Abstract

Physiological control of the co-factor tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) is tight in normal circumstances but levels increase pathologically in the injured somatosensory system. BH4 is an essential co-factor in the production of serotonin, dopamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine and nitric oxide. Excess BH4 levels cause pain, likely through excess production of one or more of these neurotransmitters or signaling molecules. The rate limiting step for BH4 production is GTP Cyclohydrolase 1 (GCH1). A human GCH1 gene haplotype exists that leads to less GCH1 transcription, translation, and therefore enzyme activity, following cellular stress. Carriers of this haplotype produce less BH4 and therefore feel less pain, especially following nerve injury where BH4 production is pathologically augmented. Sulfasalazine (SSZ) an FDA approved anti-inflammatory agent of unknown mechanism of action, has recently been shown to be a sepiapterin reductase (SPR) inhibitor. SPR is part of the BH4 synthesis cascade and is also upregulated by nerve injury. Inhibiting SPR will reduce BH4 levels and therefore should act as an analgesic. We propose SSZ as a novel anti-neuropathic pain medicine.

Tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) and chronic pain

Recent developments in ‘whole genome’ expression profiling have dramatically improved our understanding of a cell’s molecular phenotype by comprehensively quantifying messenger RNA (mRNA) content. This revolution began at the turn of the twenty-first century with the advent of mRNA microarrays and has continued with mRNA seq [1]. Whole genome expression analysis in the somatosensory system, before and after injury, has been at the forefront of these technological leaps [2–4]. Being able to reliably quantify in an unbiased fashion all transcripts within a cell offers new insights into the metabolic, signaling or biosynthetic pathways involved in disease states, such as those that produce chronic neuropathic pain. In 2006, using expression arrays we identified three of the enzymes that are critical to the control of intracellular levels of tetrahydrobiopterin (BH4) as highly regulated within injured sensory neurons: GCH1, SPR and QDPR (Fig 1)[5]. We hypothesized that the up-regulation together of multiple enzymes within the same biosynthetic pathway may be a clue to that pathways relevance to the initiation or persistence of chronic pain. Further, the product of this pathway BH4 is an essential co-factor for the synthesis of serotonin, dopamine, epinephrine, norepinephrine and nitric oxide [6] suggesting that inducing large excesses of cellular BH4 might lead to profound alterations in the physiology of the injured sensory neuron, something that indeed turned out to be the case [5,7].

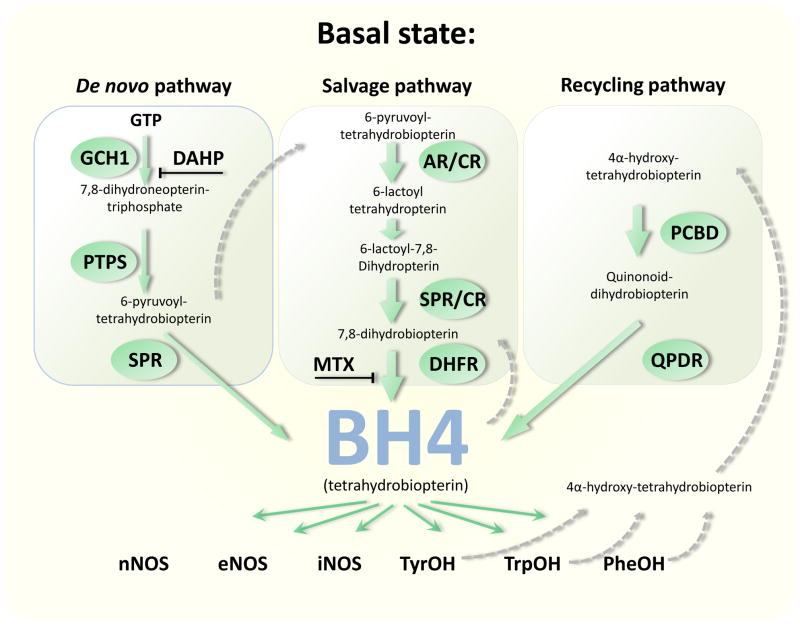

Figure 1.

Three pathways contribute to cellular BH4 levels, the synthesis pathway, the salvage pathway and the recycling pathway. BH4 is an essential cofactor for all the nitric oxide synthase enzymes (NOS); tyrosine hydroxylase (TyrOH); tryptophan hydroxylase (TrpOH) and phenylalanine hydroxylase (PheOH). Known inhibitors of these pathways include 2,4 diamino-6-hydroxypyrimidine (DAHP) and methotrexate (MTX). Enzymes shown are GTP cyclohydroxylase 1 (GCH1); 6-pyruvoyl tetrahydrobiopterin synthase (PTS); sepiapterin reductase (SPR); aldose reductase (AR); carbonyl reductase (CR); dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR); pterin-4α-carbinolamine dehydratase (PCBD) and quinonoid-dihydrobiopterin reductase (QDPR).

Metabolic control of BH4 levels is tight and controlled by three main pathways: the de novo synthesis cascade, the recycling pathway and the salvage pathway (Fig 1). Evidence from enzyme expression in healthy animals suggests that in sensory neurons activity of the de novo pathway is tonically low, with the recycling and salvage pathways maintaining the basal homeostatic levels of BH4. So, although GCH1 is the obligate rate limiting step in BH4 synthesis, new production is tightly controlled and normally is set at very low levels. This situation changes dramatically after peripheral nerve injury, where injured neurons exhibit a marked and long-lasting upregulation of GCH1 mRNA, protein and activity, causing an order of magnitude increase in intracellular BH4 levels [5]. In addition to increased production by the synthesis pathway, BH4 recycling remains very efficient and actually increases its activity, thereby further exacerbating the pathological increase in cellular BH4. Lowering BH4 levels using 2,4-Diamino-6-hydroxypyrimidine (DAHP) a selective but poor affinity GCH1 inhibitor (IC50 0.3 mM) produces analgesia in rats following nerve injury and inflammation, confirming the pronociceptive action of excess BH4 production in the somatosensory system [5].

The final enzyme within the BH4 synthesis pathway is sepiapterin reductase (SPR; Fig 1), the transcript for which is also upregulated following nerve injury [5]. Interestingly, although SPR represents the main catalytic route in the terminal step of BH4 synthesis it is not the only one, in the absence of SPR, two enzymes, aldose reductase and carbonyl reductase, can catalyze reactions to form BH2 (7,8-dihydrobiopterin), which is then converted to BH4 by the dihydrofolate reductase DHFR [6]. As a consequence, DHFR activity can produce enough BH4 in the liver and other peripheral tissues to allow for an SPR independent synthesis of BH4, although this does not occur in the CNS, because DHFR is not heavily expressed there [8] (Fig 1). Inhibiting SPR could offer a very useful way to prevent excess activity in the synthesis cascade whilst still allowing cells outside the CNS to produce new BH4 when required. This scenario would not be the case if GCH1 were inhibited, as this enzymes reaction cannot be replicated.

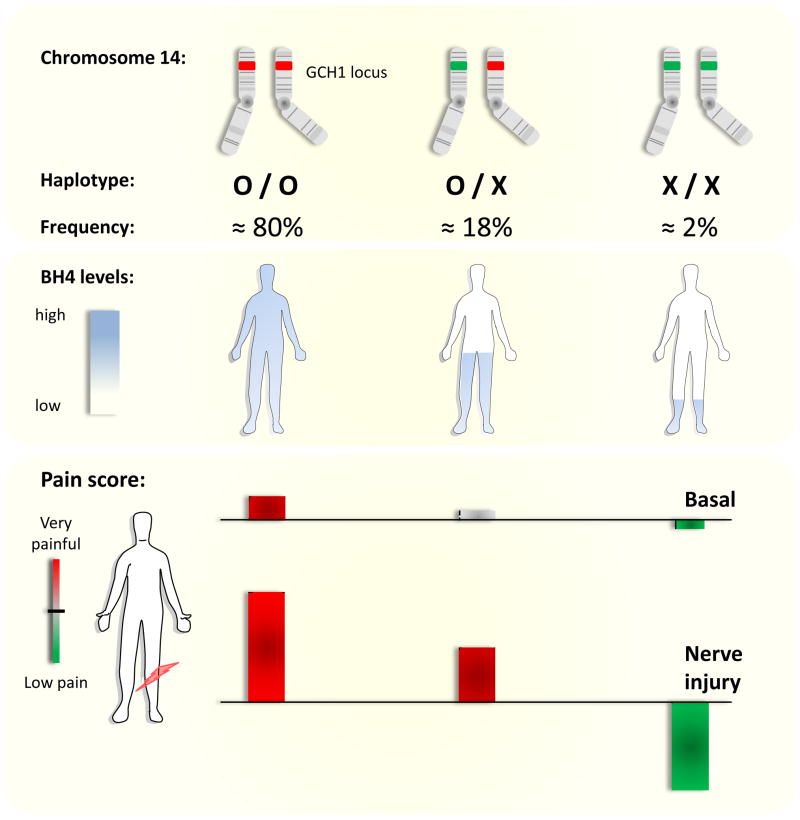

We were also able to show that a natural genetic polymorphism in humans that alters how GCH1 is regulated in response to cellular stress alters chronic pain markedly [5]. The effect of the haplotype depends on which type of pain is assayed, nociceptive pain is less altered than inflammatory, with maximal effect for neuropathic pain, where BH4 production in individuals without the polymorphism is amplified (Fig 2). In the original study defining the association of a GCH1 haplotype with the pain phenotype two cohorts of individuals were tested. The first was a prospective group of lower back pain patients who underwent diskectomy surgery to remove a slipped disk which was impinging on their lumbar dorsal roots. These patients have chronically damaged peripheral nerves, which presumably, by analogy to our rodent data, enhances BH4 production. Following diskectomy surgery to relieve the nerve pressure, patients were scored on pain outcome four times over a year. Average scores, corrected for other variables, were associated with SNP markers spread across GCH1. Some of these SNPs defined a particular haplotype which correlated well with improvement in pain outcome, non-carriers of the haplotype had an average pain score of 0.81 (n=116), heterozygous carriers scored 0.44 (n=42) with the relatively few homozygous haplotype carriers (two alleles) scoring 0.067 (n=4). These values represent a cumulative z-score with higher numbers meaning more pain, the overall value for this additive correlation is p=0.0094 (Fig 2). Therefore this GCH1 haplotype present in a homozygous and heterozygous form in ~2% and ~18% of the population respectively, associates with reduced ongoing pain, or is pain-protective. We hypothesize that a mutation identified by this haplotype, somewhere close to or inside the GCH1 gene, modifies the activity of the enzyme in response to cellular challenges. After nerve injury this mutation unmasks a phenotype (reduced pain sensitivity) which is present at a more subtle level in non-injured individuals.

Figure 2.

The GCH1 ‘pain protective’ haplotype shows additive inheritance (heterozygous individuals have an intermediate phenotype) further the effect of the haplotype is much more pronounced when nerve damage has augmented the system.

The second cohort tested, for experimental pain, totaled 547 individuals. Of these 10 were homozygous for the pain-protective haplotype. Here a marked change in phenotype only occurred in the homozygous subjects, presumably because the subjects were healthy and the GCH1 synthesis pathway had not been functionally augmented. We assume therefore that only homozygous carriers would have significantly lowered basal level of GCH1 activity. Even so, for thermal and ischemic nociceptive pain modalities although the effects are too slight to reach significance, phenotypes are consistent with an additive pattern of inheritance, for mechanical pain significance was achieved [5].

Tegeder et al (2006) obtained additional data from two independent cohorts both of which were consistent with a pain-protective haplotype, more importantly the study went on to analyze the functional consequences of the haplotype on GCH1 regulation and activity in response to a forskolin challenge. This was achieved using immortalized leukocytes obtained from the individuals participating in the lumbar back pain study, both BH4 levels and GCH1 protein levels changed in a way consistent with the haplotype’s proposed effect i.e. leukocytes with homozygous haplotype genomes produced the least BH4, with the heterozygous carriers producing intermediate levels and non carrying genomes the highest. These studies indicate that the pain protective association is very likely due a change in GCH1 function (Fig 2).

Further positive association studies that provide support for a GCH1 pain-protective haplotype include, a follow up paper by Tegeder et al 2008 [9] which pre-screened German medical students for the haplotype, 10 homozygotes were then compared with 22 non-carriers for various experimental pain modalities. Using primary white blood cells GCH1 activity were assayed before and after LPS stimulation, as expected there was significantly less biopterin (a BH4 surrogate) in the homozygotes and less pain senstivity. Another study, from independent authors, also used capsaicin-induced experimental pain to reveal a positive association [10]. In a German outpatient population with ongoing pain screened for the GCH1 haplotype, homozygous carriers had significantly shorter therapy durations, as well as a clear tendency to lower pain scores and reduced opioid doses, although these outcome measures just missed significance [11]. A further follow up study on cancer pain patients assayed for GCH1 haplotype association, showed that non carriers required opioid pain management for on average 78 months post cancer diagnosis relative to 37 months for heterozygous carriers and 30 months for homozygotes [12]. Recently Kim et al replicated the original findings in a new group of lumbar degenerative disc disease patients followed post surgery for pain outcome [13].

In addition to associating the reduced-function GCH1 haplotype with pain protection, others have defined a role for this haplotype in the cardiovascular system (CVS). The first study determined a single variant GCH1 associated SNP associated with certain CVS phentotypes in a relatively large cohort. Association between this haplotype and reduced renal metabolite nitric oxide (NO) excretion was seen suggesting reduced BH4 levels [14]. Doehring et al subsequently showed that this mutation is linked to the pain-protective haplotype, further supporting the existence of a genomic variant that alters GCH1 regulation [15]. In addition the GCH1 haplotype associated with increased vascular superoxide production in the CVS reduced GCH1 mRNA and plasma BH4 levels [16].

Although the GCH1 haplotype has been replicated multiple times by differing authors some studies do not show an association, it is difficult to define the reasons for negative data, but many confounders exist in association genetics [6]. However since its discovery in 2006 there are nine cohorts that give a positive association of phenotypes consistent with reduced GCH1 function, of which four link this haplotype to altered GCH1 activity.

Genetic evidence in humans as well as pharmacological and shRNA based evidence [7] in rodents suggest the BH4 synthesis pathway as a novel target for reducing chronic inflammatory and especially neuropathic pain. Inhibiting GCH1 as the rate limiting and obligate first step of this pathway produces analgesia in animals, but the therapeutic index for GCH1 inhibitors might be relatively limited if basal BH4 levels are reduced at doses required to decrease pathologically elevated levels. Other enzymes in the synthesis cascade, whose inhibition can be bypassed, may be even more attractive drug targets. One of these enzymes is SPR. Until recently SPR inhibitors (e.g. N-acetylserotonin, NAS) were relatively ineffective, non-specific and not available for clinical use. However new evidence from a technically impressive paper published recently has altered this position dramatically by revealing that the clinically available drug sulfasalzine is an SPR inhibitor [17].

Sulfasalazine (SSZ) as an SPR inhibitor

Chidley and colleagues (2011) [17] performed a yeast three hybrid (Y3H), an approach they designed to assay for novel drug-protein interactions. A drug of interest is covalently bound to a linker and this moiety then binds to a SNAP-tag LexA construct in living yeast cells. This drug-SNAP-LexA protein in turn binds a specific site within the reporter gene promoter via a DNA binding cassette to create a ‘bait construct’. In addition, a target protein expressed from a cDNA library and fused to GAL4 activation domain is expressed within these cells to create the ‘prey construct’. GAL4 mediated initiation of reporter gene transcription only occurs when the drug bait binds the target protein–GAL4 prey construct.

As a positive control they used the commonly prescribed anti-inflammatory agent methotrexate (MTX), which is well known to be a dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR) inhibitor (Fig 1). In addition, the binding of MTX can be modulated by known DHFR point mutations (altering drug KD ~50-fold) allowing for a well controlled assessment of drug-protein interaction versus background. These controls and others were used to minimize the presence of false positives from the Y3H screen. Using such methods the authors were able to identify a total of 173 hits dependent on the presence of the MTX derivative for growth; all 173 hits encoded for hDHFR, demonstrating the efficacy of the Y3H system.

Along with other approved drugs whose protein interactions (i.e. potential targets) remain uncertain, the authors then went on to test SSZ protein binding. Interestingly the only interaction of SSZ found within the screen was with SPR, a result confirmed later by pull down assays. Next the authors demonstrated that SSZ altered SPR activity showing that it inhibits SPR with an IC50 of 23 nM. By comparison the known SPR inhibitor NAS, which we have shown has analgesic qualities [5] has an IC50 of 3.1 μM. The principal metabolites of sulfasalazine also inhibited SPR although with lower potency: sulfapyridine and N-acetylsulfapyridine inhibited SPR with IC50s of 480 nM and 290 nM, respectively, whereas mesalamine inhibited SPR with an IC50 of 370 μM [17]. Next the authors tested the ability of SSZ to modulate intracellular BH4 levels in rat pheochromocytoma (PC12) cells. PC12 cells extend axons in response to nerve growth factor, are derived from adrenal sympathetic neural progenitors and are used routinely as analogues for sensory neurons in culture. They express the BH4 synthesis cascade to produce catecholamines, neurotransmitters and nitric oxide [18]. Sulfasalazine, sulfapyridine and N-acetylsulfapyridine effectively reduced intracellular biopterin levels (indicating BH4 biosynthesis) at micromolar concentrations. All of these compounds were markedly more effective than the known SPR inhibitor NAS. Sulfapyridine and N-acetylsulfapyridine show higher activity in the cellular assay relative to sulfasalazine, probably due to active removal of this drug by cellular efflux pumps. The alternative SSZ metabolite mesalamine affects BH4 biosynthesis at higher concentrations (>1 mM).

In summary then, the authors have found and proven that one of SSZ’s actions is potent inhibition of SPR. The concentrations of sulfasalazine and its metabolites required for in vitro inhibition of BH4 biosynthesis are within the range of their in vivo concentrations following standard SSZ drug treatment in patients, indicating that this inhibition may well be its primary mechanism of action. The combined concentration of sulfapyridine and N-acetylsulfapyridine in serum and in synovial fluid during standard sulfasalazine therapy is ~ 100 μM; the corresponding values for sulfasalazine and mesalamine are both ~ 15 μM [19,20].

Sulfasalazine as an analgesic

Based only on its known anti-inflammatory role and postulated role in NFkB inhibition and in increasing extracellular adenosine levels Berti-Mattera and colleagues (2008) [21] tested the analgesic properties of this drug in a model of chronic diabetic neuropathy in rats and found that SSZ completely blocked tactile allodynia and partially protected against mechanical hyperalgesia, which was not the case following sodium salicylate (SAL), acetylsalicylic acid (aspirin), or PJ34 treatment, a poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP1) inhibitor [22]. Rats received sulfasalazine (100 mg/kg/day) for extended periods (up to 9 months) and the drug remained effective throughout. SSZ not only prevented tactile allodynia but reversed it, namely treatment was effective if it began after onset of neuropathic hypersensitivity.

These new data that SSZ is a potent SPR inhibitor and reduces pain like behavior in a rodent model of diabetic neuropathy provide strong independent support for a role for the BH4 pathway in pain, and indeed raise the question whether the other postulated roles of SSZ, such acting as an anti-inflammatory agent, are downstream of SPR inhibition.

Sulfasalazine as a medication

Sulfasalazine (SSZ) is currently used as an anti-inflammatory drug to treat rheumatoid arthritis (RA), inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and ankylosing spondylitis. The drug is taken orally, typically at adult maintenance doses of 2 grams/day. Interestingly SSZ is often considered in the same class of anti-inflammatory agents as methotrexate (MTX) and in some cases these drugs are co-prescribed [23]. MTX is a DHFR inhibitor and therefore inhibits the BH4 salvage pathway, reducing cellular BH4 levels.

Sulfasalazine’s analgesic action in rheumatoid arthritis

Multiple drug efficacy trials for SSZ have been performed with those for RA often including a primary outcome measure of pain control [20,24]. In a Cochrane report three of six studies reported on pain outcome versus placebo, all three had reduced pain scores with a standardized weighted mean difference of for pain −0.42 (95%CI −0.72;−0.12), test for overall effect: Z = 2.80 (P = 0.0051). These data are significant and moderately strong with 0.30 being an effect size considered to be clinically meaningful in RA [24]. In 2005 Plosker and Croom reviewed randomized, double-blind trials comparing the clinical efficacy of SSZ with other disease-modifying anti-inflammatory drugs in RA patients [20]. Three of the eight studies reported on pain scores (visual analogue scale) and in each case the change in pain score was an improvement of approximately 40% with SSZ performing at least as well as the other drugs tested. These data then are encouraging with respect to SSZs potential analgesic actions in patients with chronic inflammatory pain and would suggest potential for this SPR inhibitor having analgesic actions in other conditions where BH4 levels are elevated, like neuropathic pain.

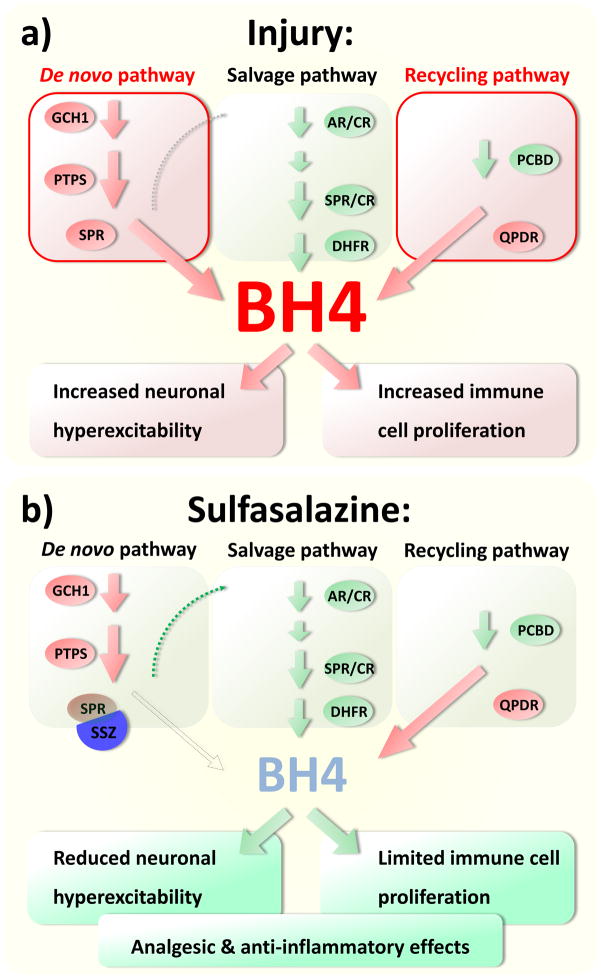

Recent studies have shown a GCH1 mediated activation of T-lymphocytes [25] and this may mean that BH4 has a specific role in immune cell modulation, as well as in producing pain, and therefore that reducing BH4 levels in T-cells may contribute to or even account for SSZ’s anti-inflammatory effects. This may also be true for methotrexate, SSZ and MTX inhibit the same cellular pathway - BH4 metabolism and both are effective anti-inflammatory agents. It maybe therefore that one of the consequences of intracellular BH4 reduction is a reduction in T-cell signaling, and SSZ within this respect may be analogous to anti-TNF therapies which also reduce T-cell function [26]. T-lymphocytes are involved in the generation of neuropathic pain [27], therefore commonalities of action within this regard, reduced T-cell function and reduced pro-nociceptive actions of BH4 in sensory neurons might be beneficial in attenuating neuropathic pain (Fig 3).

Figure 3.

A: BH4 synthesis and recycling increase following cellular injury, higher levels of BH4 lead to neuronal hyperexcitability and immune cell activation. B: Reducing BH4 synthesis with the SPR inhibitor SSZ will reduce ongoing sensory neuron activity and immune cell function, both of these effects would help attenuate pain, especially we propose, following nerve injury.

Hiding in plain sight - Sulfasalazine as a chronic pain medication?

Sulfasalazine is an FDA approved, relatively safe and effective anti-inflammatory agent, whose specific molecular mechanism of action was not known until it was shown this year to act as an SPR inhibitor. Preclinical data shows that SSZ reduces pain related behavior in a rodent model of diabetic neuropathy. We have shown large increases in BH4 production in rodents with chronic pain, especially neuropathic injuries, an analgesic action of inhibiting excess BH4 production in sensory neurons, and a GCH1 haplotype that is associated with reduced BH4 levels following cellular stress and attenuated chronic pain in humans. Collectively all these data provide evidence that the BH4 pathway is involved in pain and that inhibition of BH4 synthesis is a viable strategy for developing novel analgesics. Sulfasalazine is therefore a very useful research and clinical tool to further explore the role of BH4 in inflammation and pain. For the future, we envisage the development of more potent and specific SPR inhibitors to reduce excess BH4 production within injured sensory neurons and activated immune cells which may be clinically useful analgesics and anti-inflammatory reagents. Because SSZ has a relatively low side effect profile, it implies that inhibition of SPR and the resultant decrease in BH4 levels does not cause serious adverse CNS or CVS effects.

Acknowledgments

This work is funded by the NIH (R01-NS058870)

References

- 1.Lander ES. Initial impact of the sequencing of the human genome. Nature. 2011;470:187–197. doi: 10.1038/nature09792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Costigan M, Befort K, Karchewski L, Griffin RS, D’Urso D, Allchorne A, Sitarski J, Mannion JW, Pratt RE, Woolf CJ. Replicate high-density rat genome oligonucleotide microarrays reveal hundreds of regulated genes in the dorsal root ganglion after peripheral nerve injury. BMC Neurosci. 2002;3:16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-3-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang H, Sun H, Della Penna K, Benz RJ, Xu J, Gerhold DL, Holder DJ, Koblan KS. Chronic neuropathic pain is accompanied by global changes in gene expression and shares pathobiology with neurodegenerative diseases. Neuroscience. 2002;114:529–546. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00341-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammer P, Banck MS, Amberg R, Wang C, Petznick G, Luo S, Khrebtukova I, Schroth GP, Beyerlein P, Beutler AS. mRNA-seq with agnostic splice site discovery for nervous system transcriptomics tested in chronic pain. Genome Res. 2010;20:847–860. doi: 10.1101/gr.101204.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tegeder I, Costigan M, Griffin RS, Abele A, Belfer I, Schmidt H, Ehnert C, Nejim J, Marian C, Scholz J, et al. GTP cyclohydrolase and tetrahydrobiopterin regulate pain sensitivity and persistence. Nat Med. 2006;12:1269–1277. doi: 10.1038/nm1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Latremoliere A, Costigan M. GCH1, BH4 and Pain. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2011 doi: 10.2174/138920111798357393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim SJ, Lee WI, Lee YS, Kim DH, Chang JW, Kim SW, Lee H. Effective relief of neuropathic pain by adeno-associated virus-mediated expression of a small hairpin RNA against GTP cyclohydrolase 1. Mol Pain. 2009;5:67. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-5-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blau N, Bonafe L, Thony B. Tetrahydrobiopterin deficiencies without hyperphenylalaninemia: diagnosis and genetics of dopa-responsive dystonia and sepiapterin reductase deficiency. Mol Genet Metab. 2001;74:172–185. doi: 10.1006/mgme.2001.3213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tegeder I, Adolph J, Schmidt H, Woolf CJ, Geisslinger G, Lotsch J. Reduced hyperalgesia in homozygous carriers of a GTP cyclohydrolase 1 haplotype. Eur J Pain. 2008;12:1069–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.ejpain.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell CM, Edwards RR, Carmona C, Uhart M, Wand G, Carteret A, Kim YK, Frost J, Campbell JN. Polymorphisms in the GTP cyclohydrolase gene (GCH1) are associated with ratings of capsaicin pain. Pain. 2009;141:114–118. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2008.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doehring A, Freynhagen R, Griessinger N, Zimmermann M, Sittl R, Hentig N, Geisslinger G, Lotsch J. Cross-sectional assessment of the consequences of a GTP cyclohydrolase 1 haplotype for specialized tertiary outpatient pain care. Clin J Pain. 2009;25:781–785. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181b43e12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lotsch J, Klepstad P, Doehring A, Dale O. A GTP cyclohydrolase 1 genetic variant delays cancer pain. Pain. 2010;148:103–106. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim DH, Dai F, Belfer I, Banco RJ, Martha JF, Tighiouart H, Tromanhauser SG, Jenis LG, Hunter DJ, Schwartz CE. Polymorphic variation of the guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase 1 gene predicts outcome in patients undergoing surgical treatment for lumbar degenerative disc disease. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2011;35:1909–1914. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181eea007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang L, Rao F, Zhang K, Khandrika S, Das M, Vaingankar SM, Bao X, Rana BK, Smith DW, Wessel J, et al. Discovery of common human genetic variants of GTP cyclohydrolase 1 (GCH1) governing nitric oxide, autonomic activity, and cardiovascular risk. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2658–2671. doi: 10.1172/JCI31093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Doehring A, Antoniades C, Channon KM, Tegeder I, Lotsch J. Clinical genetics of functionally mild non-coding GTP cyclohydrolase 1 (GCH1) polymorphisms modulating pain and cardiovascular risk. Mutat Res. 2008;659:195–201. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antoniades C, Shirodaria C, Van Assche T, Cunnington C, Tegeder I, Lotsch J, Guzik TJ, Leeson P, Diesch J, Tousoulis D, et al. GCH1 haplotype determines vascular and plasma biopterin availability in coronary artery disease effects on vascular superoxide production and endothelial function. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.12.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chidley C, Haruki H, Pedersen MG, Muller E, Johnsson K. A yeast-based screen reveals that sulfasalazine inhibits tetrahydrobiopterin biosynthesis. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:375–383. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anastasiadis PZ, Kuhn DM, Blitz J, Imerman BA, Louie MC, Levine RA. Regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase and tetrahydrobiopterin biosynthetic enzymes in PC12 cells by NGF, EGF and IFN-gamma. Brain Res. 1996;713:125–133. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(95)01494-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farr M, Brodrick A, Bacon PA. Plasma and synovial fluid concentrations of sulphasalazine and two of its metabolites in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int. 1985;5:247–251. doi: 10.1007/BF00541351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Plosker GL, Croom KF. Sulfasalazine: a review of its use in the management of rheumatoid arthritis. Drugs. 2005;65:1825–1849. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200565130-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berti-Mattera LN, Kern TS, Siegel RE, Nemet I, Mitchell R. Sulfasalazine blocks the development of tactile allodynia in diabetic rats. Diabetes. 2008;57:2801–2808. doi: 10.2337/db07-1274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mabley JG, Jagtap P, Perretti M, Getting SJ, Salzman AL, Virag L, Szabo E, Soriano FG, Liaudet L, Abdelkarim GE, et al. Anti-inflammatory effects of a novel, potent inhibitor of poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase. Inflamm Res. 2001;50:561–569. doi: 10.1007/PL00000234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cronstein BN. The antirheumatic agents sulphasalazine and methotrexate share an anti-inflammatory mechanism. Br J Rheumatol. 1995;34 (Suppl 2):30–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Suarez-Almazor ME, Belseck E, Shea B, Wells G, Tugwell P. Sulfasalazine for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000:CD000958. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen W, Li L, Brod T, Saeed O, Thabet S, Jansen T, Dikalov S, Weyand C, Goronzy J, Harrison DG. Role of increased guanosine triphosphate cyclohydrolase-1 expression and tetrahydrobiopterin levels upon T cell activation. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:13846–13851. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.191023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong M, Ziring D, Korin Y, Desai S, Kim S, Lin J, Gjertson D, Braun J, Reed E, Singh RR. TNFalpha blockade in human diseases: mechanisms and future directions. Clin Immunol. 2008;126:121–136. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.08.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costigan M, Moss A, Latremoliere A, Johnston C, Verma-Gandhu M, Herbert TA, Barrett L, Brenner GJ, Vardeh D, Woolf CJ, et al. T-cell infiltration and signaling in the adult dorsal spinal cord is a major contributor to neuropathic pain-like hypersensitivity. J Neurosci. 2009;29:14415–14422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4569-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]