Abstract

Glioblastoma is universally fatal because of its propensity for rapid recurrence due to highly migratory tumor cells. Unraveling the genomic complexity that underlies this migratory characteristic could provide therapeutic targets that would greatly complement current surgical therapy. Using multiple high-resolution genomic screening methods, we identified a single locus, Adherens Junctional Associated Protein 1 (AJAP1) on chromosome 1p36, that is lost or epigenetically silenced in many glioblastomas. We found AJAP1 expression absent or reduced in 86% and 100% of primary glioblastoma tumors and cell lines, respectively, and the loss of expression correlates with AJAP1 methylation. Restoration of AJAP1 gene expression by transfection or demethylation agents results in decreased tumor cell migration in glioblastoma cell lines. This work demonstrates the significant loss of expression of AJAP1 in glioblastoma and provides evidence of its role in the highly migratory characteristic of these tumors.

Keywords: AJAP1 (Adherens junctional associated protein), glioblastoma, malignant glioma, methylation, gene deletion, epigenetics, migration

Introduction

Glioblastoma is one of the most common and most malignant primary brain tumors in adults(CBTRUS, 2008). Successful resection of >98% of the tumor alone only provides about 8 months of survival because tumor cells have invariably begun migrating away from the visible primary tumor focus. Adjuvant chemo- and radiotherapies provide some benefit. In a recent meta-analysis, an increase in median survival, from 12.1 to 14.6 months was observed in glioblastoma patients after multimodal therapy with gross total resection, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy with the alkylating drug temozolomide (Stupp et al., 2005).

In order to make significant strides in glioblastoma treatment, novel insights into the biology of these tumors are required. Recent genome-wide studies continue to elucidate the common genetic changes and altered signaling cascades in glioblastoma (2008; Rich et al., 2005). These studies also highlight the large number of genetic changes due to the acquired mutator phenotype that may not play a central role in tumor initiation, proliferation, or cell migration (Loeb, 1991). Despite the plethora of genetic alterations seen in glioblastoma, most revealing genetic studies have typically implicated only a few altered signaling pathways, namely, activating events in the PTEN or receptor tyrosine kinase pathways and decreased activity in the RB1 or TP53 signaling cascades (2008; Kanu, 2009).

For many cancers the distal arm of chromosome 1p has been a mutational hotspot. A variety of human cancers, including glioblastoma, neuroblastoma, oligodendroglioma, leukemia, lymphoma, squamous cell carcinoma, breast cancer, and prostate cancer frequently have genetic deletions at 1p36. In glioblastoma, methylation appears to be a common event that also silences gene expression of tumor suppressor genes, including RB1, p16INK4a, p14ARF, MGMT, TIMP3 (Ohgaki and Kleihues, 2007), TMS1/ASC (Martinez et al., 2007a; Stone et al., 2004), CASP8 (Martinez et al., 2007b), RUNX3, and RES (Mueller et al., 2007). Unfortunately, the vast majority of these genetic and epigenetic events have yet to provide meaningful therapeutic or prognostic markers, except possibly for the case of MGMT (Hegi M.E., 2005).

One unfortunate characteristic of glioblastoma is its robust propensity to migrate from the primary focus of tumor initiation to distant sites and to recur despite aggressive local and system therapies. Effective therapies that could impede this process of tumor cell migration could provide potentially curative adjunctive therapy to the current standard of care. Adherens Junctional Associated Protein-1 (AJAP1; also known as Shrew1) has recently been discovered as a novel transmembrane component of adherent junctions in epithelial cells (Bharti et al., 2004).

Materials and Methods

Tumor samples

Tumor samples (>95% pure tumor) were obtained from the Duke Preston Robert Tisch Brain Tumor Center Tissue Biorepository in accordance with an IRB-approved protocol. Normal brain tissue from patients without brain tumors was obtained at the time of autopsy and frozen at −80°C before DNA and RNA isolation.

Digital karyotyping

Digital karyotyping libraries were constructed as previously described (Wang et al., 2002). Eighteen glioblastoma libraries (14 adult and 4 pediatric) were generated and the data combined with 9 glioblastoma libraries from TCGA database, for a total of 27 libraries. Digital karyotyping protocols and software for extraction and analysis of genomic tags are available at http://www.digitalkaryotyping.org.

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)

Using the TCGA Data Portal at http://tcga-data.nci.nih.gov/tcga/findArchives.htm we downloaded all copy number data generated at the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. All normal blood, normal tissue, cell line, and duplicate data were removed yielding 221 glioblastoma primary tumors for analysis. TCGA raw data was reformatted for analysis by Nexus Copy Number Professional software (Biodiscovery, Inc, Segundo, CA).

Rembrandt

Data regarding expression, copy number, and survival obtained from http://tr.nci.nih.gov/rembrandt website, release date 11-13-09. This dataset included 506 samples for gene expression data, 722 for copy number data, and 891 for clinical data.

Illumina’s HumanHap 550 Quad and 610 Duo Genotyping BeadChips

The Illumina BeadChips enable whole-genome genotyping of over 555,000 and 610,000 tag SNP markers, respectively, derived from the International HapMap Project (www.hapmap.org). Thirty-five tumors were analyzed by the 550 chip, and another 43 tumors were analyzed by the 610 chip for a total of 78 unique samples. Blood and normal cortex were included. Genomic DNA was isolated with the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), hybridized to the BeadChip microarrays, and data analyzed by using Illumina BeadStudio software. Illumina raw data was reformatted by Nexus.

Serial Analysis of Gene Expression (SAGE)

SAGE data were reviewed on the NCBI Cancer Genome Anatomy Project repository (http://cgap.nci.nih.gov/SAGE). Additionally, we identified the SAGE sequence tags for the AJAP1 locus previously published [Supplemental Table S8 in (Parsons et al., 2008)].

RNA extraction, cDNA synthesis, quantitative PCR (Q-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated by using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and reverse-transcribed by using an iScript™cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). cDNA amplification was monitored by using a SYBR Green protocol (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) on a 7900HT Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Forward and reverse primers were designed at different exons. GAPDH was used as control. Quantitative values were obtained from the threshold cycle (Ct) number at which the increase in the signal associated with exponential growth of PCR products could first be detected by using SDS2.2.2 software (Applied Biosystems). The transcript level of AJAP1 gene was normalized to that of GAPDH. As a reference, we used adult human brain RNA (BioChain Institute, Hayward, CA).

Bisulfite Treatment of DNA and Methylation-Specific quantitative PCR

Genomic DNA was isolated from fresh-frozen tissue samples and cell lines using Wizard® Genomic DNA Purification Kit (Promega, Madison, WI). Using Methprimer (http://urogene.org/methprimer), we performed a CpG island search throughout intragenic and promoter regions up to 3000 bp upstream of the start site for AJAP1. Bisulfite modification of genomic DNA was performed using EZ DNA Methylation-Gold Kit™ (Zymo, Orange, CA). Methylation-specific qPCR was carried out with 2 µl of bisulfite-treated DNA using a SYBR Green PCR Kit (Qiagen) on an ABI PRISM 7900 HT system (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Two sets of methylation-specific and two sets of unmethylation specific primers were used. The percentage of methylation in each tumor specimen was calculated by the following equation: % meth = 100/[1ΔCt(meth-unmeth)]%. ΔCt(meth-unmeth) was calculated by subtracting the Ct values of methylated AJAP1 signal from the Ct values of unmethylated AJAP1 signal. Each sample was run in duplicates for analysis.

Cell culture and drug treatment

Cell lines were maintained in Improved MEM Zinc Option Medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% FBS at 37°C, 5% CO2. For demethylation studies, glioma cells were seeded in six-well plates, allowed to attach overnight and treated with 5 µ/L 5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine (AZA) (Sigma) for 4 days, followed by a 24-h treatment with 0.1 µmol/L Trichostatin A (TSA) (Sigma). In control groups, the same concentration of dimethyl sulfoxide was used to treat cells. Fresh drug and medium were changed every 24 h.

AJAP1 expression plasmids

The AJAP1 cDNA was isolated from normal cortex by a PCR and subcloned into the pEGFP-N1 expression plasmid. The pAJAP1-EGFP expression plasmid was transfected with Lipfectamine2000 (Invitrogen). The expression of AJAP1 was confirmed by fluorescence microscope and Western blot (Supplementary Figure S6).

AJAP1 knockdown studies

Two different siRNA oligonucleotides for AJAP1 inhibition (AJAP1 Stealth RNAi™ siRNA HSS148198 and AJAP1 Stealth RNAi™ siRNA HSS148199), and scrambled siRNA for negative control were obtained (Invitrogen). A total of 2 × 105 GBM cells were seeded in 6-well plates and grown to 90% confluency in 1.5 mL culture medium. After treatment, cells were then washed with PBS and transfected by Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) and siRNA dissolved in Opti-MEM I Reduced Serum Medium without FBS (0.5 nmol/L) per well according to manufacturer’s recommendations. Cells were maintained in transfection medium overnight and subsequently in culture medium for 48 h and then added to migration assay as described below. RNA knockdown was determined by cDNA synthesis as previously described and visualization on agarose gel. At 48h, the loss of AJAP1 was optimal, so this time was selected for the procedure and applied in all knockdown experiments.

Cell proliferation assay

Cells were plated 1 × 105 cells per six-well plate in triplicate for each cell line. Cell viability was determined by the MTT (3-[4,5-dimethylthiazole-2-yl]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) assay.

Transwell migration assay

Transwell cell migration assays were performed by using modified Boyden chambers (Transwell; Corning, Corning, NY). In brief, cells were trypsinized, washed, and suspended in serum-free medium at 106 cells/ml. 100 µl of cells was placed into the upper chambers and allowed to migrate for various time points toward the bottom well with 10% FBS. Cells that migrated to the underside of the chamber were fixed with 3.7% paraformaldehyde, stained with 0.5% crystal violent, and the membranes were dissolved with 33% acetic acid. Cells were photographed and hand-counted by light microscopy, as well as optically densitized at 595nm by an ELISA plate reader.

Statistical analysis

All experiments were done in triplicate. Statistical significance was set a priori at P≤0.05. Analyses were performed with Microsoft Excel and SAS E-guide statistical packages (SAS, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

AJAP1 is deleted in glioblastoma

We used different methods to perform genome-wide screens in glioblastoma samples for genetic alterations. We initially used digital karyotyping, which can be reliably used to identify chromosomal changes, amplifications, deletions, and the presence of foreign DNA sequences (Parrett and Yan, 2005; Wang et al., 2002). We evaluated 27 glioblastoma libraries with an average of 175,000 genomic tags/library, permitting analyses of loci distributed at an average distance of 30 kb throughout the genome. We also performed a genome-wide search for alterations in 78 different glioblastoma primary tumors using the Illumina HumanHap 550 Quad and 610 Duo BeadChip microarrays.

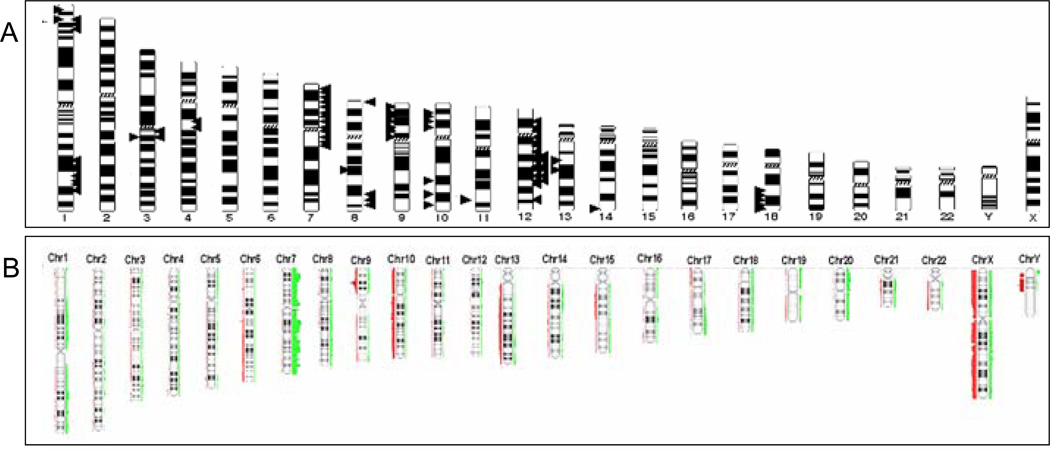

Maps of digital karyotyping libraries and Illumina microarrays all revealed widespread subchromosomal changes in glioblastoma (Fig. 1A–B). Losses were more frequent than gains. High-resolution mapping revealed numerous known and unknown genetic alterations in glioblastoma tumors. For example, amplification of EGFR on chromosome 7, loss of CDKN2A on chromosome 9, and chromosome 10q loss of heterozygosity were clearly demonstrated in our digital karyotyping libraries (Supplementary Data Fig. S1), and Illumina data (Fig. 1B). These findings serve as important internal positive controls.

Figure 1.

Genome-wide screens reveal widespread gains and losses in glioblastoma. Glioblastoma karyotype showing summary of genetic changes found in 27 digital karyotyping libraries A and 78 Illumina HumanHap 550 Quad and 610 Duo microarray libraries B. A total of 105 glioblastoma tumors were analyzed. Bars/arrows on left indicate genomic gains and those on right indicate genomic losses.

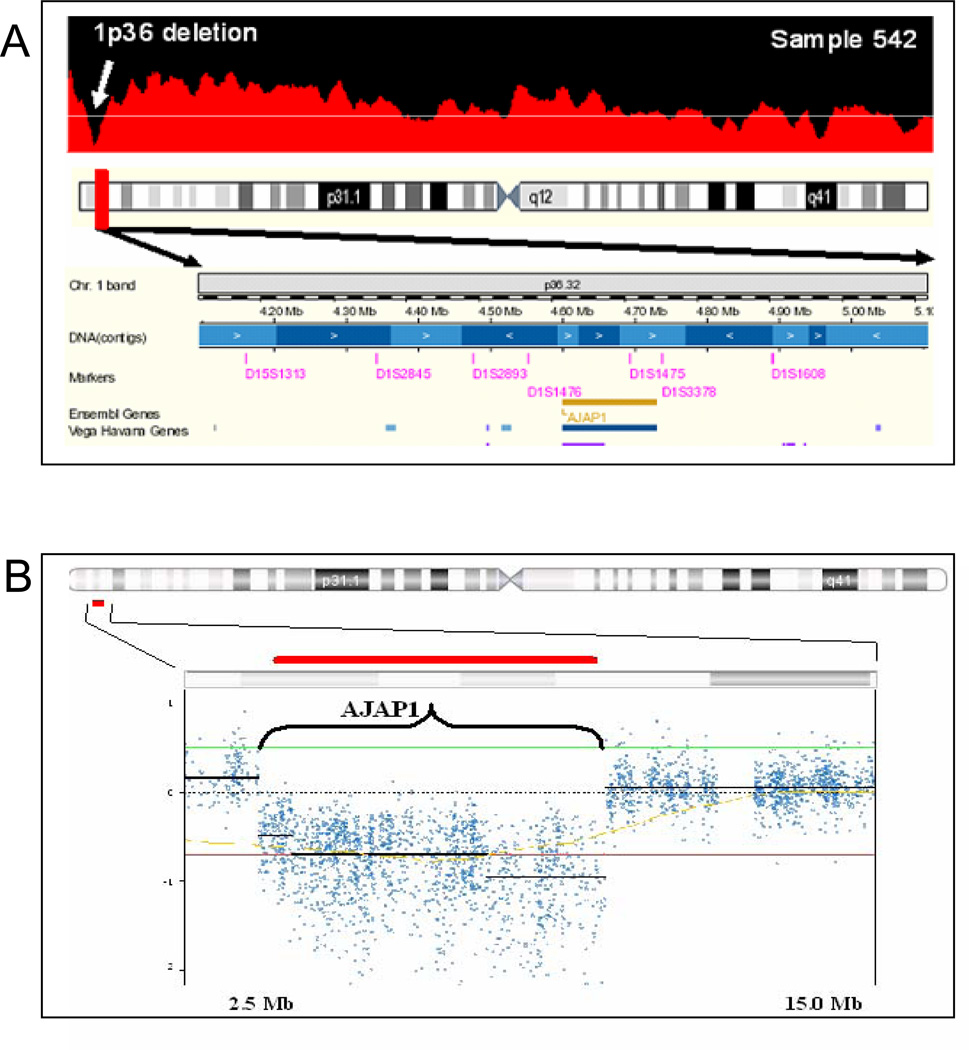

One genetic loss is located at chromosome 1:3,812,102–5,418,455 on the distal arm of chromosome 1p36 in 4 of our 27 digital karyotyping libraries (15%) (Fig. 2A). Examination of the known public human genome database identified one known gene in this segment, AJAP1 (Fig. 2A). These AJAP1 genomic losses consisted of 3 homozygous and 1 loss of heterozygosity deletions. Using Illumina HumanHap BeadChip single nucleotide polymorphism microarrays, we examined 78 glioblastoma samples and discovered 3 LOH deletions of AJAP1 the total sample (4%) of tumors (Fig. 2B). To validate these findings, we performed Q-PCR on our original set of 80 primary glioblastoma tumors and found gene deletion in 15% (7/12 LOH and 5/12 homozygous deletions; Supplementary Data Table T1). In summary, our analysis of this hotspot for genetic alterations on chromosome 1p36 in 105 samples using independent sets of genomic data reveals the unique deletion of AJAP1 in up to 16% of glioblastoma tumors.

Figure 2.

High-resolution mapping of genome-wide screening methods consistently reveals genomic loss of AJAP1 in primary glioblastoma. A, representative high-resolution digital karyotyping map identified homozygous genetic loss located at 1:3,812,102–5,418,455 on chromosome 1p in 3 samples (homozygous deletion shown) and loss of heterozygosity deletion in one sample. B,, representative high resolution Illumina HumanHap BeadChip map confirmed loss of AJAP1 in glioblastoma (homozygous loss shown, red bar is location of AJAP1). Nexus places horizontal black bar at the median single nucleotide polymorphism loss. As the median changes across the area of interest, the line breaks. This break in the horizontal line does not represent single nucleotide polymorphisms in adjacent genes. Red bar demonstrates the AJAP1 gene location. Examination of a public human genome database (http://genome.ucsc.edu) identified one known gene that was consistently deleted on this segment of the distal arm of chromosome 1p, full-length AJAP1 (bottom panel). Y-axis is log value of single nucleotide polymorphism copies per haploid genome; x-axis represents position along chromosome 1 in Mb.

AJAP1 expression is downregulated in glioblastoma tumors and cell lines

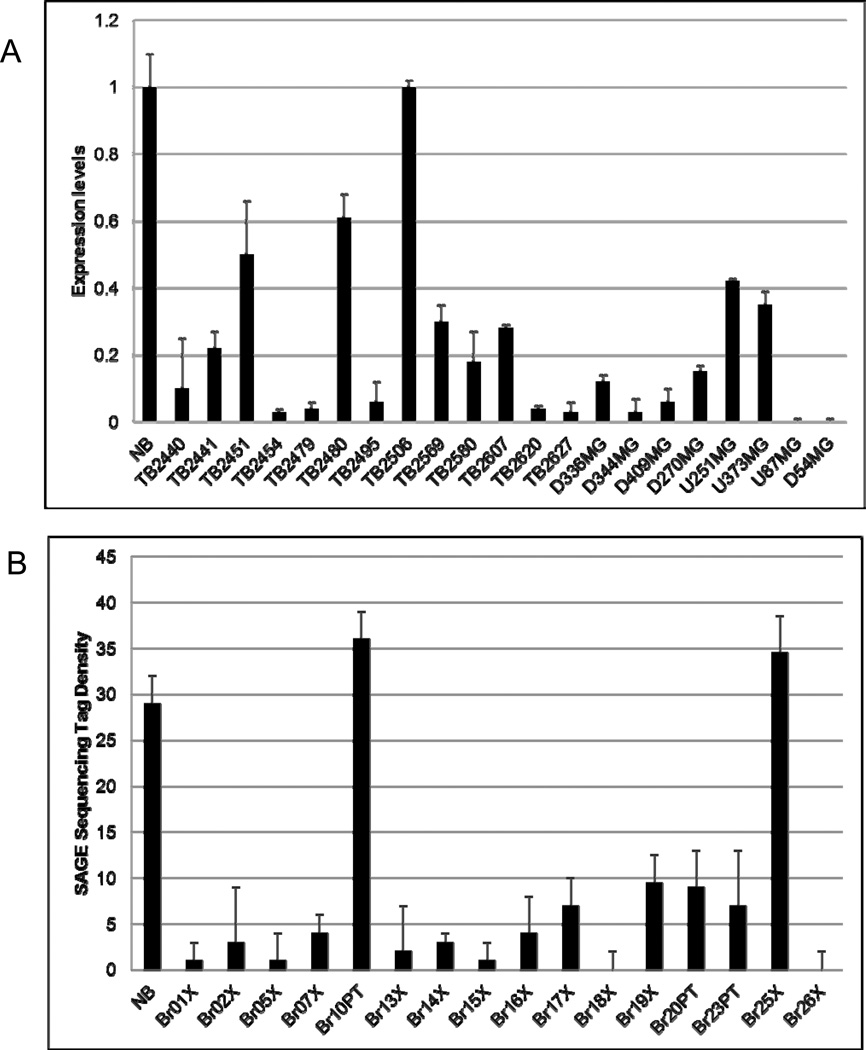

We initially examined AJAP1 expression in 13 primary glioblastoma samples, 8 glioma cell lines and 4 normal brain samples by using Q-PCR. We found that AJAP1 expression was markedly reduced or absent in 92% (12/13) primary glioblastomas (Fig. 3A, TB samples) and all glioblastoma cell lines tested (Fig. 3A, D and U samples). We expanded this study to our entire original set of 80 primary tumors and found reduced or absent expression in 86% (Supplementary Data Table T1). We also performed a search of a public cancer genome SAGE database (http://cgap.nci.nih.gov/SAGE) and confirmed that AJAP1 expression is significantly reduced in glioblastoma, with an average of three AJAP1 SAGE tags in glioblastoma compared with 12 tags in normal human brain. Finally, we explored the sequence tag density for AJAP1 in another SAGE database previously published [see Supplementary Table S8 in (Parsons et al., 2008)]. In this database of 16 glioblastoma tumors, 14 tumors (88%) had sequence tag densities markedly reduced when compared to a normal sample (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

AJAP1 gene expression is frequently reduced or absent in glioblastoma primary tumors and glioma cell lines. A, 12 GBM tumors (TB samples) and 8 glioma cells (D and U samples) tested show reduced AJAP1 expression compared to normal brain (NB) by Q-PCR. One primary tumor (TB2506) had levels similar to normal brain (NB). B, 14 glioblastoma tumors out of 16 (88%) had sequence tag densities markedly reduced when compared to a NB sample [Adapted from Supplementary Table S8 in reference (Parsons et al., 2008)].

Furthermore, we explored the REMBRANDT public database and found intermediate or low AJAP1 expression in all 196 glioblastoma samples when compared to normal tissue, consistent with the 86–92% of our primary glioblastoma tumors with reduced or absent expression. When compared to all gliomas (Supplemental Data Fig. S3, blue line) in the database, those with down-regulation of AJAP1 expression (green line, > 2.0 fold loss, n=206) clearly have a significantly worse survival than those with intermediate expression (yellow line, n=91; p=0.0056).

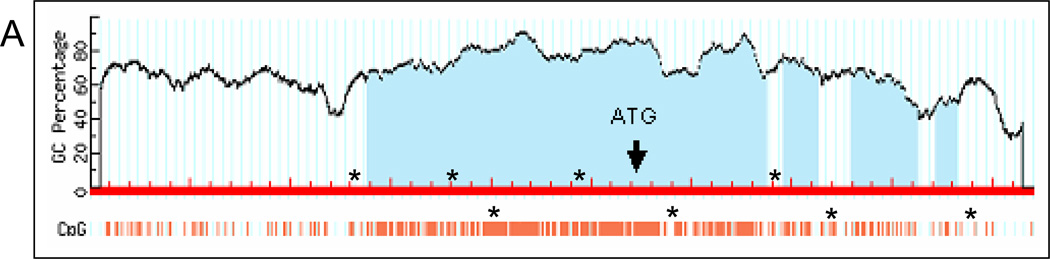

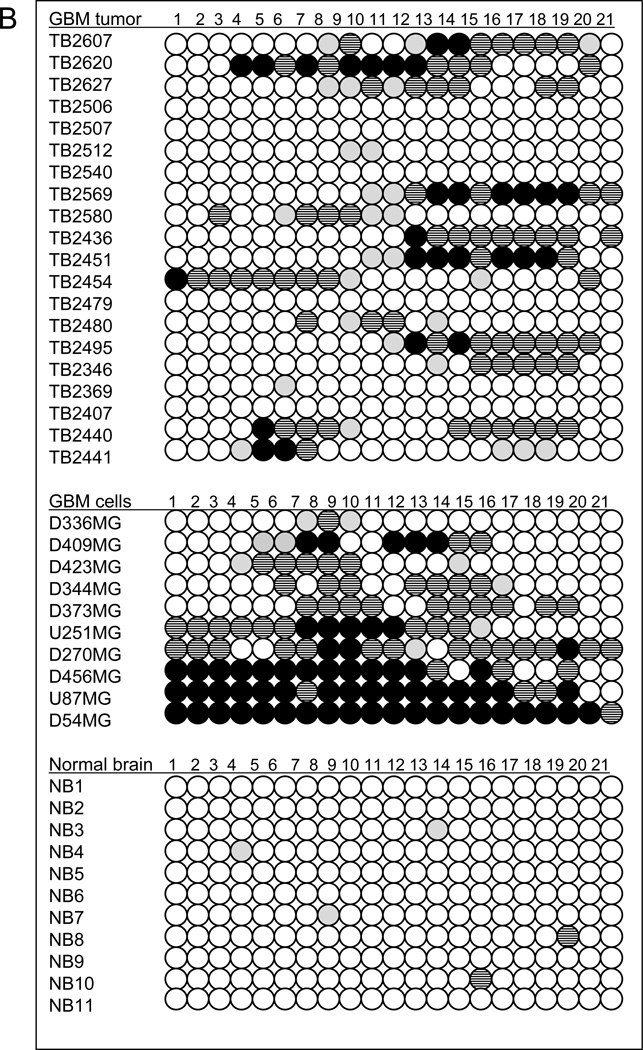

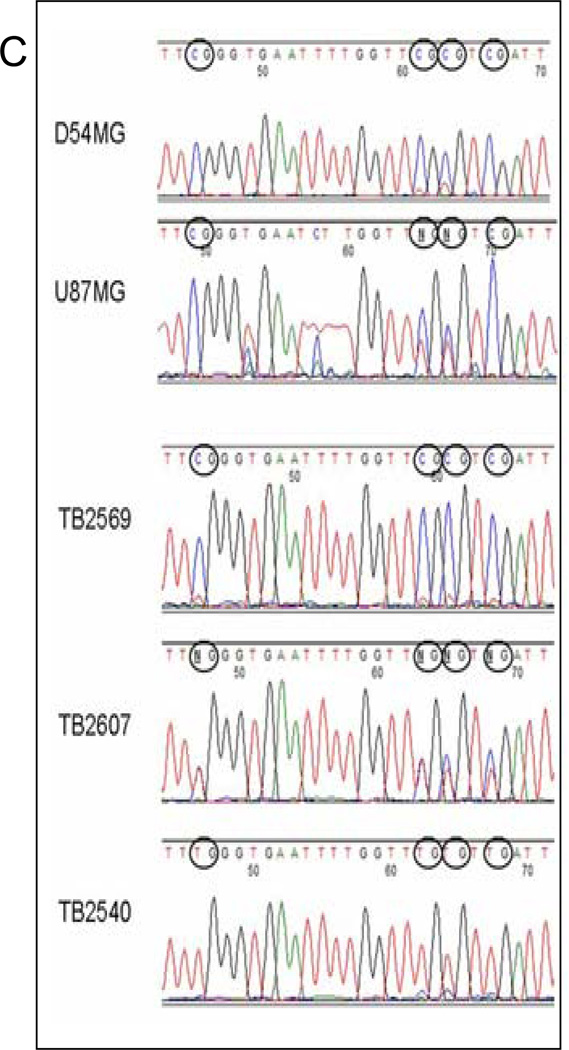

AJAP1 loss of expression is due to promoter methylation

Through our genome-wide screens, we discovered the frequent deletion of AJAP1 in glioblastoma. Expression studies revealed that loss of AJAP1 gene expression appeared to be much more common than gene deletion. Expression was reduced or absent in 86% to 92% of primary glioblastoma tumors and all glioma cell lines, whereas the gene was deleted in up to16% of the tumor samples. These results suggest other mechanisms of loss of gene expression. We performed an exon-by-exon analysis of our original 80 glioblastoma tumors and glioma cell lines, and no point mutations were identified in any exons. We hypothesized that promoter methylation may account for AJAP1 gene silencing. An extensive search revealed 21 CpG candidate island hotspots in the genomic sequence of the AJAP1 promoter region that may serve as sites of gene silencing by methylation (Fig. 4A). Using quantitative methylation-sensitive PCR on bisulfite treated samples, we found that the AJAP1 promoter was often methylated in glioblastoma primary tumors and glioma cell lines (Fig. 4B–C). We initially observed significant AJAP1 promoter methylation in 13 of 20 primary glioblastoma (65%) and 9 of 10 cell lines (90%) (Fig. 4B). Normal brain samples were found to be unmethylated (Fig. 4B). Glioblastoma cell lines U87MG and D54MG demonstrated the lowest levels of gene expression (Fig. 3A) and the highest number of CpG islands to be methylated (Fig. 4B). We then examined our entire set of 80 primary tumors and found significant methylation (i.e. >10% of CpG islands tested) in 63% (Supplementary Data Table T1). We found a clear correlation of loss of expression and the presence of methylation (Supplemental Figure S4, Spearman’s rank correlation, R = −0.7, P<0.005) of AJAP1. 100% of tumors with normal expression, 50% with intermediate expression, and 26% with low/absent expression had no methylation.

Figure 4.

Bisulfite treatment followed by methylation-sensitive quantitative PCR demonstrates extensive promoter methylation in AJAP1. A, schematic structure of the AJAP1 gene and location of candidate CpG islands within promoter region. *above red line = site of 5’ primers, *below red line = site of 3’ primers. B, summary of methylation-sensitive quantitative PCR analysis of 21 CpG sites in 20 primary glioblastoma tumors, 10 glioma cell lines and 11 normal brain samples. (Black circle >25% methylation; striped black circle = 10–25% methylation; gray circle <10% methylation; white circle = no methylation). C, representative sequencing chromatograms demonstrating CpG island methylation after bisulfite treatment in cell lines D54MG and U87MG, as well as tumors TB2569 and TB2607, and lack of methylation in TB2540.

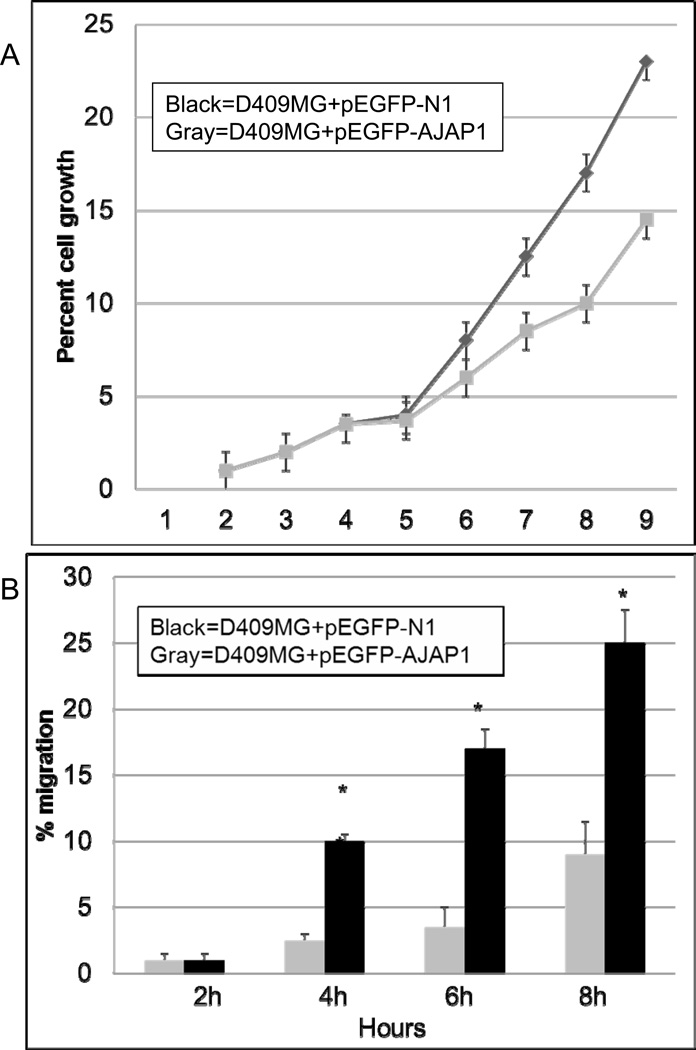

Loss of AJAP1 expression is associated with increased glioma cell proliferation and migration

Prior studies suggest a potential role for AJAP1 in cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions that could be involved in cell motility, migration, and invasion (Bharti et al., 2004; Jakob et al., 2006; McDonald et al., 2006; Schreiner et al., 2007a). These studies indicated that the effect of AJAP1 on tumor cell migration may depend upon the specific tumor type and its environment. Based on these findings and our evidence of loss of expression in glioblastoma, we hypothesize that AJAP1 may contribute to glioblastoma cell migration. We chose D409MG, a glioblastoma cell line with very low AJAP1 expression (Fig. 3A) and evidence of promoter methylation (Fig. 4B). Overexpression of AJAP1 in D409MG with the pEGFP-AJAP1 expression resulted in a marked decrease in cell proliferation (Fig. 5A) and migration through Transwell migration assays (Fig. 5B) as compared to the same cell type transfected with the empty vector pEGFP-N1 (Fig. 5B). We demonstrate similar findings in another glioma cell line as well (Supplementary Figure S5).

Figure 5.

AJAP1 overexpression in glioma cells reduces cell proliferation and migration. A, overexpression of AJAP1 in D409MG glioma cells stably transfected with pEGFP-AJAP1 (open squares) reduces cell proliferation significantly compared to cells transfected with the empty vector, pEGFP-N1 (black squares). *P<0.05, D409MG+pEGFP-N1 compared to D409MG+pEGFP-AJAP1. B, overexpression of AJAP1 in D409MG glioma cells stably transfected with pEGFP-AJAP1 (hatched bar) reduces cell migration significantly compared to cells transfected with the empty vector, pEGFP-N1 (black bar). Experiments were done in triplicate. *P<0.05, D409MG+pEGFP-N1 at 4h compared to D409MG+pEGFP-AJAP1 at 4h, similar comparison at 6h and 8h.

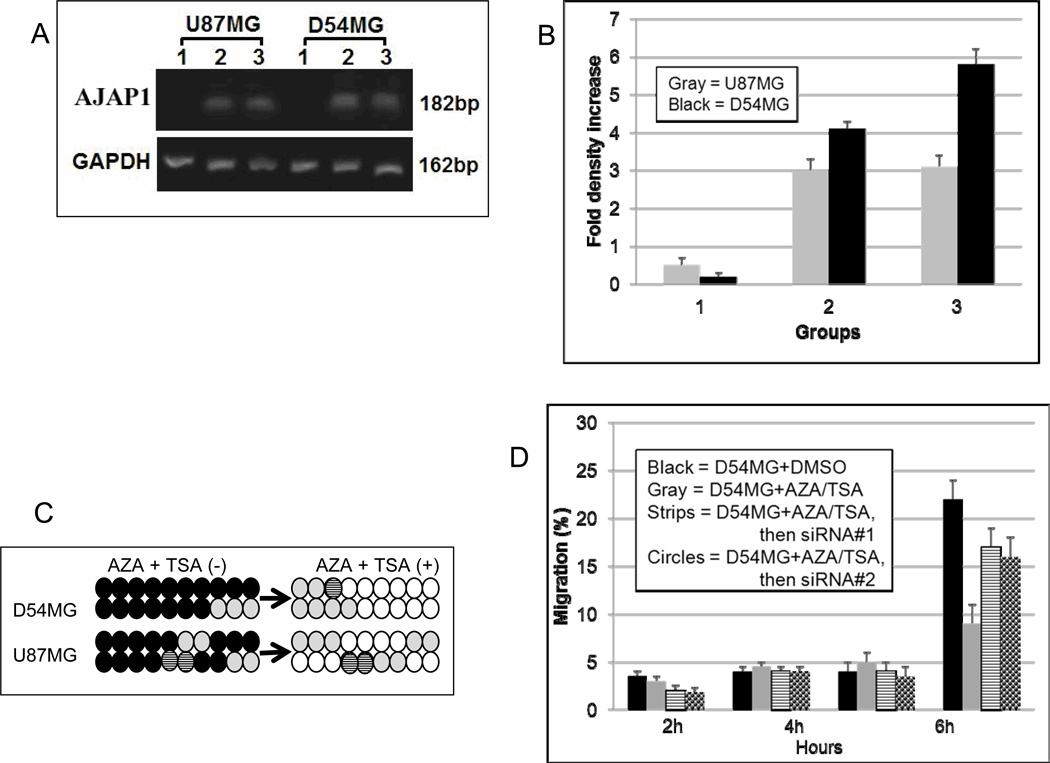

Demethylation restores AJAP1 expression and function

Since AJAP1 can be epigenetically silenced in glioblastoma primary tumors and cell lines, pharmacologic reversal of this epigenetic silencing may be a viable option for restoring normal expression and function. To test this hypothesis, we selected the glioblastoma cell lines D54MG and U87MG, which demonstrate very low AJAP1 expression (Fig. 3A) and extensive promoter methylation (Fig. 4B). Both cell lines were exposed to the methyltransferase inhibitor AZA and the histone deacetylase inhibitor TSA. AZA and TSA have been extensively used in preclinical and clinical studies for demethylating genes (Momparler, 2005). In D54MG and U87MG, AJAP1 expression is undetectable without exposure to either agent (Fig. 6A, lanes 1; Supplementary Data Figure S2), but expression is dramatically increased upon exposure to AZA (Fig. 6A, lanes 2; Supplementary Data Figure S2) or TSA (Fig. 6A, lanes 3; Supplementary Data Figure S2). Densitometric quantification of the PCR products show that AJAP1 expression in both cells increased more than 50-fold (Fig. 6B). Bisulfite sequencing confirms that these reagents dramatically reduce the number of methylated CpG islands in the AJAP1 promoter (Fig. 6C). In D54MG (similar results with U87MG), restoration of AJAP1 expression by demethylation resulted in a significant decrease in migration after treatment (Fig. 6D, hatched bar). Furthermore, we are able to partially ‘rescue’ this phenotype and increase migration by knocking down the AJAP1 gene with siRNA after demethylation treatment (Fig. 6D, gray and diamond bars). These results confirm that AJAP1 expression is epigenetically silenced in glioma cells, promoter methylation can be reversed pharmacologically, and restoration of AJAP1 expression by demethylation treatment decreases glioma cell migration.

Figure 6.

Demethylation treatment in D54MG and U87MG restores AJAP1 expression. A, relative transcription level of AJAP1 in D54MG and U87MG before (lanes 1) and after treatment with AZA (lanes 2) and TSA (lanes 3), by Q-PCR. B, histogram showing relative levels of AJAP1 gene expression in D54MG and U87MG before (group 1) and after exposure to AZA (group 2) and TSA (group 3), (average of 3 blots). C, bisulfite sequencing of D54MG and U87MG before and after exposure to AZA and TSA. (Black circle >25% methylation; striped black circle = 10–25% methylation; gray circle <10% methylation; white circle = no methylation). D, migration results of D54MG after treatment with AZA and TSA show significant decrease in migration of cells (hatched bar) compared to untreated cells (black bars). SiRNA knockdown after AZA/TSA treatment partially restored migration ability (siRNA#1, gray bar; siRNA#2, diamond bar). Experiments were done in triplicate. *P<0.05.

Discussion

With high-resolution genome-wide mapping, we demonstrated in this study the deletion of AJAP1 in many glioblastoma cell lines and primary tumors (Figs. 1–2). In a total of 105 samples, we discovered that up to16% have AJAP1 deleted; however, a much larger percentage (86–92%) have loss of expression (Fig. 3). Other investigators have seen AJAP1 deletion in glial brain tumors. In oligodendroglioma, McDonald et al. found the specific deletion of AJAP1 in 6 of 177 (3.4%) tumors (McDonald et al., 2006). Dong et al. reported two contiguous minimally deleted regions on chromosome 1p36.31-p36.32 in oligodendroglial tumors, one of which contained AJAP1 as the only gene (Dong et al., 2004). The loss of loci on the distal arm of chromosome 1p is more frequently seen in oligodendroglioma than glioblastoma, where the combined loss of 1p and 19q is frequent and predictive of prolonged survival (Brat et al., 2004). Oligodendrogliomas and glioblastomas have some differences; however, these two glial-derived tumors may have important similarities that can be taken advantage for therapeutic design. The importance of this study on glioblastoma primary tumors and cell lines is that it greatly builds on the prior findings in oligodendrogliomas. We hypothesize that AJAP1 may indeed play a similar role in cell adhesion and migration for both of these brain tumors. White et al. defined a single region within 1p36.3 that was consistently deleted in 25% of neuroblastomas, an extracranial tumor of the sympathetic nervous system commonly seen in children (White et al., 2005). AJAP1 was 1 of 6 predicted genes in this deleted region. CHD5 was recently found to be a strong tumor suppressor gene candidate deleted from 1p36.31 in neuroblastomas and inactivation of the second allele was speculated to occur by an epigenetic mechanism (Fujita et al., 2008). This was discovered while mapping the smallest region of a consistently deleted segment at 1p36.31 that contained 23 genes, including AJAP1 (Fujita et al., 2008). Milde et al recently showed the loss of AJAP1 in a progressively metastasizing ependymoma (Milde et al., 2009).

In polarized epithelial cells, AJAP1 is a transmembrane protein that interacts with E-cadherin-β-catenin complexes (Bharti et al., 2004), the adaptor protein complex AP-1B (Jakob et al., 2006), and CD147 (Schreiner et al., 2007b). These recent findings suggest a potential role for AJAP1 in cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions that could be involved in cell motility, migration, and invasion. Little is known about the interactions of AJAP1 except in the context of epithelial cells. Modulation of the cadherin/catenin system may be facilitated by AJAP1 in glioblastoma; however, whether and how this system interacts with AJAP1 is unknown.

Paradoxically, the loss of AJAP1 expression in HeLa cells results in decreased invasiveness (Schreiner et al., 2007b); however, its overexpression in tumor cells also results in decreased invasiveness (McDonald et al., 2006). In their study that included oligodendrogliomas, McDonald et al. found in U251 cells (glioblastoma cell line) that AJAP1 overexpression decreased cell adhesion on extracellular matrix components and decreased migration in wound-healing assays (McDonald et al., 2006). These studies emphasize that AJAP1 may serve very different roles in different scenarios. Based on these findings and our evidence of common loss of expression in glioblastoma, we hypothesized that it may contribute to tumor cell migration in glioblastoma. Consistent with the results of McDonald et al., we also see a significant effect on tumor cell migration in glioblastoma cells. We have reviewed our available clinical data for the tumors tested in this manuscript and do not see a significant difference in AJAP1 deletion, expression, or methylation between primary and secondary glioblastoma.

There is an extensive array of other factors implicated in glioma cell migration where the potential relationship to AJAP1 expression is unexplored (Lefranc et al., 2005; Rich et al., 2005). During invasive migration, cancer cells use secreted, surface-localized and intracellular matrix metalloproteinases, serine proteases, and cathepsins to proteolytically clear and remove different types of extracellular matrix substrates at their interface, including collagens, laminins, vitronectin, and fibronection. Some of these processes may be relevant to glioma cell migration as well. The role of these processes in glioblastoma migration and interaction with AJAP1 remains for further investigation.

Epigenetic silencing via cytosine methylation is a well-established and extensively used mechanism for gene regulation in numerous cancers, including glioblastoma. Genome-wide screens of glioma cells treated with AZA and TSA reveal >160 genes up-regulated by these treatments (Kim et al., 2006). Using mutational and methylation analyses, we showed that AJAP1 expression is not due to mutation, but is epigenetically silenced with promoter methylation in many cases. In our large series of primary tumors and cell lines, we see widespread evidence of AJAP1 methylation (Fig 4B). Furthermore, this mechanism of gene silencing is effectively reversed with the common demethylating agents AZA and TSA (Fig. 6). Restoration of AJAP1 expression by these pharmacologic agents returned its function by reducing tumor cell migration (Fig. 6D). We show that demethylation agents can target AJAP1 (Fig. 6D); however, since we are able to only partially recover migration by knocking down AJAP1 after demethylation treatment, we hypothesize that AZA/TSA treatment likely alters expression of other unknown genes that effect migration. Importantly, not all samples with low or no expression of AJAP1 demonstrate evidence of promoter methylation. Clearly, our data supports the observation that other mechanisms other than DNA methylation and gene mutation also play a role in AJAP1 expression. Targeting methylated genes in glioblastoma may be a viable option since demethylating agents have shown efficacy in preclinical and clinical trials (Momparler, 2005; Momparler et al., 1997).

Though all the methylated glioblastoma tumors showed reduced or silenced expression of AJAP1, one primary tumor (TB2479) and one cell line (D336MG) exhibited reduced AJAP1 expression in the absence of methylation in the analyzed region. It is likely that transcriptional activation of AJAP1 may also be influenced by other mechanisms, such as accessibility of AJAP1 regulator proteins or specific transcription factors.

In this study, we report that AJAP1 is deleted and epigenetically silenced in some glioblastomas. Pharmacologic demethylation treatments return expression and restore function by decreasing tumor cell migration. There is an extensive literature on factors involved in glioblastoma migration where the relationship to AJAP1 is unexplored. This represents an exciting therapeutic target in the treatment of glioblastoma. Effective targeting of migrating glioblastoma cells through chemotherapies or radio-conjugates could greatly impact survival in this deadly brain tumor and potentially eliminate the morbidities of surgical resections. Studies have already shown that glioma invasion can be the target of directed therapies and that these approaches may augment the efficacy of traditional therapies (Giese et al., 2003).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Janet Parsons for editorial support.

Grant support: This project is supported by NIH Grants K12 CA100639-02, American Brain Tumor Association, Neurosurgery Research Education Foundation, National Cancer Center (DCA); NINDS 5P50 NS20023, Merit Award R37 CA011898 (DDB); SPORE 5PO CA108786 (DCA, DDB), and 1R21-NS-048549-01 (SGG).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- Comprehensive genomic characterization defines human glioblastoma genes and core pathways. Nature. 2008;455:1061–1068. doi: 10.1038/nature07385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharti S, Handrow-Metzmacher H, Zickenheiner S, Zeitvogel A, Baumann R, Starzinski-Powitz A. Novel membrane protein shrew-1 targets to cadherin-mediated junctions in polarized epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:397–406. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-05-0281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brat DJ, Seiferheld WF, Perry A, Hammond EH, Murray KJ, Schulsinger AR, et al. Analysis of 1p, 19q, 9p, and 10q as prognostic markers for high-grade astrocytomas using fluorescence in situ hybridization on tissue microarrays from Radiation Therapy Oncology Group trials. Neuro Oncol. 2004;6:96–103. doi: 10.1215/S1152851703000231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CBTRUS. Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States. Chicago: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z, Pang JS, Ng MH, Poon WS, Zhou L, Ng HK. Identification of two contiguous minimally deleted regions on chromosome 1p36.31-p36.32 in oligodendroglial tumours. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:1105–1111. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiegler H, Carr P, Douglas EJ, Burford DC, Hunt S, Scott CE, et al. DNA microarrays for comparative genomic hybridization based on DOP-PCR amplification of BAC and PAC clones. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2003;36:361–374. doi: 10.1002/gcc.10155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita T, Igarashi J, Okawa ER, Gotoh T, Manne J, Kolla V, et al. CHD5, a tumor suppressor gene deleted from 1p36.31 in neuroblastomas. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:940–949. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giese A, Bjerkvig R, Berens ME, Westphal M. Cost of migration: invasion of malignant gliomas and implications for treatment. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1624–1636. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.05.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegi MEDAC, Gorlia T, et al. MGMT gene silencing and benefit from temozolomide in glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:997–1003. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakob V, Schreiner A, Tikkanen R, Starzinski-Powitz A. Targeting of transmembrane protein shrew-1 to adherens junctions is controlled by cytoplasmic sorting motifs. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:3397–3408. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanu O, Hughes B, Di C, Lin N, Fu J, Bigner DD, Yan H, Adamson DC. Glioblastoma multiforme oncogenomics and signaling pathways. Clin Med: Oncol. 2009;3:39–52. doi: 10.4137/cmo.s1008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TY, Zhong S, Fields CR, Kim JH, Robertson KD. Epigenomic profiling reveals novel and frequent targets of aberrant DNA methylation-mediated silencing in malignant glioma. Cancer Res. 2006;66:7490–7501. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefranc F, Brotchi J, Kiss R. Possible future issues in the treatment of glioblastomas: special emphasis on cell migration and the resistance of migrating glioblastoma cells to apoptosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2411–2422. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeb LA. Mutator phenotype may be required for multistage carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 1991;51:3075–3079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez R, Schackert G, Esteller M. Hypermethylation of the proapoptotic gene TMS1/ASC: prognostic importance in glioblastoma multiforme. J Neurooncol. 2007a;82:133–139. doi: 10.1007/s11060-006-9264-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez R, Setien F, Voelter C, Casado S, Quesada MP, Schackert G, et al. CpG island promoter hypermethylation of the pro-apoptotic gene caspase-8 is a common hallmark of relapsed glioblastoma multiforme. Carcinogenesis. 2007b doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald JM, Dunlap S, Cogdell D, Dunmire V, Wei Q, Starzinski-Powitz A, et al. The SHREW1 gene, frequently deleted in oligodendrogliomas, functions to inhibit cell adhesion and migration. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:300–304. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.3.2391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milde T, Pfister S, Korshunov A, Deubzer HE, Oehme I, Ernst A, et al. Stepwise accumulation of distinct genomic aberrations in a patient with progressively metastasizing ependymoma. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2009;48:229–238. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momparler RL. Preclinical and clinical studies on 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine, a potent inhibitor of DNA methylation, in cancer therapy. In: Szyf M, editor. DNA methylation and cancer therapy. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Momparler RL, Bouffard DY, Momparler LF, Dionne J, Belanger K, Ayoub J. Pilot phase I-II study on 5-aza-2'-deoxycytidine Decitabine in patients with metastatic lung cancer. Anticancer Drugs. 1997;8:358–368. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199704000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller W, Nutt CL, Ehrich M, Riemenschneider MJ, von Deimling A, van den Boom D, et al. Downregulation of RUNX3 and TES by hypermethylation in glioblastoma. Oncogene. 2007;26:583–593. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohgaki H, Kleihues P. Genetic pathways to primary and secondary glioblastoma. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:1445–1453. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olshen AB, Venkatraman ES, Lucito R, Wigler M. Circular binary segmentation for the analysis of array-based DNA copy number data. Biostatistics. 2004;5:557–572. doi: 10.1093/biostatistics/kxh008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parrett TJ, Yan H. Digital karyotyping technology: exploring the cancer genome. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2005;5:917–925. doi: 10.1586/14737159.5.6.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons DW, Jones S, Zhang X, Lin JC, Leary RJ, Angenendt P, et al. An integrated genomic analysis of human glioblastoma multiforme. Science. 2008;321:1807–1812. doi: 10.1126/science.1164382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich JN, Hans C, Jones B, Iversen ES, McLendon RE, Rasheed BK, et al. Gene expression profiling and genetic markers in glioblastoma survival. Cancer Res. 2005;65:4051–4058. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner A, Ruonala M, Jakob V, Suthaus J, Boles E, Wouters F, et al. Junction protein shrew-1 influences cell invasion and interacts with invasion-promoting protein CD147. Mol Biol Cell. 2007a;18:1272–1281. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-07-0637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner A, Ruonala M, Jakob V, Suthaus J, Boles E, Wouters F, et al. Junction Protein Shrew-1 Influences Cell Invasion and Interacts with Invasion-promoting Protein CD147. Mol Biol Cell. 2007b doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-07-0637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone AR, Bobo W, Brat DJ, Devi NS, Van Meir EG, Vertino PM. Aberrant methylation and down-regulation of TMS1/ASC in human glioblastoma. Am J Pathol. 2004;165:1151–1161. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63376-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stupp R, Mason WP, van den Bent MJ, Weller M, Fisher B, Taphoorn MJ, et al. Radiotherapy plus concomitant and adjuvant temozolomide for glioblastoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:987–996. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang TL, Maierhofer C, Speicher MR, Lengauer C, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW, et al. Digital karyotyping. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16156–16161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202610899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White PS, Thompson PM, Gotoh T, Okawa ER, Igarashi J, Kok M, et al. Definition and characterization of a region of 1p36.3 consistently deleted in neuroblastoma. Oncogene. 2005;24:2684–2694. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.