Abstract

Background

Depression and anxiety disorders (AD) are highly comorbid, but the reason for this comorbidity is unclear. One possibility is that they predispose one another. An informative way to examine interactions between disorders without the confounds present in patient populations is to manipulate the psychological processes thought to underlie the pathological states in healthy individuals. In this paper we therefore asked whether a model of the sad mood in depression can enhance psychophysiological responses (startle) to a model of the anxiety in AD. We predicted that sad mood would increase anxious anxiety-potentiated startle responses.

Methods

In a between-subjects design, participants (N=36) completed either a sad mood induction procedure (N=18) or neutral mood induction procedure (N=18). Startle responses were assessed during short duration predictable electric shock conditions (fear-potentiated startle) or long-duration unpredictable threat of shock conditions (anxiety-potentiated startle).

Results

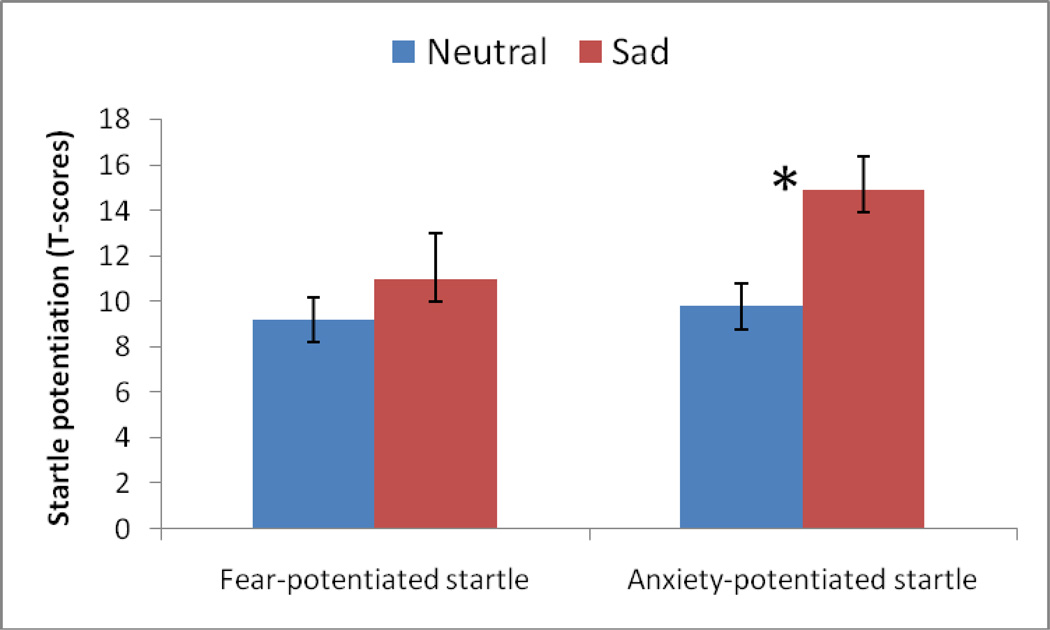

Induced sadness enhanced anxiety-, but not fear- potentiated startle.

Conclusions

This study provides support for the hypothesis that sadness can increase anxious responding measured by the affective startle response. This, taken together with prior evidence that AD can contribute to depression, provides initial experimental support for the proposition that AD and depression are frequently comorbid because they may be mutually reinforcing.

Keywords: anxiety, sadness, startle reflex, mood, depression, comorbidity

Introduction

Major depression and anxiety disorders (AD) are debilitating and extremely prevalent diagnoses (Kessler et al. 2005) with wide-reaching negative psychological and economic impacts for both the individual and society (Beddington et al. 2008; Greenberg et al. 2003). The two sets of disorders are different; they can show distinct ages of onset (Kessler et al. 2005), distinct heritability and genetic patterns (Eley 1999; Jardine et al. 1984; Kendler et al. 1995), differential impact upon cognitive performance (Bierman et al. 2005; Mogg et al. 1993), opposite effects on arousal (Clark and Watson 1991), and distinct pharmacological profiles (Deakin 1998). Furthermore, the predominant subjective emotion in each disorder is different: anxiety disorders are characterized by a state of ‘worry’ (and normal positive affect), whereas depression is characterized by ‘sadness’ (and reduced positive affect) (Brady and Kendall 1992; Clark and Watson 1991). Nevertheless, depression and AD are also highly comorbid with around 50–60% of depressed individuals reporting a lifetime history of AD (Kaufman and Charney 2000; Kessler et al. 2005). This comorbid pathology tends to be more persistent than either disorder alone (Merikangas et al. 2003), with increased overall life impairment (Kessler et al. 1998), worse treatment outcomes (Brown et al. 1996), and increased likelihood of suicide (Angst et al. 1999). The underlying causes of this comorbidity remain, however, unresolved.

One possibility is that there is a relationship between the two sets of disorders which promotes comorbidity. Negative affective states (like depressed and anxious emotional states) increase negative emotional reactivity (Rosenberg 1998) by potentiating the response to negatively-valenced stimuli (Dichter and Tomarken 2008). Depression and AD may therefore predispose one another through the promotion of such negative emotional reactivity. Support for this idea comes from Beck’s schema model, which argues that cognitive biases distort the processing of emotional stimuli (Beck 1967) and that depressed and sad mood can promote these biases, potentiating reactivity to negative stimuli. Accordingly, sad and depressed mood may sensitize the amygdala/bed nucleus of the stria terminalis fear/anxiety response network, facilitating the development of anxiety disorders.

Consistent with this, there is clear neurocognitive evidence for hyperactive aversive responding in depression (Clark et al. 2009; Elliott et al. 2011; Eshel and Roiser 2010). However, a number of psychophysiological studies point to a pervasive hyporeactivity to both positively-valenced stimuli and negatively-valenced stimuli in depression (Allen et al. 1999; Dichter and Tomarken 2008; Dichter et al. 2004; Forbes et al. 2005; Kaviani et al. 2004; McTeague et al. 2009; Rosenberg 1998). These apparent discrepancies may be due, at least in part, to differences in depression severity across studies and, in psychophysiological studies, to procedural differences such as the nature and duration of the stimuli used to evoke responses. This latter distinction is especially critical for two reasons. First, short- and long-duration aversive responses have been conceptualized as fear and anxiety responses, respectively. Fear is similar to phobic fear, whereas anxiety is viewed as a sustained aversive state cutting across several anxiety disorders including generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Davis et al 2010). A wealth of animal and human studies has demonstrated separate neural and pharmacological systems mediating these two types of aversive responses (Davis et al. 2010; Grillon 2008b; Miles et al. 2011), raising the possibility that depression might have distinct effects on each response. In fact, depression is not associated with the high emotional and physiological arousal that characterizes fear-related disorders (e.g., phobias) (Dichter and Tomarken 2008). Second, depression is a state of rumination and impaired regulation of response to sustained stressors (Cooney et al. 2010; Nolen-Hoeksema 2000; Tomarken et al. 2007). As such, hyperactivity may be seen for long-duration anxiety responses rather than for phasic fear.

One way to begin testing basic hypotheses about psychiatric disorders is to adopt models of psychiatric disorders in healthy individuals (Grillon 2008b; Mayberg et al. 1999; Robinson and Sahakian 2009a). This technique has proven fruitful in the past. For instance, evidence was found for a neurocognitive model of recurrence in depression (Robinson and Sahakian 2008) by pairing a serotonin reduction technique with sad mood induction. In the present study we thus pair the same mood induction technique (Robinson and Sahakian 2009b) with a threat of shock paradigm (Grillon and Baas 2003) to examine putative interactions between fear/anxiety and depression. The threat of shock paradigm evokes robust fear and anxiety, and their behavioral, cognitive, and neural concomitants in healthy individuals (Alvarez et al. 2011; Grillon 2008b; Robinson et al. 2011) Similarly, the mood induction technique induces subjective physiological, neural, and cognitive symptoms of depression in healthy individuals (Berna et al. 2010; Mayberg et al. 1999; Mitchell and Phillips 2007; Robinson and Sahakian 2009b). The correspondence between these models and pathological states may be a result of the induced states recruiting the same adaptive mechanisms which, when experienced to excess, underlie the pathological states (Sanislow et al. 2010). In the threat of shock paradigm short-duration (fear) and long-duration (anxiety) aversive responses were assessed by having subjects anticipate predictable or unpredictable shocks, respectively (Grillon 2008b). Aversive states were then measured using the startle reflex. We hypothesized, based upon a) the assumption that sad mood would promote negative emotional reactivity and aversive responses and b) evidence that depression does not increase fear-potentiated startle, that sad mood would increase the potentiation of startle by unpredictable shocks, but not by predictable shocks.

As such, we took two validated techniques for inducing symptoms of sadness and anxiety in healthy individuals, and examined their combined impact on a sensitive psychophysiological measure of aversive states. Using such tests in healthy individuals thus allows us to test hypotheses about psychiatric disorders in the absence of the many confounds present in patient populations

Methods

Participants

Thirty-eight paid healthy volunteers participated in the study (Table 1). Inclusion criteria consisted of the following: 1) no past or current psychiatric disorders as per Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID:(First et al. 2002, 2 no history of a psychiatric disorder in any first degree relatives; 3) no medical condition that interfered with the objectives of the study as established by a physician, and 4) no use of illicit drugs or psychoactive medications as per history and confirmed by a negative urine screen. All participants gave written informed consent approved by the NIMH Human Investigation Review Board.

Table 1.

Mean (sem) subjects age and HA and BDI scores

| Neutral | Sad | Group comparison | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males N=6 |

Females N=13 |

Males N=6 |

Females N=13 |

Sad vs Neutral | |

| Age | 26.1 (2.8) | 26.2 (1.9) | 29.5 (2.8) | 27.7 (1.9) | t(36)=0.9, NS |

| TPQ-HA | 5.8 (1.3) | 8.5 (1.4) | 4.6 (1.6) | 7.7 (1.3) | t(36)=0.55, NS |

| BDI | .8 (.3) | .4 (1.4) | .5 (.2) | 1.3 (.6) | t(36)=0.5, NS |

Procedure

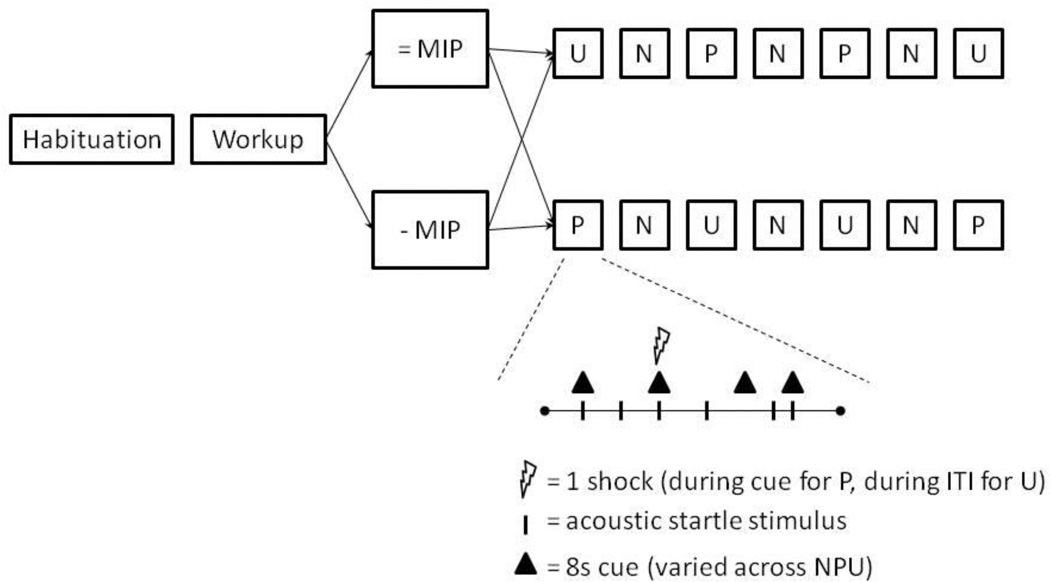

The procedure used a between-subject design (to avoid order effects associated with repeating the manipulations) with two groups of 18 subjects. One group underwent a sad mood induction procedure and the other a neutral induction procedure. The threat experiment was similar to that of our previous studies examining responses to predictable and unpredictable shocks (Grillon 2008a; b; Grillon et al. 2004). Following attachment of the electrodes, nine startle stimuli (habituation) were delivered every 18–25 sec. This was followed by a shock workup procedure to set up the shock intensity at a level highly annoying and mildly painful. Next, the mood induction procedure was initiated, followed by the threat experiment.

Mood induction procedure (MIP)

Details of the MIP procedure can be found in (Robinson and Sahakian 2009b). Subjects were presented with 60 (sad or neutral) sentences whilst music was played through headphones. Each sentence was presented in the centre of the screen for 12 s until a ‘next’ button appeared and subjects were able to move on to the next sentence by pressing the space bar. Subjects were instructed to ‘relate the situation described by the sentence to situations in their own lives’, to get ‘as deeply as possible into any mood evoked’ and to ‘feel free to outwardly express any mood evoked’. The sad MIP contained light grey text on a dark blue background. The music played was either Adagio for strings, Op. 11 by Samuel Barber or Adagio in G Minor by Tomaso Albinoni. Music was selected by asking the subjects which piece was the ‘saddest’ prior to testing. The neutral, sham, MIP featured black text on a white background and The Planets, Op. 32: VII. Neptune, the Mystic by Gustav Holst was played.

Threat procedure

The procedure consisted of three 150-sec conditions, a no shock condition (N), and two conditions during which shocks were administered either predictably (P), that is, only in the presence of a threat cue, or unpredictably (U). In each condition, an 8-sec cue was presented four times. The cues consisted of different geometric colored shapes for the different conditions (e.g.,blue square for N, red circle for P, green triangle in U). The cues signaled a shock only in the P condition; they had no signal value in the N and U conditions.

Participants were told that they 1) would not receive shock in the no shock condition 2) would be at-risk of receiving a shock only when the cue was on during the predictable condition but not when the cue was absent, and 3) could receive shock at any time in the unpredictable condition. Instructions were also displayed on a computer monitor throughout the experiment displaying the following information: “no shock” (N), “shock only during shape” (P), or “shock at any time” (U). In each N, P, and U condition, six acoustic startle stimuli were delivered. Three stimuli were presented during inter-trial intervals (ITI; i.e., in the absence of cues) and one stimulus was presented during three of the four cues, 5–7 sec following cue onset. Two orders of presentation were created. Each started with the delivery of four startle stimuli (pre-threat startle) and consisted of three N, two P, and two U. The two orders were P N U N U N P or U N P N P N U. Each participant received a single order, with half the participants in each group starting with P and the other half starting with U. One shock was administered in each individual P and U condition for a total of four shocks in P and four shocks in U. In each P, the shock was randomly associated with one of the four threat cues, and administered 7.5 sec following the onset of that cue. The shock was given either 7 sec or 10 sec following the termination of a cue in the unpredictable condition. No startle stimuli followed a shock by less than 10 sec.

Questionnaires

Subjects were given self-administered questionnaires during screening, which included a measure of trait depression, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI)(Beck et al. 1961), and the Tridimensional Personality Questionnaire (TPQ)(Cloninger 1986), a 100-item questionnaire that measures three distinct personality dimensions including a measure of trait anxiety, harm avoidance (HA) (Table 1). The State portion of the State and Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-state)(Spielberger) was administered twice, prior to the MIP and just prior to the threat experiment. A set of visual analog scales VAS was administered to determine self-reported mood; Subjects rated how happy, sad, and depressed they felt from 0 (not at all) to 10 (extremely). This mood rating scale was administered prior to and after the MIP. Another set of VAS was used to evaluate retrospective anxiety in the presence and absence of the cue in each condition (N, P, U) on a VAS scale ranging from 0 (not at all anxious) to 10 (extremely anxious). Subjects were also asked to retrospectively rate the level of shock pain experienced during the threat experiment on an analog scale ranging from 0 (not at all painful) to 10 (extremely painful).

Stimulation and Physiological Responses

Stimulation and recording were controlled by a commercial system (Contact Precision Instruments, London, England). The acoustic startle stimulus was a 40-ms duration, 103-dB (A) burst of white noise presented through headphones. The eyeblink reflex was recorded with electrodes placed under the left eye. The electromyographic (EMG) signal was amplifier with bandwidth set to 30–500 Hz and digitized at a rate of 1000 Hz. The shock was administered on the left wrist.

Data Analysis

The raw eyeblink signal was rectified in a 150-ms window starting 50 ms before the startle stimulus and then integrated using a custom-written scoring program that simulates an integrator circuit with a 10-ms time constant. Peak magnitude of the startle/blink reflex was determined in the 20–100-ms time frame following stimulus onset relative to a 50-ms pre-stimulus baseline and averaged within each condition. The raw scores were transformed into T-scores based across conditions within subjects. The data were then averaged within each condition and stimulus types (ITI, cues). Fear-potentiated startle was defined as the increase in startle magnitudes from ITI to the threat cue in the P condition. Anxiety-potentiated startle was defined as the increase in ITI startle reactivity from N to U. Data were entered into analyses of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures. Note that sex was used as a factor in the ANOVA because we previously reported increased contextual anxiety in females compared to males (Grillon 2008a). Alpha was set at .05 for all statistical tests. Greenhouse-Geisser corrections (GG-ε) were used for main effects and interactions involving factors with more than two levels.

Results

Mood Induction Procedure

The mood scores are shown in Table 2. The mood scores for sad and depressed mood were analyzed in separate MIP (neutral, sad) x Time (pre-MIP, post-MIP) x Sex (males, females) ANOVAs. Sad and depressed mood both showed a significant MIP x Time interaction (F(1,34)=6.1, p=.02 and F(1,34)=5.4, p=.02, respectively) which reflected no change (or only trend for change) following neutral sham MIP, (sad F(1,18)=3.2, p=.08; depressed F(1,18)=2.5, ns) but a significant increase in sad and depressed ratings following sad MIP (F(1,18)=12.5, p<.003 and F(1,18)=10.9, p<.004, respectively). There was no group difference in ‘happy’ ratings following the mood induction procedure.

Table 2.

Mean (sem) mood and state anxiety ratings

| Neutral | Sad | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | Males | Females | |||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| Sad# | .5 (.2) | .8 (.7) | .5 (.2) | .8 (.4) | 1.3 (.2) | 3.1 (.4) | .5 (.2) | 2.2 (.7) |

| Depressed# | .6 (.2) | .9 (.7) | .5 (.2) | .7 (.2) | .7 (.2) | 2.5 (.5) | .6 (.2) | 2.2 (.7) |

| State* anxiety (STAI) |

30.5 (2.) |

31.1 (4.2) |

25.8 (1.4) |

36.0 (2.8) |

24.8 (2.1) |

33.1 (4.2) |

25.4 (1.4) |

37.3 (2.8) |

For mood, post rating was taken just after MIP

For state anxiety, post rating was taken just prior to the threat experiment

Baseline startle magnitude

The startle scores are shown in Table 3. The effect of MIP on baseline startle was investigated by comparing the startle responses before (average of the nine startle responses during habituation) and after (average of the four startle responses prior to the threat procedure) MIP in a MIP (neutral, sad) x Time (pre-MIP, post-MIP) x Sex (males, females) ANOVAs. Baseline startle was not affected by the sad MIP, as suggested by the lack of a MIP x Time interaction, F(1,34)=1.5, ns).

Table 3.

Startle magnitude (T-scores) and subjective anxiety for all trial types. SEM=standard error of the mean. ITI=intertrial interval.

| Mood induction | Conditions | Context | Startle amplitude |

SEM | Subjective anxiety |

SEM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sad | Pre_MIP | – | 53.3 | (1.0) | – | – |

| Post-MIP | – | 51.5 | (2.2) | – | – | |

| Unpredictable | ITI | 55.3 | (1.5) | 7.4 | (.4) | |

| (anxiety) | CUE | 55.5 | (1.0) | 5.6 | (.5) | |

| Predictable | ITI | 49.7 | (1.4) | 4.9 | (.5) | |

| (fear) | CUE | 60.3 | (1.7) | 7.5 | (.4) | |

| No shock | ITI | 40.5 | (0.8) | 1.8 | (.3) | |

| CUE | 41.9 | (1.1) | 1.7 | (.3) | ||

| Neutral | Pre_MIP | – | 54.2 | (1.1) | – | – |

| Post-MIP | – | 55.4 | (2.2) | – | – | |

| Unpredictable | ITI | 52.5 | (1.2) | 7.8 | (.4) | |

| (anxiety) | CUE | 55.0 | (1.1) | 6.5 | (.6) | |

| Predictable | ITI | 49.1 | (1.0) | 4.5 | (.5) | |

| (fear) | CUE | 58.9 | (1.0) | 7.4 | (.4) | |

| No shock | ITI | 42.0 | (0.8) | 2.5 | (.3) | |

| CUE | 41.9 | (1.0) | 1.8 | (.3) | ||

Cued fear-potentiated startle and anxiety-potentiated startle

Fear-potentiated startle was defined as the increase in startle magnitude from the ITI to the threat cue in the predictable condition. Anxiety-potentiated startle was defined as the increase in ITI startle magnitude from the no shock to the unpredictable condition. As shown in Fig. 1, anxiety-potentiated startle but not fear-potentiated startle was increased by the sad MIP.

Figure 1.

Task schematic. Following a startle habituation procedure, subjects underwent a shock workup procedure followed by a neutral or negative Mood Induction Procedure (=MIP and -MIP, respectively), after which the threat of shock experiment started. The threat of shock consisted of three conditions, no shock (N), predictable shock only during cue (P), and unpredictable shock (U).

Fear-potentiated startle (in the predictable condition) was examined using a MIP (neutral, sad) x Stimulus Type (cue, ITI) x Sex (males, females) ANOVA. As expected, there was a highly significant Stimulus Type main effect (F(1,34)=54.6, p<.0009), reflecting larger startle during the cue relative to ITI. Fear-potentiated startle was not significantly affected by the sad MIP, Stimulus Type x MIP interaction, F(1,34)=.4, ns (Fig. 1).

Anxiety-potentiated startle was examined with ITI startle magnitude using a MIP (neutral, sad) x Condition (N, U) x Sex (males, females) ANOVA. As expected (Grillon et al. 2006), startle magnitude during ITI was larger in the U compared to the N condition (Table 3), resulting in a Condition main effect (F(1,34)=111.5, p<.0009). As seen in Fig 1, anxiety-potentiated startle was increased following sad MIP as reflected by a significant MIP x Condition interaction, (F(1,34)=5.0, p<.03). There was no significant difference in baseline startle across groups and this effect did not interact with sex.

Subjective anxiety and pain

The anxiety ratings (Table 3) were analyzed similarly to the startle data using repeated measures ANOVAs. Subjects showed increased fear of the threat cue compared to ITI in the predictable condition, F(1,36)=45.9, p<.0009, but this effect was not modulated by the MIP (no Stimulus Type x MIP interaction; F(1,36)=.23, ns). Similarly, rating of anxiety during ITI increased from the no shock to the unpredictable condition, F(1,36)=276.8, p<.0009, and this effect was not modulated by MIP, F(1,36)=.10, ns. STAI State anxiety scores (Table 2) were analyzed in a MIP (neutral, sad) x Time (pre-MIP, pre-threat) x Sex (males, females) ANOVA. State anxiety increased with time (from pre-MIP to just prior to the threat experiment), F(1,34)=28.6, p<.0009, but this effect was more pronounced in females than males as reflected by a significant Time x Sex interaction, F(1,34)=5.1, p<.03. The pain scores were analyzed using a MIP (neutral, sad) x Sex (males, females) ANOVA. There were no difference between the sad and the neutral MIP groups, F(1,33)=.7, ns, but there was a trend for females to rate the shock as more painful, F(1,33)=3.7, p=.06).

Correlations

We examined personality characteristics associated with the propensity to respond to sad MIP. A composite sad mood scores was created consisting of the mean post-MIP sad and depressed mood scores. In the entire group, sad mood correlated significantly with HA (r=.39, p<.02) and BDI (r=.36, p<.03). However, this effect was essentially attributable to the sad MIP group.

Discussion

Consistent with our hypothesis, healthy individuals demonstrated increased anxiety-potentiated startle following sad mood induction. As such, potentiated startle, which is a reliable indicator of aversive responding, and an indicator of activity within a subcortical neural circuit involving the amygdala and bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (Davis et al. 2010), is facilitated by induced sadness. That is to say, induced sadness serves to exacerbate the impact of subsequently induced anxiety on aversive responding. Moreover, this effect was restricted to the unpredictable condition, which is thought to model anxiety, and was not seen in the predictable condition, which is thought to model fear (Davis et al. 2010; Grillon 2008b).

The present findings thus indicate that sad mood sensitizes the anxiety network (Davis et al. 2010). This is consistent with the observation that induced sad mood increases amygdala activity (Berna et al. 2010; Schneider et al. 1997) and with the observation that induced anxiety (Mechias et al. 2010), induced sad mood (Mayberg et al. 1999), and induced rumination (Cooney et al. 2010) recruit higher prefrontal cortical regions which may be involved in top down control of amygdala responses (Etkin et al. 2011; Ochsner and Gross 2005). As such, sadness may promote hyperactivity within the anxiety network though a top-down neural mechanism.

It is important to note that although startle responses were sensitive to mood, the self report anxiety measures were not. Such dissociation between objective measures and subjective reports are common; non-perceived aversive stimuli can, for instance, elicit amygdala activity in the absence of subjective feeling (Harmer et al. 2003; Kemp et al. 2004). One explanation for the present discrepancy is that startle was measured online during the study, whilst the VAS ratings were retrospective. Moreover, unlike subjective report which is likely cortically-mediated and subject to demand characteristics (Orne 1969), startle is likely subcortically mediated.

Putative relationship with psychiatric conditions

Threat of shock (Davis et al. 2010; Grillon 2008b) has a strong background in translational research and recruits mechanisms implicated in anxiety disorders (AD). Similarly, sad mood induction involves neural and pharmacological mechanisms implicated in affective disorders (Mitchell and Phillips 2007; Robinson and Sahakian 2009a; Robinson and Sahakian 2009b). Testing for interactions between these emotion induction procedures in healthy individuals is one way to assess how these defined mechanisms interact without the many confounds present in patient populations. Of course such models are not a substitute for research in patient populations, but they can provide a more controlled environment in which to develop hypotheses than can be subsequently tested in patient populations. Thus, the present experimental findings are consistent with robust neurocognitive evidence for hyperactive aversive responses in depression (Clark et al. 2009; Elliott et al. 2011; Eshel and Roiser 2010) and partially consistent with studies assessing (short-duration fear) startle responses following negative pictures in depressed individuals. Specifically, just as we fail to see potentiation of short-duration duration fear responses under sad mood, a number of studies have shown that depression fails to increase startle responses to short-duration positive and negative pictures (e.g.,(Allen et al. 1999; Dichter and Tomarken 2008; Dichter et al. 2004; Forbes et al. 2005; Kaviani et al. 2004; McTeague et al. 2009). These studies in fact show reduced startle response, which is likely due to the nature of the stimuli used. Mildly-aversive stimuli such as unpleasant pictures elicit considerably less short-duration fear responding (and associated startle) relative to the physical threat utilized here (Lissek et al. 2007). Of course this difference may also be because the sad mood was not strong enough to mimic depression. However, this unlikely accounts for the difference between the present study and the picture studies for three reasons. First, the MIP did affect anxiety potentiated startle. Second, the MIP used here has been successfully employed on a number of separate occasions (Berna et al. 2010; Robinson et al. 2010; Robinson and Sahakian 2009a; Robinson and Sahakian 2009b). Third, like major depression, sad mood in non depressed subjects is also associated with blunted fear-potentiated startle response to unpleasant pictures (Grüsser et al. 2007).

It should be noted, however, that depression is heterogeneous and the severity and chronicity of the disorder likely affects emotional reactivity. Several studies have shown reduced affective modulation of startle by unpleasant pictures only in severely depressed individuals (Allen et al. 1999; Forbes et al. 2005; Kaviani et al. 2004; Melzig et al. 2007). Moreover, van Eijndhoven et al (2009) found enlargement of the amygdala in first onset, but not recurrent, depression. Taken together these results suggest that responsivity to threat – and potentially concomitant risk for AD – changes as the depression becomes chronic. More specifically, the pattern may be hypersentivity to threat only early on and normal or hyporesponsivity to threat later on. However, further research is necessary to clarify the impact of depression on anxiety- and fear-potentiated startle.

It should also be noted that the sadness which is associated with depression is strongly linked with long-term and persistent ‘rumination’ tendencies (Nolen-Hoeksema et al. 1993). That is to say, once a depressed individual has a sad or aversive emotional response, they tend to dwell and amplify that response or a prolonged period of time (Nolen-Hoeksema 1991). Ruminatory tendencies are ‘especially characteristic’ of individuals with mixed anxiety and depression symptoms (Nolen-Hoeksema 2000). As such, the increased adverse impact of both sadness and induced anxiety may thus be a reflection of a situation whereby sad mood drives ruminations, which then increases anxiety about uncertain future threats and ultimately has a greater negative impact upon startle responses.

Putative Relationship with comorbidity

One potential explanation for high comorbidity between AD and depression is that anxiety and depression are frequently comorbid because they predispose one another. They can exist alone, but they are perhaps mutually reinforcing. That is to say, being anxious might increase the likelihood of becoming depressed, and being depressed may increase the likelihood of becoming anxious, and that feedback between the states means that the ultimate comorbid presentation is associated with greater pathology than either disorder alone.

In support of this hypothesis, there is substantial evidence that AD increase the risk for some types of depression (Brady and Kendall 1992; Kaufman and Charney 2000; Weissman and et al. 1984) and that AD frequently precede depression (Bittner et al. 2004). This sequence is in fact the most common. However depression has been shown to precede or coincide with AD (Kessler et al. 2008; Mineka et al. 1998); across all comorbid anxiety disorders, depression comes first in approximately 40–45% of individuals), and the relationship between adolescent depression and adult generalized anxiety disorder is said to be ‘particularly strong’ (Copeland et al. 2009; Pine et al. 1998). Our experimental design, in which we first induced sad mood, and then we induced anxiety responses could therefore be conceptualized as modeling the latter situation; an individual who suffers from depression and later then goes on to experience AD. Together with the prior evidence that AD can predispose depression (Brady and Kendall 1992; Kaufman and Charney 2000; Mineka et al. 1998; Weissman and et al. 1984), these findings therefore provide initial support for the proposition that depression and AD may be frequently comorbid because they are mutually reinforcing. It should be noted however that AD encompass a wide range of disorders and it may be that the present findings are more relevant for PTSD and panic disorder, which have been shown to be associated with over anxious reactivity to unpredictable aversive events, than phobias. (Grillon et al. 2008; Grillon et al. 2009).

There does not, however, seem to be a common neural mechanism for the mutual reinforcement of these two sets of disorders. Anxiety-driven hyperactivity within the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the accumulation of stressful life experiences plausibly underlies the development of depression following anxiety (Bifulco et al. 1998; Brown et al. 1987; Millan 2008). But how can depression lead to AD? Hypersensitivity of the fear/anxiety network (as indexed by the startle response) is indeed a key risk factor for anxiety disorders (Gorman et al. 2000) and the present findings indicate that such hypersensitivity can be induced by sad mood. The findings are also consistent with the increased amygdala volume in first onset depression relative to recurrent depression (and healthy controls) which is thought to reflect, at least in part, increased volume flow as a state marker of depression as opposed to predisposing structural abnormalities (van Eijndhoven et al. 2009). This initial amygdala enlargement may thus be driven by the above highlighted amygdala hyperactivity with the initial onset of depressed mood.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that induced sadness can increase anxious responding. We emphasize the utility of using experimental models in healthy individuals to provide clues as to the potential underlying mechanism of pathologies in the absence of confounds inherent in heterogeneous psychiatric populations. As such, the present study provides initial experimental support for the proposition that depression may serve to promote AD which, taken together with evidence that anxiety can precipitate depression, provides initial support for the proposition that AD and depression are frequently comorbid because they are mutually reinforcing. In addition, Depression and AD, and especially comorbid depression and AD, are extremely common and debilitating disorders (Mineka et al. 1998). Clarifying the causes of comorbidity is a critical step towards an improved ability to treat the underlying abnormalities (Beddington et al. 2008; Insel et al. 2010).

Figure 2.

Anxiety – not fear - was facilitated by sadness. Anxiety is operationally defined as the difference in ITI startle magnitude between unpredictable shock and no-shock condition. Fear is operationally defined as the difference in startle magnitude between the ITI and cue of the predictable shock condition. Neutral and Sad represent neutral and sad mood induction procedures *p=0.03

Acknowledgment

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Mental Health (MH002798)

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE/CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author(s) declare that, except for income received from the primary employer, no financial support or compensation has been received from any individual or corporate entity over the past 3 years for research or professional service and there are no personal financial holdings that could be perceived as constituting a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Allen NB, Trinder J, Brennan C. Affective startle modulation in clinical depression: preliminary findings. Biological Psychiatry. 1999;46:542–550. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00025-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angst J, Angst F, Stassen HH. Suicide risk in patients with major depressive disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1999;60:57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck A. Depression: Clinical, experimental, and theoretical aspects. Harper & Row. 1967 Harper & Row. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for measuring depression Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1961:561–571. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beddington J, Cooper CL, Field J, Goswami U, Huppert FA, Jenkins R, Jones HS, Kirkwood TBL, Sahakian BJ, Thomas SM. The mental wealth of nations. Nature. 2008;455:1057–1060. doi: 10.1038/4551057a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berna C, Leknes S, Holmes EA, Edwards RR, Goodwin GM, Tracey I. Induction of Depressed Mood Disrupts Emotion Regulation Neurocircuitry and Enhances Pain Unpleasantness. Biological Psychiatry. 2010;67:1083–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierman EJM, Comijs HC, Jonker C, Beekman ATF. Effects of anxiety versus depression on cognition in later life. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2005;13:686–693. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajgp.13.8.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bifulco A, Brown GW, Moran P, Ball C, Campbell C. Predicting depression in women: the role of past and present vulnerability. Psychological Medicine. 1998;28:39–50. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittner A, Goodwin RD, Wittchen HU, Beesdo K, Hofler M, Lieb R. What characteristics of primary anxiety disorders predict subsequent major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:618–626. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady EU, Kendall PC. Comorbidity of anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. Psychological Bulletin. 1992;111:244–255. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.111.2.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Schulberg H, Madonia M, Shear M, Houck P. Treatment outcomes for primary care patients with major depression and lifetime anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153:1293–1300. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.10.1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G, Bifulco A, Harris T. Life events, vulnerability and onset of depression: some refinements. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 1987;150:30–42. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark L, Chamberlain SR, Sahakian BJ. Neurocognitive Mechanisms in Depression: Implications for Treatment. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2009;32:57–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark LA, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:316–336. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR. A unified biosocial theory of personality and its role in the development of anxiety states. Psychiatric developments. 1986;4:167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooney R, Joormann J, Eugène F, Dennis E, Gotlib I. Neural correlates of rumination in depression. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2010;10:470–478. doi: 10.3758/CABN.10.4.470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Costello EJ, Angold A. Childhood and Adolescent Psychiatric Disorders as Predictors of Young Adult Disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:764–772. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis M, Walker DL, Miles L, Grillon C. Phasic vs Sustained Fear in Rats and Humans: Role of the Extended Amygdala in Fear vs Anxiety. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:105–135. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deakin JFW. The role of serotonin in depression and anxiety. European Psychiatry. 1998;13:57s–63s. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(98)80015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter GS, Tomarken AJ. The chronometry of affective startle modulation in unipolar depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2008;117:1–15. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.117.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter GS, Tomarken AJ, Shelton RC, Sutton SK. Early- and late-onset startle modulation in unipolar depression. Psychophysiology. 2004;41:433–440. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.00162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eley TC. Behavioral Genetics as a Tool for Developmental Psychology: Anxiety and Depression in Children and Adolescents. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1999;2:21–36. doi: 10.1023/a:1021863324202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R, Zahn R, Deakin JFW, Anderson IM. Affective Cognition and its Disruption in Mood Disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:153–182. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshel N, Roiser JP. Reward and Punishment Processing in Depression. Biological psychiatry. 2010;68:118–124. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A, Egner T, Kalisch R. Emotional processing in anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2011;15:85–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders—Patient edition (SCID-I/P, 11/2002 Revision) New York State Psychiatric Institute. 2002 New York State Psychiatric Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Forbes EE, Miller A, Cohn JF, Fox NA, Kovacs M. Affect-modulated startle in adults with childhood-onset depression: Relations to bipolar course and number of lifetime depressive episodes. Psychiatry Research. 2005;134:11–25. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman JM, Kent JM, Sullivan GM, Coplan JD. Neuroanatomical Hypothesis of Panic Disorder, Revised. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:493–505. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg PE, Kessler RC, Birnbaum HG, Leong SA, Lowe SW, Berglund PA, Corey-Lisle PK. The economic burden of depression in the United States: how did it change between 1990 and 2000? Jounal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2003;64:1465–1475. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillon C. Greater sustained anxiety but not phasic fear in women compared to men. Emotion. 2008a;8:410–413. doi: 10.1037/1528-3542.8.3.410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillon C. Models and mechanisms of anxiety: evidence from startle studies. Psychopharmacology. 2008b;199:421–437. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1019-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillon C, Baas J. A review of the modulation of the startle reflex by affective states and its application in psychiatry. Clinical Neurophysiology. 2003;114:1557–1579. doi: 10.1016/s1388-2457(03)00202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillon C, Baas JP, Lissek S, Smith K, Milstein J. Anxious Responses to Predictable and Unpredictable Aversive Events. Behavioral Neuroscience. 2004;118:916–924. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.118.5.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillon C, Levenson J, Pine DS. A Single Dose of the Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitor Citalopram Exacerbates Anxiety in Humans: A Fear-Potentiated Startle Study. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;32:225–231. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillon C, Lissek S, Rabin S, McDowell D, Dvir S, Pine DS. Increased Anxiety During Anticipation of Unpredictable But Not Predictable Aversive Stimuli as a Psychophysiologic Marker of Panic Disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:898–904. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07101581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grillon C, Pine DS, Lissek S, Rabin S, Bonne O, Vythilingam M. Increased Anxiety During Anticipation of Unpredictable Aversive Stimuli in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder but not in Generalized Anxiety Disorder. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;66:47–53. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.12.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grüsser S, Wölfling K, Mörsen C, Kathmann N, Flor H. The influence of current mood on affective startle modulation. Experimental Brain Research. 2007;177:122–128. doi: 10.1007/s00221-006-0653-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmer CJ, Rogers RD, Tunbridge E, Cowen PJ, Goodwin GM. Tryptophan depletion decreases the recognition of fear in female volunteers. Psychopharmacology. 2003;167:411–417. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1401-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine DS, Quinn K, Sanislow C, Wang P. Research Domain Criteria (RDoC): Toward a New Classification Framework for Research on Mental Disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:748–751. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jardine R, Martin NG, Henderson AS, Rao DC. Genetic covariation between neuroticism and the symptoms of anxiety and depression. Genetic Epidemiology. 1984;1:89–107. doi: 10.1002/gepi.1370010202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Charney D. Comorbidity of mood and anxiety disorders. Depression and Anxiety. 2000;12:69–76. doi: 10.1002/1520-6394(2000)12:1+<69::AID-DA9>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaviani H, Gray JA, Checkley SA, Raven PW, Wilson GD, Kumari V. Affective modulation of the startle response in depression: influence of the severity of depression, anhedonia, and anxiety. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;83:21–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp AH, Gray MA, Silberstein RB, Armstrong SM, Nathan PJ. Augmentation of serotonin enhances pleasant and suppresses unpleasant cortical electrophysiological responses to visual emotional stimuli in humans. Neuroimage. 2004;22:1084–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Walters EE, Neale MC, Kessler RC, Heath AC, Eaves LJ. The Structure of the Genetic and Environmental Risk Factors for Six Major Psychiatric Disorders in Women: Phobia, Generalized Anxiety Disorder, Panic Disorder, Bulimia, Major Depression, and Alcoholism. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1995;52:374–383. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950170048007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Gruber M, Hettema JM, Hwang I, Sampson N, Yonkers KA. Co-morbid major depression and generalized anxiety disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey follow-up. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:365–374. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Stang PE, Wittchen H-U, Ustun TB, Roy-Burne PP, Walters EE. Lifetime Panic-Depression Comorbidity in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:801–808. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.9.801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lissek S, Orme K, McDowell DJ, Johnson LL, Luckenbaugh DA, Baas JM, Cornwell BR, Grillon C. Emotion regulation and potentiated startle across affective picture and threat-of-shock paradigms. Biological Psychology. 2007;76:124–133. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberg HS, Liotti M, Brannan SK, McGinnis S, Mahurin RK, Jerabek PA, Silva JA, Tekell JL, Martin CC, Lancaster JL, Fox PT. Reciprocal limbic-cortical function and negative mood: Converging PET findings in depression and normal sadness. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156:675–682. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTeague LM, Lang PJ, Laplante M-C, Cuthbert BN, Strauss CC, Bradley MM. Fearful Imagery in Social Phobia: Generalization, Comorbidity, and Physiological Reactivity. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65:374–382. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechias M-L, Etkin A, Kalisch R. A meta-analysis of instructed fear studies: Implications for conscious appraisal of threat. Neuroimage. 2010;49:1760–1768. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melzig CA, Weike AI, Zimmermann J, Hamm AO. Startle reflex modulation and autonomic responding during anxious apprehension in panic disorder patients. Psychophysiology. 2007;44:846–854. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2007.00560.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Zhang H, Avenevoli S, Acharyya S, Neuenschwander M, Angst J. Longitudinal Trajectories of Depression and Anxiety in a Prospective Community Study: The Zurich Cohort Study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:993–1000. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miles L, Davis M, Walker D. Phasic and Sustained Fear are Pharmacologically Dissociable in Rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:1563–1574. doi: 10.1038/npp.2011.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ. State-of-Science Review: SR-E16 Stress-related Mood Disorder: Novel Concepts for Treatment and Prevention. Mental Capital and Wellbeing: UK Government’s Foresight Project; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Mineka S, Watson D, Clark LA. COMORBIDITY OF ANXIETY AND UNIPOLAR MOOD DISORDERS. Annual Review of Psychology. 1998;49:377–412. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.49.1.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell RLC, Phillips LH. The psychological, neurochemical and functional neuroanatomical mediators of the effects of positive and negative mood on executive functions. Neuropsychologia. 2007;45:617–629. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2006.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogg K, Bradley BP, Williams R, Mathews A. Subliminal processing of emotional information in anxiety and depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:304–311. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.2.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:569–582. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S. The role of rumination in depressive disorders and mixed anxiety/depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:504–511. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Morrow J, Fredrickson BL. Response styles and the duration of episodes of depressed mood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1993;102:20–28. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.102.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ochsner KN, Gross JJ. The cognitive control of emotion. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2005;9:242–249. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orne MT. Demand characteristics and the concept of quasi-controls. Artifact in behavioral research. 1969:143–179. [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y. The Risk for Early-Adulthood Anxiety and Depressive Disorders in Adolescents With Anxiety and Depressive Disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:56–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson O, Cools R, Crockett M, Sahakian B. Mood state moderates the role of serotonin in cognitive biases. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2010;24:573–583. doi: 10.1177/0269881108100257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson O, Sahakian B. Recurrence in major depressive disorder: a neurocognitive perspective. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38:315–318. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707001249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson O, Sahakian B. Acute tryptophan depletion evokes negative mood in healthy females who have previously experienced concurrent negative mood and tryptophan depletion. Psychopharmacology. 2009a;205:227–235. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1533-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson OJ, Sahakian BJ. A Double Dissociation in the Roles of Serotonin and Mood in Healthy Subjects. Biological psychiatry. 2009b;65:89–92. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg EL. Levels of analysis and the organization of affect. Review of General Psychology. 1998;2:247. [Google Scholar]

- Sanislow CA, Pine DS, Quinn KJ, Kozak MJ, Garvey MA, Heinssen RK, Wang PS-E, Cuthbert BN. Developing constructs for psychopathology research: Research domain criteria. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2010;119:631–639. doi: 10.1037/a0020909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider F, Grodd W, Weiss U, Klose U, Mayer KR, Nägele T, Gur RC. Functional MRI reveals left amygdala activation during emotion. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging. 1997;76:75–82. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(97)00063-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD. State Trait Anxiety Inventory. Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology. 1996 [Google Scholar]

- Tomarken AJ, Shelton RC, Hollon SD. Affective science as a framework for understanding the mechanisms and effects of antidepressant medication. In: Rottenberg J, Johnson SL, editors. Emotion and psychopathology: Bridging affective and clinical science. Washington, DC: US: American Psychological Association; 2007. p. viii. 336. [Google Scholar]

- van Eijndhoven P, van Wingen G, van Oijen K, Rijpkema M, Goraj B, Jan Verkes R, Oude Voshaar R, Fernández G, Buitelaar J, Tendolkar I. Amygdala Volume Marks the Acute State in the Early Course of Depression. Biological Psychiatry. 2009;65:812–818. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, et al. Depression and anxiety disorders in parents and children: Results from the Yale family study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1984;41:845–852. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790200027004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]