Abstract

Peptides are attracting increasing attention as therapeutic agents, as the technologies for peptide development and manufacture continue to mature. Concurrently, with booming researches in nanotechnology for biomedical applications, peptides have been studied as an important class of components in nanomedicine, and they have been used either alone or in combination with nanomaterials of every reported composition. Peptides possess many advantages, such as smallness, ease of synthesis and modification, and good biocompatibility. Their functions in cancer nanomedicine, discussed in this review, include serving as drug carriers; as targeting ligands; and as protease-responsive substrates for drug delivery.

Traditionally, peptides have been mostly used in polyvalent vaccines [1] or peptide hormones directed against G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) [2], because they have lower affinity and faster clearance compared to antibodies and protein ligands. Developments in targeted cytotoxic drugs (radiotherapeutics and toxins) and imaging probes are in large part responsible for the recently revived interest in peptides [3, 4]. About 60 peptide drugs had combined sales worldwide approaching $13 billion in 2010 [5]. In addition, about 140 peptide drug candidates are in clinical development. About 17 new peptide molecules enter clinical studies every year now, compared to only about 10 during the 1990s and about 5 in the 1980s [5]. Approved peptide drugs and those in development cover many therapeutic areas, such as oncology, metabolic disorders, and cardiovascular disease.

Although monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) and other large protein ligands have been used clinically as therapeutics and studied for targeted delivery [6–8], two major limitations still exist: poor delivery to tumors--due to their large size, which restricts passive diffusion across endothelial cell membranes in capillaries; and dose-limiting toxicity to the liver and bone marrow--due to nonspecific uptake by the liver and the reticuloendothelial system (RES) [9, 10]. The successful use of larger macromolecules, such as mAbs, has therefore been restricted to either vascular targets present on the luminal side of tumor vessel endothelium[8] or hematological malignancies [11]. The advantage of the smaller size of peptides in penetrating tumor has been clearly demonstrated recently [12], where an antibody-mimicking peptide (~3 kDa) showed much greater capacity to target and penetrate tumors than its parent antibody despite having a binding affinity that was only 1–10% of the parent antibody. As a targeted therapy and diagnostics delivery vehicle, the rapid renal clearance of peptides could be the additional advantage since they have potentially lower toxicity to bone marrow and liver.

Although peptides possess well-known advantages as drugs, such as specificity, potency, and low toxicity, they have also suffered from practical hurdles such as poor stability, short half-life, and susceptibility to digestion by proteases. However, extensive research may yield peptide drugs that overcome these barriers in the near future. For example, linaclotide, an oral peptide drug developed by Ironwood Pharmaceutics, is in Phase III clinical trials for irritable bowel syndrome. This cysteine-rich, 18-amino acid peptide with three disulfide bridges is stable enough to be taken orally. Moreover, recent advances in phage display technology, combinatorial peptide chemistry, and biology have led to the identification of a richly varied library of bioactive peptide ligands and substrates, and the development of robust strategies for the design and synthesis of peptides as drugs and biological tools [13–15]. In addition, advances in peptide manufacturing have reduced the cost of manufacturing peptides and have enabled small companies to participate in the development of peptide pharmaceuticals.

In the last few decades, nanoparticles have shown great promise in overcoming the delivery barriers of many traditional pharmaceuticals, and they an emerging drug delivery platform and have been brought into clinics. The combination of peptides and nanoparticles in nanomedicine should further strengthen the advantages of each technology. This review will describe some of the recent advances in using peptides in cancer nanomedicine and will be in three parts: peptides as drug carriers; peptides as targeting ligands; and peptides as protease-responsive substrates in drug delivery. An overview of the peptides described in the review, including their sequences, characteristics, applications and references are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Peptides described in the review: sequence, characteristics, application and reference

| Peptide | Sequence | Characteristics | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug carriers | Cargos | |||

|

| ||||

| MPG | GALFLGFLGAAGSTMGAWSQPKKKRKV | amphiphilic, a lysine-rich domain derived from the nuclear localization sequence (NLS) | DNA and siRNA | [16–27] |

| Pep-1 | KETWWETWWTEWSQPKKKRKV | same hydrophilic domain as MPG, cargo size and nature independent | peptide and protein | [28–31] |

| Pep-2 | KETWFETWFTEWSQPKKKRKV | increased complex stability and potency | PNA | [32] |

| Pep-3 | Ac-KWFETWFTEWPKKRK-Cya | improved cellular uptake | PNA | [33] |

| CADY | Ac-GLWRALWRLLRSLWRLLWRA-Cya | secondary amphiphilic peptide | siRNA | [34] |

| Rath | TPWWRLWTKWHHKRRDLPRKPE | amphiphilic, β structure oligonucleotide, dominant | plasmid, antibody and protein | [35] |

| Penetratin | RQIKIWFQNRRMKWKK | improved retention and even distribution of single-chain Fvs | antibody | [36] |

| VP22 | Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 (HSV-1) structural protein | DNA vaccination | DNA | [37–39] |

|

| ||||

| Targeting ligands | Target | |||

|

| ||||

| SP5-52 | SVSVGMKPSPRP | conjugated to DSPE-PEG liposomes, | tumor neovasculature | [40] |

| PIVO-8 | SNPFSKPYGLTV | conjugated to DSPE-PEG liposomes | tumor angiogenesis | [41] |

| PIVO-24 | YPHYSLPGSSTL | |||

| LyP-1 | CGNKRTRGC | Tumor targeting and cytotoxicity | Tumor hypoxia and tumor-induced lymphangiogenesis | [42–46] |

| RVG | YTIWMPENPRPGTPCDIFTNSRGKRASNG | synthetic chimeric peptide with RVG and oligoarginine residues | acetylcholine receptor expressed by neuronal cells | [47] |

|

| ||||

| Activatable probes | Protease | |||

|

| ||||

| AA | acetylated dipeptide conjugated to DOPE | elastase or proteinase K | [47, 48] | |

| CGLDD | local delivery of chemotherapeutic agents | MMP-2 and -9 | [49] | |

| PVGLIG | dextran-PVGLIG-methotrexate conjugate | MMP-2 and -9 | [50–52] | |

| GPLGIAGQ | conjugated to DOPE for active targeting | MMP-2 | [53] | |

| GKGPLGVRGC | Fe3O4 nanoparticles self-assembly gated by logical prot eolytic triggers | MMP-2 | [54, 55] | |

| GKGVPLSLTMGC | MMP-7 | |||

| SGRSANA | uPA-responsive peptide hydrogel | uPA | [56–58] | |

| GSGRSAGK | protease-triggerable, caged liposomes | uPA | [59] | |

| RVRRSK | Controlled release of encapsulated protein | furin | [60] | |

| PLGLAG | dendrimeric nanoparticles for tumor imaging | MMP-2 and -9 | [61] | |

| GPLGVRGKGG | PEGylated peptide for real-time in vivo MMP imaging | MMP-13 (best) | [62] | |

Peptides as Drug Carriers

Efficient passage through the cellular plasma membrane remains a major hurdle for some drugs—particularly molecules that are large, ionized or highly bound to plasma protein [63]. In 1994, a promising approach for overcoming the cellular barrier for intracellular drug delivery -- cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs or protein transduction domains, PTDs) -- was described by Prochiantz et al. [64]. The first CPP, antennapedia peptide (Antp), was derived from the third helix of the Drosophila melanogaster antennapedia transcription factor homeodomain (amino acids 43–58) [64]. Antp and TAT peptide [65] represent CPPs derived from naturally occurring proteins. A second group contains chimeric CPPs such as transportan (TP), which has 12 amino acids derived from the neuropeptide galanin fused with 14 amino acids derived from the wasp venom mastoparan [66]. A third group contains synthetic CPPs, and of these the polyarginines are the most studied [67]. These peptides have been used for intracellular delivery of various cargos with molecular weights significantly greater than their own [68].

Although it remains difficult to establish a general scheme for a CPP uptake mechanism, there is consensus that the contacts between the CPPs and the cell membrane first take place through electrostatic interactions with proteoglycans, and the cellular uptake pathway is driven by several parameters, including: the primary and secondary structure of the CPP, which determine its ability to interact with cell surface and membrane lipid components; the nature and active concentration of the cargo; the cell type and membrane composition; and experimental conditions such as salt and CPP concentrations [69]. Because CPPs, and especially CPP-cargo conjugates, are known to internalize via endocytosis, endosomal escape is now being considered as a route for efficient CPP–cargo delivery [70, 71].

There are two main strategies in CPP-mediated drug delivery: the first requires covalent linkage with the cargo and the second involves formation of stable, non-covalent complexes. CPPs-based drug delivery technologies described so far mainly focus on the covalent conjugate strategy, which is achieved by chemical cross-linking or by cloning followed by expression of a CPP fusion protein [72–75]. CPPs have been conjugated to different nanocarriers or cargos, and these have been extensively reviewed elsewhere [76–81], so will not be discussed here. The method offers several advantages for in vivo applications, including rationalization, reproducibility of the procedure, and control of the stoichiometry of the CPP-cargo. However, it is limited from a chemical point of view and risks altering the biological activity of the cargo. For instance, coupling siRNA to CPP often led to restricted biological activity [82]. Therefore, non-covalent strategies appear more appropriate.

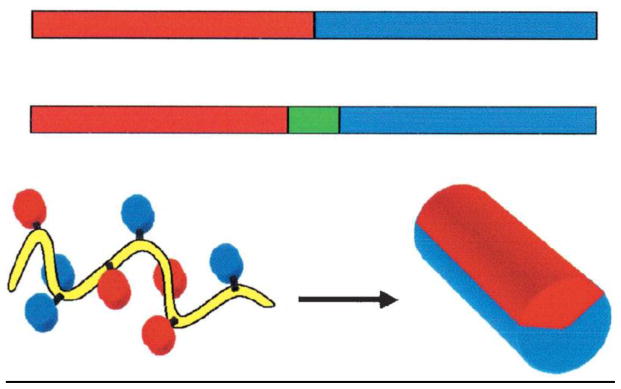

The non-covalent strategy is mainly based on short amphiphilic peptide carriers consisting of a hydrophilic (polar) domain and a hydrophobic (non-polar) domain. The amphiphilic character of such peptides may arise from either their primary structure or secondary structure (Figure 1) [83]. Primary amphiphilic peptides are the result of the sequential assembly of hydrophobic and hydrophilic domains. The hydrophobic domain is required for membrane anchoring and for complexation with hydrophobic cargos. The hydrophilic domain is required for complexation with hydrophilic negatively charged molecules, to target a intracellular compartment, and to improve the solubility of the vector. Most of the secondary amphiphilic peptides used as drug carriers adopt an α-helical structure. After the peptide folding, the hydrophobic and hydrophilic domains usually each occupy one side of the α-helix. Complexation between CPPs and cargo molecules through electrostatic/hydrophobic interactions is illustrated in Figure 2. The non-covalent approach was originally developed for gene delivery; several peptides able to condense DNA associated with peptides that favor endosomal escape, including fusion peptide of HA2 subunit of influenza hemaglutinin have been described [84, 85]. Synthetic peptides analogs such as GALA (WEAALAEALAEALAEHLAEALAEALEALAA) [86], KALA (WEAKLAKALAKALAKHLAKALAKALKACEA) [87], JTS1 (GLFEALLELLESLWELLLEA) [88], ppTG1 (GLFKALLKLLKSLWKLLLKA) [89], MPG (GALFLGFLGAAGSTMGAWSQPKKKRKV) [90] and histidine-rich peptides [91, 92] have also been reported as potent gene delivery systems.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of amphiphilic peptides. Top: the amphiphilic character results from the sequential assembly of hydrophobic and hydrophilic domains. Bottom: the amphiphilic character appears after folding into a helical conformation. Reprinted with permission from ref [83]. Copyright 2005 Springer.

Figure 2.

Non-covalent complexation between CPPs and cargo. Electrostatic and hydrophobic forces facilitate the complexation between CPPs and cargos, such as (from left to right) nucleic acids, proteins and antibodies. Reprinted with permission from ref [79]. Copyright 2009 Elsevier.

MPG (GALFLGFLGAAGSTMGAWSQPKKKRKV) is a primary amphiphilic peptide consisting of three domains. The hydrophobic motif (GALFLGFLGAAGSTMGA) derived from the fusion sequence of the HIV protein gp41 is required for efficient targeting to cell membrane and cellular uptake. The lysine-rich domain (KKKRKV), which is derived from the nuclear localization sequence (NLS) of SV40 large T antigen, is required for its interaction with nucleic acids, intracellular trafficking of the cargo and solubility of the peptide vector. A linker domain (WSQP) bearing a proline residue functions to improve the flexibility and the integrity of both flanking domains [16, 17, 24, 25]. MPG has been applied to both plasmid DNA and oligonucleotide delivery with high efficiency, into a large number of cell types, including adherent and suspension cell lines, cancer and primary cell lines [16–22]. The ability to improve the nuclear translocation of nucleic acids without requiring nuclear membrane breakdown during mitosis could be a unique advantage of MPG, since a dependence on active cell cycle progression is one of the major barriers in gene delivery mediated by many other non-viral vectors [17]. A MPG variant possessing a single mutation in the NLS (MPGΔNLS) could also deliver siRNA into cultured cells with high efficiency (~90% cells). While MPG-transfected fluorescently labeled siRNA localized rapidly into the nucleus, it remained essentially in the cytoplasm when transfected with MPGΔNLS, where it was more efficient in its silencing function than in the nucleus [23].

In addition to in vitro applications, MPG has also been successfully applied to delivery of siRNA in vivo into mouse blastocytes [22] and by topical intratumoral and systemic injections [26, 27]. For instance, based on the study of MPGΔNLS, Divita et al. designed a shortened version of MPG, MPG-8 (βAFLGWLGAWGTMGWSPKKKRK-Cya) and found that MPG-mediated administration of siRNA targeting cyclin B1, a non-redundant mitotic partner of cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (cdk1) [93], prevented PC-3 tumor growth in xenografted tumor mouse models. After intratumoral injection of siRNA complexed with MPG-8, the PC-3 tumor growth was completely inhibited during the 45-day period but tumor volume increased ~2.5 fold in negative control mice. Examination of tumor cyclin B1 mRNA levels showed an 80% knockdown at 5 μg siRNA dose. Further functionalization of MPG-8 with cholesterol improved the in vivo stability of the complex, as complete tumor growth inhibition was achieved by intravenous injection of the complex in an SK-BR3 HER2 model. There was 70% survival at day 40, compared to only 20% survival with the cholesterol-free MPG-8 formulation. Moreover, 50% survival was observed after 100 days following injection of 10 μg every 3 days for 20 days, then every 10 days, demonstrating the long-term effectiveness of this approach. In contrast, no significant effect was observed with non-functionalized MPG-8, suggesting that cholesterol increases the biodistribution of siRNA in the tumor by maintaining siRNA in the plasma.

Pep-1 (KETWWETWWTEWSQPKKKRKV) is also a primary amphiphilic peptide consisting of three domains. Its lysine-rich hydrophilic domains (KKKRKV) are the same as those of MPG, but it differs in its hydrophobic domains. The hydrophobic motif of Pep-1 corresponds to a tryptophan-rich cluster (KETWWETWWTEW), which is required for efficient targeting to the cell membrane and for hydrophobic interactions with proteins. Pep-1 carrier promotes the cellular uptake of small peptides and large proteins, independently of their nature and size, into a large panel of cell types [94, 95]. The Pep-1 strategy has also been applied to delivery of proteins and peptides in vivo in different animal models, via intravenous, intratracheal, and intratumoral injections, transduction into oocytes and topical application [28–31]. Several modifications of Pep-1 have also been proposed to stabilize the peptide/cargo complex or to extend the potency of this strategy to other cargo molecules. Pep-2 (KETWFETWFTEWSQPKKKRKV) differs from Pep-1 essentially by two Phe residues at positions 5 and 9, which replace Trp residues in the hydrophobic domain [32]. Morris et al. also showed that it formed stable complexes with uncharged peptide nucleic acids (PNAs) and derivatives, such as HyPNA-pPNAs, and significantly improved their cellular uptake.

Since the helical structure of Pep-1 enables its aromatic residues to interact with membrane lipids and, consequently, favors membrane disorganization, a 15-residue peptide Pep-3 (Ac-KWFETWFTEWPKKRK-Cya) (Cya = cysteamide) was designed to promote cellular uptake [33]. The potency of Pep-3 for HypNA-pPNA delivery was evaluated using antisense targeting cyclin B1, an essential component of “Mitosis Promoting Factor” [93]. Intratumoral injection of Pep-3/HypNA-pPNA in PC-3 xenografted mice was shown to potently inhibited tumor growth in a concentration-dependent manner, with more than 92% for 5 μg of antisense HypNA-pPNA. Moreover, xenografted mice were treated intravenously with 10 μg of antisense HypNA-pPNA complexed in formulations containing up to 15% of PEGylated-Pep-3, achieving inhibition of tumor growth by more than 90%, which was 4–5-fold more efficient than with un-PEGylated Pep-3 [96]. Together, these data clearly demonstrate that Pep-3 could be a potential candidate for in vivo delivery of charged PNA and DNA mimics.

Based on chimeric peptide carrier ppTG1 derived from the fusion peptide JTS1, Divita et al. designed the first secondary amphiphilic peptide, CADY (Ac-GLWRALWRLLRSLWRLLWRA-Cya), combining aromatic tryptophan and cationic arginine residues [34]. CADY adopts a helical conformation within cell membranes, thereby exposing charged residues on one side, and Trp groups that favor cellular uptake on the other. It has high affinity for siRNA with an apparent dissociation constant of 15.2 ± 2 nM and binding saturation was reached at a CADY/siRNA molar ratio ranging between 5/1 and 10/1. Furthermore, no significant siRNA degradation to serum nuclease was observed at high molar ratios (40/1 and 80/1). Significantly, when delivering GAPDH siRNA into challenging cell lines (suspension THP1, primary HUVEC and 3T3C cell lines), the mRNA levels associated with GAPDH knockdown were reduced by >80% with 20 nM siRNA, irrespective of the cell type, and IC50 values were estimated as ~3.4±0.5, 1.5±0.1, and 1.2±0.1 nM respectively. No significant toxicity was associated with siRNA/CADY, and viability was >80% in all cell lines. It would be interesting to see if the peptide can achieve the same gene knockdown in vivo. In a later review, the authors mentioned that CADY was capable of in vivo delivery of siRNA with a high efficiency at low doses, without any side toxic effects [97]. Unfortunately, the in vivo results have not been published so far.

In a study by Chindera et al., a novel peptide, Rath (TPWWRLWTKWHHKRRDLPRKPE), derived from VP5 protein of avian infectious bursal disease virus (IBDV), for plasmid DNA and oligonucleotide delivery was described [35]. The biophysical characterizations showed that the amphiphilic Rath has a dominant β structure, unusual for CPPs, with a small α helix and has remarkable binding ability with protein and DNA. It can protect plasmid DNA from serum and DNAse I. The delivery is rapid (30 min for an oligonucleotide and 1 h for an antibody) and can be achieved at low temperature as well as room temperature indicating an endocytosis independent pathway as shown by some other peptides such as MPG [98] and the third α-helix of the antennapedia homeodomain, “Penetratin” [99]. This is favorable as it avoids endosomal entrapment and improves bioavailability. Lastly, the Rath peptide can deliver IgG antibody, GFP, and oligonucleotide into Vero cells and chicken embryonic fibroblast (CEF) primary cells, more challenging targets than immortalized cell lines. Although the transfection efficiency was not compared to that of other common delivery agents, this versatility may be used to deliver multiple agents at the same time for cancer applications.

In addition to nucleic acid delivery, CPPs can also be harnessed for protein delivery. In 1999, Dowdy and colleagues reported the first in vivo application of CPPs. They showed that TAT-β-galactosidase fusion protein can be delivered into almost all tissues including the brain, following intra-peritoneal injection into mice [100]. Since then, CPPs have been successfully used to deliver peptides and proteins targeting different diseases including cell proliferation/cancer, asthma, apoptosis, ischaemia, stimulating cytotoxic immunity and diabetes (see ref [101–104] for some recent reviews). Although most of these applications use CPPs (TAT, penetratin, polyarginine, VP22) covalently linked to peptides or as fusion proteins, a few examples have illustrate the non-covalent strategy, including the previously mentioned peptides Pep-1 [94] and Rath [35]. In another study, penetratin was shown to improve tumor retention of single-chain Fv antibodies for radioimmunotherapy [36]. The major impediments of monoclonal antibody-based radiopharmaceuticals include long circulation time and extremely poor penetration, both attributable to the higher molecular weight of intact IgG. Jain et al. showed that co-administration of penetratin and single-chain Fv antibody resulted in improved retention and even distribution of single-chain Fvs, without affecting the peak dose accumulation. The rare use of non-covalent strategy for peptide-mediated protein delivery reflects the difficulties in transferring high molecular weight molecules. Careful selection of peptides with high affinity to proteins, retained membrane transduction ability and intact protein function is needed in further research.

The herpes simplex virus (HSV-1) protein VP22 has received extensive attention in the field of DNA vaccination [37–39]. It has been shown that VP22 can form particles 0.3 to 1 μm in diameter with short oligonucleotides; and that these particles were stable in serum and tissue culture medium and can enter cells efficiently within 2 to 4 h [105]. Most importantly, when DNA constructs of VP22 and a protein of interest are transfected in a subpopulation of cells, the expressed protein can be transported to the adjacent cells [106]. Therefore, VP22 enables the spread of the antigenic peptide to cells surrounding the transfected cells. When primary keratinocytes, CHO-S, COS-7L, or HEK-293-F cell lines were transfected with a DNA construct composed of VP22 and a T cell epitope of Anaplasma marginale sequences, a 150-fold increase was seen in intercellular spreading of the T cell epitope expression when VP22 was present in the construct [107]. When macrophages and DC were co-cultured with the transfectants, this resulted in improved DC antigen presentation and led to enhanced epitope-specific T cell proliferation. This improvement in the immunogenicity of DNA vaccines by VP22 has also been observed in other disease models, such as influenza virus [108], bovine herpes virus 1 (BHV-1) [109, 110], porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus (PRRSV) [111], and human papillomavirus (HPV) [112].

In addition to being effective against viral infections, DNA vaccination incorporating VP22 was also able to promote tumor protection in vivo [37]. When mice were vaccinated with VP22-linked model antigen, human papilloma virus type 16 E7 (VP22/E7), it induced CD8+ T cell precursors and provoked antitumor immunity against the E7-expressing tumor model. In contrast, the non-spreading VP221-267 mutants failed to show effectiveness. Moreover, a separate study by Wu et al. showed an increase in E7-expressing DCs in the draining lymph nodes, greater number of E7 memory cells, and enhanced long-term antitumor immunity after vaccination [39]. Overall, these studies indicated that VP22-mediated DNA delivery could improve the efficacy of DNA vaccination for cancer immunotherapy.

Progress in the development of CPP-mediated drug delivery, as discussed above, has been encouraging and the prospects of significant advances in many disease areas are exciting. In principle, a broad range of therapeutic targets can be reached by CPP-mediated (covalent or non-covalent) drug delivery, as shown in this review and many other publications. In practice, as with any drug candidate, bioavailability, possible toxicity, pharmacokinetics, and pharmacodynamics are very important parameters for CPP-mediated drug delivery. These parameters depend on the nature of the CPP, the linker design (in covalent strategies), the characteristics of the CPP-cargo complex, and the specific cargo. Cargo-specific CPP design will be essential to the development of safe and effective therapeutics. Furthermore, progress in CPP-mediated drug delivery depends on a better understanding of the entry mechanisms of CPPs into cells and the intracellular trafficking of CPPs and their cargoes. For cancer applications, tumor cell targeting (passive, active or both) should result in improved drug efficiency, reduced side effects (a major burden for patients in current systemic cancer treatment), and increased therapeutic window. This could lead to the ability to target specific cell and tissue types and to control the fate of cargoes inside cells. Characterization of the structure-activity relationship of individual CPPs will allow tailoring of specific CPPs to particular intracellular targets and optimization of potency. The next session will describe the peptides studied as targeting ligands.

Peptides as Targeting Ligands

Most traditional drug delivery methods (except for time-release formulations) release drugs instantaneously, and it can result in peak concentrations that are toxic to tissues. The non-targeted distribution of the drugs can cause undesired effects at sites other than those intended. Moreover, many drugs partially degrade before they reach the desired site, leading to a reduction in therapeutic effects. In 1958, the first attempt to deliver a ligand-directed drug to leukemic cells was published by Matte et al. [113]. Since then, advances in chemistry, biology and engineering techniques have given rise to a flourishing of various specific targeting systems successful in directing attached drugs to desired disease sites. Proteins and peptides, carbohydrates, vitamins, antibodies, and aptamers are the common ligands used to increase the specificity of targeting systems.

Among these, peptides have many combined advantages: they are smaller than antibodies, can be synthesized by chemical methods at a large scale, and can achieve high specificity. Accordingly, anticipated improvements in conjugation techniques can be expected to further increase their application in diagnosis and therapy. The main strategy to select proper peptide ligands is to screen peptide libraries produced by either phage display [114, 115] or chemical synthesis [116], while the former method is more widely applied. Phage display can be used to identify peptides that target a specific receptor, if it is already known, or certain cell types even if the receptors are unknown [117]. Moreover, phage display is adaptable to both in vitro and in vivo studies [118]. To date, numerous peptide ligands have been discovered for various types of receptors or cells, such as integrin receptors [119, 120], thrombin receptors [121], tumor cells [122–124], cardiomyocytes [125], and pancreatic β cells [126]. A summary of peptides targeting various tumors can be found in ref [127]. Tumor-targeting peptides have been successfully incorporated in vehicles that deliver targeted imaging agents, small-molecule drugs, oligonucleotides, liposomes, and inorganic nanoparticles to tumors. Other peptide-related nanoparticles, such as peptide aptamers and peptidomimetic self-assembled nanoparticles, also have shown great potential in targeted drug delivery. The former are more frequently used directly as drugs interfering with the function of receptors [128], while the later have more expanded applications in tumor imaging, tumor-targeting delivery and vaccination [129]. The use of these peptides has increased the specificity and efficacy of drug delivery while reducing side effects [130, 131]. The recent discoveries of tumor lymphatic vessel-targeting peptides present an alternative route for targeted drug delivery into tumors [42, 132, 133]. So far, the most widely used peptides in the targeted delivery applications are still integrin-targeted RGD peptides, the first tumor-targeting peptide discovered. The RGD peptide has been extensively studied and reviewed [134–138] [135, 139–142], therefore, this article will mainly discuss some other targeting peptide sequences.

Wu et al. reported that the peptide SP5-52 (sequence: SVSVGMKPSPRP), identified by in vivo phage display, conjugated specifically to PEGylated distearoylphosphatidyl ethanolamine (DSPE-PEG) liposomes targeted tumor blood vessels [40]. Several selected phage clones displayed the consensus motif, proline-serine-proline, and this motif was crucial for peptide binding to the tumor neovasculature. SP5-52 recognized tumor neovasculature but not normal blood vessels in xenograft mice models. Furthermore, this targeting phage was shown to home to tumor tissues from eight different types of human tumor xenografts following in vivo phage display experiments; tumor tissues from these eight different cancer cell lines contained >8-fold more SP5-52 than normal organs. After the peptide was conjugated onto PEG-DSPE liposomes containing doxorubicin, it was shown to inhibit the angiogenesis of tumors, resulting in increased therapeutic efficacy and higher survival rates of both human lung and oral cancer xenograft mice.

Chang et al. identified new angiogenesis targeting peptides PIVO-8 (sequence: SNPFSKPYGLTV) and PIVO-24 (sequence: YPHYSLPGSSTL) by in vivo phage display [41]. DSPE-PEG liposomes were modified with PIVO-8 and PIVO-24, and the targeting peptides were found to specifically home to tumor tissues from lung, colon, breast, prostate, pancreatic, liver, and oral cancer xenografts, but not to normal tissues from organs such as the brain, lung, or heart. A closer examination revealed that they were co-localized with endothelial markers in most xenograft vasculatures but only rarely detected in tumor cells or normal organs. Moreover, targeting liposomes containing doxorubicin were able to suppress tumor growth significantly more than non-targeting liposomes in the seven cancer xenograft models [41].

LyP-1, a nine-amino acid cyclic peptide (sequence: CGNKRTRGC), is a unique tumor-targeting peptide which has cytotoxic activity on its own [42]. In a mouse breast cancer xenograft model, it inhibited tumor growth and reduced the number of lymphatic vessels, the latter of which might indicate an effect on the lymphatic spread of tumor metastases [42, 43]. In addition to the lymphatic vessels, LyP-1 appeared to localize in areas of hypoxia within the tumor. Tumor cells in these areas tend to be resistant to chemotherapeutic agents, which generally target dividing cells. There is also growing evidence indicating that these cells are genetically unstable and a significant source of metastasis. Thus, the ability of LyP-1 to deliver payloads to these otherwise difficult-to-access sites may open up new possibilities in tumor therapy [44]. In addition, fluorescein-conjugated LyP-1 was used as an imaging tool in MDA-MB-435 tumor-bearing mice; following intravenous injection, LyP-1 was taken up by targeted tumor cells, where its payload, fluorescein, concentrate in nuclei, allowing whole body imaging of the tumors in mice (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Specific accumulation of lymphatic homing peptide LyP-1 in tumors. 16–20 h after mice bearing MDA-MB-435 xenograft tumors were injected i.v. with (A) fluorescein-conjugated LyP-1 or (B) a fluorescein-conjugated control peptide (ARALPSQRSR). (C) LyP-1 produced intense fluorescence in the tumor, whereas no fluorescence was detectable in other organs. (D) No fluorescence was observed in the control peptide-injected tumor. Adapted from ref with permission. Reprinted with permission from ref [42]. Copyright 2004 National Academy of Sciences.

Using LyP-1 as the targeting ligand, Sailor et al. presented a cooperative nanosystem consisting of two discrete nanomaterials [45]. The first component was gold nanorod (NR) “activators” that populated the porous vessels of tumors and acted as photothermal antennas to facilitate tumor heating via remote near-infrared laser irradiation. It was found that local tumor heating accelerated the recruitment of the second component: targeted nanoparticles consisting of either magnetic nanoworms (NW) or doxorubicin loaded liposomes (LP). LyP-1, the targeting species, could bind to the stress-related protein, p32, which was found to be upregulated on the surface of tumor-associated cells upon thermal treatment. Mice containing xenografted MDA-MB-435 tumors that were treated with the combined NR/LyP-1LP therapeutic system displayed significant reductions in tumor volume compared to those that did not receive infrared irradiation or that were treated with individual nanoparticles.

Most recently, our group successfully employed Cy5.5-labeled LyP-1 for in vivo imaging of tumor-induced sentinel lymph node lymphangiogenesis [46]. Tumor-induced lymph node (LN) lymphangiogenesis usually precedes metastasis and leads to increased tumor spread to distal LNs and further to distal organs. It has been shown to be associated with the presence of non-sentinel LN metastases in animal tumor models and human breast cancer and melanoma [93]. Between day 7 and day 21 after inoculation with 4T1 cells, although the size of tumor-draining LNs did not change significantly, the fluorescent intensity from the injected probe kept increasing, indicating that the lymphatic vessel density increased with time. Moreover, even 24 h after Cy5.5-LyP-1 injection, much stronger fluorescent signals could be measured inside tumor-draining LNs than after injection of non-conjugated Cy5.5, confirming specific binding of this peptide probe to lymphatic vessels. The results demonstrated that Cy5.5-LyP-1 facilitated visualization of the expansion of lymphatic networks within the tumor-draining sentinel LNs, even before tumor metastasis occurred.

Manjunath et al. reported the successful in vivo transvascular delivery of siRNA to the central nervous system (CNS) of mice using a synthetic chimeric peptide consisting of a rabies virus glycoprotein (RVG) peptide and oligoarginine residues [47]. RVG is a 29-amino-acid peptide that specifically binds to the acetylcholine receptor expressed by neuronal cells. To enable siRNA binding, a chimeric peptide was synthesized by adding nonamer arginine residues at the carboxy terminus of RVG to create RVG-9R. When GFP siRNAs were complexed with the positively charged RVG-9R peptide and injected intravenously into GFP transgenic mice for three consecutive days, GFP expression was significantly decreased in the brain but not in the liver or spleen, confirming the specificity of brain targeting. Similar results were obtained when siRNA against SOD1 was used; siRNA was only detected in the brain but not in the spleen or liver after treatment (Figure 4). Remarkably, it was found that robust protection from lethal infection was achieved after treatment of mice with RVG-9R/siRNA complexes that target the Japanese encephalitis virus. This brain cell targeting peptide that penetrates the blood-brain barrier has since been incorporated into liposomes [143] and exosomes [144]. Although no cancer-related application has been reported, it has the potential to targeting brain tumor, provided that cell-specific targeting within the CNS can be achieved.

Figure 4.

Brain-specific gene silencing after i.v. injection of siRNA/RVG-9R complex. (a) After injection of GFP siRNA/peptide complex, brain, spleen and liver cells were analyzed for GFP expression. Histograms (top) and cumulative data (bottom) are shown. Dotted lines in the upper panel, cells from wild-typemice; grey fill, mock; black lines and columns, RV-MAT-9R; red lines and columns, RVG-9R. (b) After injection of SOD1 siRNA/peptide complexes, brain, spleen and livers were examined for SOD1 mRNA (top) and SOD1 protein (bottom) levels. Black columns, RV-MAT-9R (C); red columns, RVG-9R (T). The numbers below the western blot represent the ratios of band intensities of SOD-1 normalized to those of β-actin. (c) Small RNAs isolated from different organs of SOD1 siRNA/RVG-9R injected mice were probed with siRNA sense strand oligonucleotide. Antisense strand oligonucleotide was used as a positive control (first and last lanes). (d) Mice were injected intravenously with SOD siRNA/RVG-9R, and the duration of gene silencing was determined by quantification of SOD1 mRNA levels (top) and SOD1 protein enzyme activity (bottom) on the indicated days after siRNA administration. Reprinted with permission from ref [47]. Copyright 2007 Nature Publishing Group.

Despite only a few recent examples are discussed here, peptides as targeting ligands of nanoparticles are steadily gaining momentum in cancer research. Peptide ligands, mostly created by phage display or other reiterative random library approaches, have been successfully used as targeting agents even though their target epitopes are still in the process of discovery. Peptides derived from different larger proteins or ligands are rapidly being developed for targeting as well. Their small size compared to protein ligands, yet high targeting ability, makes them easy to produce and modify, and could yield favorable pharmacokinetics in vivo. The targeting peptides are often fused with other functional peptides, such as CPPs, or attached to nanoparticles to facilitate drug delivery. Although this review mainly describs their use in drug delivery systems, peptides have also been widely employed in cancer molecular imaging as reviewed in some recent publications [145–149]. As the number of targeting peptide–nanoconjugate examples increases, new ideas on how to use these polyvalent assemblies keep emerging. New ways to combine targeting peptides with other functional peptides and with various diagnostic or therapeutic molecules have been made available by the rapid progress of nanobiotechnology, and these novel agents often afford very different properties than the starting materials used in the preparation of them. Moreover, peptide targeting itself is becoming combinatorial — with the use of more than one peptide in a single entity, the use of peptides that also serve as proteolytic substrates to provide more function etc. These discoveries and the experience gained could yield completely novel approaches to cancer treatment by nanomedicine.

Peptides in responsive drug delivery systems

The genetic instructions for proteases (or proteinase) account for about 2% of the human genome, and the pivotal roles that proteases play in regulatory pathways makes them useful as prognostic indicators and as important targets for a large number of existing drugs as well as drugs that are still under development [150]. Proteolysis is a simple hydrolytic cleavage of the amide bond between two adjacent amino acid residuescatalyzed by proteases. Without the catalytic assistance of protease, protein hydrolysis would be a very slow process. Proteolytic activities are strictly regulated through various mechanisms. For example, intracellular proteolysis is regulated by segregation within organelles such as lysosomes. Some proteases are expressed as pro-enzymes, while others are complexed with natural enzyme-inhibitors. Their enzymatic properties can be restored only when needed. As diseases initiate, mis-regulation of enzymatically active proteases, or launching of new foreign proteases, can occur, resulting in various host responses. Since proteases are catalytic enzymes, one protease molecule could specifically activate hundreds, or even thousands of its substrates. If molecular probes are designed to be the substrates of the proteases they target, this amplification of signal could be expected [151].

Cancer-associated proteases (CAPs) have gained attraction recently as a new method of tumor targeting. CAPs are a set of proteases that are usually absent from or at very low concentrations in healthy tissues but are often highly up-regulated in cancerous tissues. Some of extensively studied CAPs include urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA), many of the matrix metalloproteases (MMP), and some of the cathepsins [152–156]. Developing a prodrug, a drug delivery system, or an imaging agent that could be cleaved and activated by CAPs could be a workable method for targeting drugs/imaging agents to tumor sites [157–161].

As one of the earliest examples, protease-activatable liposomes were designed by conjugating an acetylated dipeptide substrate (N-Ac-AA) through its carboxyl terminus to the amino group of 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE) to promote cellular internalization [48]. The resulting peptide-lipid (N-Ac-AA-DOPE), together with dioleoyl trimethylammonium propane (DOTAP) and phosphatidyl-ethanolamine (PE), were assembled into non-fusogenic liposomes. The liposomes were activated by elastase or proteinase K to become fusogenic for enhanced intracellular delivery (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

(A) The lipid-peptide N-Ac-AA-DOPE can be converted into DOPE by elastase. (B) The liposome is stable with negatively charged surface. Removal of N-Ac-AA by elastase results in charge reversal, thus enhancing its ability to fuse with the plasma membrane for drug delivery. Reprinted with permission from ref [162]. Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society.

MMPs, probably the most studied CAPs for tumor-responsive drug delivery, are a family of at least 24 zinc-dependent endoproteases. They can degrade most components of the extracellular matrix and basement membrane, thus contribute to the formation of a microenvironment permissive of tumor growth, angiogenesis and metastasis [163, 164]. A number of MMPs have been shown to be associated with tumor cell invasion evidenced by a positive correlation between the extent of local tissue penetration and MMP levels.[164–166] In addition, MMPs are able to cleave a wide range of non-matrix substrates, including those involved in apoptosis, cell dissociation, cell–cell communication and cell division [163, 164, 166, 167]. Extensive studies have shown frequent over-expression of several MMPs in many forms of human tumor [168–172]. These studies demonstrated a clear relationship between increased MMP expression and poor clinical outcome in a number of cancers including breast (MMP-11), colon (MMP-1), gastric (MMP-2 and MMP-9), non-small cell lung cancer (MMP-13), esophageal (MMP-7), and small-cell lung cancer (MMP-3, MMP-11 and MMP-14) [169, 171]. Furthermore, the expression of specific MMPs has been shown to serve as both a prognostic indicator of clinical outcome and a marker of tumor progression in a wide range of tumor types [168, 170, 171, 173, 174]. Therefore, MMPs are attractive targets for protease-sensitive drug delivery.

For instance, MMP-activatable wafers have been developed for local delivery of chemotherapeutic agents [49]. Cisplatin complexed with an MMP substrate (CGLDD) was incorporated into PEG-diacrylate hydrogel wafers. Drug release was dependent on MMPs (MMP-2 and MMP-9) expressed in a conditioned U87MG cell culture media. Another example is dextran-PVGLIG-methotrexate conjugate. The prodrug was cleaved by both MMP-2 and MMP-9 [50], which led to the release of peptidyl methotrexate fragments to inhibit tumor growth [175]. However, the tumor targeting mechanism relied predominantly on the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. The same approach has been applied to other diseases, such as choroidal neovascularization (CNV) [51] and myocardial infarction [52], because the affected tissues also exhibit anatomical characteristics similar to those of a tumor (i.e. hyperpermeable vessels and lack of effective lymphatic drainage).

In another study by Hashida et al., PEGylated GPLGIAGQ, a MMP-2 substrate, was conjugated to the amino group of DOPE [53]. When assembled with disteraoyl phosphatidylcholine (DSPC), cholesteryl chloroformate, and cholesten-5-yloxy-N-(4-((1-imino-2-,β-D-thiogalactosyl ethyl)amino)butyl)formamide (Gal-C4-Chol) [176], the resulting liposomes (Gal-PEG-PD) were composed of: galactose moieties targeting the hepatic cell surface asialoglycoprotein receptors; and a PEGylated peptide substrate of MMP-2. In the absence of the protease, Gal-PEG-PD-liposomes could not be taken up by normal hepatocytes because of steric shielding of the targeting ligands by PEG chains. After the addition of MMP-2, the protease cleaved its substrate and PEG was removed, thus exposing the galactose ligands for targeting. The cytotoxicity of N-(4)-octadecyl-1-β-D-arabinofuranosylcytosine (NOAC) incorporated Gal-C4-PD liposomes was significantly enhanced in cultured HepG2 cells after pretreatment with purified human MMP-2.

In contrast to the common methods where proteolysis causes the disassembly of nanoparticles, and subsequently facilitates the release of cargo from the carrier, Bhatia et al. took the opposite approach. They prepared two kinds of Fe3O4 nanoparticles tethered with biotin (ligand) and neutravidin (receptor) respectively, which were stable separately, but aggregated readily when combined [54]. Their self-assembly amplified the T2 relaxation rate of hydrogen protons, enabling remote, MRI-based detection of logical function. When the two groups were masked by anchoring PEG polymer to the NPs through MMP-2 and MMP-7 substrate respectively, self-assembly could be restricted to occur only in the presence of both enzymes (Logical AND) (Figure 6). Furthermore, when PEG polymers were anchored only to the ligand NP through a tandem peptide substrate (containing both protease substrates in series), the self-assembly was actuated in the presence of either or both of the enzyme inputs (Logical OR). Harris et al. extended this principle by anchoring PEG polymer to a cell internalization domain with MMP-2 substrate on the surface of Fe3O4 NPs [55]. The PEG coating conferred favorable circulation and accumulation properties in vivo; while within tumor where MMP-2 was up-regulated, the peptide substrate was cleaved and the exposed cell internalization domain “turn on” the cellular uptake of the NPs. Fluorescent and MRI imaging in tumor-bearing mice showed enhanced fluorescent signal and greater decrease of T2 relaxation time compared to non-cleavable NPs, which confirmed the role of MMP-2 proteolysis in NP cellular uptake.

Figure 6.

Logical nanoparticle sensors. Self-Assembly is gated to occur in the presence of both MMP-2 and MMP-7 (Logical AND) (Left) or in the presence of either or both proteases (Logical OR) (Right) by attachment of protease-removable PEG polymers. Reprinted with permission from ref [54]. Copyright 2007 American Chemical Society.

uPA is a well-studied CAP that is thought to be involved primarily in angiogenesis and perhaps in tissue remodeling during invasion and metastasis. The consensus sequence for uPA is known to be SGRSA [58, 177]. A uPA-responsive hydrogel based on the KLD-12 peptide (Ac-KLDLKLDLKLDL) was reported to control the release of a cytotoxic peptide r7-kla [56]. The peptide KLD-12 was able to form a self-assembled matrix via β-sheet stacking [57, 178]. The core peptide sequence consisted of a uPA substrate sequence (SGRSANA) [179] flanked by two self-assembly motifs with D-configuration. In aqueous solution, the peptides self-assembled as a gel scaffold. In the presence of uPA, cleavage of the protease substrate from the assembled matrix occurred and thus fragmented the building blocks, which in turn weakened the β-sheet interactions and caused matrix degradation. Further, it has been demonstrated that urokinase could trigger release of a cytotoxic peptide, r7-kla, that was anchored in a matrix [56].

Recently, Bossmann et al. prepared protease-sensitive liposomes based on the polymer-caged liposome concept (Figure 7) [59]. The cholesterol-anchored, graft copolymer, composed of a short peptide sequence for uPA and poly(acrylic acid), was incorporated into liposomes (DPPC:DOPC:cholesterol = 47.5:5:47.5) prepared at high osmolarities. Upon cross-linking of the polymers, the caged liposomes showed significant resistance to osmotic swelling and leaking of contents at physiological osmolarity. In the presence of uPA, the polymer was degraded and the liposomes rapidly swelled and released their contents, while bare liposomes showed no differential effect. Although this study only used fluorescein as a model drug and no cell-based experiments were involved, it showed the potential of increasing the specificity of liposomal carriers and preventing nonspecific leaking of payloads.

Figure 7.

Proposed mechanism of protease-sensitive liposome. Upon dilution into physiological osmolarity, the protease-triggerable, caged liposomes do not release their contents. When treated with protease uPA, the polymer is degraded, allowing the liposome to swell osmotically and release its contents, or possibly to fuse (in vivo) with nearby planar membranes. Reprinted with permission from ref [59]. Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society.

Tang and colleagues described a biomimetic protein delivery vehicle which was degradable upon digestion by furin to release encapsulated protein cargos [60]. Furin (53 kDa) is a ubiquitous proprotein convertase expressed in all eukaryotic organisms, including many mammalian cells [180, 181]. It is localized in various intracellular locations and has a preferred substrate RX(K/R)R [182]. Proteins were non-covalently encapsulated in a nanosized matrix prepared with two monomers, acrylamide (AAm) and positively charged N-(3-aminopropyl) methacrylamide (APMAAm), and a bisacrylated peptide cross-linker (Ahx-RVRRSK) which can be specifically recognized and cleaved by furin. The resulting nanocapsules were 10–20 nm and positively charged. CD spectra indicated that the secondary structure of encapsulated eGFP remained unchanged during the entire assembly and disassembly process and was identical to that of native eGFP in solution. When the nanocapsules were incubated with furin, 80% of the encapsulated eGFP was released over 10 hours, compared to only minimal release in the absence of furin. In vitro cell culture studies demonstrated successful intracellular delivery of both nuclear (transcription factor Klf4) and cytosolic (caspase-3) proteins and confirmed the importance of furin-degradable construction for native protein release.

In addition to drug delivery, the up-regulated expression of disease-associated proteases in diseased tissues and the catalytic characteristic of proteolysis have made protease-activatable imaging probes an attractive approach for molecular imaging. In general, the principal mechanism of activation is based on quenching-dequenching upon proteolytic cleavage. All probes are designed to have little or no fluorescence signal in their native state, and to become highly fluorescent after protease-mediated release of fluorochromes, which result in significant signal amplification. This activatable approach has at least three advantages over traditional imaging probes: (1) there is minimized background signal; (2) a single protease can activate multiple probes; and (3) the same template may be applied to multiple enzymes. There are several detailed reviews that describe activatable probes that work in conjunction with MMPs, caspases, cathepsins, thrombin, HSV, etc. [183–185].

As an example, Tsien et al coated dendrimeric nanoparticles with activatable cell penetrating peptides (ACPPs) targeting MMP-2 and MMP-9, labeled with Cy5, gadolinium, or both [61]. Residual tumor and metastases as small as 200 μm could be detected by fluorescence imaging. MRI imaging showed that Gd-labeled nanoparticles deposited high levels (30–50 μM) of Gd in tumor parenchyma (with even higher amounts deposited in regions of infiltrative tumor), resulting in useful T1 contrast lasting several days after injection. Our group recently reported the first real-time in vivo video imaging of extracellular protease expression [62]. The imaging probe consists of an MMP substrate peptide GPLGVRGKGG, flanked with Cy5.5 at the N-terminal and PEG (four different molecular weights ranging from 200–3000) at the C-terminal, as well as a quencher BHQ-3 conjugated at the lysine side chain. Probes with small molecular weight PEG (200 and 500) showed significantly reduced activation time (as early as 30 minutes) and sustained strong fluorescent signal (up to 24 h) in vivo after administered intravenously into MMP-positive SCC-7 tumor-bearing mice.

However, a study by Grull et al. proposed that tumor targeting of MMP-2/9 activatable cell-penetrating imaging probes is caused by tumor-independent activation [186]. They found that ACPP administration to healthy mice, compared to MMP-2/9-positive tumor-bearing mice, resulted in a similar ACPP biodistribution. Furthermore, a radio-labeled cell-penetrating peptide showed tumor-to-tissue ratios equal to those found for non-ACPP. This implied that tumor targeting is most likely caused by the activation in the vascular compartment rather than tumor-specific activation. Clearly, more mechanistic studies and tissue-specific activatable probes are needed to unleash the full potential of protease-activatable drug carriers and imaging probes.

Development of “smart” biomaterials by exploiting increased endoprotease activity at disease sites is an area of drug development showing great promise. Indeed, discoveries of a wide variety of cellular signaling pathways associated with disease-associated proteases have already led to the development of numerous prodrugs, functional biomaterials (including nanoparticles), and imaging probes. Generally, such pharmacophores and/or imaging probes are restrained or masked by various carefully-designed mechanisms; then, proteolysis by target proteases releases or unmasks the active ingredients chemically or physically, producing the desired therapeutic activity or imaging sensitivity in situ. Furthermore, as proteolysis is a catalytic reaction, one protease could potentially release a large number of active ingredients. Thus, the catalytic function could amplify signal outputs and improves detection limits significantly for disease detection and diagnosis. In addition to improving tumor-selective delivery of cancer therapeutics or imaging probes, these protease-sensitive nanoparticles could function to reduce their undesired activity/signal in normal tissues, including liver, heart and bone marrow.

Despite the advantages and promise shown by protease-responsive nanoparticles, some issues remain for future development and realization in clinical use. Since disease-associated protease activities vary by individual and by stage of disease, greater understanding is required of targeting protease structures, mechanisms, distribution, and regulation in vivo. Also, overlapping substrate specificities between closely related protease families must be understood and addressed in future designs of activatable probes. Finally, as with any other nanoparticles or nano-assemblies, the properties of the whole particles will largely determine their in vivo fates and performance and, thus, should be carefully designed and characterized.

Conclusions

Despite a dramatic acceleration in the discovery of new and highly potent therapeutic molecules, many have not achieved clinical use due to poor delivery, low bioavailability, and/or lack of specific targeting. Kong and Mooney pointed out in 2007, for example, that delivery is key in therapeutic development [187]. Fortunately, abundant evidence suggests that nanomedicine can provide methods to overcome these hurdles. Among the vast diversity of materials used to prepare nanoparticles, peptides possess many advantages: they are relatively small, can be synthesized by chemical methods on a large scale, can be facilely conjugated to other molecules, and have low generic cytotoxicity. Moreover, peptides can be designed to have many functions; they themselves can be therapeutic drugs, can be structural components of nano-sized carriers, can bind to specific targets with high affinity, can facilitate cellular delivery of cargos (including therapeutic and imaging agents), and can be the substrates of disease site-specific stimuli, such as protease. This review has pointed out some of the recent advances in non-covalent peptide-based drug delivery, peptides (other than RGD) as targeting ligands and peptides in protease-sensitive nanocarriers. It showed that peptides have been widely studied in nanomedicine and numerous pre-clinical successes have been achieved.

In the past few years, the use of peptides in theranostic nanomedicine (multifunctional nanoparticles that combine therapeutic and diagnostic functions within a single nanoscale complex) has drawn increasing attention [188–194]. The imaging components of these platforms have been utilized for early stage detection of disease (including tumors), imaging-guided drug delivery and release, and treatment response monitoring etc. The characteristics of peptides mentioned above are especially suitable for imaging, since they can achieve target-specific accumulation and signal amplification, hence high signal-to-background ratios. With the further development of theranostic nanomedicine, the role of peptides will continue to expand.

Depending on the applications, limitations of peptides may include: rapid renal clearance, insufficient disease site targeting and accumulation, undesired cargo release and in vivo instability. No matter the nature of the delivery system, major attention must be paid to the targeting and controlled release of the carrier/cargo into specific tissues and to limit the dispersion in non-targeted areas. In other words, the physicochemical and pharmacochemical properties of nano-complexes as a whole must be carefully designed and characterized to implement their desired functions. As the challenges in discovery, development, and manufacturing are being met, combined with continued research, peptide-based nanotheranostics will play an increasingly role in cancer diagnosis and therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the intramural research program of the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), National Institutes of Health (NIH). This work was performed while X-X Zhang held a National Research Council Research Associateship Award at NIH/NIBIB.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors claim no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ragupathi G, Gathuru J, Livingston P. Antibody inducing polyvalent cancer vaccines. Cancer Treat Res. 2005;123:157–180. doi: 10.1007/0-387-27545-2_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dorsam RT, Gutkind JS. G-protein-coupled receptors and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:79–94. doi: 10.1038/nrc2069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reubi JC. Peptide receptors as molecular targets for cancer diagnosis and therapy. Endocr Rev. 2003;24:389–427. doi: 10.1210/er.2002-0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shrivastava A, Wronski MAv, Sato AK, Dransfield DT, Sexton D, Bogdan N, Pillai R, Nanjappan P, Song B, Marinelli E, DeOliveira D, Luneau C, Devlin M, Muruganandam A, Abujoub A, Connelly G, Wu QL, Conley G, Chang Q, Tweedle MF, Ladner RC, Swenson RE, Nunn AD. A distinct strategy to generate high-affinity peptide binders to receptor tyrosine kinases. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2005;18:417–424. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzi049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thayer AM. Improving peptides. Chem Eng News. 2011;89:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen TM. Ligand-targeted therapeutics in anticancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:750–763. doi: 10.1038/nrc903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pastan I, Hassan R, Fitzgerald DJ, Kreitman RJ. Immunotoxin therapy of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6:559–565. doi: 10.1038/nrc1891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thorpe PE. Vascular targeting agents as cancer therapeutics. Cancer Res. 2004;10:415–427. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0642-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aina O, Sroka T, Chen M, Lam K. Therapeutic cancer targeting peptides. Biopolymers. 2002;66:184–189. doi: 10.1002/bip.10257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mori T. Cancer-specific ligands identified from screening of peptide-display libraries. Curr Pharm Des. 2004;10:2335–2243. doi: 10.2174/1381612043383944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reff ME, Hariharan K, Braslawsky G. Future of monoclonal antibodies in the treatment of hematologic malignancies. Cancer Control. 2002;9:152–166. doi: 10.1177/107327480200900207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qiu X, Wang H, Cai B, Wang L, Yue S. Small antibody mimetics comprising two complimentarity-determining regions and a framework region for tumor targeting. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:921–929. doi: 10.1038/nbt1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hruby VJ. Designing peptide receptor agonists and antagonists. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:847–858. doi: 10.1038/nrd939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aina OH, Liu R, Sutcliffe JL, Marik J, Pan C-X, Lam KS. From combinatorial chemistry to cancer-targeting peptides. Mol Pharm. 2007;4:631–651. doi: 10.1021/mp700073y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrenko VA. Evolution of phage display: from bioactive peptides to bioselective nanomaterials. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2008;5:825–836. doi: 10.1517/17425247.5.8.825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morris MC, Chaloin L, Mery J, Heitz F, Divita G. A novel potent strategy for gene delivery using a single peptide vector as a carrier. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27:3510–3517. doi: 10.1093/nar/27.17.3510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simeoni F, Morris MC, Heitz F, Divita G. Insight into the mechanism of the peptide-based gene delivery system MPG: implications for delivery of siRNA into mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2717–2724. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris MC, Vidal P, Chaloin L, Heitz F, Divita G. A new peptide vector for efficient delivery of oligonucleotides into mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:2730–2736. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.14.2730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simeoni F, Morris MC, Heitz F, Divita G. Peptide-based strategy for siRNA delivery into mammalian cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2005;309:251–264. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-935-4:251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morris KV, Chan SWL, Jacobsen SE, Looney DJ. Small interfering RNA-induced transcriptional gene silencing in human cells. Science. 2004;305:1289–1292. doi: 10.1126/science.1101372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Langlois MA, Boniface C, Wang G, Alluin J, Salvaterra PM, Puymirat J, Rossi JJ, Lee NS. Cytoplasmic and nuclear retained DMPK mRNAs are targets for RNA interference in myotonic dystrophy cells. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:16949–16954. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M501591200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nguyen QN, Chavli RV, Marques JT, Conrad PG, Wang D, He WH, Belisle BE, Zhang AG, Pastor LM, Witney FR, Morris M, Heitz F, Divita G, Williams BRG, McMaster GK. Light controllable siRNAs regulate gene suppression and phenotypes in cells. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758:394–403. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simeoni F, Morris M, Heitz F, Divita G. Insight into the mechanism of the peptide-based gene delivery system MPG: implications for delivery of siRNA into mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:2717–2724. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morris MC, Depollier J, Mery J, Heitz F, Divita G. A peptide carrier for the delivery of biologically active proteins into mammalian cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:1173–1176. doi: 10.1038/nbt1201-1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris MC, Depollier J, Mery J, Heitz F, Divita G. A peptide carrier for the delivery of biologically active proteins into mammalian cells: application to the delivery of antibodies and therapeutic proteins. Handbook of Cell Biology. 2006;4:13–18. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crombez L, Charnet A, Morris MC, Aldrian-Herrada G, Heitz F, Divita G. A non-covalent peptide-based strategy for siRNA delivery. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:44–46. doi: 10.1042/BST0350044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zeineddine D, Papadimou E, Chebli K, Gineste M, Liu J, Grey C, Thurig S, Behfar A, Wallace VA, Skerjanc IS, Puceat M. Oct-3/4 dose dependently regulates specification of embryonic stem cells toward a cardiac lineage and early heart development. Dev Cell. 2006;11:535–546. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Aoshiba K, Yokohori N, Nagai A. Alveolar wall apoptosis causes lung destruction and emphysematous changes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2003;28:555–562. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0090OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rawe VY, Payne C, Navara C, Schatten G. WAVE1 intranuclear trafficking is essential for genomic and cytoskeletal dynamics during fertilization: cell-cycle-dependent shuttling between M-phase and interphase nuclei. Dev Biol. 2004;276:253–267. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.07.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Payne C, Rawe V, Ramalho-Santos J, Simerly C, Schatten G. Preferentially localized dynein and perinuclear dynactin associate with nuclear pore complex proteins to mediate genomic union during mammalian fertilization. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:4727–4738. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maron MB, Folkesson HG, Stader SM, Walro JM. PKA delivery to the distal lung air spaces increases alveolar liquid clearance after isoproterenol-induced alveolar epithelial PKA desensitization. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:349–354. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00134.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morris MC, Chaloin L, Choob M, Archdeacon J, Heitz F, Divita G. Combination of a new generation of PNAs with a peptide-based carrier enables efficient targeting of cell cycle progression. Gene Ther. 2004;11:757–764. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3302235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Deshayes S, Heitz A, Morris MC, Charnet P, Divita G, Heitz F. Insight into the mechanism of internalization of the cell-penetrating carrier peptide Pep-1 through conformational analysis. Biochemistry. 2004;43:1449–1457. doi: 10.1021/bi035682s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Crombez L, Aldrian-Herrada G, Konate K, Nguyen QN, McMaster GK, Brasseur R, Heitz F, Divita G. A new potent secondary amphipathic cell–penetrating peptide for siRNA delivery into mammalian cells. Mol Ther. 2009;17:95–103. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baisa MV, Kumar S, Tiwari AK, Kataria RS, Nagaleekar VK, Shrivastava S, Chindera K. Novel Rath peptide for intracellular delivery of protein and nucleic acids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;370:27–32. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jain M, Chauhan S, Singh A, Venkatraman G, Colcher D, Batra S. Penetratin improves tumor retention of single-chain antibodies: a novel step toward optimization of radioimmunotherapy of solid tumors. Cancer Res. 2005;65:7840–7846. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hung CF, Cheng WF, Chai CY, Hsu KF, He L, Ling M, Wu TC. Improving vaccine potency through intercellular spreading and enhanced MHC class I presentation of antigen. J Immunol. 2001;166:5733–5740. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.9.5733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Peng S, Trimble C, Ji H, He L, Tsai YC, Macaes B, Hung CF, Wu TC. Characterization of HPV-16 E6 DNA vaccines employing intracellular targeting and intercellular spreading strategies. J Biomed Sci. 2005;12:689–700. doi: 10.1007/s11373-005-9012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim TW, Hung CF, Kim JW, Juang J, Chen PJ, He L, Boyd DAK, Wu TC. Vaccination with a DNA vaccine encoding herpes simplex virus type 1 VP22 linked to antigen generates long-term antigen-specific CD8-positive memory T cells and protective immunity. Hum Gene Ther. 2004;15:167–177. doi: 10.1089/104303404772679977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee T-Y, Lin C-T, Kuo S-Y, Chang D-K, Wu H-C. Peptide-mediated targeting to tumor blood vessels of lung cancer for drug delivery. Cancer Res. 2007;67:10958–10965. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chang D-K, Chiu C-Y, Kuo S-Y, Lin W-C, Lo A, Wang Y-P, Li P-C, Wu H-C. Antiangiogenic targeting liposomes increase therapeutic efficacy for solid tumors. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:12905–12916. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900280200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Laakkonen P, Akerman ME, Biliran H, Yang M, Ferrer F, Karpanen T, Hoffman RM, Ruoslahti E. Antitumor activity of a homing peptide that targets tumor lymphatics and tumor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9381–9386. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403317101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Luo G, Yu X, Jin C, Yang F, Fu D, Long J, Xu J, Zhan C, Lu W. LyP-1-conjugated nanoparticles for targeting drug delivery to lymphatic metastatic tumors. Int J Pharm. 2010;385:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Karmali PP, Kotamraju VR, Kastantin M, Black M, Missirlis D, Tirrell M, Ruoslahti E. Targeting of albumin-embedded paclitaxel nanoparticles to tumors. Nanomed Nanotechnol Biol Med. 2009;5:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2008.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Park J-H, Maltzahn Gv, Xu MJ, Fogal V, Kotamraju VR, Ruoslahti E, Bhatia SN, Sailor MJ. Cooperative nanomaterial system to sensitize, target, and treat tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:981–986. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909565107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang F, Niu G, Lin X, Jacobson O, Ma Y, Eden HS, He Y, Lu G, Chen X. Imaging tumor-induced sentinel lymph node lymphangiogenesis with LyP-1 peptide. Amino Acids. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s00726-00011-00976-00721. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumar P, Wu H, McBride JL, Jung K-E, Kim MH, Davidson BL, Lee SK, Shankar P, Manjunath N. Transvascular delivery of small interfering RNA to the central nervous system. Nature. 2007;448:39–45. doi: 10.1038/nature05901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pak CC, Ali S, Janoff AS, Meers P. Triggerable liposomal fusion by enzyme cleavage of a novel peptide-lipid conjugate. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1372:13–27. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(98)00041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tauro JR, Gemeinhart RA. Matrix metalloprotease triggered delivery of cancer chemotherapeutics from hydrogel matrixes. Bioconjug Chem. 2005;16:1133–1139. doi: 10.1021/bc0501303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chau Y, Tan FE, Langer R. Synthesis and characterization of dextran-peptide-methotrexate conjugates for tumor targeting via mediation by matrix metalloproteinase II and matrix metalloproteinase IX. Bioconjug Chem. 2004;15:931–941. doi: 10.1021/bc0499174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kimura H, Yasukawa T, Tabata Y, Ogura Y. Drug targeting to choroidal neovascularization. Adv Drug Del Rev. 2001;52:79–91. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lukyanov A, Hartner WCN, Torchilin V. Increased accumulation of PEG-PE micelles in the area of experimental myocardial infarction in rabbits. J Controlled Release. 2004;94:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2003.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Terada T, Iwai M, Kawakami S, Yamashita F, Hashida M. Novel PEG-matrix metalloproteinase-2 cleavable peptide-lipid containing galactosylated liposomes for hepatocellular carcinoma-selective targeting. J Controlled Release. 2006;111:333–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maltzahn Gv, Harris TJ, Park J-H, Min D-H, Schmidt AJ, Sailor MJ, Bhatia SN. Nanoparticle self-assembly gated by logical proteolytic triggers. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:6064–6065. doi: 10.1021/ja070461l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Harris TJ, Maltzahn Gv, Lord ME, Park J-H, Agrawal A, Min D-H, Sailor MJ, Bhatia SN. Protease-triggered unveiling of bioactive nanoparticles. Small. 2008;4:1307–1312. doi: 10.1002/smll.200701319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Law B, Weissleder R, Tung C-H. Peptide-based biomaterials for protease-enhanced drug delivery. Biomacromolecules. 2006;7:1261–1265. doi: 10.1021/bm050920f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kisiday J, Jin M, Kurz B, Hung H, Semino C, Zhang S, Grodzinsky AJ. Self-assembling peptide hydrogel fosters chondrocyte extracellular matrix production and cell division: implications for cartilage tissue repair. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:9996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.142309999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu S, Bugge TH, Leppla SH. Targeting of tumor cells by cell surface urokinase plasminogen activator-dependant anthrax toxin. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:17976–17984. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011085200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Basel MT, Shrestha TB, Troyer DL, Bossmann SH. Protease-sensitive, polymer-caged liposomes a method for making highly targeted liposomes using triggered release. ACS Nano. 2011;5:2162–2175. doi: 10.1021/nn103362n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Biswas A, Joo K-I, Liu J, Zhao M, Fan G, Wang P, Gu Z, Tang Y. Endoprotease-mediated intracellular protein delivery using nanocapsules. ACS Nano. 2011;5:1385–1394. doi: 10.1021/nn1031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Olson ES, Jiang T, Aguilera TA, Nguyen QT, Ellies LG, Scadeng M, Tsien RY. Activatable cell penetrating peptides linked to nanoparticles as dual probes for in vivo fluorescence and MR imaging of proteases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:4311–4316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0910283107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhu L, Xie J, Swierczewska M, Zhang F, Quan Q, Ma Y, Fang X, Kim K, Lee S, Chen X. Real-time video imaging of protease expression in vivo. Theranostics. 2011;1:18–27. doi: 10.7150/thno/v01p0018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peck T, Hill S. Pharmacology for anaesthesia and intensive Care. 3. Cambridge University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Derossi D, Joliot AH, Chassaing G, Prochiantz A. The third helix of the antennapedia homeodomain translocates through biological membranes. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:10444–10459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Vivés E, Brodin P, Lebleu B. A truncated HIV-1 Tat protein basic domain rapidly translocates through the plasma membrane and accumulates in the cell nucleus. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:16010–16017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.25.16010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pooga M, Hällbrink M, Zorko M, Langel U. Cell penetration by transportan. FASEB J. 1998;12:67–77. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.12.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rothbard J, Garlington S, Lin Q, Kirschberg T, Kreider E, McGrane P, Wender P, Khavari P. Conjugation of arginine oligomers to cyclosporin A facilitates topical delivery and inhibition of inflammation. Nat Med. 2000;6:1253–1257. doi: 10.1038/81359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schwarze SR, Dowdy SF. In vivo protein transduction: intracellular delivery of biologically active proteins, compounds and DNA. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2000;21:45–48. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01429-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.El-Andaloussi S, Holm T, Langel U. Cell-penetrating peptides: mechanisms and applications. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:3597–3611. doi: 10.2174/138161205774580796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wadia J, Stan R, Dowdy S. Transducible TAT-HA fusogenic peptide enhances escape of TAT-fusion proteins after lipid raft macropinocytosis. Nat Med. 2004;10:310–315. doi: 10.1038/nm996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Magzoub M, Pramanik A, Gräslund A. Modeling the endosomal escape of cell-penetrating peptides: transmembrane pH gradient driven translocation across phospholipid bilayers. Biochemistry. 2005;44:14890–14897. doi: 10.1021/bi051356w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gait MJ. Peptide-mediated cellular delivery of antisense oligonucleotides and their analogues. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:844–853. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3044-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zatsepin TS, Turner JJ, Oretskaya TS, Gait MJ. Conjugates of oligonucleotides and analogues with cell penetrating peptides as gene silencing agents. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:3639–3654. doi: 10.2174/138161205774580769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moulton HM, Moulton JD. Arginine-rich cell-penetrating peptides with uncharged antisense oligomers. Drug Discov Today. 2004;9:870–870. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(04)03226-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nagahara H, Vocero-Akbani AM, Snyder EL, Ho A, Latham DG, Lissy NA, Becker-Hapak M, Ezhevsky SA, Dowdy SF. Transduction of full-length TAT fusion proteins into mammalian cells: TAT-p27(Kip1) induces cell migration. Nat Med. 1998;4:1449–1452. doi: 10.1038/4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Torchilin VP. Cell penetrating peptide-modified pharmaceutical nanocarriers for intracellular drug and gene delivery. Biopolymers. 2008;90:604–610. doi: 10.1002/bip.20989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mae M, Langel U. Cell-penetrating peptides as vectors for peptide, protein and oligonucleotide delivery. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6:509–514. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]