Abstract

Sibling relationships are an important context for development, but are often ignored in research and preventive interventions with youth and families. In childhood and adolescence siblings spend considerable time together, and siblings’ characteristics and sibling dynamics substantially influence developmental trajectories and outcomes. This paper reviews research on sibling relationships in childhood and adolescence, focusing on sibling dynamics as part of the family system and sibling influences on adjustment problems, including internalizing and externalizing behaviors and substance use. We present a theoretical model that describes three key pathways of sibling influence: one that extends through siblings’ experiences with peers and school, and two that operate largely through family relationships. We then describe the few existing preventive interventions that target sibling relationships and discuss the potential utility of integrating siblings into child and family programs.

Keywords: siblings, prevention, mental health, substance use

From the origins of psychological research and intervention focusing on children and adolescents, scholars and clinicians have viewed the parent-child relationship as a key influence on development and mental health. Over the past 30 years, researchers have made considerable progress in understanding the impact of the inter-parental relationship—including couple and coparental conflict—on youth adjustment. In contrast, far fewer efforts have been made to illuminate a third, but equally significant family relationship: the relationship between siblings.

The daily companionship of siblings in childhood and the lifelong nature of sibling bonds, combined with the intense positive and negative emotional nature of sibling exchanges, yield a family relationship whose power and importance has frequently been underestimated by developmental and family scholars. A growing body of work is now documenting the developmental significance of sibling relationships across the lifespan. The vast majority of U.S. children grow up in households with at least one sibling (Hernandez, 1997). Indeed, children in the U.S. today are more likely to grow up in a household with a sibling than with a father (McHale, Kim, & Whiteman, 2006). In addition, time use research shows that European American children spend more of their free time with siblings than with anyone else (e.g.,McHale & Crouter, 1996), and among minority groups where familism values are pronounced, siblings play an even more important role as companions (Updegraff, McHale, Whiteman, Thayer, & Delgado, 2005).

In early childhood, close, everyday contact coupled with emotional intensity foster the development of social understanding (e.g., Dunn, 1998), and social support from siblings plays a role in adjustment beginning in childhood. For instance, sibling warmth and support is linked to peer acceptance and social competence (e.g., Bank, Burraston, & Snyder, 2004; Stormshak, Bellanti, & Bierman, 1996), academic engagement and educational attainment (Melby, Conger, Fang, Wickrama, & Conger, 2008), and intimate relationships in adolescence and young adulthood (Bank, Patterson, & Reid, 1996; Noland, Liller, McDermott, Coulter, & Seraphine, 2004; Updegraff, McHale, & Crouter, 2000). Although the amount of sibling contact diminishes as children age and move out of their parents’ homes, sibling relationships continue to influence adult well-being. Indeed, the quality of sibling relationships is one of the most important longterm predictors of mental health in old age (Waldinger, Vaillant, & Orav, 2007). It is for good reason that the terms “sisterhood” and “brotherhood” are used to connote cohesion and support, even among biologically unrelated individuals.

A basic understanding of the power of sibling relationships in shaping life course development was demonstrated in the founding document of the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim religions—the book of Genesis. The rivalry of the first siblings, Cain and Abel, led to fratricide and exile. Abraham banished Isaac’s half-brother, Ishmael, and his mother to the wilderness. Jacob and Esau clashed over parental favoritism and inheritance, leading to parent-child coalitions (Isaac and Esau vs. Jacob and Rebecca) and Jacob’s flight from potential fratricide. The jealousy of Joseph’s brothers led to their selling him into slavery and presentation of a faked death to their father. These dramatic and central stories of sibling rivalry and conflict include themes researchers are exploring today: dastardly deeds, conflict over parental love and resources, and triangulation of children into parental conflicts. Yet these founding stories of the Western psyche also suggest that sibling conflicts can lead individuals to pursue independent and successful paths in the world (e.g., Jacob; Joseph) --and sometimes reconciliation (e.g., Ishmael and Isaac burying Abraham together; Joseph eventually embracing his brothers in Egypt).

Despite the ancient truths about the destructive and constructive powers of sibling bonds and the more recent scholarly charting of this territory, prevention and intervention program development has generally ignored sibling relationships. However, sibling relationships—like the third rail on a subway track that carries the electrical current—are powerful and intense, driving development forward, but presenting dangers as well. Our thesis is that a focus on sibling relationships should play a larger role in efforts to prevent mental health problems and promote health behaviors.

We begin with an overview of the key features of sibling relationships, highlight the larger family contexts of sibling relationships, and describe what is known about the influence of siblings and sibling relationships on youth well-being. We focus primarily on siblings’ role in mental health and behavior problems—although we do touch on the important positive role that sibling relationships play in the development of social competence and positive well-being. We discuss sibling influences on internalizing and externalizing problems, highlighting work on substance use due to the large body of research that has documented sibling influence in this latter area of problem behavior. We then present a conceptual model that illustrates the processes thorough which sibling relationships impact youth well-being. Finally, we describe the few preventive interventions that incorporate sibling relationships as a key focus, and conclude with recommendations for future research.

Features of Sibling Relationships

In considering sibling relationships in light of preventive interventions for protection from and reduction of risks, one must take into account the complexity of these relationships. This complexity can be understood in terms of the similarities to, and differences from, children’s other important relationships, namely peer and parent-child relationships. Unlike friendships, sibling relationships are non-elective, they usually imply a life-long bond, and the sibling role structure encompasses both egalitarian and complementary elements. Birth order and age differences between siblings may create a hierarchical dynamic in that older siblings are more likely to serve as models, sources of advice, and caregivers for their younger siblings than vice versa (Slomkowski, Rende, Conger, Simons, & Conger, 2001; Tucker, McHale, & Crouter, 2001). Birth order may be even more important in cultures where roles of older and younger sisters and brothers are proscribed (e.g., Nuckolls, 1993).

Sibling relationships are defined by a range of structural features, e.g., gender constellation, age spacing, and biological relatedness as well as the dyad’s place in the overall family constellation of siblings. A number of studies have documented gender differences in relationship quality. In general, they find that sister-sister pairs tend to be the most intimate, and that dyads that include a brother may be more conflictual (Cole & Kerns, 2001; Furman & Buhrmester, 1992; Kim, McHale, Osgood, & Crouter, 2006). As we describe below, some findings suggest that gender also may impact sibling influences processes like modeling. It is important to note, however, that even though gender differences exist, most research suggests that it is not structural features per se, but relationship dynamics that explain sibling relationship quality outcomes (Furman & Lanthier, 2002).

There is considerable untapped potential for supporting children and families through focusing on sibling dynamics. Sibling relationships are one of the most significant child-rearing challenges parents face (e.g., Perlman & Ross, 1997). Indeed, our research suggests that the most frequent source of disagreements and arguments between parents and young adolescents is how siblings are getting along (McHale & Crouter, 1996). Observational research has documented the occurrence of sibling conflict at a rate of up to 8 times per hour (Berndt & Bulleit, 1985; Dunn & Munn, 1986), and sibling aggression is common: 70% of families report physical violence between siblings, and over 40% of children were kicked, bitten, or punched by their siblings during a one year period (Steinmetz, Straus, & Gelles, 1981). In fact, sibling violence occurs more frequently than other forms of child abuse, and is significantly related to substance use, delinquency, and aggression—even controlling for other forms of family violence (Button & Gealt, 2009).

However, the intensity of sibling ties also holds positive benefits for children. As mentioned above, beginning in early childhood, sibling interactions provide an arena for developing and practicing relationship skills (e.g., Dunn, 1998). Close, supportive sibling relationships may promote the qualities and skills needed for successful friend and romantic relationships (e.g., Bank, Burraston et al., 2004; Updegraff, McHale, & Crouter, 2002). The large amount of time siblings spend together, along with their family identity and shared experiences, often yield lifelong bonds.

Sibling bonds and the family system

As sibling relationships develop within a larger family system (Minuchin, 1985), there are transactional relations between sibling dynamics and both other family members’ well-being and other family subsystem relationships. Parenting and parent-child relationships impact sibling relationship quality, with harsh and authoritarian parenting linked to more conflictual sibling exchanges (e.g., McHale, Updegraff, Tucker, & Crouter, 2000). On the other hand, parents can have a positive impact on siblings relationships, for example by scaffolding conflict resolution strategies (reasoning, perspective-taking)—the use of which is related to more harmonious sibling relationships (Perlman & Ross, 1997; Siddiqui & Ross, 2004).

A family effects model posits that conflictual and coercive sibling interaction patterns represent a substantial stressor for parents (McHale & Crouter, 1996) and can diminish parents’ psychological well-being. Such ongoing stress can disrupt competent, engaged parenting—which may lead alternately to harsh, authoritarian discipline and parental disengagement (Dishion, Nelson, & Bullock, 2004; Patterson, Dishion, & Bank, 1984). Prior research links sibling conflict and parental negativity to low levels of parental involvement and monitoring (Furman & Giberson, 1995; Stocker & McHale, 1992; Stocker & Youngblade, 1999), with longitudinal analysis allowing for stronger inferences about direction of effect (Brody, Kim, Murry, & Brown, 2003).

Although less studied, the tenor of sibling interactions also appear to influence the family system, with impacts on both parent-child and inter-parental relationships (Dunn, Deater-Deckard, Pickering, & Golding, 1999; MacKinnon, 1989; Reese-Weber & Kahn, 2005).

A key family dynamic that influences sibling relationships is parental differential treatment (PDT). Social comparison theory (Festinger, 1954) suggests that people evaluate themselves based on comparisons with others, particularly those who are physically proximate and similar to themselves. Siblings represent prime candidates for social comparison and are often directly compared to one another by others (e.g., parents). Although Western social norms call for equal treatment of offspring, most parents recognize differences between their children in behavior, personality, and needs and often cite children’s personal characteristics as motivation for treating their offspring differently (McHale & Crouter, 2003; Volling, 1997). Children are sensitive to PDT and report that it occurs frequently. PDT is linked to less positive sibling relationships from early childhood through adolescence (Brody, Stoneman, & Burke, 1987; Stocker, Dunn, & Plomin, 1989) and the disfavored sibling tends to show higher levels of depression (Feinberg, Reiss, & Hetherington, 2001; Shanahan, McHale, Crouter, & Osgood, 2008), antisocial and delinquent behavior (Richmond, Stocker, & Rienks, 2005; Tamrouti-Makkink, Dubas, Gerris, & van Aken, 2004), and substance use (Mekos, Hetherington, & Reiss, 1996). These findings emerge in longitudinal studies and even after controlling for parent-child relationship quality. Importantly, the direction of effect cannot be assumed to flow from differential treatment to child adjustment; for instance, one study found that youth externalizing behaviors predicted an increase in mothers’ hostility over time, suggesting that PDT may also arise as a reaction to existing sibling differences (Richmond & Stocker, 2008).

An important line of study reveals the role of context in PDT. For instance, some findings suggest stronger negative effects for girls than for boys and for older than for younger siblings (Feinberg, Neiderhiser, Reiss, Hetherington, & Simmens, 2000; Tamrouti-Makkink et al., 2004). Moreover, siblings’ perception of parents’ reasons for differential treatment (Kowal & Kramer, 1997) and whether they believe the differential treatment to be fair (e.g., they feel that their sibling requires special attention due to a disability or a younger age) may be as or more important for sibling relationship quality than the amount of PDT per se (Kowal, Kramer, Krull, & Crick, 2002; McHale & Pawletko, 1992; McHale, Updegraff, Jackson Newsom, Tucker, & Crouter, 2000). Research on Mexican American families suggests that cultural factors also may be at play: Among adolescents who endorsed the traditional value familismo (which highlights concern for the needs and interests of the family above oneself), disfavored status was less strongly linked with risky behavior and depression (McHale, Updegraff, Shanahan, Crouter, & Killoren, 2005). In some collectivistic cultures, family roles and expectations are more differentiated as function of gender and age, making some forms of PDT a more culturally acceptable dynamic.

Consideration of PDT provides insight into linkages between interparental and sibling relationships within the family system. Evidence suggests that interparental discord is linked to greater levels of PDT (Deal, 1996; Stocker & Youngblade, 1999; Yu & Gamble, 2008), which may be the result of a number of processes, such as increased parental stress leading to scapegoating of one child, or a tendency for children to adopt different family roles, with one becoming most likely to be triangulated into interparental conflict. McHale and colleagues have explored inter-parental patterns of PDT (McHale, Crouter, McGuire, & Updegraff, 1995), suggesting that a single parent’s favoritism toward one child may reflect an inter-generational coalition, whereas congruence between parents’ PDT reflects positive coparenting. This work reveals that inter-parental incongruence covaries longitudinally with declines in marital quality (Kan, McHale, & Crouter, 2008) and more adolescent adjustment problems (Solmeyer, Killoren, McHale, & Updegraff, 2011). Thus both PDT and incongruence in PDT across parents is linked to interparental discord and to adolescent maladjustment.

Siblings and Adjustment

Researchers have established links between the mental and behavioral health characteristics of one sibling and those of the other. For example, Shortt and colleagues reported that older siblings' externalizing behavior was associated with increased externalizing behavior in the younger sibling over time (Shortt, Stoolmiller, Smith-Shine, Eddy, & Sheeber, 2010), and Branje and colleagues reported that one sibling’s behavior problems were associated with the other’s depression (Branje, 2004). In addition, research has consistently found moderately strong positive associations between levels of siblings’ substance use (Brook, Whiteman, Gordon, & Brook, 1990; Conger & Rueter, 1996; Epstein, Bang, & Botvin, 2007; Gau et al., 2007; Pomery et al., 2005; Rende, Slomkowski, Lloyd-Richardson, & Niaura, 2005; Scherrer et al., 2008).

The most popular theory used to explain sibling similarities is social learning theory (Bandura, 1977). From this perspective, individuals learn new behaviors and develop attitudes and beliefs through reinforcement, observation, and subsequent imitation of salient models, particularly those who are powerful, warm, and similar to themselves. In these respects, siblings (particularly older siblings) are salient models for adolescents. By virtue of their high-status position within the family and their roles as providers of support and advice, older siblings are often seen as both powerful and nurturant by their younger siblings. In line with theory, same sex siblings and those with warm relationships were more likely to model one another (East & Khoo, 2005; McHale, Bissell, & Kim, 2009; Rowe & Gulley, 1992; Trim, Leuthe, & Chassin, 2006).

However, it is important to recognize that there are several other pathways that likely account for links between siblings’ mental and behavioral health. For example, biological siblings share genes (an average of 50% of genes of full biological siblings overlap), some of which may influence adjustment and health risk behaviors. In addition, associations between sibling characteristics and behaviors may arise from environmental exposures independent of genetic factors (e.g., Rende, Slomkowski, Stocker, Fulker, & et al., 1992). For example, siblings who live together share experiences of substance use by parents as well as by peers and adults in the community. Siblings also share exposure to other family, school, and community conditions--although behavioral genetic research has highlighted how the same or similar environmental factors may be experienced quite differently by siblings and thus lead to differential effects.

Not surprisingly, sibling relationship qualities have been linked to a range of individual outcomes, including depression, identity and self-esteem, aggression, delinquency, school adjustment and achievement, peer and romantic relationships, and substance use and other health risk behaviors in childhood and adolescence. In fact, in some research, sibling relationship effects are evident even after the effects of parent-child and peer relationships are taken into account (e.g., Kim, McHale, Crouter, & Osgood, 2007; McGue & Sharma, 1995).

In this paper, we are primarily interested in sibling effects (the ways that one youth’s substance use impacts the other) as well as sibling relationship effects (how the quality of the sibling relationship impacts sibling substance use). Although there are also direct impacts of modeling, as noted, these are moderated by the nature of the sibling relationship. For simplicity, we refer to all of these processes with the term ‘sibling effects’.

Internalizing problems

A number of studies have linked sibling relationship difficulties to internalizing problems (e.g., Milevsky & Levitt, 2005). For example, a longitudinal study found that, even controlling for parent-child relationships and sibling and parent adjustment, increases in sibling conflict over time were linked to increases in depressive symptoms (Kim et al., 2007). That same study found that increased sibling intimacy was linked to decreased depressive symptoms among girls. McHale and colleagues used cluster analysis to create groups based on levels of both sibling warmth and conflict, which yielded a tripartite typology: close, distant, and negative (McHale, Kim, Whiteman, & Crouter, 2007). Depression was highest for children in the negative (high conflict low warmth) relationship cluster. The influence of sibling relationships on internalizing symptoms is not limited to short-term effects, as a 30-year prospective study recently indicated (Waldinger et al., 2007).

It is likely that the causal influence between sibling dynamics and adjustment is bidirectional: Not only should low sibling warmth be associated with higher depression, but depressed children should form less supportive sibling ties. Experimental studies would provide the strongest evidence for a causal influence of sibling relations on adjustment and only, a few studies have utilized longitudinal data to illuminate direction of effect. For example, Stocker and colleagues found that sibling conflict at one time point predicted increases in children's anxiety, depressed mood, and delinquent behavior 2 years later, even controlling for maternal negativity and marital conflict (Stocker, Burwell, & Briggs, 2002). However, children's adjustment at Time 1 did not predict sibling conflict at Time 2.

In addition to the main effects of sibling dynamics on mental health and adjustment, supportive, close, and warm sibling relationships may buffer the impact of negative influences on child well-being. For example, positive sibling ties buffer youth from the impact of stressful life events on internalizing problems (Gass, Jenkins, & Dunn, 2007). A handful of studies suggest that close sibling relationships reduce the negative impacts of marital hostility on children’s adjustment (Deković & Buist, 2005; Jenkins & Smith, 1990; O'Connor, Hetherington, & Reiss, 1998). For children who are bullied by peers, sibling warmth is particularly important for positive emotional and behavioral adjustment. And some research suggests that sibling support buffers individuals’ self-esteem, loneliness, and depression in contexts of low levels of parent or peer support (East & Rook, 1992; Milevsky & Levitt, 2005). Thus, positive sibling relationships are not only important influences on adjustment in general, but also serve to moderate the impact of negative parent, peer, and other experiences on youth’s mental health.

There is considerable work to be done to clarify the pathways through which sibling dynamics affect well-being. For example, Howe and colleagues (Howe, Aquan Assee, Bukowski, Lehoux, & Rinaldi, 2001) suggest that, through their experiences in a warm sibling relationship, youth can practice sharing intimate thoughts and learn how to understand others’ feelings and successfully resolve conflicts. The social skills and self-esteem gained through positive sibling interactions then could transfer to other contexts, such as peer and romantic relationships. However, it is unknown which of a number of factors that are crucial for forming positive peer relationships (e.g., emotion regulation, positive internal working models, social skills, fair play behaviors) are promoted by positive sibling dyanmics. Moreover, the total impact of sibling relationships on mental health and adjustment may be partly mediated through the consequences of positive sibling relationships on peer relationships. One longitudinal study provides support for such a pathway (Yeh & Lempers, 2004): Adolescents who reported positive sibling relationships at one time point tended to have better friendships and higher self-esteem at a second time point, which in turn was linked to less loneliness and depression (and substance use and delinquent behaviors) at a third time point.

Externalizing and substance use behaviors

We have focused on internalizing problems up to this point, but sibling effects are important in the area of externalizing behavior problems as well. As noted, siblings provide a primary social context for development, given both the emotional intensity of their relationship and the amount of time they spend together. Sibling reinforcement is particularly important in the development of negative behaviors, such as colluding against parental authority, engaging in delinquent activity, and substance use. As noted, hostility, aggression, and violence between siblings are common and predict antisocial behavior and substance use, in some reports, beyond what is accounted for by parent-child and peer relationships (Bank & Burraston, 2001; Bank, Burraston et al., 2004; Brody, Ge et al., 2003; Bullock, Bank, & Burraston, 2002; Conger & Conger, 1994; Conger, Conger, & Scaramella, 1997; Garcia, Shaw, Winslow, & Yaggi, 2000; Snyder, Bank, & Burraston, 2005; Yeh & Lempers, 2004).

Two perspectives on the development of antisocial behavior and sibling reinforcement patterns are Patterson’s (1982) coercive processes model and theories of sibling deviancy training processes (Bullock & Dishion, 2002; Slomkowski et al., 2001). The central idea behind Patterson’s coercive processes model is that negativity and coercion in the sibling relationship represent a “training ground” for the development of a generalized negative, conflictual, and coercive interpersonal style (Patterson, 1984; Patterson, 1989;). Youth adopt coercive behavior patterns as they learn through social reinforcement that such behavior is a successful means of obtaining a goal. This coercive interpersonal style is associated with poor self control, including decreased ability to tolerate frustration, manage negative emotions, and communicate calmly. Through repetition, children internalize a working model of conflict resolution as based on coercion, and generalize this approach to peers and others outside the family (e.g., Natsuaki, Ge, Reiss, & Neiderhiser, 2009).

Patterson, DeBaryshe, and Ramsey (1989) report that youth who develop this negative interpersonal orientation encounter relational difficulties at school with peers and are perceived negatively by teachers (Lewin, Hops, Davis, & Dishion, 1994; Stormshak, Bellanti, Bierman, & Group, 1996). These youth then affiliate with other youth with similar disruptive and problematic interpersonal and behavioral styles, both as a result of their own friendship choices as well as educational grouping into low achieving and behaviorally disordered classes and programs (Dishion, Patterson, Stoolmiller, & Skinner, 1991; Patterson, DeBaryshe, & Ramsey, 1989). As a result of conflicts with teachers, these youth also tend to develop low levels of school attachment, and their affiliations with similar peers reinforce negative school attitudes and behaviors (e.g. skipping class). Affiliation with antisocial peers represents the proximal context for exposure to and reinforcement of serious antisocial behaviors and substance (Keenan & Shaw, 1995; Wills, 1999).

Thus, it appears that conflict and coercion in the sibling context may put youth at risk for relational difficulties with peers, which lead to problems at school and association with substance-using and/or delinquent peers. Although there has been some interest in the generalization of aggression from the sibling relationship to peer relations, it has generally been unrecognized that the experience of victimization within the sibling relationship may lead to a greater likelihood of victimization among peers as well (Yabko, Hokoda, & Ulloa, 2008). Such generalization of victimization may take place through the learning of submissive expectations and social behaviors.

A second process theory regarding the development of antisocial behavior that has included a focus on siblings is termed deviancy training. Researchers have expanded the notion of peer deviance training—in which youths provide reinforcement for antisocial attitudes and behaviors through shared laughter or other signs of approval—to sibling dynamics. Siblings aid in deviancy training by serving as antisocial models, reinforcing antisocial behaviors and attitudes, and colluding to undermine parental authority (Bank et al., 1996; Bullock & Dishion, 2002; McGue, Sharma, & Benson, 1996; Slomkowski et al., 2001). Siblings also act as partners in crime, such as when they become involved together in risky behaviors such as delinquent or criminal acts or substance use (Rodgers, Rowe, & Harris, 1992).

Closely related to sibling deviancy training and reinforcement is the way that siblings expose each other to risks, including to illicit substances and antisocial peers. For instance, nearly half of 8–10th graders who reported smoking in the past month had received cigarettes from a sibling (Forster, Chen, Blaine, Perry, & Toomey, 2003). Researchers have typically studied tobacco and alcohol use in this context (e.g., Bricker, Peterson, Andersen et al., 2006; McGue et al., 1996), but a few studies have also found evidence for sibling influences on marijuana and other illegal drugs (Boyle, Sanford, Szatmari, Merikangas, & Offord, 2001; Brook et al., 1990; Needle, McCubbin, Wilson, Reineck, & et al., 1986). Adolescents also may introduce their siblings to deviant peer groups. For example, adolescents who hang out with deviant older brothers are more likely to engage in delinquent activities and use substances compared to youths who do not (Snyder et al., 2005). These studies suggest that siblings are a key influence on youths’ antisocial behavior through encouraging each other to engage in delinquency and/or providing each other with opportunities to do so.

Some research has examined the nature and effects of sibling dynamics on externalizing behavior problems for particular subgroups, frequently yielding similar findings as those for non-selected samples. For example, among typically-developing children, sibling warmth is negatively linked to externalizing problems (Branje, van Lieshout, van Aken, & Haselager, 2004). Similarly, warm sibling relations predict fewer behavior problems at school among intellectually disabled children (Floyd, Purcell, Richardson, & Kupersmidt, 2009).

Siblings are of course not the only influence on youths’ development of coercive behavioral repertoires, conduct problems, and substance use—parents and peers are also strong influences. Because risk factors tend to covary and influence each other, effects on mental health and problem behavior that appear as sibling influences may in fact be due to harsh parenting, negative parent modeling, peer deviance, or other correlated risk factors. However, several of the studies cited above document sibling effects on youth substance use after controlling for parenting or parental use, respectively. Other studies demonstrate the same controlling for genetic, peer, and/or other family factors (Bahr, Hoffmann, & Yang, 2005; Fagan & Najman, 2005; Rende et al., 2005; Trim et al., 2006). Moreover, the associations between sibling use are robust across cultural and ethnic groups and contexts (e.g., East & Khoo, 2005; East & Shi, 1997; Karcher & Finn, 2005; Rosario-Sim & O'Connell, 2009).

How important are sibling influences on substance use compared to two other important factors: parents and peers? Research has shown that sibling substance use has a relatively equal (Bricker, Peterson, Andersen et al., 2006; Bricker et al., 2007; Bricker, Peterson, Leroux et al., 2006) or stronger (Fagan & Najman, 2005) influence on adolescent use than does parent use. Estimates for peer influence, however, typically exceed those for sibling influence (but see Stormshak, Comeau, & Shepard, 2004). However, it is important to recognize three factors that may inflate the estimation of peer effects compared to sibling effects: (1) Levels of peer use are frequently assessed by an adolescent’s own report of friend behavior, inflating peer-self associations due to both shared measurement effect and cognitive biases in the perception of peer behavior; (2) peer-self associations are a result of both selection and influence, whereas siblings do not select each other; and (3) sibling use predicts peer use (Windle, 2000). Thus estimating sibling effects while controlling for peer influence likely understates the total impact of sibling effects.

Theoretical Model of Sibling Effects

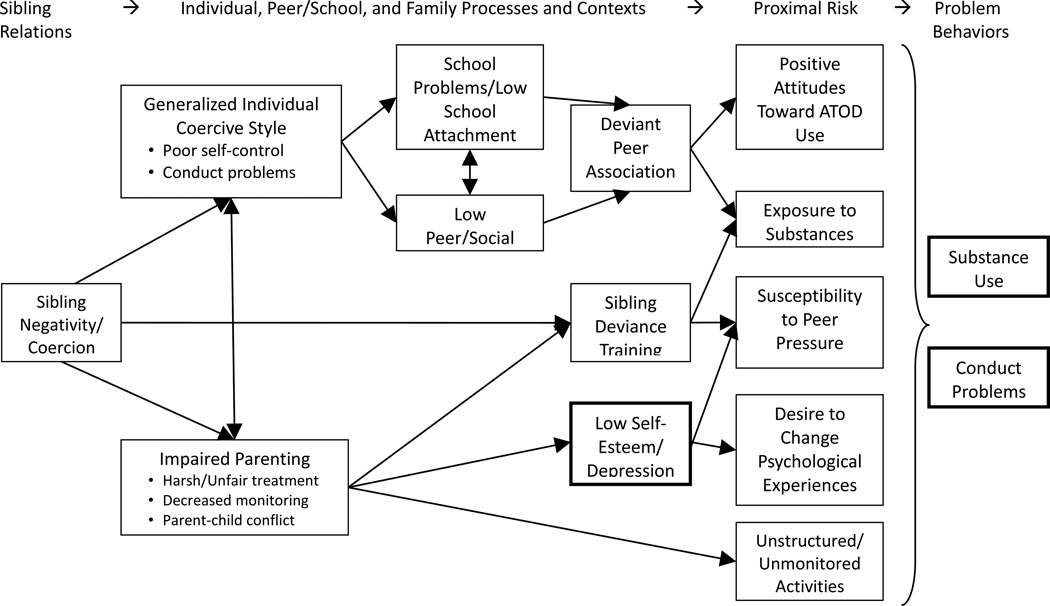

Our theoretical model (Figure 1) encompasses the key pathways through which siblings and sibling relationships affect youth adjustment. The model is grounded in the literature reviewed above and shows how sibling negativity acts as a common risk factor for three processes that lead to the development of internalizing and externalizing problems. These sibling influence pathways operate through the peer and family contexts, which lead to proximal risk factors such as exposure to substances and susceptibility to peer pressures, and eventual ATOD use and conduct problems.

Figure 1.

Pathways from sibling coercion and negativity to depression, delinquency, and substance use (bold boxes).

The first pathway, shown in the top half of Figure 1, is based on Patterson’s coercive process model (Patterson, 1982) and extends through siblings’ experiences outside the family, primarily with peers and in school settings. This part of the model proposes that negative interactions between siblings can lead children to develop a coercive interaction style, which they then generalize to peers. In turn, a coercive interpersonal style has been linked with problems at school, low social and peer competence, and affiliations with deviant peers. Youth who spend time with delinquent peer groups tend to have more positive attitudes toward ATOD use and more opportunities to use substances, both of which are proximal risk factors for actual use and delinquent behaviors.

The second and third pathways operate largely through family relationships. Sibling deviance training is shown in the middle of Figure 1. As suggested by Slomkowski et al. (2001) and Snyder and colleagues (2005), siblings who engage in conflict are more likely to collude together in delinquent activities. In addition, older siblings may expose their younger sisters or brothers to more mature peers who are more likely to engage in substance use or deviant behaviors than peers closer to their own age. When younger siblings spend time with these older peers groups, they have more opportunities and possibly more pressure to use substances.

The third sibling influence pathway concerns the evocative effects of sibling conflict on parenting quality, depicted in the bottom half of Figure 1. The notion of evocative sibling relationship effects is grounded in theory and research that suggest that sibling relationships reciprocally influence and are influenced by other family dynamics. More specifically, coercive sibling interaction patterns are a substantial stressor for parents (McHale & Crouter, 1996) and may disrupt competent, engaged parenting (Brody, 2003; Dishion et al., 2004; Patterson et al., 1984). In turn, disrupted parenting reduces parents’ ability to monitor sibling relationships and activities, blunting parents’ abilities to detect and disrupt sibling deviance training and reinforcement. In addition, harsh parenting and decreased involvement are linked with lower self-esteem and higher risk for depression among youth (e.g., Jacobson & Crockett, 2000). We hypothesize that depression and low self-esteem are proximal risk factors for susceptibility to negative peer influences related to delinquency and substance use. Dysphoric feelings may also lead to a desire to change psychological experiences, which may motivate substance use and other risky behaviors.

It is likely that structural features of the sibling relationship, such as gender dyad composition, birth order, and age spacing, moderate the strength and perhaps existence of some paths in the model. For example, Slomkowki et al’s (2001) work suggests that deviance training may be most prominent in brother-brother pairs. Our model, however, is meant to illustrate general sibling influence processes that apply to most dyads.

This theoretical model is distinct from most others in the developmental and family literatures in that we are considering the sibling relationship as the third rail—driving both individual adjustment and family dynamics. Our model is related to but distinct from a child-effects perspective, which corrected an over-emphasis on parental socialization by recognizing the influence that children have on parents and parenting (Bell, 1968). By focusing on sibling effects our model highlights how relationships within families--not just individual child behaviors—affect family members and dynamics. In this way, our model is consistent with that on interparental relationships (Emery & O'Leary, 1982; Feinberg, 2003), which places the couple relationship at the center of both individual and family adjustment. However, unlike most family systems theories, our model incorporates developmental processes that extend beyond the family, thus linking family and extra-familial processes. Although we have not included bidirectional arrows, these peer and school factors undoubtedly feedback to influence youth adjustment and family dynamics And, our model of the role of sibling effects on family and individual adjustment directs attention to the potential utility of intervention programs that aim to reduce youth’s risk for substance use by targeting sibling dynamics.

Sibling-Focused Preventive Interventions

Given the growing body of research on the important role of siblings and sibling relationships in the development of antisocial behaviors, a logical step is to apply these findings to a prevention/intervention framework designed to target sibling dynamics. The popular press provides ample advice for parents on strategies for reducing sibling conflict and rivalry; however, empirically-validated, family focused, and especially, prevention-oriented approaches are rare. Kramer outlined the gaps in intervention research on sibling relationships: although published studies report positive intervention effects suggesting that sibling relationships are malleable in childhood, the vast majority of studies target parents (usually mothers) rather than siblings themselves, focus on minimizing problem behaviors and problematic relationship characteristics rather than promoting positive ones, examine small and often clinical samples, fail to include non-intervention comparison groups, assess only immediate but not long-term intervention effects, and have not been disseminated for widespread use (Kramer, 2004). We discuss the few notable exceptions to a non-experimental approach below; but first we discuss how sibling influence processes may have contradictory implications for prevention programs, leading to the possibility of iatrogenic effects of sibling-focused intervention.

Iatrogenic effects?

On the one hand, one expects that efforts to reduce coercive exchanges and enhance positive interactions between siblings should lead to reduced levels of siblings’ antisocial tendencies through the pathways described above. These reductions in levels of antisocial behavior and attitudes should decrease sibling deviancy training. On the other hand, the same efforts to enhance sibling relationships and decrease sibling coercion/negativity should lead to increases in siblings’ time together, more advice-giving and support by older siblings, and more modeling by younger siblings. These consequences may lead to greater sibling modeling and, given that older youth are normatively more engaged in antisocial and substance use behaviors than younger youth, greater deviancy training of younger siblings.

The concern about iatrogenic effects seems ironic, given that the active ingredients of a sibling relationship-focused preventive intervention would be to build positive relationships and skills. However, we note that concern regarding the negative influence of family members is common in some areas of family-focused intervention. For example, couple-oriented prevention and treatment providers are careful to decide when joint sessions may be contra-indicated, frequently based on a history and potential for violence in the couple. And contact with antisocial fathers appears to have negative effects on children (DeGarmo, 2010).

Although care regarding potential iatrogenic effects is called for, a thorough reading of the research on sibling deviancy training and related research reveals three sets of findings suggesting that positive sibling relationships may not have a causal effect on increasing sibling deviancy, or at least not at all phases of development. The first set of findings pertains to developmental timing. As Patterson et al. (1989) and others have suggested, research on coercive processes has been largely conducted with middle childhood-aged siblings, whereas evidence for deviancy training/exposure processes has largely come from work with adolescent siblings (e.g., Rowe & Gulley, 1992; Slomkowski et al., 2001). For younger children, sibling relationship experiences may influence children’s social behavior repertoires. For adolescents, in contrast, social interaction styles may be better established and therefore less malleable; at this age, when opportunities and capacity for antisocial behavior are greater, deviancy training/exposure processes may be more relevant (Slomkowski et al., 2001). This developmental framework leads to the view that prevention programming with siblings in childhood should be directed at enhancing the sibling relationship in order to decrease the effects of sibling coercion on each child’s behavioral repertoire as well as to remove stress on other parts of the family system.

A second issue pertains to Slomkowski et al.’s (2001) findings that both negativity and warmth in the sibling relationship, in combination with the older sibling’s delinquency, predicted delinquency in younger siblings (see also Rowe & Gulley, 1992). Importantly, these authors concluded that siblings who both scored high in delinquency in their sample “seem to have relationships that are characterized by high levels of hostility-coercion as well as much warmthsupport” (p. 280). They suggested that, “antisocial brothers may have an aggressive but ‘buddies’ relationship in which they enjoy their own and others’ antisocial behavior” (p. 281). The idea that the combination of highly positive and highly negative relationship experiences has negative implications for siblings is consistent with research that has used a person-oriented approach to typologize sibling relationships. Sheehan, for example, found higher levels of family problems for siblings in “affect intense” (i.e., high in warmth and conflict) relationships as compared to those who displayed other relationship patterns, e.g., high warmth and low conflict (Sheehan, 2004; see McGuire, McHale, & Updegraff, 1996 and Stormshak, Bellanti, & Bierman, 1996 for similar typological analyses). Taken together, these analyses imply that an intervention that lowers sibling negativity while increasing sibling warmth may minimize deviancy training processes.

A final issue is that the causal direction of effects linking sibling relationship quality and delinquency has not been clarified. For example, although cross-sectional analyses in one study revealed that higher levels of sibling support were linked to greater modeling of siblings’ problem behaviors, longitudinal analyses of the same sample show that lower sibling support predicted higher levels of modeling of siblings’ problem behaviors (Branje, 2004). Thus, it may be that the deviancy training process creates positive affect, thereby generating higher levels of sibling warmth. Indeed, coding of sibling deviancy training processes from videotaped sibling interaction includes joint positive affect expressed in relation to antisocial conversation themes (Bullock & Dishion, 2002; Stormshak et al., 2004). This process may account for the finding that sibling pairs with high levels of sibling deviancy training/exposure exhibit high levels of both positivity and negativity.

Thus, research suggests that the promotion of sibling warmth—at least before adolescence—may not lead to increased sibling deviance training and collusion. However, the lessons drawn from passive research are only rough and fallible guides to what we might expect to be the consequences of an intervention. It is always the case that interventions should be administered cautiously with an ongoing assessment of iatrogenic effects.

Examples of sibling-focused programs

Bank and colleagues have focused on siblings at elevated risk for conduct problems (Bank, Snyder, Prescott, & Rains, 2004). Grounded in a social learning approach, they tested a sibling relationship intervention for dyads in which one or both children evidenced significant antisocial behavior. Sibling pairs attended eight sessions that focused on enhancing their relationship, fostering each sibling’s socially skilled behavior, and reducing conflict and aggression. The sessions involved a single sibling dyad and were facilitated by one or two interventionists who utilized a behavioral reinforcement approach. Parents were provided with information about what was taught in each session and coached in how to support and reinforce their children’s practice of behaviors at home. Results of a randomized trial supported the view that a sibling relationship focused intervention can lead to effects that generalize beyond family relationships. Bank compared parent management training (PMT) to a control condition and to PMT in conjunction with the sibling dyad intervention (PMT+sibling). Both the PMT and PMT+sibling arms of the trial were associated with less growth of antisocial behavior by parent report compared to the control group; however, teachers rated the PMT+sibling participants as lower in antisocial behavior and deviant peer association and higher in academic progress and positive peer association than both the control and PMT-only groups. Moreover, playground observations indicated the PMT+sibling group had lower rates of negative peer interaction and social isolation than the other two groups (Lew Bank, personal communication). The program is currently being adapted for use with sibling pairs living together or apart in foster care.

Kramer’s More Fun with Sisters and Brothers program (MFWSB, Kennedy & Kramer, 2008) is a universal social skills training program for sibling pairs 4 to 8 years in age. The goal of MFWSB was to promote prosocial sibling relationships and reduce conflict by teaching children emotion regulation skills. MFWSB was grounded in research on peer relationships which suggests that children who are better able to regulate their negative emotions and take another individual’s perspective are able to respond effectively to a variety of social situations and have more positive outcomes (Eisenberg, Losoya, & Spinrad, 2003; Eisenberg, Valiente et al., 2003). Given that sibling relationships can be emotionally charged and frustrating for young children, Kramer and colleagues reasoned that teaching children how to regulate their emotions would improve sibling relationships and foster positive adjustment. In MFWSB, sibling pairs attended small group sessions where they learn skills such as problem solving, identifiying emotions, and how to appropriately accept or decline a sibling’s invitation to play. Parents were able to observe these training sessions through a video monitoring system and were instructed in how to promote and reinforce positive sibling interactions at home. The program has shown modest positive effects for increasing sibling warmth and reducing parents’ need to intervene around children’s emotionality, high activity levels, and misbehavior.

Ross and colleagues developed a mediation training intervention for parents of siblings in middle childhood. Although sibling conflict is common (Berndt & Bulleit, 1985), research suggests that conflict should not necessarily be avoided because children can learn valuable negotiation and perspective-taking skills (Dunn & Munn, 1986; Foote & Holmes-Lonergan, 2003). The purpose of this intervention was to teach parents to help their children engage in constructive approaches to conflicts with their siblings, rather than resorting to anger and aggression. In this brief intervention, mothers received 90 minutes of conflict mediation training, which focused on how to allow siblings to resolve problems on their own and to help guide the siblings through the process of developing their own resolutions. A short-term evaluation revealed that siblings in the intervention condition showed less conflict and were better able to compromise, and that younger siblings took a more active role in the conflict resolution process compared to a control group (Siddiqui & Ross, 2004; Smith & Ross, 2007).

Finally, we have developed a sibling-focused intervention that builds on the theoretical model depicted in Figure 1 and targets the sibling influence processes described above. Siblings Are Special (SAS) is a universal prevention program for fifth graders, their younger siblings, and their parents. The long-term program goal is to reduce siblings’ risk for negative adjustment and substance use. Small groups of sibling pairs attend 12 weekly after school sessions for 1.5 hours. In addition, parents and children participate in three family nights which involve separate child and parent sessions and a joint session during which parents and children practice their new skills.

SAS addresses the direct influences that siblings have on one another through their dyadic interactions by teaching children problem solving and emotion regulation skills, fostering a sense of teamwork between siblings, and encouraging siblings to spend time together in constructive activities. We expect these to lead to decreased sibling conflict and enhanced intimacy. In turn, we expect that improving the sibling relationship will lead to more positive peer relationship and lower risk for academic problems and substance use. These skills are taught to children in other prevention and social-emotional literacy programs--including programs that served as models for certain aspects of SAS, such as PATHS (Greenberg, Kusche, Cook, & Quamma, 1995) and the Fast Track social skills training curriculum (Bierman, Greenberg, & Conduct Problems Prevention Research, 1996). However, we believe that the teaching and practicing of these skills in the sibling relationship context adds an important element. The intensity of the sibling relationship and the immediate opportunity for generalization of behavior to the home setting are potentially powerful factors that may enhance internalization of relationship skills.

Consistent with our theoretical model in Figure 1, SAS also targets sibling influence processes that operate through family relationships. First, there are a number of program components directed at disrupting deviancy training. For example, older siblings are asked to consider how they and their peers might negatively affect younger siblings, and then generate proactive steps to take in certain situations (e.g., older sibling’s best friend lights up a cigarette). We also focus on increasing siblings’ shared time in structured, constructive activities and in activities in the company of parents, as suggested by research linking positive youth adjustment to involvement in supervised and constructive activities (Larson & Verma, 1999). In the context of the family nights, we include a module that educates parents about deviance training/exposure processes and parents’ role in monitoring sibling exchanges. Family nights also focus on teaching parents behavioral management techniques that utilize the tools introduced to siblings in their sessions (e.g., a traffic light symbol for behavioral control, a talking stick which facilitates one person speaking at a time). We expect that reducing sibling conflict will lead to decreased parental stress and increased involvement as siblings begin to resolve their own conflicts and parents do not constantly feel the need to intervene in sibling disputes. The first evaluation of SAS is currently underway.

Conclusion, Future Directions, and Practical Implications

This and other recent reviews of sibling relationships and influences (e.g., East, 2009) support the view that levels of parenting warmth and negativity influence sibling relationships, and sibling dynamics affect parents and parenting. Moreover, PDT and the quality of sibling relationships impact children’s internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. And finally, siblings’ mutual reinforcement of antisocial attitudes and behaviors is a powerful additional influence on externalizing and substance use problems. In these many ways, siblings are a driving force in one’s competence and success at school, with peers, and with romantic partners, as well as one’s difficulties with self-esteem, depression, and disruptive, delinquent, and risky behavior. These effects extend from childhood into the rest of the life course.

Less is known about the macro social and economic contexts of sibling dynamics although progress is beginning to be made. Conger and colleagues’ Iowa study of families has implicated family economic stress in the quality of sibling relationships (e.g., Conger, Conger, Elder, Lorenz, & et al., 1992), and Updegraff, McHale, Crouter and colleagues have begun to add to Brody and colleagues’ work on sibling relationships among non-white U.S. families (e.g., Brody et al., 2001; McHale, Whiteman, Kim, & Crouter, 2003; Updegraff et al., 2005). Less work has been reported utilizing similar research approaches on sibling relationships in other countries, especially in non-white, non-European countries. The family contexts of sibling relationships deserve more emphasis (Eriksen & Jensen, 2009): An important area for future work is greater understanding of the role of sibling relationships in families where child abuse or intimate partner violence exists. The questions include not only how siblings transmit such violence to each other, but also how they may buffer each other from negative effects of violence. Moreover, how do sibling relationships in such contexts affect the intergenerational transmission of violence?

The sibling context itself is another area where our understanding is not as thorough as it might be. For example, understanding of multiple sibling relationships has been lacking; most studies have stopped at two siblings. In addition, although studies of sibling relationships often do examine gender, gender composition, and birth order effects, the information is limited. A more comprehensive understanding of these factors in sibling relationships and sibling effects awaits a review devoted solely to this topic.

Although this article focused on sibling influences on mental and behavioral health problems, a better understanding of the positive role that siblings play in development is needed as well. Studies suggest that siblings can have positive influences on outcomes including social competence (Stormshak, Bellanti, Bierman et al., 1996) and adaptive relationships skills (Updegraff et al., 2000), but the processes underlying these associations have not been articulated and documented. Research on the benefits of sibling relationships could inform sibling-focused interventions and help to expand their goals to promoting positive outcomes in addition to reducing harmful sibling conflict and subsequent problem behaviors.

There is also room for progress in understanding sibling effects by conducting studies that are becoming more nuanced and methodologically sophisticated. Little work if any has focused on distinguishing among youth’s individual adjustment, sibling characteristics, and sibling relationship influences. Examining these will be difficult, as the three constructs (child characteristics, sibling characteristics, sibling relationships) are inter-correlated, and measuring the constructs in a manner that provides maximal distinctiveness requires considerable forethought. With the exception of a few notable lines of research, sibling investigation is often opportunistic—taking advantage of available datasets on families that are focused on other questions.

Although several of the best studies on siblings include longitudinal data, the use of experimental designs would provide information on causal processes regarding sibling effects. PDT is an area where causal questions remain open: To what extent are parents responding to differences in children vs. creating those differences? We hope that sibling-focused interventionists can take advantage of the experimental context provided in intervention trials to illuminate causal processes.

Given these questions and areas for future work, to what extent is our understanding of sibling relationships ready for translation into practice? We believe that there is sufficient evidence for clinicians to integrate a focus on siblings into child and family programs. For example, given the stress of sibling conflict on parents and the consequent undermining of positive parenting, parents should be introduced to effective ways to manage sibling disputes and ongoing sibling tensions. Parents also should be aware of the impact of their own harsh parenting and conflict with a partner on sibling relationships. When appropriate, the negative impact of sibling collusion and deviancy training should also be explained to parents, with support for monitoring and disrupting such processes.

Furthermore, clinicians should be alert to sibling influences: Children who are seen for mental and behavioral health problems may also be influencing, or influenced by, their siblings. For example, depressed children are likely irritable, prone to criticize, or provide low levels of support to siblings; depressed children may also be the victims of sibling bullying and abuse. Clinicians may inquire through interviews or questionnaires with parents, the target child, and siblings about sibling conflict and support as well as the perceived fairness of differential parenting. Where sibling processes are negative, additional treatment strategies (e.g., bringing siblings into the treatment process, providing additional strategies and support for parents) may be called for. Clinicians may also provide or recommend support for siblings who are coping with a family situation that includes not just a sibling’s problems but also reduced parental availability.

In these ways, we believe clinicians, researchers, and program developers may leverage the largely untapped potential of sibling relationships to promote more positive developmental outcomes.

Acknowledgements

The authors recognize and appreciate support for this line of work from the National Institute of Drug Abuse, grant DA025035-02.

References

- Bahr SJ, Hoffmann JP, Yang X. Parental and Peer Influences on the Risk of Adolescent Drug Use. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2005;26(6):529–551. doi: 10.1007/s10935-005-0014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review. 1977;84(2):191–215. doi: 10.1037//0033-295x.84.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bank L, Burraston B. Abusive home environments as predictors of poor adjustment during adolescence and early adulthood. Journal of Community Psychology. 2001;29(3):195–217. [Google Scholar]

- Bank L, Burraston B, Snyder J. Sibling conflict and ineffective parenting as predictors of adolescent boys' antisocial behavior and peer difficulties: Additive and interactional effects. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2004;14(1):99–125. [Google Scholar]

- Bank L, Patterson GR, Reid JB. Negative sibling interaction patterns as predictors of later adjustment problems in adolescent and young adult males. In: Brody GH, editor. Sibling relationships: Their causes and consequences. Advances in applied developmental psychology. Vol. viii. Westport, CT: Ablex Publishing; 1996. pp. 197–229. [Google Scholar]

- Bank L, Snyder J, Prescott A, Rains L. Sibling relationship intervention in the prevention and treatment of antisocial behavior: Rationale, description, and advantages. 2004 Unpublished report. [Google Scholar]

- Bell RQ. A reinterpretation of the direction of effects in studies of socialization. Psychological Review. 1968;75:81–95. doi: 10.1037/h0025583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt TJ, Bulleit TN. Effects of sibling relationships on preschoolers' behavior at home and at school. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21(5):761–767. [Google Scholar]

- Bierman KL, Greenberg MT. Conduct Problems Prevention Research, G. Social skills training in the Fast Track Program. In: Peters RD, McMahon RJ, editors. Preventing childhood disorders, substance abuse, and delinquency. Banff international behavioral science series. Vol. 3. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.; 1996. pp. 65–89. [Google Scholar]

- Boyle MH, Sanford M, Szatmari P, Merikangas K, Offord DR. Familial influences on substance use by adolescents and young adults. Canadian Journal of Public Health. 2001;92:206–209. doi: 10.1007/BF03404307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branje SJT, van Lieshout CFM, van Aken MAG, Haselager GJT. Perceived support in sibling relationships and adolescent adjustment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45(8):1385–1396. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branje SJT, vL CFM, van Aken MAG, Haselager GJT. Perceived support in sibling relationships and adolescent adjustment. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker JB, Peterson AV, Jr, Andersen MR, Leroux BG, Rajan KB, Sarason IG. Close friends', parents', and older siblings' smoking: Reevaluating their influence on children's smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2006;8(2):217–226. doi: 10.1080/14622200600576339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker JB, Peterson AV, Jr, Andersen MR, Sarason IG, Rajan BK, Leroux BG. Parents' and older siblings' smoking during childhood: Changing influences on smoking acquisition and escalation over the course of adolescence. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9(9):915–926. doi: 10.1080/14622200701488400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker JB, Peterson AV, Jr, Leroux BG, Andersen MR, Rajan KB, Sarason IG. Prospective prediction of children's smoking transitions: Role of parents' and older siblings' smoking. Addiction. 2006;101(1):128–136. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01297.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH. Parental monitoring: Action and reaction. In: Crouter Ann C., Booth Alan., editors. Children's influence on family dynamics: The neglected side of family relationships. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers; 2003. pp. 163–169. (2003) x, 269 pp.SEE BOOK. [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Ge X, Conger R, Gibbons FX, McBride Murry V, Gerrard M, et al. The influence of neighborhood disadvantage, collective socialization, and parenting on African American children's affiliation with deviant peers. Child Development. 2001;72(4):1231–1246. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Ge X, Kim SY, Murry VM, Simons RL, Gibbons FX, et al. Neighborhood disadvantage moderates associations of parenting and older sibling problem attitudes and behavior with conduct disorders in African American children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71(2):211–222. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Kim S, Murry VM, Brown AC. Longitudinal direct and indirect pathways linking older sibling competence to the development of younger sibling competence. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39(3):618–628. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.39.3.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Stoneman Z, Burke M. Child temperaments, maternal differential behavior, and sibling relationships. Developmental Psychology. 1987;23(3):354–362. [Google Scholar]

- Brook JS, Whiteman M, Gordon AS, Brook DW. The role of older brothers in younger brothers' drug use viewed in the context of parent and peer influences. Journal of Genetic Psychology. 1990;164(4):453–471. doi: 10.1080/00221325.1990.9914644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock BM, Bank L, Burraston B. Adult sibling expressed emotion and fellow siblingn deviance: A new piece of the family process puzzle. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16(3):307–317. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.3.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullock BM, Dishion TJ. Sibling collusion and problem behavior in early adolescence: Toward a process model for family mutuality. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:143–153. doi: 10.1023/a:1014753232153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Button DM, Gealt R. High risk behaviors among victims of sibling violence. Journal of Family Violence. 2009;25:131–140. [Google Scholar]

- Cole A, Kerns KA. Perceptions of sibling qualities and activities of early adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2001;21(2):204–226. [Google Scholar]

- Conger KJ, Conger RD. Differential parenting and change in sibling differences in delinquency. Journal of Family Psychology. 1994;8:287–302. [Google Scholar]

- Conger KJ, Conger RD, Scaramella LV. Parents, siblings, psychological control and adolescent adjustment. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1997;12:113–138. [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Conger KJ, Elder GH, Lorenz FO, et al. A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development. 1992;63(3):526–541. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conger RD, Rueter MA. Siblings, parents, and peers: A longitudinal study of social influences in adolescent risk for alcohol use and abuse. In: Brody Gene H., editor. Sibling relationships: Their causes and consequences. Advances in applied developmental psychology. Vol. 10. Westport, CT, US: Ablex Publishing; 1996. pp. 1–30. (1996) viii, 263 pp.SEE BOOK. [Google Scholar]

- Deal JE. Marital conflict and differential treatment of siblings. Family Process. 1996;35(3):333–346. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1996.00333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGarmo DS. Coercive and Prosocial Fathering, Antisocial Personality, and Growth in Children’s Postdivorce Noncompliance. Child Development. 2010;81:503–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01410.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deković M, Buist KL. Multiple Perspectives Within the Family: Family Relationship Patterns. Journal of Family Issues. 2005;26(4):467–490. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Nelson SE, Bullock BM. Premature adolescent autonomy: Parent Disengagement and deviant peer process in the amplification of problem behaviour. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;27(5):515–530. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Patterson GR, Stoolmiller M, Skinner ML. Family, school, and behavioral antecedents to early adolescent involvement with antisocial peers. Developmental Psychology. 1991;27(1):172–180. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J. Siblings, emotion, and development of understanding. In: Braten S, editor. Intersubjective communication and emotion in early ontogeny: Studies in emotion and social interaction. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1998. pp. 158–168. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J, Deater-Deckard K, Pickering K, Golding J. Siblings, parents, and partners: Family relationships within a longitudinal community study. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry & Allied Disciplines. 1999;40(7):1025–1037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J, Munn P. Sibling quarrels and maternal intervention: Individual differences in understanding and aggression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1986;27:583–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1986.tb00184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East PL. Adolescents’ relationships with siblings. In: Lerner RM, Steinberg L, editors. Handbook of adolescent psychology. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2009. pp. 43–73. [Google Scholar]

- East PL, Khoo ST. Longitudinal pathways linking family factors and sibling relationship qualities to adolescent substance use and sexual risk behaviors. Journal of Family Psychology. Special Issue: Sibling Relationship Contributions to Individual and Family Well-Being. 2005;19(4):571–580. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.19.4.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East PL, Rook KS. Compensatory patterns of support among children's peer relationships: A test using school friends, nonschool friends, and siblings. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28(1):163–172. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.28.1.163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- East PL, Shi CR. Pregnant and parenting adolescents and their younger sisters: The influence of relationship qualities for younger sister outcomes. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1997;18(2):84–90. doi: 10.1097/00004703-199704000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Losoya S, Spinrad T. Affect and prosocial responding. New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg N, Valiente C, Morris AS, Fabes RA, Cumberland A, Reiser M, et al. Longitudinal relations among parental emotional expressivity, children's regulation, and quality of socioemotional functioning. Developmental Psychology. 2003;39(1):3–19. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.39.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery R, O'Leary KD. Children's perceptions of marital discord and behavior problems of boys and girls. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1982;10:11–24. doi: 10.1007/BF00915948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JA, Bang H, Botvin GJ. Which psychosocial factors moderate or directly affect substance use among inner-city adolescents? Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(4):700–713. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen S, Jensen V. A push or a punch : Distinguishing the severity of sibling violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2009;24:183–208. doi: 10.1177/0886260508316298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AA, Najman JM. The relative contributions of parental and sibling substance use to adolescent tobacco, alcohol, and other drug use. Journal of Drug Issues. 2005;35(4):869–884. [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME. The internal structure and ecological context of coparenting: A framework for research and intervention. Parenting: Science and Practice. 2003;3(3):95–131. doi: 10.1207/S15327922PAR0302_01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME, Neiderhiser JM, Reiss D, Hetherington EM, Simmens S. Sibling comparison of differential parental treatment in adolescence: Gender, self-esteem, and emotionality as mediators of the parenting-adjustment association. Child Development. 2000;71:1611–1628. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinberg ME, Reiss D, Hetherington EM. Differential parental treatment as a within-family process. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Festinger A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations. 1954;7:117–140. [Google Scholar]

- Floyd FJ, Purcell SE, Richardson SS, Kupersmidt JB. Sibling relationship quality and social functioning of children and adolescents with intellectual disability. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities. 2009;114(2):110–127. doi: 10.1352/2009.114.110-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foote RC, Holmes-Lonergan HA. Sibling conflict and theory of mind. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2003;21(1):45–58. [Google Scholar]

- Forster J, Chen V, Blaine T, Perry C, Toomey T. Social exchange of cigarettes by youth. Tobacco Control. 2003;12:148–154. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.2.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Buhrmester D. Age and sex differences in perceptions of networks of personal relationships. Child Development. 1992;63(1):103–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb03599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Giberson RS. Identifying the links between parents and their children's sibling relationships. In: Shulman S, editor. Close relationships and socioemotional development. Human development. Vol. 7. Norwood, NJ, USA: Ablex Publishing Corp.; 1995. pp. 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Lanthier R. Parenting siblings. In: Bornstein Marc H., editor. Handbook of parenting: Vol. 1: Children and parenting (2nd ed.) Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers; 2002. pp. 165–188. (2002) xxxviii, 418 pp.SEE BOOK. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia MM, Shaw DS, Winslow EB, Yaggi KE. Destructive sibling conflict and the development of conduct problems in young boys. Developmental Psychology. 2000;36(1):44–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gass K, Jenkins J, Dunn J. Are sibling relationships protective? A longitudinal study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2007;48(2):167–175. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gau SSF, Chong M-Y, Yang P, Yen C-F, Liang K-Y, Cheng ATA. Psychiatric and psychosocial predictors of substance use disorders among adolescents. Longitudinal study. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;190(1):42–48. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.022871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg MT, Kusche CA, Cook ET, Quamma JP. Promoting emotional competence in school-aged children: The effects of the PATHS curriculum. Development and Psychopathology. 1995;7:117–136. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez DJ. Child development and social demography of childhood. Child Development. 1997;68:149–169. [Google Scholar]

- Howe N, Aquan Assee J, Bukowski WM, Lehoux PM, Rinaldi CM. Siblings as confidants: Emotional understanding, relationship warmth, and sibling self-disclosure. Social Development. 2001;10(4):439–454. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson KC, Crockett LJ. Parental monitoring and adolescent adjustment: An ecological approach. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2000;10:65–97. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins JM, Smith MA. Factors protecting children living in disharmonious homes: Maternal reports. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1990;29(1):60–69. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199001000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kan ML, McHale SM, Crouter AC. Interparental incongruence in differential treatment of adolescent siblings: Links with marital quality. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2008;70(2) 466-466-479. [Google Scholar]

- Karcher MJ, Finn L. How Connectedness Contributes to Experimental Smoking Among Rural Youth: Developmental and Ecological Analyses. The Journal of Primary Prevention. 2005;26(1):25–36. doi: 10.1007/s10935-004-0989-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan K, Shaw DS. The development of coercive family processes: The interaction between aversive toddler behavior and parenting factors. In: McCord J, editor. Coercion and punishment in long-term perspectives. USA: Cambridge University Press; 1995. pp. 165–180. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy DE, Kramer L. Improving emotion regulation and sibling relationship quality: The More Fun With Sisters and Brothers Program. Family Relations: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Applied Family Studies. 2008;57(5):567–578. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J-Y, McHale SM, Crouter AC, Osgood DW. Longitudinal linkages between sibling relationships and adjustment from middle childhood through adolescence. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43(4):960–973. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J-Y, McHale SM, Osgood DW, Crouter AC. Longitudinal Course and Family Correlates of Sibling Relationships From Childhood Through Adolescence. Child Development. 2006;77(6):1746–1761. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowal A, Kramer L. Children's understanding of parental differential treatment. Child Development. 1997;68(1):113–126. [Google Scholar]

- Kowal A, Kramer L, Krull JL, Crick NR. Children's perceptions of the fairness of parental preferential treatment and their socioemotional well-being. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16(3):297–306. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.3.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer L. Experimental intervention in sibling relationships. In: Conger RD, Lorenz FO, Wickrama KAS, editors. Continuity and Change in Family Relations. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Larson R, Verma S. How children and adolescents spend time across the world: Work, play, and developmental opportunities. Psychological Bulletin. 1999;125(6):702–736. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.125.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin LM, Hops H, Davis B, Dishion TJ. Multimethod comparison of similarity in school adjustment of siblings and unrelated children. Developmental Psychology. 1994;29(6):963–969. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon CE. An observational investigation of sibling interactions in married and divorced families. Developmental Psychology. 1989;25(1):36–44. [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Sharma A. Parent and sibling influences on adolescent alcohol use and misuse: Evidence from a U.S. adoption cohort. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1995;57(1):8–18. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Sharma A, Benson P. Parent and sibling influences on adolescent alcohol use and misuse: Evidence from a U.S. adoption cohort. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1996;57(1):8–18. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1996.57.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGuire S, McHale SM, Updegraff K. Children's perceptions of the sibling relationship in middle childhood: Connections within and between family relationships. Personal Relationships. 1996;3(3):229–239. [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Bissell J, Kim J. Sibling relationship, family, and genetic factors in sibling similarity in sexual risk. Journal of Family Psychology. 2009;23:562–572. doi: 10.1037/a0014982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Crouter AC. The family contexts of children's sibling relationships. In: Brody GH, editor. Sibling relationships: Their causes and consequences. Advances in applied developmental psychology. Vol. 10. Norwood, NJ, USA: Ablex Publishing Corp.; 1996. pp. 173–195. [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Crouter AC. How do children exert an impact on family life? In: Crouter Ann C., Booth Alan., editors. Children's influence on family dynamics: The neglected side of family relationships. Mahwah, NJ, US: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers; 2003. pp. 207–220. (2003) x, 269 pp.SEE BOOK. [Google Scholar]