Introduction

Acute cardiac events such as myocardial infarction, heart failure, and intracoronary artery procedures affect over two million individuals in the United States each year and over half of these individuals are over the age of 65.1 Also common in older adults are cardiac surgical procedures such as coronary artery bypass and valve surgery.2 Advances in the treatment of cardiac events and surgical procedures have resulted in older and sicker patients surviving. 3, 4 These older patients are challenged with a difficult recovery after hospitalization due to the concomitant occurrence of comorbidity, frailty, and restricted activity during the hospital stay..5–7 The consequence is that older adults after cardiac events often require additional post-acute rehabilitation at a skilled nursing facility (SNF).

The rate of hospital discharges to SNF is steadily increasing in the Medicare population.8 Specifically for older cardiac patients, approximately 30% of myocardial infarction, 25% of heart failure, 11% of coronary artery bypass surgery, and 20% of valve surgery patients use SNF care.9 Medicare A reimburses 100% of SNF services for the first 20 days if a patient qualifies with a skilled need.10 Patients qualify if a physician certifies that they need either skilled nursing care (e.g., intravenous medication, extensive wound care) or additional physical, occupational, or speech therapy. SNF services are based on a geriatric rehabilitation model that enhances independence in mobility and activities of daily living. Skilled services include continuous nursing care, observation and assessment of the patient’s changing condition, ongoing assessment of rehabilitation needs and potential, therapeutic exercises or activities, and gait evaluation and training.10, 11 Physical and occupational rehabilitation services are delivered once per day.

Although these skilled services assist the patient in regaining functional abilities, other services are needed to assist patients and their families with specific cardiac rehabilitation to ensure optimal recovery. The American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation (AACVPR) recommends the integration of cardiac specific rehabilitation components (exercise and education) into post-acute care to ensure safe and comprehensive cardiac care.1 For exercise, cardiac specific care includes risk stratification, monitoring the cardiac response to exercise, and endurance training. Categorization of patients into risk categories (low, intermediate and high) is important to understand the patient’s risk of ventricular arrhythmias and hemodynamic instability with exercise. Monitoring the cardiac response to therapy (exercise) is important to detect hemodynamic changes that indicate that a patient is not tolerating the therapy. Endurance training is important in both traditional SNF rehabilitation and cardiac specific care; but cardiac patients need to understand that exercise will not only improve their functional status, but also will improve their cardiac condition. Cardiac patients need a plan to continue training for cardiac health. Cardiac specific education also is recommended to ensure that patients and families are able to self-manage their chronic disease when they return home. Education on self-management of cardiac symptoms, (e.g. knowing what to do if they get short of breath with activity or have heart palpitations), survival management (e.g. knowing what to do if they get chest pain), and education on the importance of attending outpatient rehabilitation are important goals.1

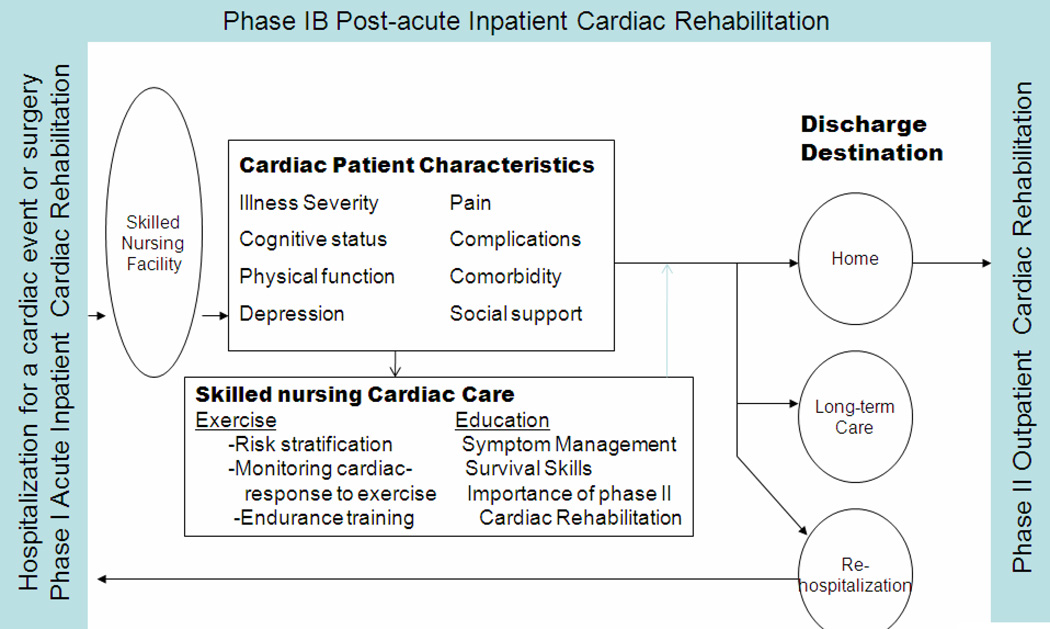

The Skilled Nursing Facility Cardiac Care Model was developed to guide the understanding of how cardiac care of the SNF patient fits into the current cardiac rehabilitation model (Figure 1). Current cardiac rehabilitation includes acute inpatient services (referred to as Phase I and is not reimbursed by Medicare), sub-acute inpatient (referred to as Phase IB and is not reimbursed by Medicare), and outpatient (referred to as Phase II, begins 2–3 weeks after hospitalization for a cardiac event, and is reimbursed by Medicare).12 Phase IB cardiac rehabilitation programs have been developed and tested to address patients who need a longer rehabilitation program in an inpatient setting such as a SNF.12–14 The SNF Cardiac Care Model includes patient characteristics that are important to consider in determining eligibility for the cardiac care services delivered in the SNF. The patient characteristics related to successful rehabilitation and discharge home include illness severity, cognitive status, physical function, depression, pain, complications, comorbidity, and social support as these characteristics impact rehabilitation success.9, 15 Specific cardiac care to include during a SNF stay includes exercise (risk stratification, monitoring the cardiac response to exercise, and incorporation of endurance training) and education (management of cardiac symptoms, survival management, and discussion of outpatient cardiac rehabilitation).1 These cardiac care services are consistent with the goals and services delivered in traditional SNF care. The SNF Cardiac Care Model also incorporates the discharge destination of patients who use SNF care in order to highlight the trajectory of patients through the system. The purpose of this research is to describe the characteristics of patients in SNF following a cardiac event and the current cardiac care delivered during SNF and will include: 1) the demographics and characteristics of their condition, 2) the percent eligible to participate in cardiac rehabilitation, 3) the discharge destination, and 4) the current cardiac care delivered.

Figure 1.

Skilled nursing facility cardiac care Model

Methods

This exploratory study employed a retrospective and cross-sectional design. In phase 1, the medical records were examined of patients admitted to one of two large tertiary hospital-based SNFs, and in phase 2 a questionnaire was completed by healthcare professionals working in these facilities to validate the results found in the medical record review. Both phases of the study (the medical record review and staff questionnaires) were approved by the institutional review boards from each hospital-based SNF. Staff gave verbal consent to participate.

Phase 1: Medical Record Review Procedure

This was a convenience sample of 80 consecutive medical records of patients who met the following inclusion criteria: age 65 and older admitted to a hospital-based SNF following discharge from the hospital for a cardiac event. There were no exclusion criteria. A cardiac event was defined as a hospitalization for a myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass graft, heart failure, valve surgery, or intracoronary intervention. Records meeting the inclusion criteria were identified by medical records specialists between January 1 2008 and December 31, 2008. Data were abstracted from both SNF and hospital medical records. Data included demographics, insurance type, SNF discharge destination, type of cardiac event, length of stay, and number of medications.

Data were collected on cardiac illness severity that included conditions that are potential contraindications to exercise. These conditions are unstable angina, uncompensated heart failure, uncontrolled arrhythmias, severe aortic stenosis, and severe cardiomyopathy.1 These conditions were considered present if listed in the past medical history. Cognitive status was measured as impaired or not impaired based on medical record recordings on short-term memory (0=normal, 1=impaired), long-term memory (0=normal, 1=impaired), and cognitive skills for daily decision making (0=normal, 1=impaired). A total score could range from 0 to 3 and a score of 2 or 3 was classified as cognitively impaired. Physical functional status was measured from physical therapy notes taken at admission and discharge on patient’s ability to walk. In addition, functional status was measured using the Functional Independence Measure (FIM) obtained from the physical and occupational therapy assessments at baseline and discharge. The FIM is a widely used, reliable and valid 18-item instrument that measures how physically independent a person is (1= total dependence and 7=total independence), with total scores ranging from 18 to 126.16, 17 Other data were pain levels (daily reports of pain) and depression (measured by use of antidepressant agents or documentation of depression). Complication was defined as having hospital or SNF complications. Hospital complications included participants who had one or more of the following: arrhythmia, heart failure, pacemaker, defibrillation, intra-aortic balloon pump, renal failure, stroke, infection, hemorrhage, and re-intubation. SNF complications included documentation of one or more of the following: methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus, clostridium difficile, pneumonia, urinary tract infections, other infections. Co-morbidity was measured using the Charlson Co-morbidity Index.18 The instrument measures the number and seriousness of co-morbid diseases using a weighted index. Summing the weighted co-morbid conditions present at discharge derives a total score.

The cardiac care delivered in the SNF included activities related to therapy/exercise and education. Evidence of cardiac care was identified from documentation in therapy, nursing notes, and the interdisciplinary discharge record. The cardiac care components that were collected were based on the AACVPR guidelines for rehabilitation in the inpatient and transitional settings.1 The components were:

Warm up/cool down with each physical and occupational therapy session or nurse-assisted walking session,

Assessment of exercise tolerance measuring vital signs before and after therapy using pulse oximeter readings and the Borg Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) scale.19,20

Cardiac precautions (no lifting, no arms above the head, and no pushing),

Endurance training (use of equipment and additional walking sessions assisted by nurses),

Education concerning risk factor reduction strategies and educational materials given on cardiac symptom management (e.g., what to do if they have shortness of breath or have increased swelling), survival management (when to call the physician or Emergency Medical Services), and discussion of outpatient cardiac rehabilitation programs.

Phase 2: Healthcare Professionals Procedure

Healthcare professionals (N=31) from the two SNFs were approached during staff meetings and were asked to complete a 15-minute questionnaire to assess the current integration of cardiac care into practices. All staff approached during the meetings agreed to participate.

The data collected from the nurses, physical therapists and occupational therapists included the number of years in practice and questions about their current practice. In addition, healthcare professionals were asked to record the cardiac care they delivered by responding to the list of cardiac care components abstracted from the medical record review. This part of the study was to validate the results obtained in the medical record review as the case could be made that healthcare professionals performed the cardiac care but did not document it.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses were performed in SPSS for Windows release 17 (12 Nov 2009). Data analysis was descriptive in nature including range of scores, means, proportion agreement, and percentages. Data collection was performed by two researchers and inter-rater reliability was measured on each variable recorded on the first five medical records and every 12th medical record thereafter (14% of the sample). The inter-rater reliability of the data collection between the two researchers was 91%.

Results

Characteristics of Patients in SNF following a Cardiac Event

The demographics of the sample are listed in Table 1. The mean age was 77.5 (range 65–95), 78% were female, 43% were black, and the majority had heart failure. The mean length of stay in the SNF was 12 days (SD=10). When patients were discharged from the SNF, 70% went home, 16% were readmitted to acute hospital care, and 14% went to a nursing home.

Table 1.

Patient factors of Adults age ≥65 Transferred to a Skilled Nursing Facility Post-hospitalization for a Cardiac Event or Procedure.

| N=80 X(SD) |

|

|---|---|

| Age | 77.5(9.0) |

| Length of stay (days) | 12.0(10.0) |

| Comorbidity | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index | 3.1 (1.9) |

| Number of medications | 14.4(5.7) |

| Physical Function | |

| FIM score Baseline Range 14–66 | 38.8(11.2) |

| FIM Discharge Range 17–78 | 55.6(16.7) |

| N (%) | |

| Cardiac events | |

| CABG | 27(33.8) |

| Valve Surgery | 13(16.3) |

| MI | 24(30.0) |

| Heart failure | 38(47.5) |

| PCI | 4(5.0) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 18(22.5) |

| Female | 62(77.5) |

| Race | |

| White | 45(56.3) |

| Black | 34(42.5) |

| Other | 1(1.2 |

| Insurance | |

| Medicare only | 16(20.5) |

| Medicare + supplement | 28(35.9) |

| Medicaid | 9(11.5) |

| HMO | 4(5.1) |

| Private | 9(11.5) |

| No information | 12(15.4) |

| Illness Severity | |

| Cardiac disorders putting patients at high exercise risk status | 6 (7.5) |

| Unstable ischemia | 9 (11.3) |

| Uncompensated HF | 4 (5.0) |

| Arrhythmias | 4 (5.0) |

| Aortic Stenosis | 4 (5.0) |

| Cardiomyopathy | 6 (4.8) |

| Report of chest pain | |

| Patients with 1 or more of the above conditions indicating high risk | 17(21.3) |

| Length of stay in hospital | |

| 1 week or less | 34(42.5) |

| >1week to 2 weeks | 26(32.5) |

| >2 weeks to 3 weeks | 6(7.5) |

| more than 3 weeks | 14(17.5) |

| Dialysis | 8(10.4) |

| Cognitive Status | |

| Impairment of 2 of 3 indicators (short-term, long-term, or decisional) | 8 (6.4) |

| Physical Function | |

| Inability to walk Admission | 10 (8.0) |

| Inability to walk Discharge | 5 (4.0) |

| Depression | |

| Anti-depressive medication | 30(38) |

| Pain | |

| Daily report of pain | 13 (16.3) |

| Complications | |

| Hospital Complications | 18(22.5) |

| 0 | 32(40.1) |

| 1–2 | 30(37.4) |

| 3–7 | |

| SNF Complication | |

| MRSA | 15(19) |

| C-Diff | 11(13) |

| Pneumonia | 6(7.5) |

| UTI | 19(23.8) |

| Other Infection | 4(5.1) |

| Patients with 1 or more of the above infections | 23(28.8) |

| Social | |

| Marital Status | |

| Single | 10(12.5) |

| Married | 24(30.0) |

| Widow | 35(43.8) |

| Divorce | 6(10.2) |

| Lived Alone prior to hospitalization | 23 (28.8) |

| SNF discharge destination | |

| Home (no homecare) | 2(2.6) |

| Home (with homecare) | 54(66.7) |

| Another nursing facility | 10(12.8) |

| Acute care facility | 13(16.7) |

| Rehabilitation hospital | 1(1.3) |

PCI=percutaneous coronary intervention

Patient characteristics are listed in Table 1. Overall, 19 participants (21%) had one or more cardiac disorders that placed them in the AACVPR high exercise risk category indicating a potential for cardiac decompensation during exercise. Two additional indicators of illness severity were length of hospital stay (57% hospitalized greater than 1 week, n=46) and chronic dialysis (10%, n=8). Eight (6.4%) of the patients had cognitive impairments. Upon admission, there were ten patients (8%) who were unable to walk, and only five regained the ability to walk at discharge. Patients who did not regain walking ability were discharged to a long-term nursing home. Physical function, as measured by FIM scores both upon admission and discharge, was well below the midpoint of 72 indicating impairment. Thirty-eight percent of patients were on an antidepressant and 16% (n=13) had documentation of daily complaints of pain at moderate intensity. Thirty percent of the patients had both three or more hospital complications and SNF complications. Comorbidity was high as patients had a mean of 3 comorbid conditions. Social variables measured were marital status (30% were married) and living arrangements (30% lived alone).

Current Cardiac Care Delivered during SNF

Cardiac specific rehabilitation care delivered by nursing and physical and occupational therapy was abstracted from the medical records (Table 2). Structured monitoring of the cardiac response to therapy (exercise tolerance) was reported in less than 5% (n=4) of the therapy records and only 13% (n=10) of the nursing notes. Evidence of exercise or activity intolerance (e.g., dizziness, low blood pressure) was found in 33% (n=18) of the nursing notes, 16% (n=13) of the physical therapy notes, with one case in the occupational therapy notes. Exercise equipment to increase endurance was available, but rarely used. Nursing staff efforts to increase endurance by walking patients on the units was not found.

Table 2.

Cardiac Specific Services Delivered during SNF care: Documentation and Report from Healthcare Professionals

| Medical Record Review | Survey | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Registered Nurses’ Notes N=80 n (%) |

Physical Therapists’ Notes N=80 n (%) |

Occupational Therapists’ Notes N=80 n (%) |

Registered Nurses’ Reports N=22 n (%) |

Physical Therapists’ Reports N=5 n (%) |

Occupational Therapists’ Notes N=4 n (%) |

|

| Therapy Related | ||||||

| Do a Warm-up and Cool-down | 0 | 0 | 0 | n/a | 3(60) | 2(50) |

| Use the following for cardiac monitoring | ||||||

| before and after therapy session or walking | ||||||

| Borg scale | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1(4.5) | 2(40) | 0 |

| Pulse Oximeter | 0 | 4(5) | 3(3.8) | 0 | 2(40) | 0 |

| Heart rate/BP | 8(10) | 4(5) | 2(2.6) | 0 | 1(20) | 1(25) |

| Documentation of exercise intolerance | 18(32.5) | 13(16.3) | 1(1.3) | 22(100) | 5(100) | 4(100) |

| Cardiac precautions (No lifting) | 0 | 0 | 3(3.8) | 22(100) | 5(100) | 4(100) |

| Endurance: Evidence of use of equipment | ||||||

| Nu-step | N/A | 4(5) | 0 | N/A | 2(40) | 0 |

| Ergometer | N/A | 0 | 12(15) | N/A | 4(80) | 2(50) |

| Strength Training-bands | N/A | 25(31.3) | 0 | N/A | ||

| EDUCATION | ||||||

| Cardiac risk factor education | 2(2.6) | 1(1.3) | 0 | 12(54.5) | 2(40) | 2(50) |

| Provide educational materials | 0 | 0 | 0 | 7(31.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Cardiac symptom management | 1(1.3) | 1 (1.3) | 2(2.6) | 12(54.5) | 2(40) | 0 |

| Discussion of outpatient Cardiac Rehabilitation | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Healthcare Professionals Integration of Cardiac Care

Of the 31 respondents that completed the data collection tool, 71% (n=22) were nurses, 16% (n=5) were physical therapists, and 13% (n=4) were occupational therapists. Among them, the mean number of years of experience in health care was 11.4 (SD= 7.2) for nursing, 6.4 (SD=2.2) for physical therapy, and 11.3 (SD=6.7) for occupational therapy (data not shown).

Incorporating exercise warm up and cool down was reported by 60% (n=3) of the physical therapists and 50% (n=2) of the occupational therapists (Table 2). Only physical therapists used the BORG RPE scale and the cardiac response to exercise was only reported to be monitored when the patient became symptomatic with exercise and was not done on a routine basis. All healthcare professionals participating in the study said that they documented when a patient had exercise intolerance and adhered to cardiac exercise precautions. Endurance interventions were reported mainly by the physical therapists, who estimated that 80% of their patients would benefit from the use of an ergometer and 40% would benefit from the use of the recumbent exercise machine. Approximately 50% of the healthcare professionals reported that they provided information on cardiac risk factors, and only the physical therapists and occupational therapists reported providing education on symptom management.

Eighteen percent (n=4) of the nursing staff reported that patients were walked for additional endurance therapy outside of therapy sessions, while 45% (n=9) reported that walking patients was not feasible during their shift. Thirty-two percent (n=7) of the nursing staff reported concerns with walking cardiac patients due to their perceived unstable cardiac status. Nurses reported giving important discharge education related to chest pain (27%), sternal precautions (60%), signs and symptoms of myocardial infarction or heart failure (64%) and a home walking program (32%). There were no reports of discussion of outpatient cardiac rehabilitation services.

Discussion

Neither of the two AACVPR recommended Phase IB post-acute cardiac care rehabilitation components (exercise and education) were integrated into SNF practice in a structured or consistent manner. Not providing these cardiac specific care interventions is a missed opportunity for ensuring that cardiac patients receive complete chronic disease focused and safe rehabilitation during their SNF transitional care.

Monitoring exercise tolerance is an essential component to ensure that the patient’s cardiac system can tolerate the intensity of therapy sessions and activities. Six patients had documented chest pain during therapy and there were 32 episodes of activity intolerance documented (e.g. dizziness, decreased heart rate and blood pressure). Monitoring of patients’ cardiac response to exercise was not a standard of care. Vigilant monitoring of exercise tolerance is important, as there is no evidence of the safety in providing physical and occupational therapy to cardiac patients in SNF. Cardiac rehabilitation exercise has been demonstrated to be safe in community samples21 and safe in heart failure patients 22; however, both of these groups include ambulatory outpatients. Future research is needed to identify exercise risk categories for SNF patients and to assess the safety of exercise for cardiac patients in SNF through the assessment of exercise tolerance during physical and occupational therapy. Clinically, SNF services need to include physician oversight to identify high exercise risk patients and orders to monitor patients' cardiac status during therapy.

The second essential cardiac care intervention is teaching patients what to do when they are discharged, as two-thirds of SNF patients return home. Patients discharged from the SNF need education on survival management, (e.g., what to do if they get chest pain, how to take nitroglycerin tablets, and how and when to call emergency medical services). Additional important discharge education includes self-management and continuation of their walking plan, diet, medication management, and symptom management. In addition, because 48% of these patients had heart failure, patient and family education on heart failure management is warranted.

Although there is a substantial need for SNF cardiac care, it is not likely that all patients are appropriate candidates. Participation in cardiac care requires the ability to actively engage in therapy/exercise and educational sessions. We found that 32% (n=26) of patients had one or more of the following limitations that would impair their rehabilitation potential: inability to walk, severe physical disability, and untreatable pain. These limitations have been found to inhibit active participation in outpatient cardiac rehabilitation activities.22–26 A notable finding in the study was that of the 26 patients who had impaired rehabilitation potential, 73% of these 26 were either discharged to a long-term care nursing facility or rehospitalized. The patients discharged to the long-term care facilities would be unlikely candidates for cardiac rehabilitation.27

Patients who use post-acute care services such as SNF are likely to have cognitive as well as physical impairments. In our sample, 6.4% were identified as cognitively impaired. Patients with cognitive impairment will benefit from the exercise component of the rehabilitation. However, the education component will be difficult to deliver. It is important that the families of these patients be integrated into the care early on so that they are prepared to care for the patients when they return home.

There was very little documentation in the medical records to indicate that cardiac care was integrated into SNF practice. Data from the SNF nurses, physical therapists, and occupational therapists confirmed that delivery of these services is not consistent or standardized. Most of the SNF healthcare professionals reported that the majority of monitoring for exercise tolerance was performed only when patients were symptomatic. This is unfortunate, as subtle changes in exercise tolerance can be detected prior to patients becoming symptomatic. A subtle change of cardiac decompensation (e.g., heart rate and blood pressure decline from pre-therapy to post therapy) may not show up with overt symptoms, but would alert the therapist that the patient’s cardiovascular system is being challenged and is unable to compensate for the level of exercise intensity.

Integration of an evening walk into a patient’s routine can be one way to increase endurance; however, only 18% of the nurses reported that they felt it was feasible to walk patients outside of regular therapy due to the lack of staff. Significantly, 32% felt uncomfortable walking a cardiac patient due to the potential for another cardiac event. Standardization of care that includes protocols for ambulating patients outside of physical therapy need to be integrated. Ambulating patients in the evening can be performed by nursing assistants. We also found that the exercise endurance equipment (ergometer and recumbent bike) was available, but equipment use was rare. Despite the apparent lack of use, therapists reported that 80% of their patients could use the ergometer, and 40% could use the recumbant bike. Although we did not ask therapists why they did not use the equipment, one reason might be the difficulty getting the patients on the equipment and safe use of the equipment.

There was very little documentation of education related to risk factor management or discharge instructions. The lack of specific cardiac rehabilitation education may be due to the absence of regulations on mandating discharge education in SNFs. Some SNF nurses participating in the study said that patients were given educational materials in the hospital and did not need additional materials given to them in the SNF. As patients received care in the SNF for an average of 12 days, the opportunity to use this time for additional education and family involvement was missed. Eighty percent of physical therapists reported providing verbal education on a home walking program while less than half provided education on symptom management or self-monitoring of exercise tolerance using the BORG RPE scale. This is unfortunate as the BORG RPE scale is an important tool to help cardiac patients understand when they are overexerting during daily activities.19

There are barriers to integrating cardiac care into SNF care. First, patients admitted to SNFs have many comorbidities and hospital complications. The average number of comorbidities is three and the average number of medications is 14. Dialysis patients (n=8, 10%) were especially complex, as they had the highest complication rates and were most likely to be discharged to a long-term nursing home. Patients struggle with many complications; for example, 68% of the sample in this study had 1 or more hospital complications, (such as arrhythmia, heart failure, pacemaker, defibrillation, intra-aortic balloon pump, renal failure, stroke, hemorrhage, and re-intubation) and 40% had 1 or more infections. Despite these barriers, the majority of patients who complete an inpatient sub-acute cardiac rehabilitation program (Phase 1B) continue to adhere to a walking program one year after discharge.28

There are important clinical implications from the findings of this research. On an organizational level, the majority of cardiac patients would benefit from a cardiologist involvement to assess and document exercise risk category. In addition, there needs to be integration of a standard assessment of vital signs before, during, and after physical and occupational therapy. Other cardiac rehabilitation components that need to be integrated include warm up and cool down before and after therapy, additional walking, and use of the BORG RPE scale. Families and significant others would benefit from educational interventions, including survival and symptom management and teaching patients and family members how to monitor for exercise tolerance using the BORG RPE scale. Family caregivers could also learn how to assist patients for when they return home, and be educated about the benefits of continuing cardiac rehabilitation in an outpatient setting. Family involvement in walking would increase both patient and family self-efficacy.

Limitations to this study include patient medical records that may not accurately reflect services performed in the SNFs because staff did not document delivered services. In addition, the accuracy of the data is limited by the person documenting the assessments. Specific to depression, we measured depression by the presence of an anti-depressant on their medication list. Caution must be taken in the conclusions of the study regarding depression as our measurement strategy does not include patients who are not treated or not diagnosed for depression. The results cannot be generalized to all SNF as the SNFs in this study were hospital-based. Hospital based SNFs usually have a higher acuity of patients than stand-alone SNFs and therefore the patient population in this sample may reflect a more severe illness burden. Finally, patient and staff numbers were small thus limiting generalizability.

Future research on the integration of cardiac rehabilitation components into SNF care is necessary to identify the safety of therapy and to identify educational strategies to optimize the transition to home and outpatient cardiac rehabilitation. The identification of who is at risk for cardiac decompensation and who is a candidate is important. In addition, identifying the characteristics of rehospitalized patients is crucial as rehospitalization rates from SNFs are approximately 29%.8 Cardiac rehabilitation interventions to reduce patient rehospitalizations include early identification of exercise intolerance and targeting heart failure patients for better self-management.

The older cardiac patient who is transferred from acute care to a SNF is the least likely to enter outpatient cardiac rehabilitation25, 26 and therefore never receives the documented benefits of cardiac rehabilitation that include reduced morbidity, mortality, and improved functional capacity.29 The SNF experience is an ideal time to discuss outpatient cardiac rehabilitation options and promote the use of these services.

An opportunity exists to integrate cardiac care into SNF care. Incorporating cardiac care will ensure that patients’ cardiac response to exercise is monitored and that patients and families receive education on chronic care management. Providing these interventions will enhance the transition from SNF to home, and may increase the entrance into outpatient cardiac rehabilitation programs.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Multidisciplinary Clinical Research Training Program (K12RR023264) and was made possible by Grant Number KL2RR024990 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. Information on NCRR is available at http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/. Information on Re-engineering the Clinical Research Enterprise can be obtained from http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/clinicalresearch/overview-translational.asp.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosures

None

Contributor Information

Mary A. Dolansky, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing, Case Western Reserve University.

Melissa D. Zullo, Division of Epidemiology, College of Public Health at Kent State University.

Salwa Hassanein, Department of Community Health Nursing, Cairo University.

Julie T. Schaefer, Department of Food, Nutrition, and Exercise Sciences, College of Human Science, Florida State University.

Patrick Murray, MetroHealth Medical Center, Department of Medicine and Physical Rehabilitation.

Rebecca Boxer, Department of Medicine, Case Western Reserve University.

References

- 1.Guidelines for Cardiac Rehabilitation and Secondary Prevention Programs. Fourth Edition ed. 2004. American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Speziale G, Nasso G, Barattoni MC, et al. Operative and middle-term results of cardiac surgery in nonagenarians: a bridge toward routine practice. Circulation. 2010 Jan 19;121(2):208–213. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.807065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ajani UA, Ford ES. Has the risk for coronary heart disease changed among U.S. adults? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006 Sep 19;48(6):1177–1182. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.05.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ford ES, Ajani UA, Croft JB, et al. Explaining the decrease in U.S. deaths from coronary disease, 1980–2000. N Engl J Med. 2007 Jun 7;356(23):2388–2398. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa053935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dolansky MA, Moore SM. Older adults' use of postacute and cardiac rehabilitation services after hospitalization for a cardiac event. Rehabil Nurs. 2008 Mar;33(2):73–81. doi: 10.1002/j.2048-7940.2008.tb00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kortebein P, Symons TB, Ferrando A, et al. Functional impact of 10 days of bed rest in healthy older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008 Oct;63(10):1076–1081. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.10.1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Jaarsveld CH, Sanderman R, Miedema I, Ranchor AV, Kempen GI. Changes in health-related quality of life in older patients with acute myocardial infarction or congestive heart failure: a prospective study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001 Aug;49(8):1052–1058. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mor V, Intrator O, Feng Z, Grabowski DC. The revolving door of rehospitalization from skilled nursing facilities. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010 Jan;29(1):57–64. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dolansky MA, Xu F, Zullo M, Shishehbor M, Moore SM, Rimm AA. Post-acute care services received by older adults following a cardiac event: a population-based analysis. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2010 Jul;25(4):342–349. doi: 10.1097/JCN.0b013e3181c9fbca. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kane RL. Finding the right level of posthospital care:"We didn't realize there was any other option for him". JAMA. 2011 Jan 19;305(3):284–293. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Center for Medicare Advocacy. [Accessed April 13, 2011];Internet. 2011 Available at: URL: http://www.medicareadvocacy.org/medicare-info/skilled-nursing-facility-snf-services/

- 12.Sansone GR, Alba A, Frengley JD. Analysis of FIM instrument scores for patients admitted to an inpatient cardiac rehabilitation program. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002 Apr;83(4):506–512. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.31183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kong KH, Kevorkian CG, Rossi CD. Functional Outcomes of Patients on a Rehabilitation Unit After Open Heart Surgery. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation. 1996 Nov 20;16(6):413–418. doi: 10.1097/00008483-199611000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glassman SJ. Components of a cardiac rehab program. Rehab Manag. 2000 Jan;13(1):28–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miralles R, Sabartes O, Ferrer M, et al. Development and validation of an instrument to predict probability of home discharge from a geriatric convalescence unit in Spain. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003 Feb;51(2):252–257. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dodds TA, Martin DP, Stolov WC, Deyo RA. A validation of the functional independence measurement and its performance among rehabilitation inpatients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1993 May;74(5):531–536. doi: 10.1016/0003-9993(93)90119-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Granger CV, Hamilton BB, Linacre JM, Heinemann AW, Wright BD. Performance profiles of the functional independence measure. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1993 Apr;72(2):84–89. doi: 10.1097/00002060-199304000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and Validation. Journal of Chronic Disease. 1986;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borg G, Dahlstrom H. The reliability and validity of a physical work test. Acta Physiol Scand. 1962 Aug;55:353–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1962.tb02449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borg GA. Psychological basis of physical exertion. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1982;14:377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hedback B. Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. London: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whellan DJ, O'Connor CM, Lee KL, et al. Heart failure and a controlled trial investigating outcomes of exercise training (HF-ACTION): design and rationale. Am Heart J. 2007 Feb;153(2):201–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Buchner DM, Cress ME, de Lateur BJ, et al. The effect of strength and endurance training on gait, balance, fall risk, and health services use in community-living older adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997 Jul;52(4):M218–M224. doi: 10.1093/gerona/52a.4.m218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Focht BC, Ewing V, Gauvin L, Rejeski WJ. The unique and transient impact of acute exercise on pain perception in older, overweight, or obese adults with knee osteoarthritis. Ann Behav Med. 2002;24(3):201–210. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2403_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Newman MF, Kirchner JL, Phillips-Bute B, et al. Longitudinal assessment of neurocognitive function after coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2001 Feb 8;344(6):395–402. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102083440601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newman MF, Grocott HP, Mathew JP, et al. Report of the substudy assessing the impact of neurocognitive function on quality of life 5 years after cardiac surgery. Stroke. 2001 Dec 1;32(12):2874–2881. doi: 10.1161/hs1201.099803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas RJ, King M, Lui K, Oldridge N, Pina IL, Spertus J AACVPR/ACCF/AHA. 2010 Update: Performance Measures on Cardiac Rehabilitation for Referral to Cardiac Rehabilitation/Secondary Prevention Services Endorsed by the American College of Chest Physicians, the American College of Sports Medicine, the American Physical Therapy Association, the Canadian Association of Cardiac Rehabilitation, the Clinical Exercise Physiology Association, the European Association for Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation, the Inter-American Heart Foundation, the National Association of Clinical Nurse Specialists, the Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010 Sep 28;56(14):1159–1167. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macchi C, Polcaro P, Cecchi F, et al. One-year adherence to exercise in elderly patients receiving postacute inpatient rehabilitation after cardiac surgery. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2009 Sep;88(9):727–734. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e3181b332a1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jolliffe JA, Rees K, Taylor RS, Thompson D, Oldridge N, Ebrahim S. Exercise-based rehabilitation for coronary heart disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;1 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001800. CD001800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]