Abstract

In plants, microRNAs (miRNAs) regulate their mRNA targets by precisely guiding cleavages between the 10th and 11th nucleotides in the complementary regions. High-throughput sequencing-based methods, such as PARE or degradome profiling coupled with a computational analysis of the sequencing data, have recently been developed for identifying miRNA targets on a genome-wide scale. The existing algorithms limit the number of mismatches between a miRNA and its targets and strictly do not allow a mismatch or G:U Wobble pair at the position 10 or 11. However, evidences from recent studies suggest that cleavable targets with more mismatches exist indicating that a relaxed criterion can find additional miRNA targets. In order to identify targets including the ones with weak complementarities from degradome data, we developed a computational method called SeqTar that allows more mismatches and critically mismatch or G:U pair at the position 10 or 11. Precisely, two statistics were introduced in SeqTar, one to measure the alignment between miRNA and its target and the other to quantify the abundance of reads at the center of the miRNA complementary site. By applying SeqTar to publicly available degradome data sets from Arabidopsis and rice, we identified a substantial number of novel targets for conserved and non-conserved miRNAs in addition to the reported ones. Furthermore, using RLM 5′-RACE assay, we experimentally verified 12 of the novel miRNA targets (6 each in Arabidopsis and rice), of which some have more than 4 mismatches and have mismatches or G:U pairs at the position 10 or 11 in the miRNA complementary sites. Thus, SeqTar is an effective method for identifying miRNA targets in plants using degradome data sets.

INTRODUCTION

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are non-coding RNAs that regulate the expression of protein-coding genes mainly at the post-transcriptional level in plants and animals (1). In plants, miRNAs are known to induce cleavages of their mRNA targets between the 10th and 11th nucleotides within nearly perfect complementary sites (2,3). This nearly perfect complementarity has extensively been used to predict miRNA targets in plants (2,4–13). However, such sequence complementarity-based methods often produce a large number of false positive predictions, which makes it costly to experimentally validate, e.g. using modified 5′-RACE assay (14).

With the advance of next-generation sequencing technologies, a genome-wide strategy, namely the degradome or PARE (14,15), has been developed to directly profile the mRNA cleavage products induced by small regulatory RNAs, shorthanded as sRNAs that include miRNAs and small interfering RNAs (siRNAs). In this method, the 5′-ends of polyadenylated products of sRNA-mediated mRNA decay are sequenced and subsequently aligned to the cDNA sequences to detect mRNA cleavage sites and quantify the abundance of cleavage products to determine the effects of sRNA-guided gene expression regulation. Currently, CleaveLand (16) is the only publicly available computational method for identifying plant miRNA targets from degradome data (15,17–22). Cleaveland scores sRNA complementary sites based on a mismatch-based scoring scheme (4,6), i.e. (i) a mismatch in an sRNA complementary sites is given a score of 1 and a G:U pair is given a score of 0.5; (ii) a mismatch or a G:U pairs in the core region from 2 to 13 nt receives a double score (6,15); (iii) neither mismatch nor G:U pair at positions 10 and 11 in a complementary site is allowed (7). Generally, sRNA complementary sites with scores of ≤4 were used in identifying miRNA targets (6,15). In sharp contrast to this restrictive scheme, some miRNA complementary sites with scores of ≥4 can also guide the cleavage of their target transcripts. For instance, ath-miR390 is able to guide the cleavage at its 3′ complementary site of TAS3b transcript despite having a score of 7 (corresponding to 6.5 mismatches) (9,23); ath-miR159a can induce the cleavage of AT5G18100 although their complementary site has a score of 6.5 (corresponding to 4.5 mismatches) (14); miR398-guided cleavage of CCS1 is detected despite having a score of 6 (corresponding to 5.5 mismatches) (19); miR167 can lead to the cleavage of Os06g03830 despite having a mismatch at position 11 (19); and ath-miR173 can lead to the cleavage of AT1G50055 even the position 10 of their binding site is a mismatch (6). These observations suggest that the criteria adopted in CleaveLand are too stringent and omit many genuine targets, and relaxation of current criteria can identify additional novel targets for miRNAs from the degradomes.

In order to fully utilize the large amount of degradome data for identifying miRNA targets particularly those with more mismatches, we developed a novel method called SeqTar (SEQuencing-based sRNA TARget prediction). To reduce the false positive predictions when allowing more mismatches, two P-values were introduced in the method to control the qualities of its predictions. Particularly, the number of mismatches in an sRNA complementary site is assigned a P-value, Pm, based on the shuffled sRNA sequences against randomly chosen target sequences, and the number of reads accumulated at the central region of the sRNA complementary site, the 9–11th nt from the 5′-end of miRNA, is given another P-value, Pv, by a Binomial-test. The reads mapped to the 9–11th nt are named as valid reads.

On two degradome data sets from Arabidopsis (14) and one from rice (19), SeqTar identified 231 and 268 novel sRNA:target pairs with less than 3.5 mismatches and with at least 5 valid reads, respectively. Among these pairs, 103 and 92 sRNA:target pairs have significant numbers of valid reads with Pv < 10−5 in Arabidopsis and rice, respectively. Using a modified 5′-RACE (see ‘Materials and Methods’ section), we experimentally validated six sRNA targets each for Arabidopsis and rice, respectively. Most of these 12 sRNA:target pairs have more than 4 mismatches. More importantly, some of these verified miRNA:target pairs have mismatches or G:U pairs at positions 10 or 11. Furthermore, we identified thousands of sRNA:target pairs that showed strong accumulations of reads in the central regions (Pv < 10−5) but had more than three mismatches in both Arabidopsis and rice. These results demonstrated that SeqTar is an effective method for finding sRNA targets from plant degradome. Our analysis also revealed that more transcripts are cleaved by sRNA guided RISC in both Arabidopsis and rice than previously reported.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Degradome and sequence data sets used

The two Arabidopsis degradome data sets (GSM280226, denoted as WT, and GSM280227, named as xrn4) (14) and one rice degradome data set (GSE17398, called as osa) (19) were downloaded from the NCBI GEO database. Two other studies (18,20) also generated degradome data from rice but both of them produced substantially less reads than the data set of Li et al. (19). Thus, the rice degradome of Li et al. (19) was chosen for analysis.

The cDNA sequences of Arabidopsis and rice were downloaded from the TAIR database (r9, http://www.tair.org) and the Rice Genome Annotation Project (r6.1, http://rice.plantbiology.msu.edu/), respectively. The sequences of TAS3a/b/c of rice were retrieved from the NCBI EST database, under the accession numbers EU293144, AU100890 and CA765877 (19), respectively.

The sequences of mature miRNAs were obtained from the miRBase (24) (version 16, http://www.mirbase.org/) and the unique miRNA sequences were used in the analysis. TasiRNAs of Arabidopsis TAS1 to TAS4 were collected from the Arabidopsis Small RNA Project Database (http://asrp.cgrb.oregonstate.edu). Some Arabidopsis small RNAs derived from PPR genes [reported in (15)] were also used in this study. The rice tasiRNAs were obtained from (19). All small RNA sequences used were provided in Supplementary Table S12.

Sequence alignment

SeqTar used a modified Smith–Waterman algorithm to align an sRNA to a target sequence. Briefly, instead of performing alignments with matched nucleotides, e.g. A-A and C-C, SeqTar found complementary nucleotides, i.e. G-C, A-U and G-U Wobble pairs that had rewards of +6, +4 and +2, respectively, in alignment. The affine gap penalty, i.e. the penalty increasing linearly with the length of gap after the initial gap opening penalty, was used for gap opening (−8) and gap extension (−4). The algorithm gave a penalty of −3 to a known mismatch and a penalty of −1 to a mismatch of unspecified nucleotides (i.e. ‘N’) in mRNAs.

SeqTar next used shuffled sRNA sequences to evaluate predicted sRNA complementary sites, which was a standard way to evaluate predicted binding sites of plant sRNAs (2,4). One hundred dinucleotide shuffled sRNAs were generated for a given sRNA sequence. Each of these shuffled sRNAs was used to predict complementary sites on one target sequence randomly chosen from the pool of all target sequences. Finally, the number of mismatches of these 100 sRNA:target pairs were used to evaluate the P-values of the mismatches, Pm, of the mismatches of sRNA's complementary sites, m, by assuming a Student's t-distribution.

Reads distributions

The unique sequences of a degradome data set were aligned to the transcript (cDNA) sequences with the BLASTN program. Then, the abundance of a matched locus was obtained by averaging the number of a unique sequence to the number of its perfectly matched loci in all transcript sequences. Initially, SeqTar scanned the BLASTN results to obtain the normalized abundance in each position on a transcript. Then, SeqTar calculated the accumulation of reads in the central region of an sRNA complementary site, i.e. reads starting at positions opposite to 9–11 nt region from 5′-end of sRNA. Although major cleavages often took place between the 10th and 11th nt, minor cleavages between 9th and 10th or 11th and 12th nt had also been reported (6,11,25). Among the reads mapped to different positions on the target transcript, some reads could have been generated by sRNA-guided cleavage events and were named as valid reads, v. Thus, it was assumed that the degradation products of a target followed a Binomial distribution, where the reads mapped to the central region of an sRNA complementary site were treated as preferred (positive) samples and other reads as control (negative) ones. The probability of valid reads, Pv, was calculated by Equation 1.

| (1) |

where x = max(n9, n10, n11), n9–n11 were the number of reads mapped to the positions opposite to the 9–11th nt of the sRNA, respectively, n was the total number of reads that were mapped to the whole target sequence, and q was a constant that stands for the probability that a mapped read was from any nucleotide of the target sequence. If no sRNA was involved in the degradation of a target, there was no reason to assume that one position would be more likely to break down than other positions. Therefore, each position of the target sequence was assumed to have the same probability to produce a degradation product by assuming a Uniform distribution on the degradation products of a transcript. Therefore, q in Equation 1 was assigned a value of 1/(l − (r − 1)), where l was the length of the target sequence and r was the length of a degradome read, since the last r − 1 position of the target sequence could not be detected with the sequencing reads. In current implementation of SeqTar, Pv < 10−300 were regarded as 0. It was important to note that although the valid reads, v, were all the reads mapped to the 9–11th positions, Pv was calculated from the largest number of reads of these three positions. This was because Pv was used to evaluate whether the major cleavage position was preferred by the sRNA-guided RISC complex.

The computational steps and outputs of SeqTar

The major steps of SeqTar were shown in Supplementary Methods. All computational steps of SeqTar had been integrated into a whole script whose major steps including SeqTar were implemented with the Java programming language. SeqTar had been used in the Linux operating system and was available for non-commercial purposes upon request.

SeqTar produced six output files: the first listed the sRNA:target pairs; the second showed the alignments of sRNA complementary sites; the third provided the MatLab scripts for generating the T-plots of target mRNAs; the fourth gave the number of reads perfectly mapped to target mRNAs; the fifth listed the scores of shuffled sRNAs used to evaluate the Pm values; and the last provided the potential novel sRNA candidates. As suggested by German et al. (14), SeqTar predicted a potential sRNA if an accumulation of reads was found at a specific position, named as a peak, on a target but no input sRNAs contributed to this accumulation. Additional details of outputs were given in the Supplementary Methods. The first file consisted of 33 columns to show the information of a miRNA:target pair, such as the number of valid reads, the P-value of valid reads Pv, the number of mismatches, the P-value of mismatches Pm and the percentage of valid reads. A detailed description of these columns were also given in Supplementary Methods.

Performance evaluation

To evaluate the performance of SeqTar, we compared its prediction results with that reported in the literature. The verified or predicted Arabidopsis sRNA targets (2,4,6,7,9,14,15,26–29) were combined and duplicate pairs were removed and a resulting list of 428 sRNA:target pairs were obtained for Arabidopsis (Supplementary Table S1). A total of 230 of these 428 pairs were validated targets of 28 conserved sRNA families and summarized in Table 1. Similarly, 458 sRNA:target pairs of rice (Supplementary Table S2) were obtained from the reported results (18–20,28,30–38). Of these, 123 targets of 21 conserved sRNA families were previously validated and summarized in Table 1. We also compared the SeqTar's results with those of the CleaveLand pipeline (16) reported recently in the starBase (39).

Table 1.

The conserved miRNA targets of A. thaliana and O. sativa

| miR family | Target family | A.t. | WT | WT New | xrn4 | xrn4 New | O.s. | osa | osa New |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR156/157 | SBP | 11 | 11 | 0 | 11 | 1(1) | 10 | 10 | 0 |

| miR159/319 | MYB | 7 | 7(5) | 3(3) | 7(5) | 4(4) | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| miR159/319 | TCP | 5 | 5 | 1(1) | 5 | 1(1) | 4 | 4(2) | 0 |

| miR160 | ARF | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 1 |

| miR161 | PPR | 40 | 40(25) | 46(40) | 40(25) | 90(83) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| miR162 | DCL | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| miR163 | SAMT | 6 | 6(6) | 4(4) | 6(2) | 6(5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| miR164 | NAC | 7 | 7(1) | 4(3) | 7(1) | 6(4) | 6 | 6(1) | 18(14) |

| miR165/166 | HD-Zip | 6 | 6 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| miR167 | ARF | 2 | 2 | 1(1) | 2 | 3(3) | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| miR168 | Argonaute | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 6 | 0 |

| miR169 | HAP2 | 7 | 7 | 3(2) | 7 | 3(3) | 8 | 8 | 0 |

| miR170/171 | SCL | 4 | 4(1) | 1 | 4(1) | 1(1) | 5 | 5(2) | 0 |

| miR172 | AP2 | 6 | 6 | 4(4) | 6 | 3(3) | 5 | 5(1) | 4(3) |

| miR173 | TAS1/2 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| miR390/391 | TAS3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| miR393 | F-Box | 5 | 5 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4(1) |

| miR394 | F-Box | 1 | 1 | 11(11) | 1 | 11(11) | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| miR395 | APS | 3 | 3(1) | 0 | 3(1) | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| miR395 | SO2 Transp. | 1 | 1 | 1(1) | 1 | 1(1) | 3 | 3(1) | 0 |

| miR396 | GRF | 7 | 7 | 1 | 7 | 1 | 12 | 12(2) | 0 |

| miR397 | Laccase | 3 | 3 | 3(3) | 3 | 4(4) | 16 | 16(14) | 4(4) |

| miR398 | CSD | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| miR398 | CCS1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| miR399 | PO4 Transp. | 1 | 1(1) | 6(6) | 1(1) | 3(3) | 4 | 4(4) | 7(7) |

| miR399 | E2-UBC | 1 | 1 | 16(16) | 1 | 13(12) | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| miR400 | PPR | 39 | 39(32) | 48(43) | 39(33) | 46(42) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| miR403 | Argonaute | 2 | 1 | 2(2) | 1 | 2(2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| miR408 | Plantacyanin | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 7 | 7(2) | 8(5) |

| miR408 | Laccase | 3 | 3(3) | 0 | 3(3) | 0 | 2 | 2(2) | 1(1) |

| miR444 | MADS-box | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 16(14) |

| miR447 | 2-PGK | 2 | 2(2) | 0 | 2(2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| miR858 | MYB | 5 | 5 | 36(26) | 5(1) | 56(45) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| miR859 | F-Box | 35 | 31(28) | 72(68) | 31(30) | 72(72) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TAS3-siR | ARF | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 5 | 5 | 0 |

| Total | 230 | 225(105) | 264(234) | 225(105) | 328(300) | 123 | 122(31) | 75(49) |

The A.t. and O.s. columns list the number of targets of A. thaliana and O. sativa that were reported in literature, respectively. The WT, xrn4 and osa columns list the number of targets in the A.t. and O.s. column that are predicted by SeqTar in the three data sets, respectively. The WT New, xrn4 New and osa New columns list the number of targets that belong to the same family and are newly predicted by SeqTar. The numbers in parentheses are the number of targets whose miRNA complementary sites are predicted but these miRNA complementary sites have no valid reads. A potential target is counted if it is targeted by at least one member of the miRNA family.

Experimental validation using 5′-RACE assay

The RLM 5′-RACE assay was performed to experimentally validate 19 predicted targets listed in Supplementary Table S13 by using the GeneRacer Kit (Invitrogen). Briefly, total RNA from Arabidopsis and rice were ligated with a 5′-RNA adapter and a reverse transcription was performed using oligodT. The resulting cDNA was used as a template for nested PCR. The first PCR was performed using GeneRacer 5′ primer and a gene-specific primer. The second PCR was performed using GeneRacer 5′ nested primer and a gene-specific nested primer. The amplified products were gel purified, cloned into pGEM T-easy vector and sequenced. Gene-specific primers used in this study were listed in Supplementary Table S13.

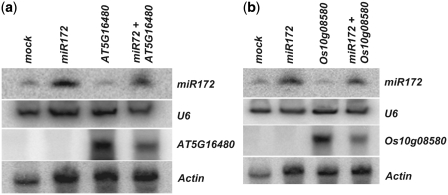

Transient co-expression of miR172 and novel target genes (AT5G16480 and Os10g08580) in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves

We chose miR172 and two of its putative novel target genes, one in Arabidopsis, AT5G16480 and the other in rice, Os10g08580, and experimentally analyzed their transient co-expression in N. benthamiana leaves. Arabidopsis MIR172a (the italic font means a sequence used in a construct) was amplified using locus-specific primers. Similarly, full length of AT5G16480 and partial gene product of Os10g08580 (∼600 bp) harboring miR172 complementary sites were amplified from Arabidopsis and rice, respectively (primer sequences were listed in Supplementary Table S17). The clones were initially cloned into TA-vector and sequenced and confirmed that no mutations/errors were introduced during the process. Then the genes were inserted into XbaI and KpnI sites of binary vector pBIB under the control of super promoter. The constructs harboring Ath-MIR172a, AT5G16480 or Os10g08580 were transformed into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101 and these cell cultures were infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves as described by English et al. (40). For co-expression analysis, equal amount of Agrobacterium culture containing Ath-MIR172a and AT5G16480 or Os10g08580 were mixed before infiltration into N. benthamiana leaves.

RESULTS

Summary of the predictions from SeqTar

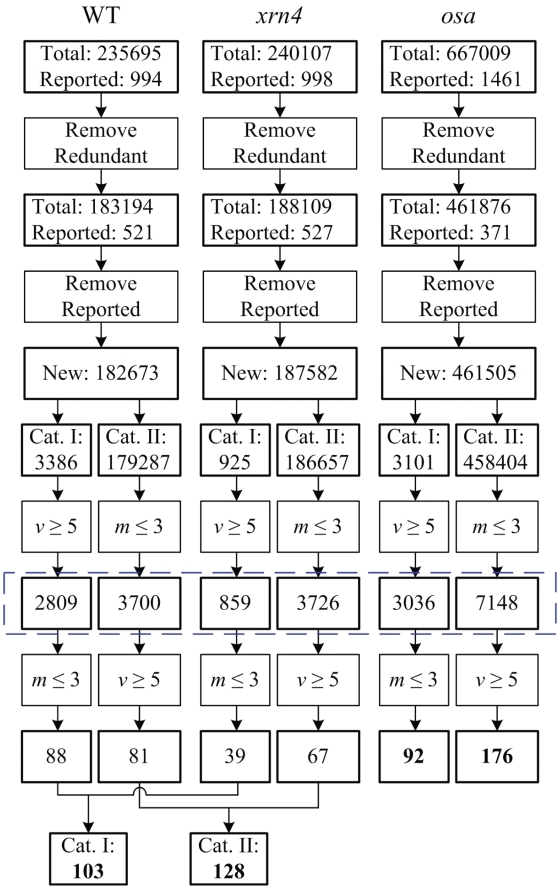

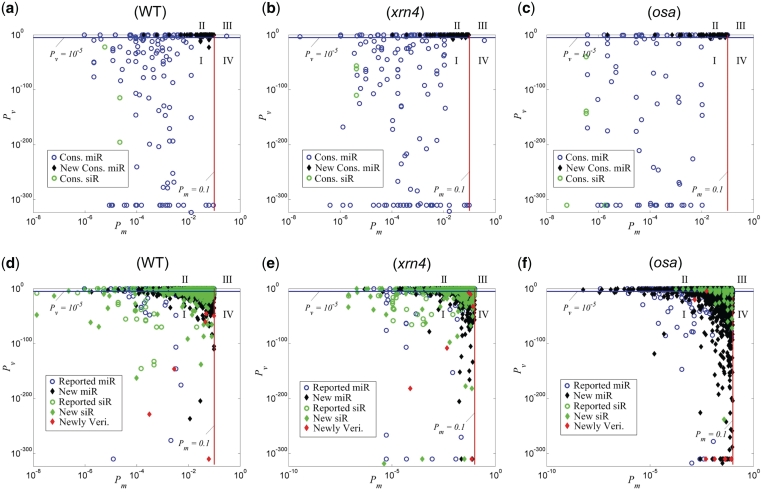

We analyzed three degradome data sets, two from Arabidopsis (WT and xrn4) and one from rice (osa) (see ‘Materials and Methods’ section) using SeqTar. SeqTar predicted a total of 235 695, 240 107 and 667 009 sRNA:target pairs in the WT, xrn4 and osa data sets, respectively (Figure 1). After removing duplicate and redundant pairs of different mature miRNAs and alternatively spliced transcripts, 183 194, 188 109 and 461 877 sRNA:target pairs were obtained from the WT, xrn4 and osa data sets, respectively (see Supplementary Methods for details). In addition to the 428 Arabidopsis sRNA:target pairs summarized in Supplementary Table S1, Howell et al. (9) reported that ath-miR161-1, ath-miR161-2, ath-miR400 and seven tasiRNAs derived from athTAS1/2 transcripts can regulate a total of 40 PPR transcripts. We thus did not treat the pairs consisting of these 10 sRNAs and these 40 PPR transcripts from the non-redundant pairs as novel targets in Figure 1. After removing the reported pairs, there were 1 82 673, 1 87 582 and 4 61 505 newly identified pairs in the WT, xrn4 and osa data sets, respectively. These pairs were classified into Category I (with Pm < 0.1 and Pv < 10−5) and Category II (with Pm < 0.1 and Pv ≥ 10−5). Many new sRNA:target pairs, specifically 3386, 925 and 3101 pairs in the WT, xrn4 and osa datasets respectively, belonged to Category I (see Figure 2d–f). These numbers were further reduced to 2809, 859 and 3036 (in Supplementary Tables S6–S8) after considering a minimum of five valid reads as a cutoff. Some pairs in Category I (i.e. 88, 39 and 92 in WT, xrn4 and osa, respectively) only had ≤3 mismatches. After combining results from the WT and xrn4 data sets, we found 103 novel Category I sRNA:target pairs with ≤3 mismatches for Arabidopsis. Many newly identified targets (solid diamonds in Figure 2d–f) in Category I had >3 mismatches, but had strong accumulations of valid reads as indicated by their Pv values. Among these identified targets, 4 and 6 with >3 mismatches from Arabidopsis and rice, respectively, were validated (red solid diamonds in Figure 2d–f; Figures 3 and 4; Tables 2 and 3).

Figure 1.

The numbers of predicted targets. m and v stand for the number of mismatches and the number of valid reads, respectively. Cat. I and Cat. II are the Category I and Category II sRNA:target pairs classified by their Pv and Pm-values, respectively, as shown in Figure 2. Boxes with thin and thick edges are operations and results, respectively. ‘Reported’ means the number of miRNA:target pairs reported in literature, as summarized Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. The predicted targets in the blue dashed box are used to find combinatorially regulated targets. Cat. I and Cat. II miRNA:target pairs in this box are given in the Supplementary Tables S6–S8 and S14–S16 for the WT, xrn4 and osa data sets, respectively.

Figure 2.

The Pv and Pm of sRNA:targets pairs. (a) The sRNA:targets pairs of WT and WT New in Table 1. (b) The sRNA:targets pairs of xrn4 and xrn4 New in Table 1. (c) The sRNA:target pairs of osa and osa New in Table 1. (d) The new sRNA:target pairs in the WT data set that are not shown in (a). (e) The new sRNA:target pairs in the xrn4 data set that are not shown in (b). (f) The new sRNA:targets in the osa data set that are not shown in (c). Circles stand for reported sRNA:target pairs, black diamonds stand for newly identified sRNA:target pairs, and red diamonds stand for newly identified sRNA:target pairs that had been verified with the RLM 5′-RACE experiments, respectively. Green circles and green diamonds stand for reported siRNA:target and new siRNA:target pairs, respectively. I, II, III and IV are the four Categories of sRNA:target pairs classified by their Pv and Pm values.

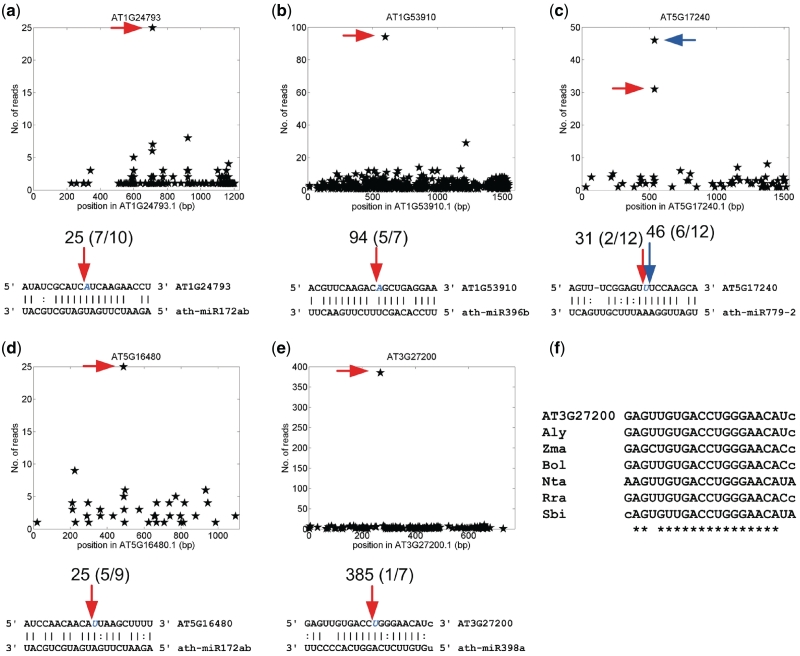

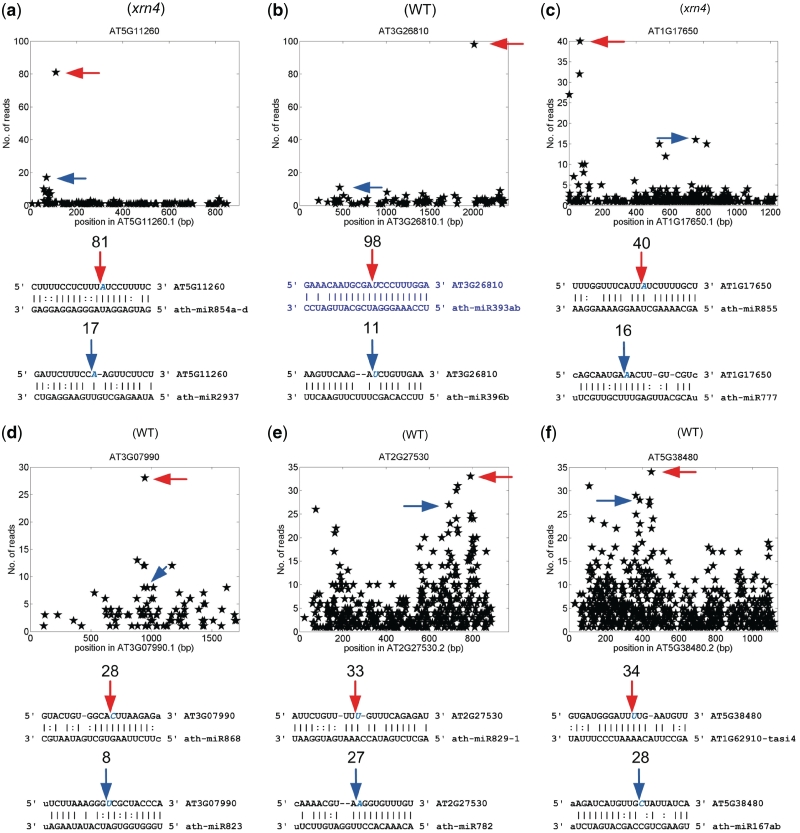

Figure 3.

The experimentally verified novel miRNA targets of Arabidopsis. (a) ath-miR172ab:AT1G24793. (b) ath-miR396b:AT1G53910. (c) ath-miR779-2:AT5G17240. (d) ath-miR172ab:AT5G16480. (e) ath-miR398a:AT3G27200. (f) The conservation of ath-miR398a site on AT3G27200. Abbreviated names, Aly, Zma, Bol, Nta, Rra and Sbi stand for A. lyrata PID:484503, Zea mays DQ245243, Brassica oleracea DK501936, N. tabacum FS399926, Raphanus raphanistrum subsp. maritimus FD965811, and Sorghum bicolor Sb05g007160, respectively. In Part (a) to (e), the x-axis is the position on the transcript, and y-axis is the number of reads detected from a position. The arrows in the upper parts correspond to the positions pointed by the arrows of the same colors in the lower parts. The numbers above the arrows are the number of reads detected at those positions on the WT data set. The numbers in the parenthesis are the cleavage frequencies determined by the RLM 5′-RACE experiments.

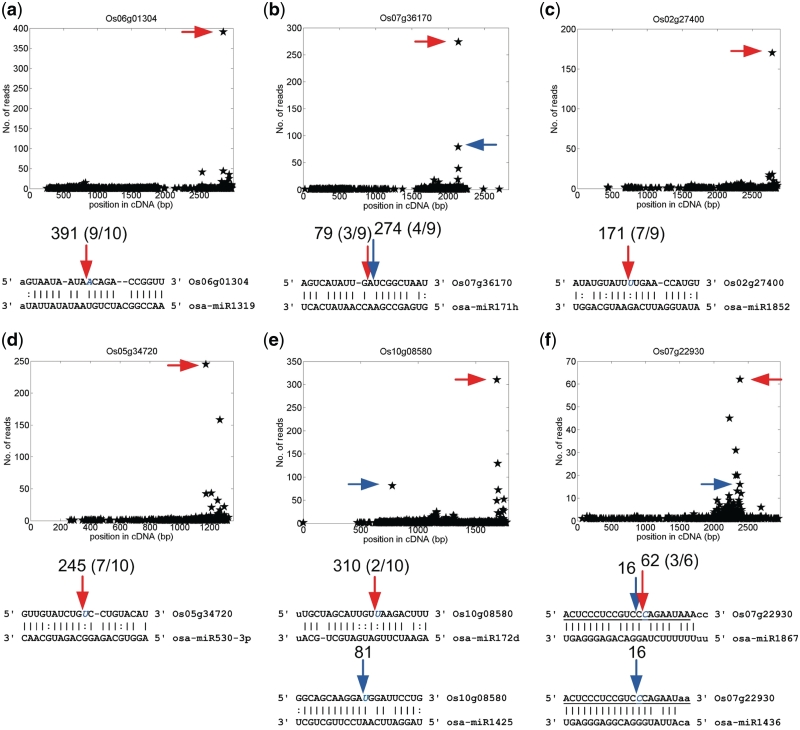

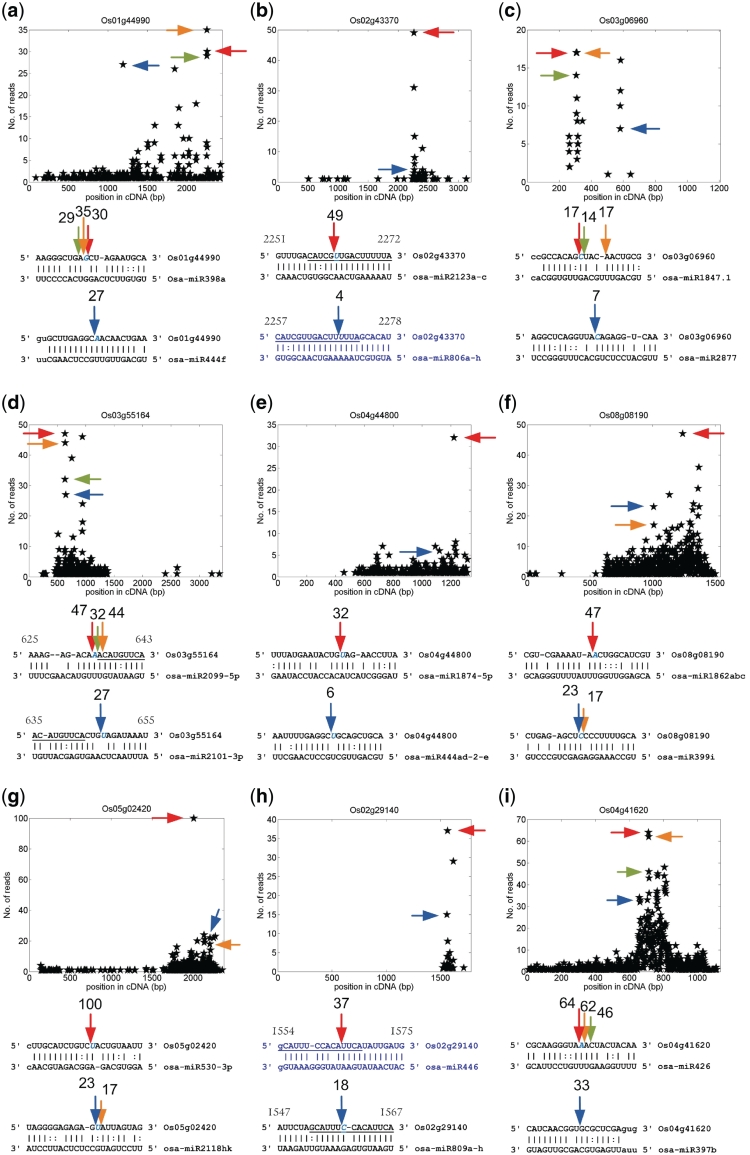

Figure 4.

The experimentally verified novel miRNA targets of rice Oryza sativa. (a) osa-miR1319:Os06g01304. (b) osa-miR171h:Os07g36170. (c) osa-miR1852:Os02g27400. (d) osa-miR530-3p:Os05g34720. (e) osa-miR172d:Os10g08580 and osa-miR1425:Os10g08580. (f) osa-miR1867:Os07g22930 and osa-miR1436:Os07g22930. For details refer to the legend of Figure 3. The T-plots and numbers of reads are the results on the osa data set. In part (f), the underlined nucleotides indicate the overlapped regions of different miRNA binding sites.

Table 2.

Some newly found sRNA targets of A. thaliana that belong to Category I

| sRNA | Locus | M | VR | Pv | Percentage | Target (cDNA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ath-miR157a-c | AT5G24870 | 5 | 12 | 1.3E-13 | 10.9 | Zinc finger (C3HC4-type) family protein |

| ath-miR158a | AT1G01160 | 3.5 | 12 | 1.9E-10 | 3.0 | GIF2; transcription co-activator-related |

| ath-miR167ab | AT1G17870 | 4 | 22 | 3.0E-16 | 9.2 | ATEGY3; Ethylene-Dependent Gravitropism-Deficient And Yellow-Green-Like 3 |

| ath-miR172ab | AT1G24793 | 4.5 | 34 | 2.8E-46 | 17.7 | UDP-3-O-[3-hydroxymyristoyl] N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase |

| ath-miR172ab | AT5G16480 | 5 | 30 | 4.4E-50 | 22.9 | Tyrosine-specific protein phosphatase family protein |

| ath-miR172b* | AT1G60480 | 3.5 | 11 | 9.0E-11 | 9.1 | Pseudogene, putative ADP-ribosylation factor |

| ath-miR172cd | AT1G51405 | 5 | 7 | 1.3E-17 | 31.8 | Myosin-related |

| ath-miR393ab | AT1G49260 | 4 | 9 | 1.0E-18 | 18.4 | Unknown protein |

| ath-miR396a | AT4G32250 | 3.5 | 6 | 3.3E-10 | 3.4 | Protein kinase family protein |

| ath-miR396b | AT1G53910 | 3 | 96 | 1.1E-146 | 5.9 | RAP2.12; transcription factor |

| ath-miR396b | AT2G29160 | 4 | 13 | 4.6E-35 | 39.4 | Pseudogene, similar to tropinone reductase I |

| ath-miR396b | AT3G14110 | 2.5 | 24 | 1.4E-38 | 7.2 | FLU (Fluorescent In Blue Light) |

| ath-miR396b | AT5G43060 | 2 | 36 | 7.5E-79 | 19.8 | Cysteine proteinase, putative / thiol protease |

| ath-miR398a | AT2G29560 | 3.5 | 6 | 1.2E-09 | 3.5 | Enolase, putative |

| ath-miR398a | AT3G27200 | 4.5 | 485 | 0.0E+00 | 73.6 | Plastocyanin-like domain-containing protein |

| ath-miR400 | AT2G33860 | 4.5 | 82 | 3.1E-124 | 9.1 | ARF3; transcription factor |

| ath-miR413 | AT4G37730 | 4 | 7 | 4.6E-14 | 12.7 | AtbZIP7; transcription factor |

| ath-miR414 | AT3G01260 | 3.5 | 12 | 3.0E-36 | 85.7 | Aldose 1-epimerase |

| ath-miR414 | AT3G48470 | 4 | 11 | 3.0E-24 | 16.4 | EMB2423; EMBRYO DEFECTIVE 2423 |

| ath-miR414 | AT5G10400 | 4 | 206 | 4.6E-205 | 20.9 | Histone H3 |

| ath-miR415 | AT5G17580 | 1.5 | 15 | 5.5E-11 | 4.2 | Phototropic-responsive NPH3 family protein |

| ath-miR420 | AT2G31945 | 4.5 | 13 | 7.7E-23 | 19.7 | Unknown protein |

| ath-miR776 | AT5G50565 | 4.5 | 411 | 0.0E+00 | 19.8 | Unknown protein |

| ath-miR779-2 | AT5G17240 | 4.5 | 31 | 3.4E-61 | 13.7 | SDG40 (SET DOMAIN GROUP 40) |

| ath-miR780-1 | AT1G53650 | 3.5 | 7 | 6.8E-13 | 8.3 | CID8; RNA binding / protein binding |

| ath-miR783 | AT1G51420 | 4 | 11 | 3.8E-14 | 19.0 | SPP1; Sucrose-Phosphatase 1 |

| ath-miR828 | AT3G02940 | 5 | 6 | 2.9E-12 | 13.0 | AtMYB107; transcription factor |

| ath-miR829-2 | AT4G13120 | 3.5 | 6 | 2.3E-12 | 6.8 | Transposable element gene |

| ath-miR831 | AT3G27290 | 4.5 | 8 | 6.1E-19 | 19.5 | F-box family protein-related |

| ath-miR833-3p | AT1G71160 | 5 | 6 | 1.5E-13 | 17.1 | KCS7; 3-Ketoacyl-Coa Synthase 7 |

| ath-miR834 | AT1G77095 | 5 | 6 | 4.1E-13 | 16.2 | Transposable element gene |

| ath-miR834 | AT5G13680 | 4.5 | 26 | 1.0E-35 | 9.8 | ABO1; ABA-Overly Sensitive 1, transcription elongation regulator |

| ath-miR835-5p | AT1G71490 | 3.5 | 6 | 1.2E-15 | 19.4 | PPR protein |

| ath-miR847 | AT1G01750 | 4.5 | 7 | 3.1E-14 | 21.2 | ADF11 (Actin Depolymerizing Factor 11) |

| ath-miR850 | AT1G30500 | 5 | 14 | 6.7E-20 | 15.6 | NF-YA7; transcriptional repressor (factor) |

| ath-miR850 | AT3G50390 | 5 | 6 | 2.3E-14 | 22.2 | Transducin/WD-40 repeat family protein |

| ath-miR854a-d | AT1G01490 | 3.5 | 51 | 1.4E-64 | 5.1 | Heavy-metal-associated domain-containing protein |

| ath-miR858 | AT3G62610 | 3.5 | 11 | 5.2E-11 | 7.5 | ATMYB11; transcription factor |

| ath-miR858 | AT5G60890 | 3.5 | 10 | 5.6E-13 | 11.9 | MYB34; transcription factor |

| ath-miR860 | AT5G26030 | 0.5 | 7 | 2.7E-06 | 3.8 | FC1 (ferrochelatase 1); ferrochelatase |

| ath-miR870 | AT1G06190 | 3 | 10 | 2.0E-13 | 3.2 | TP binding / ATPase |

| ath-miR1887 | AT1G52827 | 2.5 | 16 | 9.2E-13 | 3.9 | Unknown protein |

| ath-miR2934 | AT3G13610 | 5 | 6 | 3.2E-15 | 33.3 | Oxidoreductase, 2OG-Fe(II) oxygenase family protein |

| ath-miR2937 | AT3G42670 | 5 | 6 | 4.8E-15 | 12.0 | CHR38, CLSY; DNA binding |

| ath-miR3434 | AT1G74420 | 4 | 5 | 1.35E-10 | 10.2 | FUT3 (fucosyltransferase 3) |

| ath-miR3434 | AT1G67970 | 4 | 5 | 1.55E-10 | 11.9 | AT-HSFA8; DNA binding / transcription factor |

| ath-miR3434* | AT1G34355 | 3.5 | 7 | 6.49E-15 | 4.7 | Forkhead-associated domain-containing protein |

| ath-miR3440b-3p | AT1G04830 | 5 | 29 | 1.37E-33 | 4.1 | RabGAP/TBC domain-containing protein |

| ath-miR3932ab | AT1G26730 | 5 | 13 | 3.29E-20 | 10.9 | EXS family protein |

| ath-miR3932ab | AT2G30620 | 4 | 81 | 1.55E-152 | 12.4 | Histone H1.2 |

| ath-miR3933 | AT1G77330 | 4.5 | 6 | 8.48E-18 | 75.0 | 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylate oxidase |

| ath-miR3933 | AT1G08980 | 5 | 41 | 2.69E-57 | 4.4 | AMI1 (amidase 1); amidase/ hydrolase |

| ath-miR4228 | AT4G37020 | 5 | 24 | 9.18E-44 | 14.6 | Unknown protein |

| ath-miR4239 | AT1G70830 | 4.5 | 151 | 4.92E-134 | 2.9 | MLP28 (MLP-LIKE PROTEIN 28) |

| ath-miR4239 | AT1G70250 | 4.5 | 6 | 2.37E-13 | 10.2 | Receptor serine/threonine kinase |

| TAS1a_D4(+) | AT3G06940 | 3 | 6 | 2.6E-11 | 4.4 | Transposable element gene |

| TAS1a_D9(-) | AT4G14510 | 3.5 | 8 | 2.9E-14 | 3.4 | RNA binding |

| TAS1c_D6(-) | AT2G39681 | 2 | 174 | 3.9E-229 | 5.4 | TAS2; other RNA |

| TAS2_D9(-) | AT2G39681 | 0 | 261 | 4.36E-319 | 8.5 | TAS2; other RNA |

| TAS3c_D4(+) | AT2G19260 | 4.5 | 6 | 4.6E-13 | 9.1 | ELM2 domain-containing protein; PHD finger |

| AT1G62910-tasi4 | AT4G16570 | 2.5 | 8 | 1.6E-13 | 6.3 | PRMT7; protein Arginine methyltransferase 7 |

The Columns, M, VR, Pv and Percentage, mean the mismatches in the sRNA complementary sites, the number of valid reads, the P-value of valid reads, and the percentage of valid reads. In the Target column, PPR protein stands for pentatricopeptide (PPR) repeat-containing protein. The sRNA:target pairs that are verified by the 5′-RACE assay are shown in bold face. The VR, Pv and Percentage values are calculated from either the WT or the xrn4 data set where the larger accumulation of valid reads is found.

Table 3.

Some newly found sRNA targets of Oryza sativa that belong to Category I

| sRNA | Locus | M | VR | Pv | (%) | Target (cDNA) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR159c | Os03g08480 | 5 | 50 | 5.2E-38 | 5.3 | rho termination factor, N-terminal domain containing protein |

| miR168b | Os01g05900 | 4.5 | 35 | 5.6E-14 | 5.5 | Core histone4 H2A/H2B/H3/H4 domain containing protein |

| miR171h | Os07g36170 | 4.5 | 392 | 0.0E+00 | 28.8 | Chitin-inducible gibberellin-responsive protein |

| miR171i | Os01g72250 | 5 | 28 | 2.2E-35 | 8.2 | Uridine 5-monophosphate synthase |

| miR171i | Os03g54100 | 5 | 50 | 7.5E-36 | 6.2 | Potassium channel protein |

| miR172d | Os04g22270 | 5 | 54 | 4.2E-72 | 5.4 | Expressed protein |

| miR172d | Os10g08580 | 5 | 319 | 0.0E+00 | 11.4 | FAD binding domain of DNA photolyase domain containing protein |

| miR319a | Os03g34280 | 4.5 | 20 | 9.9E-14 | 5.8 | Expressed protein |

| miR398a | Os06g42540 | 4.5 | 38 | 2.2E-26 | 10.1 | Expressed protein |

| miR415 | Os02g22280 | 3.5 | 18 | 4.7E-28 | 8.4 | Retrotransposon protein, unclassified |

| miR415 | Os07g42354 | 4.5 | 14 | 1.2E-24 | 5.6 | PPR repeat domain containing protein |

| miR417 | Os09g31506 | 4.5 | 37 | 4.1E-29 | 6.1 | Dihydroflavonol-4-reductase |

| miR419 | Os04g46990 | 5 | 14 | 5.0E-22 | 6.3 | cis-zeatin O-glucosyltransferase |

| miR439a-j | Os04g47820 | 4.5 | 19 | 2.5E-10 | 14.4 | Expressed protein |

| miR444bc-1 | Os03g23050 | 4.5 | 17 | 3.1E-26 | 11.4 | Expressed protein |

| miR444bc-1 | Os07g32460 | 4 | 48 | 1.5E-46 | 6.9 | src homology-3 domain protein 3 |

| miR444bc-2 | Os02g35480 | 4.5 | 26 | 4.6E-42 | 6.3 | Expressed protein |

| miR446 | Os09g27500 | 5 | 19 | 4.8E-42 | 22.1 | Cytochrome P450 |

| miR446 | Os09g30050 | 4 | 19 | 3.6E-34 | 27.9 | Expressed protein |

| miR528 | Os06g01720 | 3.5 | 17 | 1.3E-23 | 15.0 | Expressed protein |

| miR530-3p | Os01g52920 | 5 | 178 | 8.2E-294 | 7.7 | Expressed protein |

| miR530-3p | Os05g02420 | 4.5 | 108 | 1.8E-181 | 7.4 | Expressed protein |

| miR530-3p | Os05g34720 | 3.5 | 287 | 0.0E+00 | 25.5 | Transcriptional regulator |

| miR807a-c | Os02g26660 | 5 | 23 | 6.0E-20 | 9.0 | Exonuclease |

| miR808 | Os10g26720 | 2.5 | 44 | 8.2E-40 | 12.9 | Exonuclease |

| miR809a-h | Os02g29140 | 1.5 | 18 | 2.8E-29 | 12.1 | Ankyrin, putative, expressed |

| miR809a-h | Os04g45665 | 3 | 19 | 1.3E-24 | 28.8 | Expressed protein |

| miR810b-1 | Os12g02040 | 5 | 33 | 3.3E-39 | 5.0 | Hypoxia-responsive family protein |

| miR818a-e | Os12g31860 | 4.5 | 12 | 3.4E-21 | 31.6 | Ureide permease |

| miR1319 | Os06g01304 | 5.5 | 436 | 0.0E+00 | 20.2 | Spotted leaf 11 |

| miR1423b | Os01g19270 | 5 | 16 | 1.1E-39 | 50.0 | Expressed protein |

| miR1428bcd | Os10g26600 | 3.5 | 15 | 1.7E-11 | 12.9 | Soluble inorganic pyrophosphatase |

| miR1429-3p | Os01g50690 | 4 | 58 | 6.6E-53 | 7.6 | WD domain, G-beta repeat domain containing protein |

| miR1436 | Os01g01520 | 4.5 | 16 | 1.6E-22 | 5.4 | Transferase family protein |

| miR1436 | Os07g22930 | 3 | 27 | 1.3E-20 | 2.3 | Starch synthase |

| miR1437 | Os07g36140 | 5 | 30 | 1.3E-13 | 12.5 | Core histone H2A/H2B/H3/H4 |

| miR1438 | Os06g07100 | 5 | 10 | 1.5E-11 | 11.5 | RING-H2 finger protein |

| miR1439 | Os03g11490 | 4.5 | 62 | 7.9E-88 | 20.7 | Expressed protein |

| miR1851 | Os08g03630 | 5 | 24 | 5.5E-42 | 8.1 | Acyl-activating enzyme 14 |

| miR1852 | Os02g27400 | 4 | 188 | 0.0E+00 | 18.7 | OsFBX49 - F-box domain containing protein |

| miR1857-3p | Os05g33710 | 5 | 53 | 1.1E-60 | 6.4 | WD domain, G-beta repeat domain containing protein |

| miR1857-5p | Os11g03720 | 4.5 | 25 | 5.4E-23 | 16.0 | Expressed protein |

| miR1858ab | Os06g45340 | 4 | 28 | 3.9E-18 | 5.7 | Peptidyl-prolyl cis-trans isomerase, FKBP-type |

| miR1861ekm | Os10g32810 | 5 | 16 | 4.1E-24 | 7.1 | Beta-amylase |

| miR1862d | Os07g22930 | 4 | 9 | 6.2E-05 | 0.8 | Starch synthase |

| miR1872 | Os02g48790 | 5.5 | 99 | 1.0E-123 | 4.9 | AML1, putative, expressed |

| miR2099-5p | Os03g55164 | 4.5 | 123 | 3.2E-81 | 10.0 | OsWRKY4 - Superfamily of TFs having WRKY and zinc finger domains |

| miR2123a-c | Os02g34950 | 1 | 54 | 4.6E-83 | 9.0 | ATP binding protein, putative, expressed |

| miR2862 | Os08g01710 | 4.5 | 19 | 9.4E-26 | 10.7 | GLTP domain containing protein |

| miR2863b | Os04g46730 | 4.5 | 12 | 4.9E-17 | 5.4 | Thioesterase family protein |

| miR2874 | Os12g44350 | 5 | 34 | 1.2E-42 | 7.8 | Actin |

| miR2878-3p | Os02g40900 | 5.5 | 180 | 2.5E-318 | 37.7 | RNA recognition motif containing protein |

| miR2878-5p | Os03g07110 | 5.5 | 18 | 1.3E-46 | 30.0 | Calmodulin-binding protein |

| miR2878-5p | Os11g19100 | 5 | 87 | 1.4E-101 | 5.2 | Retrotransposon protein |

| miR2925 | Os08g03590 | 3.5 | 38 | 9.2E-54 | 10.2 | Expressed protein |

| miR2926 | Os07g33660 | 4 | 43 | 3.1E-51 | 6.3 | Expressed protein |

| miR2926 | Os05g29020 | 4 | 25 | 9.1E-49 | 10.5 | Expressed protein |

| miR2929 | Os03g19240 | 4.5 | 17 | 5.1E-24 | 4.6 | AMP-binding enzyme, putative, expressed |

| miR2930 | Os02g44870 | 4.5 | 73 | 2.7E-34 | 2.6 | Dehydrin, putative, expressed |

| miR2931 | Os10g30951 | 3.5 | 36 | 1.5E-35 | 1.5 | Expressed protein |

For details refer to the legend of Table 2.

Predicted targets in Category II with ≤3 mismatches (3700, 3762 and 7148 in the WT, xrn4 and osa data sets, respectively) may not express or express at low level in the sequenced tissues (Supplementary Tables S14–S16). Nevertheless, 81, 67 and 176 sRNA:target pairs from the WT, xrn4 and osa data sets, respectively, had at least five valid reads. After combining the results from the WT and xrn4 datasets, we had 128 novel targets belonging to Category II with ≤3 mismatches and ≥5 valid reads from Arabidopsis.

Validation of the results from SeqTar

In order to verify that SeqTar functions as expected, we first analyzed its performance on the Arabidopsis and rice degradome data sets for identification of reported sRNA targets. Of the 428 reported targets of Arabidopsis, SeqTar recovered 402 and 405 pairs (a total of 412 when merged) from the WT and xrn4 data set (Supplementary Table S1), respectively, with a Pm threshold of 0.1; the remaining 16 reported targets could be identified with a relaxed Pm threshold. Consequently, SeqTar achieved a sensitivity of 96.3% (412/428) with a Pm threshold of 0.1 in identifying the reported pairs of Arabidopsis. In rice, SeqTar identified 381 out of the 457 reported sRNA:target pairs (Supplementary Table S2), achieving a sensitivity of 83.4% with a Pm threshold of 0.1. After relaxing the Pm threshold, SeqTar could predict 17 additional reported pairs in rice.

We further analyzed SeqTar's capability in identifying of conserved sRNA targets in Table 1. SeqTar successfully found most of these targets, 225/230 for the WT and xrn4 data sets and 122/123 for the osa data set, respectively, as shown in the last row of Table 1. The missing miRNA:target pairs included miR-403:AT1G31290, four miR895:F-Box pairs in Arabidopsis and miR398:CCS1 pair in rice. But these pairs were found with a relaxed Pm. These results indicate that SeqTar is sensitive in identifying conserved sRNA targets.

Comparisons with CleaveLand

We compared the results of SeqTar with those of CleaveLand (16) reported in the starBase (39). The two degradome data sets of ref. (14) and four degradome data sets of ref. (15) from Arabidopsis were combined and used in the starBase. Similarly, in the starBase, rice miRNA target prediction were performed by combining the degradome data sets in refs (18,20). CleaveLand (version 2) (16) was used in the starBase to predict miRNA:target pairs with at least one read from these combined degradome data sets (39).

The duplicate miRNA:target pairs from starBase/CleaveLand, due to individual members of a miRNA family and alternatively spliced target transcripts, were removed to obtain 13 399 and 13 279 unique miRNA:target pairs in Arabidopsis and rice, respectively. The duplicate pairs from SeqTar prediction were also removed; the remaining pairs, collectively named as SeqTar-All, were then compared with CleaveLand's results. Here, SeqTar's results on the WT and xrn4 data sets were combined to form its results for Arabidopsis. In order to compare the ability of SeqTar for finding miRNA:target pairs with valid reads, we also compared CleaveLand's results to the pairs with at least one valid read predicted by SeqTar, named as SeqTar-VR. Then, the results of CleaveLand and SeqTar were further checked against the reported pairs summarized in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 to compare their performances on detecting the known targets.

SeqTar has a better performance in identifying the reported pairs than CleaveLand. On Arabidopsis, SeqTar identified 50 more reported miRNA:target pairs with valid reads than CleaveLand even though four more degradome data sets were used in ref. (15) (Table 4). On rice, similarly, SeqTar outperformed CleaveLand by identifying 28 additional reported miRNA:target pairs with valid reads (Table 4). When taking the pairs without valid reads into account, SeqTar had a significantly better performance than CleaveLand by identifying about 43% and 42% more reported pairs in Arabidopsis and rice, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

The comparisons between the CleaveLand Pipeline and the SeqTar pipeline

| SeqTar-All | SeqTar-VR | starBase/CL | Reported | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabidopsis | |||||

| SeqTar-All | – | 41 020 | 7215 | 412 | 246 227 |

| SeqTar-VR | 41 020 | – | 5966 | 277 | 41 020 |

| starBase/CL | 7215 | 5966 | – | 227 | 13 399 |

| Reported | 412 | 277 | 227 | – | 428 |

| Rice | |||||

| SeqTar-All | – | 76 497 | 7375 | 382 | 487 305 |

| SeqTar-VR | 76 497 | – | 4938 | 218 | 76 497 |

| starBase/CL | 7375 | 4938 | – | 190 | 13 279 |

| Reported | 382 | 218 | 190 | – | 458 |

The number in a cell means the common non-redundant miRNA:target pairs predicted by the methods in the line and the column of the cell. SeqTar-All, SeqTar-VR, starBase/CL and Reported stand for pairs of SeqTar, SeqTar with at least one valid read, starBase/CleaveLand and literature summarized in Supplementary Table S1 (Arabidopsis) and S2 (rice), respectively. SeqTar's results on the WT and xrn4 data sets were combined to form the SeqTar-All and SeqTar-VR in Arabidopsis. The ‘Total’ column listed the total numbers of pairs of SeqTar-All, SeqTar-VR, starBase/CL and Reported.

The numbers of common predictions from SeqTar-All, SeqTar-VR, starBase/CleaveLand, and reported pairs were summarized in Table 4. In both Arabidopsis and rice, ∼54% of CleaveLand's pairs were overlapped with SeqTar-All. The rest pairs of CleaveLand that were not found in SeqTar-All had an average score of 6.7 in both species. We thus speculated that the Pm threshold of 0.1 of SeqTar might be too stringent to identify these pairs. After relaxing Pm to 0.2, SeqTar identified more pairs overlapped with CleaveLand's results: 2004 new pairs in Arabidopsis and 2585 new pairs in rice in addition to those in Table 4.

Conserved miRNAs target additional members of known target gene families

SeqTar's results were analyzed to find whether the conserved miRNAs targeted additional members of the same gene families. Thirty, twenty-eight and twenty-six new targets for the conserved miRNA families had valid reads in the three data sets respectively (see the WT New, xrn4 New and osa New columns of Table 1), suggesting that additional members of these target gene families were also cleaved. These newly found targets generally had more mismatches in their complementary sites (≥4) than those reported, which could explain why these targets could not be identified in previous studies (2,4,6,7,9,14,15,26–29). Details of these newly found targets, along with the previously reported, were listed in Supplementary Tables S3–S5.

We also examined the P-values of the complementary sites and valid reads of these conserved sRNA targets (Figures 2a–c). Most conserved targets have very small Pv values (<10−5) and almost all conserved targets have Pm values <0.1. The only exception was the 3′ targeting sites of miR390 on TAS3b(AT5G49615) with 6.5 mismatches (9,23). A proper threshold of Pv needs to be established in order to remove those targets that only had a few valid reads, which might be random degradation products. Because the Pv values of most conserved sRNA targets with valid reads (106/120, 107/120 and 73/89 for the WT, xrn4 and osa data sets, respectively) were <10−5 (Supplementary Tables S3 to S5, respectively), we used a Pv value of 10−5 to identify reliable sRNA:target pairs, as indicated by the blue lines in Figure 2.

Based on the criteria of Pm = 0.1 and Pv = 10−5, all predicted targets could be grouped into four categories: Category I with Pm < 0.1 and Pv < 10−5, Category II with Pm < 0.1 and Pm ≥ 10−5, Category III with Pm ≥ 0.1 and Pm ≥ 10−5, and Category IV with Pm ≥ 0.1 and Pm < 10−5 (Figure 2). The miRNA:target pairs in Category I were the most reliable among all four categories because this category had both satisfactory complementary sites and enriched valid reads. The pairs in Category II, such as ath-miR163:SAMT in the WT data set, might also be genuine targets but with no or limited valid reads, which resulted in insignificant Pv values. Only one reported pair (miR390:AtTAS3b) belonged to Category III (Figure 2a) and IV (Figure 2b) in the WT and xrn4 data sets, respectively.

We identified additional targets in Category I (Figures 2a–c and Supplementary Tables S3–S5). These targets included seven MYB family members (targeted by miR858, also see Table 2), two PPR members (targeted by miR400) in Arabidopsis (after combining results of the WT and xrn4 data sets), and an F-Box member (Os05g37690, targeted by miR393) in rice. These newly found targets had more than three mismatches when aligned with the respective miRNAs. Some other MYB family transcription factors were reported to be targets of miR828 (41) and miR858 in Arabidopsis (14,15), respectively. Our results suggest that more MYB family members are targets of these two miRNA families (Table 2).

Novel targets of conserved miRNAs and experimental validations

It is known that conserved miRNAs target members of the same gene families (as summarized in Table 1). To identify additional targets for conserved miRNAs and to determine whether non-conserved miRNAs were functional, we chose the top two targets that has the largest number of reads at their complementary sites (with the smallest Pv values) for each sRNA in Arabidopsis and rice, respectively. The obtained pairs were manually inspected based on the number of valid reads and the number of mismatches. The resulted miRNA:target pairs in Arabidopsis and rice were listed in Table 2 and 3, respectively.

As mentioned in the ‘Materials and Methods’ section, we selected a total of 19 predicted targets, 7 from Arabidopsis and 12 from rice, for experimental validation. Of these genes, four were not amplified in the tissue tested, which could be due to low abundance below detectable level. Of the 15 amplified genes, 12 genes were cleaved at the expected sites, as shown in Figures 3, 4 and Supplementary Figure S4e.

Our analyses revealed that conserved miRNAs target new gene families that have more mismatches at the miRNA complementary sites (Tables 2 and 3). For instance, ath-miR398a targets AT3G27200, a plastocyanin-like domain-containing protein, with 4.5 mismatches (Table 2 and Figure 3e). Homologs of this gene in many plant species, but not all, possess miR398 complementary sites (Figure 3f). These results indicated that the miR398 family in some plant species target three conserved gene families, in addition to the two reported families, CSD and CCS1 (Table 1). Ath-miR172ab targets five N-acetylglucosamine deacetylase family transcripts (with 4.5 mismatches, see Supplementary Tables S6 and S7), and one of them (AT1G24793) is validated (Figure 3a); ath-miR172ab targets AT5G16480 (a tyrosine-specific protein phosphatase), which is also validated (with five mismatches, see Figure 3d). Similarly, osa-miR171h:Os07g36170 (a chitin-inducible gibberellin-responsive protein) has 4.5 mismatches and osa-miR172d:Os10g08580 (a FAD binding domain of DNA photolyase domain containing protein) has five mismatches (Table 3), and both are validated (Figure 4b and e). The miR396 family targets the GRF (Growth-Regulating Factor) family (15,18). In our study, we found that ath-miR396 can also regulate RAP2.12, a member of the ERF/AP2 transcription factor family. The miR396b cleavage site on AT1G53910 (RAP2.12) was validated using the 5′-RACE assay although there is a mismatch at position 11 (Figure 3b and Table 2). These examples illustrated that some of the conserved miRNA families can target more than one gene families in Arabidopsis and rice.

As shown in Figures 3d and 4e, AT5G16480 in Arabidopsis and Os10g08580 in rice are miR172 targets. To provide further experimental evidence on the accuracy of SeqTar, we infiltrated A. tumefaciens harboring the ath-miR172a primary transcript and two target genes, one from Arabidopsis (AT5G16480) and the other from rice (Os10g08580), into N. benthamiana leaves for transient co-expression analysis. The result confirmed the expression of miR172 in the mock, miR172, AT5G16480/Os10g08580 and miR172+AT5G16480/Os10g08580 infiltrated leaves. As expected, miR172 accumulation is significantly higher in leaves infiltrated with miR172 and miR172+AT5G16480/Os10g08580 than in leaves infiltrated with mock and AT5G16480/Os10g08580 (Figure 5a and b). miR172 is a highly conserved miRNA in plants, so that the detection of miR172 in mock and AT5G16480/Os10g08580 infiltrated N. benthamiana leaves is not surprising and the detected signal in these cases may also be due to endogenous miR172 in N. benthamiana (Figure 5a and b). Transcripts of AT5G16480 or Os10g08580 have been detected in tobacco leaves infiltrated with the respective constructs. Similarly, these transcripts were also detected in leaves infiltrated with AT5G16480/Os10g08580 along with miR172, but not in mock and miR172 infiltrated leaves (Figure 5a and b). AT5G16480/Os10g08580 expression levels were very high in leaves infiltrated with AT5G16480/Os10g08580 alone, but their levels were substantially reduced in the leaves when miR172 and AT5G16480/Os10g08580 were co-expressed (Figure 5a and b). These results indicated that the targets identified by SeqTar are indeed genuine and miR172 can target and cleave the AT5G16480/Os10g08580 transcripts in Arabidopsis/rice.

Figure 5.

The validation of AT5G16480 and Os10g08580 as targets of miR172 using the transient co-expression assay. N. benthamiana leaves were infiltrated with infiltration medium (mock); Agrobacteria harboring Ath-MIR172a alone (miR172); Agrobacteria harboring Arabidopsis transcript AT5G16480/rice transcript Os10g08580 alone (AT5G16480/Os10g08580); co-expression Ath-MIR172a and target genes (miR172+AT5G16480/miR172+Os10g08580). For the co-expression, equal amount of Agrobacterium culture containing Ath-MIR172a and AT5G16480 or Os10g08580 were mixed before infiltration into N. benthamiana leaves. U6 and actin are served as loading controls for miR172 and target gene (AT5G16480 or Os10g08580) detection, respectively. (a) The validation of AT5G16480. (b) The validation of Os10g08580.

Identification of new targets of non-conserved miRNAs and siRNAs

Many non-conserved miRNAs in Arabidopsis and rice were found to have cleavable targets, e.g. ath-miR779-2:AT5G17240 (Figure 3c), ath-miR3932b:AT2G30620, ath-miR3933:AT1G08980, and ath-miR4239:AT1G70830 (Table 2) and osa-miR1319:Os06g01304 (Figure 4a), osa-miR1852:Os02g27400 (Figure 4c), osa-miR2878-3p:Os02g40900 and osa-miR2878-5p:Os11g19100 (Table 3). Some of the pairs, such as ath-miR860:AT5G26030 with 0.5 mismatches (Table 2) and osa-miR2123a-c:Os02g34950 with 1 mismatch (Table 3), were highly complementary. Unlike the conserved miRNAs targeting many transcription factors, a few transcription factors were identified as targets of non-conserved sRNAs in Arabidopsis and rice. As listed in Table 2, only seven targets in Arabidopsis, i.e. ARF3 (AT2G33860, targeted by miR400), bZIP7 (AT4G37730, targeted by miR413), MYB107 (AT3G02940, targeted by miR828), NF-YA7 (AT1G30500, targeted by miR850), MYB11 (AT3G62610, targeted by miR858), MYB34 (AT5G60890, targeted by miR858) and HSFA8 (AT1G67970, targeted by miR3434), are transcription factors.

In rice, a non-conserved miRNA osa-miR530-3p targeted Os05g34720, a transcription factor, which was also validated in this study (Figure 4d and Table 3). The non-conserved miRNAs, osa-miR1436 and osa-miR1867, target Os07g22930, a starch synthase protein (Figure 4f and Table 3). osa-miR1439 also has a complementary site with 3.5 mismatches on Os07g22930, which has 3 valid reads (Pv = 0.06), at 3 nt upstream of osa-miR1436 complementary site (Figure 4f). Interestingly, our analysis suggest that osa-miR1436 and osa-miR1439 can also combinatorially regulate another starch synthase, Os06g06560 (Supplementary Figure S2). These results suggested that osa-miR1436, osa-miR1439 and probably osa-miR1867 can regulate genes implicated in starch synthesis pathways in rice.

Furthermore, our analysis also suggested that some siRNAs derived from both TAS1/2 and PPR transcripts might also target other transcripts. For examples, TAS1a_D4(+) can target AT3G06940, a transposable element, and AT1G62910-tasi4 (an siRNA derived from AT1G62910) can target AT4G16570, Protein Arginine Methyltranferase 7 (Table 2).

The combinatorial regulations of mRNA targets

In order to investigate potential combinatorial regulations by different miRNA families, we examined the previously reported miRNA:targets pairs (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2) and the pairs in the dashed box of Figure 1 (Supplementary Tables S6–S8 for Category I pairs, and S14–S16 for Category II pairs, respectively). Some of the combinatorially regulated targets are shown in Figures 6 and 7. For instance, AT3G26810 (an F-box family protein) was a known target of ath-miR393 (15,28). Our analysis suggested that AT3G28160 could also be regulated by ath-miR396b (Figure 6b). Zhou et al. (20) reported that osa-miR806 guided cleavage on Os02g43370 (Table S2). We find that osa-miR2123 can also regulate Os02g43370. The complementary sites of osa-miR806 and osa-miR2123 on Os2g43370 are partially overlapping (Figure 7b). Similarly, osa-miR446 can regulate Os02g29140 (19,20) (Supplementary Table S2). Our analysis shows that osa-miR809 can target Os02g29140 transcript with a partially overlapping complementary site (Figure 7h). We also recognize that osa-miR809, osa-miR446 and osa-miR808 combinatorially regulate several other transcripts, such as Os01g15520, Os06g19990, Os08g40440, Os10g26720 and Os12g12950 (Supplementary Table S8), indicating the existence of several common targets of these three miRNAs. Furthermore, AT5G38480 was found to be cleaved by AT1G62910-tasi4 and ath-miR167 (Figure 6f), suggesting a combinatorial regulation resulting from PPR-derived siRNA and miRNA. TAS3 derived siRNAs are known to target ARF3 (AT2G33860) transcript (6,15,26). Additionally, our analysis revealed that ath-miR400 could also target ARF3 transcript but at a different site with 4.5 mismatches (Supplementary Figure S1). These results, together with many other examples in the current study (Figures 6 and 7 and Supplementary Tables S6–S8) suggested that one transcript could be targeted by two or more different sRNA in Arabidopsis and rice.

Figure 6.

The predicted Arabidopsis targets that are combinatorially regulated. (a) AT5G11260. (b) AT3G26810. The blue binding site of ath-miR393ab was a reported site. (c) AT1G17650. (d) AT3G07990. (e) AT2G27530. (f) AT5G38480. For details refer to the legend of Figure 3. WT and xrn4 in parenthesis indicate the sample where the T-plots and number of reads were obtained.

Figure 7.

The predicted rice targets that are combinatorially regulated. (a) Os01g44990. (b) Os02g43370. (c) Os03g06960. (d) Os03g55164. (e) Os04g44800. (f) Os08g08190. (g) Os05g02420. (h) Os02g29140. (i) Os04g41620. For details refer to the legend of Figure 3. The blue sites were published sites, see Supplementary Table S2. In part (b), (d) and (h), the underlined nucleotides indicate the overlapped regions of different miRNA binding sites, and the numbers above start and end of the target sequences are the start and end positions of the binding sites, respectively.

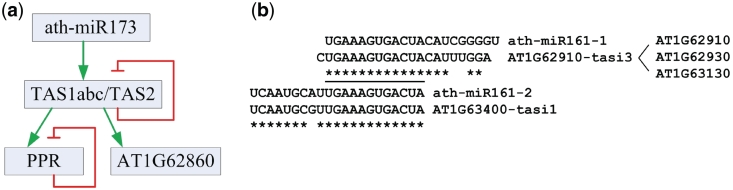

Self- and cross-repression of TAS/PPR transcripts

Mapping 20 nt reads to the TAS transcripts suggested that TAS1a (AT2G27400), TAS1c (AT2G39675) and TAS2 (AT2G39681) transcripts are subjected to cleavages guided by the siRNAs derived from their own precursors (Supplementary Figure S4). In addition to ath-miR173 cleavage sites, all these transcripts are regulated by at least one other siRNA, TAS1c_D6(−). The regulation of TAS2 by TAS1c_D6(−) siRNA was validated using the 5′-RACE assay (Supplementary Figure S4e). TAS1c was regulated by two other siRNAs, TAS1c_D10(−) and TAS1a_D9(−) (Supplementary Figure S4c and d). TAS2 was regulated by three siRNAs derived from its own transcript, TAS2_D6(−), TAS2_D9(−) and TAS2_D11(−) (Supplementary Figure S4e and f). Similarly, cleavage on TAS4 (AT3G25795) was guided by one of the self-derived tasiRNA, TAS4_D4(−) (Pv < 10−4 in the WT data set, see Supplementary Table S9). These results suggested that tasiRNAs derived from TAS1, TAS2 and probably TAS4, regulate and repress their own transcripts.

AT1G62910, a PPR transcript, possessed three target sites for five different sRNAs (Supplementary Figure S5a and b). Among the three sites, one had a major peak and the other two had minor peaks. TAS2_D6(−) could contribute the major peak and the other two minor peaks could be attributed to AT1G62910−tasi3/ath−miR161−1 and AT1G63400−tasi1/ath−miR161−2, where AT1G62910−tasi3 and AT1G63400−tasi1 were miR-161-like siRNA derived from PPR transcripts (Figure 8b). Similar regulations on AT1G62930 and AT1G62860 were also identified (Supplementary Figure S5c–f).

Figure 8.

The self-repression of TAS and PPR transcripts. (a) A schematic view of ath-miR173/TAS1,TAS2/PPR sRNA generating cascade. The green arrows stand for the sRNA-mediated regulation that are required to generate sRNAs. The two red dull arrows stand for the cleavages of transcripts to repress the ever-expanding cascade at the TAS1/2 and PPR level, respectively. (b) The ath-miR161 and ath-miR161-like sRNAs that are derived from the PPR transcripts. The underlined nucleotides are identical in all four sRNAs.

AT1G63080 was targeted by TAS2_D6(−), miR161-1 and miR161-2, and it has been predicted that miR400, TAS2_D9(−) and TAS2_D11(−) can also target AT1G63080 (6). Our analysis confirmed that TAS2_D11(−) indeed induced a major cleavage site on AT1G63080 transcript. TAS2_D6(−) and miR161-1/AT1G62910-tasi3 contribute to another two minor cleavage sites, respectively (see Supplementary Table S10). Sixteen other PPR transcripts, i.e. AT1G06580, AT1G12775, AT1G19720, AT1G26460, AT1G62590, AT1G62860, AT1G62910, AT1G62930, AT1G63080, AT1G63130, AT1G63150, AT1G63330, AT1G63400, AT5G08510, AT5G16640 and AT5G41170, were found to be cleaved by at least two different sRNAs at different positions (Supplementary Table S10). As reported in (9), ath-miR161-1 and ath-miR161-2 can regulate as many as 40 PPR transcripts. Our results suggested that several siRNAs derived from PPR genes, especially the two ath-miR161 like siRNAs, AT1G62910-tasi3 and AT1G63400-tasi1, were involved in self- or cross-repression of many PPR transcripts (see Supplementary Table S10). Our results also suggested that a pseudogene of PPR proteins, AT1G62860, was cleaved by TAS2_D12(−), TAS2_D9(−), ath-miR161-1 and AT1G62910-tasi3 (Supplementary Figure S5e and f). In summary, these results suggest that there are complex combinatorial self- and cross-repression in the ath-miR173/TAS/PPR siRNA regulation cascade.

Self-repression of miRNAs in Arabidopsis

German et al. (14) found that ath-miR172 can self-repress the primary transcript of ath-miR172b. Four other miRNAs, ath-miR390a, ath-miR398b, ath-miR396a and ath-miR396b, also have similar self-repression guided by their own mature miRNAs (14). We found that four more miRNA families, ath-miR163, ath-miR860, ath-miR166f and ath-miR393b (Supplementary Figure S3) also self-repressed their own precursors (Pv < 10−3), suggesting that the self-repression of pre-miRNAs is more prevalent in Arabidopsis than previously reported.

The false discovery rate of SeqTar

We used the method introduced by Storey and Tibshirani (42) to evaluate the False Discovery Rate (FDR) of SeqTar's results. We estimated the FDR and q-values of Pm and Pv, respectively. The q-value is a measure of significance in terms of the FDR (42). The FDR and q-values of all new predictions were <0.05 when the thresholds of Pm and Pv were set to 0.1, except for the Pv of new and Category II predictions of the osa data (Supplementary Table S11). But these measures were <0.05 if a slightly more stringent Pv-value, Pv ≤ 0.07, was used. Because Pm and Pv were calculated independently, FDR and q-values of Pm and Pv were also supposed to be independent. Therefore, it was reasonable to expect the FDR and q of a predicted sRNA:target pair were <0.0025 (0.052) when both Pm < 0.1 and Pv < 0.1 (or Pv < 0.05 for large number of predictions such as the osa data set) were satisfied. This suggested that the FDR of newly predicted sRNA:target pairs were much <0.01 when both Pm < 0.1 and Pv < 0.1 (or Pv < 0.05 for a large number of predictions) were satisfied. The FDRs of the pairs of Category I were <10−4 (in Supplementary Table S11), indicating that the predictions of Category I were highly reliable. The FDR and q-values of Pm of reported pairs were <0.01, which was consistent with the preference of intensively matched complementary sites in the reported pairs. The FDR and q-values of Pv of reported pairs were smaller than pairs in Category II but larger than pairs in Category I (see Supplementary Table S11). In summary, the FDR values suggested that the results of SeqTar were reliable and had a very low ratio of false positives if both Pm and Pv were set to 0.05, or even Pm < 0.1 in all cases and Pv < 0.1 in most cases (see Supplementary Table S11).

Efficiency of SeqTar

SeqTar used about 1000 and 2000 CPU seconds of an Intel Xeon 2.66 GHz 64 bit CPU to search potential targets of one sRNA against all transcripts of Arabidopsis and rice, respectively. In addition to a few efficient supporting steps (see Supplementary Methods), it took a modest number of hours to perform target predictions on all annotated transcript cDNA sequences for all miRNAs and siRNAs in both of these two species on a normal server computer with multiple CPUs.

DISCUSSION

SeqTar's improved performance

In this study, we have demonstrated that SeqTar is a more effective and efficient computational method for identification of miRNA/siRNA targets from the degradome data sets in plants. By relaxing the number of mismatches, SeqTar found many new targets for conserved and non-conserved miRNAs in Arabidopsis and rice. The improved performance of SeqTar could be attributed to three major facts. First, instead of setting a subjective criterion such as the number of mismatches in its prediction, SeqTar used the P-values of mismatches generated with shuffled sRNA sequences. Because different miRNA families have varied number of targets and conserved miRNAs tend to bind to regions with high complementarities in their targets, Pm could have a better capability in differentiating true complementary sites from false ones. It is also better to use Pm-values than a specified number of mismatches for miRNAs of different lengths because longer miRNAs should be able to tolerate a few more mismatches than shorter ones. For example, 24 nt miRNAs such as ath-miR829-1 (Figure 6e), osa-miR1867 (Figure 4f), osa-miR1874-5p (Figure 7e) and osa-miR1862 (Figure 7f) could cleave their targets despite having >5 mismatches in the complementary sites. Second, SeqTar treated mismatches and G:U pairs in different positions of sRNA complementary sites equally. In previous studies, mismatches and G:U pairs in the 2 nt to 13 nt region received more penalties (6,15,16) and were not allowed at positions 10 and 11 (7). However, our results indicated that some sRNA complementary sites with mismatches and G:U pairs at these positions are also subjected to sRNA-guided cleavages. Eight verified miRNA:target pairs (Figures 3a–d and 4a, b, d and e) had at least two mismatches within the regions of the 2–13th nt. Among these eight pairs, osa-miR171h:Os07g36170 and ath-miR396b:AT1G53190 also had a mismatch at position 10 and 11, respectively (in Figures 3b and 4b). Two published work (6,43) also support our findings. Allen et al. (6) verified that ath-miR173 can cleave AT1G50055 (TAS1b) even the positions 10 and 9 of their complementary site are mismatches; Mallory et al. (43) demonstrated that a mutated miR165 complementary site with a mismatch at position 10 can be cleaved. More importantly, SeqTar took advantage of the abundance of valid reads, i.e. reads mapped to the 9–11 nt region, to perform a statistical analysis of sRNA complementary sites. In particular, the Pv values were calculated to evaluate the abundance of valid reads at the predicted cleavage sites. By combining the Pm and Pv-values, SeqTar's sensitivity and specificity were enhanced to outperform the methods that only used sequence information alone. Our results clearly suggest that the existing criteria of predicting targets for sRNA in plants may be too stringent to successfully identify genuine targets with weak complementarities.

Finally, as a rule of thumb for using SeqTar, if Pv < 10−5, a Pm threshold of 0.1 can be used to find miRNA:target pairs with a good sensitivity and reasonable specificity. If Pv ≥ 10−5, it is better to use a stringent Pm value of ≤0.05 (or 0.01), or alternatively to restrict the number of mismatches m ≤ 4 as a criterion as proposed in early studies. For instance, by using Pv < 10−5 and Pm < 0.1, 41.6% and 45.0% reported pairs in Supplementary Table S1 could be identified on the WT and xrn4 data sets, respectively. Then, by using Pm < 0.05 alone, additional 43% pairs in Supplementary Table S1 were identified on both the WT and xrn4 data sets. Similarly, 132 and 245 out of the 458 reported pairs of rice in Supplementary Table S2 could be identified on the osa data set by using the same criteria.

More sRNA targets exist than previously reported

Even with a very strict criterion of Pv < 10−5 and ≤3 mismatches in complementary sites, SeqTar found 103 and 92 novel sRNA targets in Arabidopsis and rice, respectively. Another 128 and 176 novel target sites in Arabidopsis and rice, respectively, had ≤3 mismatches and at least five valid reads. If using Pm < 0.1, instead of restricting the number of mismatches m ≤ 3, and Pv < 10−5, >3000 novel miRNA:target pairs could be detected in both species (see Category I predictions in Figure 1 and Supplementary Tables S6–S8). Our results suggest that several newly identified non-conserved miRNAs are functional. As shown in Supplementary Tables S6–S8 and Figures 6 and 7, as well as Supplementary Tables S14–S16, a small percentage of targets are combinatorially regulated by more than one sRNA in these two species.

sRNA induced self- and cross-repression

The tasiRNAs derived from TAS1a/c and TAS2 may self- and/or cross-target their own transcripts (Figure 8a). Two ath-miR161 like siRNAs (Figure 8b) are derived from AT1G62910, AT1G62930, AT1G63130 and AT1G63400, which are close paralogs of the PPR-P clade proteins (9). As shown in Supplementary Figures S5a–f, they might potentially target their own transcripts and many other PPR transcripts (see Supplementary Table S10). As reported by Howell et al. (9), ath-miR161 might target as many as 40 PPR transcripts, including the 28 genes in the PPR-P clade. These observations suggested that the ath-miR161 like siRNAs derived from these closely related PPR paralogs repressed the ever-enlarging sRNA generation cascade originated from ath-miR173 at the PPR level (Figure 8a). Current model of ath-miR173/TAS/PPR cascade suggests that the ath-miR173 guided cleavage leads to the generation of tasiRNAs on TAS1 and TAS2, and some of these tasiRNAs induce the generation of siRNAs from PPR transcripts. But our analysis suggested that some tasiRNAs repressed their own transcripts at the TAS1 and TAS2 level (Figure 8a), and some siRNAs generated from PPR genes could potentially be involved in the silencing of PPR-P clade transcripts as also reported by Howell et al. (9). Furthermore, some siRNAs derived from both TAS1/2 and PPR transcripts might also target other transcripts. As listed in Table 2, TAS1a_D4(+) targeted AT3G06940, a transposable element, and AT1G62910-tasi4 targeted AT4G16570, Protein Arginine Methyltransferase 7. These results suggested that some siRNAs generated from the ath-miR173/TAS/PPR cascade might also have other targets, similar to the TAS3-siRNAs targeting the ARF family members (Table 1).

As shown in Supplementary Figure S5e and f, our results suggested that a pseudogene of PPR proteins, AT1G62860, was regulated by TAS2_D12(−), TAS2_D9(−), ath-miR161-1 and AT1G62910-tasi3. Poliseno et al. (44) recently found that transcripts produced from pseudogene PTENP1, named as miRNA decoys, regulated the expression level of tumor suppressor gene PTEN by absorbing miRNAs that had complementary sites on both PTENP1 and PTEN transcripts. The case of AT1G62860 demonstrated that the so-called miRNA decoys were also applicable to trans-acting siRNAs, which made the miR173/TAS/PPR pathway even more complicated than previously thought (Figure 8a).

Besides tasiRNAs, our analyses suggested that several additional miRNA families, ath-miR163, ath-miR860, ath-miR166 and ath-miR393 of Arabidopsis thaliana self-repressed their own primary or precursor transcripts, in addition to the ath-miR172, ath-miR390, ath-miR398 and ath-miR396 families reported in ref. (14).

CONCLUSIONS

The contributions of this study are 3-fold. First, it introduced a novel algorithm, called SeqTar, for identifying sRNA-induced cleavages captured in degradomes. Second, SeqTar identified many new sRNA targets in Arabidopsis and rice that could be missed when using stringent criteria. Finally, the use of Pv-value for evaluating the abundance of valid reads is a better means to identify sRNA guided cleavage sites on mRNA targets that have >4 mismatches than the existing criteria. The extra penalties to mismatches in the 2–13 th nt region and disallowing mismatch and G:U Wobble pair at positions 10 and 11 used in the existing criteria may miss these targets. By simultaneously taking into consideration the Pm-value of mismatches and Pv-value of valid reads, the false positive rate of SeqTar was further reduced than the other methods that only used alignment information. Our results suggested the existence of more targets with more mismatches and with mismatches at position 10 or 11. Our study offered novel insights into the principles that sRNAs follow in recognizing and degrading their targets in plants.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online: Supplementary Tables 1–17, Supplementary Figures 1–5 and 7, Supplementary Methods and Supplementary Reference [45].

FUNDING

The research was supported in part by a start-up grant of Fudan University and a grant of the Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (10ZR1403000 to Y.Z.); by NSF-EPSCOR award EPS0814361 and Oklahoma Agricultural Experiment Station (to R.S.); and by NSF (grant DBI-0743797) and NIH (grants R01GM086412 and RC1AR058681 (to W.Z.)

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Limsoon Wong for his enlightening discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell. 2004;116:281–297. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00045-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rhoades MW, Reinhart BJ, Lim LP, Burge CB, Bartel B, Bartel DP. Prediction of plant microRNA targets. Cell. 2002;110:513–520. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00863-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voinnet O. Origin, biogenesis, and activity of plant MicroRNAs. Cell. 2009;136:669–687. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP. Computational identification of plant microRNAs and their targets, including a stress-induced miRNA. Mol. Cell. 2004;14:787–799. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang XJ, Reyes JL, Chua NH, Gaasterland T. Prediction and identification of Arabidopsis thaliana microRNAs and their mRNA targets. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R65. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-9-r65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen E, Xie Z, Gustafson AM, Carrington JC. microRNA-directed phasing during trans-acting siRNA biogenesis in plants. Cell. 2005;121:207–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwab R, Palatnik JF, Riester M, Schommer C, Schmid M, Weigel D. Specific effects of microRNAs on the plant transcriptome. Develop. Cell. 2005;8:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y. miRU: an automated plant miRNA target prediction server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Suppl. 2):W701–W704. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Howell MD, Fahlgren N, Chapman EJ, Cumbie JS, Sullivan CM, Givan SA, Kasschau KD, Carrington JC. Genome-wide analysis of the RNA-DEPENDENT RNA POLYMERASE6/DICER-LIKE4 pathway in arabidopsis reveals dependency on miRNA- and tasiRNA-directed targeting. Plant Cell. 2007;19:926–942. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.050062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moxon S, Schwach F, Dalmay T, MacLean D, Studholme DJ, Moulton V. A toolkit for analysing large-scale plant small RNA data sets. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:2252–2253. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jagadeeswaran G, Zheng Y, Li Y-FF, Shukla LI, Matts J, Hoyt P, Macmil SL, Wiley GB, Roe BA, Zhang W, et al. Cloning and characterization of small RNAs from Medicago truncatula reveals four novel legume-specific microRNA families. New Phytologist. 2009;184:85–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02915.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonnet E, He Y, Billiau K, Van dePeer Y. Tapir, a web server for the prediction of plant microRNA targets, including target mimics. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1566–1568. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xie F, Zhang B. Target-align: a tool for plant microRNA target identification. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:3002–3003. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.German MA, Pillay M, Jeong D-HH, Hetawal A, Luo S, Janardhanan P, Kannan V, Rymarquis LA, Nobuta K, German R, et al. Global identification of microRNA-target RNA pairs by parallel analysis of RNA ends. Nat. Biotechnol. 2008;26:941–946. doi: 10.1038/nbt1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Addo-Quaye C, Eshoo TW, Bartel DP, Axtell MJ. Endogenous siRNA and miRNA targets identified by sequencing of the Arabidopsis degradome. Current Biol. 2008;18:758–762. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.04.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Addo-Quaye C, Miller W, Axtell MJ. CleaveLand: a pipeline for using degradome data to find cleaved small RNA targets. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:130–131. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ma Z, Coruh C, Axtell MJ. Arabidopsis lyrata small RNAs: transient MIRNA and small interfering RNA loci within the Arabidopsis genus. Plant Cell. 2010;22:1090–1103. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.073882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu L, Zhang Q, Zhou H, Ni F, Wu X, Qi Y. Rice microRNA effector complexes and targets. Plant Cell. 2009;21:3421–3435. doi: 10.1105/tpc.109.070938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li Y-F, Zheng Y, Addo-Quaye C, Zhang L, Saini A, Jagadeeswaran G, Axtell MJ, Zhang W, Sunkar R. Transcriptome-wide identification of microRNA targets in rice. Plant J. 2010;62:742–759. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2010.04187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou M, Gu L, Li P, Song X, Wei L, Chen Z, Cao X. Degradome sequencing reveals endogenous small RNA targets in rice (Oryza Sativa l. ssp. Indica) Frontiers Biol. China. 2010;5:67–90. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Addo-Quaye C, Snyder JA, Park YB, Li Y-F, Sunkar R, Axtell MJ. Sliced microRNA targets and precise loop-first processing of MIR319 hairpins revealed by analysis of the Physcomitrella patens degradome. RNA. 2009;15:2112–2121. doi: 10.1261/rna.1774909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pantaleo V, Szittya G, Moxon S, Miozzi L, Moulton V, Dalmay T, Burgyan J. Identification of grapevine microRNAs and their targets using high throughput sequencing and degradome analysis. Plant J. 2010;62:960–976. doi: 10.1111/j.0960-7412.2010.04208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Axtell MJ, Jan C, Rajagopalan R, Bartel DP. A two-hit trigger for siRNA biogenesis in plants. Cell. 2006;127:565–577. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Griffiths-Jones S, Saini HK, vanDongen S, Enright AJ. miRBase: tools for microRNA genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36(Suppl. 1):D154–D158. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP. Computational identification of plant microRNAs and their targets, including a stress-induced miRNA. Molecular Cell. 2004;14:787–799. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.05.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Williams L, Carles CC, Osmont KS, Fletcher JC. A database analysis method identifies an endogenous trans-acting short-interfering RNA that targets the arabidopsis ARF2, ARF3, and ARF4 genes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:9703–9708. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504029102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu G, Park MYY, Conway SR, Wang J-WW, Weigel D, Poethig RS. The sequential action of miR156 and miR172 regulates developmental timing in Arabidopsis. Cell. 2009;138:750–759. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Bartel B. MicroRNAs and their regulatory roles in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2006;57:19–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev.arplant.57.032905.105218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fahlgren N, Jogdeo S, Kasschau KD, Sullivan CM, Chapman EJ, Laubinger S, Smith LM, Dasenko M, Givan SA, Weigel D, et al. MicroRNA gene evolution in Arabidopsis lyrata and Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2010;22:1074–1089. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.073999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jiao Y, Wang Y, Xue D, Wang J, Yan M, Liu G, Dong G, Zeng D, Lu Z, Zhu X, et al. Regulation of OsSPL14 by OsmiR156 defines ideal plant architecture in rice. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:541–544. doi: 10.1038/ng.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miura K, Ikeda M, Matsubara A, Song X-J, Ito M, Asano K, Matsuoka M, Kitano H, Ashikari M. OsSPL14 promotes panicle branching and higher grain productivity in rice. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:545–549. doi: 10.1038/ng.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]