Abstract

Neurotensin receptor-1 (NTR-1) is overexpressed in colon cancers and colon cancer cell lines, Signaling through this receptor stimulates proliferation of colonocyte-derived cell lines and promotes inflammation and mucosal healing in animal models of colitis. Given the causal role of this signaling pathway in mediating colitis and the importance of inflammation in cancer development we tested the effects of NTR-1 in mouse models of inflammation-associated and sporadic colon cancer using NTR-1 deficient (Ntsr1−/−) and wild type (Ntsr1+/+) mice. In mice treated with azoxymethane (AOM) to model sporadic cancer, NTR-1 had a significant effect on tumor development with Ntsr1+/+ mice developing over 2-fold more tumors than Ntsr1−/− mice (p = 0.04). There was no effect of NTR-1 on the number of aberrant crypt foci or tumor size, suggesting that NT/NTR-1 signaling promotes the conversion of precancerous cells to adenomas. Interestingly, NTR-1 status did not affect tumor development in an inflammation-associated cancer model where mice were treated with AOM followed by two cycles of 5% dextran sulphate sodium (DSS). In addition, colonic molecular and histopathologic analyses were performed shortly after a single cycle of DSS. NTR-1 status did not affect colonic myeloperoxidase activity or histopathologic scores for damage and inflammation. However, Ntsr1−/− mice were more resistant to DSS-induced mortality (p = 0.01) and had over 2-fold higher colonic expression levels of Il6 and Cxcl2 (p < 0.04), cytokines known to promote tumor development. These results represent the first direct demonstration that targeted disruption of the Ntsr1 gene reduces susceptibility to colon tumorigenesis.

Keywords: Neurotensin receptor-1, azoxymethane, dextran sulphate sodium, aberrant crypt foci, colon cancer

INTRODUCTION

Neurotensin (NT) is a 13 amino acid peptide produced in the central nervous system and the intestine where neuroendocrine cells, specialized mucosal endocrine cells, and immune cells are the major sources 1. The effects of NT are mediated by binding to three neurotensin receptors NTR-1, -2, and -3. The first 2 are G-protein coupled receptors, while the third belongs in the sortilin receptor superfamily. The high affinity NTR-1 appears to mediate most of the NT intestinal effects as NT release in normal conditions is stimulated by luminal lipids and bile salts 2, 3. In the intestine NT stimulates gut motility and secretion and has a major role in diverse pathological conditions including immobilization stress, C. difficile toxin A-induced acute colitis, and DSS induced chronic colitis 4.

The NT/NTR-1 signaling pathway is important for eliciting a full innate immune response in the colon as well as the mucosal healing that ensues. Following oral administration of DSS, treatment with the NTR-1 specific antagonist SR 48692 exacerbates, whereas treatment with NT ameliorates mucosal damage, body weight loss, and neutrophil infiltration 5. With DSS exposure, expression of NTR-1 shifts from mainly expression in the lamina propria to predominantly in the epithelial layer, especially near epithelial erosions 5. Moreover, NTR-1-mediated signals are likely to be important for Ulcerative colitis (UC), as NTR-1 is expressed at higher levels in colonic biopsies from patients with active UC than non-involved areas 5.

NT via NTR-1 activates a variety of intracellular signaling pathways in colon cancer cells and in non-transformed NCM460 colonocytes, including the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and downstream MAPK via metalloproteinase-dependent cleavage of pro-TGF alpha 6. NT-mediated activation of MAPK signaling and of the downstream transcription factor AP1 also occurs rapidly in human colorectal and pancreatic cancer cell lines 7. Moreover, AP1 activation in response to NT transactivates the IL-8 promoter 7, 8, while NT also stimulates Ras- and NF-κB-dependent secretion of IL-8 9. NF-κB regulates inflammation-associated colorectal cancer and functions in both cell autonomous and non-autonomous mechanisms to enhance tumor development. Inhibition of NF-κB in epithelial cells reduces the number of colon tumors in response to treatment with the carcinogen azoxymethane (AOM) and DSS, while inhibition of NF-κB in immune cells reduces the size of tumors 10.

Neuropeptides, including NT are important in tumor development 11. High levels of NTR-1 expression are found in human pancreatic, lung, breast, prostate, and colon (UC-associated and sporadic) cancers 12. NTR-1 overexpression in colon cancers can be explained via increased transcription of the NTR-1 gene via TCF/Lef- and nuclear β-catenin-dependent pathways 13. Higher NT levels are also found in colon cancers compared to normal colon 14, and in vivo evidence demonstrates that NT/NTR-1 signaling is causal for tumor growth. Xenograft transplants of human colon cancer cell lines become larger following NT administration, and smaller when treated with the NTR-1 antagonist SR 48692 15. Also, NT administration to rats injected with AOM increases tumor size and invasion into the muscularis 16. Given the important role of NT/NTR-1 signaling in colitis, we examined the effect of this signaling pathway in the AOM and AOM/DSS models, well-characterized mouse models of sporadic and colitis-associated cancer, respectively. Our results indicate that in the AOM model of sporadic colon cancer, NTR-1 promotes the development of colonic adenomas in a mechanism that does not involve NTR-1 overexpression. We also show that NT/NTR-1 signaling does not affect tumor development in the AOM/DSS model, but Ntsr1 deficiency in this model is associated with increased colonic mRNA expression of cytokines known to promote colon cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal Treatment: AOM, AOM+DSS, DSS alone

Ntsr1tmDgen (hereafter called Ntsr1−/−) were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory and bred in our facility. Animals were obtained as fifth generation backcross of 129 onto C57BL6/J. We performed one additional backcross prior to intercrossing animals as Ntsr1+/− crosses to generate littermate controls for all experiments. AOM alone and AOM/DSS: To induced cancer mice were injected beginning at week 5 with 5 weekly doses of AOM given one week apart (10 mg/kg). Six weeks prior to euthanasia, one group of Ntsr1+/+ mice was administered the NTR-1 antagonist SR142948 (Sanofi) twice per week (5 mg/kg in PBS). Mice were sacrificed 20 weeks after the final dose. Alternatively, mice were treated at 6 weeks of age with a single dose of AOM (12.5 mg/kg) which was followed one week later with 2 cycles of 5% DSS administered in the drinking water for 5 days separated by 16 days of normal drinking water. Mice were euthanized 8 weeks after the final dose. Colons for tumor studies were dissected, splayed open, and fixed for 16h in formalin. Large dissectible adenomas were removed prior to formalin fixation for molecular studies with normal tissue controls dissected from the mucosal surface. After briefly staining colons in methylene blue, adenomas and ACF were scored under a stereoscope. DSS alone: Animals were treated for 5 days with 5% DSS and groups were euthanized 2 or 8 days after termination of DSS to determine short-term inflammatory and healing responses. Colons were fixed in formalin for histological scoring as previously described 17. Animal studies were approved by the institutional animal research committee of UCLA.

Myeloperoxidase assay

Myeloperoxidase assays were performed essentially as reported 18, and were adapted for a 96-well format. Briefly, whole colon tissues were taken from the mid colon and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and homogenized in 50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 6.0) containing 50 mM hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide. MPO activity was assayed on the substrate O-dianisidine dihydrochloride in 0.0005% hydrogen peroxide by measuring absorbance 460 at 30 second intervals for 2 min in a SpectraMax M5 plate reader (Molecular Dynamics).

Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was prepared from colon tumors or matched normal samples in a two-step protocol by first homogenizing in Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) and then passing supernatants mixed with 70% ethanol over RNeasy columns (Qiagen). First strand cDNA synthesis was performed using Superscript III RT (Invitrogen). Real time PCR was performed on a 7600 Fast Thermocycler using probes for Cxcl2, Il6, and Tnf (TNF-α). Results were normalized to Gapdh expression levels.

Histopathologic analysis and immunohistochemistry

Formalin fixed, paraffin-embedded colons were serially sectioned in planes parallel to the mucosal surface. ACF and adenomas were identified on H&E stained sections by scanning at 200X magnification, and adjacent sections were immunostained with Ki67 antibody (Vector Research Laboratories), with citrate unmasking, a goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000) (Vector Research Laboratories), Vectastain elite with DAB (Vector Research Laboratories). Ki67 positivity in ACF and adenomas was scored at 400× magnification as 1 for less than 5% of cells positive, 2 for 5%–35%, 3 for 35–65%, 4 for 65–95%, and 5 for over 95%. Histopathological scoring was performed on blinded sections by an accredited pathologist (GL).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism software (GraphPad). All pair-wise comparisons involving tumor and ACF numbers, gene expression, MPO activity, histopathological scoring, and Ki67 immunostaining were compared using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test. Kaplan-Meier survival curves following DSS exposure were compared with the log-rank test.

RESULTS

NT/NTR-1 signaling promotes tumor development in the AOM model of sporadic colon cancer

To determine the effect of NT/NTR-1 signaling on colon cancer progression in mice we subjected mice to treatment with the alkylating carcinogen AOM. We found that Ntsr−/− mice had a significant 2-fold reduction in the number of colon tumors per mouse compared to Ntsr+/+ mice (p = 0.04, Mann-Whitney) (Fig 1B). Interestingly, there was no difference in the number of ACF demonstrating that NTR-1 has no effect on early stages of cancer development (Fig 1A). Consistent with this observation, Ntsr+/+ mice that were treated with the NTR-1 antagonist SR142949 had a mean tumor multiplicity that was intermediate to both groups. Furthermore, this group had identical ACF numbers to both Ntsr−/− and Ntsr+/+ mice. There was a bimodal distribution in tumor size, in all groups, yet there were no differences in average tumor sizes among Ntsr−/−, Ntsr+/+, or SR142949–treated mice (Fig 1C). Similar to previous reports on AOM-induced tumors in C57BL/6 mice, pedunculated adenomas were the most advanced lesions in our study 19, 20. Because human colon cancers have been reported to overexpress NTR-1 we examined expression in wild type mice of Ntsr1 in large adenomas compared to normal tissues dissected from adjacent non-involved mucosa. Unlike human colon cancers, every mouse adenoma tested showed a dramatic reduction below the level of detection in Ntsr1 mRNA (Fig 1D) demonstrating the potent effect of native levels of Ntsr1 expression on the early stages of colon carcinogenesis.

Figure 1. ACF and Adenoma development following AOM treatment.

Female Ntsr1+/+ (n = 12) and Ntsr1−/− (n = 11 mice) were treated with AOM and euthanized 20 weeks after the last dose. Additionally, a group of Ntsr1+/+ mice (n = 8) was treated with the NTR-1 antagonist SR142948. ACF (A) and adenomas (B) were scored in formalin fixed whole mounts after brief staining with methylene blue. Adenoma diameter was measured with a calibrated ocular reticle (C). Adenomas (6 tumors from 5 mice) and normal colon tissues (6 mice) were dissected from AOM-treated Ntsr1+/+ mice and used for cDNA preparation. Real time PCR was performed to measure Ntsr1 expression and results are presented as relative expression levels with mean expression from the normal colon set to 1 (D).

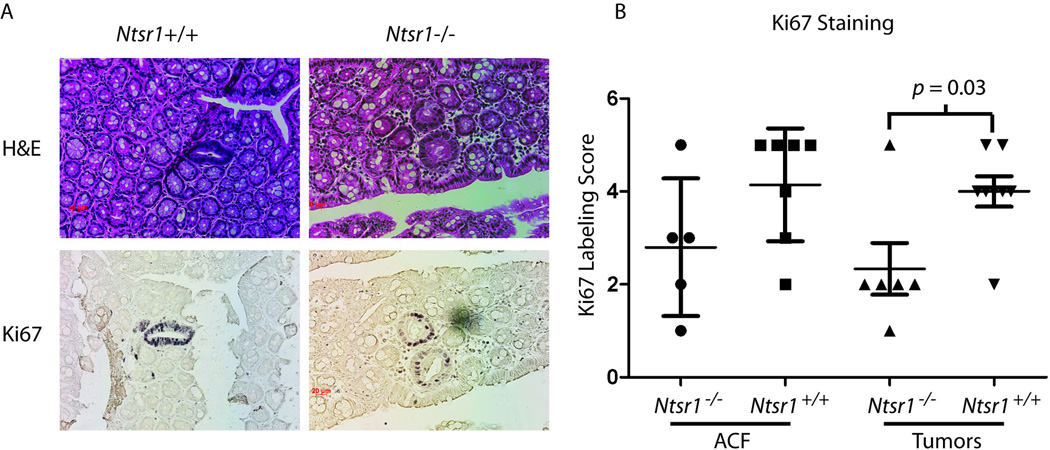

To determine whether the reduction in tumor multiplicity was associated with reduced proliferation, we examined Ki67 staining in ACF and microscopic adenomas (Fig 2A). We found that early adenomas had a modest, but statistically significant reduction in Ki67 staining index (p = 0.03, Mann-Whitney). Results with ACF paralleled the small adenomas with Ntsr−/− having a lower mean the Ki67 staining index than Ntsr+/+, but the effect was not significant (Fig 2B).

Figure 2. Ki67 labelling indices.

Formalin fixed whole mounts were sectioned serially in planes parallel to the mucosal surface. Adjacent sections were stained with H&E or immunostained with Ki67. Representative H&E and Ki67 stained ACF (400X original magnification) from Ntsr1+/+ and Ntsr1−/− colons (A). Labeling indices from adenomas and ACF (B) with p-values calculated using the Mann-Whitney test.

Ntsr1 effects on colitis and colitis-associated cancer

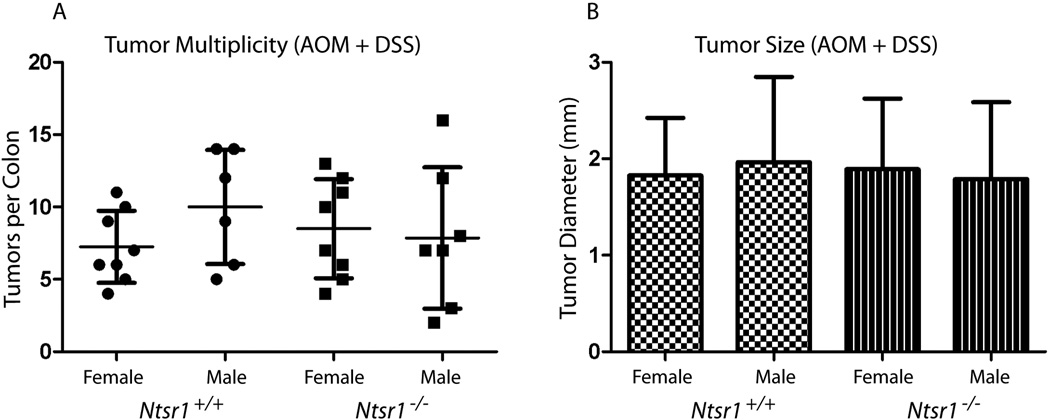

NT/NTR-1 signaling has been demonstrated to affect the degree of inflammation and to promote mucosal healing in humans and mouse models of colitis. Therefore we sought to determine the effects of this signaling pathway in the AOM/DSS model of inflammation-associated colon tumor progression. We found that following AOM/DSS treatment that Ntsr+/+ and Ntsr−/− mice have nearly identical tumor multiplicities (Fig 3A) and tumor size distributions (Fig 3B) suggesting no effect of endogenous NT/NTR-1 signaling in this model of inflammation-associated cancer development.

Figure 3. Colon tumor development in response to AOM/DSS treatment.

Male and female Ntsr1+/+ and Ntsr1−/− mice (14–15 animals per genotype) were treated with AOM and DSS and examined for colon tumor multiplicity (A) and diameter (B).

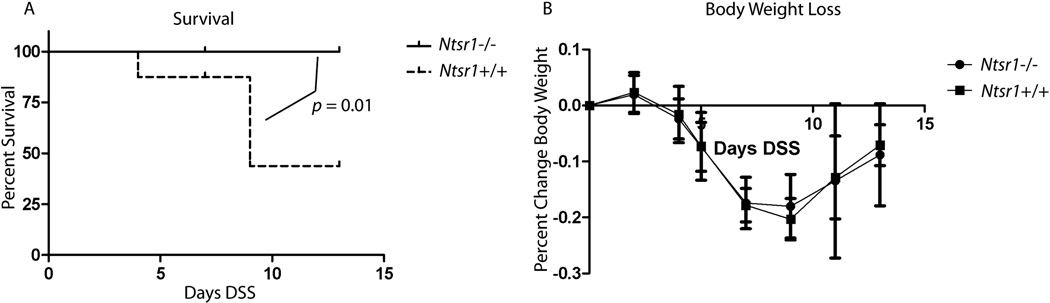

To determine the effect of NTR-1 on the degree of colitis in response to DSS treatment we exposed mice to 5% DSS in the drinking water for 5 days. Groups of mice were euthanized 2 and 8 days after treatment. We found that exposure to 5% DSS caused premature death in nearly half of the Ntsr+/+ mice but in none of the Ntsr−/− mice, and this difference was statistically significant (p = 0.01, Kaplan-Meier, log-rank) (Fig 4A). These animals either rapidly lost >20% of their body weight within a few days and became extremely moribund, or progressively lost body weight beyond the point where most mice began to recover and were euthanized in accordance with IACUC standards. Interestingly, of the mice that survived to their timed sacrifice, average body weight change in response to DSS did not differ between Ntsr−/− and Ntsr+/+ mice (Fig 4B). Similarly there was no difference in stool consistency or on presence of blood in the stool (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Ntsr1+/+ and Ntsr1−/− mice (≥ 7 mice per group) were administered 5% DSS in their drinking water for 5 days and euthanized 2 or 8 days after termination of DSS. Deaths of animals that did not survive until their timed sacrifice were recorded (A) and compared statistically using the Kaplan-Meier test statistic. Percent body weight change during and following DSS treatment was recorded (B).

Mice euthanized 2 and 8 days after treatment with DSS were examined histopathologically for the degree of inflammation, mucosal damage, and dysplasia. All histopathologic scores were normal in the untreated controls and were dramatically elevated in groups that received DSS. The extent of inflammation and epithelial damage peaked 2 days after termination of DSS, and coincided with the nadir of weight loss (Fig 4B). The highest scores for dysplasia were observed 8 days after termination of DSS during the healing phase of colitis where the epithelium expands over eroded regions of the mucosa (Supplemental Fig 1A–C). There were no significant differences between Ntsr−/− and Ntsr+/+ mice in any of these histopathological scores for damage. As another measure of the degree of inflammation we examined the extent of neutrophil activation by myeloperoxidase activity assays in extracts from mid colon. MPO activity is dramatically elevated following DSS treatment, and consistent with our findings from the histopathological scores for inflammation there were no differences between Ntsr−/− and Ntsr+/+ mice (Supplemental Fig 1D).

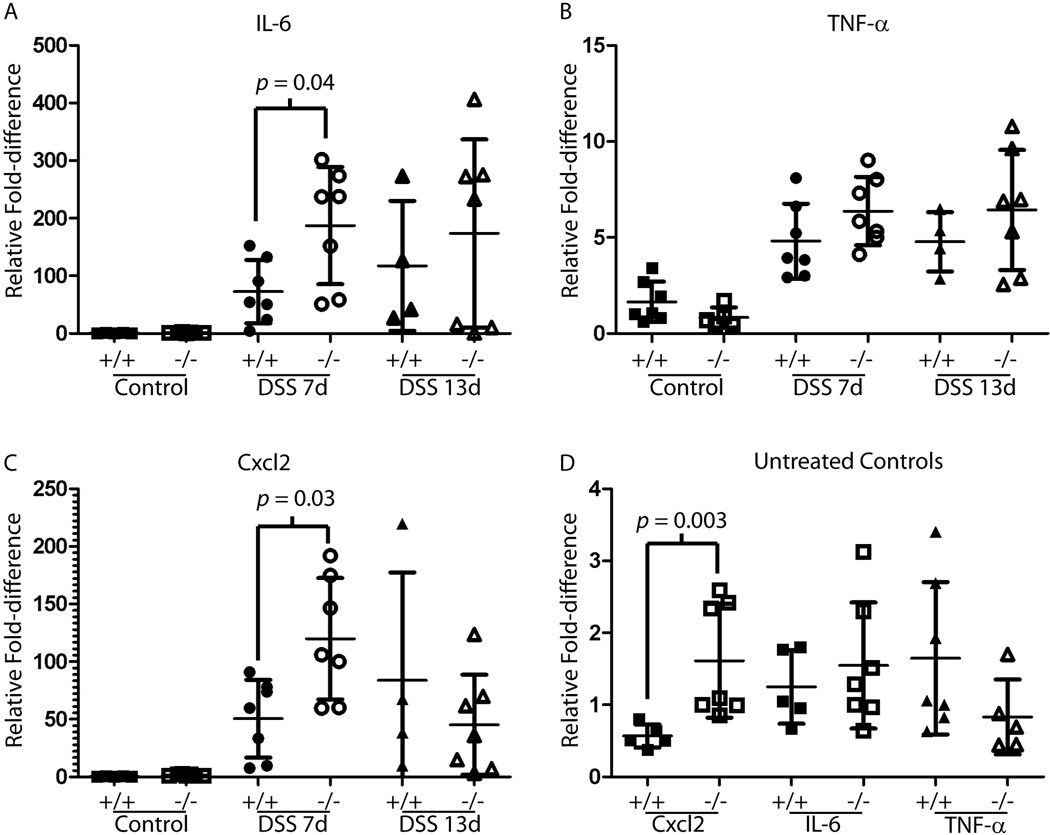

We examined cytokine expression levels in colon extracts from Ntsr−/− and Ntsr+/+ mice, and found that 2 days after termination of DSS Ntsr−/− mice had significantly higher mRNA levels for Cxcl2 and IL6 but not TNF-α (p < 0.05). (Fig 5A–C). By 8 days post-treatment there were no significant differences between Ntsr−/− and Ntsr+/+ animals. Also, baseline levels of Cxcl2 were significantly elevated in untreated control Ntsr−/− mice relative to Ntsr+/+ mice (Fig 5D).

Figure 5.

Complementary DNA from DSS treated and untreated animals was prepared from mid colon tissue and examined for expression by real time PCR quantification of the inflammatory cytokines IL-6 (A), TNF-α (B), and Cxcl2 (C). Because expression was significantly elevated following DSS treatment, untreated controls were plotted separately for these genes (D). Statistical significance is shown for pair-wise comparisons that were below 0.05 using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney test.

DISCUSSION

We report here that mice deficient in NTR-1 develop fewer tumors in a sporadic model of carcinogenesis providing direct evidence for an important role for NT/NTR-1 signaling in the promotion of cancer. This finding is consistent with previous reports demonstrating that this signaling pathway is causally involved in colon tumorigenesis. For example, AOM treated rats that are administered supraphysiologic levels of NT show increased tumor numbers, sizes of tumors, and local invasion into the muscularis 16. Moreover, in a subcutaneous xenograft model, administration of NT increases, while pharmacologic administration of a NTR-1 antagonist decreases tumor growth demonstrating a tumor enhancing effect of NT/NTR-1 signaling at late stages of tumor growth 15. Using Ntsr1−/− mice our studies extend these findings by demonstrating that physiologic levels of NT/NTR-1 signaling promote the early conversion of precancerous lesions to adenomas.

Interestingly, disruption of NT/NTR-1 signaling reduced the number of adenomas but not the number of precancerous ACF. ACF are considered to precursor lesions that directly develop into adenomas in humans and in animal models21, and under this model our results suggest that NT is acting to promote the conversion of precancerous growths into adenomas. Studies of inbred strains differing in susceptibility to carcinogen induced colon cancer have demonstrated that ACF can be sub-classified into lesions that are more or less likely to form adenomas19, 22. Thus it is possible that NT/NTR-1 signaling enhances development of a specific subset of ACF more prone to form adenomas. ACF are also a biologic endpoint for testing carcinogenicity as numerous ACF can develop in response to carcinogens even in mouse strains resistant to adenoma formation such as C57BL/621. AOM is a procarcinogen, and its mutagenic capacity is dependent on enzymatic oxidation by mixed function oxidases of the p450 superfamily23, and a number of hormonal factors affecting p450 expression can modify downstream tumor production 24, 25. Because the ACF number is the same in the NTR-1 proficient and deficient animals we conclude that modification of AOM mutagenicity is not the reason for our observed reduction in tumor number in Ntsr1−/− mice.

Despite the fact that there was no effect of NT/NTR-1 signaling on tumor size, we observed a small but significant effect of NT/NTR-1 on Ki67 labeling, with Ntsr1 mutant mice having lower average labeling indices than wild type mice. This suggests that the effect of NT on conversion to adenomas involves cell proliferation. This effect could be a combination of direct signaling in oncogenically transformed epithelial cells and indirect signaling mediated by stromal cells. Colon cancer development at the colonocyte level is controlled by Egfr/Ras/Mapk signaling 26, Cox-2 and prostaglandin synthesis27, Tgf-β signaling 28, Wnt 29, and NF-κB pathways 30. Indeed genetic or epigenetic alterations in these pathways are common in sporadic human colon cancers, and their causal importance in colon tumorigenesis is recapitulated in rodent models 31–33. The pattern of ACF and adenoma formation we observed with disruption of NTR-1 mimics the modification of tumor development by Cox-2 and Egfr deficiencies 33, 34. The Egfr hypomorphic wv2 mutation significantly diminishes adenoma formation in ApcMin mice but has no effect on precursor microadenomas. Interestingly, a Cox2 knockout fully abrogates development of adenomas following AOM treatment 33, while there is no apparent effect of this knockout on the number of ACF (P. Chun and H. Herschman, personal communication). NT exposure of colon cancer cell lines and immortalized human colonocytes stimulates cell proliferation through activation of the EGF receptor and Mapk pathway 35. Furthermore, other cancer related pathways such as NF-κB/IL-8 and COX2 are also stimulated by NT in colonocytes 5, 9. Thus, a combination of these downstream mediators may be responsible for the effect of NTR-1 on colon tumor development at the colonocyte level.

In support of an indirect mechanism, NT/NTR-1 signaling has been shown to modulate macrophage function 36, leading to increased cytokine release and enhanced tumor development. Along these lines, the presence of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMS) and other immune cells is a general feature of cancers of different organs, including sporadic and inflammation-associated colorectal cancers. TAMS function in the production of cytokines and growth factors is able to drive tumor proliferation, angiogenesis, and metastatic potential 37, 38.

It has been demonstrated that a substantial fraction of human colon cancers have upregulation of NTSR1 and that this could potentially result from TCF/Lef binding sites in the human NTSR1 promoter that could drive transactivation in the presence of an activated Wnt pathway 13, 39. Also, active histone deacetylases in human colon cancer cell lines are important for high levels of NTR-1 expression 40. Converse to the human results we observed a significant decrease in expression of on Ntsr1 in mouse colon tumors relative to normal colon, although almost all AOM induced tumors harbor Wnt activating mutations in the Ctnnb1 oncogene 41. Examination of the homologous region of the mouse Ntsr1 promoter indicates the absence of a recognizable TCF/Lef binding site. Similar to other studies on AOM-induced tumors, lesions in our study did not progress beyond adenomas 19, 20, and thus we cannot rule out the possibility that NTR-1 expression is reactivated during the transition to malignancy. For these reasons, future mechanistic studies on the role of this pathway in mouse models of colon carcinogenesis should employ engineered overexpression of NTR-1.

NT has been shown to promote acute intestinal inflammation in mice treated or C. dificile toxin A 4. Furthermore, NT/NTR-1 signaling has been demonstrated to promote mucosal healing following DSS treatment 5, representing a chronic colitis model. We found that in NTR-1 deficient mice the overall degree of inflammation is unchanged although deficient mice have higher colonic mRNA expression levels of the inflammatory cytokines IL-6 and Cxcl2, the mouse homolog of IL-8. Both of these cytokines have been demonstrated to promote colon carcinogenesis. There was no effect of NT/NTR-1 signaling on tumor development in the AOM/DSS model, most likely because the tumor promoting mileu created during an inflammatory reaction is well beyond a threshold that would be modified by NT/NTR-1 signaling.

Overall, our data provides strong evidence that endogenous NT/NTR-1 signaling promotes the conversion of precancerous lesions to adenomas in a mouse model of sporadic colon cancer. These results suggest that exogenous or endogenous factors that stimulate NT secretion in the gut may play a role in promoting early stages of cancer. Conversely factors that inhibit this pathway may likewise inhibit cancer formation, and thus our studies identify NT/NTR-1 as a potential target for chemoprevention.

Brief statement on importance.

Our work demonstrates for the first time that neurotensin signaling promotes the formation of adenomas in the colon.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. H&E stained colon sections from control and DSS treated mice were scored histopathologically for dysplasia (A), extent of epithelial injury (B), and extent of inflammation (C). Mid-colon tissue homogenates were assayed for myeloperoxidase activity (D).

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH RO-1 DK60729 (CP); A Pilot and Feasibility Study from CURE: Digestive Diseases Research Center 41301; and the Martin Blinder Fund for IBD Research.

Abbreviations

- NTR-1 protein, Ntsr1 gene

Neurtensin receptor-1

- NT

neurotensin

- ACF

aberrant crypt foci

- AOM

azoxymethane

- DSS

dextran sulphate sodium

References

- 1.Carraway R, Leeman SE. The isolation of a new hypotensive peptide, neurotensin, from bovine hypothalami. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:6854–6861. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dumoulin V, Moro F, Barcelo A, Dakka T, Cuber JC. Peptide YY, glucagon-like peptide-1, and neurotensin responses to luminal factors in the isolated vascularly perfused rat ileum. Endocrinology. 1998;139:3780–3786. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.9.6202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dakka T, Dumoulin V, Chayvialle JA, Cuber JC. Luminal bile salts and neurotensin release in the isolated vascularly perfused rat jejuno-ileum. Endocrinology. 1994;134:603–607. doi: 10.1210/endo.134.2.8299558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Castagliuolo I, Wang CC, Valenick L, Pasha A, Nikulasson S, Carraway RE, Pothoulakis C. Neurotensin is a proinflammatory neuropeptide in colonic inflammation. J Clin Invest. 1999;103:843–849. doi: 10.1172/JCI4217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brun P, Mastrotto C, Beggiao E, Stefani A, Barzon L, Sturniolo GC, Palu G, Castagliuolo I. Neuropeptide neurotensin stimulates intestinal wound healing following chronic intestinal inflammation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2005;288:G621–G629. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00140.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhao D, Zhan Y, Koon HW, Zeng H, Keates S, Moyer MP, Pothoulakis C. Metalloproteinase-dependent transforming growth factor-alpha release mediates neurotensin-stimulated MAP kinase activation in human colonic epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:43547–43554. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401453200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ehlers RA, Zhang Y, Hellmich MR, Evers BM. Neurotensin-mediated activation of MAPK pathways and AP-1 binding in the human pancreatic cancer cell line, MIA PaCa-2. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;269:704–708. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ehlers RA, 2nd, Bonnor RM, Wang X, Hellmich MR, Evers BM. Signal transduction mechanisms in neurotensin-mediated cellular regulation. Surgery. 1998;124:239–246. discussion 46-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhao D, Keates AC, Kuhnt-Moore S, Moyer MP, Kelly CP, Pothoulakis C. Signal transduction pathways mediating neurotensin-stimulated interleukin-8 expression in human colonocytes. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:44464–44471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104942200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greten FR, Eckmann L, Greten TF, Park JM, Li ZW, Egan LJ, Kagnoff MF, Karin M. IKKbeta links inflammation and tumorigenesis in a mouse model of colitis-associated cancer. Cell. 2004;118:285–296. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rozengurt E, Guha S, Sinnett-Smith J. Gastrointestinal peptide signalling in health and disease. Eur J Surg Suppl. 2002:23–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bossard C, Souaze F, Jarry A, Bezieau S, Mosnier JF, Forgez P, Laboisse CL. Over-expression of neurotensin high-affinity receptor 1 (NTS1) in relation with its ligand neurotensin (NT) and nuclear beta-catenin in inflammatory bowel disease-related oncogenesis. Peptides. 2007;28:2030–2035. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2007.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Souaze F, Viardot-Foucault V, Roullet N, Toy-Miou-Leong M, Gompel A, Bruyneel E, Comperat E, Faux MC, Mareel M, Rostene W, Flejou JF, Gespach C, et al. Neurotensin receptor 1 gene activation by the Tcf/beta-catenin pathway is an early event in human colonic adenomas. Carcinogenesis. 2006;27:708–716. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evers BM, Ishizuka J, Chung DH, Townsend CM, Jr, Thompson JC. Neurotensin expression and release in human colon cancers. Ann Surg. 1992;216:423–430. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199210000-00005. discussion 30-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maoret JJ, Anini Y, Rouyer-Fessard C, Gully D, Laburthe M. Neurotensin and a non-peptide neurotensin receptor antagonist control human colon cancer cell growth in cell culture and in cells xenografted into nude mice. Int J Cancer. 1999;80:448–454. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990129)80:3<448::aid-ijc19>3.0.co;2-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tasuta M, Iishi H, Baba M, Taniguchi H. Enhancement by neurotensin of experimental carcinogenesis induced in rat colon by azoxymethane. Br J Cancer. 1990;62:368–371. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1990.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meira LB, Bugni JM, Green SL, Lee CW, Pang B, Borenshtein D, Rickman BH, Rogers AB, Moroski-Erkul CA, McFaline JL, Schauer DB, Dedon PC, et al. DNA damage induced by chronic inflammation contributes to colon carcinogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2516–2525. doi: 10.1172/JCI35073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kokkotou E, Torres D, Moss AC, O'Brien M, Grigoriadis DE, Karalis K, Pothoulakis C. Corticotropin-releasing hormone receptor 2-deficient mice have reduced intestinal inflammatory responses. J Immunol. 2006;177:3355–3361. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.5.3355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nambiar PR, Girnun G, Lillo NA, Guda K, Whiteley HE, Rosenberg DW. Preliminary analysis of azoxymethane induced colon tumors in inbred mice commonly used as transgenic/knockout progenitors. Int J Oncol. 2003;22:145–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bissahoyo A, Pearsall RS, Hanlon K, Amann V, Hicks D, Godfrey VL, Threadgill DW. Azoxymethane is a genetic background-dependent colorectal tumor initiator and promoter in mice: effects of dose, route, and diet. Toxicol Sci. 2005;88:340–345. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta AK, Pretlow TP, Schoen RE. Aberrant crypt foci: what we know and what we need to know. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:526–533. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Papanikolaou A, Wang QS, Papanikolaou D, Whiteley HE, Rosenberg DW. Sequential and morphological analyses of aberrant crypt foci formation in mice of differing susceptibility to azoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1567–1572. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sohn OS, Fiala ES, Requeijo SP, Weisburger JH, Gonzalez FJ. Differential effects of CYP2E1 status on the metabolic activation of the colon carcinogens azoxymethane and methylazoxymethanol. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8435–8440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carroll RE, Goodlad RA, Poole AJ, Tyner AL, Robey RB, Swanson SM, Unterman TG. Reduced susceptibility to azoxymethane-induced aberrant crypt foci formation and colon cancer in growth hormone deficient rats. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2009;19:447–456. doi: 10.1016/j.ghir.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen J, Huang XF. The signal pathways in azoxymethane-induced colon cancer and preventive implications. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:1313–1317. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.14.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cohen G, Mustafi R, Chumsangsri A, Little N, Nathanson J, Cerda S, Jagadeeswaran S, Dougherty U, Joseph L, Hart J, Yerian L, Tretiakova M, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor signaling is up-regulated in human colonic aberrant crypt foci. Cancer Res. 2006;66:5656–5664. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sinicrope FA, Gill S. Role of cyclooxygenase-2 in colorectal cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2004;23:63–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1025863029529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mishra L, Shetty K, Tang Y, Stuart A, Byers SW. The role of TGF-beta and Wnt signaling in gastrointestinal stem cells and cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:5775–5789. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Taketo MM. Wnt signaling and gastrointestinal tumorigenesis in mouse models. Oncogene. 2006;25:7522–7530. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grivennikov SI, Karin M. Dangerous liaisons: STAT3 and NF-kappaB collaboration and crosstalk in cancer. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 21:11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2009.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dougherty U, Sehdev A, Cerda S, Mustafi R, Little N, Yuan W, Jagadeeswaran S, Chumsangsri A, Delgado J, Tretiakova M, Joseph L, Hart J, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor controls flat dysplastic aberrant crypt foci development and colon cancer progression in the rat azoxymethane model. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2253–2262. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Biswas S, Chytil A, Washington K, Romero-Gallo J, Gorska AE, Wirth PS, Gautam S, Moses HL, Grady WM. Transforming growth factor beta receptor type II inactivation promotes the establishment and progression of colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2004;64:4687–4692. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishikawa TO, Herschman HR. Tumor formation in a mouse model of colitis-associated colon cancer does not require COX-1 or COX-2 expression. Carcinogenesis. 31:729–736. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgq002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roberts RB, Min L, Washington MK, Olsen SJ, Settle SH, Coffey RJ, Threadgill DW. Importance of epidermal growth factor receptor signaling in establishment of adenomas and maintenance of carcinomas during intestinal tumorigenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:1521–1526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032678499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao D, Zhan Y, Zeng H, Koon HW, Moyer MP, Pothoulakis C. Neurotensin stimulates expression of early growth response gene-1 and EGF receptor through MAP kinase activation in human colonic epithelial cells. Int J Cancer. 2007;120:1652–1656. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lemaire I. Neurotensin enhances IL-1 production by activated alveolar macrophages. J Immunol. 1988;140:2983–2988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waugh DJ, Wilson C. The interleukin-8 pathway in cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:6735–6741. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chao C, Tallman ML, Ives KL, Townsend CM, Jr, Hellmich MR. Gastrointestinal hormone receptors in primary human colorectal carcinomas. J Surg Res. 2005;129:313–321. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2005.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang X, Jackson LN, Johnson SM, Wang Q, Evers BM. Suppression of neurotensin receptor type 1 expression and function by histone deacetylase inhibitors in human colorectal cancers. Mol Cancer Ther. 9:2389–2398. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meira LB, Bugni JM, Green SL, Lee CW, Pang B, Borenshtein D, Rickman BH, Rogers AB, Moroski-Erkul CA, McFaline JL, Schauer DB, Dedon PC, et al. DNA damage induced by chronic inflammation contributes to colon carcinogenesis in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008 doi: 10.1172/JCI35073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. H&E stained colon sections from control and DSS treated mice were scored histopathologically for dysplasia (A), extent of epithelial injury (B), and extent of inflammation (C). Mid-colon tissue homogenates were assayed for myeloperoxidase activity (D).