. In the present study we have identified several autophosphorylation sites, including Thr348, Thr353, Ser366 and Ser445, all of which are highly conserved among vertebrate eEF2Ks. We also identified a number of other sites, including Ser78, a known site of phosphorylation, and others, some of which are less well conserved. None of the sites lies in the catalytic domain, but three affect eEF2K activity. Mutation of Ser78, Thr348 and Ser366 to a non-phosphorylatable alanine residue decreased eEF2K activity. Phosphorylation of Thr348 was detected by immunoblotting after transfecting wild-type eEF2K into HEK (human embryonic kidney)-293 cells, but not after transfection with a kinase-inactive construct, confirming that this is indeed a site of autophosphorylation. Thr348 appears to be constitutively autophosphorylated in vitro. Interestingly, other recent data suggest that the corresponding residue in other α-kinases is also autophosphorylated and contributes to the activation of these enzymes [Crawley, Gharaei, Ye, Yang, Raveh, London, Schueler-Furman, Jia and Cote (2011) J. Biol. Chem. 286, 2607–2616]. Ser366 phosphorylation was also detected in intact cells, but was still observed in the kinase-inactive construct, demonstrating that this site is phosphorylated not only autocatalytically but also in trans by other kinases.

Keywords: calmodulin, eukaryotic elongation factor 2 (eEF2), elongation, α-kinase, mass spectrometry (MS), translation

Abbreviations: 2D, two-dimensional; CaM, calmodulin; eEF2, eukaryotic elongation factor 2; eEF2K, eEF2 kinase; ESI, electrospray ionization; GST, glutathione transferase; HEK, human embryonic kidney; LC, liquid chromatography; MHCKA, myosin heavy chain kinase A; TRP, transient receptor potential

INTRODUCTION

eEF2K [eEF2 (eukaryotic elongation factor 2) kinase] is a Ca2+/CaM (calmodulin)-dependent protein kinase, which phosphorylates eEF2 on Thr56 [1,2], decreasing the affinity of eEF2 for the ribosome and thereby inhibiting translation elongation [3,4]. eEF2K contains two main identifiable domains: the catalytic domain lies in the N-terminal half of the sequence and belongs to the small group of so-called α-kinases which comprises six members in mammals [5–8]. Immediately N-terminal to this lies the CaM-binding region [9,10]. The C-terminal part of eEF2K contains several features with predicted α-helical structure and has similarity to the so-called ‘SEL1’ domains that are often involved in protein–protein interactions [11].

The α-kinases are not homologous with the classical eukaryotic protein kinase superfamily. However, structural analysis of the catalytic domain of one α-kinase, the TRP (transient receptor potential) channel TRPM7 (also termed ChaK, for channel kinase) revealed similarity to the fold of other protein kinases [12]. Subsequent studies showed that the kinase domain of another α-kinase, the Dictyostelium discoideum MHCKA (myosin heavy chain kinase A) adopted a similar structure [13]. However, in contrast with members of the classical protein kinase family, little is known about the molecular mechanisms by which the activities of α-kinases are regulated.

eEF2K is subject to control by phosphorylation by several kinases which phosphorylate it in trans at sites in the ‘linker’ region between its N-terminal catalytic and C-terminal ‘SEL1’ domains [14–18]. In the presence of Ca2+ and CaM, eEF2K undergoes autophosphorylation on serine and threonine residues [19].

Autophosphorylation of other protein kinases modulates their activity. In particular, two α-kinases, TRPM6 and TRPM7, undergo extensive autophosphorylation, which enhances their catalytic activity [20–23]. MHCKA also undergoes substantial autophosphorylation, which promotes its activation [24,25]. However, most of the autophosphorylated residues in these proteins lie outside their catalytic domains and, of those that are located within the kinase domain, several are not conserved in eEF2K.

So far, there is no information on the identities of the autophosphorylation sites in eEF2K or their functions. In the present study we have identified the major sites of autophosphorylation in mammalian eEF2K and demonstrate that at least three of them modulate its activity. In particular, Thr348, corresponding to an autophosphorylated threonine residue in MHCKA, is important for its catalytic activity and Ser366, which has been described as being a trans phosphorylation site in vivo [15], are important for the activity of eEF2K in autophosphorylation and against some substrates.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

The MH-1 peptide RKKFGESEKTKTKEFL [9,24] was synthesized by V. Stroobant (Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research, Brussels, Belgium). All routine chemicals and biochemicals were purchased from BDH-Merck and Sigma–Aldrich, except for [γ-32P]ATP, which was purchased from PerkinElmer. Chromatography columns and TLC plates were purchased from GE Healthcare, and the Ultracell centrifugation system was from Amicon. The anti-phosphoSer78 and -phospho-Thr348 antibodies for eEF2K were generated by Eurogentec. The anti-phospho-Ser366 antibody was from Cell Signaling Technology, as was the anti-eEF2K antibody. Anti-FLAG antibody and alkaline phosphatase immobilized on beaded agarose were from Sigma–Aldrich. Alkaline phosphatase and trypsin were from Promega. Solvents and acids for HPLC and LC (liquid chromatography)–MS were from Biosolve.

Molecular biology

The cDNA encoding human eEF2K was cloned into the vector pGEX-6P [14] to allow efficient expression as a GST (glutathione transferase)-fusion protein in Escherichia coli or in PHM vector for expression of FLAG-tagged eEF2K in HEK-293 cells. Point mutations were created using the QuikChange® system (Stratagene).

Protein preparations

Wild-type and mutant human recombinant GST–eEF2K were expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) cells by induction with 0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyranoside for 16 h at 18°C. After induction, bacteria were lysed in 50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.5% Triton X-100, 0.5 mM PMSF, 0.5 mM benzamidine-Cl, 5 nM leupeptin, 5 nM aprotinin, 0.02% Brij35 and 0.02% sodium azide. Bacterial lysates were first purified on DEAE-Sepharose (300–600 mM NaCl gradient) followed by affinity chromatography on glutathione–Sepharose. Purified GST–eEF2K preparations in buffer containing 10% (v/v) glycerol, 50 mM Tris/HCl, pH 7, 150 mM NaCl and 15 mM 2-mercaptoethanol were concentrated by ultrafiltration (Amicon Ultracell system, 100 kDa cut-off). SDS/PAGE analysis of full-length wild-type GST–eEF2K indicated a relative molecular mass of 130 kDa, and the preparation was approximately 90% pure (results not shown).

Dephosphorylation of recombinant eEF2K

Recombinant eEF2K (1 mg of protein/ml) was incubated at room temperature (21°C) with alkaline phosphatase immobilized on agarose beads (approximately 3000 units/20 μl of reaction mixture, where 1 unit corresponds to the amount of enzyme that hydrolyses 1 μmol of p-nitrophenyl phosphate per min at pH 9.8 and 37°C). After 20 min, the mixture was centrifuged at 1000 g for 3 min to remove the immobilized phosphatase. Dephosphorylated eEF2K was then diluted in autophosphorylation buffer.

Autophosphorylation of recombinant eEF2K

Recombinant eEF2K (50 μg/ml) was incubated with Ca2+/CaM (0.2 mM/10 μg/ml) and 0.1 mM [γ-32P]MgATP (1000 c.p.m./pmol) in 40–120 μl of phosphorylation buffer [26] at 30°C. At various times, aliquots (10 μl) were taken for analysis by SDS/PAGE in 10% (w/v) mini-gels. Bands corresponding to eEF2K were cut directly from the gel and dissolved in vials containing 500 μl of 3% (w/w) H2O2 by heating for 2 h at 80°C prior to liquid scintillation counting. Stoichiometries of 32P incorporation were calculated as described previously [27].

Phosphorylation site identification by tandem MS, database searching and analysis

For phosphorylation site identification, wild-type and mutant GST–eEF2K preparations (5 μg) were incubated in a final volume of 40 μl with Ca2+/CaM (0.2 mM/10 μg/ml) and 0.1 mM [γ-32P]MgATP. After 60 min, the reactions were stopped for trypsin digestion and HPLC [28]. Radioactive peaks were concentrated and analysed by nanospray ESI (electrospray ionization)–MS [28]. Alternatively, phosphopeptides were analysed by LC–tandem MS with the LTQ XL equipped with a microflow ESI source interfaced to a Dionex Ultimate Plus Dual gradient pump, a Switchos column switching device and Famos Autosampler (Dionex). Separation was performed on a Hypercarb column (180 μm×15 cm; Thermo Fisher Scientific) equilibrated in solvent A [5% (v/v) acetonitrile and 0.05% formic acid in water] using a gradient from 0 to 70% solvent B [80% (v/v) acetonitrile and 0.05% formic acid in water] over 90 min at a flow rate of 1.5 μl/min. The mass spectrometer was operated in the data-dependent scan routine for the top five ions with an MS scan range of m/z 300–2000. MSA (Multi Stage Activation) was enabled for a phosphate neutral loss of 98, 49 or 32.66 with respect to the precursor m/z [29].

Peak lists were generated using the application spectrum selector in the Proteome Discoverer 1.2 package. From raw files, tandem MS spectra were exported as individual files in.dta format with the following settings: peptide mass range, 400–3500 Da; minimal total ion intensity, 500; and minimal number of fragment ions, 12. The resulting peak lists were searched using Sequest against a home-made protein database containing the human eEF2K sequence (Uniprot O00418) and the GST tag. The following parameters were used: trypsin was selected with proteolytic cleavage only after arginine and lysine residues; the number of internal cleavage sites was set to two; the mass tolerance for precursor and fragment ions was 1.1 Da and 1.0 Da respectively; and the dynamic modifications considered were +15.99 Da for oxidized methionine residues and +79.96 Da for phosphate addition to serine, threonine or tyrosine residues. Peptide matches were filtered using charge-state against cross-correlation scores (xcorr) and phosphorylation sites were validated manually.

2D (two-dimensional) peptide mapping

2D peptide mapping of tryptic peptides from autophosphorylated eEF2K preparations radiolabelled in vitro was carried out as described previously [30], except that detection was by autoradiography and digestion was performed using trypsin in the presence of the reducing agent tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine at a final concentration of 5 mM. For MS analysis, spots were cut from the TLC plates and the cellulose was scraped into tubes for peptide elution with 80 μl of 70% (v/v) acetonitrile and 0.2% formic acid by overnight incubation at room temperature. After centrifugation, the supernatants were concentrated to 10 μl under vacuum for LC–tandem MS analysis as described above.

eEF2K assay

The activity of eEF2K was measured using the ‘MH-1 peptide’ as a substrate. This peptide is based on the sequence around the site in Dictyostelium myosin heavy chain that is phosphorylated by some α-kinases [24] and also by eEF2K [9]. Wild-type and mutant eEF2K preparations (2 μg) were allowed to autophosphorylate in the presence of 0.1 mM non-radioactive MgATP in a final volume of 20 μl of phosphorylation buffer [26] at 25°C rather than 30°C to limit thermal inactivation. After 60 min of incubation, aliquots (2.5 μl) were taken for the eEF2K assay in a final volume of 50 μl containing 0.1 mM MH-1 peptide and 0.3 mM [γ-32P]MgATP (500 c.p.m./pmol) at 30°C. Aliquots (10 μl) were taken at various times up to 10 min of incubation for measurements of initial rates of 32P incorporation [28]. A protein kinase activity of 1 unit corresponds to the amount of enzyme that catalyses the incorporation of 1 nmol/min of 32P under the assay conditions. The activity of eEF2K against eEF2 was measured essentially as described previously [16], except that eEF2K was pre-incubated with non-radioactive MgATP to allow autophosphorylation to occur, prior to addition of eEF2 and [γ-32P]MgATP. Samples were then taken for analysis by SDS/PAGE/autoradiography at the indicated times.

Cell culture and immunoblotting

HEK (human embryonic kidney)-293 cells were cultured and transfected as described previously [31,32]. Immunoblotting was performed as described previously [33], except that detection used a LiCor Odyssey instrument rather than enhanced chemiluminescence.

Protein estimation and statistical analysis

Protein concentrations were determind as described previously [34] using BSA as the standard. The results are expressed as the means±S.E.M. for the indicated number of individual experiments. The statistical significance of the results was assessed by two-way ANOVA followed by a Bonferroni posttest.

RESULTS

Recombinant eEF2K undergoes extensive autophosphorylation

Redpath and Proud [19] showed previously that native eEF2K from rabbit reticulocytes undergoes extensive Ca2+/CaMdependent autophosphorylation. Consistent with this, recombinant human eEF2K expressed in E. coli also underwent autophosphorylation in a strictly Ca2+/CaM-dependent manner (Figure 1A). Autophosphorylation was time-dependent, reaching 8.05±0.86 (means±S.E.M., n=3) mol of phosphate incorporated/mol of eEF2K after incubation at 30°C for 60 min. Prior dephosphorylation of the eEF2K preparation with immobilized alkaline phosphatase resulted in a stoichiometry of autophosphorylation that was slightly less than was observed with the untreated enzyme after 60 min of incubation, perhaps owing to slight protein denaturation during treatment (results not shown). Also, the tryptic phosphopeptide maps of alkaline-phosphatase-treated against untreated wild-type eEF2K obtained after 32P-autophosphorylation were similar in terms of spot distribution and intensity (see Supplementary Figure S1 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/442/bj4420681add.htm). In the absence of Ca2+/CaM, the stoichiometry of eEF2K phosphorylation was only 0.31±0.03 (means±S.E.M., n=3), indicating that autophosphorylation is strongly Ca2+/CaM-dependent. This is similar to our results from previous studies [19].

Figure 1. Recombinant eEF2K undergoes Ca2+/CaM-dependent autophosphorylation.

(A) GST–eEF2K was incubated with [γ-32P]ATP in the presence or absence of Ca2+/CaM as described in the Experimental section. At the indicated times, samples were analysed by SDS/PAGE for measurements of 32P incorporation. The values are means±S.E.M. (n=3). (B) Autophosphorylation was measured as in (A) with the indicated concentrations of wild-type (WT) eEF2K and eEF2K[S78A] mutant.

In a recent parallel study, we expressed fragments of eEF2 containing the N-terminal and kinase domains (eEF2K[1–402]) and the C-terminal region including the SEL1 domains (eEF2K[478–725]) in E. coli [35]. The eEF2K[1–402] fragment itself underwent autophosphorylation and was able to phosphorylate the eEF2K[478–725] fragment [35], although, as expected, the latter did not autophosphorylate itself (results not shown). Taken together, these data indicate that the 1–402 and 478–725 regions each contain one or more autophosphorylation site(s). A kinase-inactive mutant, eEF2K[K170M], did not undergo autophosphorylation, as expected [35]. The rate of autophosphorylation of recombinant eEF2K was independent of the concentration of eEF2K in the assay (Figure 1B), both for wild-type eEF2K and for a selected autophosphorylation site mutant, eEF2K[S78A]. This indicates that autophosphorylation occurs as a cis intramolecular event, since if different eEF2K proteins phosphorylated each other in cis, the rate would show a marked dependence upon concentration. These results are consistent with our previous observations for the native protein from rabbit reticulocytes [19], therefore indicating that cis-autophosphorylation is not merely a consequence of the expression of eEF2K as a GST-fusion protein in E. coli. It is noteworthy that TRPM7, another member of the α-kinase family, was also shown to form dimers (at least for the catalytic domain) [12,36] and another study [37] indicated that recombinant eEF2K is monomeric.

Identification of autophosphorylation sites in eEF2K by tandem MS and 2D peptide mapping

We used two complementary experimental approaches to identify autophosphorylation sites in eEF2K, together with information on its specificity [38]. eEF2K shows a very strong preference for threonine over serine residues when assayed using synthetic peptide substrates (although Redpath and Proud [19] reported stronger autophosphorylation on serine than threonine residues). It also showed a marked preference for peptide substrates with basic residues at the +1 and +3 positions relative to the phosphorylated residue [38] (although the main site for eEF2K in eEF2, Thr56, only contains a basic residue at the +3 position).

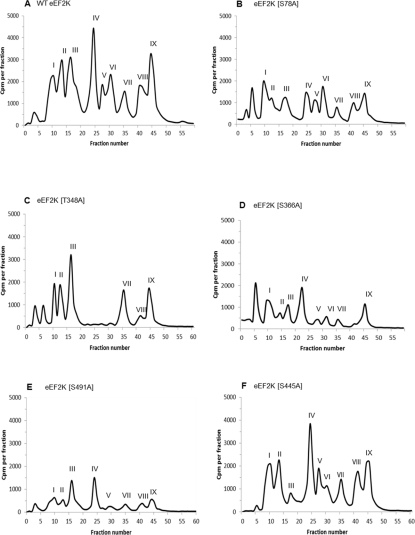

In the first experimental approach, we allowed recombinant eEF2K to undergo autophosphorylation in the presence of Ca2+/CaM and [γ-32P]MgATP. The radiolabelled protein was then precipitated and digested with trypsin; the resulting peptides were then resolved by reverse-phase HPLC. As shown in Figure 2(A), nine peaks of radioactivity were reproducibly observed (denoted ‘I’–‘IX’). Selected fractions from these peaks were then subjected to tandem MS analysis to identify peptides and pinpoint phosphorylation sites. The results are summarized in Table 1. The number of peaks is broadly consistent with the high stoichiometry of autophosphorylation observed, although some peaks might arise from tryptic ‘missed cleavages’ due to the presence of proline residues or to a phosphorylated residue adjacent to the expected cleavage site. For example, peaks V and VIII contain the same phosphorylated residue (Ser366; see Table 1 for details).

Figure 2. HPLC profiles of 32P-autophosphorylated wild-type and mutant eEF2K preparations following trypsin digestion.

Tryptic phosphopeptides from autophosphorylated eEF2K were separated by reverse-phase HPLC as described in the Experimental section. The major radiolabelled peaks are indicated by roman numerals. Phosphorylation sites detected in the peaks are summarized in Table 1 and discussed in the text. HPLC profiles are shown for wild-type (WT) eEF2K (A) and the eEF2K[S78A] (B), eEF2K[T348A] (C), eEF2K[S366A] (D), eEF2K[S491A] (E) and eEF2K[S445A] (F) mutants.

Table 1. MS analysis of peptides from HPLC peaks and TLC spots.

Labelled fractions from autophosphorylated GST–eEF2K wild-type and mutant HPLC runs (Figure 2A) were analysed by nanospray ESI–tandem MS or LC–tandem MS as described in the Experimental section. Also, spots from TLC plates obtained after autophosphorylation and trypsin digestion of wild-type eEF2K, comparable with the separation pattern seen in Figure 3(A), were taken and eluted for LC–tandem MS analysis. Phosphopeptides were identified either by multistage activation or by loss of 98 Da upon collision-induced dissociation. The phosphorylated residue (bold) was further identified by fragmentation in MS3 mode. Residue numbering refers to the sequence of human eEF2K (Uniprot O00418) without the GST tag.

| Peak | Phosphopeptide sequence(s) from HPLC peaks | Phosphorylation sites identified in HPLC peaks | Phosphorylation sites identified in TLC spots* |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | K467YESDEDS474LGSSGR480 | Ser474 | Ser474 in spot E |

| II | Y59YSNLTKS66ER68 and Y59YS61NLTKS66ER68 | Ser66 and Ser61 | Ser61 in spot B |

| III | E434SENSGDSGYPS445EKRGELDDPEPR457 | Ser445 | Ser445 in spots G and l |

| IV | L342LQSAKT348ILRGT353EEK356 and Y69SSSGSPANS78FHFK82 and L342LQSAKT348ILR351 | Thr348, Thr353 and Ser78 | Thr348 in spot A |

| V | T364LS366GSRPPLLR374 | Ser366 | |

| VI | W486NLLNS491SR493 | Ser491 | |

| VII | No identification | ||

| VIII | T364LS366GSRPPLLRPLSENSGDENMSDVTFDSLPSSPSSATPHSQK406 | Ser366 | |

| IX | No identification |

*See Figure 3(B) for the lettering of spots.

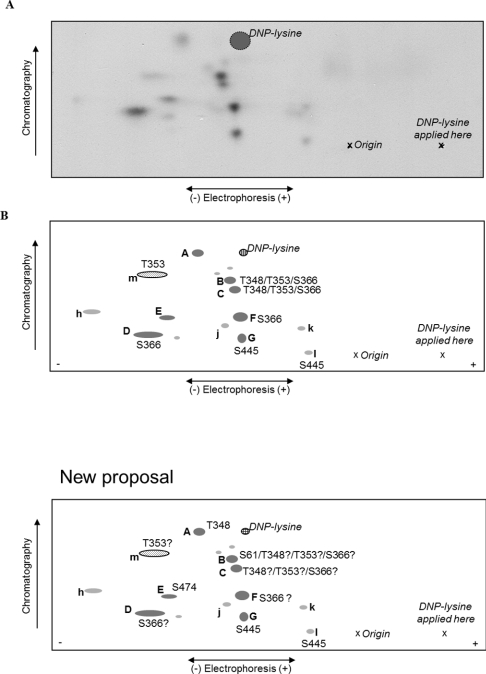

Secondly, tryptic peptides from autophosphorylated radiolabelled eEF2K were also separated by 2D mapping [first dimension, electrophoresis at pH 1.9 (separation by charge/mass ratio); second dimension, chromatography (separation on the basis of hydrophobicity)]. As shown in Figure 3(A), 12–13 different labelled peptides were observed, including seven major species (termed ‘A’–‘G’ in Figure 3A) and several minor ones (termed ‘h’–‘m’). To identify individual sites, spots from the TLC plate obtained from tryptically digested 32P-autophosphorylated wild-type eEF2K were cut out and eluted for tandem MS analysis. Point mutations were then made in eEF2K, on the basis of the tandem MS data and the information about the substrate specificity of eEF2K. The HPLC/MS and TLC peptide mapping experiments were then repeated using the mutant proteins and the results were compared with those for the wild-type eEF2K. For 32P-autophosphorylation studies of wild-type compared with mutants for analysis by HPLC, the experiments were performed using the same stock of radioactive ATP and a correction factor was applied to the results to take account of the radioactive decay of 32P and for variations in protein amounts as judged by overall UV absorbance of peaks, thereby allowing a quantitative evaluation of any differences (Figure 2). The tryptic peptide maps obtained with the 32P-autophosphorylated mutant eEF2Ks compared with the 32P-autophosphorylated wild-type are not quantitative but do provide a qualitative visualization of the pattern of sites phosphorylated (Figure 4). Variations might arise owing to differences in the amounts of material loaded on to the plates, experiments being performed on different days and exposure times for autoradiography.

Figure 3. 2D peptide maps from autophosphorylated wild-type eEF2K.

Wild-type eEF2K was allowed to undergo autophosphorylation in the presence of Ca2+/CaM and then subjected to tryptic digestion. Phosphopeptides were resolved by electrophoresis and chromatography (polarity and directions are indicated). Also shown are the position of the origin, where the peptide samples were applied, “X”, and the final migration position of the DNP–lysine marker (cross-hatched circle). (A) Representative map of wild-type eEF2K; (B) schematic summary of peptides; lettering in capitals for major peptides (shown in dark grey) and in lower case for minor ones (light grey). The peptide shown by the dotted oval (‘m’) was only observed on maps from the eEF2K[T348A] mutant.

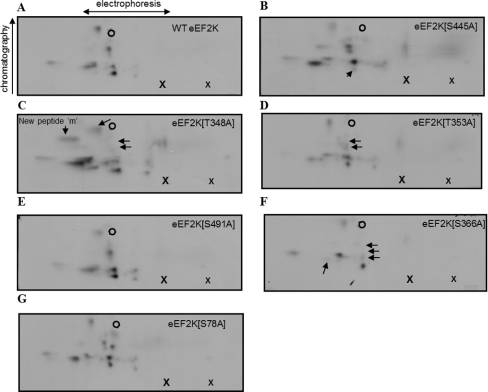

Figure 4. 2D peptide maps from autophosphorylated wild-type eEF2K and mutants.

Wild-type or mutant eEF2K was allowed to undergo autophosphorylation in the presence of Ca2+/CaM and then subjected to tryptic digestion. Phosphopeptides were resolved by electrophoresis and chromatography (polarity and directions are indicated). The positions where the sample (larger ‘X’) and the DNP–lysine (smaller “x”) were applied, and the final migration position of the DNP–lysine marker (open circle) are also shown. The maps are derived from wild-type eEF2K (A), eEF2K[S445A] (B), eEF2K[T348A] (C), eEF2K[T353A] (D), eEF2K[S491A] (E), eEF2K[S366A] (F) and eEF2K[S78A] (G). The arrows highlight spots that were lost or that decreased in intensity compared with the map from wild-type eEF2K. All peptide maps were run at least twice to verify their reproducibility, and similar levels of radioactivity were applied.

Peak I from the HPLC profile obtained with autophosphorylated wild-type eEF2K (Figure 2A) corresponded to a peptide in which Ser474 was the phosphorylated residue identified by MS (Table 1). The peptide contains a N-terminal lysine residue resulting from a missed cleavage at an Arg-Lys sequence and a basic residue only at position +6, which makes it a poor candidate for being a bona fide autophosphorylation site on the basis of previous results [38]. Nevertheless, this site is perfectly conserved among vertebrate eEF2Ks and is located in the ‘linker’ region. This site has already been identified in vivo from EGF-stimulated HeLa cells, but showed no temporal change upon stimulation [39]. Peak I was lost in the HPLC profile of the eEF2K[S474A] mutant, whereas no other peaks changed (results not shown). Also, there was no obvious change in the pattern of peptides on the 2D map from the eEF2K[S474A] mutant (results not shown), suggesting that this is a relatively minor site.

Peak II contained two versions of the same peptide, either singly phosphorylated on Ser66 or doubly phosphorylated on Ser61 and Ser66. A smaller peptide containing only phosphorylated Ser61 and eluting around fraction 6 was sometimes observed in the HPLC profile (Figures 2B, 2C and 2D). Ser61 is not conserved in mammalian eEF2K sequences, and Ser66 is replaced by a threonine residue in some species. Perhaps more importantly, although the human sequence contains an arginine residue C-terminal to Ser66, most mammalian sequences do not. These observations suggest that neither site is a conserved autophosphorylation site, and we therefore did not study Ser61 or Ser66 further in the present study.

Peak III contained a very long (23 amino acids) tryptic peptide with two internal missed cleavages at a consecutive Lys-Arg sequence, and in which Ser445 was the phosphorylated residue. All vertebrate eEF2K sequences contain a serine residue at this position, and in all cases it is followed by an arginine residue at position +3 (and a lysine residue at +2). In view of the highly conserved nature of this site, we created an eEF2K[S445A] mutant. The major phosphopeptide species ‘G’ and the minor peptide ‘l’ were both absent from 2D maps derived from this mutant, thus demonstrating that Ser445 is indeed a significant site of autophosphorylation in eEF2K (Figure 4B; compare with wild-type eEF2K in Figures 3A and 4A). HPLC analysis of the tryptic peptides from the eEF2K[S445A] mutant revealed that the labelling of peak III was abrogated, confirming that this peak does indeed correspond to this site (compare Figure 2A with 2F). Moreover, Ser445 was identified by MS in spots ‘G’ and ‘l’ after peptide elution from the TLC plate of 32P-autophosphorylated wild-type eEF2K (Table 1).

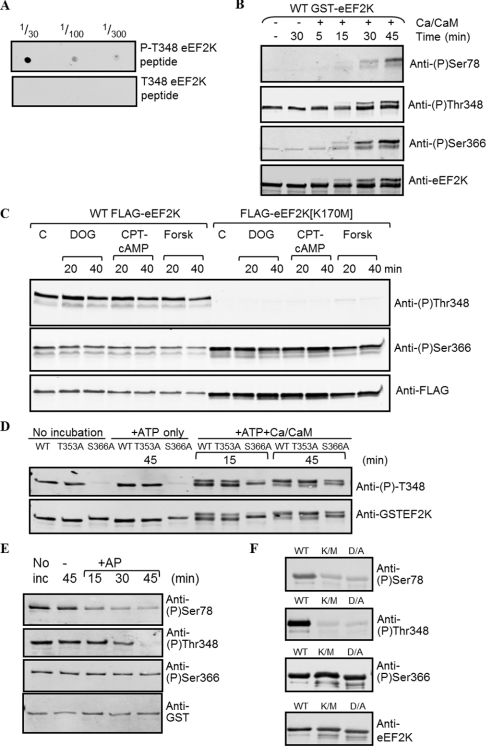

Peak IV was the largest single radioactive peak in the profile and contained a mixture of three different phosphopeptides bearing three phosphorylation sites, namely Thr348, Thr353 and Ser78. Thr348 was seen in a singly phosphorylated peptide and, along with Thr353, in a doubly phosphorylated peptide due to a missed cleavage (Table 1). We have previously identified Ser78 as a site of phosphorylation in eEF2K and made a phosphospecific antibody for this site [33]. To ascertain whether this residue is indeed a site of autophosphorylation, we incubated recombinant eEF2K with non-radioactive MgATP for different times, and analysed the reaction products by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotting with the anti-phospho-Ser78 antibody. As shown in Figure 5(B), Ser78 does become phosphorylated during autophosphorylation, but only at later times (roughly corresponding to the times when a mobility shift is observed). Since the results in Figure 5(B) show that Ser78 undergoes autophosphorylation, we also ran 2D maps from the eEF2K[S78A] mutant (Figure 4G). Although tryptic cleavage should generate a readily mobile peptide containing this site (YSSSGSPANpSFHFK), no obvious difference was seen relative to the maps from wild-type eEF2K, indicating that this is only a minor site of autophosphorylation. This was further confirmed in the HPLC profile of the tryptically digested autophosphorylated eEF2K[S78A] mutant (Figure 2B), which revealed that no peaks were lost, but rather the extent of phosphorylation of all peaks decreased, probably resulting from a decrease in kinase activity (see below). Ser78 is also conserved among vertebrate eEF2K sequences.

Figure 5. Use of phosphospecific antibodies to study the autophosphorylation of eEF2K in vitro and in intact cells.

(A) Dot blot to establish whether the anti-phospho-Thr348 antibody is truly phosphospecific. A total of 1 μl of the indicated dilutions of the phosphorylated and non-phosphorylated versions of the corresponding peptide (10 mg/ml) were applied to the membrane, which was developed as for Western blot analysis. (B) Recombinant GST–eEF2K expressed in E. coli was incubated without or with Ca2+/CaM, as indicated, and non-radioactive ATP for the times shown. Samples were then analysed by SDS/PAGE followed by Western blot analysis with the indicated antibodies specific for phospho (P)-Ser78, phospho-Ser366 or phospho-Thr348, and anti-eEF2K antibody as a loading control. (C) Results for the phosphorylation of Thr348 and Ser366 in vivo. HEK-293 cells were transfected with a vector encoding either wild-type (WT) eEF2K or the kinase-defective eEF2K[K170M] mutant. Cells were treated for the indicated times with 2-deoxyglucose (DOG; 10 mM; after transfer to medium containing 5 mM glucose), chlorophenylthio-cAMP (CPT-cAMP; 0.5 mM) or forskolin (Forsk; 10 μM); the latter two were used in the presence of isobutylmethylxanthine (1 mM). Cell lysates were analysed by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. C, control (untreated) cells. (D) Recombinant GST–eEF2K was incubated, where noted, with non-radioactive MgATP and, in some cases, Ca2+/CaM for the indicated times. Samples were then denatured and analysed by SDS/PAGE and Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. (E) Recombinant GST–eEF2K was either analysed directly (‘No inc’) or incubated with alkaline phosphatase (+AP) for the times shown. Samples were analysed by SDS/PAGE and Western blotting using the indicated antibodies. (F) Wild-type eEF2K or two kinase-deficient mutants (K/M, eEF2K[K170M]; D/A, eEF2K[D274A]) were analysed by SDS/PAGE and Western blotting using the indicated antibodies.

Peak IV also contained peptides phosphorylated on Thr348 and/or Thr353. Thr348 is conserved in almost all known eEF2K sequences [in Loa loa (filarial nematode) it is replaced by a serine residue], whereas other mammalian eEF2K sequences, and some other species, contain a threonine residue at the position corresponding to Thr353 in human eEF2K (Table 2). We therefore also created eEF2K[T348A] and eEF2K[T353A] mutants. 2D phosphopeptide mapping of the eEF2K[T348A] mutant showed that the intensities of spots ‘A’, ‘B’ and ‘C’ decreased (Figure 4C), whereas a new spot (‘m’) appeared (indicated in Figure 4C). After eluting peptides from spots cut from the TLC plate obtained after 32P-autophosphorylation of wild-type eEF2K, we were able to identify Thr348 in spot ‘A’ and Ser61 in spot ‘B’ by MS (Table 1). However, using MS analysis, we were unable to identify any sites in phosphopeptides eluted from spots ‘C’ and ‘m’. The HPLC profile from the autophosphorylated trypsin-digested eEF2K[T348A] mutant (Figure 2C) was very different from the profile seen with wild-type eEF2K, in that peaks IV, V and VI were all absent. Taken together, the results indicate that mutation of Thr348 to an alanine residue also affects the phosphorylation of other less prominent sites (Ser61, Ser78 and Ser491). This probably reflects the large decrease in activity observed for the eEF2K[T348A] mutant (see below). Also, because Thr348 immediately follows a potential tryptic cleavage site (Lys347), the tryptic cleavage patterns of autophosphorylated wild-type and T348A mutant could be different. It is well known that the presence of a phosphorylated residue on the C-terminal side of a trypsin cleavage site can prevent tryptic cleavage [40]. This could explain the generation of peptides containing more than one phosphorylated residue, complicating the interpretation of the HPLC and 2D mapping data. Taken together, the results indicate that the Thr348 site is present in spot ‘A’ and possibly also in spots ‘B’ and ‘C’ (Figure 3B). Thus Thr348, a highly conserved residue, is a major site of autophosphorylation, whose mutation to alanine dramatically affects autophosphorylation at several other sites.

Table 2. Conservation of autophosphorylation sites in eEF2K.

+, conserved; (+), local conservation weak, but residue probably conserved; −, local conservation strong, site not conserved; single letter code is used to indicate conservative replacements.

| Species | Ser61 | Ser66 | Ser78 | Thr348 | Thr353 | Ser366 | Ser445 | Ser474 | Ser491 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Mouse | + | T | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Rat | − | T | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Cow | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Lizard (Anolis carolinensis) | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | − |

| Zebra finch | − | T | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Zebrafish | − | T | + | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| Acorn worm (Saccoglossus kowalevskii) | − | − | − | + | S | − | T | − | − |

| Strongylocentrotus purpuratus | − | − | − | + | + | − | − | − | − |

| Aplysia californica | − | − | − | + | − | − | − | + | − |

| Ascaris suum | − | − | − | (+) | S | − | − | (+) | − |

| Caenorhabditis elegans | − | − | − | (+) | − | − | − | (+) | − |

| Loa loa | − | − | − | S | S | − | − | − | − |

| Caenorhabditis briggsae | − | − | − | (+) | − | − | − | (+) | − |

To study the phosphorylation of Thr348, we generated a phosphospecific antibody which showed clear specificity for the phosphorylated against the non-phosphorylated peptide containing Thr348 (Figure 5A). As shown in Figure 5(B), Thr348 phosphorylation in recombinant eEF2K was already detected at zero time, and so Thr348 phosphorylation probably occurs extremely rapidly or during expression in E. coli.

2D mapping analysis of the autophosphorylated eEF2K[T353A] mutant indicated that some of the peptides that were absent from the maps for eEF2K[T348A] were also absent from the maps of this mutant, i.e. peptides ‘B’ and ‘C’ (Figure 4D, compare with Figure 3B). In contrast, for the autophosphorylated eEF2K[T353A] mutant, peptide ‘m’ did not appear on the map. Therefore the results suggest that the Thr353 site would be present in peptides migrating in spots ‘B’, ‘C’ and ‘m’ (Figure 3B). The HPLC profile of the tryptically digested autophosphorylated eEF2K[T353A] mutant showed no striking differences compared with the profile seen for autophosphorylated wild-type eEF2K (results not shown), consistent with the fact that its mutation to alanine did not affect eEF2K activity (see below).

In peak V, we detected phospho-Ser366 in a peptide resulting from tryptic cleavage at Arg-Pro. This might seem surprising given that trypsin should not cleave next to proline. As such, this residue would be expected to be located in a very long tryptic peptide (residues 364–406), which was indeed found in peak VIII. However, trypsin was recently reported to cleave Arg-Pro or Lys-Pro bonds more frequently than was previously thought [41]. The Ser366 site is well conserved and already known to be phosphorylated in vitro, and probably in vivo, by p70 and p90 ribosomal protein S6 kinases [15]. The availability of a phosphospecific antibody for this site allowed us to test whether it is indeed autophosphorylated. Immunoblotting revealed that Ser366 does become phosphorylated when eEF2K is incubated with Ca2+/CaM (Figure 5B). Therefore we studied the autophosphorylation of the eEF2K[S366A] mutant further by peptide mapping. This revealed that a number of peptides were absent from the maps compared with wild-type eEF2K, specifically spots ‘B’, ‘C’, ‘D’ and ‘F’, and the minor species ‘k’ and ‘l’ (Figure 4F; compare with Figure 3B). The fact that mutation of this residue affects multiple peptides may again be a consequence of the dramatic effect of mutation of this residue to decrease kinase activity. The HPLC profile of the tryptically digested autophosphorylated eEF2K[S366A] mutant (Figure 2D) revealed that peaks V and VIII were indeed lost compared with the profile from autophosphorylated wild-type eEF2K (Figure 2A), confirming the identification of this site. Also, all other peaks were notably decreased in the HPLC profile of this mutant owing to a substantial decrease in the eEF2K activity (see below).

Peak VI contained a peptide in which Ser491 was the sole phosphorylation site. This residue is not well conserved in mammals, being replaced, for example, by a proline residue in rodents. Mutation of this residue to alanine had no clear effect on the 2D maps (Figure 4E), but did cause the loss of peak VI in the HPLC trace and a general decrease in overall labelling (Figure 2E; compare with Figure 6B) compared with the 32P-autophosphorylation labelling profile of wild-type eEF2K (Figure 2A).

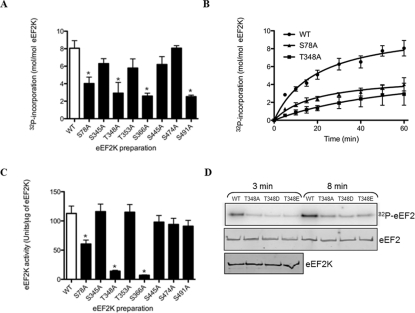

Figure 6. Autophosphorylation of wild-type and mutant eEF2K preparations and effects on eEF2K activity.

(A) The histogram shows stoichiometries of autophosphorylation of the wild-type (WT) and mutant eEF2K preparations calculated after 60 min of incubation and, in (B), a time-course of phosphorylation of wild-type against the selected mutants is shown. The results are means±S.E.M., n=3. (C) eEF2K wild-type and mutant preparations were allowed to autophosphorylate in the presence of non-radioactive ATP as described in the Experimental section. After 60 min of incubation, aliquots were taken for eEF2K assay with MH-1 as substrate. Activities calculated from initial rates of 32P-incorporation are shown in the histogram. Values are means±S.E.M., n=3 and *P<0.001 compared with the wild-type. (D) The wild-type and indicated mutant eEF2K preparations were incubated with [γ-32P]ATP for autophosphorylation as described in the Experimental section. At the indicated times, samples were taken for SDS/PAGE and autoradiography. The bottom panel shows a Western blot for eEF2K to confirm that equal amounts of wild-type and mutant enzyme were used.

We also generated mutants at several other potential autophosphorylation sites chosen either because they were sometimes seen in the tandem MS analysis (Ser345 and Ser500) or because an arginine residue was present at the +3 position (Ser477 and Ser627). However, the maps obtained after tryptic digestion of autophosphorylated eEF2K[S345A], eEF2K[S477A], eEF2K[S500A] and eEF2K[S627A] mutants were indistinguishable from those obtained with wild-type eEF2K (results not shown), indicating that they are not significant sites of autophosphorylation (or do not actually undergo autophosphorylation at all).

Ser359 is a known site of phosphorylation in eEF2K (for p38 MAPKδ (mitogen-activated protein kinase δ)/SAPK4 (stress-activated protein kinase 4) and Cdc2 (cell division cycle 2) [14,16]) and is followed by arginine residues at positions +2 and +4, suggesting that it might be an autophosphorylation site. We therefore used the relevant phosphospecific antibody to ascertain whether it is a site of autophosphorylation, but no signal was observed when eEF2K was incubated with Ca2+/CaM, even after 45 min of incubation (results not shown). Ser359 does not therefore appear to be a significant site of autophosphorylation in eEF2K.

Stoichiometry of in vitro autophosphorylation and effects on eEF2K activity

The time course of autophosphorylation of each mutant eEF2K preparation was compared with that of the wild-type. Four eEF2K mutant preparations displayed a similar stoichiometry of 32P-incorporation compared with the wild-type, measured after 60 min of incubation (Figure 6A): {eEF2K[WT], 8.05±0.86 mol of phosphate incorporated/mol of protein; eEF2K[S345A], 6.3±0.71 mol of phosphate incorporated/mol of protein; eEF2K[T353A], 5.8±0.67 mol of phosphate incorporated/mol of protein; eEF2K[S445A], 6.2±0.68 mol of phosphate incorporated/mol of protein; and eEF2K[S474A], 8.1±0.87 mol of phosphate incorporated/mol of protein (means±S.E.M., n=3)}. These stoichiometries are in general agreement with the extent of labelling seen in the HPLC profiles of the mutants compared with wild-type eEF2K (results not shown). The decreases in stoichiometry observed for eEF2K[S345A], eEF2K[T353A] and eEF2K[S445A] (Figure 6A) were not statistically significant and probably reflect the loss of 32P incorporation by mutation of the site.

Mutation of Ser78 to alanine significantly decreased the stoichiometry of 32P-incorporation by approximately 50% compared with the wild-type: the incorporation of 32P into the eEF2K[S78A] mutant reached 4.01±0.41 mol of phosphate incorporated/mol of protein (means±S.E.M., n=3) (Figures 6A and 6B). The HPLC profile of the eEF2K[S78A] mutant was similar to that of the wild-type, except that the overall extent of labelling was reduced (Figure 2B), suggesting that this mutation decreases kinase activity. Since Ser78 is located close to the CaM-binding domain ([9], Figure 7), the observed decrease could be due to an effect on CaM-induced activation. Three other mutations each significantly decreased the stoichiometry of autophosphorylation by approximately 60% compared with the wild-type (Figures 6A and 6B): eEF2K[T348A], 2.9±0.34 mol of phosphate incorporated/mol of protein; eEF2K[S366A], 2.6±0.3 mol of phosphate incorporated/mol of protein; and eEF2K[S491A], 2.5±0.27 mol of phosphate incorporated/mol of protein (means±S.E.M., n=3).

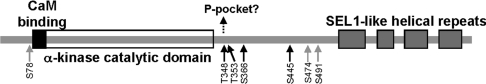

Figure 7. Location of autophosphorylation sites within the domain structure of eEF2K.

The layout of the eEF2K polypeptide is depicted schematically (and only roughly to scale). The major sites of autophosphorylation identified in the present study are indicated (black arrows), with minor ones shown by grey arrows. The dotted arrow indicates that phosphorylated Thr348 may dock with the phosphate (P-) pocket in the C-terminal lobe of the catalytic domain to promote eEF2K activity, similar to Thr825 in MHCKA [25]. See the Discussion for further information.

To assess the effects of autophosphorylation on eEF2K activity towards the MH-1 substrate peptide, eEF2K wild-type and mutant preparations were pre-incubated for 60 min with MgATP at 21°C prior to assaying eEF2K activity. The thermal stability of the proteins was checked by measuring eEF2K activity towards MH-1 before and after incubation. The eEF2K wild-type and selected eEF2K[S78A] mutant preparations lost 10–30% of eEF2K activity during pre-incubation (results not shown). The activity of eEF2K[S78A] towards MH-1 was decreased by approximately 50% compared with the activity of eEF2K wild-type (Figure 6C). Mutation of Thr348 and Ser366 to alanine had more drastic effects, reducing eEF2K activity of the preparations by approximately 90 and 95% compared with the wild-type protein respectively (Figure 6C). To test whether mutation to negatively charged residues might mimic autophosphorylation at this position and perhaps create a more active form of eEF2K, we created eEF2K[T348D] and eEF2K[T348E] mutants and studied their activities. These two mutants, along with the eEF2K[T348A] mutant, phosphorylated purified eEF2 poorly compared with wild-type eEF2K, indicating that in this case negatively charged residues do not mimic phosphothreonine at this position (Figure 6D).

Autophosphorylation of eEF2K studied in intact cells using the anti-phospho-Thr348 antibody

It was clearly important to study the phosphorylation of Thr348 in eEF2K in intact cells. To do this, HEK-293 cells were transfected with a vector encoding FLAG-tagged eEF2K and 24 h later were treated with agents known to activate eEF2K. Treating cells with 2-deoxyglucose depletes ATP levels, and activates the AMP-activated protein kinase, which in turn positively regulates eEF2K [18,42], whereas chlorophenylthio-cAMP and forskolin both cause the activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase, another positive regulator of eEF2K [43,44]. Western blot analysis of lysates derived from the transfected cells were probed with phospho-Thr348 and FLAG antisera. As shown in Figure 5(C), the level of phosphorylation of Thr348 is essentially the same in all cases for wild-type eEF2K, indicating that it is phosphorylated under basal conditions.

We also made use of a mutant of eEF2K in which Lys170 is mutated to methionine: this decreases catalytic activity by >99% [35]. The level of phosphorylation of Thr348 was greatly decreased for this mutant, being almost undetectable under most conditions (Figure 5C). Importantly, this demonstrates that phosphorylation of eEF2K at Thr348 is autocatalytic. We also tested the state of phosphorylation of Ser366 using a phosphospecific antibody. As shown in Figure 5(C), this site is still heavily phosphorylated in the eEF2K[K170M] mutant, indicating that in vivo it is also phosphorylated by other kinases, such as p70 and p90 ribosomal protein S6 kinases [15].

Additional evidence that Ser78 and Thr348 are autophosphorylation sites

We tested the abilities of selected eEF2K mutants to undergo phosphorylation at Thr348 in vitro. Mutation of Thr353 to alanine did not affect the phosphorylation of Thr348 (Figure 5D). In contrast, the eEF2K[S366A] mutant showed greatly reduced basal phosphorylation of Thr348 (Figure 5D), although phosphorylation of this site did increase over time when this variant protein was incubated with MgATP and Ca2+/CaM. The reduced autophosphorylation of this mutant is in line with its decreased activity shown in Figure 6(C).

To assess whether the signals observed with the phosphospecific antisera truly reflected phosphorylation of the corresponding residues, recombinant eEF2K produced by E. coli was treated with alkaline phosphatase for various times prior to analysis by Western blot. Alkaline phosphatase treatment decreased the signal for phospho-Ser78 and phospho-Thr348, but not the signal for phospho-Ser366 (Figure 5E). These results indicate that Ser78 and Thr348 are already phosphorylated but that the signal for Ser366 may be due to reactivity of the antibody with non-phosphorylated eEF2K. To study this further, we also analysed two mutants of eEF2K in which catalytic activity is greatly diminished (by >99%) by mutation of Lys170 to methionine or Asp274 to alanine [35]. The signals for phospho-Ser78 and phospho-Thr348, but not for phospho-Ser366, were markedly decreased for both mutant proteins (Figure 5F). This confirms that the phosphate at Ser78 and Thr348 is introduced by autophosphorylation, and is consistent with the phospho-Ser366 antibody detecting the unphosphorylated residue, although other explanations are possible.

DISCUSSION

Our results of the present study confirm and expand earlier findings [19] that eEF2K undergoes extensive Ca2+/CaM-dependent autophosphorylation. Importantly, we now identify nine sites of autophosphorylation in human eEF2K, consistent with the observed stoichiometry of approximately 8 mol of phosphate/mol of enzyme and show that at least three of them affect phosphorylation of the MH-1 substrate peptide.

Interestingly, our results reveal for the first time that eEF2K can use serine as well as threonine as a phosphoacceptor, at least within the eEF2K polypeptide itself, whereas an earlier study which employed peptides as substrates found that eEF2K exhibited an overwhelming preference for phosphorylation of threonine residues in that context [38]. In different species, the physiological substrate eEF2 always has a threonine residue at the position corresponding to Thr56 in human eEF2, never a serine residue. That study also indicated that eEF2K strongly preferred to phosphorylate residues with basic amino acids at the +1 and +3 positions. Consistent with this, six of the autophosphorylation sites that we have identified in the present study have a basic residue in close proximity to the C-terminal side [arginine residues at +3 (Thr348, Ser366 and Ser445) or +2 (Ser491 and Ser66, a less prominent site), or lysine at +3 (Thr353)]; Ser61 and Ser78 also have a lysine residue at +4. Finally, for Ser474, the basic residue is located at +6. Autophosphorylation does not require a basic residue at +1 (none of the autophosphorylation sites we have identified has a basic residue at this position, and neither does Thr56 in eEF2 itself).

Several of the major phosphorylation sites are conserved among vertebrate eEF2K sequences (Table 2), but only one, Thr348, a critical site for eEF2K activity, is generally conserved in other phyla as well (e.g. arthropods, echinoderms, molluscs, cnidaria and nematodes; it is replaced by another phosphoacceptor, serine, in some nematodes).

Mutation of Ser78, Thr348, Ser366 or Ser491 to an alanine residue reduced the stoichiometry of autophosphorylation (Figures 6A and 6B), but activity measured towards the MH-1 peptide was most drastically reduced by mutation of Thr348 or Ser366. However, this may be the consequence of different mechanisms as the HPLC profiles and activity measurements differ considerably for these three mutants. One must also bear in mind that mutations may alter the folding of eEF2K and exert effects unrelated to the role of given residues as autophosphorylation sites. The T348A mutation had a very marked impact on autophosphorylation and activity against both the MH-1 peptide and eEF2. Thus Thr348 may be considered as a master site whose phosphorylation is important for phosphorylation at the other sites. It should be noted that Thr348 is the autophosphorylation site that is closest to the catalytic domain and is also the most widely conserved one among known eEF2K sequences from species as divergent as nematodes and sea slugs (see further discussion of this site below).

Mutation of eEF2K Ser366 to alanine decreased the extent of overall 32P-incorporation (Figures 2A and 2D). This mutant also showed a substantial decrease in activity towards the MH-1 peptide similar to that observed for the eEF2K[T348A] mutant. Thus Ser366 is important for kinase activity against the MH-1 peptide, although it does not apparently affect activity against eEF2 itself [15].

Although the eEF2K[T348A] (and eEF2K[S366A]) mutant proteins showed drastically reduced activities towards MH-1 (Figure 6C), they still underwent autophosphorylation (Figure 6A), showing an important difference between autokinase activity and the ability to phosphorylate substrates in trans. The results for the activity of the S366A mutant against the MH-1 peptide are surprising given that earlier work found that this mutant did not show a marked change in activity against eEF2 itself [15]; this may reflect differences in the requirements for phosphorylation of the MH-1 peptide and eEF2, which are clearly distinct [35]. The eEF2K[S491A] variant showed a similar behaviour to that of eEF2K[S366A] as regards its impact on the level of autophosphorylation and the HPLC profile, but it is clearly different in terms of catalytic activity towards MH-1, which was only slightly altered. This again indicates that the autophosphorylation and transphosphorylation processes against different substrates, although sharing common regulatory mechanisms, also have specific requirements.

We have shown in a recent study that, although fragments lacking the C-terminal part of eEF2K cannot phosphorylate eEF2 or the MH-1 peptide, addition of the eEF2K[478–725] fragment restores their ability to do so, and we suggest that the C-terminal SEL1-containing region helps to recruit substrates for phosphorylation by the kinase domain [35]. The sequence connecting the two domains contains a number of phosphorylation sites for kinases that regulate the activity of eEF2K (e.g. Ser359 [16], Ser366 [15], Ser396 [17] and Ser398 [18]). It is possible that phosphorylation of these sites affects eEF2K activity by altering the conformation of the ‘linker’ region and thereby the efficiency of the ‘coupling’ between the C-terminal and kinase domains of eEF2K. In this context, it is notable that mutation of Ser366 markedly alters activity against the MH-1 peptide.

Interestingly, other α-kinases also undergo autophosphorylation. TRPM6 and TRPM7 contain many sites of autophosphorylation [20] and MHCKA also undergoes autophosphorylation [24,25]. Where known, many of these autophosphorylation sites lie in regions that are not homologous with eEF2K; of those that do lie in their homologous kinase domains, only one corresponds to a potential phosphorylation site in eEF2K (Ser135), and we did not find this as an autophosphorylation site, even though it should yield a readily detectable tryptic phosphopeptide. Crawley et al. [45] identified several sites of autophosphorylation in MHCKA. Our finding in the present study that Thr348 is a major site of autophosphorylation in eEF2K is precisely in accord with their data and predictions [45]. These authors showed that Thr825 is constitutively autophosphorylated in MHCKA. This residue, the equivalent of Thr348 in eEF2K, lies just C-terminal to the catalytic domain. On the basis of the crystal structure of its catalytic domain together with biochemical data, they proposed that phosphorylated Thr825 docks with a phosphate-binding pocket in the C-terminal lobe, and that this interaction stimulates the catalytic activity of MHCKA. They suggest that a similar mechanism may operate in other α-kinases [45]. The results of the present study are entirely consistent with this; Thr348, which we have identified as a major site of autophosphorylation, lies close to, and on the C-terminal side of, the catalytic domain, and, in common with Thr825 in MHCKA, is followed by a hydrophobic residue (isoleucine in many vertebrate eEF2Ks; replaced by other branched-chain residues in some other species). Both the phosphate-binding pocket and the proposed ‘partner’ for the adjacent hydrophobic residue are conserved among MHCKs and eEF2Ks. It thus appears likely that autophosphorylation promotes the activity of these enzymes in similar ways, through the interaction of a constitutively phosphorylated threonine residue with a conserved phosphate-binding region. Our observation that replacement of Thr348 with either a glutamate or aspartate residue generated a catalytically inactive enzyme is in accordance with the data of Crawley et al. [45], who found that adding phosphate or phosphothreonine, but not glutamate or aspartate, could activate a truncated version of MHCKA that lacks the region containing Thr825. It is interesting that Thr348 is basally phosphorylated in human cells; this probably ensures that eEF2K is already ‘primed’ and poised to phosphorylate eEF2.

A surprising finding from our studies is that eEF2K undergoes autophosphorylation on two sites, which inhibit its activity, Ser78 and Ser366; both sites are phosphorylated in vivo in response to, e.g., insulin in an mTORC1 (mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1)-dependent manner [15,33]. An analogous situation is found for the catalytic α-/β-subunits of AMP-activated protein kinase, which autophosphorylate on Ser485/Ser491 [28]. However, protein kinase B also phosphorylates this site, thereby decreasing the activation of AMP-activated protein kinase by LKB1 [46]. Phosphorylation of Ser78 impairs the interaction of eEF2K with CaM [33], whereas phosphorylation of Ser366 impairs its activation by Ca2+ ions [15]. Both of these sites are also autophosphorylated, and, in the case of Ser78, apparently only at a low level in vitro or in vivo (results not shown). In contrast, the 2D peptide maps show that Ser366 is a major site of autophosphorylation. It is possible that its slow phosphorylation serves to turn off eEF2K after its activation in response to cellular stresses, by desensitizing eEF2K to activation by Ca2+/CaM, thereby allowing translation elongation to resume.

In conclusion, the results from the present study reveal that Thr348, and presumably its autophosphorylation, are critical for the ability of eEF2K to phosphorylate substrates in trans, having similar effects on the phosphorylation of the MH-1 substrate peptide. These results suggest that autophosphorylation of eEF2K may be a prerequisite for the activity of eEF2K, in line with other α-kinases that have been studied.

Online data

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION

Sébastien Pyr Dit Ruys performed 32P-labelling, measured stoichiometries and eEF2K activities. Xuemin Wang prepared mutants and analysed eEF2K autophosphorylation by 2D TLC with assistance from Ewan Smith and Sébastien Pyr Dit Ruys. Xuemin Wang also carried out experiments on the expression of eEF2K in HEK-293 cells. Gaëtan Herinckx performed 32P-labelling and ran the HPLC profiles of the eEF2K preparations. Nusrat Hussain screened the eEF2K preparations for eEF2K activity and measured autophosphorylation rates. Didier Vertommen carried out phosphorylation site identification by MS. Mark Rider, Christopher Proud, Sébastien Pyr Dit Ruys, Xuemin Wang and Didier Vertommen participated in the conception and design of the experiments, the analysis and interpretation of the results, and drafting the paper.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Farnaz Taghizadeh (University of British Colombia) and Usha Agarwala (University of Southampton) for excellent technical support, and Professor L. Hue for helpful discussions.

FUNDING

This work was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Wellcome Trust [grant number WT086688/Z/08/Z] and the Royal Society (to C.G.P.). S.P.D.R. was supported by the Interuniversity Poles of Attraction Belgian Science Policy (P6/28). D.V. is a Chercheur Scientifique Logistique of the National Fund for Scientific Research (Belgium). The work was also funded by the Interuniversity Poles of Attraction Belgian Science Policy (P6/28), by the Directorate General Higher Education and Scientific Research, French Community of Belgium and by the Fund for Medical Scientific Research (Belgium).

References

- 1.Ovchinnikov L. P., Motuz L. P., Natapov P. G., Averbuch L. J., Wettenhall R. E., Szyszka R., Kramer G., Hardesty B. Three phosphorylation sites in elongation factor 2. FEBS Lett. 1990;275:209–212. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)81473-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Price N. T., Redpath N. T., Severinov K. V., Campbell D. G., Russell J. M., Proud C. G. Identification of the phosphorylation sites in elongation factor-2 from rabbit reticulocytes. FEBS Lett. 1991;282:253–258. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80489-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carlberg U., Nilsson A., Nygard O. Functional properties of phosphorylated elongation factor 2. Eur. J. Biochem. 1990;191:639–645. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ryazanov A. G., Davydova E. K. Mechanism of elongation factor 2 (EF-2) inactivation upon phosphorylation. Phosphorylated EF-2 is unable to catalyze translocation. FEBS Lett. 1989;251:187–190. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(89)81452-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drennan D., Ryazanov A. G. α-Kinases: analysis of the family and comparison with conventional protein kinases. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2004;85:1–32. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6107(03)00060-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ryazanov A. G., Pavur K. S., Dorovkov M. V. Alpha kinases: a new class of protein kinases with a novel catalytic domain. Curr. Biol. 1999;9:R43–R45. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80006-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nairn A. C., Bhagat B., Palfrey H. C. Identification of calmodulin-dependent protein kinase III and its major Mr 100,000 substrate in mammalian tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1985;82:7939–7943. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.7939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryazanov A. G. Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent phosphorylation of elongation factor 2. FEBS Lett. 1987;214:331–334. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(87)80081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pavur K. S., Petrov A. N., Ryazanov A. G. Mapping the functional domains of elongation factor-2 kinase. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12216–12224. doi: 10.1021/bi0007270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diggle T. A., Seehra C. K., Hase S., Redpath N. T. Analysis of the domain structure of elongation factor-2 kinase by mutagenesis. FEBS Lett. 1999;457:189–192. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)01034-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mittl P. R., Schneider-Brachert W. Sel1-like repeat proteins in signal transduction. Cell. Signalling. 2007;19:20–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yamaguchi H., Matsushita M., Nairn A. C., Kuriyan J. Crystal structure of the atypical protein kinase domain of a TRP channel with phosphotransferase activity. Mol. Cell. 2001;7:1047–1057. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00256-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ye Q., Crawley S. W., Yang Y., Cote G. P., Jia Z. Crystal structure of the α-kinase domain of Dictyostelium myosin heavy chain kinase A. Sci. Signaling. 2010;3:ra17. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2000525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith E. M., Proud C. G. Cdc2-cyclin B regulates eEF2 kinase activity in a cell cycle- and amino acid-dependent manner. EMBO J. 2008;27:1005–1016. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang X., Li W., Williams M., Terada N., Alessi D. R., Proud C. G. Regulation of elongation factor 2 kinase by p90RSK1 and p70 S6 kinase. EMBO J. 2001;20:4370–4379. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Knebel A., Morrice N., Cohen P. A novel method to identify protein kinase substrates: eEF2 kinase is phosphorylated and inhibited by SAPK4/p38δ. EMBO J. 2001;20:4360–4369. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knebel A., Haydon C. E., Morrice N., Cohen P. Stress-induced regulation of eEF2 kinase by SB203580-sensitive and -insensitive pathways. Biochem. J. 2002;367:525–532. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Browne G. J., Finn S. G., Proud C. G. Stimulation of the AMP-activated protein kinase leads to activation of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase and to its phosphorylation at a novel site, serine 398. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:12220–12231. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309773200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Redpath N. T., Proud C. G. Purification and phosphorylation of elongation factor-2 kinase from rabbit reticulocytes. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993;212:511–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark K., Middelbeek J., Morrice N. A., Figdor C. G., Lasonder E., van Leeuwen F. N. Massive autophosphorylation of the Ser/Thr-rich domain controls protein kinase activity of TRPM6 and TRPM7. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1876. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsushita M., Kozak J. A., Shimizu Y., McLachlin D. T., Yamaguchi H., Wei F. Y., Tomizawa K., Matsui H., Chait B. T., Cahalan M. D., Nairn A. C. Channel function is dissociated from the intrinsic kinase activity and autophosphorylation of TRPM7/ChaK1. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:20793–20803. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M413671200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schmitz C., Dorovkov M. V., Zhao X., Davenport B. J., Ryazanov A. G., Perraud A. L. The channel kinases TRPM6 and TRPM7 are functionally nonredundant. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:37763–37771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hermosura M. C., Nayakanti H., Dorovkov M. V., Calderon F. R., Ryazanov A. G., Haymer D. S., Garruto R. M. A TRPM7 variant shows altered sensitivity to magnesium that may contribute to the pathogenesis of two Guamanian neurodegenerative disorders. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005;102:11510–11515. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505149102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Medley Q. G., Gariepy J., Cote G. P. Dictyostelium myosin II heavy-chain kinase A is activated by autophosphorylation: studies with Dictyostelium myosin II and synthetic peptides. Biochemistry. 1990;29:8992–8997. doi: 10.1021/bi00490a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crawley S. W., Gharaei M. S., Ye Q., Yang Y., Raveh B., London N., Schueler-Furman O., Jia Z., Cote G. P. Autophosphorylation activates Dictyostelium myosin II heavy chain kinase A by providing a ligand for an allosteric binding site in the α-kinase domain. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:2607–2616. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.177014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Deprez J., Vertommen D., Alessi D. R., Hue L., Rider M. H. Phosphorylation and activation of heart 6-phosphofructo-2-kinase by protein kinase B and other protein kinases of the insulin signaling cascades. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:17269–17275. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.28.17269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horman S., Morel N., Vertommen D., Hussain N., Neumann D., Beauloye C., El N. N., Forcet C., Viollet B., Walsh M. P., et al. AMP-activated protein kinase phosphorylates and desensitizes smooth muscle myosin light chain kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:18505–18512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802053200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Woods A., Vertommen D., Neumann D., Turk R., Bayliss J., Schlattner U., Wallimann T., Carling D., Rider M. H. Identification of phosphorylation sites in AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) for upstream AMPK kinases and study of their roles by site-directed mutagenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:28434–28442. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303946200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ulintz P. J., Yocum A. K., Bodenmiller B., Aebersold R., Andrews P. C., Nesvizhskii A. I. Comparison of MS2-only, MSA, and MS2/MS3 methodologies for phosphopeptide identification. J. Proteome Res. 2009;8:887–899. doi: 10.1021/pr800535h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fonseca B. D., Smith E. M., Lee V. H., MacKintosh C., Proud C. G. PRAS40 is a target for mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 and is required for signaling downstream of this complex. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:24514–24524. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704406200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fonseca B. D., Alain T., Finestone L. K., Huang B. P., Rolfe M., Jiang T., Yao Z., Hernandez G., Bennett C. F., Proud C. G. Pharmacological and genetic evaluation of proposed roles of mitogen-activated protein kinase/extracellular signal-regulated kinase kinase (MEK), extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK), and p90RSK in the control of mTORC1 protein signaling by phorbol esters. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:27111–27122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.260794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hall-Jackson C. A., Cross D. A., Morrice N., Smythe C. ATR is a caffeine-sensitive, DNA-activated protein kinase with a substrate specificity distinct from DNA-PK. Oncogene. 1999;18:6707–6713. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Browne G. J., Proud C. G. A novel mTOR-regulated phosphorylation site in elongation factor 2 kinase modulates the activity of the kinase and its binding to calmodulin. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2004;24:2986–2997. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.7.2986-2997.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bradford M. M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 1976;77:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pigott C. R., Mikolajek H., Moore C. E., Finn S. J., Phippen C. W., Werner J. M., Proud C. G. Insights into the regulation of eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase and the interplay between its domains. Biochem. J. 2012;442:105–118. doi: 10.1042/BJ20111536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crawley S. W., Cote G. P. Identification of dimer interactions required for the catalytic activity of the TRPM7 α-kinase domain. Biochem. J. 2009;420:115–122. doi: 10.1042/BJ20081405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abramczyk O., Tavares C. D., Devkota A. K., Ryazanov A. G., Turk B. E., Riggs A. F., Ozpolat B., Dalby K. N. Purification and characterization of tagless recombinant human elongation factor 2 kinase (eEF-2K) expressed in Escherichia coli. Protein Expression Purif. 2011;79:237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2011.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Crawley S. W., Cote G. P. Determinants for substrate phosphorylation by Dictyostelium myosin II heavy chain kinases A and B and eukaryotic elongation factor-2 kinase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1784:908–915. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Olsen J. V., Blagoev B., Gnad F., Macek B., Kumar C., Mortensen P., Mann M. Global, in vivo, and site-specific phosphorylation dynamics in signaling networks. Cell. 2006;127:635–648. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yeaman S. J., Cohen P., Watson D. C., Dixon G. H. The substrate specificity of adenosine 3′:5′-cyclic monophosphate-dependent protein kinase of rabbit skeletal muscle. Biochem. J. 1977;162:411–421. doi: 10.1042/bj1620411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rodriguez J., Gupta N., Smith R. D., Pevzner P. A. Does trypsin cut before proline? J. Proteome Res. 2008;7:300–305. doi: 10.1021/pr0705035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Horman S., Browne G. J., Krause U., Patel J. V., Vertommen D., Bertrand L., Lavoinne A., Hue L., Proud C. G., Rider M. H. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase leads to the phosphorylation of elongation factor 2 and an inhibition of protein synthesis. Curr. Biol. 2002;12:1419–1423. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)01077-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Redpath N. T., Proud C. G. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase phosphorylates rabbit reticulocyte elongation factor-2 kinase and induces calcium-independent activity. Biochem. J. 1993;293:31–34. doi: 10.1042/bj2930031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Diggle T. A., Subkhankulova T., Lilley K. S., Shikotra N., Willis A. E., Redpath N. T. Phosphorylation of elongation factor-2 kinase on serine 499 by cAMP-dependent protein kinase induces Ca2+/calmodulin-independent activity. Biochem. J. 2001;353:621–626. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3530621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crawley S. W., Liburd J., Shaw K., Jung Y., Smith S. P., Cote G. P. Identification of calmodulin and MlcC as light chains for Dictyostelium myosin-I isozymes. Biochemistry. 2011;50:6579–6588. doi: 10.1021/bi2007178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horman S., Vertommen D., Heath R., Neumann D., Mouton V., Woods A., Schlattner U., Wallimann T., Carling D., Hue L., Rider M. H. Insulin antagonizes ischemia-induced Thr172 phosphorylation of AMP-activated protein kinase α-subunits in heart via hierarchical phosphorylation of Ser485/491. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:5335–5340. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M506850200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.