Abstract

Background

Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia is a serious and life-threatening infection associated with high mortality. Among the multitude of virulence determinants possessed by P. aeruginosa, the type III secretion system (TTSS) has been implicated with more acute and invasive infection in respiratory diseases. However, the relationship between TTSS and clinical outcomes in P. aeruginosa bacteremia has not been investigated.

Objectives

To determine the association between the TTSS virulence factor in P. aeruginosa blood stream infection and 30-day mortality.

Design

Retrospective analysis of 85 cases of P. aeruginosa bacteremia.

Setting

Tertiary care hospital.

Interventions

Bacterial isolates were assayed in vitro for secretion of type III exotoxins (ExoU, ExoT, and ExoS). Strain-relatedness was analyzed using randomly amplified polymorphic DNA PCR genotyping. Antimicrobial susceptibilities were determined by means of the Kirby-Bauer disk-diffusion test.

Measurements and Main results

At least one of the TTSS proteins was detected in 37 out of the 85 isolates (44%). Septic shock was identified in 43% of bacteremic patients with TTSS+ isolates compared to 23% of patients with TTSS− isolates (p=0.12). A high frequency of resistance in the TTSS+ isolates was observed to ciprofloxacin (59%), cefipime (35%), and gentamycin (38%). There was a significant difference in the 30-day cumulative probability of death after bacteremia between secretors and nonsecretors (p=0.02). None of the TTSS+ patients who survived the first 30 days had a P. aeruginosa isolate which exhibited ExoU phenotype.

Conclusions

The expression of TTSS exotoxins in bacteremic isolates of P. aeruginosa confers poor clinical outcomes independent of antibiotic susceptibility profile.

Keywords: Type III secretion system, blood stream infection, Pseudomonas, shock, mortality, antimicrobial resistance

INTRODUCTION

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a ubiquitous aerobic Gram-negative organism that rarely causes disease in healthy individuals. However, Pseudomonas aeruginosa is a common cause of infection in hospitalized patients accounting for 11–14% of all nosocomial infections (1–3), including pneumonias, urinary tract infections, and postoperative wound infections. P. aeruginosa ranks third after Escherichia coli and Klebsiella species among Gram negative bacteria isolated during nosocomial blood stream infections and seventh among all pathogens (1). Despite improvements in hospital care, the prognosis of P. aeruginosa bacteremia remains poor with a crude mortality ranging between 33% to 61% (4, 5).

The identification of prognostic factors, potentially influencing the mortality of P. aeruginosa bacteremia, is essential in order to decide whether a subgroup of patients might deserve a particularly aggressive therapeutic approach. Evidence derived from clinical investigations indicates that septic shock, initial site of infection, and immunosuppression at the time of P. aeruginosa bacteremia are considered risk factors for mortality (6–8). A key determinant of P. aeruginosa pathogenicity is its ability to deliver a number of toxins into host cells via a type III secretion system (TTSS) (9). The system uses a complex secretion and translocation machinery to inject a set of exotoxins directly into the cytoplasm of eukaryotic cells. Four effector proteins have been identified: ExoU, a phospholipase; ExoY, an adenylate cyclase; and ExoT and ExoS, which are bifunctional proteins (10, 11). Although all strains harbor type III protein secretory genes, only few of these are capable of secreting effector proteins (12). The expression of the type III secretion system in P. aeruginosa isolates has been associated with higher bacterial burden and increased mortality in patients with lower respiratory tract infections (13, 14). To date, no study to our knowledge has investigated the impact of type III phenotypic expression on clinical outcomes of P. aeruginosa bloodstream infection. We hypothesized that the production of type III secretory proteins is associated with poor outcomes in P. aeruginosa bacteremia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study population

The study was conducted at the VA Western New York Healthcare System, a tertiary care facility affiliated with the State University of New York at Buffalo following approval by the Institutional Review Board. A retrospective cohort study was established based on P. aeruginosa blood isolates that were stored in a databank from a city wide surveillance initiative implemented in 2004. All corresponding adult patients admitted to the study hospital between January 2004 and June 2010 were identified from the Computerized Patient Record System. Patients with polymicrobial bloodstream infection defined as the isolation of 2 or more different organisms from the same blood culture were excluded. Patients were included only once in the database to ensure independence of observation. Among those with multiple bacteremic episodes, only the first event was analyzed.

The cohort database included information on sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, race, and residence), comorbidities, prior antibiotic therapy, severity of illness, source of bacteremia according to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention criteria (15), choice and dose of antibiotics used, time to first dose of antimicrobial therapy, use of corticosteroids and other immunosuppressive agent.

Bacterial isolates

P. aeruginosa clinical specimens, including the reference strains PA01 and PA103, were streaked onto trypticase soy agar plates and grown in a deferrated dialysate of tripticase soy broth supplemented with 10 mM nitrilotriacetic acid (Sigma Chemicals), 1% glycerol and 100 mM monosodium glutamate at 37°C for 17 h in a shaking incubator at 250 rpm. Bacteria were removed by centrifugation at 8500 x g for 5 min, after which the supernatant was collected and concentrated 20-fold by the addition of a saturated solution of ammonium sulfate.

Immunoblot analysis

Standardized protein concentrations for the cell-free supernatant were loaded onto 12.5% Tris polyacrylamide gels (Biorad; Hercules, CA) and run under denaturing conditions. Polyacrylamide gels were transferred to PVDF membrane and immunoblotted with polyclonal rabbit antiserum against ExoU, ExoT, and ExoS as previously described (16).

PCR genotyping

The clonality of P. aeruginosa isolates was determined using randomly amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) PCR genotyping as previously described (16).

Susceptibility profile

Antimicrobial susceptibilities of P. aeruginosa isolates were determined by means of the Kirby-Bauer disk-diffusion test on Mueller-Hinton agar (BBL Microbiologic System, Cockeysville, MD) for imipenem, piperacillin-tazobactam, cefipime, gentamycin, amikacin, and ciprofloxacin. Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) breakpoints and quality-control protocols were used according to standards established by the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (17). Isolates with intermediate susceptibility were classified as resistant for analysis.

Definitions

Isolates that secreted type III proteins (ExoU, ExoS, ExoT) were referred to as type III secretion positive (TTSS+) isolates, and isolates that did not secrete these proteins were referred to as type III secretion negative (TTSS−). P. aeruginosa bacteremia met the CDC criteria for infection (15). Shock was defined as a decrease in systolic blood pressure to a level of less than 90 mm Hg or a decrease of at least 40 mm Hg below baseline blood pressure, despite adequate fluid resuscitation, in conjunction with organ dysfunction and perfusion abnormalities (18). Severity of illness was determined in accordance with the Acute Physiologic and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II (19). The burden of comorbidities was assessed by the Charslon Index (20).

All patients with septic shock were treated according to a standardized protocol that combined early goal-directed therapy, prompt initiation and appropriate dosing of antimicrobial therapy, hydrocortisone supplementation in stress doses, and an evaluation for drotrecogin alfa infusion. Antimicrobial therapy was judged to be either adequate or inadequate on the basis of the in-vitro susceptibility of an isolated organism. Patients were considered to have prior antibiotic therapy if they have received an antimicrobial agent for at least 2 days within 30 days preceding onset of Pseudomonas bacteremia. Recurrent P. aeruginosa bacteremia was defined as P. aeruginosa bacteremia occurring within 30 days after completion of 14 days of adequate antimicrobial therapy. Reinfection was defined as the isolation of a P. aeruginosa strain that is genetically distinct from the initial strain isolated from blood culture. Overall mortality and invasive ventilation-free days was calculated in the first 30 days after the first positive blood culture. Survival of patients with multiple episodes of bacteremia was assessed at day 30 from the onset of bacteremia irrespective of the results of subsequent blood cultures.

Statistical analysis

All analyses of patients were performed by investigators, without knowledge of in vitro susceptibility results. SPSS 15.0 (SPPS Inc., Cary, NC) was used for all statistical comparisons. The alpha level for significance was set at < 0.05. Continuous variables were analyzed using a two-tailed student's- t-test for normally distributed variables and the Mann–Whitney test for non-normally distributed variables. Means and standard deviations (SDs) are presented for normal data and medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) for non-normally distributed data. Proportions were compared using the Chi-square test with Yates correction or Fisher's exact test when necessary. The relationship between pseudomonal bacteremia and the outcome variables was investigated by a Cox proportional hazard model. All biologically plausible variables with a p value of <0.20 in the bivariable analysis were considered for inclusion in the final multivariable regression models. A multicollinearity test was performed using the variance inflation factor to assess the degree of correlation between independent variables. A Kaplan-Meier product-limit method was used to estimate by univariate analysis the risk of death by presence of virulence factors in those who received adequate therapy. The cumulative probability of death across treatment groups was compared by the log-rank test.

RESULTS

Study population

During the study period, a total of 89 patients with P. aeruginosa bacteremia were identified. Four patients were excluded from analysis due to polymicrobial blood stream infection leaving 85 cases for analysis. Thirty seven patients (44%) had a P. aeruginosa isolate with at least one of the type III secretory proteins detected while 48 patients (56%) were infected with isolates that did not express any of the type III secretory proteins. Table 1 displays the clinical characteristics of the study population. There were no significant differences in age, gender, underlying comorbidities, or in primary sites of infection between patients with TTSS+ and TTSS− isolates. Similarly, vital signs and laboratory parameters of the TTSS+ and TTSS− groups were comparable at the time the blood cultures were obtained (Table 2). The median time from admission to culture positive was 2.0 days in both groups (p=0.89). Septic shock was identified in 43% of bacteremic patients with TTSS+ isolates compared to 23% of patients with TTSS− isolates (p=0.12). Although the need for vasopressors were similar in both groups, patients with TTS+ isolates required a higher dose of norepinephrine in the first 48 hours of onset of septic shock than those with TTSS− isolates (p=0.02). Vasopressin and hydrocortisone were also prescribed more often in the TTSS+ compared to the TTSS− group but the difference did not attain statistical significance (p=0.08 and p=0.09; respectively).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

| TTSS (+) (n=37) | TTSS (−) (n=48) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 72.2±13.3 | 70.8±9.1 | 0.58 |

| Gender (M/F) | 34/3 | 47/1 | 0.31 |

| Underlying disease, n(%) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 16 (43) | 18 (38) | 0.76 |

| Malignancy | 7 (19) | 11 (23) | 0.85 |

| End-stage renal disease | 8 (21) | 14 (29) | 0.59 |

| Hemiplegia | 4 (11) | 1 (2) | 0.16 |

| Immunosuppression | 9 (24) | 6 (13) | 0.28 |

| Charlson Index | 4.4±2.3 | 3.8±1.5 | 0.48 |

| Source of infection, n(%) | |||

| Respiratory | 11 (29) | 7 (17) | 0.15 |

| Urinary | 3 (8) | 1 (2) | 0.31 |

| Abdominal | 5 (14) | 9 (19) | 0.72 |

| Soft-tissue | 1 (3) | 5 (11) | 0.23 |

| Catheter | 4 (11) | 11 (23) | 0.24 |

| Unknown | 13 (35) | 15 (29) | 0.89 |

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics of the study population

| TTSS (+) (n=37) | TTSS (−) (n=48) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vital signs | |||

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 106±23 | 113±30 | 0.16 |

| Temperature, °F | 100.5±2.3 | 99.9±2.1 | 0.37 |

| Baseline laboratory values | |||

| White blood cells, 109/L | 13.8±7.3 | 12.7±7.6 | 0.57 |

| Blood glucose, mg/dl | 180±119 | 195±135 | 0.48 |

| Creatinine, mg/dl | 1.7±1.1 | 1.6±0.9 | 0.79 |

| Lactate, mmol/L | 3.7±3.1 | 3.4±2.6 | 0.63 |

| Arterial pH | 7.32±0.11 | 7.35±0.09 | 0.28 |

| APACHE II score | 24.5±5.6 | 23.3±4.8 | 0.23 |

| Therapeutic intervention | |||

| Mechanical ventilation, n (%) | 17 (46) | 19 (39) | 0.71 |

| Need for vasopressors, n (%) | 16 (43) | 12 (25) | 0.12 |

| Norepinephrine dose in the first 48 hours, μg/kg/min | 0.28±0.14 | 0.19±0.11 | 0.02 |

| Hydrocortisone, n (%) | 14 (38) | 9 (19) | 0.09 |

| Vasopressin, n (%) | 14 (37) | 11 (23) | 0.21 |

| Adequate antibiotics, n (%) | 34 (92%) | 44 (91%) | 0.73 |

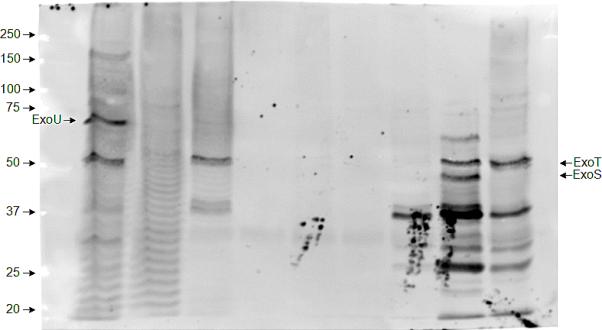

Characterization of type III secretory protein phenotype

Figure 1 displays the immunoblot analysis of the of the type III secretion phenotypes in representative samples of P. aeruginosa isolates. The ExoU/ExoT phenotype was the most prevalent among all TTSS+ isolates and was detected in 18 out of 37 isolates (49%) while the ExoT/ExoS was found in 8 (22%). Of the 37 isolates, 9 (24%) expressed ExoT alone while 2 (5%) expressed ExoS with no other exotoxins. None of the isolates expressed ExoU alone. Isolates that excreted ExoU did not release ExoS and vice versa. No significant association was found between the suspected focus of infection and the ability to secrete exotoxins although a higher frequency of ExoU/ExoT was noted in isolates derived from a suspected respiratory source (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Immunoblot analysis showing the type III protein secretion phenotypes of representative P. aeruginosa isolates. Individual isolates were grown under conditions that induced type III protein secretion. Immunoblot analysis was then performed on culture supernatants using a mixture of antisera against type III exotoxins.

Table 3.

Distribution of type III secretion phenotypes according to suspected sites of infection

| Phenotype | Respiratory | Abdominal | Urinary | Soft tissue | Catheter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ExoT | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| ExoS | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| ExoU/ExoT | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 |

| ExoS/ExoT | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

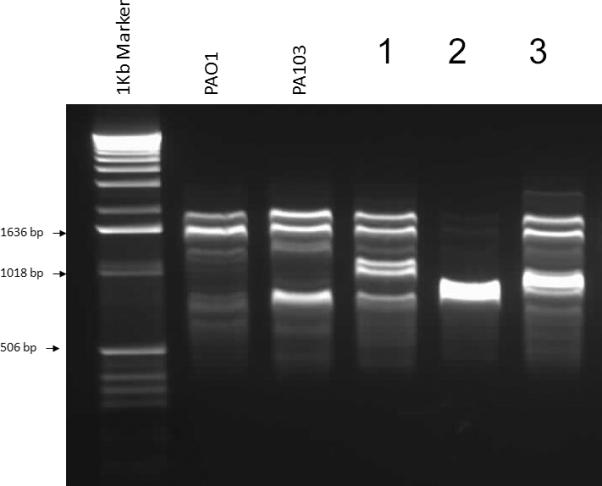

Figure 2 depicts DNA genotyping of representative P. aeruginosa isolates by repetitive-element-based polymerase chain reaction assay. The corresponding RAPD profiles for the type III secretory phenotypes are shown in table 4. Overall, there were 67 different RAPD fingerprints, 53 of which contained only one strain. The other 14 RAPD fingerprints had either clonal (n=6) or closely related stains (n=8). Strain relatedness was not associated with any particular secretory phenotype or time of bacteremia onset. There was also no correlation between the presumed focus of bacteremia and RAPD grouping.

Figure 2.

DNA genotyping of representative Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates by repetitive-element-based polymerase chain reaction assay. Samples with identical banding patterns were considered to be related and assigned a single RAPD type. Samples with patterns that differed by one band were considered possibly related. Samples that differed by two or more bands were considered unrelated.

Table 4.

RAPD analysis of P. aeruginosa isolates

| Secretion Phenotype | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | ExoS+ | ExoT+ | ExoU+ ExoT+ | ExoT+ ExoS+ | |||

| Profile Type | Unique | 24 | 1 | 7 | 13 | 6 | |

| P1 | P1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| P1a | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| P2 | P2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | |

| P2a | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | ||

| P2b | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| P3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| P4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | ||

| P5 | P5 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| P5a | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| P6 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| P7 | P7 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| P7a | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| P8 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| P9 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| P10 | P10 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | |

| P10a | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| P11 | P11 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| P11a | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| P12 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| P13 | P13 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| P13a | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| P14 | P14 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| P14a | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | ||

Lowercase letter indicates isolate differs from profile type by 1 band (possibly related)

Antimicrobial therapy

Forty eight patients had previous exposure to antimicrobial therapy. Of those, 65% with TTSS+ isolates and 50% with TTS− isolates had at least two days of antibiotics in the preceding 30 days of P. aeruginosa bacteremia (p=0.25). Vancomycin (39%) and ciprofloxacin (24%) were the most commonly prescribed antibiotics in the TTSS+ group while ciprofloxacin (21%) and cephalosporin (19%) accounted for the majority of prior antimicrobial therapy in TTSS− patients. There were no discernable differences in the prescription pattern of antibiotics between the two groups.

The average time to first antibiotic dose from a reported positive blood culture was 4.3±1.2 hours. Empiric monotherapy for Gram negative organisms was prescribed for 17 (46%) and 28 (58%) of the TTSS+ and the TTSS− groups, respectively; (p=0.36). Piperacillin/tazobactam was the predominant agent used in both groups (n=49), followed by ciprofloxacin (n=19) and cefipime (n=13). Combination therapy consisted mainly of piperacillin/tazobactam plus ciprofloxacin (n=12), and imipenem plus gentamycin (n=6). Overall, fifteen (18%) out of 85 patients received inadequate antimicrobial therapy. Two patients in the TTS+ and four patients in the TTSS− received no initial Gram-negative antibiotics directed against P. aeruginosa blood stream infection. The remaining nine were treated with antibiotics having recognized activity against P. aeruginosa but for which the bacteria were actually resistant by in vitro susceptibility testing.

The antimicrobial resistance profile of P. aeruginosa isolates are shown in Table 5. Fifty seven percent of isolates with TTSS+ phenotypes were resistant to two or more antimicrobial agents compared to 15% of TTSS− phenotype (p<0.001). A higher frequency of resistance in the TTSS+ isolates was observed to ciprofloxacin (59%), cefipime (35%), and gentamycin (38%) compared to TTSS− isolates. Pipercallin/tazobactam had the least antimicrobial resistance in both groups. ExoU secretory phenotype was present in 11 out of 22 (50%) of ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates and in 9 out of 14 (64%) gentamicin-resistant isolates. In comparison, ExoS was identified in 5 (23%) of ciprofloxacin-resistant isolates and in one of 14 (7%) gentamicin-resistant isolates.

Table 5.

Antimicrobial resistance pattern of P. aeruginosa isolates

| Antibiotics, n (%) | TTSS (+) (n=37) | TTSS (−) (n=48) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Piperacillin/tazobactam | 2 (5) | 0 | 0.19 |

| Cefipime | 13 (35) | 7 (15) | 0.05 |

| Imipenem-cilastatin | 3 (8) | 6 (13) | 0.72 |

| Ciprofloxacin | 22 (59) | 2 (4) | <0.001 |

| Gentamycin | 14 (38) | 6 (13) | 0.01 |

| Amikacin | 2 (5) | 3 (6) | 1.0 |

Hospital course and outcome

During the course of hospitalization, 6 patients had recurrent P. aeruginosa bacteremia (Table 6). The average time between the primary and secondary blood stream infection isolates was 31±10 days. All recurrent P. aeruginosa isolates were considered reinfection due to genetically distinct profile from the initial bacteremic isolates. There was no correlation between recurrence of bacteremia and secretory phenotypes.

Table 6.

Recurrent P. aeruginosa bacteremia

| Primary isolate | Secondary isolate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient | RAPD Profile | Secretion Phenotype | Time to second positive blood culture (days) | RAPD Profile | Secretion Phenotype |

| 1 | U | ExoT/ExoS | 26 | U | none |

| 2 | U | none | 42 | P7 | none |

| 3 | P11 | none | 44 | P8 | none |

| 4 | P3 | none | 23 | P5 | none |

| 5 | U | none | 29 | U | none |

| 6 | U | none | 19 | P1 | none |

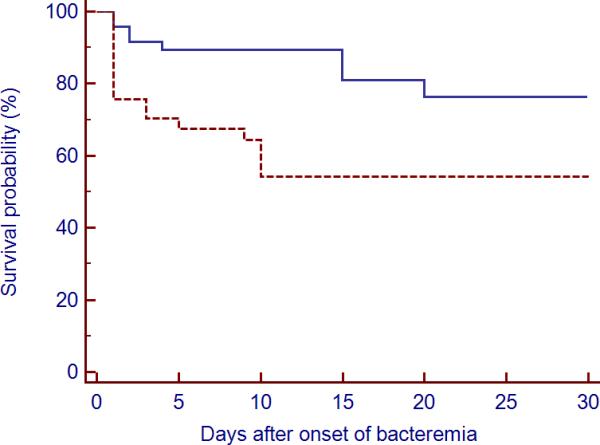

U= Unique profile

The overall 30-day crude mortality was 32%. The 30-day and in-hospital mortality rates among patients with P. aeruginosa isolates that expressed TTSS+ protein were 46% and 57% compared with 21% and 25% among patients whose P. aeruginosa did not express any of the exotoxins (p=0.03 and 0.006; respectively). The survival curve also shows significant differences in the first 30-day cumulative probability of death after bacteremia between secretors and nonsecretors (p=0.02) (Figure 3). All TTSS+ patients who did not survive 30 days exhibited ExoU and/or ExoT phenotypes while none of the TTSS+ patients who survived the first 30 days had a P. aeruginosa isolate with ExoU phenotype. There was a trend toward higher ventilator-free days in the TTSS− group compared to the TTSS+ group (22.7±17.9 versus 17.3±13.6 days) but the difference did not reach statistical significance (p=0.09). Further, inadequate antimicrobial therapy was associated with worse 30-day outcome than those who had appropriate therapy irrespective of the TTSS phenotype (23% versus 4%, respectively; p=0.03). Cox regression analysis identified APACHE II, the presence of TTSS phenotypes and inadequate antimicrobial therapy as independent risk factors for 30-day mortality (Hazard ratio 2.6 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.1–6.2, 2.9 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.3–6.7) and 3.1 (95% CI 1.2–7.5), respectively) (Table 7).

Figure 3.

Kaplan-Meier probability estimate for 30-day mortality of P. aeruginosa bacteremia according to type III secretion phenotype. The broken line represents patients with bacteremia caused by P. aeruginosa type III secretion phenotype; the solid line represents patients with bacteremia caused by type III non secretory phenotype.

Table 7.

Cox regression analysis of 30-day mortality

| Covariate | b | SE | P value | HR | 95% CI of HR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APACHE II | 0.9683 | 0.4432 | 0.0289 | 2.6336 | 1.1097 to 6.2498 |

| Prior antibiotics | 0.6561 | 1.0340 | 0.5258 | 1.9272 | 0.2566 to 14.4754 |

| TTSS+ | 1.0669 | 0.4254 | 0.0121 | 2.9064 | 1.2680 to 6.6618 |

| Inadequate therapy | 1.1174 | 0.4606 | 0.0153 | 3.0568 | 1.2450 to 7.5054 |

SE=Standard error

HR= Hazard ratio

CI = Confidence interval

b = coefficient of covariates

DISCUSSION

The results of our study demonstrated that: 1) the prevalence of TTSS+ phenotype in P. aeruginosa bacteremia is common, with ExoU/ExoT representing the predominant phenotype; 2) there is a high association between antimicrobial resistance and TTSS+ phenotypes; and 3) type III protein secretion is associated with increased 30-day mortality in P. aeruginosa bacteremia.

Our investigation showed a prevalence of 44% of TTSS+ isolates in our study population based on the excretion of ExoU, ExoT, and ExoS. We have not investigated the presence of PcrV, PopB, or PopD because previous reports documented a lack of cytotoxity of these proteins per se when tested in vitro (21, 22). The proportion of TTSS+ strains that exhibited exoU (48%) was higher than that reported by Berthelot et al(21) (28%) but close to that observed by Wareham et al. (23) (40%). In contrast, the secretion of ExoS (27%) was lower than the reported rate of 52% in the study by Barthelot et al. (21) This wide range of prevalence among bacteremic P. aeruginosa isolates with the type III secretory proteins may be difficult to elucidate in the absence of a surveillance database. However, the almost ubiquitous presence of exoU+ and exoS+ genes in P. aeruginosa blood stream isolates (24) suggests that the system is modulated by environmental cues that trigger the expression of TTSS genes. Unfortunately, further advance in this field is limited by the fact that TTSS expression is induced ex-vivo through manipulation of the external milieu and not assessed in vivo. The use of in vivo gene expression technologies (25) may hold promise in accurately determining the spatial and temporal control of these impressively complex regulatory cascades.

Previous studies have linked multidrug resistance in P. aeruginosa to TTSS phenotypes in ocular, blood, urine, and wound isolates (26, 27). Wong-Beringer and colleagues (27) studied this association by concentrating on fluoroquinolone-resistant clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa. Compared with exoS+ isolates, exoU+ isolates were more likely to be fluoroquinolone-resistant and to exhibit both a gyrA mutation and the efflux pump over-expressed phenotype. More importantly, almost all exoU+ strains secreted ExoU. Although we have not performed a genotypic analysis, our results are in agreement with these observations which suggest a co-selection of fluoroquinolone resistance and enhanced TTSS virulence in isolates harboring exoU+. We noted also a high frequency of resistance for gentamicin among isolates secreting ExoU but not for ExoS. This resistance appears to be drug-specific rather than class-specific as the susceptibility to amikacin was not altered by the presence of the TTSS phenotypes.

Other investigators have demonstrated that the source of bacteremia, inadequate antimicrobial therapy, and severity of illness at the time of bacteremia are associated with a poor prognosis in P. aeruginosa infection (7, 28–30). Our study suggests that type III secretory phenotype should be added to the growing list of factors responsible for increased mortality from P. aeruginosa bloodstream infection. The presence of a functional TTSS has already been linked to bacterial persistence in the lungs, higher relapse rates, and increased mortality in patients with acute respiratory infections (13, 16, 31). Furthermore, secretion of type III proteins was associated with increased mortality in patients with a high bacterial burden in respiratory secretions but who failed to meet clinical criteria for the diagnosis of ventilator associated pneumonia(14). This is further substantiated in our study by the fact that despite adequate antimicrobial therapy for both TTSS+ and TTSS− groups initially, patient with TTSS+ phenotype had a worse prognosis, most notably during the first few days. The same observation was reported in a retrospective analysis of 115 P. aeruginosa bloodstream infections (7). The adequacy of the initial therapy did not influence survival up to receipt of the antibiogram. However, after censoring those patients that died during the first days, the risk of death for inadequate empirical treatment was significantly higher from the date of receipt of the antibiogram to day 30. Chamot et al. (7) did not examine the phenotype of these isolates but altogether these results suggest that a subpopulation of patients will die from P. aeruginosa bloodstream infection independently of their treatment. However, adequacy of empirical antimicrobial treatment influences the outcome of those patients that survive the first days following P. aeruginosa bloodstream infection.

There are several limitations to the present study that should be noted. First, we acknowledge the limitation of the retrospective design of the study which might introduce bias that we are unable to adjust for using the collected indices. Despite the presence of protocol-driven ICU management, changes in disease patterns and treatment strategies over the study period may have generated a time bias in our analysis favoring late participants. It is increasingly recognized that outcomes also depend on a variety of clinical and nonclinical factors that are not measured and therefore cannot be adjusted for in the available models. Second, the P. aeruginosa blood culture data were collected from a single site; institutional differences in prescribing patterns, antibiotic formularies, and patient populations may affect the applicability of these results to other institutions. Third, we cannot exclude the possibility that a number of strains classified as TTSS− phenotype may exhibit type III secretory phenotypes based on the release of PcrV. These strains are however less virulent in vitro than those responsible for excretion of ExoU, ExoS, or ExoT (21). Fourth, we have not assessed the expression of other virulence factors that may be co-expressed with TTSS phenotype.

In conclusion, expression of the type III phenotype confers an increased virulence in P. aeruginosa bacteremia. The association between ExoU phenotype and fluoroquinolone resistance needs to entail a prescription pattern that provides adequate coverage for suspected P. aeruginosa bacteremia in accordance with the local susceptibility profile. Interference with TTS function by chemical or biological inhibition and vaccination has great potential to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with infection with these pathogens.

Acknowledgments

Research grants: The study was partially supported by NIH R01AI053674 (ARH)

Dr. Hauser received funding from the NIH, and consulted for Microbiotix, Inc.

Footnotes

The remaining authors have not disclosed any potential conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Wisplinghoff H, Bischoff T, Tallent SM, et al. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(3):309–317. doi: 10.1086/421946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pittet D, Harbarth S, Ruef C, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for nosocomial infections in four university hospitals in Switzerland. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20(1):37–42. doi: 10.1086/501554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim JM, Park ES, Jeong JS, et al. Multicenter surveillance study for nosocomial infections in major hospitals in Korea. Nosocomial Infection Surveillance Committee of the Korean Society for Nosocomial Infection Control. Am J Infect Control. 2000;28(6):454–458. doi: 10.1067/mic.2000.107592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lodise TP, Jr., Patel N, Kwa A, et al. Predictors of 30-day mortality among patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infections: impact of delayed appropriate antibiotic selection. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(10):3510–3515. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00338-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vidal F, Mensa J, Almela M, et al. Epidemiology and outcome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia, with special emphasis on the influence of antibiotic treatment. Analysis of 189 episodes. Arch Intern Med. 1996;156(18):2121–2126. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang CI, Kim SH, Kim HB, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia: risk factors for mortality and influence of delayed receipt of effective antimicrobial therapy on clinical outcome. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37(6):745–751. doi: 10.1086/377200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chamot E, Boffi El Amari E, Rohner P, et al. Effectiveness of combination antimicrobial therapy for Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47(9):2756–2764. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.9.2756-2764.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheong HS, Kang CI, Wi YM, et al. Clinical significance and predictors of community-onset Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia. Am J Med. 2008;121(8):709–714. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma Q, Zhai Y, Schneider JC, et al. Protein secretion systems of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and P fluorescens. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1611(1–2):223–233. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(03)00059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frank DW. The exoenzyme S regulon of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26(4):621–629. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6251991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sato H, Frank DW. ExoU is a potent intracellular phospholipase. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53(5):1279–1290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feltman H, Schulert G, Khan S, et al. Prevalence of type III secretion genes in clinical and environmental isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microbiology. 2001;147(Pt 10):2659–2669. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-10-2659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hauser AR, Cobb E, Bodi M, et al. Type III protein secretion is associated with poor clinical outcomes in patients with ventilator-associated pneumonia caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Crit Care Med. 2002;30(3):521–528. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhuo H, Yang K, Lynch SV, et al. Increased mortality of ventilated patients with endotracheal Pseudomonas aeruginosa without clinical signs of infection. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(9):2495–2503. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318183f3f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garner JS, Jarvis WR, Emori TG, et al. CDC definitions for nosocomial infections, 1988. Am J Infect Control. 1988;16(3):128–140. doi: 10.1016/0196-6553(88)90053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El Solh AA, Akinnusi ME, Wiener-Kronish JP, et al. Persistent infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa in ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(5):513–519. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-239OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Institute CaLS . Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levy MM, Fink MP, Marshall JC, et al. 2001 SCCM/ESICM/ACCP/ATS/SIS International Sepsis Definitions Conference. Crit Care Med. 2003;31(4):1250–1256. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000050454.01978.3B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knaus WA, Draper EA, Wagner DP, et al. APACHE II: a severity of disease classification system. Crit Care Med. 1985;13(10):818–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berthelot P, Attree I, Plesiat P, et al. Genotypic and phenotypic analysis of type III secretion system in a cohort of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia isolates: evidence for a possible association between O serotypes and exo genes. J Infect Dis. 2003;188(4):512–518. doi: 10.1086/377000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schoehn G, Di Guilmi AM, Lemaire D, et al. Oligomerization of type III secretion proteins PopB and PopD precedes pore formation in Pseudomonas. EMBO J. 2003;22(19):4957–4967. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wareham DW, Curtis MA. A genotypic and phenotypic comparison of type III secretion profiles of Pseudomonas aeruginosa cystic fibrosis and bacteremia isolates. Int J Med Microbiol. 2007;297(4):227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Garey KW, Vo QP, Larocco MT, et al. Prevalence of type III secretion protein exoenzymes and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns from bloodstream isolates of patients with Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia. J Chemother. 2008;20(6):714–720. doi: 10.1179/joc.2008.20.6.714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hautefort I, Hinton JC. Measurement of bacterial gene expression in vivo. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2000;355(1397):601–611. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2000.0601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu H, Conibear TC, Bandara R, et al. Type III secretion system-associated toxins, proteases, serotypes, and antibiotic resistance of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates associated with keratitis. Curr Eye Res. 2006;31(4):297–306. doi: 10.1080/02713680500536746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong-Beringer A, Wiener-Kronish J, Lynch S, et al. Comparison of type III secretion system virulence among fluoroquinolone-susceptible and -resistant clinical isolates of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2008;14(4):330–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2007.01939.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kang CI, Kim SH, Park WB, et al. Risk factors for antimicrobial resistance and influence of resistance on mortality in patients with bloodstream infection caused by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Microb Drug Resist. 2005;11(1):68–74. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2005.11.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuikka A, Valtonen VV. Factors associated with improved outcome of Pseudomonas aeruginosa bacteremia in a Finnish university hospital. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1998;17(10):701–708. doi: 10.1007/s100960050164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Micek ST, Lloyd AE, Ritchie DJ, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa bloodstream infection: importance of appropriate initial antimicrobial treatment. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(4):1306–1311. doi: 10.1128/AAC.49.4.1306-1311.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roy-Burman A, Savel RH, Racine S, et al. Type III protein secretion is associated with death in lower respiratory and systemic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections. J Infect Dis. 2001;183(12):1767–1774. doi: 10.1086/320737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]