Abstract

Context

Type 2 diabetes is associated with higher bone density (BMD) and, paradoxically, with increased fracture risk. It is not known if low BMD, central to fracture prediction in older adults, identifies fracture risk in diabetic patients.

Objective

Determine if femoral neck (FN) BMD T-score and FRAX score are associated with fracture in older diabetic adults.

Design

Three observational studies: Study of Osteoporotic Fractures, Osteoporotic Fractures in Men, and Health, Aging and Body Composition study.

Setting

Older community-dwelling adults in U.S.

Participants

9,449 women; 7,436 men.

Main outcome measure(s)

Self-reported incident fractures, verified by radiology reports.

Results

Of 770 diabetic women, 84 experienced a hip and 262 a non-spine fracture during mean (SD) follow-up of 12.6 (5.3) years. Of 1,199 diabetic men, 32 experienced a hip and 133 a non-spine fracture during mean follow-up of 7.9 (2.5) years. Age-adjusted hazard ratios (HR) for one unit decrease in FN BMD T-score in diabetic women were 1.88 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1.43–2.48) for hip and 1.52 (95% CI, 1.31–1.75) for non-spine fracture. HRs in diabetic men were 5.71 (95% CI, 3.42–9.53) for hip and 2.17 (95% CI, 1.75–2.69) for non-spine fracture. FRAX score was also associated with fracture risk in diabetic participants. However, for a given T-score and age or FRAX score, diabetic participants had a higher fracture risk than those without diabetes. For a similar hip fracture risk, diabetic participants had a higher T-score than non-diabetic participants. The difference in T-score was 0.59 (95% CI, 0.31–0.87) for women and 0.38 (95% CI, 0.09–0.66) for men.

Conclusions

Among older adults with type 2 diabetes, FN BMD T-score and FRAX score were associated with hip and non-spine fracture risk. However, in these patients, compared with participants without diabetes, fracture risk was higher for a given T-score and age or a given FRAX score.

INTRODUCTION

Prevention of fractures is an important goal in older adults. It is increasingly recognized that those with type 2 diabetes (T2DM), an estimated 17% of older adults in the U.S.,1 have a higher fracture rate.2–6 Preventive identification of those at higher fracture risk is based on bone mineral density (BMD) T-scores, used alone or in the WHO Fracture Risk Algorithm (FRAX).7 However, because T2DM is, paradoxically, associated with higher BMD and increased fracture risk,8 there is concern that these established methods for predicting fractures may not perform adequately in patients with T2DM.9, 10 There is a need to clarify the utility of standard methods for assessing fracture risk in this expanding population of older adults.

There are no prospective studies available on prediction of fracture in those with T2DM using BMD T-scores or FRAX. We utilized data from three prospective observational studies with adjudicated fracture outcomes, the Study of Osteoporotic Fractures, the Osteoporotic Fractures in Men study, and the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study, to assess the associations of BMD T-score and FRAX with hip and non-spine fracture risk in older adults with T2DM. Those using insulin are reported to have a higher fracture risk,3, 6 so our results are stratified by insulin use.

METHODS

Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF)

SOF is a longitudinal study of older white women (N=9,704) at four clinical centers in the U.S. designed to identify risk factors for fracture.11 At baseline (1986–87), diabetes was ascertained based on a self-reported diagnosis, and insulin use was ascertained in those reporting diabetes. Women were queried regarding use of bone-active medications, including oral glucocorticoids. Approximately two years after baseline, hip BMD was measured at Visit 2 by dual energy x-ray absorptiometry (DXA) on 7,959 women. Twenty women were excluded due to missing data on diabetes status, leaving a total of 7,939 women in these analyses. Women were queried about fractures every 4 months by postcard and at clinic visits. Reported fractures were centrally adjudicated and confirmed based on a radiology report or x-ray. In these analyses, only fractures occurring after the hip BMD measurement at Visit 2 are included, from December 1988 through July 2008.

Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS)

MrOS is a longitudinal study of older men (N=5,995) recruited at 6 clinical centers in the U.S., designed to assess risk factors for fracture.12, 13 Diabetes was ascertained at baseline based on a self-reported diagnosis, self-reported use of a diabetes medication, or an elevated fasting glucose (≥126 mg/dl). Participants were asked to identify all prescription medications used in the previous 30 days. Each medication was matched to its ingredient(s) based on the Iowa Drug Information Service (IDIS) Drug Vocabulary (College of Pharmacy, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA). Hip BMD was measured at baseline using DXA on 5,994 men who are included in these analyses. Fractures were ascertained and adjudicated as described above for SOF. These analyses include fractures that occurred between March 2000 and March 2009.

Health, Aging and Body Composition Study (Health ABC)

Health ABC is a longitudinal study of older adults (N=3,075), about 50% white and 50% black, recruited at two clinical centers in the U.S., designed to assess body composition and physical functioning changes in those 70–79 years old.14 Diabetes was ascertained at baseline using the same criteria as MrOS. Participants were asked to identify all prescription medications used in the previous two weeks. Medications were coded as described for MrOS. Hip BMD was measured at baseline using DXA on 3,043 participants. Of these, 78 were excluded because of missing data on diabetes status. These analyses included 1,523 women and 1,442 men. Fractures were adjudicated at the clinical centers based on x-ray confirmation. These analyses include fractures that occurred between April 1997 and June 2007.

In all three studies, race was determined based on self-report. Protocols were approved by the institutional review boards at all institutions involved, and all participants signed an informed consent.

Femoral neck BMD T-score

T-scores included in our models were calculated using gender- and race-specific young adult reference values from NHANES III, the method currently used in the output from clinical densitometers.15 T-scores included in the WHO FRAX (below) were calculated using reference values for white women as required for this algorithm.16

WHO 10-year absolute fracture risk (FRAX score)

In SOF and MrOS, the WHO 10-yr absolute risks of hip and osteoporotic fracture (FRAX scores) were calculated by the WHO Collaborating Center for Metabolic Bone Disease, using the FRAX algorithm (version 3).16–20 The FRAX algorithm includes FN BMD T-score, age, sex, body mass index, previous history of fracture, parental history of hip fracture, current smoking, recent use of corticosteroids, presence of rheumatoid arthritis, and ≥3 alcoholic beverages per day. FRAX scores have not been calculated for Health ABC participants.

Statistical methods

All regression analyses were conducted using Stata Version 11.2 (Stata Corp, College Station, Tx). We used Cox proportional hazards models to estimate the effect of T-score, adjusted for age, or the effect of FRAX score on the hazard of hip and non-spine fracture in those with and without diabetes. We checked for interactions of T-score with age, race and insulin use in those with diabetes, and verified the proportional hazards assumption.

Cox models were also used to estimate the effects of diabetes with and without insulin use on the hazard of hip and non-spine fracture, controlling for age and FN T-score. We did not take incident diabetes into account in these analyses since our focus was on prediction in those with prevalent diabetes. To minimize residual confounding, the effects of age and T-score were flexibly modeled using restricted cubic splines. We checked for interaction between diabetes and both covariates, and verified the proportional hazards assumption. Ten-year cumulative risks were estimated using the baseline survival function, evaluated at 10 years, raised to the power of the relative hazard for each combination of diabetes group, age, and T-score.

Similarly, we used Cox models to estimate the 10-year risk of fracture for women in SOF with and without diabetes, stratified by insulin use, in models controlling for the FRAX 10-year fracture risk score rather than T-score and age. For men, because none of the MrOS participants had 10 years of follow-up, we calculated 8-year risks instead, adjusting the FRAX scores under the assumption that the hazard for fracture is approximately constant.

To estimate the reduction in T-scores equivalent in terms of added fracture risk to having diabetes, we equated the log hazards of fracture for two same-age participants with and without diabetes, then solved for the difference in T-scores, given by the ratio of the coefficient for diabetes to the coefficient for T-score. Confidence intervals for the differences were obtained by the delta method, using the Stata nlcom command. Power to detect associations between T-score or FRAX score and fracture can be evaluated based on the lower limits of the 95% confidence intervals for the hazard ratios (HRs) in Table 2. For interactions between diabetes and T-score, the combined samples provided 80% power in 2-sided tests with a type-I error rate of 5% to detect the following ratios of the age-adjusted T-score HRs in diabetes vs non-diabetes: in women, 1.37 for hip and 1.21 for non-spine fracture, and in men, 1.72 for hip and 1.30 for non-spine fracture. For interactions between diabetes and FRAX score, the minimally detectable ratios of the HRs were slightly higher.

Table 2.

Hazard ratios for the linear effect of femoral neck BMD T-score or FRAX score on hip and non-spine fracture among older adults with and without diabetes in Health ABC, SOF, and MrOS

| Without diabetes | With diabetes | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Fracture site | No. with any fracture | HRa,b (95% CI) | C-index | No. with any fracture | HRa,b (95%CI) | C-index |

| Femoral Neck BMD T-score | |||||||

| Women | Hip | 1117 | 2.23 (2.06, 2.41) | 0.74 | 84 | 1.88 (1.43, 2.48) | 0.72 |

| Non-Spine | 3231 | 1.53 (1.47, 1.60) | 0.62 | 262 | 1.52 (1.31, 1.75) | 0.64 | |

| Men | Hip | 158 | 3.53 (2.84, 4.38) | 0.83 | 32 | 5.71 (3.42, 9.53) | 0.85 |

| Non-Spine | 690 | 1.62 (1.47, 1.77) | 0.64 | 133 | 2.17 (1.75, 2.69) | 0.66 | |

|

| |||||||

| FRAX score | |||||||

| Women | Hip | 825 | 1.06 (1.05, 1.06) | 0.74 | 51 | 1.05 (1.03, 1.07) | 0.70 |

| Non-Spine | 2383 | 1.04 (1.03, 1.04) | 0.62 | 161 | 1.04 (1.02, 1.05) | 0.64 | |

| Men | Hip | 85 | 1.10 (1.08, 1.13) | 0.80 | 16 | 1.16 (1.07, 1.27) | 0.83 |

| Non-Spine | 418 | 1.07 (1.06, 1.08) | 0.65 | 73 | 1.09 (1.04, 1.14) | 0.63 | |

Abbreviation: HR = hazard ratio, CI = confidence interval.

Femoral neck BMD T-score models adjusted for age. HR per 1 unit decrease in T-score. FRAX score models are not adjusted for other variables. HR per 1 unit increase in FRAX score.

Diabetes status did not modify any of the associations (p for interaction>0.10) between FN T-score or FRAX score and fracture risk

RESULTS

Women

FN BMD T-score was higher in T2DM than in non-DM women (Table 1). In SOF and Health ABC, 1,117 non-DM and 84 T2DM women had at least one hip fracture, and 3,231 non-DM and 262 T2DM women had at least one non-spine fracture during an average follow-up of 12.6 (SD 5.3) years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of older adults, stratified by diabetes and insulin use status

| N | SOF (women) | MrOS (men) | Health ABC women | Health ABC men | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NonDM | DM, no ins | DM, ins | NonDM | DM, no ins | DM, ins | NonDM | DM, no ins | DM, ins | NonDM | DM, no ins | DM, ins | |

| 7406 | 442 | 78 | 5113 | 801 | 80 | 1273 | 190 | 60 | 1124 | 264 | 54 | |

| BASELINE* | ||||||||||||

| Components of FRAX score | ||||||||||||

| Age, yr | 73.4 (5.1) | 73.7 (4.9) | 73.4 (5.0) | 73.6 (5.9) | 73.8 (5.6) | 73.3 (5.1) | 73.5 (2.9) | 73.4 (2.8) | 73.2 (2.9) | 73.7 (2.9) | 73.9 (2.8) | 73.7 (2.9) |

| Race | ||||||||||||

| White | 7386 (99.7) | 440 (99.5) | 78 (100) | 4623 (90.4) | 676 (84.4) | 62 (75.5) | 752 (59.1) | 63 (33.2) | 12 (20.0) | 748 (66.5) | 153 (58.0) | 20 (37.0) |

| Black | - | - | - | 181 (3.5) | 50 (6.2) | 13 (16.3) | 521 (40.9) | 127 (66.8) | 48 (80.0) | 376 (33.5) | 111 (42.0) | 34 (63.0) |

| Asian | 11 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 154 (3.0) | 36 (4.5) | 1 (1.3) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Hispanic | 6 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 99 (1.9) | 26 (3.2) | 2 (2.5) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Other | 3 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 56 (1.1) | 13 (1.6) | 2 (2.5) | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Femoral neck BMD, g/cm2 | 0.65 (0.11) | 0.69 (0.12) | 0.68 (0.12) | 0.78 (0.13) | 0.82 (0.14) | 0.82 (0.14) | 0.68 (0.13) | 0.75 (0.13) | 0.77 (0.13) | 0.78 (0.13) | 0.84 (0.14) | 0.84 (0.16) |

| Weight, kg | 66 (12) | 71 (15) | 73 (14) | 82 (13) | 88 (14) | 90 (14) | 69 (14) | 77 (14) | 78 (15) | 80 (13) | 85 (14) | 85 (13) |

| Height, cm | 159 (6) | 159 (6) | 159 (6) | 174 (7) | 174 (7) | 175 (6) | 160 (6) | 160 (6) | 160 (6) | 173 (7) | 173 (6) | 174 (6) |

| Previous fracture | 3008 (40.8) | 170 (38.6) | 43 (55.1) | 1181 (23.1) | 159 (19.9) | 20 (25.0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Parent fractured hip | 932 (12.6) | 31 (7.0) | 4 (5.1) | 678 (17.4) | 80 (13.4) | 4 (6.7) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Current smoker | 587 (8.0) | 30 (6.8) | 6 (7.9) | 180 (3.5) | 26 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 122 (9.6) | 15 (7.9) | 9 (15.0) | 122 (10.9) | 21 (8.0) | 8 (14.8) |

| Use of glucocorticoids | 321 (4.4) | 17 (3.9) | 3 (4.0) | 108 (2.2) | 16 (2.1) | 2 (2.5) | 35 (2.8) | 6 (3.2) | 3 (5.0) | 18 (1.6) | 3 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| History of rheumatoid arthritis | 482 (6.6) | 33 (7.6) | 7 (9.3) | 250 (4.9) | 58 (7.2) | 7 (8.8) | 99 (10.8) | 19 (13.5) | 4 (10.3) | 50 (6.2) | 18 (9.4) | 5 (11.1) |

| Alcohol 3+ units per day | 224 (3.0) | 24 (5.4) | 2 (2.6) | 449 (8.8) | 61 (7.6) | 5 (6.3) | 159 (12.5) | 9 (4.7) | 1 (1.7) | 296 (26.4) | 52 (19.7) | 3 (5.6) |

| FRAX score | ||||||||||||

| Hip fracture | 5.4 (7.2) | 4.4 (6.8) | 4.1 (4.0) | 2.7 (3.7) | 1.9 (2.6) | 1.7 (2.0) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Osteoporotic fracture | 17.8 (10.0) | 15.7 (9.6) | 17.0 (7.7) | 8.1 (4.9) | 6.8 (3.9) | 6.6 (4.1) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Femoral neck BMD T-score | ||||||||||||

| Mean | −1.8 (0.9) | −1.4 (1.0) | −1.5 (1.0) | −1.2 (0.9) | −0.9 (1.0) | −1.0 (1.0) | −1.7 (0.9) | −1.3 (0.9) | −1.2 (1.0) | −1.3 (0.9) | −1.0 (0.9) | −1.2 (1.1) |

| ≤ −2.5 | 1578 (21.3) | 61 (13.8) | 11 (14.1) | 279 (5.5) | 23 (2.9) | 4 (5.0) | 239 (18.8) | 16 (8.4) | 7 (11.7) | 97 (8.6) | 10 (3.8) | 4 (7.4) |

| FOLLOW-UP† | ||||||||||||

| Any hip fracture | 1059 (14.3) | 62 (14.0) | 8 (10.3) | 128 (2.5) | 17 (2.1) | 2 (2.5) | 58 (4.6) | 10 (5.3) | 4 (6.7) | 30 (2.7) | 10 (3.8) | 3 (5.6) |

| Number of p-yrs | 95,416 | 4,641 | 692 | 38,199 | 5,588 | 547 | 10,939 | 1,490 | 498 | 9,130 | 2,050 | 386 |

| Rate (SE) per 1000 p-yrs | 11.1 (0.3) | 13.4 (1.7) | 11.6 (4.1) | 3.3 (0.3) | 3.0 (0.7) | 3.7 (2.6) | 5.3 (0.7) | 6.7 (2.1) | 8.0 (4.0) | 3.3 (0.6) | 4.9 (1.5) | 7.8 (4.5) |

| Follow-up time (yrs) | 12.9 (5.6) | 10.5 (5.5) | 8.9 (4.9) | 7.5 (1.9) | 7.0 (2.2) | 6.8 (2.3) | 8.6 (2.2) | 7.8 (2.9) | 8.3 (2.5) | 8.1 (2.6) | 7.8 (2.7) | 7.1 (2.9) |

| Any non-vertebral fracture | 3029 (43.9) | 180 (43.7) | 37 (50.0) | 603 (11.8) | 84 (10.5) | 18 (22.5) | 202 (16.0) | 32 (16.9) | 13 (22.4) | 87 (7.7) | 24 (9.1) | 7 (13.0) |

| Number of p-yrs | 71,312 | 3,529 | 496 | 36,446 | 5,341 | 487 | 10,135 | 1,374 | 439 | 8,872 | 1,983 | 380 |

| Rate (SE) per 1000 p-yrs | 42.5 (0.8) | 51.0 (3.8) | 74.6 (12.3) | 16.6 (0.7) | 15.7 (1.7) | 37.0 (8.7) | 19.9 (1.4) | 23.3 (4.1) | 29.6 (8.2) | 9.8 (1.1) | 12.1 (2.5) | 18.4 (7.0) |

| Follow-up time (yrs) | 10.3 (6.1) | 8.6 (5.5) | 6.7 (4.8) | 7.1 (2.2) | 6.7 (2.4) | 6.1 (2.7) | 8.0 (2.7) | 7.3 (3.1) | 7.6 (2.8) | 7.9 (2.8) | 7.5 (2.8) | 7.0 (2.9) |

Values in table are mean (standard deviation) or N (%) except where indicated

Abbreviation: SOF = Study of Osteoporotic Fractures; MrOS = Study of Osteoporosis in Men; Health ABC = Health, Aging and Body Composition Study; NonDM = participants without diabetes; DM, no ins = participants with diabetes, not using insulin; DM, ins = participants with diabetes, using insulin; BMD = bone mineral density; p-yrs = person-years; SE = standard error; NA = not available

For SOF, hip BMD was measured at the first follow-up visit (V2), approximately 2 years after the baseline visit. Other variables listed here are also measurements from V2. Diabetes status was ascertained at the baseline visit.

For SOF, follow-up for fractures starts from V2.

FN BMD T-score was associated with hip and non-spine fracture in diabetic women (Table 2). Since fracture risk varies with age, race and insulin use, we assessed interactions of these variables with T-score. T-score had a greater effect on the hazard of non-spine fracture with older age (p for interaction = 0.04). Otherwise, we found no statistically significant interactions (p>0.10) between T-score and age, race or insulin use. FN BMD T-score was also associated with fracture risk in non-diabetic women, as observed previously in older women,21 with no evidence of interaction of T-score with diabetes status. The ability of FN BMD T-score to predict fracture, based on the C-index, was similar in those with and without diabetes (Table 2). For example, in diabetic women the hazard ratio (HR) for hip fracture for each one unit decrease in T-score was 1.88 (95% CI, 1.43, 2.48). The corresponding C-indexes were 0.72 in diabetic women, and 0.74 in non-diabetic women.

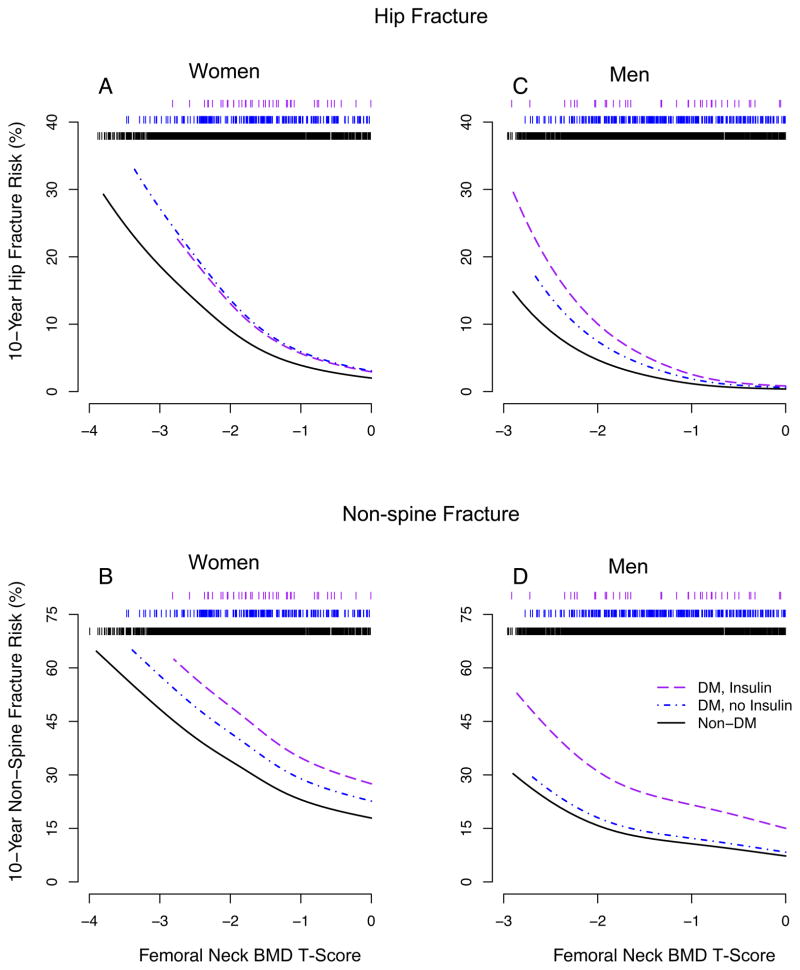

However, for a given T-score diabetic women had a higher risk of hip or non-spine fracture than non-diabetic women of similar age. The increased fracture risk at a given T-score was found for diabetic women using and not using insulin. This is illustrated in the plots of hip (Figure 1A) and non-spine (Figure 1B) fracture risk versus T-score for women aged 75 years, based on our Cox models.

Figure 1. Femoral neck BMD T-score and 10-year fracture risk at age 75 by diabetes and insulin use status.

Ten-year cumulative risks were estimated using the Cox model baseline survival function, evaluated at 10 years, raised to the power of the relative hazard for each combination of diabetes group and T-score at age 75 years. Rug plot at top of figures indicates number of participants (73–77 years old) at each level of T-score. A (N=41, 205, 2604); B (N=41, 196, 2468); C, D (N=40, 306, 1698).

FN BMD T-score is widely used in the diagnosis of osteoporosis.22 In diabetic women, interpretation of a T-score has to consider the higher risk of fracture associated with diabetes (Figure 1). To assist with this interpretation, Table 3 provides the average difference in T-score, comparing diabetic and non-diabetic women with a similar fracture risk. For hip fracture, the mean difference in T-scores, comparing women with and without diabetes who have the same fracture risk, was 0.59 (95% CI, 0.31–0.87). Thus, a diabetic woman with a T-score of −1.9 would have an estimated 10-year hip fracture risk similar to a non-diabetic woman with a T-score of −2.5, the threshold generally used for a diagnosis of osteoporosis.

Table 3.

Estimated difference in femoral neck BMD T-scorea for older adults with and without diabetes with the same 10-year fracture risk

| Non-insulin Diabetes | Insulin Diabetes | p-valueb | All Diabetes | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Fracture site | No. DM with any fracture | Difference (95% CI) | No. DM with any fracture | Difference (95% CI) | Difference (95% CI) | |

| Women | Hip | 72 | 0.59 (0.28, 0.89) | 12 | 0.60 (−0.12, 1.32) | 0.971 | 0.59 (0.31, 0.87) |

| Non-Spine | 212 | 0.78 (0.45, 1.11) | 50 | 1.55 (0.88, 2.21) | 0.040 | 0.91 (0.61, 1.21) | |

| Men | Hip | 27 | 0.35 (0.04, 0.65) | 5 | 0.56 (−0.11, 1.24) | 0.558 | 0.38 (0.09, 0.66) |

| Non-Spine | 108 | 0.33 (0.06, 0.71) | 25 | 1.66 (0.86, 2.47) | 0.002 | 0.51 (0.16, 0.87) | |

Abbreviation: BMD = bone mineral density, DM = diabetes, CI = confidence interval

For the same fracture risk, difference = T-scoreDiabetes − T-scoreNo Diabetes

p-value comparing difference in FN BMD T-score for those with diabetes using and not using insulin

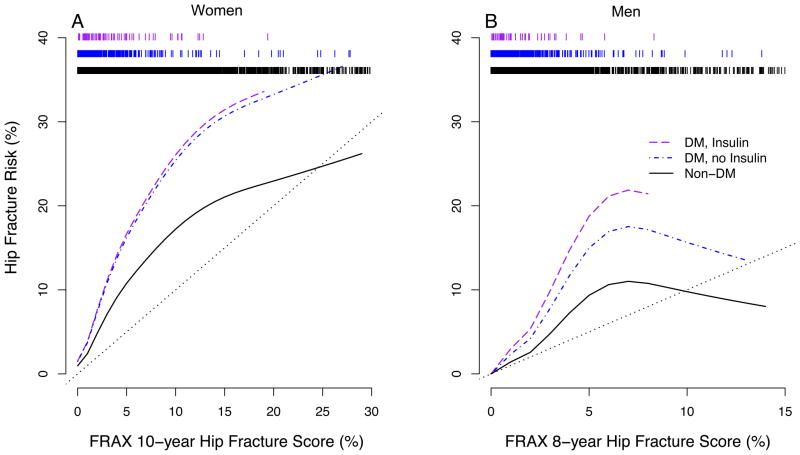

The FRAX score (available for SOF but not Health ABC) is an estimate of the 10-year risk of fracture that takes into account age, BMD and additional risk factors for fracture (Table 1), but not diabetes status. A higher FRAX score was associated with a higher fracture risk during follow-up for women with and without diabetes (Table 2). However, in SOF the FRAX score in diabetic women underestimated the observed long-term risk of fracture, illustrated for hip fracture in Figure 2A.

Figure 2. FRAX hip fracture risk score and risk estimated from hip fracture experience in SOF and MrOS.

A) Ten-year hip fracture risk based on FRAX model versus risk estimated from hip fracture experience in SOF. B) Eight-year hip fracture risk based on FRAX model versus risk estimated from hip fracture experience in MrOS. Rug plots at top of figures indicate number of participants at each level of FRAX score. A (N = 78, 442, 7406), B (N = 80, 801, 5113)

Men

As in women, FN BMD T-score was higher in diabetic than in non-diabetic men in MrOS and in Health ABC (Table 1). In MrOS and Health ABC, 158 non-diabetic and 32 diabetic men experienced at least one hip fracture, and 690 non-diabetic and 133 diabetic men had at least one non-spine fracture during an average follow-up of 7.5 (2.0) years

FN BMD T-score was associated with hip and non-spine fracture in men with diabetes (Table 2) with no evidence of interaction with age, race or insulin use. FN BMD T-score was also strongly associated with fracture risk in non-diabetic men, as observed in previous studies,21 with no evidence of interaction by diabetes status. The C-indexes were similar for men with and without diabetes (Table 2).

Similar to the results for women, for a given FN BMD T-score diabetic men generally had a higher risk of fracture than non-diabetic men of similar age. However, diabetic men who were not using insulin did not have an elevated risk of non-spine fracture at a given BMD T-score, compared with non-diabetic men. This is illustrated in the plots of hip (Figure 1C) and non-spine (Figure 1D) fracture risk versus FN BMD T-score for men aged 75 years, based on our Cox models.

Table 3 provides mean differences in T-scores, comparing men with and without diabetes at a similar fracture risk, to assist with the interpretation of T-scores in diabetic men. For hip fracture, the mean difference in T-scores, comparing men with and without diabetes who have the same fracture risk, was 0.38 (95% CI, 0.09–0.66). Thus, a diabetic man with a T-score of −2.1 would have an estimated 10-year hip fracture risk similar to a non-diabetic man with a T-score of −2.5.

A higher FRAX score was associated with fracture risk for men in MrOS with and without diabetes (Table 2). However, as with women, the FRAX score in diabetic men underestimated the long term risk of fracture that was observed in MrOS, illustrated for hip fracture in Figure 2B.

Sensitivity analyses

Because SOF relied solely on self-report to identify diabetes while fasting glucose assays were available in MrOS and Health ABC, we performed a sensitivity analysis defining diabetes solely based on self-report in all cohorts. Because thiazolidinedione (TZD) use is associated with increased fracture risk in women, and possibly in men,23 we performed a sensitivity analysis excluding participants who reported TZD use during the study (63 participants in SOF, 204 in MrOS and, in Health ABC, 70 women and 79 men). These sensitivity analyses supported our findings in the main analyses.

DISCUSSION

In this first study to prospectively examine the relationship between BMD and fracture in older adults with type 2 diabetes, we found that lower FN BMD and higher FRAX score are associated with hip and non-spine fracture risk.21 The ability of FN BMD T-score or FRAX score to predict fracture is similar in those with and without diabetes. However, for a given T-score and age, those with diabetes had a higher risk of fracture than those without diabetes, consistent with previous reports.3, 4, 8 Diabetic participants also experienced higher fracture rates at a given FRAX score than non-diabetic participants.

Cross-sectional studies have not found an association between BMD and fracture risk in T2DM, perhaps due to small sample size. In a cross-sectional study of 150 older T2DM women in England, those with a previous clinical fracture had lower age-matched lumbar spine and total hip BMD (Z-scores), but the differences were not statistically significant.10 In older diabetic women in Japan (N=150), lumbar spine BMD Z-score was lower but not statistically different in those with, compared to those without, prevalent vertebral fractures.9 In contrast, in this prospective study, we found that FN BMD was associated with risk of hip and non-spine fracture in older men and women with T2DM.

Our results indicate that FN BMD and the FRAX algorithm are as useful for the assessment of fracture risk in older adults with, as in those without, diabetes. However, interpretation of T-score or FRAX score in an older diabetic patient must take into account the higher fracture risk associated with diabetes. For example, using the mean differences in T-scores between those with and without diabetes estimated from these cohorts (Table 3), a T-score in a diabetic woman is associated with hip fracture risk equivalent to a non-diabetic woman with a T-score about 0.5 units lower (0.59 (95% CI, 0.31–0.87)).

FRAX was designed to provide an estimate of absolute fracture risk in older adults that could be used in combination with country-specific cost effectiveness data to set intervention thresholds.24 FRAX has been incorporated into U.S. guidelines for prevention and treatment of osteoporosis.22 The FRAX algorithm does not currently include T2DM as a risk factor for fracture, and our results indicate that use of the FRAX score in diabetic patients will likely underestimate risk. Our results were most consistent for women, but also indicate that FRAX tends to underestimate risk in diabetic men, particularly in those using insulin. To be widely useful, FRAX must necessarily be as brief as possible. However, an adjustment of this algorithm for T2DM seems justified, given the prevalence of diabetes among older adults.

The reasons for increased fracture risk at a given BMD in older adults with diabetes are not clearly understood. Bone strength may be compromised through changes that are not captured with DXA, such as higher levels of advanced glycation endproducts in bone collagen.25 More frequent falls in those with diabetes could also increase fracture risk for a given BMD.26 We did not find an increased risk of non-spine fracture in diabetic men who were not using insulin. Men may be relatively protected from the negative skeletal effects of diabetes due to less rapid bone loss with aging. Our results suggest that insulin therapy might be a useful marker of increased non-spine fracture risk at a given T-score or FRAX score. However, we had limited ability to assess these associations due to the small number of fractures among patients using insulin.

Because of small numbers, we did not assess the ability of T-score or FRAX to predict fracture risk among those using a TZD. There is growing evidence that TZD use increases fracture risk in women, and possibly men.23, 27 Thus, the fracture risks presented here for a given T-score (Figure 1) or FRAX score (Figure 2) are likely an underestimate of risk in those using a TZD.

Our study has several limitations. We did not have glucose measurements in SOF. Diabetes was ascertained solely by self-report which may have led to the inclusion of women with diabetes among the non-diabetic women in SOF. However, this misclassification would tend to underestimate any real differences between those with and without diabetes. It is possible that some diabetic participants had type 1 diabetes as we were not able to distinguish type 1 and type 2 diabetes. However, given the age range of these cohorts, it is likely that very few participants had type 1. Additionally, the analyses did not include vertebral fractures, and FRAX scores were not available in Health ABC. Strengths of our study include the use of data from three large and racially diverse cohorts of older men and women with extended follow-up and adjudication of fracture outcomes.

In conclusion, we found that FN BMD T-score and FRAX are both associated with fracture risk in older adults with type 2 diabetes and appear to be useful for clinical evaluation of fracture risk, despite the paradox of higher BMD with increased fracture risk in this population. However, a given T-score or FRAX score is associated with a higher risk of fracture in older adults with, compared to those without, diabetes. Refinements are needed in current treatment and diagnostic algorithms for use in older patients with type 2 diabetes.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Research support for these analyses was provided by an investigator-initiated grant from Amgen, Inc. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (SOF) is supported by National Institutes of Health funding. The National Institute on Aging (NIA) provides support under the following grant numbers: R01 AG005407, R01 AR35582, R01 AR35583, R01 AR35584, R01 AG005394, R01 AG027574, and R01 AG027576. The Osteoporotic Fractures in Men (MrOS) study is supported by National Institutes of Health funding and by an American Diabetes Association grant (1-04-JF-46, Strotmeyer ES). The following institutes provide support: the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS), the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research under the following grant numbers: U01 AR45580, U01 AR45614, U01 AR45632, U01 AR45647, U01 AR45654, U01 AR45583, U01 AG18197, U01-AG027810, and UL1 RR024140. The Health, Aging, and Body Composition (Health ABC) study is supported by National Institute on Aging (NIA) Contracts N01-AG-6-2101; N01-AG-6-2103; N01-AG-6-2106; NIA grant R01-AG028050; NINR grant R01-NR012459; and by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIA.

Role of the Sponsor: The funding organizations were independent of the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; and preparation of the manuscript. Prior to submission for publication, the manuscript was reviewed by Amgen and was reviewed and approved by the National Institute on Aging.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: All authors have completed and submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest.

Author Contributions: Dr. Schwartz had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design:

Acquisition of data:

Analysis and interpretation of data:

Drafting of the manuscript:

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content:

Statistical analysis: Vittinghoff, Palermo.

Obtained funding:

Administrative, technical, or material support:

Study supervision:

Additional Contributions: We thank Helaine Resnick PhD, Director of Research, Institute for the Future of Aging Services of the American Association of Homes and Services for the Aging, for her helpful comments on a draft manuscript.

References

- 1.Cowie CC, Rust KF, Ford ES, et al. Full accounting of diabetes and pre-diabetes in the U.S. population in 1988–1994 and 2005–2006. Diabetes Care. 2009 Feb;32(2):287–294. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vestergaard P. Discrepancies in bone mineral density and fracture risk in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes--a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2007 Apr;18(4):427–444. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz AV, Sellmeyer DE, Ensrud KE, et al. Older women with diabetes have an increased risk of fracture: a prospective study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(1):32–38. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.1.7139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strotmeyer ES, Cauley JA, Schwartz AV, et al. Nontraumatic fracture risk with diabetes mellitus and impaired fasting glucose in older white and black adults: the health, aging, and body composition study. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Jul 25;165(14):1612–1617. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.14.1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonds DE, Larson JC, Schwartz AV, et al. Risk of fracture among women with type 2 diabetes: the women’s health initiative observational study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006 Sep;91(9):3404–3410. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melton LJ, 3rd, Leibson CL, Achenbach SJ, Therneau TM, Khosla S. Fracture risk in type 2 diabetes: update of a population-based study. J Bone Miner Res. 2008 Aug;23(8):1334–1342. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.080323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dawson-Hughes B, Tosteson AN, Melton LJ, 3rd, et al. Implications of absolute fracture risk assessment for osteoporosis practice guidelines in the USA. Osteoporos Int. 2008 Feb 22;19(4):449–458. doi: 10.1007/s00198-008-0559-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vestergaard P. Discrepancies in bone mineral density and fracture risk in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes-a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2007 Apr;18(4):427–444. doi: 10.1007/s00198-006-0253-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamamoto M, Yamaguchi T, Yamauchi M, Kaji H, Sugimoto T. Bone mineral density is not sensitive enough to assess the risk of vertebral fractures in type 2 diabetic women. Calcif Tissue Int. 2007 Jun;80(6):353–358. doi: 10.1007/s00223-007-9003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel S, Hyer S, Tweed K, et al. Risk factors for fractures and falls in older women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Calcif Tissue Int. 2008 Feb;82(2):87–91. doi: 10.1007/s00223-007-9082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cummings SR, Black DM, Nevitt MC, et al. Bone density at various sites for prediction of hip fractures. The Study of Osteoporotic Fractures Research Group. Lancet. 1993;341:72–75. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92555-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blank JB, Cawthon PM, Carrion-Petersen ML, et al. Overview of recruitment for the osteoporotic fractures in men study (MrOS) Contemp Clin Trials. 2005 Oct;26(5):557–568. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orwoll E, Blank JB, Barrett-Connor E, et al. Design and baseline characteristics of the osteoporotic fractures in men (MrOS) study--a large observational study of the determinants of fracture in older men. Contemp Clin Trials. 2005 Oct;26(5):569–585. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newman AB, Haggerty CL, Goodpaster B, et al. Strength and muscle quality in a well-functioning cohort of older adults: the Health, Aging and Body Composition Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003 Mar;51(3):323–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Looker AC, Wahner HW, Dunn WL, et al. Updated data on proximal femur bone mineral levels of US adults. Osteoporos Int. 1998;8(5):468–489. doi: 10.1007/s001980050093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. [Access date:.2008; ];FRAX WHO Fracture Risk Assessment Tool. http://www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX/

- 17.Ensrud KE, Lui LY, Taylor BC, et al. A comparison of prediction models for fractures in older women: is more better? Arch Intern Med. 2009 Dec 14;169(22):2087–2094. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Donaldson MG, Cawthon PM, Lui LY, et al. Estimates of the proportion of older white men who would be recommended for pharmacologic treatment by the new US National Osteoporosis Foundation guidelines. J Bone Miner Res. 2010 Feb 4; doi: 10.1002/jbmr.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanis JA, Oden A, Johnell O, et al. The use of clinical risk factors enhances the performance of BMD in the prediction of hip and osteoporotic fractures in men and women. Osteoporos Int. 2007 Aug;18(8):1033–1046. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0343-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Johansson H, McCloskey E. FRAX and the assessment of fracture probability in men and women from the UK. Osteoporos Int. 2008 Apr;19(4):385–397. doi: 10.1007/s00198-007-0543-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Johnell O, Kanis JA, Oden A, et al. Predictive value of BMD for hip and other fractures. J Bone Miner Res. 2005 Jul;20(7):1185–1194. doi: 10.1359/JBMR.050304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Osteoporosis Foundation. Clinician’s Guide to Prevention and Treatment of Osteoporosis. Washington, DC: National Osteoporosis Foundation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Loke YK, Singh S, Furberg CD. Long-term use of thiazolidinediones and fractures in type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Cmaj. 2009 Jan 6;180(1):32–39. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.080486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kanis JA, Borgstrom F, De Laet C, et al. Assessment of fracture risk. Osteoporos Int. 2005 Jun;16(6):581–589. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1780-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vashishth D. The role of the collagen matrix in skeletal fragility. Curr Osteoporos Rep. 2007 Jun;5(2):62–66. doi: 10.1007/s11914-007-0004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwartz AV, Hillier TA, Sellmeyer DE, et al. Older women with diabetes have a higher risk of falls: a prospective study. Diabetes Care. 2002 Oct;25(10):1749–1754. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meier C, Kraenzlin ME, Bodmer M, Jick SS, Jick H, Meier CR. Use of thiazolidinediones and fracture risk. Arch Intern Med. 2008 Apr 28;168(8):820–825. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.8.820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]