Abstract

In the present work the binding of inhibitor TMC114 (darunavir) to wild type (WT), single (I50V) as well as double (I50L/A71V) mutant HIV-proteases (HIV-pr) was investigated with all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations as well as molecular mechanic-Poisson Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA) calculation. For both the apo and complexed HIV-pr, many intriguing effects due to double mutant, I50L/A71V, are observed. For example, the flap-flap distance and the distance from the active site to the flap residues in the apo I50L/A71V-HIV-pr are smaller than those of WT- and I50V-HIV-pr, probably making the active site smaller in volume and closer movement of flaps. For the complexed HIV-pr with TMC114, the double mutant I50L/A71V shows a less curling of the flap tips and less flexibility than WT and the single mutant I50V. As for the other previous studies, the present results also show that the single mutant I50V decreases the binding affinity of I50V-HIV-pr to TMC, resulting in a drug resistance; whereas the double mutant I50L/A71V increases the binding affinity, and as a result of the stronger binding the I50L/A71V may be well adapted by the TMC114. The energy decomposition analysis suggests that the increase of the binding for the double mutant I50L/A71V-HIV-pr can be mainly attributed to the increase in electrostatic energy by −5.52 kacl/mol and van der Waals by −0.42 kcal/mol, which are cancelled out in part by the increase of polar solvation energy of 1.99 kcal/mol. The I50L/A71V mutant directly increases the binding affinity by approximately −0.88 (Ile50 to Leu50) and −0.90 (Ile50’ to Leu50’) kcal/mol, accounting 45% for the total gain of the binding affinity. Besides the direct effects from the residues Leu50 and Leu50’, the residue Gly49’ increases the binding affinity of I50L/A71V-HIV-pr to the inhibitor by −0.74 kcal/mol, to which the electrostatic interaction of Leu50’s backbone contributes by −1.23kcal/mol. Another two residues Ile84 and Ile47’ also increase the binding affinity by −0.22 and −0.29kcal/mol, respectively, which can be mainly attributed to van der waals terms (ΔTvdw: −0.21 and −0.39 kcal/mol).

Keywords: Single and double mutant HIV-1 proteases, Inhibitor TMC114, Drug resistance, MM-PBSA, Molecular dynamics simulation

1. Introduction

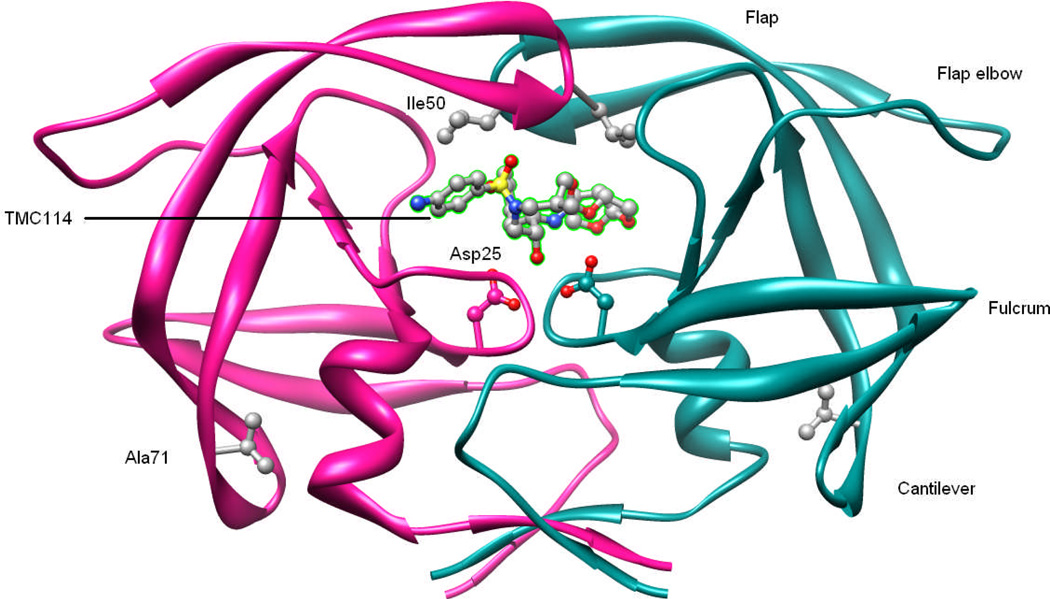

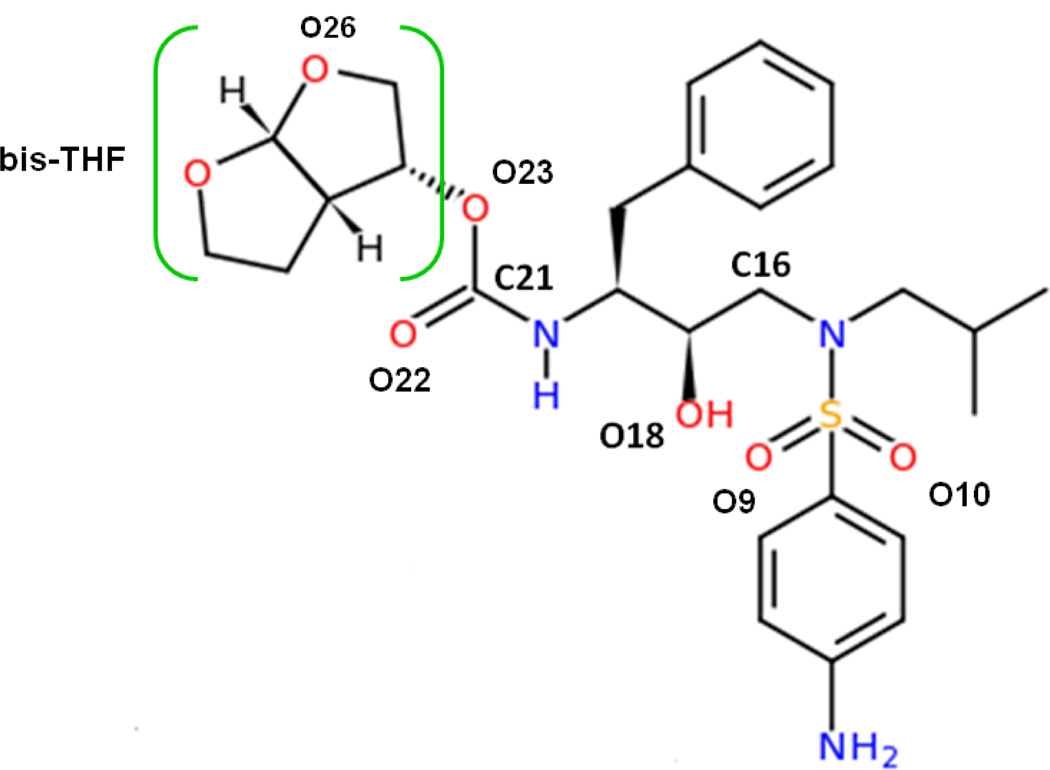

Protease inhibitors (PIs) play very important role in combating AIDS through deactivating HIV-1 protease (HIV-pr, shown in Figure 1) that acts at the late stage of infection by cleaving the Gag and Gag–Pol polyproteins to yield mature infectious virions.1 However, their effectiveness were greatly affected by variant mutations of the HIV-pr. Mutations causing drug resistance have been therefore one of the biggest challenges for the treatment of HIV replication.2 TMC114, a non-peptidic compound terminated by bis-tetrahydrofuran (bis-THF) moiety shown in Figure 2, is an extremely potent PI for treatment of drug resistant HIV strains including many subtypes.3 It is speculated that the bis-THF oxygen atoms may form hydrogen bonds with the backbone N-H groups of residues Asp30 (Asp30’) of HIV-pr, enhancing the binding of the PI with HIV-pr.3 As for other approved PIs, several HIV-pr mutants were demonstrated to have drug resistance over the TMC114, like D30N and I50V, whereas L90M is well adapted by the TMC114.4–5 The drug resistance mechanism of such mutants was explored at the molecular level with all-atomistic MD simulation combined with molecular mechanics-Poisson/Boltzmann surface area (MM-PBSA) for the binding energies of TMC114 to D30N and I50V mutants.6 It was found that loss of H-bonds between Asp30 and TMC114 drives the drug resistance in D30N, whereas for I50V it is the increased polar solvation energies for the two residues Asp30’ and Val50’.6 The resistance of the inhibitor GRL-98065, an analog of TMC114 just aniline group replaced by a 1,3-benzodioxole group, to mutants I50V and V82A was attributed to a higher entropic contribution than in the wild type (WT) HIV-pr, and the reduced van der Waals may be responsible to the drug resistance of I84V to GRL-98065.6 There have been several other studies on ligand binding interactions and multi-drug resistance in HIV-pr using MM-PBSA method.7–13

Figure 1.

Structure of HIV-pr complexed with TMC114. The HIV-pr is shown in magenta and cyan ribbons for chain-A and chain-B, respectively. Catalytic residues (Asp25 and Asp25’), and the sites of mutation are indicated by ball and stick representation for Ile50 and Ala71. TMC114 is bound in the active site and is labeled. Important regions of the HIV-pr like flap, flap elbow, fulcrum and cantilever are also shown.

Figure 2.

Molecular structure of the inhibitor TMC114. The moiety bis-THF is labeled with a square bracket in color green. Important atoms like O9, O10, O18 and O22 which are involved in the interactions between the inhibitor and protein are also labeled in black bold letters.

Mutation I50V and the double mutation I50L/A71V are considered as two of the most key residue mutations of the HIV-pr drug resistance to inhibitors in clinical use. However, although both of the residues are present in two critical locations and their effect on a few other PIs were previously discussed,14 for the double mutation I50L/A71V there is little information regarding its importance in drug resistance mechanism for the TMC114. Mutation I50L is a signature mutation for atazanavir (ATV) resistance, and has increased susceptibility to other inhibitors with the presence of other primary and secondary resistance mutations.15 A71V mutation in the cantilever region is distant from active site, and has a profound effect on the binding of ligand to the active site through H-bond propagation from the site of mutation.16 With isothermal titration calorimetry, Yanchunas et al showed that protease enzymes containing I50L/A71V exhibit increased binding to seven inhibitors relative to wild-type HIV-pr, being parallel to the increased susceptibility of recombinant viruses with this mutation.14,17 Thus, the double mutation (I50L/A71V) effect of the two important residues Ile50 and Ala71 on HIV-pr structure and its difference from the single mutation (I50V) influence, prompt us to investigate the changes in binding affinity of the inhibitor TMC114 to the protease.

In the present study, to facilitate the investigation of drug resistance mechanism and to obtain information about the binding of TMC114 to the WT and mutant HIV-pr, MD simulations have been performed first for three inhibitor-free (apo) WT, I50V and I50L/A71V HIV-proteases as well as the three inhibitor-bound HIV-proteases. The major objective for the MD simulation is to explore the similarity and distinction for the dynamic behaviors of the three apo and bound proteins. For both the apo and complexed HIV-pr, the analysis indicates many intriguing effects due to double mutant, I50L/A71V. The flap curling and opening events in I50L/A71V-HIV-pr are more stable than WT and I50V mutant. The average flap tip – active site, flap –flap distances and curling behavior of the TriCa angles suggest a closer movement of flaps in the double mutant as compared to WT and I50V, probably making the active site volume smaller. The most distinct motion for the HIV-pr complex was the movement of the side chain of catalytic Asp25 about the inhibitor. There is a flip-flop of the interaction between the catalytic Asp25 OD1/OD2 atoms and O18 of TMC114, which may be due to the effect of the mutation A71V from the double mutant, where the change from Ala to Val modifies the H-bonding pattern between the four anti-parallel β-sheets connecting Asp25 site to Val71. The change in H-bonding pattern induces the rearrangement of β-sheets and finally affects the dynamics of Asp25 residues.

To quantitatively describe the influence of the double mutant, the MM-PBSA method was then used to calculate the absolute binding free energies,18–25 which were further decomposed to a per-residue basis.26 The primary objectives for the binding energy calculation are to gain an insight into whether the double mutant I50L/A71V provides drug resistance to TMC114, and then to analyze the detailed interaction mechanism at a molecular level. As for the other previous studies, the present results also show that the single mutant I50V decreases the binding affinity of I50V-HIV-pr to TMC, resulting in a drug resistance. It is interesting to note that the double mutant I50L/A71V increases the binding affinity, and as a result of the stronger binding the I50L/A71V may be well adapted by the TMC114.

2. Theoretical Methodology

2. 1. System Setups

The crystal structures of the WT and mutant HIV-pr complexed with TMC-114 were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). 1T3R 27 for the WT HIV-pr, 2F8G 4 for the I50V mutant, and 3EM628 for the I50V/A71V double mutant HIV-pr. There are alternate conformations in 3EM6 and 2F8G: conformation A and B, owing to the inconspicuous electron density of few residues in the HIV-pr, only conformation A was selected for the starting model. The apo variants of WT and mutant proteases were obtained by deletion of the inhibitors from the active site. Due to the importance of the protonation of Asp25/Asp25′ in the HIV-pr, the monoprotonated HIV-pr was considered and a proton is added to the oxygen atom OD2 in Asp25’ in chain B.29–30 Charges of TMC114 were calculated using the restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) procedure31 at the HF/6–31G* after minimizing the molecule at the AM1 semi-empirical level.32 GAFF force field33 parameters and the RESP partial charges are assigned using the Antechamber module in AMBER10 package.34 All missing hydrogen atoms were added using the LEaP module. The ff99SB 35 force field with TIP3P36 water models was used for all the simulations. The system was solvated with the TIP3P waters in the truncated octahedron periodic box of size 89.2 × 84.8 × 96.3Å3 containing more than 9,000 water molecules. The box size was chosen according to the approximate shape of each complex. A cutoff of 10 Å was used along the three axes from any solute atoms of the system. An appropriate number of Cl− counter ions were added to neutralize the net positive charge on the system. A default cutoff of 8.0 Å in AMBER10 was used for Lennard-Jones interactions, and the long-range electrostatic interactions were calculated with the particle mesh ewald (PME) method.37 Constant temperature and pressure conditions in the simulation were achieved by coupling the system to a Berendsen's thermostat and barostat.38 The SHAKE39 algorithm was used to constrain all bonds involving hydrogens.

2.2 Molecular dynamics simulations

Structures were optimized through Sybyl before the minimization to remove any bad contacts in the structure. The system was then minimized in four phases. In the first phase, the system was minimized giving restraints (30kcal/mol/Å2) to all heavy atoms of protein and ligand for 10000 steps with subsequent second phase minimization of the all backbone atoms and C-alpha atoms, respectively, for 10000 steps each. Then the system was heated to 300K with a gap of 50K over 10 ps with a 1 fs time step. In subsequent minimization of third phase, the force constant was reduced by 10 kcal/mol/Å2 in each step to reach the unrestrained structure in three steps of 10000 steps each. Finally the whole system was minimized again for 10000 steps without any constraint at the NVT ensemble. The system was equilibrated at the NVT ensemble for 100ps and then switched over to the NPT ensemble equilibrating without any restraints for another 120 ps. The convergence of energies, temperature, pressure and global RMSD was used to verify the stability of the systems. All the apo and complexed trajectories were run for 20 ns. The time step for MD production run was 1 fs. The 20 ns trajectories were used to calculate the average structure for all the systems. All the six apo and complexed MD simulations were performed with AMBER 1034 at the Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center on SGI Altix Cobalt system at NCSA, requesting sixteen 8-core nodes, and on local Dell HPCC machines. The simulation time is approximately 1200 CPU hours of single-core processor.

2.3 MM-PBSA calculations

The binding free energies were calculated using the MM-PBSA method implemented in AMBER 10.34 For each complex, a total number of 50 snapshots were taken from the last 2 ns on the MD trajectory with an interval of 40 ps. The MM-PBSA method and nmode module in Amber10 were applied to calculate the binding free energy of the inhibitor TMC114 to the protease. The MM-PBSA method can be summarized as:

| (1) |

where ΔGb is the binding free energy in solution consisting of the molecular mechanics free energy (ΔEMM) and the conformational entropy effect to binding (−TΔS) in the gas phase, and the solvation free energy (ΔGsol). ΔEMM can be expressed as:

| (2) |

where ΔEvdw and ΔEele correspond to the van der Waals and electrostatic interactions in gas phase, respectively. The solvation free energy (ΔGsol) is further divided into two components:

| (3) |

where ΔGpol and ΔGnonpol are the polar and non-polar contributions to the solvation free energy, respectively. The ΔGsol is calculated with the PBSA module of AMBER suite of program. In our calculation, the dielectric constant is set to 1.0 inside the solute and 80.0 for the solvent. The nonpolar contribution of the solvation free energy is calculated as a function of the solvent-accessible surface area (SAS), as follows:

| (4) |

where, SAS was estimated using the MSMS program, with a solvent probe radius of 1.4 Å. The values of empirical constants γ and β were set to 0.00542 kcal/(molÅ2) and 0.92 kcal/mol, respectively.

The contributions of entropy (TΔS) to binding free energy arise from changes of the translational, rotational and vibrational degrees of freedom, as follows:

| (5) |

TΔS is generally calculated using classical statistical thermodynamics and normal mode analysis. Due to entropy calculations for large systems being extremely time consuming, we applied only 40 snapshots taken at an interval of 50 ps from the final 2000 ps of the MD simulation for the entropy contribution. Each snapshot was minimized with a distance dependant dielectric function 4Rij (the distance between two atoms) until the root-mean-square of the energy gradient was lower than 10−4 kcal/mol/Å2.

2.4 Residue-inhibitor interaction decomposition

On account of the huge demand of computational resources for PB calculations, the interaction between TMC114 and each HIV-pr residue was computed using the MM-GBSA decomposition process applied in the mm_pbsa module in AMBER10. The binding interaction of each inhibitor-residue pair includes four terms: van der Waals (ΔEvdw) contribution and electrostatic (ΔEele) contribution in the gas phase, polar solvation (ΔGpol) contribution, and non-polar solvation (ΔGnopol) contribution.

| (6) |

The polar contribution (ΔGpol) to solvation energy was calculated by using the GB (Generalized Born) module and the parameters for the GB calculation were developed by Onufriev et al.40 All energy components in Equation (6) were calculated using 50 snapshots from the last 2.0 ns of the MD simulation. The hydrogen bonds (H-bonds) were analyzed using the ptraj module of AMBER program. Formation of the H-bonds depends on the distance and angle cutoff as follows: (a) distance between proton donor and acceptor atoms were ≤ 3.5 Å, and (b) the angle between donor-H…acceptor was ≥ 120°. Graphic visualization and presentation of protein structures were done using PYMOL.41

3. Results and Discussions

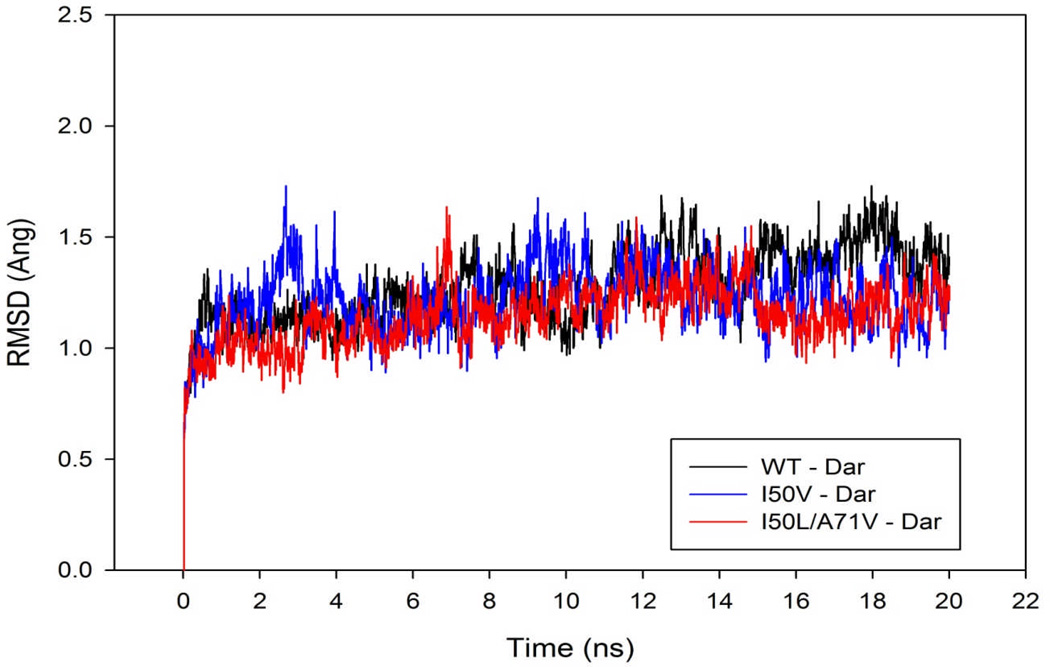

3.1. Stability of trajectories from RMSD

Exploring the effect of mutations on the conformational stability of the HIV-pr/TMC114 complexes, RMSD values for the HIV-pr Cα atoms during the 20 ns production phase relative to the initial (minimized and equilibrated) structures were calculated and plotted in Figure 3. The RMSD plots indicate that the conformations of the WT, single mutant (I50V) and double mutant (I50L/A71V) HIV-pr complexes are in good equilibrium. The trajectory of the I50V-HIV/TMC114 complex fluctuates more than other two trajectories at around 3–5 ns, after that it goes parallel to each other. According to the data obtained for the RMSD values of the three complexes, WT complex has a higher mean (1.27 Å) than the I50V mutant (1.22 Å) and I50L/A71V double mutant (1.14 Å), with a respective deviation of 0.16, 0.15 and 0.13 Å. The result signifies that RMSD of all three complexes were similar from the starting structures during the course of simulations with values around 1.0 to 1.7 Å ensuring stable trajectories. Figure S1 in supporting information shows the RMSD plots for all (WT, I50V and I50V/A71V) apo type HIV-pr, and indicates that the conformations for all apo type have also achieved equilibrium. There is no distinct changes/fluctuations in the apo form for all type HIV-pr and were similar from the starting structures during the course of simulations with values around 1.0 to 1.8 Å ensuring stable trajectories.

Figure 3.

Root-mean-square-displacement (RMSD) plot for backbone Cα atoms relative to their initial minimized complex structures as a function of time.

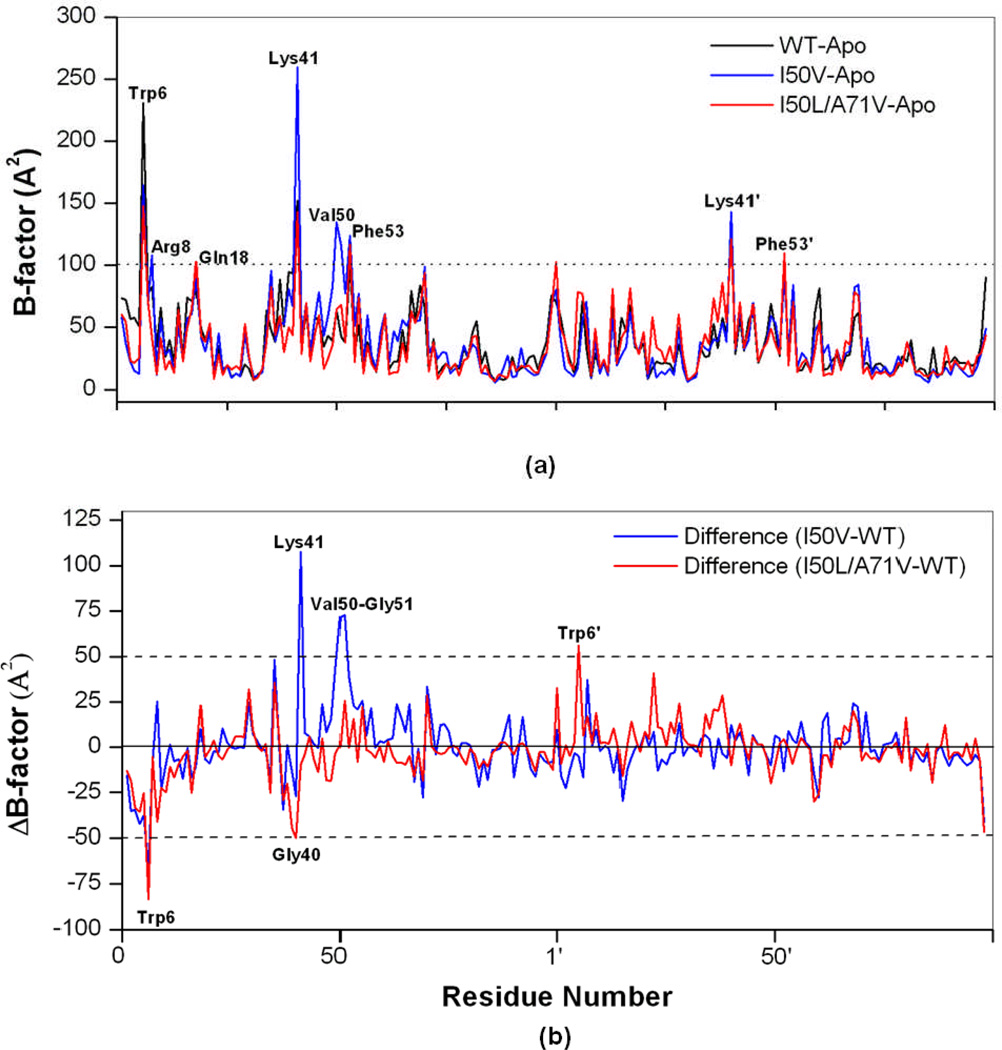

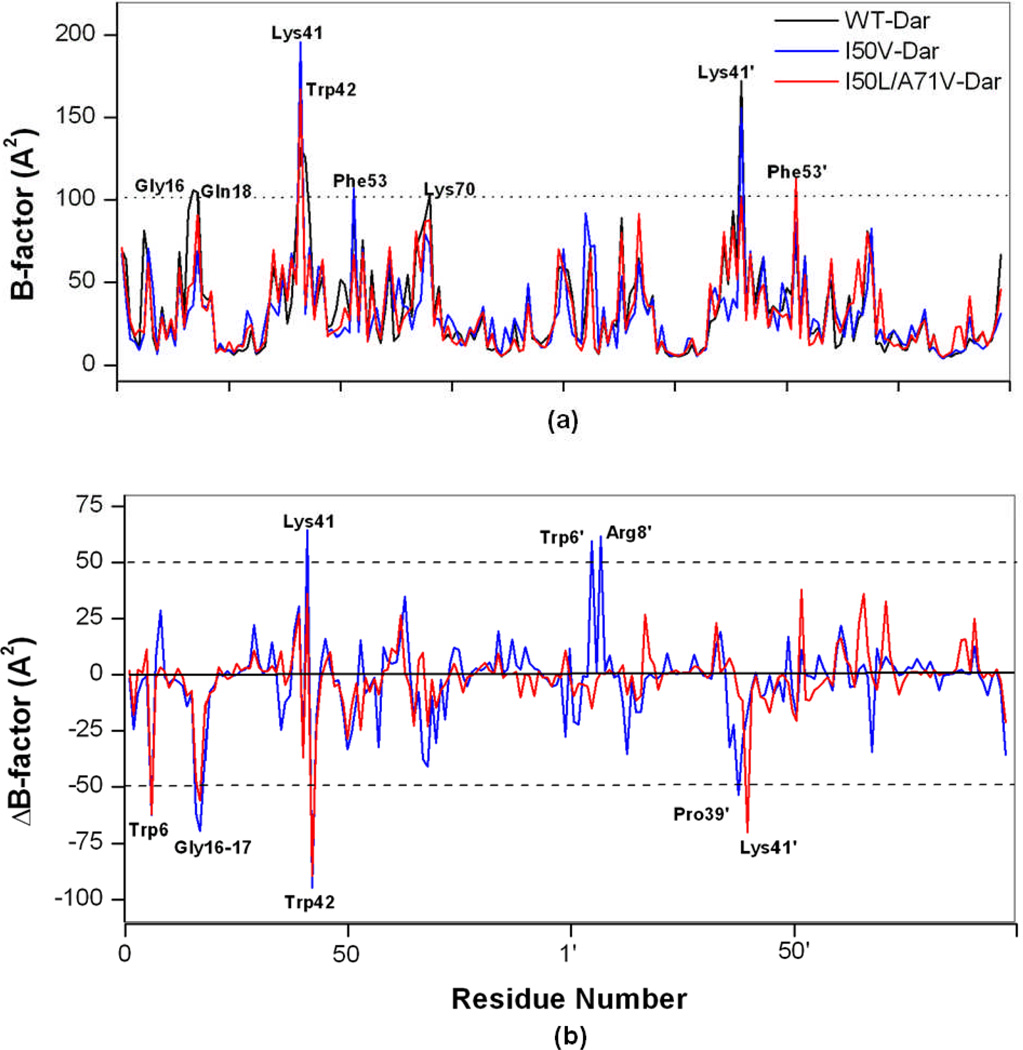

3.2 Comparing the apo proteins from B-factor: WT vs. Mutant

In order to analyze the detailed residual atomic fluctuations, isotropic temperature factor (B-factor) calculation has been performed for the apo HIV-pr structure as illustrated in Figure 4a. For the given HIV-pr, the B-factor difference between chain A and chain B may be due to the monoprotonation of ASP25’ in chain B. The flexibility of the apo-protein in chain-A is greater in case of I50V, particularly in the flap regions. Residue Arg8, contributing to the binding energetic favorably,42 is located in one of the most distinct regions of the protease molecule, i.e. dimer interface. In both chains for I50V-HIV-pr, Arg8 has a higher mobility as compared to WT and I50L/A71V. It is also confirmed from the B-factor values that the fulcrum residues are less affected due to the mutations in the protein backbone. Residues Gly16 and Gly17 in both chains for WT have significant higher mobility than the mutant duo I50V and I50L/A71V.

Figure 4.

(a) B-factor of backbone atoms versus residue number of the WT, I50V and I50L/A71V HIV-pr apo structures and (b) Difference of B-factor values from molecular dynamics (MD) simulation for WT and mutant HIV-pr simulation of the apo protein (mutant B-factor – WT B-factor). The residues with absolute difference larger than 50 Å2 are labeled by two cutoff dashed lines.

A difference of B-factors may provide direct insights into the structural fluctuation of different regions of WT and mutant HIV-pr. The difference in the isotropic temperature factor between the mutants and WT HIV-pr for each residue is shown in Figure 4b. The major changes in B-factor occur between WT and mutant HIV-pr for the residues in the dimer interface region (6, 8 and 6’, 8’), flap elbow of the chain-A (35, 37, 39–41), flap of the chain-A (49–52). The residues with absolute difference larger than 50 Å2 were taken as the most fluctuating residues and are labeled by two cutoff lines as shown in the Figure 4b. It is noted that several other regions exist in which WT and mutant HIV-pr have different B-factors. In summary, by comparison of the B-factors between WT and mutant HIV-pr, a difference in the fluctuation of several amino acids was found, and this especially includes those residues at the flap tips, flap elbows and dimer interface region. Hence, the difference in the B-factors for the above mentioned residues may affect the structural fluctuations of the protein and binding affinity for the substrate/inhibitor, consequently affecting the drug resistance behavior.

3.3 Local Fluctuations for Apo Proteins

Concerning the local structural differences between WT and mutant HIV-pr, the flap movement is particularly important to explore. It is well-known that flap dynamics affects both the inhibitor binding and enzyme catalysis of HIV-pr. Moreover, several mutations affect flap dynamics. For example, L90M and V82F/I84V mutations open the flap a bit more in the mutant than the WT,43–44 whereas M46I mutation makes the flap more closed.45 In order to probe the extent of flap dynamics, usually the distance between the flap tip (Ile50 and Ile50’) and the catalytic Asp residues (Asp25 and Asp25’) was calculated. Estimation of the Ile50-Asp25 or the Ile50’-Asp25’ distance was believed to be more realistic than the measure by monitoring the flap tip-tip (Ile50-Ile50’) distance, because the flap tip-tip distance can be affected by both flap tip curling and flap asymmetry. We have used several of these parameters to enquire the extent of flap motion in the current study.

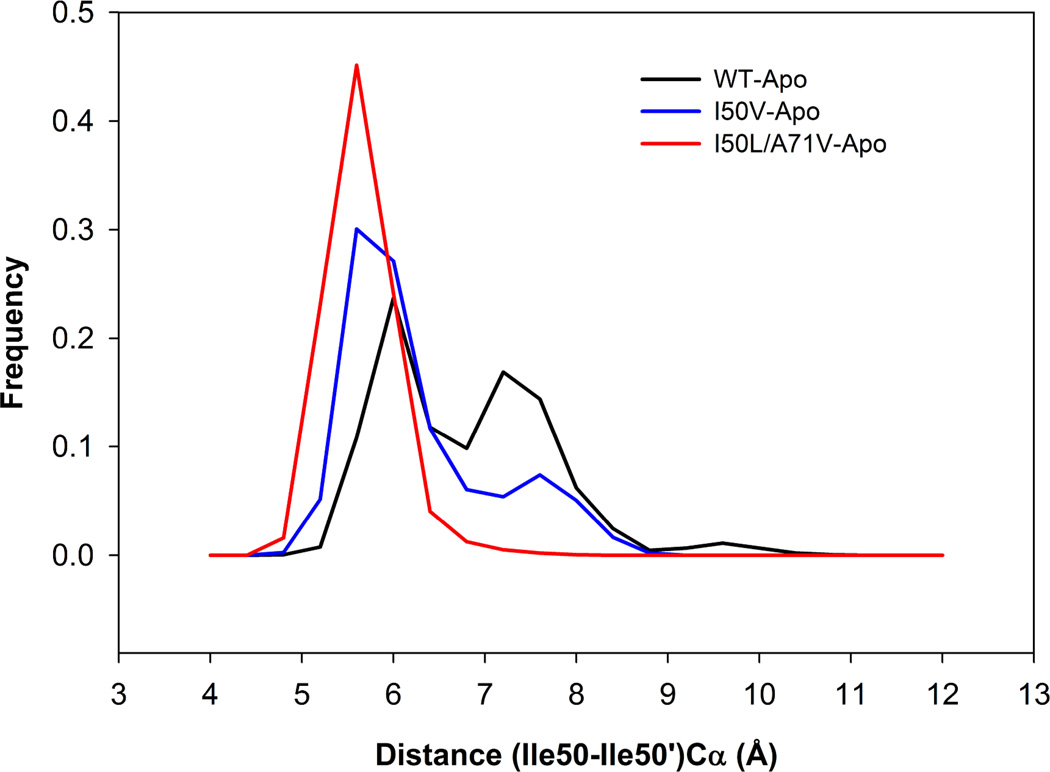

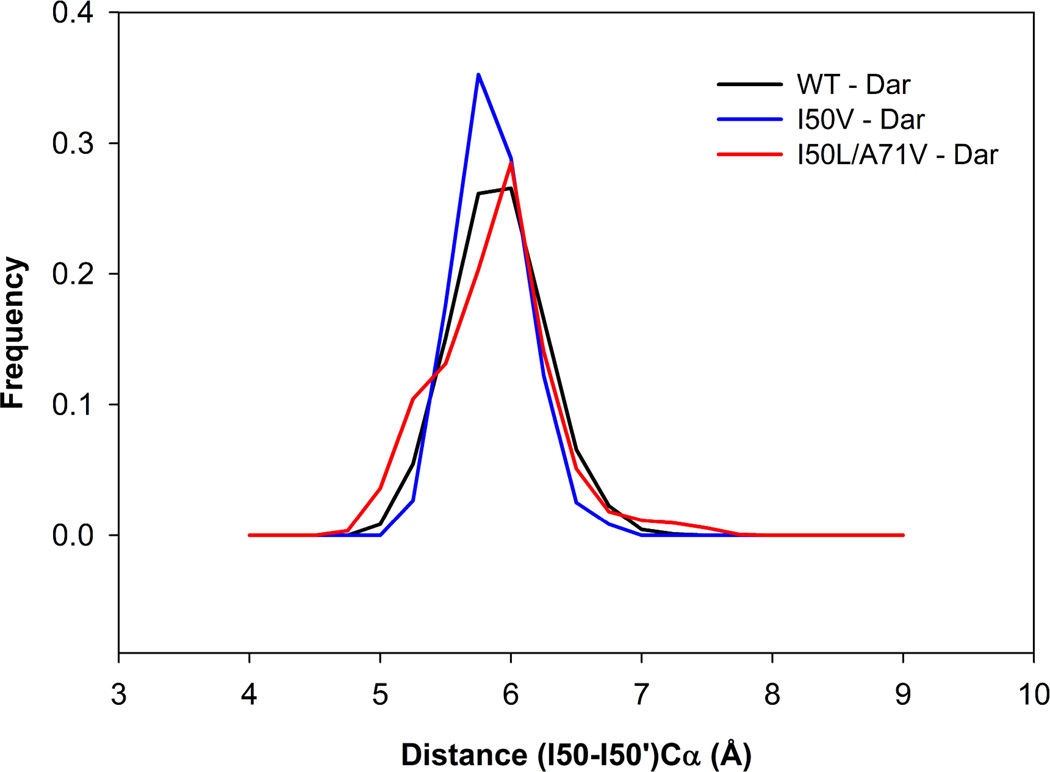

1) Distance between flap-tips (I50Cα-I50’Cα)

The distance between the two Cα atoms of Ile50 and Ile50’ measures the distance between flap tips in both chains. The frequency distribution plot for flap tip - tip distance is shown in Figure 5. It is clearly seen that with respect to (I50-I50’) Cα distance, WT and I50V mutant assembles two different types of structures as compared with the I50L/A71V double mutant. For the double mutant, the distribution has one peak around 6 Å, whereas for WT and I50V mutant the main peak locates around 6 Å, and the other minor around 7–8 Å region. The mean and standard deviation (SD) of WT distribution are 7.0 Å and 0.92 Å, of I50V mutant are 6.45 Å and 0.8 Å and those of double mutant are 5.85 Å and 0.37 Å, respectively. While considerable overlaps exist in the three distributions, the distance between the flap tips were recognized to fluctuate more in the case of WT and I50V than in the double mutant I50L/A71V. Hence, the mean of the double mutant structure is significantly less (1.15 Å) than the WT, suggesting that there is a close movement of flaps in I50L/A71V as compared to WT- and I50V-HIV-pr structures and probably making the active site volume smaller.

Figure 5.

Histogram distributions of Ile50–Ile50’ distance for WT, I50V mutant and I50L/A71V double mutant HIV-pr simulation of the apo protein.

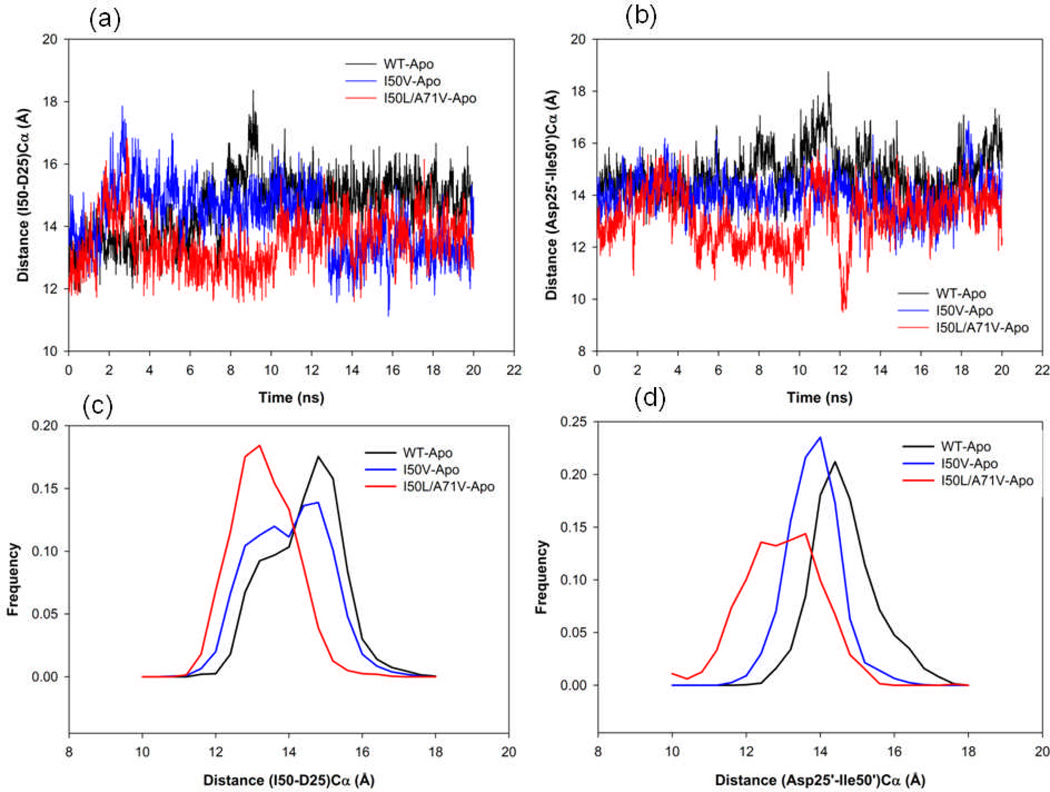

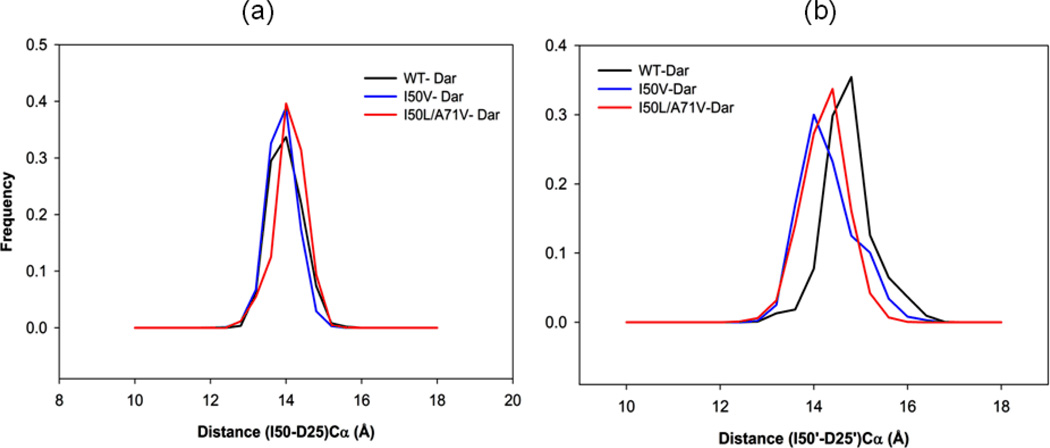

2) Flap tip to active site (Ile50-Asp25) Cα distance

The distance between the flap tips (Ile50Cα and Ile50’Cα) to the catalytic aspartates (Asp25Cα and Asp25’Cα) of the active site was also measured from the simulation. The time series plot and the histogram distributions are shown in Figures 6a–d for chains A and B, respectively. These results reveal that the distances between the flap tip and catalytic site in chains A and B are clearly different for the double mutant I50L/A71V structures with smaller distance values compared to the WT and I50V mutant structures. According to Figure 6a, in chain-A for WT and I50V there is considerable overlapping of the two distributions, whereas for I50L/A71V-HIV-pr the distribution is quite different from those of WT and I50V. The mean and SD of WT (I50V) are 14.62 (14.20) Å and 0.98 (1.04) Å, respectively; whereas for the double mutant I50L/A71V the mean and SD are only 13.51 Å and 0.83 Å, respectively. The mean of the distribution for I50L/A71V is smaller by 1.11 Å than WT and 0.69 Å than I50V. Moreover, chain-B (Figure 6b) also displays different conformational sampling for I50L/A71V as compared to WT and I50V. The mean and SD of WT (I50V) are 14.84 (14.02) Å and SD is 0.87 (0.70) Å respectively. Whereas, for the double mutant I50L/A71V the mean and SD are 13.14 Å and 1.04 Å, respectively. Thus, the mean of the distribution for I50L/A71V in chain B differ by ~1.7 Å from WT and ~ 0.9 Å from I50V. The results indicate the smaller distance between the active site to flap residues in I50L/A71V than in WT and I50V. This result also complements with the tip-tip distance that suggests a close movement of flaps in I50L/A71V as compared to WT and I50V structures, probably making the active site smaller in volume. The reduced active site conformations of I50L/A71V due to the flap dynamics behavior may enhance the binding of an inhibitor to the active site region. This may be due to the increase in the van der Waals (vdw) contacts between the inhibitor and protein residues. For the clarification, we have also calculated the binding energy of the complexes, which will be discussed to correlate the present data.

Figure 6.

Variability of (a) the Ile50-Asp25 Cα distances, (b) the Ile50’-Asp25’ Cα distances of the apo WT, I50V mutant and I50L/A71V double mutant HIV-pr. (c) Histogram distributions of Ile50–Asp25 distance; and (d) histogram distributions of Ile50’ –Asp25’ distance for WT and all mutant HIV-pr simulation of the apo protein.

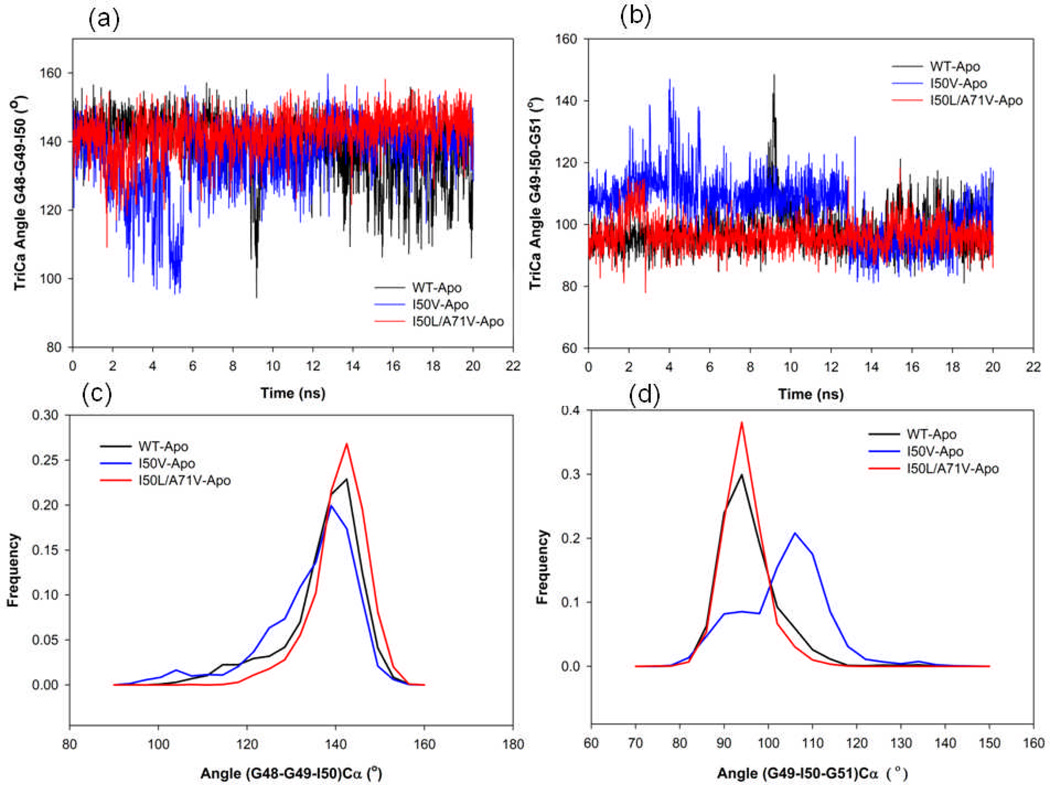

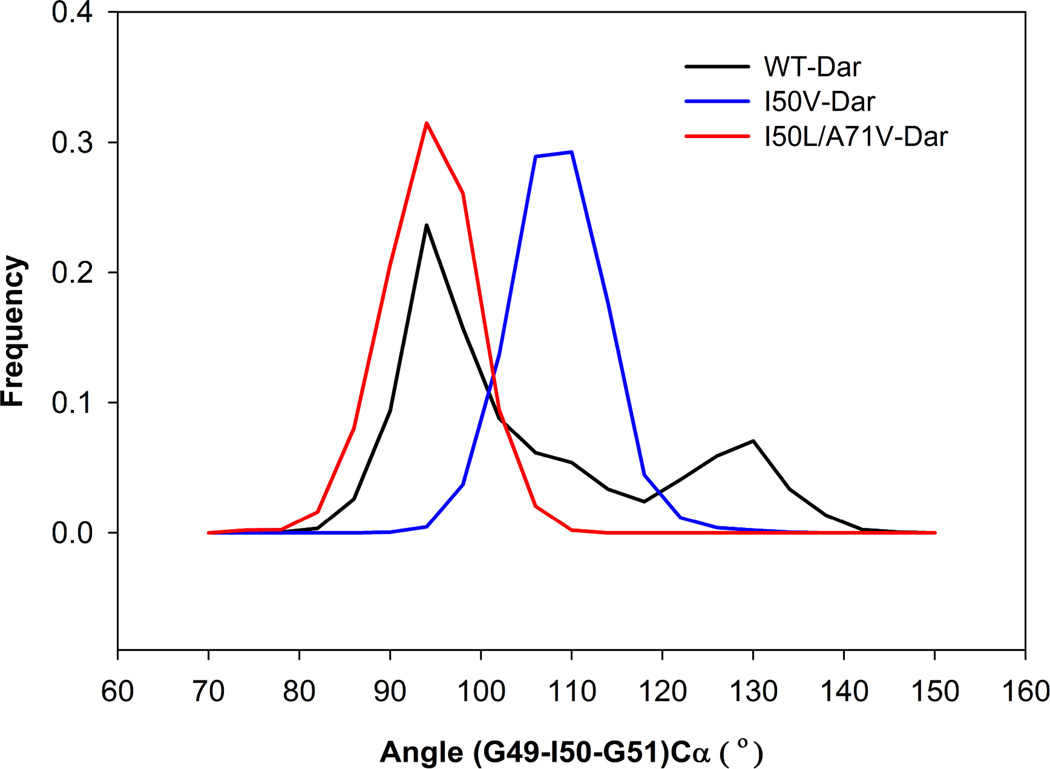

3) Analysis of the TriCa Angle

In order to explain the flap dynamics behavior of the protein, Schiffer et al. introduced the term “flap curling” of the TriCa angles involving the residues in the flap tip or nearby region. It is known that the flap curling in and out behavior makes the protein open and closed state, respectively, in order to access the substrate/inhibitor. 46 The simulation study by Rick et al., also explained the flap’s tips curling in prior to the opening event.47 Curling in starts with the large change in the Φ and Ψ torsion values of residues 48–52 and fold back onto themselves to lead a bent L structure. We have used this term of flap curling to explain our observations of the MD studies, two angles (Gly48-Gly49-Ile50) and (Gly49-Ile50-Gly51) for the consideration as TriCa angle in the flap tip region. Figure 7 shows the time series plot for angle Gly48-Gly49-Ile50 Cα atoms, where TriCa angle seems to be more stable for I50L/A71V-HIV-pr than those for the WT- and I50V-HIV-pr. For WT, the trajectory spends more time in the lower values at around 9ns and the period of 14–20ns. However, the I50V mutant spends more time in the lower values in the initial, but eventually overlaps with the WT in the end. Analyzing the frequency distribution plot for the TriCa angle 48-49-50, it was found that the distribution of the angle for WT and I50L/A71V overlaps substantially; however, the I50V distribution shows a difference as compared to the other two. The mean and SD of the TriCa angle Gly48-Gly49-Ile50 are 138.91° and 8.99° for WT distribution, 136.26° and 10.44° for I50V, and 142.59° and 6.13° for I50L/A71V. Hence, the SD of I50V is much higher than the WT and especially than the I50L/A71V, which is an indication of the higher mobility of the flap tips in case of I50V.

Figure 7.

Variability of (a) the Gly48-Gly49-Ile50 TriCa angles, (b) the Gly49-Ile50- Gly51 TriCa angles of the apo WT, I50V mutant and I50L/A71V double mutant HIV-pr. (c) Histogram distributions of Gly48-Gly49-Ile50 TriCa angles; and (d) histogram distributions of Gly49-Ile50- Gly51 TriCa angles for WT and all mutant HIV-pr simulation of the apo protein.

Analyzing the frequency distribution plot (Figure 7d) for the other TriCa angle Gly49-Ile50-Gly51, it can also be found that the I50V mutant structures have different conformations as compared to WT and I50L/A71V. The distribution is almost overlapped for WT and I50L/A71V and is clearly different from that of I50V mutant. The mean and SD of the TriCa angle for WT (I50L/A71V) distribution are 97.65° (96.55) and SD is 6.85° (4.81), respectively, whereas for the single mutant I50V the mean and SD are 105.58° and 9.62°. Therefore the mean of the two distributions of WT and I50L/A71V differ by ~8° and ~9° from that of I50V mutant with wider value coverage for I50V. The time series plot (Figure 7b) also shows the higher fluctuations of I50V structures as compared to WT and I50L/A71V. Thus, finally it was noted that the I50V simulation samples different structures as compared to the WT and double mutant with respect to the flap tips mobility and curling, which is confirmed by the higher SD of both TriCa angles in the I50V-HIV-pr.

3.4 Comparing the complexed proteins from B-factor: WT vs. Mutant

To get an insight to the detailed residual atomic fluctuations, isotropic temperature B-factor calculation has also been performed for the complexed HIV-pr structure as illustrated in Figure 8a. Compared with Figure 4a, the flexibility of the apo protein is higher than that of the inhibitor bound protein, especially in the flap tip and flap elbow regions. This finding can simply be clarified in terms of binding between protease and inhibitor leading to the rigidity of the HIV-pr-TMC114 complex. This result also correlates well with the work reported by Zhu et al., where they observed the tight interaction between the fullerene-based inhibitor and the flaps leads to the closing of flexible flaps.48

Figure 8.

(a) B-factor of backbone atoms versus residue number of the WT, I50V and I50L/A71V HIV-pr –TMC114 complexed structures and (b) Difference of B-factor values from molecular dynamics (MD) simulation for WT and mutant HIV-pr simulation of the complexed protein (mutant B-factor – WT B-factor). The residues with absolute difference larger than 50 Å2 are labeled by two cutoff dashed lines.

Overall, the three structure share similar B-factor distributions with a few exceptions. The average B-factor per residue in the flap and active site binding region for the WT-, I50V- and I50L/A71V-HIV-pr/TMC114 complexes are 31.03, 29.11 and 28.08 Å2, respectively. The relatively smaller B-factor of the double mutant I50L/A71V-complex may be explained by the relatively less conformational fluctuations and decreased flexibility. The decreased flexibility in the inhibitor-binding site leads to the decrease in Km, i.e. an increase in the affinity of the enzyme for the inhibitor and stronger binding.49 Thus, the lowest flexibility of I50L/A71V implies that the I50L/A71V-HIV-pr may have the highest binding affinity to TMC114 and tends to have the least drug resistance behavior.

All the three complexes show similar trends of dynamic features. Regions around catalytic Asp25 and Asp25’ shows a rigid behavior, which is in line with the experimental 50 and theoretical 10,51 investigations. It was observed that, four regions around 18 (18’), 41 (41’), 53 (53’) and 70 (70’) show the highest dynamic fluctuations. The flap elbow region containing the residue Lys41(41’) shows the highest flexibility. This also agrees with the study of Ishima et al.,52 where the authors observed these regions of highest flexibility based on the differences in the experimental crystal structures in combination with the MD results. The difference of temperature factors (B-factor) of the protein in its complexed form is shown in Figure 8b. The residues with absolute difference larger than 50 Å2 were taken as the significant fluctuating residues and are labeled by two cutoff lines as shown in the figure. It can be seen that compared with the apo protein in Figure 4, the difference between WT and mutant is reduced for most of the residues. However, there are still significant differences for the residues Trp6, Gly16–17 (fulcrum of chain A), 41–42 (flap elbow of chain A), Trp6’, Arg8’, Pro39’-Lys41’ (flap elbow of chain-B).

3.5 Local Fluctuations for Complexed Structure

We have then examined several key local fluctuations of the complexes of the inhibitor with WT and mutant HIV-pr. These include (1) Asp25(25’)–Ile50(50’), (2) Ile50–Ile50’ distances and (3) TriCa angle in flap region, which indicate flap dynamics and flap-active site movements, and (4 and 5) Asp25(25’)–inhibitor distance, which will be an indicator of the protein–ligand motion.

1) Flap tip to Active site distances

The Asp25(Asp25’)-Ile50(Ile50’) distances were calculated from the MD trajectories and the observed results were compared with those of apo proteins. It was found that for chain-A the distribution was much narrower compared with the apo proteins. Moreover, the distributions for WT-, I50V- and I50L/A71V-HIV-pr/TMC114 complexes have significant overlap (Figure 9a). The mean for flap tip-active site residue are 14.19, 14.09 and 14.30 and the SD values are 0.41, 0.37, and 0.41 for WT-, I50V- and I50L/A71V-HIV-pr/TMC114, respectively. This indicates that in the inhibitor-bound state, the distance between the flap tips and the active site did not differ significantly on mutation for chain-A. For chain-B, there is a substantial difference between the distributions as compared with chain-A (Figure 9b). The mean and SD of I50V (I50L/A71V) are14.49 (14.43) Å and 0.58 (0.47) Å, respectively; while for the WT, the mean and SD are only 14.94 Å and 0.53 Å, respectively. Therefore the mean of the distribution for WT differ by approximately 0.5 Å from I50L/A71V and I50V. In general for all proteases (WT, I50V and I50L/A71V) the average flap tip-active site distance in chain-B is longer than that of chain-A.

Figure 9.

Histogram distributions of (a) Ile50–Asp25 distance and (b) Ile50’-Asp25’ distance for WT, I50V mutant and I50L/A71V double mutant HIV-pr simulation of the TMC114 complexed protein.

2) Flap tip–flap tip distances

To explore the relative motion of the flap tips, the Ile50-Ile50’ distance was examined. The difference between the complexed WT, I50V and I50L/A71V HIV-pr was found to be less and narrower than that of the apo HIV-pr (Figure 10). Although the Ile50-Ile50’ distances are similar to each other in the complexed HIV-prs, as shown above the differences do exist in the Asp25’-Ile50’ distances, which shows the different behavior of the two chains of a homo-dimeric protein like HIV-pr. This result is quite similar to the earlier study on JE-2147 bound I47V mutant. 53

Figure 10.

Histogram distributions of Ile50–Ile50’ distance for WT, I50V mutant and I50L/A71V double mutant HIV-pr simulation of the TMC114 complexed proteins.

3) Analysis of the TriCa (Gly49-Ile50-Gly51) Cα Angle

The flap dynamics of the inhibitor bound proteases can be further analyzed by the TriCa angles in the flap tip region for all three WT-, I50V- and I50L/A71V-HIV-pr complexes. Looking at the distribution plot for the TriCa angle in Figure 11, we observed that the I50V and I50L/A71V mutant complexes have a single peak around ~110° and ~95°, respectively; while the WT has two peaks: the main peak at around 95° and ~130° is the other one. The distribution is quite different as compared to the apo structures, where WT and I50L/A71V mutant partially overlapped and is clearly different from I50V mutant (Figure 7d). The mean values of the TriCa angle for WT (I50V) distribution are 107.19° (110.54°) and SD is 14.33° (5.06°), whereas for the double mutant I50L/A71V the mean and SD are 96.30° and 4.90°. The mean values of WT and I50V are larger than that of double mutant I50L/A71V complex by ~11° and > 14°, which implies the more curling out of the flap tips in WT and I50V than the double mutant. However, the general pattern of the distribution frequency remains the same as of apo protease even in the bounded complexes of the protein. The WT distribution also covers wider values than that of the rest two distributions.

Figure 11.

Histogram distributions of TriCa angle for WT, I50V mutant and I50L/A71V double mutant HIV-pr simulation of the TMC114 complexed proteins.

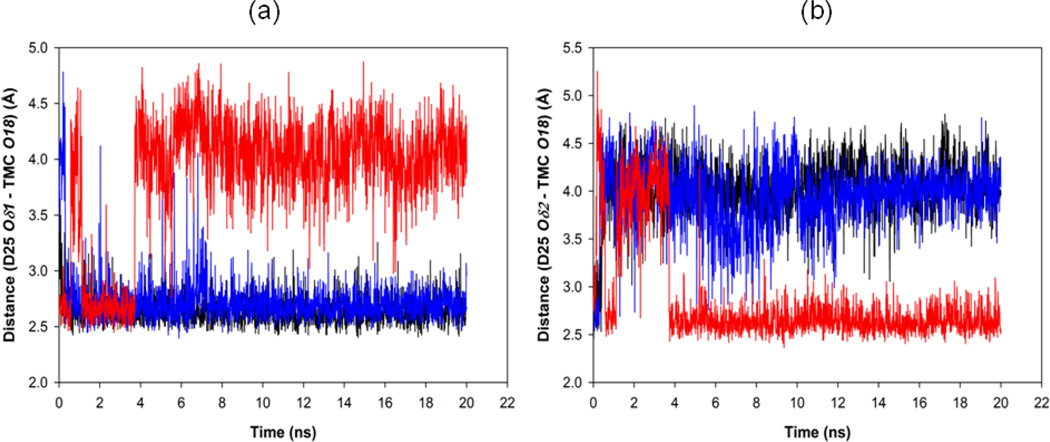

4) Protein (Asp25/Asp25’)-inhibitor (O18) distance

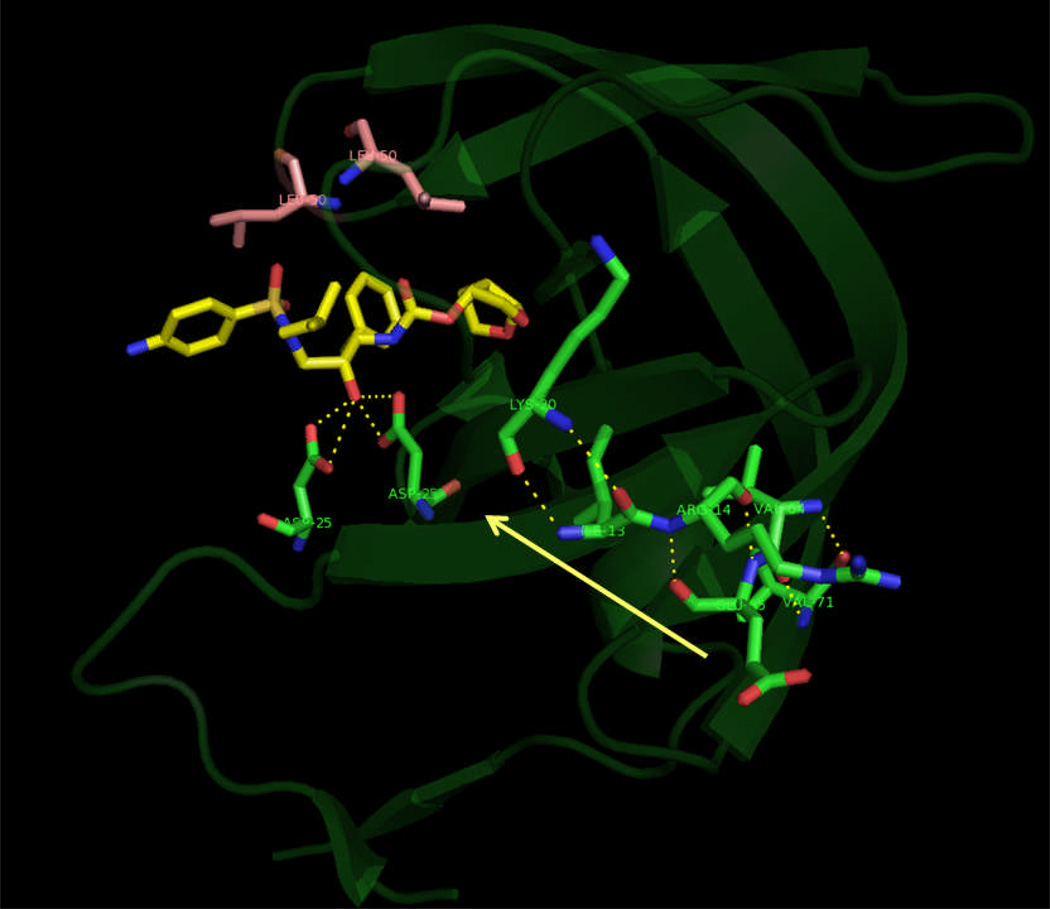

Displacement of the inhibitor to the active site of the protein is coupled with the complex motion of the entire protein. In the crystal structure of the three proteases WT, I50V and I50L/A71V, residues in the flap tip most Ile50/Val50/Leu50 do not have direct polar interactions with the TMC114 in 3 Å regions. However, the protein may bind to the inhibitor via a solvation bridge formed by a water molecule WAT 301. Additionally, the inhibitors are strongly bound to the protease with its OHisostere (O18) to the catalytic Asp25/Asp25’ OD1 and OD2 atoms. To get the protein-inhibitor distance, we have calculated the distances between the catalytic Asp duo (Asp25 and Asp25’) and the O18 of TMC114. From the time series plot of distance between Asp25 OD1-TMC O18 (Figure 12), it was found to be almost always constant for WT (mean of 2.64 Å) and I50V (mean of 2.72 Å) as compared to their initial crystal structure distance of 2.58 Å and 2.59 Å, respectively. However, for the double mutant I50L/A71V, the distance was observed to be quite close between the two atoms from the beginning to up to ~3.7 ns (except around 0.57 ns to 1.1 ns), but eventually around 4 ns the distance goes high up to 4.8 Å. It was found from the crystal structure of double mutant I50L/A71V, that the distance is 2.58 Å, while the obtained MD result has a mean of 3.84 Å. In contrast to the distance from OD1 to O18 of TMC114, Figure 12(b) shows that for double mutant I50L/A71V, the distance from OD2 to O18 eventually tends to be stable at 2.4Å with much shorter average (2.85 Å) than another two cases (4.03 for WT and 3.94 for I50V). It suggests that, there is always a flip-flop of the interaction between the catalytic Asp25 OD1/OD2 atoms and O18 of TMC114. This may be due to the effect of the mutation A71V from the double mutant, where the change from Ala71 to Val modifies the H-bonding pattern between the four anti-parallel β-sheets connecting Asp25 site to Val71. The change in H-bonding pattern induces the rearrangement of β-sheets and finally affects the dynamics of Asp25 residues. The route of propagation of the H-bonding and the change in dynamics can be observed from Figure 13. The mutation of Ala71 to valine requires more space to accommodate valine’s bulkier side chain, which is oriented towards the enzyme interior. These requirements are met by a shift of the 70–71 main chain away from the loop encompassed by residues 92–93.16 The flip-flop interactions justifies that the inhibitor is always bound to either of the OD1/OD2 atoms of Asp25, making the binding stronger in I50L/A71V as compared to WT and I50V.

Figure 12.

Time-series plot for the (a) protein-inhibitor (Asp25 OD1-TMC O18) interaction and (b) protein-inhibitor (Asp25 OD2-TMC O18) interaction for WT (Black line), for I50V (Blue line) and for I50L/A71V (Red line).

Figure 13.

Schematic view of H-bond propagation in the double mutant I50L/A71V and Asp25(25’)-TMC114 flip-flop interaction. Arrow shows the route of propagation.

3.6 Total binding free energies

In order to get insights to the contribution spectrum of binding energy for TMC114, with WT, I50V mutant and I50L/A71V double mutant, absolute binding free energies are calculated for all the complexes using the MM-PBSA method. Contributions of the binding free energies of complexes WT, I50V and I50L/A71V are summarized in the Table 1 and Figure 14. As shown in the figure and table, the binding free energies of WT, I50V and I50L/A71V complexes are −15.33, −10.88 and −18.65 kcal/mol respectively, which suggests that the I50L/A71V double mutant HIV-pr has the strongest binding to the TMC114. The present results for the WT- and I50V-HIV-pr/TMC114 agree well with the available experimental affinities (−15.20, and −11.90 kcal/mol).5,54–55. In line with the previous studies,6 the binding affinity of the mutation I50V to TMC114 decreases by 4.45 kcal/mol compared to the WT complex, resulting in the drug resistance to the inhibitor; however, for the double mutation I50L/A71V complex the binding affinity is increased by 3.32 kcal/mol. The results indicate that the mutant I50V induces weaker binding to TMC114, whereas the double mutant I50V/A71V enhances the binding affinity to TMC114. Although Yanchunas et al showed that the mutant I50L/A71V exhibits increased binding to a number of protease inhibitors (except for atazanavir) relative to wild-type enzymes,14 there is no report on the effect of the double mutant on the HIV-pr’s binding to TMC114. The enhanced binding affinity implies that the double mutant I50L/A71V may be well adapted by the TMC114.

Table 1.

Binding free energy components for the protein-inhibitor complex by using the MM-PBSA method.

| Component[a] | WT | I50V | I50L/A71V | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Std[b] | Mean | Std[b] | Mean | Std[b] | |

| ΔEele | −42.34 | 5.61 | −39.17 | 5.61 | −47.86 | 6.96 |

| ΔEvdw | −63.87 | 3.36 | −62.78 | 4.33 | −64.29 | 3.43 |

| ΔGnp | −6.98 | 0.13 | −6.91 | 0.10 | −7.00 | 0.11 |

| ΔGpb | 71.19 | 3.47 | 70.12 | 4.40 | 73.18 | 5.24 |

| ΔGpol | 28.85 | 4.41 | 30.95 | 3.67 | 25.32 | 4.65 |

| ΔGtotal | −42.00 | 3.69 | −38.74 | 4.17 | −45.98 | 4.21 |

| −TΔS | 26.67 | 4.88 | 27.86 | 6.63 | 27.33 | 7.80 |

| ΔG | −15.33 | 6.11 | −10.88 | 7.83 | −18.65 | 8.86 |

| ΔGexp | −15.20[c] −13.20[d] |

−11.90[d] | ---- | |||

All values are given in kcal/mol.

Component: ΔEele: Electrostatic energy in the gas phase; ΔEvdw: van der Waals energy; ΔGnp: non-polar solvation energy; ΔGpb: polar solvation energy; ΔGpol: ΔEele + ΔGpb; TΔS: Total entropy contribution; ΔGtotal = ΔEele + ΔEvdw + ΔGpb; ΔG = ΔGtotal − TΔS.

Standard error of mean values.

Experimental binding free energies are calculated using Ki, which are obtained from King et al. 55;

from ref.4

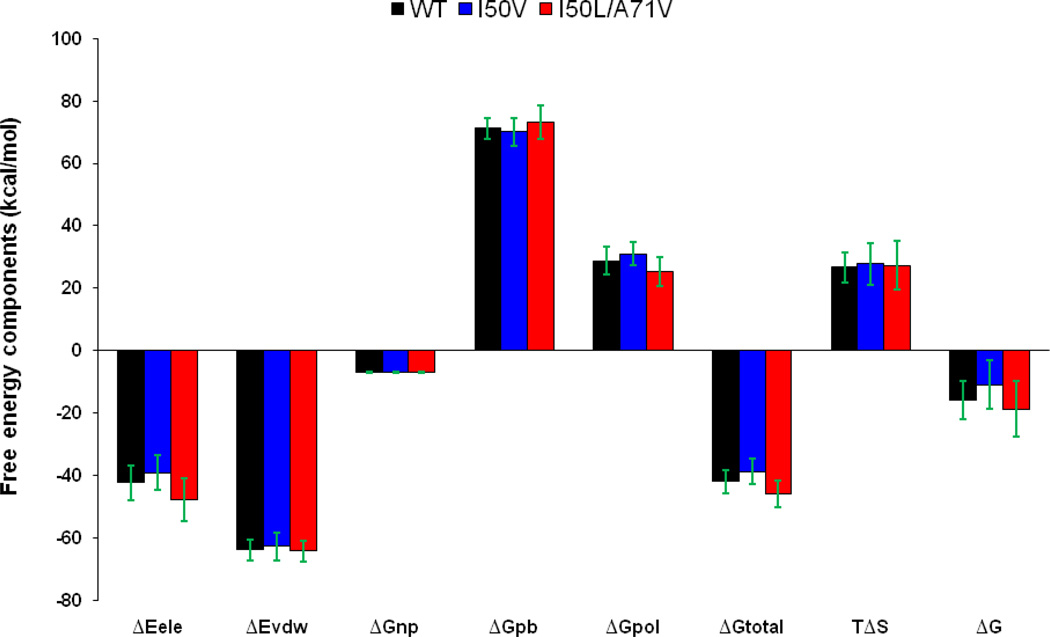

Figure 14.

Energy components (kcal/mol) for the binding of TMC114 to the WT, I50V and I50L/A71V: ΔEele: Electrostatic energy in the gas phase; ΔEvdw: van der Waals energy; ΔGnp: non-polar solvation energy; ΔGpb: polar solvation energy; ΔGpol: ΔEele + ΔGpb; TΔS: Total entropy contribution; ΔGtotal = ΔEele + ΔEvdw + ΔEint + ΔGpb; ΔG = ΔGtotal − TΔS. Error bars in green solid line indicates the difference.

The errors associated with calculated ΔG are reported now on the Table 1. After taking into account the errors, the results in Table 1 still remain the same sequence as excluding the errors. As shown in Table 1, the experimental binding affinity difference between WT and I50V-HIV was 1.3–3.30 kcal/mol, which was determined to induce rather different performance to the TMC. The present results show that the binding affinity of the double mutant I50L/A71V is different from that of WT by −3.32 kcal/mol (−0.6 kcal/mol after taking error bars), and from that of the I50V by −7.8 kcal/mol (−6.7 kcal/mol after error bars), which will lead to different performance to the TMC114.

Comparisons of the free energy components between WT complex and the single and double mutant complexes are carried out to explicate their interaction mechanism. In accordance with the energy components of the binding free energy in Table 1 and Figure 14, for all the three HIV-pr-inhibitor complexes van der Waals and electrostatic interactions in the gas phase provide the major favorable contributions to the inhibitor binding. Non-polar solvation energies (ΔGnp), resulted from the burial of TMC114 solvent accessible surface area, have also a bit favorable contributions to the binding affinity, and are similar to each other in all of the three cases. Conversely, polar solvation energies (ΔGpb) and entropy components (−TΔS) create the unfavorable contribution to the binding energy.

The relatively small non-polar solvation energies among the three systems indicate that the packing of cavity region is quite closed in all the systems. I50V mutation shows a binding decrease due to electrostatic energy by about 3.17 kcal/mol and van der Waals energy by1.09 kcal/mol relative to the WT, complementing the resistance of I50V to TMC114. This is in accordance to the previously published data of 4.42 kcal/mol and 0.92 kcal/mol for electrostatic and van der Waal’s energy, respectively. 6 For the case of double mutant I50L/A71V, all the energy components are more favorable for its binding to TMC114 except for the polar solvation energy ΔGpb and TΔS of the system relative to the WT complex. The double mutant I50L/A71V results in binding enhancement in terms of electrostatic energy and van der Waals by about −5.52 and −0.42 kcal/mol in the gas phase, and binding decrease in ΔGpb by about 2.0 kcal/mol and TΔS by about 1.06 kcal/mol relative to the WT.

3.7 Structure-binding affinity relationship analysis

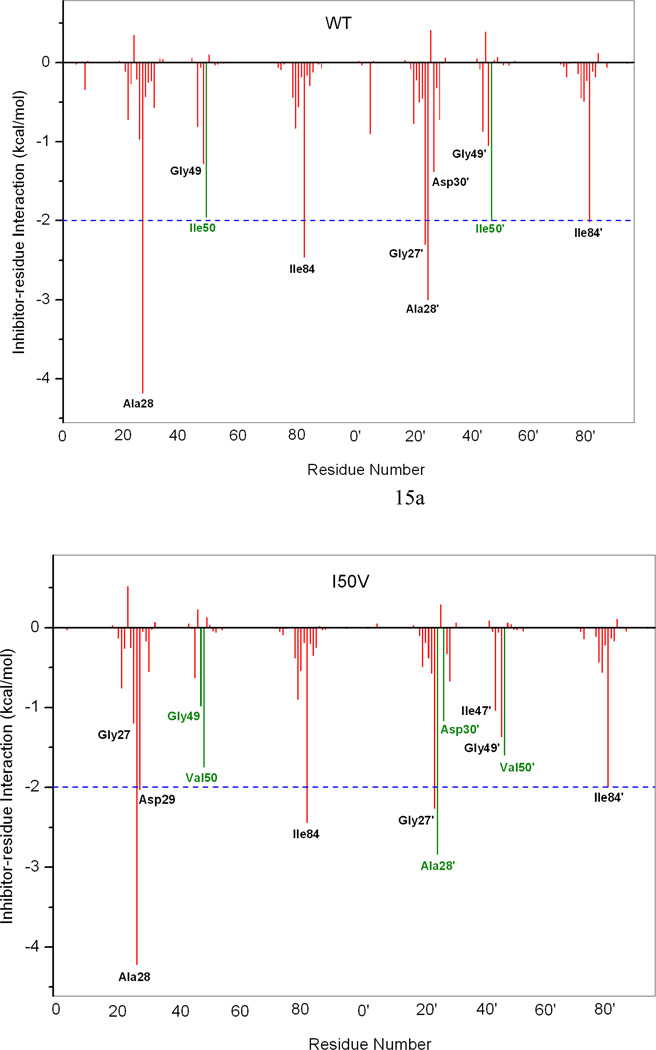

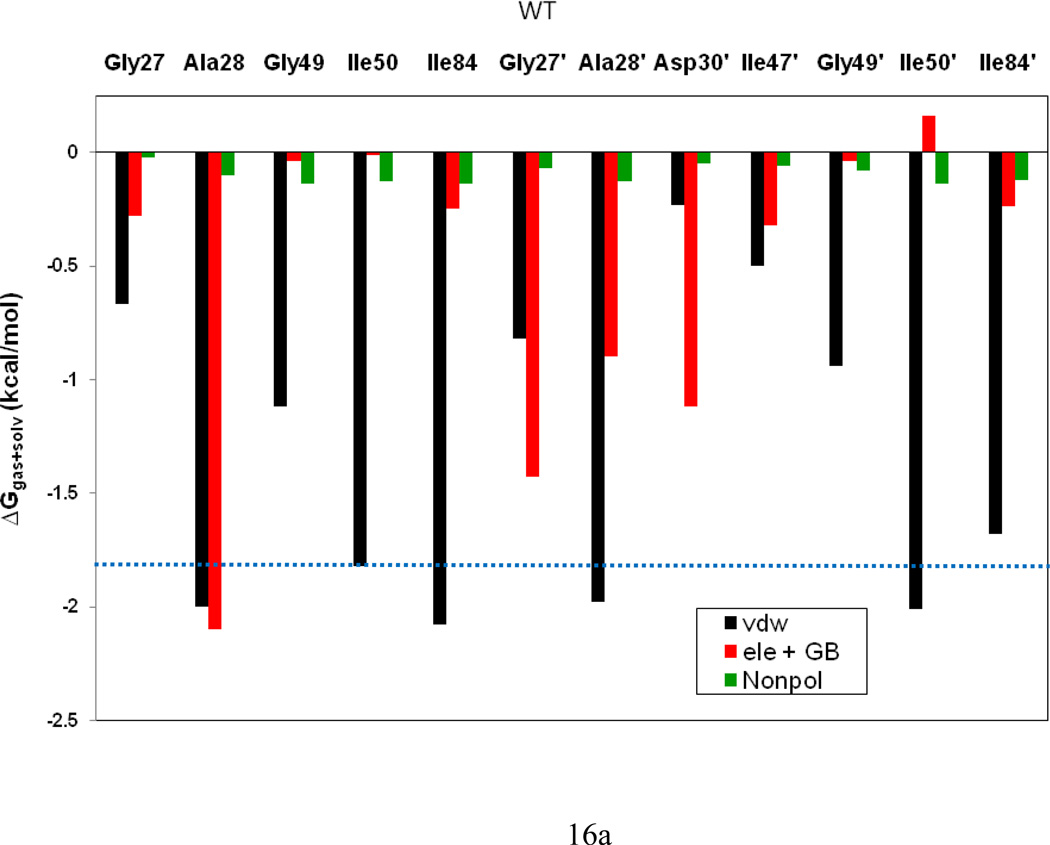

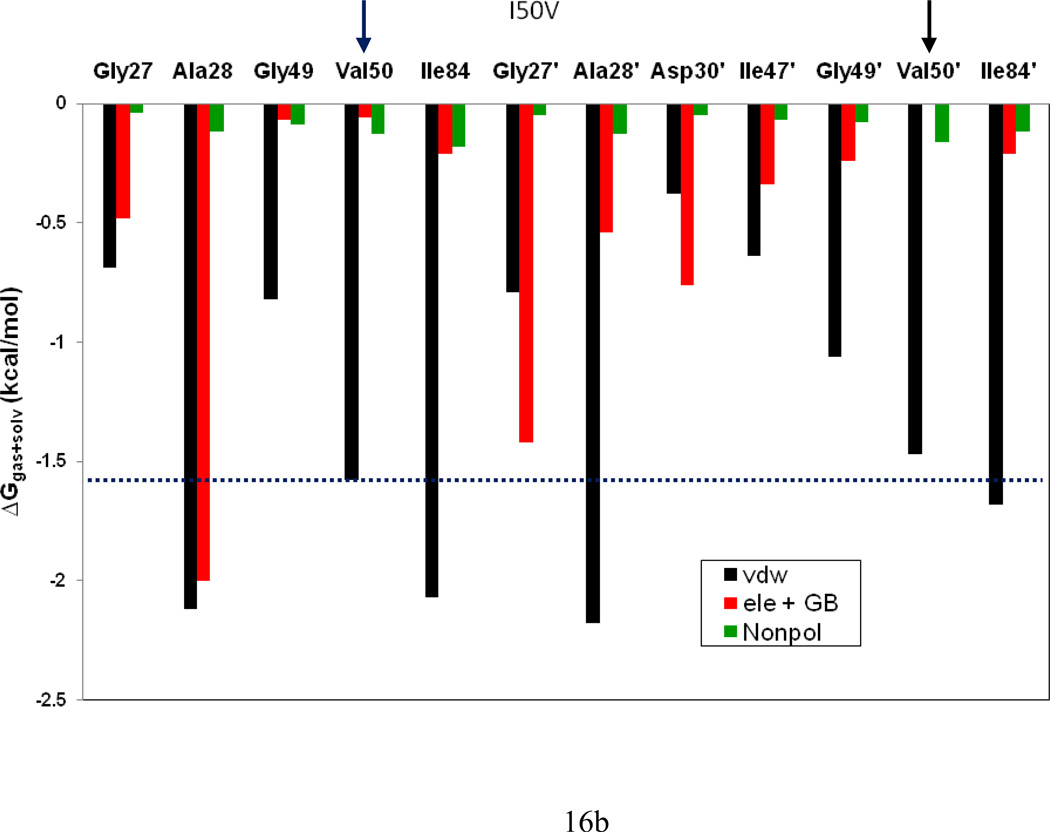

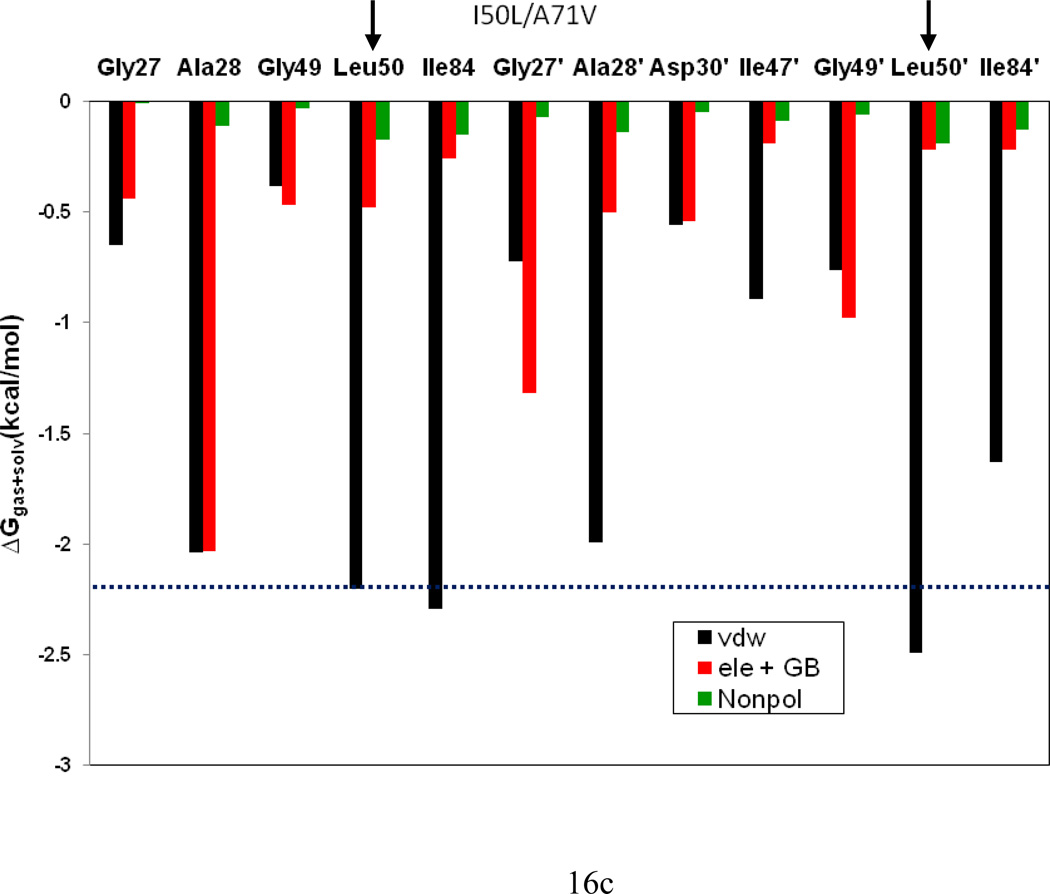

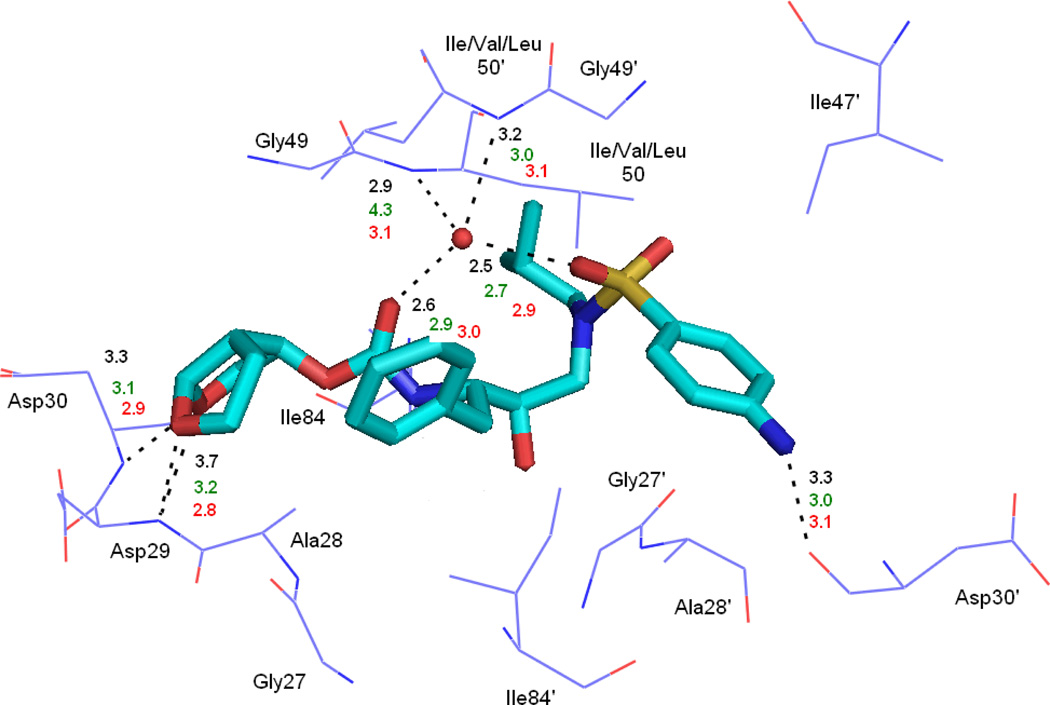

To understand the effect of the two mutations on the interaction between the HIV-pr with TMC114 and to analyze the source of drug resistance, the analysis of structure and binding mode has been accomplished. The binding free energy was decomposed into inhibitor-residue pairs to create an inhibitor-residue interaction spectrum, shown in Figure 15. The approach of residue decomposition method is enormously useful to explain the drug-resistant mechanism at atomistic detail and also helpful to locate contribution of individual residue to the protein-inhibitor interactions as well.18 It shows that, the interaction spectrums of three complexes are similar to each other. Overall, the major interaction comes from a few groups around Ala28/Ala28’, Gly49/Gly49’, Ile50/Ile50’ (Val50/Val50’), and Ile84/Ile84’. These groups of interaction consist at least of 12 residues in total with the bind energy of more than 1kcal/mol. Figure 16 shows the decomposition of ΔG values on a per-residue basis into contributions from van der Waals (ΔEvdw), the sum of electrostatic interactions in the gas phase and polar solvation energy (ΔGpol=ΔEele+ΔGpb) and non-polar solvation energy (ΔGnp) for residues with |ΔG | ≥ 1.0 kcal/mol for all the three complexes. Table 2 further exemplifies the contributions of per residue into those from backbone atoms and those from side-chain atoms. Figure 17 describes the geometries of TMC114 in the binding complex with the relevant residues, which interact robustly with TMC114 by using the lowest-energy structures from the MD simulation. Hydrogen bonds (H-bond) were analyzed on the basis of the trajectories with water molecules of the MD simulations (Table 3) to complement the energetic analysis.

Figure 15.

Decomposition of ΔG on a per-residue basis for the protein-inhibitor complex: (a) WT, (b) I50V and (c) I50L/A71V.

Figure 16.

Decomposition of ΔG on a per-residue basis into contributions from the van der Waals energy (vdw), the sum of electrostatic interactions and polar solvation energy (ele + GB) and non-polar solvation energy (np) for the residues of |ΔG| ≥ 1.0 kcal/mol: (a) WT, (b) I50V and (c) I50L/A71V complexes.

Table 2.

Decomposition of ΔG on a per-residue basis. [a] (GB)

| Residue | Svdw | Bvdw | Tvdw | Sele | Bele | Tele | SGB | BGB | TGB | TSUR | TGBTOT |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT-TMC114 | |||||||||||

| Gly27 | 0.00 | −0.67 | −0.67 | 0.00 | 1.03 | 1.03 | 0.00 | −1.31 | −1.31 | −0.02 | −1.00 |

| Ala28 | −0.61 | −1.39 | −2.00 | 0.22 | −2.03 | −1.81 | −0.01 | −0.28 | −0.29 | −0.10 | −4.19 |

| Gly49 | 0.00 | −1.12 | −1.12 | 0.00 | −1.25 | −1.25 | 0.00 | 1.21 | 1.21 | −0.14 | −1.29 |

| Ile50 | −1.36 | −0.46 | −1.82 | −0.47 | 0.36 | −0.11 | 0.23 | −0.13 | 0.10 | −0.13 | −1.97 |

| Ile84 | −1.92 | −0.16 | −2.08 | 0.16 | −0.02 | 0.14 | −0.29 | −0.10 | −0.39 | −0.14 | −2.47 |

| Gly27’ | 0.00 | −0.82 | −0.82 | 0.00 | −0.56 | −0.56 | 0.00 | −0.87 | −0.87 | −0.07 | −2.31 |

| Ala28’ | −0.61 | −1.37 | −1.98 | 0.14 | −0.70 | −0.56 | 0.05 | −0.39 | −0.34 | −0.13 | −3.01 |

| Asp30’ | −0.25 | 0.02 | −0.23 | −2.76 | −3.68 | −6.44 | 2.91 | 2.41 | 5.32 | −0.05 | −1.39 |

| Ile47’[b] | −0.41 | −0.09 | −0.50 | −0.13 | −0.19 | −0.32 | −0.03 | 0.03 | 0.00 | −0.06 | −0.88 |

| Gly49’ | 0.00 | −0.94 | −0.94 | 0.00 | −0.75 | −0.75 | 0.00 | 0.71 | 0.71 | −0.08 | −1.06 |

| Ile50’ | −1.52 | −0.49 | −2.01 | −0.32 | 0.20 | −0.12 | 0.17 | 0.11 | 0.28 | −0.14 | −2.00 |

| Ile84’ | −1.55 | −0.13 | −1.68 | 0.06 | −0.30 | −0.24 | −0.22 | 0.22 | 0.00 | −0.12 | −2.03 |

| I50V-TMC114 | |||||||||||

| Gly27 | 0.00 | −0.69 | −0.69 | 0.00 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.00 | −1.36 | −1.36 | −0.04 | −1.21 |

| Ala28 | −0.67 | −1.45 | −2.12 | 0.18 | −1.92 | −1.74 | 0.00 | −0.26 | −0.26 | −0.12 | −4.23 |

| Gly49 | 0.00 | −0.82 | −0.82 | 0.00 | −0.81 | −0.81 | 0.00 | 0.74 | 0.74 | −0.09 | −1.00 |

| Val50 | −0.99 | −0.59 | −1.58 | −0.46 | 0.54 | 0.08 | 0.16 | −0.30 | −0.14 | −0.13 | −1.76 |

| Ile84 | −1.90 | −0.17 | −2.07 | 0.11 | −0.02 | 0.09 | −0.21 | −0.09 | −0.30 | −0.18 | −2.45 |

| Gly27’ | 0.00 | −0.79 | −0.79 | 0.00 | −0.85 | −0.85 | 0.00 | −0.57 | −0.57 | −0.05 | −2.27 |

| Ala28’ | −0.76 | −1.42 | −2.18 | 0.10 | −0.31 | −0.21 | 0.05 | −0.38 | −0.33 | −0.13 | −2.85 |

| Asp30’ | −0.27 | −0.11 | −0.38 | −3.18 | −3.19 | −6.37 | 3.30 | 2.31 | 5.61 | −0.05 | −1.18 |

| Ile47’ | −0.52 | −0.12 | −0.64 | −0.02 | −0.09 | −0.11 | −0.08 | −0.15 | −0.23 | −0.07 | −1.05 |

| Gly49’ | 0.00 | −1.06 | −1.06 | 0.00 | −1.08 | −1.08 | 0.00 | 0.84 | 0.84 | −0.08 | −1.38 |

| Val50’ | −0.94 | −0.53 | −1.47 | −0.49 | −0.01 | −0.50 | 0.25 | 0.26 | 0.51 | −0.16 | −1.61 |

| Ile84’ | −1.56 | −0.12 | −1.68 | 0.00 | −0.28 | −0.28 | −0.19 | 0.26 | 0.07 | −0.12 | −2.01 |

| I50L/A71V-TMC114 | |||||||||||

| Gly27 | 0.00 | −0.65 | −0.65 | 0.00 | 0.77 | 0.77 | 0.00 | −1.21 | −1.21 | −0.01 | −1.10 |

| Ala28 | −0.60 | −1.44 | −2.04 | 0.18 | −1.96 | −1.78 | −0.04 | −0.21 | −0.25 | −0.11 | −4.19 |

| Gly49[b] | 0.00 | −0.38 | −0.38 | 0.00 | −1.10 | −1.10 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.63 | −0.03 | −0.88 |

| Leu50 | −1.76 | −0.44 | −2.20 | −0.64 | −0.52 | −1.16 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.68 | −0.17 | −2.85 |

| Ile84 | −2.13 | −0.16 | −2.29 | 0.17 | −0.05 | 0.12 | −0.30 | −0.08 | −0.38 | −0.15 | −2.69 |

| Gly27’ | 0.00 | −0.72 | −0.72 | 0.00 | −0.63 | −0.63 | 0.00 | −0.69 | −0.69 | −0.07 | −2.11 |

| Ala28’ | −0.67 | −1.32 | −1.99 | 0.11 | −0.23 | −0.12 | 0.06 | −0.44 | −0.38 | −0.14 | −2.63 |

| Asp30’ | −0.23 | −0.33 | −0.56 | −2.90 | −3.23 | −6.13 | 3.08 | 2.51 | 5.59 | −0.05 | −1.14 |

| Ile47’ | −0.73 | −0.16 | −0.89 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 0.16 | −0.10 | −0.25 | −0.35 | −0.09 | −1.17 |

| Gly49’ | 0.00 | −0.76 | −0.76 | 0.00 | −1.98 | −1.98 | 0.0 | 1.00 | 1.00 | −0.06 | −1.80 |

| Leu50’ | −1.59 | −0.90 | −2.49 | −0.37 | 0.01 | −0.36 | 0.29 | −0.15 | 0.14 | −0.19 | −2.90 |

| Ile84’ | −1.50 | −0.13 | −1.63 | 0.10 | −0.30 | −0.20 | −0.23 | 0.21 | −0.02 | −0.13 | −1.93 |

Energies shown as contributions from van der Waals energy (vdw), electrostatic energy (ele), polar solvation energy (GB), the non-polar solvation energy (SUR) of side chain atoms (S), backbone atoms (B), and the sum of them , total (T) of protein-inhibitor complex.

Only residues of |ΔG| ≥ 1.0 kcal /mol were listed (except two [b]). All values are given in kcal/mol.

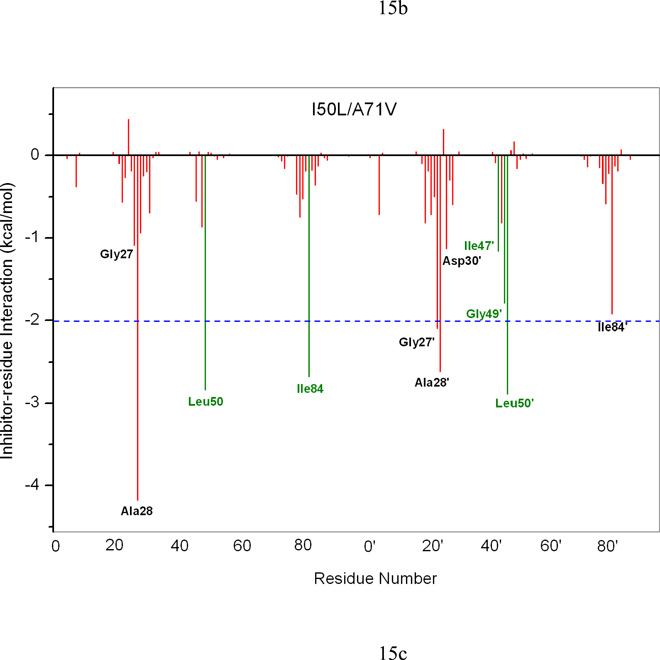

Figure 17.

Geometries of residues with major interactions to TMC114 are plotted. Hydrogen bonds are shown in dashed black line with distances ( black-WT; green-I50V; red-I50L/A71V). TMC114 is indicated in a stick representation, the oxygen of WAT301 is indicated by a red sphere model, and the residues are shown in a line representation.

Table 3.

Hydrogen bonds formed by TMC114 with the HIV-pr and with WAT 301.[a]

| Acceptor | Donor | Wild Type (WT) | I50V | I50L/A71V | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance(Å) | %occupancy | Distance(Å) | %occupancy | Distance(Å) | %occupancy | ||

| TMC114-O9 | WAT-301-O-H | - | - | 2.762 (0.14) | 96.39 | - | - |

| TMC114-O10 | WAT-301-O-H | 2.831 (0.17) | 99.17 | 2.864 (0.18) | 98.37 | 2.796 (0.15) | 99.60 |

| TMC114-O22 | WAT-301-O-H | 2.834 (0.16) | 98.59 | - | - | 2.806 (0.15) | 99.85 |

| WAT-301-O | Ile(Val/Leu)50-N-H | 3.080 (0.17) | 92.72 | 3.068 (0.17) | 94.86 | 3.070 (0.17) | 91.58 |

| WAT-301-O | Ile(Val/Leu)50’-N-H | 3.109 (0.17) | 88.00 | 3.191 (0.17) | 69.50 | 3.076(0.17) | 92.52 |

| TMC114-N1 | Asp30’-N-H | 3.125 (0.15) | 90.85 | 3.125 (0.15) | 88.98 | 3.097 (0.15) | 95.59 |

| TMC114-O26 | Asp30-N-H | 3.238 (0.16) | 66.81 | 3.175 (0.16) | 75.12 | 3.219 (0.16) | 45.95 |

| TMC114-O28 | Asp29-N-H | 3.103 (0.18) | 80.35 | 3.115 (0.19) | 73.69 | 3.108 (0.18) | 51.79 |

| TMC114-O26 | Asp29-N-H | 3.045 (0.17) | 63.79 | 3.035 (0.17) | 54.38 | 3.061 (0.17) | 37.10 |

| TMC114-N1 | Asp29’-N-H | 3.230 (0.15) | 34.64 | 3.246 (0.15) | 23.02 | 3.252 (0.14) | 23.02 |

The H-bonds are determined by the donor….acceptor atom distance of ≤ 3.5 Å and acceptor….H-donor angle of ≥ 120°.

For all twelve residues except for the Ile50’/Val50’ shown in Figure 16a and Table 2, the main force driving for the binding of TMC114 to HIV-pr is van der Waals energy (ΔEvdw), the sum of electrostatic and polar solvation energies (ΔGpol), and approximately −0.1 kcal/mol of non-polar solvation energies (ΔGnp). For Ile50’/Val50’ residue, the favorable forces are van der Waals and non-polar solvation energies, and ΔGpol has unfavorable contribution of 0.16kcal/mol. Taking the WT-HIV-pr as an example, we again investigated the interactions between the main residues and the TMC114. For the residue Ala28, the main force that directs the binding of TMC114 to the HIV-pr includes ΔEvdw and ΔGpol by −2.0 and −2.1 kcal/mol, respectively. The van der Waals energy is likely to be due to the C-H…O weak hydrogen bonds between the alkyl of Ala28 and the bis-THF of TMC114, whereas ΔGpol comes from the positively charged side-chain atoms of Ala28 and the negatively charged oxygen atom of bis-THF moiety of the inhibitor TMC114. Similar to Ala28 in chain-A of HIV-pr, the binding of Ala28’ in chain-B to the TMC-114 is also mainly from van der Waals energy (−1.98 kcal/mol) and ΔGpol (−0.90 kcal/mol). The van der Waals term is due to the C-H…π interaction between the aniline of TMC114 and the alkyl of Ala28’. The N20 atom of TMC114 forms H-bond with the carbonyl oxygen of Gly27 in the initial crystal structure via N-H…O. The H-bond is broken probably due to electrostatic repulsion (Tele=1.03kcal/mol). The hydrophobic interaction with the van der Waals energy between Gly27 and TMC114 directs the binding. As shown in Figure 17, the H-bond analysis indicates that, atoms O26 and O28 of the bis-THF group form three H-bonds with the main-chain amides of Asp29 and Asp30, respectively. The H-bonds with high percentage of occupancy indicates that the interactions between the two residues and TMC114 are relatively strong. Moreover, the residue-inhibitor interaction energies justify the presence of H-bonds between the bis-THF group and the side chain of the Asp29 and Asp30 residues (Table 3 and Figure 17). Similarly, the N1 atom of TMC114 forms a H-bond with the carbonyl oxygen of Asp30’ through N-H…O. This analysis is in accordance to the strong side-chain electrostatic energy (Sele= −2.76 kcal/mol) and backbone electrostatic energy (Bele = −3.68 kcal/mol) in Table 2. However, the residue decomposition for Asp30’ shows that the polar solvation energies considerably decrease the binding of WT-TMC114 by 5.32 kcal/mol. Thus, the total contribution from polar solvation energies and electrostatic energy is the key driving force for the binding of TMC114 to Asp30’ (Figure 16a). Furthermore, the central phenyl in TMC114 interacts with the alkyl of the residues Gly49/Gly49’, Ile50/Ile50’ through C-H… π. The bis-THF group of TMC114 interacts with the alkyl of the residue Ile84 via C-H… O, and aniline of TMC114 interacts with the alkyl of residue Ile84’ through C-H…π. Thus, the van der Waals energy favors the binding of these six residues (Figure 16a). For Ile50/50’ and Val50/50’, although the main driving force to the binding is van der Waals energy with a small unfavorable ΔGpol in cases of WT-TMC and I50V-TMC (Figures 16a and 16b), a favorable ΔGpol along with the van der Waals energy plays important roles in binding of TMC114 to I50L/A71V double mutant (Figure 16c).

3.8 Direct and indirect effects of mutations on the binding affinity

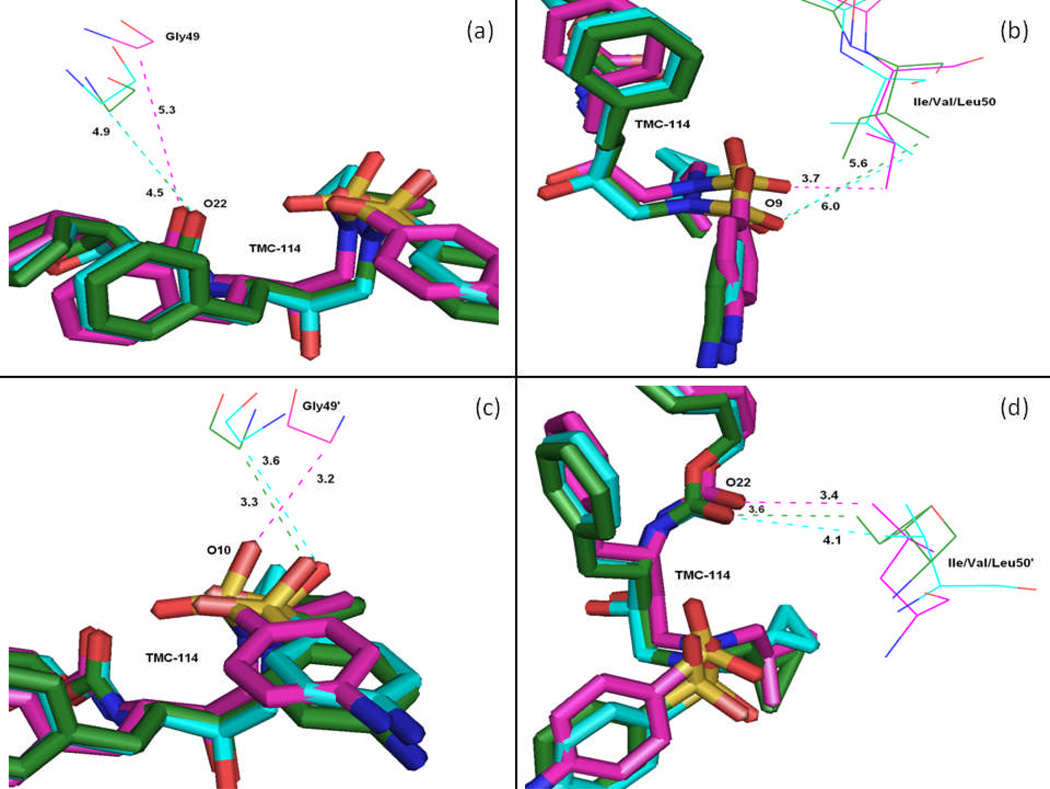

According to TGBTOT in Table 2 and Figure 15, the I50V mutant directly reduces the binding affinity by approximately 0.21 (Ile50 to Val50) and 0.39 (Ile50’ to Val50’) kcal/mol, which only accounts 18% for the total loss of the binding affinity. In line with the more opening of apo I50V-HIV-pr, the entropy effect decreases the binding affinity more than WT by 1.19 kcal/mol. In the I50V mutant HIV-pr, the replacement of isoleucine with valine results in a loss of methyl group, which apparently decreases the interaction with the central phenyl of TMC 114 through C-H…π, the size of the hydrophobic side chain and possible increase of the size of the active site with a reduced binding affinity to TMC114. According to Table 2, this change results in a decrease of van der Waals energy between Val50 and TMC114 by about 0.24 kcal/mol relative to the WT, which agree well with the result from Chen et al. with 0.39kcal/mol.6 However, for Val50’ the change shows a more significant decrease in van der Waals energy by 0.54 kcal/mol, which may be due to the lessening of C-H…O interactions between the Val50’ side chains and the O22 of TMC114. Figure 18d confirms that the C…O22 for I50V-HIV-pr is longer than those for WT and I50L/A71V-HIV-pr (4.1 vs 3.6Å). The electrostatic energy in the present result is not high as that of Chen et al. for Val50’ (Tele: −2.03 6 vs −0.50 kcal/mol).

Figure 18.

C-H…O interactions between the TMC114 and the flap residues (Gly49, Gly49’, Ile/Val/Leu50, and Ile/Val/Leu50’). TMC114 in sticks is colored by the atom type, and residues are shown as lines (green-WT; blue-I50V; purple-I50L/A71V).

Table 2 and Figure 15 show that, besides the direct effects from the residues Val50 and Val50’, the residues Gly49, Ala28’ and Asp30’ also considerably decrease the binding affinity of I50V-HIV-pr to the inhibitor by 0.29, 0.16 and 0.21 kcal/mol, respectively, accounting approximately another 20% for the total binding loss. For the residue Gly49, the decreases of van der Waals (ΔTvdw=0.30 kcal/mol) and electrostatic (ΔTelec=0.44kcal/mol) of the backbone are mainly responsible for its binding loss. For the residue Ala28’, the electrostatic interaction of the backbone is decreased by 0.39kcal/mol. There exists one H-bond between the TMC114 and Asp30’ side-chain carbonyl oxygen. This is in accordance to the favorable electrostatic interaction of TMC114 and Asp30’ side chain, but accompanied by the increase in polar solvation energy of Asp30’ by about 0.36 kcal/mol relative to the WT, counterbalance the favorable electrostatic. Hence, on the basis of above structural energetic analysis discussed, we can conclude that the direct effects from Val50 and Val50’, e.g., the decrease in van der Waals for both residues and the increase in polar solvation energy for Val50’, with a few other residues Gly49, Ala28’ and Asp30’ accomplish the drug resistance in I50V mutant.

Table 2 further shows that the I50L/A71V mutant directly increase the binding affinity by approximately −0.88 (Ile50 to Leu50) and −0.90 (Ile50’ to Leu50’) kcal/mol, which accounts 45% for the total gain of the binding affinity. The secondary mutation A71V does not have much direct effect on the binding. For the mutation from Ile50 to Leu50, the binding enhancement can be mainly attributed to the electrostatic by −1.05kcal/mol and van der Waals by −0.38 kcal/mol, yet considerably being compromised by the increase of the polarization energy of 0.58 kcal/mol; whereas from Ile50’ to Leu50’ the contribution from the electrostatic is only −0.24 kcal/mol and the van der waals term is significant by −0.48kcal/mol. Besides the direct effects from the residues Leu50 and Leu50’, the residue Gly49’ considerably increases the binding affinity of I50L/A71V-HIV-pr to the inhibitor by −0.74 kcal/mol, to which the electrostatic energy of Leu50’s backbone contributes by −1.23kcal/mol. According to Figures 17b–d, these enhancements are also consistent with the shortest distances of C-O10, C-O9, and C-O22 for Gly49’, Leu50 and Leu50’of I50L/A71V-HIV-pr, respectively, as compared to those of WT and I50V-HIV. Another two residues Ile84 and Ile47’ also increase the binding affinity by −0.22 and −0.29kcal/mol, respectively, which can be mainly attributed to van der Waals terms (ΔTvdw: −0.21 and −0.39 kcal/mol).

In the I50L/A71V double mutant HIV-pr, the isoleucine-to-leucine substitution places the methyl group in a different position without significant change in the conformation of the side chain. However, the alanine-to-valine substitution imposes the addition of two methyl groups to the backbone carbon in place of single methyl, which changes the side chain conformation a bit bulkier and need more space to accommodate it towards the enzyme interior. Compared to the WT and I50V mutant, the I50L/A71V HIV-pr has less stability of the H-bonding between the Asp29, Asp30 with the O26 and O28 of bis-THF group. The occupancy of the H-bonding is reduced to less than 50% (Table 3). The change in H-bonding for I50L/A71V HIV-pr results in a reduction of polarity energies (Eele+TGB) of residue Asp30’ by about 0.58 kcal/mol compared to the WT case (Figure 5c). Thus, the loss of H-bonding between TMC114 and the side chain of Asp30 (Asp29) and the polar solvation energies for Asp30’ indirectly relate to the binding of I50L/A71V HIV-pr to TMC114. This may be an indirect effect of the mutations pair that can be related to the allosteric nature.

Hydrogen bonds formed between β-strands (connecting residues 71…64, 65…14, 13…20) in both the chains of the HIV-pr have been summarized in Table 4. It is noted that, the change from Ala71 to Val71 in the cantilever region of the HIV-pr has not affected much the H-bond pattern, which can be seen with ≥ 90% occupancy. However, the H-bond between the residues Arg14’ and Glu65’ has been reduced to an occupancy with ~75%, which can still be stable enough for a H-bond to exist. This result confirms that, mutation A71V does not have direct influence on the active site conformation and binding affinity. Rather, it has allosteric effect on the binding affinity with change in the mobility of active site residues by H-bond propagation from the site of mutation to the active site region. The resultant change in conformation of the protein, may affect the binding affinity of the inhibitor TMC114 to the protease.

Table 4.

Hydrogen bonds formed between β-strands (connecting residues 71…64, 65…14, 13…20)[a] in both the chains of HIV-pr.

| Acceptor | Donor | Wild Type (WT) | I50V | I50L/A71V | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance(Å) | %occupancy | Distance(Å) | %occupancy | Distance(Å) | %occupancy | ||

| Glu65-O | Arg14-N-H | 3.077 (0.18) | 90.76 | 2.980 (0.16) | 96.96 | 3.043 (0.19) | 94.29 |

| Glu65’-O | Arg14’-N-H | 3.014 (0.19) | 99.00 | 2.973 (0.15) | 99.01 | 3.003 (0.18) | 75.84 |

| Arg14-O | Glu65- N-H | 2.991 (0.17) | 97.51 | 3.142 (0.17) | 91.86 | 3.030 (0.18) | 96.08 |

| Arg14’-O | Glu65’- N-H | 2.830 (0.16) | 94.84 | 3.136 (0.17) | 91.74 | 3.065 (0.19) | 73.36 |

| Val64-O | Ala/Val71-N-H | 2.985 (0.16) | 99.01 | 2.949 (0.14) | 99.39 | 2.966 (0.14) | 99.46 |

| Val64’-O | Ala/Val71’-N-H | 2.946 (0.14) | 99.02 | 2.960 (0.14) | 99.05 | 2.972 (0.14) | 99.47 |

| Ala71-O | Val64- N-H | 2.932 (0.13) | 99.84 | 2.981 (0.15) | 99.33 | 2.935 (0.13) | 99.86 |

| Ala71’-O | Val64’- N-H | 2.919 (0.13) | 99.85 | 3.049 (0.15) | 98.41 | 2.961 (0.14) | 98.65 |

| Lys20-O | Ile13-N-H | 2.860 (0.11) | 99.76 | 2.864 (0.11) | 99.91 | 2.868 (0.11) | 99.80 |

| Lys20’-O | Ile13’-N-H | 2.866 (0.11) | 99.81 | 2.866 (0.11) | 99.94 | 2.892 (0.11) | 99.97 |

| Ile13-O | Lys20- N-H | 2.966 (0.14) | 99.26 | 2.980 (0.14) | 99.56 | 2.962 (0.15) | 99.59 |

| Ile13’-O | Lys20’- N-H | 2.990 (0.15) | 99.41 | 2.981 (0.15) | 99.41 | 2.975 (0.14) | 99.64 |

The H-bonds are determined by the donor….acceptor atom distance of ≤ 3.5 Å and acceptor….H-donor angle of ≥ 120°.

It was noted that during the 20 ns MD simulations the water (WAT 301) that makes bridges between the inhibitor and flap tip residues Ile50/Ile50’ was observed to be well maintained for all of three protease systems. The water molecule WAT301 in the investigated three HIV-pr-inhibitor complexes connects the inhibitor and protein via four H-bonds (Table 3 and Figure 17). According to Table 3, the occupancy of these four H-bonds is higher than 88% except for the bond between the Val50’ and WAT301 in case of the I50V mutant, where the occupancy is ~70%. Regardless of the change in residues from isoleucine to valine in I50V or isoleucine to leucine in I50L/A71V, the mutations do not have a greater impact on the stability of the function of WAT301. This observation suggests that WAT301 hardly involve in the resistance of both I50V single and I50L/A71V double mutant to TMC114.

4. Remarks on flap dynamics and binding affinity

The MD simulation results show that for the apo protein, there is difference in dynamic motion of WT and mutant involving the residues in the dimer interface (Trp6 & Arg8), flap elbow (Gly40-Lys41) and flap tip (Ile/Val/Leu50-Gly51) regions. In the case of the complexed HIV-pr, the difference in dynamic motion between WT and mutant was little more than that of the apo protein relative to the motion of residues in the dimer interface (Trp6 & Arg8), flap elbow (Pro39-Trp42) and fulcrum (Gly16–17) regions. However as expected, the difference in the dynamic motion of flap tip region is smaller due to the binding of the inhibitor. For both the apo and complexed HIV-pr, the analysis indicates many intriguing effects due to the double mutant, I50L/A71V. The flap curling and opening events in I50L/A71V-HIV-pr are more stable than WT and I50V mutant. The average flap tip – active site, flap –flap distances and curling behavior of the TriCa angles suggests a closer movement of flaps in the double mutant as compared to WT and I50V, probably making the active site volume smaller. The reduced active site conformations of the double mutant due to the flap dynamics behavior may enhance the binding of the inhibitor to the active site region. This may be due to the decreased flexibility in the active site leads to the decrease in Km, i.e. an increase in the affinity of the enzyme for the inhibitor and stronger binding.49 The most distinct motion for the HIV-pr complex was the movement of the side chain of catalytic Asp25 about the inhibitor. There is a flip-flop of the interaction between the catalytic Asp25 OD1/OD2 atoms and O18 of TMC114. This may be due to the effect of the mutation A71V from the double mutant, where the change from Ala71 to Val modifies the H-bonding pattern between the four anti-parallel β-sheets connecting Asp25 site to Val71. The change in H-bonding pattern induces the rearrangement of β-sheets and finally affects the dynamics of Asp25 residues. The flip-flop interactions justifies that the inhibitor tries to bind to either of the OD1/OD2 atoms of Asp25 in I50L/A71V, which seems to be different from that of WT and I50V. Consequently, the binding of the inhibitor to the protein differs for the double mutant. Such finding suggests a replacement of different group at the O18 atom of TMC114 might provide the better binding properties.

In line with the previous studies, as compared with the WT HIV-pr the decrease of the binding affinity of I50V-HIV-pr to TMC114 was confirmed. The decrease in the binding affinity derives the drug resistance, which was experimentally discovered by Kovalevsky et al.. 4 However, the double mutant I50L/A71V-HIV-pr displays an enhanced binding to the inhibitor relative to the WT HIV-pr. The increase of the binding implies that the double mutant I50L/A71V may be well adapted by the TMC114. The energy decomposition analysis suggests that the increase of the binding affinity for the double mutant I50L/A71V can be mainly attributed to the increase in electrostatic and van der Waals energies, which are cancelled out in part by the increase of polar solvation energy. A per-residue basis decomposition investigation shows that the I50L/A71V mutant directly increases the binding affinity by approximately −0.88 (Ile50 to Leu50) and −0.90 (Ile50’ to Leu50’) kcal/mol, accounting 45% for the total gain of the binding affinity. Besides the direct effect from the residues Leu50 and Leu50’, the residue Gly49’ considerably increases the binding affinity of I50L/A71V-HIV-pr to the inhibitor by −0.74 kcal/mol, to which the electrostatic interaction of Leu50’s backbone contributes by −1.23kcal/mol. Another two residues Ile84 and Ile47’ also increase the binding affinity by −0.22 and −0.29kcal/mol, respectively, which can be mainly attributed to van der waals terms (ΔTvdw: −0.21 and −0.39 kcal/mol).

5. Conclusions

The double mutant I50L/A71V HIV-pr exhibits different conformation and dynamic behavior to the TMC114 inhibitor, e.g., closer movement of flaps, and flip-flop interaction between the catalytic Asp25 OD1/OD2 atoms and O18 of TMC114, which may imply less drug resistance, which was further verified in terms of binding affinity to the inhibitor in the energetic calculation. On the basis of the structural energetic analysis, we can conclude that the direct effects by the decrease in van der Waals energies for residues Val50 and Val50’ and the increase in polar solvation energy for Val50’ mainly accomplish the drug resistance in I50V mutant. However, for the double mutant I50L/A71V, the increase in the binding affinity can be mainly attributed to the increase in electrostatic and van der Waals energies of residues Leu50 and Leu50’ with considerable aid from the other flap residues Gly49’, Ile47’ and active site residue Ile84. As for the other protease inhibitors, the increase of the binding affinity implies that the double mutant I50L/A71V may be well adapted by the TMC114. The present article offers a quantitative and mechanistic rationalization of mutational effect from a comprehensive analysis of the structure-affinity relationship. We anticipate that, the current study can give some useful insights into the nature of mutational effect and the difference in binding affinity for darunavir in protease variants may support the future design of more potent and effective HIV-pr inhibitors.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical of the National Institute of Health (SC3GM082324 and 2R25GM071415), the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (3SC3GM082324-02S1) and ACS PRF (47286-GB5) in terms of scholarly development. The authors thank Pittsburgh Supercomputing Center, NCSA-Teragrid for providing the computational facilities to carry out the work in the form of a startup grant (CHE100117).

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Figure S1 displays Root-mean-square-displacement (RMSD) plot for backbone Cα atoms relative to their initial minimized apo structures as a function of time. Table S1 summarizes the binding affinities from two parallel simulations. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Wlodawer A, Vondrasek J. Annu Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1998;27:249–284. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.27.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wu TD, Schiffer CA, Gonzales MJ, Taylor J, Kantor R, Chou S, Israelski D, Zolopa AR, Fessel WJ, Shafer RW. J. Virol. 2003;77:4836–4847. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.8.4836-4847.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tie Y, Boross PI, Wang YF, Gaddis L, Hussain AK, Leshchenko S, Ghosh AK, Louis JM, Harrison RW, Weber IT. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;338:341–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kovalevsky AY, Tie Y, Liu F, Boross PI, Wang YF, Leshchenko S, Ghosh AK, Harrison RW, Weber IT. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:1379–1387. doi: 10.1021/jm050943c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang YF, Tie Y, Boross PI, Tozser J, Ghosh AK, Harrison RW, Weber IT. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:4509–4515. doi: 10.1021/jm070482q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen J, Zhang S, Liu X, Zhang Q. J. Mol. Model. 2010;16:459–468. doi: 10.1007/s00894-009-0553-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu GD, Zhu T, Zhang SL, Wang D, Zhang QG. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2010;45:227–235. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.09.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai Y, Schiffer CA. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2010;6:1358–1368. doi: 10.1021/ct9004678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stoica I, Sadiq SK, Coveney PV. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:2639–2648. doi: 10.1021/ja0779250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hou T, Yu R. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:1177–1188. doi: 10.1021/jm0609162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ode H, Neya S, Hata M, Sugiura W, Hoshino T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:7887–7895. doi: 10.1021/ja060682b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ode H, Matsuyama S, Hata M, Hoshino T, Kakizawa J, Sugiura W. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:1768–1777. doi: 10.1021/jm061158i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang W, Kollman PA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2001;98:14937–14942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.251265598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yanchunas J, Jr, Langley DR, Tao L, Rose RE, Friborg J, Colonno RJ, Doyle ML. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005;49:3825–3832. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.9.3825-3832.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Colonno R, Rose R, McLaren C, Thiry A, Parkin N, Friborg J. J. Infect. Dis. 2004;189:1802–1810. doi: 10.1086/386291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skalova T, Dohnalek J, Duskova J, Petrokova H, Hradilek M, Soucek M, Konvalinka J, Hasek J. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:5777–5784. doi: 10.1021/jm0605583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinheimer S, Discotto L, Friborg J, Yang H, Colonno R. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005;49:3816–3824. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.9.3816-3824.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu EL, Han K, Zhang JZ. Chemistry. 2008;14:8704–8714. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hou T, Zhang W, Case DA, Wang W. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;376:1201–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu EL, Mei Y, Han K, Zhang JZ. Biophys. J. 2007;92:4244–4253. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.099150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xu Y, Wang R. Proteins. 2006;64:1058–1068. doi: 10.1002/prot.21044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strockbine B, Rizzo RC. Proteins. 2007;67:630–642. doi: 10.1002/prot.21301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zou H, Luo C, Zheng S, Luo X, Zhu W, Chen K, Shen J, Jiang H. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2007;111:9104–9113. doi: 10.1021/jp0713763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Morin P, Wang W, Kollman PA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:5221–5230. doi: 10.1021/ja003834q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheatham TE, 3rd, Srinivasan J, Case DA, Kollman PA. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 1998;16:265–280. doi: 10.1080/07391102.1998.10508245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gohlke H, Kiel C, Case DA. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;330:891–913. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00610-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Surleraux DL, Tahri A, Verschueren WG, Pille GM, de Kock HA, Jonckers TH, Peeters A, De Meyer S, Azijn H, Pauwels R, et al. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:1813–1822. doi: 10.1021/jm049560p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Prabu-Jeyabalan M, Ng C, King NM, Bandaranayake R, Naliveika EA, Schiffer CA. RSCB-PDB [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hyland LJ, Tomaszek TA, Jr, Meek TD. Biochemistry. 1991;30:8454–8463. doi: 10.1021/bi00098a024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang YX, Freedberg DI, Yamazaki T, Wingfield PT, Stahl SJ, Kaufman JD, Kiso Y, Torchia DA. Biochemistry. 1996;35:9945–9950. doi: 10.1021/bi961268z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bayly CI, Cieplak P, Cornell W, Kollman PA. J. Phys. Chem. 1993;97:10269–10280. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dewar MJS, Zoebisch EG, Healy EF, Stewart JJP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1985;107:3902–3909. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang J, Wolf RM, Caldwell JW, Kollman PA, Case DA. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1157–1174. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Case DA, Darden TA, Cheatham TE, III, Simmerling CL, Wang J, Duke RE, Luo R, Crowley M, Walker RC, Zhang W, et al. AMBER 10. San Francisco, CA: University of California; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hornak V, Abel R, Okur A, Strockbine B, Roitberg A, Simmerling C. Proteins. 2006;65:712–725. doi: 10.1002/prot.21123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jorgensen WL, Chandrasekhar J, Madura JD, Roger W Impey, Klein ML. J. Chem. Phys. 1983;79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Essmann U, Perera L, Berkowitz ML, Darden T, Lee H, Pedersen LG. J. Chem. Phys. 1995;103:8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berendsen HJC, Postma JPM, Van Gunsteren WF, DiNola A, Haak JR. J. Chem. Phys. 1984;81:3684–3693. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryckaert JP, Ciccotti G, Berendsen HJC. J. Comput. Phys. 1977;23:327–341. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Onufriev A, Bashford D, Case DA. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2000;104:3712–3720. [Google Scholar]

- 41.PyMol; Version 1.3 ed. LLC: Schrödinger; www.pymol.org. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Todd MJ, Freire E. PROTEINS: Structure, Function, and Genetics. 1999;36:147–156. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19990801)36:2<147::aid-prot2>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maschera B, Darby G, Palu G, Wright LL, Tisdale M, Myers R, Blair ED, Furfine ES. J. Biol. Chem. 1996;271:33231–33235. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.52.33231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perryman AL, Lin JH, McCammon JA. Protein Sci. 2004;13:1108–1123. doi: 10.1110/ps.03468904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Piana S, Carloni P, Rothlisberger U. Protein Sci. 2002;11:2393–2402. doi: 10.1110/ps.0206702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Scott WR, Schiffer CA. Structure. 2000;8:1259–1265. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00537-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rick SW, Erickson JW, Burt SK. Proteins. 1998;32:7–16. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(19980701)32:1<7::aid-prot3>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu Z, Schuster DI, Tuckerman ME. Biochemistry. 2003;42:1326–1333. doi: 10.1021/bi020496s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zoldak G, Sprinzl M, Sedla E. Eur. J. Biochem. 2004;271:48–57. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Freedberg DI, Wang YX, Stahl SJ, Kaufman JD, Wingfield PT, Kiso Y, Torchia DA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998;120:7916–7923. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zoete V, Michielin O, Karplus M. J. Mol. Biol. 2002;315:21–52. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ishima R, Freedberg DI, Wang YX, Louis JM, Torchia DA. Structure. 1999;7:1047–1055. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(99)80172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bandyopadhyay P, Meher BR. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2006;67:155–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2006.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nalam MN, Ali A, Altman MD, Reddy GS, Chellappan S, Kairys V, Ozen A, Cao H, Gilson MK, Tidor B, Rana TM, Schiffer CA. J. Virol. 2010;84:5368–5378. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02531-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]