Abstract

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) are members of the TGF-β superfamily of signaling molecules. BMPs can elicit a wide range of effects in many cell types and have previously been shown to induce growth inhibition in carcinoma cells as well as normal epithelia. Recently, it has been demonstrated that BMP4 and BMP7 are overexpressed in human breast cancers and may have tumor suppressive and promoting effects. We sought to determine whether disruption of the BMP receptor 2 (BMPR2) would alter mammary tumor progression in mice that express the Polyoma middle T antigen. Mice expressing Polyoma middle T antigen under the mouse mammary tumor virus promoter were combined with mice that have doxycycline-inducible expression of a dominant-negative (DN) BMPR2. We did not observe any differences in tumor latency. However, mice expressing the BMPR2-DN had a fivefold increase in lung metastases. We characterized several cell autonomous changes and found that BMPR2-DN–expressing tumor cells had higher rates of proliferation. We also identified unique changes in inflammatory cells and secreted chemokines/cytokines that accompanied BMPR2-DN–expressing tumors. By immunohistochemistry, it was found that BMPR2-DN primary tumors and metastases had an altered reactive stroma, indicating specific changes in the tumor microenvironment. Among the changes we discovered were increased myeloid derived suppressor cells and the chemokine CCL9. BMP was shown to directly regulate CCL9 expression. We conclude that BMPR2 has tumor-suppressive function in mammary epithelia and microenvironment and that disruption can accelerate mammary carcinoma metastases.

Bone morphogenetic proteins (BMPs) are a large family of secreted molecules that belong to the TGF-β superfamily. BMPs regulate a wide range of developmental functions, as well as more complicated roles in cell homeostasis not limited to migration, apoptosis, proliferation, and differentiation (reviewed in ref. 1). BMP ligands, when they have been processed into mature forms and secreted, bind to type I and II serine/threonine kinase receptors (BMPR1 and BMPR2). Binding of ligand results in phosphorylation of Smad proteins 1, 5, and 8, which move to the nucleus with the common partner Smad4 and bind sequence-specific regions in the genome to regulate transcription of target genes. Currently, there are more than 20 known BMP ligands and at least 10 antagonists, which operate with varied duration, distance, and affinity (1).

In carcinomas, BMP signaling is known to have widespread tumor-suppressive function, particularly in colon cancers in which mutations in BMPR1a and Smad4 are prevalent (2, 3). Treatment with BMPs in vitro has mainly mirrored the effects of TGF-β by inducing growth arrest and an epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition (EMT) (4, 5). BMP ligands are widely expressed in the developing mammary gland (6). BMPs also induce strong effects on cells in 3D collagen matrices and synergize with other growth factors to stimulate or attenuate cell proliferation (7, 8). Loss of BMPR2 in the stroma of the colon leads to epithelial growth and polyp formation (9). Loss of BMP receptors has been observed in more aggressive prostate cancers (10). Recently, BMP4 has also been implicated as a specific suppressor of metastases (11).

Similar to the dual roles of TGF-β, BMPs have also shown tumor-promoting roles in cancer. In human breast cancer, recent evidence has demonstrated that overexpression of BMPs (specifically BMP4 and BMP7) correlates with advanced disease (12, 13). It has also been shown that, when breast cancer cell lines are treated with BMP4, they have enhanced migration and invasion (4, 5, 7, 14). BMP2 has been shown to promote breast cancer microcalcification (15). BMP2 has been shown to induce tenascin-W, an ECM-related molecule found in advanced breast tumors (16). Inhibition of BMPR2 has been shown to inhibit growth and viability of breast cancer cells (17). The expression of BMPR1b has been shown to be increased in estrogen-positive poorly differentiated tumors (18). The mechanisms of BMP regulated tumor progression and metastasis remains unresolved, and contributions to cell autonomous and the tumor microenvironment remain largely unexplored.

To resolve whether BMPR2 has tumor-promoting or -suppressive function in vivo, we combined a conditional tissue-specific doxycycline-inducible dominant-negative (DN) BMPR2 (19) with the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) Polyoma middle T antigen (PyVmT) mouse model of mammary carcinoma formation (20). Because of the vast number of secreted ligands and extracellular regulators of BMP signaling, we chose to focus on type II receptor BMPR2. It was determined that expression of the BMPR2-DN caused an acceleration of tumor progression with a marked increase in lung metastases through cell-autonomous and paracrine mechanisms, the latter likely through increased secretion of Ccl9. In addition, Ccl9 gene expression is shown to be directly regulated by Smad1/5/8.

Results

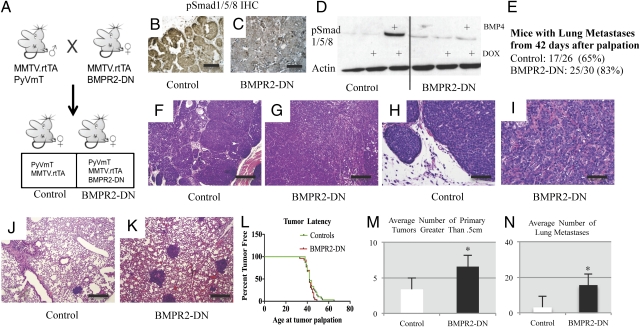

Generation of Mouse Mammary Tumors Expressing BMPR2-DN.

MMTV.PyVmT mice were combined with transgenic mice that also direct expression of the reverse tetracycline-controlled trans-activator (rtTA) from the MMTV promoter, allowing induction of TetO with administration of doxycycline (21). Doxycycline was fed to mice beginning at 21 d of age. These bigenic mice served as controls (referred to as control hereafter) whereas BMPR2-DN animals further included a TetO-containing DN for the BMPR2 receptor (referred to as BMPR2-DN hereafter), which has a deletion at exon 4 corresponding to the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor (19) (Fig. 1A). This deletion results in an inability to phosphorylate downstream Smads in the BMP signaling pathway. Mice were maintained in a pure FVBn background. We performed immunohistochemistry (IHC) for phosphorylated Smad1/5/8, which is an indication of active BMP signaling. BMPR2-DN mammary tumors displayed an overall decrease in positive nuclear staining, demonstrating inhibition of BMP signaling by the BMPR2-DN transgene (Fig. 1 B and C). We further tested the ability of the BMPR2-DN transgene to inhibit BMP signaling by establishing primary cultures of tumor cells. These cells, when grown in the presence of doxycycline, also demonstrated that active phosphorylation of Smad1/5/8 was inhibited upon stimulation with BMP4 (Fig. 1D). Forty-two days after first palpation of tumors, 65% of control mice (17 of 26) and 83% of BMPR2-DN mice (25 of 30) had metastatic lung foci (Fig. 1E). Examination of the histopathology of the primary tumor showed typical adenocarcinoma common to the MMTV.PyVmT model (Fig. 1 F and H); BMPR2-DN tumors exhibited regions of desmoplasia and a different architecture that indicated increased stromal microenvironment interaction with the tumors (Fig. 1 G and I). Controls were found to have metastases that were small and sparse (Fig. 1J). However, the BMPR2-DN lungs had large foci densely located throughout the lungs (Fig. 1K). No difference was observed in tumor latency (Fig. 1L), but the average number of primary tumors that exceeded 0.5 cm in size was almost double (6) in BMPR2-DN compared with controls (3) (Fig. 1M). Importantly, the average number of lung metastases in BMPR2-DN mouse lungs was 16, compared with three in controls (Fig. 1N).

Fig. 1.

Disruption of BMPR2 in MMTV.PyVmT mice accelerates tumor progression and metastasis. (A) Male mice containing the transgenes for MMTV.rtTA and MMTV.PyVmT were mated to females that contained the transgenes MMTV.rtTA and TetO-BMPR2-DN, which produced control animals that were double positive for MMTV.rtTA and MMTV.PyVmT, whereas BMPR2-DN mice contained all three transgenes. Mice were fed doxycycline 21 d after birth during weaning. (B) IHC for active BMP signaling via pSmad1/5/8 indicated active BMP-Smad activity in control tumors. (C) BMPR2-DN tumors had diminished pSmad1/5/8 IHC staining, indicating inhibition of BMP signaling. (D) Primary cultured tumor cells grown in the presence of 1 μg/mL of doxycycline prevented increased phosphorylation in BMPR2-DN cells, yet not in controls. BMP4 was added for 1 h at 100 ng/mL. (E) Control mice analyzed 42 d after first tumor palpation had 65% incidence (17 of 26) of observable lung metastases, whereas BMPR2-DN mice had 83% incidence (25 of 30) of lung metastases. (F–K) H&E staining indicated morphological changes in control (F and H) primary and BMPR2-DN (G and I) tumors. Lung metastases were fewer and more sparse in controls (J) compared with BMPR2-DN mice (K), which was quantified (N) as controls averaging three metastatic foci and BMPR2-DN having 15 foci. (L) Tumor latency was determined by measuring the date of birth with when tumors could be first palpated. No statistical difference could be determined. (M) The average number of primary tumors in the 10 total mammary glands of control mice was three, compared with six in BMPR2-DN mice. (N) Lung tissue sections were counted for number of metastatic foci. *Significant at P < 0.01, two-tailed unpaired Student t test. (Scale bars: B and C, 200 μM; F–K, 500 μM.)

Inhibition of BMP Signaling in the Mammary Gland Did Not Affect Mammary Gland Development.

BMP has been implicated in the early development and formation of the mammary gland (22). Furthermore, inhibition of BMP signaling with the soluble antagonist Noggin can convert nipple epithelia into hair follicles (23). However, BMPR2-DN mice were found to have normal histopathology with luminal epithelial cells fully migrated to the distal tip of the fat pad (Fig. S1C), and that luminal architecture appeared typical compared with controls (Fig. S1). Furthermore, BMPR2-DN mice induced the DN only at weaning, when much of the mammary gland is specified. Additionally, by using a DN and not KO, we still retained endogenous BMPR2 receptors.

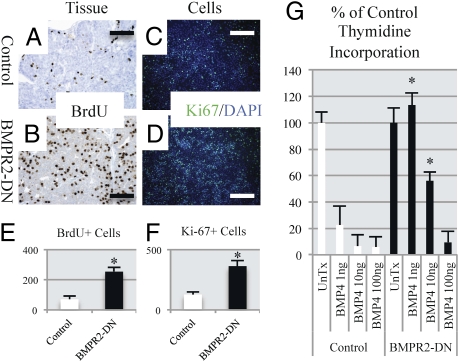

Inhibition of BMP Signaling in the Mammary Gland Increases Tumor Cell Proliferation in Vivo and in Vitro.

Two hours before animals were euthanized, they were injected with BrdU to label newly dividing cells. It was observed that tumors from BMPR2-DN animals incorporated more BrdU and had more Ki-67–positive nuclei, indicating increased proliferation (Fig. 2 A–D). We quantified the IHC and immunofluorescence (IF) staining and found statistically significant increases in the number of BrdU-positive cells (Fig. 2E) in primary tumors and Ki-67–positive cells in primary cultures (Fig. 2F) from BMPR2-DN–expressing tumors and cells. We next wanted to test whether BMPR2-DN tumor cells could respond to BMP4-induced growth arrest. Previous work has shown that treatment of cell lines with BMP4 inhibits growth of normal and transformed mammary epithelia (7, 14). We established primary tumor cell lines from the mice and, after four passages, performed [3H]thymidine incorporation assays to assess growth rates. It was found that, at 48 h, even modest concentrations of BMP4 were sufficient to induce growth inhibition in control cells, and that this was attenuated in BMPR2-DN cells (Fig. 2G). BMPR2-DN cells still retain their endogenous BMPR2, and we have observed that not all phosphorylation is absent in BMPR2-DN cells (Fig. 1 C and D). This may explain why, at high concentrations (100 ng/mL), BMP4 is sufficient to inhibit growth of BMPR2-DN cells as well as control cells (Fig. 2G). However, this effect was not apparent at lower concentrations (1–10 ng/mL), at which BMPR2-DN cells continued proliferating at higher rates than control cells (Fig. 2G).

Fig. 2.

Disruption of BMPR2 results in increased proliferation in mammary carcinomas. (A) IHC for BrdU was performed on control primary tumors, which indicated newly synthesized DNA in proliferating cells. (B) BMPR2-DN primary tumors had increased positive number of nuclei with BrdU staining. (C) Primary cells derived from control tumors were stained for the Ki-67 marker of proliferation and compared with BMPR2-DN primary cultured cells (D), which had increased number of Ki-67–positive cells. Cells were costained with DAPI to indicate total number of cells present. (E) Quantification of IHC (A and B) BrdU-positive cells indicates three times more positive cells in BMPR2-DN than control tissue section. (F) Quantification of IF (C and D) demonstrated three times the number of proliferating cells in primary cell lines in BMPR2-DN tumors compared with controls. (G) Cultured cells were treated with increasing levels of BMP4 for 48 h were analyzed for incorporation of tritiated thymidine. Quantification of IF/IHC was performed with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health), analyzing at least five different tumors with three areas each. *P < 0.01. Primary cells were cultured for at least 48 h in doxycycline (1 μg/mL) and seeded at equal densities. (Scale bars: 200 μM.)

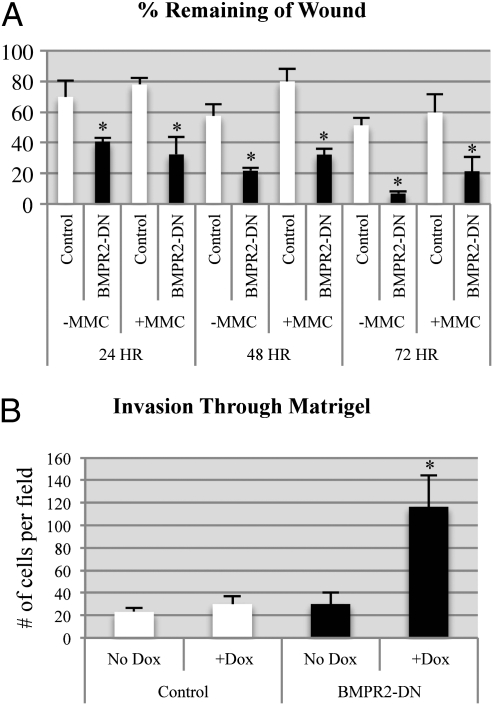

Inhibition of BMP Signaling in Mammary Tumors Enhances Migration and Invasion.

We next determined whether attenuated BMP signaling in tumor cells altered their migration and invasion phenotypes. Previous studies had suggested that BMP could stimulate breast cancer cell migration (5, 14). Surprisingly, when we compared BMPR2-DN tumor cells with controls, we found that BMPR2-DN cells were able to more rapidly fill an artificial scratch wound assay (Fig. 3A and Fig. S2I). To ensure that the cells were not merely closing the scratched area as a result of enhanced proliferation, we treated cells with mitomycin-C to inhibit proliferation. BMPR2-DN cells were still more capable of closing the wound via migration into the scratched area (Fig. 3A). It was next determined whether this enhanced migration also related to tumor cells invasion properties. Carcinoma cells (2.5 × 105 cells per well) were placed on Matrigel-coated transwells, and after 18 h, cells that had invaded through Matrigel were quantified. BMPR2-DN cells invaded much more aggressively when the BMPR2 DN receptor was induced in the presence of doxycycline (Fig. 3B). Another hallmark of invasion is the enhanced ability of tumor cells to undergo EMT. It was observed that BMPR2-DN tumors had enhanced regions of double-positive staining for markers of EMT (Fig. S2 A–D). BMPR2-DN tumors had regions juxtaposed to the stromal–tumor interface that were expressing vimentin, which is a hallmark of EMT (Fig. S2 A–D). We also observed that BMPR2-DN tumors had an altered morphological appearance (Fig. 1D) and performed IF for basement membrane components laminin and β4 integrin, which were more abundant in BMPR2-DN tumors (Fig. S2 E–H).

Fig. 3.

Disruption of BMPR2 results in increased invasion and migration of mammary carcinoma cells. (A) Confluent cultures of primary tumor cells were scratched with a 200-μL pipette tip and photographed at 24-h intervals to determine the ability of the cells to heal the area scratched. Control and BMPR2-DN cells were also treated with 10 μg/mL mitomycin-C (MMC) for 1 h before scratch to block proliferation. Quantification of wound closure was performed by measuring the linear distance between the opposing edges in four measurements for three experiments each. Data are represented as percentage of original distance at the time of the scratch. (B) Primary control and BMPR2-DN cells were plated above 8-μM-pore transwells coated in Matrigel. Cells were allowed to invade for 18 h and then counted in five 20× images per triplicate field of view. Control and BMPR2-DN cells were treated with and without 1 μg/mL of doxycycline. *P < 0.01, two-tailed unpaired Student t test.

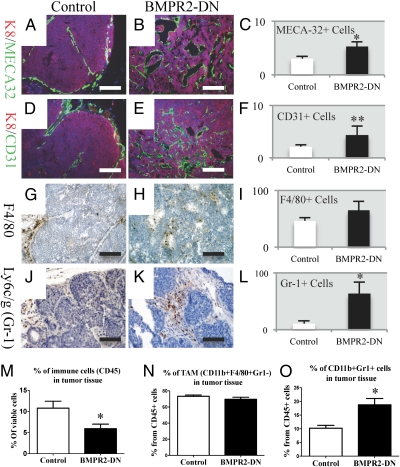

Disruption of BMP Signaling in Mammary Tumors Causes Alterations in the Tumor Microenvironment Resulting in Increased Angiogenesis and Inflammation.

To determine whether angiogenesis was enhanced in BMPR2-DN tumors, we performed IF staining for markers of endothelial cells. Staining for CD31 (PECAM) and MECA-32, which labels endothelial cells, illustrated the increased presence of blood vessels in BMPR2-DN tumors (Fig. 4 A–F). We next asked whether myeloid cells were present in the tissues. We found that macrophages were present in both tumors (Fig. 4 G and H). Interestingly, when we stained for Gr-1 (Ly6c/g), which indicates neutrophils or myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) (24), we observed large clusters of Gr-1–positive cells exclusively in BMPR2-DN tumors (Fig. 4 J and K). These observations were confirmed by quantifying our IF and IHC staining and determined that BMPR2-DN tumors had increased blood vessels as a percentage of area than controls (Fig. 4 C and F). We were not able to find a statistical difference in F4/80-stained cells in IHC sections of primary tumors (Fig. 4I). However, we did discover a significant increase in Gr-1–positive cells in primary tumor sections by IHC in BMPR2-DN tumors (Fig. 4L). To further analyze immune cell content, we performed flow cytometry analysis of dissociated primary tumors and demonstrated that BMPR2-DN tumors contained less immune cells as a percentage of total viable cells, indicating suppression of distinct immune cell subtypes (Fig. 4M). The percentage of F4/80-positive macrophages was not significantly different between control and BMPR2-DN tumors (Fig. 4N). However, Gr-1-positive, CD11b-positive cells (i.e., MDSCs) were significantly more abundant in BMPR2-DN tumors (Fig. 4O).

Fig. 4.

Loss of BMPR2 signaling in mammary tumors results in increased inflammation and myeloid cell infiltrates. IF staining for the panendothelial marker MECA32 (green) in control (A) and BMPR2-DN (B) tumors. (C) Quantification of IF (A and B) revealed more panendothelial cells in BMPR2-DN tissue sections than controls. (D) IF staining for the endothelial marker CD31 (green) also demonstrated that tumor vasculature was mainly restricted to the surrounding tumor, whereas in BMPR2-DN (E), tumor vessels can be seen throughout the tumor. (F) Quantification of IF (D and E) demonstrated more blood vessels in BMPR2-DN tissue sections than controls. IHC staining for macrophage marker F4/80 (brown) demonstrated the presence of macrophages in primary tumors control (G) and BMPR2-DN (H). (I) Quantification of IHC (G and H) did not reveal significant changes in F4/80-positive macrophages in primary tumors. IHC staining for Ly6c/g (Gr-1) myeloid cells (brown) was found to be increased in BMPR2-DN tumors (K) compared with controls (J). (L) Quantification of IHC (J and K) showed more MDSCs/neutrophils in primary tumor tissue sections than controls. (M) Flow cytometry for CD45+ cells showed a decrease in immune cells in BMPR2-DN tumors. (N) Flow cytometry for F4/80 did not reveal any significant changes between BMPR2-DN and control primary tumors. (O) Flow cytometry for CD11b+ and Gr-1+ double-positive cells were significantly increased in BMPR2-DN tumors compared with controls. Flow cytometry analysis comprised eight controls and eight mutants. All IHC staining was performed with hematoxylin (blue) to counterstain all nuclei. All IF staining was performed with DAPI (blue) to counterstain all nuclei. Quantification of IF/IHC was performed with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health), analyzing at least five different tumors. *P < 0.01 and **P < 0.05, two-tailed unpaired Student t test. (Scale bars: A, B, D, and E, 200 μM; G, H, J, and K, 100 μM.)

Because a primary function of MDSCs is the inhibition of T-cell proliferation, we were interested in the T-cell populations and found that CD3, a marker of T cells, was reduced in BMPR2-DN tumors, indicating that the enhanced MDSC population is likely acting to inhibit T cells (Fig. S3I). However, we could not detect differences in levels of T cells by IHC in primary tumors or lung metastases (Fig. S3 A–D). Interestingly, the weight of BMPR2-DN spleens was greater than controls (Fig. S3K), yet the relative percentage of immune cells that were T cells was unaffected (Fig. S3J).

Attenuation of BMP Signaling Promotes Elevated Cytokines/Chemokines in the Tumor Microenvironment.

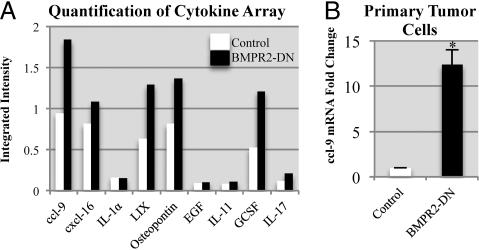

The possibility was examined that secretion of paracrine factors that could be responsible for the BMPR2-DN tumors' enhanced tumor progression and metastasis. Pooled tumor sample protein lysates were assayed by using a focused cytokine antibody array. Densitometry analysis demonstrated changes in BMPR2-DN protein secretion profile of primary tumors (Fig. S4 B and C). We next compared this with conditioned medium containing secreted factors from the primary cultures of carcinoma cells (Fig. 5A and Fig. S4A). It was found that, among the unique changes in the whole tumor microenvironment and primary tumor cells, a select group of molecules were overrepresented (Fig. 5A). Most interesting was the presence of CCL9 (MIP-1γ), which had recently been shown to be a key recruitment factor for immature myeloid cells in tumor and metastasis progression (25). We found that mRNA for Ccl9 was highly up-regulated in BMPR2-DN tumor tissue (Fig. S4C), as well as in the medium conditioned by primary cultures of BMPR2-DN tumor cells (Fig. 5B). This indicated that CCL9 is at least partially derived from BMPR2-DN carcinoma cells (Fig. 5C). However, the mRNA of Ccl9 in tissue was much higher than controls in tissue (Fig. S4C), which may highlight the importance of comparing monocultures and tissues in vivo.

Fig. 5.

Loss of BMP signaling promotes unique chemokine/cytokine and growth factor alterations. (A) Conditioned medium derived from primary culture of tumors profiled by Raybiotech cytokine arrays III, IV, and V. BMPR2-DN and control cells grown for 48 h until approximately 70% to 80% confluent in the presence of doxycycline (1 μg/mL) and 1 mL of conditioned medium was pooled from three cell lines and compared for signal intensity with ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health) and normalized to internal loading controls. (B) qPCR for CCL9 was performed by isolating RNA from the cells in which conditioned media was isolated for analysis in A and B. mRNA levels were normalized to GAPDH. *P < 0.01, two-tailed unpaired Student t test.

Ccl9 Expression Is Regulated by BMP.

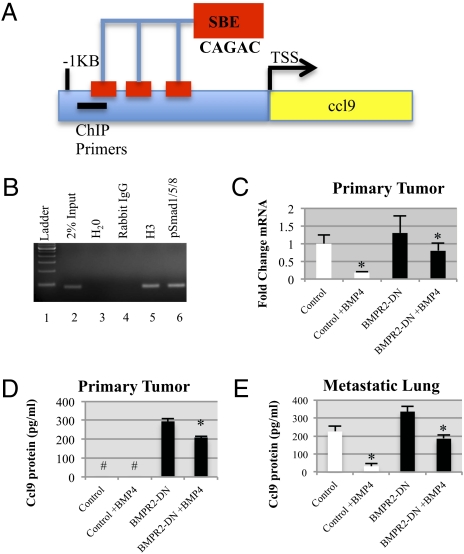

It was next determined whether BMP directly regulates expression of Ccl9. We examined the sequence elements in the proximal promoter of the Ccl9 gene. A search for high-quality Smad binding elements (SBEs) demonstrated three CAGAC sequences located at positions −718, −648, and −548 relative to the transcriptional start site (Fig. 6A). We prepared crosslinked and sheared chromatin from primary tumor control cultured cells, which was immunoprecipitated using pSmad1/5/8 antibodies. PCR of the coimmunoprecipitated DNA using primers specific for the Ccl9 promoter showed pSmad1/5/8 binding to this promoter (Fig. 6B, lane 6). Next, we treated control and BMPR2-DN primary cell cultures with BMP4 and found that, in control cells, BMP4 was able to reduce Ccl9 mRNA by approximately fivefold; however, BMPR2-DN cells had only slightly reduced Ccl9 mRNA compared with controls (Fig. 6C). We next examined protein secretion and found that primary control cells secrete small but detectable levels of CCL9 protein, but BMPR2-DN cells expressed large amounts that were not significantly inhibited by BMP4 treatment (Fig. 6D). We next established a primary culture of carcinoma cells from lung metastases. Interestingly, control cells now secreted high levels of CCL9, which was inhibited by BMP4 treatment, yet BMPR2-DN cells from the lung expressed even higher amounts of CCL9 and only modestly responded to BMP4 treatment (Fig. 6E).

Fig. 6.

CCL9 expression is regulated by BMP. (A) SBEs CAGAC are located in the proximal portion of the Ccl9 promoter at positions −718, −648, and −548 relative to the transcriptional start site (TSS). (B) ChIP analysis confirms BMP Smad1/5/8 occupancy of the CCL9 promoter. PCR primers that amplify 82 bp of the CCL9 promoter from position −949 relative to the TSS were detected in 2% enzymatically sheared chromatin (lane 2) and in immunoprecipitation of 3H and pSmad1/5/8 antibodies. (C) qPCR demonstrates that BMP4 inhibits Ccl9 expression and that disruption of BMPR2-DN results in unresponsiveness to BMP4 stimulation. Cells were treated with 10 ng/mL of BMP4 for 24 h. (D) ELISA determined that conditioned medium collected from primary tumor cultures was not detected (#) in controls or controls treated with BMP4. However, BMPR2-DN cells expressed high levels of CCL9 protein, and treatment with 10 ng/mL of BMP4 for 24 h was partially able to decrease CCL9 protein secretion. (E) ELISA for CCL9 showed that cells derived from lungs metastases expressed high levels of CCL9, and BMPR2-DN cells had significantly higher levels. BMPR2-DN cells showed only a slight decrease in protein secretion, whereas BMP4 treatment of control lung metastatic cells showed a marked decrease in CCL9 secretion. All cultured cells were grown in the presence of doxycycline (1 μg/mL). *P < 0.01, two-tailed unpaired Student t test.

Discussion

Generation of a New Mutant BMP Mouse Mammary Tumor Model.

We report a spontaneous model of breast cancer and metastasis with an attenuation of BMP signaling. Previous models have used only cultured cells or xenograft transplants. Disruption of BMPR2 demonstrated a tumor-suppressive function for BMP signaling in the epithelium. We have shown in vivo that BMPR2 has a growth-inhibitory function and that disruption of BMPR2 increases metastatic progression, indicating that BMPR2 is important in the control of cell proliferation, migration, and invasion. Additionally, when BMPR2 signaling was disrupted, paracrine changes in the tumor microenvironment promoted myeloid cell recruitment and enhanced metastatic dissemination to the lungs. BMP directly regulated and inhibited the expression of the myeloid cell chemokine CCL9. The loss of BMP signaling was sufficient to alter the morphology and phenotype of carcinomas, which provides a further understanding to different pathologies of breast cancer progression (Fig. 1 F–I and Fig. S2 A–H).

BMP Regulation of Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion.

Recently, it has been shown that human breast cancer cell lines treated exogenously with BMP can inhibit the growth of these cells (14, 26–29). We also observe this phenotype (Fig. 2E) and show that carcinoma cells require BMPR2 for BMP-mediated growth inhibition. The attenuation of BMP signaling enhanced the proliferation of tumor cells, yet did not result in hyperplasia in nontumor controls (Fig. S1 A–D). This suggests that BMP regulation of proliferation in vivo may require transformation into tumor cells.

BMP treatment can enhance cell migration in vitro in transformed and nontransformed mammary epithelial cells (4, 5, 7, 14). Our findings show that an attenuation of BMP signaling can enhance migration and invasion. This may seem paradoxical that loss of BMPR2 signaling could also result in enhanced migration of tumor cells. The mode of migration and invasion may be more complex and require further study, yet it is clear that BMP ligands and receptors modulate key pathways guiding tumor cell invasion and migration.

Role of BMP in Inflammatory Tumor Microenvironment.

Data presented herein indicate that attenuation of BMP signaling results in increased secretion of cytokines and chemokines and increased infiltration of subsets of myeloid cells. This change does not transiently resolve and progresses to drive tumorigenesis and metastasis. We have previously made similar discoveries with knockout of the type II TGF-β receptor (Tgfbr2KO) in combination with PyVmT expression (30–32). Similarities included accelerated metastatic progression (31), accumulation of MDSCs (32), and increased expression of CCL9 as well as other chemokines (30). MDSCs are a significant population of cells that promote metastasis via suppression of T cells and enhance MMP-mediated invasion (32). However, there are some differences in the phenotypes of BMPR2-DN mice and that observed with the Tgfbr2KO mice. BMPR2-DN mice do not demonstrate hyperplasia or defects in mammary gland development, as was found in the Tgfbr2KO mice (31). Additionally, tumor latency was significantly reduced in the Tgfbr2KO mice but not in the present model (30, 31). This suggests that BMPR2 signaling may have a specific role in tumor progression and not initiation. It should be noted that these models are not entirely similar and that KO versus DN may result in discrepancies that will be answered by comparing TβRII DN or BMPR2 KO mammary tumors. Interestingly, our laboratory previously showed that loss of TβRII resulted in less CD31 and blood vessels in KO tumors (30); however, we find that BMPR2-DN have more vessels associated with their tumors (Fig. 4 A–F). Finally we also did not observe changes with differentiation markers such as cytokeratin 8 (Fig. S2 A–D), which was lost at the expansion of the more basal cytokeratin 5 in Tgfbr2KO tumors (30). When we investigated the differences in TGF-β1 and BMP4 levels, we did not detect significant changes (Fig. S5). These findings have guided our hypotheses that BMP functionally overlaps with TGF-β and that unique and shared functions still remain to be delineated.

BMPs have been shown to be global regulators of transcriptional networks, including the repression or silencing of genes (33). We find here that BMP4 reduces the expression of CCL9 (Fig. 6 C–E) and that BMP-specific Smad1, Smad5, and Smad8 occupy the proximal promoter (Fig. 6B). CCL9 is an important chemokine that regulates progression of colon carcinoma cells that lack Smad4 (25, 34). This loss of Smad4 has the unique distinction of affecting both TGF-β and BMP signaling. It was found in this model that CCL9 regulated the recruitment of an immature myeloid cell population, which facilitated progression (25). We have provided a mechanism demonstrating the requirement for BMPR2 in tumors to prevent CCL9 secretion and the recruitment of myeloid cells. Future studies are currently aimed at discovering the unique responses to BMP signaling in the diverse cell populations that facilitate tumor progression.

Methods

Mice, Genotyping, Tumor Studies, Quantitative PCR, Identification of SBEs, and ChIP.

All mice were maintained in a pure FVBn background in accordance with the Vanderbilt University institutional animal care and use committee guidelines. Transgenic mice that express the BMPR2-DelEx4-DN, which were previously described (19), were mated with previously described MMTV.rtTA mice (21) to inhibit BMP signaling under the control of doxycycline, which was administered in chow at a concentration of 1 g/kg (Bio-Serv). Mice were fed doxycycline beginning at 21 d after birth during weaning. These mice were then mated with MMTV.PyVmT transgenic mice (20). Tumor studies were performed under Institutional guidelines whereby animals that had weight loss, tumor size (>1.5 cm) or distress (vocalization) Mice were provided enrichment and shelter and monitored and palpated three times weekly for tumor progression, development, and/or growth.

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) primers for CCL9 were as follows: forward, AGC GTG GGG TGG ACC TAC CG; and reverse, GGG GCC CAT TCC CGC CAA AT. ChIP primers for the CCL9 promoter were as follows: forward, AGAGCTTGGAGAGGCGTTCCTCA; and reverse, TGAAGGAGCCCTTTGCTGGCAA. The Ccl9 promoter was scanned for SBE by using tools from rVista (http://rvista.dcode.org) to analyze high-quality Smad matrices derived from the Transfac database. ChIP was performed with SimpleChIP with enzymatic digestion and magnetic IgG beads (Cell Signaling) following manufacturer recommendations. Additional details of study methods are provided in SI Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank members of the H.L.M. laboratory for reading the manuscript. This work was supported by Vanderbilt-Ingram Cancer Center Core Facilities Grant CA068485; the TJ Martell Foundation/Frances Preston Williams Laboratory; Department of Defense–Breast Cancer Research Program postdoctoral fellowship Award BC087501 (to P.O.); and National Institutes of Health Grants R01 CA085492 and R01 CA102162 (to H.L.M.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. K.P. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1101139108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Feng XH, Derynck R. Specificity and versatility in tgf-beta signaling through Smads. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:659–693. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.022404.142018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thiagalingam S, et al. Evaluation of candidate tumour suppressor genes on chromosome 18 in colorectal cancers. Nat Genet. 1996;13:343–346. doi: 10.1038/ng0796-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Howe JR, et al. Germline mutations of the gene encoding bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1A in juvenile polyposis. Nat Genet. 2001;28:184–187. doi: 10.1038/88919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clement JH, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein 2 (BMP-2) induces in vitro invasion and in vivo hormone independent growth of breast carcinoma cells. Int J Oncol. 2005;27:401–407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Katsuno Y, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein signaling enhances invasion and bone metastasis of breast cancer cells through Smad pathway. Oncogene. 2008;27:6322–6333. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson GW. Cooperation of signalling pathways in embryonic mammary gland development. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:963–972. doi: 10.1038/nrg2227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Montesano R. Bone morphogenetic protein-4 abrogates lumen formation by mammary epithelial cells and promotes invasive growth. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;353:817–822. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Montesano R, Sarközi R, Schramek H. Bone morphogenetic protein-4 strongly potentiates growth factor-induced proliferation of mammary epithelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;374:164–168. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Beppu H, et al. Stromal inactivation of BMPRII leads to colorectal epithelial overgrowth and polyp formation. Oncogene. 2008;27:1063–1070. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim IY, et al. Loss of expression of bone morphogenetic protein receptor type II in human prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:7651–7659. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smith SC, Theodorescu D. Learning therapeutic lessons from metastasis suppressor proteins. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:253–264. doi: 10.1038/nrc2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies SR, Watkins G, Douglas-Jones A, Mansel RE, Jiang WG. Bone morphogenetic proteins 1 to 7 in human breast cancer, expression pattern and clinical/prognostic relevance. J Exp Ther Oncol. 2008;7:327–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alarmo EL, Kuukasjärvi T, Karhu R, Kallioniemi A. A comprehensive expression survey of bone morphogenetic proteins in breast cancer highlights the importance of BMP4 and BMP7. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;103:239–246. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9362-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ketolainen JM, Alarmo EL, Tuominen VJ, Kallioniemi A. Parallel inhibition of cell growth and induction of cell migration and invasion in breast cancer cells by bone morphogenetic protein 4. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;124:377–386. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0808-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu F, et al. Humoral bone morphogenetic protein 2 is sufficient for inducing breast cancer microcalcification. Mol Imaging. 2008;7:175–186. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scherberich A, et al. Tenascin-W is found in malignant mammary tumors, promotes alpha8 integrin-dependent motility and requires p38MAPK activity for BMP-2 and TNF-alpha induced expression in vitro. Oncogene. 2005;24:1525–1532. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pouliot F, Blais A, Labrie C. Overexpression of a dominant negative type II bone morphogenetic protein receptor inhibits the growth of human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:277–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Helms MW, et al. First evidence supporting a potential role for the BMP/SMAD pathway in the progression of oestrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. J Pathol. 2005;206:366–376. doi: 10.1002/path.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.West J, et al. Pulmonary hypertension in transgenic mice expressing a dominant-negative BMPRII gene in smooth muscle. Circ Res. 2004;94:1109–1114. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000126047.82846.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guy CT, Cardiff RD, Muller WJ. Induction of mammary tumors by expression of polyomavirus middle T oncogene: A transgenic mouse model for metastatic disease. Mol Cell Biol. 1992;12:954–961. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gunther EJ, et al. A novel doxycycline-inducible system for the transgenic analysis of mammary gland biology. FASEB J. 2002;16:283–292. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0551com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phippard DJ, et al. Regulation of Msx-1, Msx-2, Bmp-2 and Bmp-4 during foetal and postnatal mammary gland development. Development. 1996;122:2729–2737. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.9.2729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mayer JA, Foley J, De La Cruz D, Chuong CM, Widelitz R. Conversion of the nipple to hair-bearing epithelia by lowering bone morphogenetic protein pathway activity at the dermal-epidermal interface. Am J Pathol. 2008;173:1339–1348. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitamura T, et al. Inactivation of chemokine (C-C motif) receptor 1 (CCR1) suppresses colon cancer liver metastasis by blocking accumulation of immature myeloid cells in a mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:13063–13068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1002372107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pardali K, Kowanetz M, Heldin CH, Moustakas A. Smad pathway-specific transcriptional regulation of the cell cycle inhibitor p21(WAF1/Cip1) J Cell Physiol. 2005;204:260–272. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Soda H, et al. Antiproliferative effects of recombinant human bone morphogenetic protein-2 on human tumor colony-forming units. Anticancer Drugs. 1998;9:327–331. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199804000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghosh-Choudhury N, et al. Bone morphogenetic protein-2 blocks MDA MB 231 human breast cancer cell proliferation by inhibiting cyclin-dependent kinase-mediated retinoblastoma protein phosphorylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;272:705–711. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pouliot F, Labrie C. Role of Smad1 and Smad4 proteins in the induction of p21WAF1,Cip1 during bone morphogenetic protein-induced growth arrest in human breast cancer cells. J Endocrinol. 2002;172:187–198. doi: 10.1677/joe.0.1720187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bierie B, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta regulates mammary carcinoma cell survival and interaction with the adjacent microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2008;68:1809–1819. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forrester E, et al. Effect of conditional knockout of the type II TGF-beta receptor gene in mammary epithelia on mammary gland development and polyomavirus middle T antigen induced tumor formation and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2005;65:2296–2302. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yang L, et al. Abrogation of TGF beta signaling in mammary carcinomas recruits Gr-1+CD11b+ myeloid cells that promote metastasis. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Koinuma D, et al. Promoter-wide analysis of Smad4 binding sites in human epithelial cells. Cancer Sci. 2009;100:2133–2142. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01299.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kitamura T, et al. SMAD4-deficient intestinal tumors recruit CCR1+ myeloid cells that promote invasion. Nat Genet. 2007;39:467–475. doi: 10.1038/ng1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.