Abstract

Background

Street youth represent a marginalized population marked by early mortality and elevated risk for suicide. It is not known to what extent childhood abuse and neglect predispose to suicide in this difficult-to-study population. This study is among the first to examine the relationship between childhood trauma and subsequent attempted suicide during adolescence and young adulthood among street youth.

Methods

From October 2005 to November 2007, data were collected for the At Risk Youth Study (ARYS), a cohort of 495 street-recruited youth aged 14–26 in Vancouver, Canada. Self-reported attempted suicide in the preceding six months was examined in relation to childhood abuse and neglect, as measured by the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), using logistic regression.

Results

Overall, 46 (9.3%) youth reported a suicide attempt during the preceding six months. Childhood physical and sexual abuse were highly prevalent, with 201 (40.6%) and 131 (26.5%) of youth reporting history of each, respectively. Increasing CTQ score was related to risk for suicide attempt despite adjustment for confounders (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.45 per standard deviation increase in score; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08–1.91).

Limitations

Use of snowball sampling may not have produced a truly random sample, and reliance on self-report may have resulted in underreporting of risk behaviors among participants. Moreover, use of cross-sectional data limits the degree to which temporality can be concluded from the results of this study alone.

Conclusions

There exists a strong and graded association between childhood trauma and subsequent attempted suicide among street youth, an otherwise ‘hidden’ population. There is need for effective interventions that not only prevent maltreatment of children but also aid youth at increased risk for suicide given prior history of trauma.

MeSH Keywords: homeless youth, suicide, child abuse, child neglect, depression

INTRODUCTION

Among adolescents and adults in the general population, risk of suicide is elevated among those with history of childhood physical, sexual or emotional abuse (Dube et al., 2001; Duke et al., 2010). Street youth, a term generally referring to young people who live on the street full- or part-time, demonstrate early mortality and excess risk of suicide compared to their mainstream peers (Roy et al., 2004). Since street youth represent a ‘hidden’ population that often evades standard school- and population-based sampling (Public Health Agency of Canada, 2006), it is unknown to what extent childhood trauma may be related to risk of suicide in this highly marginalized and at-risk group.

The present study attempts to replicate the finding that childhood trauma is associated with attempted suicide in a novel population, street youth, who are at once highly vulnerable and greatly understudied.

METHODS

The At Risk Youth Study (ARYS) follows a cohort of youth with extensive street involvement in Vancouver, Canada, and has been described previously (Wood et al., 2006). Inclusion criteria included (1) age 14 to 26 years at enrollment, and (2) use of an illicit drug other than or in addition to marijuana in the month prior to enrollment. Recruitment employed street-based outreach methods and snowball sampling. All participants completed a nurse-administered questionnaire, thus providing sociodemographic information and data on suicidal ideation and attempts, as well as drug-related and sexual risk behaviors. ARYS was approved by the University of British Columbia/Providence Health Care Research Ethics Board.

The ARYS cohort is a sample of young people, the majority of whom are homeless and have not completed high school (Wood et al., 2008). A small proportion of participants have been involved in the sex trade, but most report a history of prior incarceration for at least brief periods of time. Approximately half have previously been a victim of violence, and a majority report having been the perpetrator of a violent act. Although some youth are only transiently on the street, a number report having been intensely street-involved for long periods of time, often measured in years (Fast et al., 2009).

Active drug use in the greater street youth population in Vancouver, British Columbia is high. Commonly used substances include crystal methamphetamine, crack, cocaine, heroin and marijuana. In the ARYS cohort, injection drug use is common among older youth (Hadland et al., 2010), and many participants self-describe their drug use habits as problematic (Fast et al., 2009). Many report a prior history of accessing or attempting to access drug treatment (Hadland et al., 2009). In general, ARYS youth are heavily involved in the drug scene, and report being consumed by surviving despite homelessness, chronic poverty and often dangerous income generation activities (Fast et al., 2009).

We hypothesized that among street youth, history of childhood trauma would be strongly associated with suicidal attempt later in adolescence and young adulthood. Self-reported suicidal ideation and attempts, respectively, were assessed in the ARYS questionnaire through the questions, “In the last 6 months, have you ever seriously thought of taking your own life?” and “In the last 6 months, have you actually attempted suicide?” At-risk participants were referred for further psychiatric services as indicated. Childhood trauma was assessed using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire (CTQ), a 28-item survey assessing physical, sexual and emotional abuse and physical and emotional neglect that is valid and reliable when applied to adolescent and substance-using samples (Bernstein et al., 2003).

Logistic regression was employed with recent suicide attempt as the dependent variable and total CTQ score as an independent variable. To adjust for possible confounders, bivariate associations between recent suicide attempt and a range of sociodemographic, drug use and behavioral variables were explored; variables associated with suicide attempt with p < 0.10 were included as covariates in the final logistic regression model. Gender was additionally forced into the model to specifically examine the effect of this variable. Subsequently, the role of depressive symptoms as a mediator of the relationship between childhood trauma and risk of attempted suicide, which has been demonstrated previously (Dube et al., 2001), was explored using the Sobel test (Sobel, 1982). Depressive symptoms were measured using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) scale (Radloff, 1991) and scores were dichotomized to <22 vs. ≥22.

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.1 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, North Carolina). All reported p values are two-sided and considered significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

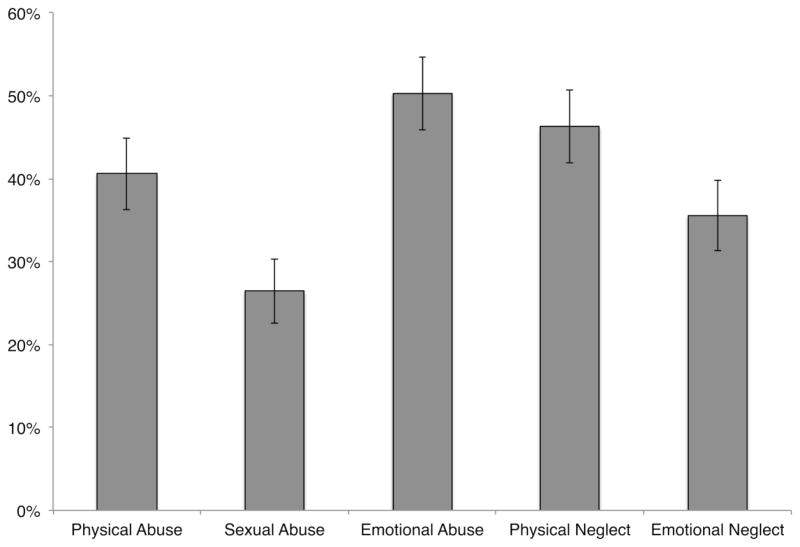

Between October 2005 and November 2007, 495 youth were recruited into the ARYS cohort and provided data on history of attempted suicide. Of these, 182 (36.8%) reported lifetime history of suicidal ideation and 46 (9.3%) reported an actual attempt during the preceding six months. Table 1 demonstrates characteristics of youth surveyed. Figure 1 demonstrates the prevalence of childhood trauma among study participants.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic factors, risk behaviors and childhood trauma and their associations with suicide attempt in the preceding six months (n = 495)

| Characteristic | Total (%) n = 495 | Recent suicide attempta |

Unadjusted Odds Ratio (OR) (95% CI) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (%) n = 46 | No (%) n = 449 | ||||

| Demographic/Behavioral | |||||

| Male gender | 340 (68.7) | 27 (58.7) | 313 (69.7) | 3.08 (2.13 – 4.45) | <0.125 |

| Age (mean, SD) | 21.8 (2.8) | 22.5 (2.8) | 21.7 (2.8) | 1.11 (0.93 – 1.24) b | 0.067 |

| High school educationc | 202 (40.8) | 23 (50.0) | 179 (39.9) | 1.51 (0.82 – 2.77) | 0.183 |

| Recently homelessa | 375 (75.8) | 32 (69.6) | 343 (76.4) | 0.71 (0.36 – 1.37) | 0.304 |

| Daily alcohol consumptiona | 68 (13.7) | 7 (15.2) | 61 (13.4) | 1.14 (0.49 – 2.67) | 0.760 |

| Sex trade involvement | 56 (11.3) | 9 (19.6) | 47 (10.5) | 2.08 (0.95 – 4.58) | 0.064 |

| CES-D score ≥22d | 197 (39.8) | 34 (73.9) | 163 (36.3) | 4.97 (2.50 – 9.87) | <0.001 |

| Abuse/Neglect | |||||

| Physical abuse | 201 (40.6) | 25 (54.4) | 176 (39.2) | 1.85 (1.00 – 3.40) | 0.046 |

| Sexual abuse | 131 (26.5) | 16 (34.8) | 115 (25.6) | 1.54 (0.81 – 2.95) | 0.180 |

| Emotional abuse | 249 (50.3) | 33 (71.7) | 216 (48.1) | 2.74 (1.40 – 5.34) | 0.002 |

| Physical neglect | 229 (46.3) | 28 (60.9) | 201 (44.8) | 1.91 (1.03 – 3.57) | 0.037 |

| Emotional neglect | 176 (35.6) | 24 (52.2) | 152 (33.9) | 2.13 (1.16 – 3.93) | 0.013 |

| Total CTQ score (mean, SD)e | 51 (20) | 60 (22) | 49 (20) | 1.54 (1.17 – 2.03) | 0.003 |

Refers to the preceding six months

OR reported is per year increase in age

Has already completed or is currently enrolled in high school

Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression scale [8]

Childhood Trauma Questionnaire [6]

Figure 1.

Proportion of youth reporting types of abuse/neglect (n = 495). Error bars represent +/− 95% confidence intervals for the estimate.

Three variables met criteria for inclusion in the final logistic regression model: total CTQ score, age and recent sex trade involvement. A fourth, gender, was forced into the model. In the final model, total CTQ score strongly retained its significance (adjusted odds ratio [AOR], 1.45 per 20 point increase [i.e., one standard deviation increase in score]; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.08 – 1.91). Age additionally retained its significance (AOR, 1.13 per year older; 95% CI, 1.01 – 1.27). Notably, when depressive symptoms (CES-D score <22 vs. ≥22) were added to the logistic regression model, they were strongly associated with recent suicide attempt (AOR, 3.88; 95% CI, 1.87 – 8.05) and significantly reduced the effect of CTQ score on odds of suicide attempt (AOR, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.99 – 1.03), suggesting that depressive symptoms may mediate the effects of childhood trauma on attempted suicide. A formal Sobel test evaluating the role of depressive symptoms as a mediator of the relationship between childhood trauma and odds of attempted suicide was highly significant (p = 0.002) (Sobel, 1982).

DISCUSSION

Our results demonstrate that among street youth, a population marked by high rates of completed suicide (Roy et al., 2004), childhood trauma may predispose youth to attempted suicide during adolescence and early adulthood. Previous studies have been limited by an inability to establish temporality between childhood/adolescent trauma and subsequent suicidality (Dube et al., 2001). Our findings also support the role of depressive symptoms as a mediator of this relationship, although it remains unclear based on our results alone how depressive symptoms and attempted suicide are temporally related. Other limitations of our work include a reliance on self-report as well as on snowball sampling, a method that does not produce a truly random sample.

Genetic and environmental mediators of the relationship between childhood trauma and suicide are not yet fully elucidated (Duke et al., 2010). Evidence from neurodevelopmental studies suggest that abuse and neglect may lead to ‘hardwired’ cognitive and emotional changes that persist into adulthood (Lee and Hoaken, 2007). For example, autopsy studies of suicide victims with history of childhood maltreatment demonstrate altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal function relative to non-maltreated suicide victims, suggesting early neurodevelopmental changes in response to childhood trauma (McGowan et al., 2009). Such findings highlight the need for effective interventions that not only prevent maltreatment of children, but also provide appropriate services for youth who may be at increased risk for suicide given prior history of trauma.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the study participants for their contribution to the research, as well as current and past researchers and staff. We would specifically like to thank Deborah Graham, Peter Vann, Caitlin Johnston, Steve Kain, and Calvin Lai for their research and administrative assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Stokes J, Handelsman L, Medrano M, Desmond D, Zule W. Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse Negl. 2003;27:169–190. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(02)00541-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ, Chapman DP, Williamson DF, Giles WH. Childhood abuse, household dysfunction, and the risk of attempted suicide throughout the life span: findings from the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study. JAMA. 2001;286:3089–3096. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.24.3089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duke NN, Pettingell SL, McMorris BJ, Borowsky IW. Adolescent violence perpetration: associations with multiple types of adverse childhood experiences. Pediatrics. 2010;125:e778–786. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fast D, Small W, Wood E, Kerr T. Coming 'down here': Young people's reflections on becoming entrenched in a local drug scene. Soc Sci Med. 2009;21:21. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadland SE, Kerr T, Li K, Montaner JS, Wood E. Access to drug and alcohol treatment among a cohort of street-involved youth. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;101:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadland SE, Kerr T, Marshall BD, Small W, Lai C, Montaner JS, Wood E. Non-injection drug use patterns and history of injection among street youth. Eur Addict Res. 2010;16:91–98. doi: 10.1159/000279767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee V, Hoaken PN. Cognition, emotion, and neurobiological development: mediating the relation between maltreatment and aggression. Child Maltreat. 2007;12:281–298. doi: 10.1177/1077559507303778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGowan PO, Sasaki A, D'Alessio AC, Dymov S, Labonte B, Szyf M, Turecki G, Meaney MJ. Epigenetic regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor in human brain associates with childhood abuse. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:342–348. doi: 10.1038/nn.2270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The use of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale in adolescents and young adults. J Youth Adolesc. 1991;20:149–166. doi: 10.1007/BF01537606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roy E, Haley N, Leclerc P, Sochanski B, Boudreau JF, Boivin JF. Mortality in a cohort of street youth in Montreal. JAMA. 2004;292:569–574. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.5.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel ME. Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardt S, editor. Sociological methodology. Jossey-Bass Publishers; San Francisco, CA: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Street youth in Canada: findings from the enhanced surveillance of Canadian street youth, 1999–2003. Public Health Agency of Canada; Ottawa, ON: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Stoltz JA, Montaner JSG, Kerr T. Evaluating methamphetamine use and risks of injection initiation among street youth: the ARYS study. Harm Reduction Journal. 2006;3:18. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-3-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood E, Stoltz JA, Zhang R, Strathdee SA, Montaner JS, Kerr T. Circumstances of first crystal methamphetamine use and initiation of injection drug use among high-risk youth. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2008;27:270–276. doi: 10.1080/09595230801914750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]